Part Three

The Politics of Mind and Body: Radical Practitioners and Revolutionary Doctors

Seven

States of Mind:

Enlightenment and Natural Philosophy

Simon Schaff er

The voice of the Devil:

All Bibles or sacred codes have been the cause of the following Errors:

1. That Man has two real existing principles: Viz: a Body & a Soul.

2. That Energy, call'd Evil, is alone from the Body; & that Reason, call'd Good, is alone from the Soul.

3. That God will torment Man in Eternity for following his Energies.

—WILLIAM BLAKE, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-1793

If it were possible to find a method of becoming master of everything which might happen to a certain number of men, to dispose of everything around them so as to produce on them the desired impression, to make certain of their actions, of their connections, and of all the circumstances of their lives, so that nothing could escape, nor could oppose the desired effect, it cannot be doubted that a method of this kind would be a very powerful and a very useful instrument which governments might apply to various objects of the utmost importance.

—JEREMY BENTHAM, Panopticon; or, The Inspection-House, 1787-1791

THE PRISON OF THE BODY

The relationship between mind and body provides graphic political images of knowledge and power. The slogans composed by Blake and Bentham in the early 1790s are good examples of this imagery. Blake wrote against "the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul." He said that this false notion bred a self-imposed imprisonment of the mind: "man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern." Political liberty went hand in hand with spiritual liberty. The destruction of the Bastille was figured as the action of

Abbreviations:

Bowring: John Bowring, ed., The Works of Jeremy Bentham , 11 vols. (Edinburgh, 1838-1848).

Rutt: John T. Rutt, ed., The Theological and Miscellaneous Works of Joseph Priestley , 25 vols. (London, 1817-1832).

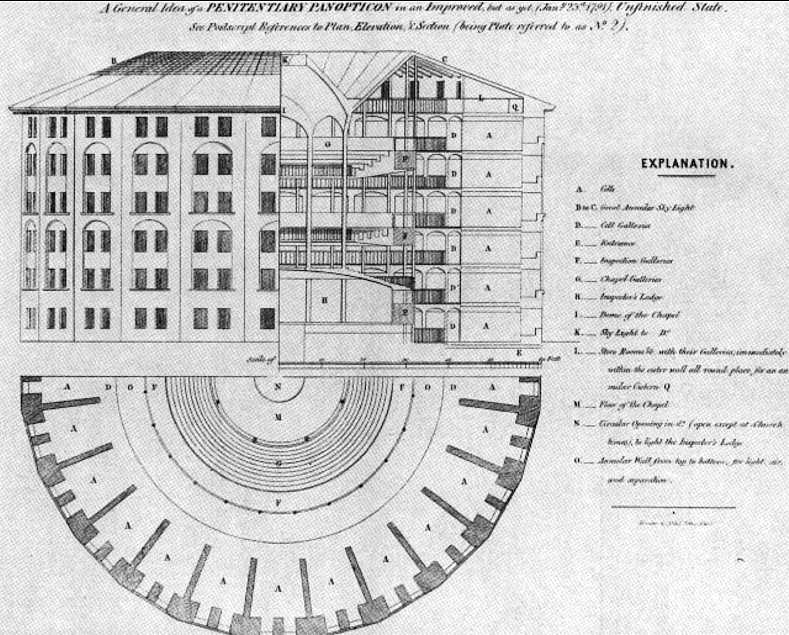

liberating energies in the human mind. So, pastiching Emmanuel Swedenborg's visionary cosmology, Blake proposed a new Code, the "Bible of Hell" directed against old penology and old morality: "Prisons are built with Stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion." Bentham also proposed a new Code to replace old penology and morality, and he also represented this radical reform through an appeal to the relation of bodies and minds. He claimed that in his Panopticon a remakable architectural arrangement of bodies allow the possibility of the "power of mind over mind." In this visionary building, a concentric ring of cells was to be arranged around a central guard tower and a chapel. From the tower, the warden could survey every denizen of the "inspection house" but would always remain invisible to these inmates. The plan was to be fitted to prisons or factories, schools or workhouses—in short, any model polity that demanded the supervisory power of an "invisible eye." The members of such a polity were to be governed through the complete management of their atmosphere and their surroundings. The Panopticon relied on the link between the bodily situation of its inhabitants and their state of mind. The right distribution of light, air, and space prompted the right associations: every inmate would "conceive himself" to be under constant surveillance.[1]

The Panopticon was an "enlightened" project, concerned with rational order and moral reform, deriving its authority from the natural philosophical understanding of the work of the mind. Spectacularly unsuccessful in reformed Britain, the scheme was initially drafted for the enlightened despotism of Russia and greeted with rapture in Revolutionary France. It has always invited allegorical interpretation. Its author helped himself to the language of a secularized theology: the Panopticon combined "the apparent omnipresence of the inspector (if divines will allow me the expression)" with "the extreme facility of his real presence." He told his Girondin admirer J. P. Brissot that it was "a mill for grinding rogues honest and idle men industrious," and yet confessed in private that it was "a haunted house." For William Hazlitt, the Panopticon was a "glass beehive," a scheme marked by luminous clarity, impractical idealism, and deadly obsession. Edmund Burke was even more scathing: "there's the keeper, the spider in the web." Recent com-

[1] William Blake, Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), 154, 151; Bowring, 4:66, 79, 40. For Blake and Swedenborg, see Mona Wilson, The Life of William Blake (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 56-60; for Blake and the Revolution, see David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet against Empire, 3d ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), 175-197.

mentators, no less critical, have found that Bentham's vision provides fruitful evidence of Enlightenment mentality. Bentham has been castigated for the pursuit of crass commercial gain under the mask of disinterested reform, thus damning the motives of future generations of his utilitarian disciples. He has been celebrated as the author of a "symbolic caricature of the characteristic features of disciplinary thinking in his age." Under the inquiring gaze of Michel Foucault, the Panopticon has been transformed into the ideal type of a "microphysics of power," "at once a programme and a utopia," whose disciplinary strategy of surveillance and individuation marked the birth pangs of the human sciences. Precisely because of this exemplary history, the Panopticon and its author's career provide important clues to the concerns of a reforming philosophy of mind and body in the age of reason.[2]

The concerns of the reforming philosophers connected a model of the right role to be performed by expert intellectuals and a picture of mind and body. The Panopticon was a sign of a reconstructed discipline, both a new way of exercising power and a new form of knowledge. Foucault argued that this discipline was accompanied by the emergence of "the modern soul." Displaced from Christian theology, this soul was at once the site at which power was to be exercised and the object of which knowledge was to be produced. Hence Foucault's characteristically gnomic remark about the relationship between the subject of the enlightened philosophy of mind and the regimes of corporeal discipline these philosophers proposed: "the soul is the effect and instrument of a political anatomy; the soul is the prison of the body."[3] More prosaically, the account of the mind produced by Bentham and his colleagues directly confronted established religion and moral philosophy. Apparently

[2] Bowring, 4:45; Bentham to Brissot, [1791], in Bowring, 10:226; for the "haunted house" see Bowring, 10:250; for Hazlitt, see William Hazlitt, The Spirit of the Age (1825; London: Henry Frowde, 1904), 12-13; for Burke, Bowring, 10:564. For commentary on the Panopticon, see Gertrude Himmelfarb, "The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham," in Victorian Minds (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1968), 32-81; Michael Ignatieff, A Just Measure of Para: The Pentitentiary in the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850 (London: Macmillan, 1978), 113. For Michel Foucault on "panopticism,' see his Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979), 200-209; "The Eye of Power," in Power-Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 146-165· For comments on Foucault's account, see Michelle Perrot, ed., L'impossible prison: Recherches sur le systèrae pénitentiaire au XIXe siècle (Paris: Seuil, 1980); Martin Jay, "In the Empire of the Gaze: Foucault and the Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought," in Foucault: A Critical Reader, ed. D. Couzens Hoy (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 175-204.

[3] Foucauh, Discipline and Punish, 29-30.

Pl. 14. Jeremy Bentham, "A General Idea of a Penitentiary Panopticon" (1787).

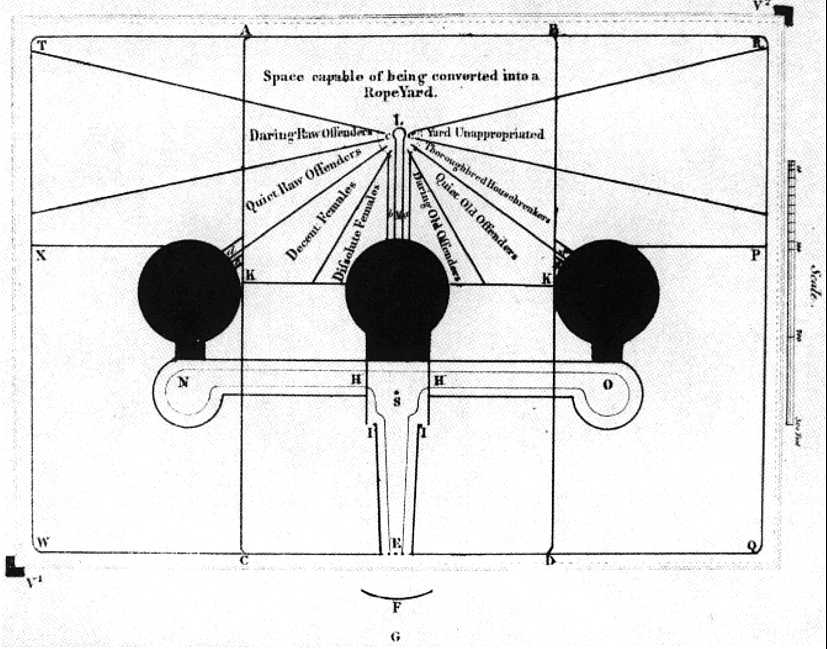

Pl. 15. Jeremy Bentham, "A General Idea of a Penitentiary Panopticon" (1787).

abstruse exchanges on the immortality of the soul, the possibility of thinking matter, and the character of human motivation carried explicit political resonances. Traditional guardians of moral conduct were to be displaced by philosophers who knew the material sources of passions and interests. Materialist philosophy was allied with a natural philosophical inquiry into the activity of matter and life. It was also allied with reformist projects for the redistribution of authority in the social order.

To provide an example of this network of alliances, a case is taken from the work of some English clerics and lawyers in the 1770s. As Foucault suggested, "these tactics were invented and organised from the starting points of local conditions and particular needs." In this paper, the locale is provided by the work of Joseph Priestley, a dissenting minister at Leeds until 1773 and subsequently the Earl of Shelburne's librarian at Bowood House in Wiltshire until 1780, and of Bentham himself, working in London as a legal writer until he became Shelburne's client in 1781. The connections between these men play an important part in my argument. The "Bowood group," of whom Bentham and Priestley were members, with others such as Richard Price and Samuel Romilly, was later to be identified as a key source of subversive ideas by anti-Jacobins in the 1790s. The enterprise connected with Shelburne, organized under the banner of economic and philosophical reform, provides a convenient site from which to investigate the links between natural philosophy, epistemology, and reforming civil philosophy at this period. While at Bowood, Priestley composed a lengthy series of texts that criticized contemporary philosophies of mind, notably those developed in Scotland by Hume and the Common Sense school, and offered a challenging materialist account of moral philosophy and of mind and body, based on the theories of David Hartley and Priestley's views of proper religion. At the same time, Priestley was actively engaged in political and religious campaigning for civil reform and the emancipation of dissent. Shelburne also provided Priestley with support for his research in pneumatic chemistry, which was inaugurated just before the move to Bowood. Similarly, it was during this period that Bentham began his composition of an ambitious series of texts on political and legal reform and his search for influential backing for these schemes, of which the Panopticon was the most celebrated. The admiration of Benthamite disciples and the hostility of conservative critics have often obscured the process through which these visionary proposals were formed. It will be emphasized that the utopian character of the work mounted by Priestley and Bentham at this period is a significant aspect of their campaigns. Priestley's strong commitment to a millenarian vision of humanity's fu-

ture, and Bentham's extraordinary dreams for that future—and his part in it—are among the more striking aspects of their knowledge of civil society and of natural order. The reformers were visionaries because to change the state they had to change minds.[4]

This paper is divided into five sections. The first explores an ambiguity in the sense of "enlightenment" as it was used in late-eighteenth-century Britain. During the 1790s, in particular, conservative critics of radicals and reformers argued that the "light" of these philosophers was indistinguishable from the "illumination" of occult mystics and enthusiasts. They pointed out a peculiar feature of the social organization of the reformers, the Masonic club or secretive association of like-minded members of the intelligentsia. The anti-Jacobins then argued that this social form promoted a subversive form of knowledge: the dangerously ambitious account of mind which materialist philosophes used to explain and defend the deeds of the Revolution. The ambiguity of "enlightenment" depended on the ambiguity of reformist philosophy, a knowledge that promised both freedom and discipline. Conservatives interpreted this freedom as anarchy and this discipline as tyranny. Radicals promised a world of free individuals who would pursue the dictates of reasoned self-interest. In contemplating Foucauh's analysis of the Panopticon, Jacques Léonard has pointed out that "utilitarian rationalization and political rationalism go together; one must pause here over masonic philosophy: the mason builds and frees."[5] The conservative attack on the visions of the reformers suggests a promising line of inquiry into the interests of their philosophy. In particular, it suggests a link between the social forms of patronage and association and the philosophy which the reformers espoused. The second section of the paper documents the local setting of the work of Priestley and Bentham in the 1770s and 1780s, when they were working closely with Shelburne on schemes

[4] For Foucault on the local context, see "The Eye of Power," 159. For Bentham and the Bowood group, see Charles W. Everett, The Education of Jeremy Bentham (New York: Columbia University Press, 1931), 122-122, Mary P. Mack, Jeremy Bentharn: An Odyssey of Ideas, 1748-1792 (London: Heinemann, 1962), 370-404. For politics and the Bowood group, see Elie Halevy, The Growth of Philosophic Radicalism (1928; London: Faber and Faber, 1972), 145-150; John Norris, Shelhurne and Reform (London: Macmillan, 1963), 83-85, 250-253; Derek Jarrett, The Begetters of Revolution: England's Relationship with France, 1759-1789 (London: Longmans, 1973), 130-135; D. O. Thomas, The Honest Mind: The Thought and Work of Richard Price (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 142-148; Albert Goodwin, The Friends of Liberty: The English Democratic Movement in the Age of the French Revolution (London: Hutchinson, 1979), 101-l06.

[5] Jacques Léonard, "L'historien et le philosophe," in Perrot, L'impossible prison, 9-28 at 19. Compare Reinhart Koselleck, Krise und Kritik (Munich: Karl Albert, 1959), chap. 2.

for reform in philosophy, religion, and politics. It is suggested that there were important connections between the immediate concerns of this period and the apparently utopian schemes which the reformers proposed. In particular, work on the natural philosophy of the powers of matter, pursued both by Priestley and Bentham in the 1770s, is shown to be an important source for ideas about the progress of society. The link between natural philosophical and social reform lay in a new doctrine of pneumatics, of the behavior of matter and spirit.

In the third section of the paper, this connection is explored in some detail, and it is argued that work in pneumatic chemistry provided powerful resources for an understanding of the way the mind worked and the true doctrine of the soul. Priestley's experimental philosophy and the way he suggested experimenters should work generated a materialist philosophy of mind and a reconstruction of the orthodox model of the soul. The two final sections of this paper examine the consequences of this materialism. Such a philosophy of mind and of soul involved the development of what can be called a "counter-theology," a vision of the future of humanity which relied on a reform of the understanding of human nature. This understanding argued against dualism, removed the division between body and soul, and made mind an object of philosophical inquiry and reform. Mind could become such an object because it was supposed to be material. Philosophical materialism suggested an appropriate role which these intellectuals should follow, that of the medical manager, the expert equipped with an understanding of what Bentham named "mental pathology." So reforming philosophy posed as a therapy. Alongside their account of current social ills, both Priestley and Bentham wrote histories that explained how society and philosophy had developed. These histories simultaneously explained the source of error and suggested ways of correcting it. Social and philosophical error were due to "fictions," corrupt illusions generated by the interests of those in power. The right philosophy of mind and body would discriminate between the real and the fictional by distinguishing between the material and immaterial. Because both writers saw a link between the current social order and the current crisis of philosophy, they supposed that a future of improvement would be marked by a future of rational triumph. The last section of the paper connects this reformed philosophy of mind and this counter-theology with the visionary character of the reformers' project. While philosophical materialism deprived subjects of the illusory hopes of a spiritual world to come, it affirmed a certain future of advance in the social order. The exemplary deaths of Priestley and Bentham dramatized their attitude to this prospect. Reform would

continue under the guidance of expert managers armed with the right account of mind and body and thus the ability to cure the diseases of the body politic. In the nineteenth century, followers of this reforming philosophy developed new disciplines that sought to survey the mental and bodily habits of the subjects of the state. It is concluded that these new disciplines shared much of the utopianism and ambition of the "enlightened" philosophers of the 1770s.[6]

ENLIGHTENMENT AND ILLUMINATION

Enlightened philosophers grew up in a world of spirits. Priestley recalled that when he was a child in Yorkshire in the 1730s, "it was my misfortune to have the idea of darkness, and the ideas of malignant spirits and apparitions, very closely connected." He also described the "feelings . . . too full of terror" prompted by his strict Calvinist education: "in that state of mind I remember reading the account of the 'man in an iron cage' in the Pilgrim's Progress with the greatest perturbation." Bentham had very similar memories about his upbringing in Essex twenty years later: "this subject of ghosts has been among the torments of my life," he wrote, while Bunyan was again a source of fear: "the devil was everywhere in it and in me too." No doubt this captures a conventional view of "enlightenment": reason destroyed the world of spirits and liberated humanity from superstition. Priestley's "remembrance . . . of what I sometimes felt in that state of ignorance and darkness," he revealed, "gives me a peculiar sense of the value of rational principles of religion." His fears were well known to Bentham, who reminisced about the "sensation more than mental" produced in Priestley by the name of a spirit "too awful to be mentioned." Commenting on his own reading of Pilgrim's Progress, Bentham exclaimed "how much less unhappy I should have been, could I have acknowledged my superstitious fears . . . now that I know the distinction between the imagination and

[6] For materialism and eighteenth-century natural philosophy, see Aram Vartanian, Diderot and Descartes: A Study of Scientific Naturalism in the Enlightenment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953); Robert E. Schofield, Mechanism and Materialism: British Natural Philosophy in an Age of Reason (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970); John Yolton, Thinking Matter: Materialism in Eighteenth Century Britain (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983). For Bentham on "mental pathology," see Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1876), vii; Bowring, 1:304-305. For Bentham on "fictions," see Bowring, 1:235; C. K. Ogden, Bentham's Theory of Fictions (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1932); Ross Harrison, Bentham (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983), 24-46.

the judgement!"[7] This image of enlightenment has proved remarkably robust. Historians of natural philosophy have documented the processes whereby spiritual powers hitherto attributed to divine will or immaterial substances were made immanent in matter and subjected to reasoned experimentation. Enthusiasm was tamed: the mad were confined and their claims to inspiration referred either to somatic causes susceptible to medical treatment or to mental disturbance that needed moral therapy. Spirits no longer walked: astrologers were made the butt of the wits and ghost stories a matter of titillation rather than juridical process. It is suggested that these processes touched both the godly and the dissolute. Philip Doddridge, founder of the dissenting academy where Priestley studied, lectured his pupils on the astrologers, who "may as justly be punished as those who keep gaming houses brothels, &c." Yet he warned that some spirits were real: "Seeing there is something in the thought of such agents as these which tends to impress the imagination in a very powerful manner, great care ought to be taken, that children, from the first notice they have of the existence of such beings, be taught to conceive of them as entirely under the control of God." Priestley and many of his allies were taught such views, and carefully revised them to fit the canons of reason.[8]

Eighteenth-century observers recognized a spreading materialism as a fact of social life. In his study of the Enlightenment's relation with death, John McManners cites an orthodox apologist's rueful lament of 1761: "it seems that it is no longer permissible to speak of the soul except to attack it and to confound it with the instinct of the animals." The long eighteenth-century debates on the powers that could be attributed to mere bodies implied that materialism was only too fashionable: "the very Beaux... Argue themselves into mere Machines," commented a worried enemy of "deism" in 1707. The experimental philosophy that sustained this materialism could be a political weapon: electricity and

[7] For Priestley on ghosts, see Rutt, 1:1-8; 3:50; for Bentham on ghosts, see Bowring, 10:11-21.

[8] For enlightenment, medicine, and enthusiasm, see Roy Porter, "Medicine and the Enlightenment in Eighteenth-Century England," Bulletin of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 25 (1979): 27-40; G. S. Rousseau, "Psychology," in The Ferment of Knowledge, ed. G. S. Rousseau and Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 143-210; Michael MacDonald, "Religion, Social Change and Psychological Healing in England," Studies in Church History 19 (1982): 101-126; Martin Fitzpatrick, "Science and Society in the Enlightenment," Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 83-106. For Doddridge, see Philip Doddridge, Course of Lectures on the Principal Subjects in Pneumatology, Ethics and Divinity (London, 1763), 552, 541. For the academies, see Nicholas Hans, New Trends in Education in the Eighteenth Century (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951), 54-62.

pneumatic chemistry demonstrated the range of powers that matter could display. Hence Priestley's notorious remark that "the English hierarchy (if there is anything unsound in its constitution) has equal reason to tremble even at an air pump, or an electrical machine."[9] Nor was this merely a matter of fashionable libertinism or pious philosophizing. Priestley, Bentham, and their allies saw immediate material necessity in the propaganda for rational knowledge. In 1772 the Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid wrote to Priestley's colleague, Richard Price, praising him for quelling "the present Epidemical Disease of trusting to visionary projects" with the tools of political arithmetic. Reasonable knowledge and the maturity of men of the "middling sort" could reform manners and order even as corrupt a society as the present. What Peter Burke has called "the reformation with the Reformation" mobilized considerable support among the laity. Burke points out the change in the sense of the term "superstition" during this period. A label for powerful and dangerous heresies was transferred to the impotent vagaries of the credulous vulgar. This gave polemical point to the comradely sentiments of the letter from the Derby Philosophical Society which Priestley received soon after the Birmingham mob had destroyed his house and laboratory in 1791: "the sacrilegious hands of the savages at Birmingham" were best combatted with "that philosophy, of which you may be called the father." Erasmus Darwin and his Derby colleagues counseled that "by inducing the world to think and reason," this philosophy "will silently marshall mankind against delusion, and with greater certainty overturn the empire of superstition."[10]

[9] Louis-Antoine de Caraccioli, La grandeur de l'âme (Paris, 1761), xii, cited in John McManners, Death and the Enlightenment (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 159; John Witty, The First Principles of Modern Deism Confuted (London, 1707), v, cited in Yolton, Thinking Matter, 42; Joseph Priestley, Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (London, 1774), xiv.

[10] For political arithmetic, see Thomas Reid to Richard Price, [?] 1773, Correspondence of Richard Price, ed. W. Bernard Peach and D. O. Thomas (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1983), 1:154; Peter Buck, "People Who Counted: Political Arithmetic in the Eighteenth Century," Isis 73 (1982): 28-45. For moral reformation, see R. W. Malcomson, Popular Recreations in English Society, 1700-1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), chap. 7; Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (London: Maurice Temple Smith, 1978), 239-242. For Priestley and the Derby Philosophical Society, see Derby Philosophical Society to Priestley, 3 September 1791, in Rutt, 2:152; compare E. Robinson, "New Light on the Priestley Riots," Historical Journal 3 (1960): 73-75; French chemists to Priestley, July 1791, in R. E. Schofield, Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1966), 257-258: "we have therefore resolved to re-establish your Cabinet, to raise again the Temple which ignorance, barbarity and superstition have dared profane."

The opponents of men such as Priestley and Darwin were swift to see through these assaults on "delusion" and "superstition." In his remarkable survey of the sinister conspiracies of the philosophes and their "illuminated" allies, the Edinburgh natural-philosophy professor John Robison argued in 1796 that a real danger lurked behind this "silent" campaign. In his Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, Robison compared the virtuous religion of Newton's celebrated General Scholium with Laplace's Système du monde. He cited Laplace's attack on "the dangerous maxim that it is sometimes useful to deceive men in order to insure their happiness." What were these "deceits"? "They cannot relate to astrology," Robison suggested, "this was entirely out of date." So Laplace was assaulting the doctrine of the nobility of man and his difference from beasts: materialism bred arrogance among the intellectuals and abasement among their followers.[11] Robison was one of many anti-Jacobin writers of the 1790s who made these points. "Is superstition the greatest of all possible vices?" Burke asked in 1791. No, for it was "the religion of feeble minds, and they must be tolerated in an intermixture of it, in some trifling or some enthusiastic shape or other." Burke and his admirers held that the disasters of the Revolution demonstrated three key principles of contemporary intellectual life. First, there were identifiable bands of self-styled enlightened philosophers whose sinister associations masked silent plots to subvert established order. Second, these associations promoted a materialist doctrine of mind, bolstered with a false natural philosophy, in which the status of the intellectual reformer was exaggerated and the aspirations of men reduced to the level of beasts. Last, the exaggeration of the powers of reason was no better than a revamped enthusiasm. There was nothing to choose between the radical savants and the enthusiast mob. Nor was there much difference between the wilder shores of philosophical materialism and the old doctrines of spirits, witches, and ghosts. New enlightenment was but old illumination. The enthusiastic visions of the philosophers helped this set of claims: it was not always easy to distinguish the language of the rational dissenters from that of their Methodist enemies. Priestley's Yorkshire bred both. His work on "the scriptures, Ecclesiastical History and the Theory of the Human Mind" was often couched in the metaphor of light and applied directly to

[11] John Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, 3d ed. (London, 1798), 229-233. For Robison and the Laplacians, see J. B. Morrell, "Professors Robison and Playfair and the Theophobia Gallica: Natural Philosophy, Religion and Politics in Edinburgh, 1789-1815," Notes and Records of the Royal Society 26 (1971): 43-64.

radical secular change. Thus in his learned dissertation of 1782 on the scriptural foundations of unitarianism, Priestley made use of an obviously visionary language: "happy are those who contribute to diffuse the pure light of this everlasting gospel."[12]

In his own Everlasting Gospel of 1818 Blake drew a sharp distinction between his vision of spirituality and that of the rational unitarians: "Like dr. Priestly [sic] & Bacon & Newton—Poor Spiritual Knowledge is not worth a button!" But in the 1790s it was easy to see the connections between the proclamations of the empire of reason and the older forms of spiritual knowledge. In France and Britain astrology, mesmerism, alchemy, the Eleusinian mysteries, electrotherapy, and prophecy all became linked to the radical cause. If, as Robert Darnton has suggested, mesmerism marked the end of the Enlightenment in France, mesmerists found it possible to trace respectable natural-philosophical ancestry for their doctrines among the views on active matter developed by eighteenth-century electrical and pneumatic experimenters. But Paris physicians found it more plausible to compare Mesmer with occultists such as Paracelsus, Fludd, Greatrakes, and Bruno. Roy Porter is right to point out that the disciples of animal magnetism proffered materialist stories to explain their successes while the established academicians referred Mesmer's cures to psychosomatic possessions in order to explain them away.[13] In the 1790s, Britain witnessed a wide range of such radical

[12] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1791; London: Dent, 1910), 155; Joseph Priestley, Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated (London, 1777), xvi; Rutt, 5:4. For the anti-Jacobin reaction, see M. D. George, "Political Propaganda, 1793-1815: Gillray and Canning," History, n.s., 31 (1946): 66-68 (on the Anti-Jacobin ); Norton Gar-tinkle, "Science and Religion in England, 1790-1800: The Critical Response to the Work of Erasmus Darwin," Journal of the History of Ideas 16 (1955): 276-288; Goodwin, Friends of Liberty, chaps. 4, 6, 10.

[13] Blake, Complete Writings, 752; for mystical sciences and radical politics in Britain, see Clarke Garrett, Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and Britain (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975); J. F. C. Harrison, The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780-1850 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979). For mesmerism, see Robert Darnton, Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968); Roy Porter, "Under the Influence: Mesmerism in England," History Today 35 (September 1985): 22-29. Mesmer connects his views with natural philosophy in "Mémoire sur ses découvertes" (1799), in Mesmerism, ed. George J. Bloch (Los Altos, Calif.: Kauffmann, 1980), 118-121. For English mesmerism, see Roger Cooter, "The History of Mesmerism in England," in Mesmer und die Geschichte des Mesmerismus, ed. Heinz Schott (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1985), 152-162. For the psychosomatic explanation of mesmeric cures, see F. Azouvi, "Sens et fonction épistémologique de la critique du magnétisme animal par les Académies," Revue de l'histoire des sciences 29 (1976): 123-142. For Mesmer and Paracelsians, see J. J. Paulet, L'antimagnétisme (Paris, 1784). For the "Eleusinian mysteries," see Erasmus Darwin, The Temple of Nature (London, 1803), 13n. Compare Herbert Loventhal, In the Shadow of the Enlightenment: Occultism. and Renaissance Science in 18th Century America (New York: New York University Press, 1976).

and mystical activity. Conservatives documented groups such as the "ancient deists" at Hoxton, a center of London dissent, who combined the views of "infidel mystics" with French politics and occult sciences. The activities of the popular prophets such as Joanna Southcott and Richard Brothers were also greeted with a mixture of amusement and alarm. The work of the inspired attracted considerable support in regions such as those where dissent was strong. The events of the 1790s suggested at least three targets for conservative comment: millenarians and prophets who foresaw an imminent change in the civil and moral order; radical physicians who appealed to a materialist knowledge of the mind and the soul in order to change humanity; and rationalist metaphysicians who applied the principles of their philosophy to the reconstruction of the state. Priestley and his allies, such as Theophilus Lindsey and Richard Price, talked in explicitly millenarian terms: "I have little doubt," Priestley announced in 1798, "but that the great prophecies relating to the permanent and happy state of the world, are in the way of fulfilment." These hopes were backed by a specifically materialist account of the capacities of the human mind. As fashionable physicians and radical natural philosophers, both Thomas Beddoes and Erasmus Darwin attracted particular hostility from the conservatives. As Maureen McNeil has shown, Darwin was attacked in the same way as his ally Joseph Priestley for "constantly blending and confounding together the two distinct sciences of matter and mind." Writers in the Anti-Jacobin made fun of these visions. In their satire of 1798 on Darwin's Loves of the Plants, Canning and Frere paraphrased the radicals' view of the progress of humanity. "We have risen from a level with the cabbages of the field to our present comparatively intelligent and dignified state of existence, by the mere exertion of our own energies." The future prospects were ludicrously glorious and based on a risible natural philosophy: the wits claimed that the radicals hoped to raise man "to a rank in which he would be, as it were, all MIND; would enjoy unclouded perspicacity and perpetual vitality; feed on oxygene, and never die, but by his own consent. "[14]

[14] For the "ancient deists," see William Hamilton Reid, The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies in This Metropolis (London, 1800), 91; for prophecy, see Harrison, The Second Coming, 57-134; D. M. Valenze, "Prophecy and Popular Literature in Eighteenth-Century England," Journal of Ecclesiastical History 29 (1978): 75-92; Clarke Garrett, "Swedenborg and the Mystical Enlightenment in Late Eighteenth-Century England," Journal of the History of Ideas 45 (1984): 67-81. For popular dissent, see E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1968), chap. 2. For Priestley and prophecy, see Priestley to Lindsey, 1 November 1798, in Rutt, 2:410; Jack Fruchtman, Jr., The Apocalyptic Polities of Richard Price and Joseph Priestley (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1983), 8-45, 81-93. For attacks on Darwin, see Edinburgh Review 2 (1803):449, cited in Maureen McNeil, "The Scientific Muse: The Poetry of Erasmus Darwin," in Languages of Nature: Critical Essays on Science and Literature, ed. Ludmilla Jordanova (London: Free Association Books, 1986), 159-203 at 172; Charles Edmonds, ed., Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1890), 147 (April 1798).

The apostles of reason often seemed to be tools of unreason. Bentham recognized this: in the 1770s he already accepted that "the world is persuaded, not without some colour of reason, that all reformers and system-mongers are mad.... I dreamt t'other night that I was a founder of a sect; of course, a personage of great sanctity and importance: it was called the sect of the Utilitarians." The language of the sects was a powerful tool for the reformers. It became a devastating weakness when attacked in the 1790s. Burke's immediate target, Richard Price, preached that "every degree of illumination which we can communicate must do the greatest good. It helps prepare the minds of men for the recovery of their rights and hasten the overthrow of priestcraft and tyranny." Their opponents identified the social habits of the reformers with their mental constitution. Their covert associations of like-minded intellectuals allegedly fostered the strategy of an insinuation of the false and dangerous beliefs of materialist metaphysics and silly natural philosophy. Thus derangement became dangerous when it seized power. In 1796 Burke picked on the geometricians and chemists whose "dispositions" made them "worse than indifferent about those feelings and habitudes which are the support of the moral world. Ambition is come upon them suddenly; they are intoxicated with it." Sometimes, as in the satires directed against Beddoes's use of gaseous medicines in Bristol in the 1790s and the "pneumatic revelries" of his friends, the "intoxication" became literal. The mental habits of these men were viewed as the cause of their threatening policy. Approaching dangerously, if characteristically, the excessive fury which he condemned, Burke said that "the heart of a thoroughbred metaphysician comes nearer to the cold malignity of a wicked spirit than the frailty and passion of man. It is like that of the Principle of Evil himself, incorporeal, pure, unmixed, dephlegmated, defecated evil." Accusations of insanity provided much of the language of the polemic on the Reflections on the Revolution in France. Both Burke and Robison, who was well known for his opium habit, might also be shown to be mentally disturbed. Bentham was irate that "the National Assembly of France has been charged with madness for pulling down

establishment," and he condemned Burke's book as the "frantic exclamation" of a "mad man, than whom none perhaps was ever more mischievous."[15]

Burke was only the most effective of those who argued for the devastating effects of the connection between the associations formed by the reforming philosophers and the political havoc they had wrought. The natural philosophy of the reformers provided fruitful targets for wit: in a famous figure, Burke compared "the spirit of liberty in action" to "the wild gas , the fixed air": "but we ought to suspend our judgement until the first effervescence is a little subsided, till the liquor is cleared, and until we see something deeper than the agitation of a troubled and frothy surface." The most obvious—and most humorous—connection which the anti-Jacobins spotted between this natural philosophy and the politics of the Terror was the endorsement of materialism. Robison commented at some length on Priestley's use of David Hartley's theory of association and aethereal vibrations in the mind. "Dr. Priestley again deduces all intelligence from elastic undulations, and will probably think, that his own great discoveries have been the quiverings of some fiery marsh miasma. " From here it was but a short step to the dangerous lunacies of the intellectuals. Their overestimate of their own mental capacity was accompanied by the bestialization of humanity. "They find themselves possessed of faculties which enable them to speculate and to discover; and they find that the operation of those faculties is quite unlike the things which they contemplate by their means." The consequence was reformist arrogance and corrupted politics: "they feel a satisfaction in this distinction."[16] An insistence on the material basis of mind seemed to be leading to the creation of a new elite of intellectuals, a new breed of "saints." The resonance with the "Good Old Cause" was deliberate. The admirers of reforms also helped themselves to this hagiographic language. The connections between the English philosophers, such as the Bowood group, and their French colleagues were

[15] For Bentham on the sect of utilitarians, see David Baumgardt, Bentham and the Ethics of Today (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), appendix 1, printing Bentham MSS, University College London, 169.79. For Price, Richard Price, Discourse on the Love of Our Country (London, 1789), 15. For Burke's attack, Edmund Burke, Letter to a Noble Lord (1796), in Burke's Politics, ed. R. Hoffman and P. Levack (New York: Columbia University Press, 1949), 532-534. For attacks on Beddoes, see Dorothy Stansfield, Thomas Beddoes (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1984), chap. 7; T. H. Levere, "Dr. Thomas Beddoes: Science and Medicine in Politics and Society," British Journal for the History of Science 17 (1984): 187-204. For Bentham on Burke and the Revolution, see Bowring, 2:404-405; 4:338·

[16] Burke, Reflections on the Revolution, 6; Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy, 429-430.

often figured in these terms. The Girondin leader J. P. Brissot, guillotined in 1793 and later satirized as a vindictive ghost in the Anti-Jacobin, saw Bentham as a modern saint, one of "those rare beings, whom Heaven sometimes sends down upon earth as a consolation for woes, who, in the form of imperfect man, possess a heavenly spirit."[17]

The attack on the new "saints" was the basis of what amounted to a critique of the new social function of the intellectual. The reformers' associations were held to be the principal site of subversive philosophy and politics. Burke named these associations in the Reflections and then defended his decision to do so: "I intend no controversy with Dr. Price, or Lord Shelburne, or any other of their set," he claimed. But his purpose was to destroy their credentials as disinterested men of knowledge: "I mean to do my best to expose them to the hatred, ridicule and contempt of the whole world; as I always shall expose such calumniators, hypocrites, sowers of sedition and approvers of murder and all its triumphs." This was the sense given to the term "Illuminati." The Masonic conspiracies spread through Europe provided the appropriate model with which to analyze the behavior of the English reformers. "The detestable doctrines of Illuminatism have been preached among us," Robison claimed, and named both Priestley and Price as examples. Robison implied that there was a significant contrast with the proper form of natural philosophy developed in such organizations as the Royal Society of Edinburgh, of which he had been Secretary. It was argued that the materialist doctrines of the illuminated philosophers provided a model of the mind which only invited the habit of conspiracy. They had made morality a problem for subtle metaphysics, when it was really a question of public orthodoxy and private sentiment. So their revolution followed from a false natural philosophy. "They have much, but bad, metaphysics; much, but bad, geometry; much, but false, proportionate arithmetic," Burke wrote against the philosophes. Political subversion was the same as natural disorder. When Burke turned his gaze upon the French dissolution of the monasteries, he explicitly compared bad policy with bad cosmology: "to destroy any power growing wild from the rank productive force of the human mind, is tantamount, in the moral world, to the destruction of the apparently active properties of bodies in the material." When he explained his own horror at the deposition of the king, he pointed to the natural constitution of the mind: "we behold such disasters in the moral, as we should behold a miracle, in the physical, order of things." Any group of intellectuals which

[17] Bowling, 10:192; Edmonds, Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, 165-168 (April 1798).

claimed to be able to understand, reform, and manage these mental faculties was at best insanely optimistic about the capacity of metaphysics and, at worse, destructive of those natural sentiments which actually governed proper moral life.[18]

The anti-Jacobin assault repeatedly contrasted the rational technology of mental management proposed by the radicals with a proper interpretation of the established powers of the mind. The radicals were compared with wily impresarios, or with cunning magicians, or with dissolute gamblers. Burke sought an aesthetics of the state: "to make us love our country, our country ought to be lovely." The machinations of the materialists would be incompetent because they could not hope to understand or to force these aesthetic judgments. The Jacobin theater of politics was a world of illusion and crude spectacle. Their philosophical supporters were no better than wizards, making use of "poisonous weeds and wild incantations." It was scarcely surprising that deluded chemists and natural philosophers found such allies congenial. In the 1770s, Burke had contacts with Priestley's natural philosophy, but by the 1790s he viewed this work as a dangerous error. John Robison was a leader of the British resistance to the new-fangled French chemistry, but Priestley was held to be guilty of overconfidence in his mere hypotheses. Newton's aether was wrongly treated by the materialists as having the certainty of Euclid. It was easy to connect materialist natural philosophy with conjuring. The Anti-Jacobin imagined a pneumatic chemist whose "skin, by magical means, has acquired an indefinite power of expansion, as well as that of assimilating to itself all the azote of the air . . . an immense quantity which, in our present unimproved and uneconomical mode of breathing, is quite thrown away."[19] This was a well-aimed barb, for the

[18] Burke to Philip Francis, 20 February 1790, Letters of Edmund Burke, ed. Harold Laski (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1922), 283-284; Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy, 481; Burke, Reflections on the Revolution, 178, 154, 78.

[19] Burke, Reflections on the Revolution, 75, 93; Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy, 484; Edmonds, Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, 160. For Burke's attack on Jacobin histrionics, see P. H. Melvin, "Burke on Theatricality and Revolution," Journal of the History of Ideas 36 (1975): 447-468 and the interesting comments in UEA English Studies Group, "Strategies for Representing Revolution," in 1789: Reading Writing Revolution, ed. Francis Barker et al. (Colchester: University of Essex, 1982), 81-109. For Burke and Priestley's pneumatics, see Priestley to Burke, 11 December 1782, in Schofield, Scientific Autobiography of Priestley, 216; for Robison and French chemistry, see J. R. R. Christie, "Joseph Black and John Robison," in Joseph Black 1728-1799, ed. A. D. C. Simpson (Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Museum, 1982), 47-52. For Jacobin and anti-Jacobin natural philosophy, see W. L. Scott, "Impact of the French Revolution on English Science," in Mélanges Alexandre Koyre, ed. R. Taton, 2 vols. (Paris: Hermann, 1964), 2:475-495.

reformers did base their authority on their understanding of the atmosphere and the economy of powers that circulated through it. The joke turned sour when these conjurers claimed to be able to reconstruct society. Their charms and spells deceived, and did not comprehend, the moral faculties. Burke argued that "on the principles of this mechanic philosophy, our institutions can never be embodied, if I may use the expression, in persons; so as to create in us love, veneration, admiration or attachment." The materialists did not know these passions and so were foolish to rationalize about them: they knew of "nothing that relates to the concerns, the actions, the passions, the interests of men." This attack applied both to the general possibility of a rationalist metaphysics of the moral order and to the intimate details of political reform. Since the state was a "body politic," a failure to understand the "true genius and character" of any natural body would lead to a failure to understand proper politics. Hence the disasters of the new French financial regime: revenue was "the sphere of every active virtue" of "all great qualities of the mind which operate in public." Mechanistic policy made civil philosophy into a branch of gambling. A principal consequence of the Revolutionary settlement had been to hand over control to the few urban intellectuals who would "understand the game." "The many must be the dupes of the few who conduct the machine of these speculations."[20]

The controversies of the 1790s used the civic humanist language of corruption and virtue and turned it back upon the radical reformers. Burke pointed out that the new intellectual regime privileged the politics of "combination and arrangement (the sole way of procuring and exerting influence)." He argued that "the deceitful dreams and visions of the equality and rights of men" would end in "an ignoble oligarchy" form of coteries of roofless men, recognizable only for their self-styled expertise in management and manipulation. The habit of association was a natural consequence of the reformers' intellectual position. Robison listed the "Corresponding - Affiliated - Provincial - Rescript - Convention - Reading Societies" as British manifestations of this habit. Those linked with politically interested patrons, such as Shelburne or the radical Whig lord and natural philosopher Charles Stanhope, and with groups and clubs of inquirers, such as the Bowood group or the

[20] Burke, Reflections on the Revolution, 75, 178, 223, 190. Compare R. W. Kilcup, "Reason and the Basis of Morality in Burke," Journal of the History of Philosophy 17 (1979): 271-284.

Lunar Society, were obvious targets for this critique. The anti-Jacobins found it fitting that the Lunar Society has been destroyed by the Birmingham mob for whom Priestley's friends claimed to act as spokesmen. "Peace to such Reasoners!... Priestley's a Saint," chortled the Anti-Jacobin. The attack upon intellectual associations extended to a critique of the "enlightenment" they sought. This light was derived from the wrong use of the inquiring mind. "We see that it is a natural source of disturbance and revolution," wrote Robison. The paradox that the philosophical societies of virtuous men bred nothing but corruption was matched by the paradox that enlightenment bred disorder. "Illumination turns out to be worse than darkness."[21]

BOWOOD AND THE REFORMERS' DREAM

Conservatives tried to make enlightenment look like illumination. They saw the social groupings of the reforming intellectuals as the wrong kind of organization for men of knowledge. They also claimed that the true purposes of the reformers were now revealed. Controversies within the radical camp—as for example Priestley's violent attack on the infidelity of Volney's Ruines in 1797—were treated as signs of the incoherence of the Jacobin cause. But philosophers such as Bentham and Priestley had very specific proposals for reform. They presented the work performed since the 1770s as an ideal of the reformers' task. One such ideal was provided by the work in natural and moral philosophy which Priestley pursued with his colleagues at Bowood and elsewhere. The patronage provided by Shelburne for these philosophers was a key resource for their projects. The accounts of this relationship provided by Priestley and Bentham are extremely revealing, because in describing their relationship with their noble master they also described the function which they claimed to discharge. The idealization of this relationship is an important contrast with the harsh realities of late-eighteenth-century patronage and its vicissitudes. There is an interesting tension between the tortuous paths followed by Priestley and Bentham as they sought backing from their potential allies, and the utopian models which they presented of how this support might change society. Hence Bentham's extraordinary presentation of the contrast between himself, "an unseated, unofficed, unconnected, insulated individual," whose "blameless life" had been entirely devoted to the promotion of the Panopticon, and

[21] Burke, Reflections on the Revolution, 190-192; Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy, 479, 431; Edmonds, Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, 278 (July 1798).

his enemies, such as George III: "Imagine how he hated me.... But for all the paupers in the country, as well as all the prisoners in the country, would have been in my hands." This tension demonstrates two important features of intellectual life at this period: First, the role of medical manager, equipped with the knowledge of pneumatic chemistry and the right principles of the philosophy of mind, provided the appropriate model for reform. Second, a complex network of political and theological aims was centered on this search for patronage and provided the reformers with their interests and goals.[22]

Bentham presented his contact with Shelburne in extraordinarily messianic terms. By the end of the 1770s, Shelburne was one of the leaders of a discredited and divided opposition to the American war and to North's Tory administration. Bentham was an impoverished legal writer, author of the important Fragment on Government (1776), and at this stage by no means sympathetic to the rebels' cause. His text on the law was a radical critique of the great jurist William Blackstone, whom Bentham had heard lecture on the laws of England at Oxford. Bentham proceeded to the M.A. there in 1767 and spent the intervening years working on his commentaries on Blackstone and on other essays on legal reform, including texts on prison reform and criminal punishment. His friends at Slaughter's Club and the London coffeehouses included chemists and physicians, such as George Fordyce, Jan Ingenhousz, Felice Fontana, and the Austrian F. X. Schwediauer, who were also working closely with Priestley during this period. In spring 1780 Bentham collaborated with Schwediauer on a translation of the Usefulness of Chemistry by the great Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman. Yet his principal labors centered on what he baptized his "Code" and his "Punishments, " of which the Fragment was a highly condensed and preliminary extract. Bentham's remarkable memoir recalled that it was this book which prompted Shelburne to seek him out at Lincoln's Inn. "I felt as men used to feel when Angels used to visit them." In another

[22] For Priestley and Volney, see Joseph Priestley, Observations on the Increase of Infidelity (Philadelphia, 1797) and Brian Rigby, "Volney's Rationalist Apocalypse," in Barker, 1789, 22-37. For Bentham's presentation of himself, see Bowring, 5:160-161 and 10:212, discussed in Himmelfarb, "The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham," 70-71. For problems of patronage, see Michael Foss, The Age of Patronage: The Arts in England, 1660-1750 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1971), chap. 7; John Brewer, "Commercialization in Politics," in Neil McKendrick et al., The Birth of a Consumer Society (London: Hutchinson, 1983), 197-262; W. A. Speck, "Politicians, Peers and Publication by Subscription, 1700-1750," in Books and Their Readers in Eighteenth-Century England, ed. Isabel Rivers (New York: St. Martin's, 1982), 47-68; for an excellent example of Shelburne's patronage, see Dorothy Stroud, Capability Brown (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), 90-92.

reverie, Bentham used explicitly apocalyptic imagery: "There came out to me a good man named Ld. S. and he said unto me, what shall I do to be saved? I yearn to save the nation. I said unto him—take up my book and follow me.... We had not travelled far before we saw a woman named Britannia lying by the waterside all in rags with a sleeping lion at her feet: she looked very pale, and upon inquiring we found she had an issue of blood upon her for many years. She started up fresher farther and more alive than ever; the lion wagged his tail and fawned upon us like a spaniel."[23]

Bentham's dream about Shelburne, though recollected in tranquillity, transfigured the actual relations with patronage and the proposals for reform which he offered in his juridical work. Connection and influence dominated the political strategies of the 1770s. To understand the role which the reformers made for themselves in this jungle of deference and obligation, it is necessary to describe the political programs they espoused and the model they chose for their campaigns. In a public culture that spoke the language of "candour" and abhorred "interest," patronage was always a fraught relationship. Burke seized upon these resources in his anti-Jacobin polemic against the Bowood group in the 1790s, risking the charge of hypocrisy as he did so. In 1771, Priestley was apparently barred from serving with Cook and Banks on a voyage to the South Seas by "Dr. Blackstone and his friends in the Board of longitude," allegedly on the grounds of his heretical theology and animosity against the government lawyers. Priestley wrote sarcastically that the ministry would support "a high churchman or a known atheist, tho' his reputation for philosophy or virtue should stand very low." The sarcasm implied an accurate assessment of the standards of public patronage. For example: Shelburne was struck by Bentham's apparent disinterest when he approached him in 1780, though Bentham was more prosaic: "Ld. S. puts in members," he told his brother. Another possible supporter Bentham tried was the Empress Catherine of Rus-

[23] For Bentham's life in the 1770s, see Everett, Education of Bentham, 57-70; Mack, Bentham, 335-351. For Blackstone at Oxford, see Bowring, 10:45. For connections at Slaughter's, see Bowring, 10:133 and Bentham to John Lind, [?] 12 June 1776, The Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham, ed. T. L. S. Sprigge (London: Athlone Press, 1968), 1:328; Bentham to Samuel Bentham, 6 March 1779, ibid. 2:246-247; F. W. Gibbs, Joseph Priestley (London: Nelson, 1965), 94-98. For collaboration with Schwediauer, see Bertel Linder and W. A. Smeaton, "Schwediauer, Bentham and Beddoes: Translators of Bergman and Scheele," Annals of Science 24 (1968): 259-273. For Bentham's reveries about Shelburne, see Mack, Bentham, 370-372; J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart, eds., Comments on the Commentaries and the Fragment on Government (London: Athlone Press, 1977), 523-526; Norris, Shelburne and Reform, 141-143.

sia. Catherine had hired several British experts, including Robison, who worked at Kronstadt as mathematics professor between 1772 and 1774. One function that Bentham made his chemist friends serve was to get better contacts with Russia. He persuaded Schwediauer to translate the introduction to the Code, later to appear as An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. During early 1779, Schwediauer and Priestley helped Bentham contact Shelburne through a junior treasury lord, and keen mathematician, Francis Maseres. When Bentham's brother went to St. Petersburg in August, Bentham was to pose as an expert political and technical journalist, submitting information to Shelburne for his consideration. But the crucial meeting was necessarily delayed, because Bentham felt that Shelburne should see the Code before they met, and because "my letters I was afraid had gone rather too far on the side of humility." The role play was crucial: Bentham had to present himself as the right kind of expert in order to set up the appropriate relationship with his new master.[24]

Priestley provided Bentham with an avenue—he also made his own vocation through his contacts with Bowood. The relation between Priestley's political strategy in the 1770s and his contacts with Shelburne was particularly important here. Priestley was a leader of the group of "rational dissenters" who sought the emancipation of dissent from legal disabilities. Allies included both Price and Theophilus Lindsey. Rational dissent connected the familiar civic humanist critique of the established institutions of civil and ecclesiastical corruption with a program based on the progressive unmasking of "prejudice" and the establishment of true philosophy through putative matters of fact about matter and spirit. Such matters of fact were best exemplified in the research on pneumatic chemistry which Priestley launched in Leeds just before his departure for Wiltshire. The label "rational dissent" was first coined by Priestley and his colleagues in texts such as their 1769 attack on Blackstone, an inspiration for Bentham's Commentaries. Bentham was impressed by the

[24] For Burke and patronage, see Albert Goodwin, "The Political Genesis of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, " Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 50 (1968): 336-364. For Priestley and the South Seas voyage, see Priestley to William Eden, 4 December and 10 December 1771, Priestley to Joseph Banks, 10 December 1771, in Schofield, Scientific Autobiography of Priestley, 95-98; David Mackay, In the Wake of Cook: Exploration, Science and Empire, 1780-1801 (London: Croom Helm, 1985), 3-27. For Shelburne and Bentham, see Bowring, 10:225; Bentham to Samuel Bentham, 25-26 September 1775, including Priestley to Bentham, 23 August 1775, in Correspondence of Bentham 1:265; Bentham to Samuel Bentham, 16 May 1779, ibid. 2:257-258; Shelburne to Bentham, 27 July 1780, ibid. 2:471; Bentham to Samuel Bentham, 6 August 1780, ibid. 2:480.

"well-applied correction" which the rational dissenters had given to Blackstone's "holy zeal" for the established religion. He also judged Blackstone's publications by the standards demanded from "demonstrators" in experimental natural philosophy. Most importantly, the rational dissenters' campaigns provided the immediate context both for Priestley's initial links with the Earl, and for his subsequent formulation of a combined program of philosophical materialism, pneumatic chemistry, and political reform.[25]

Rational dissenters initially sought to speak the language of "candour" in their appeals to established power and their relationships with their patrons. Priestley told Price that "all that candour requires is that we never impute to our adversary a bad intention or a design to mislead, and also that we admit his general good understanding, though liable to be misled by unperceived biases and prejudices from the influence of which the wisest and best of men are not exempt." So this language allowed the rational dissenters to describe the way their political strategy should be structured and the way philosophical debate should be conducted. It provided a contrast with the views of the allies of the ministerial interest. An American Tory, writing in 1783 in the Gentleman's Magazine, helped himself to the talk of mind and body to analyze "Lord Shelburne's connection with the Dissenters." He suggested that the dissenters had been "carnalized" by Shelburne, rather than the "Peer spiritualized" by them. "Seeing more fire and spirit in Dr. Priestley's Disquisition on civil liberty," Shelburne had then offered a place at Bowood to the Doctor. In fact, it was to the "wisest and best of men," such as Shelburne, that Priestley and his allies began their appeal from 1769, following the return of John Wilkes at the Middlesex election. Shelburne's support was important in 1772, when the rational dissenters mounted an unsuccessful appeal for the extension of the Toleration Act. The defeat of this so-called Feathers Tavern Petition was immediately interpreted by Priestley and Lindsey in prophetic, if not millenarian, terms, and they used the more eschatological passages in David Hartley's Observations on Man to understand their own troubles: "to me everything looks like the approach of that dismal catastrophe described, I may say

[25] For rational dissent, see J. G. McEvoy and J. E. McGuire, "God and Nature: Priestley's Way of Rational Dissent," Historical Studies in Physical Science 6 (1975): 325-404; Priestley on "those of us who are called Rational Dissenters," in Rutt, 1:349-357; Michael Watts, The Dissenters from the Reformation to the French Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 464-478. For Bentham on Blackstone, see Jeremy Bentham, A Fragment on Government (1776), ed. F. C. Montague (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931), 102-103n, 117n.

predicted, by Dr. Hartley in the conclusion of his essay and I shall be looking for the downfall of Church and state together." It was during this crisis that Priestley got his place at Shelburne's house and inaugurated his new set of philosophical and chemical researches.[26]

Priestley's introduction to Shelburne in 1772-1773 won him a salary increased from the £100 he earned as a minister at Leeds to £250 as Shelburne's librarian and traveling companion. It was preceded by anguished debate in London and Leeds. In September 1772, Franklin sent Price and Priestley a "moral and prudential calculus" that encouraged the move to Wiltshire. Franklin, Priestley, and Price were important members of the group of self-styled "Honest Whigs," who moved to the London Coffee House in 1772 and combined natural-philosophical and reformist political interests through this decade. Others included John Pringle, president of the Royal Society and a pneumatic physician who was an enthusiastic admirer of Priestley's chemistry. By 1773, many of Priestley's allies, including Lindsey, had left the established church and joined the rational dissenters at Essex Street Chapel in London, set up as a propaganda center for Shelburne's allies and to foment emancipation. Priestley worked actively for Shelburne's political maneuvers and gained the support of men such as the leading reformist Whig George Savile, a Yorkshire M.P. who was now acting as patron for the great natural philosopher and clergyman John Michell. Micheil and Priestley had already collaborated with Savile in Leeds, both on technical projects and on joint research on the active powers of matter, the materiality of the soul, and the properties of light. During 1773-1774, Priestley led the dissenters to abandon the slogan of "candour," which involved support merely for relief from the Test, and encouraged a move to an analysis of humanity, which the whole of established civil philosophy was called in question. Catholic emancipation and support for the American cause became part of their campaigns. A reconstructed account of human nature and the sources of prejudice and opposition to "rational evidence"

[26] For "candour," see Joseph Priestley, A Free Discussion of the Doctrines of Materialism and Philosophical Necessity (London, 1778), xxx; R. B. Barlow, Citizenship and Conscience (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962), 171-220. For the Tory attack, see "An Account of the Origin and Dissolution of Ld. Shelburne's Connection with the Dissenters," Gentleman's Magazine 53 (January 1783): 22-23. For the theory of civil liberty, see Joseph Priestley, Essay on the First Principles of Government (London, 1768), 10; A. H. Lincoln, Some Political and Social Ideas of English Dissent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1938), 160. For Priestley and Lindsey on the defeat of the petition, see Priestley to Lindsey, 23 August 1771, in Rutt, 1:146; Fruchtman, Apocalyptic Polities of Price and Priestley, 40.

would allow the dissenters to "cancel the obnoxious name of Christians, and ask for the common rights of humanity."[27]

Thus the conjuncture in which Priestley moved to Bowood provided him with all the resources he needed. His work in natural philosophy with Michell, Price, Franklin, Pringle, and the members of the Bath Philosophical Society, situated near his new home, provided him with important contacts. Shelburne gave him £40 a year for equipment and materials. The campaign of rational dissent provided him with an epistemology and a new and urgent need for a revised analysis of the mind. His targets included the Common Sense philosophers and the apparently irreligious skeptics in France and Scotland. The close links between Bowood and the philosophes, together with Priestley's journeys to Paris on Shelburne's business, confirmed his views of the important tasks of the true philosophy. This was a watershed in Priestley's philosophical and religious views. "My own sentiments are very different from what they used to be," he wrote in 1778. He dated his unitarian views in religion from the moment he went to Leeds in 1769, and he dated his "philosophical materialism" to the mid-1770s, first made public in the stream of works on matter theory and religion produced in London and Wiltshire. His productivity was extraordinary: he published a long series of works on pneumatic chemistry, a series of metaphysical texts, of which the Disquisitions on Matter and Spirit (1777) was the most important, and a detailed series of polemics, including amicable debates with Richard Price on materialism and determinism. All this work involved a deliberate construction of what Priestley saw as the right role the natural philosopher should serve. Pneumatics, as an account of the activity of matter and the vitality of the airs, and pneumatology, a philosophical account of the mind and the soul, were the principal concerns of this project.[28]

[27] On the offer of a place at Bowood, see Franklin to Priestley, 19 September 1772 and to Price, 28 September 1772, in Correspondence of Price 1:138-139. For the "Honest Whigs," see V. W. Crane, "The Club of Honest Whigs: Friends of Science and Liberty," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 23(1966): 210-233; for work with Michell and Savile, see Norris, Shelburne and Reform, 100; Gibbs, Joseph Priestley, 91-93; Priestley to Price, 23 November 1771, in Schofield, Scientific Autobiography of Priestley, 93-94. For the "appeal to humanity," see Barlow, Citizenship and Conscience, 190, 221-271; Priestley (1773) in Rutt, 23:443-450.

[28] For support by Shelburne, see Schofield, Scientific Autobiography of Priestley, 139-141, and for work at Bowood see Priestley to Caleb Rotheram, 31 May 1775, ibid., 146; for the change in his philosophy and theology, see Priestley to Caleb Rotheram, April 1778, in Rutt, 1:315; Joseph Priestley, Letters to Dr Horsley (Birmingham, 1783), iii-iv. For an analysis of Priestley's finances, see M. P. Crosland, "A Practical Perspective on Joseph Priestley as a Natural Philosopher," British Journal for the History of Science 16 (1983): 223-237.

Bentham was well aware of this work: he had already read Priestley's Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768); in August 1767 he also received an abstract of the History of Electricity from his fellow attorney Richard Clark. In later life he used Priestley's edition of Hartley in his own psychological research, and he praised Priestley's attack on the Scottish philosophers. In January 1774 he began a thorough analysis of the publications on pneumatic chemistry and sent his brother copies of successive versions of the Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. In his "Essence of Priestley," as Bentham called it, he read the full statement of a progressive and historically sensitive account of the course of natural philosophy and the role the natural philosopher should play. The summer after he completed his "Essence," he contacted Priestley directly. The opening of Bentham's Fragment on Government, which he published the following year, spelled out Priestley's vision, paraphrasing the opening of the Experiments and Observations on pneumatics. It must have impressed Shelburne with its bold indication of the work that natural philosophy could perform:

The age we live in is a busy age; in which knowledge is rapidly advancing towards perfection. In the natural world, in particular, every thing teems with discovery and with improvement. The most distant and recondite regions of the earth traversed and explored—the all-vivifying and subtle element of the air so recently analyzed and made known to us—are striking evidences, were all others wanting, of this pleasing truth.[29]

Just as in the case of his relationship with Shelburne, so here too Bentham provided a dreamlike account of his first encounter with Priestley's work. Much later in his life, it was important for Bentham to display his debt to the utilitarianism of rational dissent and to play down

[29] Bentham, Fragment on Government, 93; for the use of Hartley, see Bentham, Intro duction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 124n; for the praise of Priestley's attack on the Common Sense philosophy, see Alan Sell, "Priestley's Polemic against Reid," Price-Priestley Newsletter 3 (1979): 41-52; Bhikhu Parekh, ed., Bentham's Political Thought (London: Croom Helm, 1973), 152n: "Another says he has a sense . . . that pronounces what is right and wrong. This is the way that . . . the triumvirate of doctors lately slaughtered, not to say butchered, by Dr Priestly [sic] make laws of nature" (1776). For Priestley's attack on Hume, see Rutt, 4:398 and Richard H. Popkin, "Joseph Priestley's Criticisms of David Hume's Philosophy," Journal of tat History of Philosophy 15 (1977): 437-447. For Bentham and Priestley's pneumatics, see Bentham to Richard Clark, 5 August 1767, Correspondence of Bentham 1:119; Bentham to Samuel Bentham, 28 January 1774, July 1775, 20 July 1774, ibid. 1:176, 186, 189; Bentham to Priestley, 1774, ibid. 1:208.

the marked division between his own views of the rights of humanity and those preached at Essex Street. Bentham recalled reading Priestley's remarkable Essay on the First Principles of Government in a coffeehouse in Oxford in 1768. There he read the sentiment that the "great standard" of civil society was "the good and happiness . . . of the majority of the members of any state." "At the sight of it he cried out, as it were in an inward ecstasy like Archimedes on the discovery of the fundamental principles of Hydrostatics, Eureka. "[30] Despite Bentham's claim that he "purloined" the happiness principle from this book, he was also able to assemble a lengthy litany of key figures for his conception of the doctrines of utilitarianism. He told d'Alembert in spring 1778 that it was Helvetius who had provided him with the important hint. Debates on influence here are inevitably sterile and obviously reflect Bentham's capacity for the ingenious reconstruction of his own vocation. In the Fragment Bentham wrote of the English edition of Beccaria's work on penology, On Crimes and Punishments, which contained the phrase "the greatest happiness of the greatest number." He used just the terms he would later use to describe Shelburne. Bentham claimed that Beccaria was "received by the intelligent as an Angel from heaven would be by the faithful." Links with the philosophes were crucial for Bentham's development, and they were energetically pursued via Romilly and Mirabeau when he reached Bowood in the 1780s.[31] The "fundamental principles" which Bentham gained from Priestley involved a path to political power and a role model for the reformer, that of the pneumatic chemist and devotee of moral progress through technical change. Bentham shared Priestley's views on the character of the corrupt enemy and the false philosophy they peddled. In his draft preface for the Bergman translation, Bentham recalled his own Oxford career as a picture of the wrong kind of natural philosophy. Even though he heard mechanics lectures from Nathaniel Bliss, "I learnt nothing of the air I breathed in, except that the mischief it was apt to do was owing to the spitefulness

[30] For Bentham's story about reading Priestley's Essay, see draft of 1829, Bentham MSS, University College London, 13.360, printed in Amnon Goldworth, ed., Deontology, Together with A Table of the Springs of Action and the Article on Utilitarianism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983), 291-292, compared with Bentham, Fragment on Government, 34. For a very useful criticism of this story, see Margaret Canovan, "The un-Benthamite Utilitarianism of Joseph Priestley," Journal of the History of Ideas 45 (1984): 435-450.

[31] Bentham to d'Alembert, spring 1778, Correspondence of Bentham 2:117; Bentham, Fragment on Government, 105n; Goldworth, Deontology, 52, citing Bentham MSS, University College Library, 158. See Harrison, Bentham, 113-117; Mack, Bentham, 105-110, 417-420; C. Blount, "Bentham, Dumont and Mirabeau," University of Birmingham Historical Journal 3 (1952): 153-167; Jarrett, Begetters of Revolution, 130-132.

of a god who when he was in an ill humour used to get a parcel of overgrown schoolboys to blow it in people's faces." He claimed that the Oxford professors held that chemistry was a science "fit only to make a man an atheist or an apothecary." The proper chemistry was precisely directed at reform of learning and cure of aerial disease. Thomas Beddoes, chemistry lecturer at Oxford from 1787 until his departure under a political cloud in 1793, argued famously that "nothing would so much contribute to the rescue of the art of medicine from its present helpless condition as the discovery of the means of regulating the atmosphere." Beddoes built this medical meteorology into his attack on the Pitt administration. So did his ally Joseph Priestley: hence, for example, his image of the pathology of the established universities. Priestley told Pitt in 1787 that they "resemble pools of stagnant water secured by dams and mounds, and offensive to the neighbourhood." Pneumatics and discovery were the key items in the collective strategy. The projector and the experimenter were the ideal types of the interests for which rational dissenters and utilitarians spoke.[32]

Bentham's contacts with Priestley, and then with Shelburne, were dominated by these new interests. Priestley had an explicit account of how experimenters should work together. In a preface to one of the volumes Bentham abstracted in spring 1774, Priestley explained that "this rapid progress of knowledge" would mark "an end to all undue and usurped authority in the business of religion as well as science." This gave a political role to the projector and the discoverer. In 1791 Priestley answered Burke with the claim that commerce and true philosophy would help to inaugurate "the social millennium."[33] Bentham worked strenuously as just such a projector of schemes in the arts and philosophy in the 1770s. He plotted an approach to the Longitude Board with whom Priestley had had such strife, suggested an improved chronometric design, investigated the rewards for discovery, and prop-

[32] For Bentham on his Oxford studies, see Linder and Smeaton, "Schwediauer, Bentham and Beddoes," 268-270, printing Bentham MSS, University College London, 156.5-7; Bentham to Jeremiah Bentham, 10 March 1762, 15 March 1763, 4 April 1763, Correspondence of Bentham 1:60, 67, 70. For Beddoes, see Thomas Beddoes, Observations on the Nature and Cure of Calculus, Sea Scurvy, Catarrh and Fever (Oxford, 1792), cited in Stansfield, Beddoes, 147-149; Trevor H. Levere, "Dr Thomas Beddoes at Oxford: Radical Politics in 1788-1793 and the Fate of the Regius Chair in Chemistry," Ambix 28 (1981): 61-69. For Priestley on the universities, see Rutt, 19:128 (1787).