PART THREE—

ALTERED STATES:

TRANSFORMING MEDIA

Seventeen—

The Superhero with a Thousand Faces:

Visual Narratives on Film and Paper

Luca Somigli

The last decade has brought about a somewhat unexpected renaissance of the visual narrative medium known as "the comics,"[1] which toward the end of the seventies seemed to be on its last legs.[2] The comics industry has been shaken by a new awareness of the artistic potential of the medium, facilitated by new systems of production and distribution (especially the independent comics companies and the direct sales system) that have given never-before-experienced creative freedom to writers and artists alike. Yet, comics remain a less-than-becoming medium for serious scholars. Joseph Witek, whose work Comic Books as History is one of the few important attempts to examine comics from a theoretically informed perspective, concludes his introduction with a rather candid acknowledgment: "The emergence of comic books as a respectable literary form [with the works of practitioners like Art Spiegelman and Harvey Pekar] in the 1980s is unlooked for, given the long decades of cultural scorn and active social repression, but the potential has always existed for comic books to present the same kind of narratives as other verbal and pictorial media" (11). The perception that comics are an inferior narrative medium has hindered not only their own development, as Witek suggests, but also their relationship with those media, such as cinema, that from time to time have turned to them for characters and concepts. Although in the thirties and forties many popular characters, including Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Batman, and Captain America, made the transition from paper to film, they were usually relegated to Saturday matinee serials, rather than featured in major productions. It is only recently, with the success of films like Superman (1978) and Batman (1988) and their sequels, that Hollywood has developed a real interest in the comics as a source of inspiration.[3]

I wish to discuss how cinema and the comics have had to solve similar

problems, given their common nature as visual media. Then I will articulate the relationship between the two media in terms of a model that rejects both the notion of remake and that of adaptation in favor of that of myth.

Cinema and the Comics:

Two Visual Languages

March 22, 1895: the Lumière brothers project their first films to a private audience. February 16, 1896: the "Yellow Kid," the first successful comic strip character, makes his first appearance in the New York newspaper World .[4] Born less than one year apart, the two narrative media made possible by the advent of the age of mechanical reproduction then went on to widely different futures. Cinema was to become the only medium dependent upon the technological revolution of the last two centuries to be admitted into the hallowed halls of art (the "tenth muse," as it has been called), whereas the comics remained for most of their history the point at which "Art" turned her eyes with horror, the point of no return beyond which lies the realm of hopelessly and irredeemably "popular" culture. The appropriation of cinematographic techniques by comics artists has been often remarked upon.[5] Nevertheless, the relationship is not necessarily one-way. John Fell has pointed out that early filmmakers and comics artists were confronted with "common problems of space and time within the conventions of narrative exposition" (89), and that the comics developed a highly sophisticated language that in some cases anticipated cinematographic solutions to these common problems. For their part, a number of film directors, including Federico Fellini, Orson Welles, and George Lucas (Inge, xx) have acknowledged an interest in and even a debt to the comics.[6]

Cinema and the comics are both primarily visual languages. Comic writer and artist John Byrne has remarked recently that "good art will save a bad script, whereas good writing can do little to save bad art," a statement especially to the point in regards to recent mainstream comics (particularly the superhero genre) in which an increased aesthetic awareness on the part of artists has been accompanied by an almost opposite trend in plots. Both media construct a story through the juxtaposition of images, so that the relations established among them can convey the illusion of temporal and spatial development. Like cinema, a comic narrative is assembled through the succession of frames; however, whereas in film the quick succession of the frames can give the impression of actual movement, the comics have had to devise other solutions to represent movement and progression. As Daniele Barbieri explains in his excellent structural study of the comics medium, the panel itself is not simply an image frozen in time, but it can be used to represent a duration through a number of different techniques (use of motion lines, repetition of the image as with an overexposed pho-

tograph, particular arrangements of the balloons, and sound effects, etc.): "Therefore, we have one image—traditionally corresponding to one instant—within which there is a duration. With the comics, the panel no longer represents an instant , but a duration: just like cinema (230–31)."[7]

If we take this definition of the comic panel, perhaps we can establish a more useful comparison between it and the cinematographic shot as the basic unit of composition of the two media. In film, meaning is generated by the syntagmatic relation of the shots in a sequence: like the combinatory elements of articulated language, the shots are arranged along a space that is "linear and irreversible" (Barthes, 58), the previous shot preparing the viewer for a range of possibilities in the following one. To quote Roland Barthes again, "[E]ach term derives its value from its opposition to what precedes and what follows" (58). Likewise, the panels that compose the comic page, traditionally arranged for reading from left to right, from top to bottom, construct meaning by their relation to one another. However, this syntagmatic reading is paralleled by "a paradigmatic reading of inter-relationships among images on the same page" (Collins, 173), allowing for effects that are not available to cinema and that make up for the relatively static nature of the comics.

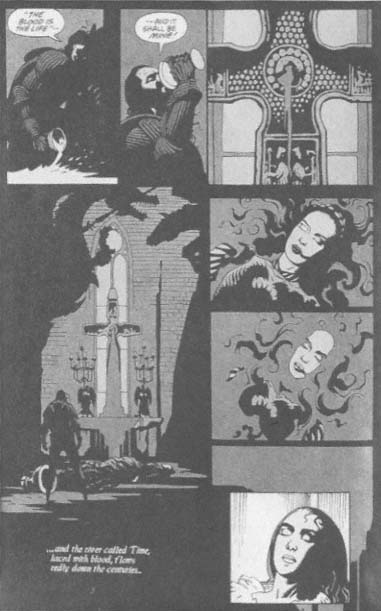

As an example, let us discuss a page of the comic book adaptation of Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula (1992), published by Topps Comics (story by Roy Thomas and art by Mike Mignola). The page reproduces the crucial scene in the frame story of Dracula's origins (so much for Bram Stoker's Dracula ). In the film, the count stabs the cross on the altar with his sword; from the gash in the wood blood starts pouring out, until it covers the whole floor of the church and submerges the body of Dracula's dead wife, Elisabeta.

The first striking element about the comic book adaptation is the page itself: the border that surrounds the panels is not white, as is common with most comics, but black. (See figure 37.) This technique can be used very effectively to connect the panels, as the borders are not as clearly demarcated. In particular, in the long panel on the bottom of the left half of the page the shadows of the gargoyles blend in with the darkness of the frame so that the latter seems to be an extension of the shadows of the church (this sense of continuity between panel and border is reinforced by the trickle of blood that reaches the edge of the page). Therefore, the smaller panels appear superimposed on this larger one, which comes to include the whole of the page.

The first two panels give a good example of how the illusion of movement can be created through static images. In the first, Dracula dips a cup in the holy water spilled in the previous page. In the next, he is shown raising the cup to his lips. In following the cup from the bottom half of the first panel to the top half of the second, the eye goes through the same

Figure 37.

The comic book transformation of Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula

offers imaginative "takes" on the film. Courtesy of Topps Comics.

movement as the cup lifted from the ground to the count's lips. The illusion of continuity and trajectory is reinforced by the little drops of water splashed in panel one in the direction of panel two.

The next panel presents a frontal close-up of the cross, out of which blood starts flowing. Now, in a syntagmatic reading of the sequence the successive panel is the long left-hand one mentioned above. Here, the "camera" pulls back to a long shot that reveals Dracula facing the cross, his wife lying dead on the steps of the altar on which the cross is mounted. Then follows a close-up of the dead woman's face. However, the third and fifth panel can also be read vertically (a reading encouraged by the vertical thrust of panel four, and by the fact that the following panel, panel six, is directly below five rather than next to it). Thus, the blood gushing out of the cross seems to be pouring directly over Elisabeta's face, partially covering it in panel six, and finally drowning it out in panel seven. In fact, by its very shape, panel seven continues the flow of blood that started four panels above: its top edge and part of its sides are straight lines, but instead of closing into a square, as with a regular panel, they taper into the shape of a dripping red strip of blood, eventually cut off by the edge of the page itself. The blood that in the film covered the whole screen here flows throughout the page, and beyond it. Finally, in a device that may be as close as comics can come to a lap dissolve, an eighth panel is superimposed on the seventh.[8] Through it, we are carried forward in the narrative outside the frame story and into 1897 London, but the panel itself is used to establish a clear link between the two parts of the narrative, since it represents Mina's face in roughly the same position as Elisabeta's in panel five. (As we know, in Coppola's version of the story Mina is a sort of reincarnation of Dracula's beloved wife.)

Although my analysis is concerned with one single page, I would like to point out that, as Witek has suggested, "[t]he largest perceptual unit of comic-book storytelling is the two page spread (20)."[9] In fact, in the first panel of the facing page the "camera" moves back to give a full shot of Mina in a washtub, her face in the same position as in the last panel of the previous page. Above her, Lucy pours water over her head, a gesture that looks back to both Dracula filling the cup with holy water and the blood pouring out of the cross on the opposite page.

Adaptations High and Low

Adaptations of films to comics such as the one discussed above are fairly common, and they show a degree of respect for the original comparable to that of the cinema for its literary sources. However, the translation of comics into films has usually entailed a much more cautious and critical approach on the part of the latter medium. This is to some extent due to

the nature of cinema itself. Drawing allows the comic artist a degree of freedom with the visual material that cinema can hardly match since, for better or worse, it must rely on human actors. The partial or total failure of films like Robert Altman's Popeye (1980) and Willard Huyck's Howard the Duck (1986) is symptomatic. When drawn by Val Mayerik, Howard is an anthropomorphic duck; in the film, he is just a guy in a duck suit.[10] However, even films based on comics centered on human characters can hardly be called "adaptations."

In a paper delivered at the 1992 Modern Language Association Convention in New York City, David Newman, one of the scriptwriters for the first three Superman films, began by emphasizing that a distinction must be made between remake and adaptation but then went on to argue that neither model was applicable to his own approach to translating Superman for the big screen. Rather, he approached Superman as "the most American myth." The use of the term "myth" is remarkable in view of its frequent application to the comics, to which we will turn in a moment. However, the distinction between remake and adaptation is also significant, and the rejection of both deserves some discussion. In an essay in this anthology, Robert Eberwein gives a good working definition of a remake: "A remake is a kind of reading or rereading of the original." In the "Preliminary Taxonomy" of remakes appended to the same essay, he writes: "Even more problematic, the taxonomy itself doesn't address the issue of adaptation: are there any films in the various categories that can claim a common non-cinematic source? If so, is it correct to call a film a remake or a new adaptation . . .?" As Eberwein makes clear, the crucial issue at stake when dealing with remakes and adaptations is that of the "original." In fact, the definition of the remake as (re)reading seems to me equally applicable to adaptation. What distinguishes the two is the relation between the new reading and the medium of the original: as the term suggests, an adaptation is not simply a matter of retelling a story. Rather, it entails a move from one medium to another and therefore the "adjustment" of the narrative to the expressive language of the target medium (to borrow a term from translation theory). In both cases, however, the existence of a source is assumed and even necessary to make the new work a remake or an adaptation. This observation is not as tautological as it may at first appear: it is obvious that there is some "source" for Newman's Superman, but it stands in a very different relation to the film than, say, E. M. Forster's novel does to Merchant and Ivory's A Room with a View .

This is the result of the differential relation that cinema bears to sources from other media. When drawing from canonized texts (in particular, socalled literary texts), from works firmly enshrined within the cultural tradition, the prime concern is faithfulness to the original, seen as a fixed entity complete in itself. A glaring example is Claude Chabrol's recent ad-

aptation of Madame Bovary (1991), in which whole descriptive passages were lifted out of Flaubert's novel and superimposed through a voice-over on images that actually clashed with them. In order to reproduce the original in the most integral way possible, the language of film was subordinated to that of the literary text. However, when the source is a work of "popular culture," the integrity of the original is not an issue.

As Lawrence Levine suggests in his study of the evolution of the idea of "culture" in America, the very notion of popular culture rests on the openness of the text to outside intervention. The many versions of the story of Count Dracula comprise an index of how elements of a popular narrative may become dissociated from their original source and thus undergo endless rearticulations (Coppola's version, for all its faithfulness to the letter of Bram Stoker's novel, takes remarkable liberties with it, the most significant being of course that Dracula comes to occupy the center of the stage.)[11] Even a film that follows fairly closely the plot of its comic strip source, Mike Hodges's Flash Gordon (1980), seems to have no problems with changing the background of the characters and transposing the action from the 1930s to the 1980s. Significantly, Nash and Ross (871) consider this film a remake of the 1936 Flash Gordon film serial (and a poor one, at that), rather than an adaptation of Alex Raymond's comic strip.

The issue of the status of the original is a central concern of translation theory, and the following comment on nineteenth century approaches to translation can help us understand what is at stake in this differential treatment of the original. According to Susan Bassnett-McGuire, two positions can be distinguished: "[T]he one establishing a hierarchical relationship in which the [source language] author acts as a feudal overlord exacting fealty from the translator, the other establishing a hierarchical relationship in which the translator is absolved from all responsibility to the inferior culture of the [source language] text" (4).

Comics, science fiction, mysteries, and so on belong to the inferior realm of popular culture: therefore, in "translating" them into another medium, what needs to be considered is not the integrity of the original, but that of the target medium, which to some extent elevates the status of the popular culture artifact to its own by adapting it. An a contrario proof of this is the fidelity of comic book adaptations of films: as a superior art form, the integrity of the film must be respected by the comic book. The opposite, of course, is not true. Newman argued quite frankly that the main problem with selling the concept of a Superman film to a producer was that of selling it as a "grown-up movie." The relation to its source had to be played down, and even disguised, so that the film could be cleansed of the unfavorable association that the source medium, the comics, carries with it. In a short article on Warren Beatty's Dick Tracy (1990), based on the character created by Chester Gould, Patricia Kowal attributed "the simplicity of the

story" to "its comic strip origin" (95). While this comment was not meant as a critique (Kowal is generally appreciative of the comic-like quality of the film), it brings out a commonly held belief that comics are simplistic, even naive, narratives that have little to offer more sophisticated media.

After all, cinema has been able to make its bid as a serious cultural medium by emphasizing its association with already canonized cultural formations. As narrative cinema developed in the direction of complex, realistic narratives centered on well-defined characters, all the instruments available to analyze a (by then) traditional literary form, the novel, could be brought to bear on it. There are indeed a number of structural similarities between prose fiction and narrative cinema; for instance, both types of narrative are limited in scope, developing, in Aristotelian fashion, through a beginning, a middle, and an end. The proximity between the two media was reinforced by theorizing cinema in ways that assimilated it to literature and in fact disguised its specific features: the auteur theory developed in the fifties by the Cahiers du cinéma school is only the culmination of that process. Ascribing the authorship of the film to the director denies the collaborative effort that goes into its making, but also makes it possible to see it as a homogeneous whole and to construct the critical discourse around it in terms of authorship, coherence of vision, an so on. In the comics, however, we can distinguish two patterns. Again the critics have often tended to approach the medium in terms of the individual genius: therefore, there has been an emphasis on figures like Winsor McCay, George Harriman, Carl Barks, Will Eisner, or, in more recent times, Frank Miller, who have combined functions that in most popular comic books are separate: writer, artist, inker, and even letterer or colorist.[12] However, in mainstream comics, a story is usually the result of teamwork. Typically, the writer is responsible for the plot, which is then drawn by the artist and inked by the inker. The letterer fills in the balloons, and the colorist, not surprisingly, provides the chromatic effects for the story. Furthermore, the Aristotelian pattern applicable to both the film and the novel does not quite work with the comics: even if an episode is self-contained (and this does not happen very often in contemporary comics), it is usually part of a larger narrative that spans the whole of the series of a specific character, and in many cases other series by the same publisher, with plots and subplots carrying over from episode to episode. It is extremely unusual for any member of the creative team to stay with the character for more than a few years, and as comics' characters are passed on from creative team to creative team they are reinterpreted, their story told again and again, so that, while remaining the same, they keep changing their relationship with the public. David Newman's remark that "each generation gets the Lois Lane that it deserves" can be generalized to the whole of comicdom. In a sense, a comic book character is always already a remake.

Thus, we can return to the interpretation of the comics as myth. There are a number of narrative elements that can justify Newman's approach to Superman in these terms. Newman himself mentioned, for instance, Superman's vulnerability to kryptonite, which can be compared to Achilles's heel, or, in a more complex way, his status as a superior being walking among mortals disguised as one of them, which can offer a number of parallels with the central myth of Christianity, Christ's first coming.[13] What to me is significant is that Newman's approach, derived from local details of Superman's story, coincides with a more general approach to popular culture, and comics in particular.[14]

Through myth, the problem of the relation between original and adaptation can be framed in a new way. In his seminal essay "The Structural Study of Myth," Claude Lévi-Strauss argues that with mythological narratives the question of the original cannot be asked: "Our method . . . eliminates a problem which has, so far, been one of the main obstacles to the progress of mythological studies, namely, the quest for the true version, or the earlier one. On the contrary, we define the myth as consisting of all its versions; or to put it otherwise, a myth remains the same as long as it is felt as such" (217). Now, I would like to argue that myth has been effectively used as a model in discussing a number of popular narratives because it interprets well the way that popular narratives are produced and circulated.

In a 1962 essay entitled "The Myth of Superman," Umberto Eco articulated his critique of superhero comics by comparing them to myths.[15] The limitations of Eco's essay are, perhaps, those of the general approach to popular culture at the time of its writing. Surprisingly for a critic who has always shown a great, and positive, interest in popular culture, Eco here plays the part of the "apocalyptic," falling back on a simplistic critique of popular literature as a means of manipulation and control of the "masses" on the part of "the offices of the great industries, the advertising men of Madison Avenue, what popular sociology has called, with a suggestive epithet, 'hidden persuaders'" (Apocalittici e integrati, 223). However, some of his comments can be of some use in this context.

After arguing that, in contemporary industrial society, "the positive hero must embody to an unthinkable degree the power demands that the average citizen nurtures but cannot satisfy" ("The Myth of Superman," 107), Eco then discusses the problems that this "archetypal" function of the superhero entails on a narratological level. He contrasts myth and novel as two diametrically opposed narratives: in the former, we have a story that follows an already established pattern; in the latter, the events in the story happen as the story is being told, so that the main concern is on "what will happen next?" According to Eco, comics superheroes are divided between these two forms of narrative: "The mythological character of comic strips finds himself in this singular situation: he must be an archetype, the totality

of certain collective aspirations, and therefore he must necessarily become immobilized in an emblematic and fixed nature . . .; but, since he is marketed in the sphere of a 'romantic' production for a public that consumes 'romances,' he must be subjected to a development which is typical . . . of novelistic characters" ("Myth of Superman" 110).[16] His conclusion that "for precise commercial reasons, . . . [Superman's] adventures are sold to a lazy audience" that "would be terrified by an indefinite development of the events that would keep their memory busy for several weeks" (Apocalittici e integrati, 232) is of course part and parcel of the moralizing attitude of early popular culture studies. What Eco misunderstands here is precisely what I have indicated earlier: popular narratives are produced in ways that cannot be assimilated into postliterate classical literature, and the iterative mechanism (as he calls it) of popular narratives need not be only a symptom of mental laziness on the part of both producer and audience. The development of the narrative over time in subsequent retellings and rearticulations does not entail a suspension of memory, a sort of continuous oblivion, as Eco seems to imply, but works more effectively the more the audience is aware of the previous articulation of the narrative that each retelling extends and remakes. I suspect that one of the reasons for the lukewarm popular reception of Dick Tracy was precisely the fact that, after his heyday in the thirties and forties, the square-jawed detective has not been "retold" for later audiences and therefore has not become as deeply ingrained in American culture as his caped colleagues.

In a later essay on repetition and seriality, Eco himself has come to reexamine the pleasures of iteration in a more positive light, even suggesting the possibility of an "aesthetics of serial forms," whose purpose would be to provide an account of the historical configurations of the dialectic between innovation and repetition ("Innovation and Repetition," 175). From this point of view, it is precisely on the level of myth that remakes and serial forms should be considered: "Every epoch has its myth-makers, its own sense of the sacred. . . . Let us take for granted the intense emotional participation, the pleasure of the reiteration of a single and constant truth, and the tears, and the laughter—and finally the catharsis . Then we can conceive of an audience also able to shift onto an aesthetic level and to judge the art of the variations on a mythical theme" (182). The distance between this and the "lazy audience" envisioned in the previous essay is obvious. What is important, however, is the fact that in this "aesthetic of serial forms" the question of the original is bracketed out, and what makes the text successful is its effectiveness as a variation on its theme.

What narrative could pretend to be the original of the Superman film? Of course, we know that in June 1938 the first issue of the comic book Action Comics published a story entitled "Superman," written by Jerry Siegel and drawn by Joe Shuster. That story can make the claim to be the (chronologi-

cally) "first" version of Superman, but not the original, since the character has profoundly changed in its fifty-year career, and the version that Newman looked at for inspiration was as far from Siegel and Shuster's as that of today's comics is from either. The point was made succinctly by Frank Miller in a recent interview: "Go back to the origins of Superman, before World War II. He was dragging generals to the front of the battles. He was fighting corrupt landlords. He was not the symbol of the status quo he's since become" (Sharrett, 39).

Batman has undergone a similar fate: from the grim sometime gun-toting vigilante of the early stories he has gone on to become the wholesome crime-fighter of the mid-fifties and early sixties, the camp Batman of the TV series, and the current "Dark Knight" persona popularized by Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and uncountable comics since then.[17] Even though Frank Miller's reinterpretation of the character has been billed as a return to the original, it had to take into account all the textual elements that the many rearticulations of the story of Batman have gathered in time. It was a propos The Dark Knight Returns that Alan Moore wrote: "Yes, Batman is still Bruce Wayne, Alfred is still his butler . . . There is still a Robin, along with a batmobile. . . . Everything is exactly the same, except for the fact that it's totally different."[18] The development of comic book narratives over time can be characterized as sameness with difference, as a reshuffling of a number of narrative elements into new patterns. It is this characteristic that distinguishes comic books (and, in the United States, superhero comics in particular) from most other types of narratives: like soap operas, they are designed to last, to progress over time without the climactic release of the end of a novel or a play or a film. To this must be added the fact that, as Jim Collins has noted, the different versions of the character do not simply follow each other chronologically, but, in a society in which texts can be reproduced cheaply and easily, they also circulate at the same time, so that the "origins" of Batman as told in the original 1939 story, in Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One, in Tim Burton's Batman film and comic adaptation thereof, and so on, are available to the audience at one and the same time. Each version is perceived as part of the same basic myth, so that the "original," the 1939 story, loses its status and becomes simply one of the many possible ways to articulate the myth.

As an example of this loss in status of the original, let me point out that, according to the Siegel and Shuster version of Superman, our hero did not fly, but could, much more prosaically, "easily leap 1/8th of a mile" (Siegel and Shuster, 19). Yet, flight is one of the powers more closely associated with Superman, and according to Newman one of the aspects of the film that the ad campaign concentrated on was precisely that it showed a man flying . Like the myths discussed by Lévi-Strauss, the "myth" of Superman

includes all its versions in a number of different media. We can now understand better why the Superman films are not adaptations: like the many rearticulations of the story within the comics medium, they take the basic elements that over time have come to constitute the construction blocks of a Superman narrative and reassemble them in terms of the new medium, to tell a story that adds one more layer to the "myth." Once this new version begins circulating, it becomes one of the many possible stories involving the character named Superman, one of the possible "sources" of any of his future narratives.

This can actually be seen as an asset from the point of view of translating comics into films. In fact, the lack of an urtext gives the creative team more freedom to consider the strengths and weaknesses of the cinematic medium. Tim Burton's film Batman provides a useful example. As we have seen, the fact that month in, month out, a new adventure of the hero must be published makes the definition of the characters in the book a matter of accumulation of details. Although Batman's archenemy the Joker appeared for the first time in 1940, it was only in 1951 that it was revealed how the criminal "Red Hood," in an attempt to escape Batman, dived into a vat full of a chemical substance that turned his hair green, his lips rouge red, and his face chalk white. Since then, and more so in recent years, Batman and the Joker have developed a sort of symbiotic relationship and are often portrayed as the opposite sides of the same coin: two madmen pursuing relentlessly and single-mindedly their own visions of the world as a place upon which must be imposed absolute order or absolute chaos (the classical texts here are two special volumes, Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's The Killing Joke, 1988, and Grant Morrison and Dave McKean's Arkham Asylum, 1989).

In Burton's film the problem of the accumulative development of this relationship was creatively solved by changing the origins of the Joker, so that he turns out to have been, before his transformation, the very thief who murdered Bruce Wayne's parents and was therefore responsible for the origins of Batman, just as Batman himself was responsible for the accident from which the Joker was born. Thus, the film establishes an interdependence between the two characters that is comparable to that in the comics, while taking into account the self-enclosed nature of the new medium. At the same time, elements introduced by Burton in the film, in particular the neo-Gothic architecture of Gotham, have been reappropriated in recent comics (Batman 474, February 1992; Tales of the Dark Knight 27, February 1992; and Detective Comics 641, February 1992) through a story specifically designed to change the graphic nature of Batman's environment to that developed by Anton Furst for Burton's movie.

Thus, as this last example makes clear, we must approach the question of the relationship between these two visual media, cinema and the comics,

by adopting a new paradigm that is not that of the remake nor that of the adaptation, neither of which fully accounts for the reassemblage of the narrative elements in the move from one medium to the other. The problem needs to be framed in terms that go beyond the question of influence and originality to clarify the unique way in which popular culture texts are appropriated and reconstructed by cinema.

I thank Krin Gabbard for his helpful comments on a previous draft of this essay.

Works Cited

Barbieri, Daniele. I linguaggi del fumetto. Milano: Bompiani, 1991.

Barrier, Michael, and Martin Williams, eds. The Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics. New York: Smithsonian Institution Press and Harry N. Abrams, 1981.

Barthes, Roland. Elements of Semiology. Translated by Annette Lavers and Colin Smith. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

Bassnett-McGuire, Susan. Translation Studies. London: Methuen, 1980.

Boichel, Bill. "Batman: Commodity as Myth." In Pearson, 4–17.

Byrne, John. Reply to the letter of Ryan Day. John Byrne's Next Men 10 (1992): n.p.

Carey, James W., ed. Media, Myths, and Narratives. Television and the Press. Newbury Park: Sage, 1988.

Collins, Jim. "Batman: The Movie, Narrative: The Hyperconscious." In Pearson, 164–181.

Couperie, Pierre et al. A History of the Comic Strip. Translated by Eileen B. Hennessy. New York: Crown, 1968.

Crafton, Donald. Emile Cohl, Caricature and Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Daniels, Les. Comix: A History of Comic Books in America. New York: Outerbridge and Dienstfrey, 1971.

Eco, Umberto. Apocalittici e integrati. 1964. Milano: Bompiani, 1990.

———. "Innovation and Repetition: Between Modern and Post-Modern Aesthetics." Daedalus 114, no. 4 (1985): 161–184.

———. "The Myth of Superman." Translated by Natalie Chilton. The Role of the Reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979. 107–124.

Fell, John L. Film and the Narrative Tradition. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986.

Inge, Thomas M. Comics as Culture. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1990.

Kowal, Patricia. "Dick Tracy." In Magill's Cinema Annual 1991 , 92–95. Pasadena: Salem Press, 1991.

Kunzle, David. The Early Comic Strip. Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c.1450 to 1825. Vol. 1 of History of the Comic Strip. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973.

Levine, Lawrence W. Highbrow/Lowbrow. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. "The Structural Study of Myth." Structural Anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

Lozano, Elizabeth. "The Force of Myth on Popular Narratives: The Case of the Melodramatic Serial." Communication Theory 2, no. 3 (1992): 207–220.

Mollica, Vincenzo. "Viaggio a Tulum." Corto Maltese 7, no. 7 (July 1989): 8–9.

Moore, Alan. "The Mark of the Batman: An Introduction." The Dark Knight Returns. By Frank Miller. New York: Warner Books, 1986.

Nash, Jay Robert, and Stanley Ralph Ross. The Motion Picture Guide. Vol. 3. Chicago: Cinebooks, 1986.

Newman, David. "Superman Takes Flight." Paper presented before the Modern Language Association Convention, New York, 29 December 1992.

Nye, Russel. The Unembarrassed Muse. The Popular Arts in America. New York: Dial Press, 1970.

Ostrander, John. Reply to the letter of Allan Lappin. The Spectre 3 (1993).

Parsons, Patrick. "Batman and His Audience: The Dialectic of Culture." In Pearson, 66–89.

Pearson, Roberta E., and William Uricchio, eds. The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Reitberger, Reinhold, and Wolfgang Fuchs. Comics: Anatomy of a Mass Medium. Translated by Nadia Folwer. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1972.

Sharrett, Christopher. "Batman and the Twilight of the Idols: An Interview with Frank Miller." In Pearson, 33–46.

Siegel, Jerry (story) and Joe Shuster (art). "Superman." 1938. In Barrier, 19–31.

Thomas, Roy (story) and Mike Mignola (art). Bram Stoker's Dracula. Based on the screenplay by James V. Hart. 1 no. 1 (1992).

Uricchio, William, and Roberta E. Pearson. "'I'm Not Fooled by That Cheap Disguise.'" In Pearson, 182–213.

Williams, Martin. "About 'Superman.'" In Barrier, 17–18.

Witek, Joseph. Comic Books as History. The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989.

Eighteen—

"Tonight Your Director Is John Ford":

The Strange Journey of Stagecoach from Screen to Radio

Peter Lehman

Like many commentators on John Ford's Stagecoach , Edward Buscombe observes that the journey undertaken by the coach does not conform to the narrative implication that the travelers are going west into Indian[1] country. If the fictional journey has a strange geographical dimension to it, that is not the only strange journey that this fictional coach would undertake. On January 9, 1949, the NBC Theatre debuted with a half hour radio version of John Ford's Stagecoach. NBC Theatre was renamed Screen Directors Playhouse and, in 1950, expanded to one hour; it ran until 1951 (Dunning). It featured adaptations of successful films with many of the original stars. The films' directors introduced the programs and chatted about the original film afterward. A version of Fort Apache , which was broadcast on August 5, 1949, was the only other Ford film to be included in the series.

Since the shift from film to radio involves a form of adaptation, why consider it in a volume devoted to remakes? Actually, radio adaptations differ significantly from literary adaptations, which are generally the focus of adaptation studies. The author of the original literary work frequently has no creative involvement with the film adaptation and, in the case of many of the most prestigious adaptations, has lived before cinema was even invented. The mere fact that film adaptations included works by Shakespeare, Emily Brontë, and Tennyson created a significant distance between the original creators and the creators of the adaptations. Even when a living author has a role in writing the screenplay for an adaptation, as for example Mario Puzo did with The Godfather , such involvement at most seems to imply a likelihood that the adaptation will somehow be more faithful to the original vision of the novel. Such participation is not, however, directly perceived by the film spectator.

The Screen Directors Playhouse involved as many of the original stars as

possible re-creating their roles. In Stagecoach , both John Wayne and Claire Trevor play the same characters they played in the film and, similarly, Henry Fonda and John Wayne play the same central characters in both the film and radio versions of Fort Apache . Thus, the radio listener hears the same actor that he or she may have heard in the film, at times even speaking the exact same lines. In some sense, then, there is a more direct remake element at work in the radio programs, if only insofar as the fact that well-known actors are re-creating parts for which they are already famous. This points to yet another significant difference between filmic adaptations of literary works and radio adaptations of films. In the former case, many of the film spectators would not have read the original novels, plays, or poems or, if they had, they might have done so long ago. The Screen Directors Playhouse , however, featured recent popular films that many of the radio listeners would have seen. Although it included classics from the early forties such as Stagecoach , the 1949 broadcast of the 1947 film Fort Apache is much more typical of the series, and some of the programs even featured current films.

Since Stagecoach was the first program in the series, the introduction by George Marshall, president of the Screen Directors Guild, included comments about the nature of the new program "in which the directors will personally bring you their favorite film assignments." "Tonight," he tells the listening audience, "your director is John Ford." At the program's conclusion, Marshall returns, "Speaking for the Guild I'd like to express our gratitude to the National Broadcasting Company for the opportunity to better acquaint the public with the work and role of the screen director." Marshall's comments imply a close relationship between the original film and the radio version. Indeed, the public will not only become acquainted with the director who will "personally" introduce the film but also with the function of the film director. Although faithfulness to the original had long been a critical concept applied to film adaptations of novels, such adaptations were generally presumed neither to "personally" acquaint the filmgoer with the novelist nor to educate the film viewer about the role of the author. Even if it was presumed that one might learn about the original novel from such films, it was not presumed that one learned about writing fiction. During the discussion with Ford, Wayne, Trevor, and Ward Bond concluding the program, Trevor reinforces Marshall's point by remarking, "You know, I think it's wonderful that the screen director is being honored like this. He's the fellow that really makes the movie. Ask us actors and actresses."

The Screen Directors Playhouse is caught within a bizarre paradox. Sponsored by the Screen Directors Guild, it seeks to promote both the original film and the role of the director in creating that film, but it does so within a medium singularly unsuited to showcasing the talents of a film director. The announcer foregrounds this paradox at the beginning of the program, "Screen Directors Guild Assignment; production: Stagecoach ; director: John

Ford; stars: John Wayne, Claire Trevor, Ward Bond." After a brief musical interlude, another announcer repeats the film title and actors and adds, "And introducing the director of the film, John Ford." Initially, it sounds as if Ford is the director of this production since he is listed with the stars (one of whom, Ward Bond, was not even in the film version). Moments later, however, we hear the ambivalent announcement that this production will be "introducing" the film's director, John Ford. What then is his role in this production? At the conclusion of the program, the announcer tells us, "Production was under the supervision of Howard Wiley." It sounds at first like Ford is the director of this production, then like he is being introduced to the radio audience in his capacity as the film's director, and finally it becomes clear that he has had no role in this production other than that of brief guest.

This is a strange way either to acquaint the public with the role of the screen director or to honor "him," since, as I will argue, no significant features of the original aesthetic text survive this cross-media remake. Indeed, analysis of the radio remake of Stagecoach is helpful in revealing the quite different nature of radio programs and films as texts both aesthetically and ideologically and the quite different status of the director as an author in these two media. Whatever else may have happened on January 9, 1949, the public became acquainted with neither "John Ford's Stagecoach " nor the role of a film director.

The notion of "John Ford's Stagecoach ," as well as the concept of the role of the film director, invokes issues of authorship. I have elsewhere argued in detail that authorship in the arts can be usefully explored within Nelson Goodman's distinction between autographic and allographic arts (Lehman, 1990, 1978). Autographic arts are those, like painting, in which the hand of the artist is crucial in the creation of the aesthetic text. Forgery is thus a crucial issue since to claim that a painting is a Rembrandt is to claim a specific history for that painting—that is, Rembrandt painted it with his own hand, not someone in Tucson in 1992 claiming to be Rembrandt. If the latter is the case, we say that the painting is inauthentic. In an allographic art form, such as classical music, the hand of the artist is not an issue and there is no distinction between an original and a copy. Thus, should someone in Tucson in 1992 rush the stage during a performance of a Beethoven symphony, seize the score, and declare it inauthentic since it was printed by machine in Cleveland rather than handwritten by Beethoven, the poor soul, far from being hailed as having made an insightful discovery, would be led away and declared hopelessly confused.

What accounts for this different status among the arts? Goodman argues that allographic arts are contingent upon the existence of a notational system for the constitutive features of the aesthetic text. That is, whatever constitutes the identity of the aesthetic text must be amenable to notation.

The autographic arts have no such notational system and must be executed by the artist who creates the work. Rembrandt, in other words, could not notate an oil painting and leave it to someone else to paint. Notational systems can be understood by contrasting them with discursive language. In the former case, one and only one thing correctly corresponds to each notated mark within the system. Within classical music, for example, only one sound corresponds to each note. In discursive language, however, a limitless number of things correspond to each unit. There are many shades that correspond to the word "blue," and no matter how many other discursive words we use to qualify it (e.g., bright, extremely bright), this never changes; we can never limit the correspondence to a one-to-one relationship. In my past exploration of issues of autographic and allographic arts in relation to authorship, I have argued that comparing film and theater in particular reveals profound differences between a play script and a film script, as well as a theater director and a film director. It is necessary to briefly summarize those distinctions since I now want to argue that equally strong differences characterize writing and directing in radio and film.

No art forms lie entirely within a notational system. Thus, in classical music, discursive language such as the term "allegro" is used to supplement the notations. If a composer writes such things as "play fast" or "play with passion" on a score, those directions are not constitutive features of the aesthetic work. How one interprets or ignores such directions does not affect the identity of the work; however, playing wrong notes, leaving notes out or adding notes does affect the identity. Notational systems allow the distinction between the quality of the performance and the identity of the work; one can bemoan a poor performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 but still recognize it as Beethoven's work.

In the theater, the dialogue written by the playwright is part of a notational system, but the stage directions are part of a discursive language system. Thus, if someone playing Hamlet says, "Oh, that this too, too solid flesh would melt," he is in compliance with what Shakespeare wrote within the notational system. Only one spoken word corresponds to the notated word. To say, "Oh, that this flesh would melt," is to make a mistake equivalent to leaving out notes in a musical score. It affects the identity of the work rather than the quality of the performance. If, however, the stage directions read "exit stage left quickly" and the actor exits stage right slowly, the identity of the play is not affected. The consequences of this distinction are critical for understanding radio. Within Western theatrical tradition (there are other cultural traditions for theater, music, and all the arts), the dialogue the characters speak creates the fictional world and tells us what the play is fundamentally about. It is for this reason that the same play can bear countless interpretations with widely differing staging and, even more pertinent to our current inquiry into radio, a play can be fully compre-

hended with a staged reading. That is, the actors can be seated and not in costume. If they speak the dialogue, we can enter the fictional world of the play, understand the characters' actions and the play's themes. We need not see anything in order to identify Shakespeare's "Hamlet," and it is for this reason that we can read, understand, and even evaluate the play without ever seeing a performance of it.

Although we speak of theater and cinema in similar language (e.g., films have a script or screenplay , actors, and a director), they are in fact quite dissimilar. As with theater, only the dialogue spoken by the actors in a film is part of a notational system; camera directions, descriptions of shots and sets, and so on are discursive language. In the cinema, however, the visual image constitutes the diegesis of which the spoken word is only a small part. Dialogue in cinema, in other words, need not create the characters, describe the situations or even state the themes. Much less of the aesthetic text is amenable to notation in the cinema. It is a question of degree rather than kind, but the degree of difference is so great as to border on being one of kind. In this sense, the common expression that cinema is a director's medium rather than a writer's medium is correct.

Writers and screenplays are not, of course, useless. They occupy an intermediary stage in the process of creation. If a painter uses a photograph or a sketch in creating an oil painting, that prior image has served a useful purpose for him or her. It in no way, however, notates the constitutive features of the oil painting as an aesthetic text, though it may outline or indicate some of its features. Limitless paintings can be made using the same sketch or photograph and they can range in quality from excellent to poor—and they can be good or bad for quite different reasons. Screenplays do not notate the constitutive features of a finished film, though they may provide an outline or indication of some of those features.

The relationship between dialogue and gesture in the theater and cinema is virtually reversed. The dialogue, as we have seen, cannot be changed in the theater without altering the identity of the work. Every director staging "Hamlet" may stage it differently, however, and every actor playing the part may gesture differently than every other actor when delivering a given line. In the cinema, however, the gesturing and placement of the actor frequently are more important in the creation of the aesthetic text than the dialogue he or she speaks. In Ford's Stagecoach, for example, a scene occurs where Ringo (John Wayne) asks Dallas (Claire Trevor) to marry him. They stand close to each other, though separated by a hitching post upon which each places a hand. The aesthetic complexity of the moment derives, as we shall see shortly, from both the visual motif of the wooden hitching post and the fact that the characters are positioned on either side of it. The exact wording of Ringo's proposal and Dallas's reply is of lesser importance and, in fact, could be changed without greatly altering the film as a complex

aesthetic object. Were the actors to stand in front of a tree, however, the entire meaning and significance of the moment within a complex aesthetic text would collapse. In a very real sense, and in opposition to the theater, this can only be "staged" one way. From the point of view of aesthetics, the same screenplay filmed five different ways is not five performances of the same screenplay, but rather five different films with some similar features of story and dialogue—like five different oil paintings based upon the same sketch of an apple and a pear. It is precisely for this reason that reading screenplays is not analogous to reading play scripts and that a staged reading of Stagecoach would be an incomprehensible bore, no matter how much one liked the film. The spoken word in a film script is not a dense, complex aesthetic text as, for example, Shakespeare's "Hamlet" is. It neither creates nor sustains a fictional world, but rather may be a small part of it. The filmmaker, usually the director, fulfills the function of creating the diegesis. Which brings us finally to radio where, among all the media, the situation is once again virtually reversed; the written word does create and sustain the diegetic world and the writer, not the director, creates the aesthetic text. It is within this framework that we can best understand the radio version of Stagecoach as well as the paradox of its production by the Screen Directors Guild.

After the introduction, the radio version of Stagecoach begins with a cowboy song, then Ford narrating the story's premise about the stagecoach journey in 1885 from Tonto to Lordsburg and the dread of the dangers posed by Geronimo. "It's a story still told by the Indians," Ford says, and the narration then segues to an American Indian narrator who tells of the "mighty white invader" and the city of Tonto, where the "stagecoach stopped to take men to the Westward where Geronimo was leader, chief of the Apaches." The story begins in Tonto, where the stagecoach passengers are warned of the dangers of their journey.

The use of the Indian narrator, who is heard again during and at the end of the story, frames the events quite differently than occurs in the film, where a white narrator tells of the dangers of Geronimo at the film's beginning and is never heard from again. While the brief use of a narrator at the beginning of a film, who then never reappears, is a convention of classical Hollywood cinema, it is important here to note the consequences of the narrational shift in the radio version. The film never claims to have any sympathy with Geronimo or the Apaches; they are simply introduced from the white perspective as a threat to civilization, which is assumed to be synonymous with white culture.[2] In a somewhat bizarre manner, the radio program seems to frame the story as one told from the Apache point of view, something that receives emphasis since it is the last thing we hear Ford tell us. Certainly nothing about the film or the short story upon which it is based seems to justify such a perspective. Why would the Apaches want

to tell a story about the journey of whites? Furthermore, in Ford's film, the Apaches receive no development as human beings with their own culture; they are simply a threat synonymous with the wilderness. They emerge from it, attack the coach, and flee back into it. They do not speak and we do not even glimpse their village or way of life. If this radio program is a version of the film, we might very well wonder why the Apache would still tell this story.

The radio version offers no answer. We hear the Indian narrator during the Apache Wells scene as he tells of the gathering Apaches who are about to attack the coach. He returns at the end of the story and, in a totally unexplained manner, celebrates the "brave" white "man's" story: "Thus the story of those brave men, riders of the flying wagon, in the land of Arizona where Geronimo was chief. In the great land in the desert where the flying wagon galloped, that the white men called the stagecoach, bringing brave men to the West." In his initial appearance, the narrator spoke with respect for Geronimo's attempt to stop the "white invader." During the Apache Wells scene, he gives knowledge of what the Apaches are doing, thus at least representing their point of view. At the end, however, he is simply reduced for no apparent reason to celebrating the victory of the enemy of his people. The racism resulting from this narrational strategy is thus of a markedly different kind than that in the film.

The opening scene of the radio program establishes a major aesthetic strategy of this version, a dramatic paring down of the film's characters. Mrs. Mallory, Hatfield, Doc, and Dallas are identified as the sole passengers, with no mention of Gatewood or Peabody. Buck, so effectively characterized by Andy Devine in the film, is a character in name only here, though the sheriff, played by Ward Bond, functions similarly to the film's sheriff. Once the journey gets under way, the coach stops only once, rather than twice as in the film, and there are no characters of even minor significance introduced at the stop. Such a paring down of characters and events is to be expected within the shift from the hour-and-a-half classical Hollywood format to the half hour radio format. As in Hollywood's adaptation of nineteenth-century novels, for example, there are simply too many characters and events in the film to be included in the radio program. Some events, such as when Ringo stops the coach in the wilderness and the sheriff places him under arrest as an escapee, occur in the radio version very much as they do in the film but they take on quite different meanings than in the film.

The manner in which Ringo stops the stage and gets on it in the film has several levels of visual significance. In contrast to all the other passengers who board the coach in town, Ringo is associated with the wilderness in which he first appears.[3] When he gets in the coach, he sits on the floor with his back to the door, the wilderness visible through the window in

every shot of him. His position on the floor between the rows of passengers also visually establishes the mediatory function he fulfills: as tensions mount in the coach, rather than take sides he attempts to calm people down. In the radio program, there is no strong association with the wilderness and Ringo sits next to Dallas when he gets on the coach. Their conversation is an abbreviated but similar version of the lunch conversation they have at the first stop in the film; Ringo perceives Dallas as a "lady" and himself as a societal outcast.

At Apache Wells, the travelers learn that Captain Mallory and the troops have been sent ahead to Lordsburg, a vote is taken as to whether to go back or proceed with the journey, Dallas is overlooked in the vote, Mrs. Mallory faints, and Doc Boone is drunk when needed—in short, an encapsulated version of events from the film. Mrs. Mallory gives birth, and Dallas brings the baby to the men. Although the scene seems to parallel that in the film, it serves a different dramatic function since none of the serious divisiveness caused by such things as Gatewood's and Peabody's desire to go back is present in the radio version. Thus, the dramatic counterpoint of everyone gathering together in a rare moment of peaceful unity is absent.

The scene does fulfill the function, however, of bringing the mother/whore dichotomy into play. We are told euphemistically at the beginning of the program that Dallas is being thrown out of town because she is too "hospitable to the gentlemen." After seeing her hold the baby, Ringo later tells her, "I watched you with that baby today. You looked . . . you looked . . . well, nice." He then proposes to her and she replies, "You don't know me. You don't know who I am." These two moments of the radio program closely follow the film, even repeating dialogue, but once again, the aesthetic and ideological significance varies greatly between the two versions. Classical Hollywood cinema, of course, frequently characterizes women as either nonsexual mothers or sexualized whores, the whore with a heart of gold being a common variant. The iconography of Dallas holding the baby relates to this filmic tradition and operates specifically through point-of-view editing: the spectator, as well as Ringo and the others, is positioned to see Dallas as a mother. Furthermore, Stagecoach dramatically illustrates the mother/whore polarization within which many female characters were trapped in classical Hollywood: in an instant Dallas goes from one pole to the other and the sight of her holding the baby justifies the reversal. The extremes come dangerously close to baring the device and thus revealing the restrictive limitations of such either/or characterizations.

Similarly, the scene where Ringo proposes to Dallas receives its complexity visually through their positioning around the corral post, described above. The hitching post and the closely related image of the corral post are associated throughout the film with the very civilization that creates

such stereotypes as the good mother and the bad whore and then drives the whore out of town. The corral post figures prominently in a shot near the beginning of the film as the coach followed by the cavalry leaves Lordsburg. We see corral posts in the lower foreground of the frame, a butte looming in the center distance, and a dirt road stretching between them. The coach followed by the cavalry enters from the lower right and proceeds along the road on its journey into the wilderness. This highly formal composition, which visualizes the film's dramatic structure of a journey from civilization into the wilderness, prominently uses the corral posts to signify the last vestiges of civilization. The entrances into both of the stagecoach stops are shot in ways that similarly reinforce this post motif with the temporary safety of these isolated places of civilization in the wilderness. Similarly, the horrors of the Indian attack upon Lee's Ferry, the last stagecoach stop, are visualized in images of corral posts left standing in the smoldering ruins. Finally, the hitching post motif appears prominently in Lordsburg as Ringo and Dallas walk along and she fears his reaction when he discovers the truth about her, and as she waits alone in anguish after hearing the sounds of gunshots between Ringo and the Plummers.

It is only in the wilderness that Ringo, who first appears and boards the stage in the wilderness, can perceive Dallas freed from the stigma of her social role, but the post that divides them is a reminder of the realities of the social roles to which they must and do return. When they arrive in Lordsburg and Ringo walks Dallas "home," they once again stand with their hands on a hitching post, this time united on the same side as Ringo resolves to return to Dallas after killing the Plummer boys. In the radio program, there is no complexity to his marriage proposal equivalent to the visual reminder of society's restrictions that Ford's positioning of Ringo and Dallas, and later Dallas alone, provides. Not surprisingly, the same is true at the end of the program when they arrive in Lordsburg. When Ringo leaves Dallas to fight the Plummers, we simply hear him tell her to wait for him. It is a simple event in contrast to the complex culmination of the hitching post motif we see in the film; the way Ringo and Dallas stand with their hands on the post is a profoundly moving moment of the sort that distinguishes Ford's Stagecoach .

As in the film, after Ringo proposes to Dallas, she convinces him to escape, saying she will join him later at his ranch in Mexico. As he attempts his escape, however, he encounters Indian smoke signals and goes back to warn the others. The Indian narrator returns and tells of how his nation had to strike "the white man's flying wagon." After the narration, we return to the coach where the passengers mistakenly think they are safe. As in the film, the false sense of security is shattered by the Indian attack.

The scene is interesting in how it uses dialogue to attempt to describe action that we see in the film. "Ringo, look out! That Apache on the painted

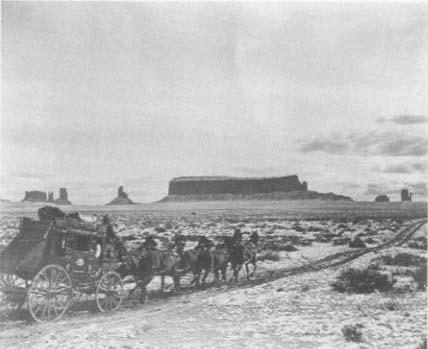

Figure 38.

Transforming John Ford's Stagecoach (1939) to a radio broadcast

raises questions about the loss of formal compositional elements.

pony," Dallas screams. We hear a gunshot and Ringo replies, "Got him." "See that Indian on that mustang coming alongside?" Doc asks. "Don't talk, shoot," someone orders and Doc responds by shooting and saying, "Well, now you see him and now you don't." This is the only place in the radio program where we hear an attempt to describe what we see in the film. Indeed, the element of visual detail (e.g., "the painted pony" and the "mustang coming alongside") is forced and out of place. It breaks with the style of the rest of the program where the characters, within the codes of realism, talk as they would in such a situation. Here they talk as if the purpose is to help us visualize the action. It is of note that the effort to supply this type of filmic visualization occurs in an action scene and is never used to recreate any of the film's visual motifs. (See figure 38.)

During the fight scene, Hatfield is killed. Ringo tells Dallas to use the last three bullets on herself, Mrs. Mallory, and the baby so that they won't be captured by the Indians. In the film, in contrast, Hatfield holds the gun to Mrs. Mallory's head as she prays and he prepares to shoot her. He is killed before he can do so and after he slumps over we hear the sound of

the bugle indicating the cavalry rescue. Indeed, Hatfield is almost able to kill Mrs. Mallory because Ringo has left the inside of the coach and, in a heroic act, jumped onto the team of horses in an effort to bring them under control. Ringo's active attempt to save the day contrasts sharply with Hatfield's resignation, and it is a contrast that has been richly developed throughout the film.

Both Ringo and Hatfield are men who live by a strong code of behavior: Hatfield is the Southern gentleman and Ringo the westerner. Although their codes are dissimilar, the two men are similar in how they adhere to their codes. Indeed, they are both driven in nearly identical fashion by those codes; Hatfield goes to Lordsburg because his code requires him to protect the Southern "lady" and Ringo goes to Lordsburg because his western code requires him to avenge his brother's death at the hands of the Plummers. In Ford's vision, the crucial distinction between these two men is that one of them enacts a code appropriate to his environment and context and the other applies an inappropriate code of conduct. This is clear in the scene where Hatfield offers Mrs. Mallory a drink out of his silver cup but refuses the courtesy to Dallas. The purpose of social codes is to ease interaction among people, but Hatfield's act merely introduces further discord into the group. Even if his distinction between the two women were valid within an upper-class, genteel Southern tradition, it is hopelessly out of place within this stagecoach in the western wilderness, but Hatfield does not perceive this. Similarly, within Ford's vision, Hatfield's preparation to kill Mrs. Mallory reflects an almost despicable failure of masculine western courage and action. He should be risking his life in battle with the Indians rather than fatalistically preparing to kill a woman. For this reason, it comes as a relief to the film audience when Hatfield slumps over dead. In the radio program, however, Hatfield's death is of little significance, and the way in which Ringo fulfills the function of saving the women from the "fate worse than death" has no more significance in relation to his character.

A description of this scene indicates how the film director can create a dense visual and aural text around a simple narrative event. In one shot, we see Mrs. Mallory praying fervently as a gun from off screen left enters the frame and points at her head. She appears oblivious to her impending death when suddenly the gun drops slowly downward and finally drops out of the frame. Mrs. Mallory continues praying and we hear the sound of a bugle blowing off screen. Her facial expression changes from fear to hope as she realizes the significance of the impending cavalry rescue. Narratively, the moment is not only simple but even clichéd—it is the classic last-minute cavalry rescue. What distinguishes it, however, is Ford's beautiful use of offscreen space. We never see Hatfield as he prepares to shoot Mrs. Mallory or when he himself is actually killed; we infer his death from the dropped gun. This shot begins by being structured visually around offscreen space

then ends by being structured aurally around offscreen space: we hear the bugle before we see the cavalry riding to the rescue. A conventional cutting pattern showing Hatfield prepare to shoot Mrs. Mallory, then being hit himself, followed by a direct cut to the cavalry riding to the rescue while we simultaneously hear the bugle would rob this scene of its distinction.

The bugle signals the rescue in the radio program as in the film, and the last scene takes place in Lordsburg. The scene bears careful analysis because it is by far the most aesthetically complex in the radio program, and the nature of that complexity reveals much about the relationship of radio narratives to film narratives. After Ringo tells Dallas to wait for him and goes off to seek the Plummers, Dallas says a prayer. We hear distant shots as her prayer continues, followed by the cowboy song heard at the program's beginning and finally the sound of footsteps heard from Dallas's perspective. Dallas emotionally asks, "Who . . . who's that out there?" and then she happily exclaims, "Ringo!" The scene unexpectedly draws upon the nondiegetic sound element of the cowboy song that had previously been perceived as simple introductory music, as well as draws on elements of diegetic sound perspective from the position of the character around whom the scene is structured, and it further layers those sounds with the foregrounded sound of Dallas's prayer.

The final scene is perhaps the only scene in this remake that achieves a life of its own. Whereas many of the scenes seem to be lesser versions of story elements taken from the original, totally stripped of their visual, thematic, and dramatic complexity—or as in the fight scene, failed efforts to create filmic visual equivalency—the final scene creates an aural density that is, simply put, good radio. Although it takes from Ford's film the idea of Dallas waiting and finally hearing Ringo's footsteps before identifying him, it develops the concept in an original way. In the film, for example, we see Ringo engaged in his fight with the Plummers. Structuring the scene entirely around Dallas waiting intensifies one element of the dramatic structure in the original and makes it the primary organizing principle.

The last scene concludes when Ringo tells Dallas that before dying Luke Plummer confessed that he killed Jed Michael, the crime for which Ringo has been in jail. He is now a free man. Dallas cries in response and Ringo asks despairingly, "Dallas, what are you crying for?" and naively adds "Nothing's happened." On this happy note, the previously discussed narration concludes the program. In the film, Luke Plummer doesn't confess and the sheriff turns the other way to allow the guilty Ringo to "escape" with Dallas to his ranch in Mexico where they will be spared "the blessings of civilization." Since the radio program entirely lacks the film's rich development of the ironic treatment of civilization's blessings, the happy ending makes perfect sense. It is central to Ford's film that Ringo and Dallas have to flee

civilization since civilization lacks the flexibility and complexity to perceive them in a different light. They remain the escaped convict and the whore.

Clearly, the radio program does not present "John Ford's Stagecoach ." Indeed, it is hard to talk about it as either a remake or an adaptation of Ford's film. If anything, it adapts the outline of some of the major story elements and a few fragments of the dialogue but, as I have argued, it is in the nature of film that those elements only constitute a small portion of the finished filmic text. In other words, those are the simple elements that do not create a dense aesthetic text in themselves as they do in theater but that may be used in the creation of such a text. The radio version of Stagecoach fails to create a rich aesthetic text not because of anything about the nature of radio, as the exception of the fight scene shows, but because most of this program is content to merely re-present simple story elements from the film. It is also in the nature of radio, however, that if Ford were to have directed this script it would have made little or no difference since the writing creates, shapes, and sustains radio's diegetic worlds. Radio directors have little to do except shape vocal performance and sound effects. If we had five different versions of the same radio script of Stagecoach by different directors we would have five different versions of performances of the same work. In contrast to cinema, the identity of the work clearly lies with the writer, not the director.

The Directors Guild seems to have perceived this paradox since the directors did not direct the radio programs. If in fact one wants to present the director to the public, this would be the logical manner. But since the directors would not be involved in an analogous directorial activity, they were simply presented to the public as personalities who introduced the program and reminisced about the original film. The way in which each director is announced at the beginning of the program as the "director" betrays the confusion. Even if they were the directors of the programs, there would, in the filmic sense of the term, be little or nothing for them to direct. The situation would be quite different in the mid-fifties when the Screen Directors Guild became involved with television and the Screen Directors Playhouse . In 1955, John Ford directed Rookie of the Year . Rather than a remake of a film, the program was an original drama. Both the guild and Ford perceived that in this medium there was a creative role for the film director; he need not simply be briefly presented to the public. Presumably, he was making something rather than remaking something for a different medium. Yet, the guild and the film directors may have seen more commonality between directing in these two media than actually exists. How television directing compares to film and radio directing is, however, another story for another time.

If the Screen Directors Guild's promotion of film directors on radio was

a strange aesthetic paradox, from the economic perspective it made good sense. The guild quite correctly perceived that radio, and later television, could be used to promote and stimulate interest in films. The announcer says at the end of the broadcast of "Stagecoach," "John Wayne can soon be seen in John Ford's Argosy Production Three Godfathers , and Claire Trevor appears in the soon-to-be-released Amusement Enterprises picture The Lucky Stiff . Ward Bond is currently appearing in the Victor Fleming production Joan of Arc ."

And one last thing. If the public was not treated to "director John Ford's Stagecoach " on January 9, 1949, whose remake was it? During the closing credits of the show, we are told, "Tonight's story was adapted by Milton Geiger." From the point of view of aesthetics and authorship, the announcer should have proclaimed at the beginning, "Tonight your creator is Milton Geiger" rather than "Tonight your director is John Ford." What the significance of that would have been in 1949 is unclear. Unfortunately, given the scholarly lack of interest in radio aesthetics, it is still unclear today.

Special thanks to Warren Bareiss for sharing his knowledge of radio and his resources with me.

Works Cited

Baxter, John. The Cinema of John Ford. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1971.

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990.

Buscombe, Edward. Stagecoach. London: British Film Institute, 1992.

Dunning, John. Tune in Yesterday: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Old Time Radio. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

Goodman, Nelson. Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968.

Lehman, Peter. "Script/Performance/Text: Performance Theory and Auteur Theory." Film Reader 3 (1978): 197–206.

———. "Texas 1868/America 1956." In Close Viewings: An Anthology of New Film Criticism , edited by Peter Lehman, 387–415. Tallahassee: Florida State University Press, 1991.

McBride, Joseph, and Michael Wilmington. John Ford. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975.

Place, J. A. The Western Films of John Ford. Secaucus: Citadel Press, 1974.

Nineteen—

M*A*S*H Notes

Elisabeth Weis

When George S. Kaufman proclaimed that "satire is what closes on Saturday night," he was referring to its ephemeral quality: satire dates quickly. And I would add that political satire dates twice as quickly. Probably because the painful realities it mocks are all too immediate, political satire seems particularly funny while it is fresh. But the intensity of satiric humor is often inversely proportional to its durability. Try looking at the opening monologue from last year's Tonight Show . We don't even get the jokes. Or look at any reruns of Saturday Night Live that bash then-current presidents. For every political satire that remains funny, there are a dozen that could be called Saturday Night Dead .

If satire has a short life span, film is a medium that tends to date almost as quickly. While transcribing a screenplay to film, the camera also records such specifics as hair styles, acting styles, and even cinematographic styles, which permanently fix the film's production in a particular time and place. (Even in historical films, matters of style are kept within the parameters of contemporary fashion—to wit: the stars of M*A*S*H were allowed to wear their hair longer than allowed by military regulation for 1950.) By contrast, a play can be updated in performance, through acting style as well as language. Similarly, a novel is regularly transformed by the sensibility of each reader, who supplies much of the mise-en-scène with his or her imagination. But though films are certainly "read" by different viewers in different ways, there is a permanence to the original image that resists reinterpretation.

Hence, as both film and political satire, the 1970 M*A*S*H would seem particularly resistant to being remade. Robert Altman's send-up of the American involvement in Vietnam, the military mentality, and the estab-

lishment in general, is a movie particularly rooted in the counterculture spirit of its time.