Berlin, Winter 1887–88

In the spring of 1887 when Corinth left Paris, he had completed more than a decade of academic study. He might have looked back on this period with a greater sense of accomplishment had he been able to add to his bronze medal for The Conspiracy a similar token of recognition for his years at Julian's. As it was, he returned to East Prussia with little more to show than a few studies of the nude model. The knowledge that he was approaching his thirtieth birthday must have weighed heavily on him. Fortunately, he did not suspect that thirteen years of search and experimentation still lay ahead.

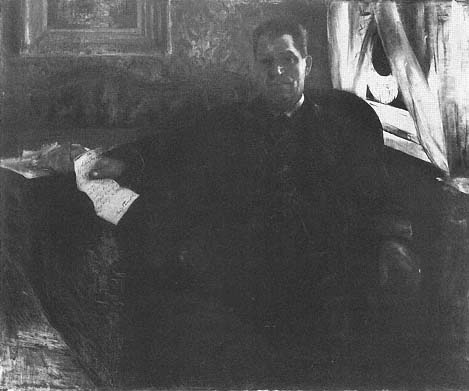

Except for a brief visit to the Baltic seacoast, Corinth spent the summer of 1887 in Königsberg. Of the five paintings he completed at this time the portrait of his father (Fig. 20) is the most important. In it once again he depicted a figure in a sunlit interior, except that, as in the portrait of 1883 (see Plate 1), Franz Heinrich does not really occupy that interior but sits in front of it. Daylight, entering through the window at the right, fills the room with a subtle glow, accentuates the structure of the sitter's face, and touches details with a sparkle of bright color. The pale blue of the letter Franz Heinrich holds in his right hand echoes the white and blue of the curtains and the windowpane. Patches of red and yellow enliven the dull green of the tablecloth. Although this portrait was painted only four years after the Munich portrait, Franz Heinrich looks not only markedly older but also much more frail. As in the earlier portrait, the posture is casual, but it fails to convey the same impression of comfort and ease. Instead, Corinth's father is seated rather stiffly in the armchair and seems unable to support his weight without effort. The face is taut, the expression of the eyes weary. Corinth must have begun the portrait shortly after his return from Paris, for at the end of July the painting was included in an exhibition organized by the Berlin Artists' Association at the Glass Palace in Berlin. It was moderately successful at best. According to Corinth, some of the critics "thoroughly flogged" him.[1]

Figure 20

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth with a Letter , 1887.

Oil on canvas, 87 × 105 cm, B.-C. 51. Museum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg.

Photo: WS-Meisterphoto Wolfram Schmidt.

Despite this inauspicious reception, in October Corinth went to Berlin to pursue opportunities that by his own account were luring artists to the city:

Berlin was thriving at the time. The population was expanding, and a strong interest in art was just beginning to develop. One could find plenty of newly rich bankers who were willing to support the arts, and it was easy for ambitious, capable, and truly talented painters to establish art schools of their own. This was the reason many young artists moved from Munich to Berlin, and if one was lucky enough to be a foreigner, one's fortune was already made.[2]

By the time Corinth arrived, Berlin had already experienced more than a decade of astonishing growth. After 1871 this old seat of the Hohenzollerns, suddenly the capital of a unified German Empire, was transformed into a major metropolis. With the city's intensified economic development, commerce and industry grew at a dizzying rate. As corporations and banks multiplied, immense private fortunes were created. Newcomers arrived by the thousands. In only nine years—from 1864 to 1875—the city's population almost doubled, passing the one-million mark. By 1885 it had increased to nearly a million and a half.[3] In 1872 alone no fewer than forty new construction firms began to operate,[4] gradually pushing the city's perimeter further west; mansions near the Tiergarten soon vied in opulence with the splendid apartment buildings along the Kurfürstendamm.

The visual arts in Berlin were dominated during these years by the Berlin Academy and its influential director Anton von Werner. Werner, still remembered for his photographically accurate depictions of scenes from the Franco-Prussian War, was only thirty-two when he became director of the academy in 1875. From 1887 to 1895 he also served as president of the Berlin Artists' Association, whose members controlled the annual academy-sponsored exhibitions. Until 1885 these exhibitions were predominantly local; not until the academy's centennial anniversary exhibition in 1886 were artists from other German cities and from abroad encouraged to participate in larger numbers. The 1886 exhibition, intended to propel Berlin into the intellectual and artistic community of older, more illustrious European capitals, turned out to be the nation's cultural event of the year and a matter of great national pride. Die Kunst für Alle , Germany's leading art journal at the time, devoted ten consecutive biweekly issues to the exhibition.[5] In addition to the German contingent, artists from nine foreign countries exhibited in the newly built Glass Palace—England, Belgium, Holland, the Scandinavian countries, Italy, Spain, and Russia. France—not unexpectedly—chose not to participate.

While the leading academicians reaped their customary accolades and medals from the exhibition, younger, innovative artists did not go unnoticed. Among the Germans was Max Liebermann, who exhibited three paintings: The Old Men's Home in Amsterdam (1880–1881; Collection Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt), Girls from the Amsterdam Orphanage in a Garden (1885; Kunsthalle, Hamburg), and Saying Grace (1886; private collection). The first two paintings were generally well received. The third elicited mixed reactions. Most critics applauded the sincerity of the religious sentiment portrayed but found Liebermann's unidealized models and their humble milieu offensive.

The same criticism was directed at two religious paintings submitted by Fritz von Uhde, Come, Lord Jesus, Be Our Guest (1885; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie), and The Last Supper (1886; present location unknown). But since these paintings made up in anecdotal interest whatever the figures lacked in conventional "beauty of form," Uhde received on the whole a more generous recognition than Liebermann.[6]

The academy exhibition of the following year, to which Corinth sent the recently completed portrait of his father, included few foreign artists. Moreover, most of the established German academicians, apparently not yet recovered from the previous year's exhibition, refrained from showing. A reviewer noted instead a marked increase in the number of younger German artists preoccupied with the same pictorial problem: plein air.[7] Liebermann was represented with his paintings Beer Garden in Munich (1884; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and Women Spinning (1880; painting lost) and Uhde with his first biblical scene in an outdoor setting, The Sermon on the Mount (1884; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest). The exhibition's succès de scandale belonged to Max Klinger, whose monumental painting The Judgment of Paris (1886–1887; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) elicited a wave of hostile criticism. Klinger's uncompromising naturalism in depicting the three nude goddesses led the Kreuzzeitung to publish a stern editorial on the decay of morals. Critics derided as the ultimate proof of his folly his efforts to fuse the picture and its immediate environment into a Gesamtkunstwerk by setting the huge canvas into an elaborate polychrome sculptured frame.[8]

The battle for modern art in Berlin was waged less vociferously in the galleries of two private dealers, Eduard Schulte and Fritz Gurlitt. Schulte, who in 1885 had taken over the former Salon Lepke on Unter den Linden, generally followed the accepted academic trend, though he did not exclude controversial artists altogether. In the winter of 1887–88, besides a number of portraits by Lenbach, he exhibited a group of paintings by Arnold Böcklin, an artist who had only begun to receive some recognition. Gurlitt was more enterprising. Since opening his gallery in 1880, he had displayed the work of painters from throughout Germany. He was among the first to exhibit works by Hans von Marées and Hans Thoma. His gallery was also the only place in Berlin where paintings by the French Impressionists could be seen. In October 1883 Gurlitt exhibited the small but exquisite collection assembled by Carl and Felicie Bernstein, consisting of works by Manet, Monet, Sisley, Pissarro, Gonzalez, and Morisot. Shortly thereafter he showed a selection of

works by Pissarro, Renoir, and Degas sponsored by the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Gurlitt's exhibitions inspired the young French Symbolist poet and critic Jules Laforgue, who from 1881 to 1886 lived primarily in Berlin, serving as a reader to the German empress Augusta, to write one of the earliest and most incisive analyses of Impressionism.[9]

The artistic milieu Corinth encountered when he arrived in Berlin in October 1887 thus offered the old and established as well as the new. It is not known whether he had visited the Berlin Academy exhibition at the Glass Palace during the summer, but because the portrait of his father was shown there, he was probably aware of the growing reputation of such artists as Liebermann, Uhde, and Klinger. Corinth himself, however, was not one to eagerly follow the avant-garde. His continuing image of himself as a student is suggested by his later confession that he felt "intimidated" on arriving in Berlin; aside from a "pent-up ambition to learn something," he had neither the "courage nor the determination to take any adventurous risks."[10]

Indeed, Corinth's Berlin output, dominated by drawings of male and female nudes, is little more than a continuation of his student work from Paris. Most of these drawings originated at Der Nasse Lappen (The Wet Rag), a private drawing club he joined soon after his arrival. Der Nasse Lappen was founded by Carl Steffeck, who had taught at the Berlin Academy from 1859 until his departure for the academy in Königsberg in 1880. Members of the club met in the evenings to draw after the live model. In the late 1880s the artists who took part in this Abendakt , in a studio on Potsdamer Strasse, included the painters Carl Friedrich Koch, Paul Souchay, and Adolf Schlabitz and the sculptor Max Klein. The art historian Heinrich Weizsäcker also occasionally joined the drawing sessions.[11] Corinth soon got to know the most prominent member of the group, Karl Stauffer-Bern, well enough to visit him in his studio on Klopstockstrasse, and the Swiss artist apparently introduced him at this time to Max Klinger and to the Berlin painter Walter Leistikow.

Although Karl Stauffer (1857–1891), a native of Bern, was only a year older than Corinth, he had already made a name for himself as a portraitist among the newly rich of Berlin. He also enjoyed the special favor and protection of Anton von Werner, who had helped him to secure his first important portrait commissions, which in due course included the portrait of the emperor's surgeon, Dr. von Lauer, and a portrait of the emperor himself. Adolph von Menzel, whose portrait Stauffer-Bern etched in 1885, was so impressed with the young man's talent that he frequently invited him to his home for dinner, an honor he bestowed on only a few. It was the "foreigner" Karl Stauffer-Bern

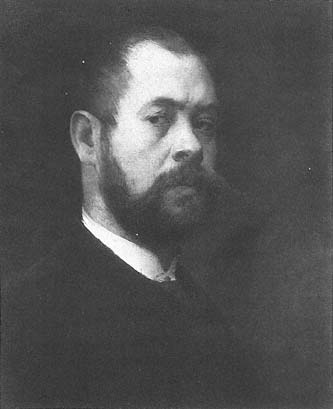

Figure 21

Karl Stauffer-Bern,

Self-Portrait , c. 1885.

Etching, 35 × 22 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern (S 10692).

whom Corinth clearly had in mind when he wrote of those "ambitious, capable, and truly talented painters" who had succeeded in launching profitable teaching careers in the nation's new capital. For in addition to pursuing his creative work, Stauffer-Bern both directed the portrait class of the Berlin Society of Women Artists and Friends of the Arts, whose students in 1885 included Käthe Kollwitz, then eighteen years old, and maintained a small ladies' academy of his own.[12]

Stauffer-Bern must have embodied for Corinth the success he himself was striving for. He had reason to believe the goal within his reach, moreover, for Stauffer-Bern's work was based on formal principles that Corinth was in the process of making his own. Both artists had been trained by Löfftz at the academy in Munich. Stauffer-Bern's reputation today rests primarily on his prints, although he made no more than thirty-seven.[13] His portrait etchings, such as the Self-Portrait (Fig. 21) of about 1885, convey the sitter's presence with striking immediacy, a quality he considered indispensable: "In my portraits I am not concerned with snappy execution or coloristic appeal but rather with the mathematically precise reproduction of form and the most delicate modeling, . . . because a portrait must be above all so lifelike that one is startled by it."[14]

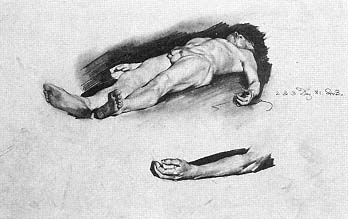

When drawing the nude model, which he considered the "painter's alphabet" and "the foundation of all art," Stauffer-Bern was guided by the same desire "to reproduce the exquisite details of nature, to penetrate the secrets of appearances, and to become a master of what he could see."[15] As a result, his drawings primarily document visual facts, although the sculptural plasticity of his figures also has expressive power (Fig. 22). Weizsäcker considered

Figure 22

Karl Stauffer-Bern, Recumbent Male Nude ,

1881. Pencil, 25.0 × 39.5 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern (A 3461).

Stauffer-Bern's drawings among the best anywhere: "What a joy it was to leaf through the portfolios and sketchbooks in his studio at one's leisure! How . . . the most delicate vibration of form was observed, with what intelligence and at the same time with what energy, often after several new beginnings, until the image had been seized."[16]

Since he was not satisfied with the soft gradations obtainable with the etching needle alone, Stauffer-Bern frequently reworked his plates with the burin to achieve more emphatic contrasts in value. Emulating the Italian engravers of the fifteenth century, he applied the burin so that the hatchings do not follow the round forms of the human body but create shadows with a network of straight, precisely drawn parallel lines.

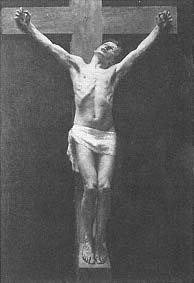

In addition to portraits and nudes, Stauffer-Bern favored religious compositions. A painting representing Christ in the house of Simon the Pharisee was to have been one of his major works. Begun in 1884 on a large scale—the canvas measured approximately eight by sixteen feet and was projected to contain seventeen life-size figures—it was never completed. From 1886 to 1887 he worked on a dead Christ motif inspired by Holbein's picture in Basel, and during the winter of 1887 he painted the Crucified Christ (Fig. 23), an impeccable anatomical depiction of the model, whose brightly illuminated body is set off against a dark ground. Sixteen years later Corinth wrote that this painting was like an "oasis in the desert" for him during that winter, and although by the time he made the statement he had begun to reject Stauffer-Bern's conception as too literal, he professed continued respect for the Swiss artist as a "master of form," emphasizing that the nude human figure could be considered (as he paraphrased Stauffer-Bern himself) the "Latin of painting."[17]

Figure 23

Karl Stauffer-Bern, Crucified Christ ,

1887. Oil on canvas, 247 × 168 cm.

Kunstmuseum Bern.

Corinth's contact with Stauffer-Bern, however, was short-lived. Stauffer-Bern tended to be impulsive; he loved to theorize, but without reflecting. According to his biographer Georg Wolf, "Clichés flowed effortlessly into his speech. He preached about art and artistry, demonstrated mature judgment alongside sky-high naïveté, and developed plans on a grand scale for an entire generation of Raphaels and Buonarrotis."[18] Similarly high-flown ideas apparently ended Stauffer-Bern's friendship with Corinth. When on Christmas Eve 1887 he tried to explain to Corinth over a bottle of wine his concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk that—like Klinger's—was to unite painting and sculpture, Corinth bluntly countered by quoting a well-known vulgar line from Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen and left.[19] The two men never saw each other again. In the spring of 1888 Stauffer-Bern left for Rome to devote himself entirely to the practice of sculpture. His unfortunate love affair with Lydia Welti-Escher, the wife of his influential Swiss patron, led in quick succession to his imprisonment and commitment to mental institutions in Rome and Florence and to his suicide at the age of thirty-three on January 24, 1891. Yet despite the brevity of their relationship, Stauffer-Bern had a decisive effect on Corinth's development and continued to influence him for several years. His example encouraged Corinth's own desire to become a "master of form," and the Crucified Christ remained proof that this mastery could be put effectively to the service of a major theme.

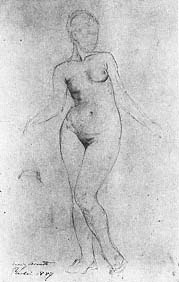

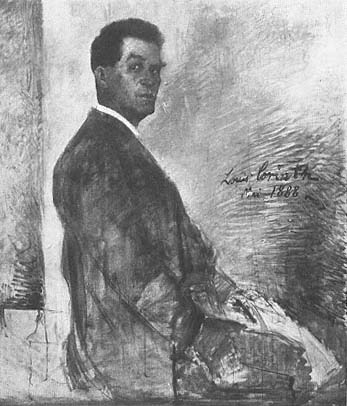

Figure 24

Lovis Corinth, Standing Female

Nude , 1887. Pencil, 52.8 × 34.5 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR).

Figure 25

Lovis Corinth, Standing Female

Nude , 1887–1888. Pencil,

44.7 × 29.5 cm.

Kunsthalle Bremen.

Corinth's Berlin drawings in particular indicate the extent to which he emulated Stauffer-Bern's concept of form. Although relatively few examples have survived, he apparently worked extensively at drawing during the winter of 1887–88. A mise en place sketch (Fig. 24) in the idealizing French manner was probably done soon after Corinth arrived in Berlin. Sweeping reinforced contours define the stereometrically simplified body while a gently swaying line of action proceeds from the model's neck through the navel and pubic area to the inner contour of the left leg. Like Bouguereau's Venus (see Fig. 14), the figure is eight heads high, with the upper and lower portions of the body containing four heads each. By comparison, several drawings in a sketchbook now in the Kunsthalle in Bremen illustrate how Corinth adopted Stauffer-Bern's emphasis on plasticity of form and painstaking verisimilitude. The drawing of a standing female nude (Fig. 25) on folio 3 recto, for example, is superior to any of Corinth's earlier life drawings in accuracy of rendering. The modeling, contained by smooth contour lines, recalls the parallel hatchings in Stauffer-Bern's prints and makes the supple flesh palpable. The woman, directly observed, conveys the sense of a real, living presence. In several drawings in the Bremen sketchbook the anatomical depiction of the model is complemented by careful studies of detail; in others the sculptural clarity of the figure is enhanced by conspicuous shadows, as in similar drawings by Stauffer-Bern.

Figure 26

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude ,

1887–1888. Pencil, 29.5 × 44.7 cm.

Kunsthalle Bremen.

Although most of the drawings in the Bremen sketchbook display the same remarkable naturalism, Corinth did not abandon the idealizing tendencies of his French teacher entirely. On the contrary, as his command of life drawing grew, he could not only express the visual data manifested in the model but also achieve a more sophisticated grasp of conceptualized form. His drawing of a reclining female nude (Fig. 26) on folio 28 recto follows the practice of Bouguereau by combining the realistic head of a modern woman with a graceful, idealized body. A transparent chiaroscuro accentuates the soft forms of the model, and delicate flowing contours emphasize the body's sensuousness.

Corinth's works during the Berlin winter culminated in at least two paintings, each depicting a female nude. The smaller of the two (B.-C. 54), dated 1888, is based on a drawing in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg;[20] the other (Fig. 27) bears the date 1887 and was clearly preceded by drawings like the one shown in Figure 26. The 1887 painting is the more finished and more ambitious of the two. The model is shown life-size, reclining on a bed of silky cushions and sheets, her back turned seductively toward the viewer. Both paintings further elaborate Corinth's drawings from life; both are exercises, efforts to endow visual perception with concrete pictorial form. The meticulous and richly nuanced modeling of the flesh parts suggests that these works are those of which Corinth, remembering Bouguereau's criticism of his draftsmanship, later wrote: "I seriously tried to capture the forms by working from the live model; in my pictures there was not to be a speck that was not rigorously studied."[21]

The same disciplined brushwork is seen in the Self-Portrait (Fig. 28) from the winter of 1887–88. Like Stauffer-Bern's portrait etchings, the painting projects the artist's physical presence with "startling" immediacy. Although this

Figure 27

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude , 1887. Oil on canvas, 65 × 175 cm,

B.-C. 53. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

effect results partly from the quizzical, apprehensive gaze, it is reinforced by the tangible life-size head emerging from the undifferentiated pictorial ground. The meticulous modeling is in keeping with Stauffer-Bern's precept that "mathematically precise reproduction of form" is the basis of other, more expressive, qualities in a given portrait. Indeed, more than twenty years later Corinth, commenting on the art of portraiture, restated the precept in his own teaching manual with remarkable accuracy:

A specific individual has here been portrayed, and the first requirement is verisimilitude. Perhaps some will say that in a work of art other qualities could be considered more important, since in most cases only a very few will know the sitter by face. However, such other affective qualities as immediacy of expression and liveliness of conception are only the inevitable result of verisimilitude.[22]

Corinth's awareness of his increasing technical proficiency during the winter of 1887–88 is reflected, at least indirectly, in his decision that his name henceforth should be Lovis. For some time he had been signing his works in capital letters, replacing the U in his first name with the less conventional roman V . He now began using the v for the lower case spelling of his name as well, adopting Lovis as his professional name; legally, however, his name remained unchanged.

In February 1888 Lovis Corinth participated again in an exhibition organized by the Berlin Artists' Association. Two of the paintings he showed, the portrait of a young architect named Tietz, painted the year before, and a picture entitled Hospital Women at Their Morning Prayer , were either destroyed by Corinth or overpainted, and nothing is known about them except what can be

Figure 28

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1887–1888. Oil on canvas,

53.5 × 43.0 cm, B.-C. 49.

Sammlung Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt.

gleaned from a reviewer's brief remarks critical of the forced facial expressions in both works. The third painting was Corinth's seasoned prizewinner The Conspiracy , which once again drew favorable comments.[23]

Corinth's further efforts to establish himself in Berlin were cut short when his father called him home at Easter time. As the portrait from the previous summer suggests, Franz Heinrich was ailing, and the wish to have his son near him was most likely prompted by a further deterioration of his health.

Figure 29

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth , 1888.

Oil on canvas, 118 × 100 cm, B.-C. 56.

Private collection.