7. A Widow’s Bonds

It’s better not to get married at all than to be a widow. It’s better not to get married at all. If you never marry, then at least you have the people from your father’s house.

How many kinds of pain we suffer if our husband doesn’t live in our house! Just one pain? No. Pain in all directions. Burning pain; agony. Clothes, food, mixing with others, laughter, all of that ends.

Widowhood was the last phase of life for most women in Mangaldihi. The older women whose lives I have described over the previous pages—Khudi Thakrun, Bhogi Bagdi, Choto Ma, Mejo Ma—were mostly in this stage. They had almost expected to spend part of their lives as widows, since girls were younger than their husbands at marriage, generally outlived them, and usually did not remarry.

Widowhood was also a dreaded time of life. Depending on her caste and age at widowhood, a woman could expect to face any number of hardships. Her economic condition might be precarious. She might be forced to grow old childless, with no one to care for her. She might experience the wrenching emotional pain of losing a loved spouse. She might be considered by others to be dangerously inauspicious. And, especially if a Brahman, she would be pressed by her kin to wear white clothing; avoid all “hot,” nonvegetarian foods; eat rice only once a day (an amount that left her almost fasting); avoid bodily adornments; and live in lifelong celibacy. Until recently, many Brahman families also required their widows to shave their head (a practice some of the most senior Mangaldihi widows still observed) and to sleep on the ground. In contrast, a man who lost his wife was not expected to observe any special practices and was usually encouraged to remarry. If not already senior and retired, he generally did. Thus in Mangaldihi, in 1990 out of 335 households there were only thirteen unremarried widowed men, but sixty-nine unremarried widowed women.

I take a look, in this final substantive chapter, at widowhood—both as an important dimension of women’s experiences of old age and as an illuminating means of continuing to explore local gender constructions. How were women defined, perceived, and controlled—by themselves, and by others—when they were left without a husband? What do these perceptions and practices of widowhood tell us, ultimately, about gender?

| • | • | • |

Becoming a Widow

When a husband died in Mangaldihi, his wife was taken by other widows of her household or neighborhood to a pond where she would perform the ritual to make her into a widow or bidhobā, literally “without a husband.” Married women and unmarried girls were forbidden to watch the highly inauspicious ceremony (lest it cause their own future widowhood), so I describe the ritual here based only on what several widows reported to me.[1] Many still shuddered, thinking of that horrible day.

First, the bereaved woman removed her marriage bangles of conch shell, iron, and red palā, broke them, and threw them into the pond. They were said to have “gone cold” (ṭhāṇḍā). A married woman whose bangles accidentally broke would replace them immediately, lest the broken and cold state of the bangles lead to her husband’s misfortune or death. A married woman never left her wrists bare; a widow’s arms remained empty. The widow then wiped the red vermilion or sindūr from her forehead and from the part in her hair. She had worn these marks as symbols of her married state since her husband had first placed them on her at their wedding. With vermilion the husband had symbolically activated his wife’s sexual and reproductive capacities, and these capacities were supposed to be lost with her husband’s death. If she was wearing red āltā on her feet, she washed it off.

The woman next entered the water for the “widow’s bath” (bidhobār snān), wearing for the last time one of the bright-colored saris she had worn as a married woman. When she emerged from the water she removed the colored sari to don a new white or subdued one. This sari was, when possible, supplied by the widow’s mother’s brother or some other male from her natal home, as a reminder of her natal attachments. From then on, the widow would avoid wearing red, the color of auspiciousness, warmth, sexuality, fertility, and married women. Brahman widows’ saris (and those of some lower-caste widows who chose to emulate Brahmans) were almost entirely white, thinly bordered with dark colors such as deep blue, black, or green. Widows could also wear men’s white dhotis. As I have previously noted, white was regarded as a “cool” (ṭhāṇḍā) color, symbolic of infertility, asexuality, asceticism, old age, widowhood, and death.

A final act in the making of a widow used to be the shaving of the head. In the past, high-caste widows had their heads shaved not just once but biweekly for the rest of their lives.[2] It used to be said that if a widow’s hair was allowed to grow and be tied up in a braid, it would bind the deceased husband’s spirit to her and to the places of his previous life. Mangaldihians also viewed head shaving as an act of renunciation and of severing ties. Young widows now rarely follow this ritual, but there were several older Brahman widows of Mangaldihi, including Khudi Thakrun, who continued to shave the white hair from their heads every two weeks as a sign of their widowhood.[3]

After completing their widow-making rituals, Mangaldihi widows took several different paths depending on their caste and life stage. For Brahmans, widow remarriage was absolutely forbidden, even if the widow was a young child who had never lived with her husband.[4] For all the other caste groups of Mangaldihi, although a woman could ordinarily go through a true marriage ceremony (biye) but once, widows could be remated (usually to a widowed man) by a simpler ritual called “joining” (sāngā karā), which effectively made them husband and wife. However, it was generally only women widowed at quite a young age and who were still childless who chose to do so. Widows with children feared either that they would have to leave their children behind with their in-laws or that their children would not be treated well in their new husband’s home (see also Chen and Dreze 1992:18–19).[5] Some also expressed a reluctance to relinquish any rights they might have to their deceased husband’s property, felt that they had borne enough children or were no longer of a marriageable age, or had a sense that widow remarriage was improper or embarrassing not only for Brahmans but for their caste as well. Widow remarriage in Mangaldihi, among any caste, was thus relatively rare.[6]

Widow remarriage in India must also be put into historical context. Although the British implemented the Widow Remarriage Act in 1856, thereby officially legalizing the practice, this bill had the (presumably) unintended consequence of reducing widows’ rights among the lower castes, which had always condoned widow remarriage. The new act brought with it legal restrictions regarding the disposal of the widow’s property and children on her remarriage: these were to remain within her deceased husband’s patrilineage. Many widowed women, now facing a choice between marrying again and keeping their children and property, refrained from remarriage. Thus the economic interest of the high castes in not allowing widows to remarry was firmly protected by the act, and even legally extended across caste lines.[7]

Those in Mangaldihi who remained widowed had several different options (sometimes none particularly desirable) as to where they could reside. Most widows, especially if they had children, remained in their former husbands’ or in-laws’ homes and continued to find useful work there—caring for children, performing household chores, working in the fields, and so on. If a widow had sons who were grown and married, her rightful place unquestionably continued to be with them even after her husband had passed away.[8] Childless widows, or widows with very young children, often returned to their natal homes. If not wanted or comfortable in either natal or marital home, then some widows set up a separate household, usually adjoining that of natal or marital kin. Others moved away; north Indian pilgrimage spots such as Nabadwip, Varanasi, and Brindaban, as well as Calcutta’s old age homes, are crowded with widows who feel they have no real family ties.

In West Bengal, a widow (as long as she does not remarry) is legally entitled to inherit a proportion of her husband’s property, to be divided among herself and her sons.[9] In practice, though, few widows—especially among the upper castes, who as a rule had the most property at stake—actually maintained land in their own names. They either formally or informally passed control of property to their sons, if the sons were grown, or left it in the hands of their fathers-in-law, if the widow and her children were young. A few widows who would have liked to have kept their land told me that although they knew they were legally entitled to it, who would go to the courts to fight? In lower-caste communities in Mangaldihi, where the general sense that women needed to be protected by men was less strong, some widows did manage to maintain control over property or a house. But often not much more than a tiny plot of land was at stake. Thus in Mangaldihi in 1990, there were no Brahman widowed heads of household, but a total of fifteen among several other middle and lower castes (Bagdi, Baisnab, Kora, Kulu, and Muci). Only two of these fifteen, however, were able to support themselves with income from their land; the others had to work as daily laborers.[10]

After being widowed, Brahman women had to begin performing the restrictive set of widow’s observances (bidhobār pālan) listed above, which include avoiding “hot,” nonvegetarian foods (meat, fish, eggs, onions, garlic, and certain kinds of ḍā); eating rice only once a day (substituting at other times “dry,” śukna, foods such as muṛi, parched rice, or ruṭi, flat bread); fasting on the eleventh day of the lunar month (ekādaśī); wearing white; and giving up jewelry. Because of these dietary restrictions, a Brahman widow’s food had usually to be cooked separately from that of other household members. If vegetarian food so much as touched nonvegetarian food, the widow could not eat it. Therefore, Brahman widows often kept a separate cooking fire and set of utensils for preparing their own food. At feasts, Brahman widows would eat together off to the side or in a corner.

There was considerable variation among the non-Brahman castes in Mangaldihi as to how many, if any, of these restrictions their widows followed. Most all of the non-Brahmans said that their widows did not have to observe them, but several lower-caste (including Barui, Kulu, and Suri) widows I knew said that they chose to wear white and avoid meat, fish, and eggs because they felt it was “proper” for widows to do so, or because, after their husbands died, they had no more “taste,” “need,” or “desire” for meat and brightly colored clothing. After all, Brahmans were the dominant caste in the village, in terms of not only numbers, property, and wealth but also, in some respects, moral codes. One way that members of lower castes strove to raise the ranking of their caste as a whole (or their own personal or family status) was to emulate the practices of Brahmans, a strategy that some scholars have labeled “Sanskritization” (e.g., Srinivas 1952; Singer 1972).

Across caste lines in Mangaldihi, as throughout north India, widows were considered to be inauspicious and thus had to refrain from participating in auspicious life cycle rituals such as marriage. Widows could attend and watch such ceremonies, but they could not perform any of the rituals; nor could they touch the bride or groom, or cook and serve food. Contrary to what Lina Fruzzetti finds in the Vishnupur region of West Bengal (1982:106), widowed mothers in Mangaldihi could not even participate in their own daughters’ weddings.

I witnessed several women become widows over my stay in Mangaldihi and collected the stories of many others who vividly remembered the experience. Entering widowhood is painful and traumatic for most women, who simultaneously lose their husbands and are transformed into other, alien beings. Before moving on to analyze these transformations, I will relate the bitter story of how one Brahman woman of Mangaldihi—Kayera Bou, or “the wife from Kayera”—became a widow many years ago.

Kayera Bou and her husband had been married for about fifteen years, ever since she was sixteen and her husband nineteen, but they had produced no children together. Her husband had been ill with diabetes (“sugar”) for several years before he died, and she stayed by his side constantly nursing him. She told me that her head had become “hot” (garam), or mentally unstable, because of worry about her husband’s health and her childlessness. So her father came one day to take her away for a while to a mental health sanatorium in Ranchi, several hours away by train. Her husband died while she was away. I quote lengthy excerpts from the story she told me to preserve the power of her own words in describing her traumatic transformation into a widow:

And so I came home two months later [from Ranchi]. I came wearing sindūr,āltā, everything. I had asked for it all to be put on, and they all lovingly put it on me for the journey. I didn’t then have any good bracelets for my arms, so I said to my brother who had come to get me, “My husband’s harm (akalyāṇ) will happen. Bring me some bracelets.” I put on the bracelets, without knowing that I would immediately have to take them off again and break them. Our bracelets break [when we become widows]. We can’t wear bracelets any more. When you get married, you have iron bracelets put on you. And sindūr (vermilion in the part of the hair). These are our signs of marriage. Both of these go away. These are both the husband’s things, and both of these go away. For life.

So I came home [to my father’s house].[11] It was night when I arrived. My father made me some śrbat (sugar water) to drink. But my mother didn’t come, because she knew she would start to cry. I asked where she was, and my father said that she was coming. They were keeping her away because she was crying so hard. My father didn’t want to let me know right away. He said, “Let her rest a bit.” And I was wearing sindūr and āltā! And what a fair complexion I had gained in Ranchi! Then my mother showed up weeping. I didn’t understand anything.

And then what we have to do [the widow’s ritual] was done. Our maidservant took me to the water—my mother couldn’t go. Those whose husbands are still alive can’t watch the kholā-parā (widow’s ritual).[12] My mother wanted to take me, but no one would let her because my father was still alive. So our maidservant, who was a widow, took me to the water. I had to take off all of those things and be bathed. And when I understood what was happening, I began to sob. I beat my head and cried all night long. I had to be taken to the water, take off all of those things and throw them away, and be bathed. Then where was the āltā? And where were the ornaments? And good clothes? Where was anything? One after another they were all sunk in the water. Everything became surrounded with gloom (kāli). When he left, everything became gloom. Sadness.

When you didn’t get any letters from your husband for a long time [she said to me], I could understand how awful you must feel. A husband is such a thing. I abandoned everything else, and my eagerness was for one person only. I was coming back from Ranchi with such hope and expectation. I sobbed and sobbed thinking of all the hope I had come from Ranchi with, expecting that I would see him again.…

And then they said I wouldn’t be able to eat all that any more. At night they began to take out some muṛi (parched rice) to feed me. My mother was saying, “I won’t be able to give her muṛi. How can I give her muṛi and eat rice myself?” But my father told her that she would have to. My mother said, “No! I won’t be able to. I’m going to feed her rice. Society (samāj)! Let society happen [i.e., let people talk]! She’s my child. I’m going to feed her. Then later whatever happens will happen.”

But out of embarrassment (lajjāe) in front of everyone, she wasn’t able to feed me [rice]. People would have seen and said to her, “Oh, you’re feeding her rice? ” Perhaps my husband’s sister [who was married into that village] would see and say, “You’re feeding her this? ” and then she would go around slandering us and telling everyone that my mother was feeding me. That’s the fault (doṣ) of Bengalis, isn’t it? They go around talking about who’s feeding whom what. While at the same time my mother was saying, “She’s never eaten muṛi in her whole life. I can’t give her muṛi now to chew. She’ll never be able to eat muṛi. ”

Muṛi at night, and vegetarian rice (nirāmiṣ bhāt) in the day. How many kinds of pain we suffer if our husband doesn’t live in our house! Just one pain? No. Pain in all directions. Burning pain; agony. Clothes, food, mixing with others, laughter, all of that ends. If I just laugh with someone? Then others say, “Look! She’s laughing with him. And her husband is dead. Chi! Chi!” And they begin to talk. My husband’s relatives would say all those kinds of things. They would reproach me. They would say, “None of that will happen in our house. You’ve come to our house. You won’t talk to any man.” I lived in fear of them all. I wouldn’t talk to anyone. My health was still good at that time. They thought maybe I would turn my mind toward someone and become infatuated, through mixing. They would tell me not to look at anyone else. That there was no one like one’s own husband. That even to look at another man was bad. Our women have to live carefully like that. Just like unmarried women live carefully, so must widows live carefully. An unmarried girl’s parents must look after her carefully as long as she’s unmarried, and so must a widow’s mother-in-law look after the widow when her husband dies. A widow must live in fear of her mother-in-law.

Everything for us is forbidden. Our food goes, our clothing goes, everything. Decorations, powder, all that. But if I put on a little powder, what will happen? Let them say what they will. They can’t reproach me. I didn’t do anything unjust (anyāe). Then why can’t I fulfill a little fancy like that? And what if I want to wear a good, colored sari? But I can’t wear one; it won’t happen.

I heard many other stories like this one during my time in Mangaldihi. One woman told of how she was married at age two—as used to be common earlier in the century—and widowed at age eight, passing the rest of her life as a widow. Why do widows perform this rigorous set of practices that set them apart from other married women and from their own former selves? What do these practices reveal about the ways in which women, as wives and then as widows, were constituted as persons in Mangaldihi? The remainder of this chapter is devoted to answering these questions.

| • | • | • |

Sexuality and Slander, Devotion and Destruction

Widows and their families in Mangaldihi presented various explanations of why widows may choose, and their families may press them, to observe these rigors of widowhood. Their reasoning spoke to notions about female sexuality, the importance of honor or a “name,” and the complex bodily and moral relationship between a woman and her husband.

Controlling Sexuality

The most common rationale as to why widows were pressed to eat vegetarian diets and rice only once a day, to fast on the eleventh day of the lunar month, to wear white, and to forsake bodily adornments was that these were defensive measures aimed at controlling a widow’s sexuality. The widow’s diet was said (by men and women, widows and nonwidows) to “reduce sexual desire (kām),” to “decrease blood (rakta),” to make the body “cool (ṭhāṇḍā),” to make the widow “thin and ugly,” to keep her from “wanting any man.” Sadanda’s Ma, a senior Brahman widow, explained articulately: “These eating rules were originally designed to prevent young widows’ bodies from becoming hot (garam) and so ruining their character (svabhāb) and dharma (social-moral order). Fasting is not for either pāp (sin) or puṇya (merit). Doing it doesn’t produce puṇya, nor does not doing it make pāp. It is simply to weaken the body.” A group of Brahman co-wives (or sisters-in-law) expressed similar ideas, agreeing that a widow follows the observances “to make her thin and ugly, and to reduce her sexual desire (kām), since she cannot remarry.” (Their senior widowed mother-in-law listening to us interjected: “It’s very difficult. It’s better to die than do all of that.”) Bhogi Bagdi commented, “If a widow wears a good colored sari, everyone will come to make love to her.”

Recall that dominant discourses within Mangaldihi presented women as having more sexual heat and desire than men. This sexual heat could be particularly problematic for a widow, because (as people put it) her sexuality had been activated and opened through marriage but was now no longer controlled by a husband. Widows also had no acceptable way of dissipating the heat of their pent-up sexual desire. Several villagers commented that women who are accustomed to having sexual relations and suddenly cease have the most sexual desire of all. Many therefore felt that young widows constantly threatened to become promiscuous, injuring their own honor and that of their families and contaminating their bodies and households with the sexual fluids of other men.

In fact, the local prostitutes while I was in Mangaldihi were widows: one Brahman woman (who had actually been expelled by her family from the village and worked in a nearby town), one Bagdi woman, and one Muci woman. They were sometimes called rā–i, a slang term (found in many north Indian languages) translatable as “slut” and used to refer both to prostitutes and to widows.[13] The double meaning of this term speaks not only to the fact that widows were often considered dangerously promiscuous but also to their precarious economic position. Some young widows, who are supported by neither their natal nor marital families, feel compelled to become prostitutes to survive.[14]

The Bagdi and Muci widow-prostitutes were both young women who had returned to Mangaldihi to live with their mothers (both of whom were, incidentally, also widows). Prostitute widows fared better in their natal communities than in their marital villages. (In fact, I never heard of a prostitute working from her marital community.) Because a woman, once married, is no longer a real part of her natal family line, her actions do not affect her natal family as much as they would her husband’s family. Her natal family may also be more loving and understanding of the problems she faces. The Muci woman had a small child; perhaps that is why she had not remarried. The Bagdi woman, Pratima, was childless and ordinarily would have remarried, but her only close natal kin were a landless widowed mother and a young brother, neither of whom seemed to have had the means to arrange a second marriage for her. The Brahman widow-prostitute, Chobi, was a childless daughter from one of the most prestigious families of Mangaldihi, but her family members had broken off all relations with her many years earlier and would not even mention her name to me when giving me their family’s genealogical information. When I ended up meeting her, she told me that she preferred her life as a prostitute in town to the life she would have had in the village as a lifelong Brahman widow.

Villagers cited the perceived dangers of women formerly married but now not matched with men in explaining why widows must rigorously discipline their bodies. Eating a vegetarian diet free of all hot (garam) foods—eggs, fish, meat, onions, garlic, heating forms of ḍāl—counteracts a widow’s pent-up sexual heat to help keep her free from illicit sexual liaisons. A diet of cool foods was likewise recommended for those men, such as sannyāsīs or sādhus (ascetics), who had chosen to be celibate. Similarly, people told me, a widow must only eat rice once a day so that her body will become increasingly dry (śukna) and weak (durbal), processes that further reduce her sexual energy, curb her capacities to transact with others, and make her thinner and less attractive to men. Dressed in a plain white sari, bare of ornaments, thin from continual fasting, and perhaps also disfigured by cropped hair, a widow was supposed to become an asexual and unattractive woman.

For younger widows, such cooling and desiccating of their bodies was tantamount to premature aging. Although no one volunteered this comparison to me, when I tried it out on them most seemed to find it persuasive. Widows, like older people, wore white, were expected to cease sexual activity, and experienced the cooling and drying of their bodies. The difference was that older people performed these practices more or less willingly, aiming to loosen their ties of maya and cool their bodies and selves in preparation for dying (see chapter 4). The practices were viewed as in keeping with the natural changes taking place within their bodies and families during the “senior” or “grown” life phase. For younger widows, though, the fetters of widowhood served to transform them socially, before the time naturally determined by physiology, into old women. Several commented to me that older, postmenopausal widows actually would not have to observe the widow’s restrictive code if they did not wish to, because their bodies were naturally cool and dry due to age; but most senior Brahman widows, at least, observed these practices anyway, out of “habit” or aversion to being criticized by others.

Protecting a “Name”

Probably the second most common reason I was given as to why widows felt compelled to observe the widow’s regulations was their wish to avoid slander and to protect the honor or “name” (nām) of themselves and their families. When discussing with me why widows do not remarry, a group of Brahman women chimed together, “Because a household has a reputation, a respect, does it not? People would say, ‘These people’s daughter or daughter-in-law got married twice?! Her husband has already died once, and she’s getting married again?!’” The women added that widows do have affairs; although an affair is “even worse” than remarrying (from the perspective of dharma, or morality), it can take place privately. There is more slander (nindā) from a public remarriage, so that is why widows do not remarry.

When, as we saw above, Kayera Bou’s mother made the painful decision to feed her own newly widowed daughter dried muṛi rather than boiled rice, it was fear of slander, not a conviction of the moral necessity of the practice, that drove her: “My mother was saying, ‘I won’t be able to give her muṛi. How can I give her muṛi and eat rice myself’? But my father told her that she would have to. My mother said, “No! I won’t be able to.…Society! Let society happen! She’s my child.…But out of embarrassment in front of everyone, she wasn’t able to feed me [rice]. People would have seen and said to her, ‘Oh, you’re feeding her rice?’…That’s the fault of Bengalis, isn’t it? They go around talking about who’s feeding whom what.”

I asked Thakurma, a senior Suri widow, “What would happen if you wore a red sari?” Thakurma and her neighbor Bandana answered together, “People would slander! (Loke nindā korbe!).” I continued, “No harm would happen to your husband?” Bandana laughed a little and replied, “No, nothing at all will happen to him. ” Thakurma agreed: “Where is my husband’s harm? He’s gone.” Bandana went on: “Nothing at all would happen to him. He didn’t even forbid her to wear colored saris after he died; he said nothing like that. It’s just that in our country, if widows wear colored saris, they will be slandered (nindā habe), they will feel embarrassed (lajjā habe).”

Widows motivated by a concern for their own, and their families’, reputations did not necessarily internalize the ideologies of a widow’s dangerous sexuality when choosing to accept the terms of widowhood; they rather wished to avoid dishonoring themselves and their kin. Kayera Bou’s words reflected just such a stance: “But if I put on a little powder, what will happen? Let them say what they will. They can’t reproach me. I didn’t do anything unjust. Then why can’t I fulfill a little fancy like that? And what if I want to wear a good, colored sari? But I can’t wear one; it won’t happen.” Widows in the region who reached old age after long lives of ascetic widowhood often earned a great deal of respect for their self-sacrifice and perseverance. Working for that social acceptance and respect, however arduous to achieve, seemed for most more attractive than having to endure slander, and even ostracism, by openly thwarting the codes of widowhood.

Powers of Devotion

A third reason some villagers gave for the widow’s disciplined lifestyle was that widows were continuing to live devoted to their husbands. Girls in the region were in many ways raised to think of devotion to a husband as one of the highest and most appropriate aims of a woman’s life. During her marriage ceremony, a bride would speak mantras and take vows that were to infuse in her a lifelong devotion (bhaktī) for her husband, who was to be to her like a god or lord. In fact, two of the common Bengali terms for “husband”—svāmī and pati—also mean “lord” (cf. Fruzzetti 1982:13). One image of the virtuous wife found throughout north India is that of a pativrata, literally “she who takes a vow (vrat) of devotion to her husband (pati).” Married women in Mangaldihi did expend a good deal of daily effort serving their husbands—cooking, feeding them, supplying water, and so forth. They applied vermilion to their hair, wore married women’s bangles, and performed women’s rituals (meyeder vrata)—all practices aimed toward protecting the longevity and well-being of their husbands.

Even after a husband’s death, some told me, a widow is able to continue to live a life of devotion to him. Gurusaday Mukherjee lectured me on several occasions as to the meaning and purpose of the widow’s regime (perhaps from quite an idealized and traditional perspective, since of course he himself was not a widow): “Even these days, even though many are telling widows that they can remarry and eat nonvegetarian foods, they will willingly, on their own accord, remain as traditional widows, because their minds are focused on their husbands.” Several widows of my acquaintance expressed similar views. Debu’s Ma, a senior high-caste (Kayastha) widow from the neighboring village of Batikar, spoke with a serene certainty about the importance of following the widow’s regime. I asked, “What would happen if you didn’t do these things?” “It’s a matter of dharma (morality, order),” she replied, “ Dharma would be ruined.” “Would your husband be harmed?” “Husband?” Debu’s Ma laughed at first a bit, as if to disagree. Then she went on: “A husband is master, lord (pati) and must be treated with devotion (bhaktī). There is only one husband/lord (pati) in the world. Even though he is dead, he is everything. The sons and wife must live thinking about him. They do this for his blessing (āśīrbād). They do praṇām to his photograph or footprints every day.…A husband is the woman’s guru; he is the highest lord (parampati). If a wife worships and serves her husband, then no other dharma is necessary.” Other widows declared that along with upholding dharma, they could bring merit (puṇya) and good karma to themselves, their sons, their households, and perhaps their deceased husbands, through faithfully observing the widow’s code.

Several villagers also spoke with admiration of those who had chosen to become Satis in the past, burning themselves on their husbands’ funeral pyres, and they compared the wifely devotion of today’s ascetic widows to that of a Sati (which literally means a “good woman”).[15] The popular myths told by villagers about Behula, a woman who floats down the river of death with the corpse of her husband in her lap, and about Savitri, who wins her dead husband back from Yamaraj, the god of death, portray women who gain incredible, auspicious powers by remaining devoted to their husbands even after death. Both of these illustrative tales are well worth retelling here. Married women and girls in Mangaldihi gathered once a year to perform the story of Savitri and pay homage to her on the fourteenth day after the full moon in the hot summer month of Jyaistha. In doing so they both promoted the well-being and long lives of husbands and gained edification in wifely devotion. On the occasion I attended, a Brahman wife recited the story to about twenty-five other women, reading frequently from the paperback pamphlet Meyeder Vratakathā (n.d., ed. G. Bhattacharjya:62–66). The following is an abbreviated translation of the tale:[16]

There was a king named Asvapati who ruled a land called Madra. He had a daughter, born to him by the grace of the goddess Savitri, whom he named Savitri. When it was time for her to marry, the king searched in all directions for a worthy groom, but to no avail. Finally, Savitri decided to go out herself to search for a husband, taking several companions with her. They traveled to many places and eventually came upon an ashram in a forest where an old blind man named Dyumatsen lived with his son and blind wife. Dyumatsen had been king of a nearby kingdom, but had lost it to enemies. When Savitri saw this man’s son, Satyaban, she vowed that only he would be her husband.

Savitri returned to her father to tell him of her decision, and the king asked a great seer what he knew of Savitri’s chosen spouse. The seer said ominously, “Savitri’s marriage with Satyaban cannot happen. For within a year after he is married, Satyaban will die.”

The king Asvapati became very distraught and tried to dissuade his daughter from marrying Satyaban. But Savitri was unwavering in her resolve, saying, “Father, he whom I have accepted in my mind as my lord and husband I cannot forsake. I will not be able to marry anyone but him.” And seeing her firm resolve, the king and the seer both agreed that the marriage should take place.

So Savitri was married to Satyaban. Savitri went to live in the ashram of her father-in-law, and began immediately to serve her blind old parents-in-law with much devotion. Savitri soon became beloved to them all. But she herself was stung every night by the memory of the words the seer had told her about the future. She counted every day from the wedding until there were only three days left before the end of the year.

On that day, Satyaban was planning to set out for the forest to bring back some wood and fruit. Savitri pleaded with her mother-in-law to let her accompany him, and after finally receiving permission, she departed into the woods with her husband. Soon Satyaban’s head began to ache sharply and he lay down with his head on Savitri’s lap. He became still with pain and then lost consciousness. As Savitri watched, his life slowly left his body. Evening was coming on, but Savitri was not afraid. She took her husband’s body into her lap and sat there.

Presently Yamaraj, the god of death, arrived and said to Savitri, “Your husband has died. I have come here to take away his spirit (prāṇ). Go now and return to your home to do his funeral rites for him properly.” Saying this, Yamaraj took Satyaban’s spirit out from his body and began walking away.

But Savitri began to follow right after Yamaraj. Yamaraj turned to ask, “Dear, where are you going?” Savitri answered, “God, wherever you take my husband, there I will go,” and she began to plead with him to give her husband’s life back. Yamaraj was impressed with Savitri’s Sati-like[17] devotion to her husband, and said to her, “Sati! Aside from the boon of granting Satyaban’s life, I will give you any three boons that you desire.”

So Savitri first asked that sight be restored to both of her parents-in-law. Next she asked that her father-in-law regain rule over his kingdom. And finally she asked that her own father, who was sonless, be given one hundred sons. Yamaraj granted each of these boons, but still Savitri did not give up following him. So finally Yamaraj turned to her and said, “I will give you one more boon, other than the life of your husband, and then you will absolutely have to leave.”

This time Savitri asked that she herself, with Satyaban’s semen, would be the mother of one hundred sons. Without thinking, Yamaraj assented, and told her now finally to go on her way. But Savitri responded, “God, how can I give birth to a hundred sons if you do not give my husband’s life back to me?” Yamaraj realized that he had lost in the game of wits (buddhir khelā) with Savitri, and he was compelled to restore Satyaban’s life.

In this way, Savitri, acting as a Sati, gave her parents-in-law back their sight, her father-in-law back his kingdom, her father a hundred sons, and her husband his life.

The Bengali myth of Behula in the Manasa Mangal similarly tells of how a wife’s self-sacrificing devotion brings her husband back even from death. Mangaldihi villagers knew this story well and told it to illustrate the powers of wifely devotion, as well as the merits of worshiping Manasa, the goddess of snakes. The following is an abbreviated reconstruction of the Behula story as it was sung to me over several long sessions by Rabilal Ruidas, the blind senior beggar of Mangaldihi’s leatherworker (Muci) caste, also known as the musician (Bayen) caste:[18]

There was a man named Cando who had six sons and six daughters-in-law, but because he would not worship the goddess Manasa, the goddess of snakes, she caused each of his sons to die by snakebite one by one. The daughters-in-law thus turned one by one into widows, and soon there was no longer any red āltā on the feet of the house’s daughters-in-law, no jingling of ornaments, and no colorful saris. The house was full of mourning and gloom.

Then a seventh son, named Lakhai, was born to Cando. When Lakhai reached the age for marriage, Cando sent out his servants to locate a suitable bride. The girl Behula was chosen. But the goddess Manasa, still angry, visited Lakhai before the marriage, dressed as an old Brahman woman, and cursed him, declaring that he would die on his wedding night. Lakhai’s father Cando was afraid and ordered blacksmiths to build an iron chamber, so tightly fitted that not even an ant or a breath of wind could enter it. This is where Lakhai and Behula would sleep on their wedding night. Manasa became angry, and she frightened the blacksmith into leaving a crack so that a snake could enter the wall of the chamber.

So the wedding happened with much pomp, and on the wedding night Lakhai and Behula retired together to the iron chamber. Behula prepared to wait up all night long to guard her husband. But even as she sat awake, a snake crawled through the crack and fatally bit Lakhai on the heel. His body was placed on a raft to float down the river,[19] and although everyone pleaded with Behula to stay, she would not leave his side. She headed down the river toward the land of the gods. Along the way she encountered animals hungry for her husband’s body and men hungry for sexual favors from her. But for six months Behula warded off all of these dangers and persisted in her journey.

Finally Behula, with her husband’s corpse still beside her, reached the place where the river meets the land of the gods. She went to Siva and told him her story, imploring him to restore her husband to life. Siva sent for the goddess Manasa and they made an agreement. Manasa would restore Behula’s husband’s life, along with the lives of his six brothers. In exchange, Behula would promise that her father-in-law and the whole family would henceforth perform pūjās for Manasa.

In this way, Behula brought her husband back to life, gave her parents-in-law back their seven sons, and turned her six sisters-in-law once again into married women.

Behula is perhaps the best-known human figure in Bengali mythology and is considered an exemplar of wifely devotion. Hem Barua describes her feat: “a victory for Behula’s pure devotion, conjugal purity and faith that moves mountains. As an ideal wife she is second neither to Sita nor Savitri. Before the pure chastity and deep devotion of Behula, even heavenly powers bend and break” (1965:16; qtd. in W. L. Smith 1980:117).

A husband’s death would appear to put an end to a woman’s wifely powers of devotion and to be evidence of a woman’s failure (a point I will return to shortly). But there was also a sense, expressed in such popular myths as well as in everyday talk, that if a widow remained devoted to her husband then to some extent she could keep her auspicious, life-maintaining powers alive. Her status as a wife was radically altered, but not entirely effaced. By accepting the lifestyle of widowhood, a woman continued to define herself and present herself to others as a wife devoted to her husband—thereby partially circumventing the reality of her husband’s death.

Powers of Destruction

A fourth factor crucial to understanding the position of widows in Mangaldihi is tied to perceptions of a widow’s dangerous, destructive potential. If a virtuous, devoted wife possesses the power to nurture and sustain her husband, then something must have been wrong or deficient (local reasoning went) in the nurturance provided by any woman whose husband died.[20] Widows frequently told me that they felt it was their fault that their husbands had died—either because of their failings as a wife, or because of some horrendous wrong performed in a previous life, or simply because of their own personal ill fate (kapāl,adṛṣṭa). Gurusaday Mukherjee gave me a list of conditions that could be considered the fruit of sins (pāper phal), with widowhood at the top of the list, followed by barrenness, the destruction of a lineage (baṃśa), blindness, and being a cow that has to labor in the fields.

Sometimes widows were imaged as devouring creatures. Gurusaday Mukherjee told me that a widow who does not behave properly becomes a vulture (śākun) in her next life, preying on the dead flesh of cows and other large animals. A senior Kayastha widow, Mita’s Ma, who had become blind in one eye told me with grief that she saw herself as a rākshasī, a mythological female creature who devours everything, including people. Her husband had died early and then her son-in-law, leaving both mother and daughter widows. She said mournfully that she had “eaten” these people, and was fearful that she would cause some such disaster again (cf. M. Bandyopadhyay 1990:150). Rumors were spread that Pratima, the young Bagdi widow who had become a prostitute, had poisoned her husband. Another widow, Rani (of the Kora caste), told of how her husband had died “from diarrhea” when they were both still very young. Soon after, in just one day, her two-year-old son sickened and also died. “After that,” she said, “my parents-in-law began pestering me even more. They didn’t want to see any more of me. They called me a poison bride (biṣkanyā). So my brothers came to get me,” and she never went back. A widow can also be feared as a devouring witch, as in Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay’s story “The Witch” (1990).

This destructive potential was the primary reason that widows were considered to be so exceedingly inauspicious (amangal,aśubha) and were peripheralized within the family, if not expelled. Conversely, a husband whose wife died was not viewed as culpable or dangerous. I asked Mejo Ma, who had years earlier been married to a man whose previous two wives had died, if she had been nervous about his inauspiciousness when marrying him. She stated matter-of-factly (after admitting that she had actually not been told about his previous wives’ deaths before the wedding), “No one blames a man for his wife’s death; they only blame widows.” Women were thus presented as having an agency that must be carefully controlled. They could use their powers to support and sustain others, but also to destroy.

| • | • | • |

Unseverable Bonds

The villagers’ reasoning summarized above points to important facets of women’s experiences of widowhood in Mangaldihi and to local constructions of what it is to be a woman. But it does not yet entirely explain how a woman’s personhood—or the ties making up her self—were altered through the death of her spouse, and why a woman’s transformation into widowhood was so different from that of a man.

To understand these issues it is crucial to take into account the kinds of connections women shared with their husbands. It seemed to me that the bodily connections (samparka) and ties of maya between a woman and her husband were believed in significant respects to remain, even after his death. What necessarily endured was not so much the emotional dimensions of maya (some widows spoke of an ongoing emotional attachment to their husbands, and others did not) but people’s perceptions of a woman after marriage: a woman would always be defined in terms of her relationship with her husband, as his “half body” (ardhānginī), even if he died. Thus the widow was in effect married to a corpse, herself half dead. A widow in this way remained perpetually in a state similar to the death impurity (or aśauc) that other surviving relatives experienced only temporarily.

This comparison between the condition of widows and those suffering death-separation impurity first occurred to me as I began to notice their many correspondences (table 8). Widows and older people share many practices, too, but the codes for conduct of widows and death-impure persons are even more similar. Like a widow, persons suffering death impurity were expected to remain celibate; avoid “hot,” nonvegetarian foods; limit intake of boiled rice; restrict their sharing of food with others; and avoid participating in auspicious rituals. Males suffering from death impurity and older, more traditional widows also had their heads shaved.

| Prescribed Practices | Widows | Older People | Death-Impure Persons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remain celibate | X | X | X |

| Religious orientation | X | X | ? |

| Wear white | X | X | X[*] |

| "Cool" the body | X | X | X |

| Avoid "hot" foods | X | — | X |

| Limit intake of boiled rice (bhāt) | X | — | X |

| Restrict sharing food | X | — | X |

| Keep out of auspicious rituals | X | — | X |

| Shave the head | X[†] | — | X[**] |

| Sleep on the ground | X[†] | — | X[†] |

| KEY: — = Absent. X = Present. * Performed by chief mourner only (usually the eldest son of the deceased).† Traditionally prescribed but not commonly performed now.** Performed at the end of the period of death impurity and by males only. | |||

As discussed in chapter 5, these practices all reduced the likelihood that personal properties would be transferred among people. During the transitional phase of death impurity, the survivors limited their interactions, both in order to separate themselves from the deceased person and to avoid infecting others in the community with their condition. The aim was to cut the lingering bodily emotional connections between the survivors and the deceased, so that the departed spirit as well as the survivors could move on to form new relationships. For other survivors, the practices of death-impurity ended with the final funeral rites after ten to thirty days. But the incapacity and inauspicious (aśubha) condition of the widow was permanent, because her putatively indissoluble merger with him in marriage appears to have made her the “half body” and lifelong soul mate of her husband. When he was dead, her living bodily presence made her not merely a sexual hazard (if she was still young) but also a repulsive anomaly.

Others, such as Parvati Athavale (1930:46–50), Veena Das (1979:98), and Pandurang Kane (1968–75:2.592), have compared the Hindu widow’s practices to those not of death-impure persons but of the ascetic or sannyasi. Some of my informants, too, suggested that a widow is in some ways like a female ascetic. However, this comparison fails to adequately account for the widow’s unusual relationship to death. Manisha Roy (1992 [1972]:146) suggests in passing that Bengali widows are “polluted,” but she does not specify in what way. Recall that those in Mangaldihi did not regard widows as “polluted” or “impure” in the sense of the everyday impurities (aśuddhatā) that stem from menstruation, sexual intercourse, saliva, dog-doo, contact with lower castes, and the like (see chapter 6). Indeed, in this regard high-caste and older widows especially were thought to be uniquely pure (śuddha), because their lifestyles (celibacy, vegetarian diets, being postmenopausal, etc.) made their bodies contained, cool, pure, like those of gods (ṭhākur) and men. I. Julia Leslie’s study of the eighteenth-century Guide to the Religious Status and Duties of Women (Strīdharmapaddhati) by Tryambaka seems to support my assertion, though, that the widow’s condition is similar to that of death impurity (aśauc). Tryambaka writes: “Just as the body, bereft of life, in that moment becomes impure [aśucitaṃ], so the woman bereft of her husband is always impure [aśuciḥ],[21] even if she has bathed properly. Of all inauspicious things, the widow is the most inauspicious” (qtd. in Leslie 1989:303).

To grasp the peculiar relationship of the widow to her dead husband, we must examine once more the nature of the Bengali marital union. As already noted, in a Bengali marriage the bride is described as becoming the “half body” or ardhānginī of her husband. Both the husband and wife become “whole” through this complementary union, but it is effected by an asymmetrical merger in which the woman becomes part of the man’s body and not vice versa (cf. Inden and Nicholas 1976:41–50; Fruzzetti 1982:103–4). During the marriage ritual the bride repeatedly absorbs substances originating from the groom’s body and household, changes her last name and lineage affiliation to match her husband, and moves to his place of residence. These actions seemed to create an irreversible, indestructible entity made of the husband plus wife: the woman would be part of her husband’s body for life.

The asymmetry generally thus assumed in the marital relation was extreme, for the husband was not considered to be the wife’s half body and, unlike her, was not said to be diminished by his partner’s death. If she died first, his person remained whole and free to remarry; the temporary incapacity of death impurity for him lasted no longer than that of other close survivors. There was, in fact, no commonly used term to describe a widowed man in Mangaldihi, suggesting that male widowhood was not a highly marked category.[22]

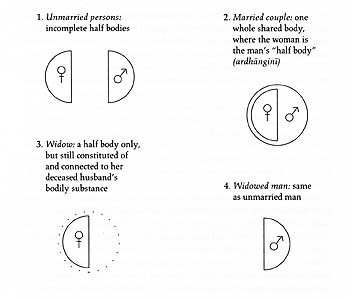

Consistent with this logic, several people told me that even if the woman dies first, her spirit remains bound to her husband and wanders around near him. This would mean, of course, that the surviving husband was not entirely free after all, because he might have to contend with her spirit. It was not uncommon for a man’s second wife to keep a photo of his deceased first wife in the family shrine, for instance, and to anoint it with vermilion every day. She thereby placated the first wife’s spirit and aided the well-being (mangal) of her husband and household. In most respects, though, the widowed man seemed to be quite unhindered. One way to represent these enduring connections of a widow with her deceased husband—in contrast to the relative freedom of the widowed man—is sketched in figure 7.

Figure 7. The widow and the widowed man.

If people in Mangaldihi viewed persons to be constituted of networks of relations, then women were in a peculiar position: their connections were made, remade, and unmade at several critical junctures over their lives, not only through aging and dying but also in marriage and widowhood. A daughter painfully attenuated her ties with her natal family and place, so that she could move on to form new ties within her husband’s home. Their families’ responses to the deaths of husbands often did even more than marriage to unmake women, mainly through once again curtailing their interpersonal connections with those in their families and communities. The only tie for a woman that seemed to be unambiguously unseverable, within the dominant patrilineal discourse of Mangaldihi, was the one she shared with her husband. That bond, which defined a woman’s very bodily substance and identity, could not be cut by a married woman, even if her husband died. This logic underlay the solitary existence endured by most women in Mangaldihi as widows as the last phase of their lives.

Stories of Tagore: Widows Trapped between the Living and the Dead

I close this chapter by examining three short stories written by Rabindranath Tagore around the turn of the century that powerfully expose the oppressiveness of a system that constructs widows as trapped between life and death.[23] These stories were not told or mentioned to me by people in Mangaldihi. But as I sat reading them from the serene cottage I had rented and sometimes retreated to in nearby Santiniketan, the town where Tagore had lived and did much of his writing, I could not help being struck by the eloquence and vividness with which Tagore portrayed the condition of local widows that I had been struggling ethnographically to discern.

Tagore focused his short stories on the ongoing social changes and lives of ordinary people during the period of the Bengal renaissance and the rise of nationalism between the 1880s and 1920s. He often depicts the female condition, and the forces that oppress women, with particular sensitivity. For Tagore, as Kalpana Bardhan (1990:14) writes, “the oppressor is ultimately some aspect of the cultural ideology and the social situation in which both men and women find themselves trapped.…The tragedy lies in the distortions that their personalities and relationships suffer under the tyranny of social mores and beliefs.” The three stories I look at treat the suffering of widows within such an ideological system, one that traps them between life and death, barring them from normal, fulfilling social relationships by making them into despised and inauspicious deathlike creatures.

The first, “Mahamaya” (Tagore 1926:148–53), presents the awful, estranged life of a woman who becomes a widow the day after her wedding. The story opens with Mahamaya as a beautiful young woman whose parents, for whatever reasons, have not yet found a suitable groom for her. She is of a Kulin Brahman family, the highest rank of Brahmans. She falls in love with a young man of the village, Rajib, who is a Brahman, but not a Kulin Brahman. When Mahamaya’s father finds out about their love, to protect the rank of the family he immediately arranges an alternative marriage for Mahamaya to a Kulin Brahman man.

This groom is already an old man; he has retired to a hut by the cremation ground where the Ganges flows, waiting to die. The wedding takes place in the hut, lit only by the dim glow of a cremation fire not far off, and the old man whispers the wedding mantras in a voice filled with the pain of his dying. Mahamaya becomes a widow the day after her wedding.

It is decided then that Mahamaya will become a sahamṛtā, one who dies with her husband. Her hands and feet are bound, and she is committed to the cremation pyre. The fire is lit and great flames leap out. But at that moment a huge storm comes upon them, releasing torrents of rain. All of the people gathered to watch take shelter in the hut, the fire goes out, and Mahamaya frees herself. She runs first to her father’s home; finding no one there, she goes to Rajib. She and Rajib determine to leave together.

But Mahamaya never removes the veil, or ghomṭā, of her sari from her face, and she lives distant and estranged from Rajib: her face has been hideously scarred by the cremation fire. The thick veil of her sari does more than simply conceal her scars; it represents the shadow of death and the social attitudes that separate her from others as a widow.

Mahamaya was now in Rajib’s house, but there was no happiness in Rajib’s life. Between them both was only the estrangement caused by Mahamaya’s veil. That small veil was just as everlasting as death, and yet it caused even more pain than death. For the pain of separation in death gradually fades away, but behind this veil were living hopes that stabbed at one every moment of every day. Mahamaya lived behind her veil with a deep, silent sorrow. She was living as if overcast by death. Rajib himself began to feel withered and hindered by having to live next to this silent and deathlike creature in his household. He had lost the Mahamaya that he had once known and had gained instead this silent, veiled figure. (1926:152)

The widow is an inherently distressing figure because she is neither fully alive nor dead. Death is a more complete separation than widowhood; it can be handled and processed through funeral rites, and its pain slowly fades away. But the widow is uniquely disturbing because she stays within society, an ever-present reminder of what could have been. She lives in other people’s households but is forever separated from them by the culturally imposed veil of her widowhood, thus existing permanently overshadowed by death.

The protagonist of a second story, “The Skeleton” (Tagore 1926:63–69), is a child widow who had died many years earlier. Her body had been donated to a school, which kept her skeleton for classroom study. One night a young student was sleeping in a room next to where the skeleton was kept when he heard something enter the room. It was the spirit of the person from whom the skeleton had come. She stayed throughout the night to tell the young man her story.

She had been married as a young child, and after only two months of marriage, her husband died and she became a widow. After looking at many signs, her father-in-law determined that she was, without a doubt, what they called a “poison bride” (biṣkanyā). Her parents-in-law expelled the ominous widow from their house and she returned quite happily to her parents’ home, too young to understand what had happened to her.

There she grew up into a beautiful young woman. Men used to look at her and she at them, and she used to dress up secretly in colorful saris with bracelets on her arms, imagining men admiring and caressing her. Then a doctor moved into the first floor of their house, and she used to enjoy visiting him for carefree talk about medicines and about how to use poisons to help sick people die.

Then one day she heard that the doctor was getting married. On the evening of his wedding, the girl slipped some poison from his office into one of his drinks; soon thereafter, as flutes played, he left for the bride’s house. She then dressed herself in a silk wedding sari, put a large streak of red vermilion in the part of her hair, and adorned herself with all of the jewelry from her chest. She took poison herself and lay down on her bed. She hoped that when people came to find her they would see her with a smile on her lips as a married woman.

“But where is that wedding night room? Where is that bride’s dress?” she asks the listening man. “I woke up to a hollow rattling sound inside of me and noticed three young students using me to learn about bone science! In my chest where happiness and sadness used to throb and where petals of youth used to bloom every day, there was a master pointing with a rod about which bones have what names. And there was no sign of that last smile that I had placed on my lips” (Tagore 1926:68). The story ends here, when dawn arrives and the spirit of the skeleton/widow silently leaves the young man to himself.

The widow in this story is a “poison bride,” causing the deaths of the men she unites with, and she is a lifeless skeleton, with passions and dreams but no means to fulfill them. This pattern—the woman as a poison bride causing her husband’s death and then turning into a skeletal widow—is repeated twice. First the girl is a real bride who is perceived to have caused her husband’s death by her nature as a poison bride, and next she is dressed as a bride who indeed does administer poison to a departing groom. At the end of each sequence, after causing her groom’s death, she becomes a skeleton. Initially, it is her existence as a widow that is skeletal: she is a beautiful woman full of dreams and throbbing life, but she is forced to live without love, fulfillment, and the capacity to unite with others. By the story’s end, the widow has literally become a hollow skeleton that possesses no signs of life or emotion.

A third story, “Living and Dead” (Tagore 1926:98–107), presents a young, childless widow, Kadambini, who is believed by others, and at first believes herself, to be dead, existing in the world only as a ghost. At the beginning of the story, she does appear to die suddenly, and her body is taken quickly to the cremation ground by men from her father-in-law’s house. The men leave her to go off to gather fuel for the fire, and she awakens alone. She had not in fact died, but had only been temporarily unconscious. Seeing the cremation ground around her in the dead of the night, she believes that she has died and that she is now a ghost. She does not know where to go, but she feels that she belongs even less to her father-in-law’s house than to her father’s home, so she returns to her natal village to a childhood girlfriend who is now married. Eventually, when the girlfriend and her husband find out that Kadambini is supposed to have died, they chase her away screaming, calling her accursed and inauspicious. Kadambini then returns to her in-law’s home and there finally realizes, when she holds her beloved nephew, that she is not a ghost. But the people of the household shriek when they see her, pleading with her not to bring misfortune upon their household and lineage, not to cause their only son to die. Kadambini finally drowns herself in a pond, and it is only by dying that she is able to prove to her tormentors that she had indeed been alive.

Here the widow’s existence is compared to that of a departed spirit or ghost (pret). The widow is, as the title suggests, both living and dead, or perhaps neither living nor dead. She does not belong in the world of the living, and yet she is trapped there, as a lonely and inauspicious being. Kadambini ponders aloud about her condition—ostensibly that of a ghost—while at her childhood friend’s house:

Widows, like ghosts, remain hovering around other people’s households, even as in some ways their “vital links” have been severed by death. But like ghosts, widows cannot fully participate in household life; like ghosts, they are frightening and cause misfortune.Who am I to you? Am I of this world? You are all laughing, crying, loving, each of you engaged in your own business, and I am only watching like a shadow. I don’t understand why God has left me in the midst of you and your worldly activities (saṃsār). You are afraid of my presence, lest I bring misfortune (amangal) into the joys of your daily lives. I, too, cannot understand what relation I have with any of you. But since God did not create another place for us to go, we must keep hovering about you, even after the vital links (bandhan) are severed. (Tagore 1926:104)

When Kadambini is referred to as a ghost, it is as a pret, a departed, disembodied spirit. A deceased person’s spirit ordinarily becomes a pret before it moves on to rebirth and ancestorhood (see chapter 5). During this transitional stage, the pret maintains attachments to its previous life in the world, yearning for food and attention from former relatives and loved ones, until the sequence of funeral rites finally cuts these attachments. The widow similarly is in a transitional state between life and death, but for an indefinite, prolonged period. When Kadambini returns to her in-law’s home, her brother-in-law beseeches her to cut all the “bindings of her maya” (māyābandhan) for the world. He pleads, “When you have taken leave of saṃsār (family, worldly life), then go ahead and tear open your bindings of maya. We’ll perform all of the funeral rites” (Tagore 1926:107). Tagore suggests that widowhood presents a sobering contrast, for society had created no rituals that could release the widow from her liminal condition. So Kadambini finally kills herself, the only act that can free her from her terrible, equivocal condition as a ghostlike widow. Widows in these stories are caught between life and death by bonds that cannot be severed—tied both to their husbands who are dead and to a life now devoid of all pleasurable content.

| • | • | • |

We see here—in Tagore’s stories, as in the discourses and practices of those I knew in Mangaldihi—a specific vision of a woman’s personhood as being permanently and substantially joined to her husband’s. A woman, once married to a man, was not easily perceived again as separate from him. In the dominant patrilineal discourse of Mangaldihi, women were transformed by marriage—in their emotions and substance—into the “half bodies” of their husbands; their lives were to be eternally devoted to their husbands’ well-being and longevity, just as their bodies were constituted and defined in and through their husbands’ bodily substances. A widow, especially if young, was disturbing not only in her possibly uncontained sexuality but in her liminality—someone who has forsaken her husband by remaining on earth, but who yet cannot ever be truly free from him to move on to form new or independent relationships and identities.

Of course, this was not the only discourse I heard from women (and men) in and around Mangaldihi. As I have stressed throughout these pages (as current postmodern sensibilities would hold), the “culture” of Mangaldihians was not univocal. Some women, and some men, rejected through their talk or practice such visions of the relationship of a woman to her husband, dead or alive, as necessarily all-encompassing. When Kayera Bou wore an occasional pair of small yet brilliant spring-green earrings, she was repudiating the ideologies dictating that a woman without a husband had no reason to dress up (though she was derided by neighborhood girls for doing so). When the young Brahman widow, Chobi, left Mangaldihi to take her own apartment and become a self-employed prostitute in town, she was choosing to reject a life defined in terms of her dead husband, asserting instead her own agency and independence (even if that meant forsaking all ties with former kin). Nonetheless, I cannot deny the force of local ideologies defining women and widows in terms of their husbands, evident in widows’ everyday practices, movements, diets, dress, and self-perceptions. Hena’s statement to me was telling: “If her husband dies, a woman’s life has no more value (dām).”

Yet one of the themes that has been emerging throughout this book is that using age as a category of analysis can provide an alternative perspective. As has already become clear from the stories told and data presented about aging women’s lives (see also chapters 3 and 6), the experiences of widowhood for those widowed at older and younger ages could be profoundly different (see also Lamb 1999). For women widowed at older ages, with grown sons to care for them, daughters-in-law to supervise, a rightful long-term place established in a home, and a body grown naturally asexual with age and thus free—as in the case of Khudi Thakrun, or Choto Ma, or Mejo Ma—widowhood did not generally have devastating social, economic, and emotional consequences. To be sure, these older widows would never be completely free from the inauspiciousness of widowhood, and they could continue for years to feel the emotional pain of losing and missing a husband. For them, widowhood also usually brought with it a transfer of a household’s economic resources and property to the younger generation, and thus their further peripheralization into old age. But widowhood in late life could also be accompanied by increased freedoms and even respect—fewer obligations tying them to the home, an attribution (for Brahman widows especially) of increased “purity” and of “manlike” and “godlike” qualities—which many older widows seemed to end up enjoying. Thus suspended amid the countervailing currents of inauspiciousness and auspiciousness, restraint and freedom, authority and peripheralization, the greater portion of Mangaldihi women lived the last phases of their lives.

Notes

1. For a similar account of the widow’s ritual in a different region of Bengal, see Fruzzetti 1982:105–6.

2. On head shaving, see Altekar 1962:160; Fuller 1900:58; Kane 1968–75:2.585; Karve 1963:66; and Subramanyam 1909.

3. It is perhaps significant that head shaving also gives widows a manlike appearance, though no one in Mangaldihi directly made this observation to me.

4. Child marriage (at least of girls under about fourteen) is not commonly practiced now, but earlier in the century many girls were married and then widowed while still children.

5. This problem of children in a new household could potentially be solved through levirate, the marriage of a widow to one of her husband’s brothers. However, although levirate is practiced elsewhere in India (Kolenda 1982, 1987a), it is not common in this region of West Bengal (cf. Fruzzetti 1982:103).

6. See Wadley 1995 for an illuminating discussion of factors (such as caste, property, age, family types) affecting widow remarriage in Karimpur, north India.

7. On the effects of the Widow Remarriage Act, see Carrol 1983; Chattopadhyaya 1983:54; Chowdhry 1989:321, 1994:101–2; and Sangari and Vaid 1989:16–17.

8. Carol Vlassoff (1990) provides an interesting study of widows’ perceptions of the value of sons in a village of Maharashtra. Although many of the widows in her study did not gain significant economic security from their sons, those living with sons evaluated their situations as happy.

9. See Agarwal 1994 and Chowdhry 1995 for discussions of Hindu widows’ inheritance rights in historical context.

10. Lamb (1999) offers more detail about widows’ sources of support (access to property, heading households, etc.) across caste, class, and age lines in Mangaldihi. Wadley (1995) provides an enlightening discussion of age, property, and widowhood in Karimpur, north India.

11. Kayera Bou first went to her father’s home for several days, but she soon returned to her śvaśur bāṛi in Mangaldihi, where she still lives with her mother-in-law, her husband’s sister’s son, his wife, and their three children.

12. Kholā-parā, which literally means “taking off and putting on,” is one name for the ritual of becoming a widow; it refers to the act of removing married woman’s garb and putting on the widow’s dress.

13. On “widow-prostitutes,” see also Das 1979:97–98; Harlan 1995:218; and Minturn 1993:235–36.

14. Mahasweta Devi’s “Dhowli” (1990:185–205) offers a powerful fictional portrayal of a beautiful, low-caste young widow who is forced, with tragic consequences, to become a prostitute after her Brahman lover deserts and turns against her.

15. For more on the historical practice of sati and British colonial reactions to it, see P. Chatterjee 1989, 1990; Hawley 1994; Mani 1990, 1992, 1998; Nandy 1990a; Narasimhan 1990; and Ward 1820. For discussions of the more recent incidence of sati in 1987, that of Rup Kanwar in Rajasthan, see Das 1995:107–17; Grover 1990:40–47; Harlan 1992:13; Nandy 1995; Narasimhan 1990; Oldenburg 1994; and Weisman 1987.

16. The Mahābhārata offers a similar archetype (see, e.g., Van Buitenen 1975:760–78).

17. Yamaraj calls Savitri a “good woman”; “Sati” is also the name given to women who follow their husbands in death by burning with them on the cremation pyre.

18. My research assistant Dipu helped me transcribe and edit the story. This version is included not as a richly textured example of an oral performance but rather for its thematic content. Dimock (1963:195–294), Sen (1923), and W. L. Smith (1980) provide other versions of the story.

19. According to W. L. Smith (1980:116), Bengalis commonly used to set the dead bodies of snakebite victims adrift down a river on a raft made of banana stalks, in the hope that they would be found by an ojhā, or healer, who would be able to revive them.

20. This form of reasoning is common throughout India (e.g., Chakravarti 1995:2250; Marglin 1985c:53–55; Samanta 1992:73).

21. The Sanskrit terms aśucitaṃ and aśuciḥ used here are related to the Bengali aśauc, meaning literally “impure,” from a (negative prefix) and śuci (pure). Remember that in Bengali, aśauc refers specifically to the impurity stemming from death and childbirth only, and not to everyday impurity, aśuddhatā.

22. There is a Bengali word for widower, bipatnīk (without a wife); but this learned term was not in common usage in the Mangaldihi region, and in fact most whom I asked professed no knowledge of it.

23. These three stories (“Mahāmāyā,” “Kangkāl,” and “Jībita O Mṛita”) appear in Bengali in Tagore’s collection of stories titled Galpaguccha (1926). “Jībita O Mṛita” has also been translated into English by Kalpana Bardhan (1990:51–61) as “The Living and the Dead.”