Chapter III

The Organization of Japanese Business Networks

A vast range of business activities in Japan have been "externalized"-moved outside the firm-while being reorganized at the interfirm level. Supply, distribution, and capital allocation functions that are performed internally by vertically integrated firms in the United States are all carried out as intercorporate transactions to a far greater extent in Japan. Consider the following:

1. Supply Relationships. Patterns of external sourcing are common in many industries, including automobiles, consumer electronics, and precision machinery. In automobile production, for example, about 80 percent of the costs of a Japanese automobile come from outside suppliers, in contrast to only 50-60 percent in the United States, West Germany, and France (Odaka, Oho, and Adachi, 1988).

2. Distribution. The Japanese distribution system works largely through external networks. Within domestic markets, wholesalers (ton'ya ) are organized into elaborate networks in which products may pass through three or four middle stages before reaching final users.[1] In international markets, over half of all trade in primary materials and overseas goods takes place through only a handful of firms-Japan's nine general trading companies (Sogo shosha nenkan, 1985).

3. Capital Funding. In making capital investments, large Japanese firms have relied considerably more than their U.S. counterparts on funding from external sources rather than from internal cash flows.

During much of the postwar period, this was through heavy borrowing from financial institutions.[2] In recent years, it has come increasingly from bond and equity issues financed through these same financial institutions. In addition, trading companies have long served as an important source of capital for smaller businesses through the extension of trade credit.

While moved outside the firm, these external relationships have themselves been organized at the intercorporate level through complex overlapping webs of business affiliations. Japanese industrial organization contains enterprise groups of varying degrees of coherence and intensity, several basic forms of which are introduced in this chapter.

I begin by outlining general patterns of relationships common to business networks in market economies and looking at how these are reflected in specific alliance patterns in Japan. I then consider some fundamental characteristics of Japanese industrial organization that distinguish it from its American counterpart and demonstrate these empirically through comparative analyses of the basic features of corporate ownership networks in the two countries. These analyses show that ownership structures of Japanese corporations are far more likely than in the United States to be organized as stable relationships that endure over decades, to be reciprocated among mutually positioned companies, and to be embedded in other ongoing business relationships among the firms. This sets the framework for a more detailed study of the organization of relationships among Japan's largest corporations, as seen in the intermarket keiretsu. This alliance form is described briefly in this chapter and studied in more detail in following chapters.

THE WEB OF BUSINESS AFFILIATIONS

The term "network" has taken on dual meaning in the area of organizational theory. On the one hand, it refers to a rigorous, formalized methodology, as reflected in journals like Social Networks and sophisticated techniques of structural analysis (e.g., White et al., 1976; Burt, 1983). On the other hand, it has been used to refer to informal social systems which are not easily captured by formal theories of bureaucracy or markets (e.g., Eccles and Crane, 1988; Lincoln, 1989; Powell, 1990). Both the more formal and the metaphorical usages of the network perspective have received increasing attention in the analysis of the industrial organization of East Asian economies. Comparative approaches

have looked at how network structures differ across countries and have combined elements of rigorous network data collection with informal theories of "network organization" (Hamilton and Biggart, 1988). Normative approaches (Imai, forthcoming) have provided economic rationales for particular arrangements and have relied primarily on an informal approach to network analysis. The approach taken here combines elements of both the formal and the informal meaning of network.

In the network approach, emphasis is placed on the direct study of how economic and other transactions allocate resources in a social system (Wellman and Berkowitz, 1987). The particular composition of ties among financial, commercial, and industrial firms is seen as determining significant features of an economy's overall organization and its resulting performance. Institutions such as markets, industries, and business groups become defined as characteristic patterns of concrete exchanges among diverse actors within a broader matrix of intercorporate relationships in which they are embedded. Among various archetypal patterns, we consider the following three: industry, the business community, and the intercorporate alliance. Each represents a distinctive social focus (Feld, 1981), with industry set in the context of relationships based in competition within similar market niches, the business community in the loosely coupled structure of interpersonal networks; and alliances in historical ties of obligation among companies.

The importance of industry has been a primary focus of economists and is of increasing interest to sociologists and organizational theorists as well. In network theory terms, industry represents a nexus of critical resource dependencies among an identifiable set of "structurally equivalent" firms-companies that share common patterns of exchange in economic markets (Burt and Carlson, 1989). Pursuit of competitive advantage is an important driving rationale. Corporate ownership, for example, becomes a means of gaining control over critical uncertainties in organizational environments-a tool by which organizations seek to "restructure their environmental interdependence in order to stabilize critical exchanges" (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978, p. 115). Similarly, mergers and joint ventures arise in order to manage concrete but problematic relationships with other firms (Williamson, 1985). Empirically, the structure of industries has been correlated with various features of firm conduct and performance in the industrial organization literature, including advertising and R & D expenditures, and profits, growth, and diversification rates (e.g., Scherer, 1980).

The business community as an organizing framework can be viewed

in several ways. In a social-hierarchy formulation, economies are seen to stratify around firms' statuses. Averitt (1968) argues that this results in a "dual economy" made up of large, technologically sophisticated, multimarket, elite firms at the center and small, less-developed firms at the periphery-a formulation that has long been popular for explaining Japanese industrial organization. Whether developed economies, including that of Japan, can in fact be divided this neatly has been increasingly questioned.[3] Nevertheless, it is clear that the markets for capital and labor, at the least, are affected by a firm's position in a larger social structure. The work on diffuse networks of intercorporate relationships suggests ways in which relationships among firms may be organized to serve interests at the level of a broader business class (Palmer, 1983; Ornstein, 1984). Useem (1984), for example, argues that directorships shared across firms serve not so much the immediate interests of each organization-to monitor and mobilize bilateral pairs of firms-as a resource dependency position would indicate, but rather the interests of an inner circle of business elites.[4]

These archetypes suggest two different, though not incompatible, sets of business relationships. The industry framework focuses primarily on firms' immediate task environments and the ways in which critical resource- and technology-driven dependencies have led to adaptations at the interfirm level to manage them. The business community framework, in contrast, is concerned with the position of corporations in an extended social structure, its stratification, and the ways in which this affects interfirm activity.

A third organizing framework is what I have termed the "intercorporate alliance": relationships based on localized networks of long-term, mutual obligation.[5] In contrast to the broader class-wide interests of an extended business community, alliances are defined by interests among specific subsets of closely connected firms. The most powerful "inner circle" for each firm is made up of the other group companies with which it is affiliated. At the same time, alliances differ from organization by industry in that historical association is as important as immediate task requirements in determining the particular patterns they take. Firms in Japan are linked together over time in relationships that, as we see in the following chapter, involve strong patterns of preferential trading among firms in the same group. These patterns, moreover, occur even where functional transactions (e.g., bank loans or steel trade) could easily take place across groupings.

Industries, Status Hierarchies, and Alliances: Cross-Cutting Spheres of Japanese Business

The names of Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo are well known as the remnants of the prewar zaibatsu groupings operating under family-controlled holding companies. But these represent only a fraction of the vast complex of elaborate alliances that make up the Japanese economy and bring firms into complex and often overlapping networks of vertical, horizontal, and diversified relationships. There exists in Japan no single, universally accepted system for classifying these relationships. Nevertheless, we can differentiate four broad categories of alliance that are typical in Japan, which are referred to here as (1) the intermarket keiretsu, (2) the vertical keiretsu, (3) small-business groups, and (4) strategic alliances, including joint ventures and project consortia.

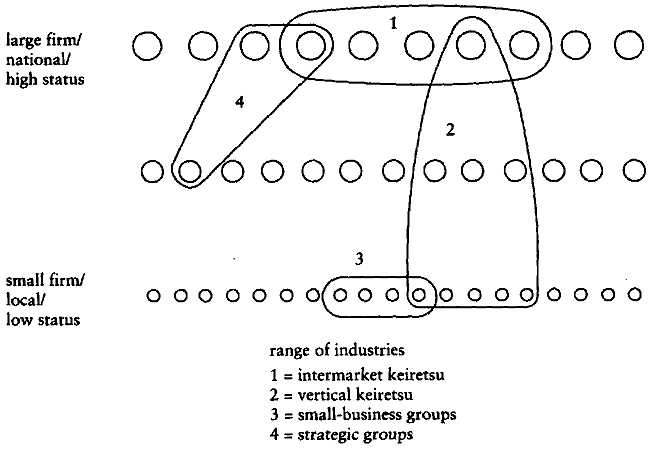

Figure 3.1 depicts these relationships schematically, showing their representation in different market sectors and their location in the business community. The horizontal axis reflects the diversity of market sectors in which the group is involved, with a wide span indicating broad industrial representation. The vertical axis indicates firms' positions within the structure of firm stratification. The "traditional" sector at the bottom reflects the central role of local social networks of family, friendship, and community ties, while the "modern" sector at the top reflects embeddedness in a national network of business elites (the zaikai )-the Japanese social economy is acutely sensitive to company size, and security, status, wealth, and power accrue to the largest.

The Intermarket Keiretsu Groupings of large firms based around a major commercial ("city") bank are referred to variously as keiretsu, kigyo shudan or kigyo gurupu (enterprise group). As noted earlier, I have adopted the keiretsu terminology and have added the qualifiers "intermarket" and "vertical" to characterize two quite different forms of group structure. This form of alliance, discussed in considerably greater detail below, represents loosely structured associations of large relatively equally sized firms in diverse industries, including banking, commerce, and manufacturing. The social communities of business that they represent are the elite in Japan-economically, politically, and socially.

Fig. 3.1. Cross-Cutting Social Spheres: Industrial Diversity, Status Position, and Alliance Form.

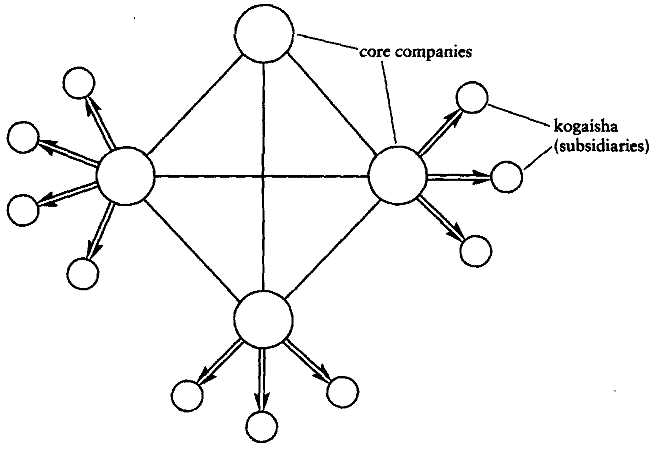

The Vertical Keiretsu In contrast to the highly diversified character of the intermarket keiretsu, the vertical keiretsu are tight, hierarchical associations centered on a single, large parent firm and containing multiple smaller satellite companies within related industries. While focused in their business activities, they span the status breadth of the business community, with the parent firm part of Japan's large-firm economic core and its satellites, particularly at lower levels, small operations that are often family-run. Most firms in intermarket keiretsu maintain their own vertical keiretsu, leading to an intersection of these two forms, as seen here.

The vertical keiretsu can be divided into three main categories. The first are the sangyo keiretsu, or production keiretsu, which are elaborate hierarchies of primary, secondary, and tertiary-level subcontractors that supply, through a series of stages, parent firms. The second are the ryutsu keiretsu, or distribution keiretsu. These are linear systems of distributors that operate under the name of a large-scale manufacturer, or sometimes a wholesaler. They have much in common with the vertical marketing systems that some large U.S. manufacturers have introduced to orga-

nize their interfirm distribution channels (Stem and El-Ansary, 1977). A third-the shihon keiretsu, or capital keiretsu-are groupings based not on the flow of product materials and goods but on the flow of capital from a parent firm, and are sometimes referred to in Japanese academic writings by the German term Konzern. The leading contemporary examples are the railroad groups of Tokyu and Seibu, which have diversified from train lines into real estate, hotels, department stores and distribution, and travel and recreation businesses.

Small-Business Groups Firms of fewer than a thousand employees account for over half of all sales and assets in the Japanese economy but are often overlooked in favor of the more conspicuous large firms. One of the ways that small firms have tried competing with the more efficient large-firm sector is through collaboration. The result is a rich panoply of producers and purchaser cooperatives, traditional and high-technology industrial estates (the last are sometimes known as "technopolises"), and neighborhood associations. I have labeled these collectively as "small-business groups."

Small-business groups involve a considerably greater diversity in 'the type of interfirm organization represented than do the intermarket or vertical keiretsu. They are sometimes focused on a single industry but also frequently bring together firms across multiple industries, positioned horizontally and organized within a common geographical nexus. Small-business groups trade largely in social currency and are closely tied to the local communities of which they are a part.

Strategic Alliances Strategic alliances include a wide range of inter-firm organizations based on relatively focused instrumental needs. They are sometimes called "functional" groups (kino-teki shudan ) though "ad hoc" is probably closer; they include joint ventures, project consortia, and various other forms of cooperation (in Japanese, the popular word teikei ) that move firms outside their traditional keiretsu groupings into new alliances that bridge industries and utilize new technologies. Strategic groupings cut across all sectors of industry and society, often in diagonal relationships that span diverse market sectors and social positions. Strategic alliances have increased dramatically in frequency in Japan in the 1980s, as they have in the United States. Large firms in Japan, for example, are now establishing relationships with small, high technology firms in an attempt to expand beyond their traditional industries (see, for example, Imai, 1984).

Alliances and the Firm's Institutional Environment

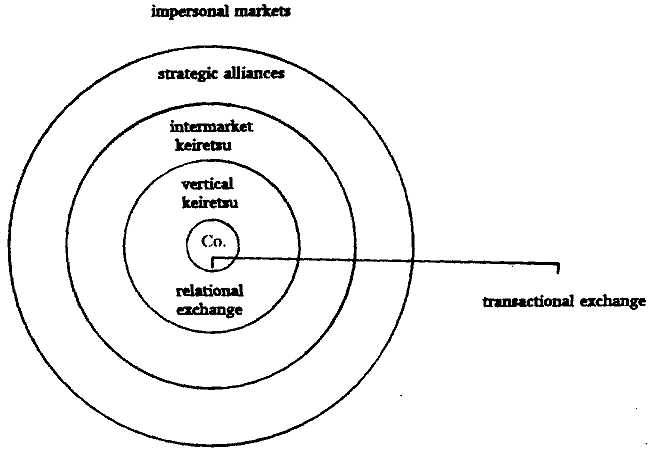

From the Japanese firm's point of view, trade takes place within a set of ordered environments that can be dimensionalized along a continuum from "relational" to "transactional" exchange, as seen in Figure 3.2. Legal theorist Ian Macneil (1978) has characterized transactional exchange as the sine qua non of impersonal market exchange: "A transaction is an event sensibly viewable separately from events preceding and following it, indeed from other events accompanying it temporally- one engaging only small segments of the total personal beings of the participants " (p. 893). It is a one-time, arm's-length exchange among anonymous or otherwise unrelated traders, requiring neither structural nor symbolic connection between the parties. In relational exchange, in contrast, actors rely on various forms of implicit assumptions and agreements to organize their relationships: "The fiction of discreteness is fully displaced as the relation takes on the properties of 'a minisociety' with a vast array of norms beyond those centered on the exchange and its immediate processes" (p. 901).

Trade within the firm, at the center of Figure 3.2, is marked by a high degree of relational exchange: actors are embedded in a common arena governed by structurally interlinked resource flows and by a common set of rules and rituals that constitute the firm as a social system. The relationship among organizational members as a whole takes precedence over that of any single transaction. The first ring demarcates the firm's boundaries, and immediately outside of it lies the firm's first-order environment. At the interfirm level, probably the most critical relationship is that between the company and its suppliers. The dose ties that exist among Japanese firms and the subcontractors in their vertical keiretsu are an often-noted feature of the organization of industry in Japan (e.g., Clark, 1979). As suggested earlier, these subcontractors perform many of the functions typically carried out in-house by U.S. firms through their own divisions. Within the vertical keiretsu, exchange between the parent and satellite firms is embedded in a dense network of ongoing relationships, as various forms of information, technical and financial assistance, and managerial expertise are provided on a reciprocity basis.

The parent firm, and by extension its satellites, are in turn embedded in a broader set of relationships defined by the intermarket keiretsu. This second-order environment comprises more loosely coupled relationships among dozens of firms in diverse industries. Internal exchange is gener-

Fig. 3.2. Alliance Form and the Japanese Firm's Institutional Environment.

ally less pervasive than at the firm or vertical keiretsu level, but the identity of the group nevertheless imparts structural and symbolic significance to these exchanges. Strategic groupings represent a third-order environment. These involve exchanges more intimate and durable than those in impersonal markets, but generally without the history, symbolic coherence, or density of exchange networks found in the vertical or intermarket keiretsu. Finally, at the outer level one finds impersonal exchanges among actors that are relatively unconnected structurally or symbolically-for example, a firm's occasional purchases of office supplies from a large number of different retailers. These are "true" market transactions, without intensive ties or enduring obligations.

OVERALL PATTERNS IN JAPANESE AND U.S. OWNERSHIP NETWORKS

The importance of Japan's overlapping structure of intercorporate relationships is nowhere more evident than in the case of intercorporate ownership networks. As noted in the previous chapter, corporate ownership and the market for corporate control represent fundamental relationships in capitalist systems that define the underlying structure of influence over the basic derision-making units, that is, its corporations.

Herman (1981, p. 101) points out that corporate ownership "has what might be termed an 'omnipresence effect' on managerial purpose and behavior, affecting them at many levels and through a variety of channels."

Corporate shareholding in the United States generally takes the form of a capital market transaction, the primary purpose of which is direct returns on investment. For this reason, financial theories focus on the daily, ongoing patterns of trading that define a circular flow of capital among investors. The buying of corporate shares by investors is seen as based on a profit-maximizing calculus, sensitive to price signals reflected in changing share prices among anonymous traders. To the extent that investors have generally similar access to information and this information gets quickly transmitted in share prices, the market is informationally efficient. At this level, the stock market most closely conforms to its original purpose of raising and allocating capital by corporate stock issuers.

This is not the only significance of the stock market's operation, however. Where investors are other corporations, as is the predominant pattern in Japan, ownership becomes a means for structuring relationships among those corporations in ways that set markets for capital and control in the context of other business interests. This does not imply that the stock market no longer allocates capital or responds to conditions of supply and demand in Japan. Rather, corporate ownership takes on the added feature of being one of the main arenas in which corporations' strategic interests are protected and promoted. This difference is reflected in the concrete pattern of relationships among shareholders, of which we consider the following four: the extent of concentration; stability; reciprocity; and multiplexity, or the overlap with other business relationships.

Concentration of Shareholding

Among the measures of corporate ownership that have received attention, probably none has been more widely discussed than shareholding dispersal. This is in large part due to its prominence in Berle and Means's original argument, which premised a belief in the rise of managerial control on the observation that individual owners in most major corporations no longer hold dominant blocks of stock. Berle and Means reasoned that investors holding only a small fraction of a company's shares would be reluctant to spend the time and energy necessary to

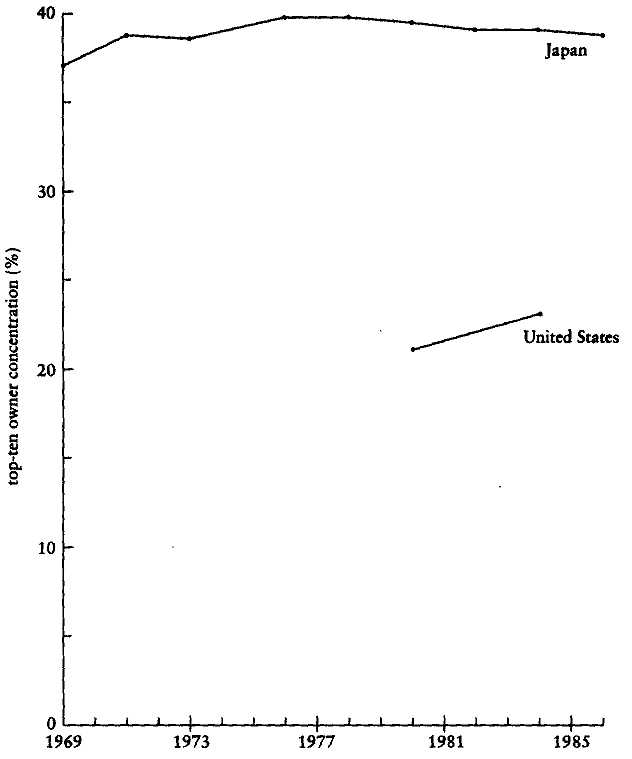

Fig. 3.3. Proportion of Total Equity Held by Top-Ten Shareholders. Source: See Appendix A.

ensure that the company's managers were looking out for shareholder interests.[6]

Since Japanese intercorporate shareholding primarily reflects concrete strategic interests rather than those of portfolio diversification, major shareholders should take more substantial positions in other firms. This is apparent in Figure 3.3, based on data described in Appendix A. Between 1969 and 1986, the top-ten shareholders in Japanese companies held from 37.1 percent to 39.8 percent of total issued equity.

In the United States for the two years of available data, these figures were 21.1 percent and 23.1 percent. Among the leading five shareholders in each country (not reported here), the figures were 27.8 percent and 29.4 percent for Japan and 15.2 percent and 16.6 percent for the United States. Thus, corporate ownership is far more concentrated in Japan than in the United States (although note that the U.S. sample showed a nearly 10 percent increase during the four-year interval covered by the data).

Presented as an overall total, as above, these figures maintain the company-centered focus of managerial theory and provide an overall index of the relative role played by leading shareholders in the capital structure of corporations. Another way of interpreting these figures is as a measure of the "strength" of dyadic relationships between investors and companies. Interpreted in this way, we find that Japanese top-ten equity investors hold an average of between 3.7 percent and 4.0 percent of total issued equity and the top-five alone hold between 5.6 percent and 5.9 percent. In the United States the respective figures are 2.1 percent and 3.0 percent for 1980 and 2.3 percent and 3.3 percent for 1984. Major intercorporate ownership dyads, therefore, are not only more prevalent in Japan, they represent stronger relationships than in the United States.

Stability of Interlocks

There is good reason to believe that the relationship between equity shareholder and firm in Japan will be a highly durable one where shareholders take on the role of a reliable constituency of well-known trading partners. As an executive in Sumitomo Life Insurance, the largest holder of shares in the Sumitomo group, put it: "If group shares go up, we don't sell them off quickly, though naturally we're happy. If the value of a company's shares goes up, that improves the financial condition of all group companies." A survey in the Nihon keizai shinbun found that more than 60 percent of publicly traded Japanese companies think it is desirable to have 60-70 percent of outstanding shares held by stable shareholders. The main reason given was that it freed executives from plotting takeover strategies to concentrate on business goals (cited in the Wall Street Journal, November 17, 1989). In another survey, fully 660 out of 661 Japanese firms expressed a belief in the importance of the stable shareholder system (Heftel, 1983, n. 46).

Independent estimates of holdings by stable shareholders (antei kabunushi) typically fall somewhere around 70 percent of total shares

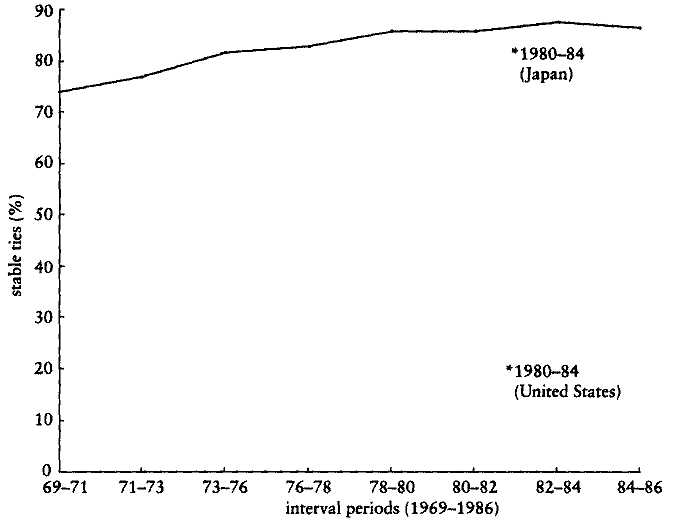

Fig. 3.4. Proportion of Stable Top-Ten Equity Ties. Source: See Appendix A.

held on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Indeed, the Ministry of Finance has at various times sought to regulate the extent of stable shareholding by mandating a minimum level of "floating" shares. Since such a proportionately small ratio of firms' shares is actually traded, the belief is that stock prices often do not accurately reflect the market value of the firm.[7] In comparison, U.S. institutional shareholders are seen as extremely active traders in corporate securities-and, by implication, unstable shareholders. It is this ability to exit the relationship, often in mass, that gives institutional investors in the United States their power over corporations. As one business writer states: "In Wall Street, people argue that that is the best way for institutions to influence management. Selling the stock in large blocks pushes the price of the stock down, increasing the company's costs of raising capital, and punishes the management for poor performance" (quoted in Mintz and Schwartz, 1985, p. 99).

These differences should be reflected in overall greater stability of equity interlocks in Japan than in the United States, a prediction explored empirically in Figure 3.4. "Stable" equity relationships are defined in this analysis as top-ten shareholders in one measurement period that remain in the top ten in the subsequent measurement period. Among

the American firms in the database, less than one-quarter (23 percent) of the top-ten shareholders in 1980 remained in the top ten in 1984. In contrast, over four-fifths (82 percent) of the top-ten shareholders remained in the top ten for the Japanese sample. It is evident from this that there are dramatic differences in ownership stability in the two countries.

The biannual data available for Japanese firms also shows the trend in stable shareholding during the 1969-1986 period. These results reveal a gradual but detectable increase in stable shareholdings throughout this period, from 74 percent in the first interval to 87 percent in the last interval. There is no evidence, therefore, that stable shareholdings represent a declining proportion of total shareholding in Japan or that equity relationships among corporations are becoming more transitory. The corporate capital structure of the Japanese firm has been and continues to be dominated by investors that maintain a long-term stake in the company.

Extent of Reciprocity

Intercorporate shareholding in Japan is also more likely to be reciprocated than in the United States as a result of the system of kabushiki mochi-ai, or stock crossholdings. The term mochi-ai, construed narrowly, means "to hold mutually." But it also carries an additional connotation from its other uses of helping one another, of shared interdependence, and of stability. Crossholdings, as Japanese businessmen point out, "keep each other warm"- hada o atatame-au.

In the process of holding each other's shares, mochi-ai becomes self-canceling-a kami no yaritori, or a paper exchange-thereby removing shares from open public trading. The issue of explaining a self-canceling shareholding system was raised by an executive in the Mitsui group more than twenty years ago: "What's the use of owning two or three hundred shares in related companies? If we had the money, we would put it to better use in equipment or something else" (quoted in Oriental Economist, March 1961). No answer was provided by this executive but the question is a good one. Borrowing heavily from financial institutions in order to make equity investments in other firms will rarely make sense from the point of view of narrow economic rationality, for companies are paying interest on that borrowed capital. The reasons for share cross-holdings seem to lie instead in their importance in shaping the qualitative relationships between firms. Share crossholdings among group com-

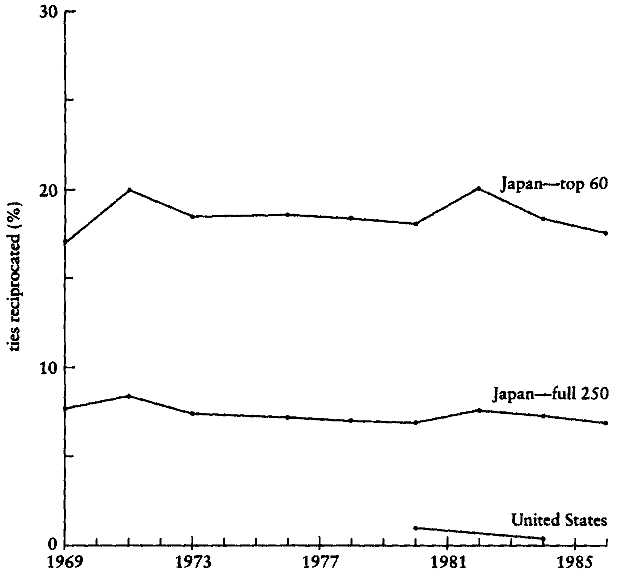

Fig. 3.5. Proportion of Reciprocated Top-Ten Equity Ties. Source: See Appendix A.

panies create a structure of mutually signified relationships, as well as serve as a means of protecting managers from hostile outsiders (Okumura, 1983; Nakatani, 1984).

Reciprocal shareholdings are likely to be far less common in the United States because of the absence of coherent alliances around which to organize and the uncertain legality under antitrust laws of reciprocity where partners also do business together. These predictions are tested in Figure 3.5, where we find some support. Among the intercorporate equity interlocks in Japan, 7 percent are reciprocated in 1980, while this figure is only 1 percent in the United States in 1980 and declines to less than half a percent by 1984.

Although higher than in the United States, these reciprocity figures are lower than were expected for Japan. One possibility is that it is primarily very large companies in Japan that reciprocate ties. Nearly one-third of the sample of two hundred industrial firms in Japan are satellites (kogaisha or kanren gaisha ) of a major parent manufacturer. These firms are unlikely to reciprocate ties since theirs are primarily subordinate relationships. To test this prediction, reciprocated ties solely among the forty largest industrials and twenty largest financial institutions were analyzed. When we limit intercorporate interlocks to these sixty companies, reciprocity rates for 1980 more than double, increasing from 7 percent to 18 percent.[8] Company size, therefore, appears to be a fundamental determinant of the precise character of companies' intercorporate equity linkages.

Multiplexity of Ties

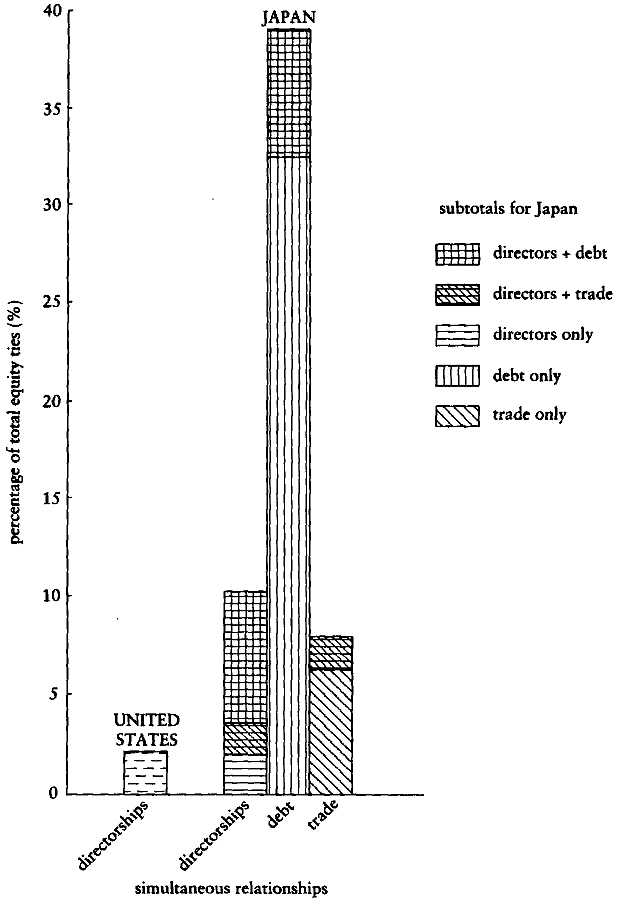

One of the most important measures of the significance of strategic interests in ownership patterns is the extent to which ties in equity networks are "multiplex," or overlap with ties in other networks. Both transactions costs and resource dependence theories view the taking of equity or board positions in other companies as means of managing dependency and gaining control over critical banking and trading relationships (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Williamson, 1985). The Japanese data permit a strong test of the multiplexity hypothesis, since equity crossholdings and board interlock patterns can be compared with the networks mapped by banking and trade. The U.S. data permit a weaker test of the multiplexity hypothesis, comparing information on ties they contain pertaining to equity ownership and directorship interlocks.

The prediction tested here is that shareholding positions in Japan are more likely to become embedded in other ongoing relationships between the firms, as the role of shareholder becomes merged with that of business partner. In the words of one Japanese executive, "there is no sense in holding shares in a company with which business ties are slim." This relationship is especially apparent in relationships among industrial firms and their client banks, where the linking of equity and loan positions indicates a transformation in the nature of each. Credit, in the form of bank loans, has come to resemble equity in allowing creditors flexibility in repayment by deferring interest and principal payments and reducing the "compensating balances" that corporate borrowers need to leave in banks during times of financial adversity. Loans are rolled over

as a matter of practice. Furthermore, banks become active participants in the management of their client firms, particularly when the company is in trouble (Pascale and Rohlen, 1983). Common stock, in contrast, seems to take on many of the characteristics Westerners associate with debt. Shareholders demand relatively fixed returns on their investment, in the form of stable dividend payments, but do not ask for active influence over management.

Relatively strong securities regulations in the United States limit the methods by which shareholders can control firms. These legal differences are reflected in the extent of overlap found between the two network variables coded for both countries, equity and directorships. Japanese firms with a top-ten equity position in another firm were about five times more likely to dispatch a director to the same company as were American firms. In total, 10.1 percent of the leading shareholders in the Japanese sample held a simultaneous board position on the same firm, in comparison with 2.1 percent of the leading shareholders in the U.S. sample.

For the Japanese data, we are also able to discern other forms of multiplexity, including debt-equity and trade-equity linkages. Figure 3.6 shows the extent to which equity shareholdings are associated with directorship, debt, and trade ties. In addition to the multiplex directorship relationships just noted, in 7.9 percent of the cases where an equity tie was sent, a trade tie in the same direction was also sent, while in fully 39.0 percent of the cases a debt tie was sent. In total, when we exclude double counting of relationships, we find that in 48.9 percent of all cases where a company is a leading shareholder, we can detect other simultaneous relationships as a top-ten lender, a leading trading partner, and/or a dispatcher of one or more directors.[9]

THE SIX MAIN INTERMARKET KEIRETSU: AN OVERVIEW

The features of the Japanese business network structure outlined above-dense connections of substantive, enduring intercorporate relationships-are pervasive in Japanese industrial organization. Where these take the form of alliances among major financial, industrial, and commercial companies, they often add another feature: organization into identifiable keiretsu.

Among the firms that constitute the intermarket groups are those companies and industries that have historically been most central in the

Fig. 3.6. Proportion of Equity Interlocks with Other Simultaneous Relationships (Multiplexity). Source: See Appendix A.

Japanese economy. Within the six main groups, three have clear and direct connections to zaibatsu that dominated the Japanese economy during the prewar and wartime periods: the Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo groups all have at their center most of the companies that were first-line subsidiaries of the zaibatsu holding company, the honsha. In addition, the Fuji (or Fuyo) group and the newly emergent Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank group bring together subgroups of firms that had been associated with other prewar zaibatsu. Fuji takes as its financial core firms in the old Yasuda zaibatsu-including Fuji Bank, Yasuda Trust and Banking, and Yasuda Mutual Life Insurance-while Dai-Ichi Kangyo brings two smaller prewar zaibatsu-Furukawa and Kawasaki-together with a large number of other firms to form a newer grouping still in the process of consolidating. Because of the comparatively weak ties that the Fuji and Dai-Ichi Kangyo groups maintain with these old zaibatsu and because of the centrality of their banks, these two groups are usually classified together with a third group, based on the Sanwa Bank, as "bank groups." The Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo groups are classified as "former zaibatsu groups."

The Characteristics of Keiretsu Membership

Earlier we noted the problem of defining membership in alliance forms, where boundaries are often unclear. This methodological problem can be partially resolved in the intermarket keiretsu by utilizing group presidents' councils in order to identify membership. These councils, which are discussed in detail in the following chapter, have become an institutionalized forum for communication among group firms' chief executives and now publish lists of their participants. This measure of group membership is both unambiguous and empirically correlated with all major features of the keiretsu. Since participation in the council is restricted to those firms most central to the group, what we might call the "core" members, it avoids the problem of including peripheral members or those whose membership might be questioned in the analysis.

The membership lists for the six groups are presented in Table 3.1, which includes all firms that were in one of the councils as of 1989. In overview, we find that the firms affiliated with the intermarket keiretsu are among the largest, oldest, and most prestigious in Japan. The 188 companies listed here (193 formal affiliates less five duplicate entries) represent only slightly over.01 percent of the estimated 1.7 million firms

TABLE 3.1. MEMBERSHIP IN THE SIX MAIN INTERMARKET KEIRETSU | ||||||

Mitsui | Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Fuyo | Sanwa | Dai-Ichi Kangyo | |

Industry | (24 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (20 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (44 cos.) | (47 cos.) |

City bank (40.5) | Mitsui Bank | Mitsubishi Bank | Sumitomo Bank | Fuji Bank | Sanwa Bank | Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank |

Trust bank | Mitsui Trust | Mitsubishi Trust | Sumitomo Trust | Yasuda Trust | Toyo Trust | |

Life insurance | Mitsui Life | Meiji Life | Sumitomo Life | Yasuda Life | Nippon Life | Asahi Life |

Casualty insurance (52.8) | Taisho F&M | Tokio F&M | Sumitomo F&M | Yasuda F&M | Taisei F&M | |

Trade & commerce (66.7) | Mitsui | Mitsubishi Corp. | Sumitomo Corp. | Marubeni | * Nissho Iwai | C. Itoh |

Construction (66.7) | Mitsui Constr. | Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Taisei | Ohbayashi | Shimizu Constr. |

Real estate (55.1) | Mitsui Real Est. | Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Tokyo Tatemono | ||

Fibers & textiles | Toray | Mitsubishi | Toho Rayon | Unitica | Asahi Chemical | |

Continues on next page

Continued from previous page

Mitsui | Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Fuyo | Sanwa | Dai-Ichi Kangyo | |

Industry | (24 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (20 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (44 cos.) | (47 cos.) |

Chemicals (43.3) | Mitsui Toatsu Mitsui Petro- | Mitsubishi Kasei Mitsubishi Mitsubishi Gas Mitsubishi | Sumitomo Sumitomo | Showa Denko | Sekisui Chemical Hitachi Fujisawa Kansai Paint Tokuyama Soda Tanabe Seiyaku | Denki Kagaku |

Oil & coal (45.0) | Mitsui Mining | Mitsubishi Oil | Sumitomo Coal | Tonen | Cosmo Oil | Showa Shell |

Glass & cement (48.8) | Onoda Cement | Asahi Glass M. Mining & | Nippon Sheet Sumitomo | Nihon Cement | Osaka Cement | Chichibu |

Paper (37.7) | Oji Paper | Mitsubishi Paper | Sanyo-Kokusaku | Honshu Paper | ||

Steel (52.7) | Japan Steel | Mitsubishi Steel | Sumitomo Metal | NKK | * Kobe Steel | Kawasaki Steel |

Nonferrous metals (56.0) | Mitsui M&S | Mitsubishi Mitsubishi Mitsubishi Cable | Sumitomo Sumitomo Sumitomo Light | Hitachi Cable | Nippon Light Furukawa Co. Furukawa | |

General & transportation machinery (45.5) | Toyota Motors Mitsui Eng. & | Mitsubishi Mitsubishi Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Kubota | NTN Toyo B. | Niigata Engnr. Kawasaki Heavy IHI Heavy Ind. Isuzu Motors Iseki & Co. Ebara Corp. |

Continues on next page

TABLE 3.1. (Continued from previous page ) | ||||||

Mitsui | Mitsubishi | Sumitomo | Fuyo | Sanwa | Dai-Ichi Kangyo | |

Industry | (24 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (20 cos.) | (29 cos.) | (44 cos.) | (47 cos.) |

Electrical & precision machinery (39.3) | Toshiba | Mitsubishi Nikon | NEC | * Hitachi Co. | * Hitachi Co. | * Hitachi Co. Nippon Asahi Optical |

Shipping (58.7) | Mitsui-OSK | Nippon Yusen | Showa Denko | Yamashita-SII | Kawasaki Kisen | |

Warehousing (33.9) | Mitsui W. | Mitsubishi W. | Sumitomo W. | Shibusawa W. | ||

Other industries | Nippon Flour | Kirin Brewery | Sumitomo | Nisshin Flour Sapporo Nichirei Tobu Railway Keihin Railway | Ito Ham | Yokohama Korakuan * Nippon Express Nippon K.K. Orient |

SOURCES : Membership lists are translated and reformatted from tables provided in Kosei Torihiki Iinkai (1983b, pp. 3-4) and Kigyo keiretsu soran (1990, p. 58). The collective share (%) of industry sales is shown in parentheses in the first column. These figures come from Nihon kigyo shudan bunsekl, vol. 2 (1980, p. 11). They are calculated as the total sales accounted for by shacho-kai members in the six groups as a percentage of total sales by all companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. * Asterisk indicates membership in more than one presidents' council. | ||||||

in Japan and just over 10 percent of the 1,700 firms listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, but their significance extends far beyond what these numbers might indicate. Among the largest 100 industrial firms in Japan, 56 are council members while 34 more are among the next 100. An additional 9 firms are not council members themselves but subsidiaries or affiliates of council member companies.

In total, therefore, among Japan's 200 largest industrial firms, about one-half (99) maintain a dear affiliation with a group, either by direct council membership or through a parent firm that is a member.[10] The importance of group companies is even more striking when considering financial institutions. All five of Japan's largest commercial banks (Dai-Ichi Kangyo, Fuji, Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, and Sanwa) are at the center of their own groups, as are the five leading trust banks, the five leading casualty insurance companies, and four of the five leading life insurance companies.

The industries in which the intermarket keiretsu are strongly represented are among those most central in an industrial economy, including capital, primary products, and real estate. The percentages in the left-hand column of Table 3.1 indicate the extent of total sales in these industries that were held by core group firms in 1980. Natural resources (oil, coal, mining), primary metals (ferrous and nonferrous metals), cement, chemicals, and industrial machinery are all well represented, as keiretsu members control between 43 percent and 56 percent of total sales in these industries. Among financial institutions, group commercial and trust banks control 40 percent of total bank capital, and group insurance companies 53-57 percent of total insurance capital. In real estate, 55 percent of total business is controlled by group members, while in distribution, 67 percent of sales is accounted for by formal keiretsu member companies.

Industries that have weak or no keiretsu participation are more likely to be newer and less central to core industrial operations-what the Japanese sometimes call the "soft" industries. These include publishing, communications, and air travel, in which the keiretsu have no involvement, and the broad category of service industries, in which they constitute less than 5 percent of total sales.

A significant feature of the interaction between industrial and alliance dynamics is what has come to be called in Japanese business parlance the "one-set principle" (wan setto-shugi ). This is the tendency among the major groupings to have one, and only one, company representing each significant industry. We see in Table 3.1 a high degree of diversification in

the six groups, yet with relatively little overlap between the product lines of its member companies. The one-set pattern, described later, is adhered to most closely among the former zaibatsu groups of Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo. Mitsubishi and Mitsui are represented in each major industry listed here, while Sumitomo participates in all but shipping and textiles, both declining industries in Japan. In addition, there are few industrial overlaps among companies within each of these three groups.[11] The membership lists in the Sanwa and Dai-Ichi Kangyo bank groups do not follow the one-set pattern as clearly. While they have representation in most of these industries, there are internal duplications in several-trading and commerce, chemicals, steel, and electrical machinery.

Another important characteristic of membership is the extremely low overlap in participation across groups, as member firms are nearly all identified with just a single council. Out of 193 total memberships in 1989, there were only 5 multiple memberships, which involved four firms: one company (Hitachi) now participates in three councils, while three others (Nissho-Iwai, Nippon Express, and Kobe Steel) participate in two. These reflect historical associations each of these firms has had with multiple group banks. The remaining members are all formally affiliated with only a single group, although some maintain informal ties elsewhere.

The Position of the Groups in the Japanese Business Community

The share of the total Japanese economy held by the three leading zaibatsu of Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo fell dramatically after the war with the U.S. Occupation-enforced dissolution of the controlling holding companies in each group. Whereas these three controlled 24 percent of total paid-in capital at the end of the war (up substantially from 11 percent in 1937), this share fell to 10 percent in 1955 before increasing several percent in the following decade (Miyazaki, 1976, p. 260). The overall position of the three former zaibatsu groups and of the three postwar bank groups has remained fairly stable since the 1960s. Collectively, the 188 core members in the six groups controlled 23.5 percent, or about one-quarter, of all stocks held in the Japanese corporate sector in 1986, up slightly from 22.6 percent in 1975. This was evenly divided among the former zaibatsu groups, at 11.9 percent, and the bank groups, at 11.6 percent (Kigyo keiretsu soran, 1988, p. 20).

Part of the zaibatsu dissolution statutes called for a ban on use of the names, logos, and trademarks of the former zaibatsu firms. However, this law was rescinded by Japanese authorities in 1952, and firms that had been members in the old zaibatsu soon returned to using their old names. For example, six companies in the Sumitomo group that had historically used the Sumitomo name (including the big three firms of Sumitomo Bank, Sumitomo Chemical, and Sumitomo Metal Industries) readopted the name after the rescinding Of the Trademarks Law. Each of these groups also returned to its historical logo, which is still used both by the group as a whole and by individual companies. These are reproduced in Table 3.2 for the three former zaibatsu groups, along with their founding dates.

The group name not only identifies membership to other group companies, but to the world at large. As one Mitsubishi executive put it, "Once a firm grows to this size, it can't afford to be fettered by the group. Still, we can make good use of the internationally vaunted Mitsubishi name, as in our technical cooperation with China and our construction of a plant in Saudi Arabia." At the time, the Mitsubishi group was using as its motto the phrase, "Your Mitsubishi, the world's Mitsubishi." In some cases, the reverse happens: the group name is avoided for fear of besmirching the reputation of other companies should the company fail. This was the case in 1917, when the Mitsui zaibatsu chose to enter the casualty insurance business but to exclude the Mitsui name from the risky venture. The consequently named Taisho Marine and Fire Insurance Co. remained a member of the Mitsui group, but it was not until the spring of 1990 that the decision was finally made for the company-now the third-ranking firm in its industry-to take on the Mitsui name.[12] According to company sources, the reason for the change to Mitsui Marine and Fire was to take advantage of the better-known Mitsui image (Japan Times, May 10, 1990).

Each of these groups maintains a somewhat different reputation within the Japanese business community. The keiretsu have become reified and animated in much the same way as do other social collectives, and one may refer to the importance of Mitsui "individualism" (hito no Mitsui ) in the relatively loose organization of the group and the strength of the individual companies and personalities involved in it; Mitsubishi "organization" (soshiki no Mitsubishi ) because of its tight quasi-hierarchical structure and the large number of group projects that bring together its member firms; and Sumitomo "cohesion" (kessoku no Sumi-

TABLE 3.2. FOUNDING DATES AND LOGOS | |||

Founding | Name | Logo | Meaning |

1590 | Sumitomo |  | Well-frame |

1615 | Mitsui |  | Three wells |

1871 | Mitsubishi |  | Three diamonds |

tomo), since it has maintained only a small core set of firms and has been the group most reluctant to expand its core membership beyond the original Sumitomo zaibatsu lineage. Similarly, relationships between the groups become part of a wider social competition. The "battle" between the Sumitomo and the Mitsubishi groups, at least in the eyes of some observers (e.g., Kameoka, 1969), is really one between two different business cultures-the rationalistic and commercial orientation of Osaka, where Sumitomo developed, and the social and political orientation of Tokyo, the home of Mitsubishi.

Where detailed analyses are called for in the following chapter, I focus on one of the three former zaibatsu groups, Sumitomo, and one of the three bank groups, Dai-Ichi Kangyo. These represent two extremes in intermarket keiretsu organization. Sumitomo is the oldest of the groups, dating its origins back four hundred years to the start of a copper crafting shop in Kyoto in 1590, twenty-five years before the beginnings of the Mitsui group. It was Sumitomo that most quickly reorganized after the war and is considered, along with Mitsubishi, to be the most closely integrated. It has the smallest nucleus set of firms-the twenty firms in its presidents' council. At the other extreme in age and size is the Dai-Ichi Kangyo group. The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, which serves as the core financial institution in the group, was formed from a merger in 1971 of the former Dai-Ichi Bank-Japan's oldest, dating back to 1871-and Nippon Kangyo Bank. In 1977 Dai-Ichi Kangyo was the last of the six groups to formalize a presidents' council. It is sometimes considered representative of a new type of alliance that may replace the relatively tightly interlinked former zaibatsu-a more loosely organized arrangement, involving an extended and rather motley collection of former

independent firms and prewar zaibatsu remnants. These form the largest set of core organizations, with forty-seven firms participating in the group's presidents' council.

Moving beyond Caricature: Alliances as Process versus Pattern

The identifiability of membership in the keiretsu and visibility of the presidents' councils has led at times to an oversimplification of the relationships among affiliated companies. For some, the contemporary groups are not very different from the centrally controlled industrial conglomerates their prewar zaibatsu counterparts are presumed to have been (foreign observers are especially prone to this assumption). Perhaps in response, the opposite argument has also been put forward, namely, that those groups are really nothing more than social dubs and have no real economic impact. The sharing of common names or participation in a group presidents' council or a supplier association is seen as unrelated to companies' actual business relationships. Both of these views caricature reality and overlook the possibility of intermediate forms existing between internal hierarchy or arm's-length markets. Yet this is exactly where the keiretsu must be understood: as a combination of firm-level decision-making units and intercorporate coordination and constraint.

Consider this second view in more detail. The argument that the keiretsu are economically unimportant, which is often heard in response to foreign complaints about "structural barriers" in Japanese markets, generally relies on one of two sources of support. The first is that, because affiliated companies carry out trade with companies in other groups in varying orders of magnitude, alliance identity must not be important to understanding Japanese markets. This is an odd argument. If one were to apply the same logic to the firm, one might very well conclude that because individual companies source a portion of their supplies externally, the firm itself is irrelevant as a unit of internalized exchange. But are the automobile companies introduced at the beginning of this chapter that rely on outside suppliers for 80 percent of the added value in production therefore themselves unimportant in the process? While few would agree with this view concerning the firm, it seems to carry weight when applied to aggregates of firms such as the keiretsu. These are apparently expected to be self-contained. However, the real issue is not whether transactions take place across organizational interfaces (whether at the firm or the keiretsu level), for surely

such transactions are inevitable but, rather, how transactions "inside" differ from those "outside."

The reality of contemporary Japanese industrial organization is neither complete openness, nor complete insularity. Instead, it occupies a complex middle ground based in preferential trading patterns that rely on probabilistic rather than deterministic measures and models. While trading within groups is not exclusive, actual empirical patterns are far too biased toward own-group firms to be explained away as minor deviations from otherwise-anonymous market transactions. As I demonstrate in the following chapter, Japanese business networks are strongly organized by keiretsu relationships across three types of ties (dispatched directors, equity shareholding, and bank borrowing) and more weakly organized in a fourth (intermediate product trade).[13]

A second and related argument against the significance of the keiretsu is that, because only a relatively small number of firms are formal members of keiretsu, alliance affiliation does not have important economic consequences. As with the previous argument, this position relies on a false dichotomy, equating the lack of formal affiliation in one of the major groupings with true independence of operation. Research on the keiretsu has been hampered by stylized models of boundaries based on a priori categories of membership. Utilizing instead network data that map relationships across all large public Japanese corporations, I demonstrate in Chapter 5 that network structures characterizing the most formalized keiretsu actually pervade the networks of linkages among other Japanese firms as well. Whether companies "belong" to one of the prominent intermarket groups or not (itself a relative notion), they share the following common characteristics: (1) ties are durable-leading equity and debt ties endure over periods of decades; (2) ties are multiplex-equity and directorship interlocks are linked to debt and trading positions; and, (3) ties are mutual-share crossholdings and other forms of business reciprocity are common among networks of large corporations. Alliance forms are therefore far more prevalent in the Japanese economy than widely acknowledged, and correspondingly more important.

More recently, a somewhat different argument has received attention. This is the view that, even though the keiretsu may have at one time been significant, traditional group structures are now breaking down. Although this perspective does receive some support in the changes occurring in new technology development, capital financing, and internationalization, the idea that this represents a fundamental transformation

is greatly exaggerated. Evidence used in support is largely anecdotal; where rigorously measurable relationships are considered, these changes appear far weaker. We do find in the following chapters that Japanese companies are increasing the number of tie-ups with firms outside their traditional groupings. But this is not new: corporate growth through expansion of business partners has long been characteristic of Japanese industrial organization, even during the prewar period; indeed, this represents one of the key differences between Japan's historical reliance on the spinning off of operations and the reliance in the United States on intrafirm divisionalization. Regarding capital market changes, the fact that large Japanese companies are relying on banks less than they used to for loans is true so far as it goes. But this must be balanced against a recognition of the predominance of equity financing during much of the prewar period as well, and of the increased role of banks in equity markets and the "keiretsu-ization" of medium-sized firms that are themselves affiliated to large keiretsu parent companies.

What, then, about the ongoing trends toward internationalization and liberalization of the Japanese economy? Japanese firms have long sought to stabilize their external environment in the face of dramatic shocks and restructuring. If the past is a reliable guide for the future, therefore, these trends could actually have the opposite effect from that predicted. In the market for corporate control, at least, firms have used new threats imposed by hostile outside interests as a rationale to strengthen alliances with selected affiliate-shareholders. The apparent chinks in what seems a formidable wall around Japan's markets for corporate control in the 1980s (these include Merck's acquisitions of the Banyu and Torii pharmaceutical companies and the recent buyout of Sansui Electric by Britain's Polly Peck) have actually proven how formidable that wall remains: these were acquisitions of failing operations, not promising growth companies.[14] In short, as we see in the following chapters, while specific patterns of relationships in Japan are gradually evolving, there remains an important continuity in the underlying processes of alliance formation.

CONCLUSION

Since organizational actors represent the most stable and powerful participants in contemporary community life and those with the greatest access to resources, economic action in industrialized countries is largely defined by organizational and interorganizational relationships. Where

the key decision makers are corporations, as in capitalist systems, this leads to the study of intercorporate networks. This chapter has outlined basic characteristics of business network organization in Japan, as well as introducing the database used in the following chapters through a set of comparative analyses of ownership networks in Japan and the United States. We also considered several social frameworks that organize these networks in Japan, noting in particular the prevalence of intercorporate alliance forms.

The overall richness of interorganizational linkages in Japan reinforces the emerging view that Japan, like its East Asian counterparts, can be usefully thought of as a "network economy" (Hamilton and Biggart, 1988; Lincoln, 1989; Imai, forthcoming). That is, processes that take place at the level of the Japanese firm have been combined with processes that integrate firms at the interfirm level. The basic dynamic in Japanese industrial evolution has been the spinning off of new satellite firms from a central set of operations while organizing these firms collectively under a higher-level capital and control system. In the following chapters, we study in detail how this dynamic works in organizing the large firms that make up Japan's economic core.

CASE STUDY: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SUMITOMO GROUP

In order to provide a sense of the context within which the intermarket keiretsu arose, we consider here in broad overview the history of a single group, Sumitomo.[15] An outline of this history is presented in Table 3.3.

Sumitomo's history is an intertwining of families, political events, and economic development over the course of nearly four centuries. It is a story of both stability and change: change in the form of the growth, development, and transformations of Sumitomo from a tiny shop to a world-class, diversified group; stability in the traditions of the Sumitomo family, as seen in the following passage from the official Sumitomo history, describing a ritual ceremony among affiliated companies that continues even today:

Every year, on April 25, members of the Sumitomo family and the chief executives of the companies of the Sumitomo Group gather at Hosendo Hall, dedicated to the family's ancestors and past employees, in the city of Kyoto. There they conduct a solemn memorial service for the past family heads and for those who have contributed to the development of the Sumitomo enterprises.

TABLE 3.3. OUTLINE | |

Date | Event |

1590 | Soga Riemon founds Izumi-ya, a copper-crafting shop in Kyoto. |

Early 1600s | Riemon develops first process in Japan for extracting gold and silver from copper ore. Izumi-ya prospers. |

1652 | Sumitomo and Soga i.e. (households) fully merge as Riemon's son, Tomomochi, becomes official head of Sumitomo. |

1691 | Sumitomo buys Besshi mine in Shikoku. This becomes the most profitable mine in Japanese history and the main source of Sumitomo revenue or the next two centuries. |

1700s | Sumitomo maintains position as world's largest producer and exporter of copper. |

1868 | Meiji Restoration. Sumitomo struggles to downplay old ties to the shogun. |

1895 | Sumitomo Bank is started. |

1896 | Sumitomo Honten begins as holding company to oversee expanding operations. |

Early 1900s | Sumitomo expands into other businesses by starting Sumitomo Steel Casing, Sumitomo Electric Wire, Sumitomo Chemical, as well as other satellites. |

1937 | Sumitomo Honsha is incorporated. |

1948 | Sumitomo Honsha is dissolved under Occupation. Sumitomo name is dropped from companies. |

Early 1950s | Sumitomo name is readopted by most Sumitomo companies. Hakusui-kai (presidents' council) is formed, and group companies increase their shareholdings in other group companies. |

1956 | Sumitomo's first major postwar group project, Sumitomo Atomic Energy, is formed. |

Present | Sumitomo, now a well-established group with twenty core members and dozens of peripheral members, is involved in a diversity of projects. |

Period I. The Early Years (1590-1868)

In 1590, Soga Riemon opened a copper-crafting shop in Kyoto, calling it Izumi-ya. (Izumi means spring or fountainhead, and ya is a suffix added to shop and inn names.) At this time, Riemon adopted as Izumi-ya's emblem the igeta , or well frame, which is typically placed around a spring (see Table 3.2). This symbol was registered in 1885 as the Sumitomo trademark and is still used by the Sumitomo group and its core companies as their logo.

Riemon was not a blood connection to the Sumitomo family, but he was married to one-to the elder sister of Sumitomo Masatomo, a Buddhist priest and the spiritual leader of the family at that time. The ties between the Soga clan and the Sumitomo clan were further strengthened by the adoption of Riemon's eldest son into the Sumitomo clan. In the meantime, the expansion of Izumi-ya (at this time just a small shop) was made possible by Riemon's development in the early 1600s of a process for extracting gold and silver from copper ore. Riemon and his process prospered as he expanded first into copper refining, then later into copper trading and mining. Riemon's son Tomomochi, adopted into the Sumitomo family, started a branch of Izumi-ya in Osaka in 1623. There the family copper-refining business flourished, as Osaka was rapidly replacing Nagasaki as Japan's main center of commerce.

Tomomochi's Izumi-ya eventually absorbed a shop started by Sumitomo Masatomo under the name of Fiji-ya, as well as the original Izumi-ya in Kyoto, which was being run by Riemon's second son. Tomomochi took over as head of the Sumitomo family in 1652. In this way, the two clans-Sumitomo and Soga-fully merged. The copper refinery Tomomochi built in Osaka became the center of Japan's copper industry and remained so throughout the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), though it never grew beyond a peak employment of several hundred workers. The Sumitomo family became quite wealthy and politically influential during this period. Sumitomo and other Osaka copper interests were benefiting from a decree by the shogun that all copper for export had to be refined in Osaka, apparently as a control measure to ensure that the valuable silver was indeed being fully extracted from the ore. Copper mining and production expanded rapidly during this period in Japan as a whole, and Sumitomo grew accordingly. In order to control fierce competition among the increasing number of rivals, the shogunate restricted copper trade to sixteen members of the copper guild. Of these, ten were from Osaka and four were Sumitomo family members. By the 1670s, Sumitomo controlled one-third of Japan's copper export trade, already the world's largest.

Sumitomo's full-scale entry into the copper-mining business came in 1680 with its purchase and rehabilitation of the dilapidated Yoshioka mine in Okayama Prefecture. With its other mining interests, this acquisition made Sumitomo the leading private mining enterprise in the country. In a move a decade later that was to prove perhaps the single most important event in its history, Sumitomo purchased rights in 1691 to a promising mining site in Besshi (Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku). The Besshi mine was to be the most productive mine in Japanese history over

the next two-and-a-half centuries, and the continuing lifeblood of Sumitomo's existence.

Period II. The Development of Sumitomo Zaibatsu (1868-1945)

The greatest threat to Sumitomo as an ongoing entity came following the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Sumitomo was closely connected to and privileged by the shogun-its Besshi mine operated on land controlled by the shogunate, and received low-priced rice for its mine workers and special trading concessions. These ties were to prove detrimental in collecting debts from former warlords who had fallen out with the shogun. At the same time, commodity prices were dropping dramatically, and the Sumitomo family discussed selling the Besshi mine to finance their debts. They were swayed away from this, however, by the manager of the mine at the time, Hirose Saihai. Hirose argued, with great prescience, that the mine could, with work, continue to be Sumitomo's core operation (its "cash cow," in contemporary vernacular). Hirose introduced Western technology into the mine and turned what had been a dying enterprise into the mainstay of the expanding Sumitomo group, quintupling output in just over two decades. As a reward, he was made director general of Sumitomo headquarters, becoming the first in a Dine of nonfamily, professional managers to run the Sumitomo group.

Apart from a venture in the commodity mortgage loan business and several short-lived attempts to enter textiles and camphor, Sumitomo remained during the first several decades of the Meiji period primarily a copper business, focused on its Besshi mine. It was not until Hirose was succeeded by his nephew, Iba Teigo, and Sumitomo was again on solid financial ground, that Sumitomo took advantage of the opportunities the Meiji period afforded for the entrepreneurially inclined and true diversification took place. Iba started the Sumitomo Bank in 1895, among other smaller enterprises. The third professional director general, Suzuki Masaya, presided over Sumitomo's expansion in coal mining, fertilizer manufacturing, and other enterprises during the early 1900s. A succession of professional managers followed in the interim between the two world wars, and with them came aggressive diversification by Sumitomo into life insurance, trust banking, and various manufacturing industries, notably steel, electrical products, and glass. It was during this period that most Sumitomo companies came into existence, as shown in the Sumitomo "family tree" in Figure 3.7.

The Commercial Law of 1890 established three types of company

Fig. 3.7. Sumitomo Family Tree. Source: Asano (1978). Note: The chart depicts the

evolution of the core firms in the present-day Sumitomo group. Startups are

counted from their first listing as stock companies.

Image has been moved to previous page

forms in Japan: the general joint stock company, the limited partnership (goshi ), and the unlimited partnership (gomei ). The zaibatsu, as a rule, adopted the joint company form for their operating companies and either the limited partnership or the unlimited partnership form for the holding company. In 1896, the Sumitomo family constitution was changed in order to establish a holding company (Sumitomo Honten) assigned the role of overseeing the operating companies. This headquarters was given the form of a limited partnership in 1921 with a total capital of ¥ 150 million. The titular president of Sumitomo Goshigaisha, as it was now called, was the head of the Sumitomo household, Sumitomo Kichizaemon. Kichizaemon, however, delegated actual management duties to the director general at that time, Suzuki Masaya. The head office required that all companies submit plans for equipment investment and operations to the office annually before the fiscal year began. These were reviewed by the head office and adjusted to take into consideration the entire zaibatsu before being submitted for the approval of the board of directors (rijikai ). Control was strict. The head office expected monthly and ten-day reports from the operating companies. Detailed regulations were incorporated into the Sumitomo Kaho (family constitution and company manual) and later into the Shasoku (a revised version of the Kaho ). The general financial controlling function was performed by the accounting department and the accounts section of the general affairs department of the head office.

The organizational structure of the zaibatsu in the 1920s was comparatively straightforward. The head office collected the surpluses from its operating companies and allocated funds in businesses it thought would be profitable. Where Sumitomo Goshigaisha ran short of funds, it borrowed them from its financial institutions, especially from the Sumitomo Bank. The method of capital allocation within the zaibatsu, therefore, involved loans to and deposits from member companies, directed through the head office.

Perhaps the key issue facing every zaibatsu at the time was how to balance the desire to expand business while maintaining control over the operating companies. Sumitomo only gradually and cautiously transformed its enterprises into joint stock companies. Sumitomo Bank (started in 1895) became a joint stock company in 1911, Sumitomo Metal Industries (1901) in 1915, and Sumitomo Electric (1911) in 1920. However, the shares of most of these companies were not publicly issued, but rather were held by other Sumitomo companies. During the prewar period, only five firms (though among the largest) opened shares

to the public-Sumitomo Bank (in 1917), Sumitomo Trust and Banking (1925), Sumitomo Chemical (1934), Sumitomo Metal Industries (1935), and Sumitomo Electric (1937)-and ownership and capitalization were carefully controlled. Other enterprises such as coal mining and sales, copper drawing, and chemical fertilizer remained under direct management of the headquarters. Sumitomo Kichizaemon himself owned 98.7 percent of Sumitomo Goshigaisha in 1927, as well as major portions of six subsidiaries. Operating control, however, was delegated to professional managers hired by the family, who simultaneously served as the board of directors.

Movements to the joint stock form appear not to have been for the purpose of raising outside capital, for nearly all shares were still held by the Sumitomo family and the head office. The system of finance was still dosed. Rather, it seems they were a means of gaining control over subsidiaries akin to the purposes of the modern-day profit center. Yasuoka (quoted in Asajima, 1984, p. 113) argues that the joint stock company form in the zaibatsu at the time served to "rationalize the holdings and management of the various enterprises" and to "organize a system that can expand to giant size." Similarly, Masaki (1978, p. 33) suggests that "what the zaibatsu tried to stress was not the capital-raising function but the control-concentrating function of incorporation."

A second advantage of public incorporation was in diffusing public opinion, for the 1930s were marked by periodic public outcries against the zaibatsu and their dosed financial system. The increasingly powerful military was dubious about what it perceived as competition for power and pressured the zaibatsu into increasing donations to public works projects. That the zaibatsu were sensitive to public pressure is indicated in the public explanation given by the Mitsubishi zaibatsu for the opening of one of its subsidiaries, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, to the public in 1934. It stated that it was going public for the purpose of "avoiding monopoly of profit by a few rich families and making the company open to the general public" (quoted in Masaki, 1978, p. 46). Public offerings, then, were one means of diffusing this pressure by opening the group, albeit nominally, to outside capital.

Sumitomo Goshigaisha was incorporated as Sumitomo Honsha in 1937, though its shares were never offered to the public (they remained in the hands of family members). Ironically, given earlier right-wing animosity, the zaibatsu prospered during the next eight years as a result of the military war effort. Sumitomo companies which were benefiting from military demand (Sumitomo Metal Industries, Sumitomo Chemi-

cal, Sumitomo Industries, etc.) increasingly needed to rely on sources of funds other than the head office. These were primarily loans from Sumitomo Bank and other Sumitomo financial institutions and external loans from special financial institutions, in particular the Bank of Japan. Funds from other city banks were rarely used. In this way the external funds that were introduced would not disturb the internal control structure of the zaibatsu. It was a system that depended on and was made successful by deposits from the general public and borrowings from government-controlled sources.

Companies also offered equity shares, but again, not for the purpose of gaining outside capital. These tended to be limited to "friendly" shareholders-primarily other subsidiaries and zaibatsu family members. Life insurance companies were important holders since they were expected to have no desire to control other companies. Employees and their relatives were also offered shares. Masaki (1978, p. 46) reports that Mitsubishi was quite explicit that their shares were not a publicly tradable commodity, issuing shares in 1928 with the following proviso: "Since these stocks are offered for a long-term investment, such action as immediately selling them should be abstained from in the light of moral obligation to the company. If it is necessary, however, to sell them, inform the head office beforehand so that we can buy them back at the selling price."

Period III. The Dissolution (1945)

The ownership structure of Sumitomo at the time of zaibatsu dissolution is indicated in Table 3.4. The dominant shareholder of most group subsidiaries was the holding company, Sumitomo Honsha, and the dominant shareholder of the holding company itself was the Sumitomo family (particularly the head of the family, Sumitomo Kichizaemon), which held 83 percent of the shares at the end of the war. In addition, some cross-holdings existed among the subsidiaries themselves (e.g., Sumitomo Bank's 40 percent stake in Sumitomo Trust and Banking).

With Japan's defeat in World War II and the subsequent arrival of U.S. Occupation Forces came a major overhaul of the Japanese economy as a means toward economic democratization. The most important measures from the point of view of the zaibatsu were the dissolution of the holding companies, the elimination of family assets held in the zaibatsu, the removal of many top executives from first-line subsidiaries, and the breakup of a number of leading zaibatsu companies (Hadley, 1970). The

TABLE 3.4. SUMITOMO GROUP | |||||

Shareholder | |||||

Issuing | Sumitomo | Sumitomo | Sumitomo Bank(%) | Other Sumitomo Companies (%) | Total Sumitomo Holdings (%) |

Sumitomo | 83.3 | 83.3 | |||

Sumitomo | 11.3 | 24.1 | 16.7 | 52.1 | |

Sumitomo | 2.8 | 1.5 | 40.2 | 0.5 | 45.0 |

Sumitomo | 2.6 | 17.0 | 19.6 | ||

Sumitomo | 53.4 | 26.6 | 7.0 | 14.0 | 100.0 |

Sumitomo | 4.3 | 20.9 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 39.7 |

Sumitomo | 4.7 | 24.3 | 1.0 | 8.2 | 38.2 |

NEC | 2.0 | 11.1 | 0.2 | 6.5 | 19.8 |

Nippon Sheet | 4.6 | 19.2 | 0.4 | 24.2 | |

Sumitomo | 7.3 | 17.5 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 31.5 |

Sumitomo | 7.2 | 21.0 | 69.0 | 97.2 | |

SOURCE : Calculated from data provided in Nihon zaibatsu to sono kaitai (reproduced in Futatsugi, 1976, pp. 52-55). Note: All of the above are current company names. | |||||

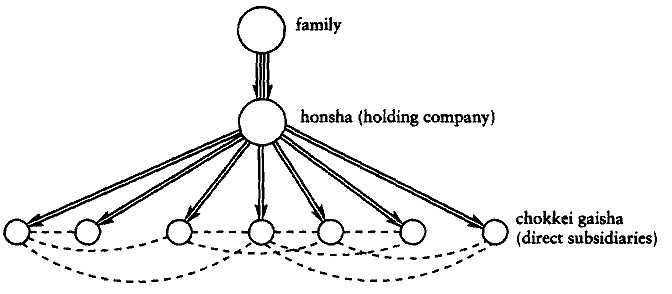

changes in group structure wrought by the dissolution are depicted schematically in Figures 3.8a and 3.8b. With dissolution, family ownership connections to the honsha (as well as its smaller holdings in the subsidiaries) were eliminated. So too were honsha connections to the direct subsidiaries, or chokkei gaisha.

Fig. 3.8a. Prewar Zaibatsu Pattern of Ownership and Control.

Fig. 3.8b. Postwar Keiretsu Pattern of Ownership and Control.

This left only intersubsidiary connections intact, but these intersubsidiary crossholdings provided an important infrastructure on which to rebuild the groups in the 1950s. The subsidiary companies became the nucleus around which the present-day groups are based, and most have become substantial enterprises in their own right with their own networks of subsidiaries (kogaisha) and satellite firms ringing their periphery. From the prewar zaibatsu, then, came the beginnings of the postwar groups.