Federal Wetlands Protection under the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899

An Historical Overview[1]

Kent G. Dedrick[2]

Abstract.—The nation's wetlands, ranging from small streams to major navigation channels, now enjoy protection under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act and Sections 9 and 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899. Both acts have increasingly been the subjects of hard-fought court actions and Congressional debate. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (CE) jurisdiction and historical developments dealing with the 1899 Act are summarized here. Examples of CE jurisdiction and permit and enforcement activities, mainly dealing with the San Francisco Bay estuarine system, are given.

Introduction

Estuaries and fresh water streams are clearly essential to California's inland and ocean fisheries. In addition, riparian wetlands and forest systems are equally dependent upon adjacent waterways, as they serve both to irrigate riparian vegetation and to provide a food supply for avian, amphibian, and mammalian inhabitants of the riparian system. Because of this, biologists, engineers, and citizens interested in these areas can profit from a basic understanding of the governmental protections that are available to prevent damage to waterways.

In some states, waterways are subject to a number of state and local laws or ordinances. But in all states, the federal Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 (1899 Act)[3] and the more recent (1972) Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (Section 404)[4] are applicable. These acts establish an important mechanism in which a permit must be issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (CE) before any "work" can be commenced in ocean waters, estuaries, rivers, streams, lakes, or in wetlands. The purpose of this paper is to provide a basic introduction to the 1899 Act and give a short history of its administration and enforcement, to review recent attacks upon the CE permit system, and to discuss the extent of CE jurisdiction. In addition, a few comments dealing with Section 404 are appropriate in order to help keep federal wetland protections in perspective.

From the standpoint of environmental protection, the jurisdiction issue is of pivotal importance. The reason for this is simply that the federal Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act[5] requires that the CE "shall first consult" the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the state wildlife agency (e.g., the California Department of Fish and Game) regarding all applications to the CE for permits in areas of waterways or wetlands under CE jurisdiction. In addition, if the proposed work is deemed sufficiently damaging to the environment, an environmental impact statement (EIS) will be required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).[6] Neither of these protections is available if the area where the work is proposed lies outside the jurisdictional limits of the CE.

The jurisdiction issue is so clearly recognized that opponents of the 1899 Act and Section 404 have concentrated recent attacks upon both laws at this critical point. In addition, recent litigation concerning application of both laws to specific proposed projects has often centered upon this same point: CE jurisdiction.

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981.]

[2] Kent G. Dedrick is Research Program Specialist, State Lands Commission, Sacramento, Calif. The views and opinions expressed are exclusively those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the State of California or the State Lands Commission.

[3] Sections 9, 10 etseq . 33 U.S.C. Section 401 et seq . Enacted 1899.

[4] Section 404, 33 U.S.C. Section 1344 (a)(t). Enacted 1972, with amendments in 1977.

[5] 16 U.S.C. Section 661 etseq .

[6] 42 U.S.C. Section 4321 etseq .

Prior to the 1972 Congressional adoption of Section 404, federal protection of navigable waters was based upon the 1899 Act alone. As will be explained below, the history of administration of the 1899 Act during the first few decades of its existence was almost serene compared with that seen following the end of World War II. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, CE administration of the 1899 Act came under sharp Congressional review. As a result, a number of badly needed reforms were instituted. These reforms exhilarated environmentalists, but a counterattack was not long in coming from a broad range of development interests.

On a separate front, during the 1960s and 1970s wildlife agencies along with hunting, fishing, and environmental groups joined together in pitched battle against federally assisted stream channelization projects (over 21,000 linear miles of natural streams in the United States had been replaced by drainage ditches by 1972). Due to a few quirks in existing law, stream channelization projects received at best only spotty environmental review, and mitigation measures were largely meaningless.

With this background, Congressional passage of Section 404 in 1972 and the court rulings in U .S . v. Holland (1974)[7] and NRDC v. Callaway (1975)[8] provided welcome protection, since these two rulings carried CE permit jurisdiction under Section 404 well into the kind of streams and wetlands that had suffered such severe devastation through stream channelization projects. A revolt against the jurisdiction and apparatus of Section 404 was quickly mobilized, and in 1976–77 the newly won broad CE jurisdiction was nearly lost in Congress; another major attack upon it is now underway. The Section 404 experience has been described in the review by Kramer (1983), and it is recommended that the reader consult this work for further details.

The origins of the 1899 Act, its later history, and CE jurisdiction under it are discussed in the following section, which in the interest of completeness also includes a brief discourse on tidal datums and their relation to CE jurisdiction under this act.

The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899

Origin and History

For many decades, the CE has been responsible for protecting and improving the waterways of the nation. This responsibility arose as early as 1824 through Congressional action aimed at improving navigation in the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, through the removal of sand bars and snags.[9] At that time, waterways were the primary highways for the young nation's commerce. With no railroads, freeways, or airlines, the CE in effect served the nation's major transportation needs in these waterways almost single-handedly.

"Almost," one should emphasize, for as early as 1795 the Third Congress spelled out the need for hydrographic surveys of the Atlantic sea-coast. In 1807, at the recommendation of President Jefferson, Congress adopted a resolution authorizing a "survey of the coast" (Shalowitz 1964). This 1807 Organic Act established the U.S. Coast Survey, which later became the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, and is now the National Ocean Services. Fortunately, the early direction of the U.S. Coast Survey aimed at achieving the highest scientific standards in performing these important tasks. As a result, their early topographic and hydrographic survey maps of United States coasts and navigable waters are today recognized as an invaluable physical and cultural research resource.

Thus the basic governmental tools needed for expanding commercial use of waterways were in place 150 years ago; namely, good navigation charts prepared by the U.S. Coast Survey, and physical improvements to navigation performed by the CE.

Throughout early European and Mediterranean history, the acts of a few often threatened to spoil waterways as pathways for commerce, and in some cases to seize control of them. It was to be no different when the United States became a nation. The matter became critical in 1888, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Willamette Iron Bridge Co . v. Hatch[10] that the federal government had no "common law" authority to protect navigable waters from obstructions. As Koonce explained in 1926 in the Koonce Lecture:

. . . while the Government was expending hundreds of millions of dollars to increase the facilities of navigation, interested parties, including States, Corporations and individuals, were placing obstructions and impediments of all kinds in and across the improved water-

[7] 373 F. Supp. 665 (M.D. Fla. 1974).

[8] 392 F. Supp. 685, 686 (D.D.C. 1975).

[9] See, for example, a lecture by Judge G.W. Koonce, "Federal Laws Affecting River and Harbor Works," Company Officer Class, the Engineer School, Fort Humphreys, Virginia, April 23, 1926 (reprinted in "Hearings on Water Pollution Control Legislation—1971," House Committee on Public Works, 92 Congress, 1st Session 286 [1971]), hereafter referred to as "Koonce Lecture.

[10] 125 U.S. 1 (31 Law Ed. 629)(1888). In this case, the Oregon Legislature in 1878 had authorized construction of a draw bridge across the Willamette River in Portland. Bridge foundations restricted the channel width to 87 ft.—it had formerly allowed passage of seagoing vessels of 2,000 tons for a mile upstream from the bridge.

way. The necessity for Federal legislation to protect these waterways from impairment and ultimate destruction eventually became urgent.

The reaction of Congress was swift. In the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1890 (1890 Act),[11] Congress authorized the basic concepts of the permit authority of the CE.[12] No longer saddled with the Willamette court's refusal to use the common law as the basis for federal authority in navigation disputes, after 1890 this authority became firmly based upon the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution:[13]

The Congress shall have Power . . . To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

There were problems with the 1890 Act and in 1896, Congress directed the Secretary of War to review existing laws and prepare revisions and amendments that he believed would be in the public interest. As an active participant, Koonce tells us that these recommendations were prepared as a bill that was to be independent of an appropriations bill, adding:

. . . but it slumbered unnoticed for nearly three years, and when we had about concluded it would never receive any attention whatever, it was taken up and passed in the most unexpected manner. (Koonce Lecture)

What happened was that while the 1899 Rivers and Harbors Appropriations Act was being considered by the Senate (it had already passed the House), Senator Frye, then Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, introduced what we now know as Sections 9 to 21 of the 1899 Act as an amendment to the appropriations bill.

This important language, said Koonce, was "accepted by Congress without the change of a word and practically without debate or discussion," (Koonce Lecture) apparently in the belief that Sections 9 and 10 did little more than restate existing law. Section 9 of the 1899 Act reads in full as follows:

It shall not be lawful to construct or commence the construction of any bridge, dam, dike, or causeway over or in any port, roadstead, haven, harbor, canal, navigable river, or other navigable water of the United States until the consent of Congress to the building of such structures shall have been obtained and until the plans for the same shall have been submitted to and approved by the Chief of Engineers and by the Secretary of the Army: Provided , That such structures may be built under authority of a legislature of a State across rivers and other waterways the navigable portions of which lie wholly within the limits of a single State, provided the location and plans thereof are submitted to and approved by the Chief of Engineers and by the Secretary of the Army before construction is commenced: And provided further , That when plans for any bridge or other structure have been approved by the Chief of Engineers and by the Secretary of the Army, it shall not be lawful to deviate from such plans either before or after completion of the structure unless the modification of said plans has previously been submitted to and received approval of the Chief of Engineers and the Secretary of the Army.

Section 10 of the 1899 Act reads in full as follows:

The creation of any obstruction not affirmatively authorized by Congress, to the navigable capacity of any of the waters of the United States is prohibited; and it shall not be lawful to build or commence the building of any wharf, pier, dolphin, boom, weir, breakwater, bulkhead, jetty, or other structures in any port, roadstead, haven, harbor, canal, navigable river, or other water of the United States, outside established harbor lines, or where no harbor lines have been established, except on plans recommended by the Chief of Engineers and authorized by the Secretary of the Army; and it shall not be lawful to excavate or fill, or in any manner to alter or modify the course, location, condition, or capacity of any port, roadstead, haven, harbor, canal, lake, harbor of refuge, or inclosure within the limits of any breakwater, or of the channel of any navigable water of the United States, unless the work has been recommended by the Chief of Engineers and authorized by the Secretary of the Army prior to beginning the same.

But much more was involved. Section 9 of the 1899 Act requires Congressional consent and CE approval before construction of any bridge, dam, dike, or causeway "over or in" navigable waters of the United States. (The 1890 Act provided such protection only in the cases of bridges and causeways.) Under Section 10 of the 1899 Act, any structure, excavation, or fill that would "alter or modify the course, location, condition, or capacity" of navigble waters of the

[11] Act of Sept. 19, 1890, Ch. 907, Section 7, 26 Stat. 454, as amended by Act of July 13, 1892, Ch. 158, Section 3, 27 Stat. 110.

[12] For a more detailed history, see Barker (1976)

[13] U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8.

United States requires a CE permit. (Under the 1890 Act, the CE could regulate only a much-narrower class of activities that would "obstruct or impair navigation, commerce, or anchorage.")

Since 1899, thousands of CE permits under Section 10 have been issued, and important court rulings affirming the validity of the CE permit program are now the classical literature on this subject. Judge Koonce worked for the CE for 40 years, beginning in 1886, and was a key figure in the development of the 1899 Act; he also continued to guide its administration for many years. He concluded his 1926 address noting that the 1899 Act:

. . . has been in force for 27 years, and in all that time there has been no amendment or suggestion of amendment. It has been contested in the courts and the constitutionality of many of its provisions has been questioned, but so far it has withstood all assaults. (Koonce Lecture)

All regulatory programs in government are subject to "assaults," and the CE permit program was no exception. The classic and continual dilemma for an agency regulator is the matter of posture under stress. Does one take a "hard line" and risk the entire program, or does one make accommodation for particular projects where undue political pressures may be exerted upon elected officials and thereby weaken or even cripple the program?

Section 9 of the 1899 Act is a case in point. Its strong language requiring approval by Congress or a state legislature for work that obstructs navigation "over or in" waterways became a case where accommodation prevailed. During his 1926 lecture, Koonce stated that Section 9 applied only "to that class of structures such as bridges and dams which extend entirely across a waterway" (Koonce Lecture)—a considerably restricted interpretation that became the administrative practice of the CE, and recently won favor in a 4th Circuit Court ruling.[14]

Since 1899, on the West Coast at least, some changes in regulatory posture have apparently occurred. For example, since 1905, in south San Francisco Bay nine Section 9 permits for dams across tidal sloughs have been issued; all were issued before 1930. During the 1930s Depression, permit activity was minimal, but, largely after World War II, at least another nine projects involving the damming of many more sloughs were either authorized under Section 10 or completed with no permit whatsoever.[15] The sloughs involved ranged in width from about 100 ft. to well over 500 ft., some have documented histories of commercial navigation, and most would be suitable for present and future uses in navigation.

Colorful history sometimes appears in CE records. For example, in 1905 CE permission was granted for a dam across Phelps Slough in south San Francisco Bay near Redwood City, and the dam was duly put in place. But unknown to District Engineer Major Wm. M. Harts, former California Governor James H. Budd owned a villa and boat dock on the slough landward of the dam site. CE records show that Governor Budd "made protest and subsequently caused the dam to be blown out." With the dam out of the way, both Budd and the operator of a schooner landing on the slough could again enjoy free navigation into San Francisco Bay. Unfortunately, at some time in the 1950s the slough was again dammed, but no permit for the dam has been located.

Two of these sloughs in San Francisco Bay were declared navigable by statute enacted by the California Legislature,[16] but despite strong citizen protest, they were eventually rendered useless for public navigation. During the years that so many waterways were lost to the public, Section 611 of the California Penal Code was in force and warned that "Every person who unlawfully obstructs the navigation of any navigable stream is guilty of a misdemeanor." Although this section was repealed in 1937, obstruction of navigable waters remains a public nuisance, subject to abatement.[17]

Criticism and Reform

As will become apparent below, an increased attack on the nation's estuaries, streams, and wetlands occurred following World War II. It seems fair to say that the attack peaked during the 1960s, but was arrested in the counterattack of increased environmental awareness in 1970. Congress had strengthened the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act in 1958, but that action did not prove sufficient to stem losses of irreplacable wetlands.

In 1967, hearings were held by the House Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation, chaired by Rep. John D. Dingell,[18] at which the extent of estuarine environment losses was

[14] Hart and Miller Islands v. Corps of Engineers , etc . 621 F 2d 1281 (1980).

[15] Corps of Engineers records, San Francisco District, San Francisco, Calif.

[16] Many California waterways have been declared navigable by statute (see Harbor and Navigation Code, Sections 101 to 106), although a statutory designation is not necessary for their judicial recognition as such (e.g., Churchhill Co . v. Kingsbury , 178 Cal. 554; 174 P. 329 [1918]).

[17] Civil Code Sec. 3479 and Code of Civil Proc. Sec. 731.

[18] Estuarine Areas. Hearings before the Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation, Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries. U.S. House of Representatives, 90th Congress, 1st Session, March 6, 8, 9, 1967. (Hereafter "Dingell Hearings".)

revealed on a nationwide basis. Dr. Stanley A. Cain, then the Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Fish and Wildlife and Parks testified that during the previous 20 years alone, 564,500 ac. of estuarine environment in coastal estuaries had been lost to dredging and filling, while another 4,300 ac. in shoal areas of the Great Lakes were lost as well. The total losses were 7% of the some 8 million acres of estuarine environment in the 26 states considered.

California's losses were cited as greater than the combined losses of the next four most heavily impacted states: Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and New Jersey. According to Cain's figures, 75% of Caifornia's estuarine losses occurred in the San Francisco Bay-Suisun Bay area. In fact, these bay area losses of 300 sq. mi. extended over a period somewhat longer than 20 years. Much of the area is diked (but not filled) and so in principle retains the potential for restoration.

During the Dingell Hearings, scenarios of the loss of many wetland areas were detailed. For example, during a brief six months in 1962, eight projects involving a total of nearly 3 million cubic yards of dredge and fill work in Hempstead Bay (Long Island, N.Y.) had been approved by the CE over strong objections by the FWS and the New York State Conservation Department. Of many other documented examples of Long Island "dredge the bays fill the wetlands" projects noted during the 1960s, some were commenced with no CE permit whatsoever, and some were even approved by the USDI Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife (BSFW). Between 1936 and 1961, 14,000 ac. of the original 30,000 ac. were lost on the south shore of Long Island alone; while as of 1952, 12.5% had been lost during the preceding five years. Testimony from other states revealed a similarly bleak picture.

Some CE procedures left the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act as an empty promise. For example, in 1963 public notices for proposed projects published by the Jacksonville District (Florida) CE contained the warning that protests must be "based on the effects on public navigation" alone, and that the federal courts had ruled that CE decisions on the permit must not be based on "considerations having nothing to do with navigation." By 1966, public notice language had improved somewhat, so that issuance of a CE permit "merely expresses the assent so far as the public rights of navigation are concerned," leaving open the door to protests on other grounds.

The Dingell Hearings were ostensibly held to consider nine bills, all containing the language: No person may conduct any dredging, filling, or excavation work within any estuary of the United States or in the Great Lakes and connecting waterways unless a permit for such work is issued by the Secretary of the Interior. That is, these bills would have required dual permits from federal agencies; one issued by the CE and one by the U.S. Department of the Interior (DI).

In the aftermath of the Dingell Hearings, Secretary of the Army, Stanley Resor, and Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, on 13 July 1967 signed a Memorandum of Understanding setting forth procedures to be followed in treating CE permit applications for work that "will unreasonably impair natural resources . . . including fish and wildlife and recreational values." In such cases, the CE will "either deny the permit or include such conditions in the permit" as will be "in the public interest." Because of this action, the dual permit legislation was dropped, and a wait-and-see posture was taken to give this new proposal a chance to prove itself. This important memorandum, and the authority of the CE to deny permits for works that would unreasonably impair natural resources, has since been affirmed in an important court action centered on Florida's west coast.

On the palm-fringed shores of Boca Ciega Bay (an arm of Tampa Bay near St. Petersburg, Florida), two landholders, Alfred Zabel and David Russel, wanted to build a trailer park on the shallow waters of the bay near its shoreline. It would be a dredge and fill operation with the dredged material piled up to form an island, connected to the shore with a dirt berm so that the house trailers could get from shore to the new island.

Zabel and Russel began obtaining local agency permits, ran into a problem, and sued in Florida courts, finally winning in Florida's Supreme Court. They next tackled the federal problem and filed application for a CE permit under the 1899 Act. A public hearing was held in November 1966, where other state and local agencies and numerous citizens protested against the project. A month later, Colonel R.P. Tabb, District Engineer, Jacksonville District, CE, recommended that although "the proposed work would have no material adverse effect on navigation," the "continued opposition of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service" as well as the other protests, "convinced me that approval . . . would not be in the public interest." Secretary of the Army, Resor, denied Zabel and Russel's application on 28 February, 1967, only a week before the Dingell Hearings commenced.

The two prospective developers and their attorneys set to work and filed a complaint in U.S. District Court a few weeks later on 10 May, 1967. They charged that the CE had no authority to deny the permit, and on 17 February, 1969, District Judge Krentzman agreed, stating that Resor did not have authority to deny a permit in cases "where he has found factually that the construction proposed . . . would not interfere with navigation."[19]

[19] 269 F. Supp. 764 (M.D. Florida, 1969).

The CE appealed Krentzman's ruling before the Fifth Circuit, and that court reversed the ruling on 16 July, 1970, in an opinion in which Judge Brown stated bluntly that "the Corps does not have to wear navigational blinders when it considers a permit request."[20]

"Hallelujah! That is great!" exclaimed Representative Henry S. Reuss on hearing news of the reversal a few days later, while he was conducting the hearings: "Protecting America's Estuaries—The Potomac" before the Subcommittee on Conservation and Natural Resources.[21] "That relieves us of new legislation!" added Representative Paul N. McCloskey, Jr., a member of Reuss' subcommittee.

To no one's surprise, Zabel and Russel appealed the Fifth Circuit's decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1971 declined to review the case. As a result, the legal apparatus for CE denial of permits on the basis of wildlife concerns (and others not substantively involving navigation) was firmly in place. The 1967 Memorandum of Understanding referred to above and the Zabel v. Tabb decision together formed the foundation that was to make the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act a powerful tool for environmental protection.

But the euphoria following the 1967 Memorandum of Understanding was to be badly shaken in October of that same year in a case involving landfill at Hunting Creek, along the west shore of the Potomac River and only 7 mi. from the nation's Capitol. The Hunting Creek affair was called a "debacle in conservation".[22]

In this case, a slim wedge of underwater property (36 ac.) jutting one-half mile out into the Potomac was proposed to be filled for apartments and crowned with a drive-in movie at its apex. The Teamsters Union Pension Fund (represented by contractor Howard Hoffman Assoc.) and an apartment firm each claimed ownership of the property, the winter home of thousands of diving ducks. The landfill would be immediately offshore from Jones Point Park (National Park Service), site of an historic (1855) lighthouse that once guided Potomac navigators.

A 1964 CE permit application was vigorously protested by the National Parks Service (NPS), FWS, six Congressmen, a U.S. Senator, and many citizen groups. Interior Secretary Stewart L. Udall asked the CE to deny the permit in the strongest terms, not only on wildlife grounds, but also claiming the fill project would "blight an area of great scenic value."

Udall's statement should have settled the matter. But it didn't. The two firms next scaled down their plans to fill about 10 ac. each initially (20 ac. total) and made new development plans for the full 36 ac. The matter languished until 10 October, 1967, when political considerations coupled with pressures for urgency led to an abrupt withdrawal of DI's objections by Assistant Interior Secretary Cain, who signed a letter on that dat prepared by "somebody else." A newspaper item[23] reported that at least two U.S. Senators had intervened for the river-fillers.

The Hoffman firm requested early action for their 9.4 ac. fill, and a CE public hearing was held in February 1968. At the hearing, the chorus of objections became an outcry; even the Daughters of the American Revolution rose up in protest. Now under intense environmental pressure and armed with a new field study, Cain reversed himself on 10 April, 1968, and immediately contacted General Harry Woodbury, Jr. of the CE. Afew days later, Woodbury concurred in the CE lower-echelon view that the permit should be granted, and bucked the controversy back to Interior Undersecretary David Black, Cain's superior. On April 26, Black also assented, and the permit was granted on 29 May, 1968.

The House Natural Resources and Power Subcommittee (Representative Robert E. Jones, Chairman) held hearings on the Hunting Creek "debacle" on 24 June and 8–9 July, 1968, and in March 1969 recommended that the CE should issue an order to show cause why the permit should not be revoked as having been "issued in violation of law." Cain resigned after the hearings, and General Woodbury had retired by the end of April 1968. Representative Reuss was later to note that "interests that want to fill and despoil always shop around until they find somebody who will give them a green light. In the Hunting Creek case, . . . the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to its eternal credit said 'No, this is an outrage, don't fill!'."[24]

In April 1969, the newly appointed Interior Secretary Walter Hickel wrote the Secretary of the Army requesting reconsideration of the Hunting Creek permit, characterizing the landfill proposal as a "needless act of destruction of the environment of the Nation's Capitol." About a year later the CE complied and revoked the permit (Sax 1971).

The wetlands battle was now fully joined. A U.S. Senate Committee held hearings in Seattle on 4 June, 1968, concerning a number of estuary protection bills;[25] but in the meantime, the cri-

[20] 430 F. 2d 199 (Fifth Circuit, 1970).

[21] See Appendix A (2).

[22] House Report No. 91–113. The permit for landfill in Hunting Creek: a debacle in conservation. Natural Resources and Power Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations. 24 March, 1969

[23] Jackson, R.L. Panel examines land deal with Teamsters Fund. Los Angeles Times, 3 January, 1969.

[24] See Appendix A (1).

[25] Estuaries and their Natural Resources. Hearing before the Committee on Commerce, U.S. Senate. 4 June, 1968.

sis over San Francisco Bay was rapidly coming to a head.

The protections provided by California's San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) were to be terminated Late in 1969. The BCDC had submitted its celebrated "Bay Plan" to the California Legislature in January 1969, but the prospect for passage of a bill ensuring a permanent BCDC with strong authority and enforcing the Bay Plan was so remote that BCDC Chairman Melvin B. Lane warned the public early that year of incipient disaster. Lane's alarm gave rise to widespread anxiety among bay area residents.

Environmental leaders met to plan strategy, but disagreed on tactics; nevertheless, an effective two-pronged campaign emerged. East Bay leaders, including the 20,000-member Save San Francisco Bay Association, adopted a major public education and letter-writing campaign. But a hard-hitting group on the San Francisco Peninsula called Save Our Bay Action Committee (SOBAC) used all the tools of a grassroots political campaign (full-page newspaper ads, press attacks upon certain legislators, major fund-raising and volunteer recruitment, bus caravans to Sacramento, etc.). This group distributed over 40,000 "Save Our Bay" bumper strips and obtained 200,000 signatures on petitions. As a result, a satisfactory bill was finally signed by Governor Reagan on 7 August, 1969 (Dolezel and Warren 1971).

After participating in the Hunting Creek affair and learning of the then-impending crisis over San Francisco Bay, Representative Henry Reuss called hearings of his Subcommittee on Conservation and Natural Resources in May 1969. These hearings were to be the first act of a prodigious program lasting through 1973, which resulted in 24 days of hearings, reporting on several thousand pages of hearing records of testimony, reports and correspondence, and dealing with nationwide issues concerning estuaries and streams.[26] This remarkable effort was the product of Reuss and six other Congressmen, assisted by a small, dedicated staff headed by Chief Counsel, Phineas Indritz.

The Reuss Subcommittee has had great impact upon federal protection of the nation's waterways; some examples are given below. Through its oversight function, the subcommittee has managed to revolutionize the administration of the CE permit system. For its part, the CE has made remarkable changes in procedures and efficiency and in cooperating with wildlife agencies and the public.

The concept of "harbor lines" originated in the 1899 Act and represented the limit to which either piers or bulkheads could be built into the nation's harbors and waterways. Permits were not required for work landward of these lines, and large tracts of estuarine lands were lost to landfill as a result. For example, in San Francisco Bay 140 mi. of harbor lines had been established by 1969, with over 19 sq. mi. of baylands shoreward of these lines (see Appendix A [1]). At Reuss' urging, the CE changed its national harbor line policy on 27 May, 1970 to require Section 10 permits in these important shoreland areas.[27]

The Reuss Subcommittee also sought vigorous enforcement of the Refuse Act of 1899, which prohibits deposit of "any refuse matter of any kind" into the navigable waters of the United States.[28] Court rulings have established that a wide variety of industrial pollutants are classified as "refuse," and thus the discharger faces both civil and criminal sanctions under this act[29] Furthermore, Section 16 of the 1899 Act[30] contains the surprisingly modern idea that a citizen "giving information which shall lead to conviction" may be awarded one-half of the fine imposed on the discharger.

Enforcement of Section 10 of the 1899 Act has always been a difficult matter. Despite the existence of the BCDC and other agencies having enforcement authority in the San Francisco Bay area, illicit filling of the bay continued with disturbing frequency during the early 1970s. Upset with this situation, a handful of citizens became informers and reported many unpermitted bay dumping incidents to the CE and other agencies.[31] The best known example is the case where Mrs. Sylvia Gregory, hospitalized with a broken leg near the San Francisco International Airport, viewed illegal filling in progress at the airport and reported to the CE from her hospital bed.[32] Due to the extensive publicity surrounding these illegal fills, their frequency has decreased. However, eternal vigilance is mandatory to prevent a return of the prior "dump-it-in-the-bay" attitude that had been so destructively commonplace for over a century.

One might ask if the CE permit system that had been strengthened during the early 1970s was prepared to resist a major landfill proposal that would be seriously damaging to ecological values. The answer came in 1976 when the CE under Sections 10 and 404 denied two out of three permits applied for by the Deltona Corporation for dredge and fill work at Marco Island on Florida's south-

[26] U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Government Operations, Conservation and Natural Resources Subcommittee. Representative Henry S. Reuss, Chairman. Hereafter cited as "Reuss Subcommittee." See Appendix A for a list of hearings and reports from 1969 to 1973.

[27] See 33 Code of Federal Regulations Part 328. Code of Federal Regulations hereafter "CFR."

[28] Section 13 of the 1899 Act (33 U.S.C. Section 407).

[29] See Appendix A (7), (12), and (16).

[30] 33 U.S.C. Section 411.

[31] Adams, G. The Big Snitchers. California Living, supplement to San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle. 5 March, 1972.

[32] Congressional Record. 21 October, 1971.

ern Gulf coast. The project involved 18.2 million cubic yards of dredge and fill work in more than 2,100 ac. of mangrove wetlands and 70 mi. of waterways, the purpose being to create over 5,600 house lots.

According to testimony by the DI,[33] "the developer continue(d) to sell submerged lots in this tract without the Federal permits necessary to make the submerged lands suitable for the erection of residences." Lt. General William C. Gribble, Jr. (CE Chief of Engineers) said in denying the permits that the proposed filling of the mangrove wetlands would "constitute an unacceptable adverse impact on this aquatic resource" that would be contrary to "overriding national factors in the public interest."[34] The entire project had been started 12 years earlier, and the CE granted the permit for the "Collier Bay" part of the project because, as Gribble pointed out, "a significant amount of destruction has already occurred to the mangrove wetlands" in that area and a number of houses had already been built.[35]

Despite this dramatic victory for environmental interests, nagging problems persist. CE jurisdiction in specific wetland areas has often been removed by Congress through insertion of brief phrases in the language of other bills, such as the Public Works Omnibus Bill. For example, in 1968 the waters and waterfront of a major portion of the port of San Francisco were "declared to be nonnavigable waters" and that "the consent of Congress is hereby given for the filling in of all or any part" of the area.[36] Similarly, in 1976 Congress approved language stating that Lake Coeur d'Alene (Idaho), Lake George (New York), and Lake Oswego (Oregon) "are declared nonnavigable" under the Section 10 permit program.[37] Many other waterways have suffered the same fate; they are listed in Title 33 of the U.S. Code from Section 21 through Section 59p.

San Francisco is a major ocean port, but during the late 1960s a plan was advocated to fill part of the port area for office and commercial use. This project probably triggered Congress' action to declare the area "nonnavigable."

The curious history of the Lake Coeur d'Alene case was revealed during U.S. Senate hearings called by Idaho's Senator James McClure and held in October 1974.[38] Months earlier in January 1974, the CE had declared the lake to be "navigable waters of the United States" following an extensive investigation which showed the lake had been used for commercial steamboat navigation as early as 1854 and continues to be. In September, McClure introduced a bill to give CE permit authority to the State of Idaho. The bill apparently failed to become law, but only two years later the lake was declared "nonnavigable" as noted above.

In addition to the above "nonnavigable" declarations, some interests have taken complaints of recent CE and FWS actions to Congress. For example, hearings were held in 1975[39] as a forum for officials of Foster City and Redwood City to express their displeasure with FWS, which had requested meaningful mitigation for losses in waterfowl habitat connected with three projects proposed over the prior two years. These projects were continuations of earlier large projects that had created over 3,000 ac. of dry land by filling former San Francisco Bay marshlands; they were substantially financed using tax-exempt bonds. The hearings are of concern as they represented a formal and vigorous protest against a wetlands protection apparatus still in its infancy.

Navigable Waters of the United States

As late as 1972, the definition of navigable waters of the United States published in Title 33 CFR could only be described as narrow.[40] Four U.S. Supreme Court decisions were then used by the CE in defining navigability:

The Steamer Daniel Ball v U .S . (1871);[41

]U .S . v The Steamer Montello (1874);[42

]Economy Light & Power Co . v U .S . (1921);[43

]U .S . v Appalachian Elec . Power Co (1941).[44]

The Daniel Ball and Montello cases provide definitions of navigability that are highly conservative by today's standards, while the Economy and Appalachian cases, coming several decades later, reveal an awareness of the threat to

[33] See Appendix A (9).

[34] News release. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Jacksonville District, Florida. 16 April, 1976.

[35] For additional information on the saga of Marco Island see Environmental Law Review 6:10117 (1976). Corp. confirms policy against 'unnecessary' development in wetlands. See also Carter (1976).

[36] 33 U.S.C. Section 59h.

[37] 33 U.S.C. Section 59m.

[38] Structures, excavations, or fills in or on certain navigable waters. Hearings before the Subcommittee on Water Resources, Committee on Public Works, U.S. Senate, 93rd Congress, 2d Session. October 7, 1974.

[39] Roles of the Corps of Engineers and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Foster City, Calif. Hearings before Conservation, Energy, and Natural Resources Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations, U.S. House of Representatives, 94th Congress, 1st Session; 12–13 September, 1975.

[40] See, for example, 1971 edition of 33 CFR Section 209.260.

[41] 77 U.S. (10 Wall.) 557.

[42] 87 U.S. (10 Wall.) 430.

[43] 256 U.S. 113.

[44] 311 U.S. 377.

waterways that is refreshing by contrast.[45] The court's language in the Daniel Ball case may be of help to scientists and engineers seeking historical guidance:

Those rivers must be regarded as public navigable rivers in law which are navigable in fact. And they are navigable in fact when they are used, or are susceptible of being used, in their ordinary condition, as highways for commerce, over which trade and travel are or may be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water.

The Montello case language noted that "the capability of use" in waterborne commerce is the "true criterion" of navigability, but added:

It is not every small creek in which a fishing skiff or gunning canoe can be made to float at high water which is navigable, but in order to give it the character of a navigable stream, it must be generally and commonly useful to some purpose of trade or agriculture.

The Economy Light ruling added the important indelible navigability concept that can be paraphrased as "once navigable, always navigable." The court remarked:

The fact, however, that artificial obstructions exist capable of being abated by due exercise of public authority, does not prevent the stream from being regarded as navigable in law, if, supposing them to be abated, it be navigable in fact in its natural state.

The Appalachian ruling supercedes the prior cases in at least one important area:

To appraise the evidence of navigability on the natural condition only of the waterway is erroneous. . . . A waterway, otherwise suitable for navigation is not barred from that classification merely because artificial aids must make the highway suitable for use before commercial navigation may be undertaken.

On 9 September, 1972, the CE published in the Federal Register an expanded and updated definition of navigable waters of the United States that now appears in Title 33 CFR, Section 329 (first published as Section 209.260). This new material provides the most important guidance available dealing with the CE claim of jurisdiction under the 1899 Act. As such, it is an essential reading assignment for anyone seriously interested in the act. An "Attorney's Supplement" prepared by the Office of General Counsel, CE, provides detailed legal background for the new definition and contains an encyclopedic number of legal references, in sharp contrast to the definitions used before 1972.

At 33 CFR Section 329.4, a general definition of navigable waters of the United States is given:

Navigable waters of the United States are those waters that are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide and/or are presently used, or have been used in the past, or may be susceptible for use to transport interstate or foreign commerce. A determination of navigability, once made, applies laterally over the entire surface of the waterbody, and is not extinguished by later actions or events which impede or destroy navigable capacity.

For non-tidal waters, the jurisdiction extends to the ordinary high-water mark, which is defined as:

'The ordinary high water mark' on non-tidal rivers is the line on the shore established by the fluctuations of water and indicated by physical characteristics such as a clear, natural line impressed on the bank; shelving; changes in the character of soil; destruction of terrestrial vegetation; the presence of litter or debris; or other appropriate means that consider the characteristics of the surrounding areas. (33 CFR Section 329.11[l])

It is also stated that private ownership of a river- or lakebed "has no bearing on the existence or extent of the dominant Federal jurisdiction over a navigable waterbody."

The shoreward limit of jurisdiction in coastal areas "extends to the line on the shore reached by the plane of the mean (average) high water," which, if possible, should be based upon 18.6 years of tidal measurements to account for the precession of the moon's orbit in relation to that of the sun.[46] In bays and estuaries, the CE jurisdiction:

. . . extends to the entire surface and bed of all waterbodies subject to tidal action. Jurisdiction thus extends to the edge [as determined by 33 CFR Section 329.12(a)(2) above] of all such waterbodies, even though portions of the waterbody may be extremely shallow, or obstructed by shoals, vegetation, or other barriers. Marshlands are thus considered 'navigable in law,' but only so far as the area is subject to inun-

[45] These rulings have been described frequently (e.g., Barker 1976; Leighty 1970).

[46] 33 CFR Section 329.12(a)(2).

dation by the mean high waters . . . . (33 CFR Section 329.12[b])

The 1972 definition (as amended in 1977) thus includes many areas that had not been specified in prior definitions. Jurisdiction over the "entire surface" of a waterway arose from the 1961 Supreme Court decision in U.S . v. Virginia Electric and Power Co .,[47] which in turn cited other cases to the same effect.

During the 1969 Reuss Subcommittee hearings on San Francisco Bay (Appendix A [1]), Brig. General William M. Glasgow, Jr. testified that "the Corps has exercised jurisdiction in the Bay based upon long-established mean higher high waterlines," and that "the levees constructed by Leslie Salt Co. are shoreward of such lines and no permits were therefore necessary." In 1970, objections were made on factual grounds to Glasgow's remark that the mean higher high water (MHHW) lines were "long established"; it was thus suggested that the CE did not know the true extent of its jurisdiction in present and former bay tidal marshlands (see Appendix A [15]). After considerable debate, the San Francisco District, CE, issued Public Notice No. 71-22(a) in January 1972 stating that under the 1899 Act: "Permits are required for all new work in unfilled portions of the interior of diked areas below former mean higher high water."

As a result, a sizeable but unknown fraction of the historic 313 sq. mi. of San Francisco-Suisun Bay marshlands (Nichols and Wright 1971) was clearly placed under Section 10 protection. Because Leslie Salt claimed about 70 sq. mi. of these lands, it was directly affected by the CE action and, on 20 December, 1973, filed suit against the CE, arguing that CE jurisdiction was restricted in both Sections 10 and 404 to the mean high water (MHW) line. It should be noted that Pacific Coast tides are of the "mixed" type in which the two daily high tides usually differ considerably in height. MHHW is the average of the higher of the two daily high tides, while MHW is the average of all high tides. In San Francisco Bay, MHHW is only 7 in. higher than MHW.

District Court Judge William T. Sweigert disagreed with Leslie's contention and set former MHHW as the jurisdictional limit under Sections 10 and 404.[48] On appeal, the 9th Circuit panel partially reversed Sweigert, ruling that the 1899 Act jurisdiction "extend(s) to all places covered by the ebb and flow of the tide to the mean high water (MHW) mark in its unobstructed natural state," and that under Section 404 the jurisdiction is not limited to either MHW or MHHW.[49]

Tidal Phenomena

Anyone involved in coastal and estuary studies needs a good understanding of both the theoretical and practical aspects of tides. For the most part, the theoretical knowledge needed involves an elementary understanding of astronomy and the methods of computation of simple averages in order to establish "mean high water" and other tidal datums (Marmer 1951; Schureman 1949). It is also useful to understand the methods used for obtaining these datums accurately from short series of measurements (Swanson 1974).

In addition to average values, other statistical properties of tides are increasingly being recognized as important in many scientific and engineering pursuits in the shorezone. The frequency and height of extreme high tides control the design of flood control structures and are critical in determining the dividing line between upland and aquatic vegetation. At elevations below these extreme high tides, the frequency of inundation by tide waters is an important factor in the survival and propagation of aquatic flora and fauna, and many opportunities exist for new multi-disciplinary research that joins land surveying techniques, tidal statistics, and biology (Hinde 1954; Cameron 1972; Silva 1979).

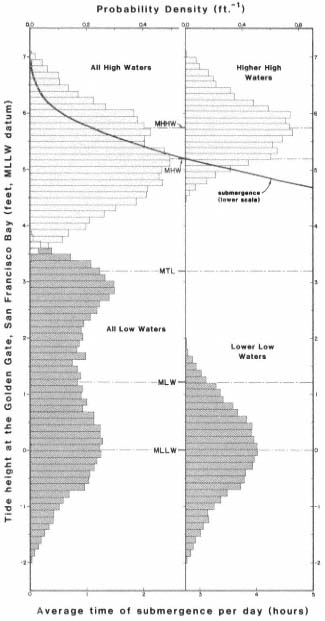

A statistical analysis of 19 years of predicted high and low tides for 55 stations on all United States coasts including Alaska and Hawaii has been prepared by Harris (1981). Tabular entries and graphs given in this work indicate the probability that tides higher (or lower) than a given level will occur, and also provide the frequencies of high and low tides within small elements of elevation. Figure 1 was prepared using Harris' results and shows the probability densities for high and low tides as functions of tidal elevation for the Golden Gate, San Francisco Bay. It can be seen that high tides range in elevation from about 0.2 ft. above mean sea level (MSL) to nearly 4.0 ft. above MSL. The probability density for high tides has a standard deviation s = 0.74 ft., resembles a gaussian error curve with that value of s , and is nearly symmetrical about mean high water (MHW). Some 97% of all high tides fall within the height range from 2s above MHW to 2s below MHW.

Also shown in figure 1 is a curve giving the average number of hours of submergence per solar day as a function of tide height. The curve shows an average submergence of about 65 minutes at the elevation of MHHW, and about 2 hours 45 minutes at the elevation of MHW.

As noted above, the jurisdiction of the CE under the 1899 Act has been restricted on the West Coast to the MHW mark in its "natural, unobstructed state." This same mark is also the limit of state sovereign land title claims (Stevens 1980; Taylor 1972). Yet it is clear that for a symmetrical high water probability density function, 50% of all high tides are above MHW, while the other 50% fall below it. This means

[47] 365 U.S. 624 (1961).

[48] Sierra Club v Leslie Salt Co . and Leslie Salt Co . v Froehlke . 412 F. Supp. 1096 (1976).

[49] Leslie Salt Co . v Foehlke and Sierra Club v Leslie Salt Co . 578 F. 2d 742 (1978).

Figure 1.

Statistics of predicted tides for the Golden

Gate, San Francisco Bay, for the 19-year

period: 1963–1981. (Source: Harris 1981.)

that the lands above MHW that are inundated by one-half of all high tides do not receive protection under the 1899 Act or under state sovereign claims, even though these lands are of great importance in marine engineering, flood control, and the general biological health and productivity of an estuary. Fortunately, Section 404 provides regulatory protection for such areas, but only if they satisfy wetlands criteria spelled out in CE and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations and guidelines.

Finally, a few remarks are in order concerning the natural role of tidal flooding of saltmarsh and other estuarine areas in maintaining navigation channels and reducing the need for maintenance dredging. In 1860, Henry Mitchell, Chief in Physical Hydrography of the U.S. Coast Survey summarized his own studies with the carefully worded statement:

GENERAL RULE. A river having a bar at its mouth will be injured as a pathway for navigation if the tidal influx is reduced by encroachments upon its basins.[50]

This General Rule makes a direct connection between the goals of estuarine wetlands protection and restoration with the needs of navigation. This basic principle is familiar to students of historic works dealing with harbor design, but is seldom discussed in modern harbor engineering texts and reference works; primarily because harbor water depths needed by increased sizes of freighters and tankships over recent decades can generally be met only by instituting major dredging projects. However, application of Mitchell's General Rule as a guide can spell the difference between high and low maintenance dredging costs for flood channels and small craft harbors.

Conclusion

The flow of events—legislative and judicial—leading to the Section 404 wetlands protections has been dramatic, to say the least (see e.g., Kramer 1983). The 1976–77 Congressional debate over the Breaux and Wright amendments to Section 404 (authored by Representatives John Breaux [D-La.] and James C. Wright, Jr. [D-Tex.]) commenced quietly in a House Committee meeting on 13 April, 1976 and rose to a crescendo of head-on confrontations during Senate and conference committee meetings and floor actions lasting well into 1977, when amendments to the Clean Water Act were finally approved.

At the 13 April meeting, Breaux's short (115 word) amendment was adopted on a 22-13 vote of the House Public Works and Transportation Committee, with no input whatsoever from DI, EPA, CE, or the public. Breaux's language would have added two subsections to Section 404:[51]

[50] Mitchell, H. On the reclamation of tidelands and its relation to navigation. Appendix No. 5, Report of the Superintendent, U.S. Coast Survey. House Exec. Doc. No. 206, 41st Congress, 2d Session (1869).

[51] Section 404 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act amendments of 1972. Hearings held on 27–28 July, 1976 before the Committee on Public Works, U.S. Senate, 94th Congress, 2d Session. Cited hereafter as "404 Hearings".

(d) The term 'navigable waters' as used in this section shall mean all waters which are presently used, or are susceptible to use in their natural condition or by reasonable improvement as a means to transport interstate or foreign commerce, shoreward to their ordinary high water mark, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide shoreward to their mean high water mark (mean higher high water mark on the west coast).

(e) The discharge of dredged or fill material in waters other than navigable waters is not prohibited by or otherwise subject to regulation under this Act, or section 9, section 10, or section 13 of the Act of March 3, 1899.

Public rights in waterways are guaranteed by many state and federal statutes and have been the subject of judicial rulings in the highest courts of both the United States and England. These rights have other precedent through colonial charters of the original thirteen states in English Common Law, which in turn have roots in the Magna Carta of 1215 and the Pandects of Justinian (Roman Law) of far earlier vintage. Subsection (d) of the Breaux amendment curiously tries to replace several hundred years of ruling and precedent by a definition of "navigable waters" merely 76 words long, omits "waters that have been used in the past" for navigation, and omits noting that such waters are to be taken up to the head of navigation. Under Section 404, the Breaux amendment also eliminates vast acreages of adjacent wetlands, vernal pools, prairie potholes, and other vital wetlands from protection. Indeed, one agency in 1976 estimated that only 10 million acres of the 70 million wetland acres remaining in the contiguous 48 states would still be protected. The remaining 60 million acres would be left with no significant federal protection.

Breaux's language was adopted by Representative Wright, and the resulting Wright-Breaux amendment was passed by the full House on 3 June, 1976, after a short, heated debate, on a 234 to 121 vote.

Nearly two months were to pass after the House approval before any public hearings were held on the matter. In two evening sessions on 27–28 July, 1976, the Wright-Breaux language was considered as an amendment to S. 2710 (Hart) by the Senate Committee on Public Works, chaired by Senator Jennings Randolph. The hearings stimulated a massive outpouring of views that led to a 794-page report by the committee.[51] A full description of the testimony presented is far beyond the scope of this review, but supporters of Wright-Breaux included the National Governors Conference and private interest groups associated with coal and other mining, highway construction, forest harvesting, real estate, farming, livestock, reclamation districts, and residential and commercial builders. Opposed to Wright-Breaux were groups and individuals interested in the general environment, sports and commercial fishing, and state and federal wildlife agencies.

Of more than passing interest is the testimony of Peter R. Taft, Assistant U.S. Attorney General, Land and Natural Resources Division. Taft testified that it had been frequently alleged that the CE 404 permit program is "a creation of the courts rather than Congress and transcend(s) the constitutional basis for regulation in navigable waters." Taft sharply claimed this allegation is in error, and in support of his claim provided a brief but pointed history of the public's rights in waterways and of efforts in the United States to halt water pollution, starting with Magna Carta and tracing both the legislative and judicial histories of these concepts in the United States.

Citing a number of examples in the nation, Taft also remarked:

. . . a number of the cases referred to the Justice Department for litigation have involved entities and individuals exhibiting as many characteristics of greed, fraud and outright criminality as I have ever seen in the business world. The worst have involved land developers drawn by the smell of cheap land that can be dredged and filled, often with canals, then subdivided and sold with heavy sales pitches for large front-end profits. Many of them are thinly financed. Most attempt to complete the dredging and make sales before the Corps finds out about the project; they then attempt to avoid restoration of the wetlands on the ground that they will go bankrupt and that innocent purchasers would be stuck with submerged lands they can't use.[51]

Even though the Wright-Breaux amendment was finally defeated in the Senate in 1977, bills with the same thrust have appeared frequently since then. Language identical or substantially similar to Breaux's can be found in the 1980 bills; S. 2970 (Tower), H.R. 7250 (Paul), and others pending before Congress at the time of this writing: S. 777 (Tower and Bentsen), H.R. 3083 (Hall).

The CE permit system has also been weakened in other ways. For example, the 1967 Memorandum of Understanding, referred to above, required "elevation" to Washington for settlement of unresolved differences between local officials of the CE and FWS regarding wildlife impacts of proposed projects. This memorandum was "terminated" on 24 March, 1980 when new language was adopted.[52] On 2 July, 1982 Interior Secretary James

[52] Federal Register 45:62768-71 (September 19, 1980).

Watt and others approved yet other language that allows the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works) to refuse review of contested permits by Washington officials.[53]

In addition, the definition of "fill material" under Section 404 was changed by the CE in 1977 so that it "does not include any pollutant discharged into water primarily to dispose of waste . . ."[54] This means that garbage disposal in the nation's waters or wetlands is exempt from CE environmental review under Section 404 and requires instead a NPDES (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permit under Section 402 of the Clean Water Act. As a result of this loophole, new garbage dumps are today being created or expanded in diked wetlands of San Francisco Bay, despite the strong admonition by the Reuss Subcommittee in 1970 that "use of the Bay as a refuse dump is inimical to the national policy of preventing the destruction of our estuaries and must be stopped."[55]

Recent developments herald that a new round in the wetlands battle over both Section 10 and 404 has already begun (Mosher 1982). During 1976 and the preceding decade, progress in the development of wetlands protective laws and court rulings—and the defense of them against attack—occurred during both Republican and Democratic administrations, while Presidents Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter served in office; administration support of wetlands protection was the rule during that era. Numerous research investigations conducted during those years also provided a sound scientific, engineering and economic basis that justifies protection of wetlands as a resource of nationwide importance. This factual material coupled with long-term political and judicial support has given great credence to the proposition that the protection of wetlands is a national goal, and clearly in the public interest.

But times have changed, for we now see the administration apparently operating in concert with a substantial Congressional power block bent upon reversing the wetlands protections gained over the past 15 years. Thus stripped to the core, wetlands defense will have to increasingly rely upon informed public opinion.

Literature Cited

Barker, Neil. 1976. Sections 9 and 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899: potent tools for environmental protection. Ecol. Law Q. 6:109–159.

Cameron, G.N. 1972. Analysis of insect trophic diversity in two salt marsh communities. Ecology 53:58–73.

Carter, L.J. 1976. Wetlands: denial of Marco permits fails to resolve dilemma. Science 192:641–644.

Dolezel, J.N., and B.N. Warren. 1971. Saving San Francisco Bay: a case study of environmental legislation. Stanford Law Rev. 23: 349.

Harris, D.L. 1981. Tides and tidal datums in the United States. Spec. Rept. No. 7, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Coastal Research Engineering Center, Fort Belvoir, Va. 382 p.

Hinde, H.P. 1954. Vertical distribution of salt marsh phanerogams in relation to tide levels. Ecol. Mono. 24:209–225.

Kramer, J.R. 1983. Is there a national interest in wetlands: the Section 404 experience. In : R.E. Warner and K.M. Hendrix (ed.). California Riparian Systems. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981.] University of California Press, Berkeley.

Leighty, L.L. 1970. The source and scope of public and private rights in navigable waters. Land and Water Law Review 5:391–440.

Marmer, H.A. (ed.). 1951. Tidal datum planes (revised). Special Pub. No. 135, U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 142 p.

Mosher, L. 1982. When is a prairie pothole a wetland? When federal regulators get busy. National Journal 14(10):410–414.

Nichols, D.R., and N.A. Wright. 1971. Preliminary map of historic margins of marshland, San Francisco Bay, California. Open file map, USDI Geological Survey, Menlo Park.

Sax, Joseph. 1971. A little sturm and drang at Hunting Creek. Esquire Magazine. February, 1971.

Schureman, P. 1949. Tide and current glossary (revised 1975). Special Pub. No. 228, National Ocean Survey/NOAA. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 25 p.

Shalowitz, A.L. 1964. Shore and sea boundaries. Vol. 2. Pub. 10-1, U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Government Printing Office, Washington. D.C. 749 p.

[53] Unpublished Memorandum of Agreement between the Department of the Interior and the Department of the Army. Dated July 2, 1982, and signed by Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt; Secretary of the Army John O. Marsh, Jr.; Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works) Wm. R. Gianelli; Assistant Secretary of the Interior (Fish and Wildlife and Parks) G. Ray Arnett; and USDI Fish and Wildlife Service Director Robert A. Jantzen.

[54] 33 CFR Section 323.2(m); (1980 Ed.). First published in the Federal Register 42:37144 etseg (July 19, 1977).

[55] Appendix A (11).

Silva, P.C. 1979. The benthic algal flora of central San Francisco Bay. In : T.J. Conomos (ed.). 493 p. San Francisco Bay: the urbanized estuary. Pacific Division, American Association for the Advancement of Sciences, San Francisco, Calif.

Stevens, J. 1980. The public trust: a sovereign's ancient prerogative becomes the people's environmental right. UCD Law Rev. 14: 195–209.

Swanson, L.R. 1974. Variability of tidal datums and accuracy in determining datums from short series of observations. NOAA Technical Report NOS 64, National Ocean Survey/NOAA, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 41 p.

Taylor, N.G. 1972. Patented tidelands: a naked fee? Calif. State Bar J. 47:420.

Appendix A

The following is a list of the hearings and reports of the Committee on Government Operations, Conservation and Natural Resources Subcommittee, U.S. House of Representatives, Representative Henry S. Reuss, Chairman.

Hearings

1. The nation's estuaries: San Francisco Bay and Delta, Calif. Part 1: 15 May, 1969, Part 2: 20–21 August, 1969.

2. Protecting America's estuaries: The Potomac. 21–22 July, 1970.

3. The establishment of a national industrial wastes inventory. 17 September, 1970.

4. Refuse Act permit program. 18–19 February, 1971. Senate Commerce Committee with participation by the Reuss Subcommittee.

5. Stream channelization. Parts 1–4: 3–4 May, 3–4, 9, 10, and 14 June, 1971; Part 5: 20 March, 1973.

6. Public access to reservoirs to meet growing recreation demands. 15 June, 1971.

7. Mercury pollution and enforcement of the Refuse Act of 1899. Parts 1 and 2: 1 July, 21 October, and 5 November, 1971.

8. Protecting the nation's estuaries: Puget Sound and the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. 10–11 December, 1971.

9. Protecting America's estuaries: Florida. Parts 1 and 2: 25–26 May, 1973.

Reports

10. Our waters and wetlands: How the Corps of Engineers can help prevent their destruction and pollution. House Report 91–917, March 18, 1970.

11. Protecting America's estuaries: The San Francisco Bay and Delta. House Report 91–1433, August 19, 1970.

12. Qui tam actions and the 1899 Refuse Act: Citizen lawsuits against polluters of the nation's waterways. Committee print, September, 1970.

13. Protecting America's estuaries: The Potomac. House Report 91–1761, December 16, 1970.

14. Public access to reservoirs to meet growing recreation demands. House Report 92–586, October 21, 1971.

15. Increasing protection for our waters, wetlands, and shorelines: The Corps of Engineers. House Report 92–1323, August 10, 1972.

16. Enforcement of the 1899 Refuse Act. House Report 92–1333, August 14, 1972.

17. Protecting America's estuaries: Puget Sound and the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. House Report 92–1401, September 18, 1972.