3. Gendered Transformations

6. Transformations of Gender and Gendered Transformations

I sobbed and sobbed after my wedding. I couldn’t stand to be away from my father. I fled home whenever I could, and I would stay there for days and days on end, until someone from my father-in-law’s house would come to get me. Then I would sob and sob again. But slowly you visit less, you cry less. And now, in old age, there is hardly any more connection with my father’s house.

After the blood stopped, my body dried out. Even if I wanted to [have sex], I wouldn’t be able to. I had four kids, then my blood dried up, and then my body dried up. Now I have desire (lobh) only for food.

The women I knew in Mangaldihi often spoke of their lives in terms of the profound changes that they had experienced in their bodies, and in the kinds of social ties making up their personhoods, over the life course. In this and the following chapter, I take a more focused look at issues I first raised in the book’s introduction: how does aging affect definitions of gender, and gender affect experiences of aging? These questions speak not only to how we think about gender relations in South Asia but also to how the ways the category of “woman” has been constructed in gender theory more broadly. I will explore two important and interrelated themes: first, the ways in which women’s bodies in Mangaldihi were perceived, controlled, and transformed over their lives; and, second, the ways in which women experienced their changing ties of maya.

| • | • | • |

Gendered Bodies and Everyday Practices

Gender was constructed in Mangaldihi as elsewhere largely through the unceasing work of everyday life, through daily social interactions and sexual relations, through the ways women and men dressed and adorned their bodies, and through people’s movements within and beyond the home. As an anthropologist in Mangaldihi, I first encountered and experienced local constructions of gender at the level of daily practices involving the body, or what Carol Delaney (1991:29) has referred to as the “bodily training” that anthropologists (perhaps especially women anthropologists) must go through when learning to fit into a new sociocultural setting. As a young, recently married woman, I was taught to dress, bathe, interact with others, keep my home, comport my body, and so on as a young village woman and wife does (with some important differences and freedoms because of my anomalous position as a foreigner and researcher).

The specificity and pervasiveness of the everyday bodily requirements that I was expected to observe seemed to me quite unwieldy, unaccustomed as I was to these forms of discipline (though ready to comply quite unconsciously with many of the expectations of my own culture, such as the requirements that women keep their legs together while sitting or be thin). I had to learn to wear saris, to keep my shoulders and legs covered at all times (even when bathing in a public area, as was commonly done), to bathe and change my clothes after defecating or touching anything “impure” (aśuddha), to keep my hair bound in a braid or a knot, to wash my hands after eating, to adorn the part of my hair with the red vermilion of married women, to refrain from keeping the company of men in my home, and so forth. Often it seemed that I could do nothing quite right, and my body was scrutinized for its imperfections and quirks. My skin was becoming too dark: from the Indian sun? from wandering too much beyond the home? I was too thin: would I be infertile, or unattractive to my husband when he rejoined me? My occasional pimples were also causes for concern and comment: were they caused, perhaps, by excessive sexual heat erupting from my body, heat that could not be spent with my husband far away? The process was difficult and at times irritating; but my learning to fit as a woman into village life provided a valuable avenue toward understanding what it was to be a woman in Mangaldihi.

Michel Foucault has written masterfully about how forms of power operate upon the body in modern societies. He argues that distinctly modern forms of power do not emanate from some central source or sovereign figure, but circulate throughout the entire social body via the most minute and pervasive everyday “micropractices,” such as those I have described here—in people’s gestures, habits, bodies, movements, desires, and self-surveillance (1973, 1975, 1979, 1980b, 1980c). Such a notion of capillary power—widely dispersed and anonymous—is particularly useful for analyzing gender relations, for it is through the mundane practices of everyday life that much of the structuring and playing out of gender hierarchies takes place.

As Sandra Bartky (1997:131–32) convincingly argues, however, Foucault himself consistently treats the body as if it were one, as if the bodily experiences of men and women did not differ. But in fact, in many (or all?) societies—certainly in the American and Bengali societies I know—there are disciplines that operate specifically upon women’s bodies to produce uniquely feminine modalities of embodiment (see Bordo 1993:17–19). These disciplines, moreover, often do not emanate primarily from the kinds of modern institutions that are Foucault’s focus (prisons, schools, hospitals, armies, and the like), but rather from the everyday bodily requirements taught to girls and women within their families and local communities.

I soon discovered that most of my training in my first few months in the village had to do, in the dominant patrilineal discourse of Mangaldihi, with containing, controlling, and channeling women’s sexuality toward a husband, marriage, and fertile reproduction within a patrilineage. These bodily regulations were justified and explained largely in terms of perceived differences in the biologies of the two sexes. Women’s bodies were commonly described to me as more “open” (kholā) than men’s, as well as more “hot” (garam). As a result, women could be viewed as particularly vulnerable to impurity (aśuddhatā) and to engaging in improper sexual liaisons.

As I learned how Mangaldihians managed impurity in their daily lives, I was initially struck by their attitudes surrounding the relative openness of women. It was common for both women and men in Mangaldihi to describe women as “impure” (aśuddha), a quality that seemed to be tied to their regarding women—postpubertal and married women, at least—as more open and exposed to mixing than were men. Although people seemed to view the bodies of both women and men as relatively open or permeable, they saw women as being even more so.

Scholars have long noted that Hindus commonly attribute lesser purity to women. While Lynn Bennett (1983:216) finds the cause in a vague sense of sin and impurity attached to menstruation, Catherine Thompson (1985) adds that childbirth, like menstruation, is linked to female pollution, and that women are viewed as particularly polluting when they are not strongly identified with men. I. Julia Leslie (1989:250–52) also mentions the impurity of menstruation, viewed in many Hindu texts as a mark of both a woman’s sexual appetite and her “innate impurity.” She notes, too, that women are often compared in Hindu texts to Sudras (the lowest of the four varṇas, or caste groups, and defiling to the touch), because like Sudras women have lost the right to upanayana, the initiation ritual that upper-caste Hindu men undergo to become “twice-born” (1989:38–40, 251; cf. F. Smith 1991:18). Frederique Marglin, along with noting the impurity of menstrual blood and the “once-born” Sudra-like status of women, offers a more general interpretation of impurity.[1] Impurity, she suggests, has to do with violations of the boundaries of the body, as in menstruation and childbirth (as well as elimination, sexual intercourse, and wounds), with which women are presumably more involved than men (1977:265–66; 1985a:44; 1985c:19–20, 63).

In Mangaldihi, I was first exposed to notions about the impurity of women when I was confronted with people’s bathing practices, as well as their attempts to teach me to control my bodily impurities, influxes, and outflows through bathing. Women apparently became aśuddha very easily—after sleeping in a bed (where saliva or sexual fluids may have spilled), touching unwashed clothing, handling unwashed dishes (which are ẽto, permeated with saliva), engaging in sexual relations, giving birth, menstruating, or touching any other impure person or thing. “Impurity” seemed to be defined in such contexts as a condition stemming from inappropriate, unmatched, or undesired mixing, often of bodily substances. Although this definition is similar to that offered by Marglin, it emphasizes inappropriate, unmatched, or undesired body crossings (what I have called “mixing”); as Marglin herself notes (1985b:66), and as I have explored throughout this book, many bodily crossings or mixings—such as ingesting the leftovers of a deity, or sharing food with intimate friends or kin—are not considered impure at all. Furthermore, in locating impurity in “overflows which cross the boundaries of the body,” Marglin assumes that the body is ordinarily a “bounded entity” (1985b:67; cf. Marglin 1977, 1985a:44, 1985c:90), becoming impure whenever its boundaries are “violated.” This assumption does not match local conceptions of the body or person (both male and female) as ordinarily relatively open and permeable.

The women I knew reacted to the perceived impurity of their bodies in ways that varied considerably. Many women, especially lower-caste women and those who were very busy with work, showed little concern with how pure or impure they might be at any given moment. But in the Brahman neighborhood in which I lived, it seemed that women were continually bathing, and requiring me to bathe, sometimes up to five or six times a day: after I defecated (which unfortunately could occur more than daily, especially when I was suffering from mild dysentery), or visited a lower-caste neighborhood, or came in contact accidentally with some dog-doo, or touched the external panel of a truck carrying a dead body and its mourners to the cremation ground, or returned from a bus trip (where people of many castes and backgrounds mingle closely), and on and on.

I am chagrined to confess, however, that for my first several months in the village, I did not notice that women were much more vulnerable than men to such daily impurities, and thus more frequently subjected to these bathing rituals. Then one day Gurusaday Mukherjee mentioned, quite by chance, that men do not have to bathe after coming into cursory contact with impure things. Men may choose to bathe after defecating or touching unmade beds or lower-caste people, but they do not have to; if they do not, no harm or doṣ will occur (unless, that is, they are going to enter a temple or make offerings to a deity, when special purity is required). I was astounded, not only because I realized that a male anthropologist in Mangaldihi would not have had to spend so many seemingly futile hours bathing, but also because I could not believe that I had been so oblivious to this crucial difference in men’s and women’s daily practices. I spent the next several weeks asking everyone, men and women, why it is that women were more vulnerable to impurity than men.

Their answers led me to believe, as I have already suggested, that most Mangaldihians viewed women as anatomically more open (kholā) than men, and thus more exposed to mixing. Mangaldihians usually explained women’s openness by describing their involvement in menstruation, sexuality, and childbirth—all processes that involve substances going into and out of a woman’s body. For instance, a woman is especially open, and also impure (aśuddha), during her menstrual period.[2] A girl’s first menstruation marks the beginnings of a state of openness, and thus her readiness for marriage, sexual relations, and pregnancy. Menstruation was viewed as a time when excess blood flowed from the body, and a woman had to be “open” for this to occur. In contrast, a pregnant woman is temporarily “closed” (bandha); women who have stopped menstruating after menopause are permanently closed in this respect.

Sexual intercourse also involves opening a woman, and virgins were sometimes described as bandha. Intercourse, said Mangaldihians, takes place within the woman and outside the man. Sexual fluids or semen (śukra) leave the man at the moment of ejaculation to enter and permeate the woman. Once she has slept with a man, a woman contains some of his substance within her permanently, although a man can sleep with a woman with no real lasting effect. The process of childbirth itself was said to make women impure and leave them dangerously open for a period of one month after they gave birth or experienced a late miscarriage or abortion. To remedy this condition—to close and “dry out” (śukote) her body and womb—a woman had to undergo a drying, self-containing, and separative period of birth impurity (aśauc), similar to that occurring after a death in the family.[3]

The village women I knew had clear ideas about the relative openness and impurity of women’s bodies. Subradi, a married Brahman woman, told me, “Women are always impure (apabitra), because everything happens to them (oder sab kichu hae)—menstruation, childbirth. These don’t happen to men. For this reason if men touch a Muslim[4] or defecate, no harm (doṣ) happens to them, and they don’t have to wash their clothes or bathe. But harm happens to a woman.” My companion Hena offered similar comments: “Men are always pure (śuddha). [Especially Brahman men, she explained quickly, but even Bagdi men are relatively pure compared to women.] They don’t menstruate or give birth. Women menstruate, give birth—all that happens to them. Men only defecate, and nothing else.” As Subradi and Hena both put it, things “happen” to women (oder sab kichu hae)—menstruation, childbirth, defecation, and so on. As passive receivers of action, women have a greater vulnerability to outside agents. They are also involved in more processes during which things (bodily substances, even babies) go out from their bodies.

Hena later explained the difference between men and women this way: “[Men] can even come right back from defecating and touch the water jug to drink water! Could we [women] do this? Never!” Another woman said with some sarcasm while discussing the subject with me and a group of other wives, “A Brahman man can even drink alcohol and sleep with a Muci woman [member of the leatherworking caste, the lowest Hindu jāti in Mangaldihi] and no harm (doṣ) happens. A woman never could! This is just the human [or male] system (mānuṣer bidhān).” [5] Another woman added, “For men, mixing is OK (miśāmiśe cale) with all castes. No harm or fault happens to them.”

One common north Indian saying illustrates this notion of the openness or permeability of women particularly vividly: Women are like unglazed earthen water jugs, which are permeable and become easily contaminated to such depth that they cannot be purified. Men are like impermeable brass jugs, which are difficult to contaminate and easy to purify (cf. Dube 1975:163, 1988:16; Jacobson 1978:98). Some told me that only when a Hindu man engages in prolonged contact with lower-caste people or non-Hindus—by eating with them, visiting frequently in the same home, or engaging in a long-term sexual relationship—will lasting impurities accrue to the man’s body.

Brahmans in Mangaldihi also often compared women to low-caste people (or Sudras), saying that both were “impure” (aśuddha). Their reasons included the fact that lower-caste people in Mangaldihi were generally not able (even if they had wished, which many did not) to maintain the levels of purity commonly sought by Brahmans. For instance, they lacked sufficient clothing to be able to change soiled clothes during the day. They also lacked the time required to bathe repeatedly, as their days were filled with labor. Furthermore, because many Bagdi men and women worked outside of the home as field laborers or domestic servants, they were required to mix more indiscriminately with a diversity of people and jātis, often even cleaning the dishes or unwashed clothing (impure from defecation or menstruation) of others. According to dominant Brahman discourses, then, women and Sudras were “open” and subject to impurities in some of the same ways. In addition, neither women nor Sudras could wear the sacred thread indicating the “twice-born” and pure status of an upper-caste male.

A final point made to me about women’s relative openness emphasized not their receptivity but their diffusion. It is women, people told me, who nurse children, cook, fetch water, feed and care for household gods, and handle on a daily basis all sorts of household things. That is why women, rather than men, must take the most care in regulating their mixings with others, lest they exude impurity or unwanted substances onto the household things and members they feed and care for.

Such notions about the relative openness of women’s bodies are not uncommon cross-culturally. Thus Carol Delaney (1991:38) finds that in Turkish society the male body is viewed as self-contained whereas the female body is relatively unbounded. Renne Hirschon (1978:76–80) writes about the ambiguous nature of female “openness” in Greek society, while Jean Comaroff (1985:81) notes the relative lack of closure of female bodies among the Tswana of South Africa. But we must remember that in this community of north India, even the male body was not usually considered to be wholly bound; it was only relatively bound compared to the greater openness of the female body.

| • | • | • |

Another distinctive characteristic of the female body, according to many I knew, was its “hot” (garam) nature. Heat was viewed in Mangaldihi as an element of all mixing and mutuality in social life, including sexuality, attachment, love, and maya, as well as anger and the messy mixings of daily impurities. When people spoke to me of the heat of women’s bodies, they most often were referring to female sexuality.

Both men and women, people told me, produce heating (garam) sexual fluids—uterine or menstrual blood (ārtab,rakta) and semen or seed (śukra). Both male and female sexual fluids are highly distilled forms of blood derived from the cooking of food within the body. But women have more sexual heat than men, at least during their postpubertal and premenopausal years, as is demonstrated by menstruation, which results from an overabundance of hot blood periodically draining from the body.[6]

For this reason, people generally agreed that it was safe, even desirable, for women to have regular sexual relations within marriage, as a way to expend and regulate bodily heat. But men had to be more careful to engage in sexual intercourse with only moderate frequency. While complete abstinence for men could lead to excessive bodily heating, very frequent sexual activity, nocturnal emission, or masturbation could result in excessive cooling and an unhealthy depletion of male vitality, even premature graying or impotence.[7] Many women told me that their husbands thought it best to have intercourse only once a week, although some had engaged in sexual activity almost every night during their first year or two of marriage (thereby causing some husbands concern).

The real danger for women and their families of this greater sexual heat attributed to women seemed to be the possibility of sexual liaisons outside of marriage. Sexuality within marriage, if not unduly excessive, was auspicious and desirable, both for the sake of pleasure and, even more important, for creating children and carrying on the family line. Marglin (1985a, 1985c:89–113) makes the important point that although female sexuality in the Hindu world is impure, it is also inherently auspicious. Marglin’s Oriya informants also note that the separation required of women during their menstrual periods is designed not merely to prevent women from contaminating others but also to express reverence for women’s creative capacities and to allow them, respectfully, to rest (1996:161 and passim; Marglin and Mishra 1993; Marglin and Simon 1994). In Mangaldihi married women spent much of their daily lives enhancing their sexual and reproductive powers (as well as their attractiveness for their husbands)—by wearing red (a symbol of heat, sexuality, fertility, and menstrual blood): they applied red vermilion to the parting of their hair, wore red bangles and saris, and painted red āltā on their feet.[8] Brides-to-be and pregnant young wives were also often fed especially well in their households; they were given delicious heating and nonvegetarian foods in order to enhance their bodily heat, sexuality, and fertility.

But the qualities of sexuality and heat could be very dangerous outside the context of marriage and the patrilineal family line. According to both male and female informants, women were even more likely than men to be unable to resist a sexual urge and be thrown into promiscuity. This perception has long been common throughout India. For instance, Ved and Sylvia Vatuk (1979:215) quote a version of the ballad of the “Lustful Stepmother” popular in Uttar Pradesh in the mid-1940s: “King, there are thousands of old books describing lust, and all agree that 17/20ths of lust belongs to women, 3/20ths to men. That is why you cannot trust her. She has so much power in her body!” Marglin (1985c:60) similarly finds that among the Brahman temple servants in Puri, “women are believed to have four times the sexual power of men.…They are thus four times more likely than men to be unable to resist a sexual urge.” And indeed, many women I knew did speak in general terms about the potential of women to succumb to sexual urges; yet when speaking of their own experiences, almost all described the men in their lives as pursuing sex more fervently than they. Several of E. Valentine Daniel’s male informants similarly commented that although women have more sexual desire than men, they are better able than men to control themselves (1984:171–72). Consensus on these matters is thus difficult to reach.

Most in Mangaldihi seemed to agree, however, that the consequences of women engaging in sexual relations outside of marriage could be grave. An unmarried girl who has sexual relations and whose pregnancy becomes known ruins her reputation and that of her natal family, seriously jeopardizing her own and any younger sisters’ chances for marriage. Mangaldihians told me that in earlier times such young women were thrown out of their households or even killed in order to protect the family’s reputation (though no one could supply a specific instance of such extreme action). Nowadays a pregnant girl’s family will usually try to find out who made her pregnant; and if the man is unmarried and of the same caste, her family will pressure his family into taking the girl as a wife, or at least providing a sizable sum of money for her future dowry—attempts that are not always successful, as a boy’s family can use various strategies to duck responsibility, including blaming the whole affair on the natural promiscuity and sexual voracity of the young woman (Lamb 1992). Brothers or a savvy mother may also intercede early on to get the girl an abortion or induce a miscarriage, sometimes successfully keeping the whole matter a family secret. But no family wants to bring a child into the world who could not grow up as part of a father’s family line and who would be a perpetual reminder of his mother’s indiscretion. In the one case I knew in which an unmarried girl did give birth to a near full-term baby, the baby was immediately killed and buried on the outskirts of the village. According to letters I still receive from the family, the young woman and her younger sisters, years later, remain unable to marry.

A married woman might find it easier to hide an extramarital liaison, because a resulting pregnancy could be her husband’s. (One village woman’s two children, for example, looked distinctly like one of the main temple priests, not her husband. A few furtively gossiped to me—had I noticed?—but publicly people seemed to look the other way.) From a traditional perspective of patrilineality, however, the consequences for such a woman and her household were equally serious. To understand why, we must look briefly at local theories of procreation. In Mangaldihi, as in West Bengal and Bangladesh generally, conception was said to come about through the mixing of the man’s “seed” (bīj), contained in his semen (śukra), with the woman’s uterine blood (ārtab) within the womb (garbha), which is often referred to as a “field” (kshetra).[9] The child produced from this union could be called the “fruit,” or phal. It is the man who is responsible for planting the “seed” of the future child in the womb or “field” of the woman. The seed is generated from the father’s blood, and so by passing his seed on to his child, the father passes on his blood (rakta). The woman also contributes blood to the fetus and child, for she nourishes it with first her uterine blood and then her breast milk, both of which were viewed as distilled forms of blood. But it is the father—both men and women in Mangaldihi agreed—who is the one actively responsible for generating the child through producing and planting the “seed.”

By passing on his seed, the father also passes on his baṃśa, or family line, to his child. At the time of conception, if the parents are married the mother has the same baṃśa as the father, since a woman becomes part of her husband’s baṃśa at marriage. Nonetheless, Bengalis say that it is fathers, not mothers, who provide a baṃśa for their children. The forefather (ādipuruṣ) of a baṃśa is the “root” (mūl) male, and the family line ascends upward from this root through a line of fathers and sons, like a very long-growing and many-branched bamboo.

If a married woman has sexual relations with a man other than her husband, his sexual fluids and bodily substance enter her permanently. Not only is she thus tainted by a stranger or an “other” (parer) man’s substance, but she could pass his residues on to her whole family—when she nourishes her children in her womb and with breast milk, when she cooks for her husband and household members, and when she makes offerings to the ancestors. Several Brahman women told me, too, that ancestors will not accept food offered by an adulteress (cf. Marglin 1985c:53). And obviously, if a married woman becomes pregnant with another man’s seed, she threatens the continuity of her husband’s and his ancestors’ family line, for the child born to the family will not be sprouted from the same male line of “seeds.” So Marglin (1985c:66–67) describes the views of those in neighboring Orissa: “A woman, like a field, must be well guarded, for one wants to reap what one has sown and not what another has sown.”

For men in Mangaldihi, chastity was also regarded as a virtue. Men who openly engaged in extramarital affairs could be said to have a “bad character” (caritra khārāp) or a “bad nature” (svabhāb khārāp). But the merit or demerit resulting from a man’s sexual behavior affected mostly himself, not his household, ancestors, or the continuity of his family line.

Countermeasures: Containing the Body

Because of the perceived potential dangers of a woman’s openness and sexuality, women and girls in the Mangaldihi region were taught by their senior kin to discipline their bodies—to attempt selectively (in certain contexts, especially in public and around men) to close themselves; they relied on spatial seclusion, cloth coverings, binding the hair, special diets, and the like. These disciplining techniques seemed to aim primarily at controlling and channeling a woman’s powers toward desired ends within a patrilineage. Dominant discourses indicated that a woman’s body was in most need of control or containment between the onset of puberty and marriage, as well as during the early years of marriage, because a woman was most vulnerable to violations—sexual and otherwise—of her body and household during those times.

One way of controlling a woman’s vulnerability was through physical isolation. Prepubertal girls and boys enjoyed a relative freedom of movement through all the spaces of the village—walking to the primary school on the village outskirts, running to various stores on errands, playing in dusty lanes and on the banks of ponds. By the time girls graduated from the village’s primary school, however, their spheres of movement became increasingly constricted. Most upper-caste and some lower-caste girls did venture beyond the village to attend high school (except during the four days of their menstrual periods); but they were expected at other times to remain largely within their own neighborhoods; lower-caste girls might fish or work in the fields, but always accompanied by their mothers or other female kin. Within their neighborhoods, unmarried girls still spent time out of their own houses, as they sat in the courtyards or on the doorsteps of their neighbors’ homes, talked, played with friends, and watched people come and go. Girls of this age also often went on brief errands for their elders—to pick up a little sugar or a few matches, or to bring water from the pond or hand pump (attached to a tube well). But gradually, except if working out of the home with other women, they were pressed to confine themselves more strictly to their own homes and neighborhoods.

After women married and moved to their śvaśur bāṛi (father-in-law’s home), their spatial domains contracted even further. Especially when newly married, a wife would rarely go out of the house at all, save her journeys once or twice a day (accompanied by other household women) to the fields to defecate and to a pond to bathe. Gradually, the demands of daily work required that most married women venture out of the house—to fetch water, to wash dishes, or (if the woman was of lower caste) to work in the fields or in other people’s homes. Married women also congregated frequently at village temples to perform vrata rituals for the well-being of their households. And in the late afternoons when their household tasks eased, married women occasionally made brief visits to a neighbor woman’s home for tea, or sat on a front doorstep talking with other women and children. But other than such necessary or brief interludes, married women confined their movements largely to the interiors of their homes: cooking, cleaning, caring for children, and talking among household members and guests.

Men, in contrast, lived and moved relatively “outside” (bāire) throughout their lives. The young men of Mangaldihi, both married and unmarried, congregated together in groups in the village’s most public and central places, as well as on the village’s outer peripheries and beyond. Young men gathered for hours every day at the village tea shops, read the daily newspapers at the central library, hung out in front of the two new video halls, sat in groups in the central village green, played soccer on the playing field on the village outskirts, sat on the paved road by the bus stop watching people come and go, and had “picnics” in the village’s outer fields. These were places where women rarely ventured, and I often longed to be able to join them there—their activities looked fun and free. Hena agreed; but she advised me not to go. Men also made frequent outings to towns and villages beyond Mangaldihi, whether commuting to work or buying and selling goods in larger markets.

Women were also contained by their clothing, which covered their bodies and neutralized their sexuality. Young village girls wore knee-length, light cotton “frocks,” which were gradually replaced with full-length salwar-kameez (pantsuits) and then saris as the girls passed through puberty and reached marriageable age. It was improper for married women, and mature unmarried girls, to expose too much of their bodies, including their calves and shoulders. Some girls found the transition to these more modest and restrictive forms of clothing quite disturbing. Choto described how horrible she felt when her parents first began to make her wear a salwar-kameez and veil to cover her legs, shoulders, and chest whenever she left the neighborhood. She had begun to develop earlier than her friends and could not understand why she had to wear these new clothes, why her body had suddenly become a private and shameful thing. Married women also covered their heads with the ends of their saris (as a ghomṭā, or veil) whenever they were in the presence of senior men in their husbands’ households and villages. This veiling, performed as an act of respect and avoidance, served a double function: it protected men from overexposure to women’s power and it protected women from unwanted male advances (cf. Papanek and Minault 1982).[10] For their part, men had a wide range of clothing available to them. Many who could afford it and those who commuted to jobs in cities enjoyed wearing Western-style shirts and trousers. But when days were warm and when they were casually hanging out at home or in tea stalls, or when they went to work in fields, most men wore lungis (informal loin cloths) or dhotis: cloths wrapped around the waist, with chest and calves exposed.

As a measure to curtail excessive openness, women were also expected to bind their hair, keeping it in braids or tied up in a knot. Women ordinarily bound their hair whenever going out in public, and in fact in my early days in the village people would disapprovingly wonder why I kept my hair loose or “open” (kholā), until I gave in and began routinely to tie my hair up. It was particularly important to bind the hair during menstruation, presumably to counter the woman’s excessive openness during this period.[11]

Some women also employed cooling diets (avoiding “hot” foods such as fish, garlic, and onions) to close their bodies and restrain their sexuality. This regime was followed after childbirth (when a woman’s body is dangerously open), after becoming a widow (when a woman has no legitimate means of expending sexual energy), and sometimes after entering puberty (especially if a girl suffers from acne, a condition said to come about from excessive sexual heat erupting through the skin). The bathing practices described above were also intended to contain the body (controlling its influxes and outflows) by purifying it of unwanted intrusions and by preventing these substances from entering women’s households.

These countermeasures, particularly spatial seclusion and veiling, are known in much of north and central India as “purdah,” a word literally meaning “a curtain.” [12] The term (pardā in Bengali) is not commonly used in the Mangaldihi region of West Bengal, but women’s daily practices often did create a protective “curtain” around them. These practices functioned to contain a woman’s most important and intimate interactions within her household, and to channel her sexual and reproductive powers toward her husband and toward extending his patrilineage. A gentle, middle-aged Brahman priest illuminated their significance when he told me, “Women have more power (śakti) than men, but their powers come from serving others, not from acting alone.”

| • | • | • |

Competing Perspectives: Everyday Forms of Resistance

How did women in Mangaldihi feel about all these forms of bodily training? Until recently, many ethnographies of gender in South Asia left the impression that women silently and compliantly accept a monolithic set of cultural values about the polluting and dangerous dimensions of their bodies and sexuality.[13] More recent work, however, has sought to uncover the ways in which many women are able to critique, reinterpret, or resist such dominant ideologies, through their songs, stories, gestures, and everyday practices (e.g., Raheja and Gold 1994, Das 1988, Jeffery and Jeffery 1996). Gloria Raheja and Ann Gold (1994:10) incisively argue (also citing Das 1988): “[T]o assume that such characterizations [of the polluting and dangerous dimensions of women’s bodies] define the limits of women’s self-understandings and moral discourse is to ignore or silence meanings that are voiced in ritual songs and stories…and in gestures and metamessages in ordinary language throughout northern India.” Submission and silence, furthermore, do not necessarily indicate an unequivocal, fully internalized compliance or modesty; they may at times be conscious and expedient strategies deployed by women.[14] In Mangaldihi, the women I knew presented alternative visions and practices of the female body, working around and subtly challenging (even as they often voiced and acquiesced to) the kinds of dominant ideologies I have been describing thus far.

At the same time that I was taught by many of the women in my neighborhood how to manage my body—by bathing, being cautious about what I touched, binding my hair, and so forth—I was also taught how to get around some of these restrictions in more subtle or private ways. Though many women appeared to be meticulous about matters of purity, others seemed to observe these strictures just enough to avoid criticism, without having fully internalized or accepted notions about the dangers of female impurity. For instance, on several occasions when I and a female companion were returning from visiting a low-caste or non-Hindu (Muslim or Santal) neighborhood, my companion would whisper to me as we approached our neighborhood, “Let’s not tell anyone that we touched anyone there—then we won’t have to bathe.” I should note, however, that this happened most often if the woman accompanying me was unmarried—indeed, only once did a married woman propose such a plan. Apparently women felt increasingly obligated as wives to comply with expected standards as they took on more responsibilities of upholding the household, cooking, caring for deities, and so on.

On another occasion, a young woman friend suddenly had to defecate just as we were about to catch a bus to make a trip to town. Whereas most in the village relieved themselves in the fields, my landlord let me make use of their fancy outhouse; it was a small brick building with two chambers, one for urinating and one for defecating. My friend suggested that she would use that outhouse (since she was with me) and said that if anyone noticed her going in, she would say that she had just gone into the urinating chamber (an action that would not require her to bathe), because she did not want to have to stop to bathe and change her clothes before going to town. “Great idea!” I said, happy to know that some women played with the rules. (I had previously thought of that same trick with the outhouse myself.)

Another example of a woman who did not seem fully to accept public notions about the gravity of female pollution was provided by a pilgrim on the bus tour I took from Mangaldihi to Puri (see chapter 4). The dominant ideology in the region held that menstruating women were not fit pilgrims and should not enter temples. One morning, however, some used menstrual rags were found in a corner of the bathroom of the pilgrim’s guest house where the group had stayed the night. Some older women began exclaiming, “Chi! Chi! What a great sin (mahāpāp) to go on a pilgrimage while menstruating!” but then the matter was dropped. I later happened to find out who the menstruating woman was. She admitted to me that she realized that her period might begin on the pilgrimage, but she had really wanted to go. She added that she believed that no harm (doṣ) would occur, because her devotion (bhaktī) was pure (pabitra). (I was a bit relieved to hear this, because my period had unfortunately begun on the journey as well.)[15] As far as I could tell, she successfully kept the matter a secret, and none of the other women made any real effort to discover who the source of the rags was.

Even those who maintained strict bodily purity sometimes acted for reasons more complex than a simple acquiescence to the official views about female bodies. For instance, there was one Brahman woman in our neighborhood who was known to be extremely “finicky” or “fastidious” (khũtkhũte) about matters of purity. She was continually washing her hands, bathing, changing her clothes, and scrubbing the house. She made her two daughters bathe and change their clothes each time they reentered the home from school or play. She resisted touching other people or things, even her own daughters, except when necessary. Other women told me, as a partial explanation, that her husband was having a long-term, public affair with a low-caste woman, whom he kept in a separate home on the borders of the village. Perhaps maintaining an extreme state of bodily purity was the only way available to this woman to gain some control over her own body, and to close herself to the intrusions the other woman and her husband were making into her life.

I also encountered a wide diversity of women’s perspectives and practices surrounding female sexuality, some of which subverted dominant patrilineal ideologies. Sexuality was a common and welcome topic of conversation among women, especially when a new bride was present. This gave women the opportunity to crowd around and probe her about her new sexual experiences: How was she enjoying it? How many times had they done it? One new bride, with her husband’s apparent approval, came to ask me for tips from my own culture or experiences on how a woman can increase her sexual pleasure.

Some women (married and unmarried) had sexual relations outside of marriage, and seemed to be able to manage them with no serious consequences. I met one such amorously involved woman, whom I will call Keya, on my first afternoon in Mangaldihi. Shortly after I had deposited my few household belongings in the small mud hut in which I was to reside, two married women whom I guessed to be in their early thirties came to pay me a visit. We chatted for a little while about this and that, and then Keya, to my surprise, asked me how to say the names of the male and female sexual organs in English. I told her. She smiled with pleasure, and then began to say the words loudly while laughing with her friend; she repeated them for the rest of the afternoon, as they returned to their household work. (I was only slightly comforted by the hope that no one else, other than we three, would be able to understand what she was saying.) I later found out that probably some of her eagerness to discuss sexual matters in this strangely public yet surreptitious way stemmed from her engagement in a clandestine love affair with another married young man of the village. Her own marriage had been arranged against her will to a man considerably older than she was; he had married her after his first wife, her own sister, had died while he had been attempting to give her an abortion (I never knew precisely how or why). Keya had never been particularly romantically inclined toward her husband—nor he toward her, from what I could gather. In large part, her role in the marriage consisted of caring for her husband’s children by her sister. One way that she could gain some degree of pleasure and agency in her life was through taking a lover. (Once, when her husband was out of town for a few days, she borrowed one of my lace American bras.)

In the one case I encountered (mentioned above) in which an unmarried girl, “Mithu,” did become pregnant with tragic consequences, it is important to note that criticisms of the village women focused not on the ruined chastity or sexual promiscuity of the young girl (accusations voiced by the young man’s family, in an attempt to thrust all blame squarely on her) but rather on the unforgivable naïveté of a young woman and her mother who did nothing to terminate a pregnancy before it became public. Underlying the village women’s discourse seemed to be the notion that the virtue of a woman is tied not only or even primarily to traditional notions of chastity but also to the strategic capacity (or lack thereof) of a woman to construct a virtuous public image or “name” (nām). These conversations led me to realize that many of the women I knew strove to maintain an appearance of self-containment, purity, or chastity not so much because they believed that they were more sexually dangerous or impure than men, but because they understood that maintaining such a public image was the only way for them to preserve both their own honor and that of the men and women in their families whom they cared about.

Their complex, multilayered perspectives seemed to resonate with those of Dadi, the mother-in-law of the evocative film Dadi’s Family. Remembering her earlier years as a young wife, Dadi speaks in her resolute and thoughtful mode: “I piled on the yeses, but I did what I wanted to do.” Resistance must often be subtle. I do not want to deny the felt oppressiveness of many of the ideologies and practices that did discipline and control local women’s bodies, movements, and lives, or to exaggerate or romanticize their capacities to resist. At the same time, it would be wrong and misleading to overlook the ways that women in Mangaldihi did in many contexts reinterpret, play with, subvert, and critically evaluate the disciplining practices and ideologies that otherwise often served to control their bodies and lives.

| • | • | • |

The Changes of Age

Older Women

If one of our aims, as scholars of gender in South Asia and elsewhere, is to complicate our understandings of the structuring of gender relations, then it is important not only to look at the multiple, competing ways that women imagine and interpret, resist, and criticize dominant ideologies of gender in their societies, but also to examine the ways that women’s bodies, identities, and forms of power (or subordination) are perceived to change over the life course. Women’s bodies and identities in north India do not stay the same throughout their lives. A few scholars have acknowledged the shifting roles that Indian women assume within their households and families, as daughters, sisters, wives, mothers, and mothers-in-law. But almost no work has been done on how women’s bodies are perceived to change over a lifetime, and the concomitant social and political implications of these changes (an exception is S. Vatuk 1992). As a result, ethnographies of gender in South Asia (including the earlier pages of this chapter) have tended to give the impression that local definitions of female embodiment revolve centrally around sexuality, fertility, childbirth, and menstruation, and that categories of gender are tied to differences between women and men perceived to be fixed and dichotomous. In Mangaldihi, however, as I first mentioned in the introduction, women were believed to undergo significant changes in their somatic (and related social) identities as they aged, in ways suggesting that to analyze local definitions of gender by concentrating only on women during their married and reproductive years would lead to seriously flawed conclusions.

According to the villagers, women experienced a relative closing and cooling of the body as they entered into postreproductive phases of life. Thus the qualities of “heat” and “openness” that were often used to describe female bodies in fact pertained to women during their premenopausal (and postpubertal) years only. Such bodily cooling also meant that older women could freely give up most countermeasures of purdah, or “curtaining” and containment, that many had earlier practiced. Menopause in and of itself did not constitute a very highly marked or visible transition in women’s lives in Mangaldihi.[16] It was important; but many of the changes that went along with menopause (namely, a cessation in sexual and reproductive activities) usually began earlier, as women married off their children and moved to the more detached, celibate peripheries of household life (see chapter 4). Menopause nonetheless added an important dimension to an aging woman’s bodily and social transitions: a “closing” of the body and, with this, an increased purity and freedom of interaction.

The process of menopause, which was called a “stopping (or closing) of menstruation” (māsik bandha hāoyā), was perceived to entail a cooling, drying, and relative closing of the woman’s body. As menstruation involves the release of excess sexual-reproductive heat, so the stopping of the menstrual flow marks a depletion and cooling of this heat, and thus a decrease in (hot) sexual desires and reproductive capacities. Women said that after menopause, their bodies had become cool and dry and they no longer felt the heat of sexual desire. Early on in my stay, I asked Choto Ma if old people were hot or cold. She teased me at first for asking such a silly question. “Of course the bodies of young people like you are hot,” she said, and her knowing smile indicated that she was referring at least in part to sexual heat. Then she added seriously, “Old people are not hot like that.” Her friend and sister-in-law, Mejo Ma, added: “When you get old, everything becomes closed or stopped (bandha). That which happens between husband and wife stops. Menstruation stops. And then when your husband dies, eating all hot food stops as well.[17] This is so that the body will dry out and not be hot (jāte śarīr śukiye jābe, garam habe nā).”

Bhogi Bagdi also spoke to me of the cooling and drying of her body after menopause. She enjoyed sitting in the narrow, dusty lane in front of her house talking about sex, using vulgar language, and teasing the young people who visited her about their sexual practices. So I asked her one day if she still had sexual desire. She answered quickly (as I reported in an epigraph to this chapter): “No, of course not! After the blood stopped, my body dried out (rakta bandha hāoyār par, śarīr śukiye geche). Even if I wanted to [have sex], I wouldn’t be able to. I had four kids, then my blood dried up, and then my body dried up (deha śukiye geche). Now I have desire (lobh) only for food.”

Although most women began to refrain from engaging in sexual and reproductive activity before menopause, menopause nonetheless signified for women a complete stopping of sexual-reproductive processes—not only of the activities themselves but of the capacities to engage in them. The nature of the body thus fundamentally changed.

This cooling of somatic heat in conjunction with the cessation of menstrual flow could, some said, be accompanied by an increase in the heat of anger (rāg). Several mentioned that although old women no longer feel the heat of sexual desire, they do become easily “hot” or angry in the head (māthā garam hae jāe). While these might appear to be references to what we label “hot flashes,” these sensations did not seem to be a culturally recognized phenomenon for Mangaldihians. I asked quite a few women about feeling warm during menopause, and only two mentioned that they had experienced this: one described a feeling of “fire” (āgun) in the head, and the other spoke of having “hot ears” (garam kān). More told me instead that women can become easily angry (also a “hot-headed” state) in older age. This transfer of heat from sexuality to anger did not seem to be viewed as gender specific, however: it could happen to older men as well (cf. Cohen 1998).

For women, the significance of this transition lay in their change to a state of increased purity, coolness, and relative boundedness of the body. It was at this point, after a woman’s menstrual periods had stopped and especially if she was widowed and upper caste, that a woman was considered to be “pure” (śuddha or pabitra), comparable to a deity (ṭhākurer moto), and in some ways “like a man.” The perception that postmenopausal women are in significant ways “like men” can also be found elsewhere in India (e.g., Flint 1975) and in other societies, such as the Kel Ewey Tuareg of northeastern Niger (Rasmussen 1987) and the Bedouins of Egypt (Abu-Lughod 1986:131, 133). When I would ask why, village women would explain that old women no longer menstruate, no longer give birth, no longer have sex, and (especially if they are upper-caste widows) no longer eat hot, nonvegetarian (āmiṣ) foods. This makes them continually “pure” (śuddha) like men, who also do not menstruate or give birth; and it makes them similar to the dominant deities of Mangaldihi as well (Syamcand and Madan Gopal, forms of Krishna), for these gods were only served cooling, vegetarian foods and were, of course, kept in a state of purity.[18] Furthermore, it was particularly postmenopausal widows who were described as “pure” and manlike, presumably because they were categorically free from the hot and female activities of sexuality and wifehood.[19] A married older woman, even if not sexually active, was still a wife (sadhobā, “with husband”), after all; and she continued to be associated with sexuality, fertility, and marital relations as long as she adorned her body with auspicious red vermilion and wore red-bordered saris, as a proper wife should.

According to local opinion, the sexual heat and desire (kām) of men also wanes in old age. But as men never have as much sexual heat and desire as women in the first place, their transformation toward increasing asexuality is not as dramatic. E. Valentine Daniel (1984:165) describes a similar perspective offered by a resident of Tamil Nadu. According to this informant, the sexual fluids (intiriam) of a male remain qualitatively and quantitatively the same throughout life. A woman, in contrast, produces vastly more sexual fluids than a man throughout most of her life, but about ten to twelve years following menopause she begins to produce only the smaller amount that a man does.

Young and older women alike in Mangaldihi spoke of the process of stopping menstruation and becoming more like a man as a positive one. In the United States, menopause is popularly conceived as a largely negative experience that signifies an irreversible process of female aging, with its loss of youth, beauty, and sexuality, and is accompanied by painful “symptoms” such as hot flashes and diseases such as osteoporosis (e.g., Lock 1982, 1993; E. Martin 1987). When I asked women in Mangaldihi what they thought about the end of menstruation, however, they almost uniformly replied that it was a good thing (see also S. Vatuk 1992:163–64). Ceasing to menstruate meant being free from the hassles of monthly bleeding and impurity, being able to travel (without fear of causing an embarrassing mess on a bus or train), being able to go on longer pilgrimages (without fear of bringing menstrual impurities before the deities), and being able to cook for temple and household gods whenever one liked—all practices (village women noted) available to men throughout their lives.[20] By the beginning of this phase, most women also felt that they had had enough children (except those widowed at a young age and not remarried, who could not expect to bear children anyway); so loss of fertility was not experienced with regret. A few women who had not yet stopped menstruating even complained to me, “Why do my periods keep coming? My time for stopping has come.”

As women experienced menopause and a relative closing and cooling, they also made changes in how they dressed and adorned their bodies. As I mentioned in chapter 4, men and women both tended to wear more white and dress more simply as they entered old age. But the transformation in modes of dress was most striking for women. From wearing mostly red and other bright colors and adorning their bodies with jewelry, hair ribbons, and perfume in their young and newly married years, women in Mangaldihi in their later years took to wearing mainly the cool color of white and relinquishing bodily adornments. Older nonwidowed women could still wear saris with red-colored borders, and they continued to wear marriage bangles and red vermilion in the parts of their hair; but as their children married, they also increasingly wore saris that were predominantly white, as a sign of their older and postreproductive status. Most also gave up other forms of adornment, claiming that it was no longer appropriate or necessary for them to highlight their physical attractiveness. They thus avoided wearing fancy silk, polyester, and newly starched saris in favor of worn, simple cotton ones, and they limited any jewelry to perhaps a simple everyday chain and small pair of earrings.

Women whose children were largely grown and who were past childbearing also frequently quit wearing blouses under their saris, except when going out of the neighborhood or village. Blouses were mandatory for younger women to cover their breasts and shoulders (and even the sleeveless blouses now popular in India’s cities were considered improperly revealing in Mangaldihi); but older women would say to me that for them, wearing blouses was an unnecessary kind of “dressing up” (sājāno). Older women began to reveal their calves much more, hiking their saris up to their knees on hot days and leaving off their petticoats. Khudi Thakrun frequently wandered around the village with her breasts and calves entirely exposed, her white sari simply tied around her waist (much as a man would wear a dhoti or loin cloth), and her breasts, wrinkled and long from nursing nine children, hanging down almost to her waist (see photograph 1 in chapter 3). Older Brahman widows commonly began even to wear men’s white dhotis in place of saris. Furthermore, women could increasingly relax their veiling practices as they advanced in seniority, pulling saris over their heads only on more formal occasions when senior male kin (whose numbers were decreasing) were present (see also U. Sharma 1978:223).

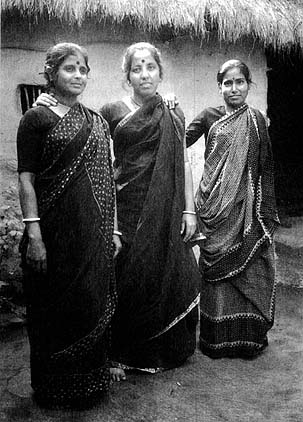

Young sisters-in-law in colorful saris: (from left) Ranga, Chobi, and Savitri, Brahman women married to three brothers.

Mejo Ma, Choto Ma, and Boro Ma: three Brahman sisters-in-law and friends dressed in white and out for a walk.

Covering the body reduces warmth and is a barrier to interaction; decorating the body attracts and invites attention. Both actions were thought appropriate in younger, sexually active women but inappropriate (as well as unnecessary) in older, postreproductive women. Nakedness, too, was interpreted in two different ways, depending on the life stage of the woman: it was sexually provocative in the young, and a sign of asexuality in the old.

Sylvia Vatuk (1992:164–67) similarly describes how older women with married children in western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi wear white and light-colored clothing and avoid adorning their bodies. She finds these practices to be seemingly paradoxical social constraints imposed on the sexuality of older women: Why, if older (postmenopausal and postreproductive) women are thought to be asexual, should their sexuality be controlled or constrained by restrictions on dress and physical adornment? My interpretation here is somewhat different: the modes of dress of older Indian women do not constitute a kind of personal or social “constraint” on an older woman’s sexuality as much as they express her relative asexuality. Although the cool, white, simple clothing of an older woman plays a part in transforming her into an asexual person (and thereby controls any lingering sexuality that would be considered inappropriate at this stage of life), it also serves as an index of an asexuality that, in Mangaldihi at least, was regarded as occurring naturally.

As women entered postreproductive life phases, they also transformed their gender by altering their spatial movements. As already noted, women were fairly domestic with little outside wandering as postpubertal unmarried girls, and then became very domestic and largely confined to their houses as wives. But as their daughters-in-law began to take over domestic work, and especially as they became widowed, older women spent more and more time out of their homes. Dressed in white, they roamed through village lanes visiting each others’ homes, playing cards, congregating on the cool floors of temples, and sitting on the roadsides or by storefronts watching people come and go. They also frequented public rituals, plays, and other events that younger wives were often too busy or confined to attend. They traveled beyond Mangaldihi, paying extended visits to married daughters’ homes and going on pilgrimages to faraway holy places. These external wanderings were facilitated by the cooling, closing, and decreasing sexuality of older women’s bodies (whether natural or imposed), for they and their families no longer found it necessary to control and constrain their bodies and interactions. In these ways, being older struck me as a very freeing, open, and pleasurable phase of life for women.

Older Men

Men in Mangaldihi did not undergo nearly as marked a transformation in their modes of dress and spatial movements over their lives; nor were their sexuality and bodily natures as dramatically transformed. Just as it was impossible to tell from his clothing whether a man was married or single (for men wore no outer signs of marriage, as women did), it was also impossible to tell whether a man was “senior” (buṛo). Around Mangaldihi, the traditional dress of men at any life stage was a white dhoti and panjābī (long shirt) for everyday or more formal wear, and a colored lungi for casual wear. This clothing could be worn by younger and older men alike. Fashionable and well-educated younger men often wore Western-style slacks and shirts, and it remains to be seen whether they will continue wearing the same kind of clothing when they become senior.

Men, moreover, were seen to be living and moving relatively “outside” (bāire) throughout their lives. Older men who had reduced their economic responsibilities and had more free time often congregated together in public places, as older women did. But these older men’s groups differed little from those of younger men, who also used their free time (which for many was plentiful, especially during seasons of agricultural lull) to gather together in public places.

Nonetheless, there were subtle signs of distinction between older and younger men’s dress and spatial domains. Older men tended to dress more simply, while younger men were more preoccupied with looking handsome and appearing in fashion. Mangaldihi’s younger men tended to oil their hair more frequently, to get new haircuts that they kept nicely combed, and to wear shoes and newer clothing. It was not uncommon for a young man to ask me if he was looking good. Older men, like older women, usually wore more simple, well-worn cotton clothing, frequently went without shoes, and paid less obvious attention to their appearance.

An older Bagdi man cares for a neighbor's child.

Furthermore, as a senior village man became increasingly weak or infirm, he would spend more and more time in the household, sitting or resting on a cot in a corner of the courtyard or on the veranda, watching the household activities, receiving occasional visitors, and sometimes looking after small children. Therefore, as women were transformed in older age to become more like men in their bodily natures, spatial movements, and outer wanderings, men in a way became more like women—increasingly domestic and confined to the home.

People in Mangaldihi clearly used the body to define gender, but they did not rely on a male/female distinction based on dichotomous and fixed physiological differences, as is presumed in much contemporary feminist theory, which takes female physiology, sexuality, and reproductivity to define “woman” as a category across time and space (cf. Moore 1994:8–27; Nicholson 1994; Ortner 1996:137). Rather, the interrelated somatic, social, and political identities of gender—expressed and experienced via bodily regulations, spatial movements, dress, and perceived physiological processes—changed in profound ways over the life course. These changes made women (especially by late life) in some ways “like men,” and men in some (though less acknowledged) ways like women.

| • | • | • |

Women, Maya, and Aging

As women’s bodies underwent important changes as they aged, what about the ties of their maya? Did the relative openness of women throughout much of their lives mean, for instance, that women, compared to men, were more connected to others, more entwined in a net of maya? Not exactly. At least, no one offered me precisely this explanation, though women in Mangaldihi perhaps even more than men did value crowded togetherness, seeking to work together, bathe together, and eat together, as Margaret Trawick (1990b:73) also found among the women she knew in Tamil Nadu.[21] The main difference between women and men with regard to maya was that women’s ties were unmade and remade at a greater number of critical junctures in their lives, not only through aging and dying, but also in marriage and widowhood. The most important connections of males were made only once and tended to endure throughout and beyond their lifetimes, while those of females were repeatedly altered—first made, then unmade and remade, then often unmade once more.

In the dominant patrilineal discourse of Mangaldihi, women were said to be capable of such changes because their bodies were naturally more open than men’s. The same traits of openness and permeability that made young women vulnerable to impurity and sexual violations could also be viewed as making women well-suited to marital exchange. According to one piece of proverbial wisdom, a woman would fare best if she were malleable like clay, to be cast into a shape of his choice by the potter (her husband), discarding earlier loyalties, attributes, and ties to become absorbed into her husband’s family (cf. Dube 1988:18).

The positions of boys and girls in their natal families were differentiated from infancy and childhood. Infants of both sexes were initially connected with their kin and village by a ceremony to mark the first feeding of rice (annaprāśana). But male children were distinguished by the greater scale and elaboration of that ceremony, and among the upper castes by several other subsequent life cycle ceremonies of “marking” or “refining” (saṃskāra) (Lamb 1993:348–63). Among Brahmans, marriage thus might be the eighth connection-making ceremony for a boy, but only the second for a girl. During each of the male child’s saṃskāras, the family would perform a nāndīmukh, a ritual offering to the ancestors meant to introduce and formally connect the boy to his patrilineage.

While the boy was commonly identified as a growing node of the patrilineage (baṃśa), meant to extend the patriline into future generations, a girl was often spoken of as a mere temporary sojourner awaiting her departure in marriage. Thus, she would have no ancestor-connecting nāndīmukh performed for her in infancy or childhood; only at her marriage were the ancestors asked for their parting blessings. Sayings, nursery rhymes, and everyday conversations conveyed to a daughter the unmistakable message that her stay in her parental home was short. I heard Mangaldihi girls at times singing lightheartedly a popular Bengali lullaby that struck me as painfully affecting:

Rock-a-bye baby, combs in your pretty hair The bridegroom will come soon and take you away The drums beat loudly, The shehnai is playing softly A stranger’s son has come to fetch me Come my playmates, come with our toys Let us play, for I shall never play again When I go off to the stranger’s house.[22]

A phrase I would often hear was “A daughter is nothing at all. You just raise them for a few days, and then to others you give them away.” People spoke of daughters as “belonging not to us but to others.” The young girl who worked for me, Beli, said to me once: “If you’re going to have children, you shouldn’t have a daughter. You have to give a daughter away to an other’s house (parer ghar).” Expressions from other regions of India convey similar sentiments: “Bringing up a daughter is like watering a plant in another’s courtyard,” goes a Telugu saying (Dube 1988:12) heard also in Uttar Pradesh (Jeffery, Jeffery, and Lyon 1989:23). Girls in Kangra, northwest India, hear that a daughter is a bird “who after eating the seeds set out, will fly,” or a “guest who will soon depart” (Narayan 1986:69). Such sentiments do not imply that girls were unloved or unwanted. In fact, parents in Mangaldihi wanted to keep their daughters; they just couldn’t. They seemed to love and cherish their daughters with an added intensity and poignancy in anticipation of their pending departure.[23]

Men in Mangaldihi, in contrast, usually resided—save perhaps for brief periods of work in other cities—within the same community and on the same soil where they were born. This is why, some men said, it is so difficult for them to loosen their ties of maya at the end of a lifetime, for they have become so deeply embedded within a family, community, home, soil. Among the several families I knew who had settled in Calcutta apartments after fleeing East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) at the time of partition, men spoke of having been forced painfully to cut apart the ties of their maya prematurely, as a woman does in marriage; they viewed the years following independence and partition as very “separate,” “independent,” and maya-reducing times.

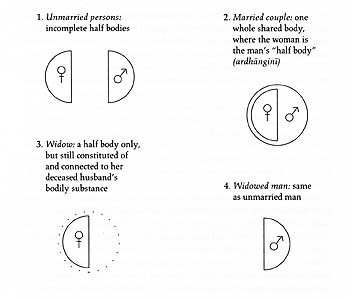

For girls in Mangaldihi, it was through marriage that they became most marked and that the ties of their personhood were substantially unmade and remade. Throughout the three-day wedding, the bride would be made to absorb substances originating from her husband’s body and household. She rubbed her body with turmeric paste with which he had first been anointed, she ate leftover food from his plate, she absorbed his sexual fluids, she moved to his place of residence, and there she mingled with his kin and mixed with the substances of his soil. The bride’s surname and patrilineal membership (baṃśa) would also be formally changed to those of her husband. In this way, her marriage was generally interpreted as obscuring and greatly reducing, although not obliterating, the connections she once enjoyed with her natal home. She would no longer refer to persons of her natal family as her “own people” (nijer lok) but rather as her husband did—as her “relatives by marriage” (kuṭumb); for she was said to have become by marriage the “half body” (ardhānginī) of her husband (see also Inden and Nicholas 1977:39–51; Sax 1991:77–83).

For a girl, then, preparing to marry was in some ways like a first confrontation with mortality. The young brides who spoke to me anticipated the pain of cutting so many ties with their natal families, homes, and friends with dread, not comprehending how they would ever survive such an ordeal. These conversations were similar to those I had with older people about the separations at death. During the months preceding her wedding, my companion Hena would say to me through tears, “Your father gives you away. He makes you other. He wipes out the relation.” She would also purposefully pick quarrels with me in order, she said, “to cut the maya” a bit before her actual departure.

Many analyses of Hindu marriage have long stressed that a bride’s transfer to her marital kin is a complete break.[24] More recently, however, anthropological studies of kinship and gender in India have pointed to evidence of a woman’s continuing ties to natal kin. William Sax (1991:77–126) and Gloria Raheja and Ann Gold (1994:73–120), for instance, argue that many writing on Indian social structure have for too long overemphasized the view of marriage as a complete transformation of a woman (an argument often grounded largely in textual analyses), overlooking other perspectives that stress that a woman’s ties with her natal kin and place can never be entirely effaced (see also Dube 1988:18; Jacobson 1977; Raheja 1995).

In Mangaldihi, too, women and men both agreed that however neglected, violated, or abused their earlier ties might be after marriage, a connection does remain forever between a married daughter and her natal kin. Just as maya cannot be suddenly and completely cut in aging and dying (see chapters 4 and 5), neither can the “pull” (ṭān) of maya, “of blood,” or “of the womb” between a girl and her natal home be wiped out entirely through marriage. Some of the rituals of marriage even served to affirm a departing bride’s natal ties. Marriage was the only time (save once again, four days after her parents died) when a girl’s nāndīmukh, ritual offering to her maternal and paternal ancestors, was performed in her name. On the day before her wedding, too, a bride would eat rice that she had collected uncooked from twenty-five neighborhood houses, to affirm her mutual ties with other village women even as she prepared to depart.

A married woman’s practices after the wedding were also crucial. According to Mangaldihians, the extent to which a married woman would be able to sustain valuable ties with the people of her father’s home depended largely on the amount of contact she succeeded in maintaining with them, through visiting and gift giving. During the first few years of marriage, young brides would often spend weeks or even months at their fathers’ homes, returning eagerly whenever natal kin came to call for them. Married women commonly returned to their natal homes for the birth of their first child and on special ritual occasions, when married daughters and sisters were summoned; these included the largest annual Bengali festival, Durga Puja (worship of the goddess Durga during her annual visit to her father’s home); Jamai Sasthi (day for honoring a married daughter’s or sister’s husband); and Bhai Phota (day on which married and unmarried sisters honor their brothers). Most married women thus had two houses they could call home—their bāperbāṛi (father’s house) and their śvaśurbāṛi (father-in-law’s house).

Maintaining these ties depended on negotiation as well as luck (her natal family’s interest in her, the supportiveness of her in-laws in allowing her to leave, the distance between the two homes, the financial resources required for travel and gift giving). A married woman could not decide to visit her natal family on her own; she had to wait for someone from her father’s house to come call for her. Women, though, sometimes sent letters or messages to their father’s homes, asking to be called for. Some secretly stowed away change or an extra petticoat to give to their mothers when visiting.

We see here that to understand women’s positions within families we must take into account not only patrilineal lineage, or baṃśa, but also maya, affection. Baṃśa is one thing (unmarried girls are in their fathers’ baṃśas; married women in their husbands’); but maya can be something different—imaged in terms of “love,” ties of the “womb” and of “milk,” gifts given, and time spent. Maya here can even be thought of as offering an alternative discourse to that of patrilineal kinship.

A married woman’s persisting connections of maya with her natal kin notwithstanding, Mangaldihi villagers still stressed the transience of a woman’s relations with her natal home. Mothers and wives emphasized this fleetingness at least as much as fathers and husbands did. Most mothers had known such separations from personal experience, and at each visit after marriage (whether their own or others’) they might relive their earlier feelings. Most said that they felt always the pain of having the ties of their girlhood and family belittled or ignored in their husbands’ homes. They spoke of the early years of marriage as a very vulnerable time, when they felt unattached, alone, lonely, homesick, even afraid. Choto Ma told me, “I sobbed and sobbed after my wedding. I couldn’t stand to be away from my father.” The “woman’s point of view” was not simply that the ties of a woman to her natal home could not be effaced, as Sax (1991:83) suggests, but rather that these ties were often gradually and painfully ignored and attenuated, even violated. Women even more than men were acutely aware of women’s tenuous relation to families and places—because they were the ones who most directly experienced the pain of having their natal substance devalued.

But as a woman lived in her marital home for many years, bore and raised children there, brought in daughters-in-law for her sons, experienced the births of grandchildren, and made friends among the other village wives, her ties gradually came to be more and more like a man’s, deeply embedded within one household and place. Most older women told me that even their lingering connections with their natal homes slowly faded, as they visited less and formed stronger ties in their marital homes (cf. Jacobson 1977:276–77). In telling her own life story, Choto Ma spoke of how a woman eventually “cuts the ‘link’” with her parents. “First she’ll cry a lot,” she said, “as I did. I sobbed and sobbed after my wedding.…But slowly you visit less, you cry less. And now, in old age, there is hardly any more connection with my father’s house.” A woman’s marital home would gradually become—in both her own eyes and those of others—no longer simply a śvaśur bāṛi, or “father-in-law’s house,” but her home. By old age, many women for the first time had gained a sense of an enduring emotional and substantial connectedness to one home, a sense of a rightful place there, and a concomitant degree of power and authority over others. In these ways—as in how the nature of their aging bodies was perceived—older women’s experiences and identities became, in significant respects, like men’s.

We have observed in this chapter how perceptions and experiences surrounding gender were complex, fluctuating, and multifaceted. Mangaldihi women’s and men’s experiences of gender over the life course make it clear that it would be highly misleading to think here of men and women, maleness and femaleness (and purity and pollution, power and powerlessness) as static and neatly opposing categories. This important point has been made by other recent feminist theorists. Sherry Ortner (1996:116–38) looks, for instance, at the intersections of class and gender in Sherpa society, arguing that “analysis focused through a polarized male/female distinction may produce distortions at least as problematic as those which ignore women and gender in the first place,” by masking the kinds of structural disadvantages that certain categories of men share with many women (p. 132). Chandra Mohanty (1991) similarly examines the problems (inherent in much Western feminist discourse) in positing a universal category of “women” and assuming a generalized notion of their subordination. Such an analytical move problematically “limits the definition of the female subject to gender identity, completely bypassing social class and ethnic identities” and the specificities of history, nation, and context (p. 64).[25]