Ring Lardner Jr.: American Skeptic

Interview by Barry Strugatz and Pat McGilligan

At the age of twenty-six, Ring Lardner Jr. shared the 1942 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Woman of the Year. Five years later, he was cited for contempt of Congress for refusing to state whether he was a member of the Communist Party. He was then blacklisted and sent to prison for a year.

Lardner's screenwriting career spans more than five decades. The son of one of the country's leading sportswriters and humorists, he grew up around some of the greatest writers of the century. Lardner dropped out of Princeton, became a newspaper reporter, and then, at the request of David Selznick, went to Hollywood as a publicist but gravitated to screenwriting.

Passionately committed to left-wing politics, Lardner became active in the Communist Party. After World War II, he was called to Congress with nine other screenwriters, producers, and directors, and refused, on constitutional grounds, to reveal his political affiliations. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they appeared before the HUAC, signaling the beginning of the blacklist, when anyone with even vaguely leftist leanings was prevented from working in the entertainment industry. When the committee demanded an answer to the question "Are you now or have you been a member of the Communist Party?" Lardner gave the now famous reply: "I could answer it, but if I did, I would hate myself in the morning."

After serving a one-year sentence in federal prison for the offense of contempt of Congress, Lardner finished a novel he had begun there. The book, The Ecstasy of Owen Muir, was published in England first, then America (New York: Cameron and Kahn, 1954). After that, he survived the blacklist by writing television films that were shot in England and sold to American networks with pseudonymous credits. It would have been much easier for him to work in England, but the US State Department denied him a passport until a

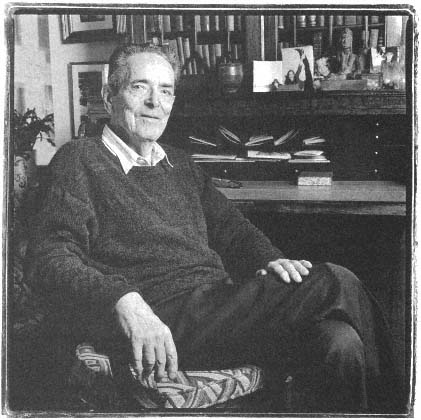

Ring Lardner Jr. in New York City, 1994.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

Supreme Court decision in 1958.[*] In 1962, thanks to the efforts of Otto Preminger, Lardner was once again employable in the motion picture business, and in 1970, he won his second Academy Award, forM&astric;A&astric;S&astric;H.

Lardner remains active, having recently completed a screen adaptation of Roger Kahn's book about the Brooklyn Dodgers, The Boys of Summer. Sur-

* The US Supreme Court ruled in favor of the artist Rockwell Kent, in the case of Kent v. Dulles, in 1958, breaking the State Department's stranglehold on passport rules by deciding "the right to travel can be removed only with due process under the Fifth Amendment." For many, international travel resumed. For others, "even after the Kent decision, the right to travel remained restricted" (David Caute, The Great Fear: The Anti-Communist Purge under Truman and Eisenhower [New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978]).

prisingly, he is not bitter. Despite having chronicled and suffered from the foolishness of the human race, Lardner has maintained a sense of dignity and equanimity.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Television credits include episodes of Sir Lancelot, Adventures of Robin Hood, and other series, under pseudonyms.

Plays include Foxy.

Books include The Ecstasy of Owen Muir, The Lardners: My Family Remembered, and All for Love.

Academy Award honors include Oscars for Best Screenplay for Woman of the Year (original) and M*A*S*H (adaptation).

Writers Guild honors include the award for Best-Written Comedy Adapted from Another Medium for M&astric;A&astric;S&astric;H. Lardner also received the Laurel Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1989. When the East Coast branch of the Guild instituted the Ian McLellan Hunter Memorial Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1993, Lardner was the first recipient.

When and why did you decide that you wanted to be a writer?

Well, there was always the possibility of writing in our household, particularly newspaper writing . . . my father always thought of himself as a newspaperman, even after he ceased much active newspaper work. The four of us boys published a family newspaper, which we all wrote. We all did various kinds of writing. I was the editor of the literary magazine at Andover.

I wasn't sure that I was going to be a writer even by the time I went to Princeton. I was still thinking about the possibility of either teaching history or studying law, both of which had some appeal to me. But by the end of that sophomore year, I left college, which ruled out anything that required an academic background, and like my two older brothers before me, I got a job on a newspaper in New York.

Those were very hard times for getting a job for most people. It was 1934, the depth of the Depression. It was definitely easier for us to get that kind of job than any other, partly on the basis of my father's name.

Did growing up around writers like Fitzgerald influence you?

Scott Fitzgerald certainly was an influence. I think I went to Princeton because he told me I should. I found both him and his wife quite glamorous figures . . .

We did know a lot of people who worked as writers. Dorothy Parker came at my father's invitation and stayed a week in our guest room because she said she had to be alone to write. And Charles MacArthur and Heywood Broun and Alexander Woolcott and Sinclair Lewis and a number of other writers.

How did you become interested in politics?

While I was at Andover, which was from 1928 to 1932, I became interested—not too heavily—in what was going on in the country. In 1931, I made a speech, impromptu, from the top of a bus en route from Boston to New York that had stopped somewhere for the passengers to go to the bathroom. Some-

thing moved me to get up and talk about Governor Roosevelt as a presidential possibility the following year. And during the convention, the year I graduated [1932], I sat up all night listening to the radio the night they stopped the movement to block Roosevelt.[*] But that fall, during the campaign, when I was a freshman at Princeton, I no longer supported Roosevelt. I had joined the Princeton Socialist Club and went around with a number of students to northern New Jersey, speaking for Norman Thomas, the Socialist candidate, who was also a distinguished Princeton alumnus, and who came back twice a year and preached in the Princeton chapel and then met in the evening with the Socialist Club members.

How did you go from Roosevelt to Norman Thomas?

I can't really say at this point. I must have read something that summer of '32 that converted me to socialism; I don't really know what it was. After I left Princeton, I spent about eight weeks in the Soviet Union and about a month in Germany, the month Hitler took over, after Hindenburg died. And the contrast was very impressive. I was quite taken with what was going on in Moscow.

When you were in Germany, how did you live?

I stayed with an architect's family outside Munich. A young man in the family there was a member of the Hitler Youth Corps, and we had a lot of discussions about that.

Was he pretty fanatical about the subject?

Yes, he was—on a more intellectual Nazi level: "We really have nothing against the Jews, except that if you look at certain professions, we find there are only two million Jews in Germany, but 60 percent of the lawyers and 41 percent of the doctors, etcetera, are Jews. That deprives Germans of jobs. But we have nothing against them personally. They actually got there because they worked harder than the Germans did."

But they would always make that distinction between Jews and Germans—as if they couldn't be the same.

Did you see any Nazi demonstrations?

Yes. Just before I got there, there had been the purge of the storm troopers when Hitler had flown to Munich and personally seen to the shooting of Ernst Röhm, the head of the brownshirts.

Then, while I was in Munich, he came again after Hindenburg died, and you saw an awful lot of men in uniform. They would be in the street, standing around with people watching this procession go by, which included a limousine with Hitler in the back. And there was this man sitting in the backseat

* An opposition coalition led by the followers of House Speaker John Nance Garner of Texas, former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, and the former presidential candidate Alfred Smith, blocked Franklin Delano Roosevelt from the two-thirds margin necessary for victory on the first three ballots at the 1932 Democratic National Convention. Then Roosevelt offered Garner the vice-presidential spot on the ticket, breaking the opposition and clinching the nomination on the fourth ballot.

with him that nobody else recognized, but I recognized as William Randolph Hearst. A couple of months later, Hearst came out with a front-page interview with Adolf Hitler.

Going Hollywood

You went from being a reporter to going to Hollywood. Tell me about that.

I went to work in January 1935 for the New York Daily Mirror, and I worked there until November. During the summer, I visited Sands Point, Long Island, several times, at the home of Herbert Bayard Swope, who had lived next door to us in Great Neck in the twenties and had been the editor of the New York World, wrote campaign speeches for Franklin Roosevelt, and was a man known for the parties he gave and the number of celebrities who hung around his place. His son, Herbert Swope Jr., and I had known each other as children and roomed together our second year at Princeton.

One weekend David Selznick was a guest, and I got to talking to him. He asked me if I was interested in working in Hollywood, and I said that I might be. I didn't know. He was starting a new company; he had just left MGM. And then I got a letter from him suggesting that I send him some stuff that I had written, and I sent him some of the material that had appeared in the humor magazine at Princeton, the Princeton Tiger, and some other things I don't remember, quite a bunch.

Anyway, in the fall came this offer to sign a seven-year contract, which was then standard in Hollywood. The only thing that wasn't standard about it was that it started at forty dollars a week, with options every six months.

I was making twenty-five dollars a week on the Mirror, so that was a distinct raise. It didn't say specifically what I was supposed to do; they could use me almost any way. But he had mentioned the publicity department or something like that, which was tied in. So I decided to sign the contract and flew out to Hollywood.

I went to work in the publicity department for his first publicity director in this new company, Selznick International, who was replaced pretty soon. Selznick had told him that he didn't want any publicity about himself personally; he just wanted publicity about the company. And this fellow, Joe Shea, took him literally. So Selznick fired him and hired a man named Russell Birdwell, to whom he told the same thing. But Birdwell didn't pay any attention and just put out as many stories as he could talking about this young genius, David Selznick.

What were your specific duties?

First I was on the set of the picture they were making, Little Lord Fauntleroy [1936], starring Freddie Bartholomew and Dolores Costello Barrymore. And I would just do interviews with actors and people around and whatever Birdwell assigned me to . . .

Then, after I had been there about a year, Selznick was preparing A Star is Born and had asked Budd Schulberg, who was a reader in the story department, and me to do some work on the script.[*] Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell were rewriting the script by William Wellman and Robert Carson; and Selznick felt we might get some ideas for a few scenes, and he had us tag along as writers . . .

Right around about that time, Selznick also gave me a screen test, which he had the right to do under my contract.

What was the story behind that? He thought you had possibilities?

Yes. George Cukor was assigned to do the screen test, but George passed it off to an assistant of his named Mortimer Offner, who took just a silent test, actually, and it was not very good. The only time Selznick ever commented on it, he said, "I think you are going to be a writer." And it was never seen again except that Budd Schulberg swiped it out of the vaults of Selznick; and one night at a party at his friend Maurice Rapf's house, where they had a projection room—Maurice's father was an MGM producer—they were showing some movies, and they put on this screen test of mine as a short subject. That was the only time it was ever seen.

Anyway, Budd and I started to work on A Star Is Born, and as a matter of fact, we came up with the ending used in the picture. It was the scene that took place at Grauman's Chinese Theater. Janet Gaynor was having her footprints placed in cement, and although she was a star under the name of Vicki Lester, she said, "This is Mrs. Norman Maine," in memory of her husband, played by Fredric March. The same ending was later used in the Judy Garland-James Mason version.

We did, as I say, some other scenes. Dorothy Parker said she thought we ought to receive credit on it. According to the Screen Writers Guild rules,[**] we weren't entitled to it, and Selznick wouldn't hear of it anyway. But at least we were, so to speak, graduated into being writers, and he gave us a project to work on with [the producer] Merian Cooper.

Cooper did King Kong [1933].

* Budd Schulberg, a novelist, memoirist, and screenwriter, wrote the story and script of On the Waterfront and A Face in the Crowd. His most famous novel is What Makes Sammy Run? a Hollywood roman a clef. Maurice Rapf's screen credits include The Bad Man of Brimstone, They Gave Him a Gun, Jennie, Call of the Canyon, Song of the South, and So Dear to My Heart. Rapf was blacklisted in the 1950s; Schulberg cooperated with the HUAC investigation. In 1939, Schulberg and Rapf had collaborated on Winter Carnival, about their Dartmouth alma mater, with another alumnus, Walter Wanger, acting as producer. Among the uncredited writers on the project was the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald.

** The Screen Writers Guild, founded in 1933, was the forerunner of today's Writers Guild. In 1954, when the guild merged with the Radio and Television Writers Guild, the new organization was called Writers Guild of America.

Yes. Then they did a picture called Nothing Sacred [1937], with Carole Lombard and Fredric March. Budd was sick at the time, but I was one of the writers assigned by Selznick to think of an ending. I seemed to be becoming an ending specialist. Selznick had had a quarrel with Ben Hecht, who had written the script, and Hecht left with an ending that Selznick didn't like. So, in typical Selznick fashion, he airmailed copies of the script to George S. Kaufman and Sidney Howard and Moss Hart and people all over the country, as well as to some who were in Hollywood, and he also assigned an MGM writer named George Oppenheimer and me. We wrote the ending that was used.

The following year, I or his secretary, Silvia Schulman, revealed to Selznick that she and I were going to get married, and he thought this was a very poor idea. He had just gone through a big struggle with Budd Schulberg about his marriage. His objection in both cases was that these were mixed marriages, that Budd was marrying a Gentile girl, and I was marrying a Jewish girl. He told Budd that he ought to remember that he had producer's blood in him. (Laughs. )

About the same time, Selznick wanted to sign Budd and me to new contracts. We would each get a raise from $75 to $100 a week. We went through several sessions with his business manager, Daniel O'Shea, who was arguing about why we should be content with $100 rather than $125, which I think we were asking for. During the course of one of these discussions, the interoffice phone sounded, and it was Selznick's voice saying, "What about Sidney Howard on Gone with the Wind? " and O'Shea said, "He won't work for $2,000 a week; he wants $2,500."

And Selznick said, "For Christ's sake, give it to him."

And O'Shea said, "Okay, David." Then he turned to us and said, "Now, boys, you've got to realize—"

Anyway, Silvia advised us to hold out. And we did, and we got the 125 bucks.

A couple of months after we were married, a contract option came up and Selznick let it lapse and I was still there on salary. But whatever projects we were working on seemed pretty ephemeral, and a writer named Jerry Wald, who was working at Warner Brothers, suggested that I go to work there. And I was offered a job in the B department under Bryan Foy, who made thirty pictures a year with budgets under $250,000.

Was that a step down—going from Selznick?

Well, it was a step down in a way, except that at least I thought I could get something made. With Selznick, it wasn't practical for writers at our level: he was only making one or two pictures a year. In any event, I left Selznick in the early part of 1937 and went to Warner Brothers, where I remained for about a year, I guess, without anything really coming out the way I wanted it to.

I worked at Warner Brothers for about a year, and then during the following two years, I worked on a number of projects. I think it was in 1938 that Ian

McLellan Hunter and I worked together for the first time on a series of movies that were made with Jean Hersholt playing a character called Dr. Christian, which he had played on the radio.[*] We did this with a director named Bernard Vorhaus, who had directed in England and Switzerland, though he was an American by birth. He had come to Hollywood to work for Republic Pictures. I think we worked for him first on a Republic Pictures venture based on a book by Irving Stone called False Witness [New York: Book League of America, 1940], on which I think we received some kind of screen credit [on the film, which was titled Arkansas Judge ].

Then an independent company called Stevens-Lang undertook to produce these Dr. Christian pictures, and we worked on a script they had called Meet Dr. Christian; we wrote the next picture entirely, The Courageous Dr. Christian. Around this time, I also collaborated with an Austrian writer on an original screen story, which we sold to MGM for a very small sum of money. But we were both interested in getting jobs, so we agreed to sell our story for $5,000, or something like that, provided that we could each work on the picture for $250 a week for a minimum of six weeks or so.

After we made the sale, they paid us off with six weeks' salary—maybe it was only four weeks' salary, I don't know—and gave the story to somebody else to do. I was told by someone at the studio that William Fadiman, who was the story editor at the studio, had said that I would not be allowed to work at MGM; that they never had any intention of letting me work there. This was because by that time I had gotten involved in the reorganization of the Screen Writers Guild, which was fighting the company union called the Screen Playwrights. Also, at Warner Brothers, I had, in collaboration with John Huston, raised money for medical aid to Spain. We would corner people like James Cagney and Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart at lunch, and get them to contribute to sending ambulances to Spain. John, I must say, was much more persuasive and influential in this endeavor than I was. My job was mainly to goad him to do the spiel.

Fadiman, who was Clifton Fadiman's brother, had apparently gotten wind of these activities and took a position against me. As a matter of fact, that was one of the reasons why, when Michael Kanin and I did the script for Woman of the Year, we contrived with Kate Hepburn for her to take it to Metro with no names on the script, so Louis B. Mayer would agree to her terms before anybody at MGM realized who had written it.

* Ian McLellan Hunter had a distinguished career. He collaborated with his friend Ring Lardner Jr. In addition to working together on the Dr. Christian series for film and The Adventures of Robin Hood for television, they also teamed up for the 1964 Broadway musical Foxy, a Yukonset adaptation of Ben Johnson's Volpone. Hunter won an Oscar for Best Story for Roman Holiday (1953), and shared a nomination for Best Screenplay with John Dighton. His other screenplay credits include Second Chorus, Mr. District Attorney, A Woman of Distinction, and, after years of blacklisting and television work under pseudonyms, A Dream of Kings (1969).

Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in George Stevens's film Woman of the Year.

Woman of the Year

How did Woman of the Year start?

Well, it started with Garson Kanin, really. A friend of mine, Paul Jarrico, had written Tom, Dick and Harry [1941], which Garson was shooting. And I visited him on the set one day. Garson said he had this idea for Hepburn, who was still very much in the shadow of the exhibitor's denunciation.[*] But the play The Philadelphia Story was a big hit and brought her back to Metro.

But Garson knew she needed something after the film version of The Philadelphia Story [1940]. So he came up with a sort of Dorothy Thompson character. Dorothy Thompson was the only woman columnist at the time. I said I thought it might work, and Garson suggested that I get together with his brother Mike and see if we could work out a story. He had never written anything and was preparing to go into the army because he had been drafted . . .

* According to Me, by Katharine Hepburn (New York: Random, 1991): "During this period [post-Sylvia Scarlett ], my career had taken a real nosedive. It was then that the 'box-office poison' label began to appear. The independent theatre owners were trying to get rid of Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford and me. It seems that they were forced to take our pictures if they got certain ones which they really wanted. I felt sorry for them. I had made a string of very dull movies."

How did you work with Kanin or any collaborator?

Generally, by talking out a whole scene or sequence in considerable detail, so that we were substantially agreed on it, and very often two scenes, so that one of us could sit down and write a first version of each. And then we would switch them, and the other one would rewrite the scene. Each would rewrite the other's work, and then we would go at it again together. The process of setting it down for the first time has always required one person being at the typewriter by himself. The collaboration takes place in the plotting and then in the rewriting.

So we started to work out the story, and finally, I wrote it in the form of a kind of novella in the first person and in the past tense. It was told by this newspaperman, a sportswriter, the part [Spencer] Tracy played. I think it was called "The Thing about Women." It was that version that we sent to Kate. Garson probably sent it to her; he was the one who knew her personally. And she responded very well to it. And then we got up this plan of her taking it herself to Louis B. Mayer and talking to him about it.

Was Hepburn involved in developing the story?

Not in the story itself, because we wrote it as a piece of fiction. We wrote it that way, incidentally, after having talked it out as a screenplay, thinking it would work better and be more readable. I had found out that the great obstacle in getting attention paid to a piece of writing in the movies is that people have to read it—and most screenplays don't read very well, and treatments don't either.

Kate had nothing to do with that part of it. But after she read it, she figured out the terms: $211,000: $100,000 for her, $100,000 for us, $10,000 for her agent, and $1,000 for her expenses to come from Hartford. And that $100,000 for us included a screenplay and all the revisions that would have to be done on it, although no scene had been written yet.

Once MGM went for the deal and we started to work on the script, we had a number of consultations with Kate, including a few sessions that took place in Michael Kanin's house, where she stayed around for hours, late at night, while we were talking and sometimes actually writing some of the stuff, and she took quite an active part in the sessions.

Then what?

Well, after we finished the first draft of the screenplay, we got more actively involved with the people who were going to do it—with [the producer] Joe Mankiewicz and George Stevens, the director—and we had many consultations with them, resulting in revisions. Once the picture started shooting, there was relatively little to be done. We were free to be on the set whenever we wanted to. We both had signed contracts with MGM and were working on another script, so it was convenient to drop in on the set almost every day, and sometimes that would result in a conference with George Stevens about something.

Did you get along well with him?

Yes, through the shooting of the picture. But then, when we thought it was all through—it had been cut and was getting ready for a preview when Mike and I and our wives went to New York on vacation, [and] when we got back—we found out that the studio executives had decided they didn't like the ending and decided to shoot a new ending and had assigned a writer, John Lee Mahin, who had been president of this company union of screenplay writers that we had fought against—but who was a pretty good writer[*]—to write this revision, and they had a version of it by the time we came back.

Well, we objected strenuously. We didn't like the ending. The whole theory behind it seemed to be that there had to be some comeuppance for the female character.

Why did they think she needed a comeuppance?

The executives at MGM, including Joe Mankiewicz, supported by George Stevens, felt that the woman character, having been so strong throughout, should be somehow subjugated and tamed, in effect. They felt it was too feminist, and they devised this ending that involved Hepburn trying to fix breakfast in an apartment that Tracy had taken by himself. It was based on some comedy routines that George Stevens had done back in his silent picture days when he used to do Harry Langdon comedies. Even on paper, it was conceived of quite broadly.

And so we objected to it in theory and then objected specifically to a number of lines, etcetera. And George and Joe did agree that some of our points were well taken, and we were allowed to revise Mahin's work within the context of the scene as planned, not to try to go back to our old ending, which they didn't like, or to devise something different.

So we did modify it somewhat before it was shot. But then Stevens went the other way in the shooting, and the action was quite broad, and we were disappointed in the result.

What kind of business did the film do when it was released?

It did very good business. I believe it was the first picture to run three weeks at the Radio City Music Hall.

And it won the Academy Award in what areas? Do you remember?

I think the only Academy Award was for us: for the Best Original Screenplay.

How old were you?

Twenty-six.

Were you at the ceremony?

* John Lee Mahin, a favorite writer of both Clark Gable and Victor Fleming at MGM, where he spent most of his career, is profiled in the first Backstory.

No, by that time I'd gone to work for the Army as a civilian employee writing training films. So I just heard about it. I was working at the cooks and bakers school at Camp Lee, Virginia, writing a picture called Rations in the Combat Zone.

What did the success of Woman of the Year mean to you—to your career?

Oh, it meant a great deal. It meant, in the first place, that MGM, after we had finished the script, offered us—and we signed—a contract at a lot more money than either of us had been making. Really, from then until 1947, 1 never had any trouble getting work.

The Communist Party

When did you join the party?

In 1936.

You knew Budd Schulberg in Russia?

I met him first there. He and Maurice Rapf were students there; they were both students at this Institute at the University of Moscow. We didn't know each other very well there, but we spoke.

He was very political back then.

Very. As a matter of fact, Budd really recruited me into the Communist Party. We were working together on A Star Is Born or had started on that thing for Merian Cooper; I know we were collaborating on something. I had written a letter on Selznick International stationery to Time magazine, which they published in connection with something they had said about the StalinTrotsky rivalry, and I was correcting a point of fact. Somebody apparently in the Communist unit to which Budd belonged said, "Hey, isn't this the guy you are working with? And if he is writing this kind of pro-Stalinist letter, why haven't you recruited him?" So Budd went to work on me.

How did he do that?

It wasn't very hard.

The people who were in the Communist Party, were they a social group?

Yes. Over the next couple of years, not only were most of my friends writers but they were mostly Communists. Both tendencies were, I think, unfortunate: it's not good always to be with like-minded people.

Schulberg and his wife were romantic figures in a way, weren't they?

Yes, she was a very glamorous, very beautiful woman, and Budd, who was not at all prepossessing in appearance or speech—he stuttered; it was more pronounced then than it is now—was nevertheless regarded by everyone as an extremely devoted and idealistic fellow, as well as a very talented individual. So they were definitely a sort of role model.

What was the general political climate in Hollywood?

People were becoming quite political about the Spanish Civil War, which broke out in the middle of that year, and about what was going on in Germany.

The most popular political organization in Hollywood at that time was the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, which Donald Ogden Stewart was chairman of, but most of the work was done by Herbert Biberman and Beatrice Buchman, Sidney Buchman's wife.[*]

Also, toward the end of 1936, the Screen Writers Guild, which had been effectively smashed a couple of years before, began to reorganize because of the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and we were working toward a Labor Board election, which took place in the spring of 1937. There was also a strike going on, in '36 through '37, of the various crafts—the non-IATSE-AFL crafts,! carpenters and painters—supported by the office workers and readers; and the Screen Actors Guild [SAG] was heading toward its first contract and, as an AFL union, was in a position where they had to decide whether to support the IATSE[**] or this other AFL group. It was a very close battle, and there was a big political fight in SAG. At one point, they actually passed a straw vote to support the strikers and respect picket lines, but when it came to an actual vote, they didn't.

What did it mean to be an active member of the Party? What do you think you accomplished by being a member? What do you think the Party accomplished?

What it meant to be an active member was mostly spending a lot of time at meetings of various sorts. The year after I joined the Party, I was preempted by the board of the Screen Writers Guild to become a member of the board representing the young writers, and then in an election, I was elected to the board. I had meetings of the guild board once a week and usually a committee meeting another evening of the week, and there was a regular Party branch meeting about once a week. And very often a writers' faction—these were writers who were members of the Party, as well as a few who, for various reasons, were not but were very close to the Party—would meet and would discuss policy in the guild. With one thing and another, I found I was going to meetings five or six nights a week. And Silvia, who joined some months after we were married, was going to a good many of those, too. And there were other types of meetings as well.

We did play a part, I think, in most everything that was going on in the Hollywood scene. Organizations such as the Motion Picture Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, and the League of

* Herbert Biberman was also one of the Hollywood Ten. Besides Ring Lardner Jr., the others, several of whom are mentioned in this interview, were Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo.

** The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (and Moving Picture Machine Operators), or IATSE, is the union representing every branch of motion picture production in the United States and Canada, and is affiliated with the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organization (AFL-CIO).

American Writers would not really have functioned anywhere near to the extent that they did without the very active participation of Communists in their forefront. Nor, I think, would the unions that were being formed or reformed at that time—the guilds of actors, writers, and directors, etcetera, and the emerging office workers union, etcetera—have gotten as strong as fast as they did without the extra work that the Communists put into organizing and recruiting people for them.

The nature of the work we did changed twice during that period: Once in the fall of 1939, with the outbreak of the war in Europe and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Russian war against Finland, etcetera, when there was a very sharp division for a while between Communists and liberals—most of the latter being supporters of the British and French in the war and most of us remaining pretty skeptical about what the Allies were up to in the war. And then, of course, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and when Pearl Harbor was attacked, there was another big shift and with much more unity on the liberal and left side of things.

Why were you skeptical of the Allies in the beginning?

The basic skepticism was what I still think is a well-founded fear: That the people who were in charge of those governments—Neville Chamberlain in England and [Edouard] Daladier in France—were likely to, if they got a chance, make some kind of deal with Hitler to turn the war against the Soviet Union, which was a very popular idea in British and French circles.

What did you think of the nonaggression pact?

We thought it was just that: a nonaggression pact. And we justified it on the ground that Stalin and the Soviet Union generally had kept advocating collective security in Czechoslovakia and Poland, etcetera; that they had finally despaired of ever getting an agreement to oppose fascism collectively; and [that it was done] in self-defense because they feared German aggression backed by the Western powers: they had signed the pact to give them time.

But gradually, it emerged that there was more to it than that: there was the active splitting up of Poland; there were certain economic exchanges going on that were distasteful. But still, as we saw it—as I saw it, anyway, and as I think most of my comrades did, too—this was understandable and could be justified.

How did you see your politics as they related to your writing?

It was pretty difficult to find much relationship between them, except to the extent that when I was able—after Woman of the Year —to make some selection in what I was doing, I tried to get assignments that had some potential for progressive content.

We had what was called a clinic within the Communist Party, where writers used to meet and discuss each other's problems with scripts and sometimes with other kinds of writing: books, etcetera. That was, I think, helpful to many individuals in just working out certain technical story problems and things in

conjunction with their colleagues. But I can't say that it had much of a broad effect on the content of what was done in the movies.

Did the studios or the Party try to influence the political content of scripts?

When they finally came before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, the heads of the studios maintained that there was never any real question about the content of pictures because they retained control of content. And largely, this was true; they did. What things a few writers might have been able to sell them or slip into a script were of minor consequence. Basically, it was the studio heads who had charge of the content of the films, and there was nothing we could do about it.

Wasn 't there a story about a script you had written for [the producer Sam] Goldwyn called "Earth and High Heaven "?

Yes. That was toward the end of the war, in 1945,I think. He hired me to work on what was to be the first picture on anti-Semitism. It was an adaptation of a novel about anti-Semitism in Montreal by a writer named Gwethalyn Graham [Earth and High Heaven (New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1944)]. Goldwyn's wife, Frances, a former showgirl who was non-Jewish, had persuaded him that he should make the picture. He was extremely nervous about it.

I had a few conferences with him, and we more or less discussed what was to be done with this script. And then he went away on some wartime mission—he went to Russia, actually—that had to do with the picture North Star [1943], which Lillian Hellman had written. When he came back, I had written the first draft of the screenplay. After he read it, he called me in and started a conference by saying, "Lardner, you've defrauded and betrayed me."

I said, "Well, I can see that you don't like the script. What do you mean about this 'defrauding and betraying'?"

He said, "Well, I said 'defrauded' because we agreed on a treatment, and you wrote a treatment before I left; but this script is not that at all."

I said, "There were some changes. Naturally, you make changes as you write the screenplay." So finally I said, "How did I betray you?"

He said, "One of the reasons I hired you for this particular script was that you are a Gentile. But you betrayed me by writing like a Jew."

And I couldn't answer that.

I did relate this conversation that night to my friend Gordon Kahn,[*] who

* Born in Hungary, Gordon Kahn was one of the original Hollywood Nineteen, unfriendly witnesses summoned to Washington, D.C., in October 1947 to testify as to their political activities in Hollywood. When he was blacklisted, Kahn wrote one of the first accounts of the blacklist, Hollywood on Trial, and throughout the 1950s, he wrote numerous newspaper and magazine articles under pseudonyms. Kahn had many script credits in Hollywood including The Sheik Steps Out, Navy Blues, I Stand Accused, Tenth Avenue Kid, The Road Back, Ex-Champ, A Yank on the Burma Road, Tarzan's New York Adventure, Northwest Rangers, Song of Nevada, Two o'Clock Courage, Her Kind of Man, Whiplash, Ruthless, and Streets of San Francisco.

said, "What did you do—write it from the right-hand side to the left-hand side of the page?"

But Goldwyn then hired six or seven other writers in succession over the next three years to rewrite this script, and he was dissatisfied with it each time. Finally, Darryl Zanuck came out with Gentleman's Agreement [1947], and Goldwyn said, "He stole my idea." But he never made "Earth and High Heaven."

Fritz Lang and Cloak and Dagger

Tell me a little bit about Cloak and Dagger and working with Fritz Lang.

I came on the project after there was already a script written by Boris Ingster and John Larkin. Fritz didn't like the script they had at all, so my job was to do a complete rewrite as fast as possible. Then, just on the verge of shooting, Albert Maltz was brought in to rewrite behind me. They were behind schedule, to put it mildly. Albert and I were working at the same time, usually not on the same scenes.

What was it like working with Lang? Was he personable? Did he involve himself very much in the development of the script?

Of course, I knew his reputation and his films, so I welcomed the opportunity to work with him. I remember we worked mostly at his house. He took the story very seriously. He did not do any actual writing—he just contributed ideas—but he was very helpful. He was very respectful of writers.

The name of John Wexley [who collaborated with Bertolt Brecht and Lang on Lang's film Hangmen Also Die ] came up once somehow. Fritz said, "He is a dishonest man." I, who knew John and wasn't too fond of him, nevertheless felt this was going too far. I said, "What do you mean he's a dishonest man?" Fritz said, "He's thoroughly dishonest. When we worked on the script for Hangmen Also Die, I told him the script had to be shortened by about twenty pages, and he came back with a script that was twenty pages shorter; but I found that only ten pages in actual length had been cut out, and the rest was by his instructing his secretary to put more lines on a page!" This was a fairly common writer's offense and not exactly a crime. But Fritz was very moral about it.

The monocle which Fritz wore was very distinctive. The only other person I knew in Hollywood who wore a monocle was Gordon Kahn. Gordon was small in stature, and he liked to say that without the monocle, he was just "that little Jew writer," but with it he was "that little Jew writer with a monocle," and that made him more memorable. The monocle probably was a real thing that Fritz needed, but I imagine that he wore it intentionally. After all, many people who have that one-eye problem wear glasses with plain glass in the other eye, because it's not as conspicuous as a monocle. But like Gordon, in his way Fritz liked the impression that the monocle gave.

I liked Fritz. He was a hell of a good talker. He said funny things, mostly of a dry wit and mostly detrimental about other people. I think we had a good and productive time together, so much so that I remember I had discussions with him about at least one other project which did not—or at least my involvement did not—come to fruition.

Did he talk about politics at all?

I think he was generally of the left and sort of against the establishment anywhere and everywhere. I don't know if he talked very much about American politics.

The film I think turned out not only far-fetched but bland in many respects.

Though I haven't seen the picture in nearly fifty years, my recollection is that it was a moderately satisfactory movie. I remember when I came to work on the script, I met [Gary] Cooper. He said, "Look I want you to understand one thing. I'm supposed to be playing an atomic physicist in this picture, and the only way I can get away with playing an atomic physicist is if you keep the lines very simple . . . "

I don't know how it affected things, but I remember also that Fritz didn't get along with [the producer] Milton Sperling.[*] At a few conferences, they behaved quite nastily to each other. There seemed to be an almost personal dislike between them. I remember shooting started on a Monday. We had a final conference on the Saturday before, at the end of which Milton, trying to make peace with everybody, said, "Now, we're going to start shooting on Monday. We've had a lot of disagreements. There's been a lot of harsh words going back and forth, but all that's behind us now, and let's forget it. And Fritz," Milton added, very conciliatory, "I will see you on the set Monday morning." And Fritz said, "That will not be necessary."

The Hollywood Ten

When the war ended, did you detect a change in the political atmosphere—the beginning of the cold war, etcetera?

Yes, quite rapidly. I think it probably came quicker in Hollywood than in most other places, because during the last six months of that war, most of the same group that had been involved in that strike back in the late thirties, under the leadership of a man named Herbert Sorrell, started a strike against the studios. And it was the position of the Communist Party during the war that there

* Milton Sperling had a fifty-year career as a screenwriter and producer, highlighted by an Oscar nomination for his script for The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell (1955). He was also Harry Warner's son-in-law. His life story is sketched in the book Hollywood Be Thy Name (Roeklin, Calif.: Prima, 1994), written by his daughter Cass Warner Spelling and Cork Millner, with Jack Warner Jr.

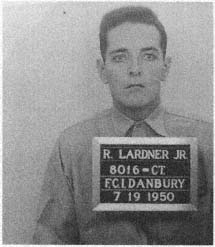

Ring Lardner Jr. jailed as one of the

Hollywood Ten in 1950.

(Prison photograph.)

should be no strikes and no support for strikes until the war was over. So we did not actively help. There was some money raised, because we were basically sympathetic with what was going on, but we thought they had called the strike prematurely.

And when the war ended in the summer of 1945, the strike was still going on, and that condition persisted for six months after that. As I recall, it was a long, drawn-out, and quite violent struggle, with a lot of violence taking place on picket lines. Many of us marched on those picket lines in '45 and '46. That strike divided Hollywood very much into a sort of liberal-left camp that supported the strike in varying degrees and the conservative element in the Screen Actors Guild which, by the time it was over, I think included a new president, Ronald Reagan.

At the same time, there was an organization called the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions, or HICCASP. The New York office was called NICCASP; in Hollywood, it was HICCASP. The members were very enthusiastic supporters of Roosevelt during his fourth election campaign, and many supported what Henry Wallace stood for subsequently. But there did arise a split between those who were more inclined toward Harry Truman's policies and those of us who thought Henry Wallace was the man who should run in 1948.

In the 1946 congressional elections, there were some very keenly contested races in California with quite a clear choice between liberals and conserv-

atives, including Richard Nixon, who was running for his first term in Congress.

On the national scene, we knew that there were big industrial conflicts going on. The United Electrical Workers Union and other unions that had a somewhat left orientation were trying to carry on strikes, and they were being opposed by the hierarchy in the AFL. I guess the AFL and the CIO were still separate at that time. This was the time when the so-called Truman Doctrine in regard to Greece and Turkey was promulgated, and when Winston Churchill made his Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, Missouri, with President Truman seated alongside him. This was the time when we all seemed to be going in the wrong direction.

When were you served with a subpoena? Do you remember that moment?

It was in September, I think, of 1947. I remember it particularly because we had just bought a new house. I had been divorced and remarried to [the actress] Frances [Chaney], my present wife, who was the widow of my brother David, who was killed as a correspondent for the New Yorker in World War II. We were married in 1946, and in the summer of 1947, we bought a house in Santa Monica with a tennis court—generally quite a nice place—and we were in escrow with it when subpoenas arrived. We had been aware of the possibility of this threat; even a year before, there had been talk of HUAC visiting Hollywood. From our honeymoon up in northern California, we had talked to somebody on the phone—I think it was my friend Hugo Butler—who had said it was best to stay out of town for a couple more weeks, because there were supposed to be subpoenas coming around. Well, it didn't happen then. But it had been very much in the air for a whole year.

Dalton Trumbo and I had a couple of times discussed what we would do if it came up. We decided that it was not a good idea to deny membership in the Communist Party, although some of our colleagues had done that before the California State Un-American Activities Committee. We just felt that there were too many stool pigeons and various other ways to find out, and you could get yourself in a much worse situation for perjury; it would be very hard to organize any sympathy around that. On the other hand, we thought it would be a bad idea to answer yes to the question, because the studios would probably use it against us, and also because it made it less feasible to refuse to answer further questions about other people.

You anticipated that they would proceed along those lines?

Yes. We therefore felt the most sensible policy was just not to answer questions and to challenge the right of the committee to ask any questions at all. The two of us had agreed that was the position we thought best to take.

It was only after it became known that there were nineteen of us who had received subpoenas [and were] known as unfriendly witnesses—as opposed to people who had received subpoenas who, we believed, were going to be cooperative witnesses—that we got together at meetings in Hollywood, all nineteen

of us, with the exception of Bertolt Brecht, who was then in a considerably different position. He was an enemy alien all during the war; the rest of us were citizens.

We met with some lawyers, and Trumbo and I brought up this idea of not answering any questions. There were problems with that position. There were several people who wanted to say yes, they were Communists; they felt it was time to raise the face of the Party. But we raised the point—and the lawyers agreed with us—that it would then be very difficult to take a position against naming practically everybody they knew.

We discussed the Fifth Amendment, and there was some dispute as to whether that would really work. The Smith Act, under which the Communist Party leaders were later convicted, had not been invoked against them at that time; it wasn't until the next year that they were arrested. So we would be saying, "It's a crime to be a Communist and therefore I plead self-incrimmation." And the committee members could say, "What do you mean, a crime? It's a perfectly legal Party." But beyond that, we thought that that position would not do anything to challenge the right of the committee to function.

In other words, it was a freedom of speech issue?

Yes. We were saying: "Under the First Amendment, there is freedom of speech and freedom of the press—and that includes the movie business. Therefore, Congress cannot legislate in this field—and Congress has no right to investigate where it cannot legislate."

What about the issue of political affiliation? Did that come under the First Amendment also?

Yes, that it was our business what political party we belonged to or believed in. And Alvah Bessie at that time pointed out to the committee that Dwight Eisenhower was then refusing to say whether he was a Democrat or a Republican—and we should have the same rights as he did.

So gradually the policy of not answering questions and of challenging the committee was agreed upon. More or less, we all agreed that we were going to do that, although we didn't want to seem to be doing it by agreement. Our lawyers additionally advised us that it was a good idea to say we were answering the question, but in our own way, while never actually answering it.

And we went along with this last tactic, which actually turned out to be a bad idea and just made us seem to be more evasive than we were, and it didn't accomplish anything in the end.

Could you describe what it was like testifying? What was going through your head?

I was somewhat frightened, I guess, of the idea of appearing before this committee. Incidentally, I didn't know definitely that I was going to appear. They had given ten people out of the nineteen definite dates on which to appear; the other nine of us were told we didn't even have to come to Washington; we were told that we could wait until we were given a definite date.

But we decided as a matter of policy that we should all go together when the hearing began. After a week of friendly witnesses' testimony, they went on to some of the unfriendly witnesses, and I still had no idea whether I would be called or not.

My wife and I had been going to the hearings every day. Finally, one day, I think it was on a Thursday during the second week of the hearings, we decided we didn't have to be there that morning. We were listening to the proceedings over the radio in our hotel room when suddenly [HUAC Chairman J. Pamell] Thomas or [Robert] Stripling, the counsel for the committee, called out my name to come to the stand, and Robert Kenny, who was one of the lawyers representing us, said, "He is not here." And Thomas said, "What do you mean he is not here? He has been sitting right down there day after day."

It seems that this was really occasioned by the fact that a picture of Frances and me sitting there had appeared on the front page of the newspaper PM the day before, and it had also appeared in a Washington paper. It was the fact that we were getting newspaper attention that sort of called the committee's attention to us, and I was therefore called out of turn. As a matter of fact, one of the people who was given a definite date—Waldo Salt, I think it was[*]—was not called, because they called off the hearing that day after I appeared, followed by Lester Cole and Bertoit Brecht, who was the last witness.

As I say, it was on a Thursday morning that we heard about it on the radio at the hotel. So I hastily got dressed and went down to the Senate Caucus Room where the hearings were being held, and met with our lawyers. We had a practice then, just before anybody was about to testify, for the prospective witness and the lawyers to take a walk in the outside gardens surrounding the hotel where we were staying, on the theory that there were not apt to be microphones there, and there would then be a discussion as to what might come up on the witness stand. I had such a discussion, but that afternoon they didn't call me. It was the next morning, Friday, that I was called.

I had no great confidence in my ability to be articulate before this committee or to make any great points at such a hearing. The experience of my colleagues who had preceded me—the way they were jumped on and shut up—made me less confident.

I just couldn't see any real good coming out of it and determined that I would try to make a couple of points about why I wasn't answering these questions; that was about the maximum good you could accomplish—namely, to get in a phrase or two. And that's what I tried to do.

* Waldo Salt, another one of the original Hollywood Nineteen was subsequently blacklisted, but he charged back, after the 1950s, to write such memorable and Oscar-winning films as Midnight Cowboy and Coming Home.

Prison and the Blacklist

Jumping ahead to after your sentence. What was your prison experience like? Were you scared?

Yes, that was really a considerable unknown, both as to what it would actually be like in prison and what it would be like with our particular offense. I faced that with a good deal of uncertainty and pessimism, because I didn't think it was going to go well.

It turned out, on the whole, not to be nearly as bad as I anticipated. The first three weeks we spent in the local—which is also the federal—jail in Washington in fairly confined circumstances. We were each put in with a prisoner there on another charge. Because we were just there temporarily, we were not given jobs or anything. So we just got out once a day into a very restricted yard, where you couldn't do anything but walk around in a circle. So that was quite confining. We then were sent to various institutions in different parts of the country.

Lester Cole and I were both sent to Danbury, where my mother, who was only about thirteen miles away, was able to visit once a week.

Were you put in the same cell?

No. In Danbury, every new inmate went through an orientation course, which involved living in a segregated part of the prison in a kind of dormitory and spending a few days learning about prison life and discipline and so on. Then we were released into the general population and assigned jobs according to whether we were classified as maximum security or moderate security or light security. Those who were light security were allowed to have jobs working outside the prison walls.

There was a farm in Danbury where they grew vegetables and things, and raised chickens. For some reason, I never figured out why, Lester Cole was granted this light or minimum security job, and I was classified as moderate security and could only have a job inside the walls. I was assigned to the Office of Classification and Parole to work on a typewriter from Dictaphone records that had been dictated by the officers at classification and parole. They were histories of each inmate as he came in and recommendations to the parole board.

When did you first realize you were blacklisted?

We returned from the hearings in Washington not sure of what was going to happen. We thought we had a pretty good chance to win the case, based on the court decisions so far, and we thought if we won the case, the studios would not take any action, would not get enough support to take any blacklisting action.

However, there was a meeting called the very next month in New York: The heads of companies in New York met and passed a resolution that ten of us would not work—and anyone else who took the same position couldn't

work—until we had been cleared by the committee, and that they would not knowingly hire a Communist or anyone who refused to answer questions of a congressional committee. So that was then put into effect in varying degrees. Only five of the ten of us were actually working at studios then.

Where were you?

I was under contract at 20th Century-Fox. I was in kind of a special situation because after I came back from the hearing. Otto Preminger asked if I would work on an adaptation of a book he had bought, and we started working on it. So they were giving me a new assignment after the hearing.

This later became an issue in a civil case when a jury decided that they had waived their right to fire me by giving me a new assignment. But a judge threw that out, and at a second trial, we settled out of court for a relatively minor amount of money. Anyway, Darryl Zanuck made a public statement that he wasn't going to fire anybody unless he was specifically urged to do so by his board of directors. But the 20th Century-Fox board got together and obliged him. I was the only person at the studio . . .

How did they let you know?

I was in Otto's office—we were talking about the story—when a message came that Zanuck wanted to see me. And Otto said, "Not both of us?" (laughs ), and the message was "No, just Lardner."

And then, when I went to Zanuck's office, I was shunted off and did not get to Zanuck himself but to his assistant. Lew Schreiber, who told me that my contract was terminated and I was supposed to leave the premises.

I told this to Otto. He was very distressed but couldn't think of anything to do about it. I met with a couple of people—Philip Dunne and George Seaton, a writer-director—both of whom said they were going to walk out with me. But I told them I didn't think that would be a very good gesture; if they could get a substantial number of writers to do it, it would be better. They tried, but they couldn't get anybody else, and they then agreed that it wouldn't amount to much. So I left 20th Century-Fox.

When you learned that people like Schulberg were cooperating with the blacklisters, were you hurt, disappointed, or did you see it coming?

There was some surprise and some disappointment. I heard about that when I was still in Danbury. It was a couple of weeks before we were to be released, and I had achieved a single cell, where I could do some writing. And a fellow inmate came to the door and said, "Hey, they're talking about you on the radio."

I went into the common room, and the radio said there were these new hearings going on, and that a writer named Richard Collins had named me. He was one of the group of young people in the Communist Party that I had run into when I had been recruited, and I heard that he had been disaffected; so I wasn't too surprised by that.

But then during the rest of that year, 1951, there were more hearings in Washington, and later in the fall, in Los Angeles, a number of people had testified. Some of them I was quite surprised by. But, in particular, I knew that Budd had had nothing to do with the Party since 1940–41; and I had once talked to him, and he felt very strongly about some Russian writers that he had met when we were both in Moscow in 1934, who had since been purged. But, still, that Budd volunteered, really, to appear before the committee because someone had named him—he wasn't subpoenaed and he wasn't working in Hollywood at the time and there was no particular reason why he had to clear himself—surprised me.

But others were more understandable. Some of them did it under quite strong pressure and didn't—like Budd, [the director Elia] Kazan, and some others—have some other kinds of work that they could do. Some of them were extremely dependent on Hollywood to support themselves.

What was the impact of the blacklist?

Well, the impact was to create intimidation in the motion picture business and in the emerging television business. It affected the content of pictures to some extent, because people avoided subjects they thought were controversial. The studios started making anti-communist pictures, which the committee more or less specifically asked for, and although they didn't do very well, there was a tendency to stay away from material that might be controversial. There was, I think, an increased kind of escapism in pictures. Certainly, the impact was strongest on the three hundred or more who were blacklisted. But it also threatened people who sort of got nervous about being revealed as entertaining dangerous thoughts.

Do you think this was an attack on freedom of speech?

Yes. I think it certainly had a limiting effect on freedom of expression in Hollywood.

In the end, of course, it didn't last, and it didn't achieve very much. It really basically died of ridicule, partly because of the number of issues that came up in relation to Academy Awards and partly as a result of a campaign largely led by Dalton Trumbo to make fun of the whole process and its contradictions. So by the time it began to break up in the sixties, most people looked back on it as a bad idea or as a kind of laughable one. By the seventies, it even became more or less a kind of honor to have been blacklisted.

People have characterized your actions with the Hollywood Ten during the blacklist as heroic.

I would say that we did the only thing that we could do under the circumstances, except behave like complete shits, and that doesn't amount to heroism. I think there has been some difference of opinion about this. But, as I recall it—my version of it, anyway—we figured out the most sensible thing to do, we thought we had a good chance of winning, and we played it that way.

Uncredited Work

Let me ask you about a couple of directors you worked with—in each case, without screen credit. What were they like? Were they very literate? Starting with William Wellman . . .

Wellman was reasonably literate, but you could never class him as an intellectual. He knew his craft very well and resisted Seiznick's attempts to control him. He could be funny and entertaining, but it was a mistake to cross him as I did in the following instance:

A conference in Seiznick's office on A Star is Born. Present: D.O.S. [David O. Selznick], Wellman, Budd Schulberg, and me. I said there was no reason why the character played by Lionel Stander should be as abusive as he was to Fredric March in a racetrack scene; there was no prior explanation for his nastiness. Wellman replied, "He's drunk." I said that didn't do it for me; I thought anyone who was nasty when he was drunk was nasty when he was sober. "I'm nasty when I'm drunk," Wellman said. "That proves my point," I made the mistake of saying. Our relations after that were noticeably cooler.

How about a couple of directors whose films bookend the 1950s for you—Joseph Losey and Michael Curtiz? I'm assuming The Big Night, directed by Losey, was relatively impersonal for both of you, and that Curtiz was pretty far gone by the time you did work on A Breath of Scandal.

You are right in your assumption that The Big Night was a quickie and not of any great importance to Joe. He needed the salary in order to get to exile in England before he was subpoenaed, and I think he finally did have to leave before editing was completed. Hugo Butler had been working on the script for Joe, but he was even more hard pressed and took off for Mexico with the job unfinished.[*] My wife, Frances, was working with Joe on the set, and I had recently returned to Hollywood after my prison stint in Connecticut. Joe asked me to finish Hugo's job and paid me, as I remember, a thousand dollars, which may have been his own money.

Both before and after that, I had discussions with Joe about more serious projects we were contemplating, and I looked forward to working with him; but none of them worked out.

* The credited scenarists for The Big Night are Stanley Ellin (on whose novel, Dreadful Summit, the film is based) and Joseph Losey.

Hugo Butler, one of the blacklisted generation, earned an Oscar nomination in 1940 for his screenplay for Edison, the Man. His other Hollywood credits include The Southerner (for Jean Renoir), MGM's 1938 version of A Christmas Carol, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Lassie Come Home, Miss Susie Siagle 's, From This Day Forward, A Woman of Distinction, He Ran All the Way, The Prowler, and The First Time. In Mexico during the 1950s, he wrote The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe for Luis Buñuel. He cowrote Cowboy in 1958 but was denied screen credit. After the blacklist, he was credited, notably, with his wife, Jean Rouverol, for the script of Robert Aldrich's Legend of Lylah Clare. His father was Frank Butler, the screenwriter who won an Oscar for his Going My Way co-script in 1945.

As for Michael Curtiz, the man did have a feeling for film, but he never mastered the English language. I can't really judge what it was like to work with him, because by the time I did, he was definitely in decline, and the picture, A Breath of Scandal, never a great idea to begin with, suffered as a result. Some of the scenes he shot were so bad that Paramount had to hire Vittorio De Sica anonymously to reshoot them. I was still anonymous, and Walter Bernstein, who had been cleared, accepted the dubious credit for the screenplay.[*]

So much of your career is uncredited—apart from and including the blacklist. Were you always that amenable to doctoring work? Were you diffident about credits for long periods? Did it sometimes give you a freedom, working without the baggage of your name?

I don't think my uncredited work is particularly unusual for a writer who was on the scene as long as I was. Perhaps mine has been revealed to a greater extent than most, because researchers have found studio records or old preliminary scripts for movies I never would have mentioned myself. The early ones—A Star Is Born and Nothing Sacred —were Seiznick scripts for which he encouraged us, among others, to propose improvements. The ones with Otto Preminger were on pictures he was shooting while he and I were preparing a future one. Others are projects I worked on for a while, and then someone else took over.

Perhaps a more remarkable aspect of my record, for a writer who was generally considered successful, was the number of scripts I wrote that were never produced, far exceeding the number that were.

Did you do any still uncredited and usually uncited motion picture work during the 1950s, during the height of the blacklist? Or was it all television shows and your novel? Can you cite any instances?

The only other picture of mine that was made during the blacklist was a British project called Virgin Island, a joint venture with lan McLellan Hunter. We chose a pseudonym out of the blue—Philip Rush—and when the picture opened in London, a historian of that name wrote an indignant letter to the Times, repudiating the credit. Before that, the director, Pat Jackson, had arbitrarily, without even letting us know, done a rewrite, which consisted mainly of adding unnecessary dialogue and detail. Both Sidney Poitier and John Cassavettes, who had signed to star in it on the basis of our script, expressed disappointment when they were given Jackson's script on arriving at the West Indian location.

Hunter and I also did a script for a movie Hannah Weinstein, our producer of television films, wanted to make, but she couldn't get a deal on it.

* Walter Bernstein, the finishing writer, also goes uncredited. See the interview "Walter Bernstein: A Moral Center" elsewhere in this book. A Breath of Scandal was officially credited to Sidney Howard, based on the play Olympia, by Ferenc Molnar.

Can you quantify how many television shows you wrote during the period of the 1950s? Where did you get your—not your fronts—your pseudonyms?

From 1954 to 1959, Hunter and I did five pilot films, all of which sold as TV series. In each case, we would do a number of scripts in the series and then move on to the next one, assembling a corps of writers, mostly American and blacklisted, to provide new scripts for the series that were airing. The closest I can come to the number of half-hour film scripts we did overall, the two of us, is more than 100, less than 150.

We used the same pseudonyms all the way through for correspondence and payments—we had to open bank accounts under those names—but we let Hannah Weinstein's office in England choose names to put on the scripts. They had to keep changing these because if the network people in America who bought the series noted the same name on a number of scripts, they might ask for personal contact with the writer.

Otto-Intoxication

You worked quite often with Otto Preminger. What was the basis of your rapport with him? How did you first get together with him, and why did you continue to work together over such a long period of time?

Otto was a very bright man with a lot of humor and curiosity about almost everything. He was very good company, and we spent a lot of time talking about people and the world in general rather than about the work at hand. He had the minor defect of possessing a fair amount of ego and the major one of a really bad temper. The temper could be confusing because sometimes it was real and sometimes deliberately put on to achieve his purpose. It was directed almost exclusively against actors in the course of their work on his set, but certain actors like Burgess Meredith, John Huston, and Clifton Webb were never subject to it. The most abused victim in my experience was Tom Tryon, and I think it is fair to say that Otto was responsible for turning a limited actor into a successful novelist.

It would always start comparatively mildly after a rehearsal or a take, with something like "No, that wasn't right," and build to "What are you trying to do to me?" to "You're deliberately sabotaging the whole picture!" I described the process as Otto-intoxication—a phrase he first took offense at and then found amusing.

Although he frequently criticized scenes I had written, it was completely without temper, and as far as I know, he never did treat any writer that way.

What were the pluses and minuses, for a scenarist, of writing a film script for Preminger?

His approach to a draft of a scene was to go after it word by word, detail by detail, questioning everything, and often being satisfied with the answer. His instincts often turned out to be right, but sometimes he stuck stubbornly to a

bad idea and insisted on the scene being rewritten his way. Occasionally, he would admit later that he had been wrong, sometimes after the picture was released.

Which of the Preminger films has the most of Ring Lardner in it? Why in that instance?

The two scripts on which I worked with Otto most exhaustively were never made: The first, based on Ambassador Dodd's Diary [by William E. Dodd Jr. and Martha Dodd (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1941)] and Through Embassy Eyes, by Martha Dodd [New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1939], was about the rise of Hitler and the Reichstag Fire trial in particular. Darryl Zanuck had gone off to war after making Wilson [1944] and the statement that if that didn't earn a profit, he would never permit a historical picture again. When he returned to the studio, he circulated my script among his producers and executives, and was so impressed by their praise, he offered me a contract at more money. But the figures on Wilson led him to cancel our project.

The second was my first open job after fifteen years of blacklist, and Otto, who had already used Dalton Trumbo's name on Exodus [1960], made a point of announcing he was hiring me to adapt the book Genius, by Patrick Dennis [New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1962], about an eccentric director making a movie in Mexico. Otto liked the way the script worked out but maintained that he had to have either Rex Harrison or Laurence Olivier or Alec Guinness in the role for the picture to work right. Unable to get any of them, he put it on the shelf.

So, as it turned out, I had effective influence, in each of these instances [working on a script for Preminger], only on the movie Otto happened to be shooting at the time. While I was working on the Nazi script, for example, it was Laura for which I rewrote all the Clifton Webb dialogue and contributed to a few other scenes. Jay Dratler wrote me a note of gratitude for not challenging his sole screenplay credit.

The other picture, which Otto prepared and shot while I was supposed to be on salary for Genius, was The Cardinal, starring poor Tom Tryon. Otto, who was making a largely sympathetic portrayal of a Catholic prelate, knew I was an agnostic, and he had read my satirical novel The Ecstasy of Owen Muir about Roman Catholicism in America. But he also knew I was very well informed about Catholic rituals and practices. I rewrote many scenes to achieve what he wanted, and wrote them in a way I would never have done under my own name. Interestingly enough, after I had worked on the script in New York, Boston, and Vienna, and before I went to Rome for more of it and consultations about Genius, Otto hired another skeptic, Gore Vidal, to make some changes. One night at dinner, Gore and I taunted Otto with our joint conclusion: that he had unfailingly over the years bought the rights to some of the worst novels ever written and, in most instances, had made superior movies from them.

Hollywood in the Sixties

Did you and Terry Southern ever work together in the same room on The Cincinnati Kid? I'm trying to imagine the hybrid sense of humor. Did you start the project with Peckinpah? How did it all unravel?

I have never met Terry Southern. That was one time I thought a script of mine was going to be done as I wrote it, because I sat with Peckinpah and the cast for a week of readings, during which I changed lines to fit the actors' needs or for other reasons. Then I went happily off to New York on vacation as Sam started to shoot. The next I heard was that Martin Ransahoff, the producer, had fired Sam, ostensibly for shooting a nude scene with Sharon Tate, and hired Norman Jewison to replace him. Jewison decided to change the location of the story from St. Louis to New Orleans, and hired Southern, with whom Ransahoff had just done The Loved One [1965], to do that and other changes.[*]

Peckinpah's reputation, incidentally, somewhat similar to Bill Wellman's thirty years earlier, marked him as unstable and unpredictable. In my experience with him, however, he was consistently a reasonable and helpful collaborator.

You had a unique, perhaps not to be wished for, vantage point of returning to Hollywood and screen assignments after a long, Rip van Winkle—like sleep. How had the situation changed for screenwriters in the 1960s? Was there anyone left in the executive suits that you had known? Was it a frantic, behind-the-times Hollywood?

The old moguls were beginning to die off, and there was an increasing number of more or less independent projects as opposed to ones originating at the big studios. The personnel in the front offices included some unfamiliar faces, but that trend was not as marked as it became later when, each time I traveled to California, it seemed all the executives had been replaced by much younger people. The only basic change on the business side was the fact that each script was a separate deal between a producing company and a writer, instead of an assignment under a studio contract.

But there was another change affecting style and content. The 1950s were notable for a decline in controversial themes, mostly as a reaction to McCarthyism. But it was also the period when Hollywood craftsmen became fully aware of the new wave of postwar movies in Italy, France, and elsewhere. By the time of my return in the 1960s, American filmmakers had adopted much of this European technique. At the same time, they observed or shared the new political awareness of the Vietnam [War] generation and began,

* See the interview "Terry Southern: Ultrahip" elsewhere in this volume for Southern's side of the story.

directing their appeal as always to the young, to experiment with more provocative themes.

These developments made it all the easier for me to find my way back into the business. Fortunately, my name had been solidly enough established before the blacklist for me to be easily employable after a gap of fifteen years when that institution began to dissolve. This was decidedly not true of a large percentage of writers and other film workers who were barred during the fifties, and many of them were never able to work in the business again.