5. Primeval Chaos

A revolution does not deserve its name if it does not take the greatest care possible of the children—the future race for whose benefit the revolution has been made.

At the time the tragic problem of these children seemed unsolvable.

While the famine scuttled any thought that Narkompros’s receivers and detdoma could operate as planned, it did not eliminate these institutions. Quite the contrary. In 1921–1922 they multiplied as rapidly as the most ardent partisan of “social education” could have dreamed three years earlier. But the reason for the increase—the soaring number of waifs—did not coincide at all with the expectations of euphoric revolutionaries in 1917–1918. As the crisis deepened, officials in Narkompros and other agencies asked ever more urgently how the network of children’s institutions could absorb the deluge of abandoned girls and boys. They wondered, too, about the effort to decriminalize juvenile delinquency when young thieves appeared at every turn. Such concerns prompted, or stemmed from, another question: What was actually happening inside facilities for homeless youths during these difficult years? The answer would help shape renewed efforts to salvage a socialist generation from the street, once the famine had run its course.

Nowhere did children’s institutions proliferate more rapidly than in the nation’s capital. As early as June 1921, Narkompros acknowledged the need to enlarge Moscow’s network of receivers in order to absorb urchins, who seemed more numerous each day. Plans called for several additional receivers (and observation-distribution points, sometimes combined with receivers), whose intended capacities ranged as high as one thousand.[1] The space would not go unused. From November 15 to December 15, with refugees pouring into Moscow from the famine zone, the Pokrovskii receiver alone admitted 3,925 youths. Slightly under 1,000 had been evacuated by the state, while the remaining 3,000 had fled starvation on their own. During the course of 1922, the city’s receivers processed approximately 1,000 juveniles per month, only 4 percent of whom were native Muscovites.[2]

In the country as a whole, the number of receivers increased steadily during the famine period, reaching 237 (along with 160 observation-distribution points) in the Russian Republic by the summer of 1922.[3] Unfortunately, this represented only a fraction of the quantity required to accommodate the homeless millions, and remained more than 300 below Narkompros’s original goal of one receiver per district. Local officials, lacking resources to open hundreds of additional facilities, packed existing receivers five and even ten times over intended capacity.[4] A doctor in Simferopol’ characterized the city’s receivers as “dumps” into which boys and girls were crammed without attention or even count, and whose exhausted staffs simply “threw up their hands before the ceaseless influx.” In one large room, roughly two hundred children covered plank beds, the floor, window sills, and a piano. Circumstances numbed them to the point where they matter-of-factly utilized as tables the bodies of others who had already died. “Corpses served as pillows for those who, tomorrow, might expect the same fate.” Every evening, personnel counted the inhabitants and then placed an order for the next day’s food. By morning, the census was usually obsolete: residents had died, run away, or, conversely, arrived during the night. Furthermore, a constantly changing number materialized from the bazaars each day at mealtime—and disappeared again after eating.[5] American relief officials inspecting receivers in Samara described the conditions as “heartbreaking”: “The first place we visited was a ‘receiving home.’ Before the war this building was erected as an orphanage for fifty children; today [September 1921] it holds more than six hundred. They lie in the yard, on the floor, on wooden benches, one on top of another, sick and well together, covered with dirty, lousy rags. For this large number of children there are only ten small soup dishes and fifty wooden spoons.”[6]

During the famine, youths often arrived at receivers and observation-distribution points in deplorable condition: grotesquely swollen stomachs bulged from shriveled physiques covered with excrement, dirt, and lice. Now at death’s portal, many expired shortly after entering crowded rooms and sinking into vacant spaces on the floor. Figures do not exist to reveal the toll in institutions at this time, but reports from individual facilities underscore the obvious. Children succumbed in droves. At a receiver in Orenburg, 118 (from a total of 935) perished in just two days. Institutions in Groznyi and Vladikavkaz recorded mortality rates as high as 30 percent in the period November 1921–early January 1922, while in Simferopol’ thirty inhabitants died every day in one receiver during the emergency’s peak. Given the shortage of buildings and the vast quantity of victims, those with infectious diseases could not be isolated from the rest. Bodies weakened by the famine offered little resistance to myriad ailments, which thus spread rapidly in crowded rooms. Staff members themselves sometimes contracted the maladies, a risk that prompted a few to sever all contact with their charges and even flee the institutions.[7]

As the famine waned in 1922–1923, receivers’ primary clientele changed gradually from emaciated, desperate refugees to juveniles adept at fending for themselves. These vagrants, cast loose by the famine or earlier misfortune, drifted in and out of institutions or tried to avoid them. With time, they mastered the skills necessary to survive indefinitely on the street and absorbed its manners and recreations. Thus endowed, they presented different problems to receivers than did famine victims listing on grave’s edge. Of course, some abandoned adolescents in 1923 could not yet be classified as veterans of markets and train stations, while numerous children at large during the famine had already been hardened by years in such haunts. But after 1922, as fewer new urchins appeared, inveterate waifs accounted for an increasing portion of the remaining pool of homeless children.

These pupils of the underworld complicated greatly the work of receivers, sometimes disrupting them to such an extent that institutions assumed the air of criminals’ dens. Even when a staff managed to maintain control—by driving out, transferring, or domesticating troublemakers—the process rarely proved smooth or rapid.[8] In overcrowded buildings, practiced young thieves could not be separated from weak or green occupants (often dubbed ogol’tsy, meaning stripped or naked ones), thereby enabling the former to prey on the latter. In receivers where seasoned youths held sway, they greeted newly arrived ogol’tsy with beatings, just as they had on the street, and commonly seized clothing, blankets, and meals from those unable to resist. At Moscow’s large Pokrovskii receiver, a staff member noticed the leader of a gang brazenly consuming several servings of food while a newcomer in poor health sat quietly in the corner with only a meager portion of thin soup. She demanded that the leader share his repast with the silent diner—and received an indignant refusal. Her order struck the gang member as an affront to the institution’s protocol; the idea that he be placed on the same footing as the sickly figure in the corner seemed absurd. Thus he continued his meal, rebuffing the woman with icy rudeness. Flinty aristocrats of this sort reigned throughout the Pokrovskii receiver early in the decade, reserving the best places to sleep, buying and selling others’ belongings, “hiring” lads to perform chores, and collecting “tribute” from weaker neighbors. One boy extracted protection payments from a group of Tatar children who feared abuse at the hands of their Russian counterparts. In some receivers, toughs exercised more control over other residents than did the institutions’ staffs.[9]

Juveniles despoiled not only each other but the receivers themselves. Food, sheets, blankets, clothing, even furniture disappeared with daily regularity at some institutions, often to be resold in nearby streets and markets. Thieves also slipped out to steal from the surrounding population, in one case filling an entire neighborhood with fear of the adjoining receiver.[10] In such conditions, the relations between adult personnel and their charges bore little resemblance to those desired by Narkompros. It took a patient, optimistic staff member not to regard experienced waifs as irretrievable hooligans, and many adolescents in turn expressed sullen mistrust toward their “upbringers.” Most often, the suspicious, restless, and unhappy (including those abused by other youths) ran away before they could be sent on to an observation-distribution point or detdom. Some remained less than a day, long enough only to secure a set of new clothes or a meal.[11]

Narkompros had anticipated that receivers would hold children for no more than a few days of preliminary observation and processing before distributing them to Juvenile Affairs Commissions, detdoma, or other destinations. But the homeless tide that flooded receivers also engulfed detdoma, colonies, and clinics, leaving few openings to which receivers could discharge their multitudes. As a result, receivers found themselves obliged to keep youths for months rather than days, which greatly exacerbated overcrowding and related problems.[12] It also meant—for something had to be done with wards remaining indefinitely—that receivers came to assume responsibilities originally intended for detdoma, including the provision of classroom education and labor training.[13] In most cases the transformation took place by force of necessity and without prearrangement, as staffs contended with a situation thrust on them by reality rather than decree.[14] The outcome varied greatly. Despite setbacks and disappointments, some receivers managed to break (or at least loosen) the street’s hold on their residents, even arrivals wedded to a vagabond life.[15] More often, however, sources early in the decade portrayed facilities plagued by the aforementioned deficiencies—hardly grounds for astonishment, given the magnitude of the problem facing an inexperienced government armed with modest resources.

| • | • | • |

While the process often required several months, receivers did eventually discharge children who had not already left on their own. The intended destinations included relatives’ homes, hospitals, clinics, and observation-distribution points, but the route traveled far more frequently, especially by the genuinely homeless, led to detdoma.[16] In broad terms, the designation detdom referred to a facility housing children during the extended period of education and labor training considered essential for a productive life. Institutions of this sort received a wide assortment of other names in various localities—including colony or labor colony, labor institute, school-commune, and home-commune, to list a few—with a document sometimes employing first one label and then another (and perhaps a third) in reference to a single detdom. Some authors observed clear distinctions when using these terms, but many others interchanged them freely. As a general rule, establishments sporting “colony” in their titles were located in the countryside and occupied youths primarily with agricultural pursuits. They, along with facilities whose titles included “labor,” were typically intended for the rehabilitation of “difficult” or “morally defective” juveniles. But institutions so named did not all share these characteristics, and they did not monopolize them.[17]

As local authorities scrambled to acquire buildings for expanding the network of detdoma, they faced the same difficulties that beset them in securing premises for receivers. With resources insufficient to construct hundreds of new facilities, they pressed the widest variety of existing structures into service, including municipal buildings and establishments used prior to the Revolution as shelters for orphans and delinquents.[18] Officials also sought the rights to houses, dachas, and estates confiscated from the prerevolutionary elite. In this event, if someone of Dzerzhinskii’s stature intervened, splendid mansions opened their doors to the homeless. More often, though, the modest clout mustered by provincial offices of Narkompros (and the Commissariat of Social Security before it) yielded estates and residences in extreme disrepair. A detdom in Zvenigorod district, for example, appeared at first glance to be a superb facility. Standing in a large park on a bank high above the Moscow River, the manor, formerly property of the wealthy Morozov family, boasted thirty-six rooms, a marble stairway, central heating, running water, and electricity. But closer examination revealed that the local population had carried off everything movable and smashed most of what remained, including the heating, electrical, and water systems. Similarly, when a “labor school-commune” was established on a former noble’s estate near Simbirsk, children and staff had to enter the building with shovels to clear it of filth deposited during the previous few years by hundreds of deserters.[19] Churches and especially monasteries also took on new roles as detdoma. Some had lain abandoned for months or years after 1917; others sheltered monks or nuns throughout the revolutionary period, until they were evicted to make room for waifs. A few continued ecclesiastical activities, at least for a time, even after the youths arrived.[20]

The legions of juveniles who disrupted receivers moved on to burden detdoma with many of the same predicaments—most obviously overcrowding. Even before the famine, the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate discovered that detdoma in numerous provinces bulged with as many as several times their intended volume of inhabitants. So, too, did shelters in sectors outside Bolshevik control during the Civil War, as American Red Cross representatives noted in Ukraine. There a local official told them of “54 orphanages in the country controlled by Petliura with 30,000 children inmates [an average of 556 youths per orphanage!].”[21] By autumn of 1921, the squalor described in these accounts paled against the horror reported routinely from the Volga basin, southern Ukraine, and nearby regions inundated with famine refugees. Skeletal forms packed every square foot of detdoma, while hundreds more waited outside many facilities, begging for admission and perishing in untold numbers.[22] Altogether, the detdoma of Ufa province took in 60 to 100 youths every day as early as June 1921. By December the total reached 150 per day—and exploded to 500 two months later. As a result, the province’s detdoma staggered under a load estimated at 500 percent of their planned capacity at the beginning of 1922, with an additional 50,000 candidates left in the street.[23] One of Samara’s detdoma struck a visiting journalist as nothing so much as “a ‘pound’ for homeless dogs”:

All across the famine zone, as homeless children proliferated at a much faster rate than did institutions to house them, the populations of existing detdoma mounted (table 1). Many local authorities could have written the lines sent to the Children’s Commission in Moscow by a Narkompros official in Baku: “I declare without exaggeration that we have, not children’s homes, but children’s cemeteries and cesspools in the literal sense of the words.”[25] Later, when the famine subsided, it left behind institutions in such dismal condition that one author wondered pointedly whether boys and girls already in detdoma might require aid just as urgently as those still on their own.[26]They picked up the wretched children, lost or abandoned by their parents, by hundreds off the streets, and parked them in these “homes.” At the place I visited an attempt had been made to segregate those who were obviously sick or dying from their “healthier” fellows. The latter sat listlessly, 300 or 400 of them in a dusty court-yard, too weak and lost and sad to move or care. Most of them were past hunger; one child of seven with fingers no thicker than matches refused the chocolate and biscuits I offered him and just turned his head away without a sound. The inside of the house was dreadful, children in all stages of a dozen different diseases huddled together anyhow in the most noxious atmosphere I have ever known. A matron and three girls were “in charge” of this pest-house. There was nothing they could do, they said wearily; they had no food or money or soap or medicine. There were 400 children or thereabouts, they didn’t know exactly, in the home already, and a hundred or more brought in daily and about the same number died; there was nothing they could do.[24]

Inevitably, severe food shortages accompanied overcrowding. Malnutrition and outright starvation occurred most routinely during the famine, of course, but the lack of sufficient provisions crippled institutions throughout these early years—reflecting the privation faced by much of society. Time and again, as the number of waifs increased in a province and local officials opened additional detdoma, they received ever more irregular and inadequate deliveries of food. Appeals to superiors rarely availed, because the same misfortunes that spawned a surge of homeless juveniles often reduced a region’s food supplies.[27] As rations dwindled in detdoma, some children not yet incapacitated by starvation launched forays to steal from nearby markets or peasants. Even before the famine, girls at an institution in Petrograd engaged in prostitution to acquire food, and desperate authorities in Beloozero (Cherepovetsk province) sought permission to release detdom residents to forage for themselves. By the end of 1921, ravenous staff members joined youths at some institutions on expeditions to beg for sustenance.[28]March 28, 1922August 1, 1921July 1, 1921February 1, 1922

1. Increase in the Number of Detdoma and Their Inhabitants, 1921 January 1, 1921 December 31, 1921 Detdoma Children Detdoma Children source: TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 25. Volga Germans 12 |428 33 3,300 Simbirsk province 65 3,530 117 11,719 Stavropol’ province 40 2,279 125 12,490 Tambov province 113 7,834 134 13,372 Tatar Republic 110 5,670 232 17,971 Ufa province 103 4,976 239 23,985 Cheliabinsk province 90 6,103 222 22,200 Tsaritsyn province 51 2,374 159[a] 14,721[a] Samara province 294 18,000 407[b] 44,660[b] Astrakhan’ province 67[c] 2,964[c] 92 5,509 Viatka province 89[c] 3,347[c] 109 10,934 Perm’ province 165[c] 7,703[c] 203 12,214 Saratov province 145[c] — 180 18,000 Chuvash region 12[c] 489[c] 40[d] 4,500[d]

In these grim years, detdoma lacked not only food but adequate supplies of nearly everything else as well—furniture, clothing, utensils, tools, books, and agricultural implements. Reports streamed in to provincial capitals and to Moscow, describing children who lapped soup out of cupped hands (in the absence of bowls), occupied themselves with disturbing activities learned on the street (as insufficient books, equipment, and staff thwarted more wholesome projects), and, in general, languished in buildings devoid of the most basic conveniences.[29] Administrators of many detdoma, left to shift for themselves, received no supplies for weeks and even months. Anton Makarenko explained in 1922 that when he needed kerosene to light the buildings of his colony, the local Narkompros office instructed him to catch dogs and melt down their fat.[30]

Most detdoma, overcrowded as they were, could not maintain ample sleeping facilities. Three or four youths often shared each bed, and many simply huddled on the bare floor, covering themselves with anything at hand, including old curtains and rugs. An institution in Viatka, with no blankets at all, issued sacks to sleep in.[31] Similarly meager supplies of shoes and clothing did not stretch to outfit the ragged and half-naked millions. Reports told of numerous institutions providing footwear for as few as a quarter of their inhabitants, and even these shoes were not always serviceable. The entire populations of some detdoma faced winter barefoot or with only a few pairs of boots and shoes to share. This, combined with a dearth of warm clothing, commonly required detdoma to keep their charges indoors all winter, which in turn prevented the children from attending school if the detdom did not operate one of its own.[32] Even inside, the bite of winter left its mark. Crumbling walls, broken windows, and lack of heating fuel permitted icy winds to roam buildings as master, lowering interior temperatures to the neighborhood of zero degrees Celsius. From the Kuban’ came word of frostbite acquired indoors and floors coated with ice after a washing; in Tashkent, desks were smashed and burned as fuel; and in Iaroslavl’, children slept embracing each other tightly for warmth. A report to Dzerzhinskii described certain detdoma in Simbirsk, Saratov, Penza, Vladimir, and other provinces as completely unheated—so vulnerable to the cold, in fact, that snow drifts developed now and then inside rooms.[33]

Shortages of food, clothing, heat, and space contributed to levels of hygiene and illness in detdoma that shocked investigators. Early in 1923, a health commission portrayed a detdom in Samarkand as “an utter cemetery of decaying, live children,” and this spectacle was not restricted to Central Asia. In Samara province, health officials were brought before a revolutionary tribunal “because of the horrible, unsanitary condition of children in institutions.” Many detdoma had no lavatories at all, so that boys and girls relieved themselves in yards, hallways, and even their own beds. Existing latrines often overflowed with filth, through which barefoot youths walked routinely. In some overburdened facilities, juveniles caked with grime and parasites received baths only at intervals of several weeks.[34] Their crowded buildings also lacked space to isolate the ailing from the relatively healthy, which further hastened the march of infections. Rare indeed was the institution at this time whose inhabitants did not suffer from a wide variety of maladies, and in some facilities nearly everyone (even the staff) was stricken. In Kazan’, for instance, fully 85 percent of the residents in one detdom had malaria early in 1921. Throughout the country, common ailments included skin and eye infections, fungi, parasites (often lice), typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis, malaria, and scurvy. Nor were venereal diseases strangers to institutions, especially those for delinquents. Among 290 at a home for the “morally defective” in Ekaterinodar toward the end of 1920, 60 had contracted syphilis.[35]

In light of the preceding, there can be no doubt that many thousands (perhaps hundreds of thousands) died in detdoma during the period 1918–1923. While precise information for the country as a whole has not been published, and may well have escaped compilation in these turbulent years, a few detdoma reported during the famine that half or even three-fourths of their occupants had perished. “At one children’s home that I visited,” wrote a traveler in Buzuluk, “of 141 boys and girls received in the course of the previous week, 76 had died. This was by no means an exception.” More often, however, dispatches told only of “high” or “very high” mortality, leaving details to the imagination.[36]

Along with illness and death, thefts appeared among the consequences of shortages rife in detdoma, for hunger stimulated much the same desperation within institutions as it did on the street. Underworld veterans, of course, might plunder any detdom, well supplied or not, to support habits acquired while at large or merely for the adventure. But insufficient food in a facility prompted others to join them in pilfering anything at hand—sheets, blankets, shoes, clothing, tools, utensils—and spirit the items away to the nearest market for sale. Such transactions deprived detdoma of essential supplies, to be replaced with great difficulty if at all. Some residents, rather than (or along with) stealing from detdoma, took to raiding other targets in their neighborhoods, such as peasants’ storerooms and passing travelers.[37] As Makarenko put it, recalling the early years of his colony:

In full accordance with the theories of historical materialism, it was the economic base of peasant life which interested the boys first and foremost, and to which, in the period under consideration, they came the closest. Without entering very deeply into a discussion of the various superstructures, my charges made straight for larder and cellar, disposing, to the best of their ability, of the riches contained therein.[38]

Finally, youths not disabled by hunger or disease frequently responded to woeful conditions in detdoma by fleeing. Though they abandoned institutions for other reasons as well—a city’s lights and excitement, perhaps, or to escape beatings and gambling debts—it appears reasonable to suppose that lamentable facilities prompted most flights in these initial years. In any case, children slipped away and returned to the street in countless thousands, often absconding with clothing and other property to sell for food and entertainment.[39]

Facing so many obstacles, it must have been a rare staff member who did not succumb at least occasionally to bottomless despair.[40] Aside from the formidable difficulties just described, gangs, gambling, drinking, brawling, anti-Semitism, rapes, vandalism, insolence, and occasional attacks on adult personnel plagued many detdoma that housed streetwise youths.[41] Little wonder these institutions often failed to attract and retain qualified educators. Those not intimidated at the outset by the prospect of working with troubled adolescents often left their positions before long, fed up with the grueling work and monthly pay (when it materialized at all) lower even than that of teachers in schools for “normal” pupils.[42] Congresses of concerned officials and investigations of detdoma identified a crying need for more trained staff, especially in the growing number of institutions for “difficult” residents. Detdoma did attract people of generous spirit, prepared to shoulder considerable sacrifice to assist abandoned juveniles. But the institutions also served as refuges for those who could not find or hold jobs elsewhere and who viewed their positions as little more than nests in which to live off supplies intended first of all for the children.[43]

Despite the abundant and often overwhelming hardships faced by detdoma during the Revolution’s first half-decade, their portrait should not be painted solely in black. Studies did find most institutions in miserable condition, but a minority received favorable reports. Comparatively clean and adequately equipped, they left an encouraging impression, even if they also displayed room for further improvement. Where their histories are known, one finds almost invariably that they faced the same problems besetting detdoma in general—dilapidated facilities, few supplies, and unruly inhabitants. But eventually, sometimes not until the passage of several trying months or even a few years, signs of progress began to reward the efforts of a dedicated staff. Workshops, schools, clubs, kitchen gardens, and livestock came to occupy the children’s energies, while flight and theft faded to occasional nuisances. Thus nurtured, most youths in these establishments gave reason to believe that they had broken, or were breaking, their bonds with the street and might well join society before long as productive, well-adjusted citizens.[44]

A detdom for difficult juveniles in Moscow provided a vivid illustration of this transformation. Prior to the arrival in December 1920 of new teachers and administrators, the youths did whatever they pleased, completely intimidating the staff. Some disappeared for hours each day, taking food and clothing along to sell in the Sukharevskii Market. Others remained in the detdom and engaged in such “manual labor exercises” as destroying furniture to make sleds and slamming a piano with wet towels to frighten a teacher when she tried to “meddle” in their lives. Many were extremely volatile, quickly vexed by the slightest obstacle, and prone to fly into rages and fights on trivial grounds. They shouted from morning to night, even while conducting mundane conversations. In short, numerous obstacles greeted the new staff’s effort to bring rudimentary decorum to classes, meetings, and meals. Activities requiring collective discipline and the observance of rules, such as team sports or simple theatrical productions, were completely beyond the residents at first. When rehearsing a play, for instance, some actors saw no need to wait for others to finish speeches before sounding forth with their own. Informed of the coherence yielded by the delivery of lines in proper order, they stormed from the room. Though the new group of educators had resolved initially to abjure compulsion, they soon concluded that basic rules of behavior would have to be introduced, beginning in the dining room. Here children leaped up from the table throughout the meal, screamed whenever they pleased, made obscene gestures, and ate out of their hands. It was therefore announced that no one who arrived late, left the table early, or ate sloppily would receive any more food that meal. This tactic soon diminished chaos in the dining room, though shouting was not overcome for several months.

As time passed, the staff’s devotion to the detdom won the youths’ trust. Thefts and destruction of property shrank to trivial proportions. Abusive and hysterical inhabitants, though still capable of rough moments, grew more stable and dependable. Eventually the group even received invitations to attend festivities in other institutions, something their reputation for wildness had earlier precluded. To be sure, the success did not extend to all children, a handful of whom remained immune to the adults’ efforts and finally ran away or were conveyed to relatives or other facilities. But isolated setbacks notwithstanding, the detdom made striking progress from year to year—organizing clubs, excursions, and schooling, for example—and by 1923 bore few traces of its former seedy character.[45]

A perusal of such histories indicates that detdoma required nothing so much as an energetic, dedicated staff. Without instructors and administrators devoted to weaning juveniles from the street, even a well-equipped facility could achieve little. It should also be noted that the Moscow detdom featured here contained six teachers and only 25 to 38 children. Had the staff been swamped by 100–150 boys and girls, a common occurrence in this period, the institution’s accomplishments would have remained modest. The most saintly corps of educators could not absorb an unlimited number of starving or unrepentant youths and expect, with completely inadequate supplies and facilities, to reshape their lives. In any case, ardent, skilled personnel did not represent the norm in detdoma. Thus, despite individual successes, these institutions taken collectively made little progress toward the goal of rehabilitating waifs in the first five years of Soviet power.

| • | • | • |

As described in the preceding chapter, Narkompros (and the Commissariat of Social Security from 1918 to 1920) intended to rely on hundreds of Juvenile Affairs Commissions to replace the courts in deciding proper treatment for young lawbreakers. No longer regarded as criminals, the children were to be spared traditional trials and incarceration. Although the plan envisioned a network of commissions reaching nearly every municipality down to the district level, implementation proceeded slowly. By March 1920, when Narkompros assumed responsibility for the commissions, only about 50 had been established, nearly all confined to the largest cities. As the ranks of homeless youths (and thus juvenile thieves) continued to increase, so too did the number of commissions. In the Russian Republic the total reached 190 by May 1921, 209 by September 1922, and 236 by December. Thereafter the figures leveled off at 273 in 1923 and 275 in 1924—in other words, roughly paralleling the opening of new receivers and still approximately three hundred short of the goal.[46]

The number of children processed by a commission in any given area depended on numerous factors, including the board’s efficiency and the region’s share of offenders. In Petrograd, ravaged during the War Communism years but far removed from the subsequent Volga famine, the caseload of the city’s commission rose steadily from 5,888 in 1918 to 8,404 in 1919 and peaked at 9,106 in 1920. As local conditions improved, volume dropped to 7,902 in 1921 and then plunged to 4,520 the following year. Moscow’s commissions, by contrast, were busiest during the famine year of 1921, handling by one account 14,307 youths (down to 7,121 in 1922).[47] Figures available for the Russian Republic as a whole must be regarded merely as rough estimates, given the incomplete compilation and reporting of information from the provinces. According to one source, commissions decided the cases of 54,424 juveniles in 1921, while a second author estimated that the actual total approached 85,000. A work published later in the decade listed the number who appeared before commissions as 50,580 in 1922, 43,484 in 1923, and 48,945 in 1924.[48]

The volume of children passing through commissions was affected not only by the country’s supply of delinquents and commissions at any particular time, but also by periodic changes in the law. The decree of January 1918 had stipulated that commissions decide the cases of all minors (defined then as anyone under seventeen), stressing that adolescents no longer be sent before courts or to prisons. But the relentless increase in delinquency that accompanied the epidemic of homelessness during the next few years overwhelmed commissions and convinced the government to enact stricter measures. Thus Sovnarkom’s decree of March 1920, while increasing by one year the maximum age of youths sent before commissions, permitted the transfer of those fourteen through seventeen to the courts if commissions considered inadequate the “medical-pedagogic” measures at their disposal.[49] Similar concern over a country saturated with young bandits colored the Russian Republic’s new Criminal Code, issued in June 1922, which reduced from eighteen to sixteen the minimum age at which an offender’s case went directly to a court. Only for those fourteen and fifteen years old did commissions retain authority to decide whether they or the courts should determine treatment.[50]

In the summer of 1922, the expansive scale and brazenness of juvenile crime prompted a series of interagency meetings to consider transferring from Narkompros to the Commissariat of Justice all responsibility for rehabilitating delinquents. Although Narkompros managed in the end to retain its Juvenile Affairs Commissions, an amendment to the Criminal Code approved by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in October 1922 further reduced their competence. More specifically, the new wording granted courts the sole authority to decide in each instance whether they or commissions would hear cases of children fourteen and fifteen years old. These provisions of the Criminal Code and the October amendment, rather than a significant abatement of crime, appear to account for most of the sharp drop in the number of youths coming before commissions in 1922. More now traveled straight to the courts.[51]

Meanwhile, Narkompros petitioned the All-Russian Central Executive Committee to repeal the October amendment. Among the agency’s arguments numbered a reminder that the courts possessed only a handful of juvenile institutions (administered at the time by the Commissariat of Internal Affairs) to which they could sentence the tens of thousands of adolescents now destined by the Criminal Code to appear before them. Either an expensive network of detention facilities would have to be constructed—a most unlikely development—or courts would sentence minors to confinement in regular prisons cheek by jowl with adult criminals. Habits and skills acquired here would likely remain beyond the ken of rehabilitation programs. Appeals along these lines may well have struck home, for in July 1923 Narkompros’s commissions regained the responsibility stripped from them by the previous year’s amendment to the Criminal Code.[52]

By no means every local commission, court, and police force followed nimbly, or at all, the series of legal changes sketched above. Even when agencies learned of the latest guidelines and attempted to implement them, they often lacked instructions or resources adequate to insure uniform application from one district to the next. More than a few officials regarded vagrant adolescents as hopeless criminals, “morally defective” and impossible to salvage, who deserved the same treatment as adult thieves. Authorities who shared this view sometimes refused to recognize the competence of Juvenile Affairs Commissions and locked up underage offenders in prisons and labor camps. In contrast, others flooded commissions with delinquents at the first opportunity, apparently seeking to shift the burden of feeding and supervising them onto different shoulders.[53] A minority of commissions behaved much like courts themselves and referred to their decisions—including fines, forced labor, and imprisonment—as “sentences.” To mark major holidays, a few granted early release through amnesties similar to those accorded adult criminals. This, Narkompros superiors complained, made no sense if one supposed that the children had been placed in settings designed to provide a healthy upbringing.[54]

Once a boy (rarely a girl) appeared before a commission, its members were to discuss his background and the case’s particulars in order to select a suitable course of rehabilitation. As shown in table 2, the action taken was often nothing more than a conversation, reprimand, or the youth’s placement with relatives. Unregenerate offenders (including most veteran street children) found themselves routed to institutions or transferred to the courts.[55] The data for 1922 reveal that courts received nearly a fifth of all cases, reflecting (temporarily) the terms of the new Criminal Code and its October amendment.

| 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | First half of 1924 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: V. I. Kufaev, Bor’ba s pravonarusheniiami nesovershennoletnikh (Moscow, 1924), 13. | ||||

| Conversation or reprimand | 26.5 | 23.9 | 25.4 | 28.6 |

| Place under supervision of a social worker | 6.2 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Place under supervision of parents or relatives | 14.8 | 11.4 | 13.7 | 16.3 |

| Dispatch to home region | 3.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| Place in a job | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 |

| Place in a detdom | 4.0 | 4.2 | 7.2 | 5.9 |

| Place in a detdom for “morally defective” youths | 5.8 | 7.2 | 12.5 | 8.6 |

| Transfer case to the courts | 7.1 | 18.8 | 11.9 | 9.7 |

| Halt proceedings | 26.6 | 26.4 | 18.4 | 20.1 |

| Other measures | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 3.0 |

| TOTAL | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

The three members (representatives from Narkompros and the commissariats of health and justice) who made up a Juvenile Affairs Commission could not themselves assemble pertinent information on all cases and supervise the implementation of decisions reached in their hearings. For support, they were expected to rely on social workers, as explained in the previous chapter. Many Narkompros offices, however, especially at the district level, lacked funds to provide such personnel, thereby reducing the number of cases commissions could handle and the effectiveness of their rulings. In these straits, commission members relied on their own efforts or cast about for assistance from the Children’s Social Inspection, the police, and recruits from the ranks of schoolteachers, Komsomol members, and officials in local soviets. Most people thus enlisted had to perform their new tasks on top of prior obligations and without extra pay—not a recipe for swift, enthusiastic work.[56] Apart from this, commissions here and there were crippled by the frequent turnover and poor quality of their own members. Some provincial offices of the three commissariats ranked work with juvenile delinquents low among their responsibilities and shunted less able employees to commissions. These factors, and severe budget cutbacks brought by the New Economic Policy to Narkompros branches, idled local commissions on occasion for weeks and even months.[57]

Nevertheless, many commissions, especially those in large cities, met regularly—roughly twice a week on average for the country as a whole and nearly every day in Moscow—hearing hundreds or thousands of cases in a year.[58] But even the most efficient, well-staffed commission sometimes found its work frustrated by the inadequate number of institutions to which offenders could be sent for rehabilitation. In fact, “inadequate” appeared too generous a characterization in numerous regions, where no detdoma at all existed for the “morally defective.”[59] As a result, commission members frequently found themselves forced to adopt measures they regarded as inappropriate for the individual before them. If a child required placement in an institution, and no facility contained an opening, what could they do? This quandary goes far in explaining the large percentage of youths dismissed with merely a reprimand or channeled to relatives or home provinces. Some commissions also turned to the opposite extreme among their options and disposed of cases by shunting them to the courts.[60] Juveniles so transferred, in other words, included not only those deemed incorrigible but candidates considered suitable for Narkompros’s custody, if only the appropriate institutions were available.

After reaching the courts, adolescents sentenced to “deprivation of freedom” were generally expected to spend this period in labor homes (trudovye doma) intended exclusively for minors and administered by the commissariats of justice (until 1922) and internal affairs (through the remainder of the decade).[61] There appear to have been three labor homes functioning in or near Moscow, Petrograd, and Saratov in 1921, joined by a fourth in Irkutsk the following year. The intended total capacity of these facilities—531 youths—far exceeded the number actually housed, 310, owing to shortages of equipment and supplies. By 1923, published lists included three more locations, adding the cities of Khar’kov, Kiev, and Kazan’ to the four earlier sites. Thereafter the number of institutions continued to grow slowly, reaching ten by 1926–1927, with a joint capacity of 1,883.[62] This handful of structures could not begin to accommodate the thousands of delinquents nurtured by the country’s misfortunes, and courts found no alternative but to send young offenders to prison. In 1922, approximately three-quarters of all children deprived of freedom landed in regular penal facilities rather than in labor homes. Even Juvenile Affairs Commissions occasionally consigned teenagers to prisons, despite legal prohibitions.[63]

Youths sentenced to prison were to remain isolated from adult inmates in order to avoid the grownups’ unsavory influence. In theory, sections of prisons shielded by this quarantine might then function much like labor homes. But the reality of prison life subverted partitions in most facilities, and children mingled with other convicts.[64] Whatever else a boy acquired in this environment, it was not rehabilitation. Viewed by older prisoners as a golets, plashketa, shket, or margaritka—all underworld terms denoting an uninitiated and vulnerable individual, ripe for plucking—he likely suffered numerous rapes in their domain.[65] He also learned from a ready corps of instructors the criminal world’s thieving techniques, language, and diversions. While he may have entered prison relatively unscarred, forced by hunger to take up petty thievery, he walked out of the institution in all probability a more formidable practitioner of the craft that had led originally to his confinement.[66] Thereafter, especially if he lacked relatives able and willing to support him, the imperatives of survival pulled him back among the besprizornye. He returned to them, however, with a new store of knowledge (and possibly venereal disease) to pass on to those less experienced, whom he beheld in much the same light as adult convicts had appraised him in prison. Regardless of his transgressions prior to incarceration, a more hardened criminal now faced society, as chronicled by street children in song.

No impression emerges more starkly from a survey of the state’s early efforts to cope with abandoned youths than a picture of agencies con fronting a task far beyond their means. The plans begun in 1918 for rehabilitating the country’s already considerable population of homeless juveniles were shattered and swept away by the torrent of waifs, which rose relentlessly each year. As the number of children’s institutions swelled in response, conditions inside them deteriorated to a level that one journal labeled “primeval chaos.”[68] Sources routinely described re ceivers and detdoma in which education and training had given way entirely to, at best, temporary survival.[69] When the crisis receded, Nar kompros found itself presiding over a network of mostly squalid facili ties where few activities seemed both so urgent and unpromising as re habilitation. Scrutinizing this landscape at the beginning of 1923, an author in one of the agency’s journals wondered if any solution existed to the problem and worried that a bleak future on the edge of society awaited Narkompros’s wards.[70] In the months to come, the quest for remedies stoked a debate on how best to proceed—from which there soon arose a call for sweeping reform of detdoma, based in turn on a reassessment of the besprizornye themselves.

My first term in prison didn’t last long: Nothing but a third of a year. And when I came out to freedom, There was no one I did fear.[67]

Notes

1. Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 4: 166; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 163 (August 19), p. 3. In practice, some institutions bearing the name observation-distribution point (usually abbreviated in Russian as raspredelitel’) were indistinguishable from receivers; see for example Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 4: 169.

2. Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1922, no. 1: 16; Krasnaia nov’, 1932, no. 1: 36; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, 1924, nos. 7–8: 45.

3. Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 91. According to another source, the country contained 160 receivers and 50 raspredeliteli by January 1, 1922; Sokolov, Detskaia besprizornost’, 61.

4. Sokolov, Detskaia besprizornost’, 62; Otchet o sostoianii narodnogo obrazovaniia v eniseiskoi gubernii, 16–17; Otchet ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia avtonomnoi oblasti Komi na 1-e aprelia 1922 g. (Viatka, 1922), 59; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 11; Otchet tambovskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia sovetu truda i oborony za period s 1 oktiabria 1921 g. po 1 aprelia 1922 g. (Tambov, 1922), 162; Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 207; Bich naroda, 79. Where receivers did not exist, children detained for delinquency often remained in police stations while their cases were under consideration; see M. F. Kirsanov, Rukovodstvo po proizvodstvu del v mestnykh komissiiakh po delam o nesovershennoletnikh (Moscow-Leningrad, 1927), 22.

5. Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 207–208.

6. Golder and Hutchinson, On the Trail, 57, 70–71. See also A. Ruth Fry, Three Visits to Russia, 1922–25 (London, 1942), 13.

7. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 64; Gor’kaia pravda, 47; Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 207–208; Bich naroda, 79; Besprizornye, comp. O. Kaidanova (Moscow, 1926), 34.

8. For examples of receivers in Tambov province and Khar’kov disrupted by experienced besprizornye, see Otchet tambovskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 162–163; Maro, Besprizornye, 333. A few receivers were established exclusively for juvenile prostitutes or other “morally defective” youths of one gender or the other. See for example Psikhiatriia, nevrologiia i eksperimental’naia psikhologiia (Petrograd), 1922, vypusk 1, 97; Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 109–114; Vasilevskii and Vasilevskii, Prostitutsiia i novaia Rossiia, 77. Such specialized institutions, however, tended to be located in or near the largest cities. Most receivers around the country admitted a wide range of besprizornye, from the naive to the unscrupulous.

9. TsGALI, f. 332, o. 2, ed. khr. 41, l. 21; Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 208; 1932, no. 1: 37; Vchera i segodnia, 132–134; Grinberg, Rasskazy, 24, 45–46, 83–85, 88.

10. Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 113; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, no. 3 (May 1923): 176–177; Grinberg, Rasskazy, 15, 55, 68; Kaidanova, Besprizornye deti, 6.

11. Na putiakh k novoi shkole, no. 3 (May 1923): 168; Puti kommunisticheskogo prosveshcheniia (Simferopol’), 1926, no. 12: 72; Grinberg, Rasskazy, 85–86; Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 113; Vchera i segodnia, 134; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 34.

12. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 178, l. 10; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 146; Otchet tambovskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 162–163; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, nos. 7–8: 8; Otchet cherepovetskogo gubernskogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta, 100.

13. This transformation eventually found sanction in guidelines published for receivers. For an example, which specified that children not be kept in a receiver for more than four months, see Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Detskoe pravo, 228–229.

14. A handful of institutions were reorganized in 1922–1923 as “experimental-model” facilities, intended from the beginning to hold children for an extended period of training before sending them on to detdoma or other destinations.

15. See for example Na putiakh k novoi shkole, no. 3 (May 1923): 168–179.

16. See for example Kommunistka, 1922, no. 1: 13; Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 4: 174.

17. For several examples of the different names borne by children’s institutions, see Magul’iano, “K voprosu o detskoi prestupnosti,” 214; Otchet vladimirskogo gubispolkoma, 55; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, no. 3 (May 1923): 80; Maro, Besprizornye, 367–380; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 29; Glatman, Pionery i besprizornye, 26–28; Statisticheskii obzor narodnogo obrazovaniia v permskoi gubernii, 141.

18. Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1924, no. 2: 15; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 18, 67; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:32–33; Glatman, Pionery i besprizornye, 26.

19. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 137; Leshchinskii, Kto byl nichem, 5; Prosveshchenie na transporte, 1922, no. 2: 15; Kommunistka, 1922, nos. 10–11: 44; Zaria Vostoka (Tiflis), 1922, no. 77 (September 19), 4; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 68 (April 24), p. 3; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:68–73; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 29–30, 41; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 27–28, 38–39.

20. Tvorcheskii put’ (Orenburg), 1923, no. 6: 10–11; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 34 (March 12), p. 3; 1921, no. 187 (September 16), p. 3; Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1923, no. 7: 59; Detskii dom, 1930, no. 4: 10. For a literary description of a detdom located in a convent, a corner of which remained occupied briefly by the nuns, see Lydia Seifulina, “The Lawbreakers,” in Flying Osip: Stories of New Russia (Freeport, N.Y., 1925; reprint, 1970), 69–72.

21. Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 14, 22, 25, 28, 30, 33; American Red Cross, box 868, file 948.08, “Report of Mission to Ukraine and South Russia by Major George H. Ryden,” November 1919. For the similar findings of another prefamine survey of detdoma, see Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 53.

22. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 28, l. 7; ibid., ed. khr. 43, ll. 3, 27; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 52; Otchet krymskogo narodnogo komissariata po prosveshcheniiu, 18; Otchet sengileevskogo uezdnogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta. Za vremia s 1-go iiulia 1921 goda po 5-e fevralia 1922 goda (Sengilei, 1922), 146; Derevenskaia pravda (Petrograd), 1921, no. 118 (September 17), p. 2; 1921, no. 120 (September 21), p. 3; 1921, no. 131 (October 5), p. 3; 1922, no. 21 (January 28), p. 2; Prosveshchenie na Urale (Sverdlovsk), 1927, no. 2: 60; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 250 (December 1), p. 3; 1922, no. 295 (January 26), p. 3; Posle goloda, 1922, no. 1: 64; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (1923), 122; Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 26.

23. Vasilevskii and Vasilevskii, Kniga o golode, 74–75. The detdoma of Samara province took in twenty to twenty-five children each day as early as May 1921. During the next two months the number rose to fifty to fifty-five youths each day, and it passed one hundred in August. See TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 66. For additional data showing sharp increases in the number of children in detdoma in several portions of the famine zone, see Gor’kaia pravda, 23; Prosveshchenie (Viatka), 1922, no. 1: 20; Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 25; Statisticheskii spravochnik, 13.

24. Walter Duranty, I Write as I Please (New York, 1935), 131. A visitor to Kazan’ during the famine described one of the city’s detdoma as follows: “The children arrived at this one at the rate of a hundred and sometimes two hundred a day, and although the director of this home was a man of order, with sound ideas on sanitation, so that the children were washed and disinfected on arrival, all this method was overwhelmed by the pressure of new arrivals and the lack of clothes. They were all crawling with lice from which typhus was carried. Nothing the man could do, with his assistants, could destroy that plague of vermin which was the curse and terror of Russian life at this time”; Gibbs, Since Then, 391–392.

25. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 27.

26. Deti posle goloda, 92.

27. Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 18–20, 22–24; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 40, 42; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, l. 56; ibid., ed. khr. 61, ll. 57, 97; Golod i deti, 40–41; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia(1923), 122; Roberts, Through Starving Russia, 40; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, no. 3: 3; Derevenskaia pravda (Petrograd), 1921, no. 131 (October 5), p. 3; Deti posle goloda, 43; Vestnik prosveshcheniia (Kazan’), 1921, nos. 6–7: 186–187. Prior to 1921, detdoma in some Volga provinces were better provisioned than many in the central part of the country. During War Communism, children were even evacuated from Moscow, Petrograd, and certain other cities to some of the Volga districts. Needless to say, the famine ended this practice.

28. Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 34; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:50–52; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 56; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 37; Pitirim A. Sorokin, Leaves from a Russian Diary—and Thirty Years After (Boston, 1950), 221–222.

29. TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, l. 4; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, ll. 17, 27; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 97; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 8, 14, 22; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:164–165; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 31; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 40, 53; Turkestanskaia pravda (Tashkent), 1923, no. 3 (January 4), p. 2; Deti posle goloda, 42; F. E. Dzerzhinskii, Izbrannye proizvedeniia, 3d ed., 2 vols. (Moscow, 1977), 1:321. Shortages of facilities, fuel, textbooks, and the like also plagued regular public schools during these years; see Stolee, “Generation,” 41–42. But detdoma were generally more vulnerable, because they had to feed, clothe, and house youths as well as provide training of some sort.

30. TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, l. 49. At a detdom in Odessa, the floor was torn out to serve as fuel for cooking meals; see Golder and Hutchinson, On the Trail, 214.

31. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 27; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 13, 22; Krasnaia nov’, 1932, no. 1: 32; Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1924, nos. 11–12: 31.

32. Vtoroi otchet voronezhskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 33; Otchet cherepovetskogo gubernskogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta, 101; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 27; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 17, 19, 22, 28, 35; Deti posle goloda, 43; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 40; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:46–47; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, nos. 7–8: 11; Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1924, no. 2: 16; Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 26.

33. Spasennye revoliutsiei, 27; Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1923, nos. 8–9: 57; Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 26; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 31, 34, 36; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 54.

34. Turkestanskaia pravda (Tashkent), 1923, no. 30 (February 10), p. 4 (regarding Samarkand); TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 28, l. 7; Vtoroi otchet voronezhskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 33–34; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 9, 14–15, 22; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 55; Deti posle goloda, 41; Maro, Besprizornye, 374; Na fronte goloda, kniga 1, 37 (regarding the revolutionary tribunal).

35. Otchet krymskogo narodnogo komissariata po prosveshcheniiu, 18; Saratovskii vestnik zdravookhraneniia (Saratov), 1926, no. 1: 24–28; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 61, l. 97; Maro, Besprizornye, 374; Otchet samarskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 140; Deti posle goloda, 43–44; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:106, 149; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1922, no. 302 (February 4), p. 3; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 13–14, 21–22, 24, 30, 35; Tvorcheskii put’ (Orenburg), 1923, no. 6: 10; Na fronte goloda, kniga 1, 36; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 54, 56; Fry, Three Visits, 13.

36. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 60, l. 154; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 86; Vestnik prosveshcheniia (Kazan’), 1921, nos. 6–7: 188; Vtoroi otchet voronezhskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 33–34; Otchet krymskogo narodnogo komissariata po prosveshcheniiu, 18; Vasilevskii and Vasilevskii, Kniga o golode, 76; Pravda Zakavkaz’ia (Tiflis), 1922, no. 11 (May 14), p. 1; Mackenzie, Russia Before Dawn, 134 (regarding Buzuluk).

37. Prosveshchenie (Viatka), 1922, no. 2: 85; Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1924, nos. 11–12: 29–30; Vasilevskii and Vasilevskii, Kniga o golode, 77–78; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 155; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:39, 52–55, 166–170, 200, 202–209; Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 124.

38. Makarenko, Road to Life 1:165–166.

39. TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, l. 42; Sibirskii pedagogicheskii zhurnal (Novo-Nikolaevsk), 1924, no. 3: 54; Artamonov, Deti ulitsy, 8; Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 116; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:98; Maro, Besprizornye, 260; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 153; Turkestanskaia pravda (Tashkent), 1923, no. 3 (January 4), p. 2.

40. For evidence of at least temporary demoralization among staff members at a number of institutions, see Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 116; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:38, 216–218; Maro, Besprizornye, 389.

41. Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 13, 37; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, 1923, no. 9: 41; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:40, 86, 88, 98–99, 127–129; Borovich, Kollektivy besprizornykh, 19–20, 24–27.

42. TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, ll. 1–2, 60, 169; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:29, 35–36, 247–248; Detskaia defektivnost’, 49.

43. Sibirskii pedagogicheskii zhurnal (Novo-Nikolaevsk), 1924, no. 3: 54; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, nos. 7–8: 14; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 38; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:248–250; Detskaia defektivnost’, 49, 59; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 50, 278. In addition, many teachers and administrators of detdoma were ignorant of, or unsympathetic toward, the pedagogic methods and goals developed by Narkompros. See Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 42, 48–49; Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 229.

44. Nash trud (Iaroslavl’), 1923, nos. 8–9: 57–59; Pravda Zakavkaz’ia (Tiflis), 1922, no. 17 (May 21), p. 4; Turkestanskaia pravda (Tashkent), 1923, no. 14 (January 19), p. 3; Zaria Vostoka (Tiflis), 1922, no. 6 (June 25), p. 3; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 42–46; Besprizornye, comp. Kaidanova, 39; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 36; Sibirskii pedagogicheskii zhurnal (Novo-Nikolaevsk), 1924, no. 3: 54–57; TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 52, ll. 2–3; Maro, Besprizornye, 350–364; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 41–43.

45. Diushen, Piat’ let, 177–205. Regarding the organization and involvement of children—not always with great success—in the daily household chores, field work, and discipline of other detdoma, see Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 116; Sibirskii pedagogicheskii zhurnal (Novo-Nikolaevsk), 1923, no. 3: 104–106; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 18; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 40; Maro, Besprizornye, 376–378; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, 1923, no. 9: 41; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:233–241; Pravda Zakavkaz’ia (Tiflis), 1922, no. 17 (May 21), p. 4; Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 73. For examples of comparatively successful circles and clubs at a number of institutions, see Shveitser and Shabalov, Besprizornye, 73–74; Sibirskii pedagogicheskii zhurnal (Novo-Nikolaevsk), 1923, no. 3: 102–103; Makarenko, Road to Life 1:107–108; Maro, Besprizornye, 379; Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 2: 115.

46. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 190, l. 1; Kufaev, “Iz opyta,” 90; Drug detei (Khar’kov), 1926, no. 10: 4; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 137. For slightly different figures, including an estimate that the country required an additional two hundred commissions in 1922, see Sokolov, Detskaia besprizornost’, 61–62; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 91. By 1928 the number of commissions reached the neighborhood of five hundred; Kufaev, “Iz opyta,” 91.

47. Psikhiatriia, nevrologiia i eksperimental’naia psikhologiia (Petrograd), 1922, vypusk 1, 99; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 51–52. According to another source, the following numbers of children appeared before commissions in Moscow and Petrograd/Leningrad in 1922, 1923, and 1924 respectively: Moscow—8,069, 5,937, 5,399; Petrograd/Leningrad—4,098, 3,065, 3,978; see Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 140. A third work presents the following figures for Moscow commissions: 13,877 youths in 1921, 6,784 in 1922, and 4,591 in 1925; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 83n.1. One reason for the discrepancies may be that some authors present figures based on the number of cases sent to commissions, in contrast to the number of cases actually decided in any given year. Also, it is not always clear whether data include those children whose cases were passed on to the courts.

48. Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 51; Kufaev, Iunye pravonarushiteli (1924), 94; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 139. For data on the number of cases handled by commissions in many different provinces, see Kufaev, Iunye pravonarushiteli (1924), 100–101; Narodnoe obrazovanie v R.S.F.S.R., 126–159. A more recent work maintains that the number of children processed by commissions jumped to 75,100 in 1925—largely as a result of better record keeping by commissions and a more effective struggle against juvenile crime and hooliganism; see Min’kovskii, “Osnovnye etapy,” 48.

49. Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 253; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 54–55; E. V. Boldyrev, Mery preduprezhdeniia pravonarushenii nesovershennoletnikh v SSSR (Moscow, 1964), 16; SU, 1920, no. 13, art. 83.

50. SU, 1922, no. 15, art. 153; no. 20/21, art. 230; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 77, 80; Boldyrev, Mery preduprezhdeniia, 18–19.

51. Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 56–57; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 77.

52. TsGA RSFSR, f. 298, o. 1, ed. khr. 45, l. 23; Detskaia besprizornost’, 48–49; SU, 1923, no. 48, art. 479; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 77.

53. TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 13, ed. khr. 11, l. 43; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Detskoe pravo, 243; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 181; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 34, 56; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 89–90.

54. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 178, l. 22; Shkola i zhizn’ (Nizhnii Novgorod), 1925, nos. 9–10: 91; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 135; Narodnoe prosveshchenie v R.S.F.S.R. k 1924/25 uchebnomu godu, 88–89.

55. Statistics in other sources covering the country as a whole are in line with those presented in table 2. Naturally, practices varied from city to city, depending on many factors, including the availability of children’s institutions and social workers. Where, for instance, the number of besprizornye and other delinquents far exceeded the capacity of facilities for “difficult” youths, local commissions were more likely to handle cases with discussions, reprimands, or by sending the offenders to any available relatives. Some also responded by transferring a larger than average percentage of cases to the courts. For additional data on the measures adopted by commissions in the Russian Republic and individual cities (Moscow, Petrograd, Vladikavkaz, Tver’, Simferopol’, Barnaul, and Vitebsk), see Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 50–52; V. I. Kufaev, Bor’ba s pravonarusheniiami nesovershennoletnikh (Moscow, 1924), 18, 25–26; Psikhiatriia, nevrologiia i eksperimental’naia psikhologiia (Petrograd), 1922, vypusk 1, 100; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (1922), 255; Otchet tverskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia sovetu truda i oborony. No. 1 (iiul’–sentiabr’) (Tver’, 1921), 71; Otchet krymskogo narodnogo komissariata po prosveshcheniiu, 19; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 101, ll. 1, 7, 9, 11, 13, 21–25; ibid., ed. khr. 105, ll. 1–6, 9–14. During the remainder of the decade as well, commissions concluded between 40 and 50 percent of their cases with either a conversation/reprimand or the child’s dispatch to relatives. For data (roughly similar to that in table 2) on measures adopted by commissions through 1929, see Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 84; Narodnoe prosveshchenie v RSFSR 1927–28 god (Moscow, 1929), 180–181; Kufaev, Iunye pravonarushiteli (1929), 28; Kufaev, “Iz opyta,” 97.

56. Vtoroi otchet irkutskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (oktiabr’ 1921 g.–mart 1922 g.) (Irkutsk, 1922), 119; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 121; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (1922), 255; Vtoroi otchet tverskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia sovetu truda i oborony (oktiabr’ 1921 g.–mart 1922 g.) (Tver’, 1922), 53; Otchet cherepovetskogo gubernskogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta, 100; Otchet stavropol’skogo gubekonomsoveshchaniia sovetu truda i oborony za aprel’–sentiabr’ 1922 g. (Stavropol’, 1923), 34; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 133; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 178, l. 11. The Children’s Social Inspection was also far understaffed (or did not exist at all) in many parts of the country; see TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 147, ll. 4, 6–7; Otchet o sostoianii narodnogo obrazovaniia v eniseiskoi gubernii, 17; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 88; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 187; Vtoroi otchet voronezhskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 34. The shortage of obsledovateli-vospitateli continued to hinder the work of commissions in the middle and later years of the decade; see TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 190, l. 1; Kufaev, Pedagogicheskie mery, 34; Poznyshev, Detskaia besprizornost’, 75; Narodnoe prosveshchenie v R.S.F.S.R. k 1925/26 uchebnomu godu, 70; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 132–133; Shkola i zhizn’ (Nizhnii Novgorod), 1927, no. 11: 10.

57. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 193, l. 5; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 79, 82–83; Otchet o sostoianii narodnogo obrazovaniia v eniseiskoi gubernii, 17; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 138; Ezhenedel’nik sovetskoi iustitsii, 1925, nos. 44–45: 1366.

58. Province-level commissions met, on average, between two and eight times each month, while district-level commissions typically convened not more than four times a month. Regarding the frequency of commission meetings around the country, see TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 101, ll. 1, 7, 9, 11, 13, 21–25; ibid., ed. khr. 105, ll. 1–6, 9–14; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 138; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (1922), 255; Magul’iano, “K voprosu o detskoi prestupnosti,” 209.

59. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 178, l. 3; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 18, 32; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 82.

60. Otchet cherepovetskogo gubernskogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta, 100; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, no. 6: 11; nos. 7–8: 32; Kommunistka, 1921, nos. 14–15: 7; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 34, 36; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 85, 88; Kufaev, “Iz opyta,” 98.

61. Institutions of this sort occasionally bore the title of reformatory (reformatoriia or reformatorium), especially in Ukraine. See the previous chapter for more on the role envisioned for labor homes.

62. Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 52; TsGA RSFSR, f. 298, o. 1, ed. khr. 45, l. 23; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 61–62; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 156–157; Min’kovskii, “Osnovnye etapy,” 46; Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 257–258; Administrativnyi vestnik, 1926, no. 12: 38. Data in some sources differ slightly. In the middle of the decade, for instance, one author lists six labor homes, with a total capacity of 858 youths, in or near Moscow, Nizhnii Novgorod, Petrograd, Saratov, Tomsk, and Verkhotur’e; Poznyshev, Detskaia besprizornost’, 113. Such differences should not obscure the conclusion that these institutions existed in minuscule numbers. On rare occasions, Juvenile Affairs Commissions themselves sent offenders directly to labor homes. See for example Vtoroi otchet irkutskogo gubernskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia, 119.

63. Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 62–63; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 52; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 156; Sokolov, Spasite detei! 52; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 9; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 63, l. 2; Maro, Besprizornye, 182; Juviler, “Contradictions,” 272; Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 257. In Kursk province Juvenile Affairs Commissions, lacking facilities in which to hold children while preparing to hear their cases, sought to place some temporarily in prisons (in rooms supposedly free of exposure to adult inmates); see Narodnoe prosveshchenie (Kursk), 1922, nos. 3–4: 80. For an autobiographical sketch of a youth caught breaking into a house and sentenced (together with two young companions) to a year in prison, see TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 55, l. 12. In 1921, juveniles, including those in labor homes, accounted for 1.1 percent of the Russian Republic’s total prison population, a share that rose to 1.4 percent in 1922. Data for Moscow province alone provide a figure of 7.9 percent in 1921. See Detskaia besprizornost’, 46; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 62; Manns, Bor’ba, 12.

64. Kufaev, Bor’ba, 11; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 12; Detskaia besprizornost’, 48. Books, articles, and reports (presented at meetings devoted to the struggle with besprizornost’ and delinquency) often condemned the placement of juveniles in regular prisons and urged that they be removed to an expanded network of labor homes and similar institutions. For a sampling, see TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 13, ed. khr. 11, ll. 42–43; Poznyshev, Detskaia besprizornost’, 131; Detskaia defektivnost’, 43. Juveniles were supposed to receive sentences at least one-third shorter than those imposed on adults imprisoned for similar crimes. For details on sentencing procedures for juvenile delinquents and information on the lengths of sentences, see Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 58–59; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 53; Gernet, Prestupnyi mir, 212.

65. Sokolov, Detskaia besprizornost’, 27; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 30–31.

66. Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 187; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 152; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 30; Sokolov, Detskaia besprizornost’, 26; Maro, Besprizornye, 178; Molot (Rostov-on-the-Don), 1925, no. 1144 (May 30), p. 5.

67. Administrativnyi vestnik, 1926, no. 12: 37–38; Maro, Besprizornye, 181, 183, 207 (for the verse). These considerations prompted Maro to argue (p. 230) that “the imprisonment of youth in Soviet Russia is a direct blow against the achievements of October.” For an autobiographical sketch of a besprizornyi turned back onto the street after serving time in prison, see TsGALI, f. 332, o. 1, ed. khr. 55, l. 12. One author contended that the serious problem of juvenile crime in the middle of the decade could be explained in large part by the activities of numerous youths, imprisoned for lesser offenses in earlier years, who had now graduated back onto the street from prison academies of crime; see Administrativnyi vestnik, 1926, no. 12: 38.

68. Vestnik prosveshchentsa (Orenburg), 1926, no. 2: 23–24; Gor’kaia pravda, 24; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 37; Statisticheskii spravochnik, 13.

69. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 61, l. 97; Golod i deti, 39; Prosveshchenie na transporte, 1922, no. 2: 24; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 144; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 13, 24; Na putiakh k novoi shkole, 1924, nos. 7–8: 45; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 183; Tizanov and Epshtein, Gosudarstvo i obshchestvennost’, 35–36; Prosveshchenie na Urale (Sverdlovsk), 1927, no. 2: 60. Narkompros itself, along with other agencies, instructed local administrators of children’s institutions (who had little choice in any event) to shift their focus from providing an upbringing to saving as many lives as possible. Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 37; Gor’kaia pravda, 23; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 47, l. 10.

70. Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 2: 76.

| • | • | • |

The Street World

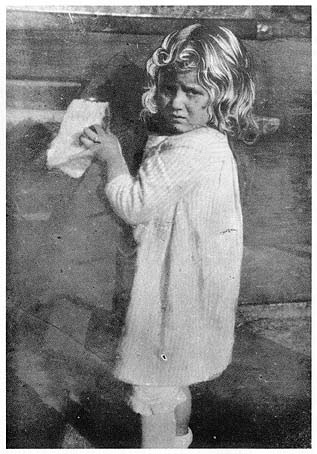

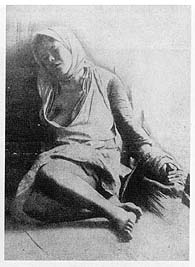

A waif noticed by American Red Cross personnel as she wandered through Irkutsk’s freight yards in 1919.

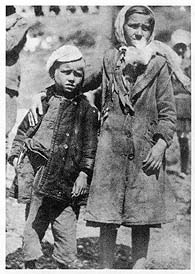

American Red Cross representatives in Siberia during the Civil War encountered this homeless girl, who approached them with the words "Please help my brother!"

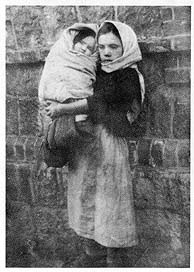

A homeless girl with her infant brother in Siberia during the Civil War.

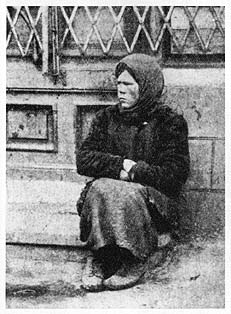

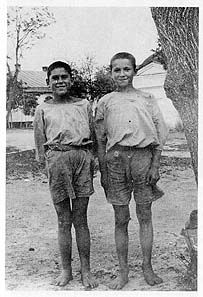

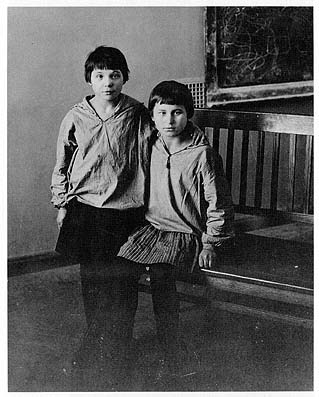

Homeless youths photographed at large around the Soviet Union.

Homeless youths photographed at large around the Soviet Union.

Homeless youths photographed at large around the Soviet Union.

Homeless youths photographed at large around the Soviet Union.

A street girl in Moscow featured on the cover of an émigré publication.

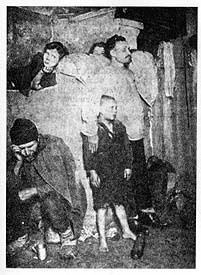

Waifs seeking refuge in a vacant shed.

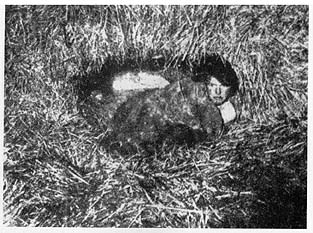

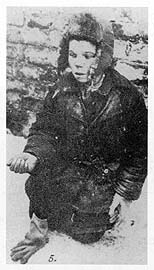

A boy discovered in a haystack outside Saratov.

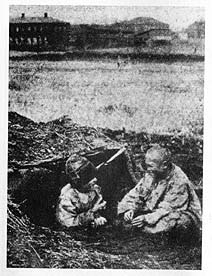

A pair at the mouth of their burrow near Khar’kov (where they lived before entering an institution).

A group huddled for warmth in a garbage bin.

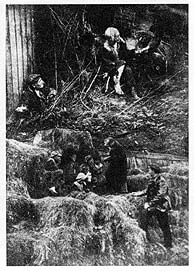

Two pictures spliced together—each showing children discovered living in a dump.

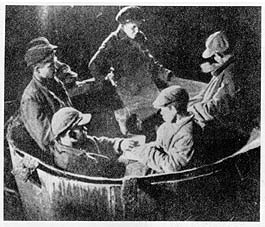

Accommodations in a caldron used by construction workers during the day to melt asphalt.

A boy observed living in a den of adult thieves in Saratov.

Four young travelers in their "berths" underneath trains.

Four young travelers in their "berths" underneath trains.

A beggar.

A scuffle over begging receipts.

Drawings by former besprizornye in Khar’kov showing street children stealing luggage from a train car (fig. 20), belongings of people sleeping overnight in a station (fig. 21), produce and the contents of a pocket (fig. 22), and cigarettes (fig. 23).

Drawings by former besprizornye in Khar’kov showing street children stealing luggage from a train car (fig. 20), belongings of people sleeping overnight in a station (fig. 21), produce and the contents of a pocket (fig. 22), and cigarettes (fig. 23).

Drawings by former besprizornye in Khar’kov showing street children stealing luggage from a train car (fig. 20), belongings of people sleeping overnight in a station (fig. 21), produce and the contents of a pocket (fig. 22), and cigarettes (fig. 23).

Drawings by former besprizornye in Khar’kov showing street children stealing luggage from a train car (fig. 20), belongings of people sleeping overnight in a station (fig. 21), produce and the contents of a pocket (fig. 22), and cigarettes (fig. 23).

Groups of waifs playing cards, a favorite pastime among those accustomed to the street. The trio in figure 24 is perched on top of a train.

Groups of waifs playing cards, a favorite pastime among those accustomed to the street.

Groups of waifs playing cards, a favorite pastime among those accustomed to the street.

Patterns for tattoos worn by children at the Moscow Labor Home.

| • | • | • |

Responses to the Problem

A published list of vanished children, similar to many other rosters issued in certain periodicals during the 1920s. The title reads: "Help Find the Children!" A much shorter list of youths searching for parents and other relatives follows at the bottom of the page.

A poster issued in 1922 as part of a public campaign to achieve the goal proclaimed in the placard’s title: "Not a Single Besprizornyi in the USSR!"

A postage stamp sold to raise money for aiding besprizornye. The spiraling banner proclaims: "Children are the builders of the future."

Street boys at an asphalt caldron. This drawing (with varying captions) appeared from time to time in the newspaper Izvestiia as part of a long-running effort to involve citizens in the struggle to eliminate juvenile homelessness. The title reads: "Remember the besprizornye!" The caption below adds: "Assistance to besprizornye is the obligation of each Soviet citizen."

Policemen marching off a group of Moscow’s besprizornye in 1918.

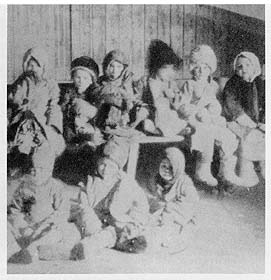

Groups of street children just after their roundup in Zaporozh’e (fig. 33) and Khar’kov (fig. 34).

Groups of street children just after their roundup in Zaporozh’e (fig. 33) and Khar’kov (fig. 34).

Abandoned offspring (evidently gathered up already by officials) waiting in a train station.

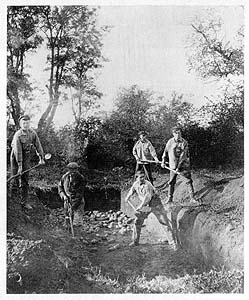

Initial processing of boys removed from the street.

Haircuts were a common measure taken against lice. The group in figure 37 has lined up outside a train dispatched during the famine to provide medical care and food.

Haircuts were a common measure taken against lice. The group in figure 37 has lined up outside a train dispatched during the famine to provide medical care and food.

| • | • | • |

Institutions

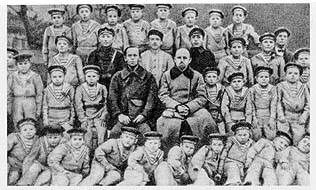

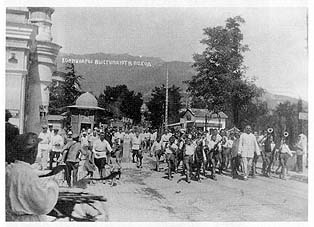

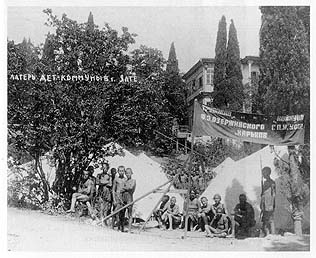

Children and staff at a detdom established with resources from the secret police in the Kuban’.

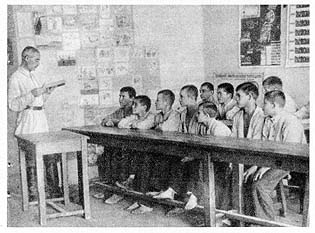

A lesson in the secret police’s labor commune at Bolshevo.

Reading at an unidentified institution for besprizornye.

A clinic for juvenile cocaine users from the street.