Power and Dis-integration in the Films of Orson Welles

Beverle Houston

No movie is made by a complete adult. First of all, I don't know any complete adults.

Orson Welles

I, señor, am not one of anything, but, like you, señor, I am unique.

The Second (Dying) Art Forger, to Picasso, in F for Fake

Vol. 35, no. 4 (Summer 1982): 2–12.

I should like to thank the UCLA film archive for its generous cooperation in providing me access to these films.

In a scene of snowfall before a small house, Charles Foster Kane is cast out of his family by his newly rich mother. As generations of moviewatchers are well aware, it is to this snow scene that he returns upon his death as the text itself returns to the "No Trespassing" sign. In Magnificent Ambersons , on the other hand, family and friends spend years trying unsuccessfully to dislodge Georgie Minafer from the family mansion and the bosom of his mother. When the infant is finally forced out, he breaks both his legs. In the same film, Lucy Morgan is forced by Georgie's refusal to enter the world of men and money to return to her father and a lifetime of celibacy. Mary Longstreet in The Stranger is forced into a similar return.

Both Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons reveal a central male figure who is extremely powerful in certain ways, who can charm, force, or frighten others into doing what he wants. But the desire for control is haunted by everything that evades it. The opening of Citizen Kane , with its decayed golf course and terraces, its moss-covered gothic magnificence, reveals to us two aspects of this pattern: both the overreaching ambition and its failure—a grand life, now in ruins. Even at the height of their powers, these men are revealed to be helpless in certain realms of life, unable finally to live out their desires. Focusing on Citizen Kane, Magnificent Ambersons , and The Stranger as family-centered narratives set in the United States, with substantial reference to Touch of Evil, Immortal Story , and Chimes at Midnight for close parallels of theme and/or narrative strategies, and with passing glances at a number of other Welles films, this essay will examine the ways in which the boundless fear, anger, and desire of these figures power both narrative and image in these films.

In my own years of obsession with the Welles films,[1] I have come to call this central figure of desire and contradiction the Power Baby, the eating, sucking, foetus-like creature who, as the lawyer at the center of The Trial , can be found baby-faced, lying swaddled in his bed and tended by his nurse; who in Touch of Evil sucks candy and cigars in a face smoothed into featurelessness by fat as

he redefines murder and justice according to desire; who in his bland and arrogant innocence brings everybody down in Lady from Shanghai; who, in the framed face of Picasso, slyly signals his power as visual magician and seducer and who is himself tricked in F for Fake; but who must die for the sake of the social order in Chimes at Midnight and who dies again for his last effort of power and control in Immortal Story; and who, to my great delight, is figured forth explicitly in Macbeth where, in a Wellesian addition to Shakespeare, the weird sisters at the beginning of the film reach into the cauldron, scoop out a handful of their primordial woman's muck, shape it into a baby, and crown it with the pointy golden crown of fairy tales.

Who are these infant kings who return to early scenes, whose narratives are deflected, and whose situations are finally reversed? What do they have, and what lack? How are they both more and less than they wish to be, sometimes never reaching, but more often losing their once-great powers in the world of men and money? And what is the pattern of possibilities for their women, who are so often denied or forced into returns, whose fates are so extreme, yet so limited?

The mother of Charles Foster Kane becomes rich and powerful in a moment of transformation. She uses this power to reject Charles utterly. He is ripped untimely from a scene where he could reach whatever combination of love, fear, acceptance, and rejection that might come from the child's living out the drama of sex and power with his parents. The untimeliness of this change is suggested perfectly by the exaggeration of size relations in the Christmas shot where Charles, with his unwanted new sled, gazes up defiantly at a huge Thatcher, the money monster, on that most familial of holidays, the one based on the birth of a perfect son into a perfect family.

In the name of what does Charles's mother commit this horribly wrenching act, for which she is so eager that she has had her son's trunk packed for a week? It is true that the father moves as if to strike Charles when he pushes Thatcher. And it is true that he says: "What that kid needs is a good thrashing," moving Mrs. Kane to reply: "That's what you think, is it; Jim? . . . that's why he's going to be brought up where you can't get at him." Apparently Mrs. Kane thinks he is "the wrong father" for little Charles. Yet we have little evidence that the father has ever harmed or frightened the child. As the four talk outside the cabin, Charles moves eagerly toward his father's arms; the mother must stop him by calling his name sharply. Thus it is one of the film's most powerful and puzzling images when, at the moment of her insistence, Mrs. Kane slowly turns her head to the side as the camera dwells on her enigmatic look. Is it one of confidence for having freed her son from a struggle he couldn't win? Or one of cruel pleasure in having triumphed over father and son for their very maleness? Is she the terrible mother of myth and nightmare? Joseph McBride suggests: "It is simply that the accident which made the Kanes suddenly rich has

its own fateful logic—Charles must 'get ahead.' What gives the brief leave-taking scene its mystery and poignancy is precisely this feeling of pre-determination."[2] It must be emphasized, however, that the logic is not that of fate but of money and social class. Insisting that "this isn't the place for you to grow up in," the newly empowered mother pursues her son's "advantages" by removing him from an impoverished rural environment. She turns her son over to an agency—the bank—that she believes will protect and promote him better than the family. Yet we cannot fully escape the hint of a revenge and must accept the overdetermination of this genuinely ambiguous moment.

The role of the father needs to be understood in a different way as well. It is not his cruelty that is most significant. The fact that Fred Graves, the defaulting boarder who knew both Mr. and Mrs. Kane, left the fortune exclusively to Mrs. Kane, somehow brings Charlie's paternity into question. Did Graves leave it all to Mrs. Kane because he found the father wanting in some way—weak and whining, dependent on his wife, perhaps? Or is it Graves himself, in his unpredictable act of generosity, who is the right ("real") father? Even though we are made sympathetic with Mr. Kane—"I don't hold with signing my boy away. . . . Anyone'd think I hadn't been a good husband. . . ." (Why doesn't he say, "Good father "?)—still other negative qualities are revealed. He first tries to get little Charles to believe that his forced migration from country/family to city/bank is going to be a wonderful adventure: "That's the train with all the lights. . . . You're going to see Chicago and New York. . . ." But when Charles refuses to be fooled, the father threatens to thrash him. Thus even this "wrong father" has two faces: he who promises deceitfully, who promises pleasure where there is abandonment, and he who later threatens violence. For the boy, the father becomes the promise of worldly experience and the threat of danger, both exaggerated. Longing to cling to the beloved but mysteriously rejecting mother, unable to trust the weak and deceitful father, the boy Charles reacts with rage as his life is captured in this frozen moment.

And what of Georgie Minafer, who got out, not too early, but too late? Within the basic reversal, there are a number of similarities, particularly concerning the father. In this film, money also brings about the constitution of the "wrong" family. The agency of business is this time substituted, not for the family as a whole, but for the emotional participation of the father through Isabel Amberson's choice of husband. She marries Wilbur Minafer, a "steady young businessman," instead of Eugene Morgan, "a man who any woman would like a thousand times better." Though the local women opine that Isabel's "pretty sensible for such a showy girl," they prophesy correctly the return of the passions denied by Isabel's choice: "They'll have the worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see. It'll all go to her children and she'll ruin them." An only child receiving the full adoration of a mother who married for

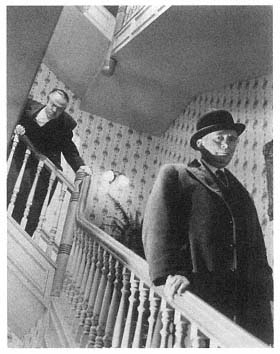

"This nest of complete dependence and desire": The Magnificent Ambersons

dollars and sense, so puny he nearly dies as an infant, young Georgie also has a father who is virtually absent. Later, when the father dies, the voice-over narrator tells us: "Wilbur Minafer. A quiet man. The town will hardly know he's gone." And Georgie hardly knew he was there. But this time the young man with the wrong father, with no father to love and hate on a regular basis, has not been sent away by the mother. Instead, we find that Georgie lives fully in a mutual state of uncontested love with the mother, secure inside a warm, dark house and a rich and fabled family. No reason to get a job or a profession. No reason ever to leave this nest of complete dependence and desire.

The theme of the wrong or displaced father is explicit in Immortal Story as well, where the primacy of money (over friendship rather than passion this time) once caused old Mr. Clay to drive away his partner, the father of Virginie. When he brings her back to her father's house (which Clay now occupies) to play out her role in his fable of seduction, he functions as a cruel "wrong father" over whom she is able to triumph. Throughout the Welles canon, fathers and mothers are doubled and tripled, offering, through displacement, the multiplications and contradictions of identity and representation. Falstaff (Chimes at Midnight)

offers one of the richest and most fluid exercises in doubling and multiplicity of father/identity. Very early in the film we are presented with Falstaff as an old man who is at the same time an innocent, the one who has been shaped by the "son" he is supposed to have corrupted. As he tells us: "Before I knew thee, Hal, I knew nothing." Later on, Falstaff puts a pot on his head and plays the role of Hal's other father, the king, chastising the boy for his bad friends and wastrel's life. Then they change roles and Hal plays his own father, the king. All the way through the film, Hal's knowledge of his impending power as future king has run concurrent with his boyish playfulness and has made all his jokes and insults to Falstaff painfully cruel, as they now are in this exchange of roles. This cruelty is, of course, prophetic of his final assumption of a fixed identity as king, which entails the rejection of Falstaff after Hal has become his own father in earnest.

The main trajectory of the plot of Citizen Kane, Magnificent Ambersons , and The Stranger turns in on itself in the pattern of a return. The child/man, unable to continue his movement toward social participation and "maturity," falls back into a childhood situation, and the woman in The Stranger is forced into a similar return. In Citizen Kane , Charlie instantly defies his substitute father and the more or less innocent energy of this rebellion carries him well into young manhood. He travels, starts to run a newspaper, behaves like an aggressive young man in the world. This phase reaches a kind of peak in his "Declaration of Principles," where he lays down the law of the sons against the corrupt fathers of the money agencies (as Thatcher had earlier laid down the law of the "Trust" to his mother), his rebellious liberalism creating a link between the youthful and the poor. But he is not content to let the words and actions of the newspaper speak for themselves. He insists on foregrounding the enunciation, as it were, revealing himself as "author" of the newspaper, unmediated by an editorial persona. This authorial gesture is merely one of the ways that young Charles reveals his huge ambition. This boy, thrown out of many elegant schools, sees himself as becoming "champion of the people." His actions reveal the exaggerated picture he has of himself and his powers, which will later be revealed in the huge poster of himself at the rally, as he sets out to win everybody's love.

Love on a personal level reveals both his overarching aspirations and his limitations. The announcement of his engagement is read in a room full of statuary he has been sending to the office—"the loot of the world"—gifts given to no one, and never enough to fill the huge empty spaces that he and the others in his life will occupy as they grow older. In his bride to be, he has acquired another high element of culture—the president's niece. But like Isabel Amberson's, Charlie's attention is only briefly engaged by his new mate. McBride suggests that Charles has a need for affection that Emily "could not gratify," but I suggest that it is Kane who will not "gratify," turning from relations within his family to activities

in which he need function only as a source of verbal or financial power, where he is never called upon to act as husband/lover/personal father. (In Immortal Story , Mr. Clay tells us that he has always avoided all personal relations and human emotions, which can "dissolve your bones.")

One night, his uncharged marriage a boring failure, his vaunting political ambitions uncertain, Charles decides to make a return to the place where his mother's goods, and his own truncated development, lie in storage. But instead, he is splashed by mud and because of this accident, the return is delayed. He comments to Susan on this deflection: "I was on my way to the Western Manhattan Warehouse—in search of my childhood."

Georgie Minafer's dream-like intimacy with his mother (as signalled by the long, slow take and dark depth of field) is suddenly threatened by a second father (the "right father?"), Eugene Morgan, who has made a return of his own. Morgan has come back to the town of his romantic defeat to try again with the soon-to-be-widowed Isabel, bringing with him a daughter (the mother is never mentioned) and a number of transformations that will be devastating for Georgie, who clings to his fixed identity as an Amberson. Trying to resist Eugene in the world of men, Georgie is ineffectual because of such misconceptions. He overestimates the power of his family identity to guarantee his superiority (or, indeed, his survival). He is wrong when he tries to ridicule Gene's invention of the automobile, and wrong again when he tries to enlist his father against the usurper by absurdly accusing him of wanting to borrow money. But he is not wrong with his mother. Oh, no. With Isabel, practically all he has to say is: "You're my mother," and she agrees to call it off with Eugene, despite his plea not to allow their romance to be ruined by "the history of your own perfect motherhood."

As in Citizen Kane , it is a sudden and unexpected change of fortune—this time a loss—that finally breaks up the family. Georgie is faced with an entirely new situation. He is alone and must support himself. His mother has died of a nameless wasting disease, having been devoured by Georgie's ravening orality. (All these Power Babies eat and eat.)[3] Furthermore, his Aunt Fanny, who has been a kind of shadowy mother double, loving instead of being loved, seeking instead of evading, who has lived only to yearn after Eugene and to feed Georgie, is now completely dependent upon him. As he goes out in the world, one prospective employer notes that he has become "the most practical young man," but only very, very briefly. Praying at his mother's empty bed, the new Georgie begs forgiveness from the Father of Fathers, but no fathers hear, for in the next cut, Georgie has an accident. An automobile knocks him down and breaks both his legs.

Let us recall here that Kane's son was killed in an automobile accident (which also claimed his wife) and that maiming of the legs is common in the Welles

canon. Recall the extreme limp and double canes of Arthur Bannister in Lady from Shanghai , the greatly reduced mobility of Mr. Clay in Immortal Story , and perhaps most complex, the bullet in the leg that Quinlan took for his friend Pete Menzies in Touch of Evil . And if the leg wound can be taken as suggesting deflected or impeded sexuality, then we must note the role of Quinlan's cane in bringing about his downfall.

Georgie has always known where the danger lies. The first night he meets Eugene and Lucy, he denigrates the automobile and wishes her father would "forget about it." Later he scorns it as useless and, prophetically in more ways than one, says it should never have been invented. Georgie's insistent and perverse dismissal of this most powerful agent of transformation is, of course, thoughtless and superficial at the rational level; he appears foolish and self-defeating, moving his Uncle Jack to remark on how strange it is to woo a woman by insulting her father. But Georgie is reacting to the car as symbol of Gene's phallic power to take away the mother love on which Georgie sustains himself so voraciously and on which, as an untried emotional infant, he believes his life depends. While others enter into mature speculation about how the automobile will change the world—Eugene himself is most confident that it will: "There are no times but new times," he says—Georgie is terrified for his life. In his identity as a new man of the future, Eugene has benefitted from an exchange of power with the Ambersons; their great fortune is gone, their living space (the home, the woman's place) is taken away, while Eugene's fortunes rise, his factories and power transformers consuming the Amberson space and returning it as a city. To move from rural safety to urban danger, Georgie Minafer need only leave the house. In his own life and in the society at large, Georgie's world of women has given way to a world of men. This shift in economy threatens him at the deepest level. Georgie has begun to fear that he will soon take his "last walk," as the narrator puts it. In the reversal implied by his seeking a "dangerous job," Georgie signals us that his fear is becoming unbearably acute.

As the automobile accident fulfills Georgie's prophetic panic, he is returned to the state of complete dependency that marked his place in the family of origin. But this time, it is a strangely smiling Eugene Morgan upon whom he must depend. Worse than Georgie's worst fears, this outcome brings, not the death that might even be wished for, but a bitter substitute for the ecstatic plenitude of mother love. For Eugene, his rival/double, it constitutes a triumph.

As the new money and usurping father brought terror and helplessness to Georgie Minafer, they bring rage and isolation to Charles Foster Kane. Once a dirty accident has deflected him from his return and brought him together with Susan, their relationship takes a strange turn. Kane almost seems to act out the role of her mother. Susan's youth is established—"Pretty old. I'll be twenty-two

in August"—and we learn that her mother had operatic aspirations for her small, untrue voice. Immediately after this revelation, we see several of the film's few conventional, romantic close-ups as Susan declares sweetly: "You know what mothers are like," and Kane answers dreamily: "Yes, I know." The mention of the mother is linked with the sign values of shallow depth, key and back lighting, and slightly soft focus, signalling Romance even more strongly than the early scene with Emily, and suggesting that Susan has tapped into Kane's deepest desires—perhaps a fantasy of a mother staying with a child, watching over it and nurturing it, causing it to grow and flourish. Susan's reaction to this impossible program is another matter, to be spoken of later.

The meeting with Boss Jim Gettys, the other key encounter of Kane's life, turns upon the role of yet another father in the family and in culture. As his mother and Mr. Thatcher seemed to be in cahoots long ago against the little boy whose weak and unreliable father did nothing to help him, now another Mrs. Kane and another usurping father move to dislodge him once again from a place where he is perhaps living out all the roles of his frozen moment, but according to a new script of his archaic desires.

With inadequate experience of father and family to mediate between his infant rage and the world of signification, Kane has imagined his rival Gettys as a monster and put that monstrous image into the public realm—newspaper pictures of Gettys "in a convict suit with stripes—so his children could see. . . . Or his mother."[4] Now Gettys must wipe out the representational power of these images. To do so, he must discredit Kane completely. Thus Gettys as powerful and successful father and son punishes Kane, not for his transgression with Susan, which stands in for the move against the father and which might have stayed a childish secret forever, but for his unbridled excess in attacking Gettys so viciously in the newspaper. Even so, Gettys is formidable but not cruel, urging Kane to do his duty and avoid family disaster by withdrawing from the race. Finally, when Kane can do nothing but scream his child-like defiance, Gettys's words are those of the elder instructing the younger: "You need more than one lesson, and you're gonna get more than one lesson." Like Georgie's, Kane's comeuppance has swept over him suddenly in a wild moment.

The image of Kane screaming down his impotent rage from the top of the steps suggests an attempt to reverse the size relations of the Christmas shot with Thatcher, and evokes similar images in a number of Welles's other films, most notably where his Macbeth, having destroyed a number of families, including that of the Kingdom itself, finally stands alone on the high wall, seeming to find a perverse ecstasy in his impotent defiance of Macduff, the outraged father (himself "untimely ripped") who has come to bring him down. In The Stranger , Charles Rankin, exposed as the Nazi Franz Kindler, screams down his defiance of Mr. Wilson, the Nazi-hunter/father figure, from the top of a clock tower.

Charlie Kane's impotent defiance of Boss Jim Gettys

Kane's destruction of the bedroom after Susan leaves is perhaps the most famous scene of rage in American film. Kane had tried to insert himself into the culture as a "celebrity" through public office—a space somewhere between that of a commodity and a well-known friend or family member. To the child of banks, being elected is perhaps like being loved. But his excess of anger cost him that public affirmation. Now the saving fantasy with Susan has failed, bringing on the wild rage. As he picks up the glass ball, Kane completes the return begun on that night when he started for the warehouse. We have already seen Kane in the newsreel with useless legs, swaddled in white like an old baby. The narrative will now offer no more events involving Kane before death causes him to release his frozen scene of trauma. After he passes through the hall of mirrors, the camera holds on the empty reflector; his identity is erased by its repetition. As Baudry says: "An infinite mirror would no longer be a mirror."[5] With his smooth head, pouting lips, and single tear, Kane is almost foetus-like, back in a primordial isolation before language, before family, before self.

As Susan walks away from Kane (and from her doll, seen in the extreme foreground as they quarrel, and seen again next to Kane's sled among the final images—he longed for his; she didn't long for hers) she also walks away from the return forced upon her by Kane. As indicated by her attempt at suicide, she

doesn't wish to continue as the child, living out her mother's fantasy or Charles's desire. Perhaps punished by her "alcoholism" for her aggressiveness in leaving Kane, certainly childishly imprudent in having spent all the money, Susan's real return has been to her position within another social class. But she is surviving, capable of working, playing, and feeling deep sympathy. Lucy Morgan in Magnificent Ambersons is also forced into a return, but a far more regressive one, and certainly of a different style. Georgie wouldn't enter the world of men and money, and Lucy certainly couldn't join him in the closed world of mother love. Therefore, as she tells him, "Because we couldn't play together like good children, we shouldn't play at all." In an idyllic out-of-doors scene, paralleling the one in which Morgan tried to convince Isabel to marry him, Lucy describes her situation to her father in the story of Ven Do Nah. This Indian was hated by all his tribe, so they drove him away. But they couldn't find a replacement they liked better. "They couldn't help it." So Lucy declares her intention to stay in the garden with her father for the rest of her life: "I don't want anything but you."

In several of Welles's films, a daughter, having made the wrong sexual choice, must return to the father. Perhaps the success of the fathers represents a displacement of the Power Baby's desired return, a metonymy in which the intensely longed-for power is muted as it moves into the quiet certainty and control of imagined patriarchal authority (yet another move in the representation of the diffuse subject). The most extreme version of the daughter's situation is developed in The Stranger . Mary Longstreet has chosen as her sexual partner not a dependent infant, not a half-baked crook like the daughter (of a white slaver) in Mr. Arkadin , but the worst possible enemy of everyone in the whole world—a NAZI! And how could this perfectly nice girl make this bizarre choice, which even her brother can't believe: "Gee, Mr. Wilson, you must be wrong. Mary wouldn't fall in love with that kind of a man." But Nazi-hunting father doubles like Mr. Wilson are not wrong. "That's the way it is," he later says, because "people can't help who they fall in love with." For "people," of course, read "women." (Remember Lucy and Ven Do Nah?)

This odd choice (and the presence of a Nazi in this New England town in the first place) can perhaps be understood by recognizing Kindler as representing difference, not only because he is a German, but in another way, because he is so closely associated with Mary. She is isolated in her connection with him. Only she has chosen him; only she supports him. In a strange way, he represents her insofar as she is one who makes a sexual choice. He is Mary's difference. For fathers, and for small-town America, this difference must be contained. In this deeply conservative film, Kindler's/Mary's difference must bring about his own downfall and her return. But his difference will also be recuperated. His exotic European hobby of fixing clocks will reinvigorate rural American tradition and law, as represented by the old town clock with its scenes of justice and revenge.

Control of the woman: The Stranger

Wilson neatly describes the trajectory of the film: "Mary must be shown what kind of man she married, even though she'll resist hearing anything bad about Charles." And despite this resistance, they are sure that her "subconscious" is their "ally," that deep inside her she has a strong "will to truth." This resource of unconscious health will, of course, lead her to relinquish her own willful difference and allow herself to be returned to her father. Thus family (again with no mother) and town will return to their original situation. A triumph of personal and social stasis.

Touch of Evil offers a more ambiguous answer to the question: can the continued presence of woman-as-difference be tolerated? One of the strangest features of this film is the often comical forced separation of Suzie and Vargas which results from the pervasive contradiction between power and impotence, the search for and denial of sexual difference in Quinlan's character. Quinlan's regression to murder and other acts of vengeance was apparently triggered by the transgression of his young wife (with a sailor, as in Immortal Story and Lady from Shanghai ). He now seeks to rewrite his own history by preventing Vargas (the double of his younger, potent self) from taking the risks of coupling. Having become a candy eater whose memory of sexuality draws him into Tanya's place, Quinlan now tries to hold on to his conservative power, which effaces sexual difference in his second partnership—with Pete Menzies—in his racism, and in his excessive acts of fixing the fate of all transgressors (they are all "guilty as hell"). We must remember that the entire action of the film was triggered by the murder of a father by his daughter's Mexican lover—from the point of view of the father, so to speak, surely a wrong choice and indication of the dangers of difference. Thus Suzie, the often absurd woman-as-sexual-difference, is drugged, and possibly raped (though even this sexuality is denied; she is lifted off the bed at the peak of the orgy scene, thus substantially altering the logistics of rape) and almost killed for expressing desire in the way she looks and acts. Throughout the

film, she is pressured by both her husband and Quinlan's people to give up the promise of sexuality and return across the border to the U.S., to "safety," to the known, the predictable, the place of before-her-sexuality—the place, ostensibly, of her father. Mexico itself, like Vargas the Mexican, represents the exercise of difference, which is constantly exploding and making trouble. In the end, it is only partially controlled. When Suzie is finally reunited with Vargas in the car, his first moves toward her are not sexual, but like those of a child who needs to lean on his mother's breast. Yet the fact of the reconciliation itself implies that the conservative force of return has been resisted to some extent. Difference has been allowed some play.

In The Stranger , the control of the woman is far more complete. The dangers of active female sexuality and choice-making take on the resonance of a national and cultural disaster. Mary's father is a New England Supreme Court Justice named Adam, and her brother is named Noah. To defy them is to endanger all that's best in American culture and in the Bible as well. To prevent this, to bring the daughter back into the fold, the two fathers, Justice Longstreet and Detective Wilson, are willing to take extreme risks—with Mary's life, that is. They decide that Kindler's attempt to kill her will be the best "evidence" to convince her of whom she has really married, so they decide to use her as bait. Wilson: "Naturally, we'll try to prevent murder being done. . . . He may kill her. You're shocked at my cold-bloodedness. That's quite natural. You're the father. . . ." Thus the fathers are split so that one can be conventionally horrified at the lengths to which the other is willing to go to bring her back into line. Then, since no other proof against Kindler exists, the gathering of evidence becomes a matter of watching Mary. Wilson: "From now on, we must know every move that Mrs. Rankin makes." Fathers, brother, and servant combine to watch and control her, but even so, she eludes them, rushing off through the graveyard to kill or be killed on the clock tower. In the end, at the top of the tower, the Nazi gets his comeuppance, brought about by the fathers, but executed by a female avenging angel just as deadly as the daughter in Touch of Evil . Kindler is impaled on the sword of the clockwork angel, screaming in pain during this dreadful parody of an embrace. Kindler deserves it, of course, at the rational plot level. But the point is that in these films, the aroused woman, the sign of difference as danger, evoking the threat of lack (inadequacy?), is not often so genteel as Lucy in Magnificent Ambersons . It is usually a struggle to force her into passivity and return, and often a lethal one.

The conservativism revealed in some of these narratives is often contradicted in the films' means of expression, which is also marked by a kind of excess. It is, of course, well known that in the Welles films, the conventions of classical cinema are either abandoned or exaggerated to fascinating extremes. The discreetly moving or subjective camera, the illusion of three-dimensionality through depth of field, become the bizarre angles, sweeping crane shots, and dwarfing depth and scale that mark several of these texts. Even expressionistic

features are taken further as light and shadow become patches of saturated darkness and blinding brightness. Citizen Kane particularly is marked by the excitement of what Julia Kristeva calls "an excess of visual traces useless for the sheer identification of objects."[6] In the projection room sequence, where light is used not to illuminate, but as having sign value in itself, and in other sequences like the travelling shot up the facade and through the sign of Susan's night club, and the shot up to the stagehand "critics" at the Opera House, these visual excesses and special effects convey a pleasure taken at the point of enunciation, an exuberance in the aggressive wielding of the language of film. Like Charles with his "Declaration of Principles," this enunciation declares itself boldly.

Later on, as Kane receives his "more than one lesson," the power of youth to transform aggressiveness into exuberance seems diminished and the tone changes. In relation to the negative narrative changes that they mark in scenes like the party with the dancing girls or Susan's suicide attempt, the wide-angle lens and extreme camera positions now seem to invite reading as signals of distress, an enunciative energy somehow grown perverse. Sometimes, as in the eerie, empty space of Jed Leland's hospital, visual work and characterization would suggest that seeing has now become the mutual recognition of grotesquery. The long, slow-moving, sinuous takes in Magnificent Ambersons , particularly in the party sequence, suggest not freedom of choice in processing a simulacrum of reality,[7] but enunciative awareness of the hopelessly desirable dream of seamless flow and oneness in the world of the mother. This movement is prefigured in the flowing overhead shots of Kane's fragmented plenitude at the end of Kane , and would have been even more pronounced in its seemingly endless withholding of expected cuts in the party sequence had the film been released as Welles intended, with reel-length shots during this portion of the film.

The excess of these images also raises the question of "evidence," which is central to a number of Welles films and which becomes dominant in all the foregrounded systems of F for Fake . In the projection room sequence of Kane , for instance, light is the elusive stuff of which delusive biography is made, no more reliable than the various embedded tales of unfulfilled desire (Leland's, Susan's, Bernstein's—remember the girl in white on the ferry boat?) that make up the film's narrative. Excessive light and shadow actually deny access to images as representations, and raise the question of how they can be used as evidence, and evidence of what, setting the act of seeing over against the structuring absence of knowledge or explanation. In The Stranger , though Wilson offers Mary filmed images of the concentration camps as evidence of her husband's evil, he does not let them stand on their own. Instead, he places himself in the image or projects the images onto himself, making his body and the field of his features into the evidence, as if asserting: "Even if the images are functional representations, trust and believe me . I who speak am the greater authority." The Stranger is one of Welles's more visually and narratively conventional films. As its "realism" is less

distressed, so the power of the law is not undermined. Wilson's authority as enunciator of diegetic truth is allowed to remain, at the partial cost of Welles's authority and presence as the film's enunciator. We observe a similar substitution of bodies (Hastler's and K's) for the "pin-screen" images of the "Law" fable where Hastler is trying to convince K of its immutability in The Trial . As Mary's body was to be watched for the invocation of evidence in The Stranger , so Virginie's sexual act will become the "final evidence" of Clay's guilt in The Immortal Story . And Pete Menzies's wiretapped body becomes the site of aural evidence in Touch of Evil , the reliability of so-called "concrete" evidence having been disposed of in the planting of the dynamite and in the history of Quinlan's entire career of manipulating "evidence." The authority of the enunciation, the aggressiveness of the intention, is substituted for the trustworthiness of the evidence itself (perhaps suggestive of the particular way in which Welles has loved to use make-up as clearly enunciated, nonrealistic masking throughout his career, combining the contradictory qualities of an identity always recognized and a disguise insisted upon with equal clarity).

The figure of the Power Baby condenses certain irreconcilable contradictions and diffusions that we have been examining in plot, character, and visual development. These can be represented through various discourses about the subversion of the unified subject. The Power Baby's constitution in doubleness is exaggerated by the failure of the family experience to mitigate the father-related excess and rage on the one hand, and the mother-related helpless dependency on the other. The family's failure, in turn, is often seen as produced not only by the woman's ability to confound the issue of paternity in a number of different ways, but also by the changing patterns of money and urbanization at different points in American history, by the ideologies that say banks are better than families for promoting children, that move Isabel to choose Wilbur Minafer, that conflate law and vengeance in border towns.

As we learn from the voice-over narrator at the beginning of Magnificent Ambersons , this ideology uses fashion, money, and media to create the only possible categories of identity into which the sexed subject must be forced. It also conflates female sexuality and lethal threats by posing difference as danger or disruption that is sometimes fully contained, sometimes a little too powerful for conservative strategies, and sometimes ironically (Immortal Story ) or fully (F for Fake ) triumphant.

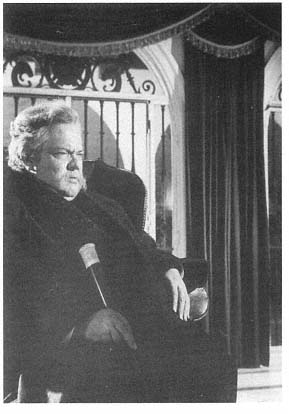

In each Power Baby, we have found an imagined social self with aspirations to greatness and total love that can only be dreams, founded in misrecognitions of both self and the social world. These mistakes are perfectly expressed in Immortal Story , where the clerk, Levinsky, tells us that Mr. Clay wants "to demonstrate his omnipotence—to do the thing which cannot be done." And within the "I" together with this overreaching social self, one and the same and

The Immortal Story

yet another, is a wildly flailing infant (we see him destroy Susan's room) fixed in incomprehension, terror, and rage, who returns to undo all social work and to reduce the organism to blank helplessness: the Wellesian "I" as the extremes of power and powerlessness.

The various stories of the Power Baby can also be seen as the refusal of the subject to be constituted in continuous narrative. Both Charles and Georgie are presented through versions of the Bildung structure that typically would move the subject from childhood through young manhood to "maturity." This form carries the conventional assumption of the infant born in powerlessness, a tabula rasa who gains experience and knowledge that become integrated into the increasing wisdom and power of the mature self. Thus in the insistence on the return to earlier scenes and conditions, these narratives deny this trajectory, using the Bildung narrative no less ironically than that of the retrospective biography.

For himself, his family, and his women, the Power Baby refuses the myth of personal harmony. Sometimes struggling for conservation and stasis, sometimes, as in F for Fake , flaunting multiplicity and difference, Welles the enunciator asserts the primacy of the individual without the comfort of the unified self.