2—

Covenants, Truth, and the "Ruthless Democracy" of Moby-Dick

But the Declaration of Independence makes a difference.

—Herman Melville, Letters

The Narrative Covenant

Moby-Dick (1851) constantly retraces its steps, backtracking in the progression of its narrative to provide amendments and prefaces to the story it is telling. Ishmael often confesses his negligence and atones for his sins of omission by reversing course to sketch details and provide supplemental information. "The Sphynx" thus commences by referring backward: "It should not have been omitted that previous to completely stripping the body of leviathan, he was beheaded."[1] The chapter "Ambergris" contains an apology from Ishmael that he may have unjustly assumed the landsman reading his tale to have a familiarity of certain practices common to the whaling industry: "I have forgotten to say that there were found in this ambergris, certain hard, round, bony plates" (317). Or consider how "The Dart" opens by flinging itself backward: "A word concerning an incident in the last chapter" (230). As a sailor, Ishmael seems given to this same predilection; when on deck at the tiller, he fixes on the ghastly madness of the tryworks and then turns himself about. His negligence threatens to capsize the Pequod by running her into the winds. Looking backward jeopardizes the stability and safety of the ship's crew, just as Ishmael's narrative retracings and circlings back run counter to the imperious linearity of Ahab's hunt. In this sense, the narrative's use of allusive names like Rachel or Ahab causes the reader to turn back to prior textual sources, searching after a textual foundation to find support and meaning. Such references impede the reader's progress into the story with vague suggestions and half hints like those Elijah speaks to detain Queequeg and Ishmael momen-

tarily before they board the cannibal craft. Moby-Dick 's tacking back and forth indicates how narrative must be built on prior sources, but even as it returns to textual foundations, the novel exposes a concern about the stability and desirability of narrative in the first place.[2]

Using a strategy prone to forgetfulness and a prose interrupted by hiccups of memory, Ishmael problematizes the act of narration. Fully aware that he is telling an American odyssey in pursuit of an ending, Ishmael engages in a covert insurrection against his own narration, stalling the narrative whenever possible. His digressions and deferrals more than stall disclosure of Ahab's mission: such devices obstruct the seemingly irrefragable course of narrative that threatens to invest him as teller with the same fatherly authority that guides and governs Cooper's national narrative of the Revolution. When Melville wished "that all excellent books were foundlings, without father or mother," he expressed Ishmael's desire to orphan his text, to sever his book from the originary sources of privilege and status, to send off his story as a wayward articulation.[3] If Melville was in one sense the originator or father of Moby-Dick , Ishmael was to be his parricide. Under the guise of a scrupulous attention to detail and the apologies for his somewhat absent-minded narration, Ishmael plays the idle philosopher, amateur biologist, temperance reformer, dabbler in jurisprudence, historian of the sperm-whale fishery, all to conceal his critical examination of the patriarchal authority that secures narrative progression and closure. Harboring this project, Ishmael manipulates Moby-Dick to interrogate the nature of narrative (not to mention the narrative of nature), resisting a destiny that can lead only to, if not ideological closure, then at least a plotted ending. He tries to find exception to what the essence of narrative authoritatively demands; he wonders if stories, like nations, need move toward the promised land of a final page. In other words, Ishmael constructs a politics of narrative through which he can take issue with the covenant the author makes with the autocratic structure of narrative in order to impart his tale; he questions both the terms as well as the feasibility of attaining the promises to be fulfilled with the completion of narrative. This line of interrogation implicates citizens as well, leading Ishmael to examine critically an implacable covenant that requires consent to American national narrative as a precondition of encountering and attaining meaningful political experiences such as freedom and community.

At times, Ishmael seeks to circumvent the teleological narrative of metaphysics. From the first paragraph, Ishmael desires to deny his own essence in suicide. Likewise, his status as an orphan frustrates the implicit teleological quests of genealogy, history, and biography. For Ishmael, Ahab heroically embodies this rejection of the classical narrative of metaphysics by chastising the gods and fates for assuming that they can determine his destiny. Elsewhere, Ishmael's retrogressions insinuate doubts about the sanctity of historical narrative. "Fast-Fish and Loose-Fish," like many chapters in Moby-Dick , starts with a return to a preceding episode: "The allusion to the waifs and waif-poles in the last chapter but one, necessitates some account of the laws and regulations of the whale fishery, of which the waif may be deemed the grand symbol and badge" (307). What seems an innocent correction of a whaling story develops as a critical examination of American narrative. Ishmael amends the expanding history of the American experience by pointing to the expansionist tendencies of its own inception: "What was America in 1492 but a Loose-Fish, in which Columbus struck the Spanish standard by way of waifing it for his royal master and mistress? ... What at last will Mexico be to the United States? All Loose-fish" (309–10). The unavoidable colonialist impulses of Manifest Destiny become part of this chapter, whose inclusion encourages a reexamination of the text that has preceded it. Not only do we turn back to "The Grand Armada" to consider "waifs and waif-poles"; we also review other textual ancestors, the founding principles of an American history, which in telling us of a liberty secured from a colonial oppressor point to 1850s America's hypocritical regard for its origins. Rather than simply smoothing out the narrative by amending it with background information, the history supplied here suggests the inconsistencies between inherited ideals and current governance. As Ishmael informs us that the regulations of fast fish and loose fish determine what is "fair game," he reminds us that the game is not fair, but a "masterly code" whose lawful wisdom translates into imperial domination (307). He interrupts a plot seemingly bent upon monomaniacal conclusion to impede another plot devoted to grandiose designs; he politicizes the interruption of a whaling voyage, using it to imply a subversion of the teleological vision of Manifest Destiny.[4]

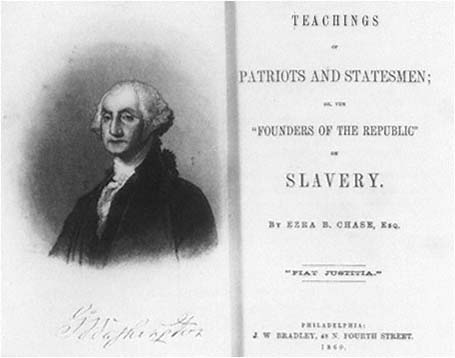

Whereas an ardent believer in the Union like the author of Teachings of Patriots and Statesmen; or, the "Fathers of the Republic" on Slavery

(1860) hoped that his countrymen would "steadily pursue the path marked out by the fathers, and perpetuate the principles" of the Union, a conciliatory sentiment seconded in Henry Clay's proposal that Washington's Farewell Address be ritually reread, Melville cherished no expectations that filial returns to founding fathers would rededicate the nation to either consensus or justice.[5] National retrospection, as the willy-nilly backward glances of Moby-Dick suggest, may not delineate any clear "path," but instead lead to an unrelated series of halfhearted investigations that end up nowhere. In fact, the search for a stable history can backfire and uncover further, more profound division. Characterizing Ahab, Ishmael warns against excavations of the past if one is looking not to find a parricidal supplement, but further testaments of purity and guidance: "from your grim sire only will the old State-secret come" (155). Genealogy may lead to unsuspected discoveries that contradict or simply complicate the legitimating and linear story genealogy proposes to trace. Ishmael's lack of patriarchal faith readily sets him apart from the pietistic counselor of the Teachings of Patriots and Statesmen , who prefaces his volume with a frontispiece of Washington as though the sight of the founder could provide the clarity of vision to secure the national and narrative conclusions that Melville suspected (Figure 1). This engraving of the national father, bearing a facsimile of the general's signature that exercised such authority in The Spy , establishes a firm foundation for what is no doubt a rocky issue. The image and name of Washington steers a course between "extremists, both North and South," guiding the sons through the fractious present by appeal to the stability of texts from the country's past. Moby-Dick , in contrast, can only assemble an array of abortive prefaces over which shakily preside "a late consumptive usher" (9) and a "mere painstaking burrower and grubworm" (11). Ancestry thus has little sway in Moby-Dick , not the least because of Ishmael's efforts to undermine the coordinates of order and authority, whether maritime, narratival, or cultural.

From its beginning, Moby-Dick tackles the sources, origins, and genealogy of narrative precisely because it does not have a beginning, but multiple beginnings whose sheer plurality renders narrative authority a circumspect force in the novel. An etymology prefaces Ishmael's appearance. Ranging across thirteen languages, this entry tries to derive the linguistic essence of the whale, mirroring

Fig 1.

The claims to authority implied by the frontispiece and title page

of Ezra Chase's work starkly contrast with the suspect array of prefaces that

open Moby-Dick.

Ahab's fanatic drive to pierce the life of Moby Dick and clutch at physical and spiritual mysteries. The gamut of possibilities, from the Latin cetus to the English whale to the unfamiliar and fanciful "Feejee" pekee-nuee-nuee , makes leviathan indeterminate, a protean entity changing across different cultural imaginations. In this ironic attempt to muster a comprehensive linguistic knowledge, Melville marshals the support of lexicographers, yet each contradicts the other, citing different origins of the English word whale . The etymology fails to resolve the ambiguity that arises from the title itself. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale poses a question just as much as it announces the novel. The hedging either/or quality of this self-declaration undercuts Moby-Dick by immediately placing it under revision with its identification as one of a certain species of animal. Moby-Dick falls short

of being intelligible by itself; it needs to be amended with The Whale , a term that then comes under scrutiny and fragments into the Babel of the etymology. Unlike a national primer anchored by the singular presence of Washington, Melville's novel gets under way pulled at by crosscurrents set up by the effort to put it into motion.

Linguistically unable to moor itself in any sovereign meaning, Moby-Dick next searches after cultural authority in the "Extracts." In this second preface, a sub-sub librarian amasses an impressive array of references stretching from the Genesis account of divine authorship, "And God created great whales," to The New England Primer 's reiteration of God's authority, "Whales in the sea / God's voice obey," to Hobbes's study of civil authority in Leviathan (12, 15). Despite the exhaustive length of this compilation, not to mention the great length of leviathan himself, these extracts exact little authority. Melville prefaces this preface with a short note designed to provoke ridicule and skepticism of "higgedly-piggedly whale statements" that the "grubworm of a poor devil of a Sub-Sub," the antithesis of the mighty whale, has painstakingly arranged (11). After this, the narrative proper begins: "Call me Ishmael." Maybe that is the narrator's name or maybe not; after the sham endeavors of the etymology and extracts, he would fain make a claim for authenticity. At the very moment that Ishmael issues an authorial announcement of his own identity, we take his statement as a warning that we need beware a possible deception from a narrator telling a tale under an assumed name. Lacking any textual foundation, having only the vacillating nature of the novel's either/or title, Ishmael can inscribe his own being only as a moment of doubt and suspicion that quickly degenerates into a desire for suicide. Any appeals to authority that he might make are undermined with the confession that Moby-Dick merely forestalls self-annihilation, that a sea voyage and the telling of it are "my substitute for pistol and ball" (23). Ishmael internalizes the filial rebellion of preface to text and contemplates murderous rebellion against the sovereign authority of his being.

Sailing the Pequod into the wind or proceeding backward via prefaces and textual emendations imperils both the mariners and the narrative, undercutting the planned course of any expedition. These prefaces, in both their supplemental succession one after another and their dubious communication of information, compile doubts about the text's origins and stage a rebellion against the narrative that

follows. The rebellion is even more insidious because it does not appear to be a rebellion. The prefaces pretend to shore up the narrative by making an appeal to linguistic and cultural contexts, only to engage in a textual insurrection. Questions arise that produce a lack of confidence in the integrity of the narrative project: where has the author gotten his authority to narrate his story? From his own personal experiences? From history? From a culture that accepts such a mythic telling? As we have seen, Cooper faced such doubts in the introduction to his own novel of the Revolution: "The author has often been asked if there were any foundation in real life" for his narrative. Ishmael hopes that these notes supplied by "a late consumptive usher to a grammar school" and "a sub-sub librarian" will answer such questions, but he covertly desires that this attempt to establish authority will undermine it. The array of prefaces and false starts allows Ishmael to interrogate his own patriarchal authority to tell his tale by expressing deep-seated reservations about the project of narrative itself: can the author narrativize solely by relying upon a willful cultural authority unconcerned with democratic models of narrative, what Melville called "truth"? In other words, does narrative need only a will as irrefutable as Ahab's, which has no scruples about manipulating the cultural power of prejudice, stereotype, and superstition, in order to bend covenanted listeners to its articulation and enactment?

In "Hawthorne and His Mosses," Melville undertook to answer these questions, describing the strategies an author must use to avoid surrendering truth to a culture whose concern is not truth, but power and authority.[6] In order to tell a tale, an author has to make a covenant with authority: he or she agrees to cede truth in exchange for the cultural authority to narrate. Words, allusions, tropes, icons, and symbols can all serve as part of the artist's literary arsenal if he or she lets go of pure, unadulterated truth and filters it through the vehicles of discourse that culture has so graciously offered. According to Melville, without the legitimation or protection of truth by these filters of cultural authority, "truth is forced to fly like a sacred white doe in the woodlands; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself." Once borne by these tropes circulating within cultural discourse, however, truth no longer needs be bashful precisely because it is no longer untainted and delicate truth, having been perverted and encouraged to lie. If truth is forced to fly outside of

the domain of culture, it is eventually tracked down and secured within the authoritative discourses of that culture. In this way, the argument in "Hawthorne and His Mosses" anticipates Foucault's analysis of discursive truth. Like Melville, Foucault understands that truth cannot exist in the wilds, unfettered by culture, but that truth must always be positioned "dans le vrai ," (within the true). Foucault gives the example of Mendel, who spoke the truth only to be dismissed because he failed to speak within the truth ordained by contemporary biological discourse.[7] In contrast to Mendel, ethnologists of Melville's era could authoritatively describe the symptoms of drapetomania, a mental aberration that caused black slaves to run away, because such a disease fell dans le vrai of a discourse permeated with notions of racial hierarchy and ethnocentrism. American statesmen similarly spoke the truth when they described the annexation of slave territories as a project to "extend the area of freedom" because such claims were made within the authorizing tenets of an American narrative plotted with Manifest Destiny. No matter how much truth desires "to fly like a sacred white doe in the woodlands," Moby-Dick reminds us that truth, despite its transcendental aura, is always connected to society, is always saturated by an array of political, nationalist, biological, or literary discourses. As Foucault writes, "Truth is a thing of this world: it is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint. And it induces regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth." Once caged in this manner, truth can reveal itself only in spaces not supervised by culture. "You must have plenty of sea-room to tell the Truth in," writes Melville. As the land disappears in Moby-Dick , Ishmael sings an epiphany to the handsome sailor, Bulkington, who shuns companionship ashore: "Know ye, now, Bulkington? Glimpses do ye seem to see of that mortally intolerable truth; that all deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort the soul to keep the open independence of her sea; while the wildest winds of heaven and earth conspire to cast her on the treacherous slavish shore?" (99).

But it is not always possible to sign up for a whaling cruise and leave behind the lee shore; besides, even when one has moved beyond sight of the land, a demagogue named Ahab can arise, charismatically insisting that musings abroad the wide ocean be coordinated around the hunt for a white whale. Melville thus posits that truth resides in the darkness of voices tinged with madness or

evil that resist "slavish" codification. Everyday citizens do not possess such voices; indeed, as Melville writes in "Hawthorne and His Mosses," "it were all but madness for any good man, in his own proper character, to utter, or even hint," of the darker realities that underlie the metaphysical and political aspects of life on the "slavish shore." The citizen "speaks the sane madness of vital truth" in the marginal, uninhabited spaces that exist within culture. Within the Puritanic gloom of Hawthorne, the frantic despair of Lear, the sanctioned idiocy of Pip, or the undecipherable message of Queequeg's tattoos, one can see, like Bulkington, into the depths of "that mortally intolerable truth."[8] Only within the paradoxical incongruity of "sane madness," only within a consciousness ironically positioned against itself, can the citizen utter truth. Obscured by a culture's authority, truth will appear only in the "cunning glimpses" of ironic and parodic representations of authorized discourse.

Ishmael skeptically approaches selling the soul of truth to narrative in exchange for authority; before he enters the narrative of Moby-Dick , before he agrees to the covenant that will authorize him to tell the tale, he affixes a series of prefatory amendments indicating his hesitancy about the project of narrative in the first place. Ishmael has a prejudice against narrative, which, in its peculiarly American incarnations, produces an inexorable drive to capture a conclusion, no matter what the consequences. Other captains, similarly authorized by the notion of the quest, who "systematically hunted out" notorious whales, lead Ishmael to suspect that massacre and extermination are symptoms of larger narrative and cultural imperatives (170). This teleological drive, this monomania for closure, does not only encompass the Pequod 's mad captain, but describes the founding imperatives of American civilization. Ishmael thus specifies the singleminded and relentless pursuit of "New Zealand Tom" and "Do Miguel": "as in setting out through the Narragansett Woods, Captain Butler of old had it in his mind to capture that notorious murderous savage Annawon, the headmost warrior of the Indian King Philip" (170). Whether whale hunting or Indian hunting, each practice is legitimated by a teleology that admits no quarter. This convergence between the present history of whaling and the annals of colonial settlement initiates a double movement that is at once laudatory and ironic: at one moment, whaling is ennobled by its placement within a narrative of American progress that triumphs over the "savage";

at another, the earliest episodes of nation building appear driven by a sophisticated mixture of commercial speculation and genocide. As the present looks to its ancestors for confirmation, as Ishmael tries to discover historical precedents for his current enterprise, the past itself falls under suspicion. Historical returns can only be critical, only parricidal. And, now, aboard a ship named for an extinct tribe of the "Narragansett Woods," Ishmael finds himself replicating yet another American quest. Compiling whale statements and whale etymology, in addition to beginning his narrative with an anonymity that jeopardizes narrative authority, Ishmael delays disclosure of a story that in its maddest moments learns nothing from history and repeats the nation's uncompromising mission of racial trespass.

Rife with antifoundational paradox and misdirections, Ishmael's prefaces initiate a novel in which narrative authority is not total, but ambivalent, in which comments and characters can, if only for brief moments, escape the vortex of speaking dans le vrai .[9] In terms of the novel's events, Ishmael's evasion of the "regime of truth" and search for a non-negotiated truth can be undertaken only amid moments of great ambivalence. He forms a friendship with a pagan cannibal whom he at first distrusts and then later forgets; he criticizes Ahab's political authority even as he finds himself lured by the magnetic quality of his captain's rhetoric. Although these falters make Ishmael an unlikely hero, in terms of an American narrative, such ambivalence exerts a critical force and instills resistance to the tacit assumption that nations and narratives should pursue destinies and endings that place truth within practices and institutions justified by cultural authority. The question becomes: why should a people follow Moses out of the wilderness if to do so it exterminates native tribes of that desert, imports slaves into the desert, and, finally, seizes all of that desert as though it were theirs by divine promise? The impetus of narrative, unchecked by prefaces, moves authors, readers, and citizens along so quickly in an "unfaltering hunt" for a promised closure, a white whale, or a Manifest Destiny, that they have little time to question critically the consequences of their own progress (166).[10]

This preference for prefaces did not make Melville an authorial isolato in his day. His narrative techniques and the issues he thematized have led literary scholars to federate him and other artists along the keel of an era commonly known as the American Renaissance. Shared concerns such as the complication of the legacy of

Puritan morality, the often problematic dramatization of race relations, and the wariness about the individual's incorporation into the community produced a certain insecurity and anxiety about the narratives being authored in mid-nineteenth-century America. That is, the stories told seemed to lack authority because of their often critical and ambiguous renderings of America. Authors sought to compensate for their stories' dubious authority by constructing extratextual appeals to authenticate and verify the narratives. Before Hawthorne can tell the dark romance of the New World that opens with a prison door in The Scarlet Letter (1850), he finds it necessary to author "The Custom House" preface, which both delivers an account of the writer, to provide "proofs of the authenticity of a narrative therein contained," and sketches the historical Surveyor Pue, who "authorized and authenticated" the documents to whose outline his narrative adheres. Yet as many readers have commented, Hawthorne's efforts backfire, registering a host of unsettling anxieties that include his worries about descending from a line of Puritan oppressors as well as his preoccupations about the menacing federal eagle perched above the Custom House door. This preface bears a relation not simply to the text as father, but to Hawthorne's own patriarchal ancestors and the national authority governing his career in Salem. Concurrently tracing family history and federal power, "The Custom House" literalizes Derrida's observations about the preface as a "seminal difféerance " prone to reabsorption within the authority of fatherly figures, from "stern and black-browed Puritans" who would belittle Hawthorne's idle artistic efforts, to "Uncle Sam," who capriciously provides him employment, to Inspector Pue, whose papers are his textual foundation. Edgar Allan Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838) responds to similar concerns about authenticity by appending a preface in which Pym, himself a fiction, declares that a real person, Poe, published parts of the narrative as fiction so that they would have "the better chance of being received as truth." Such ironic twists and turns perversely add to the authority of the text in a manner that is more supplemental than coherent. With some people doubting a slave's ability to read and write, with some believing their narratives to be the shameless propaganda of abolitionists, and with still others doubting the actuality of the events related and the severity of the conditions described, ex-slaves preceded their narratives with introductions from renowned white people. William Lloyd Garrison of

the Liberator provided the authority Frederick Douglass could not claim because of his blackness, and the renowned woman of letters Lydia Maria Child asserted that Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) was no fiction. Garrison confirmed that, despite its poetic skill, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845) was the authentic production of a black slave, and Child apologized for the "execrences" within the story of a slave girl pregnant at fifteen. In addition to authorizing slaves'stories compromised by their authors' identity, these editors lent support to narratives compromised by their own critical politics; the prefaces provided surety for narratives that critically represented the fathers' land of liberty.[11] But that support and surety came at the expense of the slave narrator's discursive independence. Douglass readily recognized that Garrison's prefatory efforts worked inversely, threatening the exslave's ability to stand alone as author and procreate a text, a problematic I explore in chapter 5. These contradictory positions of affirmation and textual undercutting, of filial worship and parricidal desire, recur several times over in Moby-Dick , even before the narrator introduces himself with the words "Call me Ishmael. But insofar as Melville understood that the unabated contradictions of slaveholding within democracy produced these gaps in narrative authority, he would have found only Douglass and Jacobs sharing his insights about the racial connections between narrative and political form.

Nevertheless, Melville remained something of an isolato among both the reading public and the New England literati. "What a madness & anguish it is, that an author can never—under no conceivable circumstances—be at all frank with readers," complained Melville the year before he began work on Moby-Dick .[12] Indeed, the public picked up on that "madness & anguish," and reviewers, in the wake of Mardi and Moby-Dick , intimated that the author was plagued by a nervous disorder and should seek rest in an asylum. In all of America, Melville found he could be frank about his beliefs in truth and democracy with only one person, Hawthorne. And yet traces of embarrassment and hesitation mark even his exuberant letters to Hawthorne. Melville's distaste for missionary programs and temperance crusades kept him aloof from the likes of John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe. He differed with his Pittsfield neighbor, Oliver Wendell Holmes, whom he unfavorably rendered as an exacting scientist in "I and My Chimney"—which, as Carolyn

Karcher suggests, may have been in response to Holmes's interest in racist ethnology that held blacks to be a distinct, less evolved human species. "Poignantly attesting to Melville's sense of isolation is the almost total silence he maintained on the subject of slavery in his letters to family members, friends, publishers, and fellow writers, even while he was formulating his impassioned fictional indictments of it," argues Karcher.[13]

Nor did Melville find support for what he called "unconditional democracy in all things" among his ancestors or his present family. Melville's double Revolutionary descent, boasting of a maternal grandfather who successfully defended Fort Stanwix against the British and a paternal grandfather who dressed up as an Indian and dumped tea in Boston harbor, graced him with Titan-like forefathers. True, these ancestors testified to Revolutionary greatness, yet these fathers also achieved a distinguished, if not aristocratic, status for the Melvilles and Gansevoorts that no doubt contradicted faith in an "unconditional democracy." His father died when he was twelve, yet he hardly found a surrogate in his father-in-law, Lemuel Shaw, chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. Unlike Cooper's representation of the union between the Whartons and the Dunwoodies, the alliance between the houses of Melville and Shaw no doubt created discomfort for Melville when Judge Shaw surrendered escaped slave Thomas Sims to his master in Savannah by upholding the Fugitive Slave Law. That Shaw not only helped support Melville"s father's widow and her children but patronized Melville's own artistic endeavors certainly acted as a restraining order upon his son-in-law's political beliefs. Melville no doubt accrued advantages from these natal and adopted family legacies that echoed national history, yet at what point did remembering these debts suffuse "the open independence" of his sea with prescriptions of an already written filial identity? As Melville complained in an ambivalent expression of parricidal longing and patriarchal impossibility, "No one is his own sire."[14]

Donald Pease suggests that Moby-Dick is not a work of isolation but a "collective" project dedicated to Hawthorne in recognition of their shared understanding of the often specious character of American political rhetoric. Although he inscribed Moby-Dick to Hawthorne, Melville must have viewed Hawthorne's support of Franklin Pierce's proslavery presidency with aversion. In a letter of June 1, 1851, Melville assumed that his belief in a "ruthless democracy on

all sides" would cause Hawthorne to shy away from him. One critic has called this letter Melville's declaration of independence from Hawthorne. In the same letter that Melville warned Hawthorne of his adherence to "unconditional democracy in all things," he proclaimed his alienation from antebellum cultural expression: "What I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—it will not pay. Yet, altogether, write the other way I cannot."[15]

What way, then, did Melville write? Positioned within a family committed to juridical, national, and ancestral discourses, indeed positioned dans le vrai , one would suppose that he had very little "sea room" to tell and narrate a "ruthless democracy." Only an equally ruthless narrative strategy that could tolerate irony, paradox, and discontinuities like "sane madness" could offer glimpses that momentarily evade prescriptive "slavish" discourses and approach the freedom of Bulkington's vision. Only "ruthless democracy" could counter the "regime of truth."

The Truth of Polyphony and the Fraud of Ethnology

Somewhere between the poles of free will and necessity, somewhere within authorized discourse, Melville developed a strategy he called "the great Art of Telling the Truth,—even though it be covertly, and by snatches"; he wrote fiction using a narrative strategy whose authority was rendered suspect in its own telling. Somewhere between his sardonic suggestion to "Try to get a living by the Truth,—and go to the Soup Societies" and his conviction that American political discourse spoke with authority but not with the truth of democratic principles, Melville incorporated the truth not as subject matter, but as the very mode of telling. Truth does not surface in the story of a fated captain demonically pursuing a dumb brute in the face of prophetic warnings; instead, truth lies in the narrative used to tell the story of that captain and that whale. Ralph Ellison thus observes of Melville: "Whatever else his works were 'about' they also managed to be about democracy." The content of Melville's narrative form is a truth that can be expressed only in the hardly utterable contradictions of racial heterogeneity besieged by American democracy.[16]

Slavery played no part in Melville's "ruthless democracy." As both idea and practice, it sullied the democratic body politic and demo-

cratic narration. Like slave ships that "run away from each other as soon as possible," slavery had no companion concept among the fraternity and freedom of his oceanic democracy (195). Frederick Douglass censured American politicians who acted "like hungry sharks in the bloody wake of a Brazilian slaveship," and four years later, Melville called upon the same image to suggest the solitary, anticommunal pathways of bondage, commenting that only sharks, voracious and self-devouring, "the invariable outriders of all slave ships crossing the Atlantic," provided a community for slavery (235). Melville's unsettling commitment to "ruthless democracy" impels his narrator to radical actions and even more radical strategies of narrative. Lacking any model or precedent, Melville constructed a novelty entitled Moby-Dick that created a polyphony, not simply in terms of the culturally diverse voices of the crew, but in terms of the diverse forms of narrative Ishmael uses to tell his and his shipmates' story.[17]

As the novel ranges from transcendental meditations upon existence to democratic choruses, Ishmael flits in and out of the story. Soon after Ishmael selects a cannibal named Queequeg for his bosom friend, the narrative ceases to be the story of a young sailor, as is Redburn . Rather, it becomes the story of different ways to tell the story of a crew sailing after glimpses of democracy, glimpses that are dangerously susceptible to Ahab's demagoguery. Unlike Ahab, Ishmael does not invent ways to make the crew, in its heterogeneous composition, coalesce around his story of the Pequod . He relinquishes suicidal autobiography to the dramatic democracy of "Midnight, Forecastle." While the delegates of the choruslike crew speak and exchange thoughts, Ishmael remains silent, much in the same way that later he loses track of himself among the ecstatic utterances of an unctuous community of shipmates squeezing spermacetti—"Squeeze! squeeze! squeeze! all the morning long; I squeezed that sperm till I myself almost melted into it" (323). Ishmael dissolves into the crew, becoming one of their number, engaged in the common quest. After he boards the Pequod , he blends into the rigging of the communal narrative, relinquishing his own authorial and sovereign "I" to refocus the narrative's concerns on the many and diverse elements of whaling, as well as the heterogeneous composition of the crew.

Melville's narrative style and polyphonic discourse employ modes of telling particularly suited to situations marked by such

heterogeneity and difference. Only through what Richard Brodhead calls "a conflict of fictions" could a "ruthless democracy" be represented. Brodhead argues that Hawthorne and Melville remained in continual tension with "constitutive conventions of their genre"—the novel—and this tension caused them to eschew any single narrative mode. Moby-Dick resists generic imperatives "to subsume varied material into a unifying and homogeneous narrative mode," privileging instead diverse representational strategies. If democracy is to be "unconditional," as Melville suggested in his letter to Hawthorne, then the narrative that transmits unconditional democracy must shirk off any conditions or conventions that allegiance to one fictional style demands. Only heterogeneous composition could represent the heterogeneous bodies forming the Pequod 's crew.[18]

Melville employed this composite narrative form as a political venture: not simply to tell a different story of America, but to tell differently a story of America. As Ishmael fades in and out of the narrative, he initiates, in the words of Carolyn Porter, a "discursive democracy." Drawing upon Bakhtin's ideas of polyphony, Porter argues that Ishmael speaks in a "double-voiced discourse" that appropriates authorized discourse at the same time that he parodies that discourse, undermining the validity of the tongue he has chosen to speak. In the same way that the parricidal urge in national narratives of Washington at once acclaims the text and thwarts its coherence, Ishmael acts as a textual insurgent, acknowledging a recognized discourse only to plunder it of its authority. Melville accords Ishmael an ironic authority capable of subverting dominant cultural authority. For example, in both "The Advocate" and "The Affidavit," Ishmael employs legalistic discourse to undermine its own credibility with faulty and exaggerated examples about the sperm whale fishery. Whether the prevailing discourse is legalistic, scientific, or philosophical, Ishmael siphons off the discourse's authority by subjecting it to a mixture of irony and parody. Each discourse corresponds to a vision/version of reality, so that, according to Brodhead, "no representation of reality can pretend to a final validity." Without "final validity," there is no consummate authority, and the crew resides in a democratic narrative, precariously prone to incorporation within Ahab's political rhetoric. For the time being, however, the unmanageable sum of these irreconcilable and discordant visions promotes an egalitarian consciousness that relin-

quishes control of the narrative so that others may speak; Ishmael embodies a narrative consciousness that speaks as one sailor among the thirty-man crew, as one more isolato forming the "Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth" (108). Ishmael's voice is "a virtual sponge, capable of soaking up an infinite number of voices and squeezing out their discourse into a pool as large as the ocean he sails," writes Porter.[19]

Yet radical democracy causes Ishmael embarrassment. It is a political, sexual, and cultural vision that cannot be sustained without breeding dangerous conflict and acute self-awareness for its practitioners. Thus, while squeezing sperm, Ishmael finds himself apologizing to his shipmates for his reckless and transcendental passion, which leads him to mistake their hands for "gentle globules" (323). But rather than apologize to the reader or confess a sense of embarrassment for his fraternal feelings, Ishmael interrupts "A Squeeze of the Hand" in midcourse to speak of the stark preparations of the tryworks, whose mechanical violence mutilates the harmonious universalism just related. He descends into the blubber room among the barefoot cutters, whose stumps that were once toes replace affectionate fingers squeezing sperm. The impulse that leads Ishmael to squeeze "the very milk and sperm of kindness" becomes the source of bodily amputation (323). If the spademan "cuts off one of his own toes, or one of his assistants', would you be very much astonished? Toes are scarce among veteran blubber-room men" (324). The rhetorical question encourages us to answer that, no, these common amputations being so ordinary do not astonish us, though, Ishmael, we are surprised at your mad and exuberant language of squeezing sperm. The quickness with which the narrator's jubilations of fraternity dissipate as the crew prepares the ship to become the factory at sea causes Ishmael and his reader to look back upon the episode of squeezing sperm as the embarrassing ramblings of a utopian dreamer.

Melville the letter writer presents his democratic ideals with similar apprehension to the more politically conservative Hawthorne. He sees with an Ishmael-like timidity his own tendency toward the arrogance of Ahab: "It is but nature to be shy of a mortal who boldly declares" unflinching faith in radical democracy, he wrote to Hawthorne. But Melville could not bridle that Ahab within from autocratically taking up Ishmael's ideas about democracy and

transforming them into parricide of national dimensions. Melville thus "boldly declares" to Hawthorne that "a thief in jail is as honorable a personage as George Washington." And within Moby-Dick , George Washington becomes as honorable as a pagan savage who peddles shrunken heads. In the famous passage where Ishmael experiences salvation from his misanthropy as well as from the cultural prejudices of Christianity, he describes the magnificence of his bedmate Queequeg by way of the unabashed comparison we have already noted:

With much interest I sat watching him. Savage though he was, and hideously marred about the face—at least to my taste—his countenance yet had a something in it which was by no means disagreeable. You cannot hide the soul.... Whether it was, too, that his head being shaved, his forehead was drawn out in freer and brighter relief, and looked more expansive than it otherwise would, this I will not venture to decide; but certain it was his head was phrenologically an excellent one. It may seem ridiculous, but it reminded me of General Washington's head, as seen in the popular busts of him. It had the same long regularly graded retreating slope from above the brows, which were likewise projecting, like two long promontories thickly wooded on top. Queequeg was George Washington cannibalistically developed. (58)

To counteract the potentially jarring nature of his metaphor, Ishmael here puts forth a comparison tentatively developed. Just as the stares of the New Bedford citizens accost Ishmael and his bosom friend as they make their way through town streets, Ishmael the narrator knows his description will provoke, at the very least, the astonishment of the reader. Proceeding with clauses to explicate and clarify his position, all of which delay the final rushed assertion, he confesses his conceit is "ridiculous." His authority is ironic not simply because it subverts authorized discourses, but because it participates in its own destabilization. Ishmael takes on the same embarrassed tone Melville used when he communicated to Hawthorne his sentiments about Washington, admitting that the analogy was "ludicrous." Yet Melville goes on to affirm the "Truth" of his brash egalitarian comparison, knowing all the while it lacks any authority in the patrifilial culture of antebellum America: "This is ludicrous. But Truth is the silliest thing under the sun." As narrative, as an attempt to speak political "Truth," "ruthless democracy" will not be logical, even, or regular—otherwise it could easily succumb to the regime of truth.[20]

In the same way that Harvey Birch's association with Washington testifies to the spy's true nobility, here, Ishmael's metaphor seemingly works to the enhancement of Queequeg and not to the discredit of Washington—and if it does, Ishmael is quick to apologize. He adopts the prose of exuberance, licensed to use hyperbole. The metaphor works to uplift Queequeg, and Ishmael hopes that his statement can accomplish its missionary purpose without tainting Washington. Ishmael thus knows that what he says "may seem ridiculous," but certain it is that his analogy contains a radical, nay, sacrilegious, political dimension. If audiences found undignified Cooper's coupling of Washington and a common peddler-spy, Ishmael's parallel hardly would appease anyone when it threatened the symbolic father of freedom by rhetorically chaining him to a dusky pagan. The urbane planter thus collides with the uncivilized islander, who, as Eleanor Simpson suggests, is described as a Negro.[21] The fool's unauthorized description often speaks the truth: Ishmael's likening of Queequeg to Washington, "ridiculous" though it may be, conjures up the dark side of American narrative, a side marked simultaneously by truth, uneasily straddling democracy and slavery, and by a lack of authority to tell that truth. Though Ishmael first displaces Queequeg to the imaginary Kokovoko and not Africa, the conjunction of the father of his country with an idolatrous pagan nevertheless indirectly points to the incongruity upsetting both Washington as an authoritative symbol and American narrative as legitimate promise. That Ishmael reports Queequeg's native island lies to "the West and South" leads the reader from New Bedford, not to Polynesia, but to the territories received from the Mexican-American War as the bounty of Manifest Destiny, whose identity as free or slave was in contention. Geographic crises replicate and reproduce themselves on the symbolic landscape, miring Washington's identity, as well as the identities of his descendants, in the incongruous personalities of a civilized free man and the islander whom Bildad curses as the "son of darkness" (87).

Ishmael, however, can imply this truth only by way of displacement.[22] In the abyss separating Melville's own truth lacking authority from the national authority lacking truth, displacement arises as an effective strategy. Not just in terms of a subversive content that sports with fantastic islands as political allegory, but in his very mode of telling does he come at truth "covertly, and by snatches." That is,

in order for Ishmael to reincarnate Washington in the body of a heathen, he must undermine his own authority and apologize for the truth he presents as though it were an oddity of his own brain. Indeed, for Ishmael to speak the truth, he must extricate himself as best he can from an America in crisis; he must, like Bulkington, reject the "slavish shore" that impedes the perception of truth. Ishmael is last seen, shipwrecked, but still afloat in the middle of the Pacific, yet as an author, Melville still inhabited the "slavish shore," and he lived, at the time of Moby-Dick 's composition, both in the family that upheld the Fugitive Slave Law by returning Thomas Sims to a public whipping and in an America debating the Compromise of 1850. Though like his narrator, Melville may have stood apart as he perceived a social fabric of narrative and nation where democratic practices corrupted democratic ideals, he was still dans le vrai of authorized discourse. The power of America's discourses proved particularly effective in allowing Congress, faced with same disjunctive controversy, to legislate an artificial yet authoritative closure to effect a compromise declaring freedom and enslavement compatible and mutually enhancing. Congress narrated an expanding vision of America that permitted California to enter the Union as a free state but fell back upon the idea of popular sovereignty to permit slavery in the other territories acquired from Mexico and passed the Fugitive Slave Law. The Compromise of 1850 certainly preserved America through the legislation of consensus and accord, yet as it did so, it unavoidably called into question the totality and storied perfection of the national narrative. Nation and narrative could continue expansion if the gaps in founding logic were overlooked. In other words, in 1850, promise became compromise.

The principles that once initiated perhaps the most remarkable attempt at intentional community were revised and reworded in popular consciousness: during this era of supplemented and amended narrative, the Richmond Enquirer explained this alternative reading: "In this country alone does perfect equality of civil and social privilege exist among the white population, and it exists solely because we have black slaves. Freedom is not possible without slavery." Slavery, if one compromised democratic discourse, did not appear to be incongruous with freedom, but, in fact, made for a more profound experience of civic freedom. "The situation of the slave-owner," wrote a supporter of the Confederacy, "qualifies him, in an

eminent degree, for discharging the duties of a free citizen. His leisure enables him to cultivate his intellectual powers, and his condition of independence places him beyond the reach of demagogues and corruption." If America could compromise in this way, Melville and Ishmael could compromise Washington with comparisons to thieves and cannibals. Their ability to make these comparisons reflects a culture whose authority to enforce a narrative—especially one that told an inconsistent story as though it were consistent—was as titular as its symbols. Ironic subversion thus presented itself to Melville and his narrator not only out of the gap between truth and national authority, but out of the seams of that authority itself. Melville and Ishmael spoke discourses that repeated American national authority, but, to recall Bhabha's account of colonial discourse, the discourses they reproduced were "uttered inter dicta ." It is in one such eruption or moment of "sane madness" that Ishmael compromises the patriarchal founder of America, likening Washington to his cultural opposite. His patriotism is one among many ritual repetitions of Washington, but it is also one of the most "ridiculous"—that is, if parricide is a laughing matter. In the contradictory echoes of homage as criticism, promise as compromise, and Washington as Queequeg, patriotic repetition takes on a subversive, if not murderous, intent toward the patriarchal myths, legacies, and institutions that undergirded the nation.[23]

Whereas the Richmond Enquirer adjusted the principles of the narrative to fit the times, other discourses, scientifically developed, functioned as critical commentaries that amended social actualities to fit the new narrative. In his Treatise on Sociology (1854), Henry Hughes concluded: "In the United States South, there are no slaves. Those States are warrantee-commonwealths." Bridging divisions between the industrial ethics of the North and the agrarian ideology of the South, Hughes stressed economic affinities, calling the slave-holder a "prudent capitalist." Ethnologists like J. C. Nott and George R. Gliddon shored up the makeshift narrative with a spurious mixture of biology, history, and anthropology. South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun found ammunition in their ethnological substantiation of racial stereotypes, using their arguments to encourage expansion of the peculiar institution. Nott's and Gliddon's exhaustive study Types of Mankind "proved" the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race over others whose physical and mental inferiorities

supposedly threatened the continued advancement of civilization. America was not to understand literally Paul's words that God "hath made of one blood all nations of men," for indeed the white and dark races, as ethnology's interpretation of biblical history and anatomy attested, were physically distinct and should remain so. "The Negro and other unintellectual types have been shown ... to possess heads much smaller, by actual measurement in cubic inches, than the white races," reported Nott and Gliddon. Democracy, said the antebellum ethnologist, can be implemented successfully only among whites, for only they are historically and biologically conditioned for self-determination; in contrast., "dark -skinned races, history attests are only fit for military governments." This discourse implied that founding principles needed to be reexamined in the light (and darkness) of these new findings in the human sciences. Apparent contradictions between freedom and enslavement were only the "facts" of nature and biology, not the result of human failing or hypocrisy.[24]

Ishmael's perception of Queequeg's high and noble brow refutes the ethnologist's narrative that acted as a varnish on the disintegrating national narrative. Both the "son of darkness" and the founding father exhibit the cranial capacity to conceive of democratic principles. Even Ishmael, prone to "deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off," can experience the regeneration of democracy (23). Despite having a cranium choked with grim Puritanic loomings, Ishmael, too, can conceive of ideals like brotherhood and universal fraternity. Queequeg provides the impetus for his redemption, demonstrating the equality of their crania—and thus their equal capacity for freedom, democracy, and good—when he clasps Ishmael about the waist and "pressed his forehead against mine" (59). And Queequeg concretely reaffirms his commitment to the fundamental ethics of the joint-stock company of humanity by repeatedly saving castaways, among them an African named Daggoo trapped in the sinking head of a whale, a white landlubber who has just called him "the devil," and a refugee from the merchant marine stricken with a bout of misanthropy (65). Once Queequeg's actions indicate the fallacious nature of racist biological classification, Ishmael employs his double-voiced discourse to appropriate and subvert ethnology's authority. That is, through Queequeg, a darkskinned heathen whose visible being renders him suspect in the Puritan vision, Ishmael finds the impetus to examine the cultural

authority of his era. Queequeg, who lacks any authority while on the mainland of the United States—even when he tries to use a cultural artifact like a wheelbarrow, he shows his distance from a basic cultural literacy—ironically provides Ishmael with the authority to parody and undermine the discourses of that dominant culture.

Just as ethnology distinguished three types of mankind by identifying the black race, the sons of Ham; the brownish yellow race, the sons of Shem; and the white race, the sons of Japeth, Ishmael proposes the classificatory system of cetology. His system allows him to discriminate along with Linnaeus: "I hereby separate the whales from the fish" (117). With meticulous and scientific care, Ishmael divides his study into books, folios, chapters, and subheadings. Textual classification becomes biological classification and allows this amateur naturalist to discriminate authoritatively between sperm whales, baleen whales, and porpoises. Yet Ishmael soon undercuts his newly pilfered authority by extending it too far, using it to make untenable hypotheses. He parodies the authority that permits one to make discriminating judgments between types of whales or types of mankind.[25] Of humpback whales, Ishmael the taxonomist writes: "He is the most gamesome and light-hearted of all the whales, making more gay foam and white water generally than any other of them" (121). The improbable nature of sketching an entire whale group's personality repeats ethnology's fraudulent categorization of a "light-hearted" race, or William Smith's conclusion in Lectures on the Philosophy and Practice of Slavery (1856), which ascertains from an assumption of black "intellectual inferiority" that slaves "are the most cheerful and, indeed, merry class of people we have amongst us."[26]

The socially enmeshed "truth" that props up observation—whether it is a description that "foam" is "gay" or slaves inferior—leads to untenable conclusions that force Ishmael to view suspiciously the foundations of his governing classification. Thus, Ishmael, like any good researcher, tells us his sources, in this case, Linnaeus's "System of Nature, A.D. 1776" (117). What seems a scrupulous piece of scholarship is in actuality an error. Linnaeus's Systema Naturae first appeared in 1735, and the important tenth addition was issued in 1753. Under the guise of scholarly authority, Ishmael substitutes the date of the Declaration of Independence for the date when the Swedish botanist separated whales from fish. Rather than

producing skepticism about Linnaeus, Ishmael intends to question the meaning of 1776, to classify it as a year that, despite its pretensions to equality, never instituted practices to actualize the dictates of freedom. Disagreeing with Linnaeus by asserting that "the whale is a fish," Ishmael abjures separation, proposing in its place a system of inclusion where types of fish are not segregated: "By the above definition of what a whale is, I do by no means exclude from the leviathanic brotherhood any sea creature." (118) Ishmael consents momentarily to speaking dans le vrai of biological discourse so that he can then misuse its authority to deflate an uncritical political discourse. By the ironic authorization of a cetology, we learn blacks are not separated from whites, but integrated, as whales and fish are, as Queequeg and Ishmael are, in a universal fraternity.

"Unconditional democracy in all things," Melville realized, was a radical project requiring that Ishmael encode his ideas about democracy in the discourse of taxonomy. Indeed, he was doing no more than the humanist researchers writing dans le vrai of ethnological discourse who "discovered" historical and biological predeterminations for black slavery. An all-important difference, however, lies in the fact that Ishmael remains an isolato, floating above the depths plumbed by his parodic discourse, while ethnologists existed as part of a federation where various discourses (biological, legal, historical) intersected and supported one another. Not only did ethnologists like Nott and Gliddon find compatriots in the ranks of a social critic like Hughes, or in the pages of a political commentator like James Fenimore Cooper, or in the impassioned rhetoric and magnetizing presence of an orator like Calhoun. They were also part of a historical brotherhood that stretched back to the founding fathers. In Notes on the State of Virginia , Jefferson established a textual foundation upon observations of geography, plants, and animals to comment, however tentatively, upon his black slaves' animal-like sensuality and intellectual slowness. In contrast, Ishmael stands alone and embarrassed in the desert of his own rhetoric, able to associate with other discourses only in a "ludicrous," if not subversive, manner.

Radical truth telling demands consideration of a cautionary postscript, however. Ishmael's beliefs about democracy could cause more than embarrassment and alienation; such a democracy is fraught with the danger of its own "ruthless" and frantic nature. Ruthlessly democratic form leads to discursive experiments like "Midnight,

Forecastle." Here, Ishmael, the narrative authority, disappears, and the text presents unmediated the crew as chorus, a central element of drama in Athenian democracy, now the polis of the Pequod . They alternate between joining together under the textual designation of "ALL" and reasserting their individual characters with their opinions about whaling, the sea, and women. The chorus thus unites an assortment of thirty men into a crew that nevertheless preserves the diversity of sailors from Malta, Nantucket, China, and Tahiti. But this democracy, including whites and blacks, splinters over racial conflict. The chapter ends in a scuffle echoed by an atmospheric squall: nothing more can be told; the communally spun and diverse narrative stalls; the reminiscing about Tahitian girls, the speculations about Ahab, the singing of mariners' songs, indeed, the development of the dramatic chorus, dissipates as the Spanish sailor comes at the African Daggoo with a knife. "Unconditional democracy" may be too radical; it may join together racially different citizens who can interact only in a volatile and violent manner.

The Power of Blackness

More dangerous to democracy than the racial strife among the crew is the threat Ahab poses. Because his command seems egalitarian, Ahab's leadership becomes that much more insidious to the collective consciousness of the crew. He makes none of the distinctions based upon the social hierarchies of race or class that circulate on shore; he admits Pip to the intimacy of his cabin as readily as he sheds a furtive tear telling Starbuck of his wife ashore. His rule is democratic, degrading no man because of his condition. The only exception to his thinking is himself. As Starbuck cynically comments, "Aye, he would be democrat to all above; look, how he lords it over all below!" (143) Ahab adopts the role of charismatic leader whose proud defiance summons up a heroic Prometheus of the American spirit: "Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I'd strike the sun if it insulted me. For could the sun do that, then I could do the other.... What I've dared, I've willed; and what I've willed, I'll do!" (139,142). Against the frontier, savages, or British pharaohs, a man of Ahab's stature leads the people out of the wilderness through the exertion of his indomitable will. In him, we see the American hero; his sheer presence, burning with "an infinity of firmest fortitude, a determinate, unsurrenderable willful-

ness," fascinates Ishmael and the crew (110). Ahab "is the shaman ," writes Richard Chase, "that is, the religious leader [who] ... attains some of the knowledge and power of the gods. The shaman is usually deeply neurotic and sometimes epileptic—the savior with the neurosis. Again, Ahab is the culture hero (though a false one) who kills the monsters, making man's life possible"[27] Ahab appears as the true demagogue in contrast to Gabriel of the Jeroboam , a false prophet whose mysticism suppresses a group of frightened and superstitious sailors. Gabriel is the demagogue as rabble-rouser; Ahab, on the other hand, at first suggests an older meaning of demagogue—a leader of the people.

Skillful oratory, awe-imposing presence, mental prowess, and a vision all constitute Ahab's political genius. Yet all these qualities that compel the thirty men to follow his will, recreating them as the crew of the Pequod , would remain inert if Ahab did not possess a symbolic vehicle to articulate and manifest his power. Through his brilliant understanding of ritual, Ahab reveals his will and word with potency. In "The Quarter-Deck," Ahab conflates the rationality of the social contract with the demonic dynamism of religious communion to mold the crew to his purpose. Even the narrator adheres to this pact, dropping the narrative of his friendship with Queequeg to clasp hands with the other seamen already stuck fast to Ahab's vengeance. Ishmael's retrospective narrative may intimate moments of discursive resistance, but he must admit "my shouts had gone up with the rest; my oath had wielded with theirs.... A wild, mystical, sympathetical feeling was in me; Ahab's quenchless feud seemed mine" (149–50).[28] This single-minded quest whittles away other narrative possibilities, leaving only an American story of progress that ignores digressions, such as a pagan's Ramadan or the political lessons of whale classification. Any episodes that depart from the unyielding linearity of the hunt, any ironies that twist expectations or interject variations of the captain's mission, are left ashore at the Spouter Inn. Unlike an authority such as Ishmael's, which derails itself in its own subversion, Ahab's authority is imperious, wholly consumed by pursuit of an undifferentiated mass of whiteness.

Under Ahab's command, narratives become narrative, and the challenges of cultural difference are included in this subsumption. Within his ritual orchestrations Ahab continually invokes the race of his pagan harpooners—yet because it is ritual, this invocation re-

duces their being to only a symbolic dimension. In the ceremonial rites of the political shaman, Queequeg, Daggoo, and Tashtego forfeit their varied humanity to the democratic gathering Ahab convenes. In other words, the symbolic import of their skin replaces the truly human essence in Queequeg that Ishmael discovered out of prejudice and fear and that provided the ground for interracial friendship. Thus, although Ahab calls Queequeg, Daggoo, and Tashtego "my three pagan kinsmen" because like him they have seen and pulled after the white whale, his interest lies in neither brotherhood nor difference (141). He understands the harpooners neither as men nor isolatoes, but as symbolic entities he can exploit to ratify his quest. In Ahab's political demonology, the three become satanic cupbearers who lend pomp and mystical shamanism to the ceremony played out in "The Quarter-Deck." "Ahab is Conjur Man. He invokes his own evil world. He himself uses black magic to achieve his vengeful ends," writes Charles Olson.[29]

Transforming these nonwhites into "sweet cardinals" and redefining their harpoon irons as "murderous chalices," Ahab presides over a barbaric communion. Gone are the heterogeneous stories of fear and desire that populated the forecastle at midnight. In Ahab's words the sailors ordain themselves into an "indissoluble league." "The frantic crew" responds uniformly to the ritual, drinking together as one body from the inverted harpoon tips of Queequeg, Daggoo, and Tashtego (141). Later, in "The Forge," these same three find their bodies manipulated to baptize Ahab's hunt; confronted by the crew's questioning of the pact they have formed, Ahab reaffirms the oath of "The Quarter-Deck" by symbolically sanctifying his imperial mission with blood drawn from heathen flesh. Tempering his harpoon with this blood, Ahab acts as the mad priest: "Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli!" (373).[30]

Melville took Ahab's blasphemous ritual as the informing principle of his own writing. Warning Hawthorne that "this is a rather crazy letter in some respects," he wrote on June 29, 1851, "this is the book's motto (the secret one), Ego non baptiso te in nomine—but make out the rest yourself." He desired to make a heroic Ahab-like assertion of willful independence, but the Ishmael within was too reluctant to continue. Melville refused to utter the word patris , for his book undermined the patriarchal authority of American scientific, legislative, and political discourse; it was an omission that prepared

the conditions for "ruthless democracy" even as it left the narrative project susceptible to the insertion of diabolic evil. Apprehensive that Hawthorne would not embrace his views, Melville ended the letter at this point. Yet in doing so, he forced Hawthorne to "make out the rest yourself" and scorn the father; Melville subtly enrolled his friend in that democracy by insisting upon his participatory interpretation, leaving him to complete the parricidal sacrilege. Later, in November of the same year, Melville's awareness of the demagogue's ability to galvanize the people to a darkly conceived mission caused him to confide again in Hawthorne. "I have written a wicked book," he confessed, without apologizing or asking forgiveness, "and feel as spotless as a lamb." Still, Melville could not forget the lesson of Ahab: a false demagoguery can warp the democratic promise into a tale of reckless dimensions that the people nevertheless follow because of their adherence to the original covenant as given by national narrative. Whether citizen or shipmate, each retains enthusiasm for a compact that promises to realize the final, moral end of a destined narrative.[31]

This ambivalence—acknowledging a malevolent intent alongside of virtuous, lamblike self-conviction—reproduces itself as a complex political stance that allows Ishmael to affirm the narrative compact even as he recognizes the bankrupt nature of national narrative, even as he dissents from the final revelation of its ending. Ishmael consents to Ahab's vengeful quest, admitting that "my shouts had gone up with the rest," yet this affirmation does not compromise his ability to articulate intellectual dissent from Ahab. As with any citizen of national culture, Ishmael realizes, like Melville, that one must first consent in order to dissent, that one must first enter a discourse to thwart the truth claims of that discourse. Thus, in the chapter following his admission of participation in Ahab's "quenchless feud," Ishmael manipulates the narrative to separate himself from the captain's plot: "What the white whale was to Ahab, has been hinted; what, at times, he was to me, as yet remains unsaid" (157). Likewise, Melville as a citizen who took pride in his double Revolutionary descent at the same time vented deep-seated reservations about an American narrative indebted to plots of imperialism, Indian removal, and slavery. The author of Moby-Dick may have felt "as spotless as a lamb," but as a citizen of the United States expanding slavery under the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, Melville ineluctably saw the un-

derside of the American narrative—a moral blackness without integrity that sinfully compromised the legacy of the fathers.

As unregenerate pagans who can make no similar claim to spotlessness, Queequeg, Daggoo, and Tashtego embody a diabolical darkness—a cultural assumption Ahab exploits with his understanding of the "great power of blackness." Melville had powerfully figured the dimensions and effects of a metaphysical blackness in the year preceding Moby-Dick 's publication in the "Hawthorne and His Mosses" review. Although Ahab himself ignores the forebodings of the reversed compass needles or the coffin used as a life buoy, he knows the dark side of the Puritan mind and its weakness for allegory. Through his knowledge of man's fixation upon "blackness, ten times black," he manipulates the democratic consciousness of the crew. To a mind like Ishmael's, steeped in the Puritan legacy of "Innate Depravity and Original Sin," blackness generates a certain compulsion and attraction. Reviewing Mosses from an Old Manse , Melville spoke of his own inexplicable and Ishmael-like desire to investigate blackness: "Now it is that blackness in Hawthorne, of which I have spoken, that so fixes and fascinates me." In addition to Melville, crew members like Ishmael, Bulkington, and Ahab peer into blackness in their searches for truth. The depths of the sea allure them, as do dark figures exterior to discourse dans le vrai who, because of their marginalized status, hint at a nonprescribed truth. Ishmael chooses as his friend the non-Westerner Queequeg, whose tattooed skin transmits "a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth," and Ahab showers paternal kindness upon the castaway Pip, who "saw God's foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad" (368, 322). Perhaps ever undecipherable, truth may reside in these alien and black forms, and thus they hold a certain fascination for the crew and for Ishmael's narrative. But as Ahab represents the harpooners and Pip to the crew, as Ahab translates their intuitive capacities of revelation into political rhetoric for his quarrel, the harpooners and Pip cease to promise truth. Their blackness does not lead to depth, but to a superficial appeal designed to rally the crew around the demagogue's inexotable hunt.[32]

Unable to claim the divine calling that authorized the Puritan errand into the wilderness and the American continuation of these labors, Ahab requires a religious symbology to shroud his nefarious

errand in authority. He becomes a political sorcerer who combines ritual and alienation to convert the literal blackness of these natives' skins into the symbolic "blackness of darkness beyond."[33] During the religiously charged rituals of "The Quarter-Deck," "The Forge," and "The Candles," Ahab reifies the skins of the Indian, African, and Polynesian into an image of a potent, spiritually symbolic blackness that he then uses to exploit psychologically the wills of the crew. The harpooners act as attendants who perform a perverse sanctification of their captain, becoming iconic embodiments of blackness to which the crew is susceptible. In the same way that a forest gathering at midnight demonically attracts the faith of Young Goodman Brown in Hawthorne's story, Ahab's masterful ritual coerces Ishmael and the other sailors to adhere to his chosen destiny. Ahab addresses the crew through the symbolic bodies of the pagan harpooners, who make manifest his incontrovertible will and the possessive quality of his power. They are powerful black forms—after all, they fling the iron into the life of leviathan—who surrender their physical, human being up to Ahab, becoming metaphysical indicators of his prowess that the crew cannot deny. Each man of the crew drinks "the fiery waters" (141) poured into the harpoon sockets; each man affirms this covenant, made not from the promise of God, but forged out of the dark side of free will. Like a member of the Puritan community, the seamen individually consent to the contract proposed by Ahab; but like Young Goodman Brown, who chooses to attend the coven at midnight, they are manipulated by their own human susceptibility to the symbolism of the harpooners' marginalized, dusky forms. The dark sailors catalyze Ahab's bonds with the crew; they become the conduits through which the men affirm the covenant.

During the electrical storm, when the crew raises "a half mutinous cry," Ahab corrals their passion within the proven strength of ritualistic politics (385). He snatches up the harpoon tempered by heathen blood and waves it above the heads of the crew, reminding them of the covenant they have wildly ratified: "All your oaths to hunt the White Whale are as binding as mine" (385). He swears "to transfix with it [the harpoon] the first sailor that but cast loose a rope's end" in defiance (385). Ahab not only threatens physical violence to "transfix" or impale the first transgressor of the covenant, but he also promises to "transfix," to captivate, the wills of those who oppose them—just as Hawthorne's blackness "fixes and fascinates" Melville.

And Ahab fulfills this latter promise: in this crucial situation, he returns to ritual; he manipulates the flaming harpoon sanctified by blackness to incarnate a political symbol that reminds the crew of a host of previous rituals to which they have already consented. Awed by the symbolism of the Black Mass, the men can do no more than murmur their dissent; the ritualized arena of politics leaves no space to formulate a will counter to Ahab's. The captain has shrewdly removed debate and dissent onto the irrefutable ground of ritual. Ahab performs what Donald Pease calls "cultural persuasion," a rhetorical strategy that effects "the displacement of potentially disorienting political arguments onto a context where the unquestioned ground—the ideological subtext justifying political dissent—can empty them of their historical specificity and replace them with ideological principles."[34]

Under Ahab's dominion, the racial identities of the harpooners are displaced in this manner, their culturally specific humanity subsumed by a symbolism that ratifies the whole. Queequeg climbs from the rank of harpooner to become the representative of which Hobbes spoke: that is, his black body represents the body politic, bearing and articulating the covenant to the crew. Like the other harpooners, he surrenders his body to the domain of political demonology where ritual alienates him from his body, abstracting it until it acquires a symbolic dimension. Queequeg shares more with Washington than the head size noted by Ishmael; he, too, is a narrative surface where a collectivity reads the covenant. Yet a major difference between founding father and noble savage cannot escape notice; unlike the Washington figured by the antebellum era, Queequeg is alive. In becoming political in this symbolic sense, Queequeg is abstracted from his humanity, reduced to a representative body that slavishly carries the significances Ahab intends. Queequeg's body, inscribed with a truth in the form of tattooed "hieroglyphic marks" he himself cannot read, vanishes, and what remains is brought dans le vrai . As represented to the crew by Ahab, Queequeg is contained within a political rhetoric whose regulations and significances Ahab alone controls.

Queequeg occupies the position of the American slave denied autonomy of his body, defined as a lesser human by the prevailing authorized discourses of antebellum culture. Even within the discourse of abolition, the black body surrendered up its physicality to

become an alienated surface articulating agendas foreign to the slave's interest. Female abolitionists often rhetorically exploited the figure of the black slave, forcing it to transmute its own statements of freedom into women's concerns for suffrage or a testimony of the transcendental inner purity of religion. Although Uncle Tom's Cabin takes its name from a black slave, that slave lacks any physical dimension; for Stowe, Uncle Tom is a metaphysical embodiment of Christian dogma; his character is based upon the denial of his flesh that suffers. For James Baldwin, the theological and sentimental aspects of Stowe's novel that make the dark-skinned slaves superficial and inhumane representations of blackness tell "a lie more palatable than the truth." Devoid of the humanness whose recognition serves as the basis for democracy, Queequeg and his fellow pagans seem empty shells incapable of voicing a subjectivity, of making manifest a being who suffers as all citizens do. Each harpooner is reduced to a rhetorical configuration after the manner in which Foucault speaks of the body politic: "the body is also directly involved in a political field; power relations have an immediate hold upon it; they invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs."[35]