The Highway Coalition at Work

The interplay between public demand, the strategies and motivations of government officials, and other factors that shape transportation patterns—and through transportation patterns alter the distribution of population and jobs—are inevitably complex in a large and variegated metropolis. In the remainder of this chapter, we give three cases closer scrutiny to show this interplay in more detail. The first case describes the steps leading to construction of the Holland Tunnel and the George Washington Bridge. Here we see the limitations of relying on the private sector for the development of large transportation projects. Also underscored is the importance of organizational motivations and strategies in encouraging and crystallizing "public demand" for highways, and in shifting regional priorities from rail projects toward a road-building program. Moreover, in the Port Authority's successful effort to

[33] Ibid., pp. 7, 21, 30. In fact, Triborough revenues built up more rapidly than expected, and the agency assumed full responsibility for constructing and financing the Narrows Bridge at the end of 1959.

[34] Ibid., p. 38.

absorb a rival agency—to ensure that there would be no competition in tolls among trans-Hudson facilities, and that the "profits" would be at the disposal of the Port Authority—we see the importance of strategic skill in laying the groundwork for the authorities' later capacity to engage in regional development works.

A second case focuses on construction of the Manhattan Bus Terminal, and illustrates the importance of planning and political capabilities in carrying out a significant project in the face of opposition from the private sector and governmental rivals. In the third case, we look more closely at the motivation and results of the major project resulting from the highway coalition's studies of the 1950s, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

Under and Over the Hudson River

Demands for vehicular routes that would overcome the Hudson barrier to regional commerce and travel began long before 1900. The initial efforts failed because of differences in perspective and priorities between the states, and because of a desire to rely on private enterprise.

As early as 1868, New Jersey chartered a private company to construct a bridge across the Hudson, but concurrent authority was not obtained from New York State until 1894; the company made no progress and finally lost its charter in 1906 for nonpayment of taxes. In 1890, a second group obtained a federal charter for a private toll bridge, but could not raise money to begin construction. In 1917, the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey studied the possibility of a tunnel under the river but decided against it because of high costs.

As Erwin Bard notes, "private enterprise struggled for a long period with the problem of providing interstate crossings" for motor vehicle traffic.[35] Meanwhile, vehicular passengers and freight were compelled to use ferries and barges to cross the Hudson. Their slow journeys contrasted sharply with travel between New Jersey and New York City by rail tunnels after 1910. The completion of these tunnels under the river permitted the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Hudson and Manhattan rail company to bring their passengers from New Jersey directly into Manhattan terminals.

In the period between the two world wars, three major vehicular crossings were completed: the Holland Tunnel in 1927 and the George Washington Bridge in 1931, followed by the Lincoln Tunnel, which began operation at the end of 1937. Among the reasons for this sudden surge, with its considerable impact on the region's patterns of population growth and commerce, were the sharp rise in motor transportation during the 1920s, coupled with appeals from Bronx and Manhattan business groups, who favored the crossings as a way to reduce ferry congestion on the river and to improve business by reducing transportation time for customers west of the Hudson. Perhaps even more significant was the creation of new government organizations to overcome the interstate hiatus, together with the allocation of public funds for their construction activities, and the skillful efforts of these new agencies to enhance their power.

[35] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, p. 192. The factual data in this section are drawn mainly from Bard's definitive study.

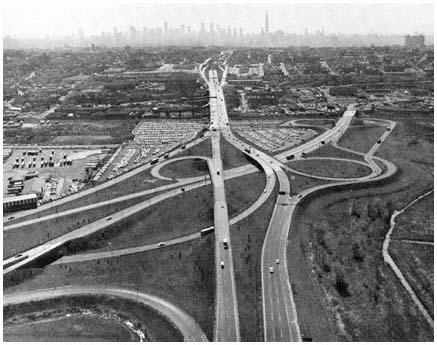

The roads linking the New Jersey Turnpike and the Lincoln

Tunnel in Hudson County were built through

cooperative efforts of three major components

of the highway coalition—the Port Authority,

the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, and the New Jersey Highway Department.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

After the early private efforts failed, the two states created commissions in 1906 to study ways of spanning the Hudson. Intermittent cooperation and several sporadic reports followed. The commissions suggested a tunnel under the river between lower Manhattan and Jersey City, but were unable to agree on how it would be financed or administered. "After years of groping and fumbling," the two states finally agreed in 1919 to establish independent state commissions to function in unison (it was hoped) and construct the proposed tunnel. The cost of the tunnel would be financed by tolls. Conflicts between the two commissions were frequent during the next several years, and cost overruns required additional state aid, but the Holland Tunnel finally opened in November 1927.[36]

Meanwhile, the Port of New York Authority had been established in 1921 as a joint agency of New York State and New Jersey. The authority was given broad responsibility for solving transportation problems in the region, but the main motivation for its creation was the widespread desire to improve the handling of rail freight. The agency's officials soon entered into complex

[36] Ibid., pp, 178–183; the quoted phrase is on p, 180. The original estimated completion date had been 1923.

negotiations with the railroads aimed at devising a more efficient system of consolidated freight yards and related facilities throughout the region.

At the same time, business and civic groups urged both states to approve additional vehicular crossings for the Hudson River. Neither governor was pleased with the performance of the dual commissions, and both agreed in 1923 that future bridges and tunnels should be "constructed and financed by the Port Authority." Initially, the authority showed little interest in turning to vehicular projects, as its negotiations with the railroads "seemed on the verge of important accomplishments." But when these discussions foundered, Port Authority officials began to look actively for an alternative program. As Erwin Bard, historian of the authority's development, commented:

Within the Port Authority the center of gravity began shifting to vehicular traffic. . . . The "do-something" policy in terms of construction was rising. It was imperative that the Port Authority's credit, hitherto entirely theoretical, be established. The bridge-building program offered a chance.[37]

The major project under consideration at this time was a bridge across the Hudson between upper Manhattan (about 178th Street) and Fort Lee, in Bergen County. A bridge in this location was favored by business and civic interests in Manhattan, and the proposal was pressed actively in the early 1920s by government officials and civic leaders in Bergen, who saw the bridge as a key factor in Bergen County's ability to attract the new wave of suburbanites. Among the leading New Jersey supporters of the project were the editors of the Bergen Record (whose economic strength and influence would grow with an expanding population) and state senator William B. Mackay (who hoped that leadership in meeting public concern for improved transportation facilities would advance his gubernatorial aspirations), as well as other civic leaders and government officials in the county.[38] Thus the campaign for the bridge illustrated the interrelationship between public demand, the interests of civic and business leaders, and strategic aims of public officials. Among the government units centrally involved was the Port Authority, whose leaders were actively seeking a path to success. They found it through undertaking the bridge project, and then used that effort to eliminate a rival organization and to establish a long-range financial strategy for institutional growth and power.

The Port Authority's leaders did not believe they could move publicly and decisively to harness the support which the 178th Street bridge commanded. For the proposal attracted opponents as well as enthusiasts. Some

[37] Ibid., pp. 182, 185.

[38] The most active civic group in the New Jersey campaign for the bridge was first named the Mackay Hudson River Bridge Association. The efforts of Mackay, the Record, local officials, and others are recounted in Jacob W. Binder, All in a Lifetime (Hackensack, N.J.: published privately, 1942; available in New Jersey libraries), pp. 181–198. Binder served as executive director of the Bridge Association. On the campaign for a bridge at 178th Street, see also "For Hudson Bridge Above 125th Street," New York Times, December 28, 1923; "Chamber Opposes Bridge at 57th Street," New York Times, January 4, 1924; "Greene Tells Plan for Hudson Bridge," New York Times, May 4, 1924; "Bridge Across Hudson at 178th Street is Discussed at Interstate Conference," New York Times, January 21, 1925; "Approves Hudson Bridge," New York Times, February 3, 1925; "Diners Hail Mackay as Father of Bridge," New York Times, April 23, 1925.

business and civic groups strongly favored a rival plan for a combined railroad-vehicular bridge, perhaps to be built by a private corporation, at 57th Street in Manhattan. Several conservation groups objected to the loss of park land that would occur if the bridge were built in the vicinity of 178th Street. Regional jealousy reared its expected head, when spokesmen for Queens criticized the project as catering to New Jersey's interests while the city's transportation needs were neglected. And some legislators in Trenton argued against expanding the Port Authority's role to include highway bridges.[39]

Amid these conflicts, the Port Authority moved cautiously. After a series of hearings in 1923, it concluded that a vehicular bridge should be built "north of 125th Street." As sentiment in favor of a span at 178th Street crystallized during the next year, the authority's chairman called such a crossing a "great necessity," and circumspectly announced in December 1924 that the authority was "ready to perform whatever tasks are designated to it" by the two states.[40] But when the authority was attacked as an advocate of the bridge proposal, its officials explained that the Port Authority had only concluded that "perhaps a bridge at some point" north of 125th Street was needed.[41]

Out of the public eye, however, Port Authority lawyers and engineers worked closely with both governors and with citizen groups who favored the bridge, as they pressed for legislative approval. Finally, in the spring of 1925, both states enacted legislation authorizing the Port Authority to construct the Hudson River bridge.[42]

Two years later, the Port Authority could speak about the project more expansively. The bridge across the Hudson, the agency declared, "means that the dream of many years and of many millions of persons will finally be realized." The "agitation" for such a bridge "took on the form of a public demand from the populations on both sides of the stream," the authority explained, "until the demand could be no longer logically be resisted."[43] Construction was begun at the 178th Street site in 1927, and the George Washington Bridge was opened to traffic in 1931, ahead of schedule and at a cost below the original estimate.

If Port Authority officials wished to satisfy their newly developed interest in motor transport, however, it seemed imperative that the revenue-

[39] The opponents' views are set forth in "Sees Need for Five New Hudson Tubes," New York Times, December 6, 1923; "Chamber Opposes Bridge at 57th Street," New York Times, January 4, 1924; "Insist on 57th Street Bridge," New York Times, January 6, 1924; "Ferries, Bridges and Tunnels," editorial, New York Times, January 15, 1924; "Hudson Bridge Bill Passed," New York Times, February 10, 1925; "Committee Favors 57th Street Bridge," New York Times, February 28, 1925; "Move to Save Park at Fort Washington," New York Times, March 18, 1925; "Fear Effects of Bridge," New York Times, March 28, 1925.

[40] Port of New York Authority, "Report to the Governors," December 21, 1923, reprinted in Port Authority, Third Annual Report: 1923 (New York: February 1, 1924), pp. 43–50; Julian Gregory, chairman of the Port Authority, quoted in "Explains Bridge Plan," New York Times, December 30, 1924.

[41] W. W. Drinker, Chief Engineer of the Port Authority, quoted in "Move to Save Park at Ft. Washington," New York Times, March 18, 1925.

[42] Laws of New Jersey, 1925, c. 41; Laws of New York, 1925, c. 211. In 1924–26, the authority was also authorized to build three smaller vehicular bridges between Staten Island and New Jersey.

[43] Port of New York Authority, 1926 Annual Report (New York: January 20, 1927), pp. 55–56.

producing Holland Tunnel be acquired. For the Holland Tunnel, opened by the dual commissions in the fall of 1927, proved an immediate success. High traffic volumes and substantial revenues generated enthusiasm within the two commissions for more projects, and in 1928 they recommended to both states that they be authorized to construct a tunnel to midtown Manhattan immediately, and three other crossings thereafter. Meanwhile, sagging toll revenues on the Port Authority's facilities raised doubts as to the ability of the authority to meet its financial obligations.[44]

At this point, the Port Authority exhibited the tactical skill that would become a hallmark of its operations. In private discussions and public debate, it argued for the following approach to regional transport development:

1. Interstate rail and highway projects should not be considered separately, but instead as part of one comprehensive transportation plan. (Since the Port Authority already had rail responsibilities and the dual commissions did not, this principle would support vehicular expansion by the authority and cast doubt on the legitimacy of the commissions' efforts.)

2. All interstate motor vehicle crossings should be financed by revenue bonds, not by using the credit of the states. (The authority was authorized to issue revenue bonds, while the commissions used state funds to be repaid out of toll revenues.)

3. To ensure that revenue bonds could be sold to investors, all interstate bridges and tunnels should be under the control of one agency. Otherwise, tolls on one facility (for example, the Holland Tunnel) might be reduced below that of other facilities, and this "unfair competition" would drain off traffic and revenue from the other crossings.

4. As a further aid to revenue-bond financing, income from all projects should be pooled, so that "excess returns from the more profitable enterprises" could support weaker or new facilities.

The authority put forth two other arguments that would not reappear in its later reports and announcements. "It is perfectly obvious," the authority declared, that the general level of tolls "could be placed on a much lower basis" if all facilities were under one management rather than under divided authority. Also, the revenues pooled in the general fund would be devoted to paying off the debt on the interstate crossings, "with a view to making these facilities free from tolls within the least possible time."[45] In fact, the general level of tolls remained at fifty cents until 1975 when it was raised to seventyfive cents.

At a series of meetings in 1930 and 1931, officials of both states finally accepted the Port Authority's arguments, the dual commissions were abolished, and the Holland Tunnel was transferred to the authority. Moreover, the states agreed that future interstate crossings would be developed by the

[44] The Port Authority opened two of its Staten Island bridges in 1928. In 1929 and 1930 revenues from these bridges were far below original estimates, and the first series of bonds seemed likely to face a default. See Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 237–238.

[45] See Port of New York Authority, Eighth Annual Report (New York: December 31, 1928), pp. 59–61; and Port of New York Authority, 1929 Annual Report (New York: December 31, 1929), pp. 51–52.

authority, under the four principles summarized above. Perhaps understating the importance of the Port Authority's deft maneuvers, Bard concludes that the authority's "reputation for efficiency, its autonomous power to finance, and its established credit won in the race for survival."[46]

Through its activities and successes during these early years, the Port Authority established an approach to governmental action that would be repeated again and again in the New York area, as well as in other parts of the country. First, it set a precedent for financing highway facilities by revenue bonds, supported by tolls. This strategy obviated the need for state legislatures to appropriate moneys for such facilities out of general funds, or to approve the issuance of bonds backed by the full faith and credit of the state. Thus, the speed with which self-supporting bridges, tunnels, and turnpikes were constructed during the next four decades was greatly increased. The availability of revenue-bond financing also encouraged state officials to create additional public authorities as a way of avoiding direct responsibility for additional taxes.[47]

A second precedent, that each facility would be supported by the pooled revenues of all other authority projects, shaped the development of later public authorities in the transportation and port development fields.[48] It also had a decided impact on the evolution of the Port Authority itself. The pooling concept provided the rationale and financial base for extensive authority activity in airport, harbor and rail development. Otherwise, the agency would have been limited to those very few projects whose "self-supporting" nature was so evident from the outset that cautious investors would buy bonds without broader security. The pooling concept permitted the Port Authority to insulate individual projects from the short-run (and in some cases even the long-run) impact of market forces. Surpluses from bridges and tunnels could be used to underwrite new enterprises that might incur initial or continuing deficits, if those new projects seemed desirable in terms of overall regional development—or, at times, if they seemed beneficial in terms of the financial strength and public image of the authority and its officials.

[46] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, p. 191. In 1931, the Port Authority was authorized to proceed with the midtown Lincoln Tunnel. Strictly speaking, the dual commissions were not abolished, but merged with the PNYA, which absorbed some of the commissions' staffs.

[47] For example, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority was created in 1948 partly as a way to overcome the reluctance of the New Jersey legislature to provide substantial sums for highway building in the early postwar years.

Members of the dual state commissions and other critics of the authority concept argued that it would be less expensive, and therefore better, to finance new road facilities with state advances, to be repaid through toll receipts. This approach was used for the Holland Tunnel, and it probably would have been less costly for the later bridges, tunnels, and toll roads to have been financed in this manner, since interest rates on state-backed loans would have been lower than interest on bonds backed mainly by an authority's projected toll revenues. The political disadvantages of state appropriations, however, combined with the mixed administrative record of the dual commissions, were more persuasive at the time. See Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 180 ff.

[48] On the influence of the Port Authority's structure and early evolution on the development of other public authorities, see Council of State Governments, Public Authorities in the States (Chicago: 1953), p. 23; State of New York, Temporary State Commission on Coordination of State Activities, Staff Report on Public Authorities under New York State (Albany: 1956), p. 15; and Richard Leach and Redding S. Sugg, Jr., The Administration of Interstate Compacts (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959), p. 8.

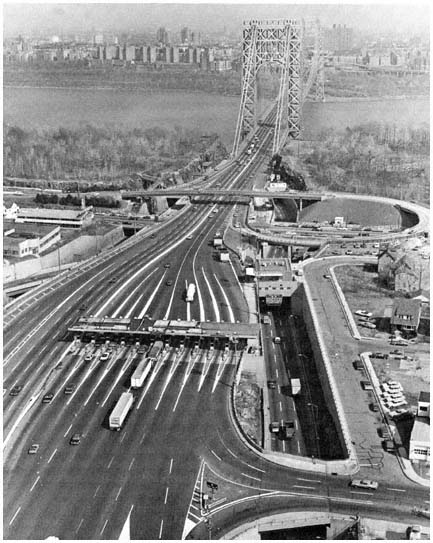

The George Washington Bridge,

looking east across the Hudson River at upper Manhattan with

the Port Authority's toll plazas in the foreground.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

The Port Authority had spanned the Hudson River, and the new George Washington Bridge soon proved a major revenue producer for the authority. Along with the Holland Tunnel it provided the financial base for constructing the midtown Lincoln Tunnel in the 1930s, and for entering a wide range of other activities a decade later. The bridge also proved a valuable resource in maintaining the image of the Port Authority as an efficient and important regional enterprise. Opened with great ceremony in the fall of 1931, the

George Washington Bridge was widely praised for its design and construction—it was the longest suspension bridge in the world—and because of its impact on Bergen County. During the next two decades, the authority was frequently commended for inaugurating "a new era in bridge building" with this majestic span, and the bridge was called the "greatest single factor in Bergen County's growth."[49]

The new bridge did indeed have a significant impact on development west of the Hudson. Previously, rail lines and ferries provided only circuitous, time-consuming access to Bergen, and the sprawling county had remained a semirural enclave while nearby counties with better access to Manhattan urbanized rapidly before World War I.[50] Once the two states had approved the bridge in 1925, real estate speculators packed the county office building in anticipation of the land boom.[51] The next thirty years saw a tripling of Bergen County's largely middle-class population, many of the new residents having departed from the Bronx and other parts of the core to "reside in the pleasant environment of Bergen County."[52]

Property values also climbed rapidly. Between 1920 and 1954, assessed values increased by more than 250 percent in Bergen, compared with about 100 percent in Essex County and in the Garden State as a whole during this period. And the decision to span the Hudson at 178th Street, rather than at 125th Street or 57th Street (the latter across from Hudson County), altered the attractiveness of land and the pattern of growth within the county. Changes in property values among Bergen's towns illustrate the impact of the bridge: municipalities nearest the span saw their taxable property increase especially sharply, rising from three to ten times the 1920 values.[53]

For Port Authority strategists who recognized favorable publicity as a route to enhanced power, the George Washington Bridge and its impact gener-

[49] The quotations are, respectively, from "Development of New York Port Lesson in States Co-operation," Christian Science Monitor, May 5, 1946, and "The Birth of a Bridge," editorial, Bergen Evening Record, April 30, 1946.

[50] Much of Bergen County was as close to the Manhattan CBD as the Bronx and southern Westchester County, which were served by direct rail service and a growing highway network, and no more distant than Essex and Union counties in New Jersey, which had direct rail service to Manhattan. Travelers from Bergen County who did not wish to swim the Hudson reached Manhattan by journeying south via rail or road into Hudson County, where they could cross by the Weehawken ferry, or (going farther south) via the Hudson and Manhattan rail system (now PATH).

[51] "The proposed bridge over the Hudson River," reported the New York Times in December 1925, "has so stirred up real estate activities in Bergen County that the searcher's room in the new $1 million court house at Hackensack is wholly inadequate. Today petitions were circulated asking the Freeholders to provide more room for the lawyers' clerks and searchers." ("Bridge Talk Stirs Bergen County," New York Times, December 4, 1925.)

[52] Donald V. Lowe, "Port Authority Behind Bergen's Boom," Bergen Evening Record, October 30, 1953. During the period 1920–1954, while Essex County added 46 percent to its population and New Jersey as a whole gained 66 percent, Bergen's population rose by more than 200 percent. In addition to the bridge, other factors, such as a relatively large amount of undeveloped land (as of 1920), influenced Bergen County's high rate of population growth. For discussions of the interrelation of factors in suburban growth, see Chapters 1–3 above and Edgar M. Hoover and Raymond Vernon, Anatomy of a Metropolis, Chapter 8.

[53] Bergen County taxable property as a whole increased between 1920 and 1954 from $207 million to $760 million. Among the towns nearest the bridge, Teaneck's taxable property rose most sharply, from $4 million to almost $45 million; Hackensack's increased from $16 million to almost $52 million, and Cliffside Park from $4 million to more than $15 million. See PNYA and TBTA, Joint Studies of Arterial Facilities, p. 34.

ated a steady flow of heart-warming journalistic comments. The span was mentioned prominently in many articles during the 1930s and 1940s reviewing the authority's "far-sighted intelligence" and "monument of vast public works."[54] And if attention lagged, the agency was able to assist friendly editors by preparing informative essays such as the 1953 Bergen Record article, "Port Authority Behind Bergen's Boom," written by Donald V. Lowe, then vice-chairman of the Port Authority.[55]

Bringing Manhattan Closer to the Suburbs with Buses

Despite the Depression, the region's motor vehicle traffic continued to increase throughout the 1930s, and the Port Authority and its fellow roadbuilders added additional highways and river crossings. The Port Authority's main contribution was the Lincoln Tunnel, opened in 1937, taking traffic from New Jersey under the Hudson River directly into mid-Manhattan. And as the highway alliance built, still more travelers journeyed into New York City by motor vehicle, and Manhattan's CBD became choked with automobiles, trucks, and buses.[56] Expanding traffic had a more positive impact on the Port Authority than on city streets. The port agency's toll income increased, its surpluses grew, and by the early 1940s a once-struggling rail freight planner had become a wealthy and dynamic bridge and tunnel entrepreneur.[57]

Close study of vehicular patterns revealed, however, that traffic expansion on the authority's crossings was being retarded by financial difficulties in

[54] "Port Authority Birthday," editorial, New York Times, April 30, 1946. For a selection of other comments on the bridge and the authority, see PNYA, 25th Anniversary (New York: 1946), a booklet of articles and editorials.

[55] Bergen Evening Record, October 30, 1953. One of Lowe's fellow Port Authority commissioners was John Borg, long-time publisher of the Record and an early advocate of the 178th Street bridge.

Sometimes those friendly editors relied so fully on the authority's press writers that they seemed to confuse the Port Authority's activities and their own. Thus the Journal of Commerce, in a full page review of the agency's "majestic" bridge and other accomplishments, waxed warmly on the authority's landmark financing efforts, which were notable because "our first issues" were much larger than any previous public revenue-bond issue. The Journal 's writer then commented, no doubt to the surprise of the newspaper's stockholders, that "any surplus from our operations ultimately belongs to the States of New Jersey and New York," and concluded with the sober admission that "we cannot turn to the taxpayers for reimbursement of losses." "New York Port Authority Traces 25 Years of Progress: It Has Accomplished Much in Many Fields of Endeavor," Journal of Commerce, May 22, 1946; emphasis added.

[56] For example, trans-Hudson vehicular traffic rose from 16.9 million vehicles in 1934 to 30.6 million in 1941. Under the impact of gasoline rationing and "pleasure-driving" bans during World War II, traffic then dropped sharply, hitting a low point of 21.9 million in 1943 before rising again in 1944, reaching 27.2 million that year. See Port of New York Authority, Fourteenth Annual Report (New York: March 18, 1935), pp. 34, 36; Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941 (New York: March 31, 1942), p. 15; Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943 (New York: April 1944), pp. 1–2, 7–8; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944 (New York: November 15, 1945), pp. 2, 6–7.

[57] Investment in facilities had risen from $38 million in 1928 to $238 million in 1944. Net annual revenues (after payment of debt service), which had been a deficit figure until acquisition of the Holland Tunnel in 1931, rose from $2,854,000 in 1934 to $6,424,000 in 1940 and $8,740,000 in 1941. Even during the war, annual net income never fell below the 1940 figure. See Port of New York Authority, Eighth Annual Report, p. 82; Fourteenth Annual Report, p. 55; Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 14; Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, p. 33; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, p. 44.

New Jersey. The state highway department, supported by tax dollars rather than tolls, had managed to construct the Pulaski Skyway and related roads bringing traffic to the Holland Tunnel, and two major highways joining with the George Washington Bridge. But its efforts to build other highway projects had been curtailed by limited tax dollars. Conceivably the Port Authority might have allocated some of its toll profits in order to assist in financing related highway networks—thus adding, in the long run, to its own toll revenues while accelerating suburban mobility. But the authority did not embark on this course. As Bard comments, reflecting the views of the agency's officials at the time, "it is too much to expect that a bridge or tunnel, as a toll gate, should finance the construction of miles of highway." Much of the total cost "must be shouldered by the states and localities," so that in a "general program of highway expansion . . . toll collection is merely an auxiliary method of paying for the costs."[58]

This modest view of the toll agency's "auxiliary" role in regional highway development was not without advantages to the Port Authority, of course. While state and local agencies struggled, in these lean years, to attract enough tax dollars to meet growing highway needs, authority officials could turn their thoughts and surpluses to other challenges. The original Port Compact hardly envisioned a Port Authority devoted solely to subsidizing highway construction, and as available funds grew in the early 1940s authority officials sought new ways to shape the "development of the port" and to enhance the influence of the port's chief advocate.[59] This was a time for expansion.[60]

[58] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 213–214. "The bridges and tunnels have been built and they are in operation," the Port Authority commented in 1940, but "the situation which now confronts the States, and particularly New Jersey, is that . . . a comprehensive system of arterial roads to feed these facilities . . . has yet to be constructed." Port of New York Authority, "Report Submitted to the New Jersey Joint Legislative Committee Appointed Pursuant to the Senate Concurrent Resolution Introduced March 11, 1940" (New York: June 1940), p. 32; emphasis added. See also pp. 30–32, 63–64; Port Authority, Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 11; and Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, letter of transmittal (pp. 6–7), and p. 16.

This distinction also underlay the reaction of a long-time authority official when reading a draft of this chapter. "The Port Authority should not be characterized as a highway-building agency," he protested; "in the field of vehicular transportation, it is only a bridge-and-tunnel agency."

[59] In the 1921 compact, the two states agreed to "faithful co-operation in the future planning and development of the port of New York" (Article I), and created the Port Authority, "with full power and authority to purchase, construct, lease and/or operate any terminal or transportation facility" (Article VI). Thus the authority's officials could roam across this wide field, although they were limited by the need to ensure a long-term income flow that exceeded costs. (The compact is reprinted in its entirety in Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 329–339.)

[60] In their search for new tasks, the authority's leaders were motivated not only by the challenges of the postwar era they saw ahead of them, but also by a look behind—at the host of automobile users, truck drivers, and bus companies pursuing them, demanding lower tolls on Port Authority bridges and tunnels. The authority had already faced one legislative inquiry on this issue, in 1940, and successfully defended its view that the existing (50-cent) toll level must be maintained in order to provide funds for "future improvements" in the port district. But its officials realized that pressure to reduce toll rates would become irresistible if the agency did not soon commit its growing surpluses to new projects. On the 1940 inquiry, see Port Authority, "Report Submitted to the New Jersey Joint Legislative Committee . . . " (the quotation above is on p. 40), and Port Authority, Twenty-First Annual Report: 1941, p. 11. On the pressures confronting the Port Authority in the mid-1940s and the views of its officials at that time, see Herbert Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," in Harold Stein, ed., Public Administration and Policy Development (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1952), especially pp. 182–183.

So it was that by 1943 the Port Authority had cast an admiring eye upon the problems confronting the region in the field of air transport, and after a lengthy series of negotiations the agency assumed control of the region's three major airports in 1947–1948. Meanwhile, in 1944 and 1945, it took over a marine terminal facility in Brooklyn and began a study of port terminals in Newark, leading to a lease signed in 1947 providing for authority control, rehabilitation, and operation of Port Newark.[61]

In the long run, Port Authority operation of these leased facilities might prove of great benefit to the port's commerce and to the authority's own reputation.[62] But some greater initiative was needed—something the authority could create itself. As the war drew toward a close, the agency expanded its planning staff, completed a careful analysis of traffic patterns, and announced that it was prepared to construct "the world's largest bus terminal" to help relieve the "intolerable midtown Manhattan traffic congestion."[63]

The need for such a terminal seemed evident to the region's transportation planners. By the early 1940s, the influx of bus traffic from west of the Hudson—traveling on Port Authority facilities—had become an important factor in traffic congestion in the CBD. Most of the buses brought New Jersey passengers through the Lincoln Tunnel and deposited them at eight separate private bus terminals scattered between 34th and 51st Streets. By 1944, 1,500 buses each day crossed the Hudson bound for mid-Manhattan and most of them were caught regularly in heavy midtown traffic bottlenecks. It was anticipated that a union terminal near the Lincoln Tunnel would draw off most of this traffic, eliminating more than two million miles of bus travel in midtown Manhattan annually—and thus providing traffic relief equivalent to two or three additional crosstown streets.

In fact, a bus terminal of this kind had been proposed earlier by the bus companies and by New York City's own transportation planners. But the bus lines, each wary of losing the competitive advantage of its existing midtown station, could not agree on joint terminal operations. And the city administration, its staff and financial resources stretched thin by other service demands, had made no progress. New York's mayor was therefore glad to be able to turn to the authority's able planners. With his encouragement, the Port Authority developed a proposal in 1944 for a major terminal (between 40th and 41st Streets, and 8th and 9th Avenues) that would replace individual bus termi-

[61] The Port Authority's growing interest in air transport is indicated in its annual reports for 1942–1945, and its negotiations and acceptance of the airport and harbor facilities are summarized in its reports in 1944–47. See Port Authority, Twenty-Second Annual Report: 1942, letter of transmittal (p. 4); Twenty-Third Annual Report: 1943, pp. 14–15; Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, pp. 11–13, 20–22; Twenty-Fifth Annual Report: 1945, (New York: July 1, 1946), pp. 8–9, 18–23; Twenty-Sixth Annual Report: 1946, (New York: November 1, 1947), pp. 2–19; Twenty-Seventh Annual Report: 1947, (New York: November 1, 1948), pp. 6–7, 24–25, 30.

On the airport negotiations, see also the perceptive study by Kaufman ("Gotham in the Air Age," 143–197), analyzing the conflicts between Robert Moses, the Port Authority, New York City's administration, and other participants. As Kaufman's analysis indicates, the ability of the Port Authority to allocate funds to rehabilitate and operate the airports was a crucial advantage as the authority negotiated to take over these facilities from the financially strapped municipalities.

[62] Actually, ownership of the Brooklyn grain terminal was transferred by New York State to the PNYA; Port Newark and the three airports were turned over to the authority on long-term leases.

[63] Port Authority, Twenty-Fourth Annual Report: 1944, p. 17.

nals. The authority would not only plan and design, but also finance, construct, and operate the massive new terminal.[64]

The proposal attracted warm support from most of the bus companies, business leaders, the news media and some government officials. But Robert Moses was not so pleased. Wary of the Port Authority's expansionism within New York City, as its bus terminal and airport excursions brought the bistate agency further into his territorial domain, Moses thrust back. Allying himself with the Greyhound bus company (which did not want to be included in the union terminal), Moses donned his hat as a member of the City Planning Commission, persuaded a majority of fellow commissioners to join him in opposing a crucial element of the Port Authority plan, and for two years blocked the terminal. It was, as Herbert Kaufman noted, a "grim and bitter battle."[65]

As midtown bus traffic expanded to more than 2,500 interstate vehicles per day, and complaints of traffic congestion grew, the port agency pressed for approval of "this great public improvement" to relieve an "intolerable" traffic problem costing Manhattan business "an estimated million dollars a day." Finally, in 1947, the city's Board of Estimate endorsed the Port Authority plan, handing Moses one of his few defeats. Revenue bonds to finance the Port Authority Bus Terminal were sold in 1948, and the terminal was opened in December 1950.[66]

The impact of the bus terminal project was manifold. The new terminal reduced travel time for bus passengers by between six and thirty minutes. Bus travel from Bergen, Essex, and other northern New Jersey counties became more attractive, and interstate bus routes were extended more deeply into

[64] see Ibid., pp. 17–19, and Port Authority, Twenty-Fifth Annual Report: 1945, pp. 9–14. According to one Port Authority official involved in the negotiations, New York City's ability to undertake the project itself was weakened by the fact that its staff included "planners but not builders," while the authority, having both, could draw upon its own personnel, propose a feasible plan, and carry it out as soon as the proposal was approved.

During the mid-1940s, the authority also began constructing two union truck terminals authorized before the war.

[65] Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," p. 177.

[66] A complex situation permitted Moses to block the PNYA proposal. The authority had concluded that the new bus terminal would not be successful in consolidating terminal traffic—and thus in reducing traffic congestion and in making the terminal self-supporting in the long run—if any of the bus companies were permitted to build or enlarge existing individual terminals east of Eighth Avenue, an area more centrally located for access to offices and shopping. Therefore, the authority sought approval by the Planning Commission and the Board of Estimate of resolutions to prohibit any bus companies from future bus terminal development in the more central area. Without such action, the authority argued, it could not sell revenue bonds for the terminal; and so construction was deferred pending action by the City. But the Greyhound bus company already had a terminal in the "forbidden area" that it wanted to expand. Therefore Moses supported the Grey-hound application to be exempted from the proposed resolution, using that as his vehicle to persuade the Planning Commission to oppose the blanket prohibition demanded by the Port Authority. For details on the bus terminal case, see the authority's annual reports for 1944 (pp. 17–19), 1945 (pp. 9–14), 1946 (pp. 19–24), 1949 (pp. 76–80), and 1950 (pp. 99–102). The quotations in the text are found on pp. 19–20 of the 1946 report. Commissioner Moses's views are stated in part in his letter of October 16, 1945 to Chairman Howard Cullman of the Port Authority. In that letter, he concluded that the treatment of Greyhound was "grossly unfair" because its officials were "merely proposing to extend a non-conforming use authorized by the courts," and because the bus company had also agreed to spending $300,000 on traffic improvements related to its proposed terminal expansion. (Letter made available to the authors by Mr. Moses.)

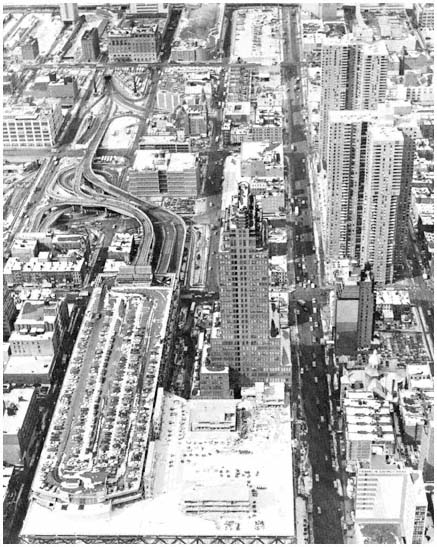

The Port Authority Bus Terminal in mid-Manhattan

is the terminus of commuter bus lines serving

residents of all the counties in the region west

of the Hudson River. The terminal is directly

connected to the Port Authority's Lincoln Tunnel,

as can be seen in the upper left-hand corner of the photo.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

suburban areas. By 1952, about 5,000 buses were using the terminal each day, carrying 130,000 passengers to and from mid-Manhattan, and the number continued to rise during the next decade. Meanwhile, although the new bus terminal was hardly decisive, the reduced travel time it provided was one

more factor tipping the scales against the railroads, as passenger traffic crossing the Hudson by rail declined steadily in the 1950s.[67]

For the Port Authority as for bus travelers, the bus terminal venture was highly successful. The agency was widely praised for providing this "greatly needed" facility, thus aiding travelers and business in the region.[68] The commitment of $24 million to construct the terminal helped absorb the agency's growing reserves. As financial allocations to airports, marine facilities, and truck terminals were added in the late 1940s, the demand for toll reductions faded as an active rallying cry. Yet the authority remained alert to the need to emphasize that its reserves would always be hard-pressed to meet the region's growing demands for self-supporting facilities. "The task of keeping pace," the agency proclaimed in 1950, "is a continuing one." Projects already underway and those still on the drawing board demanded that the authority maintain a "sound financial position," the agency warned in 1953, for "growing requirements . . . may call for an expenditure of some $550,000,000 of capital funds in the next ten years."[69]

In the language of the Hudson Dispatch, the Port Authority had become a "giant operator,"[70] and the efforts of the 1940s would, its officials hoped, be only a prelude to more vigorous activities in the decades ahead.

From the perspective of our more general interests, these activities illustrate a number of important themes: leaders of large and "profitable" public enterprises have substantial discretion in choosing programs and timing their projects; these leaders' views of the proper goals of their agencies are crucial in determining how they respond to "market demand" and how they shape it; public authorities have great advantages, in comparison with local general-purpose governments, in their ability to concentrate resources on specific developmental projects; conflicts in priorities and territorial influence among public officials combine with public demand in shaping government action; new public projects, in this case the Lincoln Tunnel and then the bus terminal, have impacts that extend outward, affecting transportation and residential patterns, and then molding the need and opportunity for future development projects.

[67] Port of New York Authority, Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952 (New York: 1953), p. 36; Port of New York Authority, Metropolitan Transportation: 1980 (New York: 1963), Chapter 20.

[68] The quotation is from "Port Authority Report," editorial, New York Times, August 13, 1946; cf. the laudatory comments on the bus terminal and its benefits in "The Port Authority at 30," editorial, New York Times, April 30, 1951, and "New York Port Authority's 30 Years of Achievement," editorial, Courier-Post (Camden, N.J.), May 1, 1951. A decade after the terminal opened, increased traffic led the authority to undertake a $30 million expansion of the terminal, which it said would save five minutes or more in commuting time. The new plan generated another round of media applause. The article in the Sunday News placed particular emphasis on the nexus between improvements in transport terminals and suburban growth. "Over the next six months, more than 91,000 commuters from Bergen and Passaic, Hudson, Essex, Union Counties and points west will be 'moved closer' to New York," the article announced. "Real estate men, advertising suburban dream houses as '30 minutes from New York,' will be able to claim 25 minutes, or 20." Douglas Sefton, "Eureka! N.J. Commuters Nearing a Utopian State," Sunday News, March 25, 1962.

[69] Port Authority, Twenty-Ninth Annual Report: 1949, p. 116; Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952, p. 67.

[70] "Port Authority in 25 Years Becomes Giant Operator," editorial, Hudson Dispatch, April 30, 1946.

Regional Arteries That "Fire the Mind"

Relations among the highway-oriented agencies have not always been free from conflict, as the bus terminal case indicates. By the mid-1950s, however, all major elements of the highway coalition were deeply involved in a cooperative program that would demand close contact for the next decade, and would significantly alter the region's transportation system. Initiated with a study by Moses's Triborough Authority and the Port Authority in 1954, the program also required major financing and planning contributions by federal and state highway agencies and by other public authorities in the region. Ten years later, the coalition could look on the results with satisfaction: the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge joining Staten Island and Long Island; the Throgs Neck Bridge between the Bronx and Queens; a second deck on the George Washington Bridge; new expressways in Bergen County, Staten Island, and New York City; and extensions of the New Jersey Turnpike and the New Jersey Highway Authority's Garden State Parkway.

During the first half-dozen years after the end of World War II, vehicular traffic on the region's major highway arteries nearly doubled, with especially large increases recorded on Triborough's bridges and tunnels to Manhattan and on the Port Authority's trans-Hudson crossings. The usual response of the highway organizations was to expand facilities incrementally to meet demand—witness the Port Authority's 1951 decision to add a third tube to the Lincoln Tunnel, to facilitate traffic pouring into Manhattan. Coordination among the region's agencies tended to be limited to those involved with particular segments of the road network, and relationships between the Port Authority and Moses were often strained.[71]

The early initiative in developing a more comprehensive and cooperative approach to highway planning was taken by the Port Authority. In a series of studies of traffic patterns in the early 1950s, the authority noted that an increasing proportion of trans-Hudson automobile trips did not begin or end in Manhattan. It concluded that detailed studies were needed of highway arteries that would bypass the Manhattan central business district, and asked the Triborough Authority to join in such studies. Moses agreed in late 1953, and after a year's study the two agencies released a report in January 1955 proposing several major additions to the highway network.

In terms of their expected impact on the region, the most important of these was the Narrows Bridge, connecting Staten Island—New York City's borough of Richmond—to Brooklyn and the rest of Long Island. The report anticipated that as a result of this bridge Staten Island, "the last large undeveloped area adjacent to Manhattan, would enjoy a significant economic improvement." Population would be "at least tripled" by 1975, and the development of the borough "would be integrated with the expanding economy of

[71] Moses was immersed in a great variety of enterprises, many dating from the 1920s and 1930s, which necessarily brought him into conflict with other agencies and officials. The "necessity" was caused in part by differences in organizational goals and perspectives, and in part by Moses's acerbic style of public discussion. Conflicts with the PNYA included the bus terminal case (where Moses was acting in part in his role as member of the City Planning Commission), and the question in the late 1940s whether the PNYA or a separate airport authority should develop regional airports east of the Hudson (Moses preferring the latter). On the airport conflict, see Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," pp. 143–197.

New Jersey and Long Island." Moreover, more than seven million vehicles would be diverted from the streets of Manhattan.

Other projects to be undertaken by the two authorities were the lower deck of the George Washington Bridge (by the Port Authority) and Throgs Neck Bridge (by Triborough). In addition, negotiations with other agencies led to simultaneous announcements of several related projects: the Garden State Parkway and the New Jersey Turnpike authorities would provide $85 million to extend their roads north to help provide bypass routes around Manhattan; and New Jersey's state highway department would collaborate with the Port Authority in financing and constructing a new expressway across Bergen County to the George Washington Bridge. Federal and state funds, the report suggested, might also provide an expressway across Staten Island and two express highways through Manhattan. The Port Authority and Triborough anticipated spending nearly $400 million of their own funds on the projects; the other agencies would contribute another $200 million or more. The report noted that if necessary approvals were granted "without delay," the three bridge projects could be opened to traffic in five years—by January 1, 1960.[72]

Once an affluent public authority announced that it would build a major highway facility, one might predict—in the heyday of road building—that the task would certainly, and promptly, be accomplished. The agency's financial independence, and the fact that its proposed actions appeared consistent with public needs for better arterial highways, gave assurance of success. Moreover, a successful outcome could be anticipated with greater confidence when the sponsors were two prominent authorities who had joined forces, and when their plans have attracted support from regional spokesmen. Indeed, initial reactions to the announced program, particularly among the news media, made it clear that the two agencies had scored an early public relations success. The program was acclaimed as "awe-inspiring" and "monumental," as a "spectacular" plan that would open "new vistas for the planning and development of the New York metropolitan area." "Fortunately," one major newspaper editorialized, "we have men . . . who can understand problems of such magnitude . . . and work them out while the rest of us gasp with awe."[73]

In a complex political environment, however, even spectacular projects with well-heeled sponsors can be derailed. The evolution of the Narrows Bridge project underscores the important role of leadership skills in major regional efforts. The Narrows Bridge program also shows how personal and organizational motives, as well as financial independence, are important factors distinct from "public demand" for new facilities.

[72] PNYA and TBTA, Joint Study of Arterial Facilities (New York: January 1955). The quotations in the text are on pp. 7, 21 and 25.

[73] The quoted comments are, respectively, from "Welding the Metropolitan Region," editorial, New York Herald Tribune, January 17, 1955; "Staggering Plans," editorial, Paterson News, January 18, 1955; "New Bridge-Building Plans," editorial, New York Times, January 17, 1955; untitled editorial, Bergen Evening Record, January 17, 1955; these and other editorials on the announced program are reprinted in Port Authority, Annual Report: 1954, pp. 14–15. New Jersey's Governor Robert Meyner and other political and business leaders also provided early endorsements. Before the authorities' public announcement, their officials had briefed the press, business groups, and public officials at extensive meetings in New York City, Bergen County, and Trenton.

The main points regarding the Narrows project can be made briefly:

1. A bridge or tunnel across the Narrows had been under consideration since the early 1900s, and New York City's governing body had approved a toll tunnel in 1929, voting an initial appropriation for design work. Yet no crossing was built for another twenty-five years, the major obstacles being technical and political complexity, as well as money. The channel was more than 7,000 feet, requiring a bridge center span longer than any yet constructed. Also, a bridge would have to be high enough for large ocean vessels to pass underneath. And there were thousands of residents in the path of bridge approaches in Brooklyn. The costs and technical problems involved in a tunnel under the deep channel were even greater.

2. The challenge of building a bridge across the Narrows was, however, an attractive prospect to Moses, for it would be a crowning jewel for the many prominent projects with which he had been associated. This would be "the longest suspension bridge in the world, and the tallest," Moses exclaimed; "it will be the biggest bridge, the highest bridge, and the bridge with greatest clearance." Struck with the personal, organizational, and regional benefits which could flow from "the most important single piece of arterial construction in the world," Moses had obtained necessary approval from the federal government in 1949 to build it as a Triborough Authority project. The estimated cost was far beyond Triborough's immediate financial capacity, however, and as of 1954, it seemed doubtful that the authority could undertake the project for at least another ten years.[74]

3. At this juncture, collaboration with the Port Authority seemed particularly attractive to Moses and his aides, as the bistate agency had the funds needed to begin construction at once. An agreement was worked out by the end of 1954, whereby the Port Authority would construct and finance the bridge, Triborough would operate it, and—when its financial resources from other bridges and tunnels permitted—Triborough would buy the Narrows bridge from the Port Authority.

The advantages of this joint arrangement were hardly one-sided, however. While enhancing Moses's prestige, stimulating development on Staten Island, and reducing travel time between Long Island and New Jersey, immediate action on a Narrows Bridge also promised several specific benefits for the Port Authority. The bridge would divert motor vehicles from the Holland Tunnel, thus allaying criticism of the authority for failure to provide more trans-Hudson facilities. The new crossing also would reduce traffic congestion in Manhattan, which promised to generate support for the Authority from the media and civic groups in Manhattan. Moreover, the project would improve the financial condition of the Port Authority's three Staten Island bridges,

[74] Quoted in William Randolph Hearst, Jr., "To Speed Traffic Through City: Main Points in Moses Program," New York Journal American, December 10, 1954. In the early 1950s, the Triborough Authority's income flow and uncommitted borrowing capacity were not as large as the Port Authority's; adding both the Narrows Bridge and the Throgs Neck Bridge in 1955 would have overtaxed its borrowing capability. Later, as Triborough's toll revenues steadily rose, Moses's agency took full financial responsibility for the giant span.

Caro's discussion provides more detail on some aspects of the joint study negotiations; see Caro, The Power Broker, pp. 921–930. Our review of the evidence, however, suggests that Caro assigns too much credit to Moses, and too little to the Port Authority's staff, in his discussion of who took the initiative in proposing a joint study, and how the detailed plans were developed.

which had operated in the red for most of the past twenty-five years. The bridge would also absorb funds that otherwise might lie idle, opening the agency to criticism for maintaining high automobile tolls and failing to use its "excess" funds to solve the growing rail transit problem.

4. The decision of the two authorities in early 1955 to allocate funds for the Narrows span did not ensure that a bridge would actually be built. The most difficult problem was to convince the New York City Board of Estimate to authorize construction of the approaches through residential sections of Brooklyn. Vehement opposition from local residents and their elected representatives led to continuing delays in 1955, 1956, and 1957. Construction was postponed, Moses later recalled, as "opponents sought by distortion of facts, appeals to prejudice, . . . and almost incredible personal vituperation to maim or kill the project. These opponents never rested. They appeared at every forum and in every tribunal." At one Board of Estimate hearing, the critics, "with jeers, cat-calls, and billingsgate, were allowed to go on until two o'clock the next morning. . . . No rule of debate was observed. We were treated as if we were speculators asking for a franchise to build a private toll bridge."[75]

Moses led the counterattack, arguing that unless the city gave prompt approval, Triborough would drop the arterial projects. Moreover, Moses doubted that he could then be of any use to New York City as its general coordinator of highway construction (a separate post he had held since 1946), since he would not "be able to speak with any authority or any expectation of support" from the city administration. Moses found it "hard to believe that New York City under its present Mayor will go on notice as not having the imagination and guts to take advantage of funds largely from other sources."[76]

Final approval was at last obtained from the Board of Estimate at the end of 1958, ground was broken in 1959, and in November 1964 the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge was opened to traffic—by Triborough, which had now become affluent enough to assume complete responsibility for the span. During the next six years, the population of Staten Island increased by more than 30 percent, to nearly 300,000. Stimulated by improved access to the rest of New York City and Long Island, land values on Staten Island rose from $1,500 per undeveloped acre in 1960 to $20,000 in 1964 and $80,000 in 1971.[77] Moreover, by making Staten Island more accessible, and thus facilitating construction of the relatively inexpensive new housing discussed in Chapter Three, the Narrows Bridge hastened the flow of white middle-and working-class families out of the city's older sections.

As to the bridge itself, the Triborough Authority's gross income from the crossing was $9.5 million for the first twelve months of operation, and revenues increased steadily thereafter. The last word on its esthetic contribution

[75] Robert Moses, Public Works: A Dangerous Trade (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970), p. 226.

[76] That is, from the two authorities and from federal and state highway programs. The quotations are from Moses's letters to Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., in 1955, reprinted in Moses, Public Works, p. 229.

[77] See Port Authority, Staten Island: A Study of Its Resources and Their Development (New York: Staten Island Chamber of Commerce, January 1971); and Robert D. McFadden, "Verrazano-Narrows Bridge: 'A Two-Faced Woman,'" New York Times, December 6, 1970.

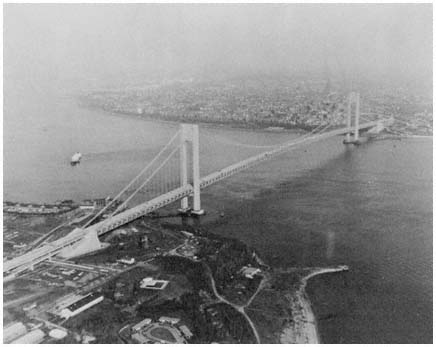

The magnificent Verrazano-Narrows Bridge connecting Brooklyn

and Staten Island provided an essential link

in the highway system forged by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority,

the Port Authority, and other highway agencies.

Credit: Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority

to the region goes to Robert Moses, who retired soon after completion of this final monument to his ambition and his genius:

It is a structure of superlatives, a creation of imagination, art, architecture and engineering. Its scale, magnitude and beauty will fire the mind of every stranger and bring a tear to every returning native eye.[78]

[78] Robert Moses, remarks at the cable-spinning ceremony at the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, March 7, 1963. The bridge design was the work of the great Swiss bridge designer, Othmar Ammann, who was also responsible for the George Washington Bridge three decades earlier.