6. The Search

Other Jewish wills surely await discovery in the Christian notarial manuals. They are rare and will yield only to serendipity, to researchers alert to their possibility. Professor Jill Webster has called my attention to one such will in the Arxiu Històric de Girona, in the Testaments manual of Pere Perrini of Castelló for 1326. Long and complex, this will, the only Jewish testament Professor Webster encountered “in some thirty or forty manuals,” details the last dispositions of Jucef Bonastruges of Castelló de Ampurias.[1] A will by Ismael de Oblitis (Olite?) of Navarre was the object of King Pere’s attention in 1341 at Barcelona, a reminder that Jean Régné’s exhaustive catalog of Jewish documents in the crown registers ends abruptly in 1327, leaving a quarter-century of rich materials unscanned up to 1350.[2]

Besides such archival findings, occasional Latinate Jewish wills continue to turn up in published analyses of Jewish communities in various corners of the realms. Thus Manuel Grau Montserrat, in his doctoral thesis on the Jews of Besalú from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century, gives the will of “Carecausa Mayr” from the Olot archives in the early fourteenth century. (Cara cauza in Provençal, as Simon Seror notes, means “beloved person.”) And Gabriel Secall i Güell, among the documents in his volume on the Jews of Santa Coloma de Queralt, appends four wills.[3] Considering the many Jewish wills revealed by crown activity up through the first quarter of the fourteenth century, it is logical to expect the same high incidence of extrinsic references to wills by the royal chancery thereafter—even more so, since the volume of general documentation dramatically increases. Crown notices about late fourteenth-century wills, from 1350 to 1390, must also be very numerous.

Another direction for Latinate Jewish testamentary research is to move forward chronologically. If the temper and context of Jewish life in the realms underwent modification in the post–Black Death generation, the communities also enjoyed a strong measure of continuity and strength until the riots of 1391 signaled catastrophic changes. Thus the later fourteenth century may be considered a time of “late” early Latinate wills, valuable for evidence both of acculturative weakening and for continuities.

Three more Puigcerdá wills may be introduced here, ranging from 1370 through 1398 to 1401, along with a will of 1388 from Majorca. Simple analysis, without contextualization, will suffice for the three, letting the pattern of past testaments provide points for reflection.

| • | • | • |

Late Fourteenth-Century Latinate Jewish Wills

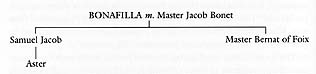

Bonafília or Bonafilla, “wife of Master Jacob Bonet,” in her testament of 18 January 1370 at Puigcerdá appoints as her executors Master Boniac Abraham and Yitzhak Astruc (“Itzah Struch”). “Master” here is ambiguous but probably indicates status in the aristocracy of the ḥakīm class as savant-physician. Besides burial in the Jewish cemetery, Bonafilla leaves 10 sous for oil for the lamps of the synagogue (scola) and “10 in alms for the Jewish quarter [call] of Puigcerdá.” One son, Master Bernat of Foix, receives 5 sous; the other, Samuel Jacob, gets 5 sous plus an immediate payment of 50 pounds.[4]

The name Bernat in a Catalan-Occitan Jewish family seems unprecedented and suggests an error of some kind. The careful index by Yom Tov Assis for the catalog by Régné, covering nearly 3,500 charters about Jews for over a hundred years (1213–1327) of Arago-Catalan crown registers, does not turn up a single Jew named Bernat; even the short index of converts to Christianity has none. Among Catalan Christians the name was very popular; a first-name index for the documents of Jaume the Conqueror lists over 150 Bernats plus nearly 70 more in abbreviated form. Of Germanic origin, the name has none of the equivalence value of a name such as Benet (“Benedictus”), paralleling Hebrew Baruch or the then popular Berachya. Was this Bernat a convert? It is highly improbable that an apostate son could have appeared in a public Jewish will at this period. Could the scribe have intended the Catalan name Bonat, common to Jews and Christians then?

Paleographically, all letters of this name in the will are clearly present in Romance form, except for the first e, which an overstroke indicates: BRNAT. Since Bonat/Bonanat has a deformation or variation as Brunat, Boronat, and Bornat, such readings of the name would solve the puzzle. It is not necessary to fall back on that analysis, however, since Seror has found a Jewish Bernart and a Benaart in Paris and a Bernardus in Marseilles while compiling his lexicon of medieval French Jewish names. The dates of appearance of these names are instructive—respectively 1291, 1292, and 1351—as they are relatively late and therefore suggest the acculturative pressures then increasing. Since Jews of this time and place took various kinds of nonreligious names, including many popular also among their Christian neighbors, perhaps we ought not to cavil at “Bernard.” But the name does fall outside almost all contemporary patterns for Jews in the realms and invites in its family context a strong suspicion of undue influence from and deformation by the surrounding Christian culture.[5]

In this testament, 20 sous go to Joia, daughter of Samuel (ben) Abraham Cohen (Joi, like Goig, is Catalan for “joy”). Everything else, movables and real property, goes to Samuel Jacob’s daughter Aster, granddaughter of Bonafilla. All seven witnesses are Christians. All money is in Barcelonan sous. All the principals are Jews of Puigcerdá. The family structure is

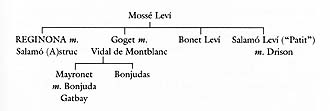

Ten years later, on 24 March 1388, Regina or Reginona drew up her will at Inca on Majorca island.[6] She was the daughter of Mossé Leví and the wife of a tailor of Inca named Salamó (A)struc. Gravely ill but with faculties intact, she declares her husband both executor and universal heir. Her first concern is that all her debts and obligations be met from the estate “without legal form or fuss.” She wishes to be buried in the Jewish cemetery at Inca “before the grave of my said father,” with suitable ostentation: “well and elegantly [and] according to Jewish custom.” Reginona’s sister Goget, wife of Vidal de Montblanc of Majorca, receives 3 pounds “to buy clothing for mourning.” Twenty sous each go to Goget’s son Bonjudas (“Boniuetes”) and her daughter Mayronet, the wife of Bonjuda (“Beniuha Gatbay”). Twenty more apiece go to Reginona’s brother Bonet Leví, to another brother Salamó Leví “alias Patit,” and to the latter’s wife Drison. Reginona also gives 10 sous, “for the love of God,” to buy oil to burn “in the lamps of the synagogue.” Six witnesses sign, with the notary doubling as a seventh witness; all six seem to be Jews.

Several new names occur. Reginona is simply a diminutive or intensifier of Regina, as Meironet (“Mayronet”) is of Hebrew Meir. Beniuha and Boniuetes are variants of Bonjuda(s), bon slipping into ben. Patit is Catalan Petit, for the Hebrew name Katan (“small”); it is also a Catalan Christian lineage. Three names pose a challenge. Goget seems to be a diminutive of Goig in its variant Gog; Drison may relate to the Occitan name Treysona, cited by Seror only once, at Manosque. The masculine surname Gatbay, despite its intrusive t not untypical in Catalan, is the common Jewish surname Gabbai, with an Aramaic etymology as tax collector or as synogogue functionary. The immediate family, in order of appearance, is small:

Ten years later Jacob Boniac drew up his will at Puigcerdá. Dated April 1398, it leaves a series of small legacies to friends and relatives, including 30 sous for one grandson and 20 to another, 20 sous “to my relative or cousin Ana Goya,” 10 to her son, and dowries of 40 sous for each of the daughters of his great grandson Deglossal (Deulosal) Vidal. He returns a dowry of 40 Barcelonan pounds to his wife Marcona and names her universal heir for the bulk of his possessions. For charity he leaves 5½ sous for “the abashed poor,” and “all my clothing to my poor relations at the discretion of my executors.” Clothing in the Middle Ages was often valuable and cherished, handed down through several generations. Two pieces here are held out for favorite relatives. Twenty sous are set aside as a fund for oil, to be burned “in the synagogue of the Jews of the said town to honor God,” at the rate of 5 sous yearly over four years. The seven witnesses include Guillem Gueca taverner and two Jews, Samuel ben Abraham Cohen and Bondit ben Samuel Cohen. In his codicil of 30 February 1401 he selects as executor “Master Meir Bonet physician,” a Jew of Perpignan. The witnesses are divided under the rubrics “Christians” and “Jews,” the latter comprising the physician Bonet, Deglossal Vidal, and Jacob Cohen. New names here are Catalan Anna from Hebrew Chana/Ana, Marcona as feminine diminutive of Catalan Marc, and Bondit as the past participle of Catalan dir in the sense of “well said,” unless it is variant here for Bendit (“blessed,” for Hebrew Barukh).[7]

Three years later the wills continue. Vidal Bonafos senior (pater), for example, a Jew of Perpignan taken ill at Puigcerdá, drew up a long will on 27 February 1401, adding a codicil on August 31.[8] The codicil expands his largesse by giving 2 sous apiece to those assisting him in his last illness. A number of money gifts, some in florins, include: “I leave [money for] a lamp which is to burn in the synagogue or scola.” But all such post–Black Death wills mirror a different society, both Christian and Jewish. They are not so precious as the early models.

| • | • | • |

Cognate Occitania

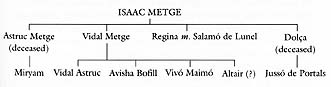

A collateral direction for research on Jewish wills in the realms of Aragon is to turn toward the cognate communities of Occitania, which had been linked culturally and often enough politically with the Catalan regions. Carcassonne was one such entity, its ruling viscounts the Trencavels having been vassals of the count-kings of the realms of Aragon until the Albigensian crusade drove the last viscount into refuge at the court of Barcelona. At least one will from Carcassonne has been discovered and studied, drawn by Isaac Metge in 1305. Ill to death “and desiring eternal life,” Isaac drafted it in his own house on August 5. Choosing burial in the Jewish cemetery of Carcassonne, he designates as universal heir and executor his surviving son Vidal Metge. Vidal’s own four sons receive two and a half hogsheads (150 gallons) of wine. They also receive as lodgings a room and a kitchen in Isaac’s house; if dissatisfied, they can have Vidal rent them a residence of equal value outside the house. Isaac’s daughter Regina, wife of Salamó de Lunel, has her choice between 100 sous of Tours or else a ring with a sapphire mounted. The son of Isaac’s daughter Dolça (presumably deceased) and the daughter of his son Astruc Metge (also presumably deceased) are to share equally in 100 sous, which are to be invested for them by some undesignated friend of the family. Within six years of Isaac’s passing, his heir is to have a crown made, “which is otherwise called in Hebrew ‘aṭara,” for the rod of the Torah, “which I had made for use of the synagogue of the Jews of Carcassonne.”

Another gift for the Jewish community is carefully explicated. “In remission for my sins I leave a hogshead of kosher wine [modium vini iudaicum] every year,” during the heir’s lifetime, to be “given and divided in four parts and four festivities, namely, one measure on the feast of the Huts, and another measure of wine on the feast of the Lord’s Easter, and another measure of wine on the feast of the Circumcision of the Lord, called in Hebrew Rosh ha-Shana [Rossana].” The transcription seems defective here, since only three periods are stated. It is odd to see the notary (surely not the testator) expressing the several times according to the Christian calendar of feasts of Jesus. He also seems to equate the Christian New Year (the Circumcision, or January 1 in the French calendar then used at Carcassonne) with the Jewish New Year in autumn; is he using a calendar metaphor? An alternative explanation might be that the missing fourth distribution belongs after the Circumcision distribution, a suspicion strengthened by a subsequent instruction to begin the whole process on the “feast of Blessed Michael [the Archangel] in the month of September in one year,” a feast less inappropriately linked to the time of Rosh ha-Shana. The four distributions may honor the four biblical “new year” divisions of the year, of which only the autumn feast today retains that name. The selection of the feast of the Huts or Tabernacles, the Hebrew Sukkot, recalls a similar testamentary legacy seen above in chapter 4.

Isaac’s will yields a small family tree:

Of the name forms in the manuscript, some are familiar from previous encounters—Latin Astruch, Bonusfilius, Dulcia, Regina, and Salamonis. Others may seem less ordinary—Meriama, the augmentatives Jussonus and Vivonus (respectively, Jucef and Vives), and Jussó. Three forms pose a challenge. Altirenus may echo the Catalan and Castilian prename Altair. Evescha is less likely to be a variant of Evesque/Esveque for Cohen, unusual for these parts, than the more obvious biblical Avishai in its variant Avisha. Mariamona, if not a miscopy, may resolve into either Marimon (from Miremont in France) or Maimó. The witnesses at the end are four Jews and two Christians, the latter respectively a cloth finisher and a weaver.[9]

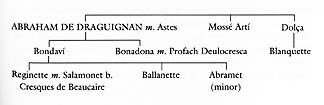

More elaborate, and with transcription of the full testament, is the last disposition by Abraham of Draguignan on 10 May 1316, discovered by Joseph Shatzmiller and introduced in his Shylock Reconsidered. Draguinhan, or modern Draguignan, stood some forty miles northeast of Toulon. It lay in the Marseilles/Provence sovereignty that had been an appanage or affiliate of the realms of Aragon until the 1240s when the French king’s brother Charles of Anjou drove out Jaume the Conqueror in a military scuffle for control. Shatzmiller describes the surviving notarial draft, with notes “scribbled at the margins” and the “changes introduced by the testator.” The text itself tells how Abraham, “a Jew, citizen of Marseilles,” being “of sound mind” (“body” is deleted), makes the following will. To his son Bondaví he leaves 500 Marseilles pounds in money, warning him to be “silent and content with this” since it is all he will get. Abraham’s wife Astes he appoints “owner and mistress of each and every possession of mine, and that she is to keep and possess and enjoy the fruit of the said goods.” Astes also receives “six silver boxes.” To their daughter Bonadona, wife of Profach Deulocresca, go 100 Marseilles pounds (replacing a deleted 500) together with the dowry her husband had already received. Unless Bonadona will sign a formal public document waiving all further shares, she is to lose all but a token 5 Marseilles sous.

Abraham’s grandson Abramet, son of Bondaví, receives a vineyard in the Marseilles district, plus two silver belts (“both are worth together 10 pounds”) and three rings (a gold ring with a diamond, a gold ring with an emerald, and a ring with a sapphire), together with 20 pounds. As long as Abramet is a minor, his father Bondaví must not himself profit from the vineyard. Abraham’s granddaughter Bellanette gets a gilded silver belt worth 14 pounds, as well as 60 pounds for buying more jewelry, 25 pounds in cash, “and a silver box I have worth 4 pounds.” For Abraham’s brother Mossé Artí there is a cash gift of 10 pounds. To another granddaughter Reginette, also Bondaví’s child but married to Salamonet the son of Cresques of Bellcaire (modern Beaucaire), Abraham gives “a silver goblet I drink from and a gold ring with a stone called a diamond worth 6 pounds of the said money (from what I have in my box), and a silver bellholder, and a house located in the Jewish quarter [juzateria] of Marseilles bounded on one side by the southern synagogue.” He also leaves 25 pounds “to my niece, Blanquette, daughter of my sister Dolça,” and adds in a scribbled note the right of Salamonet to live in and share the house. Finally, for everything else Abraham declares as universal heir his son Bondaví. That concluding stipulation of a universal heir, a requirement in Roman law for wills, seems to be an afterthought, tacked on at the notary’s insistence. The testator Abraham had written off his son earlier in the will, explicitly refusing to give him anything beyond a lump-sum gift. Now Abraham has reintroduced the son as heir to everything not expressly given away.

Shatzmiller has fleshed out the portrait of this patriarch and his family, mostly through the records of a lawsuit against the son Bondaví in a loan dispute in 1317. Shatzmiller also carefully analyzes the family’s wealth and prominence as well as peculiarities of its structure and the economic situation of Provence at that moment. For the present purposes this early Latinate testament may serve to reinforce the impressions and patterns left by the series of contemporary wills in the realms of Aragon. Valuable keepsakes play a more prominent role in this will, either because Abraham was richer than the other testators we have encountered or because he had no chance to pass out pretestamentary gifts. (He was dead, his will probated, and his legacies released within three months of having recourse to the Christian notary.) Again the force of personality breaks through the ritual formulas, revealing the authoritative father figure, his tender attitude toward his wife, and some family tensions. Ever the businessman, he prices items with care. Yet no philanthropies appear; doubtless the community had secured these or their promise in timely fashion from so distinguished a businessman. Pieties are not expressed—again perhaps the businessman at work. And as in some other wills, only the close family is involved, down to grandchildren and a niece. The family tree is nicely displayed. This seems to have been a warmly close family or at least one given to pet diminutives: Abramet, Bellanette, Blanquette, and Salamonet.[10] A family tree would include:

As with the wills of the realms of Aragon, so the Latinate wills from this affiliate or cognate culture can be chronologically extended into the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with due precautions and recontextualization. In this connection the fifteenth-century Jewish notarial wills found by Danièle Iancu-Agou for Aix-en-Provence, Arles, and Marseilles deserve notice, as does the current work of Jacques Chiffoleau at Avignon.[11] The findings at Aix are instructive. Iancu-Agou encountered Jewish wills there only for the late fifteenth century and after; although 106 Jewish marriages turned up between 1460 and 1500, only five wills have joined them. For the early modern period 1501–1525 thirty wills survive at Aix, all, however, all from converted Jews already immersed in an alien context and testamentary tradition.[12]

Monique Wernham has similarly explored the Jewish community of Salon-de-Provence just northwest of Marseilles for the very late period of 1391 to 1435. At one point, drawing from the contents of thirty notarial wills from sixteen families (but transcribing none), she is able to graph eight family trees, to conjecture community wealth, and to analyze the objects of charitable legacies. The larger number of these wills come after 1415.[13] No large body of Jewish wills has thus far surfaced in the Occitan regions for the time period of this book; the few early wills we do have in hand do not encourage comparison in size with the larger amount of testamentary information from Arago-Catalan wills, lawsuits, and notices. Researchers alert to the value of wills and materials connected with wills may one day alter that imbalance.

| • | • | • |

Geniza Wills

Shlomo Goitein was able to ferret out a number of wills from the hoard of discards and fragments constituting the celebrated Geniza papers. Jumbled over the centuries into a synagogue room in Old Cairo out of reverence for the sacred Hebrew script they bore but lacking any relationship or intrinsic value, the collection constituted a giant wastebasket. Now scattered in archives over Europe and America, these papers total some quarter of a million items; about seven thousand are proper historical documents, as against literary or other materials. “The Arabic language prevails” in that documentary material, though expressed mostly in Hebrew script; Arabic had replaced Aramaic in Jewish courts in Egypt, with Hebrew making some recovery from 1200 on. The chronology of these historical documents stretches from the eleventh into the thirteenth century; business with Sicily, Tunisia, and elsewhere in the West is prominent. “Wills and deathbed declarations are disappointing, insofar as they consist almost exclusively of dispositions about property,” though this “often gives a clear idea not only of his possessions but also of his mind.”[14]

Chapter 1 above discussed categories, structural characteristics, and some peculiarities of the Geniza testamentary genre. Here a sampling from the wills themselves seems appropriate to suggest continuities and discontinuities and to invite comparison with the Latinate variety. Goitein does not say how many wills or fragments of wills can be found in the Geniza collections or how much of the surviving testamentary information comes from collateral documentation involving the wills, such as lawsuits or inventories. He does transcribe five wills in extenso, describes another in lengthy detail and context, and gives brief résumés or high points from five more.

The wealthy businesswoman Karīma bint ‘Ammār al-Wuḥsha (“the desired”) deserves first place in line as the most prominent woman in the Geniza collections; both her piety and notoriety (including expulsion from the synagogue on one occasion) are visible in various documents. Her unusually detailed testament was drafted by the court clerk Hillel b. Eli. A divorced woman with a daughter, she also had an illegitimate son from an illicit union. For the purposes of the will her estate was worth 700 gold dinars (2 dinars might have been an artisan’s monthly wage) when she was preparing to die in the early eleventh century. She had already drawn up three Arabic inventories of all of her assets and liabilities, with instructions for acting on each item. She leaves her one surviving brother 100 dinars, her sister 50, a cousin 5, and a stepsister 10. Some personal mementos such as rings and clothing also go to each; the cousin receives, for example, “the bed on which I lie but not the carpets.” Al-Wuḥsha sets aside a tenth of her estate for charity, leaving 25 dinars to the Jewish cemetery, 25 more to divide among four synagogues (“for oil, so that they may study at night”), 20 for “the poor of Fustat [old Cairo],” 2 for an orphaned relative, and 10 to Yūsuf’s wife and her two brothers.

Al-Wuḥsha plans her funeral carefully, sparing no expense. Her coffin (used rather as a bier) is to cost 6 or 7 gold dinars; her seven items of burial dress are described and individually priced: robe, wrap, skullcap, wimple, kerchief, veil, and cloak, adding up to some 25 dinars. Twenty dinars then cover tombstone, pallbearers, and the cantor “walking behind my coffin.” The bulk of her estate “including the rugs and the carpet” go to her illegitimate young son Abū Sa‘d. This includes 300 dinars “in gold” at home, 67 more on deposit, and several hundred in loan collaterals. Her daughter, known from other documents to have been alive, receives neither gift nor mention. “Not a penny should be given to the boy’s father,” though al-Wuḥsha does waive 80 dinars in loans to him and adds a gift of 10 dinars. She names a schoolteacher acquaintance to live in the family house for a weekly pittance to teach the boy a sufficiency of Bible and prayer, but only as much as would be “appropriate.” This last provision and her marital history suggest that the boy was a mamzer, not merely illegitimate but from a union legally barred, with the consequent liabilities of mamzerut status.[15]

In another testament a pious lady of Old Cairo in 1066 wills her house, worth some 170 dinars, in neat shares. A third share (“eight of the twenty-four parts of the house”) goes with its rents to two local synagogues. Another third is divided between a brother and a niece. Of the remaining third, half is for a friend’s dowry. This left a twelfth of the house, already sold to the daughter of her stepsister, and a final twelfth for funeral expenses. “Two parts of this house shall be sold and the proceeds used for my burial, namely, to carry my body to Jerusalem, the Holy City.” She also releases her sister as well as her sister’s daughter and grandchildren from any oath or response “before a Jewish or gentile court,” presumably in connection with ante mortem gifts in lieu of legacies. The beginning and ending of the text are so badly damaged that the testator’s name and the witnesses are lost.

A similar concentration on one piece of business is seen in a will of 1090 by a Tunisian merchant who had settled at Alexandria. Ill but of sound mind, he leaves instructions to sell his stocks of sulphur, lichen, and beads. From the proceeds his executor is to give 10 dinars to “the rav” of Egypt, 10 to the synagogue, and all the rest for his funeral expenses. Since the merchandise was both considerable and valuable, the funeral arrangements and especially the “cave” or sepulcher and the “robes” must have been impressive. Again the format is of witnesses reporting a dead man’s words and arrangements. In 1143 the wife of a great merchant at Old Cairo made a dying declaration designed to protect the rights of her parents, brother, and a boy by a previous marriage and to guarantee a grand funeral. Sitt al-Ahl, the wife, had received a house from her father, with the stipulation (made with the agreement of her current husband) that her parents and brother could always live on the upper floor. She notes that the slave girl is hers, not her husband’s, and that the boy is to stay with her mother. She declares that she has nothing belonging to her husband, and she appoints an executor.

Unsatisfied with her present burial clothes, she gives detailed instructions for a hooded robe of fine material, a mantle, a cloak, and bier furniture, “all to cost about 25 dinars,” with a coffin-bier “costing 9 to 10 dinars.” Among the mourners, “wailing should be done by Muslims,” presumably livelier in that profession. Expenses include “the seven days of mourning.” Sitt wishes “to be buried in this house in which I am now”; she is to be carried to the cemetery only when her parents or brother die, apparently so as to lie among her own people in either place.

Yet another will, focusing on a few bits of business and a fine funeral, comes from Sitt al-Ḥusn, wife of a prominent judge around 1150. After some questioning by witnesses to make sure of her coherence and sound mind, Sitt frees two slave girls she had bought and reared as Jews and gives them half of her own half-share in a house as well as “all clothing suitable for women.” She gives the same half-house, actually her home, to the community on condition of respecting the slave girls’ rights to their fourth of the house for life. The matter of her delayed marriage gift from her husband is discussed but dismissed since it would not now come to her. Her eighth of another house is to be sold to cover funeral costs, including burial garments, coffin-bier, cantors, pallbearers, tomb, and the rest. A usual ceremony of symbolic purchase to convey the husband’s approval was deferred, “since it was Saturday.” There were four witnesses, two of them unknown to Sitt.

In 1188 a silkweaver of Old Cairo, the sheik Abu ’l-Faḍl, was interviewed by two witnesses on his deathbed. They tested his mental alertness, as was common in these encounters: “His mind was sound, and he knew what he said and what was said to him; we asked him what time it was and about the identity of the persons present.” Abu ’l-Faḍl testifies that he has “sold” half of his home to his son Abu ’l-Barakāt and now wills the other half equally to his sons Bayān and Bahā. Bayān receives the family’s silk-weaving workshop, but the yarn, silk, house furnishings, “indeed all I possess,” will be sold to pay funeral expenses and the 15 gold dinars owed to his wife as marriage gift. Abu ’l-Faḍl appoints two executors for these transactions, one of them his son Abu ’l-Barakāt, who will also be guardian for his minor son Bayān. Five dinars go to an absent son. The “residue” of all proceeds goes in equal shares to Bayān and Bahā. To his wife, Sitt al-Rīḍā, he leaves six “copper vessels: a mortar, a pail, a wash-basin, a bucket, an oil jug, and a bowl.”[16]

Goitein discusses several other wills in more summary fashion. For example, a huge declaration done around 1100 is unusually full, though only the forty-nine lines of its lower half survive. Goitein sums it under seven headings: assets and liabilities, provision for the wife, choice of his brother as executor and as guardian of the children, charities, division of the bulk of the estate between his children and his brother in equal parts, a note on the firstborn, and a minor postscript. Another will, by Mūsā b. ‘Adayā in 1040, essentially covers dowry and marriage gift to his wife, two dinars to his sister, one to a niece, and a Torah to the synagogue. His son is the exclusive heir, with no need of an executor. This will is in Hebrew.

A similar will was drafted in 1201 at Alexandria for an estate worth 2,550 dinars, an enormous sum. Five executors are named to invest the sum, taking their expenses and half of the profits. The son, then a minor, is sole heir to this fortune. Fifty dinars go to each of two daughters, 10 to each of his sister’s (unnumbered) daughters, and a Torah scroll is to be written and given to the community. Finally, the very late will of 1241 by Abu ’l-Faḍl, a cheese maker, leaves two-thirds of his house to his daughter, just come of age, plus about 2 dinars. A granddaughter gets 2 dinars and his wife 3 dinars (including her marriage gift). The rest goes to his son.[17]

Goitein has observed several times that each Geniza will was more like a final act in a chain of last dispositions. People preferred to make gifts, pay debts, and otherwise round off their lives without the formalities of documentation. Consequently, the wills cannot give us any idea of the decedent’s full estate or extended friendships or philanthropic gifts. A few wills did have to go into more detail—for example, when the testator was a transient or the husband was away on business. Commonly a will dealt with one piece of business or two, distributed a few final gifts, and prepared for the funeral. Latinate wills display some continuity with this tradition of Jewish last dispositions. A marked discontinuity is the relatively less attention paid in the Latinate versions to funerary matters.

Since the religious foundations for both formats were identical, other continuities include the regulations controlling dowry, marriage gift, and women as well as the role of the elder son and concern about debts. If some formalities are noticeably different between Geniza and Latinate wills—the “universal heir” in Latinate wills, for example, and the controlling witnesses in the Geniza—the substance or content often coincided. This coincidence was partly a result of shared religious traditions and partly a function of the common situation of any formulation of last dispositions, but perhaps most important was the role of the will within the family and community as reinforcing a continuum of customs and values.

The Geniza wills seem marked by an attempt to avoid an obvious inheritance pattern in order to preclude interference by Islamic authorities and tax collectors in the transference of property. The Latinate wills seem not to exhibit this caution; they appear generally more open and informative. The Latinate wills also seem more individualistic and varied, even idiosyncratic. More reflection is necessary, however, to probe the differences and resemblances. A larger corpus of wills would, of course, facilitate the operation; Goitein calls attention to other unpublished and unanalyzed wills in the Geniza collections, including one excluded from consideration by its very length.[18] The chaotic nature of the Geniza discards makes it far less easy to identify and contextualize its testaments; in contrast, Latinate wills as at Perpignan and Puigcerdá carry a penumbra of other contracts, from which family information might painstakingly be assembled. And where the Geniza experience is closed, a limited group of wills centered on one locale, the Arago-Catalonian and Occitan notarial troves are open-ended for the researcher, both in terms of the many wills yet to be discovered and the many cities and regions that can contribute.

| • | • | • |

Total History

Each stage in the preceding exploration of Latinate Jewish wills has invited reflection. It would be tedious to repeat here the conclusions and suggestions that emerged. A return to chapter 1, for example, would allow a review of the pluricultural predicament—the paradox of parallel Christian and Jewish societies as semiautonomies, interacting at various levels, notably by their union in the notarial culture, sharing as well as recoiling. The mechanics of that culture, in the analogous activities of the Christian scribe, the Jewish sōfer, and the Muslim ṣāḥīb al-wathā’iq, and the implications of that culture both as a bridge and as assimilative force were introduced in chapter 2 and carried forward into the king’s role in chapter 3. Basic themes running through these discussions are the peculiar character of the last testament and the unique meeting of the Judeo-Arabic and Judeo-Occitan subcultures in the Catalan environment. Actual wills had appeared in the narrative by this point, a large number by indirection in records of crown intervention. Chapters 4 and 5 concentrated on Latinate wills as rescued from the archives of four Arago-Catalonian towns and their Jewish communities. Chapter 5 investigated the role and meaning of women in wills. Finally, chapter 6 presented reinforcing detail from later wills from the fourteenth century and cognate wills from outside the realms but within Occitania.

Some generalizations about the wills themselves remain to be posed. The notarial formalities and tone unify the entire body of Latinate wills here but nonetheless leave the individual wills irreducibly singular, even unique. The testaments range from minimalist, with a few basics on dowry and nuclear family, to expansive. Some testators are wealthy; others show barely enough property to justify the trouble of a Latinate will. A number seek to control the family’s future by imposing conditions or arranging for substitute legatees according to marriages, deaths, or childlessness in that future. One man forbids copies of the will to be distributed except to his wife and his universal heir; another requires his two sons to share his estate for ten years before they can divide it and go their separate ways; another forces an heir to waive further claims under penalty of voiding any possible legacy.

Testators often want their debts satisfied, sometimes specifying that repayment be done without legal fuss, but at least one testator specified that creditors supply proper documentation. One orders all legacies paid within a year of his death; some others, especially where a minor was involved, arrange for investments and profits. Almost all the full wills considered are preserved in paper registers, with notarial compression and radical abbreviations; one Latinate will here is on its “original” parchment, though of course the paper draft is an equally true original and legally authoritative. No less than three wills leave large sums to the king; two of these leave everything to him unless the testator’s conditions are followed. In none of the dispositions is it obvious that the bulk of the estate is visible; instead, the lack of extended family members and of small mementos to friends or philanthropies argues that the testators had followed a common custom in transferring goods well in advance of death.

One wife notes her husband’s approval of the will; one husband notes his wife’s approval. As to formalities, one will records the notary’s fee as 5 sous; several manuscripts have canceling slashes indicating that a full copy has been delivered; most of the wills meticulously repeat the identifying label “Jew” more than seems necessary (except perhaps to a lawyer). A testator mentions his will’s “text” and “form,” another revokes previous wills. Most wills have the standard seven witnesses of Roman law, usually Christians but sometimes with one Jew or, more often, two. One will has four Christian witnesses and four Jews, another six Christians and two Jews. Most of these witnesses, when identified, seem to be artisans (tailor, shoemaker, weaver, cobbler, glover, and such)—perhaps accessible neighbors, perhaps paid volunteers, or both.

Institutions and domestic paraphernalia turn up regularly. They include the synagogue, of course, and the Bet ha-Midrash, with oil both for liturgical and study lamps, as well as Torahs and the Torah crown. The wife’s dowry (and dowries of daughters both single and married) are commonly discussed, including a reference to the “Jewish nuptial documents” incorporated into the Latinate legal foundations. The Jewish cemetery appears, with a few asides on burial, mourning dress, and funeral arrangements. The inventory of the deceased’s goods is mentioned, though not so frequently as one might expect; one testament waives the count altogether, and others probably omitted mention of this post-funerary action as irrelevant. Vineyards are included several times, either because they were so common in the wider Catalan population or because the Jewish community’s own wine supply involved such properties. The family residence, with some of its inhabitants, is described sometimes as a mansus or hospicium, once on a hill and twice as bordered by specific neighbors. Books were obviously cherished, whether single volumes or libraries (twenty-four books in one collection). Household paraphernalia range from weighing scales, dyeing vat, wine containers, and the wooden chests so ubiquitous then in Catalan homes to clothing of many kinds, cloth, utensils, bedclothes, and at least once a fair number of rings and jewelry.

Patterns of piety, less visible where previous inter vivos gifts had already gone out, can be seen from time to time. One testament names as universal heir God himself, the actual moneys going to dowries for poor girls and education for poor children. Another sets aside enough cash to have 62½ sous distributed annually for ten years on the Feast of the Tabernacles. A legacy of 6¼ sous goes to the half-penny Jewish alms fund. One woman writes off all loans owed to her below a certain sum. Another leaves her bedclothes and 100 sous to charity. Yet another remembers the “abashed poor,” who sought to keep up appearances from their previous state. One man provides that if his daughter as heiress dies childless, his entire estate is to revert to alms, for his “soul’s salvation.” For God’s love, another testator contributes to a bridge over the river Tet. In the end the general impression emerges that these wills were family affairs, especially concerned with obligations to family; formal charity seems to have been managed by other means.

The universal heir was usually the son (or even two sons), or in their absence a brother or preferably the testator’s husband, wife, or various in-laws. In one case the executor-guardians were two Christians with two Jews, while in another a super-executor monitored the original executors. One executor, noted in chapter 3 above, worked at his task sixteen years; another group secured a charter of approval for their efforts from the ward when he was finally of age. Some widows were executors for their spouses. Human touches abound. One testator forbade the home to be sold without the family’s approval and he left 2,000 sous to be paid to his daughter only when she finalized a hoped-for marriage. Another provided care for a daughter until her wandering husband came back home to live. Guardians sometimes were asked to provide a husband for an unmarried daughter. A condition in another will provided support to a married daughter if, on becoming a widow, she returned to the family home. And in yet another will a wife set up an advantageous situation for her husband as a widower, so long as he did not remarry. Interest (usura) is explicitly mentioned in two wills and is implicit in the investments of several. In a society accustomed to widespread slavery in all three communities, only one slave (a half-share of a black woman) turns up. The testator’s seat in the synagogue is duly passed on, but only in a few wills here (and once to a daughter, as a negotiable legacy). Here too the arrangement would have been already made and understood without formalities of law.

The king’s role becomes clear from court records about such wills. The king can confirm in whole, in part, or in “every item”; he can clarify, settle disputes, or arrange investigation or arbitration. With a pardon he can waive prosecution for testamentary fraud, appoint a super-executor to monitor the others, waive the usual inventory of the decedent’s property, sequester the property for a time, compel an accounting, license the executors’ investment in real estate, set conditions (the heir cannot travel or marry before the age of eighteen), or settle minute squabbles (a stolen Avicenna from the dead man’s library). He could give his protection, under penalty of his displeasure and a severe fine, and he could issue a guiatge, or specially formulated charter of protection, covering all the provisos of a will. Closeted with his Jewish savants, the king addressed complex moral issues such as the proper shares for the deceased’s two wives and two sets of children. And in one case, where the provisions of two wills by two different decedents collided and where both disputants were wealthy and distinguished, the king mounted a trial before his person in the Dominicans’ cloister, a public event resembling the showpiece Disputation of 1263 in its externals. In short, the king could and did do just about anything an appellant could petition, a patriarchal role quite comfortable to medieval sovereigns from count to king. The crown addressed Hebrew wills, to be judged “according to the custom of the Jews,” as easily as it took up Latinate Jewish wills that cited Roman law (as in the case of the Falcidian and Trebellianic fourths).

The names in the Latinate testaments hold few surprises, aside from a feminine first name Cohen, one Bernard, and an Ali. Local pronunciations garble even simple names at times and their reconstitution can be difficult or tentative. A few sets of names betray the Judeo-Arabic antecedents of the family, while an ibn can do the same for an individual. How immediate such connections were or how linguistically effective is not apparent simply from the names. Judeo-Arabic names do carry an echo of the massive transference of an ancient Judaism from al-Andalus into European or Christian Spain. The Franco-Occitan names are far more numerous, partly because the transference came in later waves, when notarial records of all kinds began multiplying.

The locale for any number of wills examined here was the border areas closest to Occitania—such places as Palma de Mallorca, Perpignan, and Puigcerdá. Again, one cannot be sure whether a name of Occitan flavor or a clear toponym describes the current bearer’s origin or that of his father or grandfather, except in cases where a clue is provided. Again, however, the mass immigration can be appreciated from the phenomenon of names as a whole. Of toponyms alone, over a dozen show the bearer’s family to have arrived from widely scattered points along the littoral from Narbonne to Marseilles and inland as at Mazères near Toulouse, Alès above Nîmes, Béziers, Beaucaire, Lunel, and even La Rochelle.

A promising field of study would be a comparison of the Latinate Jewish wills and the mass of Christian wills now available. Since fashions and tonalities in Christian wills changed overtly or subtly, such a comparison has to respect the chronological stages in development. Both kinds of will issued from the same notary and from the rigidities and stereotypes of the legalistic notarial culture, but both kinds allowed the testator to express individual and family particularities. Formulaic comparisons should be the easiest; only the notarial version ought to be used in each case, however, since radical compression proper to the notarial codex omits or abbreviates the more routine formulas. The protocol usually disappears or contracts to a few phrases, as do the invocation of God, the preamble of reflections on human destinies, the exposition on motives and present condition, and any extensive titling or rather identification. At the opposite terminal of the notarial draft, the escatocol similarly contracts or collapses—all the end matter, dateline, witnesses, and validation. Fortunately, almost all the Latinate wills keep their witness lists. In the body or text of the will, the disposition in brief form remains, mostly in the appointment of executors and guardians. Here come the place or manner of burial, satisfaction for debts and restitution, and legacies for relatives, friends, or philanthropies (favoring in sequence one’s spouse, children, grandchildren, cousins, and then others). A repetitious corroboration and an enforcing sanction to close the text do not usually appear in the Latinate wills.[19]

Subtle and informal differences, however, will differentiate the Christian from the Latinate Jewish will. Beyond the obvious elements—such as synagogue, Jewish cemetery, names falling within a recognizable range of “Jewish” choices, the removal of pious legacies so often from the testament to previous gifts inter vivos, and the pattern of Jewish law or custom on dowry recovery—perhaps the resolute concentration on immediate family makes an emphasis more common to the Latinate Jewish wills. Reflection should focus on the will as a whole, its tone and mood, and the revelation of the individual beneath the formulas in order to propose points of contrast, of assimilation, or of common culture.

As a historical source, wills are many genres at once. They are legal documents, the aspect under which they were first and for long studied. They are literary products, quite self-consciously so in rhetorical form and inevitably so in their individual substance. They are economic records, strictly tied to the history of money, property, classes, and costs. They are cultural artifacts, revealing mentalities and shaping them, proclaiming and reinforcing family structures, showing occupations, libraries, household goods, attitudes, and values. In that context, as widely acknowledged, they are religious statements, both implicitly and often enough explicitly, fashioning a continuity in piety and practice between the generations and into the next life. Wills are above all human documents—a last farewell, a reaching out, a final time to order one’s domestic world, a solemn last statement, sometimes a cry for help.

Jacques Chiffoleau, in his study on Provençal wills, would have us go beyond an appreciation of all these threads of life to weave them into a unified tapestry, respecting the testament’s unity and meaning in its totality. He sees a dialogue between society, the individual, custom, and law, a union of the sacred and profane worlds the testators inhabited, in effect a histoire totale rather than “a cave of Ali Baba” to be raided as a data bank for each historian’s disparate needs. Chiffoleau views the will as “a veritable expression of civilization.” From the rise of Europe’s urban society in the twelfth century, the will has been “one of the essential instruments that allowed society to reproduce itself,” organizing continuity and “redefining little by little the connections between individual and family, the relations between living and dead, the boundaries of religious influence, the frontiers of the sacred and the profane.”[20]

Underlying all the messages that Jewish wills contain, Shlomo Goitein discerned in his Geniza exemplars several tendencies and two intrinsic themes. Among the tendencies or principles of testaments was making peace with one’s fellow men in preparation for one’s meeting with God. This resolution meant paying all debts, rectifying and clarifying any transactions that would trouble others, and releasing yet others from potential liabilities or claims. Goitein notes: “The list of precautions taken out of consideration for one’s fellow man is endless.” A corollary principle was that a man’s primary creditor was his wife, to whom the “debt” of a dowry and the deferred marriage gift demanded payment and for whom the widow’s oath might need to be waived and various provisions and protections supplied.

Goitein sees another organizing principle as the “general human propensity” (in Jewish society “particularly pronounced”) to establish financial security and family continuity for one’s children. A married daughter was considered to be in another family but received a token gift to show love. An unmarried daughter represented a familial obligation on the testator. An only child, if female, became sole heir “by biblical law,” but prudence in a gentile country might counsel explicit provision to that effect. The biblical double share for the firstborn son could be strengthened by specific legacies, but Goitein noted “in many cases” the tendency to provide equal shares to males and females, or not to seem to prefer one over another. Yet another principle in the Geniza wills was the “exaggerated preoccupation with interment” as echoing religious belief, conveying social status, and expressing personality. Finally, the principle of charity was a priority, even though wills generally expressed only minor philanthropic gifts or none at all, since such large or complex transfer of property was better accomplished in timely fashion before the confection of a will.[21]

Goitein’s two underlying or defining themes, seen as much in preparations and later announcements as in the will itself, involved a staunch “assertion of the belief in the continuity of the body-soul existence,” which “colored all ideas and images of life after death.” In most wills this foundation would be implicit, a continuity of action. The second theme was “the communal aspect of death.” This understanding was manifest in the presence and activity of the community as responsible or caring in the whole death process, including the will. It was equally manifest in the vision of bereavement and death as both “punishment of the community for its long list of sins” and atonement for sins, with the death of a holy person as “a vicarious sacrifice for the community.” Goitein finds that “this concept of death as punishment and expiation as related to human behavior” coexisted with a contradictory sense of a “predetermined life span” finally played out, an idea he believes “essentially foreign to Judaism.” The wills themselves were not the vehicles for expressing such attitudes, but those orientations of spirit belong to the wider meaning of the wills. Immemorial traditions and social energies of the community at large thus framed the simple act of drafting a will.[22]

Such larger horizons aside, the Latinate survivals constitute an important point of entry for the social history of Jewish communities in the realms of Arago-Catalonia and Majorca. Each such document has its autonomous significance, but in series as at Puigcerdá they can slowly accumulate to re-create the people and institutions of a given aljama, especially organizing and associating the isolated data available in greater mass from the many codices recording loans from Jews to Christians. Family genealogies can be constructed and eventually related, surnames grouped, and a basic prosopography attempted. The Latinate Jewish genre itself deserves to be studied as a separate topos, an action immemorially Jewish but (as communicated here in the structures, categories, and expressions of Roman law) a kind of juridical acculturation. A larger familiarity with the responsa literature and other mirrors of medieval Jewish life and law can tease further meaning from testamentary texts both as particular and as group phenomena. Even the pattern of inserts, pronunciations, false starts, and corrections in these hurried records can tell us something of the vernacular expression being translated and transformed into the official Latin.

Such isolated testaments resist discovery. They are random flashes, misprized and passed by as researchers flip the codex pages seeking other data. To search directly is to court tedium and risk minimal results. The best strategy is to alert archival searchers in all fields to ticket such finds and present them to view. This effort will eventually assemble a testamentarium, a body of medieval Jewish lore not otherwise accessible. Goitein laments that “a Geniza has not yet been found in Europe.” Yet the Latinate Jewish wills with their collateral testamentary documentation from crown and society constitute a unique treasure trove, similarly intimate and domestic, much smaller so far, more modest in scope of content but more systematic and abundant in its own speciality.[23]

Notes

1. Arch. Hist. Gerona, Pere Perrini of Castelló (Ampurias), manual no. 73, Testamentos, 1326–1327, ca. (unnumbered) fol. 19.

2. Arch. Crown, Pere IV, reg. canc. 1303, fol. 135rv (26 March 1341), also reg. 1304, fol. 96rv (18 October 1341), this time at Valencia, for Ismael (Hebrew Yishmael, Arabic Ismā‘īl). Bonastruges is a variant of Bonastruc. Oblitas was a Navarrese, later also an Aragonese, noble family.

3. Manuel Grau Montserrat, “Instrumenta judeorum (1327–1328),” Amics de Besalú: V Assemblea d’estudis del seu comtat (Olot, 1983), 155–156. Gabriel Secall i Güell, La comunitat hebrea de Santa Coloma de Queralt (Tarragona, 1986), appendix, docs. 17, 24, 46, 47.

4. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, protocols, Guillem Pere, Compilacio omnium contractuum (2 January–28 December 1370), fol. 105 (18 January 1370). “Sit omnibus notum quod ego Bonafilia, uxor magistri Jacob Bonet Iudei Podiiceritani…meum facio testamentum de bonis meis, ordinando super eisdem meam ultimam voluntatem”; “et in primis eligo meo corpori sepulturam in fossario Iudeorum Podiiceritani”; “item dono magistri [= magistro] Bernardo de Foix filio meo…quinque solidos barchinonenses”; “item lego Joye, filie Samuel Abrahe Cohen Iudee viginti solidos barchinonenses”; “decem solidos pro oleo deserviendo lampades escole Iudeorum”; “decem solidos barchinonenses alemosine del cal Iudeorum Podiiceritani.”

5. Boniac is a variant of Romance Isaac in compound with Romance bon (Bonisac). Hebrew Yitzhar, not a variant of Yitzhak/Isaac, is a biblical name in its own right but less likely here. It does not appear in Simon Seror’s Les Noms des juifs de France au moyen âge (Paris, 1989) for Occitania, but Bernat/Bernardus is on p. 36. On the name Bernard, cf. Catalan Felip used by a Jew (see chap. 4, n. 21, above). On the honorific “master,” see above chap. 3, n. 31. On the name Aster/Est(h)er later in the will, see above chap. 4, p. 86; cf. below, this chap., n. 10.

6. Gabriel Llompart, “Documentos sueltos sobre judíos y conversos de Mallorca (siglos XIV y XV),” Fontes rerum balearium 2 (1978): 188–189, doc. 3 (24 March 1388) from the Arxiu Històric de Mallorca. The transcription has Regino. Phrases include “sine strepitu iudicii et figura”; “coram tumulo dicti domini patris mei…bene et honorifice, more yudaico.”

7. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, Joan de Conomines, Liber testamentorum, 18 April 1398–3 August 1408, fol. 1 (18 April 1398), including “quod omnes vestes mee dentur pauperibus parentibus meis ad cognitionem dictorum manumissorum meorum,” and “pro oleo emendo quod deserviat ad honorem dei scole Iudeorum dicte ville.” His codicil has as executor “magistrum Mahir [Hebrew Meir] Bonet, fisicum Iudeum” of Perpignan. On the name Boniac (Bon Isaac) see this chap., n. 5; on Bonet see above, chap. 3, n. 27; on Deulosal see above, chap. 5, n. 8 and text; on Cohen see above, chap. 3, n. 30; on Goyo see page 109; and on the honorific “master” see above, chap. 3, n. 31.

8. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, Bernat Manresa, 1398–1411, fol. 40 (27 February 1401): “quia nullus in carne positus mortem evadere potest…ego Vidal Bonafos pater, Iudeus ville Perpiniani, licet sim eger corpore tamen sanus mente facio, condo, et ordino meum testamentum de bonis meis”; “lego lampadem que ardet in sinagoga sive scola.” See also above, chap. 1, n. 26 (cf. n. 22–24), for late fourteenth- and fifteenth-century wills from Majorca, Gerona, and elsewhere. On the name Bonafós, see above, chap. 3, n. 33.

9. Roger Aubenas, “À propos du testament d’un juif carcassonnais de 1305,” in Carcassonne et sa région, XLIe Congrès d’Études Régionales Tenus par la Fédération Historique du Languedoc Méditerrané et du Roussillon (Carcassonne, 1970), 165–171. This will of “Isaac medicus” (Catalan/Occitan Metge) is in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, Collection Languedoc, Bénédictins, reg. 82, fols. 107 and 108 (August 1305), not an original but among the copies by Claude Devic and Joseph Vaissète, communicated to the editor by Philippe Wolff. The text has distributions “in festo cabanarum” and “in festo Paschae Domini” and “in festo Circumcisionis Domini dicto in hebraico Rossane”; it mandates “unam coronam qua [= que] alias utatur [= vocatur] in ebraico atara ad opus Rotuli” (besides the textual problems, the editor misunderstands this phrase); it leaves the grandsons “unam cameram et unam coquinam que sunt in passadorio juxta januam desupra stalario domus mee.” The editor remarks that in his extensive research in southern French wills he has never encountered among the formularies a model for a Jewish will; the reason, as seen above, is that the Jews accommodated to the gentile world in these relatively few cases for special reasons, with consequent scribal clumsiness in their own adaptation.

10. Joseph Shatzmiller, Shylock Reconsidered: Jews, Moneylending, and Medieval Society (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1990), 28–35, on Abraham and Bondaví, esp. 29–31 and 224 on the will. The will is transcribed in full in appendix 2, pp. 163–165, from the Archives de la Ville de Marseille, notaires II 19 between fols. 61 and 62. Both father and son are “cives Massilie,” the son to act “tacitum et contentum, ita quod nichil amplius petere valeat in ceteris bonis meis”; “prohibeo quod dictus Bonus Davinus filius meus, pater dicti Abrameti, non habeat nec habere possit nec accipere fructus dicte vinee…non obstante quod dictus Abrametus esset post mortem meam in potestate dicti Boni Davini.” The “cloquaria argenti” can hardly be a belltower but perhaps a bell ornament like the other jewelry here. For local background see Adolphe Crémieux, “Les juifs de Marseille au moyen âge,” Revue des études juives 46 (1903): 1–47, 246–268, and 47 (1903): 62–86, 243–261. Seror links the name Astes tentatively to Aster/Est(h)er (Noms des juifs, appendix 2). Besides the diminutives for Abraham, Bella, Blanca, and Salamó noted, see the name Bonadona above in chap. 3, n. 22, Bondaví there in n. 19, and Dolça on p. 112. Cresques is treated in my introduction. Deulocresca, “may God give him growth,” involves the medieval subjunctive of the Catalan verb créixer, “to grow,” as Cresques (cresqués) involves the optative. The name Profach, which Seror relates to Perfet and Profait, may rather be a variant of the Catalan given-name Profici, from Latin proficere, “to undertake, initiate.” Cf. above, chap. 3, n. 45 and chap. 4, n. 13. Besides the identification Bellcaire= Beaucaire, there are Occitan and Catalan alternatives; see above, chap. 4, p. 85.

11. Daniele Iancu-Agou, “Autour du testament d’une juive marseillaise (1480),” Marseille: Revue municipale trimesterielle 133–134 (1983): 30–35, of Boniaqua Salamias, with facsimile; “L’inventaire de la bibliothèque et du mobilier d’un médecin juif d’Aix-en-Provence au milieu du XVe siècle,” Revue des études juives 134 (1975): 47–80, a notary’s testamentary inventory for Astruc de Sestiers at Aix in 1439, with explanation of the will itself of 21 July 1433 before a Marseilles notary; and “Une vente de livres hébreux à Arles en 1434: Tableau de l’élite juive arlésienne au milieu du XVe siècle,” Revue des études juives 146 (1987): 5–62, with testamentary connections. Professor Shatzmiller introduced me to her work and tells me that she also has four wills from Orange in hand; he also informs me that Jacques Chiffoleau has a considerable number of later Jewish wills from Avignon.

12. Daniele Iancu-Agou, “Juives et néophytes aixoises: Leurs testaments, 1467–1525,” Eleventh World Congress of Jewish Studies, 9 vols. (Jerusalem, 1994), division B, 1:165–172.

13. Monique Wernham, La communauté juive de Salon-de-Provence d’après les actes notariés, 1391–1435 (Toronto, 1987), 26–38, 55–56, 77–81, 180, from the Archives Départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône. R. W. Emery notes but does not describe a will by the Jew Ali Abram at Arles-sur-Tech in 1347, from the Archives Départementales at Perpignan, register 284 of the notarial fonds, fols. 16–24, in his “Les juifs en Conflent et en Vallespir, 1250–1450,” in Conflent, Vallespir et montagnes catalanes, LIe Congrès de la Federation Historique du Languedoc Méditerranè et du Roussillon (Montpellier, 1980), 89. On the name Ali/Elias, see above, chap. 4, p. 99.

14. Shlomo D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 6 vols. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1967–1993), 1:1–28 (introduction); quotes on pp. 10, 14–15.

15. Ibid., 3:188–191, 346–352; on coffins see 5:162. On the Eli/cAlī name see above, chap. 4, p. 99. On Arabic Karīma, also in a Majorcan will above, see chap. 4, p. 78. I owe the mamzer suggestion to David Abulafia.

16. Ibid., 5:145–147 (year 1066), 144–145 (1090), 152–155 (1143), 147–149 (1150), 150–152 (1188).

17. Ibid., 5:139 (year 1040), 137 (1100), 138 (1201), 139 (1241).

18. Ibid., 5:152. A testamentary record on p. 140 has Abu’l-Ḥusayn Mūsā give his wife 50 dinars as the marriage gift plus 10 more as well as clothing and objects bought for her in the marriage but legally his as the husband. He waived the widow’s oath of having nothing from his assets but only in return for her waiving replacement of the clothing listed in the marriage contract.

19. For these divisions and the rhetorical and legal training of the notary, see “Rhetoric and Style,” in R. I. Burns, Society and Documentation in Crusader Valencia (Princeton, 1985), chap. 22, esp. n. 1.

20. Jacques Chiffoleau, “Les testaments provençaux et comtadins à la fin du moyen âge: Richesse documentaire et problèmes d’exploitation,” in Paolo Brezzi and Egmont Lee, eds., Sources of Social History: Private Acts of the Late Middle Ages (Toronto, 1984), 151–152.

21. Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 5:141–142. On the historiography, methodology, and archaeology of Catalan Jewish cemeteries and their burials, see the thorough survey by David Romano, “Fossars jueus catalans,” Acta historica et archaeologica mediaevalia 14–15 (1993–1994): 290–315.

22. Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 5:129–130.

23. Ibid., 2:403.