The Evolution of Clerical Work

The term employee brings to mind a hoard of clerks hunched over their ledgers. The gas company did have many such workers among its personnel, but the label needs to be understood in a broader sense. To be an employee was not precisely a matter of doing a specific form of work;

[1] A. J. M. Artaud, La Questionde l'employé en France (Paris, 1909); Auguste Besse, L'Employé du commerce et de l'industrie (Lyons, 1901); Gaston Cadoux, Les Salaires et les conditions du travail des ouvriers et des employés des entreprises municipales de Paris (The Hague, 1911); Ministère du commerce, Office du travail, Seconde enquête sur le placement des employés, des ouvriers, et des domestiques (Paris, 1901).

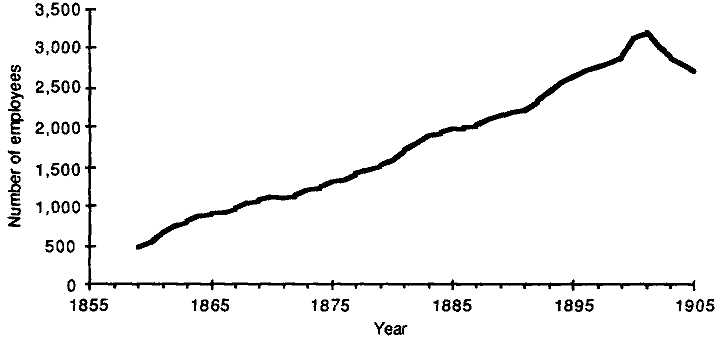

rather, it meant having a particular relationship to the firm. The company had a permanent commitment to its employees and would dismiss them only for serious derogation of duty. Borrowing from the language of the military, the firm gave its employees a "commission," which offered a permanent career within the firm. The chief executive of the PGC may have kept his distance from factory workers, but until circumstances rendered the practice unwieldy he held a personal interview with each candidate for a post as an employee. The interview underscored the status of the clerk as a part of the managerial apparatus.[2] Executives usually referred to employees as "agents" of the company. The PGC expanded its commissioned personnel as fast as its manual labor force, with just under a sevenfold increase during the life of the firm (figure 10). That legendary bureaucracy, the French state, had about twenty-nine hundred employees in its ministries around the time of the Franco-Prussian War.[3] This was the corps that, according to Jules Simon, ran the nation while the deputies debated. The PGC already had half as many agents and began to surpass the ministries by the end of the century.

Bookkeepers were a significant portion of the new sort of labor force but by no means all of it. The PGC had four types of agents: the clerical workers proper, wielding pen and paper; uniformed agents, who worked outside the office; technical personnel, who evaluated and supervised equipment and capital additions; and manual laborers, whose supervisory role was thought important enough for the company to try to bind them in a special way to the firm.[4] The first group constituted about half of the commissionable employees (898 of 1,915 in 1884). They were divided into some thirty distinct units (bureaux or sections ). Their official titles, displaying much variety, included accountant (comptable ), secretary (commis ), and especially bookkeeper (employé à l'écriture ). Outside the offices were three large and increasingly vocal groups of uniformed, active (as opposed to sedentary) agents. The corps of meter readers (contrôleurs de compteur ) numbered 332 by 1892. Bill collectors (garçons de recette ) comprised a hybrid group that did not enjoy the full dignities of employee status. As the French name implies, they were generally young men, often

[2] AE V 8 O , no. 666, deliberations of August 17, 1858. The directive was never formally rescinded. See chapter 4 for a discussion of the director's aloofness from factory laborers.

[3] Guy Thuillier, La Vie quotidienne dans les ministères au XIX sièle (Paris, 1976), p. 9.

[4] The corporate archives include four rather complete organizational charts of the personnel spanning the life of the firm. For 1858, AP, V 8 O , no. 665 (fols. 500-514); for 1884, no. 153, "Personnel"; for 1893, no. 154; for 1902, no. 162, "Assimilation."

Fig. 10. Number of White-Collar Employees at the PGC.

From AP, V 8 O1 , no. 1294, "Groupe de l'Economie sociale."

recruited among the office boys, who were expected to leave their jobs as they matured.[5] The responsibilities of the lighting inspectors, who numbered 184 in 1884, had many facets. Stationed in neighborhood offices (called lighting sections), they served as liaisons of first resort between the customers and the company. As such, they saw to it that customers had the proper paperwork, collected deposits, received complaints, and initiated service orders. Furthermore, they were in charge of street lighting, supervising the lamplighters and making rounds at the hour when the lights were extinguished. None of the active, uniformed agents could work bankers' hours. Their schedules essentially were task-oriented, and Sunday labor was part of the routine until they successfully prevailed on the municipal council to end it in the 1890s.[6]

The production and distribution of gas created the need for technical personnel. Men with know-how in fitting, plumbing, or construction inspected the thousands of kilometers of gas main owned by the company. They also oversaw the installation of new lines when private contractors did the actual work. The granting of employee status to factory foremen (contre-maîtres ) was a measure calculated to induce greater loyalty. Man-

[5] Ibid., no. 753, "Bureau des recettes," report of July 6, 1871. The PGC did not wish to consider the bill collectors full employees, partly because they received tips from the customers as a portion of their compensation and thus were beholden to a public beyond the firm.

[6] Ibid., no. 148, "Eclairage—Personnel"; no. 153, "Revendications des contrôleurs de compteurs." A directive of 1864 ordered inspectors to keep an eye on the coke deliverymen as they made their rounds. See no. 1081, ordre de service no. 192.

agement had initially treated them as superior wage earners, but the fore-men took advantage of an intense labor shortage in 1867 to demand better pay. The response of the company (fitting a pattern that should now be familiar) was to commission them and disregard the wage demand.[7] As we have seen, the PGC pursued the same strategy in 1892, when it feared the involvement of coke team chiefs in the trade union movement.

An influential model describing the degradation of clerical work was first elaborated by German social thinkers anxious about the explosive growth of the service sector in their country. They wondered whether economic change was creating a new sort of middle class or a new proletariat.[8] Their analysis of the proletarianization of employees has become a standard approach for British and American scholars.[9] The question of clerical work has received much less attention for France, perhaps because enterprises tended to be smaller and because other groups were more vocal.[10] Since fin-de-siècle France did witness the emergence of an "employee question," the proletarianization model is well worth exploring.

According to the model, a clerical career had been a path to independence before the industrial era. Like the artisan, the preindustrial clerk did a whole range of administrative activities so that he was ready either to strike out on his own, become a partner in the master's firm, or take over the family business. The expansion of large-scale organizations presumably altered the situation. A clear-cut distinction between managers and clerks arose; office work became just as subdivided as the handicrafts.[11] The employee spent his (and increasingly her) life doing one task, from which there was no escape. The job was no longer a career and certainly

[7] Ibid., no. 672, deliberations of December 23, 1867; no. 767, "Proposition concernant le service des conduites montantes (1 mai 1873)"; no. 773, "Service mé-canique," report of April 20, 1867; no. 780, "Personnel—Service mécanique."

[8] Fritz Croner, Soziologie der Angestellten (Berlin, 1962); Jürgen Kocka, Die Angestellten in der deutschen Geschichte, 1850-1900 (Göttingen, 1981).

[9] David Lockwood, The Blackcoated Worker: A Study of Class Consciousness (London, 1958); Margery Davies, Woman's Place Is at the Typewriter: Office Work and Office Workers, 1870-1920 (Philadelphia, 1982); Jürgen Kocka, White Collar Workers in America, 1890-1940 (London, 1980). For an up-to-date bibliography and nuanced discussion of the issue, see Heinz-Gerhard Haupt and Geoffrey Crossick, eds., Shopkeepers and Master Artisans in Nineteenth-Century Europe (London, 1984).

[10] Historians of France have paid far more attention to salesclerks. See Michael Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store , 1896-1920 (Princeton, 1981); Theresa McBride, "A Woman's World: Department Stores and the Evolution of Women's Employment, 1870-1920," French Historical Studies 10 (1978): 664-683; Claudie Lesselier, "Employees de grands magasins à Paris avant 1914," Le Mouvement social , no. 105 (1978): 109-126.

[11] On the handicrafts, see Lenard R. Berlanstein, The Working People of Paris , 1871-1914 (Baltimore, 1984), pp. 74-92.

not preparation for an independent future. Employers could easily enforce a tight discipline because they could train new people to do specialized tasks in a matter of weeks. In short, the employee had become a proletarian of the office. Of course, scholars have been careful to distinguish between objective and subjective aspects of proletarianization. The degradation of work might have led employees to support leftist internationalism, or status anxiety and the politics of resentment could have pushed them into the reactionary camp. The indeterminacy of the clerks' reaction to new work prospects makes the model all the more interesting to explore empirically, especially in view of the burgeoning of mass, extremist parties in fin-de-siècle Paris. But first we must ask to what extent the degradation of clerical work actually occurred.

The PGC may have hired a small army of employees, more than any other manufacturing firm in Paris, but that army did not, on the whole, fit the image of a vast, undifferentiated, routinized hoard of bookkeepers. The model comes closest to being accurate in the largest clerical department, customer accounts. There clerks calculated bills from figures the meter readers supplied and posted payments. The department contained 14 percent of the employees (in 1884), and they were divided into two distinct bureaus, billing (comptes courants ) and payments (recettes ). The routinized activities of adding figures, verifying them, completing forms, filing, and reconciling ledger sheets filled the work time of the clerks.[12] With the democratization of gas use at the end of the century, these bureaus necessarily expanded. The customer accounts department, at its largest, had just under six hundred employees, 18 percent of the tenured personnel.

No other concentration of bookkeepers was as large. The rest of the clerks worked in relatively small units: the office of the machinery department had a staff of eight, the legal department twelve, and the central factory bureau twenty-three.[13] Tasks in these units were not subdivided or specialized. Rising to the post of assistant bureau head (sous-chef ), which usually went to the clerk with the most seniority, was not an unreasonable expectation. Even in the customer accounts department there was a sense of career hierarchy and differentiation. The clerks who headed payment sections presided over an assistant and over several bill collectors; they thought of themselves as having achieved a position of some standing in the office. Eventually they demanded tenure (titularisation ) in their posts,

[12] A detailed description of work procedures in the customer accounts department is provided in AP, V 8 O , no. 153, "Rapport à MM. les administrateurs."

[13] The personnel documents cited in note 4 provide data on the size of clerical offices and departments.

which the company was unwilling to recognize as a fixed status.[14] Diluting the proletarianizing features of the customer accounts department even further was the practice of moving young clerks who started there into smaller offices as they matured.

Among the active agents, meter readers fit the proletarianization model, but the lighting inspectors were decidedly more difficult to classify. In general, the inspectors' work was routine, but their responsibility for certifying the proper functioning of residential fixtures required care. When a concierge was killed in an explosion in 1884, the defense of having followed proper procedure did not prevent an inspector from spending three months in prison for criminal negligence. Moreover, inspectors represented the authority of the company to the customers and were the supervisors of laborers, the lamplighters and greasemen. The uniformed agents were supposed to spy on those wage earners as they made their rounds, and a negative report could get them fired or fined.[15] As for the technical agents or foremen, they were hardly candidates for repetitive, specialized work.

Another qualification to the claim of proletarianization was the stratified structure of the employees' corps. There was a career ladder. All clerks started at fifteen hundred (later eighteen hundred) francs a year and advanced by steps of three hundred francs to thirty-three hundred francs (occasionally more). Furthermore, just over 10 percent of the employees were office heads or assistant office heads, about the same portion as in the state bureaucracy.[16] The hierarchy of clerks also included principal employees (commis principaux ), supervisory inspectors, supervisory meter readers, chiefs of lighting sections, and other positions that stood above the common sort. Among the employees who were above the age of fifty, 32 percent (in 1884) were more than simple clerks[17] Thus, despite its exceptional size, the PGC had not produced a consistently flattened, homogenous, and routinized personnel. Hierarchy, unspecialized assignments, and the possibility of promotion persisted. To be sure, the career trajectory no longer ended in anything like independence, but distinctions remained, and they seemed to matter to the employees.

The model of proletarianization presupposes that clerical work became ever more intense, tightly supervised, and rationalized, especially in the growing number of large firms. To what extent did big businesses like the

[14] AP, V 8 O , no. 153, report of Dufourg to director, November 16, 1892.

[15] Ibid., no. 148, "Eclairage—Personnel"; no. 828, report of Duval to director, July 30, 1884.

[16] Thuillier, Vie quotidienne , p. 9.

[17] AP, V 8 O , no. 153, "Personnel."

PGC create a new mode of office work that opened a dismal stage for white-collar employees? Of course, France had a less dramatic transition from the small-scale and the familial to the large bureaucratic organization than did some of its neighbors, not only because its pace of industrialization was more gradual: France had an old bureaucratic tradition based on the state. The nineteenth-century civil servant provides an important frame of reference and point of departure for evaluating clerical work at the PGC. Honoré de Balzac, along with other writers, had already made the fonctionnaire a stock figure characterized by stifled ambition, directionless plodding, a degree of indolence, and anxiety over status. In truth, the PGC would not have had to drive its personnel very hard to match the productivity of civil servants. A parliamentary commission of 1871 arrived at the conclusion that they accomplished no more than three to four effective hours of work a day. The standard day of seven hours, ten o'clock to five o'clock with no interruption for lunch, contained many informal breaks. Clerks ate a midday meal at their desks and did not readily countenance interruptions in it despite the absence of an official lunch hour. The work culture of civil servants was rich in subterfuges designed to avoid steady labor. The ritual of taking a smoke could keep an employee outside the office for several minutes at a time. In some ministries clerks enjoyed by custom the right to absent themselves from their desks momentarily a few times a day. Where this right was not recognized, a clerk was allowed to retrieve the hat or umbrella he had "forgotten" at the café that morning. Even when employees were at their desks, office chiefs experienced frustration when they tried to impose stringent work rules. In this panoptical age the technologies of surveillance were still primitive at the ministries. Offices grew haphazardly Clerks worked in small, makeshift settings scattered about the ministries. Not until the Second Empire was nearing its end did ministers begin to rationalize the space within their bureaus. It is no wonder that the public had to expect a delay of two months or more before receiving a reply to a letter.[18]

Change did not take place quickly in the civil service. The penetration of laborsaving technology had to be measured in generations. Metal pens first began to replace quill pens in the 1850s, but the process was barely complete thirty years later. Just around the turn of the century the pace of technological change did accelerate as typewriters and keyboard adding machines made their appearance. With this new machinery came a decisive break, the feminization of the ministerial bureaus. Female typist-

[18] Guy Thuillier, Bureaucratie et bureaucrates en France au XIX siècle (Geneva, 1980), pp. 301-363, 423-562; Thuillier, Vie quotidienne , pp. 29-47, 70-155.

stenographers took the place of copyists, the lowest job on the promotional ladder within the ministries.[19]

The feminization of the civil service announced the impending death of an important tradition, unitary recruitment. The ministries had always required clerks to demonstrate a variety of skills. Copyists and lesser civil servants had to write neatly and do elementary numerical calculations, accomplishments that a primary-school graduate could command. At the upper levels of the office hierarchy were the rédacteurs, who had much more responsibility. They drafted correspondence from the chief's marginal notes and even disposed of simple matters, subject to a superior's approval. A law degree, or at least a baccalauréat, was necessary for this level. In the face of the diversity of needs, ministries hired only one type of clerk, one who could become a rédacteur and, eventually, office head. Critics of the civil service noted that unitary recruitment did not produce an invigorating climate of work. Highly educated young men were oppressed by years of waiting for an opening at a level appropriate to their training. Secondary-school and university graduates spent years doing assignments that a primary-school pupil could have handled. The critics contended that the standard thirty-year career from copyist to assistant office head was beneficial to no one, not the employee and not the minister. They called for the separate recruitment of copyists and rédacteurs so that better-educated youths could advance more quickly through the ranks. Of course, the plan would create dead-end careers for the copyists. Whatever the merits of the reform, it did not happen quickly. Initiatives foundered on bureaucratic inertia and loyalty to tradition. It took the female typists to break the old mold and make dead-end careers as copyists acceptable to the prevailing powers.[20]

Promotions through the grades (pay levels) of the civil service were a gray area in state employment. The public considered it natural and inevitable that civil servants would advance from one pay step to another on the basis of seniority. To be evaluated on the basis of service rather than performance was taken as a prerogative of the fonctionnaire. In fact, there was no fixed right to promotion by seniority; it was a matter of custom. When custom was observed, seniority brought the state employee only priority over younger colleagues for advancing to the next grade. Since the number of posts at each level was fixed, the employees had to wait for an opening. Office clerks would demand the right to a promotion after a predetermined number of years, but civil servants did not yet enjoy such

[19] Thuillier, Vie quotidienne , pp. 155-210.

[20] Ibid., pp. 195-225; Thuillier, Bureaucratie , pp. 291-294.

a prerogative.[21] Nor for that matter were there regulations on dismissals, bonuses, or pay The minister was absolute master of his personnel, at least in principle. Over the years, the Council of State had rebuffed all efforts to limit discretionary power. Parliament considered reform from time to time but never succeeded in mustering a majority to endow civil servants with formal rights. In practice, the custom of advancements based on seniority was interrupted by exceptions based on nepotism or political considerations. Since ministers were not permanently attached to the administration, their concern about long-range efficiency was not great.[22]

To what extent did the PGC, as one of the new large-scale, private organizations, create clerical work that was clearly different from that of the state bureaucracy? As both management and clerks themselves struggled with the issue of what office work in private enterprise would be like, the situation of the fonctionnaire served as an influential model. Decision makers within the PGC wavered on how much they wished to borrow and depart from the model. They admitted from the start that the office personnel should have permanent careers and retirement plans, as civil servants did, but thinking about the administration of the employees on other matters shifted repeatedly.[23] The director issued regulations on fining and then renounced them as unworkable. In 1856, and again in 1859, he proposed a framework for ranking and promoting clerks along with a step system for pay (the grades of the civil service). They fell into disuse, however, and in 1861 the head of the distribution division offered a new plan for structuring the clerical personnel.[24] The evident confusion came to a head in 1863. Proud of its accomplishments in rationalizing manual labor, management turned to the still-untidy situation in the bureaus. The executive committee held at least six special sessions on the organization of the personnel in that year. The stated goal was "to ensure a constant assiduity among employees during work hours." One might have suspected that a meritocratic system would result, but the outcome of such unprecedented attention was yet another step system of advancement and continued ambiguity about departures from the civil-service model. The committee decreed that promotions would be attained "by seniority or

[21] Jean Courcelle-Seneuil, "Du recrutement et de l'avancement des fonctionnaives," Journal des économistes, May 1874.

[22] Thuillier, Bureaucratie , pp. 298-327; Guy Thuillier and Jean Tulard, Histoire de l'administration française (Paris, 1984), pp. 41-71.

[23] On the creation of a pension plan, see Rapport , March 26, 1859, p. 4.

[24] AP, V 8 O , no. 665, deliberations of March 22, 1856; no. 877, deliberations of December 2, 1859; no. 668, deliberations of May 25, 1861.

merit" after a trial period (stage ) of two or three years.[25] Thus, even in its mood of hard-headedness, the managers of the PGC did not definitively renounce for its office workers the public servant's prerogative of being evaluated on the basis of age. Ultimately, the company labored empirically and unsystematically toward a more efficient use of its clerical labor force without having a dear conceptual framework in mind. Only when the personnel began to contest its dependent situation did management offer a reasoned and sustained defense of policies that broke with models of public administration.[26]

Managers gradually erected an apparatus of punishments and rewards, which they hoped would encourage clerks to work efficiently. The chief of the customer accounts department was a faithful advocate of careful surveillance and was allowed to employ ten agents to check the accuracy of his clerks' work. Although he found the inspectors' reports lacking in substance, he insisted that their investigations had "a great effectiveness from a moral point of view"—that is, they intimidated the clerks.[27] The director sought to make surveillance more effective by adding the sanction of fines. His table of punishments gave special weight to the offense of challenging authority. Verbal or physical attacks on superiors, or refusals to follow an order, were punishable by immediate suspension and possible dismissal. Inebriation on the job, negligence, and absences without permission brought fines of five francs for the first offense and ten for the second; the third offense resulted in suspension.[28]

Management hoped and expected that the most powerful impulse for dutiful work would come from the practice of rewarding clerks according to individual merit.[29] Disregarding the resolution of 1863 about seniority, the PGC came to promote employees up the step system of pay solely on the basis of personal performance. The director, who made all decisions on advancements, did so after consulting reports that did not even specify

[25] Ibid., no. 669, deliberations of July 3 and 14, 1863; no. 670, deliberations of December 18 and 30, 1863.

[26] The first official affirmation of purely meritocratic evaluations that I have found is the executive directive of May 19, 1892: ibid., no. 1081, ordre de service no. 352. This policy had been in effect for many decades before the directive, but there had been no occasion to state it explicitly.

[27] Ibid., no. 90, report of Dufourg to chief of customer accounts department, January 15, 1898. In 1859 the post of inspecteur de comptabilité had been created, and to intimidate the employees further, his title had been upgraded to directeur de comptabilité. Ibid., "Procès-verbaux du conseil d'administration, 21 avril 1859."

[28] Ibid., no. 148, "Règlement sur les peines encourues par les agents attachès au service des sections."

[29] Ibid., no. 665, deliberations of November 8, 1856.

when the candidate had received his last raise. Management also used the retirement plan and bonuses as carrots. Gas clerks did not contribute to a pension fund, so the company proclaimed the benefits to be an earned privilege rather than a right. It also set aside 1 percent of profits for clerks' year-end bonuses. Though most clerks did receive a bonus, the director insisted that they had no inevitable right to one. Indeed, one unfortunate bookkeeper was deprived of a bonus, despite glowing reports from his superiors, because of an isolated incident of backtalk.[30] The PGC's executives hoped that performance-based rewards would raise standards of industriousness above those in the civil service. Thus office chiefs expected the staff to draft responses to customers' inquiries within a week and expedite them within two more days. Such promptness was often realized even though the ministries took two months for the same operation.[31] Nonetheless, the PGC largely failed to obtain the levels of diligence it had taken as its goal in 1863. The reasons for failure were numerous: the company's neglect to follow through on its announced sanctions, managers' tolerance for violations of rules, the imperfections in the sanctioning system, and the failure of clerks to exert themselves regardless of the penalties and rewards. In the end, evasive work practices were commonplace. The offices of the PGC were somewhat more tightly run than those of the state bureaucracy, but a basic transformation of office work had not occurred.

The bureaus of the PGC were not highly disciplined. As in the ministries, opportunities to dawdle and interrupt work were numerous—in-deed, taken for granted. The smoking break was as much a detriment to continuous work at the gas company as at the ministries. The formal rules against smoking were absolute but seemingly unenforceable; that is why they were reissued every few years. Moreover, office chiefs did not manage, or did not bother, to keep their subordinates from finding reasons to leave their desks, especially in the late afternoon. A directive of 1891 noted a "great number of employees have taken to congregating in the halls and staircases before 5:00 P.M. " That employees treated the official hours of work casually is clear. The order to be in the office at 9:00 A.M. sharp was reiterated as regularly as the provision against smoking.[32] The practice of signing the attendance sheet and then slipping out of the office

[30] Ibid., no. 723, deliberations of January 2, 1857; no. 156, "Finestre, Pierre."

[31] Ibid., no. 1081, ordre de service no. 80 (January 18, 1860); Thuillier, Vie quotidienne , pp. 81-83. A direct comparison between work in the PGC and in the ministries is not fully appropriate because the levels of authority were so much more complex in the latter.

[32] AP, V 8 O , no. 1081, ordres de service nos. 27 (15 février 1873), 316, 327, 336, 441, 448.

for breakfast was common. The head of the payment bureau noted that the average lunch break was ten minutes longer than the mandated hour. Street peddlers entered the offices and showed their wares to clerks at their desks. Clerks scoffed at the efforts of one chief to impose a rule of silence on his personnel because no other office worked under such conditions.[33] A lighting inspector—said to be favored by his chief, a fellow Corsican—brought his children to the office, and they interfered with the work and stole office supplies. The chief did not correct the situation until the corporate director, informed in an anonymous letter, intervened.[34] If work pressures expanded beyond an acceptable limit, clerks could always absent themselves. During 1869 the thirty-three employees of the secretariat took 182 sick days and 177 excused leaves, an average of nearly eleven per agent.[35] A civil servant would probably have found the pace of work at the PGC more intense than in the state bureaucracy, but he would have recognized the subterfuges by which gas clerks imposed their own pace on their labors.

The PGC was notably unsuccessful in implementing effective means for supervising and disciplining its employees. In the early days of the firm the architecture of the offices was no more conducive to oversight than were the ministries. The creation of a new corporation from smaller gas companies did not result in the construction of new office facilities at once. Employees took up their posts in the headquarters of one of the merging firms, and expansion took place haphazardly into rented spaces in nearby buildings. Even the small secretariat had to operate from three different sites, one separated from the others by two floors. Obstacles to supervision probably provoked the decision to construct a new headquarters in 1863, a year when efficiency in the bureaus was much on the minds of decision makers. The architects of the building, designated for the rue Condorcet (ninth arrondissement), designed sizable rooms with raised, glass-enclosed offices at the ends for the chiefs. No columns or alcoves obstructed the view from that cubicle. The space made available to the billing bureau was large enough for 150 clerks to function in sight of the chief and for another hundred to work in view of the assistant chief.[36] At

[33] Ibid., ordres de service nos. 120, 4 (30 décembre 1871), 303; no. 153, report of Dufourg to director, November 16, 1892; L'Echo du gaz: Organe de l'Union syndicale des employés de la Compagnie parisienne du gaz, no. 176 (August 1, 1904): 2.

[34] AP, V 8 O , no. 162, report of inspectors of fifth section to director, May 26, 1894.

[35] Ibid., no. 753, "Secretariat. Contrô1e des feuilles de presence."

[36] Ibid., no. 1598, "Hôtel de la Compagnie," no. 753, "Secretariat"; Rapport , March 21, 1863, p. 12; March 29, 1867, p. 24.

least the supervisors now had the technology of surveillance, and they received it about the time that ministries were taking steps to bring more order to their offices. But the PGC's headquarters proved too small for the growth that came with the customer-oriented programs of the late 1880s and 1890s. By the mid-1890s many clerks were again working beyond the view of their superiors, whose anxiety about surveillance was again on the rise.[37]

Management's sanctioning powers proved, if not empty, then at least unimposing. Soon after unveiling his table of fines, the director effectively renounced its use by stating that fines were "difficult to apply" and expressing his preference for positive sanctions.[38] The model of the civil service, which imposed fines on active agents (like letter carriers) but not on office clerks, prevailed at the PGC. The uniformed personnel, working beyond the supervision of the chief and in direct contact with customers, had to feel the weight of corporate rules, and it did. More than a fifth of the meter readers could expect to pay a fine each year.[39] Yet the bookkeeper at the PGC had no more to fear from fines than did the fonctionnaire. Nor did the gas company use dismissals with a heavier hand than did the state. In both cases, final warnings and ultimate warnings preceded a firing, which was often obviated through an act of indulgence. The rehiring of cashiered clerks after proper apologies and vows of good behavior was not unknown in either bureaucracy.[40]

However much gas managers came to insist on promotions solely on the basis of individual performance in the face of protests against this mode of advancement, the carrot-and-stick approach did not work nearly as well as they had hoped. This failure was partly the result of the way in which decisions on raises were made. As we have seen, the company pursued the strictest centralization in this area, with the consequence that managers most removed from a clerk's daily performance made the decision. The director had to consider hundreds of cases at a time and had only the terse reports from supervisors to guide him.[41] Employees believed—

[37] AP, V 8 O , no. 90, report of January 15, 1898.

[38] Ibid., no. 665, deliberations of November 8, 1856.

[39] Ibid., no. 153, "Revendications des contrô1eurs de compteurs." Some meter readers were made to pay (at least in part) for the gas lost in leaks they failed to detect in customers' homes. See no. 751, "Affaire Faure-Beaulieu."

[40] Thuillier, Bureaucratie , p. 407. Leaving work without permission was a ground for dismissal at the PGC; still, three clerks at the gas-main office were caught red-handed and merely given light fines (though also stiff warnings not to repeat the offense). See AP, V 8 O , no. 767, report of Bruley to Lependry, June 5, 1872.

[41] See chapter 4.

with some justice—that the decisions bore little relation to the degree to which they applied themselves on the job. Another reason for the failure of rewards to stimulate zeal was cultural: many employees were simply willing to forgo some of the rewards of pleasing their superiors, and accepted the penalties for not doing so, in defense of their work culture. These employees rejected for themselves the role of a proletariat of the office.

Though the PGC had trouble creating a committed and pliant office staff, the company was by no means an innovator in restructuring the work force to increase its malleability. The gas company was even less advanced than the ministries in introducing office machinery. From 1890 the civil service faced the challenge of integrating the typewriter into its work routines; the PGC virtually ignored the innovation. In 1891 the company possessed just one machine; even in 1902, out of three thousand employees, there were only two typist-stenographers.[42] The company used no keyboard adding machines even though it employed hundreds of clerks who calculated bills, added columns of figures, and verified totals. Perhaps one of the reasons for the PGC's technological conservatism as far as the office was concerned was that it retained the ideal of unitary recruitment even longer than did the ministries. The company expected any of its routine clerks in the customer accounts department to be capable of rising to subchief and therefore wanted them to be able to perform all types of work done in the bureau. As late as 1901, an executive order lumped all the employees except bill collectors into one category and subjected applicants to a uniform examination consisting of dictation, letter composition (rédaction ), and numerical computations. Of course, only a small minority of the positions within the PGC required proficiency in all three areas.[43] Adherence to unitary recruitment was a sign that management thought in terms of careers, not routinized tasks.

Similarly, the PGC did not lead the way in creating a cadre of female clerks. Gas companies in Germany had discovered the cheapness and docility of female clerks in the 1880s. Even the French state had reassessed its opposition to hiring women. The postal service began to use female clerks for bureaus in large cities by the 1890s. The PGC, however, hired not one female for its office jobs in its fifty-year history. The successor gas

[42] AP, V 8 O , no. 162, "Secrétariat—Personnel"; no. 688, deliberations of March 28, 1891.

[43] Ibid., no. 163, ordre de service no. 669 (November 16, 1901). Even meter readers had to take this examination. See "Aux contrô1eurs de compteurs," L'Echo du gaz, no. 176 (August 1, 1904): 3. Margery Davies, Woman's Place , p. 30, argues that in America new occupational titles based on functional specialization were added to the office. This did not happen at the PGC.

company apparently inherited the inhibition, for it did not even allow the labor shortages of World War I to bring females into the office. The executive council of the Société du gaz de Paris briefly considered experimenting with the departure in 1915, but nothing came of the proposal.[44] The PGC was content to deal with a male clerical force through the traditional means of cajoling and confronting.

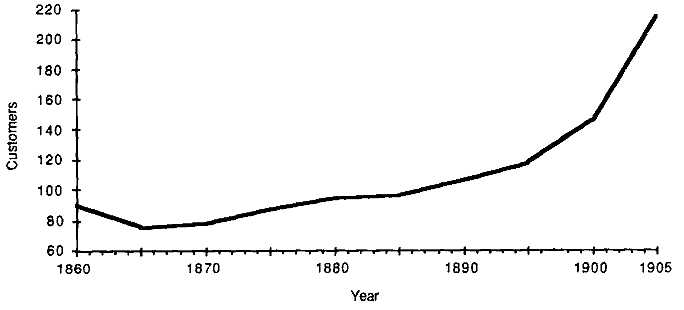

By all available measures, the PGC did not succeed in intensifying office work notably by those traditional means. To quantify the changes in work pace, it is useful to examine the number of employees relative to the number of gas customers. That ratio, more than any other variable, determined the amount of paperwork the personnel had to handle or the number of meters they had to read. Figure 11 shows that this index of productivity rose, but quite slowly, until the mid-1880s. The ratio of clerks to customers was only 8 percent higher in 1885 than in 1860 even though the number of customers had multiplied fivefold. The company, for all its parsimony, had hired enough clerks so that the burdens of office work had not become decidedly more oppressive. Indeed, office productivity seems to have had a slump during the 1860s, which probably prompted the managers' pointed concern about the office routine in 1863. The index rose dramatically only in the last decade of the century, in response to the democratization of the clientele. Examining the ratios specifically for the billing agents, whose work was particularly sensitive to the size of the customer base, reinforces the general picture. The number of gas users per billing agent was actually lower in 1884 (900) than in 1858 (973), but it rose considerably by 1902 (1,080), after the company had succeeded in expanding the residential market.[45] Thus, this quantitative evaluation confirms the earlier qualitative assessment that the PGC did not take resolute steps to debase office tasks. A more demanding pace of work seems not to have been a policy that the firm pursued for its own sake; it was the offshoot of the quest for a wider customer base.

The escalating burdens of clerical work at the end of the century may not have cut too deeply into the clerks' relaxed routines. Employees seem to have adjusted as much by adding to their hours as by quickening their pace. Comments and complaints about overtime work began to appear after 1890. The only mention of the practice before then had been in re-

[44] E. Brylinski, L'Electricité à Paris et à Berlin (Paris, 1898), p. 16; Susan Bachrach, "The Feminization of the French Postal Service, 1750-1914" (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1981); AP, V 8 O , no. 1634, deliberations of June 1, 1915.

[45] For evidence of rising complaints about overwork in the 1890s, see AP, V 8 O , no. 162, "Lettres et renseignements . . .., " letter of Appelle to director (n.d.). On the steps the PGC took to attract more customers after 1886, see chapter 4.

Fig. 11. Number of Customers per Employee.

From AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 153, 162, 665, 1294.

gard to special annual tasks for which the company recruited volunteers and paid bonuses.[46] Resort to overtime work suggests a white-collar labor force that refused to use every moment productively and was left to complete its work quota at a self-determined pace. Even so, it is easy to believe that the rising pressures on the job antagonized employees.

In the end, this large private corporation did not break decisively with the mode of white-collar work long found in the French civil service. Though there were nuanced differences, the employees of the PGC were not especially more disciplined than those at the ministries. The PGC failed to take effective steps to restructure the personnel in such a way as to give management more leverage. Conscious1y, and often unconsciously managers accepted the work routines of civil servants as normative even when they occasionally announced an assault on lax ways. The engineers simply did not apply themselves to regimenting the clerical work force with the same resolve they accorded manual workers. In neither case were there overwhelming financial pressures to do so, but the matter was even less pressing as far as white-collar employees were concerned. The company spent only 0.2 centimes on each cubic meter of gas sold (at thirty centimes) for accounting.[47] There was no real need to rationalize; it would not have made a difference. Nor did the engineers seem to have the same moral intensity about controlling clerks as they had for the manual per-

[46] Ibid., no. 153, "Rapport à MM. les administrateurs sur le fonctionnement actuel du bureau des recettes . . ." Previously, assistant office heads had had to stay late and handle unfinished work. See no. 90, report of Dufourg to Ymont, December 2, 1882.

[47] Ibid., no. 1016, "Comptes d'exploitation par année."

sonnel. Haphazardly the PGC created out of its unsystematic attempts at rationalization a mixture of traditional and innovative methods that may well have redoubled the employees' resentment. Enough of the old survived to provide the gas clerks with a sense of being rooted in familiar ways. Yet the firm's halting quest for a productive work pace and especially its use of discretionary authority to reward individual performance were not part of those ways. Clerks never accepted the legitimacy of the innovations.

The employees took advantage of their superiors' ambivalence to perpetuate an evasive work culture. They rejected for themselves a professional pride that might have led to the assiduousness that engineers displayed. The lighting inspectors are a good test case for the claim. On the one hand, they were more or less typical, in terms of social and educational background, of gas clerks. On the other hand, the company gave their behavior as much scrutiny as it did any category of employee and should have fashioned a pliant corps of agents if it was going to do so at all. But it did not. Albert Arrieu, an inspector hired in 1888, incurred twenty-two fines (of three or five francs each) between then and 1892. Louis Bray received twelve punishments in as many years, including several for leaving his job to sit in a pub, one for responding angrily to a superior in the presence of other clerks, and one for neglecting to take care of a customer's request. Emile Delsol accumulated twenty fines in two years, most of them for arriving late or missing work entirely. His supervisor explained that Delsol, "living alone, could not wake up in the morning despite trying several different types of alarms." None of these records was unusual. In fact, only Delsol was ultimately fired for his poor conduct. Arrieu was promoted to secretary of his lighting section, a sedentary post that inspectors coveted, and Bray became a supervisor (inspecteurcontrô1eur ) of other inspectors.[48] Obviously, the PGC's standards were not exacting.

On average, an inspector received 1.7 fines a year. Some agents had perfect records, but they were few. Only eight in the sample of ninety-seven inspectors went three years without a punishment. By contrast, a quarter of the agents angered management enough to incur a suspension, a severe sanction that signified extreme displeasure with the clerk. The distribution of violations holds a mirror to inspectors' attitudes toward their work and to their degree of commitment to it. The picture that emerges from table 10 is of a work culture characterized by petty evasion of rules. Neglect of company business, deception, and avoidance of work

[48] Ibid., nos. 164-173, "Livres du personnel."

Table 10. Abuses for Which Inspectors Were Fined | |||

No. | % | ||

Neglect of duty | 144 | 42.1 | |

Carelessness | 75 | 21.9 | |

Evading work routine | 40 | 11.7 | |

Tardiness | 39 | 11.4 | |

Willful deception | 17 | 4.9 | |

Challenging authority | 15 | 4.4 | |

Failure to exercise authority | 8 | 2.3 | |

Drunkenness on the job | 4 | 1.2 | |

Total | 342 | 99.9 | |

Source: AP, V 8 O1 , nos. 164-173, livres du personnel. | |||

accounted for nearly 60 percent of the fines. The average clerk in the sample was charged with one of these offenses at least once a year (with routine violations presumably going undetected). Unintended error, though not a negligible problem, was a good deal less common than willful disregard of regulations. Drinking on the job, however, was not a serious difficulty, nor was the offense that plagued Delsol. Significantly, the records on fines do not point to a cadre of employees chafing under the exercise of authority by their superiors. In fact, employees rarely challenged such authority. Likewise, inspectors rarely failed to exercise control over their own subordinates, the lamplighters and greasemen. The outlook of the inspectors was not so much frondeur as fainéant.

A reflection of the same work culture arises from the dossiers of eighty-three clerks in the payment bureau of the customer account department. Their job, being more coordinated and supervised, offered fewer opportunities for open evasion. Nonetheless, the bureau chief did not find an optimal situation. Nineteen (23 percent) of his clerks consistently ranked as "excellent" or "very good" workers. Fifteen others were "good" servants of the gas company but had room for improvement. The majority of payment clerks (59 percent) were not "good" servants in the eyes of their chief. Their problems extended from "frequent absences" to having a "violent character." Twelve percent of the office staff was in danger of being dismissed or receiving a serious sanction. As in the case of the lighting inspectors, careless work, lack of precision in executing routine tasks, and absences from one's assigned place comprised the core of the problem.[49]

[49] Ibid., no. 153, "Etat des appointements alloués aux employés ayant plus de 2 ans de service."

In the face of such lackadaisical work habits, a few office heads took their revenge. They filed personnel reports that eschewed the usual bland comments and were intended to retard promotions. The chief of the customer accounts department during the 1890s, confronted with a rising work load and the displacement of clerks to desks outside a central bureau that had grown too small, tried increased surveillance. In 1895 he requested and received permission to create a "verification detachment" that would intimidate his subordinates. The chief's position was that "employees must never believe for a moment that they are lightly supervised." The formation of such a corps may well explain why his underlings hated him with a special passion.[50] More typical was the head of the by-products division, Audouin, who admitted to putting up with "disorder" in his office. Even when he arrived at the point of finding the disorder "intolerable," he still did not call for dismissing one bookkeeper who left work without permission.[51] Managers were simply not conscientious about disciplining the commissioned personnel. Such leniency, contrasting sharply with managers' vigilance regarding wage earners, encouraged clerks to develop a different sort of identity.