Desert Fury , Mon Amour

David Ehrenstein

For Vito Russo and Richard Dyer

Vol. 41, no. 4 (Summer 1988): 2–12.

Pre-credit Sequence

It would seem that we know something about the cinema. The past decade has witnessed no end of theoretical incursions—linguistic, psychoanalytic, technohistorical, feminist—into an audiovisual technique heretofore seen solely as the province of wild-eyed devotees less concerned with whys and wherefores than sensations and sensibilities. Reams of copy have shot from an ever-growing academic superstructure armed to the teeth with methodological weaponry designed to blast apart not merely the nature of the cinematic beast but human consciousness itself. Yet for all of the work that's been done, critical theory has failed to evolve into critical practice . The cinema today remains as essentially unexamined as it was at the inception of this analytical jamboree—a quandary, a mystery, a mess.

"Like critics, like historians, but in slightly different ways, theoreticians often help to maintain the cinema in the imaginary enclosure of a pure love," claims Christian Metz.[1] But in truth the ways of critics, historians, and theoreticians aren't different. Theory has consistently claimed for itself a place apart—a cultural higher ground above the fray of common strife that Metz has so justly identified as the "institution" of cinema. "To be a theoretician of the cinema," Metz writes, "one should ideally no longer love the cinema and yet still love it: loved it a lot and only have detached oneself from it by taking it up again from the other end, taking it as the target for the very same scopic drive which had made one love it. Have broken with it, as certain relationships are broken, not in order to move on to something else, but in order to return to it at the next bend in the spiral. Carry the institution inside one still so that it is in a place accessible to self-analysis, but carry it there as a distinct instance which does not over-infiltrate the rest of the ego with the thousand paralyzing bonds of a tender unconditionality. Not have forgotten what the cinephile one used to be was like, in all the details of his affective inflections, in the three dimensions of his living being, and yet no longer be invaded by him: not have lost sight of him, but be keeping

an eye on him. Finally, be him and not be him, since all in these are the two conditions on which one can speak of him."[2]

The language suggests a lover attempting to renegotiate a relationship with a mistress "needed" yet not quite "desired" as before. Metz—elegant, passionate, decorous, precise—can't help but give the impression of a writer caught up in a vast preamble to a subject whose discussion he fears elucidating fully. To speak more frankly would risk engagement with that "tender unconditionality" of the cinema's affectivity. And to do so would burst the bubble of quasi-scientific objectivity theorists hold so dear. Metz's Hamlet-like "Be and not be" is a frank admission of his awareness of this epistemological cul-de-sac—an awareness not at all apparent among others theoretically disposed. They're too busy whipping up methodological smokescreens to disguise or deny the critical proscriptiveness inherent in their projects. Yet like some low-grade cultural infection, clear critical biases continue to inhabit these discourses, wending their way through the most blandly bloodless prose—dust-dry treatises invariably opening with that most dreaded of academic invocations: "This paper . . ."

What is to be done, after all, with articles claiming to address notions of cinematic Space, Time, and History, that insist on promulgating the works of Oshima and Straub-Huillet as untouchable ideals?[3] What gain is to be made with theories trafficking amidst the deified likes of Ford, Sternberg, or Cukor—ostensibly examining "form" yet keeping the content of auteur -based idealism intact?[4] How is the study of narrative served by taking the terminology of the Russian formalists, then skewering it on some three decades of traditionally received wisdom regarding the evolution of Hollywood, the "New Wave," Soviet cinema in the twenties, etc.?[5] How can feminist battles with the "male gaze"[6] be waged by exposing Michael Snow's enthrallment to it on the one hand, then falling back to embrace the likes of Nicolas Roeg on the other?[7] In short the Question Cinema: Is theory at base nothing more than a somewhat ostentatiously rarefied exercise in nostalgia?

No need to ask about the actual progress of the cinema amidst this academic wool-gathering round retro Hollywood "classicism." It's gone its own way, serenely indifferent, instinctively decadent. Expanding itself on the one end—thanks to increasingly expensive production procedures—it's contracted on the other, the better to squeeze itself into its new home-video format. As this grotesque cyborg bellows and wheezes its way across the culture its means and ends become increasingly difficult to gauge. It's not merely the bipartite beast of FilmVideo that must be addressed, but the hydra-headed monster of "Media" as well: network television, newspapers, magazines, tabloids, opinion polls, and computerized informational data banks. All these areas, intimately interconnected, subdivide as well into such multicellular organisms as fashion layouts, rock videos, talk shows, pop recordings, live televised news reports, and made-for-TV "Movies of the Week."

Desert Fury

The hesitancy and doubt swirling about Metz's "attempt" at bringing together "Freudian psychoanalysis" and the "cinematic signifier" to produce what he, with touchingly tremulous modesty, refers to as a mere "contribution" to film theory speaks volumes. Everything remains to be said about the cinema. The problem, never really faced, is that there is no simple way to say it.

A Film of No Importance

In the end it all comes down to Desert Fury. Desert Fury ? You haven't heard of it? Of course you haven't. Why should you? A 1947 Paramount release starring Lizabeth Scott and Burt Lancaster, this turgid melodrama about a gambling casino owner's daughter infatuated with an underworld gambler suspected of murder figures in no known pantheon or cult. Its director, Lewis Allen, is devoid of auteur status. Its performances are, by and large, not of award-winning stature. Its composer, Miklos Rozsa, has surely written more interesting musical scores.

Shot in color largely on studio sets representing outdoor locales (there was some actual location shooting as well), Desert Fury 's not-quite-noir plot makes it the odd-film-out among the equally florid programmers produced during the same period (I Walk Alone, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The File on Thelma Jordan ). You aren't likely to find Desert Fury listed on a revival or repertory house schedule. It isn't available on home video. At best you might be able to catch it in some 3 a.m. slot on local television, or unspooled some afternoon when rain cancels a baseball game. And why not? It's "just a movie"—produced, consumed, forgotten. Not good. Not bad. Mediocre. In fact, one might even go so far as to call it quintessentially mediocre.

Of course to invoke notions of mediocrity is to evoke the specter of critical qualitativeness so dreaded by theoretical cadres, committed as they are to the promulgation of the notion of "value-free" analyses. Still, it wouldn't be going out on much of a limb to state that the diegesis of Desert Fury lacks the textual complexity found in such pantheon favorites as Young Mr. Lincoln, The Pirate, Touch of Evil, North by Northwest , or that most persistently picked of theoretical plums, Letter From an Unknown Woman .

The production of Desert Fury plainly involved choices of camera placement, focal length, lighting, sound mixing, musical scoring, and the like, perfectly commensurate with studio practices of the late forties at their most routine. The script by Robert Rossen, adapted from a Saturday Evening Post serial by Ramona Stewart, is workmanlike but formally quite undistinguished, holding as it does to a simple linear dramatic progression, unities of Time, Place, and Action, and such time-honored melodramatic conventions as "Fate" and "Ironic Coincidence" in the pulling together of otherwise unlinked aspects of plot and characterization. You've seen its like before, and all things being equal you'll doubtless see it again.

And yet something lingers over Desert Fury —hangs on, suspended in the studio indoor/outdoor air. For this writer (critic? journalist? theorist? historian? film buff?—the terms begin to slip, as well they might as the text begins to pull astride specified object of desire) cannot quite be done with Desert Fury . The heavy-lidded, smokey-voiced ambiance of Lizabeth Scott certainly plays a part in this—particularly in those scenes where she's set against the gleamingly dentalized muscularity of the young Burt Lancaster.[8] A certain Pop Art palimpsest common to late forties product observed in retrospect is part of this picture as well—especially as Desert Fury 's color gives actors, backgrounds, and objects the polished sheen so prized by Richard Hamilton.[9] Mary Astor's performance as Scott's mother is also there to be enjoyed, albeit in a much more straightforward way—the one element of Desert Fury whose quality is not in question. And last but not least there's the novelty of the character played by Wendell Corey—a homosexual psychopath given to dryly cynical asides and sudden violent rages. But then, we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Make no mistake, there's no avoiding the fact that critical congress with Desert Fury risks trafficking with nostalgic indulgence at its most absolute. Yet this is precisely why a Desert Fury is of such intense interest. Standing clear of the swamp of mass-media affection that forever grounds the likes of Casablanca, Gone With the Wind , and Citizen Kane, Desert Fury can be dissected with cool remove. It speaks to cinematic desires barely formed and only half-uttered—that vague itch for "a movie" answered by a compendium of images and sounds that never reach a level that could be called "memorable" yet somehow manage to "divert."

For any theorist worth his or her salt, the next step would be, of course, to scramble for a proper analytical position. All you have to do is scout a specified ground for study, then nail Desert Fury down with an appropriate abstract. Surely there's a grande syntagmatique to scrutinize here. Or perhaps a simple two-shot or two containing some quirk of psychoanalytic import. Feminist interest goes without saying. How does the figure of Lizabeth Scott "speak castration"? Let me count the ways . . .

But the simple, brutal fact of the matter is that all these techniques are very much beside the point.

Trouble in Chuckawalla

It's 1947. Let's go to the movies. What's playing? It's Desert Fury . Who's in it? Burt Lancaster and Lizabeth Scott. What's it about? Well . . .

After having been thrown out of her fifth finishing school, Paula Haller (Lizabeth Scott) has come home to the small desert town of Chuckawalla where her mother Fritzie (Mary Astor) runs the local gambling casino. Paula wants to go to work for her mother. Fritzie would prefer that Paula marry Tom Hanson (Burt Lancaster), the local deputy sherrif. Paula's attracted to Tom but isn't sure she's ready to settle down, especially as Eddie Bendix (John Hodiak) has just come to town. A gambler/gangster from the big city, Bendix and his henchman Johnny Ryan (Wendell Corey) are staying at a ranch outside of town. Years before, Bendix's wife had been killed in a mysterious auto accident on the Chuckawalla bridge, with suspicions of foul play. Paula is attracted to Eddie, and he to her, as she resembles his late wife. Fritzie is opposed to Paula's seeing Eddie, and so is a very possessive Johnny Ryan. Both (separately) plot to keep the pair apart. Eddie and Paula get together nevertheless and defiantly confront Fritzie. In a last-ditch attempt to stop them, Fritzie tells of her own past romance with Eddie. Paula leaves with Eddie nonetheless. On the way out of town the couple run into Johnny. At a roadside restaurant Johnny tells Paula the truth about Eddie—that he arranged his wife's death. Eddie shoots Johnny. Paula drives off with Eddie in pursuit. Tom joins the chase, which ends with

Eddie crashing his car into the Chuckawalla bridge—exactly where his wife died years before. Tom pronounces Eddie dead at the scene. Fritzie arrives and she and Paula make amends. She leaves, and Tom and Paula—also reconciled—walk off together into the setting sun. The end.

It goes without saying that the above summary provides only the most general overview of Desert Fury . It establishes a basis for further discussion, a point of possible entry. But it is only one point. Plot alone can't deal with the morass of images and sounds that calls itself Desert Fury . Consider, for example, the quasi-hypnotic effect created by the blindingly bright shade of blue sky behind Hodiak and Corey's heads as they stand by the bridge in the film's first scene where they enter town, or the dazed look on the face of an extra standing behind Scott in a scene in the casino. Then there's a visual frisson created by cutting between an actual outdoor locale and a studio set of the same place. Think of the picture window in Scott's bedroom—creating a picture-within-a-picture on a screen already chockablock with iconographical bric-a-brac. Then there's that framed black-and-white photo of Scott in Astor's office and the disturbing effect created when Scott stands astride it—which image is more "real"? All of these factors, naturally, come under the heading of "distractions" or "accidents"—they're not "meant" to be seen as narrative integers. But they're nonetheless there .

There too is Desert Fury 's advertising pitch. Itself a narrative, it runs parallel to whatever fragments of the film's actual story it chooses to disclose, playing on a series of alternate associations—roles played by the performers in the past, films Desert Fury hopes to recall as a possible point of appeal. And it is here that we find yet another Desert Fury : "A story that sweeps with sinister and growing menace thru sun-baked desert towns, luxurious ranches, colorful gambling houses to the greatest chase climax ever recorded by cameras."

Terms of Endearment

"Everyone went to the movies in the late forties," claims critic Andrew Sarris: "A disaster like the Gable-Garson Adventure grossed five million domestic, and musical atrocities like Holiday in Mexico and The Dolly Sisters drew lines instead of the flies they would attract today."[10] Consequently most viewers out for an evening's entertainment weren't likely to be deterred by the almost unanimously unfavorable notices Desert Fury received when it made its debut.

"The picture as a whole makes you think of a magnificently decorated package inside which someone has forgotten to place the gift," wrote Archer Winsten in the New York Post . "If you can accept all these automobiles and clothes as a substitute for a story that makes good sense, here's your picture," noted Alton Cook in the World Telegraph . Forty years haven't altered

critical evaluations in any significant way. "Mild drama of love and mystery among gamblers, stolen by Astor in a bristling character portrayal," says the 1987 edition of Leonard Maltin's TV Movies .[11] Audiences exiting Desert Fury in 1947 would very likely have agreed with him. But these same audiences didn't in all likelihood go in to Desert Fury for Mary Astor. Their attention was directed elsewhere—to Lancaster and Scott.

Under contract to the film's producer, Hal Wallis, Lizabeth Scott (born Emma Matzo), with her dusky voice (doubtless modeled after Lauren Bacall) and wave-encrusted hair (echoing the likes of Veronica Lake), was clearly being promoted as the latest in a long line of sultry siren types. In 1941 she made her debut in an undistinguished programmer called Frightened Lady . After a brief hiatus she returned in You Came Along (1945), followed by The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946). She next made her biggest splash opposite Humphrey Bogart in Dead Reckoning (1947). The career of Burt Lancaster was progressing even faster at the time of Desert Fury though he had only two previous films to his credit—The Killers (1946) and Brute Force (1947). Inevitably Desert Fury 's ads boasted "That Killers guy and that Dead Reckoning dame come together as a team of dynamite-and-fire."

What the ads fail to mention is that as far as the film's scenario is concerned the "dynamite-and-fire" is supposedly between Scott and John Hodiak. Hodiak, curiously, gets top billing on the film's credits—over both Scott and Lancaster. One of a number of male not-quite-leads-not-quite-stars of that era, Hodiak's most notable appearances were in Lifeboat (1943), Marriage Is a Private Affair (1944), and The Harvey Girls (1946). His Desert Fury billing bespeaks a canny agent. Yet no agent, however influential, could forestall the onslaught of Scott-Lancaster associations that accrued round Desert Fury 's ads. Couples being the coin of the cinematic realm, Desert Fury 's promotional copy could not help but create one.[12]

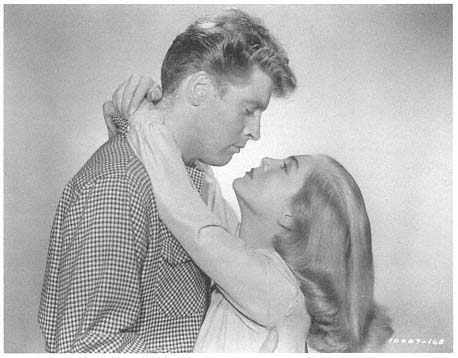

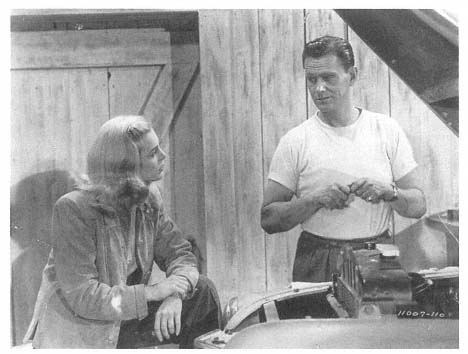

But why Scott-Lancaster rather than Scott-Hodiak as the script clearly indicates? And what about those specially posed Scott-Lancaster photos that go even further in underscoring the relationship between characters who don't truly function as a couple until the film's last few shots? These ballyhoo glossies show Scott and Lancaster in a series of dramatic clinches that have no parallel within the diegesis that calls itself Desert Fury (Scott resting her head on Lancaster's chest, looking up at him rapturously—the "French seam" of her blouse slightly ripped. Lancaster struggling to wrest a gun from Scott's hand, her eyes closed shut as if in an erotic reverie). Clearly Scott-Lancaster are viewed as appealing in a way that Scott-Hodiak are not. Consider Scott's and Lancaster's comparably wavy hair. Consider Lancaster's strapping physique in comparison to Hodiak's, particularly as the latter's far less impressive chest is put on open display in a scene where Scott finds him taking the sun. What's going on here?

John Hodiak in Desert Fury offers us the spectacle of cinema at its most paradoxical. Lancaster is Hodiak's obvious superior on every level. How can Lizabeth Scott even so much as think of preferring John to Burt? One tries to imagine what the film might have been like had the contest been—for want of a better term—more evenly balanced. Imagine, for example, a Desert Fury with Kirk Douglas in the Hodiak role.[13] It certainly would have been a logical choice. Douglas was in fact posed between Scott and Lancaster in their next film, I Walk Alone . However, the center of I Walk Alone is Lancaster's character, not Scott's, and the Douglas character in that film is a wily on-his-game ganglord, not the testy indecisive neurotic played by Hodiak in Desert Fury . Moreover Desert Fury , need we be reminded, is entirely about Lizabeth Scott.

Scott's Paula has to choose between two men—one "good," one "bad." Consequently the concise logic of Hollywood dictates the terms for this choice by making it for her. Plainly the casting of as uncharismatic an actor as John Hodiak serves Desert Fury 's ends. Though the script and dialogue indicates a veritable torrent of passion flowing between Scott and Hodiak, what emerges is an almost palpable lack of lust—particularly in the scenes in which they're required to kiss. The pair set to work with the dogged determination of would-be outdoorsmen who've suddenly had a change of heart while white-water-rafting in the Rockies.

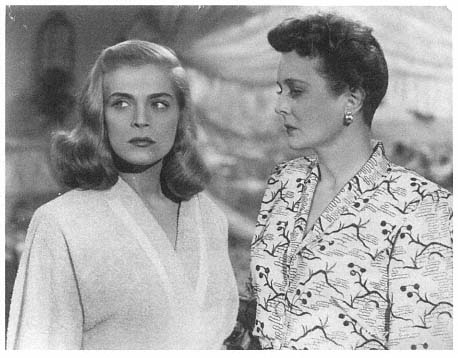

Still, Scott's comminglings with Lancaster aren't much of an improvement. They seem to salute one another like ships passing in a fog—icons of "Male" and "Female" more aware of their individual image power than any conjoined forces that might be negotiated to some other erotic end. Only when placed next to Astor does Scott really convey some sense of the passion the film's title suggests. But as far as Desert Fury 's plot is concerned, the Scott-Astor relationship is simply an engine driving Scott's character toward the resolution Lancaster provides. Dust-dry though it may be, this Scott-Lancaster pairing is the plateau on which Desert Fury is destined to settle.[14]

Desert Fury 's advertising is a lie. But this lie only serves to underscore a deeper truth. For like Poe's (and Lacan's and Derrida's) "Purloined Letter," the "message" of Desert Fury is always in plain sight. Even before the story begins, the discrimination of "desirable" Lancaster over "undesirable" Hodiak has been set in place. The performers' particular qualities (or in this case lack of same) are slipped into the folds of the scenario like a hand in a kidskin glove. The ads aid this effort, suggesting an atmosphere redolent with danger and intrigue—as it is in the film for Scott-Hodiak but not for Scott-Lancaster. Thus the "good" couple is iconographically intermingled with the "bad" one—safety conflating with danger the better to promote the product.

This "ideal" movie couple isn't the only cozily familiar element Desert Fury has to offer. Reassurance also figures in the narrative's echoes of other films. Here's a mother-daughter conflict right out of Mildred Pierce or Possessed .

Desert Fury

The recurring automobile accident recalls The Postman Always Rings Twice . The criminal-out-of-his-element subplot harks back to High Sierra . The color cinematography, particularly in the scene where Scott and Lancaster go riding, recalls Leave Her to Heaven . And that's not all vis-à-vis the color.

"Luscious new colors will be introduced by Lizabeth Scott in her new film Desert Town which Hal Wallis is producing," gushes Paramount News .[15] "Armed with a set of artists' paints, Edith Head, Paramount's chief designer, spent several week-ends in the desert near Sedona, Arizona, where the cast of Desert Town was on location, in order to study some of nature's own colors." The results of her labors were the creation of no less than "16 gowns to be worn by Miss Scott in the film, which is in Technicolor." Thus the oddity of filming a minor potboiler like this one in color is explained—it's more than a melodrama, it's a fashion show.

Not surprisingly, in keeping with this new-found sense of splendor a title like Desert Town simply won't do anymore, and as Paramount News notes,[16]

it's changed to Desert Fury . "Producer Wallis and his associate, Joseph H. Hazen, with Paramount sales and advertising executives, decided upon the new title to underscore the strong dramatic action and emotional conflict in the story of a group of modern characters which is enacted in the colorful setting of today's desert country."

Conspicuous Consumption

Early on in Desert Fury Paula pulls into downtown Chuckawalla and spies two of its more well-heeled female citizens. "Window shopping?" she asks them breezily. "Yes," they reply, looking pointedly at her, "but we don't like what we see. It's too cheap." Cut to Paula looking hurt. She starts up her car and drives off in a huff, nearly knocking the two women down.

The scene establishes a major plot conflict—Paula's estrangement from the town's "upper crust" substrata, an "outsider" status that she alternately resents and enjoys (when Tom in the very next shot says he should have arrested her for her conduct she replies, "It would have been worth it"). Yet at the same time the scene's meaning proceeds from another more obvious level. Like almost everything in Desert Fury , the subject of the scene is shopping .

"Come with me to Los Angeles and we'll buy some new clothes," Fritzie says to Paula, hoping to bring her out of a funk. "But I don't need any new clothes," Paula replies. "A girl always needs new clothes," says Fritzie, offering up a mother's wisdom, consumerist-Hollywood-style. And it's true, for in the world of Desert Fury women always require the new—clothes, adventures, backgrounds, romance. We don't need to go to Los Angeles to go shopping in Desert Fury , the film is already shopping. As Newsweek magazine noted, "Lizabeth Scott, impersonating a petulant daughter, changes costume so frequently that one forgets she is an actress, not a model."[17] Obviously the film makes no distinction between these dual functions. And why should it? The scene in which Paula is sent to her room to be kept away from Eddie alone involves five complete costume changes. One wonders whether this blatant "fashion pitch" was written into the script beforehand or presented itself at some later point in the production—perhaps when it was decided that Edith Head was to play a more important role than usual in Desert Fury 's making.

With Desert Fury we're deep in the heart of that Hollywood where studio "showmanship" declares that audience interest in "the clothes" carries equal—if not greater—weight with "the stars" or "the story." The clothes put so pointedly on display in Desert Fury are just the sort of casual "sport" ensembles an average middle-class woman in the late forties would be likely to wear. They stand in sharp contrast to the glamour duds featured in such films

as The Women (1939), Woman's World (1954), Written on the Wind (1956), or Funny Face (1957). In Desert Fury "practical" purchases predominate. And so it goes with the "purchase" of men.

If all the "classical" cinema has to offer is a "male gaze" forever epoxied to an image of the female seen by definition as "inauthentic," then the audiences for which Desert Fury was expressly designed would have few means at their disposal for getting beyond the film's first scene. There's John Hodiak gazing—like so many movie males—rapturously at Lizabeth Scott as she drives up to the Chuckawalla bridge. But if his gaze is so central, why does the film continue to be in relentless pursuit of Scott irrespective of Hodiak's visual purview? Obviously someone else is looking at Lizabeth Scott—a female spectator whose ability to see with her own two eyes hasn't as yet been accounted for by a theory that would have us all crashing headlong into the Chuckawalla bridge along with Hodiak's wife.

The image of Lizabeth Scott in Desert Fury is quite plainly up on the screen for other women to gaze at. She is a model whose presence bespeaks make-up "secrets," hair-care "tips," a fashion "forecast." The actual relevance of this figure in relation to the lives of women in the postwar era is, naturally, open to question. But it is quite without question that the character of Paula means to address those women and their lives as directly as possible. Desert Fury is a "woman's picture" offering its audience the image of an homme fatal to parallel the femmes fatales of the forties film noirs .

As critic Barbara Deming has noted,[18] the film noir is in many ways something on the order of an allegorical morality play—its heroes' trafficking in criminal activity standing in for killings on the battlefields, its femmes fatales a paranoid evocation of soldiers' fears of returning to "unfaithful" wives and sweethearts. Desert Fury , dealing as it does with the postwar Zeitgeist from "a woman's point of view," highlights these problems with fewer disguises. The war's end brought with it a pool of men for women to choose from. Picking the "good" from the "bad" is Desert Fury 's principal subject. But there is another force at play here as well—equally ideological in nature. For with the return of men came the demand for the return of women to "traditional" roles—removing them from the work force in which they had been placed of necessity during the war.

"You look kinda nice emptying out those ashtrays," Eddie tells Paula, as she adds her "woman's touch" to clear the squalor of Eddie's living arrangements with Johnny. Shortly afterward she's seen sitting at Eddie's feet in front of a roaring fireplace, reading a romance novel. That Paula herself is in a romance novel gives the scene an exceedingly cryptic literary trompe l'oeil quality—as if Alain Robbe-Grillet had momentarily hijacked the scenario. Paula's a party to an object lesson being staged for the viewer's benefit—how to recognize, organize, and direct the process of her desires along accepted social lines.[19]

Of course, it shouldn't be forgotten, Paula has also expressed a wish for a career. But with incredible deftness Desert Fury forecloses this wish by tying it inextricably to Fritzie's insistence on Paula's social betterment. The job at the casino would be a step down—forever barring Paula from the social approval she guiltily craves. Only marriage to Tom would set things aright. "They've accepted you," Fritzie tells him, "and in time they would accept Paula—she'd get her friends." And as with everything else in Desert Fury this process is all a matter of purchasing power—and consumer integrity.

Fritzie wants to "buy" Tom for Paula. His market "value" is clear. Moreover, she'll sweeten the deal. She promises Tom a ranch for his pains. But Tom doesn't want to be an object of exchange, particularly in a woman's eyes. Still he knows where the social cutting edge lies—who are the dealers in this world and who are the dealt. This is why he lets Eddie go in the scene where he picks him up on the highway. Paula ends up "buying" Tom, but on her own terms—after first inspecting the "brand X" of Eddie Bendix.

Still in the midst of this buyer's market there's one bit of damaged goods that stands out in sharp relief against the background of all the others bought and sold across the film's trajectory: Johnny Ryan.

No Love for Johnny

—"Why would there be some of me apart from Eddie?"

—"Two people can't fit into one life."

—"That's what you think."

—"Someday he'll leave you."

—"He'll never leave me."

A standard bit of dialogue for a late-forties melodrama, perfectly suited for a scene in which the heroine fights for "her man," forestalling the troublesome intrusion of "another woman." The only difference is that the "other" in Desert Fury is male.

There's nothing particularly novel about the presence of a homosexual character in a postwar Hollywood film—especially a crime melodrama. Think of The Maltese Falcon (1941) with its Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), Mr. Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), and his "gunsel" Wilbur (Elisha Cook, Jr.). Think too of the pair of inseparable hit men played by Lee Van Cleef and Earl Holliman in The Big Combo (1955). And that's not to mention George Macready in Gilda (1946), John Dall and Farley Granger in Rope (1948), Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train (1951), and many other Hollywood films in which the presence of a homosexual character adds a touch of spice to an otherwise routine scenario. The difference with Desert Fury is the remarkable degree of specificity with which sexual status is detailed.

"I was about your age or older," Eddie tells Paula, recalling how he first met Johnny. "It was in the Automat off Times Square about two o'clock in the morning on a Saturday. I was broke, he had a couple of dollars, we got to talking. He ended up paying for my ham and eggs." "And then?" Paula inquires with expectant fascination. "I went home with him that night," Eddie continues. "I was locked out. I didn't have a place to stay. His old lady ran a boarding house. There were a couple of vacant rooms. We were together from then on."

How touching this subtle integration of the notion of "a couple of vacant rooms"—like the twin beds for married couples required by the Hays Code (in force at the time of Desert Fury 's making). As the immortal Inspector Truscott in Joe Orton's Loot remarks, "Two young men who knew each other very well, spend their nights in separate beds? Asleep? It sounds highly unlikely to me." And so it is, what with Johnny snarling a terse "Getoutahere!" every time Paula so much as glances toward Eddie. Then there's his pathetic pleading to "stay" with Eddie, even after the latter has taken Johnny off his payroll. The relationship couldn't be spelled out more clearly. And it's also clear that this same relationship provides a prime source of attraction to Eddie for Paula.

Curious that such a configuration should find its way into an otherwise mundane scenario. Desert Fury cleanly establishes Eddie's unsuitability for Paula through his organized crime associations, the murder of his wife, and his past affair with Fritzie. Bisexuality, it would seem, would only serve to gild this lily. But as the subject of Desert Fury is proper sexual object-choices and social roles for American women in the postwar era, Eddie's sexual predilictions have an additional plot function. The attraction held by certain heterosexual females for bisexual males was plainly of some significance to that period's social life, otherwise a film like Desert Fury would have been inconceivable. Hollywood, particularly in the studio heyday of the late forties, was never in favor of the advancement of narrative strategies unfamiliar to the masses. Desert Fury may seem novel today, but apparently no one in the front office blinked back in 1947.

In a way Desert Fury was the Making Love of its time. Like Desert Fury, Making Love was designed largely in terms of female spectatorship. The clear speculation in 1982 was that the sight of two men physically intertwined might have the same voyeurist currency as that of the sight of two women. This in turn brings up the fact that lesbianism has always been regarded as well within the purview of the "gaze"—the eyes of men "legitimizing" what would otherwise be an "aberration." The same does not hold for men. The first words a homosexual hears indicative of his newly won pariah status are "What are you looking at?" The "you" emphasized in this rhetorical accusation serves to arrest through the sheer force of its own specification the notion that male voyeurism would even so much as conceive of a male object.

This voyeuristic threat plays no part in Desert Fury . Our views of both Hodiak and Lancaster are quite conventional in that whatever physical attractions

they may possess, their power and legitimacy as men are their true source of sexual fascination. Likewise for Wendell Corey as Johnny. He's simply the lynch-pin of the plot—the key to its mystery. As for his expression of desire, it's ever so carefully interwoven into the film's network of dramatic conflicts. In keeping with the "classical" cinema's tendency to ground desire within a force-field of point-of-view shots for purposes of spectator identification, Desert Fury is especially scrupulous about restricting Johnny's expressions of ardor toward Eddie to two-shots in which the men appear together. The only exception to this rule is the breakfast scene mentioned previously, where Johnny pleads to stay on with Eddie at no salary. The depth of Johnny's feelings are plain for all to see, but in the exchange of looks between Johnny, Eddie, and a silent, pensively smoking Paula, they are prevented from falling within the viewer's sightline. Paula, without speaking, dominates here. It is the regulation of her vision that dictates the mise-en-scène of emotions. Johnny nonetheless leaves his mark on the narrative on another level.

It is Johnny who controls Eddie. He "created" him (as Eddie's climactic confession makes clear) and introduced him to a life of crime. It was Johnny who drove Eddie to kill his wife. "I'm Eddie Bendix!" he declares moments before his death. And even after death Johnny looms across the action—his final speech is repeated on the sound track as Eddie races after Paula in his car, crashing it into the Chuckawalla bridge.

"They never fixed it," Paula says to Tom, referring to the bridge's railings, shattered in the wake of the first accident and gaping open at the moment of the second. She could, of course, be referring just as well to a sociosexual schema that allows the likes of an Eddie or a Johnny. "They will [fix it] one day," says Tom, reassuring her. But forty years later, nothing about Desert Fury , or the culture that spawned it, has been "fixed."

Prisoner of the Desert

Just how far have we come since the fall of 1947? The bulk of Desert Fury 's plot (mother-daughter conflict, woman in thrall to "unsuitable" male) has long served as the stuff of television "soap opera"—both daytime and "prime-time" variety. Fashion "pitches" have their place in this narrative schematic—recently having revived the shoulder pads common to the late forties. Women in these mainstream scenarios are presented as having the "option" of "career" or "family"—though the bias towards domestic "choices" are plain, with attendant "guilt" over "lack of fulfillment as a woman ." "Having it all" is the catch-phrase surrounding this cultural cul-de-sac.

Homosexuality has likewise found its "place" as well. Once confined to the margins of experimental cinema, it's been upgraded to the tributaries of the

Desert Fury

mainstream—"art" and "independent" cinema, and over-the-counter hardcore pornography. Figures like Johnny Ryan no longer "work" here. And why should they? What role is there for a Johnny in an era of Bruce Weber blatancy, or the lip-smacking, towel-snapping sensuality of a Top Gun ?

Johnny Ryan belongs precisely where he is—a late forties programmer called Desert Fury . A compendium of medium-two-shots (with a handful of long shots and close-ups for spice) ceaselessly pursuing one another round a fixed locale. Here are five figures locked inside a scenario so claustrophobic that they need not move more than a few feet before slamming into one another. Here are a series of problems to be dealt with, demands to be answered: Overbearing parents, social stigma and snobbery, dangerous acquaintances, unsuitable swains, a woman not sure about what she wants to do with her life, homosexual desire. Nothing new here. Nothing "old" either. It's the world in which we live, "brought to life" by the Cinema we love. And in our working through it all, it's still possible to isolate the bases of our fascination, our frustration, our boredom, our obsession, ourselves . But ahistorical "close analysis" can't reach it alone, nor can any other theoretical framework that deals with film solely at

the level of narrative logic, or as a vast preamble to a psychoanalytic technique that can function at best only as a metaphor for cinematic interaction.

Metz seems aware of this when he writes that "the problem of the cinema is always reduplicated as a problem of the theory of the cinema and we can only extract knowledge from what we are (what we are as persons, what we are as culture and society)."[20] But who are these persons, this culture, this society?

"Cinematic images," comments Jean-Louis Schefer, "exercise a powerful preemption over the living being, not simply because he is made to feel present at the spectacle, but because he can't see the spectacle unless he's part of it in some way, or unless he himself is the absolute reason for the spectacle, its profoundest passion. That's the real question for cinema. It's never a partial phenomenon based on a split; it's a participatory phenomenon, generalized and indeterminate, working across all the objects of the spectacle. A cinematic projection has to be diffused—across the hero, and the villain, and the animals, and the objects, and the places on the screen—over the whole world. It's with the entirety of that world on screen that the spectator participates or identifies himself, and it's there that he's most sensitive to the effects of spatial dislocation, temporal distortion, and especially emotions."[21]

There is no set theoretical formulation, no royal road to chart this course of cinema. There are only a series of byways and backalleys—some connecting directly to the narrative at hand, others intersecting with advertising, commerce, and current events. Some of these routes connect. Others are cul-de-sacs. But it's only by following them that we can possibly see our way through this detritus, this Technicolor swamp, this two-penny fashion show, this absurd confluence of fixity and drift, this Desert Fury .