Fish Slough

a Case Study in Management of a Desert Wetland System[1]

E. Philip Pister and Joanne H. Kerbavaz[2]

Abstract.—Fish Slough is a remnant of a once-widespread, shallow aquatic/riparian wetland in the arid Owens Valley (Inyo and Mono counties, California). Fish Slough supports a variety of rare species, including the endangered Owens pupfish. Successes and failures of management efforts at Fish Slough should hold lessons for management of other endangered species and natural areas.

Introduction and Background

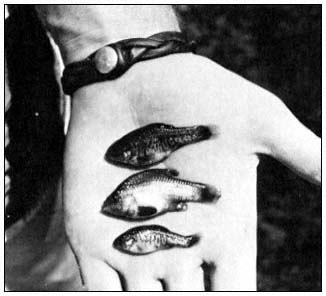

The first recorded observation of the Owens pupfish (CyprinodonradiosusMiller ) (fig. 1) occurred in 1859 when Captain J.W. Davidson of the US Army described vast numbers of pupfish throughout the wetland areas of the Owens Valley (Inyo and Mono counties, California). So abundant were the small cyprinodont fishes that local Indians would seine them with woven baskets and dry them in the sun for winter food (Wilke and Lawton 1976).

Figure l.

Owens pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus Miller). From top

to bottom: adult female, adult male, subadult female.

Pupfish numbers remained high until at least 1916, when Clarence H. Kennedy, a student from Cornell University, observed large schools of pupfish in the numerous sloughs and swamps between Laws and Bishop (Kennedy 1916). Their time was short, for already severe changes were being effected which would bring about an enormous reduction in the once-abundant wetlands that support this fish. Numbers would be reduced to a point where, when described as a species in 1948, the Owens pupfish would be thought to be extinct (Miller 1948).

The investigations of Carl L. Hubbs and Robert R. Miller during the 1930s and 1940s revealed that because of reduction in surface water supplies, the habitat (and the fish) was progressively becoming reduced in extent. Its remnant habitat was being reduced and confined to the "type locality," that location from which the species was originally collected for official taxonomic description. This locality was described by Miller (ibid .) as: "the northwestern feeder spring of Fish Slough, about 10 miles north of Bishop, California." Today this location is a portion of the Owens Valley Native Fish Sanctuary.

Probably the major factor involved in such severe habitat reduction was the development and export of Owens Valley water to supply burgeoning populations in Los Angeles (Heinly 1910). Then, in later years dams were constructed to retain waters that, during and since the Pleistocene epoch, had periodically covered the Owens River floodplain and created ideal habitat for native fish populations. Nearly as damaging as water development and export, and occurring during this

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981.]

[2] E. Philip Pister is Fishery Biologist, California Department of Fish and Game, Bishop, Calif. Joanne H. Kerbavaz is Environmental Planner, California Department of Transportation, Bishop, Calif.

same general time period, was the introduction of predaceous gamefishes and other exotic species, including the western mosquitofish (Gambusiaaffinis ), which preyed upon and competed with a constantly decreasing pupfish population (Pister 1974).

As habitat was reduced and populations of competing and predaceous fishes grew, the pupfish was gradually pushed to its final toehold in the marshlands of Fish Slough (Miller and Pister 1971). It is significant to note that among four native fishes in the Owens River system, two are listed as endangered (Owens pupfish and Owens chub [Gila bicolorsnyderi ]) and one is threatened (Owens dace [Rhinichthysosculus ssp.]). Only the Owens sucker (Catostomusfumeiventris ) remains in substantial numbers (Pister 1981).

Preservation and Management

Following rediscovery of the Owens pupfish in 1964, thought began to be directed toward its management. Inventories of all fish populations began to be worked into general management plans of the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG), which had up to that time been so completely dedicated to gamefish management that any species not possessing adipose fins or spiny rays became an immediate candidate for eradication (Pister 1976). Suggestions for preserving such things as snails and plants met with derision. Problems of preserving all life forms at that time were more political than biological (Pister 1979).

Changes in the natural character of the Owens Valley continued through the next decade, largely manifested in the loss of spring ecosystems (and their associated flora and fauna) through increased groundwater extraction. This gradual change was accompanied during the 1960s by at least two instances during which pupfish populations in natural habitats thought to be secure were nearly lost.

So on June 26, 1967, when Carl Hubbs, Bob Miller, and Phil Pister met at Fish Slough to consider the possibility of creating refugia for the native fishes of the Owens Valley, their thinking went well beyond that. It was becoming disturbingly clear that the remaining aquatic wetland in Fish Slough was the only area in the entire Owens Valley retaining even a semblance of the magnificent ecosystem that existed before the coming of Europeans. More than fish refugia were needed. Aquifers supplying the springs had to be protected, and private inholdings had to be acquired to minimize further impact on the Fish Slough ecosystem.

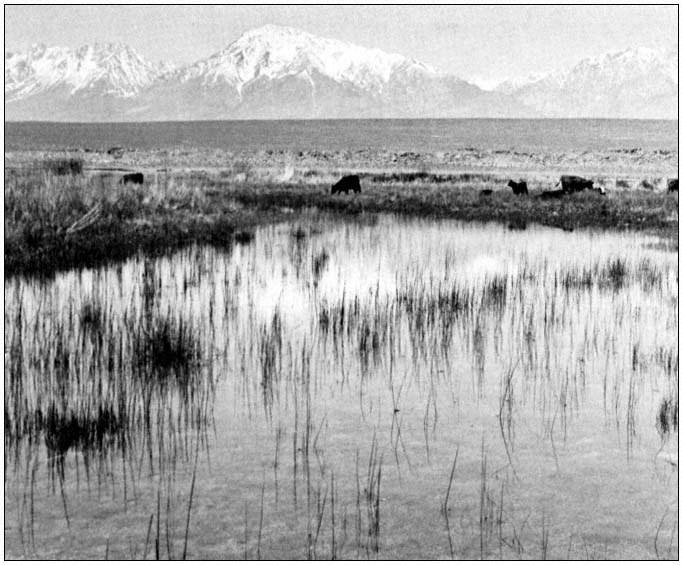

The first priority was preservation of the Owens pupfish. Refugia were constructed at two locations in Fish Slough in the early 1970s. Designed to prevent the invasion of introduced predatory fishes that abound in Fish Slough, the refugia attempted to recreate the conditions under which the native Owens Valley fishes evolved (Miller and Pister 1971). The refugia have been successful in protecting the native fishes, and in 1980 the Owens Valley Native Fish Sanctuary (the first refuge constructed) was expanded to enhance Owens pupfish habitat (fig. 2). Current status and recovery efforts for the Owens pupfish are summarized by Courtois and Tippetts (1979).

Public resistance to the creation of a native fish sanctuary is not widespread, but certainly exists. Fences have been cut, signs torn down, and largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides ) frequently (and illegally) planted into the refuge area. Such actions, although frustrating, only serve to strengthen our resolve to protect the entire ecosystem under a comprehensive management plan.

The Fish Slough Refuge

Fish Slough, with its permanent water sources, is an aquatic anomaly in an arid valley and a remnant of a once-widespread shallow wetland. As such it supports a variety of rare species, including the pupfish, an undescribed snail, and at least six rare plants, as well as a dense concentration of cultural sites. It is not just the species and the cultural resources that are rare, it is the wetland with its aquatic and riparian systems.

Ownership boundaries in Fish Slough do not correspond with natural boundaries. As in most of the Owens Valley, much of the actual riparian land is owned by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). The USDI Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers land with one of the slough springs and manages most of the surrounding dry shadscale scrublands. There were two private inholdings in Fish Slough. DFG acquired a 64.8-ha. (160-ac.) parcel at the mouth of the Slough in the mid-1970s. The other parcel, 81.8 ha. (202 ac.) about 1.6 km. (1 mi.) southwest of the main slough springs, remains in private hands.

Of the riparian landowners, only DFG has the luxury of managing its lands exclusively for the benefit of the pupfish and the desert riparian system. The LADWP is concerned with developing and maintaining water supplies for export; this concern can conflict with needs for water for instream and riparian uses. BLM labors under a multiple-use mandate and must balance competing human needs and resource values.

Beyond the landowners, additional state and federal agencies and organizations have an interest in Fish Slough. Foremost among them has been the University of California Natural Land and Water Reserves System (NLWRS). The NLWRS, as part of an effort to preserve unique natural systems throughout the state for teaching and research, attempted to purchase the 81.8-ha.

Figure 2.

Prime Owens pupfish habitat, looking west across Fish Slough to the Sierra Nevada.

private inholding during the 1970s. These attempts were not successful, but the NLWRS Systemwide Advisory Committee and staff continue to support efforts to obtain the inholding and establish a reserve.

To reconcile varying interests and develop an effective management program, representatives of the three landowning agencies and the NLWRS met in 1975 and drafted a cooperative management agreement. The agreement recognized the needs and responsibilities of the various agencies, as well as the need to manage Fish Slough as an ecological unit.

The cooperative agreement has allowed the continuing efforts of DFG to protect and enhance pupfish populations. But the native fish refugia and the desert riparian system cannot be considered secure while there are threats of development and changes in water supply for the slough.

In July 1979, the owners of the 81.8-ha. private inholding filed Tentative Tract Map 37-23 Zack with Mono County. They proposed creating the new housing subdivision of Panorama Tuff Estates, with 49 parcels ranging from 1.2 to 4.3 ha. (3 to 10.6 ac.) in size.

The immediate threat to the integrity of Fish Slough galvanized support for a refuge among the landowning agencies and other interested parties. They convinced the Mono County Board of Supervisors to defer action on the subdivision map and concentrated efforts on the acquisition of the parcel.

The present landowners object to increased government land ownership in the Owens Valley, an area where governmental agencies own an estimated 98% of the land. The owners refused to sell their land, but agreed to exchange the parcel in Fish Slough for developable land somewhere else.

BLM began negotiations to decide on parcels to exchange. Even when both sides agree that an exchange will be mutually beneficial, the exchange process is long and arduous. The process includes a series of agreements, appraisals, and approvals and requires the involvement of several levels of BLM hierarchy.

In the case of Fish Slough, the exchange requires, in addition, the proverbial "Act of Congress." As is the case on much of the public land in the Owens Valley, the parcel selected by the private landowners had been withdrawn for watershed protection for the City of Los Angeles. This withdrawal must be shifted to the parcel in Fish Slough. The necessary legislation, HR 2475, is pending.[3]

Interagency efforts have focused on the prevention of permanent damage to the slough. With the acquisition of the final private inholding, the involved agencies and groups can work towards the creation and management of a reserve to protect all of Fish Slough.

Lessons Drawn from the Fish Slough Case

The unique cooperative management efforts at Fish Slough to save an endangered species and a threatened ecosystem offer the opportunity to assess successes and failures and to draw lessons for the future.

One of the primary lessons taught by this case study is the reaffirmation of one of Murphy's Laws, that anything you try to fix will take longer and cost more than you thought. Attempts to remedy the effects of water diversion, habitat destruction, and unwise species introductions have required a significant investment of time and resources. This seemingly clear-cut case, the effort to preserve a universally recognized significant natural area, has taken almost 20 years to bring towards completion.

This case demonstrates the potential value of vigorous interagency cooperation. For this project, the pathways were primarily informal ones, built from common concern for protection of threatened resources. It would be difficult to plan in advance for cooperation like that needed for this project; however, it is imperative that land management agencies retain the flexibility to seek innovative, cooperative solutions.

Work to acquire the private inholding shows that we must develop and improve alternatives to fee acquisition in California. Money for land purchases is limited, and some landowners, unwilling to sell, may be interested in other alternatives.

The BLM land exchange process can be a valuable tool, especially in California's desert areas, to both eliminate inholdings and provide land more suited to development in less sensitive areas. The process is time-consuming and cumbersome, however, and many landowners have neither the time nor the patience to work with it.

Many authors have explored the alternatives to fee acquisition for the protection of natural resources (Hoose 1981). We must make it a priority to bring the best of these alternatives to fruition. We can start by making existing options, such as land exchanges, more workable.

Conclusion

Never before have the critical relationships between habitat integrity and species existence been brought so sharply into focus as during the 1970s, the decade of the endangered species preservation movement. The near extinction of the Owens pupfish and elimination of its desert wetland is just one example of a situation that is being repeated throughout the world, as natural resources succumb to short-sighted drives for economic development. The forces that reduced the pupfish populations and habitat from abundance to virtual disappearance in only three decades warrant sober and critical reflection.

Literature Cited

Courtois, Louis A., and William Tippetts. 1979. Status of the Owens pupfish, Cyprinodon radiosus (Miller), in California. Inland Fisheries Endangered Species Program Special Publication 79-3, California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, Calif. 31 p.

Heinly, Burt A. 1910. Carrying water through a desert. National Geographic 21(7):568–596.

Hoose, Phil. 1981. Building an ark: tools for the preservation of natural diversity. 217 p. Island Press, Covelo, Calif.

Kennedy, C.H. 1916. A possible enemy of the mosquito. Calif. Fish and Game 2:179–182.

[3] Editor note: Although HR 2475 was unopposed, the political process is unpredictable and laborious at best. HR 2475 finally passed on 19 December, 1982, just a few hours before Congress adjourned. Final details of the land exchange are in the process of completion, and no further obstacles are anticipated.

Miller, R.R. 1948. The cyprinodont fishes of the Death Valley system of eastern California and southwestern Nevada. Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 68:1–155.

Miller, R.R., and E.P. Pister. 1971. Management of the Owens pupfish, Cyprinodonradiosus , in Mono County, California. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 100:531–540.

Pister, E.P. 1974. Desert fishes and their habitats. Transactions of the American fisheries Society 103:531–540.

Pister, E.P. 1976. A rationale for the management of nongame fish and wildlife. Fisheries 1:11–14.

Pister, E.P. 1979. Endangered species: costs and benefits. In : The endangered species: a symposium. Great Basin Naturalist Memoir 3:151–158.

Pister, E.P. 1981. The conservation of desert fishes. p. 411–445. In : R.J. Naiman and D.L. Soltz (ed.). Fishes in North American deserts. R. J. Naiman and D. L. Soltz (ed.). 552 p. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Wilke, P.J., and H.W. Lawton. 1976. The expedition of Captain J. W. Davidson to the Owens Valley in 1859. 55 p. Ballena Press, Socorro, N.M.