6. Comic Redemption

The Slapstick Synthesis[1]

People argue about the good, the best, the artistic and the “most popular” film and forget that there is a genre which I dare say always pleases the tastes of all classes of public most: those irrepressible American slapsticks in which the goings-on are so delightfully unsentimental, so tremendously reckless…and whose overflowing humor is simply based on a completely unadorned and open depiction of grotesque, bizarre everyday reality and its very abundant melancholy-amusing “side” effects.[2]

The dissatisfaction with American film which pervaded the entire spectrum of trade and nonspecialist publications, if general, was neither universal nor entirely consistent. As reaction against Hollywood became the rule, exceptions to it were explicitly admitted by pleas that German screens show only the best of Hollywood. “Outstanding” films should be imported; “average” pictures should remain in America. Each category presupposed the existence of the other. However, the line between them fluctuated widely depending on the ebb or flow of the import tide and individual preferences. Thanks to sheer enormity and diversity, Hollywood’s output repeatedly shattered stereotypes imposed on it. Even in the period when Hollywood became a byword for kitsch and predictability, select American films or film types drew attention as filmically innovative and humanly valuable.

By middecade contemporaries rarely identified these pictures on anything but a film-by-film basis. In the period of initiation classification according to genre had seemed both satisfactory and convenient. Society dramas, slapstick, westerns, and historical pictures were identified and ranked by type and polish. But these categories became increasingly inadequate guides to German opinion. Growing familiarity with Hollywood introduced such kaleidoscopic variety into German movie programs and punctured so many commonplaces that a catalogue of noteworthy motion pictures defied summary classification and treatment. Numerous performers acquired German profiles. One could devote individual attention to those like Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish, Douglas Fairbanks or Jackie Coogan, whose representative role in American culture bestowed significance beyond star attraction. Imaginative and cinematographic achievements which intrigued German experts, such as the cartoon, could likewise receive detailed consideration. Yet no simple criteria entirely distinguished motion pictures of average from those of outstanding qualities.

None of this is terribly surprising, except insofar as the swell of anti-American sentiment creates an impression of consistency which did not obtain. It is not the case, however, that no discernible patterns emerge from the crosscurrents of opinion. Just as specific characteristics of American pictures proved particularly irritating, so others commanded appreciation and interest. This chapter and the one that follows it examine two generic types, within which critics or audiences discovered traits deserving attention and approbation. Each in its own way lacked direct German parallels. Motion pictures made by German émigrés to the United States constituted by definition a unique Hollywood product, whose relationship to previous German production drew immediate attention. Slapstick comedy was identified almost from first exposure as a specialty for which Germany had scant counterpart. While winning recognition as a genre which embodied America’s motion picture peculiarities, it proved less vulnerable to critical or popular demolition than other American genres. Although archetypically American, thus un-German in mentality, style and tempo, it earned a place in German theaters and repeatedly compelled critics to qualify damning judgments of Hollywood.

Slapstick movies came to Germany in two distinct forms. One or two act shorts, normally used as program fillers, became familiar during the era of inflation. Because they were exempt from import restrictions, by 1925 they had virtually wiped out domestic production of short entertainment pictures. Feature length slapstick films arrived on the German market relatively late—1923–1924—and remained a relatively small portion of all American features released. However, they drew attention disproportionate to their numbers. Together with the shorts they did much to create and define laughter for Weimar moviegoers.

The first impression made by the shorts which appeared in 1921 and 1922 did not augur well for slapstick’s critical reputation. Even the work of Charlie Chaplin, the king of the genre and a living legend, provoked limited and not always friendly commentary. Elsewhere, especially in France, he had already been elevated by artists and intellectuals from an entertainer to a universal principle.[3] In Germany he met neither immediate nor unanimous acclaim. With the other films in the first wave of slapstick imports, his usually received only passing attention. Worship of Chaplin amounted to sectarianism, as the first high priest of the cult, Hans Siemsen, was later to boast.

In the autumn of 1921 Chaplin had made a triumphal return (his first) to England and had also visited the continent. The British received him almost as royalty. He was wined and dined by the élite and overwhelmed by a flood of letters and petitions from movie fans. The French accorded him a similar reception, crowning it with decoration by the state. But in Berlin he was essentially ignored. According to his own account he went unrecognized until spotted by a former prisoner of war held in England who became so excited he embraced and kissed the famous tramp.[4] Despite subsequent contact with film circles in the German capital, Chaplin rightly portrayed his stay in Berlin in stark contrast to those in Paris and London. The fact that the first of his older shorts (The Rink, made in 1916) had finally just been shown in Berlin theaters weighed little against the wartime exposure to his work in Britain and France which had generated such a massive, enthusiastic following.[5]

Siemsen took critical reserve to Chaplin as a measure of German national isolation after the war. While everywhere else on the globe Chaplin was publicly idolized, Germans continued to worship their erstwhile war heroes.[6] Delayed exposure to his work certainly conditioned the way in which it was received. Apart from the fact that the initial releases were already well aged when they appeared in German cinemas, as shorts they did not typically merit more than passing notice from German critics. However, other factors also came into play. Although critics admitted that German audiences laughed hysterically, they simultaneously trivialized or dismissed the source of laughter. The parallel with attitudes toward the sensationalist serials is striking, not least in critical distance from public responses and in predictions that the genre would wear poorly. The tongue-in-cheek remark that animals in the zoo adjoining the UFA-Palast planned legal suits against moviegoers for infringement of patent on roars, shrieks and bellows emitted in response to Charlie’s antics inferred mutual lack of sophistication on the part of film and audience.

If Charlie Chaplin currently dominates German movie theaters that means little or nothing for the future or the value of German comedy.…A briskly acted, action-packed German comedy has a much higher value than the essentially silly American clown tricks! The audience may well be laughing for the moment at Chaplin’s incredible nonsense, but is neither amused in the sense of that word nor satisfied.[7]

It was the combination of primitiveness and silliness which offended critical sensibilities. Childishness, coarseness and disproportion between form and content headed the list of complaints. Even when comic value could not be disputed, critics referred to the “perfect nonsense” or “nothingness” of Chaplin’s scripts and expressed distaste for the juvenile and excessively brutal character of his comedy.[8] The underlying theme was the irreconcilability of the German and American sense of humor. Such discord provoked intensely personal reactions.

Willy Haas, later an outspoken Chaplin enthusiast, accused the comedian of drawing laughter from contradictory human impulses. At one moment Chaplin primed audiences to laugh at acts of treacherous cruelty. The next moment amusement sprang from expressions of human sympathy. This created emotional schizophrenia, scrambling the logic of human relationships and preventing full identification with his humor.[10] While critics carped, audiences responded with gales of laughter which by all accounts were without precedent in German cinemas.[11] Slapstick shorts, led primarily by the works of Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle and Harold Lloyd, captured the popular imagination to the point that in 1922 exhibitors began to book whole programs of them in place of feature films. More than ever, critics now had occasion to evaluate both the films and their public reception. The disgruntled continued to predict that, like the serialized sensationalist films dumped on the market in 1921–1922, slapstick would eventually wear out its welcome among German viewers. Endless repetition promised to nullify the attraction of its momentarily fascinating tempos and stunts.[12] Those, by contrast, who began to recognize in the genre, particularly the dated Chaplin shorts, comic value for which Germany had scant counterpart, sided with the public. Even before they discovered metaphysical principles or political messages in slapstick, they joined moviegoers in gratitude for the sidesplitting laughter.[13]He remains a splendid joker in a mediocre field. However filmic, however filmoid he may be; however much he may conform to the a priori of film, however much he moves in keeping with the laws of the camera—it does not especially move me. I speak German—not American. I’m not a child on the potty with a thick cigar in my mouth. Much may seem very humorous—I’m not fond of jokes based on mechanical things, on machines and objects. He is brilliant in his own style, but this style has so far not been very rich in content.[9]

To the extent that dissatisfaction with this genre persisted through middecade, it adopted arguments used to deprecate Hollywood in general. Defensiveness about Germany’s cultural orientation generated resistance to this facet of the American invasion as well. It remained rooted in the assumption that American comic formulae did not match or satisfy German requirements. Applying criteria appropriate to other media and styles, some critics denigrated slapstick as unsubstantial, repetitive and unsuited to German tastes. Hand in hand with charges of vacuous screenplays went disparagement of the acting as really nothing more than schematized clowning.[14] More broadly, slapstick, like the serialized westerns, functioned as the embodiment of American primitiveness and a corrosive influence in Germany. Paul Sorgenfrei argued that although audiences were spellbound and laughed hysterically at American slapstick, public tastes were being totally corrupted by overexposure. He rationalized this judgment with a well-worn contrast: Germans treated film as art or culture while Americans baptized it as commercial enterprise. American slapstick did not deserve classification as comedy as Germans understood the term.[15]

The leap from comic styles to national mentalities served, as in the past, to put forward a cinematic agenda. Maxim Ziese, lead critic for Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, articulated this emphatically in response to Buster Keaton’s The Navigator. Although Ziese conceded that the audience of UFA-Palast thoroughly enjoyed Keaton’s peculiar blend of comic ingredients, he took pains to point out that slapstick was not art because it involved neither thought nor human feeling. It amounted only to a technologically mediated way of seeing the world.[16] Ziese thereby smuggled into his review a barely disguised version of a rationale popular among intransigent opponents of the cinema: a medium dependent on mechanical means of reproduction could not produce art. That someone who took film seriously enough to criticize it should borrow this argument suggests that slapstick occasioned a hostile reflex by drawing attention to the technological dimensions of the medium.[17] Although that reflex did not dominate critical opinion, it had more than curiosity value, for it is detectable in less blatant forms even among those who endorsed Hollywood’s comic formula. The latter differed in gleaning from these films a much-needed corrective to domestic approaches, but their admiration was still largely rooted in presuppositions shared by slapstick’s opponents. Ironically, slapstick was enlisted to affirm very traditional artistic standards.

As already noted, initial critical approval of slapstick shorts presupposed willingness to laugh along with German audiences. As described by Kurt Pinthus, that willingness came from a conversion experience in which tears of laughter suspended scepticism and critical impulses.[18] Common to it was appreciation for comic moments which domestic producers did not offer. Heinz Pol, chief critic for the Vossische Zeitung, related his own and audience enthusiasm to Hollywood’s ability to provide truly funny entertainment in the midst of Germany’s depressing postwar circumstances.[19] Others tied enjoyment less to slapstick’s therapeutic benefits in difficult times than to its compensation for deficiencies in the German sense of humor. Paul Medina interpreted the slapstick craze as a sign of an undeveloped and thus almost insatiable national appetite for comedy. “From a very uncultivated disposition toward humor extremely greedy for it, we cannot get enough of it. We want a ton of whipping cream immediately. Thus it happens that we overstuff ourselves earlier than is necessary.”[20] Exploring these assumptions Paul Ickes and Joseph Aubinger confronted the apparent inability of domestic filmmakers to satisfy the national appetite. The key to slapstick was a playful attitude toward a hostile world. Germans lacked that key, for despite numerous reasons to feel tricked and cheated, they perceived their situation so fatalistically that they failed to capitalize on its comic possibilities. American slapstick exposed Germans’ inability to see themselves and find laughter in the less admirable of their national foibles.

Betrayed politically, cheated by the Treaty of Versailles and the victim of an unstable currency, Germans desperately needed laughter but seemed incapable of creating it. Slapstick movies therefore did for Germany what it could not do for itself.We are too self-tormenting, too learned, too conscientious, too fussy, too much in need of censorship and mothering. We are passable cobblers of drama, masterminds of all possible and impossible areas; jacks-of-all-trades but masters of none; we don’t know how to laugh at our own folly.[21]

Praise for the capacity of slapstick to satisfy moviegoers and provide a filmic recipe for which German producers had scant counterpart parallels closely the more appreciative evaluations of the early serialized imports. Just as the American frontier offered a venue for chases, fights and daredevilry that domestic filmmakers could not duplicate, so Hollywood provided a home for gags and stunts matched by no other film industry. Yet here the parallel ends. Critics acknowledged the demand for westerns, but they showed relatively little interest in exploring its social or cultural relevance. Slapstick, by contrast, provoked critical attention and with it a striking metamorphosis of opinion. By middecade it had become the source of searching reflections on man, machine and the modern age. It offered heuristic as well as entertainment value, material for rumination as well as diversion, interest for cultured as well as general audiences. More by accident than design, American film humor promised redemption from a number of interlocking cultural impasses.

| • | • | • |

The outstanding exception to the generalization that slapstick initially merited only brief asides or applause for generating laughter was the critical response of Hans Siemsen. Even before the slapstick shorts appeared in German cinemas, Siemsen indicated acquaintance with Chaplin from travel abroad and began to use him as a model for German filmmakers. In 1922 he wrote a series of articles on Chaplin in Die Weltbühne which subsequently appeared as a slim monograph.[22] One of these was dedicated to the political dimension of his work and laid the foundation for his later reputation as a friend of the working classes. Without fixing a party political label on him Siemsen insisted that he was a revolutionary because he consistently challenged the established social order. In his role as a social outcast he exposed as hollow and inhuman the values defended by his betters.[23] The bulk of Siemsen’s commentary on Chaplin focused, however, on his personal discovery and exploitation of the laws of the medium. As author, performer and director, Chaplin reunited creative roles which had become fragmented by the specialization and rationalization of the motion picture industry. He therefore earned the title of the first authentic artist of the cinema. Both on these grounds, and because Chaplin championed universal human values, Siemsen assigned his work epochal significance.[24]

Siemsen’s fulsome praise of Chaplin, while derivative in an international context, pioneered philosophical reflections on the man and his work in Germany.[25] Simultaneously, slapstick moved into the mainstream of German debates on the artistic boundaries of cinema and the role of Hollywood in domestic culture. Its assimilation reflected, on the one hand, the stylistic refinement and growing sophistication of the genre as feature film and, on the other hand, evolution in the conditions of its German reception. Until late 1923 German moviegoers’ experience of slapstick was restricted to shorts made during or immediately following the war. Only from the end of the great inflation, with the release of The Kid, did feature-length comedies by the outstanding trio of Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton appear on the market. While the import of shorts continued unabated, as did the practice of using them to create entire theater programs, the release of the comic features proved timely. Just as Hollywood’s reputation suffered a relapse, its comic specialty assumed characteristics that encouraged serious treatment from German critics.[26] The feature-length works smoothed some of the coarser features of the genre and boasted narrational and compositional sophistication which gave them prominence disproportionate to their numbers. In retrospect it could be argued that the mature feature films transcended the boundaries of slapstick, becoming less frenetic in tempo, less chaotic in organization and more reflective in style. Granted these differences, however, contemporaries generally treated the feature films as extensions of the early shorts.[27]

Maturation from Beiprogramm to feature marked a timely shift in orientation, but one met more than halfway by an independent pursuit on the side of its recipients to make sense out of nonsense. As the quintessentially American, un-German form of humor became a fixture in cinema programs, the challenge to critics to decipher its relevance for the German condition became sharper.[28] In the first encounter, German commentators puzzled over how to read creative works indifferent to the usual canons of narrative structure and causality. Attention focused primarily on two distinctive features of the genre: meticulous precision in execution and filmic fantasy. On more than one occasion Roland Schacht isolated the discrepancy between the American and German work ethic as the primary reason for the international appeal of slapstick and the relatively limited interest in German film humor. He judged Harold Lloyd, for example, a second- or third-rate performer, but believed he came by his fame honestly because he outworked his competitors in Germany. Lloyd and other American comedians expended incalculable effort on each scene for just a few seconds of laughter.[29] Inseparable from devotion to the craft was imaginative richness. In some instances this left German experts stunned or overwhelmed. Their stupefaction is nicely captured in a comment by Kurt Pinthus on Harold Lloyds’s A Sailor-Made Man: it contained such an abundance of gags that ten German companies could each make ten comedies from them, any one of which would be funnier than any ten German comedies put together.[30]

While diligence and creativity prompted widespread admiration, narrative substance and structure were relegated to subordinate status. More clearly than in any other genre the “how” took precedence over the “what.” Meager or completely chaotic plots proved no obstacle to captivating and successful motion pictures. Taken to the extreme this meant that total absence of conventional plot development was no obstacle to excellence.[31] Yet consistent though it was to de-emphasize narrational qualities when praising slapstick for other virtues, the broader significance of this American comic specialty was not so conveniently settled. By presenting the extreme case of form over content, of the “how” outweighing the “what,” of technique and the technical overpowering logic or coherence, of the optical dominating the cerebral, slapstick challenged ingrained beliefs. After years of effort to elevate the movies from a purely technical, juvenile amusement to an art form, experts encountered comic nonsense which inferred that film obeyed other imperatives. In this way slapstick invited reordering of cinematic priorities.[32]

Discourse on the slapstick challenge fractured in three main directions. The first, already examined, rebelled against its purely optical, technical impulse and dismissed it as symptomatic of motion picture immaturity. This meant consigning it to motion picture history. The second, its mirror image, discarded traditional standards and deduced from slapstick new motion picture laws, thereby making it a signpost to the future. Rudolf Arnheim, like Hans Siemsen, embraced slapstick as proof that the cinema respected an optical rather than a discursive or narrational logic. With remarkable consistency he argued that in revealing the priority of visual impressions over psychological connectedness, slapstick led the field in the race to create film art.[33] The final direction paralleled the search for a third way to meet the overall threat of Americanization. It sought a blend of traditional ends and innovative means, thus borrowing from slapstick without acceptance of all its ramifications.

Pursuit of this third path meant rationalizing personal and public enjoyment of slapstick while preserving critical distance from its broader challenge. Here refusal to see the optical, technical impulse of the motion picture as a characteristic only of its infantile stage did not equal endorsement of knockabout comedy as a general cinematic model. As Rudolf Arnheim observed, despite effusive praise for Hollywood’s unique brand of humor, most filmmakers sought the realization of cinematic art via other paths. Early in the decade Hans Siemsen had asked whether viewers and experts could enjoy American sensationalism without subsequently becoming disgruntled.[34] A similar query now applied to slapstick imports. Could Germans laugh at nonsense without claiming ex post facto dissatisfaction? Siemsen and Arnheim implied affirmative answers to this question. Their colleagues, many of whom ranked slapstick highly in the cinematic hierarchy, did so only with qualifications. Careful examination reveals that their enthusiasm rested on more than captivation by “optical miracles.” Apparent conversion by American tricks and acrobatics fell far short of complete. Consistent with the criteria employed to evaluate other film types critics prized the latter too for achieving supraoptical significance. Ironically, the same impulse which initially led to slapstick’s rapid dismissal later stimulated critical reflections which allowed critics to embrace it.

Following the release of The Kid in 1923 critics began both to take slapstick seriously and to reflect self-consciously on the paradox of doing so. Kurt Pinthus began to philosophize against his will on the grounds that slapstick begged reading on more than one level: “Precisely these artistic performances, which the average person terms nonsense to begin with, ultimately lead into the greatest human and metaphysical depths.”[35] Pinthus’s discovery marked a trend which by middecade permitted Hans Siemsen to joke that his critical colleagues could disclaim their earlier obtuseness by blaming a printing error for their description of Chaplin’s work as nonsense (Unsinn) rather than profundity (Tiefsinn).[36] The same trend provoked Alfred Polgar, theater critic for Die Weltbühne, to appeal to the literati who led the Chaplin craze to drop their pretensions. Charlie had become an “attorney of the oppressed,” a “symbolic fighter” against the malice of the objective world, a “protester against global injustice.” Even his shoes and his characteristic waddle served as clues to ethical and philosophical principles. Polgar denounced the hunt for profundity in Chaplin’s films as pointless and one-sided, but he, like Pinthus, could not resist it. By denying philosophical depth to Chaplin’s dress and behavior with the argument that “their meaning lies in their meaninglessness,” he attributed broader significance to Chaplin’s suspension of conventional logic and morality.[37]

Chaplin’s apotheosis, despite the strictures of Polgar, as savior and brother to the proletariat symptomized a search for values and meaning which was not unique to the cinema. It reflected the grasping after straws of a generation convinced by war of the death of God and humankind’s inhumanity to itself. Chaplin symbolized the possibility of meaning in a world which had lost its sense of direction.[38] Yet Polgar rightly pointed to the fact that Chaplin remained a popular artist of the cinema rather than a philosopher. However exalted his position in twentieth century culture, and however much he defied classification by genre, he belonged first and foremost to the American slapstick tradition. Moreover, as Pinthus suggested, Chaplin was not the lone slapstick artist to address fundamental human issues through humor. While undoubtedly a special case, he represented a way of viewing the world which was characteristic of American film comedy. His place in Weimar culture must therefore be anchored within discourse about American cinema in general.

Set against middecade reactions to Hollywood documented in chapter four, slapstick initially won applause for what it was not. Though unique to Hollywood, it gained a grateful critical following because it differed in crucial respects from the other imports from America. Not only was the heroic posturing, moralizing and sentimentality which characterized American film dramas absent. Filmmakers mocked these otherwise obligatory dramatic devices. Favorites in this respect were takeoffs on well-known western or adventure themes or films in which animals mimed human performers (including a spoof on Douglas Fairbank’s The Thief of Bagdad performed by monkeys).[39] Most consistently praised were the pictures of Buster Keaton. Rudolf Arnheim found in Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr. a corrosive parody on movie mysteries and adventure kitsch. Roland Schacht praised Our Hospitality for hilarious mimicry of the conventional murder film. And Herbert Ihering located the laughter in Three Ages not only in the disjunction between modern customs and those of previous eras but also in Keaton’s caricature of pompous historical pictures. Critical appreciation for slapstick therefore rested on its neutralization of many offensive traits of Hollywood’s mass production.[40]

Appreciation for mockery of Hollywood’s conventions applied more broadly to slapstick’s glosses on American society and culture, or more precisely, those features of modern culture commonly associated with the United States. The vagaries of modern technology and gadgetry, current fads such as the sports craze or even movie mania, or the stifling conformism of American society appeared in slapstick films as objects of satirical dissection. Keaton’s College poked fun at the current obsession with sports; Our Hospitality destroyed the romanticism often associated with the past and mocked humankind’s worship of technology. Harold Lloyd’s For Heaven’s Sake and Keaton’s Seven Chances attacked such sacred cows as moral convention and the police.[41] In countless cases slapstick explored humankind’s ambivalent relationship to the technological marvels of their own making. In a number of instances Hollywood also engaged in the delicate exercise of satirically dissecting military heroism or war. Slapstick tore the mask off contemporary values, institutions and accepted codes of behavior.[42]

As these examples suggest, critical enthusiasm for American film comedy rested largely on its ability to mirror, if in distorted fashion, the vagaries of the real world. Bizarre though its presuppositions might be, slapstick took its point of departure from concrete, current issues, everything from the human ramifications of the postwar housing shortage to the animal-like qualities of humanity released by a large department store sale.[43] It demonstrated unparalleled facility for illuminating the human condition, particularly man’s interaction with nature or his own inventions. Roland Schacht’s apposition of American and German practice in film comedy isolated precisely this facility as the kernel of Hollywood’s success.

In this context the particular virtue of slapstick lay in its eye for fraud and insanity in inventions, institutions and morals which constituted America’s contribution to civilization. Not only did this mean that slapstick dared to explore the disjunction between life as it was and life as moral codes prescribed it, but it permitted the audience to laugh through identification with the weaknesses and sufferings of the character on the screen. To quote Schacht once again, generalizing from the comic persona of Buster Keaton:The Americans work from what everyone knows, the Germans from what they contrive. The Americans aren’t afraid to show their hero in truly ludicrous situations which arise in daily life rather than plundering old funny papers like the Germans.…Germans consider comedy a Sunday state of emergency. An otherwise sensible human being isn’t allowed to be funny. The Americans on the other hand know that comedy is only the flip side of seriousness and belongs to it organically.[44]

The American, a poor dear fellow, a complete simpleton in the hubbub of modern life, embodies suffering humanity; the German shouts in all he does: look here, how funny, how terribly funny I am. The public laughs away its sorrows at the American comedians; with the German it laughs at an individual simpleton, a freak.[45]

The dialectical relationship between nonsense and reality exercised considerable fascination for interpreters of slapstick. On the one hand these films subverted standard notions of logic, causality and probability, conjuring up a world bound only by the limits of imagination. On the other hand they offered a powerful commentary on the arbitrariness of the real world, man’s alienation from technological culture and the mentality of American society and the so-called realistic film. Critics alternately emphasized one or the other dialectical pole. Axel Eggebrecht, a leftist critic and screen author, praised Chaplin as an “insistent exposer of the real, unromantic course of life.” Felix Henseleit labeled Keaton’s short, One Week—a hilarious jab at the wonders of modern consumer-oriented enterprise (in this case a prefab home for do-it-yourselfers whose sections had become jumbled)—“a contribution to the sociology of American institutions.” The editor of Lichtbildbühne, Georg Mendel, fully conscious of the paradox of gleaning pedagogical insights from slapstick, rated Keaton’s Go West an educational film because it truthfully captured human feeling.[46]

At the opposite dialectical pole slapstick was a vehicle for escaping reality. Its function in this regard frequently found expression through parallels with the fairy tale. Alfred Polgar employed that parallel to underwrite refusal to make Chaplin the propagator of a social creed. Béla Balázs used it to explain Chaplin’s public appeal. Kurt Pinthus and Siegfried Kracauer hailed slapstick for suspending the weight of routinized, technological culture and demolishing piece by piece the unbearably regimented structure of American society. Laughter proved liberating because humankind’s ability to identify its enslavement to the machine and extrapolate ad absurdum from mechanical laws confirmed human sovereignty.[47] Buster Keaton proved the primary illustration of the dialectical relationship between other-worldliness and the modern, technologically determined imagination. As a wanderer from another realm into the real world, American-style, he created a modern fairy tale in which fact and fantasy served each other.[48]

Slapstick’s unrivaled power of illuminating the human condition made it a source of political statements congenial to the political left. Chaplin’s pictures provided the obvious quarry in this regard, not least because they offered a bridge by which leftists overcame their suspicion of the cinema as an instrument of bourgeois ideology and big business.[49] Early in the 1920s Chaplin attracted attention for his role as the conscience of an unjust society. In 1922 Kurt Tucholsky introduced Chaplin in an article which ventured beyond the physical virtuosity and tangle of stunts to social commentary. Chaplin’s work testified to the existence of a worldview and human identity radically different from that fostered by the regimented culture and society of Germany. Not least of his merits was the instruction he offered in laughter for a nation which took itself and its position far too seriously.[50] The same year Hans Siemsen explored the significance of Chaplin’s chosen persona—a vagabond struggling against an oppressive social system and state institutions. In The Immigrant Chaplin debunked the myth of personal liberty worshiped by Americans and in The Bank he desecrated the modern holy place, the vault. Siemsen read Chaplin’s iconoclasm as a much-needed corrosive to German prostration before social status and political authority.

As harmless as all these Chaplinades appear, in reality they are nothing other than a constant undermining of everything which today has reputation, office and dignity—they are a single battle against the contemporary social order.…He teaches that nothing should be taken seriously, nothing but the most straightforward human things; and that nothing should be feared.…He teaches complete, radical disrespect. God bless him! He is a revolutionary.[51]

From middecade the left acknowledged Chaplin as a political comedian, as a “friend of the working class” and thus a phenomenon which the bourgeoisie could only superficially appreciate.[52] Socialist and communist intellectuals admitted he could not be labeled to fit their specific purposes but made him an opponent of many injustices they too combated. At the very least Chaplin exposed the hypocrisy and inconsistencies of the bourgeois social order and indicated sympathy with the disadvantaged and oppressed. To some he was a “proletarian artist” if not an “artist of the proletariat,” or partisan toward the proletarian struggle even though not a party man.[53] In the socialist journal Film und Volk Gerhart Pohl expanded the scope of the discussion to include films by Keaton and Lloyd, arguing that slapstick as a genre, while not revolutionary by profession, was revolutionary by implication because it revealed apparent social absolutes to be relative values which could be changed.[54]

The left-wing tendency to politicize slapstick is a noteworthy facet of discourse on this genre, but it cannot be divorced from other levels of criticism. Slapstick could not be poured into a partisan mold because it did not belong to one social class. As leftist critics had to concede, the bourgeoisie derived as many laughs as the proletariat from these pictures and indirectly much more profit, even if it missed their social significance. Furthermore, intellectuals of differing persuasions found in slapstick artistic values which overrode political categories. While Chaplin provided ammunition for the political left, he also supplied grist for the mill of those dedicated to art as autonomous creation. These too discovered deeper meaning in comic fairy tales. What serious drama conveyed inadequately, Chaplin and his leading rivals managed to capture. Precisely in the synthesis of the fairy tale and the down-to-earth, slapstick broke through the barrier between entertainment and art.

The outstanding representative of this synthesis was Charlie Chaplin. Despite the warning from Alfred Polgar in 1924 not to fabricate momentous principles from his clowning or outfit, artists and intellectuals created a Chaplin cult, indulging otherwise frustrated hopes in paeans to his work. If these homages to Chaplin offered a common theme it was that Chaplin, more than any other contemporary filmmaker or artist, represented and championed the cause of humanity. His pictures excelled by virtue of what Hans Pander called their “human content.” Some identified this human content as his support for the mass of downtrodden and oppressed; others as his exploitation of the underlying link between the tragic and the comic; others as his transcendence of the mechanical world. All derived from this profoundly human dimension the right to label his work art. All also made Chaplin the exemplar of artistic values which antedated the motion picture, indeed which belonged by and large to a world which interwar Germans felt had been lost. Chaplin’s humanity consisted in upholding traditional values in a nontraditional world.[55]

The most striking illustration of attitudes came in response to The Gold Rush. At once pinnacle of the genre and of Chaplin’s accomplishments, The Gold Rush provoked such superlatives that critical faculties were temporarily suspended. To the extent that critics rationalized their rapture, they focused attention on Chaplin’s handling of human emotions. Herbert Ihering, whose concern for the growing discrepancy between the technical means at the filmmaker’s disposal and the goals which informed them has already been discussed, saw in The Gold Rush the creation of a human and artistic genius not enslaved by mechanical progress but able to perfect a human type with the aid of modern technology.[56] A critic for Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, R. Pabst, argued similarly that the ultimate worth of The Gold Rush resided neither in its plot, nor in its technical approach, nor in its masterful directing, but in the gripping human base on which it was conceived. Here a technical art form had captured a creative, emotional dream.[57]

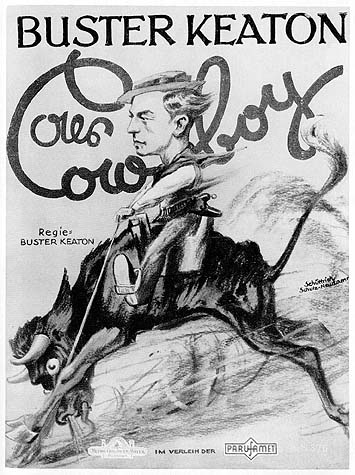

Buster Keaton in Go West, the modern antihero’s spoof on heroism in the wild west, 1926. (Photo courtesy Landesbildstelle Berlin)

Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush, symbol of an age, 1926. (Photo courtesy Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv Berlin)

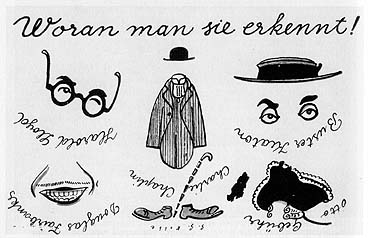

“Recognizable Features.” In this illustration of typecasting and identifiability, Holywood’s three great clowns and its leading swashbuckler crowd Germany’s screen personification of Frederick the Great, Otto Gebüauhr. Phoebus brochure, February 1926. (Photo courtesy Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv Berlin)

Nowhere did the power of this picture to synthesize cultural currents become more apparent than in its ability to forge unity between experts otherwise at loggerheads. Hans Siemsen and Willy Haas clashed sharply over critical practice but used The Gold Rush for very similar purposes. Siemsen, a long-time Chaplin fan, chased the film through Italy and Switzerland in 1925. By the Berlin premiere of February 1926 he had already seen it a dozen times. Although his enthusiasm remained undimmed, he felt it unnecessary to rehearse everything he had said in 1922, particularly now that his colleagues were echoing his sentiments. He did, however, reassert Chaplin’s epochal significance, insisting that his contribution to cinema and human development would still live long after the world war had been forgotten.[58] Willy Haas’s lengthy and equally ecstatic review of The Gold Rush used variant language to articulate very similar views. Haas had earlier, of course, entertained misgivings about Chaplin’s style.[59] With The Gold Rush he jettisoned these. Chaplin’s “strange, godless faith . . . in absurd fate,” his depiction of humankind’s inability to know or understand its fellow human beings, captured the essence of modern tragedy just as his exploration of the senseless or absurd led to discovery of comic meaning. Haas argued that this motion picture marked a historical watershed in the development of the cinema and the dawning of a new era in human history. On the first count it swept aside once and for all the controversy over whether film would ever rank as an art form. With The Gold Rush Chaplin earned the title of “the most brilliant artist alive,” challenging literature, the traditional repository of cultural leadership, to demonstrate its artistic worth. On the second and related count, The Gold Rush vaulted the cinema into the place long envisioned for it by Haas as the art form destined to overcome national boundaries and unite humankind on a global level.

We have always stated and hoped: the cinema is the great Volkskunst of a future, united world; just as the individual nation created its national anthem, its national mythology at the historical moment when it became a nation…so one day united humanity would create a completely silent and multilingual national anthem, and this national anthem could only be the cinema.

And now all at once it exists. The silent national anthem of tomorrow’s universal nation of united humans, the wordless legend of tomorrow’s modern humanity. No, more: the only art which can legitimately call itself “modern,” film art.[60]

As these grandiose projections suggest, Chaplin worship served private visions of both human and cinematic progress. For Willy Haas, Chaplin symbolized the emergence of a new world order.[61] For others, such as Kurt Tucholsky and Hans Siemsen, who were outspoken opponents of social injustices perpetuated under the Weimar Republic, his comedy was a scourge to flog the system. Tucholsky set Chaplin’s humanity over against the oppressive regimentation and callousness of contemporary Germany. Siemsen lamented the relative infrequency with which Germany received Chaplin films because his works made life bearable in a country with stultifying judicial, educational and political institutions.[62] Other critics preferred to avoid the politicization of their trade and so isolated the “endlessly human” or “truly human” quality of his films, that is, his ability to give visual form to human joy and sorrow and simultaneously produce laughter. Chaplin became all things to all people.[63]

Amidst adulation and universalizing of Chaplin’s humanity the ability of his and other slapstick films to create laughter was so much taken for granted that it tended to be forgotten. Yet diverse agendas for cultural and cinematic progress remained anchored in unrestrained amusement. It was laughter which provided the common denominator in acclaim for slapstick’s madness and sanity, fantasy and realism, melancholy and hilarity, devotion to man and exploration of machine. Hans Feld presented a useful reminder of this fact when he dismissed the questions which dominated the slapstick debate—“is it the pleasant way these slapsticks are made; is it the disarming innocence, is it a deeper instinct which recognizes and exploits human schadenfreude, or is it the confidence with which absurdity is made a principle?”—as irrelevant: “one cares less about the answer and laughs, laughs, laughs.”[64] His restatement of the position initially adopted by Kurt Pinthus points to a fundamental component of what critics called slapstick’s human content.

The burden of this chapter has been to contextualize discourse along lines suggested by Feld’s questions rather than to accept his answer uncritically. But the fact that after middecade audiences and critics continued to laugh as they had in 1921–1922 is of more than casual significance. Without enjoyment, the need to comprehend would have been much less urgent, particularly insofar as slapstick evoked responses which surprised experts. Probing for deeper meaning presupposed laughter. Rationalization of laughter was, in turn, crucial to slapstick’s appreciation by critics. A number of trade reviewers, accustomed to assessing box-office value, hinted that slapstick therefore possessed a unique advantage. Felix Henseleit groped towards a formula for salvaging artistic conventions while still endorsing Buster Keaton’s humor when he assigned Keaton’s films “intellectual class even though they [were] superb achievements technically.”[65] After viewing The General, the classic Civil War comedy, Henseleit ranked Keaton next to Chaplin for his ability to capture the “human and the all too human.” Technology had not excised the human dimension. Moreover, the fact that “everybody laughed, laughed heartily and amid tears” led Henseleit to conclude that The General appeared a “rare case where intellectuals and less intellectual persons” would see eye to eye. Both sophisticated and undemanding viewers found their expectations fulfilled.[66] Max Feige and Hans-Walther Betz drew comparable conclusions, relating the externally primitive but philosophically profound features of Keaton’s films to unusually wide box-office appeal. Keaton’s work was “perfectly gratifying for the literate as for the naive person.”[67]

Slapstick’s ability to engage viewers on both sides of the cultural divide, an achievement impressive enough to draw critical attention, underscored its contribution to human development.[68] In his review of The Gold Rush Willy Haas argued that Chaplin had perfected a universal language and indicated a basis for international understanding. In a general article which appeared several weeks later Haas developed a program based on The Gold Rush whose essence was the breakdown of the barrier between high and low cinema culture: Chaplin exploded the myth of the intrinsic incompatibility of art and business or cultivated and mass tastes.[69] Hans Siemsen developed this point even more insistently. Chaplin enthused the intellectual and artistically spoiled élite while speaking a language understood and loved by the simplest, most uncultivated workers. He also shrank the distance between them. Siemsen cited an incident in which an artist encountered his housemaid outside the cinema after seeing a Chaplin comedy. Without quite understanding why, master and maid approached one another, and though not able to converse, experienced a momentary sense of comradeship. This, in Siemsen’s opinion, was Chaplin’s ultimate achievement.

In sum, slapstick did more than offer intellectuals something to ponder while attracting a mass audience looking for laughter. It actually forged bonds between them.He destroys barriers. He makes human beings what they really always should be: human beings. He demolishes everything which prevents them from being human beings: barriers of social standing, of education, of upbringing, barriers of title, vanity, power and ignorance. This funny little clown is the greatest thing a man can be: a world improver. God bless him![70]

| • | • | • |

Siemsen, like many others, distilled from Chaplin’s screen image the meaning he hoped to find. His promotion of Chaplin from clown to world improver did not receive universal assent. Indeed, as suggested earlier in this chapter, transfiguration of Chaplin invited artistic, philosophical or political debunking. The more emphatically Chaplin, or any other slapstick artist, was made the protagonist of larger causes, even that of humanity, the more vulnerable his image became to competing agendas. This became especially apparent when Chaplin made his second visit to Berlin in 1931. Arriving in the midst of the depression, this time to popular acclaim, he became drawn into a contest of hostile cultural and political factions which no comedian or philosopher could have negotiated successfully. In a country as fragmented as Germany in the early 1930s, the synthesis he appeared to offer proved more wishful thinking than reality.[71]

This being said, critical adulation of slapstick cannot be dismissed as mere intellectual pathos. Desire to discover the secret of a successful formula, fascination with the power of anarchy in images, and obligation to account for personal captivation by “optical miracles” yielded paradoxical statements on the meaning of an apparently make-believe, nonsensical comic style. In one respect these were rationalizations of personal enjoyment born of a cultural tradition which, as Siemsen argued in respect to sensationalist films, could not approve enjoyment unless it entailed intellectual enrichment. Intellectuals did not suspend critical thought readily, especially when they appreciated stunts which should not have interested them.[72]

In slapstick critics discovered material for rumination, they received reassurance that the highly rationalized, mechanical world had not eliminated the possibility of individual creativity, and they gained relief from the miles of kitsch which otherwise crossed movie screens. Their faith in the autonomy of art, in nonutilitarian, preindustrial cultural values was reaffirmed.[73] But Chaplin and company also helped bridge the awkward divide between the ideal and the real. As a popular genre slapstick provided ammunition against artistic snobbery and unwillingness to address the public. In the formulation of Ernst Blass, it had “more to do with genuine art than many a stylish product of literature.”[74] Most significantly, it functioned as a meeting ground for the articulate and the mute masses. The latter were surely indifferent to the integrative function of these films, but the former were not. Central to the affirmation slapstick offered intellectuals was a sense of belonging to the Volk. Without daring for the most part to admit this, critics appreciated American comedy because it indicated that intellectuals could preserve their integrity and still speak to the masses. While satisfying in inimitable fashion the demands of the “realist dogmatists” discussed in the previous chapter, slapstick eased the descent of sophisticated viewers to communion with the masses. Herein lay its ultimate human value. Universal appeal meant incorporation of discriminating viewers into the broader public. As one paean to Harold Lloyd concluded: “We’re grateful to him for the laughter; he reduces us brain snobs to human beings—who has greater merit?”[75]

Notes

1. An earlier version of this chapter appeared as “Comedy as Redemption: American Slapstick in Weimar Culture,” Journal of European Studies, xvii (1987), 253–277.

2. Dr. Brann, “Vier Fox-Grotesken,” Der Film (Kritiken der Woche), 5 May 1928, p. 1.

3. On France see Shi, “Transatlantic Visions,” pp. 587–590; Richard Abel, “The Contribution of the French Literary Avant-Garde to Film Theory and Criticism (1907–1924),” Cinema Journal, 15 (1975), pp. 23–24. On Spain cf. C. Brian Morris, “Charles Chaplin’s Tryst with Spain,” Journal of Contemporary History, 18 (1983), 517–531. On England see LeMahieu, A Culture for Democracy, pp. 43–53. More generally on Chaplin as public phenomenon cf. David Robinson, Chaplin: The Mirror of Opinion (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984); David Marland, Chaplin and American Culture (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989); Timothy Lyon, Charlie Chaplin: A Guide to References and Resources (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979).

4. Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (London: The Bodley Head, 1964), pp. 285–293. There is a summary in Robinson, Chaplin: The Mirror of Opinion, pp. 52–59. Erich Burger, Charlie Chaplin. Bericht seines Lebens (Berlin: Rudolf Mosse, 1929), p. 93, mistakenly claims that Berliners had no opportunity to acquaint themselves with Chaplin’s work before his visit.

5. On the very different reception when Chaplin returned to Berlin a decade later see Arnold Hollriegel, Lichter der Großstadt (Leipzig: E. P. Tal Co., 1931); Wolfgang Gersch, Chaplin in Berlin (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1988).

6. Hans Siemsen, “Chaplin,” Die Weltbühne, 18 (1922), vol. II, pp. 367–368. Cf. the views of the French poet Cendrars cited in Willett, The New Sobriety, p. 33.

7. Karl Lütge, “Das deutsche Lustspiel in Vergangenheit und Zukunft,” Kinematograph, 19 February 1922; Illustrierte Film-Woche, no. 30, 1922. Cf. Der Film, 16 October 1921, p. 45; “Chaplin im Warenhaus,” Kinematograp, 18 December 1921; “Filmschau,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 1, 1 January 1922.

8. See Der Film, 16 October 1921, p. 45; Kinematograph, 18 December 1921; Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 1, 1 January 1922, and no. 389, 20 August 1922, p. 7; Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 12 January 1923, p. 6. On Harry Sweet cf. Berliner Tageblatt, 5 August 1923.

9. M.Z., “Kinoides,” Der Kritiker, 4 (June 1922), 14.

10. Haas, “Einwände gegen Chaplin,” Das Tagebuch, 3 (1922), 1073–1074. Cf. Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 329, 16 July 1922, p. 8. Similar opinions are cited in Morris, “Charles Chaplin’s Tryst with Spain,” p. 519.

11. Contrary to Monaco, Cinema and Society, p. 74. Cf. reports from Düsseldorf and Leipzig in “Aus der Praxis,” Kinematograph, 30 October 1921; “Chaplin als Sträfling,” Film-Kurier, 12 November 1921; H.W. (Hans Wollenberg), “Die Chaplin-Quelle,” Lichtbildbühne, 15 October 1921, p. 44.

12. For a polemical formulation of this point see K. Lütge, “Das deutsche Lustspiel in Vergangenheit und Zukunft,” Kinematograph, 19 February 1922.

13. Cf. the introduction to Klaus Kreimeier (ed.), Zeitgenosse Chaplin (Berlin: Oberbaum Verlag, 1978) for a more politicized reading.

14. Cf. “Buster Keaton als Cowboy,” Kinematograph, 26 December 1926, p. 26; Hans Wollenberg, “Der Sportstudent,” Lichtbildbühne, 9 November 1926, p. 2; Dr. Neulander, “Filmchronik,” Der Kritiker, 8 (February 1926), 32; “Ben Akiba hat gelogen,” Vorwärts, no. 433, 13 September 1925; Heinz Pol on Harold Lloyd in Vossische Zeitung, no. 57, 7 March 1926.

15. Paul Sorgenfrei, “Der Faktor ‘Publikum’ im Rechenexempel des Kinos,” Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 23 April 1926, p. 1; S-r. (Albert Schneider), “Mädchenscheu,” Der Film, 7 March 1926, p. 19; Hermann Bräutigam, “Woran wir kranken!” Reichsfilmblatt, 28 March 1925, pp. 14–15, who claimed Lloyd was the only American comedian still popular in Germany; B.S., “Humor im Film,” Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 6 August 1926, pp. 2–3.

16. maxim (Maxim Ziese), “Buster Keaton, der Matrose,” Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 13, 9 January 1926.

17. Cf. Severin Rüttgers, “Kultur, Kunst und Film,” Deutsches Volkstum, 7 (1925), 359–365; Hans Steckner,“Kunst und Kino,” Die Tat, 16 (1924), pp. 470–473.

18. In this case upon first encounter with a Chaplin short: Pinthus, “Sehenswerte Filme,” Das Tagebuch, 2 (1921), 1288–1289.

19. Heinz Pol, “Filmschau,” Vossische Zeitung, no. 335, 18 July 1922, embraced Chaplin as therapeutic, as the “only right fare in these times when one would like to crawl away and hide in one’s gloom.” Cf. Pinthus, “Sehenswerte Filme,” p. 1289.

20. “Fatty-Lustspiele,” Kinematograph, 22 July 1923, p. 9. Cf. Film-Kurier, 11 October 1921 and 25 November 1921 for suggestions that German film humor seemed moribund by contrast.

21. Joseph Aubinger, “Die geteilte Wohnung,” Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 9 November 1923, p. 3. Paul Ickes, “Grotesken,” Film-Kurier, 5 December 1922.

22. Hans Siemsen, Charlie Chaplin (Leipzig: Feuer-Verlag, 1924). Contrary to Lyons, Charles Chaplin, p. 99, this is not a “standard biography.” Later books in Chaplin’s honor are L. A. Hermann, Chaplin’s wunderbarer Aufstieg (Berlin: Otto Dreyer, n.d.); Erich Burger, Charlie Chaplin. Bericht seines Lebens.

23. Siemsen, “Chaplin—Der Politiker,” Die Weltbühne, 18 (1922), vol. II, pp. 415–416. Several months after Chaplin visited Berlin Siemsen reported that the comedian had toured the working-class districts rather than the fashionable Kurfürstendamm: “Chaplin,” Der Querschnitt, 1 (1921), 213–214.

24. See the other articles in the series in Die Weltbühne, 18 (1922), vol. II, pp. 367–368; 385–387; 447–448; 473–474.

25. A partial exception by Claire Goll, then resident in Paris, is “Amerikanisches Kino,” Die neue Schaubühne, 2 (1920), 164–165. Cf. the recent analysis by Sabine Hake, “Chaplin Reception in Weimar Germany,” New German Critique, no. 51 (1990), 87–111; here pp. 88–89.

26. Strictly speaking, the first feature release of this type was The Kid (1921), which premiered in Berlin in late November 1923. The import of shorts grew rather than diminished; features remained a small minority of the total.

27. See the summary by Wolfgang Petzet, “Der Stand des Weltfilms,” Der Kunstwart, 42 (1928), 116–121, here p. 117.

28. The perception of otherness took root with the Fox releases of 1922. It occasionally included regret that Germany failed to imitate. Cf. Walter Thielemann, “Neue Fox-Filme,” Reichsfilmblatt, 15 December 1923, p. 16; hfr. (Heinrich Fraenkel), “Ein Wolkenkratzer der Filmkomik,” Lichtbildbühne, 3 May 1924, p. 28; Aros (Rosenthal), “Harold Lloyd im UFA-Palast,” Film-Echo, 2 November 1925; R.O. (R. Otto), “Reprisen amerikanischer Grotesken,” Film-Kurier, 28 June 1927.

29. See Schacht’s remarks on Safety Last in Das blaue Heft, 5 (1 June 1924), 91–92, and Girl Shy in ibid., 8 (1926), 197–198. The contrast between Buster Keaton and Reinhold Schünzel is in ibid., 9 (1927), 566–567; 647. Cf. H.A. (Hans Alsen), “Fox-Grotesken,” 8 UhrAbendblatt, 11 July 1925.

30. Das Tagebuch, 6 (1925), 106. Also see F.S. (Fritz Scharf), “Um Himmelswillen,” Vorwärts, no. 561, 27 November 1927; Hans Pander in Der Bildwart, 5 (1927), 548; 6 (1928), 316; 7 (1929), 284.

31. hfr. (Heinrich Fraenkel), “Ein Wolkenkratzer der Filmkomik,” Lichtbildbühne, 3 May 1924, p. 28. Cf. “Der neue Harold Lloyd,” Kinematograph, 8 November 1925, p. 20; Hans Frey, “Film,” Der Kritiker, 9 (March 1927), 38; Hassreiter, “Harolds liebe Schwiegermutter,” Der Film, 3 November 1928, p. 177; “Eine Spitzenleistung in der Filmgroteske,” Reichsfilmblatt, 3 May 1924, pp. 12–13; s-r. (Albert Schneider), “Der General,” Film-Journal, 1 April 1927.

32. For a concise interpretation of contemporary artistic expectations see Elsaesser, “German Silent Cinema: Social Mobility and the Fantastic.”

33. Rudolph Arnheim, “Film,” Das Stachelschwein, 3 (August 1927), 50. Cf. the earlier argument of Willi Wolfradt, “Kino,” Das Kunstblatt, no. 11/12, 1923, pp. 358–360.

34. Die Weltbühne, 17 (1921), vol. II, 219.

35. Kurt Pinthus, “Film,” Das Tagebuch, 5 (1924), 645, commenting here on Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last.

36. Hans Siemsen, “Goldrausch,” Die Weltbühne, 22 (1926), vol. I, p. 391.

37. Alfred Polgar, “Chaplin,” Die Weltbühne, 20 (1924), vol. II, pp. 28–29. Cf. his “Amerikanischer Groteskfilm,” Berliner Tageblatt, 16 July 1924; Pinthus, “Vom deutschen, amerikanischen und schwedischen Film,” Kulturwille, 1 November 1925, in Pinthus Folio, Marbach. For recent strictures on intellectual rhapsodies cf. John McCabe, Charlie Chaplin (New York: Doubleday, 1978), pp. ix–x; Robinson, Chaplin: The Mirror of Opinion, pp. vi–viii.

38. Cf. Wilfried Wiegand (ed.), Über Chaplin (Zurich: Diogenes, 1978), pp. 15–18.

39. Use of animals for “dramatic” films was in any case an American specialty. One need only contemplate Madame Dubarry handled in this fashion in Germany to indicate the measure of irreverence which such a picture displayed. See Der Film, 1 July 1927, p. 12.

40. See Arnheim’s remarks in Das Stachelschwein, 2, 20, (1925), 46–47. Cf. Felix Henseleit in Reichsfilmblatt, 30 May 1925, p. 39: “With his refreshing humor he uproots movie kitsch, a movie kitsch which has been tolerated for decades and almost gained recognition.” Schacht in Das blaue Heft, 6 (1925), 189. Ihering, Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. II, pp. 497–498; Kurt Pinthus on Keaton’s The Navigator in Das Tagebuch, 7 (1926), 73–74.

41. “Buster Keaton der Student,” Film-Journal, 23 October 1927: “Insofar as slapstick is perceived as deliberate parody of real life, this film is Buster Keaton’s best.” Cf. rth. (Joseph Roth), “Filme,” Frankfurter Zeitung, no. 103, 8 February 1925; Das blaue Heft, 6 (1925), 189–190; “Um Himmelswillen,” Vorwärts, no. 561, 27 November 1927; Lichtbildbühne, 3 July 1926, p. 19.

42. Keaton’s The General was both lauded for exposing the absurdity of war and heroics and criticized for failure to denounce war consistently. Cf. Kurt Pinthus, “Nochmals: Buster Keaton,” Das Tagebuch, 8 (1927), 597; Ihering, Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. II, pp. 532–534; Wolf Zucker, “Der General,” Die Weltbühne, 23 (1927), vol. I, pp. 602–603. Harold Lloyd’s Why Worry? became a powerful, if perhaps unintentional antimilitarist picture: see “1000:1—Harold Lloyd,” Vorwärts, no. 517, 1 November 1925.

43. -l. (Walter Kaul?), “Fox-Grotesken,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 229, 17 May 1925, p. 6. Remy Hardt, “Ausgerechnet Wolkenkratzer,” Der Kritiker, 6 (May/June 1924), 15–16, praised the early sections of this film for their “clever, almost ingenious observation of the things of life.”

44. See Das blaue Heft, 6 (1924), 100–103; here pp. 101–102. Cf. remarks of Hans Spielhofer in Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 12 March 1926, p. 4.

45. Das blaue Heft, 6 (1925), 519. Cf. Schacht’s “Buster Keaton als Matrose,” B.Z. am Mittag, 5 January 1926; Der Kunstwart, 40 (1927), 274.

46. Eggebrecht’s comments are in Die Weltbühne, 22 (1926), vol. I, p. 350. Cf. Felix Henseleit, “Buster Keatons erste Flitterwoche,” Reichsfilmblatt, 21 February 1925, p. 40; Dr. M-l. (Georg Mendel), “Buster Keaton, der Cowboy,” Lichtbildbühne, 22 December 1926, pp. 3–4.; E.K., “Ben Akiba hat gelogen,” Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 430, 12 September 1925; m., “Fox-Grotesken,” Film-Kurier, 11 July 1925 and 14 August 1925; Hanns Brodnitz, “Der Film am Scheideweg,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 357, 2 August 1925, p. 6.

47. See Pinthus’s “Lustspiel-Grotesken,” Das Tagebuch, 5 (1924), 1007–1008; and his review of Keaton’s The Navigator, ibid., 7 (1926), 73–74. Cf. Kracauer Folio, Marbach, for articles from Frankfurter Zeitung: no. 35, 24 February 1924; no. 44, 9 March 1924; no. 14, 29 January 1926; no. 90, 24 July 1926; no. 142, 22 December 1926. Also see W.H. (Willy Haas), “Von Tanzgirls, Lausbuben und dem Kater Felix,” Film-Kurier, 31 July 1926, and “Fox-Grotesken,” Film-Kurier, 25 June 1927.

48. Cf. “Der Student,” Vorwärts, no. 502, 23 October 1927; H. W-g. (Hans Wollenberg), “Grotesken im Capitol,” Lichtbildbühne, 28 June 1927.

49. For general perspectives see Kinter, Arbeiterbewegung und Film; Bert Hogenkamp, “The Proletarian Cinema and the Weimar Republic: A comment,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, i (1982), 177–179; Murray, Film and the German Left in the Weimar Republic.

50. “He manages to make other people [look] ridiculous with his appearance alone. He only has to make an appearance…and all surroundings are suddenly wrong and he is right and the whole world has become ridiculous.…And he shows how ludicrous it is to be a grown-up man who takes himself seriously.” Kurt Tucholsky, “Der berühmteste Mann der Welt,” in his Gesammelte Werke (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1960), vol. I, pp. 1004–1007, here p. 1006. This article first appeared in Prager Tageblatt in July 1922. Cf. his review of The Kid in Die Weltbühne, 19 (1923), vol. II, pp. 564–566.

51. Siemsen, “Chaplin-Der Politiker,” Die Weltbühne, 18 (1922), vol. II, pp. 415–416.

52. See Kreimeier (ed.), Zeitgenosse Chaplins, pp. 10–13, and “Erobert den Film”: Proletariat und Film in der Weimarer Republik (Berlin: Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, 1977), pp. 25–26.

53. Cf. T. K. Fodor, “Soziologie der Groteske,” Arbeiterbühne und Film, no. 7 (1930), 26–28; Mersus, “St. Charlie oder Ein Chaplin-Film, der nie gedreht wird,” ibid., no. 4 (1931), 30–32; “Die Rote Fahne bei Chaplin,” Die Rote Fahne, 3 March 1931; O. Biha, “Zeitschau der Kulturbarbarei,” Die Linkskurve, no. 4 (1931), 1–5. All are reproduced in Kreimeier (ed.), Zeitgenosse Chaplins, pp. 87–102.

54. Gerhart Pohl, “Grotesk-Filme,” Film und Volk, no. 7 (1929), 12–15. On the politics of Chaplin’s visit in 1931 see Gersch, Chaplin in Berlin, especially pp. 120ff.

55. Pander’s review of “Zirkus,” Der Bildwart, 6 (1928), 246–247. Pander defined this “human content” through Chaplin’s film persona—an outsider in a hostile world who survived in spite of himself. Pinthus’s “Amerikanische Filmkomiker” in Pinthus Folio, Marbach (1926). For adulation of Chaplin distinguished by revulsion toward almost everything else associated with the cinema see Gerhard Ausleger, Charlie Chaplin (Hamburg: Pfadweiser Verlag, 1924). Cf. Hake, “Chaplin Reception in Weimar Germany,” pp. 92–93.

56. Ihering, Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. II, pp. 514–515.

57. Dr. R.P. (R. Pabst), “Goldrausch,” Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 20 August 1926, p. 3. Cf. Schacht’s views in Das blaue Heft, 8 (1926), 144–145; Der Kunstwart, 39 (1926), 392; Kracauer’s review in Kracauer Folio, Marbach, no. 127, 6 November 1926. Cf. Ausleger, Charlie Chaplin, p. 25, who labeled The Kid a “social work of art—not a socialist one. That would mean imputing to it a fixed purposefulness. For that Charlie Chaplin is too human.”

58. Siemsen, “Goldrausch,” Die Weltbühne, 22 (1926), vol. I, 390–392.

59. See note 10 above.

60. Haas, “Goldrausch,” Film-Kurier, 17 February 1926.

61. Cf. Gerhart Pohl, “Charlie Chaplin: Ein Symptom für die amerikanische Kulturdämmerung,” Die Glocke, 11 (1925), 406–408. Pohl did not see Chaplin as “the epitome of what was wrong with the movies” (Beck, Germany Rediscovers America, p. 164), but as a genius who had invented the formula which would make America a cultural force via cinema. Cf. his “Grotesk-Filme,” Film und Volk, no. 7 (August/September, 1929), pp. 12–15. For an opinion resembling the one Beck credits to Pohl see Wilhelm Michel, “Chaplin, der Held des Untermenschlichen,” Der Kunstwart, 41 (1928), 126–128.

62. Peter Panter (Kurt Tucholsky), “The Kid,” Die Weltbühne, 19 (1923), vol. II, pp. 564–566. Siemsen, “So kommt man an den Suff,” Die Weltbühne, 21 (1925), vol. II, pp. 62–63.

63. This is nicely illustrated by the censorship decision to lift the restriction on The Kid as suitable for adults only because of the overriding element of human affection it displayed: DIFF-FP, 7 November 1923; DIFF-OP, 8 November 1923. See R.K. (Rudolf Kurtz), “Zirkus,” Lichtbildbühne, 8 February 1928. Cf. Shi, “Transatlantic Visions,” pp. 587–590; Hake, “Chaplin Reception in Weimar Germany,” p. 91.

64. Hans Feld, “Lache mit,” Film-Kurier, 15 December 1927.

65. Henseleit, “Sherlock Holmes jr.,” Reichsfilmblatt, 30 May 1925, p. 39.

66. F. H-t. (Henseleit), “Der General,” ibid., 9 April 1927, p. 37.

67. Max Feige, “Der Mann mit den 1000 Bräuten,” Der Film, July 1926, p. 18. Hans-Walther Betz, “Buster Keaton, der Student,” Der Film (Kritiken der Woche), 22 October 1927, p. 4.

68. Cf. English intellectual opinion cited in LeMahieu, A Culture for Democracy, p. 115.

69. Haas, “Unser Kronzeuge,” Film-Kurier, 15 March 1926.

70. Siemsen, “Chaplin,” Die Weltbühne, 18 (1922), vol. II, pp. 473–474.

71. For a detailed examination of Chaplin’s visit, focused on the German public sphere, see Gersch, Chaplin in Berlin. Hake, “Chaplin Reception in Weimar Germany,” pp. 97–99, emphasizes the cultural ambiguity of Chaplin’s image.

72. Siemsen, “Deutsch-amerikanischer Filmkrieg,” Die Weltbühne, 17 (1921), vol. II, pp. 219–222; Rauol Sobel and David Francis, Chaplin: Genesis of a Clown (London: Quartet Books, 1977), p. 139.

73. Cf. Kaes, Kino-Debatte, pp. 12–15; Heller, Literarische Intelligenz und Film, pp. 199–200; Fritz Usinger, “Charlie Chaplin und die Bedeutung des Grotesken in unserer Zeit,” Der Literat, 20, 1 (1978), 1–2.

74. Ernst Blass, “Harold Lloyds ‘Mädchenscheu’,” Berliner Tageblatt, no. 112, 7 March 1926.

75. -ma. (Maxim Ziese), “Um Himmelswillen: Harold Lloyd!” Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 553, 26 November 1927. Cf. the earlier argument of eu. (Erich Hamburger?) in Berliner Tageblatt, 17 December 1922.