William Grant Still

by Verna Arvey

The following essay on Still, with an introduction by John Tasker Howard, was published as a brochure by J. Fischer and Bro., in 1939, as part of its promotional effort on behalf of Still's music. Its source is very likely an early, incomplete biography whose remnants are at WGSM, very severely cut and edited to fit the publisher's needs. Long out of print, its usefulness in reflecting Still's thoughts about his own compositions and in reporting some recollections about his early career is evident. In particular, its information about the Afro-American Symphony and Darker America should be compared with other discussions of the same works elsewhere in the Sources section of this volume and in "The Afro-American Symphony and Its Scherzo," above.

The sectional subdivisions that are present in the initial publication have been assigned titles. The music examples, taken from works published by Fischer, remain unchanged. Capitalizations, spelling, and punctuation are unchanged except to correct obvious errors.[1] The use of italics and quotation marks for titles is changed to conform with standard current practice.

Introduction

The music of William Grant Still has commanded attention in recent years as one of the truly significant contributions to our native music.

Embodying some of the raciest elements of our current music of the people, as well as a background of the southern Negro, it has been elevated by its composer to a dignity that renders it of lasting value.

It is interesting to read, in the following pages, of the successive steps which led to the ultimate flowering of Still's extraordinary talent. Verna Arvey treats her subject with discernment, and her enthusiasm is infectious because of its sincerity. She has made an important addition to the literature on American music: one which may well have a place in the library of every music lover and student.

It is therefore a pleasure to welcome Miss Arvey's interesting addition to the series of Studies of Contemporary American Composers.

John Tasker Howard

January 2nd, 1939

I—

The Elements That Go to Make Up a Real American

The America of tomorrow will be even more of a mixture of races, of creeds and of ideals than the America of today. Moreover, because they will have progressed so far in each other's company, they will have lost some of their identities. Just such a person is William Grant Still: a product of so many different phases of American life that each separate phase is now unrecognizable. It follows that his music is a more accurate expression of that life than any yet conceived.

Speaking on American music over a national broadcast on October 17, 1937 (when the Columbia Broadcasting System held a resumé of its first American Composers' Commission), Still said: "This music should speak to the hearts of every one of you, for it comes from the hearts of the men who wrote it." He meant that. His own music is sincere; he concludes that the music of other American composers is also sincere. More than that, he meant that every American should be as he is: passionately fond of all things American. Other music is lovely: but an American creation—even a Blues song, if it is a good one—thrills him to the core. He expects all Americans to be like that.

Officially, William Grant Still is reckoned a Negro composer, because the laws of the United States say that anyone with a drop of Negro blood in his veins is a Negro, and because some of his ancestors came from Africa where their rhythmic tom-tom beating may have been a forerun-

ner of the primitive simplicity and powerful rhythmic impulse in Still's music today. Many of his ancestors, however, were already on the North American continent when the Negroes arrived. They were Indians, and it may be from them that Still inherited his bizarre harmonies and his almost oriental love of subtlety. There is still another group of ancestors: the European immigrants (mostly Irish) who danced old-world dances and sang the folk songs that had been theirs for generations. Thus, in Still's heritage we find almost all the elements that go to make up a real American.

Musically, he has all the requisites too. A thorough grounding in harmony and theory (the late George W. Chadwick was one of his teachers; he also studied at Oberlin) combined with the freedom that only ultra-modernism can give (the generous but revolutionary Edgar Varese, who taught him, once wittily remarked "You know, some critics think one is writing music only to annoy them!") as well as the determination and will to strike out for himself into new and individual paths, have made him unique in the field of modern music.

II—

Early Life and Study

Born in 1895 (May 11th) in Woodville, Mississippi, William Grant Still had for parents two people who would be ranked as intellectuals even today, when standards are more exacting. Both were accredited teachers; both were musicians; both were talented, brilliant and versatile. The father's musical education was gained at the cost of great effort. Every cornet lesson he took cost him a seventy-five mile trip. Once he had acquired musical knowledge, he started a brass band—the only one in town—and thus became the idol of Woodville. He died when his son was but three months of age. After his death they found scraps of paper on which he'd tried his hand at musical composition! Had he had then the opportunities accorded his son many years later, he might have become equally famed. But he was the product of a different era; the inhabitant of a different, narrower world; the unwilling participant of an entirely different mode of thought.

His wife took the baby son to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she was to teach school until the end of her life, in 1927. It wasn't strange that, as soon as the child realized what music was, his thoughts turned toward it so unerringly that no scoldings, no arguments nor pleadings could shake his desire to be a composer, although on several occasions he in-

dulged in the popular pastime of most young boys, the idea that the most thrilling thing in life was to be a street car conductor, or to raise chickens for a living.

Often, when the boy wished to amuse himself, he made toy violins to play upon. They were varnished and equipped with strings. They even succeeded in producing tones! Later, it was decided that he must have violin lessons. No sooner did he learn to read notes than he wanted to write them. Lacking manuscript paper, he made his own. Immediately, he jotted down little melodies, and even took his new enthusiasm to school. When other students were scratching aimlessly on paper in their spare moments, he scribbled notes.

While his grandmother worked about their house, she sang hymns and spirituals. "Little David, Play on Yo' Harp" was one of her favorites. Thus he grew up with the songs of his people, and grew to love the old hymns, which he plays today with the addition of such exquisite harmonies that they assume unsuspected beauty. A communal habit of the childhood days was that of serenading. It was pleasant to be awakened from slumber by such sweet sounds. He has always deplored the passing of that custom.

He learned to sing, and did not confine his singing to the immediate family. The aisles of trains made a splendid setting for his youthful vocal efforts. He quickly noticed that people gave him money and candy in return, so thenceforth he sang to everybody.

When young Still was about nine or ten years of age, his mother married Charles B. Shepperson, a postal employee who was a lover of operatic music and who spent a large share of his salary to buy a phonograph and the best of the red-seal records that were then on the market. This gave the boy an opportunity to hear music that pleased him more than any he had ever heard before: music that he had thought existed only in his wildest dreams. He used to play each record over and over again, to the utter neglect of whatever work there was to do. Mr. Shepperson also took him to good musical shows and told him stirring stories that fired his romantic imagination. At home, they sang duets together and discussed the plays they had seen and the music they had heard.

His mother's determination, good sense, talent and high moral character influenced his life strongly. She was the sort of vital personality who could command attention merely by entering a room. Her students adored her, and learned more from her than from anyone else; so did her young son, for he too was in her classes at school. Here she was

stricter with him than with anyone else, for she did not want to be accused of favoritism.

William Grant Still was graduated from high school at sixteen. He was first honor bearer and class valedictorian.

Although she was at heart in sympathy with his desire to become a composer, his mother openly avowed her disapproval, simply because she felt that there was then no future for a musician, especially for a colored one. Thus, when he enrolled at Wilberforce University, he worked for a Bachelor of Science degree. Wilberforce statistics today show that he maintained a slightly above average scholastic record.

The mere fact that his mother had insisted that he work for a Bachelor of Science degree did not dampen Still's musical ardor in the least. Wilberforce had a string quartet, which occasioned the first arrangements he ever made. From that, he went on to making arrangements for the Wilberforce band of which he was first a member, then a bandleader. These arrangements were perhaps not perfect, but they had fewer defects than one would expect from a beginner. He made these because he didn't like the instrumental ensembles he heard. Therefore, he automatically set about to remedy their faults, just as the dancer La Argentina once set out to make a beautiful instrument from the castanets she so abhorred.

Every month before his allowance came, the music books he wanted were checked off and as a result, music publishers and dealers practically confiscated all his spending money. When he started to buy opera scores, his first acquisition was Weber's Oberon . The second was Wagner's Flying Dutchman . His French class was enlivened and made more interesting for him when he took into it a music book containing stories of all the famous Symphonies and read it while class was progressing. The teacher never discovered the substitution.

Some of the teachers went with him to operas and concerts in Dayton, Ohio. Other teachers encouraged his efforts at composition, and it was at Wilberforce that his first complete recital of his own compositions (some songs, some band numbers) was given. The approbation accorded him meant much at that time.

In addition to his playing of the violin, he learned how to play the oboe and clarinet. The latter he played in the choir and thus learned to transpose easily, for then no separate parts were written out. Everyone had to read from the same sheet. In his capacity as bandleader, he had to learn to play different instruments such as the piccolo and saxophone

so that he could teach them to other players. The intimate knowledge of all instruments gained in this fashion has meant much to him in later years, and to his career as an orchestrator.

At Wilberforce, Still decided that he wished to emulate Coleridge-Taylor in every way, and spent many months in a fruitless attempt to make his hair grow straight upward, as did that of his hero. That failing, he made a new and important decision: some day he would be greater than Coleridge-Taylor and wear his hair in his own way!

On his summer vacations at home, Still entered several national contests for composers. To avoid his mother's scorn, he used to compose his entries at night, and would beg those who discovered him not to tell his mother. He entered a contest for a three-act opera (and ambitiously mailed out a score totaling twenty pages in length!) and another contest in which the judges wrote to tell him that his music had merit, but that they were afraid they didn't completely understand it!

Within two months of graduation, Still left Wilberforce. However, in 1936, Wilberforce awarded him a diploma of honor and the honorary degree of Master of Music, in recognition of his erudition, usefulness and eminent character.

Lean years followed the Wilberforce days, years in which he married, worked at odd jobs for little money, played oboe and 'cello with various orchestras, starved, froze, joined the U.S. Navy and nearly always wondered how he could crash the business of making music and getting paid for it. It was during those years also that he received a legacy from his father and promptly put it to good use studying privately at Oberlin. When it was exhausted, he worked and made enough money to return for the regular session. He completed one semester's work in theory and violin. Professor Lehmann, impressed by his talent and sincerity, asked him then why he did not go on to study composition. Still replied frankly that it was because he had no money. A few days later, Lehmann informed him that in a meeting of the Theory Committee it had been decided that he was to be given free tuition, and that Dr. George W. Andrews was to teach him composition.[2] Thus a scholarship was created for him where none had existed before.

III—

Work with Handy; New York

W. C. Handy, Father of the Blues, offered him his first job in New York City as an arranger, and as a musician on the road, traveling through

large and small Southern towns with Handy's Band. Later he accepted a job with Eubie Blake's orchestra for the epoch-making Shuffle Along . While Shuffle Along was playing in Boston, Still became aware that he now could afford to pay for musical instruction, and filed his application at the New England Conservatory of Music. When he returned for his answer, he was told that George W. Chadwick would teach him free of charge. He protested that he could afford to pay, but generous Chadwick refused to take his money.

Back in New York, Still accepted the position of Recording Director for the Black Swan Phonograph Company. There he found a man preparing to write to Edgar Varese to tell him that, in response for his request for a talented young Negro composer to whom he could offer a scholarship in musical composition, he knew of no one suitable. Still said, "I want that scholarship. You can just tear up that letter!" Thus came about his introduction to Edgar Varese, and modernism. Later, Still often declared, "When I was groping blindly in my efforts to compose, it was Varese who pointed out to me the way to individual expression and who gave me the opportunity to hear my music played. I shall never forget his kindness, nor that of George W. Chadwick and the instructors at Oberlin."

For many months, he played in vaudeville and in the pit for many musical shows. He played banjo in the orchestra of the Plantation, a New York night club at Broadway and 50th. When the conductor of this orchestra left, Still advanced to its conductorship.[3] He went into business as an arranger, and made arrangements for such people as Sophie Tucker, Don Voorhees. He orchestrated several editions of Earl Carroll's Vanities, one edition of J. P. McEvoy's Americana, and Runnin' Wild and Rain or Shine . Later he arranged for Paul Whiteman, who was to play some of his compositions for the first time in public and to commission several notable works from him.

He was the first to arrange and record (with Don Voorhees) a fantasy on the famous "St. Louis Blues." This was in 1927, on a Columbia disc.

The last orchestra with which he ever played professionally was that of LeRoy Smith. So much work as arranger and orchestrator came his way that he was no longer in need of such work to make a living.

When CBS first started, Still was arranging Don Voorhees' music for the network broadcasts. Somewhat later, he was arranging at NBC when Willard Robison was singing on the Maxwell House Hour. Soon Still was making arrangements for Robison's "Deep River" program

and (at WOR) some of the orchestra men quietly suggested to Robison that Still be allowed to conduct their organization. The management agreed, as long as the men were satisfied. In that way, he became the first American colored man to lead a radio orchestra of white men in New York City, and he held the post for many months.

In this way he became intimately acquainted with Jazz, the American musical idiom that has been damned by so many, and praised by so many more. He, too, realizes that Jazz has many faults, but he also realizes that it has many fine points, and he believes that from its elements a great musical form can be built. Today he points out the many things Jazz has given to music as a whole: rhythm, new tone colors, interesting orchestral devices, and a greater fluency in playing almost all of the orchestral instruments. He mentions the amazing things a modern player can do—things that would have caught an old-time symphony man napping. He believes that every composer, to deserve the name of "American", should be thoroughly acquainted with Jazz, no matter whether he uses it much or little in his work. It is one of the few musical idioms developed by America that can be said to belong to no other people on earth!

IV—

Some Popular Songs and Early Concert Music

Still's first published composition is lost today, even the title forgotten. It was published by one of those fly-by-night concerns that will print anything for a monetary consideration. The second published work was a bit more fortunate. It was a popular song called "No Matter What You Do". His wife was the lyricist; W. C. Handy the publisher. Two popular songs by Still were published by the Edward B. Marks Music Corporation under the pseudonym of Willy M. Grant. Their titles were "Brown Baby" and "Memphis Man."

Several of his pieces were played many times on the air and found great favor with the musicians because they were catchy and were saddled with dubious titles. The composer laments today that he has lost the music for these, but is happy over the fact that they were never published and distributed over a wider area.

Three Fantastic Dances for chamber orchestra he never finished; his Death, a choral work for mixed voices a cappella on a Dunbar poem was completed and deliberately thrown away. He also wrote Three Ne -

gro Songs for orchestra (i.e. "Negro Love Song," "Death Song," "Song of the Backwoods") as well as an orchestral composition called Black Bottom which he described as follows: "A swamp where, between the hours of four A.M . and six A.M ., Death and the fiends of darkness revel. Death, disguised as a siren, dances and sings a song which is repeated by the fiends. All join in the revelry which is interrupted at its height by a distant clock striking the hour of six." This work is cast in a decidedly ultra-modern idiom.

There were also several songs. One entitled "Good Night," to words of Dunbar, was dedicated to William Service Bell, baritone. "Mandy Lou" belonged to but did not appear with the set of two songs later published by G. Schirmer, Inc. At last, all these early efforts and smaller compositions were scrapped. Whatever was good in them was incorporated into a larger work. For instance, the "Dance of Love" (played over the radio many times) was put into The Sorcerer ballet which has itself been scrapped and its themes used in other compositions, and the "Dance of the Carnal Flowers" was inserted, with few changes, into the ballet La Guiablesse .

From the Land of Dreams was his first major work to be subjected to critical comment when it was performed by the Composers' Guild in New York February 8, 1925. It was scored for three voices and chamber orchestra, the voices treated as instruments. It occasioned a storm of protest. In it, the composer simply tried to suggest the flimsiness of dreams which fade before they have taken definite form, but Olin Downes wrote sharply: "Is Mr. Still unaware that the cheapest melody in the revues he has orchestrated has more reality and inspiration in it than the curious noises he has manufactured? Mr. Varese has driven his original and entertaining music out of him." On the other hand, Paul Rosenfeld, while admitting Still's limitations at this period of his life and work, spoke more kindly of this composition.

The score of From the Land of Dreams is now lost, much to the composer's delight. He fervently hopes it will never again be played, and now jokingly refers to it as a musical portrait of an owl with a headache. It was, indeed, ultra-modern in style: pure cacophony throughout.[4] It was not until the moment of performance that Still realized that he was dabbling in an idiom unsuited to him, one that robbed his music of its character, for a harmonic scheme can make or mar the feeling of the music. He thereupon determined to find an idiom of his own, and made known his decision to M. Varese.

Should Varese have felt badly over this decision so flatly announced, it doubtless comforts him today to realize that the fruits of his teaching are evident in Still's music in far more subtle, more logical ways than if the young composer had merely adopted Varese's own individual idiom without question.

Today, from the lesson he learned in his attempts at cacophony, Still will occasionally emit remarks like these: "When a person sets out to write music on the basis of a preconceived scientific idea, something invariably goes wrong. If the counterpoint is smooth, the melody will be imperfect, and so on. The result may be correct, but be entirely lacking in spiritual content. In music, one must think more of what is to be said than how it is to be said."

From the Journal of a Wanderer (written in 1925, performed by the North Shore Festival Orchestra in Evanston, Ill., with Frederick Stock conducting in 1926 and by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1929) is important in this period as a lesson in "what not to do," according to its composer, in spite of the fact that at the time of its performance, it seemed to be a decided step in advance of Darker America (to be discussed later). In a sense, it was more versatilely written, more spectacularly conceived. On this point, critics agreed, though one of them did admit that it savored of stunt writing. The reason Still was personally disappointed in it was simply that the result of his planning (in performance) was quite different than what he expected. Into the score he had written a great many clever orchestral effects. He had gone the limit in the division of his string. It all looked very well on paper. His surprise at the difference in sound can well be imagined. From the Journal of a Wanderer comprised extracts from the musical diary of a globe trotter who had visited far lands and viewed strange scenes. It was in five parts: "Phantom Trail," "Magic Bells," "The Valley of Echoes," "Mystic Moon," "Devil's Hollow." The original manuscript of this score is now in the Sibley Musical Library at the University of Rochester, gift of the composer.

Two comparatively unimportant works may be mentioned here, out of their chronological order: Log Cabin Ballads, consisting of three parts, "Long To'ds Night," "Beneaf de Willers," "Miss Malindy" (written in 1927 and performed by the Barrère Ensemble in New York on March 25, 1928); and Puritan Epic (written in 1928). Both of these are orchestral works.

At the time of their creation or performance (1928), Still was receiv-

ing the second Harmon Award, granted annually by the Harmon Foundation, for the most significant contribution during the year to Negro culture in the United States.

V—

"Negroid" Compositions to 1930

After much thought, Still decided to adopt a Negroid idiom; to use Negroid titles for his compositions. Since that decision, his departures from his original resolve have been rare.

Levee Land was written for the singer, Florence Mills. It consisted of four robust, jazzy, Negroid songs. Critics joyfully lauded his farewell from the peculiar noises comprising Varese's musical idiom when it was performed by the International Composers' Guild at Aeolian Hall on January 24, 1926. The Musical Courier called it "Four foolish jazz jokes: good, healthy, sane music." And the incomparable Florence Mills, veteran of many stage and floor shows, was unreasoningly nervous at this, her first concert venture. She sang beautifully, however. Her vibrant personality was a vital part of the songs. Yet Levee Land was not even perfect of its kind. It simply marked a step toward the goal the composer wished to reach. With the exception of the spontaneous first song, there were many things in Levee Land that were creations of the brain, not of the heart.

At the time it was written (1924) Darker America was his strongest work. The program for it was compiled after the creation of the music. It received an enthusiastic reception on its performances (by the International Composers' Guild at Aeolian Hall in New York on November 28, 1926, by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1927 and in 1930, and for broadcasting by John Tasker Howard in New York in 1933), and was later published by the Eastman School of Music through C. C. Birchard Co., in Boston. The Musical Courier averred that he was less under the influence of Varese than he was a year before, and that the less that influence was felt, the better for his music. It prophesied that on his full liberation, he would blossom forth as one of America's truly great composers. "There is no doubting the man's power!" Another metropolitan periodical remarked that, despite Varese, Mr. Still had been "unable to suppress that rhythmic ingenuity and naive melodic atmosphere which are inherently of the American Negro." But how fortunate for Still that he had the assistance of a man like Varese! Without that, he might still be groping among unexciting, academic methods of

writing music. He might never have had the courage to strike out for himself!

Nevertheless, Still himself does not consider Darker America a good example of his work. It is, he declares, fragmentary. It contains too much material. At the time it was written, he was struggling with musical form. His conception of it was rather hazy. He had not yet learned how to do a great deal with a few themes. He was obsessed with the beginner's idea of using a great deal of material, whether or not it was related.

Darker America was intended to suggest the triumph of a people over their sorrows through fervent prayer. At the outset, the strong theme of the American Negro is announced by the strings in unison. Following a short development of this, the English Horn announces the Sorrow theme which is followed by the theme of Hope, given to muted brass, accompanied by strings and woodwinds. The Sorrow and Hope themes appear intensified, and the prayer is heard, stated by the oboe. Strongly contrasted moods follow. At the end, the three principal themes are combined in triumphant music.

After the performance it was evident that Still's advance as a composer had been tremendous, for the ugly discords were conspicuously absent and the thematic material of Darker America was rich, potent, and served to characterize him as a composer of definite individuality and power.

About 1926, when From the Black Belt was written, Still conceived an idea which has ever since been evident in his works. He began to base each composition on a different harmonic scheme: a scheme that would be an essential part of his own musical individuality, but which would differentiate each composition from the other. He began also to try to express moods, story, even thoughts by means of harmonies.

The same vigorous sense of humor that led the youth to play pranks on other people in College is shown in many of his compositions, especially in From the Black Belt (easily the most racial of all) written for small orchestra, and composed admittedly to please those who hear it. The first section "Lil' Scamp" lasts for eight measures only. It was expected to provoke laughter and it always does, whenever it is performed. Says the composer: "If one were to base his judgment on the volume of sound he would think this little fellow, who delights in playing childish pranks, a big scamp. But the aptness of the title is not determined by volume for it is the brevity of the piece which tells us that he is a 'little scamp.' " The other sections are entitled: "Honeysuckle" (a musical sug-

gestion of the saccharine odor of the honeysuckle), "Dance, Mah Bones Is Creakin' " (An old man, afflicted with rheumatism, complains loudly of his creaking bones), "Blue" (a plaintive melody which suggests the "blues" songs of the southern Negro), "Brown Girl" (a tone picture of a lovely mulatto girl), "Clap Yo' Han's" (the participants in a dancing game for children clap their hands). It was performed by the Barrère Ensemble in New York on March 20, 1927 and by the Eastman School Little Symphony in Rochester in 1933 and 1934. On one of the latter occasions, a Rochester critic wrote: "This genial, soft-spoken Negro has proved himself a leader in the movement to write music that is not merely cerebral, that has no fear of melody, that begins with the definite intention of pleasing his hearers. His suite was of seven short movements, but their ingratiating tunes and rhythms had the audience asking for a repetition, and that at the end of a long concert." This was later arranged by the modernist, Nicholas Slonimsky, for clarinet, violin, 'cello and piano.

Two works of beauty which emerged from this particular period were the songs "Winter's Approach" to words by Paul Laurence Dunbar, and "Breath of a Rose" to a poem by Langston Hughes. The former was written for Marya Freund, the latter for a stage production in which Paul Robeson was to have been featured, though the song was not intended for Robeson to sing. In these two simple songs (published by G. Schirmer, Inc.) Still's scope as a composer and his distinction are evident. Both are unmistakably his own, yet are entirely different in character, their ultimate form having been dictated by the subject. They show the sharp individuality of the music, the lack of monotony, and give evidence that, though he is decidedly a modernist, he is not an ultra-modernist. His writing for the voice is sympathetic, vocally grateful and facile. Throughout both songs, the piano accompaniment plays an important part, for it expresses mood and meaning.

VI—

The Trilogy: Africa, the Afro-American Symphony, and Symphony in G Minor

Africa, the Afro-American Symphony and the Symphony in G Minor comprise a trilogy of works whose composition occupied their creator over a period of years, during which time other works were also written and played.

Perhaps most intellectual young American Negroes think much about their African background. William Grant Still's meditations on this sub-

ject took a musical form. It was in 1930 that he wrote Africa, a symphonic poem in three movements, designed as an American Negro's wholly fanciful concept of the cradle of his Race, formed on the folklore of generations. Because the movements have descriptive titles, one might call Africa a suite, but the composer prefers to describe it as a poem, believing that the unity of the idea justifies it.

Africa, which critics said was "not as inchoate or as desultory as his Darker America and Journal of a Wanderer, " quickly became one of his most highly praised compositions. During five years, four different versions of Africa were scored, three of which were performed. In January of 1933 appeared the fifth and supposedly last version. But in 1935 Still noted a flaw, and a sixth version came into being. This constant revision is not unusual with him. Many things he destroyed completely because, in his own judgment, they "weren't good enough." He constantly criticizes his own work and constantly revises. This results in much extra labor, but he feels that final perfection justifies it.

The three movements of Africa are titled: "Land of Peace," "Land of Romance," "Land of Superstition."[5] In the first movement, two kinds of peace are portrayed, the first pastoral, the second spiritual. It is an active peace and quietude, not a lethargic slumber. "Land of Romance" is tinged with sadness, intensified by the orchestral treatment of the first part of the movement. It ends on a note of passionate longing. In the final movement, two forms of superstition appear: that of the pagan African and that of the followers of Mohammed. The music abounds in the suggestion of startling unspoken fears, lurking terrors. It subtly conveys the idea that the race has not yet shaken off primitive beliefs, despite the influence of civilization. The opening theme later proceeds into a rather Oriental motif, by which the composer intended to depict the arid Northern part of Africa. Africa places the listener instantly on the soil of the Dark Continent; it is not merely a picture of abstract beauty.

Africa was dedicated to the eminent flautist, Georges Barrère, and was performed by the Barrère ensemble in New York in 1930, by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Rochester in 1930, at the Festival of American Music in Bad Homburg in 1931, in Paris by the Pasdeloup Orchestra in 1933, in Rome under the leadership of Werner Janssen, and in part by Paul Whiteman's Orchestra in New York in 1933, by the New York Sinfonietta in 1933, and under the composer's direction by the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra in 1936.

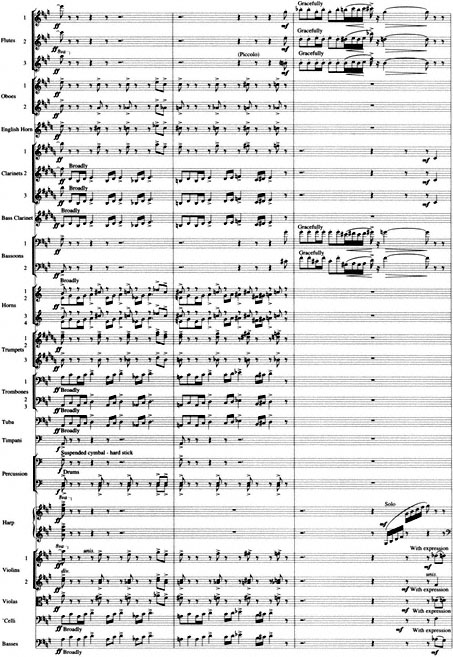

The second composition in the trilogy, the Afro-American Symphony, was composed in 1930, dedicated to Irving Schwerké and performed by

the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Rochester in 1931 and 1932 and in part under the direction of Dr. Howard Hanson (who introduced it) in Berlin, Stuttgart and Leipzig in 1933. These dates show conclusively that Still's work preceded that of another Negro composer who in 1934 was heralded as having written the first Negro symphony.

This Afro-American Symphony really became widely known through the energy of its publishers who were canny enough not to allow important publications to gather dust on their shelves. From the date the symphony was accepted for publication, and since its performance under Hans Lange and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, this symphony has had many performances. Leopold Stokowski played its last movement in many American cities on his nationwide tour with the Philadelphia Orchestra, thus bringing it to the attention of many American music-lovers.

A reviewer said, "There is not a cheap or banal passage in the entire composition." A Rochester critic opined that it was "by far the most direct in appeal to a general audience than any of his music heard here, and it has a greater technical finish. To some extent he has replaced that arresting vigor one has admired by deft sophistication." Another Rochester critic dubbed it "honest, sincere music . . . developed without recourse to theatrical invention." David Kessler said it "seemed a much more important work on second hearing than it did the first time it was played"—genuine praise, indeed. An audience in Berlin broke a twenty-year tradition to encore the Scherzo from this Symphony when Dr. Howard Hanson conducted it there; several years later, when Karl Krueger conducted it in Budapest, his audience did the same thing.

Of this symphony, Still wrote:

At the time it was written, no thought was given to a program for the Afro-American Symphony, the program being added after the completion of the work. I have regretted this step because in this particular instance a program is decidedly inadequate. The program devised at that time stated that the music portrayed the "sons of the soil," that is that it offered a composite musical portrait of those Afro-Americans who have not responded completely to the cultural influences of today. It is true that an interpretation of that sort may be read into the music. Nevertheless, one who hears it is quite sure to discover other meanings which are probably broader in their scope. He may find that the piece portrays four distinct types of Afro-Americans whose sole relationship is the physical one of dark skins. On the other hand, he may find that the music offers the sorrows and joys, the struggles and achievements of an individual Afro-American. Also it is quite probable that the music will

Example 8.

Principal theme, first movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

speak to him of moods peculiar to colored Americans. Unquestionably, various other interpretations may be read into the music.

Each movement of this Symphony presents a definite emotion, excerpts from poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar being included in the score for the purpose of explaining these emotions. Each movement has a suggestive title: the first is Longing, the second Sorrow, the third (or the Scherzo) Humor, and the fourth Sincerity. In it, I have stressed an original motif in the blues idiom, employed as the principal theme of the first movement, and appearing in various forms in the succeeding movements, where I have tried to present it in a characteristic manner.

When judged by the laws of musical form the Symphony is somewhat irregular. This irregularity is in my estimation justified since it has no ill effect on the proportional balance of the composition. Moreover, when one considers that an architect is free to design new forms of buildings, and bears in mind the freedom permitted creators in other fields of art, he can hardly deny a composer the privilege of altering established forms as long as the sense of proportion is justified.

The Moderato Assai, the first movement, departs to an extent from the Sonata Allegro form. The first division might be called the Exposition. This begins with an introduction in A flat Major, derived from the principal theme, and is followed by the principal theme (example 8). Following this, the principal theme reappears in a new treatment, and with a rhythmic counterpoint, which is extended to form a bridge between the repetition of the principal theme and a transition that strongly resembles a development of the principal theme. The subordinate theme is in G Major (the fact that the keys are here unrelated is a departure) and is in the style of a Spiritual (example 9). Then, instead of a Codetta, there is a transitional passage, starting in G Minor and leading to the Development in Division Two, in A Flat Major, the material here derived from the principal theme. Division Three is a Recapitulation,

Example 9.

Subordinate theme, first movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 10.

Principal theme, second movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 11.

Secondary theme, second movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

in which there is a radical departure. The subordinate theme reappears in A Flat Major, instead of a repetition of the principal theme. There is a re-transition before the final appearance of the principal theme in A Flat Major in a new and rhythmic treatment. The movement ends with a coda.

The second movement is short. There is a six measure introduction, scored entirely for strings and muffled tympani. The material of this introduction is derived from the principal (blues) theme of the first movement. The principal theme of the second movement, however, is played by oboe alone, accompanied by violas and 'celli divisi and by a flute obligato. It is eight measures in length (example 10). This theme is repeated, then extended slightly. The gap between the principal theme of the second movement and its subordinate theme is bridged by four measures of material taken from the introduction to the second movement, and used in transitional fashion. The subordinate theme is given to the flute at the outset, and is derived from the principal theme of the first movement (example 11). Thereafter, appear four-measure blocks of this same melody treated in different ways, a development of an individual sort. This lasts for thirty measures and leads to a repetition of the movement's principal theme, extended and working up to a fermata, and a pause. The movement ends with the introductory material given to muted strings and muffled tympani, here extended to eight measures.

Example 12.

Principal theme, third movement (Scherzo), Afro-American

Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 13.

Transformation of the symphony's main theme, Coda

of third movement.

Used by permission.

Example 14.

Principal theme, fourth movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

The form of the third movement, or Scherzo (the humorous aspect of religious fervor) is also unusual. The Introduction, in E Flat Minor, is derived from the principal theme, yet resembles in a general way the episodic material. The principal theme is in A Flat Major (example 12). Just before the Coda there appears a transformation of the blues theme of the first movement, as an accompanying figure (example 13).

The fourth movement, Lento con Risoluzione, has a decidedly free form. The principal theme is announced at the outset by strings accompanied by clarinets, trombones and tuba (example 14). The subordinate theme in A Major is derived from the blues theme (example 15). This theme is presented again in C Major and is then developed, the development being extended and presenting, during its course, the blues theme in a different form. Much later in the score, there is a new development in 6/8 time which enters abruptly. In

Example 15.

Subordinate theme, fourth movement, Afro-American

Symphony .

Used by permission.

this, the blues theme reappears in still another form. Just before the coda brings the movement to its close, the principal theme of the movement is re-stated.

The harmonies employed in the Symphony are quite conventional except in a few places. The use of this style of harmonization was necessary in order to attain simplicity and to intensify in the music those qualities which enable the hearers to recognize it as Negro music. The orchestration was planned with a view to the attainment of effective simplicity.[6]

Third in the trilogy is the Symphony in G Minor which, at the earnest request of Dr. Leopold Stokowski, who introduced it with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Philadelphia in December of 1937 and then played it twice in New York City a few days later, was subtitled Song of a New Race . This music, too, was composed as abstract music, with no thought of a program. Its creation occupied the composer for more than a year. Measure by measure, phrase by phrase, the work grew slowly, until it became one of the finest of his symphonic works to date. The theme of the second movement alone is masterly in its inspiration (example 16).

Of this Symphony (dedicated to Isabel Morse Jones), the composer has written the following:

This Symphony in G Minor is related to my Afro-American Symphony being, in fact, a sort of extension or evolution of the latter. This relationship is implied musically through the affinity of the principal theme of the first movement of the Symphony in G Minor to the principal theme of the fourth, or last, movement of the Afro-American .

It may be said that the purpose of the Symphony in G Minor is to point musically to changes wrought in a people through the progressive and transmuting spirit of America. I prefer to think of it as an abstract piece of music, but, for the benefit of those who like interpretations of their music, I have written the following notes:

The Afro-American Symphony represented the Negro of days not far removed from the Civil War. The Symphony in G Minor represents the

Example 16.

Symphony in G Minor (No. 2), "Song of a New Race," second

movement, opening.

Used by permission.

American colored man of today, in so many instances a totally new individual produced through the fusion of White, Indian and Negro bloods.

The four movements in the Afro-American Symphony were subtitled "Longing," "Sorrow," "Humor" (expressed through religious fervor) and "Sincerity," or "Aspiration." In the Symphony in G Minor, longing has progressed beyond a passive state and has been converted into active effort; sorrow has given way to a more philosophic attitude in which the individual has ceased pitying himself, knowing that he can advance only through a desire for spiritual growth and by nobility of purpose; religious fervor and the rough humor of the folk have been replaced by a more mundane form of emotional release that is more closely allied to that of other peoples; and aspiration is now tempered with the desire to give to humanity the best that their African Heritage has given them.

Linton Martin, writing in the Philadelphia Inquirer for December 11, 1937, said "Song of a New Race by the Negro composer, William Grant Still, was of absorbing interest, unmistakably racial in thematic material and rhythms, and triumphantly articulate in expression of moods, ranging from the exuberance of jazz to brooding wistfulness." A few days later, Olin Downes wrote: "It is interesting to perceive how far Mr. Still can go in a purely melodic manner, without resort to many of the traditional symphonic devices to fill out his tonal design." Leopold Stokowski, however, wrote to the composer that the new work was a

Example 17.

Symphony in G Minor , page from the composer's score.

Used by permission.

tremendous advance over the former symphony, beautiful and vital though that was.

VII—

Ballet Music

Choreographic music has always held a fascination for William Grant Still, and dancers have not failed to take advantage of his willingness to write for them, and to perform his works accordingly. La Guiablesse was begun before Sahdji, but was completed later. Both of these are ballets, with a woman dancer as the central character.

La Guiablesse (a patois word meaning female devil) is based on a scenario by Ruth Page which in turn was based on a legend of Martinique. It was produced in 1933 at the Eastman School in Rochester, also in Chicago; later it was produced thrice in a single season (1934) by the Chicago Grand Opera Company. In later years, Rochester also revived it several times.

This ballet music is not at all superficial, as is most created dance music. Before writing it, Still studied West Indian and Creole musical material, but finally determined to create his own themes as being truer to scene and mood. The scene is laid on the Island of Martinique. The opening theme is that of La Guiablesse. This appears throughout the score, and finally in the funeral march at the end. The she-devil herself is introduced by an offstage contralto solo, a haunting, wordless melody. Sensuous beauty and dramatic intensity mark the music. It progresses from a fairly quiet and atmospheric beginning to a thrilling climax. The story concerns two young lovers, Adou and Yzore, whose tender love is interrupted by the appearance of the greedily sensuous she-devil. She lures Adou away from his village sweetheart. Then, just as he is past returning, the music assumes a horrible tinge as the beautiful woman turns into a demon, and like demoniac laughter it continues as she insists on claiming her prey. Adou, unconscious, falls from her embrace into the pit below.

Herman Devries, writing in the Chicago American, said of it: "It is far above the average ballet music . . . both in quality of invention and in the value of its themes and imagination. It is a highly-colored, vivid, evocative, gorgeous score." Stuart R. Sabin in Rochester wrote: "The music is charming, picturesque and dramatically suggestive, never padded, never divorced from the action, yet with an individual appeal of its own."

The ballet Sahdji, dedicated to Dr. Howard Hanson, is significant for two reasons: it is more important musically than choreographically; it marked the turning point in the regard of critics such as Olin Downes. Downes came to Rochester for the performance (it was done in Rochester in 1931 and in 1934) and wrote at length about it. Other ballets were on the same program, but Downes concentrated his remarks on Sahdji . He commented on the unusual form in which the work was cast, said "Still harks back to more primitive sources (i.e. than Harlem jazz) for brutal, persistent and barbaric rhythms," and acknowledged him as one of America's finest, most promising composers.

Sahdji is elemental: fine music, significant drama. It is a ballet for chorus (singing a text connoting incidents in the action) and bass chanter, interpreting the ballet by reciting African proverbs. A psychological effect is produced by drums. The story is told in pantomime and is built around the faithless favorite wife of the African chieftain Konumbju. The scene is laid in ancestral, central Africa. It is a hunting feast of the Azande tribe. Librettists were Richard Bruce and Alain Locke.

William Grant Still spent about a year and a half preparing to write Sahdji, absorbing African atmosphere so as to be able to write in that idiom without resorting to authentic folk material. The so-called "Invitation Dance," when Sahdji lures Mrabo into the hut, came to him first and around it he built the rest of the ballet. Once begun, his eagerness to complete it knew no bounds. In its form, the old Greek dramatic model is approximated.

In 1936 Sahdji was revised, several minor changes being made, and a prologue to be sung by the Chanter was added. The ballet has never yet been performed in its revised version.

VIII—

Works from the Guggenheim Period and for Paul Whiteman

Both Ebon Chronicle and A Deserted Plantation were commissioned by Paul Whiteman and were scored for Whiteman's instrumental combination, so that when the former was played by Whiteman with a large symphony orchestra it was termed "dull and pretentious" by a critic. With this statement, the composer disagreed slightly, for he had never written it with the idea that it was a major work of art, nor did it pretend to a distinction that was not intended for it. A Deserted Plantation, excerpts from which were later arranged for piano and published by Robbins

Music Corporation, was once recommended to diversion seekers by Walter Winchell. Its prologue is played separately, and the succeeding four movements continue without a break, being linked by interludes for solo piano. It is a musical picture of the meditations of Uncle Josh, an old colored man who is the sole occupant of the dying plantation and who delights in dreaming of its past glory. The music is nostalgic in mood. Every movement has a motto, taken from Dunbar's poem, "The Deserted Plantation." The Spiritual in the (third movement) is an adaptation of the well-known "I Want Jesus to Walk With Me"—the exception to his rigid rule about employing alien themes in his serious works. On its performance in 1933, the critics came out with an interesting disagreement. One said it was not Mr. Still at his best, while another characterized it as "skillfully constructed music" and lauded it from many different standpoints.

Two other symphonic works, written during the period of his Guggenheim Fellowship, and more worthy of serious consideration, are the poems Dismal Swamp (which employs a solo piano at intervals) and Beyond Tomorrow —the latter unperformed as yet.

Beyond Tomorrow is dedicated to Still's four children. It is melodic throughout, and hauntingly beautiful. When it is played in public, Paul Whiteman may be the first to introduce it, for it was written on a commission from him, though it is entirely different in treatment, thought and scope from anything Still had ever done for him before.

Dismal Swamp is a musical portrait of a dreary swampland that assumes a strange wild beauty as the visitor progresses farther into it. It is based on a single theme, moves slowly, and rises to a tremendous climax. This was played by the Orquesta Sinfonica de Yucatan under the direction of Samuel Marti three times in 1938; Dr. Hanson has also programmed it in Rochester. It was dedicated to Quinto Maganini.

IX—

Piano Music

Until 1934, almost all of Still's works were for orchestra, for that was his field. He felt at home in it as he did in no other. True, some piano reductions of his orchestral works had been made, and he had used the piano as a unique addition to the orchestra in several of his symphonic works. The Black Man Dances for piano chiefly, with orchestral accompaniment, came suddenly and was the forerunner of many more interesting and lovely works for that instrument. This suite of dances rep-

resents four characteristic phases in the life of the Race. The first is an African flute serenade. After a short introduction, the flute has the principal and sole theme, which is thereafter embellished with little piano cadenzas. The second is a tribal dance, in which the entire ensemble is used more rhythmically than melodically. The third section is a Barrel-house episode, reminiscent of the blues and of old-time ragtime piano players and player pianos. The last is a Shout, expressing the religious ecstasy of the Negro in rather free and joyous style. It is much fuller for piano than either of the three preceding dances. This suite was commissioned by Paul Whiteman and is as yet unperformed.[7]

It would be incorrect to class this suite as "great" music, or even to say that it fully utilizes the possibilities of the piano as a solo instrument. However, it is important because it served as a prelude to other piano works by Still that are truly inspired and that not only display a more intimate knowledge of the infinite possibilities of the piano, but utilize those possibilities in hitherto unsuspected ways. For that reason, Still's piano music is difficult for the contemporary pianist to grasp.

Kaintuck', for piano and orchestra, is short and poetic, but equally as strong as Still's previous works. As a matter of fact, a careful study reveals it to be by far the finest work for piano to date of any Negro composer. Its creation came easily. It was written to express musically his inner reactions to the peaceful, shimmering, misty sunlight on the blue grass of Kentucky. It is a subjective not an objective picture, however. Kaintuck' is built chiefly on two themes: everything else grows out of them. The piano opens the poem quietly, then runs into a rhythmic accompaniment to the orchestral statement of the themes. Both the piano and the orchestra are heard in huge, authoritative chords just before the cadenza by the solo instrument. This cadenza, unlike most, does not aim toward the exploitation of the interpreter, but simply and colorfully enhances the thematic and harmonic material that has preceded it. The theme is re-stated, and the piano closes the poem as quietly as it opened it. It is haunting, memorable. It was first played on two pianos at a Los Angeles Pro Musica concert, with Verna Arvey, to whom the work is dedicated, at the solo piano. Since then, Dr. Hanson has played it in Rochester and Eugene Goossens in Cincinnati. The composer has also conducted it in his own orchestral concerts in Northern and Southern California, with Verna Arvey as soloist.

One of the finest groups of piano compositions to be written by any American composer is the Three Visions by William Grant Still, published by J. Fischer and Bro. The harmonies in these Visions are strange.

Example 18.

"Dark Horseman," from Three Visions for piano.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

Example 19.

"Summerland," from Three Visions .

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

By them, the listener is aware that the "visions" are real only to the dreamer. As music, they exemplify the scope of Still's musical individuality. Once again, he has given us strongly contrasted moods, unified by his own personal idiom and by his spiritual concept of the music he creates. The first Vision is one of horror. It is entitled "Dark Horsemen," and in it the hoof beats of the horses alternate with the shrieks of anguish they cause by their very presence (example 18). The second Vision is a portrait of promised beauty in the afterlife. It is called "Summerland," after the peaceful Heaven of the Spiritualists (example 19). It has been arranged by the composer for small orchestra, and published. The last Vision is of the radiant future, a vision of aspiration that is ever-climbing, never-ending. It is called "Radiant Pinnacle" (example 20). Its continual rhythmic flow and its final, deceptive cadence leave one with the feeling that there is more to come: that the last word has not been said.

"Quit Dat Fool'nish" was composed as a little encore piece for Kaintuck' . It is for piano alone, as are the Visions . So joyous and effervescent is it that, when played as an encore, it has often been known to be encored on its own account!

Example 20.

"Radiant Pinnacle," from Three Visions .

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

X—

Spiritual Arrangements

Perhaps because, until his time, most Negro composers had won fame purely as arrangers of Spirituals and not on creative efforts, and because a great many people harbored the delusion that their work should stop there, Still made it a point not to arrange Spirituals (except when he was required to do so, in his commercial arranging) for many years. However, during the period of his Guggenheim Fellowship, the talented writer, Ruby Berkeley Goodwin, approached him with several short stories she had built around familiar and unfamiliar Spirituals. She needed new and distinctive arrangements, so Still agreed to make them. He arranged twelve for solo voice and piano; and these, along with the accompanying stories, are now published in two volumes by the Handy Brothers Music Publishing Company. Three of these ("Gwinter Sing All Along de Way," "Keep Me F'om Sinkin' Down" and "Lawd, Ah Wants To Be a Christian") have recently been arranged for chorus by the composer. Others in the group are "All God's Chillun Got Shoes," "Lis'en To De Lam's," "Great Camp Meeting," "Great Day," "Good News," "Peter, Go Ring Dem Bells," "Got a Home in Dat Rock," "Mah Lawd's Gonna Rain down Fire" and "Didn't Mah Lawd Deliver Daniel?"

There is one thing that makes these arrangements unique among Spiritual arrangements: they are as characteristic as the spirituals themselves. Through long years of visiting small Negro churches in search of little-known Spirituals, of hearing groups of people sing them spontaneously in revivals or shouting in ecstasy at basket meetings, Still learned that the usual, conventional arrangement robs the Spiritual of its folk flavor. No wonder people discover Caucasian influences in them, thought he, when often their whole characters are altered by the foreign quality of their arrangements!

If there is a trace of Caucasian influence in the Spirituals themselves, it resolves itself into a case of the music of the white emerging trans-

formed form the soul of the colored man. However, the rhythmic, stirring, emotional Spirituals are purely African in essence. The secular folk music of the American Negro is the Blues, and these are far more Negroid than the Spirituals, on the whole. Still has no delusions as to the triviality of Blues, despite their origin and the homely sentiments of their texts. The pathos of their melodic contents bespeaks the anguish of human hearts and belies the banality of their lyrics. They generally conform to a definite pattern that affects lyrics, form and mood of the music.

Still's high regard for the Blues is shown by the fact that he based his Afro-American Symphony entirely on a blues theme—an original one, not borrowed from an anonymous day-laborer or field-hand, nor yet from any published composition—and made it into a creation of haunting beauty and noble sentiment.

XI—

Blue Steel

By far his most powerful completed work to date is Blue Steel, an opera on a plot by Carlton Moss and libretto by Bruce Forsythe. The subject is Negroid. The scene is a mythical swamp. The protagonists are a Negro from Birmingham (Blue Steel), a young girl of a voodoo cult (Neola), a high priestess of the cult (Doshy), and a high priest (Father Venable), Neola's father. Inevitably there is a conflict between black magic and materialism. Black magic, with the aid of the faith of centuries, is the victor. Musically, Still has used every element possible to bring about a powerful and compelling climax, from the moment the arresting "Blue Steel" motif introduces the opera, to the final chords. His choruses and drum rhythms are thrilling; his melodies unforgettable. The entire first act is made up of lovely arias, melodies that are emotional, facile and even psychological. The second act is made up mainly of exciting rhythmic choruses and a characteristic ballet dancing the sacred rites for the ceremony of renewal. At the end of the act, Blue Steel shoots the high priest who has attempted to dissuade Neola from eloping with the luring stranger. In the last act, Blue Steel and Neola try to escape, but the voodoo chants and drums have their effect on him, and he leaps madly to his death in the quicksands of the river.

Throughout the opera, Still has employed the logical, but seldom as dexterously-used device of indicating musically the mood of the moment. That is, when Blue Steel tells of the bright lights and glories of the cities,

the music assumes a jazz form, harmonically and rhythmically seeking, while the melody remains true to the whole outline of the opera. When Blue Steel becomes terrified and looks toward his own God for aid, the music assumes the outward characteristics of a Negro Spiritual.

Blue Steel was not only the climax to years of study and effort, but the beginning of broader creative conceptions, for since its composition, Still has begun work on a new opera that bids fair to surpass the first one in dramatic intensity and genuine beauty. This one will be called Troubled Island . Its libretto is by the famed Afro-American poet, Langston Hughes, and its plot was taken from Haitian history: the short but tragic career of the ill-fated Emperor Dessalines.

Needless to say, this vehicle is more logical than the preceding, since it is founded on fact, not fantasy. The poet has created lines of great beauty to which the composer has responded with all the intensity of his creative nature.

There may be a little authentic Haitian musical material in it when it is finished, especially in the market scene, but for the most part, the composer will do as he has always done in the past: create his own themes and treatments as being truer to the story.

Troubled Island, like Blue Steel, is built around a baritone soloist in the leading role. Here, too, the music assumes the character of the actors' thoughts, for when Paris is mentioned, the music becomes light, gay and sophisticated. Brutally ugly is the theme for Dessaline's scars; portentous is the revolutionary theme; strongly Negroid and dignified is the theme for Martel, the aged advisor who speaks of the kingly pride of their African forebears.

XII—

Lenox Avenue and Radio Music

William Grant Still often mentions the similarity of the theme of his Lenox Avenue to that of Blue Steel, and insists that he did it on purpose, to ally the voodoo story with the raucous and tender rhythms of modern Negroid life. In fun, he says it happened because Blue Steel used to live on Lenox Avenue and liked it there.

Lenox Avenue is a series of ten orchestral episodes and finale, built on scenes the composer had witnessed in Harlem, for orchestra, chorus and announcer, the narration being written by Verna Arvey. This was commissioned by the Columbia Broadcasting System on the first American Composers' Commission. It received its first performance over a national broadcast under the baton of Howard Barlow on May 23, 1937

and was repeated on October 17, 1937. The composer has since conducted it on many occasions in concert.

The themes had been gathering for many years, and Still had even made a tentative effort to shape them into a composition.[8] When the commission for CBS, in the shape of a telegram from Deems Taylor, arrived, Still realized that the perfect form for this musical material was at hand, in a symphonic work to be built directly for a radio audience. Still has never asserted that in Lenox Avenue he created a new form. After all, on the Deep River programs long before, the announcer had spoken over musical interludes. Thus Still simply took something old and applied it in a very special way: made a coherent fusion of all the elements. It was, indeed, the first time such a thing had been done in a single musical work.

Out of one hundred and seventeen letters received directly concerning Lenox Avenue after its initial broadcast, not more than six were unfavorable. Those were not all unqualified disapprovals. Some were emphatic in their disapprovals, however, and asked for more nineteenth century music instead. Many of them said they were writing for the first time. One listener wrote: "I tuned in as usual, expecting nothing more than an hour of interesting music, competently played. And then the opening bars of Lenox Avenue! I can only describe the impression it created in me by saying that I felt the same emotion as when for the first time, thirty-seven years ago, I heard Charpentler's Louise . . . . If Charpentier has described in sound the magic of Montmartre, the brief glimpse of happiness love can give to a Parisian coquette before she once more disappears into the anonymous sea of mediocrity, Lenox Avenue has done much the same thing for another type of humanity." Wrote another: "If anything, Lenox Avenue is a bit too authentic. It is truly everybody's music." Another: "I have a difficult time enjoying or understanding most of the modern compositions of our day, but this music impressed me differently . . . from the depth and warmth of the music emerged a soul."

Lenox Avenue was later converted into a ballet, and in this version was introduced by the Dance Theatre Group in Los Angeles in May of 1938, with choreography by Norma Gould and with Charles Teske dancing the leading role of "The Man From Down South."

One of the best liked of all the sections in Lenox Avenue was that of the Philosopher, although, strangely enough, this melody did not come to the composer during the actual creation of the work. It was after he had finished it and had composed an entirely different section that this

Example 21.

"The Philosopher," from Lenox Avennue .

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

Example 22.

"Blues," from Lenox Avenue .

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

bit of inspiration came (example 21). In sharp contrast is the Blues in the House Rent Party Scene, reminiscent of barrel-house piano players (example 22).

When the Theme Committee for the New York World's Fair of 1939 wished to find a truly American composer to write the Theme music for the Fair, it heard records of the works of many American composers without the names of those composers being revealed. Among those records were A Deserted Plantation and Lenox Avenue . On hearing these, the Committee decided that this composer was the man needed to write the six-minute musical background for the City of Tomorrow in the Theme Center. He was, of course, William Grant Still.

On a description by Henry Dreyfuss, designer of the Theme Center, and by Kay Swift, Still set out to compose this music with stopwatch, much as he would have composed film music (for among his many experiences has been that of working in the music departments of Hollywood's studios) although this music was necessarily more inspired than film music could ever be. It is also unique, unlike anything Still has ever written before, for its idiom is more or less universal. There is nothing Negroid about it. It contains two memorable, rhythmic melodies. On its completion, Henry Dreyfuss wrote enthusiastically to Still to thank him for all of his "self" that had gone into the music.

XIII—

Still's Orchestration

It has been justly said of some composers that they are merely skillful orchestrators but are barren creatively, as is shown when their works are reduced to a minimum. This is not true of Still. Though his orchestral works are not as effective in a piano reduction as in the original scoring, they yet retain that harmonic piquancy and thematic originality that are distinctly his own.

Dr. Hanson wrote to him, "I heard a part of some charming selections from your pen over the radio last night. As usual, I was impressed with the highly colorful and original type of orchestration you have developed. Even over the radio it sounds very convincing."

Some people moan that orchestral resources have been exhausted. Still disagrees with that belief. His trouble lies in making a decision between so many fascinating orchestral possibilities.

When he first began to orchestrate, he imitated others, but always tried to choose the best to imitate, not those who were too individual, so that he would not acquire mannerisms. As soon as possible he broke away and began to experiment with different orchestral effects by himself, so that he would have a greater fund of knowledge at his command. To his amazement, he found that many effects which were strictly forbidden were really quite effective and were, when used with modifications and with regard to the limitations of the various instruments, most fascinating. He thus learned that everything is possible when approached in the right way. Now he never accepts statements about impossible instrumental combinations without first trying them out.

The more he scores, the more convinced he becomes that the simplest style gets the best results and is the most effective in the end. Nevertheless, in the art of orchestration, he found that he must include many things that are not actually heard during the performance, but which are absolutely necessary to the general effect. His orchestrations are so carefully worked out that if the exact combination for which he has scored is not available, the music sounds wrong. Similarly if the balance is bad in a broadcast or a recording, and a single instrument is missing or out of proportion, everything is thrown out of line. This sometimes results in the music sounding like Jazz, when it was not intended to sound that way at all.

Copyists comment on the many rests in his scores. He believes that one of the secrets of good orchestration is to know what to leave out,

and when. Only the beginner uses all the instruments constantly, just because they are available.

"In orchestration, art and science must work together," declares Still.

Often a tone color in one's mind will defy actual reproduction through physical means, but it can be approximated. The proper choice of instruments depends on the orchestrator's ability to hear at will the tone of any instrument in any register. In scoring, a tasteful variety of tone-color is necessary. One may define that as "pleasing contrasts that are related," and the relationship should be one of mood. One must choose the instrument that best portrays the desired mood. It follows that one must have an intimate acquaintance with all the instruments. They must assume the importance of personalities to the orchestrator.

The use of certain instruments may entirely change the character of various themes or melodies.

Clarity (where each voice is proportionately distinct) is necessary, and is gained by not over-orchestrating. It is worse to over-orchestrate than to orchestrate thinly, for the ear has limitations. The melody should always stand out. This is what I call a "nude" style of orchestrating. Balance is also necessary, and is gained more by cold calculation than by artistic sensibilities. It has to do with instrumental combinations. Clarity often depends on balance, for a badly balanced orchestration can never be clear.

XIV—

Still's Image and Style

In the musical world of today, Still is a dignified, sophisticated figure. He is far from exemplifying the popular conception of a Negro composer. One recalls the mistaken, but well-meaning lady who scanned a copy of Still's Kaintuck' and asked at what point precisely did the saxophones enter, and who seemed alarmed when the colored composer (who by all rights should have had a battery of saxophones in his score) responded that there were no saxophones in Kaintuck' . "No saxophones?" she queried, in dazed fashion. And then one cannot avoid mentioning the people who have been told that all colored people are imitators and who therefore search Still's music diligently for some evidence of imitation, be it ever so small. Still has been accused of imitating composers who were known plagiarists; he has been accused of imitating men who openly avowed their indebtedness to Negro music; he has also been accused of imitating composers he never heard of. As a matter of fact, his style is so individual and so fascinating, once one is really acquainted with it, that it is as recognizable as Bach's, or as Brahms'.

Still has few recreations. He is not a "social" person. Almost all of his time is spent in steady, feverish work, in an effort to get everything done,

to say all he must say before it is too late. One afternoon a visitor entered. "It's so warm today!" he remarked.

Still looked up from his composing. "Is it?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Then I guess I'd better take off my coat."

It wasn't a pose, that absorption in work. Nor is his modesty a pose. Whenever he feels that he has done something worthwhile, whenever something pleases him, or whenever a new honor is accorded him, he sits down and humbly gives thanks to God, the Source of Inspiration. That is the real clue to his personality: his profound reverence.

People are already beginning to regard him as a great man. He hears the things they say and is grateful for them, but he is never impressed with his own importance. At a meeting of the NAACP, after the speeches had been unusually long, someone noticed that the renowned composer, Mr. William Grant Still, was in the audience. Would Mr. Still consent to speak to them on some matter of moment? The famed Mr. Still arose in an impressive silence. Then, with all eyes focused on him: "I wonder," said he quietly, "whether everyone is as hungry as I am?" Then he sat down, and the meeting was dismissed.

William Grant Still, a genuine American composer, will become world famous. When he does, he will be the last person in the world to know it, or to believe it if the knowledge is thrust upon him!

XV—

Conclusion

As Still made history for the Afro-American when he was first to conduct a white radio orchestra in New York City and first to write a symphony, he also made history when he conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in two of his own compositions at a Hollywood Bowl summer concert in 1936, for it was the first time in the history of the country that a colored man had ever led a major symphony orchestra.

He is a member of the Pan American Association of Composers and of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). He is also the recipient of a 1934 Guggenheim Fellowship which was twice renewed for periods of six months each.

He is mentioned in the following books, among others: Composers in America by Claire Reis; Complete Book of Ballets by Cyril W. Beaumont; Ballet Profile by Irving Deakin; Composers of Today by David Ewen; Negro Musicians and Their Music by Maude Cuney-Hare; So This Is Jazz by Henry Osgood; The Negro and His Music by Alain

Locke; American Composers on American Music by Henry Cowell; The Negro Genius by Benjamin Brawley, and in the Fall (1937) issue of the New Challenge, a literary quarterly published in New York City.

Publications [through 1937][9]

Darker America . C. C. Birchard Co. for the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester, 1928.

"Winter's Approach" and "Breath of a Rose" (songs). G. Schirmer, Inc., 1928.

Afro-American Symphony . J. Fischer and Bro., 1935.

Deserted Plantation, piano arrangement of three sections. Robbins Music Corp., 1936.

Three Visions, for piano solo. J. Fischer and Bro., 1936.

Dismal Swamp . San Francisco: New Music Society of California, January 1937.

Scherzo, from Afro-American Symphony, arranged for small orchestra. J. Fischer and Bro., 1937.

"Summerland," from Three Visions, for small orchestra. J. Fischer and Bro., 1937.

Twelve Negro Spirituals, for solo voice and piano, three of them arranged and published for chorus. New York: Handy Bros. Music Co., Inc., 1937.

"Blues," from Lenox Avenue orchestral score. J. Fischer and Bro., 1938.

Lenox Avenue, piano score. J. Fischer and Bro., 1938.

Quit dat Fool'nish, piano solo. J. Fischer and Bro., 1938.

"Rising Tide," theme song commissioned by the New York World's Fair during 1938. Arrangements (a) for orchestra, (b) for piano solo. J. Fischer and Bro., 1938.

Performances [through 1937][10]

From the Land of Dreams, for 3 voices and chamber orchestra, performed by the International Composers' Guild, Inc., in New York on February 8, 1925, under the direction of Vladimir Shavitch.

Levee Land, performed in New York on January 24, 1926, by the International Composers' Guild, Inc., with Florence Mills as soloist and Eugene Goossens conducting.

Darker America, performed by the International Composers' Guild, Inc., in New York on November 28, 1926, with Eugene Goossens conducting.

From the Journal of a Wanderer, played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Frederick Stock at the Chicago North Shore Festival Association in 1926.

From the Black Belt, for chamber orchestra, played by Georges Barrère and the Barrère Little Symphony at the Henry Miller Theatre in New York on March 20, 1927.

Log Cabin Ballads, played by Georges Barrère and the Barrère Little Symphony at the Booth Theatre in New York on March 25, 1928.

Africa, a symphonic suite, performed by Georges Barrère and the Barrère Little Symphony at the Guild Theatre in New York on April 6, 1930.

Afro-American Symphony, performed at an American Composers' Concert at the Eastman School in Rochester, New York, in 1931 under the direction of Dr. Howard Hanson.

Sahdji, ballet for chorus, orchestra and bass soloist, performed at the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York, on May 22, 1931, with Dr. Howard Hanson conducting.