Bringing Manhattan Closer to the Suburbs with Buses

Despite the Depression, the region's motor vehicle traffic continued to increase throughout the 1930s, and the Port Authority and its fellow roadbuilders added additional highways and river crossings. The Port Authority's main contribution was the Lincoln Tunnel, opened in 1937, taking traffic from New Jersey under the Hudson River directly into mid-Manhattan. And as the highway alliance built, still more travelers journeyed into New York City by motor vehicle, and Manhattan's CBD became choked with automobiles, trucks, and buses.[56] Expanding traffic had a more positive impact on the Port Authority than on city streets. The port agency's toll income increased, its surpluses grew, and by the early 1940s a once-struggling rail freight planner had become a wealthy and dynamic bridge and tunnel entrepreneur.[57]

Close study of vehicular patterns revealed, however, that traffic expansion on the authority's crossings was being retarded by financial difficulties in

[54] "Port Authority Birthday," editorial, New York Times, April 30, 1946. For a selection of other comments on the bridge and the authority, see PNYA, 25th Anniversary (New York: 1946), a booklet of articles and editorials.

[55] Bergen Evening Record, October 30, 1953. One of Lowe's fellow Port Authority commissioners was John Borg, long-time publisher of the Record and an early advocate of the 178th Street bridge.

Sometimes those friendly editors relied so fully on the authority's press writers that they seemed to confuse the Port Authority's activities and their own. Thus the Journal of Commerce, in a full page review of the agency's "majestic" bridge and other accomplishments, waxed warmly on the authority's landmark financing efforts, which were notable because "our first issues" were much larger than any previous public revenue-bond issue. The Journal 's writer then commented, no doubt to the surprise of the newspaper's stockholders, that "any surplus from our operations ultimately belongs to the States of New Jersey and New York," and concluded with the sober admission that "we cannot turn to the taxpayers for reimbursement of losses." "New York Port Authority Traces 25 Years of Progress: It Has Accomplished Much in Many Fields of Endeavor," Journal of Commerce, May 22, 1946; emphasis added.

[56] For example, trans-Hudson vehicular traffic rose from 16.9 million vehicles in 1934 to 30.6 million in 1941. Under the impact of gasoline rationing and "pleasure-driving" bans during World War II, traffic then dropped sharply, hitting a low point of 21.9 million in 1943 before rising again in 1944, reaching 27.2 million that year. See Port of New York Authority, Fourteenth Annual Report (New York: March 18, 1935), pp. 34, 36; Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941 (New York: March 31, 1942), p. 15; Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943 (New York: April 1944), pp. 1–2, 7–8; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944 (New York: November 15, 1945), pp. 2, 6–7.

[57] Investment in facilities had risen from $38 million in 1928 to $238 million in 1944. Net annual revenues (after payment of debt service), which had been a deficit figure until acquisition of the Holland Tunnel in 1931, rose from $2,854,000 in 1934 to $6,424,000 in 1940 and $8,740,000 in 1941. Even during the war, annual net income never fell below the 1940 figure. See Port of New York Authority, Eighth Annual Report, p. 82; Fourteenth Annual Report, p. 55; Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 14; Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, p. 33; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, p. 44.

New Jersey. The state highway department, supported by tax dollars rather than tolls, had managed to construct the Pulaski Skyway and related roads bringing traffic to the Holland Tunnel, and two major highways joining with the George Washington Bridge. But its efforts to build other highway projects had been curtailed by limited tax dollars. Conceivably the Port Authority might have allocated some of its toll profits in order to assist in financing related highway networks—thus adding, in the long run, to its own toll revenues while accelerating suburban mobility. But the authority did not embark on this course. As Bard comments, reflecting the views of the agency's officials at the time, "it is too much to expect that a bridge or tunnel, as a toll gate, should finance the construction of miles of highway." Much of the total cost "must be shouldered by the states and localities," so that in a "general program of highway expansion . . . toll collection is merely an auxiliary method of paying for the costs."[58]

This modest view of the toll agency's "auxiliary" role in regional highway development was not without advantages to the Port Authority, of course. While state and local agencies struggled, in these lean years, to attract enough tax dollars to meet growing highway needs, authority officials could turn their thoughts and surpluses to other challenges. The original Port Compact hardly envisioned a Port Authority devoted solely to subsidizing highway construction, and as available funds grew in the early 1940s authority officials sought new ways to shape the "development of the port" and to enhance the influence of the port's chief advocate.[59] This was a time for expansion.[60]

[58] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 213–214. "The bridges and tunnels have been built and they are in operation," the Port Authority commented in 1940, but "the situation which now confronts the States, and particularly New Jersey, is that . . . a comprehensive system of arterial roads to feed these facilities . . . has yet to be constructed." Port of New York Authority, "Report Submitted to the New Jersey Joint Legislative Committee Appointed Pursuant to the Senate Concurrent Resolution Introduced March 11, 1940" (New York: June 1940), p. 32; emphasis added. See also pp. 30–32, 63–64; Port Authority, Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 11; and Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, letter of transmittal (pp. 6–7), and p. 16.

This distinction also underlay the reaction of a long-time authority official when reading a draft of this chapter. "The Port Authority should not be characterized as a highway-building agency," he protested; "in the field of vehicular transportation, it is only a bridge-and-tunnel agency."

[59] In the 1921 compact, the two states agreed to "faithful co-operation in the future planning and development of the port of New York" (Article I), and created the Port Authority, "with full power and authority to purchase, construct, lease and/or operate any terminal or transportation facility" (Article VI). Thus the authority's officials could roam across this wide field, although they were limited by the need to ensure a long-term income flow that exceeded costs. (The compact is reprinted in its entirety in Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 329–339.)

[60] In their search for new tasks, the authority's leaders were motivated not only by the challenges of the postwar era they saw ahead of them, but also by a look behind—at the host of automobile users, truck drivers, and bus companies pursuing them, demanding lower tolls on Port Authority bridges and tunnels. The authority had already faced one legislative inquiry on this issue, in 1940, and successfully defended its view that the existing (50-cent) toll level must be maintained in order to provide funds for "future improvements" in the port district. But its officials realized that pressure to reduce toll rates would become irresistible if the agency did not soon commit its growing surpluses to new projects. On the 1940 inquiry, see Port Authority, "Report Submitted to the New Jersey Joint Legislative Committee . . . " (the quotation above is on p. 40), and Port Authority, Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 11. On the pressures confronting the Port Authority in the mid-1940s and the views of its officials at that time, see Herbert Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," in Harold Stein, ed., Public Administration and Policy Development (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1952), especially pp. 182–183.

So it was that by 1943 the Port Authority had cast an admiring eye upon the problems confronting the region in the field of air transport, and after a lengthy series of negotiations the agency assumed control of the region's three major airports in 1947–1948. Meanwhile, in 1944 and 1945, it took over a marine terminal facility in Brooklyn and began a study of port terminals in Newark, leading to a lease signed in 1947 providing for authority control, rehabilitation, and operation of Port Newark.[61]

In the long run, Port Authority operation of these leased facilities might prove of great benefit to the port's commerce and to the authority's own reputation.[62] But some greater initiative was needed—something the authority could create itself. As the war drew toward a close, the agency expanded its planning staff, completed a careful analysis of traffic patterns, and announced that it was prepared to construct "the world's largest bus terminal" to help relieve the "intolerable midtown Manhattan traffic congestion."[63]

The need for such a terminal seemed evident to the region's transportation planners. By the early 1940s, the influx of bus traffic from west of the Hudson—traveling on Port Authority facilities—had become an important factor in traffic congestion in the CBD. Most of the buses brought New Jersey passengers through the Lincoln Tunnel and deposited them at eight separate private bus terminals scattered between 34th and 51st Streets. By 1944, 1,500 buses each day crossed the Hudson bound for mid-Manhattan and most of them were caught regularly in heavy midtown traffic bottlenecks. It was anticipated that a union terminal near the Lincoln Tunnel would draw off most of this traffic, eliminating more than two million miles of bus travel in midtown Manhattan annually—and thus providing traffic relief equivalent to two or three additional crosstown streets.

In fact, a bus terminal of this kind had been proposed earlier by the bus companies and by New York City's own transportation planners. But the bus lines, each wary of losing the competitive advantage of its existing midtown station, could not agree on joint terminal operations. And the city administration, its staff and financial resources stretched thin by other service demands, had made no progress. New York's mayor was therefore glad to be able to turn to the authority's able planners. With his encouragement, the Port Authority developed a proposal in 1944 for a major terminal (between 40th and 41st Streets, and 8th and 9th Avenues) that would replace individual bus termi-

[61] The Port Authority's growing interest in air transport is indicated in its annual reports for 1942–1945, and its negotiations and acceptance of the airport and harbor facilities are summarized in its reports in 1944–47. See Port Authority, Twenty-Second Annual Report: 1942, letter of transmittal (p. 4); Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, pp. 14–15; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, pp. 11–13, 20–22; Twenty-Fifth Annual Report: 1945, (New York: July 1, 1946), pp. 8–9, 18–23; Twenty-Sixth Annual Report: 1946, (New York: November 1, 1947), pp. 2–19; Twenty-Seventh Annual Report: 1947, (New York: November 1, 1948), pp. 6–7, 24–25, 30.

On the airport negotiations, see also the perceptive study by Kaufman ("Gotham in the Air Age," 143–197), analyzing the conflicts between Robert Moses, the Port Authority, New York City's administration, and other participants. As Kaufman's analysis indicates, the ability of the Port Authority to allocate funds to rehabilitate and operate the airports was a crucial advantage as the authority negotiated to take over these facilities from the financially strapped municipalities.

[62] Actually, ownership of the Brooklyn grain terminal was transferred by New York State to the PNYA; Port Newark and the three airports were turned over to the authority on long-term leases.

[63] Port Authority, Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, p. 17.

nals. The authority would not only plan and design, but also finance, construct, and operate the massive new terminal.[64]

The proposal attracted warm support from most of the bus companies, business leaders, the news media and some government officials. But Robert Moses was not so pleased. Wary of the Port Authority's expansionism within New York City, as its bus terminal and airport excursions brought the bistate agency further into his territorial domain, Moses thrust back. Allying himself with the Greyhound bus company (which did not want to be included in the union terminal), Moses donned his hat as a member of the City Planning Commission, persuaded a majority of fellow commissioners to join him in opposing a crucial element of the Port Authority plan, and for two years blocked the terminal. It was, as Herbert Kaufman noted, a "grim and bitter battle."[65]

As midtown bus traffic expanded to more than 2,500 interstate vehicles per day, and complaints of traffic congestion grew, the port agency pressed for approval of "this great public improvement" to relieve an "intolerable" traffic problem costing Manhattan business "an estimated million dollars a day." Finally, in 1947, the city's Board of Estimate endorsed the Port Authority plan, handing Moses one of his few defeats. Revenue bonds to finance the Port Authority Bus Terminal were sold in 1948, and the terminal was opened in December 1950.[66]

The impact of the bus terminal project was manifold. The new terminal reduced travel time for bus passengers by between six and thirty minutes. Bus travel from Bergen, Essex, and other northern New Jersey counties became more attractive, and interstate bus routes were extended more deeply into

[64] see Ibid., pp. 17–19, and Port Authority, Twenty-Fifth Annual Report: 1945, pp. 9–14. According to one Port Authority official involved in the negotiations, New York City's ability to undertake the project itself was weakened by the fact that its staff included "planners but not builders," while the authority, having both, could draw upon its own personnel, propose a feasible plan, and carry it out as soon as the proposal was approved.

During the mid-1940s, the authority also began constructing two union truck terminals authorized before the war.

[65] Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," p. 177.

[66] A complex situation permitted Moses to block the PNYA proposal. The authority had concluded that the new bus terminal would not be successful in consolidating terminal traffic—and thus in reducing traffic congestion and in making the terminal self-supporting in the long run—if any of the bus companies were permitted to build or enlarge existing individual terminals east of Eighth Avenue, an area more centrally located for access to offices and shopping. Therefore, the authority sought approval by the Planning Commission and the Board of Estimate of resolutions to prohibit any bus companies from future bus terminal development in the more central area. Without such action, the authority argued, it could not sell revenue bonds for the terminal; and so construction was deferred pending action by the City. But the Greyhound bus company already had a terminal in the "forbidden area" that it wanted to expand. Therefore Moses supported the Grey-hound application to be exempted from the proposed resolution, using that as his vehicle to persuade the Planning Commission to oppose the blanket prohibition demanded by the Port Authority. For details on the bus terminal case, see the authority's annual reports for 1944 (pp. 17–19), 1945 (pp. 9–14), 1946 (pp. 19–24), 1949 (pp. 76–80), and 1950 (pp. 99–102). The quotations in the text are found on pp. 19–20 of the 1946 report. Commissioner Moses's views are stated in part in his letter of October 16, 1945 to Chairman Howard Cullman of the Port Authority. In that letter, he concluded that the treatment of Greyhound was "grossly unfair" because its officials were "merely proposing to extend a non-conforming use authorized by the courts," and because the bus company had also agreed to spending $300,000 on traffic improvements related to its proposed terminal expansion. (Letter made available to the authors by Mr. Moses.)

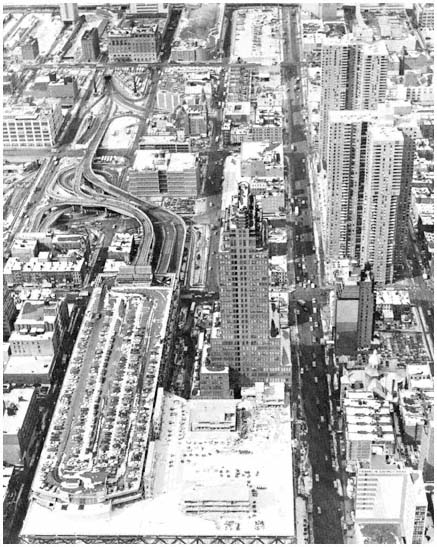

The Port Authority Bus Terminal in mid-Manhattan

is the terminus of commuter bus lines serving

residents of all the counties in the region west

of the Hudson River. The terminal is directly

connected to the Port Authority's Lincoln Tunnel,

as can be seen in the upper left-hand corner of the photo.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

suburban areas. By 1952, about 5,000 buses were using the terminal each day, carrying 130,000 passengers to and from mid-Manhattan, and the number continued to rise during the next decade. Meanwhile, although the new bus terminal was hardly decisive, the reduced travel time it provided was one

more factor tipping the scales against the railroads, as passenger traffic crossing the Hudson by rail declined steadily in the 1950s.[67]

For the Port Authority as for bus travelers, the bus terminal venture was highly successful. The agency was widely praised for providing this "greatly needed" facility, thus aiding travelers and business in the region.[68] The commitment of $24 million to construct the terminal helped absorb the agency's growing reserves. As financial allocations to airports, marine facilities, and truck terminals were added in the late 1940s, the demand for toll reductions faded as an active rallying cry. Yet the authority remained alert to the need to emphasize that its reserves would always be hard-pressed to meet the region's growing demands for self-supporting facilities. "The task of keeping pace," the agency proclaimed in 1950, "is a continuing one." Projects already underway and those still on the drawing board demanded that the authority maintain a "sound financial position," the agency warned in 1953, for "growing requirements . . . may call for an expenditure of some $550,000,000 of capital funds in the next ten years."[69]

In the language of the Hudson Dispatch, the Port Authority had become a "giant operator,"[70] and the efforts of the 1940s would, its officials hoped, be only a prelude to more vigorous activities in the decades ahead.

From the perspective of our more general interests, these activities illustrate a number of important themes: leaders of large and "profitable" public enterprises have substantial discretion in choosing programs and timing their projects; these leaders' views of the proper goals of their agencies are crucial in determining how they respond to "market demand" and how they shape it; public authorities have great advantages, in comparison with local general-purpose governments, in their ability to concentrate resources on specific developmental projects; conflicts in priorities and territorial influence among public officials combine with public demand in shaping government action; new public projects, in this case the Lincoln Tunnel and then the bus terminal, have impacts that extend outward, affecting transportation and residential patterns, and then molding the need and opportunity for future development projects.

[67] Port of New York Authority, Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952 (New York: 1953), p. 36; Port of New York Authority, Metropolitan Transportation: 1980 (New York: 1963), Chapter 20.

[68] The quotation is from "Port Authority Report," editorial, New York Times, August 13, 1946; cf. the laudatory comments on the bus terminal and its benefits in "The Port Authority at 30," editorial, New York Times, April 30, 1951, and "New York Port Authority's 30 Years of Achievement," editorial, Courier-Post (Camden, N.J.), May 1, 1951. A decade after the terminal opened, increased traffic led the authority to undertake a $30 million expansion of the terminal, which it said would save five minutes or more in commuting time. The new plan generated another round of media applause. The article in the Sunday News placed particular emphasis on the nexus between improvements in transport terminals and suburban growth. "Over the next six months, more than 91,000 commuters from Bergen and Passaic, Hudson, Essex, Union Counties and points west will be 'moved closer' to New York," the article announced. "Real estate men, advertising suburban dream houses as '30 minutes from New York,' will be able to claim 25 minutes, or 20." Douglas Sefton, "Eureka! N.J. Commuters Nearing a Utopian State," Sunday News, March 25, 1962.

[69] Port Authority, Twenty-Ninth Annual Report: 1949, p. 116; Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952, p. 67.

[70] "Port Authority in 25 Years Becomes Giant Operator," editorial, Hudson Dispatch, April 30, 1946.