5. Making Room versus Creating Space

The Construction of Spatial Categories by Itinerant Mouride Traders

Victoria Ebin

Studies on how people use space generally focus on groups identified with a particular setting. The Mourides, however, are itinerant traders who are nearly full-time travelers, constantly on the move in search of new goods and clients. These traders, who belong to a Sufi brotherhood based in Senegal, have neither the time nor the resources to transform their living quarters in any radical way.

This essay explores how, despite their transient lives, the Mourides use and appropriate space in ways that are specifically their own. If no one hears a tree fall in the forest, does it make a noise? If no Mourides are in the room, is the room, in any definable way, Mouride?

The Mouride brotherhood is a Sufi tariqa organized around a founding saint, Cheikh Amadu Bamba (ca. 1857–1927), a holy man who attracted a large following in the confused period following the French conquest of Senegal. Originally a rural brotherhood, the Mourides assumed a powerful role in national government by the late 1920s through their role in peanut farming. With the drop in peanut prices, drought, and the decreasing fertility of the soil, large numbers of Mourides have migrated to the cities over the past two decades. They have now become a trading diaspora, with trade networks stretching from Dakar to western Europe and on to Jidda and Hong Kong. In their long boubous, with red-and-blue-striped plastic bags, they are familiar figures in the wholesale districts of major capital cities in Europe and North America, and have been sighted in Istanbul (Le Soleil, August 22, 1992).

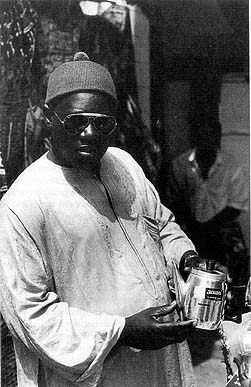

Despite their rural backgrounds and often barely functional French, they leave their homes in rural Senegal to make long intercontinental trips.[1] While they may occasionally pause for a few months, they are virtually nonstop travelers, with a beat that covers a good portion of the globe. As one Mouride put it, “Our homeland [in western Senegal] is built on sand, and, like the sand, we are blown everywhere.…Nowadays you can go to the ends of the earth and see a Mouride wearing a wool cap with a pom-pom selling something to someone” (fig. 18).

Figure 18. A Mouride wearing the characteristic hat with pom-pom, Dakar. Photograph by Victoria Ebin.

| • | • | • |

Mouride History

By the end of the nineteenth century, Senegal was almost completely Islamized. Islamic movements had been present in the region since the eleventh century, but at the end of the eighteenth century, the religion became more implanted when warriors from the north attempted to create Islamic states in Wolof kingdoms whose rulers were animist or only semi-Islamized (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 13). Battles between militant Muslims and animist chiefs continued for many years and virtually destroyed the social organization of Wolof society. By the mid nineteenth century, the region was divided by internal strife.

The Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya, Islamic brotherhoods that have their origins in North Africa and the Middle East, appeared in Senegal during the time of upheaval and division in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 27). Based on the veneration of Islamic saints, who were regarded as carriers of baraka, or grace, they were a powerful unifying force and became centers of resistance against the animist aristocrats and the French colonizers, offering a haven to those who wanted to flee the French administration or the local chiefs (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 26).

The Mouride brotherhood alone had its origins in Senegal. Its appearance is associated with a series of crises—the disintegration of social and political structures after years of internal warfare, the French conquest, and the introduction of cash-crop agriculture (Copans 1972: 19–33, cited in Diop 1984: 46). Cheikh Amadu Bamba was from a learned Muslim family that had links with both the Tijaniyya and Qadiriyya. Initially, he drew followers from many levels of society, mostly artisans, traders, and slaves, who more than other members of the community had something to gain from the Mouride doctrine of hard work as the way to salvation. He also won over local rulers, for whom Mouridism represented a nonmilitary form of resistance to colonial rule (Diop 1984: 45).

The French initially viewed Amadu Bamba as a threat to their fragile authority, repeatedly sending him into exile, first to Gabon, then to southern Mauritania, and then to a remote region of Senegal. During his many years of solitude, he wrote voluminously and created a substantial body of religious writing, now housed in Touba, the Mouride center. He addressed the murid, or seeker after God, and the term gave the movement its name, Muridiyya. Exile confirmed Amadu Bamba’s status as a saint. Upon each return, he was greeted by increasing numbers of admirers and followers.[2]

Toward 1912, Mouride relations with the French improved, and Mourides became actively involved with French agricultural projects. Mouride leaders organized their followers into efficient work groups, which cleared and cultivated land for peanut production (with sometimes disastrous results for the Fulani pastoralists).

More than any of the other brotherhoods, the Mourides became an economic community, united by an ethic of hard work and an internal organization that eventually made them the country’s top peanut producers.The Mourides had certain qualities that fostered this role. First, Mouride doctrine emphasized work, discipline, and prayer, and valued physical labor. Indeed, Cheikh Ibra Fall, Amadu Bamba’s foremost disciple, or taalibe, preached that fervent dedication to work replaced the obligations to pray and fast. Second, the leaders of the brotherhood displayed unusual organizational abilities in creating a highly disciplined work force among their taalibes. Finally, the cheikhs were highly skilled in mediating between the peasants and the French authorities (Fatton 1987: 98–99). As producers of one-quarter of the country’s total crop, Mourides acquired political power in the administration that has continued until today (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 2).

One feature of the cheikhs’ organizational genius was the work group, which Donal Cruise O’Brien has described as “probably the single institution which has most contributed to the brotherhood’s success” (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 163). These groups also provided some education for the taalibes. Only after ten years of labor did taalibes receive their own land to farm, and even then they continued to work one day a week, generally Wednesday, for the cheikh. Today, when more Mourides are working in Dakar’s markets than in the fields, a delegation goes from store to store collecting money for the cheikhs every Wednesday.

Under Mamadou Mustapha, Amadu Bamba’s son, who succeeded him as khalifa-general, the Mourides became increasingly bureaucratized. Amadu Bamba’s saintly qualities and “charismatic authority” gave way to hierarchy as kinsmen and associates, and their descendants in turn, assumed positions of authority (Robinson 1987: 2). The current and fifth khalifa-general is Serigne Salyiou, another of Amadu Bamba’s sons.

With the transition to urban life and the migration of many Mourides abroad, the brotherhood has maintained its close ties by emphasizing the relationship between the cheikh and the taalibe. For a migrant, who may spend many years outside Senegal, the Mouride da’ira (Arabic pl. dawa’ir, circle, association) is crucial in maintaining contact with his cheikh and with Touba.

Each da’ira is founded to honor a particular cheikh, whose taalibes meet regularly in hotel rooms and apartments across western Europe and North America. They meet regularly to sing the qasa’ids, poems written in Arabic by Cheikh Amadu Bamba, and to share a meal (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 251).

Each da’ira elects officeholders, who keep in close touch with the cheikhs in Senegal. They collect money at each meeting to send back to the cheikh or, more typically, to the khalifa-general in memory of Serigne Touba (Cheikh Amadu Bamba). Important cheikhs, the khalifas of various lineages, have many da’iras scattered throughout other African countries, in Europe, and in America, which they generally visit once a year.

One of the most important da’iras in France, for example, is that of Serigne Mbacke Sokhna Lo, a great-grandson of Cheikh Amadu Bamba and son of Cheikh Mbacke, a major figure in the brotherhood. His appointed representative, who is in Lyons, is responsible for organizing the local da’ira and also makes regular visits to the cheikh’s other da’iras in Europe.

Da’iras are also organized by occupation and by neighborhood. Sandaga market in Dakar has several da’iras that meet regularly on the roof of the market while tailors, gold workers, and factory workers in some towns have created their own da’iras.

Da’iras were initially for Mourides who had left the countryside for towns in Senegal, but today, with the large numbers of Mourides whose involvement in trade leads them to travel nonstop, they have acquired a new importance as a meeting place for Mourides on the road.

| • | • | • |

The Mouride Economy Today

Mourides are now involved in trade at all levels, from selling on the streets to organizing a flourishing international electronics trade. The majority of Mourides, however, are street peddlers, bana-bana or modou-modou (a nickname for Mamadou in the Baol region of Senegal, whose people are believed to be particularly astute and hard-working, and where many of the street peddlers come from).

The Mouride street peddlers have been characterized as “inward-looking and conservative” in contrast to the Mouride students and ex-students now living in Europe and North America.[3] The students are active proselytizers and have made many converts among other migrant groups in France, while the peddlers prefer to live among themselves, limiting their contact with the outside world to work.

The bana-bana’s style is essentially the same wherever he goes. He deals in whatever he can sell, but for economic and practical reasons—quick turnover and small size—most specialize in Asian-made watches, “fantasy” jewelry, and novelty items such as fluorescent shoelaces and American cosmetics.

Being Mouride shapes a large part of their lives, whether they are urban migrants to Dakar or have settled abroad. A group of street peddlers from a village in the Baol region of Senegal live together in a room in Dakar—the same room that street-peddling migrants from their village have rented since the 1970s. Once a week they visit the local wholesalers, who are also Mouride, and pool their resources to buy large quantities of merchandise. Each peddler then takes a portion of the goods and sets out to sell it on his special “beat.” Bana-bana living in New York follow essentially the same routine. Every week, a household of migrants from Darou-Mousty in Senegal who now live in the Bronx set off for Chinatown to buy wholesale goods to resell.

Some bana-bana trade only seasonally. Mustapha and Moussa, for example, go to Marseilles every summer. They buy goods from their primary Mouride wholesaler and then set out for the small villages between Aix, Avignon, and Marseilles. Fellow Mourides have staked out the curve of Mediterranean beaches as their territory. At the end of the summer, most return to Senegal but some make their winter base in Lyons or Paris.

The circuit of one itinerant trader, Amadu Dieng, exemplifies Mouride entrepreneurial skills and adaptability. He set out from Senegal for Marseilles with two thousand “Ouagadougou” bracelets. In Marseilles, he stayed in a residential hotel with a cousin, whom he left some bracelets to sell, and also bought some Italian jewelry from a Mouride wholesaler. On to Paris, where he bought leather clothes made by Mouride tailors and items in the Turkish garment district to resell in New York. He sold everything in New York and bought up beauty products and music cassettes. Then on to Cameroon, where he sold the cassettes and sent the beauty products back to Senegal with a cousin. He then headed north to Libya to find work for a few months to make money to return to New York.

Other Mourides in Europe—students, tailors, or those with white-collar jobs—also rely on trade to supplement their incomes (“pour arrondir la fin du mois”). They too may become highly mobile at certain times of year as they take up trade, traveling across Europe or North America and relying on the brotherhood’s scattered communities for lodging and essential connections in the wholesale districts.

Mouride tailors who specialize in leather, for example, often become bana-bana in the summer, which is the off-season in the leather trade. One Mouride leather tailor in Paris works six months of the year in a Turkish-owned workshop and spends the rest of the year selling on the streets in Milan and Marseilles. Students too are integrated into the trade community by kinsmen and friends, who supply them with goods and teach them the strategies necessary to street peddling.

Unlike Amadu Dieng, who had obtained a multiple-entry visa for the United States, most bana-bana, once in New York, remain for some time, since they are not certain they can return. Mor Ndiaye, for example, sold sunglasses and umbrellas on a corner near Times Square for four years, returned to Senegal for a vacation, and was unable to get a visa to return. He now sells shoes from a kiosk in Dakar’s central market and plans how to get back to America.

Mouride businessmen who started their careers as bana-bana still travel extensively, buying and selling on a vaster scale. They buy television sets, VCRs, radios, cassettes, and compact-disc players in Jidda, Hong Kong, and New York, which they resell in Senegal. They also buy up smaller items such as African-American beauty products and television sets in New York. At least one Mouride trader who started out as a street peddler owes his fortune (several stores in Dakar and a factory making “hair extenders”) to the sale of such accessories—he was the first to sell Ultra-sheen products in Senegal.

| • | • | • |

Migration as a Theme in Mouride History

Mourides have been migrants since the early days of the brotherhood. In the past, cheikhs migrated with their taalibes to “pioneer lands” in the hinterlands in search of new farmland (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 60). Since their farming practices deplete the soil, Mourides were always in need of land, and even today Mourides continue to migrate within Senegal in search of new land.

The lives of New York street peddlers are also shaped by long years of travel. While other people from inhospitable regions migrate to establish themselves elsewhere, Mouride traders have continued, at least until now, to maintain their primary attachment to Senegal. A common saying is, “We are like the birds who think of home when flying high above the earth.”

Mourides find an explanation and some consolation for their transient lives in the brotherhood’s history. They say that travel leads to knowledge, xam-xam, which is essential to a young man’s education.[4] Travel and life in another country, and perhaps a foreign wife, add to one’s understanding of the world. The number of countries one has “done” (“faire la France [l’Italie, le Maroc, etc.]”) and the languages one speaks are frequent subjects of conversation at Mouride gatherings.

Travel has become an almost sacred activity for Mourides, and its special status can be seen in the large round house in Diourbel where Cheikh Amadu Bamba was confined by the French, where his suitcases have been preserved along with his books (fig. 19). By also becoming travelers, Mourides emphasize their ties with their founding saint.

Figure 19. Cheikh Amadu Bamba’s suitcases, Diourbel, Senegal. Photograph by Victoria Ebin.

Travel entails hardship, and one Mouride trader, a migrant for thirteen years, explained that Amadu Bamba wanted his followers to leave home to test their faith. Another underlined the theme: “We know misery so well that we have come to love it, so much that now we conjugate it as a verb, ‘Moi, je misère à New York; toi, tu misères à Paris.’ ”

| • | • | • |

The Mourides’ Spiritual and Spatial Center

Despite their highly mobile way of life and their many years abroad, Mourides’ point of orientation is Touba, the site of the mosque where Amadu Bamba is buried.[5] Touba (“finest or sweetest”) is the name given by Amadu Bamba to the village where he had a prophetic revelation and where the Mourides’ central mosque was later built. Its construction, authorized by the French in 1931, was undertaken by the first khalifa-general. The cost, not including the labor, has been estimated at equivalent to £1 million sterling, and it took thirty years build.[6]

The Touba mosque is said to be the largest in sub-Saharan Africa, with the central minaret almost three hundred feet high, four lesser minarets, fourteen domes, and two ablution baths (Nguyen Van-Chi-Bonnardel 1978: 869). Since its completion, the brotherhood has not built another major mosque. It has only one in Dakar, while other brotherhoods have built mosques throughout the city. In explanation, Mourides cite Amadu Bamba, who said that a true Mouride can pray anywhere as long as he is holy and “clean.”

The mosque at Touba is a point of reference for Mourides everywhere. Friday prayers led by the khalifa-general draw Mourides from all over Senegal. The annual celebration, the Magal, which marks the anniversary of Amadu Bamba’s return from exile, brings hundreds of thousands of visitors to Touba. Mourides living abroad make a special effort to return to Senegal for the celebration, because they can then meet up with the greatest numbers of their comrades and kin.

Touba is a repository of Mouride history. The library there contains Amadu Bamba’s writings, proclaimed by the faithful to weigh seven tons. Guides point out the well where Mame Diarra Boussou, Amadu Bamba’s mother, went to draw water. The tallest minaret is named Lampe Fall, after Cheikh Ibra Fall, the most illustrious of Amadu Bamba’s taalibes. Key events in Mouride history, Amadu Bamba’s visions, and crucial moments from the Mouride past are identified with fixed points at Touba.

Touba is so closely identified with Amadu Bamba that he is called “Serigne Touba.” Moreover, this conjunction of sacred place and person now includes his descendants, and people announce the visit of a cheikh by saying, “Touba is coming to town.”

For Mouride travelers, Touba is the central point to which they always return, yet this center is infinitely reproducible. Throughout their travels, Mourides say Touba is always with them. They carry this sacred place in their hearts. As a young Mouride cheikh said, “Touba is a state of mind.”

A favorite theme in Senegalese art, often depicted in paintings on glass, shows French sailors taking Amadu Bamba away on a boat. Since they refuse to let him pray in the boat, he has placed his prayer rug on the water and is kneeling on the waves, surrounded, in one illustration, by a circle of leaping fish. According to Mouride accounts, when he returned to the boat, the sailors found it was covered with sand from Touba. Mourides abroad continue, in their own way and less dramatically, to recreate Touba in their many settings.

| • | • | • |

Touba in Marseilles

Marseilles is a crossroads for Mouride traders coming from the north (Lyons, Paris, and Brussels) and those heading south for the French and Italian coasts. Many Mouride wholesalers are based here, and “runners” carrying goods from southern Europe, Africa, and as far away as Hong Kong pass through this port city.

The Senegalese live mainly between the Gare Saint-Charles and the port. The tiny twisting streets—rue du Tapis Vert, rue Bagnoir, rue Thubaneau—that spangle the quartier are lined with narrow, shabby hotels and apartment buildings, wholesale stores and warehouses. The people who work and live here are generally not French. Most are from the other side of the Mediterranean—Algeria, Morocco, and West Africa.

This old quarter of the town has been more or less abandoned by the French and taken over by immigrants. Nonresidents who come here are generally looking for drugs or prostitutes, and fights are common. Nights are lively with sirens and flashing lights as police control the neighborhood. They occasionally throw tear gas bombs at groups that have become too large and stop people to demand their identity papers.

Marseilles may be notorious in France because of its level of organized crime, but neighborhoods where Mourides live in other places tend to be similar. Given their need for low rents and proximity to wholesale stores and the train station, it is not surprising that Mourides tend to live in neighborhoods where it is better not to go out after dark.With the heavy police presence and dangerous streets, the Senegalese remain psychologically and geographically enclosed in their quarter. They have little reason to venture out of their neighborhood except on business.

Even a shared Muslim identity does not broaden their social relations. Outnumbered by North Africans, whom they refer to as “Arabs,” and with whom relations are rarely amiable, Mourides stick to themselves. Nor is Mouridism a vehicle out of their narrow lives as it has been for Mouride students, who have made converts among other groups (Diop 1985).

Relations with French neighbors are generally not much better. The French complain, as they do about other immigrant groups, of noise, cooking smells, and irregular hours. In return, the Mouride traders have their own views of the French. “What they’re good for is butter and cheese,” said one peddler.

Another joined in to describe a recent experience in Bordeaux, where a woman had allowed her dog to walk across his wares, saying, “Well, at least he’s from Bordeaux.” In such settings, Senegalese living abroad tend to stick together, creating a place of warmth against an outside world that is so pointedly unfriendly.

| • | • | • |

Inside Mouride Space

For Mouride traders on the road, home is a series of hotel rooms and apartments. In Marseilles, they live in residential hotels that resemble boarding houses, where they typically have developed good relations with the owners. The air of camaraderie, a welcome change from the streets, resembles that of a college dormitory.

Despite Mouride claims that they are never far from Touba, their rooms do not outwardly bear much resemblance to anything in their capital. They do, however, look like every other Mouride immigrant’s apartment. Furniture is minimal, with one or two beds supplemented with mattresses brought out at night. Sleeping two to a bed, and with mattresses covering the floor, the population of the rooms is far above whatever the hotel initially intended. People generally sit on beds rather than chairs. A corner may be designated for cooking, or at least for making tea.

Emblems of Touba are the principal form of decoration. On the walls are posters of Mouride cheikhs, most often a copy of the only photograph of Cheikh Amadu Bamba—a slight figure in white with the end of his turban covering the lower half of his face. Sometimes, there are posters of other important cheikhs. One of the most popular is Cheikh Ibra Fall superimposed on the minaret that bears his name. Other items, equally transportable, are cassettes of the qasidas.

Amet’s room in Marseilles is typical of traders’ rooms everywhere. Because he is a major wholesaler, his room is especially crowded with people and merchandise. He receives visits all day long from bana-bana, who come to buy merchandise from him, to do business, to socialize, and to see the visiting cheikhs who stay with him. Wholesalers and “runners” from Italy, Switzerland, Hong Kong, and New York also meet there.

Amet holds court on his bed, seated on a satin bedspread, handing around samples of the latest arrivals—handfuls of jewelry from Italy or tangled heaps of shoelaces recently arrived from Spain. People come for sociability as well as for business. Several Senegalese come regularly for lunch and are joined by others who gather to drink the three glasses of tea customary during the long afternoons.

Crowded living conditions among migrants may seem due to lack of means, but values attached to sociability and the community also account for the large numbers who may occupy a space. Questioned about his noisy neighbors, a Mouride convalescing in a crowded ward of Bellevue hospital in New York replied, “Il y a ceux qui aiment la paix et ceux qui aiment les gens. La paix c’est la mort” (“There are those who love peace and those who love people. Peace is death”).

The Senegalese, moreover, may count more than one place as home. Their more diffuse notion of family generates a greater choice of places to go to feel “at home.” Migrants abroad may sleep, eat, drink tea, and spend time in different households.

| • | • | • |

Invisible Architecture: Choreography, Time, and Space

Whenever possible, Mourides living in hotels designate rooms for specific purposes. Mbaye’s room in Marseilles is the kitchen where neighbors take turns preparing meals. Amet’s is a favorite place for drinking tea. The largest room is for the weekly da’ira meeting. In New York’s Parkview Hotel, women have transformed their rooms into restaurants, where they sell ceebu jen (Wolof: rice with fish) to street peddlers and hotel residents.

But in these crowded living conditions, sometimes all activities must take place in the same room—praying, eating, watching TV, and doing business. Time, however, can be manipulated in the use of space. The simplest way to expand space, to make a single room serve a number of purposes—meeting room, kitchen, bedroom—is to separate these activities in time. These temporal divisions can be just as effective as spatial ones in separating activities. Occupying a room for a series of different purposes over time (diachronically) is equivalent to occupying several rooms.

Sometimes, however, these activities must all take place in the same room at the same time with no separations in space or time. People are praying, eating, and watching TV in the same room all at once. While these activities are adjacent and simultaneous, a difference in the quality of time separates them. A man unfolding a prayer rug is in a different time-space dimension than the one who is preparing for work. The man facing Mecca and reciting his prayers is linked to all the other times he has prayed and to all others who are praying.

Ritual/religious activities have their own metronome, and more than one metronome may be ticking simultaneously, creating different rhythms, in one space. When space is limited, people who cannot physically separate themselves enter into another measure of time as a way to maintain separations among categories.

The way people move within the space they occupy—their specific choreography—also orders the use of space. For example, upon entering a house, a Mouride shakes hands with everyone, sometimes with the distinctive Mouride handshake, bringing the other’s hand reverently to his forehead, while the other person makes the same gesture. (With a cheikh the gesture is not reciprocal—he only allows his hand to be raised to the taalibe’s forehead.)

This choreography becomes most evident on ritual occasions, when Mourides make a sharper distinction between states and beings considered sacred or polluting. For example, when a da’ira begins, separations between men and women become more important, and they separate to form two discrete groups. Women form their own group, perhaps in an adjoining room, while men come together to form a circle excluding women and non-Mourides. A cheikh’s place is in the middle of the men’s circle. The cheikh is physically set apart from the crowd in other ways, sometimes elevated above the others on a bed or in an armchair, while they sit on the floor (fig. 20).

Figure 20. A visiting cheikh in Paris gives his blessing to taalibes. Photograph by Victoria Ebin.

The choreography, how people move within space, follows the same pattern as the da’ira. The men gather in a circle and begin to sing zikrs, or chants in Arabic, new arrivals advance, approach the group, shake hands, and join the circle. Eventually, their individual shapes merge into one. Shoulders touching, they sway from side to side in unison as they sing.

This new choreography—men coming together in a circle, singing the praises of Cheikh Amadu Bamba—marks a change in mood. People say that singing the qasa’ids brings them closer to Cheikh Amadu Bamba. These sessions are a release from the usual limitations of everyday life (Trimingham 1971: 200). Da’ira meetings are intense emotional experiences that create close bonds and link people into a collective identity (Martin 1976: 2). “Now that we have sung the zikrs and eaten together, we are like that,” one young street peddler said after a da’ira, holding up his fist, “tight and strong.” Using a newly learned English phrase, he said, “All for one and one for all.”

These traders live without a permanent space of their own and travel with few possessions. They do not have a mosque or a sacred place. They sanctify space by their own actions, by making the “inside outside.”

| • | • | • |

A New Choreography: Touba Comes to Town

The arrival of a cheikh from Senegal, the personification of Touba, marks a starting point in a new set of movements. This sacred individual introduces a more formal order into the community, like the jolt of an electric shock to regulate an erratic pulse.

The cheikh’s arrival activates notions of hierarchy, which seem somewhat less evident among migrants than in Senegal, where distinctions such as those based on occupational castes seem to carry greater weight. Far from their families, and without the backdrop of support they provide, the migrants seem more egalitarian. Mouride immigrant life breaks down some of the formality of Senegalese society.

The cheikh’s arrival means that more attention is paid to these distinctions. The observance of these separations creates a different use of space. Separations between men and women and separations based on notions of hierarchy suddenly become more important. Griots (professional praise singers) come forward to sing the praises of the cheikh. Women of the community cover their heads and cook.

Once a year, Serigne Modou Boussou Dieng, a son of Serigne Fallilou, the second khalifa-general of the Mourides, and therefore a major figure in the brotherhood, visits his followers in Europe and America. The cheikh and his entourage travel the Mouride circuit somewhat the way a traveling troupe takes to the road. Every year they follow the same itinerary around Europe—Paris, Lyons, Rome, Barcelona, Madrid—to visit their taalibes.

Like other important cheikhs, Serigne Modou travels with an entourage of family members, always the same during the three years I have seen them in Paris and New York—a younger brother who acts as translator, a young wife who is his preferred traveling companion, a daughter, and her husband, who is also a cheikh. At each stop, they set up house in a lavish hotel, where Mourides come to visit, and, despite their frequent moves, the use of space remains the same.

While in Paris, the cheikh stays in a large apartment in a luxury hotel near the Eiffel Tower. At least three of the hotel staff have become his taalibes during the years he has been staying at the hotel. At lunch time, a fleet of friendly French cleaning women stop by the cheikh’s kitchen for a Senegalese lunch.

The apartment has three bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and two bathrooms. Visitors leave their shoes at the entrance, where a large rug is set out and used for prayers. The cheikh’s brothers share the room closest to the apartment’s entrance, while the cheikh’s wife and daughter receive guests in the adjacent room. Women visitors, who move within a limited space in the apartment, generally wait in this room for the cheikh to receive them. Men, however, move from room to room, sometimes stopping to visit the women. But the only time women enter the men’s room is to distribute food.

The hallway leads into a large living room, where taalibes wait for the cheikh to make an appearance before his assembled visitors, who frequently number from fifty to eighty after work and on weekends. Most visitors, however, are waiting for a private audience with the cheikh, whose small room, entered through the living room, is in the innermost, most protected location in the apartment.

While the apartment’s design is purely European, the use of space is similar to that in a cheikh’s house in Touba. According to this plan, the cheikh’s or ruler’s house consists of an enclosure built around a series of concentric circles or squares, with the cheikh in the most interior, protected space.

In his Esquisses sénégalaises, Abbé Boilat describes how the plan of a mid-nineteenth-century house protected the Wolof king. “At the entrance is a large courtyard with armed soldiers at the door. One must pass through several such courtyards to arrive at the prince’s’s room; in each courtyard one traverses a house which serves as a sort of guard. The house of the sovereign is always at the end of the enclosure” (Boilat 1984 [1853]: 292).

The abbé’s description of his visit to the queen of Walo in northern Senegal in 1850 shows how royal protocol organized the use of space. “We were obliged to wait an hour in the first court; a half-hour in the second; another half-hour in the third; finally, at 4:00 we were received by the prince, the husband of the queen.…It was only at 6:00 that the queen was visible;…we entered a large courtyard where Her Majesty was seated, smoking her pipe of honor, surrounded by more than 500 women” (Boilat 1984: 293).

Visitors to Serigne Modou in his Paris hotel must pass through similar protocol, which is often equally lengthy. The outer door of the hotel suite in Paris, as well as the entrances to each room, are station points for guards. In the small foyer at the main door, the cheikh’s younger brother is always present, greeting taalibes, sometimes giving blessings, and also receiving offerings. The new arrivals, especially if they are close to the cheikh’s family, may visit the young cheikhs in their room while waiting to see Serigne Modou Boussou Dieng.

All visitors must pass by an individual known as the bëkk néeg, or “confidant of the king,” who controls access to the cheikh (Fal et al. 1990: 44). According to a Wolof proverb, a marabout needs more than one set of ears: the bëkk néeg is his second set. One bëkk néeg is stationed at the entrance to the living room and another is in front of the cheikh’s private room.

In both the Paris hotel and the nineteenth-century king’s house, the bëkk néeg choreographs the passage of visitors. He protects the space around the cheikh by guiding visitors to where they must wait and informs them when the cheikh is ready.

As in the nineteenth-century palace, the bëkk néeg choreographs the passage of visitors in the Paris hotel suite. He protects the inviolable space around the cheikh by directing the flow of people. In the past, the design of the king’s house, with its series of concentric courtyards and guards, maintained a distance between him and visitors. Today’s cheikh in a hotel suite is protected by a choreography that fulfills the same function.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion

The Mouride brotherhood is an example of a highly centralized body, organized around a hierarchy of saints, with the khalifa-general at its peak and Touba at its conceptual center. It is now also a highly mobile society (taalibes and cheikhs in a state of continuous motion) that places high value on solidarity and collective identity.

Itinerant Mourides reproduce aspects of this structure wherever they are. Touba multiplies and is recreated by a sort of spontaneous generation, which occurs when conditions are right—that is, when Mourides invoke its presence. These replications of Touba can be ephemeral, such as the ambience created at a da’ira or during the visit of a cheikh, or semipermanent, as they are in a hotel room where Mourides live. In creating their space, Mouride traders do not construct buildings or alter the arrangements of their space, but an invisible architecture structures their use of space just as clearly as walls and courtyards.

Three features seem essential to creating Mouride space. First, they bring Touba and everything it connotes—the mosque, Cheikh Amadu Bamba, the home of the saints—into their present space. The frequent visits of their cheikhs—when “Touba comes to town”—reinforce Touba’s presence. The invariable objects in their living places—posters, tapes of the qasa’ids, the highly spiced “Touba” coffee—refer to the sacred town like a series of mnemonic notes.

Mourides carry Touba in their hearts. At the da’ira meetings, their chants and songs make the “inside outside.” They claim that singing the poems of Amadu Bamba transforms the space where da’iras are held, creating sacred space and unity.

Second, the presence of other Mourides is essential. In creating space that is specifically their own, the group, or, as they say, “being numerous,” is crucial. Mourides claim that everything is better when it is shared—eating, praying, and singing. Singing the zikrs and the qasidas brings Mourides together, physically and spiritually, binding them into a collectivity, the very foundation of their invisible house.

Finally, Mouride choreography, observing separations between sacred and polluting categories, is necessary. Divisions between these categories are maintained through specific strategies in the use of space and time.

Mourides claim and appropriate space as their own by recreating Touba, observing their specific choreography and simply being in a space—a Mouride surrounded by other Mourides. Minimal is the only word to describe their living conditions, and the transformation of space into specifically Mouride territory depends on its occupation by Mourides.

Singing the zikrs, the foremost example of how Mourides transform space, can be done anywhere, in a train station, a hotel lobby, an airport. By this activity, they mark space and make it theirs. They do not need to possess space to make it their own. The paradox is that despite their patent lack of it, they constantly create space through their presence.

Notes

1. This study focuses on Mouride men, because at the time of my fieldwork in New York and Marseilles in 1986–88, few women were involved in trade. Recently, however, the number of Mouride women traders has grown.

2. In 1895, Amadu Bamba had 500 followers; in 1912, a French official estimated their number at 68,350; by 1952, the figure had risen to 300,000, and by 1959 to 400,000 (Monteil 1966: 370).

3. Cruise O’Brien 1988: 137. For a discussion of the divisions among Mourides in Paris, see Diop 1985. For a comparison with Mourides in New York, see Ebin 1990.

4. Xam-xam is defined as knowledge, understanding, science (Fal et al. 1990: 250).

5. The importance of Touba for Mourides is highlighted by comparison with the behavior of migrants from northern Senegal in Paris, who form associations to carry out collective projects in their home villages; they build dispensaries and make village gardens. Mourides, on the other hand, make their collective donations to Touba.

6. Cruise O’Brien 1971: 47, 41–137. While other roots for “Touba” are possible, such as tauba (repentance) or tuba (a tree in Paradise), Mouride informants invariably define it as “sweetest” (Cruise O’Brien 1971: 47).

Works Cited

Behrman, Lucy. 1985. “Muslim Brotherhoods and Politics in Senegal in 1985.” Journal of Modern African Studies 4: 715–21.

Boilat, Abbé David. 1984 [1853]. Esquisses sénégalaises. Paris: Karthala.

Cohen, A. 1971. “Cultural Strategies in the Organization of Trading Diasporas.” In The Development of Indigenous Trade and Markets in West Africa: Studies Presented and Discussed at the Tenth International African Seminar at Fourah Bay College, Freetown, December 1969, ed. Claude Meillassoux. London: International Africa Institute.

Cruise O’Brien, Donal B. 1971. The Mourides of Senegal: The Political and Economic Organization of an Islamic Brotherhood. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

——————. 1989. “Charisma Comes to Town: Mouride Urbanization, 1945–1989.” In Charisma and Brotherhood in African Islam, ed. Donal Cruise O’Brien and Christian Coulon, pp. 135–55. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Diop, A. M. 1985. “Les Associations murid en France.” Esprit 6: 197–206.

Ebin, Victoria. 1990. “Commerçants et missionaires: Une Confrérie musulmane sénégalaise a New York.” Hommes et migrations 1132: 25–31.

——————. 1992. “A la recherche de nouveaux ‘poissons’: Strategies commerciales mourides par temps de crise.” Politique africaine 45: 86–98.

Fal, Arame, Rosine Santos, and Jean Leonce Doneux. 1990. Dictionnaire Wolof-Français. Paris: Karthala.

Fatton, Robert. 1987. The Making of a Liberal Democracy: Senegal’s Passive Revolution, 1975–1985. Boulder, Colo.: Lynn Rienner.

Martin, Bradley. 1976. Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Monteil, Vincent. 1966. Esquisses sénégalaises. Initiation et études africaines, 11. Dakar: IFAN.

Nguyen Van-Chi-Bonnardel, Regine. 1978. La Vie de relations au Sénégal: La Circulation des biens. Dakar: IFAN.

Renaudeau, Michel, and Michelle Strobel. 1984. Peinture sous verre du Sénégal. Paris: Nathan; Dakar: Nouvelles editions africaines.

Samb, Papa Boubacar. 1992. “Du grand bazar à Taksim: Un petit coin du Sénégal.” Le Soleil (Dakar), August 22–23.

Trimingham, J. Spencer. 1971. The Sufi Orders in Islam. Oxford: Clarendon Press.