Statues Honoring the Great Tragedians

About the year 330 B.C. , Lycurgus, the leading politician in Athens, who was also in charge of state finances, proposed in the Assembly a decree for the erection of honorific bronze statues of the three great Classical tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, who had been active roughly a century before. The statues were to be set up in the Theatre of Dionysus, where their plays had been performed and where, in addition, the Assembly itself met (ps.-Plut. X orat., Lyc. 10 = Mor. 841F; Paus. 1.21.1–2). An authentic and definitive text of their works was also to be established and used as the basis for all future productions. This remarkable project was part of an ambitious program of patriotic national renewal.[5]

Sophocles: The Political Active Citizen

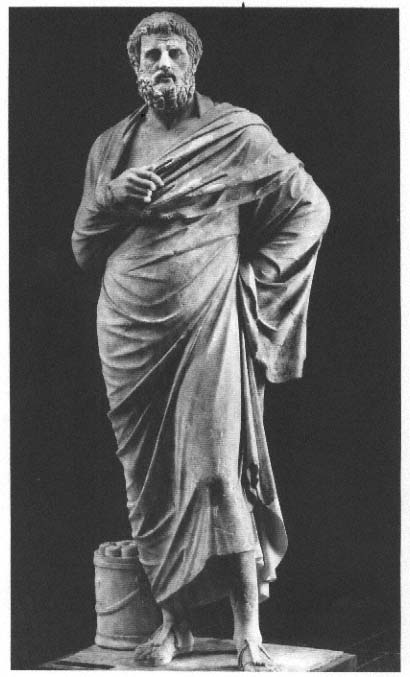

The statue of Sophocles belonging to the dedication seems to be faithfully rendered in an almost fully preserved copy of the Augustan period (fig. 25).[6] Sophocles stands in an artful pose that appears both graceful and effortless. The mantle carefully draped about his body enfolds both arms tightly. The right arm rests in a kind of loop, while the left, under

Fig. 25

Sophocles. Roman copy of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Rome, Vatican Museums.

the garment, is propped on the hip. The drapery allows even the legs little room for movement. Yet at the same time that he is so heavily wrapped, the position of the one advanced leg and the one arm propped up conveys a sense of energy and a commanding presence. The head is turned to the side and slightly raised, the mouth open. We have the impression that the poet is making a certain kind of public appearance. Among the Attic grave stelai, which repeatedly display the narrow range of acceptable poses and drapery styles that reflect standards of citizen behavior in this period, there is no male figure who matches this combination of being both heavily wrapped and yet making such an elegant and self-assured appearance. There is, however, a statue of the orator Aeschines, only slightly later in date, in a similar pose (fig. 26). This raises the possibility that Sophocles, too, is depicted as a public speaker.[7]

The model orator was expected to demonstrate extreme modesty and self-control in his appearances before the Assembly, and particularly to avoid any kind of demonstrative gestures. Thus this particular pose, with very limited mobility and both arms completely immobilized, along with the self-conscious sense of "making an appearance," would be particularly appropriate for an orator. Alan Shapiro has recently called attention to a red-figure neck amphora by the Harrow Painter, dated ca. 480 B.C. , on which a man is depicted in the same pose as Sophocles, standing on a podium, in front of him a listener leaning on his staff in the typical citizen stance (fig. 27). Most likely we have here indeed a representation of an orator.[8]

But why depict a tragic poet of the previous century in the guise of an orator? The issue of what constituted the proper bearing and conduct for public speakers, the correct attitude toward the state and its citizen virtues, was the subject of a lively debate in Athens in the years just before Lycurgus put up his dedication. If we may believe Aeschines, most politicians of his generation no longer observed the traditional rules of conduct but gesticulated wildly for dramatic effect, just as the demagogue Kleon had been accused of doing in the late fifth century. Aeschines' great rival Demosthenes seems to be one of those who at least sympathized with these supposedly undisciplined speakers.[9]

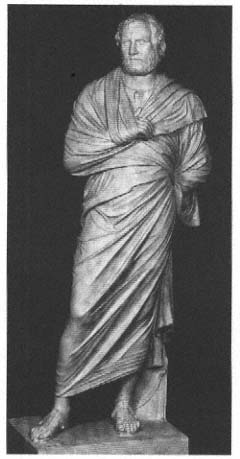

Fig. 26

Statue of the orator Aeschines. Early Augustan

copy of a statue ca. 320 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

In his plea for speakers to display a calm and self-controlled appearance, Aeschines invokes the example of earlier generations and, in particular, cites a rule stating that the speaker must keep his right arm still and wrapped in his cloak through the duration of his speech. Aeschines would naturally have equated this proper stance with ethical and moral

Fig. 27

An orator speaks from the podium. Attic

neck amphora, ca. 480 B.C. Paris, Louvre.

correctness (sophrosyne ). In this connection he refers explicitly to a statue of the lawgiver Solon in the Agora of Salamis:

And the speakers of old, men like Pericles, Themistocles, and Aristides, were so controlled [sophrones ] that in those days it was considered a moral failing to move the arm freely, as is common nowadays, and for this reason speakers did their best to avoid it. And I can give you definite proof of this. I'm sure you have all been across to Salamis and seen the statue of Solon there. You can then verify for yourselves that, in this statue in the Agora of Salamis, Solon keeps his arm hidden beneath his mantle. This statue is not just a memorial, but is an exact rendering of the pose in which Solon actually appeared before the Athenian Assembly.

(In Tim. 25)

Aeschines' opponent, Demosthenes, quickly responded to this, also in the Assembly, and made direct reference to the supposedly authentic statue of Solon:

People who live in Salamis tell me that this statue is not even fifty years old. But since the time of Solon about 240 years have passed, so that not

even the grandfather of the artist who invented the statue's pose could have lived when Solon did. He [Aeschines] illustrated his own remarks by appearing in this pose before the jury. But it would have been much better for the city if he had also copied Solon's attitude. But he didn't do this, just the opposite.

(De falsa leg. 251)

The controversy over the statue of Solon provides us not only proof of the importance of the pose with one arm wrapped up in the mantle. It also represents rare and valuable testimony to the function and popular understanding of public honorific monuments in the Classical polis. That is, in certain situations and in particular locations, a statue such as this one could become a model and a topic of discussion and could take on a significance far beyond the occasion of its erection. The statue was thus incorporated into the functioning of society in a manner altogether different from what we would expect from our own experience.

Aeschines himself, of course, appeared exactly in the pose of the speakers of old. And in the view of both his supporters and his detractors, he did so in a strikingly elegant and admirable manner. The statue in his honor, referred to earlier, does indeed show him in this very pose.[10] His statue evidently led Demosthenes to make the ironic comment that in his speeches Aeschines stood like a handsome statue (kalos andrias ) before the Assembly, a pose for which his earlier career as an actor had prepared him well.[11] But this is apparently just what Aeschines intended, to stand as still as a statue.

The debate over how one should properly appear before the Assembly was not, of course, simply a matter of aesthetics. In Classical Athens, the appearance and behavior in public of all citizens was governed by strict rules. These applied to how one should correctly walk, stand, or sit, as well as to proper draping of one's garment, position and movement of arms and head, styles of hair and beard, eye movements, and the volume and modulation of the voice: in short, every element of an individual's behavior and presentation, in accordance with his sex, age, and place in society. It is difficult for us to imagine this degree of regimentation. The necessity of making sure their appearance and

behavior were always correct must have tyrannized people and taken up a good deal of their time. Almost every time reference is made to these rules, they are linked to emphatic moral judgments, whether positive or negative. They are part of a value system that could be defined in terms of such concepts as order, measure, modesty, balance, self-control, circumspection, adherence to regulations, and the like. The meaning of this is clear: the physical appearance of the citizenry should reflect the order of society and the moral perfection of the individual in accord with the traditions of kalokagathia . Through constant admonition to conform to these standards of behavior from childhood on, they became to a great extent internalized. No one who wanted to belong to the right circles could afford to throw his mantle carelessly over his shoulders, to walk too fast or talk too loud, to hold his head at the wrong angle. It is no wonder that the individuals depicted on gravestones, at least to the modern viewer, look so stereotyped and monotonous.

The statues of Sophocles and Aeschines are therefore meant to represent not only the perfect public speaker, but also the good citizen who proves himself particularly engaged politically by means of his role as a speaker. The motif of one arm wrapped in the cloak had been a topos of the Athenian citizen since the fifth century and would continue into late antiquity, both in art and in life, as a visual symbol of sophrosyne, here meaning something like respectability. Indeed, rigid standards of behavior as an expression of generalized but rather vague moral values are a well-known feature of other societies. In fourth-century Athens, however, we have the impression in other respects as well that the aesthetic regimentation and stylization of everyday life increased as the values expressed in the visual imagery became increasingly problematic.

A glance at earlier occurrences of the Sophocles motif will help clarify its significance when applied to the public speaker. In vase painting of the fifth century, it is primarily adolescent boys who wear their mantle in the style of Sophocles, with both arms wrapped up. They appear in two contexts in which it was essential for them to display their modesty (aidos ): standing before a teacher and in scenes of erotic courtship.[12] The average citizen, by contrast, is usually de-

picted in a more relaxed pose. In the fourth century we occasionally find men with both arms concealed like Sophocles, usually as pious worshippers on votive reliefs.[13] Here again the point is to display modesty and awe, in this case before the divinity. The revival and spread of this long-antiquated gesture of extreme self-control for public speakers in the fourth century also carry a deliberate message for the demos and for the democratic system then in a state of crisis. It was precisely this concern for the democracy that was the focus of Lycurgus' political program.

But let us return to the statue of Sophocles. It presents the famous playwright not at all in that guise, but rather as a model of the politically concerned citizen. The fillet in his hair probably refers to his priestly office.[14] It is of no consequence whether the historical Sophocles did in fact take a particularly active role in politics or not. One of his contemporaries, Ion of Chios, remarks of him drily: "As for politics, Sophocles was not very skilled [sophos ], nor was he especially interested or engaged [rhekterios ], like most Athenians of the aristocracy" (Ath. 13.604D). The poet did, however, serve as general in the year 441/0.[15]

In any event, nothing about the statue of Sophocles alludes to his profession as a poet, neither the body nor the head (cf. fig. 40), which, with its well-groomed hair and carefully trimmed beard, perfectly matches the conventional portrait of the mature Athenian citizen on grave stelai and, like the portrait of Plato, has understandably often been perceived as lacking in expression. But this was just what those who commissioned the statue intended: to show Sophocles as a citizen who was exemplary in every way, including in his political activity, no more and no less than an equal among his fellow citizens, a man whom Lycurgus and his friends would wish to count as their contemporary.[16]

Aeschylus: The Face of the Athenian Everyman

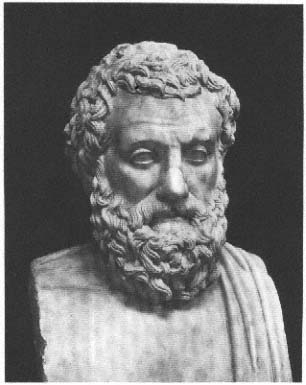

Identifying the portraits of the other two tragedians in Lycurgus' dedication is unfortunately more problematical, the evidence more fragmentary. A head that has convincingly been associated with the lost

Fig. 28

Portrait herm of the playwright Aeschylus. Augustan

copy of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

statue of Aeschylus portrays a man somewhat younger than Sophocles (fig. 28).[17] The subtly indicated lines in the brow are a feature that he shares, as we shall see, with many images of contemporary Athenian citizens. He too is a conventional type, as is evident from a comparison with the head of an Athenian named Alexos, from a wealthy family tomb monument of the same period (fig. 29).[18] As with Sophocles, there is no hint of intellectual activity in the expression, nor anything of Aeschylus' own character, for example, his severity (Aristophanes

Fig. 29

Head of Alexos from an Attic grave stele

ca. 330 B.C. Athens, National Museum.

Frogs 804, 830ff., 859). Rather than as poet, he too seems to have been depicted simply as a good Athenian citizen.[19] As for the body type, which is thus far not preserved, we can suppose, based on his age (in his middle years), on the billowing mantle on the herm copy in Naples, and on the typology of such figures on the gravestones, that he must have been standing erect.

Euripides: The Wise Old Man

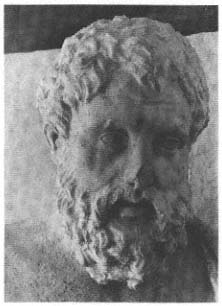

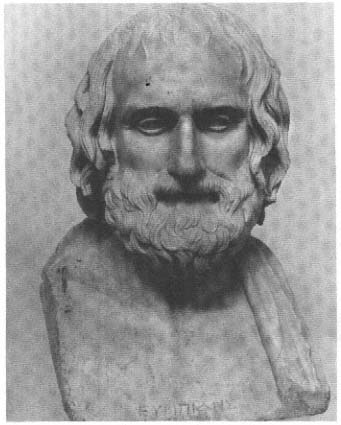

For the portrait of Euripides in Lycurgus' dedication the only candidate, on stylistic grounds, is, in my view, the inscribed copy known as the Farnese type (fig. 30).[20] It shows the poet as an elderly man with bald pate, a fringe of long hair, and subtle indications of aging in the face. Not just an ordinary old man, however, but a kalos geron, like the

Fig. 30

Portrait herm of the playwright Euripides. Roman copy

of a statue ca. 330 B.C. Naples, Museo Nazionale.

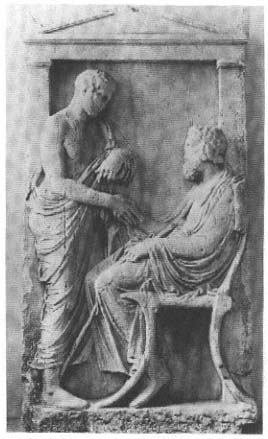

earlier portrait of Homer. In the highly conventional vocabulary of Attic gravestones, this type of old man is often shown seated, especially when he is the principal person being commemorated. (fig. 31). This is an allusion not just to physical weakness, but to the status and authority of the older man within the family (oikos ) and the polis.[21] The dignified, seated position of the elderly paterfamilias is, furthermore,

Fig. 31

Attic gravestone of Hippomachos and Kallias.

Piraeus, Museum.

an accurate reflection of the rituals of daily life. We may be reminded of the dignified figure of old Kephalos, at the beginning of Plato's Republic, who receives his guests seated on a diphros (Rep. 328C, 329E).

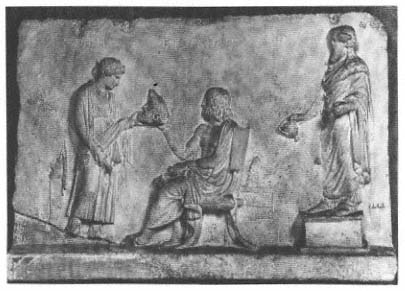

The portrait of Euripides of the Farnese type actually appears once on a seated figure, on a relief of the first century B.C. (fig. 32), which, on the basis of other elements, such as the chair and the overall style, could reflect an original of the late fourth century. The figure is com-

Fig. 32

Votive relief (?) of the seated Euripides, with the personification of the stage

(Skene ) and an archaistic statue of Dionysus. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum.

bined with two that are stylistically later in date, a personification of the stage (Skene ) and an archaizing statue of Dionysus, an eclectic mixture in which, we may well suspect, lurks a quotation of a well-known Classical portrait statue of a poet. Indeed, the classicistic artists of such reliefs as a rule did not "invent" any new figure types. The book roll and the pillow are already elements in the iconography of Late Classical grave stelai. And the mantle drawn up over the back, a standard characteristic of old men, as we see it on the herm in Naples, find a parallel on this relief.[22] In his raised right hand, Euripides takes a mask proffered to him by Skene . In the original portrait statue, to judge from the iconography of the gravestones, that hand could have held the old man's staff.

If we imagine the Euripides statue in this way, then we may well ask why he alone of the three tragedians was shown as an old man. It is

true, of course, that Euripides lived to be eighty, but then Sophocles was ninety, and Aeschylus did not die young either. Euripides in his lifetime was clearly ranked behind Aeschylus and Sophocles and was even accused by his contemporary Aristophanes of lacking any citizen virtues. But in the course of the fourth century, his reputation underwent an enormous transformation, so that by the time of Lycurgus he was considered the most outstanding of the great tragedians (Aristotle calls him tragikotatos at Poetics 1453a29f). For Plato and Aeschines he was simply the wise poet, and later he would even be called by Athenaeus the philosopher of the stage (skenikos philosophos ).[23] Wisdom and insight are precisely the qualities that set the elderly apart from younger men; this is why they enjoyed special privileges both in the life of the city and within the family. So, for example, men over fifty had the right to speak first in the Assembly (Aeschin. In Tim. 23).[24] Not by accident, the relatively few instances on Attic gravestones of this period of a figure holding a book roll are always seated older men like Euripides. That is, they are the only individuals in this highly stylized medium of the bourgeois self-image who are celebrated for their education and knowledge. The aged Euripides would thus have been shown seated to emphasize his extraordinary wisdom relative to the other two tragedians. When we try to imagine the three as a single monument, rather than as separate statues, a grouping of two standing figures and one seated would, by the standards of the gravestones, be a perfectly acceptable one.

If this was indeed the principal message conveyed by Euripides' portrait, we might well expect in his facial physiognomy a clear characterization as an intellectual. Scholars have often seen in this face framed by heavy locks of hair an expression of the supposed melancholy and pessimism that were attributed to Euripides even in antiquity on the basis of his plays, or, at least, as Luca Giuliani recently put it, a definite "Denkermimik."[25] But, once again, modern viewers, influenced by their own expectations, see more than the artist actually intended. Euripides is shown as an older man, and, as on some images of old men on the gravestones, the barely visible wrinkles in the forehead and the eyebrows gently drawn together may suggest a certain element of mental effort or contemplation, but nothing more. A comparison with

the earlier portraits of intellectuals, such as those of Pindar (fig. 7), Lysias, and Thucydides (fig. 42),[26] makes it clear that the sculptor was in no way trying to express a specific kind of mental concentration. On the contrary, the very "normality" of Euripides' old man's face presumably once again reflects the statue's true intentions. Like Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides is portrayed as an Athenian citizen, a venerated ancestor, just like those so prominently displayed on the grave monuments of wealthy families at the Dipylon. It seems appropriate, in this context, that in his one preserved oration Lycurgus praises Euripides not so much as a poet, but rather as a patriot, because he presented to the citizenry the deeds of their forefathers as paradeigmata "so that through the sight and the contemplation of these a love of the fatherland would be awakened in them."[27]

Thus in the monument proposed by Lycurgus in the very place where the Assembly met, the three famous poets were presented as exemplars of the model Athenian citizen, probably in three different guises: Sophocles as the citizen who is politically engagé, Aeschylus as the quiet citizen in the prime of life, and Euripides as the experienced and contemplative old man. Their authority, of course, grew out of their fame as poets, yet they are celebrated not for this, but instead as embodiments of the model Athenian citizen.

I should add that most of what I have been suggesting remains valid even if one questions the identification of the portrait of Aeschylus or the association of the portrait of Euripides with Lycurgus' dedication. Even if the context were otherwise, as we shall see, nothing would change in the basic conception of these portraits. The only loss would be in the programmatic interpretation within the framework of Lycurgus' political goals.