5. Morality and Mortality

Alcoholism, Syphilis, and the “Rural Exodus” in the War on Tuberculosis

We must…seek out and incriminate…the two other causes of death that cling to our society’s flanks, syphilis and alcoholism—those two Fates that join together with tuberculosis to form a trio far more terrifying than that of ancient mythology.

Incriminating syphilis and alcoholism along with tuberculosis as a, in Letulle’s words, “terrifying trio” was the third major strand of the dominant etiology and a key strategic maneuver in the War on Tuberculosis. It was through this trio that moral depravity came to be considered at the turn of the century, along with slum housing and contact with microbes, a principal causal factor in the spread of tuberculosis. In 1905, Louis Rénon, a professor at the Paris Faculté de médecine, published a book entitled The Diseases of the People: Venereal Disease, Alcoholism, Tuberculosis.[1] This thorough investigation of both the medical and social dimensions of the three great “scourges” of modern life left no doubt that there was a connection among the three—a connection that threatened the moral and physical well-being of France. At the center of the problem, embodying the concerted assault of alcoholism, syphilis, and tuberculosis, lay the cabaret[2] and its associated evil, prostitution.

Letulle and Rénon were by no means alone in perceiving this triple threat. From approximately the mid-1880s until World War I, medical and governmental authorities in France proclaimed frequently and forcefully certain interrelationships among alcoholism, syphilis, and tuberculosis and, in mobilizing against them, articulated a view of French society in danger of biological and moral decline. The connections they perceived among the three diseases illustrate not only certain currents in French medical science at the time but also powerful tensions and fears at work within French society as a whole. Moreover, like other aspects of the dominant etiology of tuberculosis around the turn of the century, the linkage of these three scourges appropriated and updated some much older ideas about the disease’s causes. Vice and heredity in particular—like overcrowding and bourgeois disgust with working-class living conditions—were carried over from the pre-germ theory era into the social etiologies of the Belle Epoque but infused with slightly different meanings. Earlier vague formulations concerning “vice” or “excesses” developed into denunciations of specific transgressions (chiefly, alcoholism and prostitution) and were localized in dangerous spaces such as the cabaret. Meanwhile, age-old ideas about the heredity of tuberculosis that were primarily backward-looking (that is, explaining the origins of a given case) became, amid fears of degeneration, urgent and forward-looking, warning of dire consequences in future generations.

Examining the moral dimension of etiology, or of attitudes toward health and disease in general, means confronting the elusive boundaries of “morality” itself. The ever-shifting categories “moral” and “immoral” are neither absolute nor immutable, and take on the qualities of different societies in different times and places. One doctor’s perspective on the connection between alcoholism and tuberculosis may offer a glimpse at what “morality” encompassed in France at the turn of the century. In the course of denouncing drunkenness and revolutionary politics among workers, Dr. Henri Triboulet told his audience at the International Tuberculosis Congress in Paris in 1905, “Let us add to our national motto these three terms, which will never disgrace it: cleanliness, sobriety, prosperity [propreté, sobriété, prospérité].”[3] This proposed revision of national identity (to supplement “liberty, equality, fraternity”) arose out of a specific configuration of anxieties, notably including fears of revolution and demographic decline. In this context, “morality” seems to have denoted principally a combination of the following qualities: moderation (especially in alcohol consumption and sexual activity); a stable and clean household consisting of a monogamous husband and wife with children; and hard work. The absence of these qualities was blamed for various social pathologies, and tuberculosis was prominent among them.

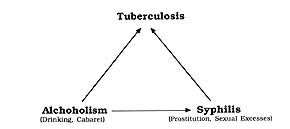

In its most basic form, this segment of the dominant etiology took a triangular shape, contending that both alcoholism and syphilis caused (or contributed to the prevalence of) tuberculosis. In its individual manifestations, this argument was usually made with respect to the effect on tuberculosis of either alcoholism or syphilis—in effect, filling in one or the other of two sides of the triangle, with tuberculosis as the nexus—but occasionally all three scourges were linked in a single text or intervention. Causal relationships—or “morbid associations,” in the words of one doctor—were most often expressed in terms of predisposition to tuberculosis, using metaphorical language concerning the quality of a “soil” or “terrain” and its receptivity to a “seed.” Typically, the full link expressed itself along the following lines: a certain number of patients, previously alcoholic (or syphilitic), had developed tuberculosis; this evidence led to the conclusion that alcoholism (or syphilis) predisposed its victims to tuberculosis; therefore, the medical fight against tuberculosis must begin with a social fight against alcoholism (or syphilis), specifically with a regulatory crackdown against cabarets (prostitution).

9. The moral etiology of tuberculosis (arrows indicate causal relations).

At issue here is not whether in fact alcoholism or syphilis had an etiological effect on or an epidemiological correlation with tuberculosis.[4] Rather, it is the type of evidence in use at the time and how it was used that are of interest. The perception of a connection, rather than the medical “truth” of the connection, is the relevant fact here. The ways in which the connection was perceived, expressed, and portrayed, the conclusions that were drawn from the perceived association, and the political and social implications contained in its expression offer greater opportunities for meaningful analysis than would a truly “scientific” historical epidemiology.

Perceived connections among the three diseases certainly did not (alone) cause perceptions of national decline. Rather, both the two-way and three-way “morbid associations” served as avenues through which anxiety was expressed and reinforced certain opinions about what constituted immoral and dangerous behavior in society. The associations deserve special attention for two major reasons. First, they established a moral etiology of tuberculosis, France’s leading killer, and thus persuasively linked behavior with disease, morality with mortality. Second, the connections consolidated seemingly separate phenomena into a generalized syndrome of national decline and constituted a means of expressing fear of such decline in medical—hence, objective and scientific—terms. Moreover, in doing so they justified surveillance of cabarets and prostitutes, useful targets for blame in their embodiment of certain types of antisocial behavior. Concern about prostitution and cabarets predated the alcoholism–syphilis–tuberculosis connections, but these connections both intensified the concern and integrated it into a broad diagnosis of French moral and physical decline.

The notion of “degeneration,” as applied to societies’ physical and moral well-being, was widespread throughout late nineteenth-century Europe.[5] In France, however, it fused with the continuing anxiety over low birth rates and demographic decline—particularly in relation to Germany and Great Britain—and fashioned a peculiarly French anxiety of national decline. The tuberculosis–alcoholism–syphilis triangle aptly expressed the degeneration paradigm; tuberculosis, the nation’s leading cause of death, was the crucial link in connecting that paradigm to the French demographic decline.

| • | • | • |

Prelude to Moral Decay: The “Rural Exodus” and Its Role in Tuberculosis

In his two books on the population of Paris in the early nineteenth century, Chevalier painted a fearsome picture of a city under siege from its own poverty-ridden underbelly. Respectable Parisians recoiled in horror at the sight of the “dangerous classes,” the ill-fed, ill-housed proletariat and Lumpenproletariat that spread crime and disease throughout the city. Chevalier emphasized the provincial origins of the desperate new Parisian poor and cited rural migration to the capital as the most salient factor—numerically and socially—in the city’s nineteenth-century growth.[6]

But these migrants, Chevalier’s early- and mid-century “dangerous classes,” were dangerous (or perceived to be so) because of what they represented to individual bourgeois observers (crime, contagion) or to the city’s public order (unrest). Theirs was a local menace. By 1900, the menace was a national one: less visceral perhaps, but on a much larger scale. The last half of the nineteenth century was certainly a period of substantial rural-urban migration. At the peak of the exodus in the late 1870s, up to 170,000 people per year left the French countryside for the city; in the late 1890s, the figure rose again as high as 130,000 per year. While the population of the Seine, the department that consisted of Paris and its suburbs, increased 87 percent between 1872 and 1911 (from 2.2 million to 4.2 million), many rural departments lost one-fifth of their inhabitants during that time, led by the Lot with a decline of 27 percent.[7]

But these statistics reveal less than do the contemporary perceptions of desertion and loss. In the minds of many observers, rural-urban migration threatened nothing less than France’s demographic, sanitary, and moral survival. Concern over the “rural exodus” expressed several different strands of anxiety at once. It did not appear to help France’s demographic emergency to have legions of young peasants forgo starting a family in favor of working in the city, where high death rates awaited them. As will be shown below, rural-urban migrants were thought to be more susceptible to deadly diseases such as tuberculosis and to play a key role in spreading them in both the city and the village back home. Furthermore, the morally pure and purely French lifestyle of the countryside, la France profonde, seemed to be dying out, abandoned by those whose duty it was to preserve it for the future. Similarly, the deserters from the farms and fields seemed to be swelling the ranks of customers in the cities’ cabarets and brothels, hastening the nation’s moral downfall.

Continual recapitulation of one particular narrative theme characterized discussion of the rural exodus from the 1890s on: a young man or woman, disillusioned with life on the farm and seeking wealth or opportunity, leaves the village for the big city; once there, the dreams turn to dust, and the dreamer sinks into poverty, immorality, crime or prostitution, and disease. It was a familiar literary motif, and its element of tragic inevitability lent it considerable evocative power. The key to the nationalist/political resonance of this theme was not only its familiarity but—particularly among the doctors, hygienists, and government officials addressing the tuberculosis problem—the extrapolation of the theme from the individual to nation. When the fate of France itself was at stake, the personal became political, the tragedy became a national one, and inaction seemed unthinkable.

A 1908 medical thesis offered a fairly typical view, through one of the classic core narratives,[8] of the rural exodus and its relation to tuberculosis.

Other doctors joined in the chorus of despair and tried to warn those who had not yet left the countryside:The young peasant, healthy and robust, dazzled by what he saw in the big city during his military service, deserts health, deserts home and family, and comes to enlarge the incalculable number of malcontents and have-nots who begin to see that life is not all roses and that health is not always in abundant supply.…Poverty, alcohol, and tuberculosis catch up with the stragglers and rip them apart without mercy.[9]

The great fortunes of the city, these doctors warned, were a mirage. “For every peasant who came to [Paris] covered with dirt and returned home as lord of the manor, how many—alas—have succumbed to the struggle[?]”[10] Many authorities accepted uncritically (and repeated) this notion of peasants seeking to strike it rich in the city. Few mentioned the devastating poverty of some rural regions, or indeed any other type of “push” motive, as possible factors in migration. Thus, even before the full sociomedical etiology of tuberculosis had been set forth, the soon-to-be-victim of the disease was depicted as at least partially at fault for choosing the conditions that would lead to his own downfall.If these words came to the attention of someone in the countryside, I would tell him: “You were born in the countryside, stay there.” Stay there, [and] resist this absurd, reprehensible impulse, which these days drives rural people to desert the native village to seek fortune in the big city.

One exception to this rule provides a variation on the “fortune-seeker” theme, while avoiding to some extent the victim-blaming tendency. Louis Renault, in a medical thesis on tuberculosis among Bretons, recognized that the attraction of the city might have something to do with economic conditions at home.

As much as delusions of grandeur, Renault blamed France’s mandatory military service for encouraging rural-urban migration. “Many young people,” he explained, “after three years in a city, no longer want to go back to work in the fields.” Moreover, their army comrades boasted of the advantages offered by urban life and ridiculed them for being mere peasants.They fall under the irresistible spell of the big City, where wages are higher, without realizing that the cost of living is also higher than back home. Knowing a few rare examples of fellow villagers who left with nothing and found success, they hope to have the same experience and they abandon their native soil to seek adventure.…[T]o escape the threat of poverty, they head off to a worse fate: the poverty of large cities.[11]

Greed, naïveté, suggestibility, and increased communication, particularly through railroad transportation and military service, were generally agreed to be responsible for the exodus of sixty thousand people per year (according to one estimate)[13] from the wholesome farms and villages to the diseased cities of France.Their envy is sparked: ambition and pride urge them on. When they return to their homes, the pastoral life seems hard and monotonous to them; at the first opportunity, they permanently desert their native land…[and] it will not be long before they know firsthand all the anguish of poverty, hunger, and disease.[12]

Once they got there, doctors and hygienists warned, the migrants’ country background made them more susceptible than city natives to the many “morbid influences” awaiting them. Accustomed as they were to fresh air, regular work, and a well-ventilated house, they were ill-prepared for the effects of city air, overwork, and “revolting slums.” Intending to return to their coin de terre with the money earned in the city, many migrants skimped on their diets and housing to increase their savings; this, too, made them “quite often the prey of tuberculosis, the ‘city disease’…for campagnards.”[14]

Yet in all of the rural exodus literature, the most commonly cited trap awaiting the new urban arrivals—and the most common gateway to tuberculosis—was debauchery. Establishing the inevitability of the descent into urban depravity and disease was crucial if rural-urban migration was to be integrated into the problematic of national moral-demographic decline.

Georges Bourgeois sought to explain the particular vulnerability of Breton migrants to tuberculosis by invoking “[their] poor hygiene, alcoholism, and [their] lack of moral resistance.” This explanation, he added, was “unfortunately applicable to [most] immigrants, no matter where they come from.”[15] This lack of moral resistance reinforced the sense of inevitability surrounding the slide into vice. Powerless to resist, the newcomer to the city was doomed; as all of the core narratives on this point make clear, opportunities and enticements to debauchery were everywhere.

Not only did the cabaret satisfy the worker’s need for sociability and relaxation but alcohol also provided a temporary relief from fatigue or poor nourishment.His life disrupted, the transplant wastes little time becoming intoxicated by the pleasures of Paris. Often led on by friends, he soon learns the way to the marchand de vins, especially since his dark and dreary lodgings hold little appeal for him.

Medical opinion seemed to be unanimous on this point: the progression from migration to tuberculosis passed through the cabaret.[17]Subjected to intensive labor or deprived of a sufficient diet, the worker hopes to find in alcoholic beverages the comfort…he needs. He drinks, soon becomes intemperate, and alcoholism leads to tuberculosis.[16]

Several doctors also warned of a corollary to the rule of tuberculosis among rural-urban migrants. As many observers pointed out, the true dimensions of the problem could not be accurately understood through urban mortality statistics, because many tuberculosis victims returned to their home village or province, either to die among family or in the hope of a cure in the country air. The result of this reverse migration was the introduction of tuberculosis, the “city disease,” into the countryside. The mere possibility of this contamination threatened the traditional and deep-seated image of rural France cherished by the urban bourgeoisie, and it prompted considerable anxiety in the medical community.

Louis Cruveilhier, the author of one study of this phenomenon, sought proof of its importance in his contention that tuberculosis mortality was highest in those departments out of which the most people emigrated. (Aside from numerous statistical anomalies in this argument,[18] Cruveilhier did not consider the possibility that both emigration and tuberculosis could result from poverty, and that the poorest departments tended to have the highest rates of emigration. However, it is less the factual accuracy of the argument than its place in the overall moral etiology of tuberculosis that is of importance in this context.) The urban-to-rural spread of tuberculosis typically occurred as follows, according to Cruveilhier. The peasant family lived in a humble dwelling that, while not exactly “very salubrious,” was relatively free of germs and harmless to its occupants’ health “as long as all members of the family stay[ed] home in the countryside.”

The previously harmless features of the rustic house became deadly once the tubercle bacillus was introduced from the city. As soon as any family member experienced any kind of physiological stress, “contagion is then unavoidable.” The likelihood of contagion was further enhanced by the fact that quite often in these households, the contaminating son/brother shared not just a bedroom but also a bed with other family members.[19] Such core narratives, and the problem of rural tuberculosis as a whole, served to universalize the syndrome of rural exodus and its effect on the national health. Under such conditions, it was impossible to approach the problem as a local one, or as one limited to certain social milieus.This is no longer the case as soon as a son who had gone to the regiment, or to the city as a factory worker or as a mason—or a daughter who had been a wet nurse—comes back home with the germ of tuberculosis. How easy contagion will turn out to be in such a milieu, poorly ventilated, never exposed to the sun, humid and cold, where tubercle bacilli maintain their full virulence.

Among the measures recommended to deal with the rural exodus and its role in tuberculosis, some aimed at neutralizing the “contagious” return of tuberculous migrants to the countryside. Cruveilhier, for example, urged that both urban and rural authorities be warned of “the dangers posed by the return of tuberculeux to their native land unless severe and effective measures are taken concurrently to isolate them as much as possible, in order to protect those who offer them hospitality.”[20] Other doctors proposed focusing such isolation policies on the city itself, so that susceptible migrants would not come into contact with tuberculosis in the first place.[21]

However, there was widespread accord on the most urgent measure of all: halting, even reversing, the depopulation of the countryside. Only policies striking at the root causes of the rural-urban migration, observers agreed, could have any lasting effect. Certain contributory factors such as military service could be mitigated, some felt, and they applauded the government’s decision in 1905 to reduce mandatory service from three years to two.[22] Yet several observers stressed that an overhaul of the French system of education was necessary if rural children were to be cured of the impulse to leave the countryside. The current system, wrote one doctor, “orients all children toward tuberculosis and toward bureaucracy.” “The education of farmers’ children…must not make them aspire to careers in banking or commerce. On the contrary, we must…keep them on the paternal land and prepare them to become…educated farmers.” With an education appropriate and relevant to their lifestyle and surroundings, peasant children would be able to “develop from an early age their penchant for agriculture.” There would be no reason for them to want to desert their rural roots.[23]

A few doctors even dreamed of reversing the fundamental trends of the Industrial Revolution and repopulating the countryside through rural factories and the revival of small-scale home industries. Two versions of this vision in particular depict a new industrial order in such a way as to constitute a sort of “counter-core narrative,” substituting optimism and renewal for the gloomy fatalism of the standard rural-exodus narratives. Charles Fauchon, in his 1903 pamphlet, Tuberculosis, A Social Question, mentioned the recent construction of a tobacco factory in a large city and mused,

This vision of a remoralized workforce, isolated from urban depravity and ensconced in a clean, sober domestic atmosphere, reconciles modern industry with the demands of public order and health;[24] it represents a kind of turn-of-the-century hygienists’ utopia and reveals by opposition many of the anxieties that found voice in the mainstream War on Tuberculosis.Suppose, on the contrary, that this factory…were built along a railway line, in the countryside[;] workers could live there cheaply, far from the unhealthy stimulations of cities, in hygienic houses…isolated from one another and surrounded by spacious gardens. There they would find excellent living conditions from every point of view, and tuberculosis could not find any victims in these milieus.

Lucien Graux, also writing in 1903, went so far as to claim that the new Industrial Revolution was already under way and already refashioning the moribund working-class family.

While Graux’s vision emphasized the return of the working-class woman to the home and the resulting reconstitution of the family, he shared with Fauchon a preoccupation with recapturing the rural essence of Frenchness that had been vitiated by modern urban life and that manifested itself in the modern, urban, industrial disease, tuberculosis.Already it seems that an economic revolution is in the works. The consequences of hydroelectric power are incalculable. Factories are springing up at the base of mountains, on sunny and windswept plateaus, far from unhealthy cities. Electric power…in every home will once again make domestic industry run, and the laborer will be able to work in his reconstituted household.[25]

Against the background of rural depopulation and the influx of uprooted peasants into urban factories and cabarets, hygienists and public officials set their sights on the triangular association of alcoholism, syphilis, and tuberculosis. In doing so, they intensified the tendency to ascribe moral value to the disease that claimed more lives than any other.

| • | • | • |

Alcoholism and Tuberculosis: Targeting the Cabaret

In a recent essay, Nourrisson emphasizes the contingent and shifting nature of the alcoholism–tuberculosis link between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth century. Harmless and even therapeutic until the last third of the nineteenth century, alcohol became enemy number one of the War on Tuberculosis by the turn of the century. The fledgling antituberculosis campaign borrowed from and built on the strength and membership of the established antialcoholism movement. After World War I, Nourrisson argues, huge wine production surpluses necessitated a medical “rehabilitation” of alcoholic beverages in general, and the link with tuberculosis declined (even though wine itself had never been specifically implicated). Not until after 1945 did alcoholism regain its privileged place in the generally accepted etiology of tuberculosis.[26] Nourrisson’s argument is provocative, and the broad outlines of his chronology are instructive. His essay should serve as a cautionary tale to anyone tempted to portray the evolution of medical or etiological science in a linear fashion. A more detailed investigation here of the development of the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection before World War I, breaking it down into its constituent elements and exploring its ramifications, will help establish the immediate social meaning of the connection, if not the ultimate reasons for its rise and fall.

Pre-germ theory medical texts in the early nineteenth century focused on the role of alcohol abuse in such sudden and exotic afflictions as apoplexy and even spontaneous combustion. Around the time of the Bourbon Restoration, medical dictionaries, while attributing revivifying powers to alcohol in small quantities, warned of these two risks as well as “imbecility,” pupil dilation, coma, convulsions, “insensibility,” paralysis, “and even death” in cases of abuse.[27] It should be noted that nineteenth-century medical references to “alcohol” meant primarily distilled spirits; fermented drinks such as wine, beer, and cider were often referred to as “hygienic beverages.”

A more extensive and detailed enumeration of the pathological effects of alcohol appeared in 1838 in the Annales d’hygiène publique, the nation’s first public health journal (founded in 1829). In the empirical and public policy-oriented style characteristic of that journal, Dr. Charles Roesch mentioned a multitude of illnesses under the heading “Drunkards’ Illnesses and the Types of Death to Which They Succumb.” From “melancholia” to cholera, including obesity, gangrene, “bilious fever,” and softening of the bones, the list covered much ground and notably included “pulmonary phthisis,” albeit without comment or elaboration. The bulk of the article considered in detail the medicolegal aspects of only a few of the conditions to which drunkards were said to be predisposed: apoplexy, spontaneous combustion, impotence, sterility, and epilepsy.[28]

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the Roesch study is its practical recommendations, aimed (like much of the material in the Annales d’hygiène publique) at eliciting action from governmental authorities. The recommendations were remarkable in that unlike the legions of later proposals, they did not focus on the cabaret or the débit de boisson. Roesch urged strict punishment of public drunkenness and related disorders, an end to the practice by household heads of giving drinks to their domestic servants (to revive their energies), and fabrication only of expensive, high-quality eau-de-vie, in order to put its purchase beyond the economic reach of poor families. Further, he fiercely denounced the colportage (ambulant sale) of spirits, precisely because the amount and pace of drinking was greater at home than at the cabaret or the marchand de vin. Roesch’s only regulatory measure involving débits per se proposed that none be licensed to sell only eaux-de-vie.[29] As will become clear below, this failure to indict the cabaret as fundamental to the sociomedical problem of drink and disease provides a striking contrast to the dominant opinion of the Belle Epoque. Just as striking is the absence in these early texts of tuberculosis as a major alcohol-related problem.

By the late Second Empire (at which time the concept of “alcoholism” had been more or less established), the connection of alcohol and tuberculosis seems to have become a more pressing medical issue, but opinion was far from unified. “You understand how important it would be for this question to be resolved,” wrote Dr. A. Fabre in the medical journal Gazette des hôpitaux in 1868. However, from Fabre’s point of view, the resolution was important not because of any action the public authorities might need to take with regard to alcoholism but because many doctors at the time actually used alcohol in their treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis.[30]

Fabre summarized the contemporary debate as follows:

He went on to explain that Magnus Huss had found, during autopsies of “drinkers,” dried tubercles in the lungs, suggesting that alcohol had arrested or cured incipient phthisis. Other researchers had claimed, on the contrary, that alcoholism brought about and accelerated the progress of the disease.We find ourselves here in the presence of two contradictory opinions: on the one hand, some doctors consider alcohol the least bad remedy for phthisis.…; on the other hand, Bell, of New York, Kraus, of Liège, and Launay, of Le Havre, maintain that alcohol produces phthisis and in particular the galloping form of this illness.[31]

Fabre proposed to resolve the question by examining the history of one of his patients with consumptive symptoms, an ivrogne who admitted drinking a liter of absinthe per day. The doctor cast doubt on the diagnosis of other cases usually cited to support the pathogenic link of alcoholism with consumption: perhaps these robust young people, alcoholic but with no family history of consumption, died in fact of various forms of pulmonary “inflammation” rather than of consumption itself. In the case at hand, the young man’s lungs at autopsy showed grayish, compact masses quite distinct from actual tubercles. Alcohol was indeed the source of the patient’s illness, in Fabre’s opinion, but the illness was not tuberculosis; rather, it was “a variety of caseous pneumonia probably developed under the influence of alcoholism.” The sequence went as follows: “First exaltation, then sedation, produced by the same agent, alcohol; exaltation, then dulling of the nutritive system, successively determined by the same illness, inflammation.”[32]

The successive, opposite effects of alcohol and alcohol-determined inflammation led Fabre to his paradoxical conclusion: “Knowing that alcohol can have precisely opposite effects, depending on the manner in which it is used, you will understand that the most effective treatment of accidents produced by alcohol consists of the use of alcohol itself.” If alcohol had caused any morbid effects in the body at all, matters would only be worsened by the complete withdrawal of alcohol from the system, for the body had become “habituated to a stimulant.” The doctor, then, needed to administer a stimulant, “and the best one, in this respect, is precisely alcohol.” With moderate doses, the doctor could regulate the patient’s gradual withdrawal from alcohol, although Fabre expressed pessimism over the prospects of successfully combating the social problem of alcoholism in this way. “Deadly poison or precious remedy, depending on whether it is abused or used wisely, you understand that alcohol occupies an important place in both pathology and therapeutics and that it has necessarily aroused strong contradictions until we realized the opposite effects it can determine.”[33] In this analysis, the doctor becomes a kind of artist, walking the tightrope between poison and remedy only by virtue of a subtle, professionally informed manipulation of substances. Fabre gave no dogmatic conclusion regarding tuberculosis, but the case studies he cited implied that despite some appearances, alcoholism caused only nontuberculous pulmonary inflammations.

If Fabre’s study did not resolve (or even address head-on) the question of alcoholism and tuberculosis, it did express the confusion and difference of opinion that continued to reign over the issue for several decades. In Louis Landouzy’s 1881 lecture series, “How and Why One Gets Tuberculosis,” which covered an exhaustive list of causes and manifestations of tuberculosis, there was only a single oblique mention of alcohol or alcoholism as a contributory cause of the disease: a reference to “excesses of all sorts.” Landouzy discussed alcoholism only as a unique terrain or soil on which tuberculous infection evolved in a particular fashion.[34]

Even after Koch’s discovery in 1882, uncertainty persisted. An 1887 medical encyclopedia, under the entry “Phthisis,” reviewed the debate just as Fabre had done, and took the middle ground.

Thus, alcoholism led to tuberculosis only when it produced lesions in the body’s gastrointestinal system. When alcohol affected primarily the nervous system or circulatory system, however, “it does not seem that it especially favors the development of tubercles.”[35] While this passage shows little certainty in the causal linkage of alcoholism with tuberculosis, the article does presage later work in its use of the word déchéance (fall or decay) to describe the effects of alcohol on the body. From the “déchéance” of the individual body to the “déchéance” of society as a whole was a step that later observers would not hesitate to take.We will take another point of view. Alcoholism ends in the decay [déchéance] of the organism; the fact is undeniable, but the causes of this déchéance are organic lesions. It is by altering tissues and apparatuses that alcoholism deteriorates the individual. Now, if alcohol provokes lesions which impede the diet, such as chronic gastritis,…tuberculosis may appear, as it appears in cases of undernourishment.

A similar encyclopedia article appeared the next year, in 1888, in which Dr. Victor Hanot took a somewhat stronger stand in linking alcoholism to tuberculosis. He took pains, however, to cite the arguments of both sides in the debate: on the one hand, alcohol has no relation, an inverse relation, or even curative properties with regard to tuberculosis; on the other, alcoholism predisposes to the disease. Researchers cited in the article as denying the pathogenic link had found, among other things, that drunkards and cabaret proprietors rarely suffered from tuberculosis and that the disease progressed more slowly in habitual drinkers than in nondrinkers. One of these researchers, Dr. Emile Leudet, found only 20 tuberculosis victims out of 121 alcoholics under his care. Leudet called alcohol an aliment respiratoire that slowed the loss of nutritive elements and conserved energy in the body, thereby exercising a favorable influence on health.[36]

Hanot ended by rejecting Leudet’s thesis, siding instead with another recent study, in which patients had “very manifestly” contracted their illness after “immoderate usage of alcoholic beverages.” Furthermore, tuberculosis developed quite rapidly in these patients, as it had in its “galloping” form observed by other authors in alcoholic patients. “We must therefore admit…that the abuse of alcoholic [beverages], supplemented by other excesses and by poverty, which ordinarily accompany drunkenness, predisposes to phthisis, or causes it to break out.”[37] A consensus among doctors appeared to be in the making, according to which alcoholism was a major predisposing factor to tuberculosis. Hanot’s qualification “supplemented by other excesses” is also curious, and typical of later writings on the issue. This implies a connection with sexual excess and venereal disease, and it would not take long before this link became explicit.

Medical opinion gradually crystallized during the 1890s around the belief that alcoholism was a major—if not the single most significant—social cause of tuberculosis. By 1898, when Dr. Constantin Thiron spoke to the fourth French Congress for the Study of Tuberculosis in Man and in Animals, the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection seems to have achieved the status of dogma that it would retain until World War I. Thiron’s paper, despite its somewhat unwieldy title, “Alcoholism, Considered as One of the Major Predisposing Causes, by Heredity or Acquired Individually, of Tuberculosis,” pithily expressed the social and political tensions underlying the connection. Thiron first asserted that “nobody at any time” had contested the proposition that alcoholism predisposes to tuberculosis (a manifestly false assertion, as the documents quoted above show) and went on to debunk the popular wisdom that alcohol had hygienic or therapeutic value.[38]

“Hereditary alcoholism” preoccupied Thiron: the children of alcoholics were “feeble, anemic,…scrofulous, irritable, disobedient and vicious,…sickly [tarés],…turbulent and restless.” Alcoholics were also prone to “excesses of all kinds”—not only immoral but propagating pathology into future generations. Among the consequences of their immorality was, inevitably, poverty: “poverty appears as a result of alcoholic vice and passion.”[39]

Having accounted for poverty, Thiron confronted the politics of drinking directly—and in a surprisingly polemical manner.

Socialism would seemingly disappear with the eradication of alcoholism. In this passage, bourgeois moralizing and the dark political associations of the cabaret fused to give the fight against alcoholism and its link with tuberculosis added strength. That Thiron’s argument was firmly grounded in a particular social and political position scarcely needs to be belabored. When Thiron finished by denouncing alcoholism and tuberculosis as “the principal causes of the depopulation of almost every country,”[41] the association of the two scourges can be said to have achieved its mature form.As for the question of pauperism, of socialism, and of the struggle for life, the worker could be happier if he eliminated the cabaret and alcohol from his ordinary habits, substituting for them sobriety, thrift, good nourishment and refreshing sleep; poverty is in part nothing but the result of the loss of time, money and health through alcoholism.[40]

Just two years later, in 1900 (the same year that the medical journal La Tribune médicale ran a year-long series of articles on “the crusade against tuberculosis and alcoholism,” pointing out the danger posed by the “alcoholic peril” to France’s “virility, and even [to] its existence”), the first French government commission on tuberculosis performed its work and presented its conclusions. The portion of the commission’s report devoted to the effects of alcoholism on tuberculosis expressed many of the same anxieties that underlay the medical studies noted above. The report used the term dégénérescence (degeneracy or degeneration) to evoke the joint ramifications of alcoholism and tuberculosis on French health and society.[42] The author of this section of the commission’s report, Dr. Edouard de Lavarenne, claimed that the departments with the highest per capita consumption of alcohol also had the highest percentage of military conscripts rejected for physical deficiencies—and therefore “the most candidates for tuberculosis.” “This is because alcoholism has a direct action on the race, and by debasing it…it dooms children more and more to the déchéance of which tuberculosis is one of the most habitual outcomes.”[43] It is significant that de Lavarenne used not only the army as the index (and guarantor) of national vitality but also tuberculosis as a measure of France’s déchéance. Clinical observation and experimental research had already shown, de Lavarenne argued elsewhere in the report, “the stigmata of physical and intellectual degeneration borne by the descendants of alcoholics.” These “hereditary defects” predisposed them to tuberculosis.[44] This was not the same heredity that caused tuberculosis in the essentialist era. In the Belle Epoque, heredity went hand in hand with contagion as a cause of disease, predisposing the soil to be fertile when the seed fell upon it. The confluence of these indicators—military strength, debased heredity, and tuberculosis—pointed to continued decline for the nation. Tuberculosis assembled various threads of anxiety into one coherent package of alarm.

Racial degeneration and depopulation also preoccupied Rénon. Alcoholic heredity, he warned, threatened to perpetuate substandard human specimens, subject to a multitude of biological and moral disorders, into future generations and to result in “the physical degeneration of the species.”[45] Rénon’s Maladies populaires did not, of course, pertain principally to the entire human “species” but rather to what was commonly called the “French race.” Such terminology underscores the extent to which, even at a time of truly international medical knowledge, when scientific literature and congresses crossed borders routinely, tuberculosis was perceived in France as a French problem above all.

As far as depopulation was concerned, however, alcoholism was not directly a culprit; in fact, alcoholics tended to have many children, Rénon contended. “Unfortunately, society gains nothing from it, because they are bad children. This is not a selection of the race, it is on the contrary a destruction of the race.” In effect, France had turned natural selection on its head, procreating particularly the unfittest. “It is nonetheless indisputable that alcoholism does not cause declining natality; what causes it is something else, the progress of neo-Malthusianism.”[46] This late-nineteenth-century movement, appropriating Thomas Malthus’s ideas about the relationship between population and means of subsistence, urged working-class families to restrict births voluntarily to improve their standard of living.[47] Pronatalists, in turn, accused the neo-Malthusians of complicity in France’s depopulation and decline. Alcoholism, Rénon and other mainstream doctors lamented, only compounded the problem by tainting what little human legacy was being left behind.

In most cases, empirical proof of the causal role of alcoholism in tuberculosis involved four types of evidence: anecdotes from clinical practice and the apparent distribution of tuberculosis along sexual, geographic, and occupational lines. The anecdotal evidence consisted of case histories from a doctor’s private or hospital practice, or simply impressions and observations from daily life. For example, in his medical thesis entitled How Parisian Working-Class Families Are Disappearing from Tuberculosis, Isidore-Paul-Alphonse Ladevèze profiled the patients in the hospital ward where he practiced.

There were no rules governing such evidence; each doctor gave free rein to his impressions and judgment (including who might be “suspected” of tuberculosis and that women were unwilling to admit their bad habits). Yet the “results” were generally accepted as statistically precise and were often cited by other authors. For example, Ladevèze referred to the clinical observations of Dr. Jules Lancereaux regarding the causes of tuberculosis:Among our 26 male patients, we found 19 that were manifestly alcoholic, or 72 percent. And we should note that some of them were robust workers that one would never have suspected of [having] tuberculosis, and in whom we found only alcoholism as a predisposing cause. Among women, only 3 of 18 were manifestly alcoholic, but we know that women do not easily admit their bad habits.[48]

In a recent communication to the Academy of Medicine, M. Lancereaux…attributes [cases of] tuberculosis—from the perspective of circumstances that could prepare the terrain and make it favorable to [the disease’s] development—as follows:

Tuberculosis and alcoholism 1,229 Insufficient ventilation, Sedentariness, Overcrowding 651 Poverty and deprivation [Misère et privations] 82 Poverty and pregnancy 91 Tuberculosis in the family (probably heredity) 93 Contagion 46 Total 2,192 We see in this table the preponderant influence of alcoholism.

Ladevèze accepted these results as statistically valid even while confessing, “[I] do not fully understand the forty-six cases under the rubric Contagion.”[49] His puzzlement actually highlights the curious nature of such “proofs.” They testify to the impulse in the medical community, especially where social etiology was concerned, to sanctify through quantification and systematization what were essentially anecdotal, subjective interpretations. Lancereaux’s table was characteristic of much of the work in this field in its attempt to ascribe to every case of tuberculosis a single, exclusive social “cause.”

In any case, such evidence was generally accepted as proof of the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection. Ladevèze also referred in his thesis to the sexual distribution of tuberculosis, in which the greater mortality from the disease among men than among women was used to indicate alcoholism as a causal factor. The gender differential had been exactly the reverse in the early nineteenth century, Ladevèze pointed out; to explain the shift, “one can only think of alcoholism, [which is] more developed among [men].”[50] Jacques Bertillon took this evidence a step further in a 1910 article, “Alcohol and Phthisis,” claiming that tuberculosis mortality rates were roughly equal for boys and girls until age fifteen. This corresponded, he noted, with the time when “the two sexes are equally sober.” “Afterward, the vulnerability of the bearded sex [du sexe barbu], which is also the drinking sex, manifests itself.” Moreover, Bertillon maintained, the gender differential in mortality did not manifest itself in the countryside—further proof that “alcohol makes the bed for tuberculosis” (l’alcool fait le lit de la tuberculose).[51]

The geographic line of reasoning typically held that the departments in France with the highest per capita consumption of alcohol suffered the highest mortality from tuberculosis. (Occasionally, it extended to the comparison of nations and ascribed France’s high rank in mortality among European nations to its high alcohol consumption.) Maps were commonly reproduced with departments shaded according to their alcohol consumption and tuberculosis mortality. They were not unequivocal—often showing little more than vague concentrations in both categories around Normandy, Brittany, and the Ile de France—but they were interpreted as quite clear evidence of the link. Bertillon, a doctor devoted to the use of statistics in public health, once again took the reasoning one step further. On the map showing alcohol consumption by department, he drew a line representing the northernmost limit of wine growing. With the exception of the East, the areas south of the line showed significantly lower rates of alcohol consumption. Similarly, the wine-growing regions seemed to have generally lower tuberculosis mortality. Distilled spirits, Bertillon concluded, were responsible for the difference.

Alone among those who denounced the role of alcoholism in causing tuberculosis, Bertillon opposed the idea of a regulatory crackdown designed to shut down débits de boissons. Because the real culprit was eau-de-vie, he advocated measures that would encourage débitants to sell, “instead of eau-de-vie or absinthe, good French wine. This will make the Midi happy, and at the same time it will diminish tuberculosis in the North.”[53]Thus, it seems to be eau-de-vie that regulates the distribution of phthisis throughout France; that is, of all causes that can prepare us to receive the terrible tubercle bacillus, there is none more effective than alcohol. The other causes (more numerous and very complex) pale before it like the stars before the sun. It is the master![52]

Always statistically minded, Bertillon went so far as to claim that if the departments of the North and East drank wine instead of eau-de-vie, their tuberculosis mortality would fall to the level of the wine-growing Midi (that is, to 25,500 deaths per year from 42,190), thus saving 16,500 lives per year. (“What sanatorium could even hope for such a result?”)[54] Such a conclusion typifies two tendencies in the dominant sociomedical methodology of the period: first, the extrapolation from (sometimes shaky) statistical evidence to unrestrained speculation sanctioned by numerical precision; second, the reference to a statistical “norm” or minimum attainable rate of tuberculosis (that of the Midi), which implicitly represented a social or cultural ideal—the robust, wine-drinking, truly French regions untainted by alcoholism and its attendant vices. This “southern norm” is analogous to the rural ideal depicted by the critics of the rural exodus; in both cases, the corresponding policy goal was somehow to get “back” to the truly French and healthy (imagined) past.

The last type of evidence commonly used to bolster the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection was occupational mortality. Bertillon, for example, compared the material situation of innkeepers, or cabaretiers, with that of other store owners, and found them roughly equivalent: “generally poorly housed, leading an enclosed life, and also subject to the emotions that often go along with commerce.” The only difference, Bertillon wrote, was that cabaretiers were forced to spend long hours every day in an “alcoholized atmosphere”: “even when they try to stay sober, they absorb alcohol through their lungs and through every pore, so to speak.” This atmosphere explained the much higher mortality from tuberculosis among innkeepers in England than among other shopkeepers.[55] While other hygienists generally limited themselves to commenting on the drinking habits of cabaretiers when citing these same statistics—failing to echo Bertillon’s assertion about absorption of alcohol through lungs and pores—the lesson was clear: workers in occupations prone to heavy drinking suffered a higher incidence of tuberculosis than did other workers.

Although innkeepers served as the prime exemplars of the occupational connection between alcoholism and tuberculosis, other workers occasionally provided variations on the same theme. The hygienist Robert Romme, for example, wrote in 1901 that postmen suffered disproportionately from tuberculosis, because they engaged “unconsciously” in “intense alcoholization.”

Whether it was conscious or unconscious, alcoholism did its damage. The combined effect of the various forms of evidence was to project utter medical certainty between the 1890s and 1914 on that which had earlier been debated and uncertain: alcoholism was a prominent—to many, the most prominent—cause of tuberculosis.The postman has a registered letter, a parcel to deliver, an invoice to collect, information to gather? Then it’s a chance to have a drink at the grocery store, the bar, the dairy, the butcher’s shop, and in this way postmen end up drinking ten or fifteen small or large glasses of wine, beer, absinthe, vermouth, etc., every day. It’s a rare postman who, after ten years’ service, doesn’t show some signs of alcoholic saturation. And once the soil is prepared for the specific seed to be sown, the Koch bacillus…does the rest.[56]

The central role of the cabaret in anxiety over the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection has already been suggested. Indeed, the seeming impossibility during the War on Tuberculosis of discussing this etiological issue (that is, the role of alcohol in tuberculosis) without focusing on the cabaret can be seen through a closer look at some representative texts. The slide from “problem” to “place” in nearly every medical discussion of this topic is remarkable and suggests levels of meaning beneath the ostensible aims of the texts.

Louis Landouzy, elegant orator and tireless leader of the struggle against tuberculosis in France, presided over the French delegation to the 1912 International Tuberculosis Congress in Rome. His report to the congress, “The Role of Social Factors in the Etiology of Tuberculosis,” made it clear that his failure in the 1881 lectures specifically to mention alcoholism among the causes of tuberculosis no longer represented his opinion on the matter. Leaving to other speakers the details of the alcoholism–tuberculosis connection, Landouzy wished to emphasize one particular aspect of the problem:

Its atmosphere “already deleterious in and of itself,” the cabaret was also a prime locus of contagion for a particularly susceptible clientele. It was shown in chapter 4 that one of the ways slum housing contributed to the spread of tuberculosis was via the cabaret (to which the working-class husband/father resorted to escape his unpleasant home). Here (and in other texts), as a lieu de collectivité, the cabaret provides a setting for contagion as well, thereby representing by itself all three strands of the dominant etiology—contagion, slum housing, and immorality.I shall only mention here the cabaret…as a public space where for hours, in an atmosphere already deleterious in and of itself, consumptives cough in people’s faces and spit on the ground, infecting those around them—who are easy to contaminate, since chronic alcoholism has already put them in a certain state of déchéance.[57]

It is not surprising that when Raoul Brunon, a doctor in Rouen who spent most of his career in the forefront of the antialcoholism movement in France, wrote a textbook on tuberculosis, alcoholism figured prominently in it. Brunon’s attention, too, seemed to slide toward the cabaret when he attempted to prove the connection between alcoholism and tuberculosis. He offered two case studies from his own practice to support his contention.

The second patient, “also…a colossus,” had been a débitant for fifteen years:Forty-eight-year-old man. He began coughing six months ago.…Since childhood, he has smoked, drunk coffee and eau-de-vie. Habitually [drinks] two coffees per day, and often absinthe as well.…For eight years, he has worked as a weaver in a large urban establishment. He is actively involved in politics and admits that, because of this, opportunities to go to the cabaret are more frequent than before. He is of strong Norman stock, a real colossus. He nonetheless has a rapidly developing form of tuberculosis.

That the cabaret appeared in the two case studies cited to prove that drinking caused tuberculosis is no coincidence. In particular, Brunon’s reference to the worker’s political activity (and his “admission” that he went to the cabaret) strongly suggests that the doctor was concerned as much with the débit per se as with the pathogenic effects of alcohol.He took over a failing business and, “to boost business, [he] raised quite a few glasses with his customers.”…Starting two years ago, he no longer drinks. It is too late. His life is in grave danger.[58]

Nor was Brunon’s clinical evidence unusual in evoking the political role of the cabaret.[59] The most forthright statement of the political anxiety over the cabaret—or perhaps the most extreme political agenda—came from Henri Triboulet at the 1905 International Tuberculosis Congress in Paris. At one point in his speech entitled “Alcohol–Tuberculosis,” referring to “our adversaries,” Triboulet paraphrased working-class demands for higher wages, shorter hours, and better housing. Triboulet then ridiculed these demands, claiming that workers would merely squander their extra hours and wages drinking at the cabaret. He proposed abstinence instead.

Pursuing the political argument even further, Triboulet clarified his point: squandered money was not the only connection between the cabaret and left-wing demands. Revolutionary politics—the politics of the cabaret—was in fact a politics of drunkenness.The doctor knows…that, for rest and proper nourishment, one needs money. And, to get this money, instead of proposing political and social upheavals, which are discussed all the more willingly the less probable they are known to be, the doctor contents himself with recommending a simple method, as hygienic as it is economical: abstention from alcohol.[60]

While it would be rash to attribute Triboulet’s political views to all of the doctors and hygienists who made the connection between alcoholism and tuberculosis (after all, even leftist agitators acknowledged some kind of connection), his outburst was undeniably significant as a look behind the “science” of the dominant etiology. Not only was the cabaret indicted as politically (as well as morally and physically) pathological but reform involved nothing less than a reformulation of national identity (and the triad of the French Revolution) along moral and hygienic lines, with “prosperity” its ultimate end.With the habituation of the nervous system to alcohol comes the miscomprehension of social laws: the politics of the cabaret, full of hatred, makes a great deal of noise and accomplishes nothing. With hygiene, let us substitute the politics of sobriety: with healthy organs, comprehension of all things is just and sound.…Thanks to hygiene, let us add to our national motto these three terms, which will never disgrace it: cleanliness, sobriety, prosperity [propreté, sobriété, prospérité].[61]

The medical literature’s focus on the cabaret and the intense anxiety it seems to have provoked were also apparent in the policy measures proposed to fight the alcoholism–tuberculosis relationship; most of them dealt strictly with the cabaret. As Brunon put it, “Prevention is in part contained in these few words: RESTRICTION OF THE NUMBER OF CABARETS.” The public health community was in overwhelming agreement that local authorities’ right to license new débits should be curtailed and many existing alcohol outlets closed down. Equally popular was the proposed elimination of the home distillery privilege (privilège des bouilleurs de cru), which allowed the extensive production of distilled spirits. The first governmental commission on tuberculosis in 1900 went further than some by suggesting “administrative regulations in the aim of hindering the frequenting of cafés and cabarets.” Others called for cutting taxes on “hygienic” fermented beverages (wine, beer, and cider); for antialcohol education programs in the schools and army; and for cooperative restaurants that would amply and cheaply nourish workers without serving alcohol.[62] In parliament, representatives of the antialcoholism movement repeatedly introduced bills restricting cabaret licenses or limiting the privilège des bouilleurs de cru. None of these legislative measures came to fruition before World War I.[63]

In the late twentieth century, after the triumph of the “disease model” of alcoholism, there may be less blame or moral stigma visited upon the alcoholic for his condition than in earlier times. The extent to which alcoholism served to fix blame for tuberculosis around the turn of the century in France is suggested by some revealing passages in the vast body of medical literature on the link between the two phenomena. Dr. Fauchon’s pamphlet La Tuberculose, question sociale addressed the hypothetical parents of a child lost to tuberculosis: “This seed of tuberculosis, it is neither you nor your domestics that gave it to your unfortunate child, it is your neighbors the alcoholics…and you are justified in saying: ‘Without those miserable alcohol drinkers who infected my child, he would still be with us.’ ”[64] Another doctor writing in La Tribune médicale in 1901 was scarcely more charitable, declaring that the association of alcoholism and tuberculosis “is no longer a matter…of microbes but of an adversary perhaps even more formidable, because it is man himself who, by his lack of will, his bad instincts, his passions, becomes his own enemy.” In a similar vein, a participant in a 1903 conference on alcoholism and tuberculosis spoke of “a cowardice of character, which leads to…a willful illness.”[65] In other pronouncements, the moral judgment was more subtle, but it is clear that blame was strongly attached to alcoholism—and through it, to tuberculosis—at the time of their association.

From the early nineteenth century to World War I, the medical attribution of tuberculosis to alcoholism progressed from debate and uncertainty to unanimity, and eventually allowed wide-ranging policy recommendations and moral pronouncements to be made. In contrast, the syphilis–tuberculosis connection followed no such course but continued to be expressed, despite a notable lack of scientific evidence indicating a direct causal link.

| • | • | • |

Syphilis and Tuberculosis: Targeting the Prostitute

The prostitute, immorality incarnate and an object of social anxiety in France comparable to the cabaret, became associated with tuberculosis through the study of venereal disease (especially syphilis) as a matter of public health warranting the attention and surveillance of the authorities. Because prostitution was universally considered to be the primary means of transmission of venereal disease, the incidence of syphilis in France became a kind of index of national morality. The history of the syphilis–tuberculosis link, when compared with that of alcoholism and tuberculosis, reveals at the same time less medical certainty and precision regarding pathogenesis and a similar underlying sociopolitical agenda.

Before germ theory and Koch, there was some precedent for considering syphilis a predisposing influence on the development of tuberculosis. At least one of the early-nineteenth-century medical encyclopedias listed syphilis (and antisyphilis therapy) among twenty-eight causes of pulmonary phthisis—including cancer, hysteria, and hypochondria—mentioned in medical literature.[66]

But by the time the syphilis–tuberculosis link became the object of more frequent study, beginning in the 1880s, discussion of syphilis was permeated with social and political issues such as prostitution and depopulation. Under the entry “Syphilis,” an 1883 medical dictionary prominently featured a discussion of the control of prostitution and complained about the disease’s role in national decline. “It is undeniable that syphilis, by the harmful influence it exercises on natality and on the vigor of the younger generations, is an important factor in the depopulation and bastardization [l’abâtardissement] of the race.”[67] Both low natality and vitiated heredity––two components of racial decline and social “counter-Darwinism”––were ascribed in part to syphilis.

A Dr. Granier gave a paper in 1885 before the Société de thérapeutique of Paris that connected syphilis with tuberculosis in an intriguing way. Granier’s paper can be situated within a strange sort of medical debate over the connection, a debate without overt disagreement but full of ambiguity and uncertainty. Granier began by referring to previous research on the question, which seemed to show that syphilis (by generally debilitating the body) favored the development of tuberculosis and accelerated its pace in subjects already predisposed to the latter disease. One authority had called syphilis “an undisputed source of the degeneration of the species and a no less indisputable source of consumption.” Granier’s summary of the state of medical opinion on this issue nevertheless equivocated on the exact nature of the pathogenic influence. “Perfect agreement, on the one hand, in admitting a determinant influence of syphilis on the development of tuberculosis in predisposed subjects; on the other hand, in denying a direct, special influence of syphilis on tuberculosis.”[68]

Granier went on to claim, seemingly in opposition to this conventional wisdom, that syphilitic infection itself, in a predisposed subject, could evolve into tuberculosis, “with no penetration whatsoever by an external germ.”[69] This contention of “morbid spontaneity,” of course, flew in the face of Koch’s discoveries of 1882, according to which only the entry of the tubercle bacillus into the body could cause tuberculosis. Although presented as little more than a hypothesis, Granier’s contention testifies to the increasingly close association between vice and tuberculosis that had begun to develop in the French medical community. Two medical encyclopedias published soon after Granier’s findings tended to downplay (albeit ambiguously) the direct influence of syphilis on tuberculosis, while highlighting the generally degenerative effects of syphilis on the species as a whole. It predisposed to tuberculosis only “as any debilitating cause” did, not in a particular or uniquely pernicious manner.[70]

“Morbid Associations: Syphilis and Tuberculosis; Soils and Seed” was the title of Landouzy’s presentation at an 1891 tuberculosis conference in Paris. The most curious of all texts linking syphilis with tuberculosis, the piece is all the more significant in that it represented the opinion of France’s leading “phthisiologist.” In a comment of only two and one-half pages, Landouzy presented differing, even apparently conflicting, views of the link. While his title suggested a predisposing relationship (direct or merely “debilitating”) of syphilis to tuberculosis, Landouzy did not address the issue of predisposition per se. Instead, he posited a “sclerogenetic” effect of syphilis, which resulted in a slowly evolving, “torpid” tuberculosis; he even suggested that such a “sclérolate de tuberculose” brought about the improvement of certain symptoms.[71]

Why, then, did Landouzy also lament, “[What a] bad, very bad morbid association [is] that of tuberculosis and syphilis proceeding in tandem”? (Mauvaise, très mauvaise association morbide que celle de la tuberculose et de la syphilis marchant de pair!) Its context suggests that this particular exclamation referred to cases in which an already tuberculous patient acquired syphilis. This sequence, according to Landouzy, gave the tuberculosis renewed severity and hastened its development.[72]

This brief article leaves many questions unanswered. In justifying the subject of his paper, Landouzy pointed to “the frequency of syphilis” and “the nonrarity of the association of syphilis and tuberculosis.” What he meant by the latter is less clear; he defined neither “association” nor “nonrarity.” Nor did Landouzy suggest whether the frequency of the association had a causal basis or was coincidental. The reference to “soil and seed” in the article’s title is equally unclear, since cases of tuberculosis aggravated by the presence of syphilis are mentioned only in passing. On the surface, at least, Landouzy seems to have concluded that prior syphilis somehow impeded the development of tuberculosis: it constituted an “acquired terrain” on which the tubercle bacillus produced “a very particular harvest.” He went on to urge researchers to study the evolution of tuberculosis on “terrains rendered pathologically improper” to the “easy development” of the bacillus.[73]

An 1894 report in a medical journal set forth a contrasting view of syphilitic “soil.” Professor Carl Potain, teaching at the Hôpital de la Charité in Paris, examined a twenty-nine-year-old syphilitic who had begun to show symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis. The combination, in Potain’s experience, was common, “and in the large majority of cases, it is syphilis that opens the scene, tuberculosis only developing later.” The issue was quite clear, leaving no room for equivocation or ambiguity: “Syphilis calls forth tuberculosis [and] furnishes it with a good soil on which to grow.”[74]

René Jacquinet, one of Landouzy’s students at the Paris Faculté de médecine, published his thesis on syphilis and tuberculosis (as well as a related study in La Presse médicale) in 1895. Far from describing the torpid tuberculose sclérosante of Landouzy, however, Jacquinet presented observations of a quite different nature. Most of Jacquinet’s case studies, in fact, all of whose subjects were syphilitic prior to tuberculous infection, exhibited a severe, rapid tuberculosis––fatal in a very short period of time.[75]

Jacquinet admitted that it was difficult to establish statistics on the coexistence of syphilis and tuberculosis and on the temporal or causal sequence of the diseases. Nevertheless, nearly all of the authors he quoted on the subject portrayed the predisposing or “provocative” effect of syphilis on tuberculosis as frequent. To conclude his section concerning the etiological role of syphilis, Jacquinet quoted the venereal disease authority Alfred Fournier, who also characterized the progress of syphilis-caused tuberculosis as rapid and quickly fatal. “According to my own experience,” Fournier said, “as well as what has been said by…the most authorized observers, I would not hesitate to inscribe syphilis in the etiological chapter of pulmonary tuberculosis.”[76]

Jacquinet did cite his mentor Landouzy, indeed quoted him at length, on the sclerogenetic effect of syphilis. This apparent internal contradiction, not characterized as such by Jacquinet, can perhaps be explained by the timing of the syphilitic infection involved. Jacquinet presented Landouzy’s findings as bearing only on infections that were already many years old when the tuberculosis began; in contrast, Jacquinet devoted most of his own attention to still-active, virulent syphilis.[77] This distinction (made more clearly in Jacquinet’s thesis than in La Presse médicale) offers a possible explanation for syphilis producing both torpid and rapid tuberculosis, but it does not explain the conclusion of Jacquinet’s thesis, attributed to Landouzy: “Among infectious associations, there is none worse, none more formidable, than the combination of a syphilis and a tuberculosis.”[78] It is difficult to understand why a retarding effect would be likened to an intensifying effect and called the worst infectious “association” possible.

Despite the ambiguity of the syphilis–tuberculosis link, some sort of association certainly existed, if only as a result of the frequency of references in the literature; and if syphilis were associated with tuberculosis, it was inevitable that prostitution would enter into the association. It did so in various ways, and not always with direct reference to venereal disease. It should be borne in mind, however, that all discussion of syphilis (including its relationship to other threats and “scourges”) contained, implicitly or explicitly, a discussion of prostitution.[79]

An interesting example of the way in which prostitution insinuated itself into discussions of tuberculosis arose in the proceedings of the French government’s first tuberculosis commission in 1900. Professor Charles Bouchard, calling the commission’s attention to “the frequency of tuberculous contamination by prostitutes,” proposed that tuberculosis be added to the list of venereal diseases for which prostitutes were periodically examined by the authorities. Bouchard’s resolution justified this measure as follows:

This passage apparently indicates that kissing—which “often happens” during sexual intercourse—can transmit tubercle bacilli. The resolution continued,The extended and prolonged contact of the oral mucous membrane of a tuberculous person with the same mucous membrane of a healthy person, as often happens during the genital act, is a very favorable condition for the transmission of tuberculosis.[80]

His striking conclusion followed logically: “Transmitted under the conditions indicated above, tuberculosis acquires the character of a veritable venereal disease.”[82]This circumstance, even more than alcoholism, is the cause of the extreme frequency of tuberculosis in prostitutes;

. . . [T]his same cause makes the prostitute a frequent source of tuberculosis.[81]

Several features of this proposition deserve further comment. First, the association of the prostitute with alcoholism was presupposed and needed no proof. Second, the prostitute with tuberculosis was seen not as a victim or potential patient but as a potential “source” of contagion. Finally, while Bouchard’s actual etiological contention was simply that kissing could spread germs, the displacement of the issue to that of prostitution was seemingly instantaneous and unselfconscious. Blame was placed on a safe target (and not, for example, on just anyone who engaged in kissing), and further surveillance of prostitutes was rationalized. The second, “permanent” government commission on tuberculosis does not appear to have investigated the question in depth, but it also received evidence according to which prostitutes were among “the most serious agents of the propagation of tuberculosis.”[83]

Both prostitution and syphilis reappeared in connection with tuberculosis in Rénon’s 1905 textbook, Les Maladies populaires. While Rénon classified syphilis as one of several illnesses (along with typhoid fever, influenza, measles, and smallpox) that predisposed to tuberculosis, he did not draw as direct a causal tie in this direction as he did from alcoholism to tuberculosis. The association was no less strong, however, for lacking a physiological pedigree, as will be shown below in a discussion of the ultimate triangular link.

Three other similarities between the syphilis problem and the alcoholism problem are illustrated in Rénon’s book: racial degeneration, the threat to the social fabric, and the association with the cabaret. The first has been touched on at length above, and Rénon simply reiterated similar concerns about degeneration in his book.[84] As for the social fabric, its most fundamental underpinning was the family, and syphilis had a ruinous impact on the family.

In Rénon’s view, symptoms and scandal went hand in hand; the clinical entity could not be conceived of apart from its social ramifications. The physical and moral dimensions of syphilis were inseparably intertwined, and each had dire consequences.It means the end of the marriage, discussions, separation, divorce. It also means the contamination of the wet nurse and its results: unlimited blackmail or a scandalous trial for damages. It means, finally, the material ruin of the family, and after the illness, the incapacity [and] the death of the family head, [and] destitution.[85]

The cabaret, subtextually omnipresent in Rénon’s book, was explicitly implicated on several occasions in the genesis of the three associated scourges. As far as syphilis was concerned, sailors from the French navy and merchant marine were among the groups subject to the cabaret’s deleterious influence. The frequency of syphilis among the sailors was understandable, wrote Rénon,

Also reigning at the cabaret, of course, though not mentioned by name, were the prostitute and the end result of all these pathologies, tuberculosis.if one thinks of the evil that can be done by all the shady cabarets in port cities [tous les cabarets interlopes des ports], frequented by sailors who go there after long periods of continence. Alcoholism and venereal diseases reign there in tandem.[86]

| • | • | • |

Completing the Triangle: Immoral Places, Immoral Behavior

The confluence of alcoholism, syphilis, and tuberculosis––the complete triangular association––operated in a subtler way than did the two-part connections discussed above. Above all, the triangular link demonstrated the force and frequency of the specter of the cabaret (and, to a lesser extent, the prostitute) in turn-of-the-century fears of French decline and degeneration.

Before considering the triangular link in its full three-part form, it is worth mentioning that on occasion during this same period, medical literature explicitly linked alcoholism and venereal disease without the nexus of tuberculosis. For example, the 1901 International Congress on Alcoholism heard a paper in which it was argued that while alcohol had an undeniable influence on venereal disease by encouraging sexual excesses, it was “tipsiness” rather than drunkenness or chronic alcoholism that correlated most closely to the contraction of venereal infection.[87]

Another of the rare medical expositions of the alcoholism–syphilis connection was more provocative in its social implications. This study, by Dr. Barthélemy of the clinical staff of the Paris medical faculty, appeared in the Annales d’hygiène publique in 1883 (before the other links described above had coalesced). As a follow-up to one of his earlier studies, which had posited an aggravating effect of alcoholism on syphilitic chancres, Barthélemy looked into the surprising frequency in the initial study of serious cutaneous infection among women. He found that all of the women so affected were “femmes de brasserie,” pub waitresses known to offer additional services to their customers, and that all of them were forced by their employers to drink excessively.[88]

On further study of the situation of femmes de brasserie in general, Barthélemy found that most were syphilitic; indeed, they were the principal source of venereal disease among “the young men of the Ecoles.” In the interest of public health and better surveillance of “clandestine prostitution,” the doctor recommended that these “establishments served by women” be suppressed in their current form as “insalubrious establishments of the first degree.” Barthélemy justified such a regulatory measure (at first sight incongruous in an article entitled “Influence of Alcoholism on Syphilis”) by “the frightening proportion in which [syphilis] contributes to the depopulation of the species…and at the very least to the degeneration of the race.”[89] This is one of the first instances of the cabaret and the prostitute being medically implicated in depopulation and degeneration. It would not be the last.