5. Women in Wills: Widows and Wives

The Puigcerdá notarial collection, unusually numerous and rich, recurrently offers a codex devoted to wills alone, essentially Christian wills. An example is the Liber testamentorum by the notaries Mateu d’Alb and Bernat Mauri, for the period 24 June 1306 to 24 June 1307. Among the many testaments recorded during that year, the codex supplies four fine Jewish wills. Since all four were drafted within the same community and within the short span of two months, they offer a group portrait of their society. One will is from a widow, two are by wives with husbands living, while another shows a husband providing for his wife. An extrinsic will, by a widow from Valls in Catalonia, balances this offering—two widows and two wives.

In Jewish law a widow could not inherit from her husband. In practice, however, the husband’s assets often came into the widow’s hand technically as the delayed gift, or tosefet increment, promised in the marriage document, or ketubah. A place in the family residence, household articles, and clothing would commonly remain to her. Her dowry also came back to her, often reckoned more highly than the value of goods originally brought to the marriage. Cheryl Tallan has studied the Jewish widows of northern Europe, using both responsa and non-Jewish sources. She has found the more affluent and comfortable among them enjoying, in the private and the economic spheres, “a position of power and authority far greater than that of [their] married sisters.” Renée Melammed similarly finds the Spanish Jewish widow of means a free and powerful figure, though her evidence is from the post-expulsion Sephardic diaspora to 1550.[1] The wills analyzed thus far have been mostly by men, though women as frequently seem to have made wills. Here at Puigcerdá, part of the Majorcan kingdom as well as capital of the inland Pyrenean county of Cerdanya, this one codex allows us to confront a series of women contemporaries and neighbors and formally address the theme of women’s wills.

| • | • | • |

The Widow Regina

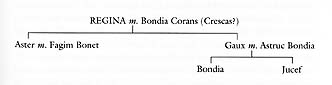

On 23 October 1306, Regina, the widow of Bondia, dictated a fairly elaborate testament.[2] “First of all I order my body buried,” presumably by norms previously conveyed to the family. Regina then provides legacies for six friends; if these are relatives or in-laws, the usual clues are lacking. She leaves 100 sous to Jucef Cohen (“Choen”), 30 to Isaac (“Isach”) of Soall, 30 “to the heirs of the deceased Jucef of Soall,” 20 “to Mometa the Jewess,” 100 to Mancosa the widow of Abraham of La Rochelle (“de la Rotxela”), and 50 “to Aster the sister of the said Mancosa.” At this point Regina interrupts the list to assign 100 sous to “some charity, for my soul, on the day of my death.”

She then takes up her immediate family, leaving 100 sous “to my daughter Aster, the wife of Fagim Bonet the Jew, for the share and inheritance belonging to her in my goods, in which (and in that dowry she had at the time of her marriage) I constitute her my heiress.” The money here is designated as Barcelona sous, which probably should be understood of all the other more general entries. Regina also left “to Gaux, daughter of myself and my aforesaid deceased husband,” another 100 sous, characterized by the same dowry and heiress phrases; Gaux’s husband is mentioned by name, Astruc Bondia. Finally, “for my soul, I leave as an alms [elemosina] for the Jews of Puigcerdá, out of love of God, my bed with all bedclothes and furnishings, which is to stand in the synagogue of the aforesaid Jews.” Elemosina in the singular here may be a charitable fund (Catalan almoina) or even a hospice/almshouse, such as the espital that Huesca’s Jews maintained from the 1160s.

Though a synonym for synagogue, scola may mean here the Bet ha-Midrash synagogue with its yeshiva, since the bed is to stay in the scola. Even in that House of Studies, sleeping accommodations were not usual, but an exception was made for scholars in full residence. The term scola here invites comment. J. M. Millás Vallicrosa has suggested that the usage derives from the instructional function in Bible and Talmud to youngsters at the synagogue. For Barcelona he distinguishes between the scola major, or main synagogue, the scola menor of the women, and the scola dels párvols (of the little ones) or hospital de l’almoyna (almshouse). In reviewing the rights of Majorca’s Jews, Jaume III defined the term. “The Jews legitimately have their scola or some building whether owned or leased, for prayer according to the Mosaic law, rites, and customs of the Jews, in the aforesaid city, where they have had a synagogue elaborate and exceedingly beautiful, and a building for prayer elsewhere” in the city. The king denied that the Majorcan Jews at the time wanted to build a new synagogue, because legally “new” applied only to the introduction of a synagogue in a locality lacking one; the present scola “is instead a repair and rebuilding of the old, which we allow to be called not a synagogue but a scola or house of prayer.”[3]

The medieval tendency to unite the functions of synagogue (prayer with some study) and house of study of Bet ha-Midrash (religious study with some prayer) may explain the dual terminology here of synagogue/scola. Are the two institutions distinguished, but in a single complex, in a rebuke by Jaume II in 1304 to the Jews of Valencia city? “You have gone beyond bounds, for you have constructed and fashioned your synagogue [sinagoga] and Bet ha-Midrash [almidraz] higher and larger than was allowed or proper. We have ordered and made you reduce this synagogue and Bet ha-Midrash to the original and proper status.” The singular possessive pronoun is open to the interpretation that the king sees both institutions as effectively synonymous.[4]

To return to Regina’s will. She now names as her executor her son-in-law “Astruc Jucef the Jew to whom I give license, etc.” She designates “as universal heirs in all my other goods, wherever and whatever they are, Bondia and Jucef my grandsons, the sons of the deceased Astruc Bondia the Jew.” Eight witnesses are listed, four of whom were Jews: Mateu d’Olià, Arnau Payleres, Ramon Rahedor, Astruc de Besalú, Jacob (ben) Abraham Cohen (“Choen”), Bernat Duran, Jucef Abraham, and Vidal “the son of” (ben) Astruc Cre(i)xent. A concluding note shows the executor paying 5 sous as fee to the notary. Three lines drawn from top to bottom through the text indicate that it was vacated or a formal copy was issued to the heirs.

Several aspects of the will invite comment. Regina was doubtless dictating the will in dialogue with the notary; at one point she begins to refer to the community’s administrators, in connection with the special charity on her death day, but interrupts herself in order to add a final legacy for her friend Aster, not returning to her expression about the administrators. The deleted phrase “I order that the secretaries” is a glimpse of the ne’emanim, officials of the aljama’s administrative board, and their role in such charitable actions. The amounts left to charity are small; this commonly meant that more substantial contributions had been separately established beforehand. The legacies are reasonably substantial as pleasant gifts—four of 100 sous, and others of 50, 30, and 20—but they suggest that the bulk of the inheritance passed to the two nephews as universal heirs.

Some of the families whose members appear are also found in the Liber Iudeorum a decade or so before: the Bonet, Soall, Choen or Cohen, and Cre(i)xent. In this will the Cohen, Cre(i)xent, and Soall have prominence. Bonet, Cohen, and Cre(i)xent appear also in the Perpignan registers, as might be predicted from the close political and commercial unity of Puigcerdá and Perpignan. (Soall does not turn up, unless the several Scal persons are a variant.) The first names of the will’s families, though common enough, also occur in the Liber lists: Abraham, Astruc, Bondia, Fagim, Isaac, Jacob, Jucef, Mometa, Regina, and Vidal. The testator’s own surname is a puzzle. It seems to be Coras with overstroke (Corans? or Crescas?), but apparently turns up as Comte in Delcor’s transcription from the Liber. “Regina uxor Bondia Comte” there loans 78 pounds, 1,934 sous, and 97 pence of Barcelona money. Perhaps the name Cresques is meant. Her loan operations indicate property far beyond the total sum of 630 sous in the will, pointing up again the supplementary nature of such wills. A family tree, without attempting to conjecture the order of birth of the children, shows:

Eighteen Jews appear in the will, most of the names reflecting the Catalan environment. The cognate Occitan culture and language may also have been at the root of some or all of the names, of course, and can be seen explicitly in Abraham of La Rochelle. Astruc of Besalú’s name announces his or his family’s connection to Catalan Besalú. The strong Arabic orientation of the Majorca will of Salema, the son of Aaron B. Aarde, in chapter 4 above, is missing here. Both Christians and Jews in Catalonia used the women’s names Aster (star, but also for Ester), Gausax (a variant of Goigs), and Regina or Reina. Bonet, a diminutive of Bo, and Bondia were also common to Christians and Jews there. Soall may be a toponym, since it has a preceding de; I can find only one place of that name, a physical feature in the nearby Valle de Aran. Seror suggests Soual l’Etape in the Tarn region. If the de functions as ben, however, the biblical Hebrew names Shoval (way) and Shual (fox) may apply.[5]

| • | • | • |

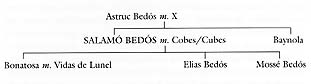

Salamó Bedós and Wife Cobes

A few folios further on, Salamó Bedós (“Bedoz”), formerly of Mazères near Toulouse in Occitania, now ill but of sound mind, entered his will in November 1306.[6] “First of all, I leave Astruc Bedós my father 20 silver pieces of Tours; likewise I order repaid and returned to him on the one hand 7 silver pieces of Tours, and on the other 1 gold florin, which I owe him as a loan.” The universal heirs must “provide for my father in food and drink well and properly until the said sums of money shall be fully paid out to him, and the said provision is not to be reckoned in the payment of the said sums of money.” Thus the father is to receive a per diem or room and board (implied by the conventional phrase) besides the sums, until those sums are repaid.

Salamó now turns to his sister Baynola, who receives 10 Barcelonan sous, and to his wife: “I testify that I had from my wife Cobes or in her name, at the time of the nuptials, 500 pounds of Tours as her dowry, which I order to be paid and returned to her immediately after my death, when she wishes.” Nothing is said of clothing and domestic goods; as seen above, these would usually remain with the widow anyway. Even Christian codes such as the Valencian Furs took such prosaic items seriously, at first denying any claim by the Christian widow on the shared bedchamber, on clothing except her daily wear, or on furnishings unless these had survived from possessions brought by her at the time of the wedding. This must have aroused opposition as heartless, for it was soon amended to award the widow bed, bedclothes, and wardrobe.[7]

Salamó appoints Cobes (also Cubes here) administrator-guardian (domina et potens) “of my universal heirs listed below and their goods, as long as she shall live.” These heirs in turn must “provide her all her life in all her material necessities well and appropriately.” Salamó has a daughter, Bonatosa, for whose possible future widowhood he wishes to provide. He orders his universal heirs to give all material care to her, “only and until Vidas of Lunel, a Jew, the husband of the said Bonatosa, will live with her and will make [his] continuous residence with her in one house under one common budget and household.” Vidas himself would then receive 10 Barcelonan sous, “which I leave him, in which (and in the dowry I gave Bonatosa with her husband) I made her my heir.” If Vidas were already dead or should die “within the space of two years coming up after my death,” the other universal heirs below “are bound to marry off the said daughter suitably” and to give her as dowry the 25 pounds of Tours Salamó is putting aside here. Finally, he establishes as universal heirs his sons Elias and Mossé Bedós. “And I substitute, wish, and order that if either of my said sons should die at any time without legitimate offspring,” the remnant of his legacy be equally divided between the brother “alive and surviving,” Cobes, and Bonatosa.

Salamó’s father Astruc Bedós witnessed and approved the provisions. Seven “invited witnesses” (testes rogati) follow: Salamó of Valencia, Deulosal of Besalú, Salamó Jucef, Jacob Astruc, and Rubèn Jucef—“all Jews”—with Arnau of Urtx and Ramon Serra, “Christians.” This testament essentially leaves Salamó’s worldly goods to his sons, but it puts both sons and goods under their mother during her lifetime, while providing a decent living for his own father and for the wife and unmarried daughter. The circumstances of the married daughter seem odd, separated from her husband; the provision here seems designed to mend a broken marriage. The toponymical surnames—Besalú, Lunel (just northeast of Montpellier), and Valencia—suggest something of the mobile commercial society of the Catalan-Occitan lands; Urg, now Urtx, is near Puigcerdá. Among the Jews’ first names, the witness Deulosal or “God save him” was perhaps a cross-name for Hebrew Isaiah or Yeshua/Joshua, as the husband Vidal or Vital was a secular name for Hayyim, or “life.” Both were also common names for Catalan Christians. None of the friends or witnesses in the widow Regina’s will, just three folios back, appear in this group of relatives and friends.

The Catalan notary experienced a moment of confusion with the biblical Rubèn, writing first Rotben (on the analogy of names like Rotland for Roland) but canceling it. Other names offer some difficulty. Bedós and Badós are general Catalan surnames. The wife Cubes/Cobes may relate to the Catalan name Cubí or the Sephardic family Cuby (from Qubbia in Morocco); it is less likely to be a form in diminutive of (Ja)cob. The daughter Baynola recalls Catalan toponyms from late Latin balneola for bath (Banyols, Banyoles, Banyolí); as with Cubes, however, these suggestions are merely conjectural. Bonatosa seems an uncommon name, perhaps an augmentative for Bonat; paleographically it is not the more acceptable Bona cosa. The male name Vidas among Catalan Jews and Christians was more usually in the singular Vida.[8] Elias is a form of biblical Eliyahu, English Elijah. A family tree shows:

| • | • | • |

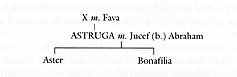

Astruga, Wife of Jucef Abraham

The next will in sequence comes on the verso of Salamó’s and is dated November 6.[9] Fallen ill, Astruga “with the consent of my husband” Jucef Abraham, a Jew of Puigcerdá, disposes “of my goods.” In first place, she gives her mother Fava[10] 600 Barcelonan sous to cover any “share, legitimate inheritance, and claim belonging to her.” Astruga’s husband can keep this money, however, if he remains unmarried and supports Fava in his home. “I wish and order that, if the said Jucef Abraham my husband shall wish to provide for my mother in his house in all her material needs for all her life, my mother cannot force my husband to pay her the aforesaid moneys, as long as my husband does not take another wife and wishes to remain chaste; if my husband shall take another wife, however, I wish that my mother can immediately compel my husband to pay her the aforesaid moneys.” Such conditional provision of funds for spouses who remained unmarried were common enough in male testaments; the novelty here is that the wife sets up the condition and that the money will be only a usufruct that really belongs to his mother-in-law in permanent residence.

That weighty matter extensively clarified, Astruga next presents “to the crown of the scroll of the synagogue [scola] of the Jews of Puigcerdá” 50 Barcelonan sous. The “crown” (‘aṭara) was one form of decoration covering the ends of the rods or staves on which the Torah scroll turned; such decorations were usually gilded or otherwise embellished. The handsome sum here probably covered the cost only partially, since the legacy is “to” the crown.[11] Only now does Astruga take up legacies proper, and these she confines to her children. She has two daughters by Jucef: Aster and Bonafilla or Bonafília. (Both forms appear in the will, corresponding to the two Catalan forms of the feminine of Bonfill.) Astruga leaves these daughters “all my clothing and household furnishings”; clothing was a valuable legacy in medieval wills because of its high market value and because it was passed on from generation to generation.

Astruga then names as universal heirs “in all my remaining goods” the two daughters. Her husband’s approval was obviously important. He signs first: “I Jucef, her husband, approve.” The “invited witnesses” have more than the usual share of Christians, including a cleric: Pere Salmes, Guillem Comdor, Bernat Colomer, Jaume Orig, Simó de Pinosa the rector of the church of Castellar, Bondia Abraham, and Jucef Cohen. The Christians, reasonably enough, all seem to be local people. Orig is simply an antique variant for the toponym Urg (now Urtx). Castellar of the rector is southwest of Seo de Urgel, near Tost. Salmes may relate to the Catalan family name Salma.[12] The immediate family revealed here is minimal:

A notation at the bottom says “Let the husband give 5 sous.” Cancellation by three horizontal lines indicates that this sum paid for a copy. Aside from the bequest to the synagogue, the will basically puts everything at the wife’s disposition into her daughters’ hands. The only other proviso, taking up half the will, ensures that Jucef will take care of his mother-in-law within his household. The sum set aside, 600 sous, must have been adequate as a permanent fund to support an old woman until death. As was customary, Astruga had probably taken care of religious and charitable benefactions and of friends or relatives by timely final gifts. The whole tone of the will suggests a woman of some independent means; she does not appear in Delcor’s summaries of moneylenders, but a wife’s activities could be masked by her husband’s name.

| • | • | • |

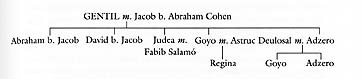

Gentil, Wife of Jacob Abraham Cohen

The fourth will in this Puigcerdá series comes two folios later, dated 21 November 1306, and is again by a woman.[13] “Gentil, wife of the Jew Jacob Abraham Choen” or Cohen, in her illness establishes her husband as her “administrator and executor.” Her first arrangement is that Jacob and her universal heirs are to distribute 100 Barcelona sous in charity “for my soul,” thoughtfully inserting above the line the ample time frame “within one year.” To her daughter Judea, “wife of Fabib Salamó of Barcelona,” she leaves a mere 5 sous; with the dowry given at the time of marriage, this is to be Judea’s entire inheritance. To her granddaughter (“Regina, daughter of my deceased daughter Goyo”), both in her own right and by “reason of her mother,” Gentil leaves another 5 sous; the dowry given at the time of Goyo’s marriage to Astruc Deulosal, as stated in the matrimonial documents more fully, is added here. Apparently Deulosal had also married Regina’s other daughter Adzero, who had then also died, leaving two daughters Goyo and Adzero. To these granddaughters, for themselves and by reason of their mother’s claim, Gentil gives 5 Barcelona sous apiece plus the dowry as described in Adzero’s nuptial agreements.

Finally, Gentil established her sons Abraham b. Jacob Cohen and David b. Jacob Cohen as universal heirs; should one of them die without legitimate offspring, the other if living would receive that share too. The “invited witnesses” include the Christians Bernat Pere, Mateu d’En Bord, Joan Bailó, Bernat Collat, Guido de Paretes [Piritis], and Arnau Ponç, and the Jews Duran Salamó and Salamó Jucef. The last witness, Salamó Jucef, may be the same man as in the witness list of the Bedós will, but the names and combination are too common to afford certainty. This will has eight instead of the usual seven witnesses, which was permitted. The only candidates for merging two names into one (Joan the bailiff of Bernat Collat) is disqualified by the genitive of the surname Bailó. Gentil’s will seems oriented toward retaining the family’s resources within the immediate male line. The apparent harshness with which others are treated and the absence of friends and most charities is again surely an illusion. The basic purpose of the will had little to do with pretestamentary dispositions, which had probably taken care of those other concerns. Even the 100 sous for funerary charities reminds us that this would have been a small part of the funeral celebrations, which reflected and maintained social status. The will displays the whole family, which relates to that of Jacob Abraham Cohen, given above:

The family followed both patronym and surname or title. The father Jacob Abraham (Latin genitive for surname or as ben Abraham) Cohen had as sons Abraham Jacob Cohen and Davit (Catalan David) Jacob Cohen. Gentil in the manuscript follows the now-antiquated Gentill spelling of the Catalan name for “cherished,” “gracious,” “highborn” (and even “gentile”!). Similarly the Latin Judea reflects the medieval Catalan Judeua (modern Jueva, Hebrew Yehuda feminized). Fabib may be Arabic Ḥabīb or else Hebrew Habib (“beloved”). Catalan Astruc here keeps the antiquated final h. The feminine name Goig appears several times in the crown registers; like Joya it is Catalan for “joy”. The name Goyo seems a variant either of Goig or of Provençal Goiona. Adzero/Atzero may approximate Hebrew Asher for “blessed”. Catalan Duran, a name echoing “endurance,” doubtless also had a Hebrew cognate.[14]

| • | • | • |

These four early wills, all confected in the same year, 1306, indeed within the same two months, reflect independent family groupings. The Jewish community was very small by our contemporary standards. All of Puigcerdá itself held only 660 Christian or other households in 1359, constituting two-thirds of the Cerdanya region’s population. This count came in the wake of the ravages of the Black Death and must be adjusted for that context. Still, three wills from the year 1306 offer a ground-level glimpse of family life that must have been a cross section of the small Jewish community (the aljama), or of those prosperous enough to make wills. No element within this series of wills as a whole explains why these families, and only these, entered testaments in the Christian notary’s book of wills. These were probably not all the deaths in the Jewish community that year; in any case, other codices reserved for testaments at Puigcerdá in other years in the full notarial library do not show the same high percentage of Jewish wills. Nor are the wills homogeneous. Each differs from the other, revealing a unique family problem or situation.

In some respects, of course, these wills echo one another. Each testator is ill; all are concerned to preserve family resources relatively undivided; three of the four have pro anima legacies (though presumably all had previously arranged philanthropies); all show strong family feeling; all have some, even many, Christians to bolster the witness lists; all repeat the identification “Jew” for the parties involved, as a legal incantation, though we might not think it necessary for identification. More significant perhaps, three of the four testaments are by women, each in a somewhat different family situation. Regina is a widow who remembers friends, Astruga acts with her husband’s consent and has him sign his specific approval, and Gentil acts independently but makes her husband her executor. Even the single male testator establishes his wife Cobes as executor of his will and guardian of his children and property for her lifetime.

Were wills, or wills before Christian notaries, more useful for Jewish women than for men? Were the properties at their disposition, whether as wives or widows, less secure? There is no reason to think so; wills by women had always been usual enough even in Geniza days; and other wills (three of the five from Puigcerdá that we are about to examine briefly) were by men. The balance in the present series simply mirrors the independence and initiative of Mediterranean Jewish women in their domestic sphere. Finally, since there are numerous nontestamentary bits of documentation for Jews scattered unpublished through the Puigcerdá notarial archives, these several family trees and witness lists make a beginning toward reconstruction of that familial community for men and women of all ages.

| • | • | • |

Reina: Widow in Valls

Far to the south of Pyrenean Puigcerdá and thirty years into the future, a final exemplar can round off this set of women’s wills. The testament comes in 1338 from the town of Valls, twenty kilometers inland from Tarragona and a satellite of that grand Catalan city. A bovage tax at the very time of this testament counted 712 households in the town, a figure reduced in the post–Black Death census of 1358 to 587 households and in the census of 1370 to 569. If the Jewish community there held some 30 families at the time of its destruction in the general massacres of 1391, it seems reasonable to enlarge it for the time of the testament to some 45 households. The center of its own district, with a role in the regional network or commune as well, the town boasted its own governance under two consuls plus a division of overlordship by king and archbishop of Tarragona, with a lively commercial, agricultural, and artisanal (especially textile) activity.

Gabriel Secall i Güell has drawn on the surviving local notarial manuals as well as other archival and published materials to re-create the Jewish community in Valls. Four libri Iudeorum remain today, for the years 1313–1315, 1313–1324, 1328, and 1342–1344, respectively. The first of these deals with 37 males, including some with their wives; the second has 53 clients. Secall takes these to be families and understands the discrepancy in numbers to indicate the general demographic rise in Catalonia during that decade. A coefficient of three or four persons per family would put between 159 and 212 Jews in Valls around the year 1324.[15]

Secall has found a fascinating testament in this material, drawn in 1338 by Regina or Reina, the widow of Bonjua Cap. Both appear alive and active in the Liber Iudeorum of 1323–1324. The Cap family were widely distributed in Catalan lands, an affluent merchant clan; in Valls they were especially involved in marketing cloth. Leila Berner has chronicled their high status and economic activities in thirteenth-century Barcelona. Secall transcribes Reina’s will in a footnote, sums its dispositions in his text, and supplies a photograph of one of its folios.[16] A canceling X down the page indicates that a formal parchment copy had been issued. Reina begins by noting her illness as well as her sound “sense, memory, and legal wholeness.” She “revokes all my other testaments and last wills drafted or made by me formerly and which I wish to be without validity,” a clause suggesting that her children had since died or perhaps that her husband Bonjua had figured in previous dispositions. Without children or husband now, she distributes 2,720 sous to relatives, friends, and charities.

In first place come 500 sous that her executors “are to distribute for marrying off Jewish girls,” namely, for dowries. The executors are to invest another 500 sous at interest until the money suffices to buy a Torah for the synagogue. The manuscript has deteriorated in this part, but the verb lucror suggests putting the money out at loan, while one fragment seems to indicate doubling the money by that expedient. The result of this financial business, however, is clear: “a Sefer Torah, which Scroll or Sefer Torah [rotlle sive çafertora] I wish to give and assign to the school or synagogue of the Jews of the place of Valls.” As the five books of Moses used in worship, the Torah was at the center of synagogue life and the most sacred object held by the community. The very large price, something over 500 sous and probably a thousand, was a result not only of the scribal artistry required for any book meant for reading but here especially a product of materials of the highest quality, the services of a sōfer skilled in the strict rules guiding every aspect of the sacred task, and the careful reverence that precluded the easy rapidity of a secular bookmaker.

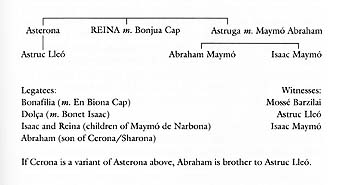

The other large legacy, 1000 sous, goes to Bonafília, “the wife of En Biona Cap a Jew of Falset,” a hill town south of Valls and Tarragona. The mildly honorific En and the husband’s surname are our only clues to this in-law whose legacy was larger than those of all other relatives and friends together except for the universal heir. Reina leaves 300 sous to her nephew Astruc Lleó, the son of her sister Asterona (no husband designated). Another 200 sous go to Dolça (“Dulcich,” perhaps a form of the related name Dolcenc), the wife of Bonet Isaac. Another 200 go to Abraham “son of the said Cerona.” Though Cerona was not previously “said” in the will, its feminine modifier suggests that it is the Hebrew biblical Sharon in its variant Sharona. In the will “Cerona” appears twice and “Asterona” once, raising a suspicion of miscopy of the same name. Assuming they are different, one might follow Seror’s name lists, which put both “Esterona” and “Serrona” as variants of Aster/Est(h)er. Though a strong element of conjecture is involved, the Hebrew option Sharona seems more plausible.

The final general legacies are 10 sous apiece to Isaac and Reina, the children of Maymó de Narbona (of Narbonne, but a resident now of Valls). This family may be relatives, since the will insists that the token sum represents “their claim that they have or can have in or on my goods.” The executors charged with disbursing all this are the children of her sister Astruga, Isaac Maymó and Abraham Maymó, though “through” the universal heir, Astruga herself. As for nonmonetary legacies, Reina gives to the Sharona just mentioned “a third part of all my cloth, both woolen and linen, both fustian and tow, and also any other kind of cloth” as well as a third part “of my pots and bowls of copper.” Astruga is to keep everything else “in the residence [hospicium] in which I and she and her [two] children live together.” Astruga as heir and the executors are to dismiss all debts by “all poor Jews who are obligated and owe me debts going up to the sum of fifteen sous” in Barcelona silver money (terna, Catalan moneda de tern of 1258). And Astruga is to restore to these “poor” Jewish debtors the pledges they had given. The witnesses to the will are three Jews: Mossé Barzilai (“Barzelay”), Astruc Lleó, and Isaac (“Isçach”) Maymó (Astruc Lleó was her nephew by Asterona and Isaac her nephew by Astruga).[17]

The family tree, though lacking direct heirs from Reina, exhibits a contemporary extended family, in which Maymó de Narbona should be considered a relative.

Family names merit a glance. The Cap surname was Catalan for Hebrew Rosh as head or chief. Lleó as Latin Leo translates Hebrew Judah/ Yehudah. Astera echoes Catalan and biblical Ester, “star.” Barzelay is Aramaic and biblical Barzilai, “man of iron” (cf. Catalan Ferrer). Bonjua is a Catalan variant of Bonjueu and Bonjudá.[18]

| • | • | • |

Wills and Women

The women’s wills done at Puigcerdá within a period of two months invited reflection as a single group phenomenon. Taking all the women’s wills at once, each invaluable for its data and implications, some generalities may now be essayed. A preliminary caution should note that a husband’s Latinate will was far more important to the average Jewish wife than was the exercise of power or control involved in a widow’s or a dying wife’s own testament. The complexities of Jewish law might leave the husband’s assets in the widow’s hands, as was seen above, but the man’s heirs and creditors might then move in and throw the whole question into court. A Latinate or notarial will would authoritatively forestall challenge.

The women in our own wills here, notably the widows, belong to relatively affluent strata of their respective communities. Most of them are clearly individuals, not shadows obscured by a notary’s formulas. One widow makes God her universal heir, another directs a large sum to be invested in order to commission a Torah for the synagogue, a third extensively and effectively blocks her widower-husband from remarrying. Most arrange for public charities, from children’s education to Torah crown to bedclothes for the synagogue. Judith Baskin has suggested that such religious legacies by women represented “female strategies for imprinting their existences on a communal religious life from which they were otherwise barred.”[19] But the legacies may also simply extend the primary role of women as keepers of the faith in their domestic sphere.

These wills are not notarial clones, as with so many contemporary Christian wills. They range from a simple family affair (husband as executor, sons as universal heirs, glancing reference to three daughters) to a very complicated remembrance involving eighteen legatees. Each will has at least seven formal witnesses (eight in some cases), but their composition varies from four Jews with four Christians, to seven Christians alone, to two Jews and five Christians, to two Jews and six Christians. The Valls will has three Jews at the beginning of an otherwise illegible line. The artisan character of many of the Christian witnesses in both women’s and men’s wills may simply indicate the kind of persons with whom the Jews routinely dealt, or this may be the notary’s doing. The identity of the Jewish witnesses may become clearer by computer analysis of all the Jewish names in the loan records and other documents at a given place. Witnesses, Jewish or Christian, do not seem to be professionals regularly renting their services.

Women’s wills have a strong philanthropic element, at times startlingly generous. And they include other women, relatives or friends, more usually than do the men’s wills. The women’s wills, perhaps more than the men’s, afford glimpses into domestic arrangements. One dying woman makes it clear that she has her husband’s consent for the complex dispositions she lists. Since women and women’s affairs appear by indirection in the men’s wills and since lawsuits and other auxiliary documentation sometimes place women in central roles, the impressions given by women’s testaments might be expanded and sharpened by the industrious addition of such fragments. A larger task ahead is to correlate the activities of the women in the wills with the talmudic regulations regarding widows and their husbands’ properties and with Jewish tradition and experience generally with inheritances.

Shlomo Goitein has led the way here with regard to Geniza materials on inheritance in an earlier period (ca. 950–1200).[20] He notes how the death of a wife was at worst a difficult situation for the husband, while the death of a husband was a disaster for many wives. Left with only the remnants of the dowry, personal belongings, the delayed marriage gift, and not much else, the widows in the poorer classes were often thrown on public support. Goitein also notes that it was rare for a Geniza husband to make his widow sole heir, since remarriage would shift his property to the new husband. The husband not infrequently made his widow executor, however, showing confidence in her good sense and financial shrewdness; and of course he might declare his widow the guardian of his minor children.

Some elements common in the Geniza inheritance procedures have no echo in the Latinate wills, though they may well have occurred in the widow’s Jewish community—for example, the disliked “women’s oath” that she held nothing of the dead husband’s own property (very strictly interpreted sometimes), or the principle that “heirs have precedence [over widows].” Other elements of traditional inheritance patterns may hide beneath the notarial patterns of expression, such as the husband’s statement on his deathbed as to how much he still owed his wife, or the use of an inheritance disposition to cover as much as possible the final debt owed to the wife. If the Geniza fragments have proved so illuminating in such inheritance matters for their own period, the Latinate Jewish wills, as their numbers increase, may be persuaded to reveal as much or more for this later time. The rich responsa literature, in which distinguished experts “responded” to dilemmas of law and life, will illumine the many background details. This source is complicated, however, by the frequent lack of place and time and by the exemplary nature of the genre.

Whatever the prescriptions of custom and Talmud, each community of Jews lived within and interacted with one or another local Christian culture. How the Catalan culture, its perceptions and expression, modified or reexpressed Roman law testamentary experience may have had a strong effect on these Jewish wills and on contemporaries’ understanding of them. The current researches of Stephen Bensch on the testamentary data and trends of thirteenth-century Catalan Christians are helpful here. Bensch finds that Christian women made one out of three wills in thirteenth-century Barcelona (up from one in five for the twelfth century); half of these women were wives, not widows. He notes that after 1250 husbands as executors and wives as estate managers become less common in these wills. The wills in general followed the Roman law strategy of a universal heir rather than the previously dominant Visigothic model of equal shares. Demographically, the Christians reveal one or no children in 67 percent of the testaments, which may reflect the advanced age of most testators, whose children were already established elsewhere in this affluent stratum. Bensch also explores the dowry brought by the wife and the dower or promise of a later gift by the husband (sponsalicium). The dower, he concludes, had become in fact “a broad grant of rights over all her husband’s property”; one consequence was that the wife’s name was needed for any property transfer by a husband. A larger result was that the Christian woman in Barcelona had become “a formidable figure with broad discretionary powers over property received from her husband’s kin.”[21]

Analogous patterns seem to have operated in the Jewish community, where many husbands had promised a delayed marriage gift they could not pay before their death. Such intersections or reinforcements of a Jewish subculture by the host Christian subculture suggest that widowhood and other factors in Jewish women’s wills ought to be approached also by reading such wills against the background of law codes of the Catalan peoples, such as the Furs of Valencia. Conversely, investigation of some Jewish influence on Christian women’s wills, especially in small communities with enough intimacy between Christians and Jews to disconcert the ecclesiastical authorities, also may prove rewarding. Renée Melammed cites a significant case of crossover influence in fourteenth-century Toledo, where the Jews had begun to imitate the Christian division of half the deceased husband’s property to the widow, resulting in a debate between the Jewish community’s authorities and Asher b. Yehiel, the incumbent of the prestigious Toledo rabbinate.[22]

The role of wives and widows in making testaments and in administering a husband’s estate and acting as guardian of children must have resonated differently in the two societies. The use of Roman notarial concepts to supplement the elements of a Jewish will by a Latin will raises intriguing questions about cultural diffusion. Where the activities or rights of women were more or less equivalent in each society, did the Latinate will reinforce the analogous Jewish structure? Where they diverged, did the Latinate will tend to modify Jewish custom? Was the role of the dowry in Jewish society modified, either in attitude or concept, because of the dowry’s changing meaning and effects in Latin wills? Women were very strong figures on the Catalan Christian testamentary scene, a context that needs to be related to the parallel Jewish scene.

Notes

1. Cheryl Tallen, “Opportunities for Medieval Northern European Jewish Widows in the Public and Domestic Spheres,” in Upon My Husband’s Death: Widows in the Literature and Histories of Medieval Europe, ed. Louise Mirrer (Ann Arbor, 1992), 116. Renée Levine Melammed, “Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods,” in Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, ed. Judith R. Baskin (Detroit, 1991), 122–123. She also notes that to avoid the prohibition against wives inheriting “it was not uncommon for husbands in many periods of Jewish history to have recourse to non-Jewish systems in order to leave a greater part of their estates to their wives” (p. 132n.). In the same volume see Judith Baskin, “Jewish Women in the Middle Ages,” 94–114. On the rights and limitations of Jewish women “donors” or testators see Reuven Yaron, Gifts in Contemplation of Death in Jewish and Roman Law (Oxford, 1960), 138–140, and for the role of women as heirs/donees pp. 153–161; see also pp. 174–176 (widows) and 217–220 (dwelling rights). See too Enrique Cantera Montenegro, “Actividades socio-profesionales de la mujer judía en los reinos hispanocristianos de la baja edad media,” in El trabajo de las mujeres en la edad media hispana, ed. Angela Muñoz Fernánez and Cristina Segura Graiño (Madrid, 1988), 321–345; and ibid. for background Carme Batlle, “Noticias sobre la mujer catalana en el mundo de los negocios (siglo XIII),” 201–221. For wills of Jewish women in Aragon, see above, chap. 1, nn. 23–25. See also B. Z. Scherschewsky et al., “Widow,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 16, pp. 487–495, also published in The Principles of Jewish Law, ed. Menachem Elon (Jerusalem, 1975), cols. 399–403. The only study of widows in the area of the present book is Richard W. Emery, “Les veuves juifs de Perpignan,” Provence historique 37 (1987): 559–569, a sociological analysis from some 850 notarial codices of Perpignan and other towns of Roussillon over a broad time range. He can document 285 widows, 555 married women, and 1,400 male Jews, but only 24 widowers. He estimates the Jewish population as fluctuating between 150 to 200 families, with widows numbering between 30 and 50, and he addresses such questions as marriage age and remarriage.

2. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, protocols, Mateu d’Alb and Bernat Mauri, Liber testamentorum 1306–1307, fol. 12v (23 October 1306), transcribed below in appendix, doc. 35. Canceled by three vertical lines, indicating a copy made. Initial X signals the start of a new document. In the left margin center: “debet V solidos.” Cf. Richard W. Emery, The Jews of Perpignan in the Thirteenth Century: An Economic Study Based on Notarial Records (New York, 1959), name list on pp. 200–202 for comparisons.

3. Antonio Pons, Los judíos del reino de Mallorca durante los siglos XIII y XIV, 2 vols. (Palma de Mallorca, [1958–1960] 1984), vol. 2, p. 271, doc. 88 (8 August 1331), also in Fidel Fita and Gabriel Llabrés, “Privilegios de los hebreos mallorquines en el codice Pueyo,” Boletín de la Real academia de la historia 36 (1900): 200–203, doc. 47: “iudei scolam habere valeant vel domum aliquam sive propriam sive conductitiam ad orandum iuxta legem Mosaycam ritus et consuetudines iudeorum in civitate predicta, ubi sinagogam curiosam et valde formosam et domum ad orandum alias habuerunt.” The present scola is “potius antique reparatio et refectio, quam non sinagogam sed scolam aut domum ad orandum permittimus noncupari.” Josep Millás Vallicrosa, “Esbozo histórico sobre los judíos en Barcelona,” Miscellanea barcinonensia 12 (1966): 13–20.

4. Arch. Crown, reg. 202, fol. 202 (27 December 1304): “eo quia graviter excessistis, quia sinagogam vestram et almidraz construxistis et operati fuistis alcius et amplius quam fuisset licitus et debebat[ur]; quam quidem sinagogam et almidraz nos per vos ad statum debitum et pristinum reduci fecimus et mandavimus.” On the circumstances of this synagogue see David Abulafia, “From Privilege to Persecution: Crown, Church, and Synagogue in the City of Majorca, 1229–1343,” in Church and City 1000–1500: Essays in Honor of Christopher Brooke, ed. David Abulafia et al. (Cambridge, 1992), 124–125, and his Mediterranean Emporium, 90.

5. The manuscript gives the name forms as Abraham (in second declension), Aster, Astruch, Bondia, Bonet, Choen, Coras (?), Crexent, Fagim, Gaux, Jacob, Juceff, Mancosa, Mometa, Regina, Soall, Vitalis. On Aster as Est(h)er see above, chap. 4, p. 86. On Bondia see chap. 3, n. 47, on Bonet n. 27, on Cohen n. 30; on Creixent chap. 4, p. 82, on Fagim/Faqim p. 80, and on Gaugs/Gaux p. 98. Though Mancosa baffles Simon Seror (Les Noms des juifs de France au moyen âge [Paris, 1989], 171) it may well come from Catalan mancús, a facsimile or counterfeit Arabic gold coin minted at Barcelona by the counts; the first emission carried the minter’s name “Bonnom hebreu,” while the second was minted by the Jew Enees. The value, beauty, Jewish connection, and by the thirteenth century rarity of the exotic Arabic-Catalan coin must have led to this rare use of it as a name. Mometa is feminine for the masculine Momet/Mamet used among Jews at this time. Plausible origins are hard to discover, and Seror’s Noms des juifs is not useful here. The Catalan and ancient Roman name Mamet/Mamert (including an Occitan St. Mamet) may afford a clue. The rest of the names here were touched on in my introduction, except for the puzzle of Coras/Comte/Cresques.

6. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, protocols, Alb/Mauri, fol. 15 (9 November 1306), transcribed below in appendix, doc. 37. Uncanceled. Mazères is seventy kilometers west of Toulouse, though less likely candidates can also be suggested.

7. Fori antiqui Valentiae, ed. Manuel Dualde Serrano (Madrid, 1967), rub. 82.

8. Cf. the Bedós will in chap. 4, n. 22, and related text. The manuscript gives the name forms throughout the document as Astruch, Baynola, Bedoz, Bonatosa, Cobes and Cubes, Deuslosal, Elias, Jacob, Juceff, Mosse, Ruben, Salamo, and Vidas, with toponym forms Besaldu, Lunellus, and Matzeres. Deulosal might also be seen as salutation, as Shalom. The phrase “domina et potens” in this will to mean full executor and administrator first appears in Catalan texts in 1192, though the reality of widows as executors was “much older”; see Stephen Bensch, Barcelona and Its Rulers 1096–1291 (Cambridge, 1995), 273, with citations of testaments also from 1250.

9. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, protocols, Alb/Mauri, fol. 15v (6 November 1306), transcribed below in appendix, doc. 36. Canceled by three vertical lines, indicating copy made. At left margin middle, again: “debet V solidos.” In paragraph three, adverbial caste used. Before Jucef (always Juceff in the manuscript) in the witness area: X.

10. Is Fava a form of Catalan Febe (English Phoebe; of Greek root)? Seror finds the name among Jews at Narbonne, Marseilles, and Perpignan, and also as a Christian name; he suggests an origin in French fève, as in trouver la fève au gáteau (to hit the mark, have a lucky find); see his Noms des juifs, 105. More simply, the Catalan surname Fava (“bean”) may be its affectionate and whimsical source.

11. Shlomo D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 6 vols. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1967–1993), 2:151. Alvin Kass, “Torah, Ornaments,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 15, cols. 1255–1258, and plates. The Sephardim used a wooden scroll-case, opening like a book, the rods coming up through its top.

12. The manuscript gives the various name forms as Abraham (in first declension), Aster, Astruga, Bonafylla and Bonafilia, Bondia, Coen, Fava, and Juceff. On Aster/Est(h)er see p. 86. For Bondia see chap. 3, n. 47, for Cohen n. 30.

13. Arch. Hist. Puigcerdá, protocols, Alb/Mauri, fol. 17rv (21 November 1306), transcribed below in appendix, doc. 38.

14. The manuscript gives the various name forms as Abraham (first declension), Adzero/Atzero, Astruch, Choen, Davit, Deulosal, Durandus, Fabib, Gentill, Goyo, Jacob, Juceff, Judea, Regina, and Salamon. On the name Asher see chap. 4, pp. 78, 83.

15. Gabriel Secall i Güell, Els jueus de Valls i la seva época (Valls, 1980), from the Arxiu Històric Arxidiocesà de Tarragona, with the four libri Judeorum described at length on p. 200. On the number of families and complete lists, see pp. 193, 204–206. The author reprinted this will in his Les jueries medievals tarragonines (Valls, 1983), appendix, pp. 554–555, doc. 19.

16. Ibid., pp. 188–191, with transcription on pp. 202–203 (1337–1338). Leila Berner, “A Mediterranean Community: Barcelona’s Jews under James the Conqueror,” Ph. D. diss., UCLA, 1986, pp. 144–162, 452–455.

17. Some of the phrases are “revocans omnia alia mea testamenta et ultimas voluntates per me olim conditas sive factas quondam”; “quod quingenti solidi distribuantur per eos ad puellas judeas maritandas”; “çafertora, quod quidem rotle sive çafertora volo dari et assignari scole sive sinagogue judeorum”; “item dimitto dicte Cerone terciam partem omnium pannorum meorum, tam lane quam lini quam stupe quam fustani quam eciam aliorum…et eciam ollarum mearum et mortariorum de cupro”; “absolvo et libero omnes judeos pauperes, qui mihi…debeant debita ascendencia usque ad quantitatem quindecim solidos terni”; “in hospicio quod ego et ipsa et eius filii insimul habitamus”. (I have corrected some grammatical or typographical errors.) Seror, Noms des juifs, 100, on Serrona. On the de tern money here, see my introduction, above, under “Moneys.”

18. The manuscript as transcribed presents the names in the will as Abraam, Asterona, Astrugua, Barzelay, Biona, Bonafilia, Bonetus, Boniua, Cap, Cerona, Dulcich, Isach and Isçach, Leo, Maymo and Maymonus, Regina. On the name Biona see above, chap. 3, n. 26. On Maymó as Arabic Maimūn see above chap. 4, p. 77. Besides names discussed in the text, a number are in my introduction. The transcription errs as filius for filios in setting executors; name form and later reference to Astruga’s sons clarify this. Regino and Astero are maltranscriptions, perhaps for the diminutives Reginona and Asterona. Note that there are two Maymos, one being the dead husband, the other being the legatee Maymó de Narbonne.

19. Baskin, “Jewish Women in the Middle Ages,” 102.

20. Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 3:250–260, 278, 285–286.

21. Bensch, Barcelona and Its Rulers, chap. 6, especially the section “Marital Assigns and Widows’ Rights,” quotations from pp. 264 and 266.

22. Renée Melammed, “Sephardi Women,” 23. Yitzhak Baer discusses the case in his A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, 2 vols. (Philadelphia, 1971), 1:318–319.