Reading Kane

Leonard J. Leff

All this happened in much less time than it takes to tell, since I am trying to interpret for you into slow speech the instantaneous effect of visual impressions.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

Vol. 39, no. 1 (Fall 1985): 10–21.

Charles Foster Kane's second wife has left him. In mute frustration, he throws down her suitcases and begins wrecking her overdecorated bedroom. When he comes to a glass paperweight, he stops. He shakes it and says, offscreen, "Rosebud." With his butler and other servants watching silently, he walks into one corridor, then another, out of his employees' range of vision, until he passes between two full-length mirrors. This last image of Charles Foster Kane is multiplied again and again into infinity, a powerful envoi to Citizen Kane 's visualization of its main character.

After Kane walks offscreen, emptying the frame of people, the camera slowly advances toward the mirror. The mirror cannot reflect Kane's servants, for they have been left behind in an adjacent corridor; but since it is a mirror and has reflected Kane's image, it must reflect something. As the camera continues its forward progress, it promises to expose—what? Raymond, the flashback's putative author? The narrator? The camera? The spectator? Here we directly confront two questions: Who is the arranger of the images? And who is watching the film? In the following essay, I wish to explore the reasons that previous answers to these questions have seemed somehow unsatisfying; I would also like to suggest a method of reading Citizen Kane that will allow us to understand our reactions to the film even if it does not permit us to speak conclusively of the "meaning" of the film and its surprisingly inconstant point of view.

Although critics Bruce Kawin, Nick Browne, Seymour Chatman, Brian Henderson, and others have at length discussed point of view as well as the relationship between point of view and the spectator, Kawin has focused specifically on Citizen Kane . (See the "Works Cited" at the conclusion of this essay.) Kane portrays its narrators in the third person, Kawin says in Mindscreen: Bergman, Godard, and First-Person Film , but accords their narratives a first-person bias. In Thatcher's story, for example, the banker's "narrating mind is offscreen. The film presents not Kane's life with Thatcher in third-person flashback

but Thatcher's tale (which is presumed to be both biased and accurate) in mindscreen" (34); consequently, we understand Thatcher's intent through his deployment of camera position, montage, etc., and recognize through "the logic of their changes" his narrative bias (14).

But are Kane 's narrators capable of generating the film's often sophisticated mise-en-scène ? In his interview with the News on the March reporter, the butler reveals an inarticulateness (Kane "did crazy things sometimes"), a limited vocabulary, a tendency to repeat himself, and a condescension toward his employer that make him, at best, a doubtful author of the "infinity of Kanes" image and its provocative coda. Thatcher's flashback presents similar problems. Through studied compositions that use deep focus, forceful images outside the banker's ken, and shots or sounds obviously from another character-narrator's sensibility, Thatcher's flashback posits the voices of other characters as well as that of a "supra-narrator," an awkward but necessary term in discussing Citizen Kane 's layered text. At some point in each of the flashbacks, not only does each narrator relate events at which he or she was not present, each also employs a visual and narrative style wholly at odds with his or her personality or state of mind. What these shifts in point of view mean , however, may ultimately matter less than what they do . To demonstrate, I turn to a stimulating if controversial methodology articulated by literary critic Stanley Fish.

For Fish, author of Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (1980), a text does not contain meaning, a reader produces it. Books are thus objects that readers translate into events . Consider the final line in Milton's "On His Blindness": "They also serve who only stand and wait." How far, we wish to know, has the speaker moved from an earlier impatience with God? To some Milton scholars, this line constitutes a profound trust in God; to others, a qualified, perhaps even forced note of affirmation. According to Fish, however, no conclusions are possible. Reading "On His Blindness" line by line, we execute a series of assumptions about the speaker and his relationship with God, each of which is undercut and no one of which is determinant. In short, the reader's experience of the uncertainty of the sonnet's last line constitutes the poem's very meaning. The parallels between literature and film are at once implicit and attractive.

Answering their detractors, reader-response critics like Fish have carefully defined "the reader." In the examination of Citizen Kane that follows, I have stipulated a composite "we" modelled after Michael Riffaterre's reader of "Les Chats," an informed "we" alert to what one of the cinema's most stimulating works does . Just as the News on the March reporter negotiates the post-Kane world, we negotiate Kane; we engage in a series of anticipations, reversals, revisions, and recoveries that forces us to examine the cognitive tasks that we as readers perform and that finally urges us to assume our role in the

work's creation. The reporter opens his investigation into the mystery of Rosebud by reading a manuscript whose "objectness" is exaggerated during its presentation. He expects the diary to "make sense," but it does not: readers make sense, not texts. Accordingly, as we make our way through a "slowed down" version of a Kane flashback, we may evaluate each shift in point of view as it occurs and thereby not extract a meaning from the sequence but, instead, locate the moments that frustrate assumptions or expectations about point of view, describe our experience of those moments, and discover in them how if not what Citizen Kane means.

"She won't talk," Thompson tells his boss after his first visit to Susan Alexander Kane. Thompson's search (really Rawlston's search, for Thompson resists going) takes the reporter from the El Rancho nightclub and its torpid singer to the Thatcher Memorial Library and the marble statue of its benefactor, Walter Parks Thatcher; thus the image of a woman who will not communicate fades to the image of a man who cannot communicate. Neither augurs well for solving the mystery of Rosebud. A litany of restrictions on hours, page numbers, and quoted matter precedes Thompson's entrance through a door that closes in our face. We read this last action as prohibiting our entrance. Almost at once, though, the image of the door dissolves to that of the library's inner sanctum. Outside Hollywood, to dissolve means to disintegrate, disunite, break up; the film's dissolve here does indeed separate us from our expectation of denied admittance, but it does not alter the experience of denied admittance. Citizen Kane continually draws us on. Will we come to know Kane or will we not? Will the film "let us in" or will it not? This and countless other moments in Citizen Kane , including the revelation of the flaming sled, suspend the answer, at last indefinitely. But even if we decide that we know something of Kane (or Rosebud or the little glass snow scene), the impediments to that knowledge remain part of our reading experience. In the conclusion of the essay, the implications of this point will be examined.

Aside from a portrait of Thatcher, the reading room qua vault houses the library's meager collection—one book, a "private diary." The setting's rigidity, formality, and containment suggest that even if Thatcher knew the secret of Rosebud, he might not divulge it. Nevertheless, the guard extracts the manuscript from the wall safe and, accompanied by a deathly cadence, bears it to Thompson. The library's pretensions are borne out in the halation of the diary, which along with the dramatic ritual of the receptionist and the guard may amuse us. Yet the presentation of the diary mirrors in reverse the door shut in our face; where the door frustrated our expectation of intimate knowledge of Kane, the diary promises it. "Thompson bends over to read the manuscript," states the shooting script. "Camera moves down over his shoulder onto page

of manuscript" (168). Thompson, his face never seen, remains in shadow throughout the film; at once there and not there, he approaches the embodiment of what the Germans call the "fiktiver Leser"—the "fictive reader." In going "over his shoulder" to reach the narrative agency, a script direction that the film heeds and replicates with each succeeding internal narrator, camera movement denotes a text reached through Thompson and explicitly read by him. We are to identify not with Thompson but with his task, reading.

We begin our reading, literally, with the section of the Thatcher manuscript entitled "Charles Foster Kane." Thompson quickly scans a prefatory note that we hardly see, much less read. (From its text, which can be read when the film is run frame by frame, one understands at once that Thatcher's diary is really a memoir, a recollection of events written well after the date of their occurrence.) Then, at a slower speed, the camera sweeps across a page, directing us to read, "I first encountered Mr. Kane in 1871." Despite the third-person title, "Charles Foster Kane," the narrative has opened in the first person. "I," stirring a nascent assumption about tellers telling their own tales, suggests that the story will center on Thatcher, rather than "Charles Foster Kane," not a hopeful sign for a reporter or a viewer in search of an intimate view of Kane. From the news short, we know that young Charles Kane assaulted Thatcher upon their first meeting; the banker's use of "encountered" connotes also the immediate adversial relationship between the two. "Mr. Kane," referring to Charles when he was a boy, reinforces "encountered" as a lexical gesture of contempt. In short, by the time the shot of the sentence begins to dissolve, we have reached an assumption about the forthcoming image, conventionally the opening of a flashback. "I," "encountered," and "Mr. Kane" have established the emotional distance and dissonance between the writer and his fractious subject. Along with the author's personality as indicated by the surroundings and the news short, the diction promises us a ponderous, self-serving narrative, wholly without sympathy for young Kane and dominated by Thatcher's jaundiced perspective.

The opening of the Thatcher section, focusing on the young Charles Kane playing in the snow, has a distinct point of view. But whose is it? Bruce Kawin argues that each of the film's narrators maintains his equivalent of "first-person discourse"; without distortion, "Thatcher's mind dominates those portions of the film that relate his part of Kane's story" (34–35). Our moment-to-moment experience of the sequence, though, suggests a disquiet overlooked in Kawin's interpretation. In The Magic World of Orson Welles , James Naremore sees what happens: "At first the black dot, against pure white [Charles against the snow] echoes the manuscript we have been looking at, but it swoops across the screen counter to the direction the camera has been moving, in conflict with the stiff, prissy, banker's handwriting, suggesting the conflict between Kane and Thatcher

that runs through the early parts of the movie" (41). During the dissolve from the library to Colorado, we experience a shift in expression, if not also perspective. The lighting, the music, and the very content of the opening shot argue against Thatcher's authorship. Music keyed to the gloom of the banker and his memorial, for example, lightens at Charles's appearance. A crisp three-note refrain, delicately percussive, becomes a satiny theme played legato on the strings; along with a glissando on the harp, it introduces not "Mr. Kane" but a carefree child, at one (Ira Jaffe says in "Film as the Narration of Space") with the natural universe (103). Charles's initial depiction and especially the romantic music accompanying it void our assumption that "Thatcher's mind" exercises sovereignty over his narrative.

As the spirited young boy continues playing his Civil War game, the camera draws back to reveal, sequentially, Charles's mother, future guardian, and father standing at the Kanes' window, through which we and—we now discover—they have been looking. The framing of the youth, walling him at once in and out, has been variously interpreted; Jaffe, for example, suggests that the camera's movement fixes Charles and renders "his physical existence suddenly . . . exceedingly fragile" (104). But what do the appearance of additional characters in the scene and the camera movement that effects it do ? At first, especially as we reflect on the contrasts in music and lighting on either side of the dissolve, we perceive the scene as narrated not by Thatcher but by a supranarrator. The moving camera's introduction of Mrs. Kane, however, causes us to revise: all along, apparently, the image of the happy child has been from his mother's perceptual point of view, one that seemingly unites the perspective and the expression. Or has it? The continued reverse tracking of the camera soon adds Thatcher to the frame. Like the weak-willed Jim Kane, he looks at Mrs. Kane, not Charles. Though she may dominate Charles ("Be careful, Charles. . . . Pull your muffler around your neck, Charles"), Thatcher dominates her. His mindscreen manifests itself not only in the room's gloomy atmosphere (which we gradually see) but in his direction of the scene's focus away from matters of the heart and toward the affairs of business: "Mrs. Kane," he says, "I think we'll have to tell him now." Mary Kane accedes. In the course of sixty seconds, the film has offered us three different points of view—a narrator's, Mary Kane's, and Thatcher's. Although we are back where we began, those moments when our assumptions about the narrative proved premature, if not false, remain part of our experience of Citizen Kane .

As Mrs. Kane turns from the window, she faces Thatcher, their profiles opposite one another in the frame. "I'll sign those papers now, Mr. Thatcher," she says, and begins to walk forward. Her fixed expression, a triumph of determination over emotion, seems to drive the camera down a path that she has willed it to travel. But when the camera comes to rest, we recognize that its

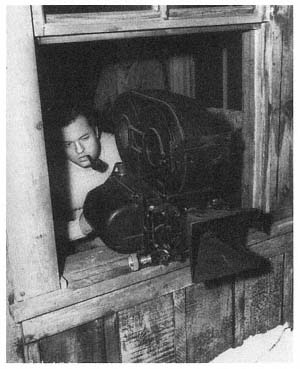

Welles shooting the first Thatcher scene

movement from the window has been constant and that it has led unfailingly toward the papers, Thatcher's papers, awaiting their signature. Thatcher concentrates on financial decisions, Kawin says, "not just because he is Kane's banker but because he is a banker" (33); the inevitability of the camera's direction, we assume, relocates the perspective and the expression in a single mindscreen, Thatcher's. A stable camera, providing us with the first of the celebrated deep-focus shots in Citizen Kane , now clearly frames four characters: Mary Kane renouncing her son, Thatcher busily pushing the papers to her, Jim Kane pacing in the middle ground, and Charles—to whom all except us seem oblivious—playing happily in the snow. Once again, though, the point of view and the voice have splintered. A banker of narrow vision, Thatcher is incapable of generating the contrasts and emotions so richly elaborated through the use of deep focus. Meticulously organized, this long-enduring shot has an "authoritarian effect," James Naremore says, "the actors and the audience under fairly rigid control" (42–43). Whose control matters less than the implications of the shift: our assumption again proves erroneous, our expectation unfulfilled. Less than a minute into the flashback, the perceptual and the "interest" points of view as well as the perspective and the expression have fused

and diverged more than three times. From whose point of view is Thatcher's story told? Our experience of the text makes any response problematic.

Having signed the papers, Mrs. Kane returns to the window. The camera, via a cut, points into the house from its position at the porch. Mrs. Kane's previous insistence on orchestrating the event ("It's going to be done exactly the way I've told Mr. Thatcher"), her resolve ("I've had [his trunk] packed for a week now"), and her expression make her the scene's dramatic center. Although deep focus is again employed, the composition offers us little of interest beyond the foreground and Mrs. Kane. Jim Kane and Thatcher stand in the middle distance where, uncharacteristically for this narrator, Thatcher hesitantly remains. Mrs. Kane's seemingly blank expression draws significance from the music, somber chords in the low register of the strings. She responds to Thatcher's comments on the practical aspects of Charles's departure, but her thoughts are obviously elsewhere. This time, the camera moves only after she does. When Mrs. Kane turns screen left to walk outside, the camera tracks left to follow her. The prevailing mindscreen seems hers. The pan across the log face of the house cuts off Thatcher in the middle of a speech: "I've arranged for a tutor to meet us in Chicago. I'd have brought him along with me. . . ." The banker chooses his words too carefully and regards himself as too important to leave any thought incomplete; the interruption of a line of his dialogue does nothing to reestablish his mindscreen. But neither does it support our assumption that Mrs. Kane narrates. We could read the incident as a representation of Mrs. Kane's selective hearing, her preoccupation with Charles obliterating the world around her. The music does suggest this continuity in point of view. The disappearance of the dialogue track, however, directly parallels only those moments when Thatcher and Mrs. Kane are out of view and thus suggests a narrating presence outside of both characters. The suspension of sound might thus signal the return of the supra-narrator or—as the camera's placement outdoors may already have anticipated—the emergence of Charles.

When Mrs. Kane exits from the door, she calls, "Charles." Her son replies from off-screen, "Lookee, Ma." Charles beckons his mother and readies us to see what he sees, perhaps as he sees. The camera, already outside, pulls back to position itself just behind Charles. Mrs. Kane, the only character inadequately dressed for the cold (a noteworthy point), says, "You better come inside, son." The camera's deference toward Mrs. Kane (though outside, it has centered on her) and the association of Charles with the natural world (he has even a snowy complexion) as well as his insistence that we see what he sees lend each character some claim to point of view. Just as we are tempted to anticipate the dominance of one or the other, Thatcher steps forward: "Well, well, well, that's quite a snowman." In this shot, which lacks multiplaned clarity and momentarily the

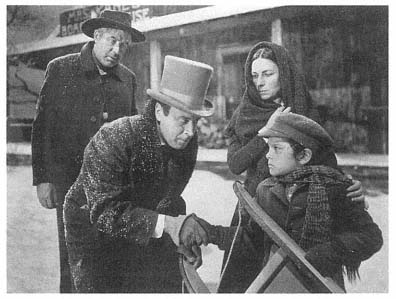

Citizen Kane

scene's expressive music, an ingratiating man tries to cajole a peevish child into the adult world ("Now can we shake hands . . . what do you say? Let's shake"). The camera foregrounds the action and moves only to contain it. The image of Charles's assault on the unsuspecting banker, photographed efficiently, with no musical accompaniment, seems derived from Thatcher's mindscreen. For only the second time in the scene, we have the sense that the putative narrator and the actual narrator are one.

At Jim Kane's awkward attempt to strike Charles ("what that kid needs is a good thrashing"), Mrs. Kane enfolds her son in her arms. All of the scene's conflict between mother and father and, later, guardian and child has not obscured a question that we have been formulating and that now will be answered: why is Mrs. Kane sending away her son? The film cuts to a tight close-up of her, accompanied by a musical crescendo, as she says: Charles is "going to be brought up where [his father] can't get at him." Many consider her reason inadequate, yet it supports a common assumption about the flashback. Along with Kawin, virtually every critic regards Thatcher as the scene's constant narrator. ("The point is not that Thatcher is photographed from outside his physical viewpoint," Kawin says, "but that every scene corresponds with his personal conception of Kane, and illustrates this conception rather than subjectively records 'what happened'" [34].) If we truly regarded Thatcher as the narrator of the moment being discussed, we would celebrate Mrs. Kane's chilly response because its very tenuousness validates Thatcher as narrator. She

translates her feelings into a pragmatic business decision that Thatcher would understand, accept, and unemphatically report. But the cut to the close-up does something that no critic has acknowledged: it compromises Thatcher's mindscreen. The transfer of guardianship represents the banker's opportunity to manage a fortune, period. He has no interest in probing for the situation's psychological dimension, the possible but unarticulated reasons underlying Mrs. Kane's decision. His sensibility calls for retention of the long shot, an appropriate distance for incorporating but not highlighting what Mrs. Kane says.

More than a division between the perspective and the expression, the close-up of Mrs. Kane and the evocative music originate with a narrator eager or prepared for her response; they focus our attention exquisitely and ready us for emotions laid bare, for intimate truth. When the dialogue frustrates that expectation, we are left with a problem that the text has raised but declined to solve. Here the critics have stepped in. "The accident which made the Kanes suddenly rich," Joseph McBride explains in Orson Welles , "has its own fateful logic—Charles must 'get ahead'" (43). In "Power and Dis-Integration in the Films of Orson Welles," Beverle Houston argues that Mrs. Kane exacts a "cruel pleasure" by defeating the prerogative of husband and son; in her action lies "the hint of a revenge" (3). These and other interpretations, though not unreasonable, miss the point. At this moment, the text has slipped out of our control: we may not say with any certainty why Mrs. Kane sends away her son. To insist upon one reason over another is to attempt to return the responsibility for meaning to the text when it belongs with the reader. Our experience of the apparent inadequacy of Mrs. Kane's response coupled with the shift in point of view is finally the meaning of this moment in Citizen Kane .

Mrs. Kane explains her reason for sending away Charles and turns toward him. Moving—not tilting—down, the camera exchanges a close-up of the mother for one of the child. Charles's scowl as he looks up initially suggests again Thatcher's mindscreen. A downward angle of the camera rather than an eye-level shot would underscore this point, but Charles's defiant expression surely squares with Thatcher's perception of him. May we be sure, however, that Charles glowers at Thatcher? The boy's glance up and right could be directed at Jim Kane, who just now verbally and (almost) physically abused him and who now stands at Thatcher's immediate left. Whether Thatcher or Kane, the object of Charles's scorn becomes an ambiguity that we expect to be resolved. Jean-Pierre Oudart and Daniel Dayan's theory of the "absent one," set forth in "The Tutor-Code of Classical Cinema," suggests that the next cut (or, alternatively, further movement of the camera) will provide the necessary reaction shot. If Jim Kane is its subject, it will support Mrs. Kane's explanation for apparently spurning Charles, a justification that Thatcher would be likely to accept at face value and duly report. If Thatcher is its subject, it will reveal

yet a different object of the hostile young Kane's wrath. Thatcher's mind-screen, of course, could project either shot.

From Charles's sullen face, the film cuts to neither Thatcher nor the father. Instead, it dissolves to the boy's sled. The sound of a train whistle far in the distance, connoting Kane and his guardian's movement east, temporally links Thatcher to the on-screen image; the insistent, hurrying whistle punctuates his earlier haste to catch the train. But even though the sound track might reflect Thatcher's aural perspective, the imagery makes his origination of the shot problematic. To Thatcher, the sled is a weapon in his "encounter" with "Mr. Kane"; he refuses even to discuss the sled when directly questioned about it during a congressional investigation (depicted in the News on the March short). The tremulous music and the long duration of the shot (actually two shots subtly joined by a dissolve) give the image an almost melancholy placidity, one whose tone conflicts with the banker's attitude toward Charles and his desire to put Colorado behind them. So the dissolve from Charles's face to the sled not only frustrates our expectation that we will discover the object of the boy's scorn but also calls into question Thatcher's mindscreen.

The image of the sled could well be Mrs. Kane's projection. Throughout the preceding scene, she has frequently appeared distant. When she watches Charles playing in the snow ("I've got his trunk all packed"), her look is fixed, contemplative. The sled tells us nothing more about why she sends away her son, but in its lingering stillness, perhaps evoking the absent boy, it seems a perfect object of her gaze. And though Thatcher has gone, the Colorado setting remains, making her a viable choice as narrator. Because it follows the shot of Charles's face, however, the image of the sled could also be his projection. Earlier we felt the imminence of his mind's eye; perhaps here we discover not who he looks at but what , in mindscreen. In the parlor car with Thatcher, listening to the plaintive whistle of the train carrying him far from home, he might be thinking of the sled. Read from his mental perspective, the image might seem to embody his loneliness. Finally, of course, a supra-narrator might generate the image of the sled. In tone, it resembles many similar shots in the film's opening scene, presumably authored by the supra-narrator; like them, it is bracketed by dissolves and accompanied by an unmelodic musical theme. In brief, the shot of the sled proceeds from an author whom we may not identify with any certainty. The shot thus doubly frustrates expectation.

In the next scene, we see paper being torn from a package. A still youthful Charles is opening his Christmas present, a new sled. "Well, Charles," Thatcher says offscreen. A pause follows this line, which concludes, "Merry Christmas." "Well, Charles," the line may mean, "here's exactly what you asked for." This scene privileges Charles: a head-on shot of him looking up at Thatcher concludes with a tilt up to a low-angle shot of Thatcher looming

over him. Thatcher's mindscreen predominates. Charles's "Merry Christmas," which connotes surly ingratitude and is photographed from Thatcher's point of view, squares with Thatcher's view of the boy as presented at the congressional investigation. The next two scenes, showing Thatcher's increasing exasperation with Charles's profligacy and his foolish belief that "it would be fun to run a newspaper," also suggest his mindscreen; the camera moves in tandem with him as he dictates a letter to urge responsibility on his charge, and when the scene concludes, Thatcher's eye directly meets the camera's lens, as if to bond the narrator and the narratee. In the succeeding montage, however, Thatcher's dyspepsia while reading issues of the Inquirer becomes the butt of a cinematic joke. The dynamic visuals, the pulsating editing rhythm, and the high-spirited music convey none of the dryness of Thatcher's prose; they lead us, in short, to conclude that in this most unstable of texts, the narrator has again changed.

The montage functions as a lively curtain-raiser to Thatcher's first direct confrontation with the adult Kane. The film's second-time viewer draws an inescapable conclusion from the scene. An "emperor of newsprint," Kane galvanizes the Inquirer , a sleepy daily paper with a genteel staff. On one occasion, as Bernstein's flashback shows, he has his reporters impersonate the police, bully the husband of a presumably missing Brooklyn woman, and trump up a front-page story where no story exists. Kane calls this "the truth" and delivers it "quickly and simply and entertainingly." The montage that drives Thatcher into Kane's office mirrors Kane's philosophy of yellow journalism—it is entertaining, zestful, and inflammatory. The montage represents the pounding of Thatcher as the young Kane might imagine it, perhaps through "the field of the mind's eye."

Linked seamlessly to the montage, the scene in the Inquirer office moves Kane center screen. If, as Bruce Kawin argues, Thatcher narrates it through mindscreen, the banker chooses uncharacteristically to minimize his presence. "Bernstein appears in all the scenes he relates," Kawin tells us, "and the camera continually pays attention to him" (35); Kawin can make no such statement about Thatcher. The banker, dressed in black, appears at the periphery of the frame, almost blending in with the screen's dark border. Kane, on the other hand, appears in the center in white. Although the parallel placement of Thatcher and the camera might seem to bond these two as narrators, Kane dominates the scene and sets the tone. The "I" of the Thatcher manuscript is simply in eclipse.

Again, James Naremore describes what we see:

[Kane] is at his most charming and sympathetic during the early scene in the newspaper office, where his potential danger is underlined, but where

he is shown as a darkly handsome, confident young man, loyal to his friends and passionate about his work. This is, in fact, the point of Welles's full-scale entry into the film, and it is predictably stunning. . . . Here at last, greeted by a triumphal note of Herrmann's music, is the young Welles of Mars panic fame (79–80).

But which Welles? The celebrity? Though he may be drawing on his confrontations with naysayers in radio or the theater, Welles seems to be doing more than "playing himself." In this scene Kane assumes the role in which he has cast himself, the crusading journalist whose pleasure it is both to "look after the interests of the underprivileged" and in the process, apparently, to thwart his ex-guardian. As he will win over the Inquirer's subscribers, he wins us over by letting us experience his exuberance, his power to captivate the readers of newspapers and films. Naremore calls Kane's (Welles's) entrance "predictably stunning." What stuns us, even in a text whose inconstancy of point of view has been established, is the exchange of Thatcher's harsh perspective for a point of view so strongly indicative of Kane's mindscreen.

Countering his guardian's protest that the Inquirer will drain his capital, Kane admits that he will lose at least $3 million on the paper. "You know, Mr. Thatcher, at the rate of a million dollars a year . . ." (at this point, the film cuts from the medium shot of the two men to a close-up of Kane, his eyebrows lifted in mockery of Thatcher) ". . . I'll have to close this place in sixty years." When audiences laugh at this punch line, as they invariably do at screenings I have attended, they are responding positively to this "charming and sympathetic" man. Kawin might have argued (though he does not) that the close-up proceeds from Thatcher's mindscreen in order to demonstrate what a smart aleck Kane really is. Yet the music that punctuates Kane's line—a muted horn playing a presto version of the "newspaper theme"—snickers (as Kane does) at Thatcher's narrow conservatism. This witty, idealistic newspaper publisher conjures up an appealing persona in this scene of the film, and after taunting Thatcher throughout it, he even gives himself the last spoken word. From the driving energy of the montage to the conspiratorial intimacy of the close-up, we seem to experience through Kane's own perspective the Kane that Bernstein, Leland, Susan, and so many others fell for. The close-up, excluding Thatcher, the newspaper office, and the rest of the film's world, brings us into such close proximity to Kane that we neither desire nor expect a return to a narrative frame whose existence has all but been forgotten. A very rapid dissolve, however, exchanges Kane's smiling face for our second glimpse at Thatcher's manuscript: "In the winter of 1929 he . . ." This entry hardly gives Thatcher "the last word": it describes an event that occurred over thirty years after his confrontation at the Inquirer , when general economic conditions, not

Citizen Kane

the management of the newspaper, disabled Kane. Thatcher's cheerless control of the narrative has nonetheless returned and with it the need for our renegotiation of the text.

Some may reject the notion that Citizen Kane asserts Kane's mindscreen; after all, Kane dies in the opening scene. Yet the film's framing structure has only a superficial integrity, whose violation we experience less than sixty seconds into the first flashback. (Note, too, that although we assume that the dying man is Kane, we see only his silhouette and a fragment of his face.) Throughout Citizen Kane , we experience a divergence between perspective and expression and, moreover, between the putative narrator and the actual narrator that seems to make tenable, however unexpected or improbable, the presumably dead Kane's somehow being brought to life. Exhilarating and perplexing in the short run, what do these glimpses into Kane's world through Kane's mind's eye do? They return us to the film, again and again, to discover what we already know to be true but cannot quite accept. Each interpreter of Citizen Kane has a different slant on it: James Naremore tells us that Rosebud is important, Robert Carringer (in "Rosebud, Dead or Alive") that the glass paperweight is important, Ira Jaffe that window imagery is important. The fact that essayists continue to argue for a thematic center in Citizen Kane suggests the weaknesses of the formalists' approach: no one answer can satisfy us. Despite what these and other critics tell us, the text does not stand still; it continually challenges us not to settle on sleds, paperweights, or windows. The sporadic, ephemeral, yet insistent suggestions of the Kane mindscreen constitute a major index to the text's instability, which response-centered criticism allows us to apprehend. As Stanley Fish says, it permits us to "slow down the

reading experience so that 'events' one does not notice in normal time, but which do occur, are brought before our analytical attentions" (28). What we know of Citizen Kane , whether its symbolism or its point of view, we know only through the activity of reading, our making of assumptions, revisions, and new expectations. In a temporal interpretation of the film, based on our moment-by-moment experience of it, we finally discover all that we know of the text.

From its opening credits and first sequence, with its persistent advancing camera, Citizen Kane raises and frustrates the reader's expectation of coming to know Kane. Our consistently revised assumptions, however, permit us to experience and learn the work's very object lesson, the danger of closing on the text. This strategy of reader education continues to the end of Citizen Kane . In Xanadu's Great Hall, a frustrating search behind us, we believe with Thompson that no word can explain a man's life; as the camera retreats from Thompson and his colleagues and we see the clutter that Kane has left behind, we recognize that Rosebud is indeed "a"—not "the"—missing piece to a jigsaw puzzle. But a dissolve to the cellar changes the camera's direction, from withdrawal to advancement. Above the boxes and crates, we move forward, apparently toward something. The camera probes, the music builds, and suddenly the sled and its emblazoned name appear before us. Robert Carringer warns us against accepting the sled as "the principal insight into Kane" (185), while Joseph McBride argues that the shot of the sled "does in fact solve nothing" (43). If not "the principal insight," however, "Rosebud" is an insight. And although it may not unlock the psychology of Kane's character, it provides a referent for the film's first spoken word and grants us at least nominally what for almost two hours we have longed to know.

Irrespective of "meaning," the shot of the sled gives many viewers a rush; it does something to them. With the roll on the timpani and the swelling ritardando, we experience a long-delayed pleasure that we perhaps had assumed, especially given the film's lack of convention, would be denied us. The shot of the sled is particularly felicitous because it seems just compensation for the disappointments and frustrations that we have endured. It may not "solve" anything of major significance in Kane's life, but it gives the film—and us—a sense of closure. Indeed, the shot of the sled concludes with a fade-out, leading us to expect a title card that reads "The End." But a fade-in returns us to the exterior of the mansion, where black smoke rises from the furnace chimney. With a dissolve we are immediately before the chain link fence, and as the music becomes eerier, more somber, we follow the camera down to the "No Trespassing" sign. Draining the excitement of the shot of the sled, this anticlimactic sequence seems to introduce a more restrained voice into the narrative. Let us consider, moment

by moment, the film's proffered solutions to the Kane enigma: Thompson argues inexplicability. To formalist critics, the audience's euphoria on discovering at least the identity of Rosebud means nothing in light of the recognition that the audience is back where it began. Yet the experience of having the ostensibly conclusive answer to Kane's character superseded by the unsettling image of the sign draws attention to our wish for compact solutions to complex problems. The act of knowing, we come to realize, is a temporal process, based on assumptions ever subject to question, challenge, and revision.

Superimposed over a shot of the mansion and its massive initialled iron gate, the words "The End" appear. A trumpeting resolving chord concludes the music as the image fades out. Five seconds pass, the screen silent and dark. We do not assume, we know: the film has at last ended. Then, however, a title card fades in; The Mercury Theater, it notes, proudly introduces the cast. Outtakes have recently been used as codas to some Burt Reynolds films and, more trenchantly, to Being There (1979). The tail credits for Citizen Kane , though, contain no gaffes. On screen, the principals reprise a line of dialogue. Though each shot seems to have been lifted from the film proper, all of the footage comes from alternate takes, most of them containing less incisive readings than those in the body of the film. These visual tail credits constitute pieces of a rough draft designed by the implied author to reveal for the last time his strategy of betrayed expectations. We may infer from them the existence of not only other Kanes but other Kanes . Who is Kane? As even the music suggests, we can never know. The rhythmic theme that accompanies the tail credits resembles the spirited "chasers" used to empty theaters between screenings in the nickelodeon era; it is heard earlier, of course, as the song that attempts to build the myth of "good old Charlie Kane." Its words carry an insistent refrain: "Who is this one . . . who is this one . . . what is his name . . . what is his name?" The very opening of Citizen Kane , which teasingly heralds the name and apparently the identity of the film's central character, also introduces through its truncated credits the first frustrated expectation. Although the tail credits now fulfill one aspect of that expectation, they do not include Orson Welles/Charles Kane among the images of the "principal actors." The absence of Kane and the reprise of that rousing campaign song with its interrogative lyrics signal for one last time Kane's elusiveness. Where is Kane? Who is that man? These two implied and unanswered questions, part of our experience of the film's last moments, suspend, indefinitely, our closing on Citizen Kane .

All of us who study Citizen Kane share an intellectual pleasure in it, but do we return to the film because we seek fresh support for our theses (Rosebud is/is not significant) or because we find our theses inadequate to explain the film's hold over us? Each of the work's putative narrators claims special knowledge of Kane. Thatcher entitles his journal entry "Charles Foster Kane,"

suggesting its comprehensiveness. Leland remembers "absolutely everything" about Kane, and even after a night of drinking, Susan tells Thompson that "a lot comes into my mind about Charlie Kane." The supra-narrator descends upon the burning sled with complete confidence in its unifying symbolic value; the shot provides the visual equivalent of Raymond's assured boast, "I tell you about Rosebud." Critics of Citizen Kane close on the film with no less certainty. But how valid is their analysis? In interpreting Citizen Kane , they neglect our experience of Citizen Kane , of the cinematic techniques—the long take, moving camera, deep focus—that lead to assumptions unfulfilled, of the shifting points of view that promise and ultimately frustrate our ability to draw definite conclusions about Kane, of our impossible goal of extracting a meaning from this or any work.

Tennyson's Ulysses calls "experience . . . an arch wherethrough / Gleams that untravelled world whose margin fades / Forever and forever when I move." Ulysses' experience of life resembles our experience of this remarkable film. As we read Citizen Kane , the "meaning" seems never present but always ahead. In any reader-centered text, inexhaustible and forever potential, closure is impossible. Thompson's conclusion says as much for Citizen Kane: no "word [read 'text'] can explain a man's life." Since readers, not words, produce meaning, the reading of Kane (and Kane ) will never be finished. Nor should it be. "Coming to the point," Stanley Fish writes, "is the goal of a criticism that believes in content, in extractable meaning, in the utterance as a repository. Coming to the point fulfills a need that most literature deliberately frustrates (if we open ourselves to it), the need to simplify and close. Coming to the point should be resisted . . ." (52). Each time we watch Citizen Kane , we have at hand the answer to its ambiguities. The very activity of reading brings Kane into existence: in the making and revising of assumptions about the text, its point of view and other myriad complexities, we actualize it, and when we have concluded our reading of Kane , only our experience of Kane remains.

Works Cited

Browne, Nick. "The Spectator-in-the-Text: The Rhetoric of Stagecoach." Film Quarterly 29, no. 2 (1976): 26–38.

———. "Narrative Point of View: The Rhetoric of Au Hasard, Balthazar." Film Quarterly 31, no. 1 (1977): 19–31.

Carringer, Robert. "Rosebud, Dead or Alive: Narrative and Symbolic Structure in Citizen Kane." PMLA 91 (1976): 185–193.

Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Citizen Kane . Dir. Orson Welles. RKO, 1941.

Dayan, Daniel. "The Tutor-Code of Classical Cinema." Film Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1974): 22–31.

Fish, Stanley. Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Henderson, Brian. "Tense, Mood, and Voice in Film (Notes After Genette)." Film Quarterly 36, no. 4 (1983): 4–17.

Houston, Beverle. "Power and Dis-Integration in the Films of Orson Welles." Film Quarterly 35, no. 4 (1982): 2–12.

Jaffe, Ira S. "Film as the Narration of Space: Citizen Kane." Literature/Film Quarterly 7 (1979): 99–111.

Kawin, Bruce. Mindscreen: Bergman, Godard, and First-Person Film . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles . New York: Viking Press, 1972.

Naremore, James. The Magic World of Orson Welles . New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Riffaterre, Michael. "Describing Poetic Structures: Two Approaches to Baudelaire's 'Les Chats.'" Reader-Response Criticism from Formalism to Post-Structuralism . Ed. Jane P. Tompkins. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980. 26–40.

Welles, Orson, and Herman J. Mankiewicz. Citizen Kane . In Kael, Pauline. The Citizen Kane Book . Boston: Little, Brown, 1971.