Structure of the Heart

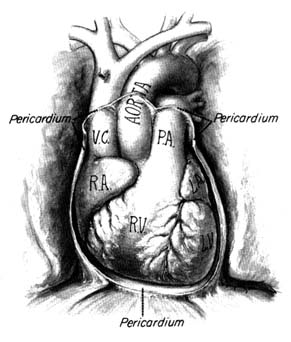

The heart is a muscular, conical organ located in the center of the chest, slightly more to the left than to the right (fig. 2). It has an apex, directed downward and leftward, and a base at its upper part where major vessels originate. The heart consists of three layers: an inner lining (endocardium ); the heart muscle (myocardium ); and the outer covering (pericardium ). The pericardium itself has two layers: the outer lining of the heart (epicardium ), which is firmly attached to it, giving the surface of the heart a smooth, glistening appearance; and a loose sac (parietal pericardium ), in which the heart is suspended. This parietal pericardium is shown in figure 2, where the front portion of it has been removed in order to display details of the frontal aspect of the heart. Between the two layers of

Figure 2. Frontal aspect of the heart with the parietal pericardium

removed. Abbreviations: V.C. = superior vena cava;

R.A. = right atrium; R.V. = right ventricle; P.A. = pulmonary artery.

the pericardium there is a small amount of fluid (pericardial fluid ) which acts as a lubricant, facilitating motion of the heart within the pericardial sac.

The heart is a hollow organ comprising four chambers: two atria (the correct term "atrium" is often used interchangeably with the older term "auricle") and two ventricles . The thin-walled atria act as receptacles for the blood returning to the heart; the thick-walled ventricles, consisting of several layers of muscle, constitute the pump proper. The two atria and the two ventricles are separated from each other by partitions called septa (sing. septum ). As mentioned, the heart is a twin pump: the right side (right atrium and right ventricle) handles venous blood, the left side (left atrium and left ventricle) arterial blood. The independent function of the two sides of the heart is often acknowledged by referring to them as the "right heart" and the "left heart." The respective locations of the

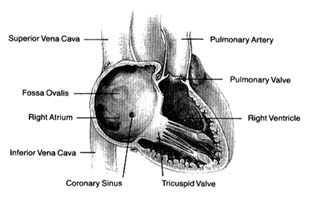

Figure 3. Right side of the heart shown with the front wall removed.

four chambers, as they appear when looking at the front surface of the heart, are shown in figure 2.

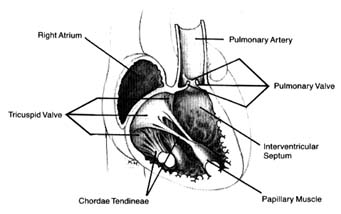

Venous blood enters the right atrium through two large veins and a small vein. The large veins, the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava , channel blood from the upper and lower parts of the body, respectively. The third channel, the coronary sinus , delivers venous blood from the heart itself. The right atrium and its three tributary channels are shown in figure 3. The right atrium is an irregularly shaped chamber connecting, by way of a large opening, with the right ventricle. This orifice is protected by the tricuspid valve . The two large veins enter the atrium at its upper and lower right portions, respectively. The coronary sinus empties into the right atrium at its lower back wall. The mixture of blood derived from the three channels flows into the right ventricle through the tricuspid orifice. The right ventricle is divided into two portions: the lower portion, or inflow tract (behind the tricuspid valve); and the upper portion, or outflow tract, leading to the pulmonary orifice. At the top of the conical outflow tract is the pulmonary artery, separated from the tract by the outflow valve of the right side of the heart—the pulmonary valve (fig. 4). The contents of the right ventricle are ejected into the pulmonary artery, destined for the lungs.

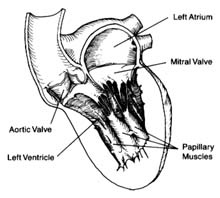

The left side of the heart is almost identical in structure to the right side. The left atrium contains the orifices of four pulmonary veins, two of which drain blood from each lung. This atrium is

Figure 4. Details of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

located on the posterior (back) part of the heart; the pulmonary veins enter on its posterior surface. Its lower part is open, leading into the left ventricle. The connecting opening, the mitral orifice , contains the mitral valve . The left ventricle has a relatively small, conical cavity. The muscle of the left ventricle is three to four times thicker than that of the right ventricle. This relationship is in line with differences in pressure between the two sides of the heart. The upper part of the left ventricle contains both orifices: the inflow (mitral) orifice, to the left and rear, and the outflow (aortic) orifice, in front and to the right. The aorta originates from the left ventricle in a manner similar to that of the pulmonary artery from the right. Its origin contains the aortic valve (fig. 5).

As indicated, the two sides of the heart are separated from each other by partitions, or septa: the atrial septum , and the ventricular septum . The former consists of a thin layer of muscle, with the exception of an oval area where muscle is missing. This feature, the fossa ovalis (fig. 3), is a remnant of a valve, present in the embryo, which protected an orifice between the two atria through which blood could flow from the right atrium into the left atrium before birth (see chap. 11). The ventricular septum consists of a thick muscle continuous with the "free" walls of the left ventricle. It is thinned out in only one small area, underneath the aortic valves, where no muscle is present (membranous septum ). A common

Figure 5. Details of the mitral and aortic valves.

birth defect is for this portion of the septum to be missing, providing a communication between the two ventricles.

The four heart valves consist of two sets almost identical in structure and function. The two inflow valves separate the atria from the ventricles (atrioventricular valves ). The two outflow valves separate the ventricles from the two main arterial trunks (semilunar valves ). The inflow valves prevent blood from backing into the atria during ventricular contraction. The purpose of the semilunar valves is to prevent the sucking back of blood from the aorta and the pulmonary artery during ventricular relaxation.

The atrioventricular valves are attached to rings that form the two orifices between atria and ventricles. These rings are made of dense fibrous tissue (annulus fibrosus ), and the valves themselves are moderately thick, curtainlike structures. The right-sided atrioventricular valve, the tricuspid valve (fig. 4), has three leaflets; the left-sided valve, the mitral valve, has two leaflets (fig. 5). Free edges of each leaflet are connected through a series of delicate strings or cords (chordae tendineae ) with muscular outgrowths, pillarlike structures, in the lower part of the ventricular cavity (papillary muscles ). Each ventricle has two such papillary muscles, connected through the chordae tendineae with free edges of the valve leaflets. These chordae fan out like a parachute to the edge of the valve curtains. The papillary muscle and chordae tendineae stabilize the valves and prevent their flapping back into the atrium when they close in response to the high pressure in the ventricle.

The semilunar valves derive their name from their crescent-shaped leaflets. Each valve consists of three delicate leaflets, forced apart by high pressure during the ejection of blood into the aorta and the pulmonary artery. These leaflets, or cusps, stay close to the wall of the two arterial trunks, permitting free flow of blood. During the beginning of ventricular relaxation the cusps are sucked back with the blood and completely close the orifice separating the vessels from the ventricles during that portion of the heart cycle.