Three—

The Oahu Strike Begins:

Honolulu: 1919–1920

When the United States entered the European war the country was in a skittish mood. In 1916 Woodrow Wilson had been reelected with the slogan "He kept us out of war." Unable to resist pro-war agitation after a German submarine sank a British passenger liner with many Americans abroad, in April 1917 the president declared the United States would go to war against Germany. A patriotic fever to "make the world safe for democracy" suddenly swept the country, and young men lined up to volunteer for military service, but the American labor movement was badly split in its reaction to the war. Without hesitation the American Federation of Labor had issued a declaration supporting entry into the war, and its president, Samuel Gompers, joined the advisory board of the Council of National Defense to align organized labor with national policy. As military demand heated up the economy, jobs were suddenly plentiful and unemployment dropped.

The radical wing of the labor movement, however, was adamantly opposed to the war. The Industrial Workers of the World, led by "Big Bill" Haywood, had already mounted an antiwar campaign, and the IWW joined with socialist, anarchist, and pacifist groups to condemn the country's entry into the European conflict. The IWW, whose organizers had been condemned as "outside agitators" when they rushed to join labor struggles wherever they could, was now branded as a nest of "foreign spies." Neither of the two anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, were official members of the IWW, but they had fled to Mexico to avoid the draft.

Suspicion of the radical wing of the labor movement, especially the IWW, with its reputation for confrontational strike tactics and sabotage activities, was deepened by the February 1917 revolution in Russia, then by the October revolution led by the Bolsheviks under Lenin. The IWW leadership was as quick to declare its support for the new Bolshevik government as it had been to condemn the American declaration of war against Germany. The federal authorities, made nervous by a rising number of large-scale strikes and labor demonstrations, marked the IWW as a target for investigation. In June 1917 Congress had passed the Espionage Act to crack down on spying and other acts abetting the enemy, and a year later amendments were added to limit free speech.

In the summer of 1917 the FBI raided the Chicago headquarters of the IWW as well as its local branches, seizing documents and any IWW leader they could lay their hands on. Several IWW members were lynched by company-hired detectives, the Ku Klux Klan, and right-wing patriots, and foreign-born labor leaders were deported. The IWW was hit hard. Haywood, an American and a Westerner to the core, so despaired of his prospects that he defected to the new Soviet Union while on bail and eventually died in Moscow.

Sen Katayama, who had returned to America in 1914 after his release from prison, where he was sent for his involvement in the 1906 Tokyo streetcar workers strike, sent a secret report on the situation in the United States to his socialist comrade, Toshihiko Sakai: "Several hundred IWW members have been seized. . . . However, though there is oppression, this is indeed a free country. We can work to collect donations for legal fees by advertising in magazines and newspapers, forming groups and holding speeches. This has become part of our movement."[1] Katayama was already persona non grata with the Japanese authorities in the United States. In 1915, despite a warning from the Japanese consulate, Katayama had denounced the credentials of Bunji Suzuki, the moderate labor leader of the Yuaikai[*] , who arrived from Japan to attend the AFL convention in San Francisco. Suzuki had been sent by Eiichi Shibusawa and other Japanese industrialists to promote friendly relations between Japanese and American workers in the face of growing anti-Japanese sentiment on the West Coast. In a speech to a meeting of the Japanese day laborers' union in San Francisco, Katayama described working conditions in Japan and said that Suzuki, bankrolled by Japanese capitalists, did not represent Japanese labor. Under pressure from the consulate, Katayama was forced to move to New York.

The Ministry of Home Affairs took note of Katayama's activities in its report on "dangerous persons": "Led by Sen Katayama and others, the Japanese socialists in the U.S. are using New York as their base of operations to further their plans to engage in coordinated actions with radicals." Already in his late fifties, Katayama continued to work as a dishwasher or cook while gathering around him youths who would later become active in Japan's socialist movements, including Tsunao Inomata, Mosaburo[*] Suzuki, and Eitaro[*] Ishigaki. He also published the magazine Heimin (Common Man). Gradually he drifted toward communism.

Before 1919, however, the Home Ministry reports on the "movements of Japanese radicals resident abroad" hardly mentioned the Japanese in Hawaii. This was because Katayama and other activists went directly to the mainland without staying in Hawaii.

There were also very few American files on "foreign agitators" in Hawaii. Given the power of the sugar plantation interests, there was little chance for the IWW to grow in Hawaii. Three years after the 1909 Oahu strike, white telephone operators from the mainland gathered Japanese workers of Waialua Plantation to urge them to join the IWW, but their talk of capitalists, exploitation, individual rights, and labor struggles rang unfamiliar to the ears of the Japanese, who themselves were wary of "suspicious outsiders." Another IWW organizer who arrived in Hawaii at about the same time took a job on the Kahuku plantation as a sugarcane worker, but he disappeared suddenly. It was rumored at the time that he was killed by plantation company agents, but the truth of the matter remains unknown to the present day.

Another reason that American government agencies paid little attention to the foreign laborers in Hawaii was that there were no significant labor movements after the 1909 Oahu strike. Since it ended with the defeat of the strikers, the solidarity among the Japanese laborers quickly dissolved.

The Rice Riots of 1918

In the latter half of 1917, in response to rising prices, demands for wage increases were heard once again in the Hawaiian sugar plantations. In 1918 a declaration demanding wage increases was issued by the joint youth organization on five plantations in the Hamakua area of the island of Hawaii. The consciousness of the young cane field workers was fired by the activities of mainland laborers roused by the Russian revo-

lution. Yet what made the greatest impact on these youths was the rice riots in their homeland.

During the wartime boom, prices in Japan rose and rice prices soared. The Terauchi cabinet proclaimed a policy of restraint on cornering the market, export prohibition, and control over rice imports, but the situation was out of control. Stockpiling of rice for the military in anticipation of the Siberian intervention caused the price of rice to rise even further. The rice riots began on August 3, the day after the Siberian intervention was announced. Fishermen's wives in the village of Uozu, Toyama prefecture, protested the shipment of rice out of the prefecture to Osaka. Protest demonstrations quickly spread throughout the country. The Honolulu Consulate General issued a notice that "due to the rice famine in Japan, imported Japanese rice should only be sold to Japanese." When he spoke to immigrant workers, Bunji Suzuki of the Yuaikai[*] was surprised to find that they were eating high-quality Japanese rice from Yamaguchi and Kumamoto prefectures. No matter how strained their budgets, they wanted Japanese rice on their tables. It was not surprising that they reacted with panic when they heard that the supply would be depleted two months after the consulate's warning.

In Hawaii the price of rice jumped to twice what it had been the previous year. When it was revealed that the four large trading companies with headquarters in Japan had been hoarding rice in Hawaii, rumors flew that the four shops were going to be "wrecked." Not only rice prices, but the prices of other indispensable imported Japanese foods—soy sauce, miso, dried fish, pickled ume plums, pickled daikon radishes—had risen sharply in the half year after Noboru Tsutsumi had arrived in Hawaii. One Japanese-language newspaper called for "the overthrow of the pickled daikon millionaires."

News of the rice riots had as much impact on the Japanese in Hawaii as the Russian revolution had on Japanese leftists like Sen Katayama in New York. A few, believing that revolution was afoot in Japan, immediately prepared to return home. The riots affected Japanese of all social classes. What finally brought together the Japanese laborers working in the cane fields was the impact of the protest by fishermen's wives and tenant farmers in Japan, who like themselves were at the bottom of society.

The time was ripe for action, but it was Noboru Tsutsumi who put the anxious feelings of the Japanese immigrant laborers into words and who encouraged them to organize. The cane field workers lived in camps on the plantations, bought items necessary for their daily lives from

the stores operated by the plantation companies, and deducted those charges from their wages. It was a life in which food, clothing, and shelter were all controlled by the company. Tsutsumi summarized the awakening consciousness of the workers: "When the company behaves in such an autocratic manner controlling production, livelihood, and society, the workers' spiritual life is never calm. This is because human beings have in themselves a constant desire for freedom. Even in the face of uncertainty, they do not like interference and restriction by others." The immigrants, he said, were about to "become self-aware of their position in society" under the stimulus of the "trends in the labor world."

Tsutsumi put words in the mouths of the workers:

To live in society as a human being. These times compel me to realize that I am a laborer. The sunlight of democracy shines and labor groups are blossoming. I'm the same as other human beings, so I would like to pluck the beautiful flowers of real society. . . . There were at least a few who realized this and many more who were about to come to this realization.

If the company cannot survive because the price of sugar is low, we could understand the need to help each other and would put up with eating rice gruel. But at a time when the price of sugar is going from $60 a ton to $80, then to $100, to $150, and to more than $200, our bosses are full of idle talk that they are flush, have money left over, are getting large dividends; and they're lording it over us by living in grand houses and riding around in big cars.

It's not as if we had drawn our fortune from the gods that we would ho[*] hana [do hoeing work] all our lives from the time we come bawling into this world. We must do something to be able to bear it. If we stay quiet, no matter how many years go by we will stay sunk like a hammer in the river and we will not be able to raise our heads in pride. Brothers, let's think about this. Laborers threatened by economic distress are forced to consider their present circumstances and the future of their descendants.

The single word pau [finished; fired] ruins the foothold gained over several decades, forcing a household to keep from uttering it. The bosses are trying to oppress us by treating us as they treated government contract immigrants or ignorant laborers in the past. This is unacceptable to progressive thinking youths and laborers who are in touch with current trends. And yet, in the struggle between employer and employee, we are weak as individuals.

Using the plain words spoken by cane field workers, Tsutsumi captured their attention, and he eventually won their admiration and absolute trust as well.

Through his eloquence, Tsutsumi played the role of standard-bearer for the cane field workers. Liberated from the constraining social structure of Japan and his status as adopted son-in-law, he was feeling more

freedom than when he rode horses across the Kyoto Imperial University campus. The struggles of the workers gave his life a goal.

The year 1919, after the rice riots had subsided in Japan, saw unprecedented labor struggles throughout the United States; 3,630 strikes were carried out by some 4.16 million workers. This was twice as many strikes as in 1916. The biggest reason for the strikes was the economic hardship that accompanied the increased cost of living. In February 1919 a shipyard strike in Seattle turned into a general strike, crippling the entire city's services. After that was settled, a San Francisco Stevedores' Association strike in May sparked other strikes in Los Angeles, San Diego, and other ports on the West Coast. Streetcar strikes occurred in Denver, Chicago, and Nashville; and in September telephone operators and police struck in Boston. At year's end there was a great steel strike by 370,000 steel workers in fifty cities in ten states, centered in Pittsburgh. Federal troops and state militia engaged in bloody clashes with the workers.

The news of these strikes was reported in detail in Hawaii's Japanese-language newspapers. Since Hawaii was dependent on the mainland for many necessary goods, strikes on the West Coast delayed shipments for months and had a great impact on daily life. In 1919 there were eight small-scale strikes in Hawaii.[2] Two were longshoremen's strikes; the others involved telephone operators, machinists, lumber workers, and golf caddies. Japanese carpenters and plasterers also protested wage cuts proposed by the Japanese Contractors' Association, but this dispute did not turn into a major one.

In April 1919 the Japanese-language newspapers, led by Tsutsumi, began to discuss the cane field workers' demand for wage increases. The Hawaiian territorial government, however, did not show much interest in the issue. The workers' discontent was overshadowed by a series of local celebrations: in July, the centennial of the death of King Kamehameha; and in August, the opening of the U.S. Navy dry dock at Pearl Harbor on Oahu. The cane field workers' movement for increased wages and improved working conditions was gradually taking shape against the background of these festivities.

Formation of the Hawaii Federation of Japanese Labor

Of the 43,618 workers in all the sugar plantations in Hawaii, 19,474, or almost half, were Japanese. Filipinos constituted the next largest

group, with 13,061 workers, and it was they who first rose to demand higher wages. On August 31, 1919, at a rally of the Filipino Labor Union of Hawaii (initially called the Filipino Labor Association) in Aala Park in Honolulu, the Filipino laborers elected Pablo Manlapit as their chairman. A graduate of a mainland college, Manlapit was hired in 1916 by the planters' association to take charge of relations with Filipinos. He was fired when he was found to be recruiting workers to go to the mainland. He soon became a well-known figure among the Filipino laborers. He organized a longshoremen's strike on Maui, eloquently arguing down strike breakers despite being injured, and helped out Filipinos as an interpreter for the Honolulu police department. With his dark complexion and taut physique, Manlapit was an imposing man. After becoming president of the Filipino Labor Union, he started making the rounds of Oahu's sugar plantations campaigning energetically for a wage increase. From newspaper photographs, it is clear that Manlapit emulated the style of the IWW's Wobblies by making his speeches on a soapbox.

As recent arrivals in Hawaii, the Filipinos did not yet have their own schools or theaters. Refused the use of plantation meeting halls, Manlapit spoke at train depots on the outskirts of town. When he made a speech in front of a Japanese store at Waimanalo Plantation, he was arrested and held overnight by the police for gathering people on a private road. Undaunted, he not only continued his speaking tour but also took and passed the bar examination.

On October 15 Juan Sarminento, editor-in-chief of the Filipino newspaper Ang Filipinos , called for the presentation of a wage increase demand in late November. If no reply was received within a week, he said, then the three thousand Filipino workers in Oahu should begin a strike on December 1. Sarminento was a leader of a faction within the Filipino community that did not entirely trust Manlapit because he had worked for the planters' association in the past.

The unification of the Philippines is said to have been delayed in part by the division of the islands among ethnic groups using different languages, such as Visayan, Tagalog, and Ilocano. Filipino workers who went to Hawaii took these divisions with them, and the Filipino Labor Union likewise suffered continual internal discord. Nevertheless, at the union delegates' meeting on October 20, Manlapit was chosen president and it was formally decided to submit wage increase demands by December 1. Manlapit immediately went on a speaking tour of the islands,

pointing out that the success of the wage increase movement depended on the solidarity of workers throughout Hawaii.

On November 18 Manlapit arrived on the Big Island, which had been shaken by earthquakes for nearly two months because of an eruption of the Mauna Loa volcano. But the fiery lava flow had headed in the direction of Kona, on the opposite side from Hilo, and residents breathed a sigh of relief. The rally for the Filipino workers, which was held in the Gaiety Theater in Hilo, drew Spanish and Portuguese workers as well. As Manlapit toured the plantations after the meeting, Noboru Tsutsumi was always at his side, proclaiming the need for Japanese workers to support Manlapit's campaign. A month and a half earlier Tsutsumi had organized the Federation of Japanese Labor on Hawaii, the only island to organize.

The center of the Hawaiian Islands, however, was Honolulu on Oahu. One-third of Hawaii's population, many of them Japanese, lived in Honolulu. The city was a microcosm of "the Japanese village" in the middle of the Pacific. The downtown area near Alala Park was dotted with Japanese shop signs, and only Japanese was heard on the streetcars. On the streets Japanese women wore cotton yukata and wooden geta clogs. Those in Western-style dresses were a rarity.

Members of the Japanese Association in Honolulu, which was dominated by upscale shop owners, school principals, religious leaders, newspapermen, and other professionals, thought of themselves as the elite within the Japanese community. Taking the lead, the association joined with other groups to form the Plantation Labor Supporters' Association in Honolulu. It was made up of representatives from various occupational groups, including the craftsmen's union, the automobile association union, the barbers' association, the fisheries association, the pawnshop, cleaner, and tailor industries, the young men's association, and various prefectural associations. Of the twenty officers of the supporters' association, nine were newspapermen working for Japanese-language papers.

On the U.S. mainland miners' strikes were spreading across the mid-western states. Despite the intervention of AFL President Gompers, no settlement had been reached. On November 7 Attorney General Mitchell Palmer issued a strict warning to end the strike. Two days later, on November 9 at 7:00 P.M. , a lecture meeting on current issues was held under the sponsorship of the Plantation Labor Supporters' Association at the Asahi Theater in Honolulu. (The resident Japanese had met here to

discuss the Japanese-language schools problem the previous March.) The meeting was attended by a crowd of some one thousand Japanese, far greater than the number of seats in the theater. Many were forced to sit in the aisles.

The first to take the stage was Takeshi Haga, a nineteen-year-old youth from the Palama area youth association. Brought over to Hawaii from Yamanashi by his father two years earlier, he spoke about his experience working on Waipahu Plantation:

This is no time to put up with being treated like livestock. Merchants in Honolulu who sell the sugar plantation laborers rice and miso they import from Japan are making a big profit. At a difficult time like this, when our blood compatriots on the islands are sweating away at hard labor day after day under the scorching sun, we must as a body censure those who ignore their plight. I respectfully urge you to contribute all forms of aid, material and spiritual, to encourage the sugar plantation laborers.[3]

Haga spoke passionately, even referring to the Russian revolution. (In preparing for his speech, Haga had wondered whether he should speak in the style of Seigo[*] Nakano or Yukio Ozaki, two prominent orators of the day, and he had practiced repeatedly, like Demosthenes, projecting his voice over the crash of the waves on Ala Moana beach.

In 1919 many prominent Japanese stopped over in Honolulu on their way to the Paris Peace Conference. Although their ships were in port for less than a day, they were invited to speak at lecture meetings sponsored by the newspapers. It was a rare chance for the Japanese in Honolulu to listen directly to Japanese leaders from various circles, and often the speakers inflamed the audience's patriotism from the stage. For example, Seigo Nakano, editor-in-chief of Toho[*] jiron , declaimed that "a clash between Japan and America" over the future of Japanese interests in China would be "difficult to avoid." Calling the white man a villain and waving the rising sun flag were dangerous in a society dominated by Caucasians, but the Japanese audience greeted Nakano's speech with applause and cheers. The Japanese newspapers, reporting these events in florid language, made them the topic of the day at barber shops and public baths or at lunchtime in fields of the sugar plantations.

But many visitors urged prudence. Baron Shinpei Goto[*] , one of the country's most prominent officials, who stopped on his return trip from the Paris Peace Conference a week before the meeting on current issues, told his audience to tread softly on the Japanese-language schools problem and labor problem: "The fortunate Japanese here in Hawaii must

adopt the standards and ideals of the American nation. They must realize that they are part and parcel of the body politic of the United States and not of the body politic of Japan." The Honolulu Advertiser reported his speech on November 4, 1919, under the headline "'Become American' word of Goto to Japanese, Says 'English Education is best.'"

As the former head of civil administration in Taiwan, Goto[*] had promoted sugar production. Given this background, it is likely that he better understood the feelings of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association (HSPA)—those with the ruling power—than the feelings of the Japanese immigrants. His remarks were made at a welcoming reception held at former Governor Walter F. Frear's residence and attended by fifty prominent citizens of Hawaii. A skilled diplomat, in supporting the assimilation of immigrants, Goto was not speaking directly to the immigrants themselves but making a gesture to please his American hosts.

Several Japanese leaders had stopped in Hawaii on their way to the first International Labor Conference convened in Washington, D.C., in October and November 1919. As labor problems were troubling the whole world, President Wilson proposed a conference aimed at easing labor-management relations. Chaired by Samuel Gompers of the AFL, it was attended by representatives from forty-one countries who discussed the freedom to unionize, the minimum wage system, the eight-hour workday, and other issues making up the nine principles of the Labor Bill of Rights. The eight-hour workday, adopted five years before by the Ford Motor Company to shut out the IWW, had gradually taken hold in the United States, and nearly half the workers had secured this right. The government and industry representatives from Japan, opposing the eight-hour workday, pressed the other nations' representatives to give Japan "special treatment." Just before departing from Honolulu, Shinpei Goto explained, "Since the Japanese have long torsos and short legs in comparison to Caucasians who have short torsos and long legs, the Japanese tire more easily and are inferior in their working power. Shortening working hours to eight hours is suitable for the Caucasians, but we must look at the Japanese in light of their physiology. This is why under the current labor system in Japan hours are somewhat longer but include many breaks."[4] In the sugarcane fields of Hawaii, the ten-hour workday was normal.

Although many Japanese attended the November 9 meeting in Honolulu, the movement for wage increases on Oahu's sugar plantations did

not easily fall in step with the movement on the Big Island. The memory of the 1909 strike ten years before, when only the Japanese workers on Oahu had struck and then been miserably defeated, was a stumbling block. Finally, however, a branch of the Federation of Japanese Labor was organized on Waialua Plantation.

On December 1, 1919, under the sponsorship of the Honolulu Plantation Labor Supporters' Association, worker delegates met to organize the Japanese laborers on all the islands. The meeting, held in the Honolulu Club, whose entrance was decorated with Japanese and American flags, was attended by two delegates from each of the six major plantations on Oahu, eight delegates from Hawaii, three from Kauai, five from Maui, and thirty from the Honolulu Plantation Labor Supporters' Association.[5]

From the start there were disputes about voting rights. In fact, the night before the meeting began delegates from Hawaii, Maui, and Kauai had gathered at the Kyorakukan[*] restaurant on Nuuanu Avenue to hold a three-island council. Ostensibly it was a social gathering, but its real purpose was to discuss how to rein in the Honolulu Plantation Labor Supporters' Association, which tended to plunge ahead without consulting the laborers themselves. To be sure, without the supporters' association, the meeting in Honolulu would not have been funded or even held, but the laborers' delegates were extremely wary of the participation of all the Honolulu Japanese newspapers. At the November 9 meeting, for example, five of the nine speakers had been newspapermen. As the Hawaii hochi[*] asserted on December 1, the newspapermen believed that "making changes in society depends on the organs of public opinion." The newspapermen took the attitude that the workers could not do much without the "intelligentsia." And their attitude suggested that their involvement might reflect a struggle for leadership among the newspapers.

The English-language press saw the wage increase movement not as one arising from among the laborers but as an affair stirred up by the Japanese-language newspapers. The labor delegates feared that if the Japanese-language newspaper reporters led the attack at the meeting, it would only reinforce the views of the English papers and play into the hands of the planters' association. "This is our movement," they felt, "so we will carry it ourselves. We appreciate sympathy and understanding, but we reject any interference."

In the end, the question of voting rights was resolved by allocating

votes on the basis of the number of laborers, with eight votes going to Hawaii and six votes to each of the other islands. As this was a workers' struggle, the supporters' association had the right to speak out but did not participate in the votes. One newspaperman, disgruntled at this resolution of the voting rights issue, immediately challenged the qualifications of Noboru Tsutsumi, the delegate from Hawaii.

The Honolulu newspapermen found it difficult to deal with Tsutsumi, a man whose education was superior to their own. Tsutsumi had never made the round of greetings to the Japanese-language newspapers, considered customary for anyone seeking to do anything in Honolulu. It was Tsutsumi, moreover, who had warned against the involvement of the Japanese newspapermen in the wage increase movement and insisted that it should be a labor movement with "true laborers" as its members. Irritated that "peasants" had arrived in Honolulu to dominate the movement while they were forced to the sidelines, the newspapermen made Tsutsumi the object of their attack.

Tsutsumi had already resigned from the Hawaii mainichi , but there was certainly a problem with his qualifications as a "true laborer." Among delegates from the other islands were newspaper reporters or schoolteachers, but all of them had had experience working in the cane fields. Nevertheless, the labor delegates from the islands, brushing aside interruptions by the supporters' association, resolved, "It is not essential that those entrusted by laborers to be their delegates be laborers."

On the third day of the meeting, the delegate from Ewa on Oahu directly criticized Haga (nicknamed "Fighter Haga"), editor-in-chief of Hawaii hochi[*] , who had strenuously criticized the 1909 strike in a newspaper bought out by the planters. He continued to publish vehement views on the labor movement, incurring the anger of the Japanese laborers. The consulate in Honolulu still has in its archives a threatening letter, with a photograph of Haga showing in red ink blood flowing down from the tip of a Japanese sword stuck in his throat.

Despite such disputes the delegates finally managed to debate the main issue: how much of a wage increase to demand. On December 5 they issued a declaration announcing the formation of the Federation of Japanese Labor in Hawaii (also called the Japanese Labor Federation by English newspapers). President Manlapit of the Filipino Labor Union, who attended that day, stressed the importance of cooperation between the Japanese organization and the Filipino workers. In response, the Japanese promised solidarity. But when the Japanese delegates met that

evening to decide on the details of the wage increase agenda, the main topic was put aside as discussion shifted to warnings about the Filipinos until late into the night.

"Give Us $1.25 a Day"

At 10:00 A.M. on December 6, five Japanese labor representatives visited the office of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association and handed over a written wage increase demand to its executive secretary, Royal D. Mead. It read:

We are laborers working on the sugar plantations of Hawaii.

People know Hawaii as the Paradise of the Pacific and as a sugar producing country, but do they know that there are thousands of laborers who are suffering under the heat of the equatorial sun, in field and in factory, and who are weeping with ten hours of hard labor and with a scanty pay of 77 cents a day?

The statement included demands for an eight-hour workday as well as for contract changes for contract workers and tenant workers. But the most urgent demand was revision of the basic wage. "The wages of common man laborers, which at present are 77 cents per day, shall be increased to $1.25. . . . And minimum wages for woman laborers shall be fixed at 95 cents per day."

According to surveys undertaken by the Japanese workers, the minimum living expenses were about $34 per month for unmarried men and $75 for a family composed of a husband, a wife, and two children. This was an increase of more than 40 percent over what was needed four years before, and education expenses for the children were not included. Projecting needs into the future, Tsutsumi and other Hawaii Island delegates pressed for wages of $3 a day, but all the delegates from the other islands insisted that the wage increase should be an amount acceptable to the planters. In the end, the delegates agreed on a demand for a minimum wage of $1.25 a day.

Compared to the demands for wage increases on the American mainland, this was not a great deal. Seattle longshoremen were demanding $5.25 per day for unskilled laborers; San Francisco stevedores, $8.80 per day. The 1915 Report on the Survey of Labor in Hawaii concluded that "the laborers in Hawaii earn low wages in comparison to laborers in California; and there is little opportunity for future advances."

Though they were provided with housing, the wages of the Hawaiian laborers were shockingly low.

The $1.25 a day demand took into consideration the bonus system. It was only with bonuses that plantation workers were able to eke out a living. Under a formula that said laborers should benefit from profits, the bonus rate was calculated according to the current market value of sugar. To receive a bonus, a laborer had to work twenty days or more per month. Plantation owners, who regarded the bonus as a way "to encourage diligent work and savings," used it as a worker incentive. The bonus system had the effect of discouraging workers from changing jobs or moving to another plantation. It also encouraged workers to continue on the job even when they were injured by the knives used as tools or by sharp cane leaves, or when they became ill from working under the scorching sun. To qualify for a bonus, sick or injured workers forced themselves to go out to the fields.

Tsutsumi and the Hawaii delegates thought that the bonus system should be abolished, the paternalism of the company side should abandoned, and the laborers should insist on $3 a day as a fair basic wage. What delegates from all the islands agreed on, however, was a demand for $1.25 a day and for a decrease in the number of workdays needed to qualify for bonus pay to fifteen days per month (or ten days for women).

At its 1919 annual meeting on December 8, the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association discussed the wage increase demand from the Federation of Japanese Labor. The HSPA was formed in 1883, fourteen years before the American annexation of Hawaii. Its membership included forty-four Hawaiian sugar companies, but the real power within the association was held by a handful of kamaaina, large plantation owners who controlled all phases of the industry—harbor facilities, railroads, buses, major banks, insurance companies, electricity, and fuel. Indeed, these sugar magnates held the actual power in the territory, and they were a formidable opponent for the cane field laborers to challenge.

It is clear from the minutes of the 1919 annual meeting that the planters knew living costs and prices had increased and that they tacitly recognized the need for a wage increase. Nevertheless, at noon on December 11, the final day of the annual meeting, John Waterhouse, president of the HSPA, firmly rejected the wage increase demand the Japanese and Filipino laborers had made. (The formal reply to the laborers' union was dated December 16.)

Arguing that housing, lighting, and fuel costs were borne by the companies and that the bonus system would be revised, the HSPA refused to budge from a basic wage of 77 cents per day. They proposed to revise the bonus system by changing the base from the annual price of sugar to its monthly average price. Since an increase in sugar prices was forecast, the HSPA said that this was the maximum concession it could make. The annual meeting also decided to establish a bureau for handling housing facilities, sanitation, and social welfare of workers. "Besides sound business reasons," they announced, "there is an ethical obligation, that we properly care for those whom we have brought here, and the further obligation that their standard of living and social conditions be such that their descendents will be qualified to become useful American citizens."[6] In other words, the HSPA absolutely refused to recognize collective bargaining with a labor union, no matter what was going on on the American mainland or in the world. As in the past, the planters attempted to deal with the workers in a paternalistic manner.

On December 14 the Filipino Labor Union, which had submitted similar wage demands, held a delegates' meeting that voted unanimously to strike. The union also sent a telegram to AFL president Gompers—"Deliberating strike. Hope for your utmost support"—and it also sought support from the headquarters of the Manila labor organization.[7]

On the plantations rumors spread that the strike might start in a week, but the Japanese federation, thinking that the first stage in the negotiations had just started, hesitated to support the Filipinos' decision to strike. From the start the Japanese labor delegates from all the islands agreed on the principle of cooperation between labor and management, and they held out hope for a lawful settlement based on "temperate discussion."

The Federation of Japanese Labor had just opened an office on the second floor of the Sumitomo Bank at the corner of Smith and King streets in the downtown area near Aala Park. Tsutsumi had returned to Hilo to straighten out his own affairs, but when he received a telegram about the Filipino decision to strike, he rushed back to Honolulu. So did the delegates from the other islands. Since the office was still bare of tables and chairs, the delegates had to discuss their plans while standing. The first order of business was to request a loan of $500 from the Japanese-owned Pacific Bank.

The man who had found the office was Ichiji Goto[*] , a native of Kumamoto prefecture. Goto was the same age as Tsutsumi, but he had worked

on a sugar plantation after his father brought him to Hawaii when he was fifteen years old. He attended an English-language night school in Honolulu while working as a house boy, and he became a fervent Christian as well as a member of the youth association of Nuuanu Church. After a stint as a reporter for the Maui shinbun , he became a reporter for the Nippu jiji , one of the leading Japanese newspapers in Honolulu. Goto[*] resigned from his job and became secretary of the federation headquarters when it opened its new office. Short in stature, with the round rugged face of a farm boy, Goto made a favorable impression on everyone. He was usually a man of few words, but at the meeting on current issues held the previous month he had attracted attention with his denunciation of the "tyranny of the plantation owners who regard laborers as beasts of burden."

To fight against the unyielding HSPA, the federation's most urgent task was pulling together a strong organization. The worker delegates asked Seishi Masuda, principal of the Kakaako Japanese-language school and a man regarded as an upstanding figure in the Japanese community, to become secretary-general of the federation. According to the FBI files, "Masuda is deeply interested in labor questions and in the past wrote several articles concerning labor questions in the local Japanese newspaper. Masuda was quite willing to accept the position [of secretary-general of the federation]. However, his fellow teachers advised him to keep away from labor agitation as it will arouse misunderstanding."[8] Despite his colleague's misgivings, Masuda agreed to take the job. On December 21 sixteen directors selected from the islands attended the first directors meeting. Tsutsumi proposed a temporary headquarters organization consisting of an administrative committee (to co-ordinate communication with the labor organizations on each island), a negotiating committee (to negotiate with entities outside the federation), and a finance committee (to handle accounting matters). Together with secretary Goto, Noboru Tsutsumi and Hiroshi Miyazawa, both from Hawaii, were appointed to the secretariat as superintending secretaries.

While the federation was engaged in this flurry of activity, the shopping district of Honolulu was being draped in red and green Christmas decorations. Christmas Eve in Honolulu was celebrated with a paper blizzard instead of snow. On the main street a lively parade of immigrants from various countries marched in their native costumes, and American troops posted from the mainland participated as well. On Christmas Day the English-language newspapers carried a full-page announcement on the front page, "Joy and Peace to All Hawaii upon this

Christmas Day," as well as prayers for peace in the coming year. After all, the Hawaiian Islands had been developed by missionaries.

On December 26 the Federation of Japanese Labor submitted its second wage increase demand to the HSPA. At the same time the federation leaders called for "unity, resolution, frugality" by the laborers. It also warned against acting like okintamamen , a word said to be derived from a term referring to sumo wrestlers who curried favor with higher-ranking wrestlers by washing their private parts. In this case, it meant those in collusion with the planters.

At year's end a theatrical troupe from Japan toured the islands, with a beautiful magician blowing kisses to the crowds. It was the talk of the Japanese community. The festive New Year's mood was dampened by news of a severe influenza epidemic, but on New Year's Eve the haole social elite, decked out in expensive evening gowns and tuxedos ordered from San Francisco and New York, danced out of the hotel ballrooms into the streets to the rhythms of the bands, showered at the stroke of midnight by blizzards of confetti.

On the second floor of the Sumitomo Bank, oblivious to the New Year's festivities, the Federation of Japanese Labor continued its heated debates. Noboru Tsutsumi, who was staying in the Kobayashi Inn across from Aala Park with the other delegates from Hawaii, was hard at work at federation headquarters from 7:00 A.M. until late into the night preparing for negotiations with the HSPA in the new year. He had resolved to forgo New Year's celebrations.

Meanwhile on the day before New Year's, the territorial governor, Charles McCarthy, together with several legislators, had departed Honolulu by ship to deliver a petition to Washington. Although this trip was to have significant repercussions later, the federation leaders paid no attention to their departure.

The Palmer Raids

On January 3, 1920, the Honolulu Advertiser carried the following article:

Arrest 5,000 to thwart plot against U.S.—Washington, Jan. 3—(AP). Agents of the Department of Justice and police officials had arrested 3,896 radicals at midnight in raids on headquarters of the Communist Labor parties in 70 cities throughout the United States in an effort to upset a plot for the establishment of an American soviet government. At that hour it was believed that fully 5,000 disciples of radicalism would be behind bars by daylight.

These so-called Palmer Raids, reported on front pages all over the country, continued under the direction of U.S. Attorney General Palmer for several months. They led to the arrests of some ten thousand men and women in seventy cities throughout the United States. The purpose of the raids was to deport foreign radicals. The American Communist party, formed the previous September, was targeted along with socialists, anarchists, and labor unions such as the IWW. In actuality, the raids were a general roundup of "Reds." The American press, starting with the New York Times , approved of the prompt handling of the red scare and reported that the danger of a government overthrow had been narrowly averted. Most historians now consider the Palmer Raids a violation of the civil rights of innocent persons unprecedented in American history.

The origin of the Palmer Raids lay in the discovery of thirty-eight bomb packages mailed to prominent Americans, including financier J.P. Morgan and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, just before May Day in 1919. Claiming this was to be the start of an attempted revolution, the FBI spread fears of political subversion. Nothing happened on May Day, but after the commotion had died down, on June 2 a bomb exploded in front of Attorney General Palmer's house. That night there were explosions near the homes of several judges, one of which killed a night watchman. Dynamite blasts occurred in front of immigration offices and churches as well.

President Wilson, who was campaigning for the League of Nations, was facing strong domestic opposition from the Republican party. During a speaking tour to win public support for his plan, Wilson collapsed from a stroke. Hiding news of his paralysis from the nation, his aides and his wife, a political novice, took over the affairs of state. It was after this that the Palmer Raids began at the attorney general's initiative. Nineteen twenty was a presidential election year. Palmer's name had been raised as a possible Democratic candidate to succeed the incapacitated Wilson, and the raid raised his political profile. The raids were also an opportunity for Palmer's right-hand man, J. Edgar Hoover, to sniff out "radical red elements" and anarchist assassination plots and to increase his political influence by "ridding America of the red menace." Although the majority of those arrested in the Palmer Raids were associated with the Communist party, the real purpose of the raids was the arrest of anti-American activists whom Hoover and his subordinates judged to be politically dangerous. In the background were the long-lasting miners and steel workers strikes, which involved four hundred

thousand workers and were led by former IWW organizers. Six days after the Palmer Raids began, the strike was called off.

At the time of the Palmer Raids Hawaii was not yet under Hoover's jurisdiction. Even so, the two major English-language newspapers in Honolulu, the Honolulu Advertiser and the Honolulu Star Bulletin , explained to their readers how to protect Hawaii from the dark shadow of Bolsheviks and IWW radicals. Both newspapers served as mouthpieces for the HSPA, but they had not yet connected their antiradical arguments to the Federation of Japanese Labor. It was obvious to the HSPA that the demand for wage increases by the federation did not involve either ideology or the IWW.

The Japanese in Hawaii had little understanding of the impact of the Palmer Raids. Teisuke Terasaki, a reporter for Hawaii hochi[*] , who had made a habit of writing daily entries in his diary noting memorable events in a concise, unemotional manner, is a valuable source on daily life in Hawaii at the time. But Terasaki's diary does not contain a single sentence about the Palmer Raids on the mainland. Instead the entry for January 2 reads, "Delegates to the labor convention enter port on the Siberia-maru. Talks at the young men's association by Sanji Muto[*] (industry representative) and Eikichi Kamada (government representative)."

These two men were part of a twenty-five-member Japanese labor delegation on their way home from the International Labor Conference held in Washington, D.C., two months earlier. The Japanese delegates had incurred criticism from the European and American delegates by petitioning that Japan be given special treatment on labor issues. After attending a luncheon meeting on January 2, they were on their way to Yokohama in the afternoon. A report on the International Labor Conference by the U.S. Department of the Interior called the meeting a failure, saying it had widened the gap between capitalists and laborers.

On Sunday, January 4, the Federation of Japanese Labor sponsored a mass meeting at the Asahi Theater in Honolulu to report on the conditions of plantation workers. The last speaker, Noboru Tsutsumi, described the basic stance of the federation headquarters. "The capitalists cannot treat laborers as machines, " he said. "As long as they think laborers are satisfied with getting just enough food to keep from starving and receiving a bonus as if they were machines being oiled, they have not

recognized laborers as people. Desiring improvements in production, we are prudently stressing harmony between management and labor. However, if the capitalists are determined to destroy production and oppress laborers, it is inevitable that we strike."[9]

After the meeting, the federation planned to collect "righteous contributions" from the general public to support the strike. The very next day, however, the Oahu branch called for the provisional dissolution of the temporary federation headquarters and the halt of the money-raising campaign. The Oahu labor leaders were worried about the existence of an "advisory committee" for the federation headquarters, made up of newspapermen who were also the principal members of the strike supporters' association. From the start neither Tsutsumi nor the other leaders in the federation headquarters had been able to control the advisory committee, whose members vented their conflicting opinions as they pleased in the competitive spirit of newspapermen. Any action by the federation headquarters also needed to be approved by the advisory committee.

Since withdrawal of the Oahu workers would mean a halt to any concerted labor actions, the federation headquarters now had an excuse to disband the advisory committee. Ichiji Goto[*] , who was involved as a reporter selected by the supporters' association, played the central role in the negotiations, and on January 7 all the members of the committee resigned. The federation secretary, Seishi Masuda, who had lost trust by being too deferential to the advisory committee, also stepped down. It was after this turn of events that the Hawaii hochi[*] began to attack the ineffectiveness of the federation headquarters. The Honolulu branch offices of the Yokohama Specie Bank and the Pacific Bank, founded by the leading Japanese merchants with support from Eiichi Shibusawa and other Japanese industrialists, also refused to lend money to the federation. The capitalist plantation owners were not their only enemies.

On January 14, the day the United States demanded the withdrawal of Japanese troops from Siberia, the HSPA notified the Federation of Japanese Labor headquarters that it rejected any further negotiations. That night the federation directors gathered at the Kyorakukan[*] restaurant to discuss whether to strike. The Kyorakukan was located at the corner of Nuuanu Avenue and School Street, about twenty minutes by streetcar from the federation headquarters. In the garden behind the main restaurant building was a detached cottage, ideally suited for clandestine

meetings. It had a Japanese-style bath, and guests could spend the night there.

Heated discussion lasted late into the night, but by 3:00 A.M. the directors pledged to one another that when the time came, they would stake their lives on the strike. As Noboru Tsutsumi later noted, it was the first time that the directors from the various islands had made a unified decision. But the federation leaders thought that there was still room for negotiation. The Filipino Labor Union had announced that it would strike in two days, but with a serious influenza epidemic spreading through the community, the federation leaders wanted to proceed with caution. They feared being dragged along by the hasty actions of the Filipinos. Hiroshi Miyazawa, whose English was fluent, was in charge of close liaison with the Filipinos. He worked hard to rein them in. At the same time, the directors of the federation directors, making preparations just in case a strike took place, went on "observation trips" to the islands.

Terasaki's diary entry for January 16 noted in English, "Hochi[*] begin attack upon staff labor Union because they do nothing for labor but themselves." The Hawaii hochi[*] had reported that day, "The headquarters directors are busily seeking contributions, taking compensation of $6 per day from the amounts donated." This was a false report intended to damage the federation directors, but it forced a temporary halt to the fund-raising campaign on Oahu, and the federation was forced to print an open letter in the Hawaii hochi to dispel suspicions.

On January 17 a document signed by Goto[*] requesting reconsideration by the HSPA was sent. Meanwhile Hiroshi Miyazawa was at the Filipinos' headquarters on the second floor of a Japanese wholesalers' shop about three blocks from the federation headquarters, trying to persuade Manlapit to postpone the strike. The thirty-two-year-old Miyazawa was the second son of a farming family in Nagano prefecture who had come to Hawaii when he heard that he could work his way through school. As a "school boy" working during the day, he studied English and Episcopalian theology at night school. On a tour of the plantations to do missionary work, Miyazawa was hired by a labor contractor as an interpreter, and he thus became thoroughly familiar with the living and working conditions of the plantation laborers. Since Miyazawa had worked with Tsutsumi in organizing the Federation of Japanese Labor, the FBI file dated August 2, 1921, noted, "Miyazawa has become more or less radical in his views through influence of Tsutsumi."

"We're Not Working":

The Strike Begins

Although the Filipinos had issued a strike statement, they had not made any strike preparations. They did not even have a fund to cover food expenses for striking laborers. Since no Filipinos in the islands were successful enough to give financial help to the strikers, they sought aid from the Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu, which rebuffed them. On the evening of January 17 Manlapit issued an order to postpone the strike planned for January 19, stating that he had failed to get assurances of cooperation from the Federation of Japanese Labor of Hawaii. But on January 19 Terasaki noted in his diary, "Filipinos at Ewa, Waipahu, Aiea, Kahuku start their strike. At Ewa Portuguese and Puerto Ricans join in. There may be a total of 3,000 people." Why did the strike start even though it was to have been postponed?

It began when a Hawaiian luna sneered at Filipino laborers at Kahuku Plantation, "No can strike, you, Filipino, hila hila [cowards]." At the close of work on January 18, the agitated workers gathered at the Filipino camp at Kahuku Plantation. Ignoring Manlapit's order, at 6:00 P.M. they made an independent announcement that they were on strike. This action spread immediately to other plantations on Oahu, and all the Filipino laborers left the cane fields the following morning.

Ironically, the Filipino workers had been brought in great numbers to Hawaii as strikebreakers during the first Oahu strike in 1909. They had arrived in Hawaii to control Japanese laborers who were "dangerous and didn't know their place." At the time, the HSPA noted, "The outcome of this strike movement, while calling for great expense to the Planters' Association and the territory, has the promise of proving a blessing in disguise. Too long have the vested interests of the territory permitted the dominating nationality to insidiously dispossess others in the varied lines of higher grade work."[10] Ten years later, however, the Filipinos, now the second-largest labor force after the Japanese, were ready to take on the HSPA with all its power.

Most Filipino laborers were single. About 40 percent had wives and families, whom they had left in the Philippines. Although many looked forward to being reunited with their families, statistics show that only 48 percent actually returned to their homeland. Under these circumstances cockfights and "three-minute dances" were their only fleeting pleasures. They eagerly looked forward to the arrival in camp of dance troupes from the Philippines. For the price of a ticket they could dance

the tango, pressing their bodies against the dancers for three minutes. Some Filipino workers were also said to engage in homosexual activities, and for that reason Japanese immigrants held them in contempt. At festivals and celebrations Filipino workers sometimes danced with each other to the beat of the rumba whose intense rhythm blended the native music of Cuba with the music of the African slaves taken to work in Cuban sugarcane fields.

The example of the Filipino strike that began on January 19 stirred the Japanese laborers but they were slow to take action.

"Japanese cane workers threaten general strike" ran the lead headline in the January 20 Honolulu Advertiser . From the start of the strike the English-language press focused attention on the Japanese. Indeed, they treated the strike by the Filipinos as though it had been instigated by the Japanese. In fact, the Federation of Japanese Labor had announced that if the Filipinos went on strike, "Our position and intentions are wholly legal and orderly. If a strike of Japanese labor shall be called, [the laborers are] cautioned to quit their places in a quiet and peaceable manner." The Japanese plantation workers in Oahu were equally cautious. Flatly refusing to follow the Filipinos, whom they looked down on, they chose to work in the fields even though the Filipinos were on strike.

"Pau hana, no go work "

The Filipino laborers, who had never doubted that the Japanese would stand with them, were enraged. At Waipahu Plantation several dozen Filipinos attacked Japanese workers boarding a train to go to the cane fields on the morning of January 21. The anger of the Filipino workers was so intense that the Filipino Labor Union was hard-pressed to calm them down. The Japanese workers, fearing that the Filipinos were ready to pull out knives at any provocation, returned to their camp houses with their lunch boxes in hand. At Ewa Plantation, six kilometers west of Waipahu, Filipino workers wielding scythes and knives swarmed around a train traveling through the cane fields. The Japanese engineer and the Hawaiian plantation guard fled into the field of tall sugarcane and hid there until the sun went down. A similar incident occurred at Aiea Plantation near Pearl City between Honolulu and Waipahu. Special officers from the Honolulu police force were rushed to these plantations to arrest numerous Filipinos.

Hiroshi Miyazawa, the federation's man in charge of relations with the Filipinos, went to the large Waipahu Plantation for a workers' rally

at noon the same day. Fearing that harm might come to their families, many Japanese workers concluded that things had come to such a pass that they had no choice but to back the Filipinos and to stop work. Noboru Tsutsumi, who had returned from a trip to Maui, and the other directors, who had returned from observation trips to the other islands, met immediately. After hearing reports from the four islands, they decided to issue a work lay-off order to all the plantations on Oahu—Ewa, Aieia, Waialua, Waipahu, Kahuku, Waianae, and Waimanalo.

Even at this stage, the federation's work lay-off order was considered to be quite different from a strike order. Continuing to negotiate with the planters, the federation sent Goto[*] and Miyazawa to the HSPA to give Mead, the HSPA's secretary, a third written demand for wage increases. The two men also requested that they be allowed to attend the regular meeting of the HSPA to explain the laborers' position. Mead turned them down. It was "no use," he said.

The federation's first delegates' meeting, composed of representatives from plantations from all the Hawaiian Islands, was held on January 25 at the Palama Japanese-language school. At about 4:00 P.M. it went into a secret session closed to outsiders under tight security, guarded by directors carrying pistols. At 10:00 A.M. on the morning of January 26 the Federation of Japanese Labor in Hawaii resolved unanimously to "carry out a walkout by the Federation as of February 1" if there was no change in the attitude of the HSPA.

Secretary Noboru Tsutsumi, as representative of the participants, read aloud the resolution. After waiting for the applause to die down, he explained the organization of federation headquarters. He said that the three secretaries, Tsutsumi, Miyazawa, and Goto, would remain in their positions as agreed upon when the federation was established. The meeting also reconfirmed that the strike would be held only on the island of Oahu, with workers on the outer islands raising support funds. They also needed to be prepared to assist in covering the strike expenses of the Filipinos.

On the following day, January 27, the HSPA gave its final response. The planters' association said that it did not recognize the laborers' union or its right to collective bargaining and that it would not respond to "any demands." In response, the usually moderate Nippu jiji printed a large headline, "110,000 comrades, carry out collective duty; we have an obligation to support the laborers who stand on the front lines so that they may be free of anxieties." The Hawaii hochi[*] also showed its

support of the federation's strike resolution in an editorial with the title "A Courageous Struggle."

On January 30, at a noontime rally at Waipahu, the three federation secretaries were in attendance. In response to Miyazawa's speech in English to the Filipinos, Manlapit appealed for unity between the Japanese and the Filipinos. Goto[*] then explained the procedures and cautions to be followed by federation members. Speaking last, Tsutsumi urged the workers on, "We'd like you to settle in and treat this as a five to six month vacation and hang on until your promised wages are paid."[11] To a man, the laborers in their denim overalls rose with a long and vigorous round of applause. Noboru Tsutsumi had become the indispensable man at rallies on every plantation.

At 2:00 P.M. on January 31 an official strike declaration for "realization of wage increase demands" was issued for the plantations on Oahu island. Beginning on the morning of February 1, Japanese and Filipino laborers, who together made up 77 percent of the plantation workforce on Oahu, boycotted the cane fields.

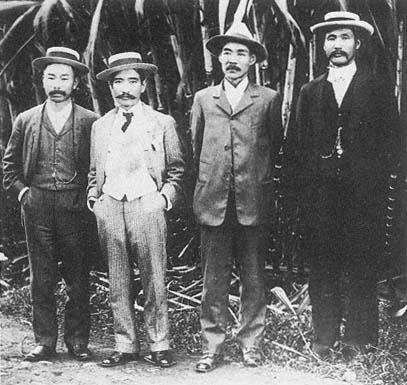

Figure 1

Juzaburo[*] Sakamaki (second from left); Jirokichi Iwasaki (fourth from left).

(Courtesy of Bishop Museum)

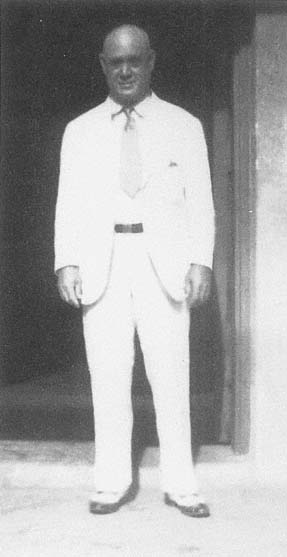

Figure 2

"Fred" Kinzaburo[*] Makino.

(Courtesy of Hawaii hochi[*] sha)

Figure 3

Noboru Tsutsumi.

(Courtesy of Tsutsumi family)

Figure 4

Leaders of the Federation of Japanese Labor. First row: Ichiji Goto[*] (second from left),

Tokuji Baba (third from left), Honji Fujitani (fourth from left), Chuhei[*] Hoshino (sixth from left);

third row: Yasuyuki Mizutari (first on left); fourth row: Shoshichiro[*] Furusho[*] (first on left),

Noburo Tsutsumi (second from left), Hiroshi Miyazawa (fourth from left).

(From Tsutsumi, 1920 Hawaii sato[*] kochi[*] rodo[*] undoshi[*] )

Figure 5

Posters distributed by the Hawaiian planters during the 1920

strike: (top) Filipino strike leader leaving Hawaii with a sack of money;

(middle) striking Japanese worker receiving a pittance from "agitators"

versus worker on the job receiving regular wages; (bottom) cigar-smoking

Federation of Japanese Labor leaders riding in a rented touring car.

(From Tsutsumi, 1920 Hawaii sato[*] kochi[*] rodo[*] undoshi[*] )

Figure 6

Guilty verdict in the Sakamaki dynamiting trial.

(In author's possession)