4

It is now possible to estimate the extent of the disentail in the provinces of Castile. We know from the catastro of la Ensenada the value of properties belonging to ecclesiastical institutions in each province of Castile. This figure appears in Table 5.4, Column A. Table 5.3, Column B, gives us an approximate total amount of the deeds of deposit for ecclesiastical disentail in each province, but for our purpose it must be converted to an equivalent figure in cadastral value. From Appendix E, we have an estimate of the ratio of the face value of the deeds of deposit to cadastral value for the different forms of payment and the different types of property. We must first establish the proportion of the sales paid for under each form of payment (hard currency, vales reales, etc.). For this purpose, the data on the provinces of Jaén and Salamanca is used as representative of all Spain, admittedly a limited and selective sample but the only one available to me.

Next, we must establish the proportion of the sales made up by each of the different types of property, since the ratio of sale price to cadastral value differed among them. Again we start with the information from Salamanca and Jaén, but it would be unreasonable to expect these two provinces to be representative of the distribution of different cultivations throughout Spain. If we assume that the disentailed properties were a cross section of all agricultural property in each province, we can make

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the necessary adjustment for each province by using a contemporary source, the Censo de frutos y manufacturas de España é Islas Adyacentes, prepared in 1799 by the royal government.[14] Its information has been shown to be wrong in specific respects,[15] but it can serve to establish a rough concept of the provincial structures of agrarian property, for it gives the value of the different agricultural products in each province.

From Appendix E we learn that in most provinces one can estimate that the mean face value of a deed of deposit was approximately thirty times the cadastral value of the same piece of property (a ratio of 30 : 1). In provinces where the proportion of improved land was high, the ratio would have been higher than 30 : 1 because we found that buyers in the disentail offered a higher markup over the cadastral value for improved land than for arable. These provinces, according to the Censo de frutos, were Córdoba, Galicia, Granada, Murcia, and Seville. The proper ratio appears to be 36 : 1 for Granada and 34 : 1 for the other four. Madrid also needs a special ratio because a large amount of urban property was sold here, at a high markup. A ratio of 43 : 1 is applied. We can now divide the total amount of the deeds of deposit for ecclesiastical disentail in each province (Table 5.3, Column B) by 30 (or the larger number for the six provinces noted) to obtain the approximate cadastral value of the property disentailed (Table 5.4, Column B). With this information, we can calculate a preliminary estimate of the percentage disentailed in each province (Table 5.4, Column C).

Except for Madrid, the percentages in Column C vary between 5 and 28. The figure 50 percent for Madrid is not correct. If the buyer of a property did not live in the province where it was located, he could opt to make his payment to the commissioner in his province. The records show that many residents of Madrid adopted this option, buying properties of considerable value in other provinces and having the sales recorded in Madrid. As a result the Madrid total represents more than the amount sold in its province. Let us suppose that 25 percent of the ecclesiastical properties of Madrid were sold, a credible figure since there were many sales. We must distribute the remainder of the amount deposited in Madrid among the other provinces.[16] The distribution can be made proportional to the amount sold in each province, but the three bordering provinces, Guadalajara, Toledo, and Segovia, deserve more. I

[14] Censo de frutos y manufacturas.

[15] Fontana Lázaro, " 'Censo de frutos y manufacturas.' "

[16] We must use the ratio 30 : 1, not 43 : 1 of Madrid. The provinces of Castile represent 79 percent of all the sales outside Madrid; we must distribute only this much of the remainder among them.

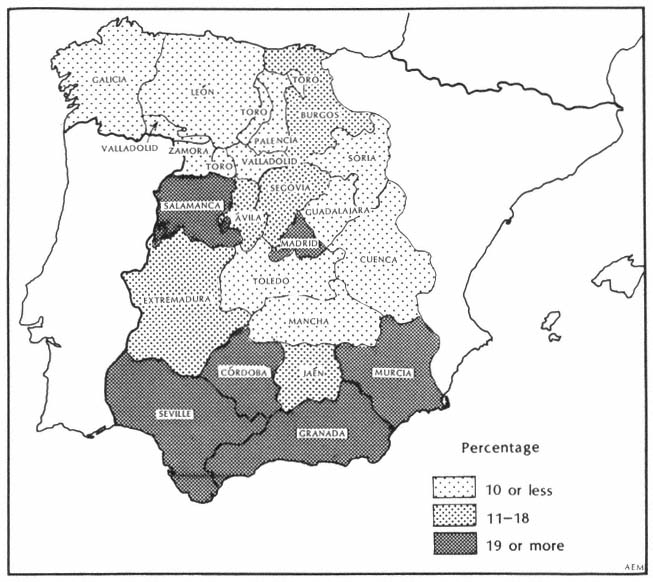

Map 5.1.

Castile, Proportion of Ecclesiastical Property Disentailed, 1798–1808

have assigned them a proportion double that of the other provinces. The result is that one must increase the amount of sales in provinces outside Madrid by 8.06 percent and in Guadalajara, Toledo, and Segovia by 16.12 percent. Raising Table 5.4, Column B, by these percentages, one obtains the results in Column D. The corrected percentages of ecclesiastical property disentailed are in Column E. They run from 6 to 30 percent.[17]

The significance of this table can be better understood by looking at the results in Map 5.1. It becomes clear that the disentail had more effect in the south than elsewhere. There is an impressive block of provinces from Seville to Murcia where 19 percent or more of the properties owned or controlled by the church were sold, and in Jaén the propor-

[17] There have been some recent studies of the desamortización of Carlos IV, but they do not provide provincial totals that can be checked against Tables 5.3 and 5.4: Campoy, Política fiscal; Marcos Martín, "Desamortización"; and Pardo Tomás, "Desamortización."

tion was 16 percent. Other areas of high sales were Salamanca (20 percent) and Madrid (25 percent, although the figure for Madrid is arbitrary, as we saw). At the other extreme are two blocks of provinces where 10 percent or less was sold: the northwest sector of the kingdoms of León and Old Castile, including Galicia, and all New Castile except Madrid and Extremadura, together with Soria, which borders on this block to the north. Between these two blocks runs a belt of provinces from Burgos to Extremadura, including Segovia and Ávila, where between 14 and 17 percent was sold. Because of the number of unknowns in our calculations, one cannot expect the percentages to be exact, but the pattern revealed by the map is hardly likely to be the result of a coincidence of errors.

Probably the most important factor in accounting for the pattern is the proportion of ecclesiastical property that belonged to obras pías, memorias, and other foundations subject to the decree of 1798. It was very likely greater in the areas of higher disentail, but there is no easy way to check this assumption. Human factors also played a part, for much depended on the dedication and efficiency of the royal commissioners in charge of the operation. On the other hand, factors such as regional types of agriculture or local weather did not have much effect. An analysis of the total value of sales in each province in each year produces no regional patterns, as one would expect if the kind or size of harvests had played a role. A large proportion of sales in one province might occur in a year during which there was little activity in neighboring provinces. (There was, however, a decline in sales in most provinces in 1803, 1804, and 1805, years of bad harvests and rural crisis.)[18]

The dedication of the local commissioners was critical, as the royal advisers were aware. Repeatedly in the early years, the king issued circulars to the intendants urging them to put pressure on their subordinates and local justicias to hasten the sales.[19] The archives of the ministry of hacienda include a copy of an order dated November 1799 from the intendant of Seville to the justicias of the province to push the disentail, threatening, if they did not, to send a royal agent at their expense to act for them.[20] In 1804, when sales were notably slow, the king through the president of the Consolidation Fund once more pressed the intendants to use all their energies to hasten the affair. Again the intendant of Seville passed the word on to the justicias of his province, with the warn-

[18] For the annual sales for all Spain, see Appendix F.

[19] Circulares, 18 Nov. 1799, 26 Mar. 1800, 7 May 1800, AHN, Hac., libro 6012.

[20] Circular, 15 Nov. 1799, ibid.

ing, "If as a result of your inactive disposition I do not see all the good effects that ought to be forthcoming, I shall take against you the most serious measure that corresponds to your indolence in a matter so stringently urged by higher authority."[21] Seville was one of the regions where a high percentage of ecclesiastical property was sold, but it is impossible to tell from the evidence here if the intendant's threats overcame the perennial problem of administrative linkage with local officials whose loyalties lay elsewhere or if the province had a greater than average number of eager potential buyers with disposable capital.

A judge of the Cancillería of Granada, who bitterly opposed the disentail, later described in scathing terms the attempts of the government to force its officials to carry out its instructions. All to little avail, the judge recalled: "But despite such efforts the truth triumphed, de jure and de facto, and in accord with it they [the agents of the crown and the prelates of the church] remained remiss in the consummation of the sales, presenting a tacit resistance in this prudent way, in default of open resistance, which they could not and should not oppose to an irresistible force."[22]

As the judge pointed out, the attitude of the church authorities was also a factor. Capellanías and charitable foundations whose properties had been donated by religious institutions could not be sold without their permission.[23] It is easy to imagine that few prelates accepted with alacrity the royal invitation of 1798 to proceed with disentail. One who did was the Jansenist bishop of Salamanca, Antonio Tavira y Almanzán, a friend of Jovellanos,[24] who favored the undertaking. Many properties of capellanías were sold in Salamanca, but few in Jaén.[25] Besides Madrid, Salamanca was the only province outside Andalusia that had more than 19 percent of its church properties sold, Jaén the only province in Andalusia below that figure. The attitude of servants of church and state may explain these peculiarities in provincial responses; nevertheless, the overall pattern observed in Map 5.1 must reflect major regional differences in the nature of ecclesiastical property, that is, conditions produced by previous history.

According to these calculations, 15 percent of all ecclesiastical property in Castile was disentailed. It is true that this proportion is based on

[21] Circular, 5 Nov. 1804, and letter of intendant, 14 Nov. 1804, ibid.

[22] Reguera Valdelomar, Peticiones, 125.

[23] Circular, 18 Nov. 1799, AHN, Hac., libro 6012.

[24] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 415–16; Saugnieux, Prélat éclairé, 269–70.

[25] As determined by the study of the towns in Part 2.

the only total figure available for ecclesiastical property derived from the catastro made under Fernando VI, but the holdings of the church would not have increased much by the reign of Carlos IV. This was no longer a time of large grants for religious ends, and the government frowned on any increase in manos muertas. In making these calculations I have been careful not to overestimate the proportion sold, leaning rather in the other direction. Fortunately, there is independent confirmation of its extent. Among the questions that Napoleon posed the Spanish bureaucrats in 1808 were the following: "What is the amount of capital that is the product of the sales of the properties of charitable foundations [obras pías]? Of the clergy? What is the estimate of how much remains to be sold of the properties of charitable foundations and of the clergy, in comparison with the quantity of both kinds of property whose sale has already been ordered?" The Spanish officials did not give an exact answer to the first question because no one had kept a separate tally of disentail of "obras pías" and "clergy." They replied that the sales of obras pías might be 950 million and of the clergy (that is, capellanías) 237 million, a total of 1,187 million. (We know that this figure is low.) To the second question they replied that there remained to be sold 250 million worth of obras pías and 650 million of capellanías. Furthermore, a papal breve of 1806 had approved the sale of one-seventh of all other ecclesiastical property.[26] The officials calculated this seventh to be worth 500 million; that is, they believed the total to be 3,500 million.[27] These figures produce an estimate of the total value of all ecclesiastical property in Spain before the disentail of 1798 of 5,587 million reales. What the Spanish officials estimated had been sold, 1,187 million, was 21 percent of the total.

Thus the financial advisers of Fernando VII believed that a greater proportion of property of the church had been sold than we estimate. They were referring to all Spain, not just Castile; nevertheless, I believe our figure to be closer to the truth, although 15 percent may be too low. One can be reasonably sure that a sixth of all ecclesiastical property was disentailed. In most provinces of Andalusia it was a fifth or more, and, if the figures of the catastro are correct, it was almost a third in Murcia. One must conclude that the disentail of Carlos IV was an event of major significance in the history of the Spanish church and church-state relations.

[26] See below, Chapter 6, section 4.

[27] ANP, AF IV, 1608 , 20 : 26.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

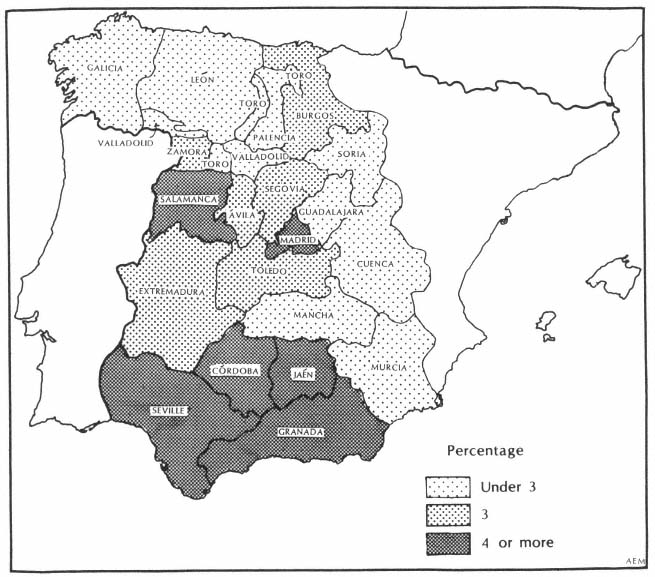

Map 5.2.

Castile, Proportion of All Property Disentailed, 1798–1808