24—

Family and Household (Book I, Yconomique )

An Influential Text

Oresme's translation of the eight books of the Politics in B and D is followed by his French version of a short treatise called the Economics . Considered as the third of Aristotle's moral works after the Ethics and the Politics , the Economics centers on the economic management of the household and family relationships. Aristotle addresses these subjects in Book VIII of the Ethics in the context of friendship and in Book I of the Politics as the fundamental unit of the city-state. Modern scholarship now considers that the Economics was assembled after Aristotle's death from diverse sources, including several parts of Xenophon's Oeconomicus . The Economics was, however, mistakenly introduced into the Aristotelian corpus in the twelfth century, when Averroes composed a paraphrase of the work that figures in a Latin translation dating from about 1260.[1]

Indeed, the history of the Latin translations of the text is extremely complex, as Menut's summary in his edition of Oresme's vernacular version indicates. Menut points out that two Arabico-Latin versions preceded William of Moerbeke's Latin translation of 1267 from the Greek of Books I and III of the Economics . Book II is not included in William's work, and the third book is numbered as Book II.[2] Oresme's French version, Le livre de yconomique d'Aristote , comprises two books. The first is based on Book I of the Greek and Latin originals; the second, on Book II of William of Moerbeke's version and an anonymous Latin translation of Book III.

The Economics belongs to a genre of didactic literature relatively rare during the earlier Middle Ages. Few texts on household economy and management were written until the thirteenth century. Menut points to classical prototypes such as Hesiod's Works and Days , the previously mentioned Oeconomicus of Xenophon, Virgil's Georgics , and other works on agriculture by Roman writers, including passages from Pliny's Natural History .[3] The growth of large feudal properties provided the impetus for treatises on their management. One such work was Peter of Crescenzi's Duodecim libri ruralium commodorum of about 1300, translated into French for Charles V in 1370. The vernacular version has two titles, Le livre des prouffits champestres et ruraulx and Le livre appellé Rustican du champ de labeur .[4] Other treatises on rural economy date from the same period, including the popular vernacular version of Peter of Crescenzi's text, the first original French work on the subject by

Jean de Brie, Le bon berger of about 1375, and Jean Boutillier's La somme rurale of 1380.

The allied subject of familial relationships discussed in both books of the Yconomique is the theme of two other contemporary treatises. Le livre du chevalier de la Tour-Landry pour l'enseignement de ses filles dates from 1371 and the anonymous Le ménagier de Paris , from 1393. In a separate but notable variation addressed to women, Christine de Pizan composed in 1404 Le livre du trésor de la cité des dames (known also as Le livre des trois vertus ). In this book for women of all social classes, Christine offers practical advice on household management and personal conduct.[5] Oresme's translation of the Economics led to its incorporation in printed versions of Renaissance conduct literature. Vérard's 1489 Paris edition of Oresme's versions of the Politiques and Yconomique may have inspired the new French translation from the Latin version of Leonardo Bruni composed by Sibert Lowenborch and printed in Paris by Christien Wechel in 1532.[6] During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, various humanist treatises on the family were written, of which Alberti's Della famiglia of 1445 is the best known. Based in part on the Economics , Alberti's treatise circulated in French translations.[7] In short, the Yconomique is part of a long, multi-dimensional textual development.

Oresme's Compilation of the Text and Its Graphic Treatment

The Yconomique is the shortest of the three Aristotelian moral treatises translated by Oresme for Charles V. In B , the oldest illustrated copy of the Politics and Economics , 23 folios (373–396) make up the Yconomique , compared to 372 folios for the Politiques . A similar relationship occurs in D , where the Yconomique takes up 24 folios (363v–387) to 363 for the Politiques . Oresme notes that in logical terms the Yconomique should follow the Ethiques according to the number of people and social groups discussed in each.[8] Oresme also observes that Aristotle had discussed the household in Book I of the Politics , but to expound on the subject more fully, the Economics follows. In his translation Oresme adheres to his usual practice of dividing the text of the two books into short chapters and furnishing titles and summary paragraphs for them. Book I has seven chapters; Book II, eight. His glosses, which comprise two-thirds of the full text, are of the same types found in the Ethiques and the Politiques .[9] Oresme uses the glosses of earlier commentators such as Jean Buridan, William of Ockham, Ferrandus de Hispania, Barthélemy de Bruges, Albert the Great, and Durandus de Hispania.[10] He adds, however, original contributions in the form of cross-references to his translations of the Ethics and the Politics , other Aristotelian and classic works, as well as biblical sources. As later discussion will show, Oresme's updating and concretizing of the text contains significant observations on topics such as marriage. There are, however, only six glosses long enough to be called commentaries.[11] Furthermore, Oresme does not furnish an index of noteworthy subjects or a glossary of difficult words. At the conclusion of the Yconomique , he explains these omissions:

Cy fine le Livre de Yconomique . Et ne est pas mestier de faire table des notables de si petit livre et souffist signer les en marge. Et aussi tous les moz estranges de cest livre sunt exposés en la glose de cest livre ou il sunt exposés en la table des fors moz de Politiques .

(Here ends the Book of Economics . It is unnecessary to draw up a list of notable passages in such a small book and it is sufficient to point them out in the margins. Also, all the unusual words in this book are explained in the glosses or in the alphabetical table of difficult words in the Book of Politics .)[12]

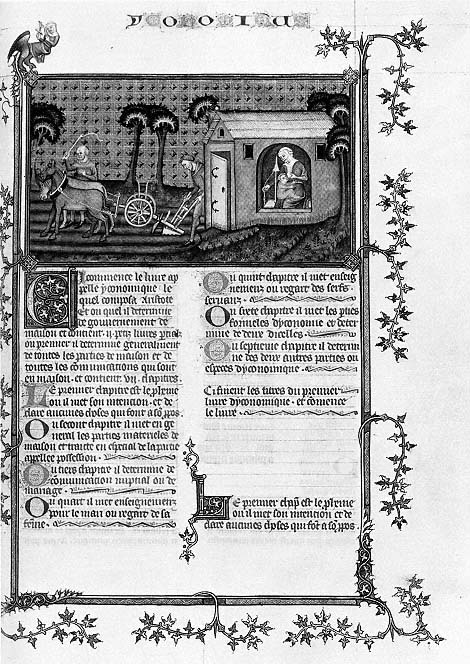

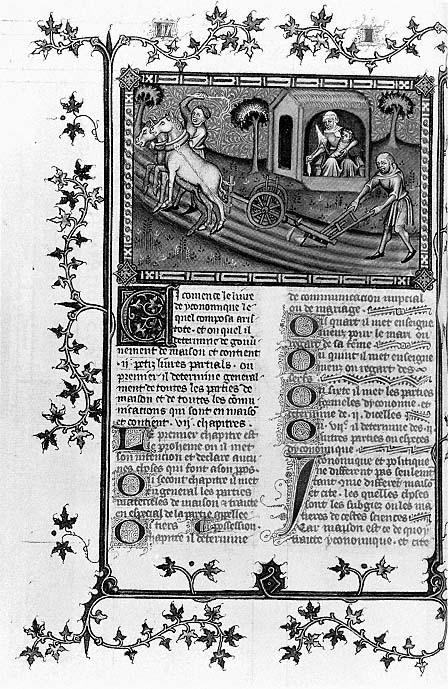

Despite the more cursory textual treatment of the Yconomique , the layout and decoration of the introductory folios of B and D adhere to the standards observed in the Politiques . In B (Fig. 80) the running title Yconomique is composed of capital letters executed in blue and rose pen flourishes. A drollery on the upper left margin depicts a hybrid woman-monster spinning: a programmatic and satiric comment on the miniature.[13] Although the summary paragraph is not rubricated, a foliate initial of normal dimensions (six lines in length) introduces the text. A smaller foliate initial L ending in two ivy leaves calls attention to the beginning of the first chapter of the text. The alternating rose and blue two-line, pen-flourished initials of the chapter titles are also characteristic of the decoration, as are the enframement and borders. In D (Fig. 81) the title of the text appears on the previous folio, although the running title for Book I occurs above the ivy-leaf upper border. Accompanied by a foliate initial C of normal dimensions, the introductory paragraph is rubricated. While the usual type of initials for the chapter titles follows, an unusual feature is the eight-line flourished initial Y introducing the first word of Chapter 1 of the text without any line separation or space following the titles. The Y in Figure 81 may compensate for the fact that the sentence in Figure 80 that announces the completion of the chapter titles of Book I and the beginning of the text was dropped in the later version.

Formal Qualities of the Illustrations and Text-Image Relationships

Figures 80 and 81 provide a unique opportunity in these cycles to compare works from the atelier of the Master of the Coronation Book of Charles V. Although this workshop is responsible for all the miniatures in D , Figure 80 marks its first appearance in the cycle of B . While an overall resemblance of figure types and composition is striking, a more searching stylistic comparison reveals that Figure 80 is the work of a more refined and subtle artist who can be associated with the best illustrations in his most famous work, the Coronation Book of Charles V .[14] Figure 81 is close to, if not identical with, a member of the workshop who executed Figure 71, the illustration of Book VI in D . Indeed, Figure 71 seems to be the model for Figures 80 and 81. The most striking resemblance lies in the motif of

the diagonal path created by the figure plowing. The reversal of direction from Figure 71 to Figure 81 suggests that a traced drawing or a model book was available to members of the workshop. A common feature of all three scenes is the farmer standing beside the horse and plowing with the help of a servant. Also repeated are the parallel rows of furrows, the thatched building framed by trees, and the stylized plant forms.

The compositions in both Figures 80 and 81 are, however, more simplified than that of Figure 71. The rectangular shape of the two Yconomique illustrations leads to a horizontally oriented composition, essentially limited to two flat surfaces. The composition of Figure 80 accentuates this horizontality, while Figure 81 constructs a diagonal suggestive of a hilly rather than a flat terrain. Figure 80 also continues the parallel emphasis by the placement and framing of the building on the right connected with the plowing action on the left. In Figure 81, however, the house and its occupants are placed at a distance from and behind the farming operation. Figures 80 and 81 also differ in color. The former adheres to the red and blue tones adopted in the rest of the cycle but adds brown, beige, and green hues for definition of naturalistic elements. Figure 81 retains the practice in D of modeling the figures in grisaille while using browns, grays, and greens. A further point of contrast is the vivid red and gold background of Figure 80 with its rigid diamond pattern that occupies more than half the rear plane and accentuates the horizontality of the composition. In Figure 81, however, the blue and gold foliate pattern of the background plays a far smaller role and is subordinate to the representation of the landscape.

While the decorative features and layout of Figures 80 and 81 do not reveal any changes from those of the Politiques , in two respects these illustrations of Book I are different. First, the dimensions of Figures 80 and 81 are noticeably reduced. Second, neither image has internal or external inscriptions. Only the illustrations for Book III of the Politiques (Figs. 60 and 61) share this characteristic. Previous discussion of the Periander tale in Book III indicates, however, that omission of an inscription may have been a deliberate strategy. Yet Figures 80 and 81 can draw on two other textual features to serve both lexical and indexical functions. In Figure 80 the prominent title serves as a verbal signal of the beginning of the book. The large initial C draws attention to the opening paragraph, which summarizes the contents of the Yconomique :

Cy commence le livre appellé Yconomique , lequel composa Aristote et ouquel il determine de gouvernement de maison. Et contient .ii. petis livres parcialz. Ou premier il determine generalment de toutes les parties de maison et de toutes les communications qui sunt en maison. Et contient .vii. chapitres.

(Here begins the book called Economics , which Aristotle wrote and in which he sets forth the rules for household management. And it contains two short, separate books. In the first, he examines broadly all the parts of the household and all the interrelated divisions of a household. And it contains seven chapters.)[15]

Figure 80

Household and Family. Le yconomique d'Aristote, MS B.

Figure 81

Household and Family. Le yconomique d'Aristote, MS D.

If further guidance is necessary to determine the meaning of the neologism yconomique , the reader can find the word defined in the glossary of the Politiques under Yconome , as "celui qui ordene et dispense les choses appartenantes a un hostel ou a une maison" (he who arranges and dispenses matters pertaining to a household or a family), and yconomie or yconomique , as "art ou industrie de teles choses bien ordenees et bien disposees" (the art or industry of such matters well arranged and ordered).[16] A further source of information about the contents of the Yconomique can be found in the chapter headings below the illustrations. Of particular interest is the title for Chapter 2: "Ou secont chapitre il met en general les parties materieles de maison et traicte en especial de la partie appellee possession" (In the second chapter he explains in general the material elements of the household and discusses particularly that part called possessions).[17] In other words, if the lack of an inscription signals the lesser importance of the Yconomique , such an omission does not deprive the reader of substantial links to the text.

Visual Structures

The undivided rectangular structure of Figures 80 and 81 is the second example of this feature in the two cycles. As was previously noted, the illustrations for Book VI of the Politiques (Figs. 70 and 71) provide the models for the setting and the overall structure of the Yconomique frontispieces. Also similar in all four miniatures is the absence of an internal inscription, which again leads in Figures 80 and 81 to an initial reading of these miniatures as simple depictions of rural life. Yet, as in Book VI of the Politiques , the illustrations contain generic visual definitions of basic concepts in Oresme's translation, as well as a paradigmatic representation interpreted as a universal model. The first source defines the essential components of the household. In the Yconomique (Book I, Chapter 2) Oresme refers to Hesiod's definition:

Et de ce disoit un appellé Esyodus qu'en maison convient que le seigneur soit premierement et la femme et le beuf qui are la terre. Et ceste chose, ce est assavoir le beuf, est premierement pour grace et affin d'avoir nourrissement et l'autre chose, ce est la femme, est pour grace des enfans.

(And on this subject, a man by the name of Hesiod stated that a household requires first of all a master and then the wife and the ox to plow the land. And the last item, that is, the ox is primarily for the purpose of producing food and the wife is

to provide children.)[18]

Oresme's gloss on this passage is worth citing:

Pour les concevoir et nourrir. Et si comme il appert ou premier chapitre de Politiques , le beuf qui are est es povres gens en lieu de ministre ou de serf. Et donques

ces .iii. parties sunt neccessaires a meson quelconque, tant soit petite ou povre, ce est assavoir le seigneur et sa femme et qui les serve. Car la femme ne doit pas estre serve, si comme il appert ou premier chapitre de Politiques . Et se aucune de ces .iii. choses defailloit en un hostel ce ne seroit pas maison complectement et proprement selon la premiere institution naturele, mes seroit maison imparfecte ou diminute et comme chose mutilee et tronchie. Item, pluseurs autres choses et parties sunt neccessaires ou convenables a meson, mes cestes sunt les premieres et les plus principales.

(To give birth to them and to feed them. And as it is pointed out in Politics , I, 1 [1252b 11, quoting Hesiod, Works and Days , 405] in a poor household, the ox that does the ploughing takes the place of a worker or serf. And thus these three items are essential to any household whatsoever, regardless of its size or wealth—that is, the master, the wife, and someone to help them. For the wife must not be a servant, as is shown in Politics I, 1 [1252b 1]. And if any one of these three things is lacking, the household would not be complete and perfect according to natural law, but would be imperfect and a miniature, as it were, a mutilated and truncated household. Several other items, are required or desirable in a household; but these are the primary and principal elements.)[19]

Thus, it is quite clear that the illustrations represent the basic elements of the household: the farmer, the servant, the wife, and the child. The economic unit is thus synonymous with the family. The farmer is also the father of the family, and the wife, the mother.

The casting of this basic economic and domestic element in terms of agriculture goes back to Hesiod. But the Economics emphasizes that cultivation of the land is the most natural way of acquiring property and riches. Oresme's text then refers to other ancient authorities, familiar from previous discussion of agriculture in Book VI of the Politiques . He invokes Virgil's Georgics to reinforce the point that cultivation of the land is the "primary occupation, because it is honest and just."[20] Moreover, gaining wealth from agricultural work is justified, inasmuch as it is natural: "car a toutes choses leur nourrissement est et vient naturelement de leur mere. Et pour ce donques vient nourrisement a homme de la terre" (for the sustenance of all things is naturally derived from their mother. And therefore man receives his sustenance from the earth).[21] In his gloss following this passage, Oresme cites Virgil, Ovid, and Ecclesiasticus to explain the equation of the earth with the mother who provides nourishment for her children: "Et donques, aussi comme l'enfant est nourri du lait de sa mere, nature humaine est nourrie des fruis de la terre et est chose naturele" (Therefore, just as the child is nourished on its mother's milk, so mankind is nourished by the earth and this is a natural thing).[22]

The Yconomique then proceeds to enumerate the moral benefits of cultivating the land. As in the discussions of Book VI of the Politiques , outdoor life is seen to be healthful, promoting fortitude and the ability to withstand one's enemies. Oresme's glosses on these passages present a positive view of rural pursuits in

which he discusses the proper types of nutrition and exercise. Although Oresme refers to the arguments in Book VI that cultivators of the land are "moins machinatifs, moins convoiteus, moins ambitieus et plus obeissans que quelconque autre multitude populaire" (less scheming, less ambitious, less envious, and more obedient than any other segment of the populace), he stresses (again referring to Virgil) a highly positive view of this way of life: "Et donques raisonnablement ceste cure ou acquisition est la premiere; car elle est juste, elle est naturele, elle dispose a bien" (Thus this occupation or means of acquiring wealth stands first, for it is honorable, natural, and it disposes men toward the good).[23]

The presentation of the relationship between the units of the household in Figures 80 and 81 also conforms to Aristotle's exposition of their economic and familial roles. The gendered division of labor within the household is a major point. In the context of the marriage relationship discussed in Chapter 3, Oresme's text states:

Et afin que l'en quere et prepare les choses qui sunt dehors le hostel, ce est le mari; et que l'autre salve et garde celles qui sunt dedens. Et convient que l'un, ce est le mari, soit puissant, fort et robuste a operation; et l'autre est fieble as negoces dehors. Et le homme est piere ou moins disposé a repos et melleur ou miex disposé a mouvemens ou a plus fors labours.

(And in order that the husband may prepare and look after the outdoor work of the homestead while the wife attends to and watches over the indoor work. And the husband must be strong, capable and robust for physical work while the wife is less able to perform outdoor tasks. And the husband is less given to repose and is more disposed to action or to the heavier occupations.)[24]

This division of labor is clearly marked in the miniature between the scene of the plowing undertaken by the male farmer and servant outdoors and the wife spinning within the cottage. Taking place simultaneously, the woman's second occupation, suckling a child, alludes to another aspect of the economic/familial relationship: the procreative function of marriage. Oresme's text says: "Et des filz la generation est propre et le utilité est commune" (The production of children is the proper task of husband and wife and the benefits are common to both the parents and the offspring alike).[25] Oresme stresses that children exist "for the sake of unity or profit."[26]

Figures 80 and 81 also express another important element of the economic/familial relationship. Oresme takes up the point that the individual units of the household work together in a cooperative manner to assure its common welfare: "Item, en communication de masle et de femelle generalement apparoissent plus les aides que il funt l'un a l'autre et les cooperations que il funt et oevrent ensemble" (When man and woman live together one observes how frequently they assist each other and cooperate and work together).[27] The collaborative nature of

the labor and marriage relationship is more clearly evident in Figure 80. Here the outdoor and indoor units are placed on the same plane and are connected by the figure of the servant that overlaps the two divisions. The door that leads inward to the cottage links it to the larger opening in which the figures of the mother and child are represented. In Figure 81, however, the outdoor labor dominates the front plane of the scene. The focus shifts to the action of plowing and the servant's importance as an essential and independently defined agent. In contrast, the cottage takes a secondary role in respect to scale and separation from the main action.

A related feature is the change in Figure 81 of the representation of the mother and child. In Figure 80 the carefully delineated movement of the mother's extended right arm and the precise representation of her distaff and spindle emphasize her labor. The direction of her gaze suggests her absorption in her work. The blue of her robe picks up the same tonality in the short jacket of her husband, on the left, and links them across the intervening field. Supported on her lap, her child is depicted as a separate, three-dimensional form naturalistically represented and emphasized by its vivid red robe. The use of red relates him to the father, who wears a cape of this color. Facing the mother, the child's sturdy body is clearly visible, as he or she reaches toward her with outstretched hands. The miniaturist thus picks out and unites the principal members of the household. In Figure 81, however, consistent with the compression of the cottage scene, common grisaille modeling does not differentiate between mother and child, with a consequent loss of their separate identities. In its swaddling clothes the child takes on a gnomelike appearance. While the mother still wields a spindle, her economic activity is subordinate to her maternal function, as she grasps the child with her left hand and looks anxiously in the direction of her husband.

The motives for these revisions are not clear. In all but one example, the illustration of Book II, the revised program of D expands the format—if not the content—of the comparable illustration in B . The effect here reduces the importance of the female unit of the household and expands the male's. No other compositional unit can share the front plane with the diagonal path. It is possible, however, that dissatisfaction arose over the programmatic equality of each unit of the household, and this may have occasioned the switch to the diagonal model.

Oresme's Interpretation of the Marriage Relationship

The treatment of the differentiated female and male roles in Figure 80 may have some connection with Oresme's innovative glosses in Book I on marriage and familial relations. Although the chillingly patriarchal tone of the Economics remains intact in Oresme's text, some scholars consider that in the glosses he makes a contribution to the companionate concept of marriage. The theme of the third chapter of Book I of the Yconomique is "the relationship of husband and wife."[28] The chapter begins with the statement that the first responsibility of every husband is to his wife. Oresme's gloss gives the reason for this argument:

Car apres le seigneur, la femme est la premiere comme compaigne. Secundement sunt les enfans et tiercement les serfs et les possessions. Apres il declaire que ceste cure doit estre premiere pour .vi. conditions qui sunt en communication nupcial de homme a femme plus que en autre communication domestique; car elle est naturele, raisonnable, amiable, profectable, divine et convenable.

(Because next to the master, the wife as his companion holds first place. The children come second and the slaves and possessions third. He next points out that this concern should be primary because of six conditions which exist in the relationship of husband to wife more than in any other domestic relationship: (1) because it is natural, (2) rational, (3) amiable, (4) profitable, (5) divine, and (6) in keeping with social conventions.)[29]

Oresme's text and gloss argue that the marriage relationship is natural because living together is necessary for sexual reproduction. But such a union is "also the fruit of reason and deliberation, and therefore it is even more natural (plus naturele ) than among the beasts."[30] Oresme goes on in the gloss to speak of love between young people as a matter of choice and joy:

Mes il avient souvent que .ii. jennes gens, homme et femme, aiment l'un l'autre en especial par election et plaisance de cuer et de amour qui est oveques usage de raison, combien que aucune fois elle ne soit pas selon droite raison.

(But it often happens that two young people, man and woman, love each other by special choice from a feeling of joy in their hearts, with a love that is accompanied by reason, even though it may sometimes happen to be without correct reason.)[31]

Oresme says that even if this love is "chaste and prepares for marriage or exists in marriage and if there is sin in it, it is a human sin."[32] In the context of the previously cited passage that man and woman live together in mutual assistance, Oresme praises the marriage relationship in terms of Aristotle's discussion in the Ethiques (Book VIII, Chapter 17). Oresme's gloss characterizes this relationship as follows: "Car elle a en soi bien utile et bien delectable et bien de vertu et double delectation; ce est assavoir, charnele et vertueuse ou sensitive et intellective" (For this friendship comprises at once the good of usefulness, the good of pleasure, and the good of virtue and double enjoyment—that is, both the carnal and the virtuous or the sensual and the intellectual pleasures).[33] The gloss says further that the sexual relationship among human beings was designed to bring about closer bonds between husband and wife. Oresme extensively quotes scriptural sources ending with Genesis to reach the conclusion that man and wife are "two persons in a single skin."[34]

In Chapter 4 Oresme's text follows Aristotle's in prescribing the rules the husband must lay down for his wife to follow. Again, although the context of the

discussion is consistently patriarchal, Oresme makes a genuine contribution to humane concepts of the marriage relationship. Not only does he speak of the husband's consideration of the wife in their sexual relationship, but he also states that he should fulfill her sexual desires. Oresme also elaborates on an ancient theme drawn from Hesiod that the husband should be older than the wife so that he can better mold her habits and preferences.[35]

Although it is impossible to draw exact parallels between Oresme's commentaries and Figures 80 and 81, certain resemblances exist. First, as mentioned earlier, the miniatures suggest the cooperative notion of marriage in the complementary labors conducted for the common good of the household. The visual structures of the illustrations also encourage the idea of the wife as companion and partner. Figure 80 may also refer to the desired age difference between husband and wife, as the former is depicted as a bald, bearded man whose appearance contrasts with that of the noticeably younger servant. It is, however, not so easy to guess the age of the wife, as she wears the concealing wimple headdress familiar from the Ethiques cycle. In short, the visual structure of the illustrations brings out in a general way Oresme's innovative comments on the marriage relationship in Book I of the Yconomique . Moreover, the sympathetic character of Oresme's remarks on marriage may have appealed to Charles V, whose relationship with Jeanne de Bourbon is known to have been an exceptionally happy one.[36] Oral explication of the companionate aspects of friendship in marriage could well have received a sympathetic hearing during the dinnertime readings mentioned by Christine de Pizan.

Social and Political Implications of the Family Unit

The similarity of Figures 80 and 81 to the miniatures of Book VI of the Politiques (Figs. 70 and 71) may have caused the text's primary readers to relate them visually and conceptually. Several themes tie them together. The first is the favorable portrayal of agricultural life. Although Oresme does not neglect to mention in a gloss the political malleability of the cultiveurs de terres , in the Yconomique this theme is less prominent than in Book VI of the Politiques . Yet common to both Figures 80 and 81 and the Bonne democracie miniatures is the impression of the social stability of the rural class.

Oresme's choice of the rural agricultural economic and family unit for visual representation derives from the text quoted above. Yet the choice of this class as an image of the household is by no means inevitable. For example, an illuminated manuscript of Oresme's translation of the Yconomique dating from 1380 to 1390 (Fig. 82) chooses a bourgeois, or nonrural, household. It seems likely, therefore, as in the Bonne democracie miniatures, that Oresme's selection of a rural family unit in some way expresses his personal and political predilection for this class.

The gendered division of labor in Figures 80 and 81 deserves further comment. As the text's citation of Hesiod indicates, the patriarchal economic and familial unit is an ancient tradition. Because of the respective labors of Adam and Eve, the

Figure 82

Household and Family. Le yconomique d'Aristote, Paris, Bibl. Nat.

clear differentiation between the masculine and feminine spheres is also sanctioned in Christian texts. Also traditional is the assignment to the male and dominant authority of an expansive exterior space, and the confinement of the female's labor to the interior. Whereas the text does not specifically mention spinning as a prescribed activity of the wife, it is an ancient stereotypical metaphor of women's labor and character, in both negative and positive senses.[37] Thus, the wife spinning in Figures 80 and 81 stands for her industrious and virtuous character, while the drollery of Figure 80 seems to comment on the insidious, devious character of women as weavers of tissues of deception. Noteworthy, too, is the conflation of labor with the traditional figure of woman as synonymous with the earth, nature, and nurture. Although the female role in the household is confined and limited to the private sphere in Figures 80 and 81, she presides over it as her unchallenged domain.[38] In short, the visual definitions reinforce the textual claim that the basic unit of the agricultural and familial unit conforms to a natural order. Harmonious relationships generically defined by class and gender assure the paradigms and models of a seemingly unchanging social and political stability.