2

Berkeley in the 1940s

The Place and How I Came to Be There

When I came back to Berkeley in the fall of 1944 the country was still at war, but the city had not yet taken up arms against the rest of the nation nor had it seen fit to adopt its own foreign policy. These adventures lay a couple of decades in the future. Berkeley was then, as when I lived there in the late thirties, a college and commuter town, where passionate commitments were more intellectual and personal than political. It was sometimes called a city of eccentric professors and of little old ladies in tennis shoes, up-ended in the garden.

Gardens large and small, public and private, were omnipresent, and surely they defined the character of the place as well as anything did. Still in existence, they no longer define. Then almost every house in the Berkeley hills had its private garden of shrubs and annuals, growing lushly in the mixed climate of sun and fog. Public ones included two splendid botanical gardens, the University Garden in Strawberry Canyon, behind the stadium, and the Regional Parks Botanic Garden in Tilden Park, just over the hills in Wildcat Canyon. One grew plants from all parts of the world, the other from every part of California. There was the fine, terraced Municipal Rose Garden in Codornices Park and the Salbach commercial garden high in the hills. Next door to Salbach my old library school teacher, Sidney B. Mitchell, tended his flower beds and wrote popular books about them, such as In a Sunset Garden . Ira Cross, professor of economics, hybridized chrysanthemums behind his tall house on Le Roy Avenue—a house built by

Rose Garden, Berkeley.

the architect Walter Steilberg on the ashes of the great Berkeley fire of 1923. My wife and I lived there many years later, as second owners.

A few words of nostalgia will not conceal—to those who know—the acute problems of university and town life or the toughness and combativeness of the inhabitants, including gardeners. Deer sometimes walked the streets of the hill districts and at night nipped the buds off rose bushes and devoured much else. On those streets to the east, bordering Tilden Regional Park, a sort of guerrilla war went on. Deer lived in the park by day and raided the town by night—as political activists were later accused of using the University as a staging area for attacks on the community. In one area a gang of three deer showed up every nightfall. Nothing could be done to stop the devastation, it seemed, until word got to James B. Roof, supervisor of the botanic garden in the Park, a man no less eccentric than any professor and no respecter of city or park regulations. Recruiting two friends and three shotguns, he lay in ambush one evening. The three deer appeared. The guns went off. Years later Roof told me that the first thing he heard, as blue smoke rose in the dusk, was a child cry-

ing: "Oh, they're shooting Bambi." The second sound was the voice of a housewife: "Did you get the sons-o-bitches?"

That was only an early skirmish; greater battles could be waged by the alliance of private and public gardeners. Some years later the director of all the regional parks was William Penn Mott, Jr., an ambitious man who was to become Ronald Reagan's director of the National Park Service. Mott decided to move that same Regional Parks Botanic Garden to a new site in East Oakland, and install in its place a pony-riding playground. One wonders, did he really think that botanic gardens were mobile, like some homes, and that he could pick one up and put it down elsewhere without mortal harm? The impulsive Jim Roof, who had spent twenty-five years creating the garden out of nothing on a couple of empty hillsides, might have taken the same shotgun to Mott. With uncharacteristic restraint he appealed to the private gardeners of Berkeley.

And it was they—a group that included a few professors of botany and physics, but mostly the embattled housewives of Berkeley—who fought a war with Mott, beat him down, and forced him to give up his plan. That little victory under their belt, this group of mostly amateurs organized itself into the California Native Plant Society and set out to save the native flora of California from bulldozers, developers, and the over-use of imported plants. From that small Berkeley beginning, the society has grown into a statewide group with active local chapters from Arcata to San Diego. And in imitation similar societies have sprung up in all the other western states. Some call this a nobler, a less self-serving, cause than other more strident ones.

Berkeley, of course, was not all gardens. Nor all hillsides. Social historians make much of differences between the hills and the flat lands to the west—perhaps too much. I lived years in both sections. In the thirties and forties we flatlanders felt no social distinction; the hills were handsomer and costlier, that was all, and we moved there when we could. Later a number of changes, including a new racial mixture brought on by war industry, had political repercussions. Even so, not everyone is a zoon politikon . In troubled times there were

thousands who lived in Berkeley and paid little attention to the squabbling city council, who never walked past People's Park, or witnessed a riot. Such has always been the case, I suspect. But agitators make a better story.

But this is not an account of what happened to Berkeley. Here I wish only to sketch a setting for the Press when I first knew it, to give some idea—if only a personal and impressionistic one—of the environment in which it lived and grew. Berkeley was then more of a commuter town than it is now, one of the bedrooms of San Francisco. Trains to The City, as it was called, ran every few minutes along Shattuck Avenue, a block from the Press building, loaded with blue- and white-collar workers and with those who took the day off for shopping or pleasure. Editor Harold Small said that the riders, from early to late morning, were in turn the works, the clerks, and the shirks. The trains were more visible than they are now and a more vital part of the community.

I don't know how it came about that Berkeley was also a town of churches and theological schools; many of the latter were clustered around a hill just north of the campus, sometimes known as Divinity Hill. In early days the city had its own local form of prohibition. By the forties this was gone, but a state law made it illegal to sell alcohol within a mile of the University; for a drink one had to travel south on Telegraph Avenue or west on University. As a result, perhaps, there were then no truly good restaurants in Berkeley, no Gourmet Ghetto. For reasons more social than alcoholic the streets were safe. One could walk across the campus at night without fear. And housewives, including the little old ladies in tennis shoes, were not afraid to shop on Telegraph Avenue in stores that no longer exist.

The chief fact about Berkeley was, of course, the University, then generally respected in town although sometimes resented for taking property off the tax rolls. And lest nostalgia imply too mild a picture, we may remember that all is not harmony and good will inside a university. There may be partial protection from the commercial and political world—or at least there used to be—but strife is common within. Faculty and business officers do not see eye to eye. Power

struggles convulse departments. Young teachers fight for tenure, older ones wage intellectual battles, sometimes against each other. There was the noted professor of history who had gathered, as some do, his coterie of loyal followers. Every noon master and acolytes sat around a large table at the Faculty Club, set apart from the ordinary run of academics. This little gathering was described by another professor as a sham giant surrounded by real pygmies. Intolerance there was, but no one invaded a professor's office or shouted him down at meetings.

The great expansion of the University came after the war, but slower change was going on in the early and middle forties. At that time Berkeley was still the center, the heart, the focus of greatness. The Southern Branch had become UCLA and moved to Westwood in 1929 and was on its way to claiming equality. Davis was an agricultural college, Riverside merely the Citrus Experiment Station, La Jolla the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Santa Barbara, not yet moved to Goleta, was trying to live down its normal-school beginnings. The only medical school was in San Francisco. Even so it was a great and widespread university if not yet the multiversity of Clark Kerr.

And the University Press? For the first forty years it had been little more than an academic committee with a secretary, sometimes called a manager, and with offices passed around from one University building to another. In 1933 it was grafted on to the University printing office, and in 1940 the combined organization moved into Sam Farquhar's handsome new building on Oxford Street, precisely between the campus to the east and the main Shattuck Avenue business district to the west. There it was when I visited in about 1940 and when I came to work in 1944.

The location now seems important. Although we never participated in municipal or local business affairs, we were slightly and subtly away from the academic center. Suppliers could come to us without bumping into classroom traffic. When we ate at the Faculty Club or called on a professor, we were almost visitors; we belonged and

did not belong. Later, with the new importance of the other campuses, that location, or a later one on the same street, was an essential part of our stance as an all-University and not a Berkeley operation. Later still, as part of the statewide president's office, we had little to do with Berkeley as a campus or with the Berkeley administration, even though faculty members, and the faculty as faculty, were central to our existence. A vital distinction but a hard one to explain.

And the location made clear to us—when we thought about it—that the Press had virtually nothing to do with students or with the University as a teaching institution. We printed no student publications, published no standard textbooks. Our dealings were with faculty members as scholarly authors. This lack of contact with the student world and our location in the town business district, blocks away from Telegraph Avenue, meant, two decades later, that the student wars scarcely impinged on our work or our daily lives. I remember one demonstration visible from our high windows. And once our low windows were broken.

After Clark Kerr's reorganization, when our statewide status was settled, we sometimes felt that we had the best of two worlds: the Press was an administrative department and at the same time its function was academic, subject to faculty wishes. Although it would never have done to play one against the other, the double character was sometimes useful.

But I get ahead of myself. Such matters come later.

Since I am an unavoidable part of this story—the cord on which it is strung, the glass through which it is seen—it may be useful to say something about how I came to be on hand, about the accidents that brought me to the Press. And to show how my peculiar traits were formed, insofar as they can be formed by experience. I was raised in two small towns on the Oregon side of the Columbia River. The first of these, Hood River, sits beside a small stream of the same name, whose lush, green valley, stretching to the south, was filled with apple and pear orchards, some of them—like that of my mother's uncle—planted on high rounded buttes. From some streets of the town one

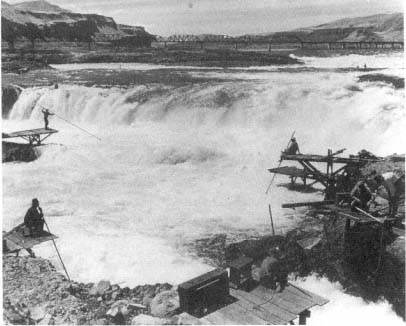

Celilo Falls, with Indians fishing. The falls no longer exist, having been

drowned by The Dalles dam. (Oregon Historical Society, #OrHi 86615)

could look south to the snowy volcanic summit of Mount Hood and north to an even higher peak, Mount Adams in Washington. Today the downtown district has changed almost not at all. And on a hillside above it still sits the first house—first home—that I can remember. With my grandparents we used to cross the Columbia on a miniature ferry to the village of Underwood, and from there go by horse and wagon up a dirt road to a part-time and unprofitable farm on the far side of Underwood Mountain.

The Dalles, not many miles to the east, was an old market and railroad town serving the farm country roundabout. On Saturdays stores stayed open until nine o'clock in the evening to gain trade from distant wheat farmers. Indians from Celilo—a few miles to the east and now lost under dam water—came to town that day and sat on curbs and in front of stores. No one bothered them.

The Dalles is set down in a splendid landscape just where the Cascade Mountains break off into dry eastern Oregon and on the banks of a magnificent river—more magnificent at that time, when dam waters had not yet drowned the great flat rocks and rapids that gave the place its French name. The town, unfortunately, could never match the setting. In the last century it had been a river port, the head of navigation, and a rowdy place that is said to have supported more than fifty saloons. Steamboats were long gone in my time and saloons had succumbed to prohibition, but vestiges of the old town survived, including a huge and abandoned old hotel, the Umatilla House, and a one-block-long Chinatown near the railroad tracks. But most of the place was ordinary enough, with wooden houses in midwestern style, as in other Oregon towns.

(Years later, during Editorial Committee meetings in the Press library, where I was dealing with some of the best scholarly minds in the world, there would sometimes come over me the feeling that I was out of place. Closing my eyes I wondered what sleight of hand, what wand of fortune had transported me from The Dalles, where I belonged, to the halls of Berkeley. It may be that others in the room also sometimes wondered at their presence there, but I always assumed that they belonged and knew they belonged, as I did not.)

Young people with literary or intellectual pretensions sometimes find it easy to look down on their bourgeois home towns. The Oregon writer, H. L. Davis—author of the prize novel Honey in the Horn (1935), who toward the end of his career lived near Berkeley, where I met him an only time—rechristened the town Gros Ventre in a bitter sketch published in H. L. Mencken's American Mercury, perhaps implying that the inhabitants were more than uncommonly greedy. For respectability, Davis thought. Before coming to The Dalles he lived in Antelope, a tiny sheep-country town in the southern part of the county. Antelope achieved fame of a sort a few years ago when the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh settled there with a large flock of followers. He must have fleeced them well; the federal government eventually confiscated his fifty Rolls-Royces. Before that there was a fine series of controversies; the Bhagwan, it was feared, might be seeking to take

over Wasco County; his disciples were said to have been responsible for a massive outbreak of salmonella food poisoning in The Dalles.

After high school I might have gone on to one of the Oregon universities, closer and more practical than others. Perhaps it was the snobbery of my surviving parent, my mother, as well as my own, of course—the poor looking down on those better off—that sent me instead to distant Stanford, where I managed by putting tuition charges on the cuff. Except for this and for travel back and forth, it was not then particularly expensive, although the coming of the Great Depression made everything desperate. But at Stanford, after a rather easy high school, I came up with a shock against the difficulty of competing with students from the better California schools, such as Lowell in San Francisco, and from eastern prep schools. They knew more than I did, had better work habits, and knew how to study, as I did not. It took most of a year to pull myself even. The son of my mother's employer failed to make it.

After spending most of a working life in Berkeley, so that Berkeley became a pervasive part of me, that Stanford interlude seems far away and unreal. But that is where and when were formed many of my intellectual tastes, including a fondness for French and Russian literature. And there I began to learn a few troublesome things about myself. Like others with humanistic interests, I had no use for a career in business—although later there was keen appreciation of the semibusiness nature of scholarly publishing. I cared for literature and learning, for books, but was repelled by the notion of teaching—and what else could one do with such tastes, especially in the depression world? Even then I must have perceived dimly that I was not cut out to be a research scholar, although fond of intellectual matters. Long years of graduate study, and a hand-to-mouth existence, had no appeal.

With that impractical and impossible education, I got my degree, went back to Oregon, and was fortunate in the grim depression year of 1933 to get work in a furniture store, where I kept accounts, collected bills, delivered furniture, and sometimes tried to sell it, learning that I was not a salesman. Perhaps those two years provided some-

thing essential. After the passive and irresponsible life of a student—and my own inability to see any acceptable line of work for the future—they did much to bring my feet down somewhere near the ground. I rather enjoyed the active life, turning down a chance to go back to Stanford as a teaching assistant, but had no thoughts about how it might be combined with intellectual tastes.

An accident got me away. In the last desperate depression year at Stanford, when all ways seemed closed ahead, I had taken the civil service examination for accounting clerk in state institutions, work I knew nothing about. More than two years later in Oregon came a form postcard telling of an open job near San Jose. It was no better than what I had in The Dalles, but it would get me out of a spot with no future. I drove down and took it. And was soon intensely bored with the routine, far deadlier than life in the furniture store. But meanwhile a librarian friend at The Dalles, Mabel Kluge,[1] had moved to Berkeley for further study, and it was she who suggested library school. She recommended me to the dean of the school, Sidney B. Mitchell, and helped me get a part-time job in the University library at $50 a month. It was a desperate sort of move, like so many others in the depression years. What else could one do with semi-intellectual talents and no training?

There was an amusing incident before I left San Jose. Again I took a civil service examination, the second of a series, this time for chief accountant at state institutions. With ignorance tempered by my old Stanford-learned knack for examinations, I somehow scored number one in the entire state on the written test. But when at the oral I foolishly admitted having applied to library school, my score was simply tossed out. By that time it was a kind of game, and I went from first to last.

Once before I had been shown the futility of examination scores. In my last year at Stanford I took a course from the celebrated Shakespeare teacher Margery Bailey but was frustrated when she let the

[1] As Mabel Jackson, she later headed the Library of Hawaii, the statewide system.

students lead the discussion; I had come to hear her. She must have seen the wrong kind of look on my face; one day she pointed a finger and told me to get out. At her office a day or two later she gave me a good chewing-out, probably deserved, for my supercilious attitude, allowed me a barely passing grade, and then advised me never to be a teacher: I was totally unfit for such work, she said. From her office it happened that I had to go to the Education Deparetment to get my score on a teaching aptitude test, taken in desperation, a test given to hundreds of students throughout the university. The man at the department checked the card file, gave me a strange look, and announced that I had come in number one. Even then, enjoying the ironical twist, I thought that Marge Bailey was probably right and the test wrong.

A student again at Berkeley and a few years older than most others, I found the competition in that special kind of school vastly easier than it had been at Stanford. The degree came and then a regular job in the accessions department of the University library itself, the beginning of a career that I could handle. At that time, when the library profession was dominated by women, it was sometimes helpful to be a man; we were scarce, and there were those who wanted to balance the sexes in the profession. But there could be problems, as when I applied for a temporary vacation job at the Berkeley Public Library. She would really like to give me work, said the distinguished librarian, but there was no men's rest room in the building. Amused but not indignant, I looked elsewhere. Imagine the outcry today if women were excluded on such grounds.

In the thirties and forties I worked for four different women administrators or managers, was comfortable with all of them, and admired them. One was Chinese American; no one saw anything unusual in her position of authority; prejudice was not so common then as some would have us believe. Later when I came to appoint department heads at the Press, it never occurred to me to consider the sex or race of candidates; one simply chose the person who seemed best for the job. Perhaps we will some day come back to the use of common sense in such matters, but I will not live to see it.

During my two years in the accessions department, one of my jobs was to work with a new and young professor of art history from Heidelberg, Walter Horn, who was eager to build up the library's then weak collection in his discipline. Years later Walter and I collaborated on the publication of many books; we even came into conflict, as I will describe.

In 1939 another state examination, a useful one this time, took me to Sacramento as head of the order department in the California State Library. It was not easy to choose the job over a similar offer at the University, but in Sacramento I could make my own selection of books to buy; my first wife was a librarian who had worked there; and the money was better. For the first time in my life, at $200 a month, I felt truly prosperous—a heady feeling that never came again. But the book budget was small and the library, in spite of its central position among public libraries, seemed a backwater. I stuck it out for five years, desperately bored toward the end—as so often before—and was once again saved by an accident.

Some of us belonged to the Sacramento Book Collectors' Club, a group of people interested mostly in California history and in the physical book, whose leading spirits were Mike and Maggie Harrison, she a bookbinder and he with an early start on his great collection of western books, now willed, books and building alike, to the University library in Davis. As for me, I lacked the soul of a true collector, then or later, but accumulated books when I could—not the same thing—and associated with those who collected.

Our little club, like larger ones of its kind, had taken to publishing a few limited editions, perhaps one a year, most of them from manuscripts in the State Library. And when the editor of one volume, also writer of an introductory biography, disappeared into the navy, his manuscript was left to be prepared for the printer. The task fell to Neal Harlow and me, and marked the beginning of a long friendship. Neal went on to UCLA, became chief librarian at the University of British Columbia, and then dean of the library school at Rutgers. He is celebrated among local historians for his elegant and scholarly books on the early maps of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Di-

ego. And after both of us were retired I had the pleasure of sponsoring for the University Press his California Conquered (1982), a fine history of the Mexican War in California.

So we had a manuscript on our hands. Perhaps because the editor-author had been called away too soon, we judged that the writing needed revision, and spent long evenings doing what I have since learned to decry as over-editing—recasting the author's sentences and paragraphs. I am not certain whether he ever forgave us. Nor should he have, perhaps.

This happy editorial interlude ended with publication.[2] Thrown back on the old boredom, I thought of Sam Farquhar, who welcomed librarians on visits to the University Press. Calling on him in Berkeley I asked, with no good reason for hope, whether experience with books in a library was transferable to work with books at a university press. Perhaps so, said Farquhar, and he would think about it. I was at a good age for a move, he said, not too young. He must have been thinking about the kind of help he might need in the postwar years. And in those days, when the Press was less professional than it appeared from the outside, it made some kind of sense—as it did not later—to recruit people with more enthusiasm than experience. And the book we had just seen through the press was Sam's kind of book, a collectors' item.

A few months later, Farquhar called and asked me to take the place of his sales manager, whom he was about to fire—an invitation to jump over the fence from buying books to selling them. But a salesman I was not, as I had learned in Oregon, and there was an uncertainty in the job since rights to it were held by Dorothy Bevis, then on leave in the Coast Guard. Talking with Farquhar in Berkeley, I made what later seemed the only smart move of my life. I sought a real change of profession, said I, and would do the job if I could have the title of assistant manager of the Press,[3] with more general duties

[2] John A. Sutter, Jr., Statement Regarding Early California Experiences , edited, with a biography, by Allan R. Ottley (Sacramento, 1943).

[3] His was manager. The title of director, which then could be held only by members of the academic senate, did not come until 1957.

to come when Bevis returned. Farquhar agreed, subject to the approval of President Sproul. He wrote for that and I waited.

Meanwhile Dean Mitchell thought he might get me the open job of assistant librarian at a large midwestern university—Minnesota, says memory—and I spent anxious weeks fearing that the offer might come through. It was a bigger career opportunity than the Press job, and would be hard to refuse. That summer, while waiting, my wife and I spent the vacation weeks as guests of the Seattle Mountaineers at a camp in Paradise Valley in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. Although mountains had become a strong interest, my chief recollection of the stay is that one evening there came down from the hills and to our campfire the renowned Cambridge critic and philosopher I. A. Richards and his wife; she was a famous climber, and he must have been able to keep up with her. A few years later, as predatory publisher, I would have tried to get a book out of him, but that time was not yet. The talk was of peaks and glaciers.

With happy wisdom the midwestern library chose someone else. Sproul's approval came through, and I moved to Berkeley and the Press in October of 1944. There I would be for more than thirty years. And never again was I bored with my work. By accident and luck I had come to a place that was right for me. Not everyone thought, a few years later, that I was right for it.