6. Le Havre, Tuberculosis Capital of the Nineteenth Century

Le Havre…occupies the first rank among the most unhealthy French cities.…Phthisis is, in Le Havre, perpetually endemic.

The city of Le Havre has never been unhealthy.

Mayor Marais’s sanguine claim that his city had never been unhealthy was belied not only by all available statistics but also even by the actions of the local government and civic leaders from the 1880s on. Year after year, from the time such figures were kept, Le Havre ranked highest in per capita tuberculosis mortality of all major French cities. It was consistently at or near the top in overall mortality as well. Social investigators, hygienists, and public officials regularly decried the lamentable state of Le Havre’s housing stock and its notorious degree of alcohol consumption. Moreover, to an extent unmatched in any other French city, local elites attempted to respond to the challenges of ill health and urban pathology with a strategy of public and private action aimed at the material and moral improvement of the working class. This chapter tells the story of these efforts: their origins, their vicissitudes, the directions in which they were oriented, the controversies to which they gave rise, and their impact.

How did the War on Tuberculosis actually work at street level? Some answers have already been suggested. The experience of Le Havre more than any other city, with its exceedingly high incidence of tuberculosis and its vigorous reform efforts, can serve as a window on the everyday ramifications of medical knowledge. Le Havre is in no way typical as a case study of tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France; it is an extreme example. But for this very reason, the tensions, anxieties, and responses aroused by tuberculosis are exaggerated there and exposed to view. They appear in dramatic relief, and seen in relief the local meanings of tuberculosis become clearer.

One hundred years ago, wealthy Havrais notables literally looked down on the poor. Le Havre occupied a strip of land bounded by the Seine on the south and on the north by the hills that stretch from the coastal town of Sainte-Adresse to Graville northeast of the city. Working-class families occupied the flat quarters near the port, the workplace of many of the city’s residents. The merchants and bankers who made their fortunes from Le Havre’s growing commercial role in the nineteenth century moved upward, building elegant hillside mansions on the edge of town, overlooking the overcrowded slums below. This sharp difference in geographic elevation expressed in spatial terms the vast extremes of wealth and poverty generated by the city’s rapid commercial and industrial growth.[1]

In the nineteenth century, Le Havre was the primary seaport of Paris and France’s gateway to the world across the Atlantic. Its location near the capital at the mouth of the Seine and the gradual improvement of its port facilities since its founding by King François I in 1517 made Le Havre a premier point of transit for passengers, raw materials, and manufactured goods entering and leaving France. On the eve of the First World War, Le Havre was the second largest seaport in France (after Marseille) and the largest transatlantic port; between one-fourth and one-fifth of French maritime commerce passed through the Havrais docks each year. Le Havre’s importance as a port shaped every aspect of the city’s life: its major industries, including shipbuilding and metallurgy; the mercantile and financial elite, with commercial interests as far-flung as the sugar and cotton plantations of the New World, that dominated the city’s economy and politics throughout the nineteenth century; and its working population of sailors, dockworkers, and laborers, whose employment was not only grueling but unreliable, dependent on the caprices of weather and international markets.[2]

Like Paris, Le Havre experienced rapid and dramatic population growth during the mid-nineteenth century. A city of fewer than 27,000 inhabitants in 1823, it doubled in size by 1846; in 1881, Le Havre had grown to a population of 106,000; and in 1901, it exceeded 130,000—the ninth-largest city in France. Over the entire nineteenth century, only Roubaix and St.-Etienne among major French cities grew at a faster rate.[3] As in Paris, the sudden pressure exerted by this growth on the city’s physical and social structures caused considerable anxiety among political leaders. The concentration of so many people in the close quarters of the central city—especially working people confronting the contradictions of dire poverty in the midst of great mercantile and industrial wealth—gave a troubling immediacy to the prospect of disease and unrest; on the heels of two cholera epidemics and two revolutions in France during the 1830s and 1840s, few could ignore the threat posed by the nation’s increasingly pathological cities. A perceived penchant for drink and depravity among the “dangerous classes” only exacerbated the fears of local and national elites.

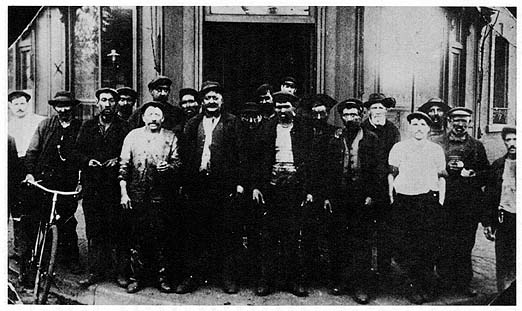

10. Coal handlers of Le Havre’s waterfront, ca. 1910. Photo courtesy of Jean Legoy, Le Havre.

In the case of Le Havre, a cadre of philanthropically minded public figures led by Jules Siegfried spearheaded a wave of reform initiatives in the city during the early Third Republic. Siegfried, who achieved a national reputation as a centrist republican legislator and cabinet minister, dominated politics in Le Havre during his tenure as mayor (1878–1886) and throughout his thirty-six years in parliament as deputy and senator (1886–1922). Personally or through his disciples and allies, Siegfried made his influence felt at City Hall, and in no domain was this influence stronger than in health policy and sanitary reform. The first municipal board of health in France[4]—Le Havre’s Bureau d’hygiène—was his creation in 1879, and he also became known nationally as a champion of colonialism and working-class housing.[5]

As early as the Second Empire, however, there were signs that a new awareness of hygienic matters in general, and the problem of tuberculosis in particular, was emerging in Le Havre. In the 1850s, Dr. Adolphe Lecadre began issuing periodic reports on the city’s “sanitary situation”; most of them were published in the bulletin of the Société havraise d’études diverses, the local société savante. In an 1868 report—just after Villemin’s efforts to prove the transmissibility of tuberculosis but well before both the establishment of the Bureau d’hygiène and Koch’s pivotal discovery of the tubercle bacillus—Lecadre foreshadowed several aspects of the later dominant etiology and War on Tuberculosis. Chief among these was the localizing impulse. Lecadre proposed to explain much of Le Havre’s mortality by breaking down death rates from certain causes street by street, according to the residence of the victims. First among the killers he included in the category of “local” or housing-related diseases was tuberculosis. Writing during the not-quite-contagionist interim between Villemin’s and Koch’s experiments, as the tide was beginning to turn against the likes of Pidoux and Peter, Lecadre asserted that tuberculosis was “transmitted by the effluvia inherent in housing.”[6] On its face, such a declaration seems straightforwardly miasmatist, but its use of the word transmitted and its focus on housing (rather than, for example, swamps or soil drainage) prefigure to some extent the key role played by unsanitary slums in the later, contagionist etiology of the disease.

It was neither obvious nor at random that Lecadre chose to analyze tuberculosis and other diseases locally, by ascribing them to certain buildings, streets, and neighborhoods. Several revealing phrases in his report show that this strategy was both conscious and clearly delineated. Certain causes of death were to be excluded from the analysis by quartier.

In other words, those diseases for which no known social or behavioral cause existed—Lecadre noted tuberculosis, infantile diarrhea, typhoid fever, and the measles as four that accounted for a significant number of deaths—would be broken down by street and neighborhood to find specifically local correlations. Other possible causal factors (such as work or diet, for example) failed to appear in the statistics, because Lecadre’s method excluded nongeographic variables. This predetermination of the conclusions in the approach was not uncommon in mid-nineteenth-century epidemiological studies. Unlike other aspects of social relations, housing was perceived as subject to—and in need of—remedial action.Some illnesses…are specific to certain ages.…Other diseases, such as those of the heart, are frequently caused by the exaltation of the passions, overwork, the depletion of physical strength, a dissolute lifestyle, etc., [and] cannot affect certain streets [differently].[7]

There were other hints as well in Lecadre’s early reports of what would later be the dominant etiology of tuberculosis. For example, in that same 1868 report, he noted that the disease frequently struck unmarried residents of lodging houses, who fit a certain social profile:

Here, in addition to housing, the rural exodus, domestic servants, and immorality are all associated with urban mortality from tuberculosis—much as they would be forty years later. Lecadre’s analysis was hardly as sustained or emphatic on these points as the dominant etiology would later be, but it shows that much of the official bourgeois reaction to tuberculosis, on the local as well as the national level, predated germ theory and derived more from social change than from strictly scientific developments.We see among these consumptives…a goodly number of sailors, [including] many outsiders[;] and at the top of this list must be placed the Bretons, who came to Le Havre seeking the work that their native land refused them[;] among the women [are] a large quantity of servants, mostly young girls, [who] left the countryside, where they were often quite healthy, to come lose their health in the insalubrity and laxness—and for some of them dissoluteness—of the city.[8]

In later reports throughout the 1870s, Lecadre continued to emphasize the pathogenic role of unsanitary housing, while at the same time elaborating on other causes of tuberculosis. By and large, these were the classic elements of pre-germ theory etiologies. Masturbation, sexual excesses, sedentary lifestyles and occupations, the exposure of wet or sweaty skin to sudden temperature changes, and various other environmental influences took their places alongside heredity in Lecadre’s catalog of predisposing factors. He equivocated on the contagion question (acknowledging spousal transmission in cramped domestic situations) and quibbled with those who accused alcoholism alone of causing tuberculosis, to the exclusion of other factors.[9] For the most part, however, in his steady stream of reports on Le Havre’s demographic and sanitary condition, Lecadre reinforced his contention that nothing was more continually and evidently associated with tuberculosis than poor housing.

This attitude exemplifies what Cottereau has called the “glissement écologique,” or ecological slide, which transfigures social relations into spatial relations.[11] Lecadre in effect attributes tuberculosis to “poverty,” but interprets poverty as a spatial or environmental rather than economic problem.Where do we see phthisis principally appearing? [I]n narrow streets, in cramped lodgings, in buildings where many large families are crowded together. The primary and principal cause of the frequency of phthisis is poverty[;] not the poverty that lacks bread but the kind that lingers in unsanitary lodgings, deprived of suitable air, ill-clothed, often wallowing in uncleanliness, suffering the terrible effects of overcrowding.[10]

More of a chronicler than an advocate, Lecadre offered in his reports few proposals—either individual or social—for remedying the deteriorating health situation in Le Havre. One especially revealing passage in an 1877 report highlights his view of the proper role of medicine and public health in society. Writing specifically about possible responses to the city’s growing tuberculosis problem, Lecadre uncharacteristically set forth an agenda.

Rather than urge strong governmental or philanthropic initiatives to “react against these excesses,” the doctor proposed a battle without intervention. The phrase “incessant observation” encapsulates Lecadre’s personal mission as well as his prescription for improving society. It was a prescription that would soon go a long way toward fulfillment with the establishment of the Bureau municipal d’hygiène in 1879.Because civilization, whose progress is so beneficial, has its excesses which often do real harm to society, let us react against these excesses, not only by example, but also by incessant observation and by constant studies of public and private hygiene.[12]

| • | • | • |

Remaking the Working Class: Housing, Health, and Moralization

Before examining the history of France’s first municipal board of health, in large part the creation of Jules Siegfried, it is worth considering some of Siegfried’s other reform efforts—in particular, the workers’ social club and sanitary low-cost housing—as part of his wider vision of a more orderly and healthier society. Historians have portrayed the Protestant legislator as the quintessential Third Republic notable, with his mercantile wealth, his power base in a local fief, and his political agenda of class rapprochement. An avatar of late-nineteenth-century liberalism, a “professional paternalist” in the words of Sanford Elwitt, Siegfried built his career on two axes: the expansion of French markets and influence through free trade and colonialism, and social harmony through the moralization and embourgeoisement of the poor. “To reconcile the working class through the union of capital and labor, without endangering the established social order, this was the task Jules Siegfried set for himself,” wrote the historian of Le Havre, Jean Legoy.[13]

In the France of the 1870s, the task was hardly a simple one. In the aftermath of the Paris Commune, the gulf separating the classes seemed to many an abyss. Mutual fear and contempt characterized each group’s perceptions of the other. In such a state of affairs, true reconciliation was unthinkable. All the items on Siegfried’s social agenda shared one basic aim: to remake the working class in the image of the bourgeoisie. Perhaps the archetypal reform in this spirit initiated by Siegfried was the workers’ social club, the Cercle Franklin.

The crux of the social question, Siegfried felt, was hard work. The harder one worked, the more money one made. If workers could be encouraged to grasp this basic truth, he insisted, all concerned would be better off, and the social question would peacefully disappear.

Such misguided souls played right into the hands of “vulgar agitators” with “subversive theories,” who “exploit[ed]” honest workers for their own purposes. The consummate liberal, Siegfried believed that only the free play of market forces could determine fair wage levels or the proper relationship between labor and capital. However, something could be done about the lifestyle and “habits” that caused workers to fall prey to subversion: in particular, la vie du cabaret, which robbed the poor of their money, their health, and their faculties of judgment and moderation. (Although it would not reach its apogee until the turn of the century, the “moral etiology” that implicated cabarets and alcoholism as causes of tuberculosis was already in evidence in Le Havre in the 1870s.) Siegfried agreed with most hygienists and moralists that the demoralizing and unhealthful life of the cabaret was only able to exercise its allure because of the dreary and insalubrious home life of the poor. Drinking and debauchery claimed so many disgruntled workers because after a long and tiring day of sometimes back-breaking labor, they simply could not bring themselves to face the filthy and “bien triste” quarters awaiting them at home. “Can we be astonished that, lacking the comfort that the wealthy can afford, they go out to find some distraction?” “Sirs,” Siegfried told a lecture audience in Le Havre in 1874, “the cabaret is the worker’s worst enemy.”[15]With orderly and economic habits, through regular work and rising wages, workers can satisfy their needs and those of their families. Unfortunately, while some cannot find regular work, others—more numerous—…lose themselves in the life of the cabaret; whereas, in order to achieve the welfare they desire, they should be applying themselves courageously to their work.[14]

The antidote could only be one that addressed the root cause luring customers to the cabaret. Siegfried called his strategy “moralization through distraction.”[16] He proposed a “cercle d’ouvriers,” modeled after the Workingmen’s Club of Manchester and an analogue in Mulhouse: a gathering place for workers of all occupations, where they could be entertained and enlightened while relaxing among their peers in a leisurely atmosphere. In Le Havre, the workers’ social club would be named after Benjamin Franklin, whom Siegfried admired as “a great American citizen, a friend of order and liberty as well as a partisan of hard work and education.”[17] In this, as in all of his writings and speeches, Siegfried’s Protestant background is very much in evidence; indeed, his entire social reform program cannot be understood without taking into account the crusading religious zeal that animated it. The bywords “order” and “work” are never far away in these texts from their companions “liberty,” “morality,” and “well-being.” Throughout the early Third Republic, Protestants were disproportionately represented among the ranks of French social reformers and philanthropic leaders.[18]

Le Havre’s bourgeoisie, of course, could afford the home life and diversions that preserved the individual from destructive and subversive ideas; the working class, much more vitally in need of such off-the-job distractions, could not. Siegfried set out to fight the paradox that only those least needful of this particular service could afford it. He argued that, in fact, not only was a cercle d’ouvriers in the workers’ best interests but it was also in the self-interest of the wealthy and powerful. In pleading with the latter to finance the establishment of the Cercle Franklin, Siegfried planted barely veiled hints in their minds about the consequences of shortsighted conservation of wealth.

All classes of society were joined together, Siegfried maintained, by ties of social solidarity. Bourgeois philanthropy, when directed toward projects such as the Cercle Franklin, amounted to self-preservation, particularly when one considered the alternative.It is right and legitimate to work to acquire a fortune; but…the error…is in believing that it can only benefit oneself. An error, sirs, which does not go unpunished; à père avare, fils prodigue, and slowly accumulated money, selfishly guarded, can disappear…with a rapidity that we all know.[19]

Idle (working-class) hands were the devil’s playground, and idle (bourgeois) money was an invitation to disaster. Simmering class resentment, which had erupted three years earlier in the Paris Commune, could be contained only through a farsighted program of charity, a remoralization of workers that transformed them into respectable, if low-income, facsimiles of the bourgeoisie. Here again, Protestant reforming zeal and moralism infuse Siegfried’s politics, along with class-based pragmatism. Attributing the absence of revolution in England to mutual respect among the classes and the prudent philanthropy of the wealthy, he cannot have left his audience in doubt as to the import of his warning.[21]To do good for others is not only an act of charity but also an act of intelligence, because it does good for oneself. To understand this…is the real way to hold at bay that great cause of ruin for our country, that peril that constantly threatens us[:] Revolution.[20]

Such frank pleas for contributions show Siegfried to have been remarkably open about his political and philanthropic strategy; he also seems to have been adept at selling his plan. The Cercle Franklin was built in 1875 and officially opened its doors in January 1876. The new facility offered lectures, concerts, and a library for its members, along with recreational activities such as gymnastics, fencing, and billiards. The initial response was enthusiastic: more than two thousand Havrais joined the club in its first year of operation. However, its popularity soon waned—no doubt thanks, in part, to the annual membership fee of five francs, more than a day’s wages for some workers—and less than ten years later, in 1885, the Cercle Franklin was all but defunct.[22]

If Siegfried and his fellow reformers in Le Havre were discouraged by occasional setbacks and signs of failure, they showed no signs of it. The workers’ social club was neither the only nor even the most ambitious of their projects during the early Third Republic aimed at improving the health and morals of the city’s poor. The possibility of building sanitary, low-cost workers’ housing on a large scale preoccupied Siegfried throughout his career, and he saw in it a chance both to root out the material causes of disease and to remove the crucial first step on the slippery slope that led workers to the cabaret, depravity, and death.

The history of official concern over the deplorable state of working-class housing in Le Havre begins in earnest as far back as the 1840s and 1850s, when the city’s population first showed signs of imploding. When thousands of poor migrants from Normandy and Brittany came to the port city seeking work and lodgings, even the demolition of the fortifications surrounding the old city and the annexation of several adjacent communes could not accommodate the new arrivals. Merchants such as Siegfried, reaping vast profits from the rapidly growing commerce of the port, built mansions on the hillsides overlooking the old town, and even the less opulent houses being constructed in outlying neighborhoods were far beyond the means of most Havrais workers. As a result, the decrepit apartments and boardinghouses of the center city—in particular, the Notre-Dame and Saint-François quarters adjoining the old port—simply became more and more crowded.[23]

Following the national law of 1850 on housing sanitation (Le Havre was, after all, not the only city experiencing such problems), the Commission on Unsanitary Housing (Commission des logements insalubres) convened in the city in 1851. The commission investigated complaints and reports of particularly egregious sanitary negligence on the part of landlords; it requested compliance when it found repairs or improvements needed, and it had the power to refer cases of recalcitrant propriétaires to the city council and to the courts. Most often, the commission compiled exhaustive and detailed reports but preferred a strategy of coaxing landlords into repairs (however piecemeal) to pursuing legal action against them.[24]

Nevertheless, the commission’s reports provide unique access to official perceptions of the laboring poor and their daily lives. The dominant tone of this narrative genre—little changed around the turn of the century from what it had been forty years before—is one of shocked disgust. For example, in a typical report from an 1893 visit to a building on the rue du Grand-Croissant in the Saint-François quarter, the commission’s members found a house “unfit to house even animals.” On the ground floor, a partially enclosed toilet opened onto the open door of a butcher’s shop; a side of meat hung above the entrance “as if to receive the emanating scents of the facilities.” On the fourth floor, they found a courteous woman in a quite clean apartment, who showed them the steady trickles of urine that ran down the wall next to her bed, filling the apartment with “a persistently acrid odor.” They came from an overflowing toilet one story above, and when the commissioners investigated those units, under the rafters, they were overcome. “Here, we must give up trying to depict the appearance of these sordid places” (Ici, nous renonçons à dépeindre l’aspect de ces lieux sordides).[25] Such rhetorically dramatic expressions of outraged reticence were commonplace in nineteenth-century hygienic and moralistic reform literature; often, as in this case, they were belied by the detailed descriptions of the offending circumstances that followed. Although such protestations most often alluded to sexual improprieties or to the proximity of near-naked bodies,[26] here the locution seems to have referred principally to excretory functions, as it was surrounded by descriptions of filthy latrines and other more makeshift evacuation systems.

In this example as elsewhere, the housing commission’s reports struggle to make sense of a kind of subspecies living in their midst, a mystifying and somewhat threatening “Other,” wallowing in quarters not fit for animals and yet seemingly indifferent to their plight. Both the threat and the indifference are highlighted in another report from the same year, after a visit to a building on the rue d’Albanie in the Notre-Dame quarter. Again the commissioners’ attention was drawn to the toilet facilities, or lack thereof. They burst out laughing when they opened the door of the water closet on the fourth floor, exclaiming “Oh, how necessity is the mother of invention!” There on the floor, in the place of a latrine, was a common metal household storage box, “voluminously full!” A commission member asked one of the tenants why there was no seat and no proper latrine.

They asked her if the rent was expensive. “Oh yes, sir,” she answered, “very expensive: 160 francs per year.” When they asked if all of the tenants paid the rent regularly, the woman’s tone turned incredulous. “Oh, of course not, we would have to be stupid to pay rents like those. The landlady comes around demanding her money, but everyone tells her the same thing. She goes ahead and tells us to leave, but nobody moves.” The commission’s response to this colloquy is extremely instructive.“A seat?” She seemed not to understand, as if we were speaking of a luxury unknown to her. There had never been one. As for the latrine, she told us, it had been taken away, a few days earlier, because it was full, and had never been returned.[27]

It is jarring to find the commissioners, at times so compassionate and solicitous of the needs of Le Havre’s poor, pronouncing such a harsh judgment on the buildings’ inhabitants: that they lived in squalor because they wanted to, that they should be willing to pay if they wanted anything better. These comments make sense only if one takes at face value the qualification of the residents as “a race apart.” In and of themselves, such creatures may not have been worthy of official concern or even pity; but given the threat of contagion—the possibility that the unspeakable pathologies bred in such conditions could spread outward, threatening even respectable citizens—remedial action was imperative.With this answer, we left, taking with us the following moral: the people that live in these hovels…belong to a race apart: Like all others, they avidly desire material comforts, as long as they can enjoy them for free. They are told to leave, because they don’t pay; but they prefer to stay. Therefore, they must be happy there.

However, here we have a question of public health and the public interest. We cannot tolerate in the middle of the city such hotbeds of infection.[28]

Many reformers, including Siegfried, were not content to let the Commission des logements insalubres investigate cases of reported negligence or insalubrity. Only an entirely new environment could remake the material and moral life of the worker.[29] Vital to Siegfried’s efforts to build hygienic cités ouvrières was working-class ownership of the new homes.

The enemy again was revolution; along with a bourgeois morality, property ownership—an economic interest, however slight, in the status quo—was seen as a means to the desired end. Built simply but attractively according to the laws of hygiene, the cités ouvrières would marry aesthetic and sanitary virtues with this economic interest, creating a pleasant place to spend one’s leisure hours and eliminating the deadly temptation of the cabaret.The worker who hopes to become a homeowner devotes all of his attention to his house; he develops an interest in his domestic life,…abandons the cabaret, and becomes a veritable conservative.…Do we want to combat poverty and the errors of socialism at the same time? Do we want to augment the guarantees of order, of morality, and of political and social moderation? Then let us create cités ouvrières![30]

In light of later reformers’ preoccupation with fighting socialism, it is ironic that in the early days of the Second Empire, the first initiative toward the construction of a cité ouvrière in Le Havre was itself socialist in inspiration. Several local followers of the utopian socialist Charles Fourier, eager to apply some aspects of the philosopher’s hypothetical “phalanstery” (a community whose residents live and work together in harmony according to their individual and collective desires), brought forth a detailed proposal in 1852. The plan, for which land had already been set aside in the Leure quarter on the eastern edge of the port, would have provided fifty-two new housing units in five two-story buildings, with spacious gardens, ample sunlight, and sanitary facilities that would have satisfied even the most fastidious housing commissioner. However, despite the repeated urgings of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (both as president and later as emperor) for the realization of just such housing projects, the prefect of the Seine-Inférieure rejected the proposal on the grounds that its authors had not provided enough information on how the project would be financed.[31]

After the abortive Fourierist plan, it was not until 1870 that another working-class housing project was launched in Le Havre; this time, it had the backing of Siegfried and other prominent members of the city’s merchant elite. Together, they contributed 200,000 francs as start-up capital for the Société havraise des cités ouvrières, which in late 1870 began construction of its first group of seventy-seven houses, collectively known as the Cité havraise, in a relatively sparsely populated area in the northeastern part of the city. In 1884, the society added another group of forty houses, the Cité Desmallières, several blocks to the east, near the city limits separating Le Havre from the commune of Graville. All these units, though small, were actual houses in the “pavillion style,” separated from each other, with courtyards and gardens. In contrast, the eighty-two housing units provided between 1899 and 1906 by the Société havraise des logements économiques (a group unaffiliated with Siegfried’s society) consisted of six separate pavillons and one four-story building containing seventy apartments. Little is known about this second organization or the housing it provided; in any case, it did not meet the strict definition of a cité ouvrière, because its units were for rental only, with no possibility of eventual ownership by the tenants.[32]

This idea, of course, lay at the core of Siegfried’s vision for workers’ housing: ownership. Residents paid a monthly redevance—considerably higher than rents for similar lodgings elsewhere in the city—that was credited toward the ultimate purchase of the house. The entire sum would have to be amortized within a period of twenty years; as it turned out, few made it that far. In both the Cité havraise and the Cité Desmallières, the tenancy of at least half the units turned over within the first ten years of operation. Fewer than a third of the would-be home owners made it to twenty years and actual ownership. Moreover, there is no indication that tenants earned any kind of equity with their payments, equity that they might have been able to apply to the purchase of another house if they left the cité before the twenty-year amortization.[33]

In that respect as well as others, the reality of the cités fell short of the reformers’ aspirations. Despite the seeming urgency of public health considerations in the workers’ housing enterprise, there were no provisions in the Cité havraise for either water supply or for waste disposal (it was not connected to the city’s still-limited network of sewers), and the sand used in the construction materials retained moisture and kept the houses somewhat dank. The first residents of the cité were forced to use the woodsheds in back of their houses for toilets. Such glaring oversights, coupled with the units’ high turnover, can only have thwarted to a great extent the lofty goals of Siegfried’s meliorist paternalism.[34]

This is not to say, however, that extravagant claims were not made on behalf of the cités ouvrières, particularly where health was concerned. During the key years when the long-term and large-scale success or failure of the concept was at stake, its proponents mustered impressive statistics in its defense. An 1884 report to the Société havraise d’études diverses enthusiastically touted the benefits of workers’ housing projects, based on fifty years’ experience in London. There, overall mortality in the philanthropic housing projects amounted to less than a third of the rate for the city as a whole. Tuberculosis mortality in the London projects was reported to be about half as high as the citywide level.[35] Similarly, in 1885, a prominent physician in Le Havre proclaimed the 117 houses in the Cité havraise and the Cité Desmallières “almost entirely free” of tuberculosis, thanks to “the excellent hygienic conditions” of the homes. Six years later, the same doctor gave more precise figures in a newspaper report, attributing to the cités just 1 tuberculosis death per thousand inhabitants per year, compared to 6.3 in the Notre-Dame quarter. The newspaper concluded, in a ringing endorsement of the workers’ housing strategy, that the number of deaths from tuberculosis in Le Havre annually could be cut almost in half if the city had proportionally as many cités ouvrières as London.[36] For a city with the highest tuberculosis mortality per capita in all of France (and likely in all of Europe), a 50 percent reduction would have been a monumental achievement. Even allowing for hyperbole and statistical exaggeration, such enthusiasm in the press and in the medical community suggests at the very least that (1) improved housing was widely seen as an effective remedy against the scourge of tuberculosis, and (2) the cités ouvrières enjoyed significant public support.

That support was not unanimous, however, and expressions of skepticism occasionally clouded the otherwise rosy light in which the workers’ housing projects were publicly portrayed. In the first place, many taxpayers objected to the original investors in the projects being guaranteed a certain rate of return on their investment. This appears to have been a fairly common feature of such societies’ charters, a concession by the city to those who put up the capital for construction—much like a tax break to encourage certain investments deemed socially useful. However, it did not sit well with some observers, who wondered what right the wealthiest négociants in Le Havre had to an automatic claim on the public treasury, particularly if their motives were strictly charitable.[37] In these matters, the line between “philanthropist” and “investor” was a thin one.

The lengths to which reformers urged the state to go in making cités ouvrières financially attractive to prospective tenant/owners also raised some hackles. A letter to the editor in the newspaper Le Courrier du Havre in 1893 denounced the bloated bureaucracy and unfair favoritism that would likely result from Siegfried’s low-cost housing bill, then under consideration by parliament in Paris. The angry correspondent painted the proposed law as positively unpatriotic.

Suppose they both wanted to settle down with their families and become home owners, the letter continued. One chose a “Siegfried house”; the other, “more independent,” built his own house. Under the new bill, the first would be exempt from all taxes for twelve years and would enjoy other benefits as well. “For him, the cité in question will mean the easy life, a chicken in the pot just like under Henry IV.” The other home owner would have to pay not only his own share of taxes but enough to make up for his “privileged” counterpart’s exemption on top of it. “No! no!” the author fulminated, “[s]uch a law is impossible in a country like ours.”[39] While it is conceivable that this letter to the editor was simply the work of a disgruntled landlord fearing subsidized competition, it nonetheless shows the extent to which the cités ouvrières were seen as intended only for a select stratum of the working class and sanitary housing in general as a “privilege” rather than a right or a social necessity.Let us take from the well-off class of workers—because the bill applies only to this group—let us take two young men returning from their military service, having just acquitted an equal debt to their patrie. Are they not entitled to be treated by their country on an equal footing? They should be; but if the Siegfried law passes, they will not be.[38]

Others attacked the shortsightedness of housing improvements per se, for failing to take into account the fate of those displaced who could not afford the “improved” lodgings. (Although this criticism does not apply to all cités ouvrières, as they were not always built on the sites of older housing units, it does highlight the perceived tendency in social reform to provide for workers of relatively greater means while ignoring the most needy.) In 1884, residents of the notoriously unsanitary Saint-François quarter demanded that a square then being cleared in front of the Saint-François church be extended through the entire facing block of houses, to bring needed light and air to their neighborhood. A journalist named Lécureur with the newspaper Le Havre reported the residents’ demand but asked what would happen to those who lived, however miserably, in those buildings. “Nothing is more laudable,” Lécureur allowed, “than to rescue people from death [by] remov[ing] them from the harmful influence of a milieu where disease, especially the horrible phthisie.…, has taken up permanent residence.” Strictly speaking, there was not a shortage of housing in Le Havre, he argued, but the displaced could not afford the sanitary lodgings that were available. He told of receiving complaints from former residents of several streets in the old neighborhoods of the center city, whose modest apartments were demolished when the streets were widened for hygienic purposes.

Lécureur acknowledged that the question was a “delicate” one, but he maintained that if such “improvements” continued, without regard to the “expulsés,” there were only three possible outcomes, all of which would be “absolutely disastrous” for Le Havre: the displaced workers and their families would have to either move outside the city limits, take up residence in the newly constructed buildings with no intention of paying the higher rents, or leave the area entirely because it had become “uninhabitable.”[41] Once again, other interests may have been at stake in this critique, but it at least raised the question of whether such measures constituted true “progress,” a question that had no place in the unshakably positivist worldview of Siegfried and his fellow reformers.Unable to come up with the money needed [to stay in the area], they were forced to take refuge in [the] Le Perrey [quarter], in appalling little nooks a thousand times more insalubrious even than the poor apartments from which they had been expelled.…[O]ne has the right to ask if this is real progress, and for whom[?][40]

Philosophical doubts aside, perhaps the most damning criticism of the low-cost housing movement held that its claims of success in fighting disease and depravity were skewed by a rigorous screening process. An anonymous letter to the editor of Le Havre’s Petit Républicain in 1891 leveled that charge in a searing, cynical diatribe against the cités ouvrières. Amid the familiar litany of complaints about heavy tax burdens and “the shackles of bureaucracy,” the author questioned whether housing actually played as great a role in public health as was generally believed. “Housing is not everything,” he wrote. Meager diets and overwork contributed heavily to the poor health of the working class, a fact that was hidden by the statistics coming out of the new housing projects.

The society demanded of all prospective tenants, the author alleged, “guarantees of order, morality, good health, etc.” Such demands, he added, would have been viewed as preposterous coming from an individual private landlord.In the cités ouvrières, they tell us, mortality rates are extremely low! But of course; they are just like the mutual aid societies: not everyone who wants in is allowed in! A serious investigation always takes place first.[42]

The same triage kept out anyone of questionable “moral condition,” he further contended, thereby preserving the image of the cités ouvrières as wholesome communities of happy families.[44] While it is impossible to either verify or disprove these allegations, the mere fact that they were made publicly, in the pages of a newspaper—even allowing for exaggerations—suggests that the glowing reports of the projects’ success should be taken at less than face value. Even if the selection process did not work in this elaborate manner, with its hints of espionage, the steep redevances required of residents acted as a de facto triage, excluding the majority of Havrais workers who could scarcely pay their rent, much less a considerably higher monthly mortgage payment.A serious selection process, a careful triage, appropriate means of collecting information: what better way of keeping out the disease-ridden poor! What better way of obtaining statistical results proving that so few people die in the philanthropic cités! Parbleu![43]

In its response to the perceived role of slum housing in the spread of disease, Le Havre was different from Paris and other French cities in one crucial respect: its civic leaders attempted from a very early date and in a sustained manner to create a new and better housing stock. In contrast to a strategy of administrative surveillance and record keeping, there was an effort in Le Havre to alter the situation on the ground. The city, behind the impetus of Siegfried, was a national pioneer in this domain. However, the new housing never materialized on as large a scale as its leaders had hoped. Even double the 117 houses built by Siegfried’s society could not have made more than a small dent in the public health crisis of a city of 130,000 people. Furthermore, it is clear that moral concerns played as great a role in the city’s housing reform programs as sanitary ones, although the social reformers of the time might not have recognized any difference between the two. The strategy of surveillance was also very much in evidence—yet another area in which Le Havre was a trailblazing city.

| • | • | • |

Knowing the City: The Bureau d’Hygìene

Perhaps the most long-lasting and widely imitated of Siegfried’s social reforms was the Bureau d’hygiène, France’s first municipal health department, created in 1879. After 1902, every French city of more than twenty thousand inhabitants was required by law to establish a health bureau modeled on that of Le Havre; its pathbreaking work earned it national and international acclaim among doctors, hygienists, and politicians. As a precursor and, later, outpost of the War on Tuberculosis, the Bureau d’hygiène attempted to translate the medical and hygienic knowledge of the dominant etiology into local knowledge and to track the disease administratively through the city and through the years.

Along with Siegfried, the person most responsible for the establishment of the Bureau d’hygiène was Joseph Gibert, a Swiss-born physician who settled in Le Havre after attending medical school in Paris. Gibert is known to some historians of France as a principled convert to the cause of revisionism in the Dreyfus case; the doctor interceded with his friend and fellow Havrais Félix Faure, president of the republic, and was shocked and dismayed when Faure admitted that Dreyfus had been convicted based on secret “evidence” but invoked raison d’état in refusing to reopen the case.[45] But Gibert spent most of his career, outside of his private practice, seeking ways to improve the desperate sanitary situation of his adopted city. In 1878, the first year of Siegfried’s tenure as mayor of Le Havre, the two friends first put the idea of a municipal health department before the city council, on which Gibert also served. The doctor spoke eloquently about the need to preserve the country’s human resources, a need that was especially acute in light of the country’s demographic and political decline as a world power. “If we are not first [among nations] in the production of human life”—a reference to the country’s falling birthrate—“let us strive to be first in the saving and husbanding of this incomparable treasure, and preserve it, through a practical and serious organization of public hygiene, from the scourges that constantly threaten it.” Gibert told the council members that the nation would applaud Le Havre’s initiative “if every year more healthy and robust defenders are saved for its battalions, more hands are saved for its workshops, [and] more young girls are prepared by a salutary education for their role as mothers.”[46] From the very beginning, then, concerns over national decline, military might, productivity, and parenthood conditioned the fight against tuberculosis and other causes of death, on the local as well as the national level.

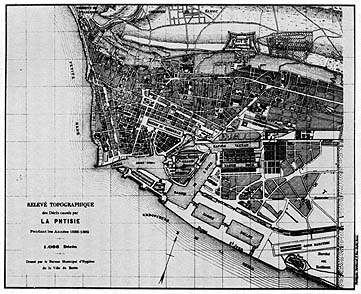

Although several members of the city council suggested modifications to Gibert’s and Siegfried’s proposal to reduce its cost, the only real opposition to the plan came from Louis Brindeau. (Twenty-four years later, as mayor, Brindeau would praise the bureau and its work in glowing terms.) The councilman objected that the creation of a new city department would entail excessive expenses. Mayor Siegfried intervened to suggest to the council some specific benefits the bureau would bring. It would monitor, he said, the day-to-day sanitary topography of the city. “Thanks to the reports of the Bureau d’hygiène, it will be possible to compile a synoptic map of the progress and intensity of diseases in [our] neighborhoods.” Gibert concurred that only through detailed knowledge, by mapping the incidence of diseases such as tuberculosis in the city’s streets and neighborhoods, could science determine their true causes. Brindeau insisted that “to create a special office of hygiene is to spend a great deal [of money]…for statistical information.” He suggested instead that the same amount of money be spent on sewers, public baths, and other material sanitary improvements, while existing commissions and departments could compile all necessary statistics without the additional expense.[47]

Brindeau could not stem the positivist tide, however, and the reformers’ arguments regarding the need to collect more comprehensive and systematic information won the day. Le Havre inaugurated its new Bureau d’hygiène in 1879 and began an era of exactly what Lecadre had called for: “incessant observation.” The bureau was given authority and responsibility over all health-related matters, and its day-to-day functions included maintaining France’s first casier sanitaire, a record of the place, time, and cause of every death in the city, as well as keeping track of births; disinfecting the lodgings and personal effects of victims of contagious diseases (including tuberculosis); inspecting samples of foods and beverages for quality; administering smallpox vaccinations; following up complaints concerning various causes of insalubrity; inspecting schools, other public facilities, and industrial establishments; and surveillance of registered prostitutes for venereal diseases.[48]

Right from the start, the bureau was forced to come to grips with tuberculosis, the city’s leading killer. During the 1880s, its periodic reports gradually elaborated all three elements of what would later become the dominant etiology of the disease (contagion, housing, and immorality), while at the same time the major French medical journals and the professors at the Paris faculté were only taking the first tentative steps toward the same ultimate conclusion. The bureau’s very first report, on its operations in the first three months of 1880, placed great emphasis on tuberculosis, pointing out that no epidemic or any other cause ever approached it in the number of deaths it accounted for. This early report, marking a sober realization of the difficult tasks facing the bureau, singled out two particularly pernicious causes of tuberculosis. Though it mentioned heredity, contagion (two years before Koch), poor nutrition, and lack of ventilation as contributory factors, the report denounced above all “venereal excesses among adolescents and alcoholic excesses,” often found doing their damage together in the same person. Four years later, in 1884, the bureau’s director, Dr. A. Launay, lamented in a brief passage on tuberculosis that “alcoholism continues its ravages” and otherwise shed no new light on the matter.[49] In Le Havre, one of the most “alcoholic” cities in France,[50] the moral etiology of tuberculosis took hold quite early.

By 1887, five years after Koch’s discovery of the tubercle bacillus, as most of the medical profession was slowly being won over to the contagionist perspective on tuberculosis, the view from Le Havre had further evolved in the direction of what would become the dominant etiology. Doctor Gibert, in summarizing the epidemiological evidence gathered by the Bureau d’hygiène, cast the decades-old concern over slums and overcrowding in the new light of contagion. “There is a constant relationship,” he wrote, “between…population density and pulmonary phthisis.” To illustrate his point, he compared the figure of 1 tuberculosis death per thousand population in the cités ouvrières to 5 per thousand in Notre-Dame and Saint-François. (Reformers preferred this particular comparison to strict neighborhood-to-neighborhood ratios, because it purported to encompass socially identical populations in different environments.) While allowing that “we must admit the influence of contagion,” which had been scientifically proven, Gibert could not yet bring himself to abandon completely some older miasmatist notions, as in this equivocal statement: “Overcrowding, whose importance is so great in Le Havre, acts no doubt through the vitiation of the air, but also…through contagion.” The moral etiology, too, had progressed in terms of sophistication and statistical certainty; here Gibert contended that “alcoholism, by weakening the individual who indulges in it, prepares the way for contagion, and this can explain the enormous number of consumptives in Le Havre.” It was not until roughly ten years later that this formulation became the widely accepted dogma of official French medicine. Interestingly, this 1887 report is one of the extremely rare official documents from Le Havre to actually make reference to the city’s standing as tuberculosis capital of France and probably all of Europe. In partial explanation of that status, Gibert also claimed that Le Havre “appears to be the European city where the most alcoholic beverages are consumed.” For the most part, local officials preferred not to call attention to the city’s unenviable standing, while still insisting on the need for public health reform.[51]

Ten years after the bureau’s creation, the new etiology of tuberculosis had taken hold in Le Havre, and the local manifestations of contact with bacilli, substandard housing, and immoderation assumed preeminent importance in the bureau’s reports. The degree of emphasis accorded to any individual factor varied with local circumstances; for example, in 1890, the bureau’s advisory committee made the bold claim that the true causes of tuberculosis were only known (and knowable) thanks to the establishment of the bureau itself. “Nobody knew, before the creation of the bureau, what its topographical distribution was. Today…it is easy to know the true causes of its propagation.” The meticulous mapping of every death from tuberculosis revealed that its primary cause was overcrowding (which facilitated contagion), since mortality was highest in the most densely populated districts of the city. When commenting on the sexual distribution of the disease, the bureau invoked alcoholism to explain the significantly higher incidence among men than among women.[52]

Several points that went unacknowledged throughout the history of the bureau’s work on tuberculosis should be addressed here. The advisory committee’s assertion notwithstanding, observers such as Lecadre had linked the disease to overcrowding and housing conditions long before the creation of the Bureau d’hygiène, although without framing the issue in the language of contagion. Moreover, by deciding to investigate tuberculosis geographically, that is, by using the casier sanitaire data to represent its incidence spatially through the streets and neighborhoods of the city, the bureau predetermined the outcome of its inquiries. Had similar records been kept regarding differential tuberculosis mortality by occupation, wage level, place of birth, or any other variable, different conclusions certainly would have been reached. However, given the novelty of Le Havre’s Bureau d’hygiène, even in 1890 the advisory committee may have felt the need to justify its continued existence and rightful place in the municipal administration. It had to claim that important progress was being made, if not in material changes at street level, then in the realm of local knowledge.

Similar claims of progress continued into the 1890s and beyond, despite occasional administrative difficulties and Le Havre’s persistently high death rate from tuberculosis. A shortage of office staff forced the bureau to suspend the maintenance of the casier sanitaire in 1893; it was not until mid-1901 that temporary outside assistance brought the records fully up to date, whereupon they lapsed again for at least nine more years.[53] “Little by little, we are making progress,” Gibert reported in 1897, “but it is still not enough.” Other officials shared his optimism but not his caution; shortly after taking office in 1908, with Le Havre still ranking consistently at or near the top among French cities in both tuberculosis mortality and overall mortality, Mayor Henri Genestal confidently proclaimed, “The state of public health in our city is excellent.”[54]

Throughout its early years, the Bureau d’hygiène attempted to preach the antituberculosis gospel of prudence and cleanliness to the population of Le Havre. Its functions included supervising the municipal disinfection service, a service for which the bureau constantly strove to incite demand. Gibert was “pleased to report” to the advisory committee in 1896 that “the population is taking up the habit of having their lodgings disinfected after deaths from pulmonary tuberculosis.” He urged his fellow doctors to encourage this practice further, until the time when all tuberculosis deaths would be followed by disinfection as a matter of course. At the same meeting, other members of the committee pursued Gibert’s line of reasoning and called for mandatory declaration of all diagnosed cases of tuberculosis. Declaration to local authorities was already required by law for several other contagious diseases and would have facilitated universal disinfection. While one doctor called for mandatory declaration along with the isolation of tuberculosis cases within hospitals and the distribution of spittoons and anticontagion instructions to all those afflicted with the disease, another committee member demurred. Any measure that singled out tuberculosis victims, he argued, would rob them of hope. Many patients who showed signs of the disease had been carefully shielded from that fact by their physicians, and so strong was the popular association of tuberculosis with despair and death that to reveal the truth would shatter their illusions of possible recovery and a normal life.[55] These were precisely the same dilemmas and controversies that the entire French medical profession was facing—although the critical mass of activist doctors and social reformers in Le Havre seems to have caused the issues to appear there several years earlier than elsewhere in France—and despite the energy and money spent, the Havrais came up with no unique or original practical solutions to the problem of tuberculosis. In the domains of administrative surveillance and statistical knowledge of the disease, however, as in mortality, Le Havre far outdistanced all other French cities and the central government as well.

The health department’s crowning achievements in this regard were its two published decennial reports, the first covering the 1880s (published in 1893) and the second the 1890s (published in 1903). Prosaically entitled Relevé général de la statistique démographique et médicale, each was a prodigious accomplishment, an encyclopedic monument to the statistical quadrillage of a city and its population. For example, each volume contained detailed foldout maps of Le Havre; each map was marked with a pattern of dots, each dot representing a death from tuberculosis, for the years covered in that volume. (See fig. 11.) Together, the maps testify not only to the bureau’s thoroughness in collecting data but also to its leaders’ passionate commitment to medical topography as a means of fighting disease. Such maps of disease incidence, also known as “spot maps” or “dot maps,” were not new in the 1880s. Epidemics of yellow fever and cholera had previously given rise to case mapping in various British and American cities. But Le Havre’s tuberculosis maps of the late nineteenth century signaled a shift in the object of mapping from the exotic, exogenous, and epidemic to the familiar and endemic.[56]

11. Spot map showing deaths from tuberculosis in Le Havre, 1888-1889. From Relevé général de la statistique démographique et médicale, 1880-1889.

Mayor Brindeau wrote the preface to the first decennial report in 1893. As a city councilman fourteen years before, Brindeau had been the lone voice in opposition to the establishment of the Bureau d’hygiène. In his lengthy preface, he recalled that the proposal had “encountered a fairly intense opposition.” “Some keen minds contested the usefulness of an institution whose organization, costly as it was, would only produce…statistics which were quite interesting from a scientific point of view, to be sure, but would bring no practical result.” Without ever admitting that these were precisely his own objections (or that he was the only member of the city council to voice them at the time), Brindeau suggested that the experience of fourteen years had shown them to be well intentioned but unjustified. The wisdom and diplomacy of the bureau’s collaborators, he wrote, had succeeded in convincing private interests—here he was presumably referring to the proprietors of factories and plants classified as unsanitary establishments—to conform their practices to the principles of public hygiene, even though the bureau lacked the legal authority to enforce its policies. Brindeau further pointed to a two-thirds decline in diphtheria deaths since the bureau began its disinfection service in 1885 as evidence that the office had had a positive practical impact. Yet notwithstanding his earlier skepticism regarding the utility of statistics, even Brindeau had to admit that the bureau’s statistical work, as summarized in the decennial volume, was the pride of its brief history. In approving the publication of the volume, he pointed out, the city council had agreed to use it as the basis for considering sanitary improvements. “We can therefore say that the cleaning up of Le Havre will be the practical conclusion, so to speak,” of the bureau’s massive statistical compilations.[57] This was the great and largely unfulfilled promise of the Bureau d’hygiène. In the end, even the most sophisticated statistics could not raise money, expropriate a slumlord, or house and feed a day laborer and his family.

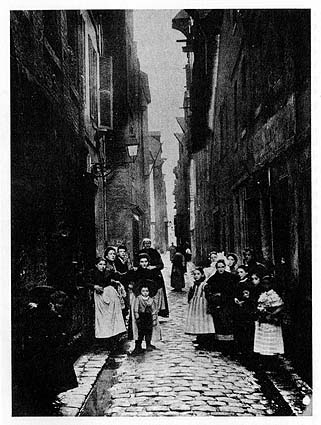

12. Rue du Petit Croissant, a street that perennially accounted for many tuberculosis deaths in Le Havre, ca. 1900. Photo courtesy of Jean Legoy, Le Havre.

As far as tuberculosis was concerned, the body of the two decennial reports was concerned with elaborating the street-by-street, house-by-house understanding of the disease, in which all components of the dominant etiology took their place. In the chapter of the 1880–1889 volume entitled Mortality by Street, recognizing that poverty, poor housing, and disease often went hand in hand, Doctor A. Lausiès questioned the true role of poverty in determining mortality. “If poverty [la misère] means a shortage of the material things in life and entails a lowered resistance to causes of death, it is difficult to appreciate the part played by those too-often concomitant phenomena, ignorance and vice.” To untangle the web of factors, Lausiès called attention to the seven streets at the top of the mortality list.

The tragedy of poverty seems to have been altered in its moral status, in the view of Lausiès, when ignorance and vice were also present, as in the rue des Boucheries. “More than anywhere, it seems that the residents, deprived of air, sunlight, and cleanliness in this narrow street, wallow in their misery and abandon themselves with a kind of fatalism to the inability of ever getting out.”[59] In other words, Lausiès hinted, economic poverty is one thing; but the moral defects of the rue des Boucheries population made them truly different, much as the unsanitary housing commission perceived some slum dwellers as a race apart.Without a doubt, poverty is extreme in all of them, but they suggest some quite different [nuances]. The rue de la Vallée is full of Bretons, poor for the most part, whose passion for alcohol is well known; the rue d’Albanie has never evoked images of a comfortable life; as for the rue des Boucheries, it brings together all the causes of insalubrity. The social milieu is perhaps poorer there than anywhere else, and ignorance plays a role there along with alcohol.[58]

Elsewhere in the 1880–1889 report, Doctor Gibert stressed a different theme within the dominant etiology, momentarily downplaying specifically local factors. “What dominates the entire question of phthisis, in Le Havre as in London and Paris and in all human agglomerations, is contagion and nothing but contagion.” Gibert called for a single “social remedy” to combat contagion and eliminate tuberculosis: housing reform. The cités ouvrières should be multiplied, he wrote, and spacious, well-built workers’ apartments should be constructed on the outskirts of the city, so that “air could circulate freely, and so that contagion from house to house could be avoided.”[60] In this one volume, then, in 1893, a fully elaborated version of the dominant etiology was put forward in Le Havre, well before its diverse elements were assembled in coherent form elsewhere.

By the time the second decennial report (covering the years 1890–1899) was published in 1903, there appears to have been a subtle shift in the attitudes of the city government and the Bureau d’hygiène toward health and mortality. In his preface, Mayor Marais struck a defensive posture from the start. “The city of Le Havre has never been unhealthy [and] is making progress in terms of salubrity, [while] new improvements must be pursued and will be obtained.” Marais obviously felt the need to contradict a certain perception of his city, whether through specific criticisms from the outside or simply a general image of Le Havre as diseased and unclean. In his discussion of the bureau’s statistics, he proudly noted a decline in overall mortality from the 1880s to the 1890s of 30.9 to 29.7 per thousand per year.

The claim that Le Havre’s high mortality was due in large part to nonresidents who transited through the port or otherwise found themselves in the city when they died (of illnesses contracted elsewhere) dates back at least as far as the reports of Adolphe Lecadre; however, it came to be asserted with greater frequency and insistence in the first decade of the twentieth century.A proportion still too great, certainly, whose significance must be attenuated to some extent by the contribution of the transient population [le contingent fourni par la population flottante], but which justifies in any case our continuous search for improvement.[61]

Later in the same volume, the bureau’s director, Dr. Henri Pottevin, sought further explanations for Le Havre’s death rate—from tuberculosis in particular—that might absolve the city’s health policy of blame, or at least mitigate its responsibility. Other cities such as Paris “exported” their tuberculosis patients, Pottevin contended, either to the suburbs or to family members in the provinces. Because these former Parisians died outside the city limits, their deaths were not included in the capital’s statistics, thereby artificially depressing its mortality figures. In contrast, “Le Havre keeps all of its tuberculeux,” Pottevin explained, “and therein lies one of the primary causes of our [high] tuberculosis mortality.” He pointed to “the predominance of the poor element” in the city’s population as an additional reason for the misleadingly high statistics, along with the fact that most Havrais were of Norman or Breton origin. Since nationwide, these were “the French races most heavily afflicted” with tuberculosis, Le Havre’s high rate was understandable.[62]

All of these protestations seem intended to explain away or make excuses for the city’s continually high mortality figures. They are also part of a broader pattern that goes beyond the interpretation of statistics. Local officials consistently downplayed both the role of material well-being in the incidence of tuberculosis and the need for remedial material action to fight it. In the same report, Pottevin reviewed a wide array of strategies recommended by various medical authorities—from sanatoriums to wage increases for workers—only to conclude that “the essential part of the antituberculosis program, and perhaps the only one in which our immediate action can be effective, is the work of social education.” Teaching the poor not to spit on the ground, to have their lodgings disinfected, and in general to avoid infecting those around them when they became sick—this was the bureau’s crucial duty in the War on Tuberculosis.[63] If the welter of social factors that contributed to the spread of disease could be distilled for the most part into a matter of personal negligence, the failure of the state or private philanthropy to commit substantial resources to the battle would be to some extent justified.

The hypersensitivity of Havrais officials to their city’s death rate continued through the years preceding World War I. In 1911, for example, Dr. Adrien Loir (then director of the Bureau d’hygiène) went to great lengths to explain away the overall mortality figure from the previous year. In the bureau’s annual report, Loir explained that several circumstances beyond the administration’s control inflated the numbers for Le Havre, especially in comparison to other cities. “Our mortality statistics in Le Havre are augmented by three important causes”: (1) counting residents of suburban towns who died in the city’s hospitals as part of Le Havre’s total deaths; (2) a peculiarity of major ports, the influx into the city of would-be emigrants from the “interior,” who took up temporary residence in Le Havre pending departure only to fall ill and die in its hospitals; and (3) assigning to Le Havre the deaths of foreigners who drowned in the port area, who disembarked from ships already ill, or who died aboard ship less than two days before arrival in Le Havre.[64]

Although many cities made similar claims about being unfairly burdened in official statistics with deaths that rightly belonged to other jurisdictions, there may well have been some truth to Loir’s contentions. Nevertheless, the insistence of city officials in pressing these claims and the variety of excuses invoked suggest that other factors were at work in these years. For one thing, a national public health law passed in 1902 not only required all cities to establish health offices modeled on that of Le Havre but also mandated special inquiries and remedial measures for those cities that exceeded the national average in mortality for three years in a row.[65] Furthermore, health statistics (including overall mortality and tuberculosis mortality) for all major French cities had been compiled and published by the Ministry of the Interior only since the late 1880s; this Statistique sanitaire des villes de France for the first time allowed cities to be compared in matters of health and disease. In Le Havre, the defensive attitude surfaced especially in the decennial report covering the 1890s. The compilation of the report coincided with a period of intense public discussion and debate concerning public health—and tuberculosis in particular—with governmental commissions investigating various problems and possible reforms and with parliament debating at great length the public health law finally passed in 1902. If ever Le Havre’s status as tuberculosis capital of France were exposed to public view, this was the time.

In fact, the fate of the 1902 public health law parallels the course of antituberculosis efforts in Le Havre and of the French War on Tuberculosis as a whole. The law seemed to pursue an aggressive strategy in the area of information gathering and surveillance alongside a cautious approach to material intervention. Its principal provisions included the establishment of bureaux d’hygiène, the mandatory declaration by physicians to local authorities of all cases of certain contagious diseases (tuberculosis was not among them), and requiring special investigations whenever a city’s mortality rate consistently exceeded the national average.[66] In a circular to departmental prefects in 1907 concerning the application of the law, Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau insisted that one of the chief roles of government in public health matters was as “propagandist” and “apostle,” educating the population to ease the acceptance of hygienic ideas and practices.[67] Moreover, several years after its passage, the nation’s public health authorities agreed that the law was rarely enforced and that without enforcement, it could have little effect. Even the new bureaux d’hygiène created by the 1902 law remained nothing more than “phantom boards” and accomplished very little, some hygienists complained.[68] In Le Havre, where the health board was much more than a mere phantom, the enforcement of public health regulations was still no sure thing, ranging from vigorous to half-hearted.

| • | • | • |

Enforcement, Controversy, and Protest

The enforcement of sanitary regulations in two separate incidents, thirty years apart, perhaps best evokes the unfulfilled promise and unsustained energy of the War on Tuberculosis in Le Havre. They also illustrate the extent to which (and in what form) mainstream medical knowledge concerning tuberculosis reached the general population. In the early 1880s, when boundless energy and optimism animated the hygienic campaigns of Siegfried and his circle, city officials were willing to use the tools of public health expertise to combat insalubrity, even when the sanctity of private property was at stake. In contrast, three decades later, with no such property interest involved, not even citizens’ demands could rouse the administration to action. The first case involved a pair of buildings on the rue Saint-Thibaut in Le Havre, built between 1865 and 1871 for low-income housing, with the mayor’s authorization to bypass local building standards. In August 1881, the city’s Commission des logements insalubres inspected the buildings and found them unsanitary. The commission’s report called the houses “a receptacle of intolerable odors and miasmas [and] a hotbed of infection, dangerous for [their] occupants and neighbors.” Following this report, the city council in October 1881 declared the buildings unfit for habitation. The buildings’ owners, the Bénard brothers, appealed the city council’s decision to the Conseil de préfecture at the departmental level. They admitted that the structures were less than solidly built, “in order to be rented to workers,” but maintained that the courtyards were large enough and the ventilation sufficient to meet hygienic standards.[69]

The Seine-Inférieure prefect’s office sent two members of the departmental Conseil central d’hygiène to inspect the Bénards’ properties. The buildings’ occupants welcomed them courteously and made no complaints about their living conditions. The inspectors found neither illness nor “déchéance physique” among the inhabitants; furthermore, they claimed to have investigated the buildings’ mortality figures from the previous two years and found them below the city average. The Commission des logements insalubres report, they insisted, was “forced, exaggerated.” “The filth and poverty…of the tenants, source of an unpleasant and noxious stench,” should not be confused with unsanitary features of the buildings themselves, the inspectors maintained. If the same inhabitants were moved to more “comfortable” lodgings, their “carelessness, laziness, disorder, and poor conduct would reproduce the same state of affairs in very short order.”[70] Blaming the ill health of the poor on their own habits and morals, of course, was to become a standard feature of the French response to tuberculosis.

The prefect’s inspectors concluded that to uphold the city council’s decision would be unjust, inasmuch as “the salubrity of housing has its degrees”; an overly strict enforcement of sanitary regulations would entail a loss of so many housing units that “social necessity” demanded a hands-off approach. After all, they reasoned, “these are the lodgings of poor workers,” who could not afford to pay higher rents elsewhere. “Where would these 132 unfortunates go” if their buildings were condemned? They recommended a pragmatic response, in which such buildings would be improved by limited remedial construction but not ruled off-limits for housing entirely.[71]

The most significant aspect of the Bénard case may be the way in which Le Havre city officials and the Bureau d’hygiène responded to the departmental report. In July 1882, four months after the prefect received his inspectors’ conclusions, the city’s lawyer asked his staff to check the bureau’s files for the actual mortality statistics in the Bénards’ buildings. The bureau had of course been keeping the casier sanitaire—records of causes of death in every building in Le Havre—since its establishment in 1879. The city’s figures told a story very different from that of the departmental inspectors’ report. Although it is unclear whether the casier sanitaire data applied to all or only some of the housing units at 40 and 42 rue Saint-Thibaut, they showed more than double the number of deaths reported by the prefect’s inspectors, including four from pulmonary tuberculosis and five from infantile enteritis since late 1879. As mayor of Le Havre at the time, Siegfried cited the casier sanitaire statistics in a letter to the Conseil de préfecture of the Seine-Inférieure. “No demonstration could be more conclusive,” he wrote, “nor justify more amply the protective measure taken by the city council”—namely, the complete condemnation of the buildings for human habitation.[72] In essence, Le Havre officials were attempting to use a new administrative tool, the casier sanitaire, to force action by private interests in the name of public health.

Le Havre’s municipal archives show that the city continued to press its efforts to condemn the buildings, though they do not reveal the affair’s ultimate outcome. In August 1882, the Conseil de préfecture overturned the city council’s interdiction d’habitation but ordered repair work done within two months. The following April, the work was still not even close to completion, and Mayor Siegfried instigated further legal proceedings against the Bénards. In late June 1883, the city engineer reported that the repairs had either not been done or had been done improperly; thereafter the available evidence falls silent.[73] Whatever the final dispensation of the Bénard case, it provides a snapshot of official Le Havre’s attitude toward tuberculosis and public health around the time of Koch’s discovery of the disease’s microbial agent. Before contagionism had fully penetrated the public sphere in France, the municipal government had not only developed a sophisticated administrative tool (the casier sanitaire) to monitor the sanitary status of the city’s housing but also shown a willingness to use it to bring about material change. Just as important, perhaps, is the fact that the Le Havre administration never went to such lengths again, though it maintained the casier sanitaire for many years thereafter.

In fact, the city’s approach could scarcely have been more different thirty years later, when another “affair” related to unsanitary housing came before Le Havre’s Bureau d’hygiène. In September 1912, Mayor Henri Génestal received a letter from Auguste Clouet, a concerned constituent who had approached him in person a few weeks before. Clouet was anxious about the health of his young nephew, Robert Lefebvre, who since the death of his mother had been living with his grandparents at 66 rue du Perrey in Le Havre. Clouet’s concern stemmed from the fact that the child’s mother had died of tuberculosis and from the filthy state in which the grandparents kept their house. Clouet sought to gain custody of the child—promising to send him to live in the countryside—and asked for the mayor’s help.[74]

The mayor asked Adrien Loir, director of the Bureau d’hygiène, to have a member of the bureau’s staff look into the situation at 66 rue du Perrey. The staffer, M. Legangneur, reported back within ten days, taking the view that the Lefebvre boy and his grandparents lived quite healthy and contented lives amid considerable poverty and squalor.