2

Democratic Beliefs: The Normative Dimensions of Control

A map has many uses besides aiding travelers in reaching their destination. It locates all destinations in relation to one another and thus gives the reader of the map a sense of the overall terrain. Similarly, our map gives us a way of grounding arguments about specific control mechanisms within a broader structure of analysis. By understanding how many of the attributes of particular proposals are linked to the positions they occupy on the map, we can generalize to classes of proposals and, more important, increase our understanding of the contours of the problem of democratic control.

In this chapter I connect control strategies lying in different territories of the map with beliefs about democracy. That such connections exist should not be surprising. At stake is how to control bureaucracy "democratically." Ideas about what democracy entails ought to play a prominent part in thinking about how bureaucratic decision making can be reconciled with democratic institutions.[1] This is not to say that normative debate

[1] Hanna Fenichel Pitkin makes an analogous point about theories of representation: "In the broadest terms, the position a writer adopts within

the limits set by the concept of representation will depend on his metapolitics—his broad conception of human nature, and political life. His views on representation will not be arbitrarily chosen, but embedded in and dependent on the pattern of his political thought" (Pitkin, The Concept of Representation [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1972], p. 167).

about bureaucratic control is in fact common. Quite the contrary is the case. But such debate is implicit in "pragmatic" discussions of what to do about the problem of bureaucracy.

An understanding of the normative issues embedded in the map provides a way of assessing control strategies by emphasizing the different goals for democratic control and the different visions of political actors embodied in them. It serves the further function of alerting us to the normative content of debate over various forms of control. Seemingly practical arguments may in fact be based on normative disagreements. The weaknesses of specific reforms may turn more on problems with underlying assumptions than on flaws in design. Attention to either of these phenomena may provide new interpretations of arguments raised about specific control strategies.

There is no neat typology of theories of democracy to provide a ready guide to the normative terrain. Partly this is because democratic theorists do not organize themselves into clearly identifiable camps. More important, it is because these theorists rarely deal with the problem of bureaucracy at all. It is generally ignored, assumed away by defining the role of administration as neutrally implementing legislative policy, or taken note of but dismissed. Direct application of theoretical orientations is often impossible, since the theories have been formulated without reference to the problems posed by bureaucracy. Robert Dahl, for example, both maintains that one of the eight conditions for polyarchal democracy is that "the orders of elected officials are executed" and realizes that this condition

"is the source of serious difficulties," but then drops consideration of the issue entirely, saying that "the extent to which this condition is achieved is perhaps the most puzzling of all to measure objectively."[2]

Yet strong connections do exist between theories of democracy and strategies for bureaucratic control, particularly around two sets of normative issues. First is the debate over the relative capabilities of the rulers and the ruled. One's position on this issue conditions how tightly one believes bureaucrats should be constrained. Second is the broad question of what the proper role of democratic government should be, and, more specifically, whether government is valued more as a means for achieving substantive ends or as a set of procedures for safeguarding liberty. Different positions on this issue imply different kinds of constraints on bureaucracy. Together these two sets of issues provide the normative dimensions of the map.

The Rulers and the Ruled

At the heart of the first set of issues embedded in the map is the question, How capable are citizens of governing themselves? As defined in chapter 1, control of bureaucracy means removal of discretion from bureaucrats. This in turn requires the transfer of a measure of governmental decision-making power away from bureaucrats to the citizenry. But how great a transfer should occur? How much discretion should be removed? That depends on

[2] Robert A. Dahl, A Preface to Democratic Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956), pp. 71, 73.

what one thinks about the ability of the people and of their elected officials to make governmental decisions.[3]

Making governmental decisions involves choosing the courses of action government will pursue. How capable one thinks people are of making those choices depends in turn on how one thinks about political interests. Should we seek to have the expressed preferences of the citizens embodied in public policy, or is it better to respond to a more detached perception of public needs? Is it possible for an "outsider," be it a legislator or an administrator, to determine someone else's needs, or can needs only be known by the individual concerned? Are all preferences of equal value, or are there some that should be either inadmissible in government decision making or of particular weight?

Theorists have sought to determine the "right" answer to these and kindred questions, and many analysts have attempted to classify the possibilities.[4] For our purposes a precise categorization is not necessary. What is important is the basic relationship between the nature of interest and the ability of people for self-governance. The more one believes that government should respond not to what citizens say they want but to what decision makers think they need, or, quite distinctly, the more one believes that some wants are more deserving than others, the less

[3] Other factors (such as the opportunity costs that the effort to control bureaucrats may extract) may, of course, enter into the choice of a control strategy in addition to the normative premises discussed here. See chapter 7 below.

[4] See, for example, Brian Barry's distinction between want-regarding and ideal-regarding principles, and his discussion of the concept of interest in Political Argument (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965), especially chaps. 3 and 10; Charles E. Gilbert, "Operative Doctrines of Representation," American Political Science Review 62 (1963): 604–18; A. H. Birch, Representation (London: Pall Mall Press, 1971); Steven Lukes, Power (London: Macmillan, 1976); and Glendon Schubert, The Public Interest (Glencoe IL: Free Press, 1960).

one believes that the power of government should be lodged directly and equally in the hands of the people.[5]

Modern democratic theory has typically examined political interests and citizen ability in the context of the relationship between voters and their representatives. The growth of bureaucracy and the influence bureaucrats have over the contents of policy decisions introduces a new factor into the equation. The issue is not merely the proper distribution of power between the rulers and the ruled, but also the relationship between the rulers and the ruled together on the one hand and the bureaucrats on the other. Thus, the problem of how to control bureaucracy democratically in part hinges on the question, How capable are the citizens and their elected leaders of governing?

Answers to the classic question about citizen ability do not automatically convert into answers to the variant that includes bureaucrats. The belief that legislators are superior to citizens as governors does not necessarily translate into the belief that bureaucrats are superior to the citizen-legislator combination. Traditional discussions of the issue of citizen ability are not, however, irrelevant to the problem of bureaucratic control. The arguments developed are highly instructive for the kinds of positions that may be taken about the proper degree of bureaucratic discretion.

Barriers to Competence

By its very existence representative government signals at least some limits on self-rule. The source of these limits,

[5] Again, Pitkin's discussion of representation is parallel. "The more [a writer] sees interests … as objective, as determinable by people other than the one whose interest it is, the more possible it becomes for a representative to further the interest of his constituents without consulting their wishes" (Pitkin, Concept of Representation , p. 210).

more than their extent, is crucial for our consideration of bureaucratic control. We may think of two basic sets of barriers to self-rule: (1) structural barriers that derive from the complexity of the governmental process and (2) individual barriers that arise from putative shortcomings of the ordinary citizen. The two sets of barriers may co-exist and reinforce each other, but conceptually they are distinct and have quite different implications for bureaucratic discretion.

Information is the key to structural barriers: citizens are limited in the role they can play in government because they do not know enough. One reason they do not know enough is the sheer scale of government operations, or, as Walter Lippmann describes it, "the intricate business of framing laws and of administering them through several hundred thousand public officials."[6] A second reason they do not know enough is that they do not have the technical expertise needed to make sense of increasingly complex political issues. A. D. Lindsay explains, "We recognize that the man in the street cannot, in the strict sense of the word, govern a modern state. The ordinary person has not the knowledge, the judgment, or the skill to deal with the intricate problems which modern government involves."[7] Thus, one set of arguments we must consider is that the size and technical specialization of complex modern government combine to erect formidable barriers to the ruled also being able to rule.

A quite different set of reservations about the capabilities of ordinary citizens is based not on the challenge presented

[6] Walter Lippmann, The Essential Lippmann (New York: Random House, 1963), p. 110. Also see Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1962), pp. 256–64, for the argument that the distance between citizens and the problems governments must deal with makes ordinary people incapable of self-governance.

[7] A. D. Lindsay, The Modern Democratic State (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962), p. 267.

by government complexity, but rather on an assessment of human nature. Although there are substantial variations in emphasis and nuance within this group of arguments, the basic theme is that what individuals think is best for themselves is not necessarily what is best for society. The challenge to citizen competence thus takes the form of questioning the very legitimacy of citizen rule. Leaders are needed to steer government onto the appropriate course, to save people from themselves.[8]

One strand of thinking ascribes the need for leadership to the instability of individual preferences and the inability of people to account for the ways in which their desires affect others. Unbridled citizen demands produce chaotic and ephemeral public policies. As A. H. Birch argues, there is a "gulf between the policies a government would follow if it responded to the varying day to day expressions of public opinion and those it must follow if its policies are to be coherent and mutually consistent."[9] For government leaders to act responsibly, they must temper the pursuit of popular wishes with a measure of wisdom.

A second variation on the theme of the need for leadership suggests that individual preferences not only fail to produce responsible collective action, they are often not even reflections of true needs. From this perspective it is the pursuit of the latter that is the proper role of government.[10] Joseph Tussman writes, "Government is purposive, but it is a mistake to suppose that its purpose

[8] Peter Bachrach characterizes such arguments as elite theories. He argues: "All elite theories are founded on two basic assumptions: first, that the masses are inherently incompetent, and second, that they are, at best, pliable, inert stuff or, at worst, aroused, unruly creatures possessing an insatiable proclivity to undermine both culture and liberty" (Bachrach, The Theory of Democratic Elitism [Boston: Little, Brown, 1967], p. 2).

[9] A. H. Birch, Representative and Responsible Government (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964), p. 21.

[10] This position, often called idealism, is discussed by Birch, Representation , and Schubert, Public Interest .

is simply to give us what we want."[11] The distinction between wants and needs is sharply drawn by Christian Bay: "Basic human needs are characteristic of the human organism and they are presumably less subject to change than the social or even the physical conditions under which men live. Wants are sometimes manifestations of real needs, but, as Plato and many other wise men since have insisted, we cannot always infer the existence of needs from wants."[12] Needs may emerge and be served through collective discussions led by wise leaders or through the actions of a superior elite, but they are not likely to be the subject of government decision making if left to the independent actions of individual citizens.[13] Thus, another barrier to self-rule is raised.

These potential barriers to popular self-governance—the structural and the individual—are rooted in the assumption that there is a determinable public interest.[14] In the first case it is presumed that this interest is derived through the application of knowledge and/or expertise, in the second through the use of wisdom. In both cases rulers alone, and not ordinary citizens, are presumed to possess a vital quality needed for governance.[15]

[11] Joseph Tussman, Obligation and the Body Politic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 110.

[12] Christian Bay, "Politics and Pseudopolitics: A Critical Evaluation of Some Behavioral Literature," American Political Science Review 59 (1965): 48.

[13] See Birch, Representation , pp. 93–95, and Gilbert, "Operative Doctrines," for a summary of the idealist position on the importance of leadership and discussion.

[14] For discussions of varying views of the public interest see, among others, Richard E. Flathman, The Public Interest (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1966); Carl J. Friedrich, ed., Nomos V: The Public Interest (New York: Atherton Press, 1967); Schubert, Public Interest; and Frank J. Sorauf, "The Public Interest Reconsidered," Journal of Politics 19 (1967): 616–39.

[15] Aberbach, Putnam and Rockman call this the "governance model" on society and public affairs. They contrast it with what they call the "politics model" (Joel D. Aberbach, Robert D. Putnam, and Bert A. Rockman, Bureaucrats and Politicians in Western Democracies [Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1981], chap. 5).

Citizen Rule

Other theorists assess the relative abilities of the rulers and the ruled quite differently. They assume that people are highly capable of governing themselves and that the voice (if not the physical presence) of the citizens should be the direct determinant of public policy. One set of thinkers disputes the very concept of a single objective public interest. An array of theorists who share the assumption that interests are multiple and fundamentally subjective, and that the public interest emerges through the interaction of these many interests, are included in this set.[16] These theorists see political decision making as the interplay of many forces, including various private concerns, the technical competence of bureaucrats, and a more general perspective provided by legislators or elected executives. They also consider this interplay to be desirable.

Again, for the purposes of dissecting the problem of bureaucratic control, the substantial differences within this perspective are much less important than the common conception of the abilities of the citizenry. Since there is no separate entity called "the public interest," there is no single group—neither the knowledgeable nor the wise—that has particular capabilities for governing. Ability is presumed to be dispersed widely throughout the polity.

[16] The concept of interest as subjective and highly individual is probably most clearly seen in the writings of the utilitarians such as Bentham and the two Mills. For a discussion of the political implications of this idea of interest, see Birch, Representation , and Pitkin, Concept of Representation . The idea that there are multiple interests in society has been a dominant strain in American political thought, starting with Madison in The Federalist Papers (1787–88), further developed by John C. Calhoun in A Disquisition on Government (1850; reprint, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1953), and more recently reflected in group theorists such as David B. Truman, The Governmental Process (New York: Knopf, 1951). Madison, of course, disputed the desirability of this state of affairs, but argued for a political system carefully constructed around its inevitability.

A second cluster of arguments for popular ability makes a stronger assumption about citizen capacities, while removing the emphasis on the multiplicity of interests. In outline, this position is that of the radical democrat. Perhaps its most well-known variant is what Robert Dahl calls "populist democracy and an insistence on majority rule is the central tenet.[17] According to this theory, the principles of popular sovereignty and political equality combine to create the fundamental rule that "in choosing among alternatives, the alternative preferred by the greater number is selected."[18] Each citizen, by definition, is presumed to be equally able to determine the course of government action since expressed preferences are the only legitimate basis for such action. Peter Bachrach explains that the democrat "being unable to claim that his values are true for all men and for all time, he is unwilling to impose them upon his fellow men … each individual's judgment on the general direction and character of political policies is given weight equal with all others."[19] A more extreme form of radical democracy, derived largely from the thought of Rousseau, stresses the importance of participation.[20] From this perspective democracy requires much more than majority rule. It requires the direct involvement of all citizens in the governmental process.

The Rulers, The Ruled, and The Bureaucrats

Modern democratic thought offers us a number of perspectives on the question, How capable are people of governing

[17] Dahl, Preface to Democratic Theory , chap. 2.

[18] Ibid., pp. 37–38.

[19] Bachrach, Theory of Democratic Elitism , p. 3.

[20] Carole Pateman develops this perspective into what she calls the theory of participatory democracy (Pateman, Participation and Democratic Theory [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970], chap. 2).

themselves? The responses range from "not very capable at all" to "competent by definition." It also offers us a series of arguments about the nature of politics. Policy questions are variously viewed as technical issues, efforts to fulfill the public interest as divined by a qualified few, group conflicts, or questions about the will of the majority (or of the entire populace). The possibilities are surely more extensive, but these alternatives are sufficient to explore one of the normative dimensions of our map of democratic control of bureaucracy. Because these conceptions are derived from the traditional debate about the relative abilities of the rulers and the ruled, however, and because that debate does not convert directly to the bureaucratic variant of the question, we must translate each alternative into a position on the map.

The Realm of Loose Constraint

The realm of loose constraint is, by definition, a realm of considerable bureaucratic discretion. It is supported by the belief that the implementers are significantly more capable than both the ruled and the elected rulers. Bureaucrats must be allowed a great deal of latitude because as administrative experts they are uniquely competent to serve public needs.[21] This conclusion, in turn, is usually premised on the assumption that there are structural barriers

[21] As Joseph A. Schumpeter argues, "Democratic government in modern industrial society must be able to command … the services of a well-trained bureaucracy.… Such a bureaucracy is the main answer to the argument about government by amateurs.… It is not enough that the bureaucracy should be efficient in current administration and competent to give advice. It must also be strong enough to guide and, if need be, to instruct the politicians who head ministries. In order to be able to do this it must be in a position to evolve principles of its own and sufficiently independent to assert them. It must be a power in its own right" (Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy [New York: Harper and Row, 1962], p. 293).

to citizen rule. It is the complexity of modern government that places the bureaucrats in their advantageous position.

Complexity, as discussed earlier, has two basic sources: the scale of government, and the technical difficulty of public policy issues. Although both are impediments to citizen rule, the former might not be a hindrance to elected officials and thus might not translate into a justification for extensive bureaucratic discretion. After all, is it not the business of elected officials to know their way around government? To some extent, of course, the answer is yes; but this was much more the case in the days of simpler and smaller government. Today, government functions have become so diverse and so extensive that even full-time representatives find it impossible to keep track of all that is going on. Over thirty years ago Robert Dahl and Charles Lindblom argued that the number of government decisions and the detail, expertise, and speed involved combine to create a situation in which "the role of legislative politicians in deliberately shaping the great bulk of the decisions made by executive politicians is exceedingly attenuated. They are umpires, who sometimes rule the ball out of bounds; but they do not carry the ball themselves or, except by enforcing the basic rules, determine the strategy."[22] The passage of three decades has only reinforced the pattern.[23] Governmental insiders have themselves become outsiders when compared to the bureaucrats involved with the day-to-day administration

[22] Robert A. Dahl and Charles E. Lindblom, Politics, Economics and Welfare 1953; reprint, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), p. 321.

[23] Robert A. Dahl recently wrote: "In modern democratic countries the complexity of the patterns, processes and activities of a large number of relatively autonomous organizations has outstripped theory, existing information, the capacity of the system to transmit such information as exists, and the ability of representatives—or others, for that matter—to comprehend it" (Dahl, Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982], p. 52).

of programs. As Lippmann wrote, "Only the insider can make decisions, not because he is inherently a better man but because he is so placed that he can understand and act."[24]

If a focus on the sheer scale of government translates into an argument for relatively unconstrained bureaucratic behavior, an emphasis on the technical component of government policies does so even more strongly. While elected leaders may be more capable of mastering technical complexity than ordinary citizens, either because they constitute a superior elite or because they have more time and resources to devote to studying the issues, their limits are also likely to be reached quickly. Indeed, virtually by definition, the more political issues are seen to encompass technical questions, the greater the necessity for discretion by the technical experts—that is, the bureaucrats. In what has probably become the classic statement of this position, Friedrich argues that "throughout the length and breadth of our technical civilization there is arising a type of responsibility on the part of the permanent administrator, the man who is called upon to seek and find the creative solutions for our crying technical needs, which cannot effectively be enforced except by fellow technicians who are capable of judging his policy in terms of the scientific knowledge bearing upon it."[25]

Both kinds of governmental complexity, then, limit not only the ability of citizens but also the ability of their elected leaders to govern; both argue for the necessity of bureaucratic discretion. Thus one normative foundation for relatively loose forms of control of bureaucracy is the belief that political decisions involve highly specialized

[24] Lippmann, Essential Lippmann , p. 114.

[25] Carl J. Friedrich, "Public Policy and the Nature of Administrative Responsibility," in Carl Friedrich and Edward Mason, eds., Public Policy, 1940 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1940), p. 14.

and/or technical issues. Consequently, the best government is government by experts.

The Realm of Tight Constraint

The other major set of impediments to citizen rule—the alleged inability of most individuals to perceive either their own or collective needs—might appear also to support the need for bureaucratic discretion. However, unlike the argument that citizens are not expert enough to discern public needs, the position that they are not wise enough does not necessarily translate into an argument for the superiority of bureaucrats at governance. If leadership, leisure, and distance from the daily wants of the populace are the requisites for effective and responsible decision making, then elected leaders should be favorably equipped. One of the great virtues of representative government is supposed to be that the leaders will possess these qualities and are therefore in a favorable position to serve the public interest.[26] Although a flawed political sense may be an impediment to the ability of ordinary citizens alone to rule, it is not an argument for the comparative advantage of bureaucrats over elected leaders, and hence is not an argument for bureaucratic discretion.

In fact, the contrary is true. From this perspective the narrow, specialized view of the bureaucrat is a liability, not a virtue. If determining the public interest is the task of the wise leaders of the community, then the bureaucrats must be highly subservient and closely follow their directives. Instead of implying relatively weak forms of control as structural barriers do, individual barriers derived from

[26] See, for example, The Federalist Papers (1787–88; reprint, New York: Mentor Books, 1961), especially numbers 10, 57, 62, and 63.

the belief that ordinary people do not know the public interest imply the need for much tighter forms of constraint by wise leaders.

Some scholars have proposed a hybrid perspective, agreeing that the public interest is determinable only by the wise few, but suggesting that these few include bureaucrats. Thus, they use a public-interest perspective to justify bureaucratic discretion, not bureaucratic constraint. Merle Fainsod, for example, argues that administrators "are capable of recognizing some interests as more 'public' or more 'general' than other interests and of adapting, fusing and directing group pressures toward such a recognition."[27] Glendon Schubert, in discussing what he calls the idealist position that the public is "an incompetent source of public policy," argues that "idealists would maximize (or, at the very least, expand) the scope of official autonomy and discretion," including that of bureaucrats.[28]

The hybrid position, however, is somewhat problematic. Its proponents rarely give reasons for supposing that bureaucrats are any more capable than the disqualified citizenry. Moreover, grouping elected officials and appointed administrators together creates an analytic tangle, since the discretion of each cannot be maximized simultaneously. Unless one believes that expertise allows bureaucrats to transcend narrow private wants,[29] the prior assumptions about the nature of the public interest favor the discretion of elected leaders, and hence limit that of bureaucrats. Furthermore, the belief that expertise carries with it greater vision shifts the terms of debate

[27] Merle Fainsod, "Some Reflections on the Nature of the Regulatory Process, in Friedrich and Mason, eds., Public Policy , p. 320.

[28] Schubert, Public Interest , pp. 79, 80.

[29] Emmette Redford in fact takes this position in "The Protection of the Public Interest with Special Reference to Administrative Regulation," American Political Science Review 48 (1954): 1103–13.

away from the need for wisdom and toward our first set of arguments against citizen ability, the need for specialized expertise. Despite these inconsistencies, the justification for administrative discretion based on superior bureaucratic wisdom becomes an important one empirically. As we shall see in chapter 4, it is often used by the bureaucrats themselves.

A quite different perspective on citizen ability, namely, radical democracy, shares the realm of tight constraint with the public-interest perspective. To radical democrats all citizens are completely capable of governing, and there are therefore no liabilities in very close control of bureaucracy. From this viewpoint the job of bureaucrats is to do exactly as the people, or as their chosen representatives, say.[30] Herman Finer writes, "I again insist upon subservience, for I still am of the belief with Rousseau that the people can be unwise but cannot be wrong.… the servants of the public are not to decide their own course; they are to be responsible to the elected representatives of the public, and these are to determine the course of action of the public servants to the most minute degree that is technically feasible."[31] Here, then, good government comes not from the expert, not from the wise, but directly from the will of the people themselves. There is only one relevant competence, and that is vox populi.

The Realm of Moderate Constraint

We have just seen that quite different normative assumptions about the nature of political interest and about the

[30] Schubert calls this "rationalism." As he describes it, "It is in the public interest … to rationalize governmental decision-making processes so that they will automatically result in the carrying out of the Public Will. Human discretion is minimized or eliminated by defining it out of the decision-making situation; responsibility lies in automatic behavior" (Schubert, Public Interest , p. 31).

[31] Herman Finer, "Administrative Responsibility in Democratic Government," Public Administration Review 1 (1941): 339, 336.

abilities of citizens and of their leaders are embedded in the areas of loose and of tight constraint. But what of the region where democratic control of bureaucracy allows for a moderate amount of bureaucratic discretion? In that realm the underlying assumptions are that political interests are multiple and subjective, that there are many relevant competences for governing, and that ability to rule is fairly evenly distributed. These beliefs translate into the belief that competence is shared among the rulers, the ruled, and the bureaucrats. Taken alone, the assumption that all citizens are capable of serving their own interests arguably translates into a proposal that citizens should tightly control the actions of bureaucrats. However, the companion assumption, that many different legitimate interests exist in society and that no single one constitutes the public interest, provides the key to the implications for bureaucratic control of this perspective. If all are qualified to rule, if interests are varied, and if no one interest is objectively superior, then there is little justification for the concentration of power in any single place, since no one group can lay claim to a particular ability to govern.[32] Instead, on the basis of these beliefs, power should be dispersed so that many interests may be represented and no one alone will dominate.[33]

A moderately constrained bureaucracy holds several virtues from this perspective. To the extent that citizens or their representatives do limit bureaucratic discretion, the belief that citizens are capable of governing is reaffirmed. But since dispersion of authority is a crucial way

[32] As Robert A. Dahl has argued, one of the primary conditions for procedural democracy (the form of democracy he advocates) is that "no members of the association are in any relevant characteristic so clearly more qualified as to justify their making decisions for all the others" (Dahl, "On Removing Certain Impediments to Democracy in the United States," Political Science Quarterly 92 [1977]: 11).

[33] See The Federalist Papers , numbers 10 and 51.

of accommodating multiple interests, too much constraint from any one source is a problem. The bureaucracy thus joins the legislature as an arena in which contending interests compete.[34] Moderating constraint allows diverse interests to be heard and allows the latitude of action that is vital if compromises among interests are to be reached.[35]

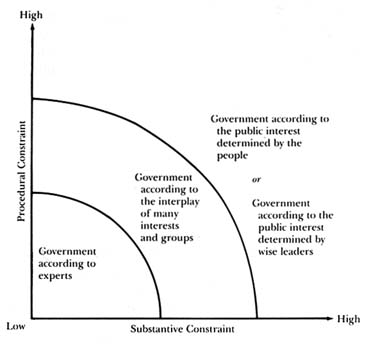

Regions of the Map

Four perspectives on citizen ability have now been translated into a viewpoint on the proper degree of bureaucratic discretion, and each may thus now be located on the map. I will call these perspectives government according to experts, government according to the public interest determined by wise leaders, government according to the public interest determined by the people, and government according to the interplay of many interests and groups. If the map is interpreted as a set of concentric bands starting at the lower left-hand corner, with the farthest band signifying the greatest constraint, then our

[34] Douglas Yates calls this the pluralist logic for bureaucracy (Yates, Bureaucratic Democracy [Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1982], chap. 1). Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman call it the politics model (Bureaucrats and Politicians , pp. 141–42). Stephen H. Linder similarly finds a rationale for discretion and bargaining in bureaucracies in pluralist thought (Linder, "Administrative Accountability: Administrative Discretion, Accountability, and External Controls," in Scott Greer, Ronald Hedlund, and James L. Gibson, eds., Accountability in Urban Society: Public Agencies Under Fire [Beverly Hills CA: Sage Publications, 1978], pp. 181–96. Vincent Ostrom's model of democratic administration is also premised on dispersion of authority (Ostrom, The Intellectual Crisis in American Public Administration [University AL: University of Alabama Press, 1974]), chap. 4.

[35] Dahl and Lindblom, for example, contend that "no one should suppose that by administrative fiat they can possibly overcome the fundamental lack of coordination inherent in the American political process; and to any person who believes polyarchy is desirable, the solution should be a repugnant one even if it were possible" (Politics, Economics and Welfare , p. 351).

Figure 3. Public Ability and Bureaucratic Constraint

four perspectives take their places as shown in Figure 3. As with most terrains, the topography of democratic control of bureaucracy is not marked by abrupt changes in geology. The bands are not intended to demarcate radical shifts in discretion but rather gradual shadings. Similarly, assumptions about citizen abilities blend at the fringes. Thus, while graphically the bands appear as sharp borders, they are not intended to signify such.[36]

[36] I have described and located what may be thought of as pure positions on the map. Many, of course, may take somewhat less pure stands and think competence varies depending upon the circumstances involved. Some, for example, may think citizens are more competent to judge substantive ends than

procedural issues, or vice versa. These people would alter their preferred location on the map according to the particulars of the circumstances they were considering. I discuss a major of variation in competence—differences among policy areas—in chapter 5.

The bands do, however, represent substantially different normative regions. For those who see the people as competent, the critical question is whether this competence lies in their collective capacity or in the results of their individual and group pursuits of their own wants. If the former, then the outermost band is occupied; if the latter, the central one. For those who do not see the people as competent, the issue becomes how well their elected representatives can fulfill the function of serving the people's interests.[37] The innermost band reflects the position that they cannot; the outermost stands on the assumption that they can very well. In the center, representatives are presumed to be one of many able participants in government decision making.

Who Constrains?

There remains, however, a seeming anomaly. Two quite different sets of assumptions support the farthest band: the belief that people are intrinsically incapable of serving their own interests (and must therefore be governed by wise leaders) and the belief that they are supremely capable of ruling themselves. Each belief supports tight constraint of bureaucrats, but they differ dramatically over who is capable of imposing constraint. The anomaly arises from the translation of the original question about the relative capabilities of the rulers and the ruled to a bureaucratic variant. In order to do this I considered the

[37] I take here Pitkin's definition of representation as "acting for" the interests of the constituents (Concept of Representation , chap. 6).

people and their representatives jointly and then analyzed various perspectives on their abilities compared to those of bureaucrats. These two perspectives nestled together in the outer band share the belief that the citizen-representative combination is highly competent, but they diverge over whether this competence lies with the citizens or with their leaders.

As this anomaly suggests, there is a third issue surrounding democratic control of bureaucracy that is not directly represented in our map. Control mechanisms not only constrain bureaucratic behavior to different extents, and constrain different aspects of behavior, they are also imposed by different political actors. Any position on the map implies a given degree of constraint on bureaucratic discretion, but this constraint may variously be exerted by individual citizens, organized groups of citizens, legislators, or elected executives. Strategies for control involving comparable limits on bureaucratic discretion but entailing intervention by different actors may thus occupy the same band on the map. The extent of constraint is premised on how much competence the citizens and their representatives are presumed to have relative to the bureaucrats, but the choice of an actor to exercise the control rests on beliefs about who has this competence.

Democratic Government: Freedom from Oppression or Self-Rule?

Should control be exerted over the procedures bureaucrats use to make decisions or over the substance of their actions? The issues surrounding citizen competence tell us little about this question and therefore constitute only one normative dimension of our map of bureaucratic

control. To explore the normative component of choice between procedural and substantive constraint, we must turn to another issue: the role of democratic government.

As with the problem of citizen competence, I start with a traditional question and then translate it into a bureaucratic variant. I begin with two fundamental conceptions of democratic government: first, that the distinguishing characteristic of such governments is that they secure and preserve the liberties of the citizens; second, that the essence of a democracy lies in the fact that public power is used to serve collective ends. Theorists have expressed this duality in many ways. Isaiah Berlin writes of two concepts of freedom, a negative freedom from interference or coercion by others and a positive freedom to be part of the group doing the interfering.[38] George Sabine discusses two strands of democratic thought, one emphasizing liberty, the other equality.[39] Both Berlin and Sabine trace the origins of the dualism to the philosophies guiding the English and French Revolutions respectively. In the American context, Dahl writes of two goals for democracy: the Madisonian quest for a nontyrannical republic and the desire for popular sovereignty.[40] Although there are important differences among these pairs of concepts, they each make the essential distinction between popular control as a means of preventing governmental oppression and popular control as a means of harnessing governmental power to public purposes.

At the heart of the first, or liberty-seeking, perspective on democratic government are the idea of a bounded

[38] Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958), pp. 6–19.

[39] George H. Sabine, "The Two Democratic Traditions," Philosophical Review 61 (1952): 451–74.

[40] Dahl, Preface to Democratic Theory , pp. 34–36.

state and the goal of preserving it. Berlin argues: "I am normally said to be free to the degree to which no human being interferes with my activity. Political liberty in this sense is simply the area within which a man can do what he wants.… It follows that a frontier must be drawn between the area of private life and that of public authority … liberty in this sense means liberty from; absence of interference beyond the shifting, but always recognizable, frontier."[41] From this perspective there is a legitimate range of government activity, but there is also a realm government must not enter. A primary function of democratic government is to honor and protect this second realm.[42]

Historically, this tradition is rooted in Madisonian and English liberal thought. In the nineteenth century it was taken to an extreme by John C. Calhoun in his theory of concurrent majorities. Calhoun argued that governments naturally tend toward oppression since they are composed of men, and men naturally seek to exalt their own private interests. The only way to prevent the consequent oppression is to give all interests in society a veto over all government actions that affect them. This is the system of concurrent majorities. He goes on to argue that it is "this negative power—the power of preventing or arresting the action of the government … which in fact forms the constitution."[43]

In sharp contrast is the idea of a powerful state that is central to the second, or action-seeking, concept of democracy

[41] Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty , pp. 7, 9, 11.

[42] As Douglas W. Rae points out, in so doing the public power of government is being used to preserve a private status quo, surely an active goal (Rae, "The Limits of Consensual Decision, American Political Science Review 69 [1975]: 1289–94. Nonetheless, I will persist in calling this the liberty-seeking perspective.

[43] Calhoun, Disquisition on Government , p. 28.

In this case, political equality is seen as consisting not of equal rights and freedoms but of an equal share in governmental decision making. A democratic government exists in order to take actions to serve the interests of its citizens. Freedom lies in the ability of each of the citizens to shape what those actions will be.[44] In the extreme case Rousseau argues that there is no private realm to be protected by the state; there are no forbidden areas of activity: "Each of us places in common his person and all of his power under the supreme direction of the general will; and as one body we all receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole."[45]

Two kinds of theories fall within this general perspective: those emphasizing specific ends the state should seek and those focusing on processes that ensure that citizen preferences determine government policy, most notably majority rule. The first category includes both the radical arguments that democratic government should act to achieve either socioeconomic equality[46] or psychological fulfillment[47] for its citizens and the generally conservative calls for democratic government to secure social stability or economic progress.[48] Prominent within the second category is the tradition of American populism[49] (which has

[44] Berlin describes this "positive" sense of freedom. "I am free if, and only if, I plan my life in accordance with my own will; plans entail rules; a rule does not oppress me or enslave me if I impose it on myself consciously, or accept it freely … the notion of liberty … is not the 'negative' conception of a field without obstacles, a vacuum in which I can do as I please, but the notion of self-direction or self-control" (Two Concepts of Liberty , pp. 28–29).

[45] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (New York: Hafner, 1947), p. 15.

[46] This perspective is described in Robert D. Putnam, The Beliefs of Politicians (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), p. 163.

[47] See, for example, Bay, "Politics and Pseudopolitics."

[48] Giovanni Sartori, Democratic Theory (New York: Praeger, 1965), pp. 103–5.

[49] See Dahl, Preface to Democratic Theory , chap. 2.

championed both decidedly progressive and strikingly regressive causes). All share a conception of democratic government as a positive force acting to achieve certain goals.

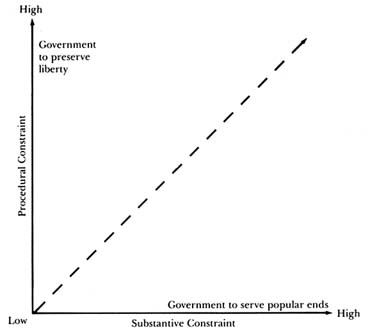

Translating these two perspectives to the problem of bureaucracy is a reasonably straightforward procedure. The traditional question considers the relationship between the citizens and the government and asks why citizens seek to control their leaders. The translation again consists of combining the citizens and their elected representatives and of then asking why this combined group (or any part of it) seeks to control bureaucracy. The first, or liberty-seeking, perspective on democracy answers, In order to prevent the abuse of power. The second, or action-seeking, perspective replies, To secure the proper use of power. These two alternatives, in turn, support the procedural and substantive axes of the map of bureaucratic control as shown in Figure 4.

If democracy means a government that respects individual rights, and if, therefore, control over bureaucracy is sought in order to prevent a violation of these rights, then the relevant control is constraint over bureaucratic procedures. That is because the central concern of people who share this perspective is not what the state should do but what the state should not do. One way of ensuring that the state does not violate liberty is to require that bureaucrats follow specified procedural norms.[50] The norms may be couched in terms of what the bureaucrats must do—for example, that they must consult certain

[50] Writing about red tape, surely one of the most lamented procedural constraints, Herbert Kaufman finds its origins in a concern for liberty: "A society less concerned about the rights of individuals in government and out might well be governed with a much smaller volume of paper and much simpler and faster administrative procedures than are typical of governance in this country" (Kaufman, Red Tape [Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1977], p. 46).

Figure 4. Democratic Government and the Nature of Constraint

groups; but this is a way of ensuring that they do not act counter to certain interests or do not violate certain rights.[51]

If, on the other hand, democracy consists of citizens sharing in government decision making, and if, therefore, control over bureaucracy is sought in order to ensure that bureaucratic power is used to further the ends

[51] Once again, parallels to theories of representation arise. This distinction is similar to the one Pitkin makes between representation as acting for—i.e., as a concept referring to the nature of the representative's decisions—and other more formal theories. See Pitkin, Concept of Representation , pp. 112–15.

the citizens have decided upon, then the relevant control is constraint of the substance of bureaucratic decisions. By constraining substance one ensures that bureaucrats work to achieve the ends set by the citizens.

Still unanswered is whether these two goals for democratic government are compatible. Figure 4 implies that the goals can coexist and that all possible mixtures may be achieved. Along each axis, one goal dominates. As one moves toward the diagonal, the mix includes increasing proportions of the other until the diagonal where both goals are equally sought. My intent is not to argue for perfect compatibility, however, but rather merely to allow for that possibility. Virtually all answers to the question of compatibility have been proposed at some time.[52] If one believes that popular control to preserve liberty and popular control to ensure the proper use of state power cannot coexist, then only positions on the map along the two axes are conceivable. If one believes that both these goals may be realized in some measure, then additional locations moving toward the diagonal enter into the realm of logical consistency; and if one believes they are totally compatible, then all positions on the map are possible. What one considers possible is not, of course, necessarily the same as what one considers desirable. Preferences determine where one actually chooses to go, but logical possibilities limit the range of choice.[53]

[52] See, for example, Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty , pp. 14–16, for the position that negative and positive freedom are irreconcilable; Tussman, Body Politic , pp. 25–30, for the argument that liberty is granted in return for the granting of state power; and Sabine, "Two Democratic Traditions," pp. 465–74, for a statement of their interdependence.

[53] The question of whether all positions on the map are, in fact, conceivable also arises. If all combinations of answers to the two sets of normative issues are not possible—i.e., if ability and goals are inherently linked—then certain areas of the map cannot logically exist. For example, if a liberty-seeking perspective was always joined to the belief that there are multiple, subjective interests in society, then the areas to the left (or liberty-seeking side) of the diagonal would be limited to the space defined by the central band.

Normative Beliefs and Political Reality

When people argue about mechanisms for controlling bureaucracy, they generallly focus on practical details. As we have just seen, however, fundamental normative questions concerning popular ability and the role of democratic government lie beneath the specific differences among control mechanisms. Often conflict over specifics masks debate over basic beliefs.

Controversies about clientele-oriented strategies of control lying in the central area of the map (Fig. 2) are a clear example. These strategies involve strengthening the ties between various societal groups and administrative agencies. Specific devices include advisory boards and formal group representation within an agency, and as Herbert Kaufman writes, "These practices are often assailed for giving too much weight to special interests as against the public interest, and their efficacy in furthering the cause of justice and rationality has been sharply questioned."[54] A focus on the efficacy of such strategies may be misplaced, however, since frequently what separates opponents from proponents is not a difference of opinion about how well a particular advisory mechanism works, but disagreements about whether group interests are "special" interests and hence any different from the public interest. Strategies lying in the central band of the map (Fig. 3) are premised on the assumption that group interests are not "special" interests, whereas critics of these strategies think they are.[55] Thus, controversy over an advisory

[54] Kaufman, Red Tape , p. 48.

[55] Grant McConnell, for example, sharply attacks group-based political institutions: "Far from providing guarantees of liberty, equality, and concern for the public interest, organization of political life by small constituencies tends to enforce conformity, to discriminate in favor of elites, and to eliminate public values from effective political consideration" (McConnell, Private Power and American Democracy [New York: Random House, Vintage Books, 1970], p. 6).

board may, in fact, reflect disagreement over the nature of interest in society. A focus on the narrow instrumental question will not resolve the underlying dispute.

Normative issues virtually by definition involve questions of belief, but this does not mean that they are completely immune to empirical evaluation. Some policy arguments are rooted in irreconcilable differences of basic belief, but other debates over control strategies are produced by a discrepancy between normative assumptions and the actual political context in which control takes place. Just as economic actors are not always the rational beings some economic theory presumes, political actors often defy normative expectations. A control mechanism premised on assumptions about political behavior that are not fulfilled is likely to be a control mechanism that does not work according to plan.

One way political reality may intrude lies in the roles political actors actually choose. A vivid example is found among control strategies lying in the outer band of our map (Fig. 3) that involve the imposition of constraint by legislators. Such proposals are premised on the assumption that there is a public interest that can be achieved through enlightened leaders who transcend the narrow focus of ordinary citizens.[56] If legislators behave little differently than the people who elect them, however, the expected enlightened intervention will not occur, and the intended control in the interest of broader public values will fail. Recent studies of the U.S. Congress indicate that this is often precisely the case. David Mayhew, for example, argues that the incentives facing members of Congress impel them to display

[56] Theodore J. Lowi's call for juridical democracy in The End of Liberalism (New York: Norton, 1969) is perhaps the best, but by no means the only, example.

a strong tendency to wrap policies in packages that are salable as particularized benefits … they tend in framing laws to give a particularistic cast to matters that do not obviously require it…. The quest for the particular impels Congressmen to take a vigorous interest in the organization of the federal bureaucracy. Thus, for example, the Corps of Army Engineers, structured to undertake discrete district projects, must be guarded from presidents who will submerge it in a quest for planning.[57]

To the extent that Mayhew is right that members of Congress have an incentive to pursue particularistic interests, no amount of tinkering with congressional control over the bureaucracy will produce coordinated control in the "public interest," and strategies based on that assumption are doomed to fail.[58] Worse still is the possibility that elected officials will attempt to control bureaucracies for the primary purpose of self-enrichment or self-aggrandizement. In that case control will serve neither the public interest nor the interests of ordinary citizens but only the individual interests of elected officials.

Control strategies based on the assumption that citizens or their representatives have sufficient expertise to control bureaucrats may also be vulnerable to undesired mutation if the assumption proves to be unfounded empirically. Dahl emphasizes the importance of what he calls "enlightened understanding" to democracy. "For if people regularly choose means that impede rather than facilitate attaining their goals, or if they invariably choose

[57] David R. Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), pp. 127, 128, 131. Arthur Maass, in Muddy Waters (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1951), and Lewis C. Mainzer in Political Bureaucracy (Glenview IL: Scott, Foresman, 1973) make similar arguments about congressional behavior vis-à-vis the bureaucracy.

[58] There is also evidence that executive branch control will produce similar results. See, for example, Dahl and Lindblom, Politics, Economics and Welfare , pp. 342, 352.

goals that damage their deeper needs, then of how much value is the process?" he asks.[59] Jerry Mashaw makes the point concretely in the context of a specific agency, the Social Security Administration. He is skeptical about increased claimant involvement as a way of controlling the bureaucracy, because claimants cannot command the information necessary to make involvement effective. "Without understanding, participation or control becomes an obvious and cruel joke rather than an assurance of fairness."[60]

A second way political reality may clash with democratic belief is if only some actors perform their expected roles. Control strategies premised on the assumption that government should serve the preference of the majority will not perform as expected when the majority do not express preferences at all.[61] If most people do not have preferences on most issues, control mechanisms based on the assumption that they do may actually work to serve the interests not of the majority but of a self-selected minority.

[59] Dahl, "On Removing Certain Impediments to Democracy," p. 18. Holden maintains that "the idea that 'higher authority' alone could either know enough of all the relevant situations or afford to make continuous readjustments of agency missions simply ignores the complex reality" (Matthew Holden, Jr., "Imperialism in Bureaucracy," American Political Science Review 60 [1966]: 950). Birch makes a similar point about legislative-administrative relations in British government in Representative and Responsible Government , pp. 150–53.

[60] Jerry Mashaw, Bureaucratic Justice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), p. 141.

[61] In a study in depth of political ideology, Robert E. Lane, for example, found that the expression of political grievances was unusual among the men he spoke with (Lane, Political Ideology [New York: Free Press, 1962], p. 455). Philip E. Converse reviews the evidence on the nature of political information and voting in his "Public Opinion and Voting Behavior," in Fred L. Greenstein and Nelson W. Polsby, eds., Handbook of Political Science , vol. 4 (Reading MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1975), as do Donald R. Kinder and David O. Sears in their "Public Opinion and Political Action," in Gardner Lindzey and Elliot Aronson, eds., Handbook of Social Psychology , 3d ed. (New York: Random House, 1985).

Once again, debates over minor modification in such strategies may miss a fundamental issue.

Selective action can also plague control strategies that assume that the public interest is served through the interaction of multiple interests in society. Even if one accepts this assumption, control strategies based on it may suffer if in reality only a subset of all interests are represented in the interaction. Typically this subset might consist of organized groups and actors who are in other ways powerful.[62] In this case, too, problems raised by specific strategies may not lie within the narrow architecture of the means of control, but rather in the broader context in which the control functions. Economic and political inequality may work to impede some groups from expressing their interests. When this is true the necessary conditions for the achievement of the public interest will be absent, even if the basic theory is sound.[63] Alternatively, the incentives built into the structure of political organizations may encourage them to pursue some interests but not others.[64] In that case as well, only some interests will be expressed and control strategies premised on the assumption that all interests are expressed will be undercut.

We have now seen that different control strategies rely on

[62] Many critics have noted that group-based control strategies tend to be dominated by the already organized. See, among others, Louis L. Jaffe, "The Effective Limits of the Administrative Process," in Alan Altshuler, ed., The Politics of the Federal Bureaucracy (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1968); Avery Leiserson, Administrative Regulation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942); Lowi, End of liberalism ; and Philip Selznick, TVA and the Grass Roots (New York: Harper and Row, 1966).

[63] Dahl discusses the need for greater economic equality, or at least for ways to prevent economic resources from being converted into political ones if democracy is to function properly ("On Removing Certain Impediments to Democracy," pp. 15–16).

[64] Dahl puts forward this argument in Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy , chap. 3.

different assumptions about the goals and methods of democratic government. Understanding the differences among assumptions helps us to understand why people differ in their choices of control strategy and provides a basis for making those choices. Understanding the assumptions also helps to identify cases in which the assumptions are likely to be violated when control strategies are employed in practice. Finally, this analysis begins the assessment of the benefits and costs of using any particular means to control bureaucratic discretion. This assessment will be continued in the next chapter, where I focus on the costs of control.