Chapter I—

Valley of the Long Grasses

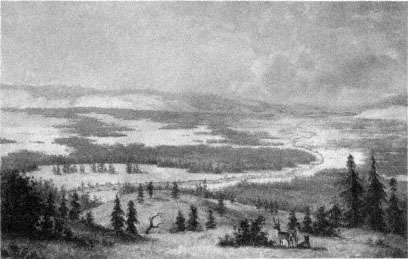

Prehistorically, the Willamette Valley's native peoples annually burned the valley floor to maintain a vegetative cover that provided foods necessary for their diet. This burning created in the valley large meadows interspersed with oak woodlands. Dense forests developed only in the foothills and along streams and rivers, where cooler and moister conditions prevailed, limiting the effects of fire. This was the Willamette Valley landscape that Canadian artist Paul Kane painted in 1847, before extensive white settlement (figure 1).

The natives' use of fire in the valley encouraged the vigorous growth of tall grasses such as tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa ), sloughgrass (Beckmannia syzigachne ), meadow barley (Hordeum brachyantheum ), and bluegrass (Poa pretensis ), some of which reached several feet in height. The native peoples called these long grasses kalapuya . When Europeans came to the valley of the long grasses, they used this Native American word to refer to the Willamette's people, thus dubbing them the Kalapuya.[1]

Mid nineteenth-century Euro-American settlers found long grasses probably the most striking feature of the Willamette and Calapooia Valley landscape and remembered them for many years:

In the early days the tall, rank grass covered all this valley. We would turn out our cattle on the valley and they would immediately be lost in the tall grass which reached higher than their backs. In looking for cattle it was impossible to find them by sight. It was necessary to listen for their bells, and when they were lying down to rest during the heat of the day, one might pass within a few feet without finding them.[2]

Figure 1.

Paul Kane, The Walhamette River from a Mountain . The Canadian artist Paul Kane

rendered this painting of the mid Willamette Valley about thirty miles south of Oregon

City in early January 1847. The painting shows extensive prairies interspersed with large

patches of forest; no Euro-American settlements are shown. The middle and northern

portions of the Willamette Valley had more extensive forested areas than did the southern

portion, where the Calapooia is located. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Long grasses composed only one environmental element of the Willamette and Calapooia valleys that natives and nature wove together into a complex landscape. Understanding the natural history of this landscape, and the effect of the Kalapuya people on it, is requisite to comprehending the drama Euro-American settlers staged on it after their arrival in the mid nineteenth century.

Natural History

Some fifty million years ago, the Pacific Northwest had a tropical climate. At that time, the landmass that later became the Willamette Valley lay completely submerged under the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean, whose tides lapped at the base of the ancient western Cascade Mountains. Roughly thirty million years ago, the ocean's waters began to subside to the west as huge basalt flows and folding and faulting uplifted new mountains, the Coast Range, from the floor of the Pacific.

The submerged Willamette Valley now lay between two mountain chains, acting as a catch basin for eroding sediment. During the next twenty-five million years, the Willamette Valley landmass slowly rose, the inland sea that covered it drained, and the present river valleys formed (map 1).[3]

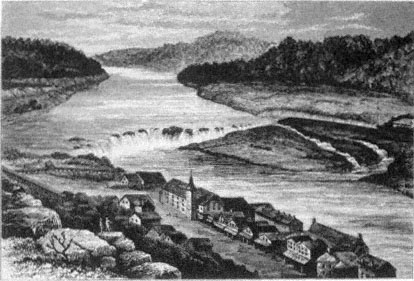

About ten million years ago, basalt lava flowed and solidified across the northern outlet to the valley. The relatively modest flow of the Willamette River has been unable to breach this impediment, and thus over the millennia rich river alluvia of clay, silt, sand, and gravel collected behind it in the huge trough that is now the Willamette Valley. The ancient basalt flow forms a cliff over which the Willamette River plunges some fifty feet (figure 2).[4]

Roughly one million years ago, the earth's surface cooled, creating in North America a continental ice sheet that spread southward from the Arctic zone into the northernmost reaches of the Pacific Northwest. In high mountainous zones of the region, such as in the Cascades east of the Willamette, large alpine glaciers formed. Although these glaciers did not descend to the Willamette Valley lowlands, streams issuing from them carried yet more sediment down to the valley. At the end of this cool cycle, glaciers and the continental ice sheet retreated, releasing huge quantities of water and inundating the entire Willamette Valley with inland seas up to one hundred feet deep. By the time of the next glacial advance some sixty thousand years ago, however, the Willamette had once again been drained of its waters.[5]

During this next ice age, the advancing continental glacier dammed a fork of the Columbia River far to the northeast of the Willamette Valley, in what is now northeastern Washington and northern Idaho. Behind it formed a large lake. Several times as this ice sheet retreated, weakened, and broke before forming again, huge floods swept down the Columbia River. Because precipitous banks restricted the Columbia's flow downstream from its confluence with the Willamette River, floodwater carrying chunks of glacial ice washed all the way back to the southern portion of the Willamette Valley. Each time floodwater backed up into the Willamette, it destroyed the natural vegetation and deposited huge amounts of silt and even some large boulders.[6]

While the land was still marshy, only slowly draining from this cycle of flooding, a warming and drying period in the climate encouraged the growth of tree species such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii ), Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis ), and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla ) in

Map 1.

The Willamette Valley.

Figure 2.

Willamette Falls, 1878. Source: Wallis Nash, Oregon: There and Back in 1877 .

higher areas and along the edges of the Willamette Valley. On the well-drained foothills surrounding the valley grew grand fir (Abies grandis ) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa ).[7]

Beginning about eleven thousand years ago and continuing until about four thousand years ago, the Northwest's climate became yet drier and warmer. During this period, marshlands and lakes on the Willamette Valley's floor receded farther, more grasses appeared, and the more drought-tolerant western white oak (Quercus garryana ) and California black oak (Quercus kelloggii ) became the dominant tree species. Today, western white oak naturally occurs from Vancouver Island south into California's central valleys, and thus grows throughout the Willamette. The California black oak's range, however, extends only as far north as the very southern portion of the Willamette Valley. It does not occur naturally north of there.[8]

About six thousand years ago, the valley became dry enough to inhabit, and humans descended to the valley floor from the surrounding hills, which they had occupied for at least two thousand and possibly as much as four thousand years.[9] Although these people did not know it,

their very act of moving from foothills to valley floor revealed a tension between human occupation and the natural features of the Willamette's landscape. Recognizing this tension, especially with regard to the role of foothills and valley floor, is central for understanding the life and thought of nineteenth-century Euro-American settlers.

Two thousand years after humans arrived on the Willamette's floor, the climate again changed, initiating a cooler and moister pattern that has persisted up through and beyond the arrival of Europeans in the Pacific Northwest at the end of the eighteenth century. This climatological pattern has continued to the present, though indications are that the Willamette Valley, like much of the West, is entering another drying and warming period. During the last four thousand years, a strong marine influence has marked the region's climate. Winters are especially wet, though coastal mountains to the west protect the valley from severe winds and driving rains that blow in from the ocean. Storms coming in off the Pacific drop much of their precipitation as they pass over the coastal chain. The valley, left with gentle yet persistent rains that fall from mid autumn to late spring, receives as little as thirty inches of rain on the Coast Range's eastern slopes, but as much as sixty inches along valleys such as the Calapooia that reach back into the foothills of the Cascade mountains on the eastern margin of the Willamette. As the warm, wet winter winds push up the high Cascades, they cool and drop their remaining moisture as rain and snow in annual amounts of up to 120 inches. The Cascades also act as a cordon against the dry, frigid continental winds that influence the winter over much of the North American landmass to the east of the Willamette. This barrier, coupled with the Pacific's warm winter storms, keeps valley temperatures moderate in winter, with a mean of forty degrees Fahrenheit during the coldest months. Snow does occasionally fall on the valley floor, though it rarely lingers. The predominantly southwest winter winds off the Pacific shift to the north in late spring, bringing a drier and warmer period when little if any precipitation falls and the mean temperature reaches sixty-seven, with occasional hot spells resulting in daily temperatures of over one hundred. This pattern continues until the rainy season begins again in mid autumn.[10]

Precipitation falling on the Willamette's bordering foothills and mountains eventually finds its way to the valley floor, whose great expanse slopes gently, almost imperceptibly to the north. Native Americans and early European settlers witnessed how the absence of relief in

the Willamette Valley forced streams, creeks, and rivers, after breaking out of the foothills, to meander sluggishly across the valley in a series of braided channels, oxbows, sloughs, and sandbars, depositing their sediments on banks that rose slightly above the surrounding plain. Choked with debris, vegetation, and mud islands, streams and rivers of the Willamette often overflowed onto nearby flood plains, leaving standing water for many months of the year. Lack of relief and drainage, coupled with occasional winter snows in the valley and foothills that melt quickly, caused major floods at least every tenth season, sometimes as often as every fifth season during prehistoric times.[11]

This moderate, seasonally moist climate, along with the marshy conditions that have characterized the Willamette Valley for four thousand years, has in large part determined the flora that grow there and that greeted the earliest Euro-American settlers. These first settlers found along the Willamette River and its tributaries on the flat valley floor extensive gallery forests—often up to two miles wide—composed of Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia ), cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa ), willows (Salix spp.), red alder (Alnus rubra ), and bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum ), with Douglas fir and western red cedar (Thuja plicata ) sprinkled throughout. Along smaller streams such as the Calapooia, the gallery forests narrowed. Along the foothills of the Willamette Valley flourished Douglas fir, grand fir, ponderosa pine, and incense cedar (Calocedrus decurrens ), with western hemlock and western red cedar thriving in moister and cooler yet well-drained areas along upper foothills and streams. Hardwood trees such as bigleaf maple, western white oak, and madrone (Arbutus menziesii ) also grew in the foothills. Their understory consisted of shrubs such as hazelnut (Corylus cornuta ), ocean spray (Holodiscus discolor ), and snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus ), and along prairie edges, smaller plants such as cheat grass (Bromus vulgaris ), Oregon grape (Mahonia nervosa ), and tarweed (Madia spp.). Between the foothills and the gallery forests of the Willamette Valley grew extensive meadows composed mostly of grasses, flowers, and scattered oak trees, or oak savanna.[12]

Ecologists apply the term climax to the theoretically highest stage of ecological succession, or evolution, of a plant-animal community or ecosystem. At climax, the ecosystem is stable and self-perpetuating. Climax does occur in nature, but other natural factors, such as disease and fire, limit the stability, persistence, and extensiveness of a climax community. Had the Willamette Valley been left to "nature," its gal-

lery and foothill forests of maple, Douglas fir, and grand fir would theoretically have eventually covered the valley floor as a climax community. However, the Native American inhabitants of the Willamette, in order to ensure an abundance of the plants and animals essential to their diet and culture, used fire to keep the valley's flora in a fire-maintained subclimax state of grasslands and oak groves for hundreds of years.[13]

The Kalapuya

The Kalapuya traditionally occupied the Willamette Valley between the basalt cliff forming the falls in the north to the Umpqua River basin bounding the south. Ethnologists divide the Kalapuya into three distinct groups. The Tualatin-Yamhill Kalapuya occupied the northern valley, the Yoncalla lived in the south into the Umpqua region, and the Santiam-McKenzie inhabited the greater portion of the central and southern Willamette. Ethnologists have further divided each of these main groups into smaller tribelets or bands that occupied separate tributary valleys to the Willamette, such as the Santiam, Luckiamute, Long Tom, McKenzie, and St. Mary's. Each of these bands spoke a slightly different dialect of the Kalapuya language. Along the banks and in the valley of what Euro-Americans dubbed the Calapooia River lived the people who spoke a dialect that linguists call Tsankupi. It must be pointed out that all dialects were fairly similar because of close contact between bands and because all lived in a landscape that was almost uniform throughout the valley of the long grasses.[14]

The Kalapuya have posed a special problem to anthropologists who attempt to categorize Native American cultures. Although the Kalapuya occupied a near-coastal environment, they depended on plants rather than fish and other seafood as a staple; thus, they occupy a place on the cultural spectrum overlapped by the Northwest Coast and Columbia River Plateau groups. Anthropologists have perhaps best described the Kalapuya culture as a modified blend of "primitive river phase" and "grassland" because of the nature of the Willamette Valley, which has both abundant streams and rivers and extensive prairies.[15]

Though historians and ethnologists have debated the point, the best analysis places the maximum Kalapuya population at about 13,500, or very roughly fifty people per one hundred square miles, during the last

quarter of the eighteenth century. The availability of food, partly determined by the environment, limited the size of the Kalapuya population. The Kalapuya relied primarily on plants, less so on game, and almost not at all on fish. Plant resources of the Willamette provided a diet that was less varied and less nutritious than were the diets of other Northwest Coastal groups, such as the Kalapuya's northern neighbors the Chinook of the Columbia River and the Coastal Salish of Puget Sound. These latter two groups relied principally on relatively abundant and nutritionally rich salmon and other forms of sea life, which could support larger and more densely concentrated human populations. The Chinook and Coast Salish populations reached densities of perhaps four hundred people per one hundred square miles. Conversely, the Willamette environment provided more abundant food sources than did the desertlike Columbia Plateau and the desert Great Basin regions east of the Cascades. In the most extreme case, the Northern Paiute of the Great Basin may have reached a population density of only five people per one hundred square miles.[16]

On first consideration, it might seem surprising that, unlike other Northwest Coastal peoples, the Kalapuya did not rely on salmon and other fish for sustenance even though through their backyard flowed the Willamette River, which is, in terms of water volume, the tenth largest river in the United States. During prehistoric and much of early historic times in the Northwest (until Euro-Americans introduced fish ladders), few salmon actually came to the upper Willamette River because the basalt cliff on the very northern course blocked them from entering the valley. Only the smaller run of spring chinook could negotiate the falls, because at that time of year increased water flow from rain and melting snows allowed the strongest salmon to swim over the barrier. The much larger fall run of chinook and silver salmon, the latter of which migrate only in the autumn, returned to the Northwest's streams after the long, dry summers, when low water flow prevented them from negotiating the falls of the Willamette. Furthermore, the powerful Chinook tribe, the Kalapuya's neighbors to the north, controlled access to the falls, preventing other groups from harvesting any of the returning spring salmon.

Charles Wilkes, an explorer from the United States Navy, visited a Hudson's Bay Company trading post at the falls on 5 June 1841 and recorded in his journal the following observations about the Chinook fishing operation:

At the time of our visit to the falls, the salmon fishery was at its height, and was to us a novel as well as an amusing scene. The salmon leap the falls; and it would be inconceivable if not actually witnessed how they can force themselves up, and after a leap of from ten to twelve feet retain their strength enough to stem the force of the water from above. About one in ten of those who jumped succeed in getting by. . . . I never saw so many fish collected together before; and the Indians are employed in taking them.

The Chinook did, however, allow the Kalapuya to gather eels that clung to the basalt cliffs behind curtains of cascading water. The Kalapuya also collected eels and fished for salmon at smaller waterfalls and rapids on the Willamette's tributary streams, such as the falls on the Calapooia. Often they fished at night, by the light of pitchwood torches, and took their catch back to camp to preserve it for winter storage through drying and smoking. In their fishing the Kalapuya used bone-tipped spears, woven basketwork traps, weirs, and fishing poles with hair for string and grasshoppers for bait. But again, this food source played a relatively limited role in the Kalapuya's diet.[17]

Instead, the Kalapuya relied on plants, vegetable produce, and, to a lesser extent, wild game. To maximize food and natural resources in an environment not as naturally abundant as the lower Columbia River and the coast, the Kalapuya followed a seasonal routine, moving through a variety of task-specific sites and manipulating the environment through the use of fire to ensure the availability of food and other resources necessary for their culture. In late summer, when a number of other Pacific Northwest tribes congregated at fishing sites to harvest salmon, the Kalapuya converged on the dry Willamette Valley meadows to set fire to its grasses in order to encourage the growth of camas (Camassia spp.), the staple of their diet. Camas, a member of the lily family, requires open prairie habitat. Because geographical and climatological factors make lightning strikes in the Willamette rare, the valley would naturally have become overgrown with forest, and the camas would have become extinct. But the Kalapuya's intentional burning of the prairies at the end of each summer eliminated the camas's competition: shrubs and the seedlings of climax species such as Douglas fir and bigleaf maple. Since the bulb of the camas lies hidden underground and dormant at the end of summer, fire cannot directly affect this vital portion of the plant. During the following spring, the bulb multiplies and sprouts, sending up tall green shoots with spikes of purple, blue, and sometimes white flowers. Grass buds, also underground and thus

also protected from fire, sprout in fall and grow during the mild winter and spring, but provide no competition for the camas.[18]

David Douglas, an English botanist who arrived in the Willamette Valley in the autumn of 1826, noted of the aftermath of burning, "Most parts of the country burned; only in little patches and on the flats near the low hills that verdure is to be seen." A few days later he commented, "As I walked nearly the whole of the last three days, my feet are very sore from the burned stumps of low brush-wood and strong grasses." Not only did the earliest European and Euro-American visitors and settlers in the Willamette Valley remark on the immediate effects of the Kalapuya's use of fire, but they also left records of the actual process and scene of burning. On 15 September 1841, W.D. Brackenridge noted as he traveled out of the southern Willamette Valley, "day very fine but dense with smoke from prairies in vicinity." Jesse Applegate, nephew of the more famous settler by the same name, left the following description of his family's encounter with one of the last of the Kalapuya burnings, which occurred in the early 1840s:

This season the fire was started somewhere on the South Yamhill, and came sweeping up through the Salt Creek gap. The sea breeze being quite strong that evening, the flames leaped over the creek and came down upon us like an army with banners. All our skill and perseverance were required to save our camp. The flames swept by on both sides of the grove; then quickly closing ranks, made a clean sweep of all the country south and east of us. As the shades of night deepened, long lines of flame and smoke could be seen. . . . On dark nights the sheets of flame and tongues of fire and lurid clouds of smoke made a picture both awful and sublime.[19]

By burning the Willamette Valley, the Kalapuya altered the environment, prevented the growth of dense and continuous forests, and maintained a subclimax ecosystem of extensive grasslands and broad camas prairies. These grasslands also supported a variety of wildflowers: larkspur (Delphinium spp.), cranesbill (Geranium dissectum ), yarrow (Achillea millefolium ), aster (Aster spp.), scarlet gilia (Gilia sp.), monkeyflower (Mimulus spp.), poppy (Eschscholzia californica ), buttercup (Ranunculus spp.), tarweed (Madia spp.), balsam root (Balsamorhiza sagittata ), and narrow-leafed mule's ear (Wyethia angustifolia ). Thickets or small forests of fir and maple still flourished in isolated patches throughout the valley, usually on the cooler and moister northern slopes of buttes and hills and often along river and stream banks. The northern Willamette, slightly wetter and much more hilly than the very

flat and open southern portions of the valley, had more densely forested areas. And, of course, trees grew profusely on the valley's surrounding foothills.[20]

The point where two or more ecosystems—such as a prairie and a forest—intersect is a transitional zone ecologists call an edge or ecotone . Edges support the most diverse biological populations of the environment because plant and animal species native to both ecosystems and the transitional zone itself can be found there. At the edge between forest and prairie ecosystems, furthermore, waterflow from springs improves, and here, too, grow a profusion of transitional species of woody shrubs whose sprouts make up the primary food source for deer, which tend to be browsers rather than grazers. The Kalapuya consciously preserved edges both to support white-tailed and blacktailed deer populations and to concentrate them in certain areas to make hunting easier. Douglas noted, "Some of the natives tell me it is done for the purpose of [indu]cing the deer to frequent certain parts to feed, which they leave unburned." Lewis Judson wrote, "These fir groves had been found necessary by the Indians to induce deer and other wild game to stay in the valley. The groves were undisturbed by fire. . . . The Indians burned right up to imaginary lines, but never was the fire allowed to go past or get out of hand. So some authority existed among them because biennially the prairies were burned."[21]

Burning the Willamette Valley also increased production of acorns, another important component of the Kalapuya diet. Fire has little effect on mature western white and California black oak trees, whose corklike bark resists relatively cool ground fires fueled only by dead grass and low-growing shrubs. Charles Wilkes noted the resistance of oaks to fire when he sojourned in the Willamette in September 1841: "The country had an uninviting look from the fact that it had lately been overrun by fire, which had destroyed all the vegetation except the oak trees, which appeared not to be injured." Oak trees dotted the grasslands of the valley in groves or as single stately trees. The natural growth habits of oaks and their constant subjection to fire prevented them from forming extensive, densely canopied forests in the valley. Without competition from other trees, oaks produce not only more leaves but more acorns as well. And burning grass cover in late summer allowed natives more easily to find ripe acorns that had fallen beneath the trees. The Kalapuya thus resembled the natives of the central valleys of California, who also depended on the acorn as their staple.[22]

The Kalapuya used fire in other ways, too. For instance, they used it as a tool of the hunt. In a practice called the battue , Kalapuya men encircled a parcel of territory and set a ring of fire; as the flames came together, so, too, did game animals, trapped within the walls of fire. When the circle of fire became smaller yet, hunters entered the ring and selectively shot game. Natives performed the battue at the end of summer and beginning of fall, when deer are fattest and healthiest and grasses and brush driest. But the Kalapuya carefully did not overhunt those animals they considered best for breeding purposes. Two Kalapuya men recalled, "They preserved the best males, the very young and best animals, with care. They could always find enough to answer their purposes without exterminating the game."[23]

The Kalapuya also employed fire to clear and fertilize land for the growing of tobacco, which was their only cultivated crop in the modern sense. Douglas reported, "An open place in the wood is chosen where there is dead wood, which they burn, and sow the seed in the ashes. . . . Thus we see that even the savages on the Columbia know the good effects produced on vegetation by the use of carbon."[24] Douglas, a product of European culture, looked down on the Kalapuya as inferior, but his own evidence supports the fact that these people had a deep awareness of the environment and the ways to alter it for their continued benefit.

Though camas was the staple of the Kalapuya diet, one of this people's strategies for survival in the Willamette was not to depend wholly on one or a limited number of foods. Thus, they also collected acorns and more than fifty other plants, including wappato (Sagittaria spp.), a kind of tuber that grew along lake shores in the northern valley. Again, fire aided the Kalapuya in collecting these foods. For instance, it parched the heads and pods of sunflowers such as balsam root, Wyethia , and tarweed, making their seeds easily shaken loose and collected. The Kalapuya also included a variety of animals and insects in their diet, such as grasshoppers, whose baked bodies they collected after burning. And prairie burning enhanced habitat for game animals other than deer. Shortly after the fires of late summer and early autumn, rains returned to the Willamette, encouraging grasses to green up in the burned-over areas. Elk, moving down from mountains at this time, and migrating geese, swans, ducks, and other fowl in both fall and spring concentrated to graze on and feed among these fresh young grasses. This concentration made hunting much easier. In addition to this game,

other meat sources for the Kalapuya included beaver, river otter, muskrat, black bear, cougar, bobcat, rabbit, squirrel, and raccoon. The Kalapuya's diversity of food sources guaranteed security.[25]

The Kalapuya maximized resources for their survival through burning and reliance on a great variety of foods. Both these strategies made up components of their larger, complex approach to survival: seasonal movements. In moving seasonally to different ecosystems of the valley and surrounding hills and mountains, the Kalapuya avoided relying on, and thereby overusing, certain food sources. The Kalapuya also moved to various sites to gain access to a wide variety of animals and plants that provided other materials necessary for their culture. Different seasons and landscapes provided different types of food and resources.

In winter the Kalapuya congregated in seasonally permanent villages located among willow, maple, and cottonwood thickets that bordered large streams such as the Calapooia. There they occupied large, rectangular, cedar bark and plank lodges, architecturally similar to the cedar plank houses of other coastal tribes from northern California to southern Alaska. Since western red cedar did not grow in some of the drier parts of the valley, the Kalapuya often substituted brush, mats, and bark as construction materials. Inside these lodges, the Kalapuya excavated floors of several feet in depth for hearths, drying racks, and cooking utensils. They arranged sleeping quarters along the edge of the lodge. Each lodge housed several related families and a group leader. All members worked together on tasks of hunting, gathering, and childcare. During winter occupation of villages, the Kalapuya engaged in storytelling and produced mats, baskets, and winnowing trays from tules, cattails, and beargrass while they lived off reserves stored up during the preceding seasons.[26]

In the springtime, the Kalapuya harvested camas and hunted migratory fowl. As was typical of the sexual division of labor found among other Native Americans, Kalapuya women performed all the plant collection and preservation while men hunted. In the spring, women moved out from the winter villages onto the broad floodplains of the Willamette Valley, where they dug camas with wood and bone tools. Spring proved the best time for camas collecting for a number of reasons. First, at the end of winter the plains of the valley, largely composed of clay, are saturated, and digging is much easier than it is later in the summer, when the soil dries and hardens. Second, death camas (Zigadenus venenosus ), a poisonous plant, occasionally grows among

the edible camas. By digging in spring and early summer, the blooming seasons, the Kalapuya could differentiate between the two plants' distinctive blossoms. Once the camas bulbs were collected, women preserved them by baking them in huge earthen ovens between alternating layers of hot rocks and coals, maple leaves, and soil; they then stored the bulbs in earthen pits for winter months. Meanwhile, men hunted migratory fowl, which returned to the valley at this time.[27]

In the summer, large portions of the native population retreated to the foothills. There men hunted with bow and arrow, pitfall traps, and snares, and women preserved hides and furs of captured game. They also picked and preserved ripening wild cherries (Prunus emarginata ), elderberries (Sambucus cerulea and S. rocemosa ), huckleberries (Vaccinium parvifolium ), salmonberries (Rubus spectabilis ), thimbleberries (Rubus parviflorus ), hazelnuts, and bracken (Pteridium aquilinum ), patches of which the women burned at the end of the season to ensure vigorous growth and production the following year. At sites adjacent to streams in the foothills, the Kalapuya worked oak, yew (Taxus brevifolia ), and cedar boughs into tools. At the end of summer, they moved back down to the floor of the Willamette for annual prairie burning, acorn collecting, seed harvesting, and deer hunting. In the autumn, migratory fowl flocked through the valley once again, providing men another opportunity for hunting. As this season ended, the Kalapuya once more took up residence in their winter dwelling villages, and the cycle began anew.[28]

Within natural limits, the Kalapuya altered the environment of the valley of the long grasses. But relative stability marked the environment they and nature created, and thus their relationship to it. The Kalapuya's continuous cycle of seasonal movements among various ecosystems of the valley is one indicator of stability in the human-environmental relationship. Other evidence is seen in the fact that the Kalapuya took and stored not more than they needed to make it through the year, thus ensuring a relative balance between themselves and nature.

The stability of the environment and human-environmental association is also manifested in the Kalapuya's intellectual or spiritual relationship with the landscape and its other inhabitants. Native American novelist N. Scott Momaday has pointed out that in the native mind "nature is not something apart from him. He conceives of it, rather, as an element in which he exists." Thus, landscape to the Kalapuya was

more than just individual components of weather, contour, vegetation, and wild animals that were external to themselves as people and that played roles in their survival. these ingredients of the environment shared a deep kinship with the Kalapuya people, both physically and spiritually. In the Atfalti Kalapuya's four-phase creation story, for example, Crow, Dog, Moon, Sun, and trees play various roles as progenitors to humans, who themselves become elements of the universe: stars, pebbles, and clouds.[29]

The spirit quest—the central event in the life of a Kalapuya—demonstrates best the shared bonds between these people and the environment. The spirit quest marked the passage from childhood to adulthood for boys—and in many bands, girls, too. A boy who wished to become a shaman sought his spirit power in the natural world:

He was always swimming in the early morning. And when it would become dark at night and the moon was full, then he would go to the mountain. He would fix up that spirit power place on the mountain. He would go five nights. Always in the early morning he would be swimming. And then he would find his spirit power. While he slept he would see the dream-power, his spirit-power. That is how he did all the time.

This particular story shows the important role that inanimate fixtures of the landscape, such as water and mountains, played in the psychological quest of a young Kalapuya. In addition, the spirit powers a Kalapuya could gain during this quest all derived from the natural environment. For example, one Yamhill Kalapuya man's "spirit-power was thunder, when thunder roared, and when it rained down quantities of water. And another too of his spirit-powers, his spirit-power was deer they say." Others derived spirit power from various animals who played key roles in mythology. The coyote was a trickster, the fly a tattletale, the cougar a hero, the bobcat a heroine, the raccoon a miser, the elk a water monster, and the spider the protector of women; the eagle aided the grizzly, which was considered a villain and which crows, gray squirrels, and dogs worked together to deceive.[30]

In Kalapuya myths, furthermore, animals play central roles in the origin of landscape. One tale relates how Meadowlark and Coyote created the waterfall on the Willamette River at the northern end of the valley. They took a rope between them and stretched it tight:

Coyote pulled hard. Meadowlark pulled with all her strength and pressed her feet against the rock she was standing on. Then Coyote called on his powers and turned the rope into a rock. The river poured over the rock. . . .

Meadowlark pressed her feet on the rock so hard that she made footprints. Her footprints stayed there for hundreds and hundreds of years.[31]

Creation stories, spirit quests, and myths reveal the Kalapuya's intellectual relationship with the natural environment. Simply, they saw humans, animals, and land interconnected.

Momaday's assertion and the intellectual evidence of the Kalapuya's myths, combined with the ecological, biological, and anthropological record, strongly suggest that the Willamette Valley of the Kalapuya was a relatively stable, self-perpetuating, and therefore balanced culturalecological community. Europeans and Euro-Americans began to arrive in the Willamette region around 1800. They introduced into this environment new pathogens, new plant and animal species, a linear conception of time, and a new intellectual relationship with nature. The cultural-ecological balance the Kalapuya had achieved was soon destroyed, releasing incredible natural energies and creating a new cultural-ecological community of relative instability. The psychological and biological effects of this instability on Euro-American settlement and community are the subject of the greater portion of the remainder of this book.

The Kalapuya, like so many other native peoples of North America, met with a tragic demise after their contact with Europeans. Destruction of native North American populations came in different ways. The quickest mechanism was exposure to European diseases for which Native Americans had no immunities. Another, subtler mechanism was the result of European disruption of native economies and cultural practices. Natives who engaged in the fur trade, for instance, easily adapted to and became dependent on European trade goods, tools, guns, blankets, and sometimes food; when a disruption, such as a depression, occurred in the economy, natives were no longer able to acquire those goods to which they had become accustomed. This deprivation often resulted in starvation. Cultural practices were also thrown into disorder when European or Euro-American settlers took important food-gathering sites from natives or turned loose their livestock to graze and root on those sites.[32]

All these factors played a role in the demise of the Kalapuya, but disease had the greatest effect. The first epidemic to plague the Northwest was smallpox, which swept westward from the Midwest in 1782–83. After ravaging the more densely populated coast and lower Columbia River, the disease moved inland and attacked the Kalapuya. Vene-

real disease spread inland from the mouth of the Columbia in the 1790s, after the first explorers' ships arrived. The Kalapuya began to gain back some of their population before the most devastating epidemic struck them between 1830 and 1833. This epidemic was classically known as "fever and ague," but it is now believed to have been malaria, which Europeans imported on their ships that visited the Hawaiian Islands before arriving in the Northwest. In the early nineteenth century, the Willamette Valley's great expanses of marshes and its few lakes, such as Labish and Wapato, ideally suited it for the breeding of malaria-infected mosquitoes. In addition, some scholars have pointed out that two cultural habits of the Kalapuya exacerbated the spread and severity of the disease. First, their food-gathering patterns and techniques brought them into mosquito-infested areas of the Willamette. Second, the Kalapuya's traditional treatment for illness—sweating in lodges followed by jumping into cold water—only quickened their demise, for pneumonia often followed.

As early white settlers recalled, the Kalapuya also used this method of therapy to treat other diseases brought by Europeans: "When the measles broke out among the Indians near the Morgan claim [on the Calapooia River] they treated the disease in their traditional manner by sweat-houses and a plunge into the cold water of the creek. That, of course, was fatal. My people tried desperately to persuade them to do differently but it was no use." This same informant added that the Kalapuya's "customs were too strong for a white man's argument to nullify. As a result a great percent of the village died."[33]

Estimates suggest that between 1830 and 1833 as many as six thousand Chinook and Kalapuya died along the lower Columbia and lower one hundred miles of the Willamette. Malaria continued to plague the valley in pockets through the early 1840s, and in the 1830s other epidemics and diseases, such as dysentery, tuberculosis, and venereal infections, spread among the natives. It must be stressed that not all deaths resulted directly from disease. Even if only a small portion of a village or band contracted an illness, the reduction in numbers could disrupt seasonal movements, burning practices, and everyday activities, leaving uninfected children and adults unable adequately to perform duties required for daily and winter survival. Often starvation resulted. Both directly and indirectly through the effects of disease, the Kalapuya's demise was nearly complete by the mid 1840s. Methodist-Episcopal missionary Daniel Lee, nephew of Jason Lee and cofounder of the Meth-

odist Mission built in the mid Willamette Valley in 1834, remarked "there are only a few most miserable remnants left . . . and are scattered over the most part of the Walamet Valley, and will not number more than from 500 to 800." Estimates indicate that by 1841 only six hundred Kalapuya survived in the valley, and by 1844 this number had been cut in half.[34]

Evidence also suggests that disruption of the Kalapuya culture came through contact with the European/Euro-American economy and through actual settlement. These factors, however, had only a limited effect.[35] James L. Ratcliff's "What Happened to the Kalapuya?"—the only study to date on the subject—relies on evidence from the year 1838, five to six years after the worst of the malaria epidemic had already wiped out the greatest number of Kalapuya. Ratcliff claims that in that year the fourteen French families (retired employees of the Hudson's Bay Company) who had permanently settled in the Willamette Valley (the only settlement at that time other than a mission) had "reduced the camas acreage on the prairies of the valley" to the point that they had "deprived the Kalapuya of their vegetable staples." In reality, the French settlement covered a relatively small area of the very northern Willamette Valley. The settlers had enclosed 700 acres and cultivated another 550—an area of about two square miles. The settlement also had livestock, 400 hogs and 150 horses, which roamed about the local area. Although the French settlement undoubtedly had an influence on the local camas prairies, it had no impact on the great expanse of the Willamette Valley to the south.

In addition to this evidence of settlers affecting only one small locale at most, Ratcliff argues that the three gristmills on Willamette Valley's rivers and streams in 1838 significantly undercut the Kalapuya's fishing. In fact, though, the mills probably had no effect on the Kalapuya. One mill was located on Willamette Falls, which, as demonstrated above, played no vital role in their food gathering. And no mill existed at this time in the southern Willamette. In addition, the Kalapuya diet relied very little on fish. The effect of the fur trade in the Willamette is also unclear. The Willamette never produced large quantities of beaver, and trapping there was, as Ratcliff notes, conducted primarily by European trappers themselves and not the Kalapuya. Trappers undoubtedly traded with some Kalapuya, drawing them into the European economy, and trappers may have competed with Kalapuya for game, but such a small number of trappers would have had negligible impact. In minor

ways, the fur trade and settlement that came at the end of the malaria epidemics undoubtedly affected the cultural practices of the few remaining Kalapuya. But evidence of debilitating diseases provides the best answer to the question of what caused the cultural disruption and death of these people.

An interesting point, however, is that the Kalapuya viewed the tragedy of their destruction as the result not of disease but of the changes in the landscape caused by European and Euro-American settlers. One of the Kalapuya tales from this time shows that they attempted to explain what happened to them as the fulfillment of a shaman's prescient dream: "Long ago the people use to say that one great shaman had seen . . . all the land black in his dream. 'This earth was all black (in my dream).' . . . Just what that was he did not know. And then (later on) the rest of the people saw the whites plough up the ground. Now then they said, 'That must have been what it was that the shaman saw long ago in his sleep.'" After the destruction, the few remaining Kalapuya looked back to the past with lamentation: "This countryside is not good now. Long, long ago it was good country (had better hunting and food gathering). They were all Indians who lived in this countryside. Everything was good. Only a man went hunting. . . . Women always used to dig camas, and they gathered tarweed seeds."[36]

Because the Kalapuya had no written tradition, we have only limited sources from their perspective on their interaction with Euro-American settlers. None relates battle with disease. Folklorists note that the stories of a people relate that which is most significant about their experience. Although the central role of disease in the demise of the Kalapuya is unquestionable, the wider implications of their experience is best captured in their own stories. It is clear that what was most significant to the Kalapuya was their loss of connection with the land, at the hands of settlers, on both the psychological and physical levels.

Though the Kalapuya had all but vanished by the commencement of extensive white settlement in the 1840s, the landscape that they and nature had created remained. Obviously, once the Kalapuya disappeared from the valley, the environment of the long grasses underwent a drastic change. But during the last days of the Kalapuya and the first days of European and Euro-American presence, the landscape of the Willamette appeared much as it had for hundreds of years. This appearance and actual physical nature captivated European and Euro-American explorers. It greatly influenced their early perceptions of and

ideas about the relationship between themselves and the landscape of the valley, setting the foundations of settlement culture that influenced life and thought during the remainder of the nineteenth century.

Early Observations

The first recorded observations about the Willamette landscape and environment come from European and Euro-American fur trappers, settlement promoters, and official and unofficial explorers between 1811 and the early 1840s. The latter arrivals in this group often coincided with, and were sometimes linked to, the actual settlement of the valley. Not surprisingly, the reasons these observers had for journeying to the Willamette Valley conditioned their responses to it. All recorded descriptions of the valley can, to varying degrees, be categorized as comments on either its wilderness/primitive values or its pastoral/garden image, the two primary ways, according to Leo Marx, that early and mid nineteenth century Americans and Europeans assessed the environment.[37]

On one end of the spectrum, early observers perceived the Willamette as a wilderness and its inhabitants as uncivilized or primitive. For example, trained botanist David Douglas recognized that the Kalapuya had in some ways modified the Willamette's environment, but the nevertheless viewed them as "savages." In 1841, the American explorer Charles Wilkes, while ascertaining the strength of the British and the prospects for American settlement in the disputed Oregon Country, compared the Willamette's landscape to a domestic pastoral scene; he described the foothills of the southern Willamette as "destitute of trees, except oaks," which appeared "more like orchards of fruit trees, planted by the hand of man than groves of natural growth, and serve to relieve the eye from the yellow and scorched hue of the plains." He added, however, that no mistake could be made about the oaks' domestic state, for the groves were interspersed through great stretches of "wild prairie-ground." In this passage, Wilkes shows his failure to understand the beautiful landscape he beheld, for, although the oak groves were not exactly cultivated orchards, neither were they "natural." Wilkes, like Douglas, knew that the Kalapuya used fire on the valley floor, but he did not consider that fire both gave the oaks their orchardlike appearance and created what he described as "wild prairie."[38]

Wilkes's observations also reveal a central tension, even dichotomy, in the way European and Euro-American commentators perceived the

environment of North America generally and the Willamette Valley specifically. Wilkes noted the wildness of the Willamette, but he also, often within the same passages, saw the environment in pastoral terms, as a product of the "hand of man."

Others who, like Wilkes, had political or economic stakes in the future of the Willamette Valley described it in similar terms—either as a pastoral setting in its present condition or as a landscape suitable for the cultivation of a garden. Early French-Canadian settler Francis Xavier Matthieu, for instance, compared the Willamette to a pastoral scene when he noted that the country of the French settlement was in the "condition of a park." And Wilkes's British counterparts Henry Warre and Mervyn Vavasour wrote in the 1840s that the valley offered "a field for an industrious civilized community."[39]

In The Machine in the Garden , Leo Marx discusses how Americans' concept of the pastoral changed over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the end of the first half of the nineteenth century, when industrialization—which could be antithetical to the pastoral ideal—had definitely begun to make a mark on the landscape, Americans had broadened their definition of the pastoral to make allowance for the encroachment of "the machine" into the garden. In the Willamette Valley, evidence from the group of observers to which Wilkes, Matthieu, Warre, and Vavasour belonged demonstrates that they had accepted at least the role of industrialism in their pastoral conception by the 1840s. For instance, American immigrant promoter and settler Joel Palmer stated that the "small mountain streams" that crossed the southern portion of the valley had "valuable water privileges for such machinery as may be erected, when yankee enterprise shall have settled and improved this desirable portion of our great republic."[40]

On the other end of the pastoral-primitive spectrum from the group to which Wilkes and Palmer belonged were those who came to the Willamette Valley without economic or political stakes in its future and who thus looked on its scenery differently. David Douglas, whom the British Royal Horticultural Society sent to the Oregon Country to study and collect rare and previously undiscovered plant specimens, had no stake in the future of the Willamette. His journals commented only on the primitive beauty of the valley without reference to pastoral images. For example, he wrote, "Country undulating: soil rich, light with beautiful solitary oaks and pines interspersed through it, and must have a fine effect, but being burned and not a single blade of grass except on the

margins of rivulets to be seen." Another time he remarked simply, "Country open, rich, level, and beautiful." Although economic factors motivated fur trapper Alexander Henry's sojourn in the Willamette in January of 1814, he envisioned no great transformation of the region and thus focused his attention on its primitive beauty: "The country is pleasant, thinly shaded with oak, pine, liard, alder, soft maple, ash, hazel, etc. At a short distance are ranges of grassy hills, where not a stick of wood grows; the prospect is delightful in summer, when blooming and verdant."[41]

Both Henry's and Douglas's journals reveal neither grandiose political nor economic plans for the Willamette Valley's future. These motivations, however, tempered the writings of others, such as Wilkes, Matthieu, and Palmer, and the future of the valley's environment would largely be left to people of their tradition. An interesting point is that, although these other observers noted the existing and potential pastoral nature of the Willamette, they also could not help but be drawn to its primitive beauty. Warre and Vavasour commented, "To the eye the country, particularly the left bank of the river, is very beautiful. Wide extended, undulating prairies, scattered over with magnificent oak trees, and watered by numerous tributary streams." Wilkes noted of the prairie scenery that captivated him in June 1841, "We passed in going thither, several fine prairies, both high and low. . . . The prairies are at least one-third greater in extent than the forest: they were again seen carpeted with the most luxuriant growth of flowers, of the richest tints of red, yellow and blue, extending in places a distance of fifteen to twenty miles." That same summer he remarked how the prairies, "covered with variegated flowers . . . added to the beauty as well as the novelty of the scenery." Seven years later, American settler and immigrant promoter George Atkinson prefaced his observations of the valley's pastoral image ("The oak groves on the slopes of the hills appear like orchards of the finest park scenery") with the remark, "broad prairies, forests, bands of woodland surrounding beautiful meadows . . . a vast region of prairies surrounded by hills." William A. Slacum, whom President Andrew Jackson commissioned to examine and report on Pacific coast settlements, surveyed the Willamette in 1837, showing a particular sensitivity to color:

In ascending this beautiful river, even in midwinter, you find both sides clothed in evergreen, presenting a more beautiful prospect than the Ohio in June. For 10 to 12 miles, on the left bank, the river is low and occasionally

overflows. On the right the land rises gradually from the water's edge, covered with firs, cedar, laurel, and pine. The oak and ash is at this season covered with long moss, of a pale sage green, contrasting finely with the deeper tints of the evergreens.[42]

Some early observers of the Willamette Valley waxed more poetic in their descriptions of its primitive scenery. For instance, Gustavus Hines, who came with the Jason Lee Mission in the 1830s, noted, "Throughout these valleys [Umpqua, Klamath, and Willamette] are scattered numberless hillocks and rising grounds, from the top of some of which, scenery, as enchanting as was ever presented to the eye, delights and charms the lover of nature, who takes time to visit their conical summits."[43] Hines's description of the valley's foothills also pointed to an important aspect of the valley's landscape that could not be valued in economic terms or be captured in the pastoral image.

Writers' differing political and economic conceptions of the valley's future did temper their interpretation of the landscape's utilitarian potential, but this underlying theme of agreement about the valley's primitive or wilderness beauty gives continuity to the early exploration literature that came out of the Willamette. Overwhelmingly, however, pastoral and utilitarian conceptions seem to provide the constant counterpoint to the magnificence attributed to the primitive, natural beauty of the Willamette landscape in early writings. As a single feature of the valley's landscape, the awe-inspiring falls on the Willamette River perhaps best show this tension between the valley's undeveloped "wilderness" beauty and the economic utility it could provide as a pastoral landscape. When Alexander Henry came to the falls on 23 January 1814, he expressed his attraction to the view by simply stating that the falls had a "wild, romantic appearance." Thirty-two years later, Lieutenant Neil M. Howison, while examining affairs for the United States in the Pacific Northwest, wrote at length about the scene he witnessed at the falls on a summer day: "the sun's rays reflected from these cliffs make the temperature high, and create an unpleasant sensation of confinement, which would be insupportable but for the refreshing influence of the waterfall: this, divided by rocky islets, breaks into flash and foam, imparting a delicious brightness to this otherwise somber scenery." Hines also commented on the "beautiful cataract" but immediately brought in his ideas on development when he proclaimed, "The hydraulic privileges which it affords, and which are beginning to be extremely used, are almost boundless." And in 1841,

Charles Wilkes mentioned only utilitarian potential of the falls, which "offer the best mill-site of any place in the neighboring country. Being at the head of the navigation for sea-vessels, and near the wheat growing valley of the Willamette, it must be a place of great resort."[44]

The falls on the Willamette played an instrumental role in the environmental prehistory of the valley of the long grasses. The Kalapuya had even assigned them mythical significance. The falls also found their way into early European and Euro-American travel, exploration, and settlement literature about the Oregon Country. Europeans and Euro-Americans interpreted the falls' physical composition with relevance to their own culture. On the one hand, they remarked on the falls' primitive, natural, or wild beauty and effect on the senses. On the other hand, they easily cast the falls as an essential element of a future Euro-American pastoral landscape.

Primitivism and pastoralism in exploration literature concerning the valley of the long grasses can be refined into competing conceptions of natural beauty and industrial and agricultural utility. Those who settled in the tributary valley of the Calapooia would use these two concepts, as well as the concept of progress, as they viewed the land through the nineteenth century. These attitudes challenged the views that the Kalapuya had held. In the process of realizing these conceptions—thus replacing the Kalapuya and acting on a whole different set of cultural values—Euro-American settlers brought incredible changes to the environment of the Willamette within only a few years of settlement.

But in addition to harboring the two conceptions of utility and natural beauty as ways of looking at the landscape, settlers realized a third component in their relationship to the land that transient observers never did. As settlers and therefore insiders, they intimately interacted with it, partly changed it and partly molded their ways to it, and, most significantly, grew attached to it.