5. Reinventing Mount Lebanon

The violence of 1841, which initially pitted the Christian villagers of Dayr al-Qamar against their returning Druze shaykhs, unleashed an open-ended struggle among elites over the meaning of tradition. Chroniclers and clergymen, notables and Ottoman officials, and, with overbearing confidence, foreign missionaries and European consuls—all those who intervened in and shaped recorded history—debated how best to bring tranquillity to Mount Lebanon. In the spirit of the Tanzimat and in accordance with the principles of restoration, they agreed on one thing: that order in Mount Lebanon would not infringe on its “ancient custom.” The problem lay in defining this custom and agreeing on what constituted tradition. Even before Bashir Shihab’s death in exile in 1850, the meaning and memory of his long and complex reign had become completely ensnared in a struggle for succession that owed more to an invention of tradition than to tradition itself.[1] As strongly as the Maronite Church favored the restoration of a putatively Christian emirate, the Druze notables who had borne the brunt of Bashir’s ambition vehemently opposed it. The hapless Bashir Qasim pleaded his own cause. At its simplest, the issue that divided the elites was land. Who was to control it? to rule it? to administer it? At its most complex, the issue was reconceptualizing this land and the communities that inhabited it. In the process, and in the shadow of a European-Ottoman concern for progress, Mount Lebanon was geographically reconfigured and communally reinvented.

Various elite efforts following the violence of 1841 to reinscribe strict political and social boundaries reached their climax in December 1842 with a joint European-Ottoman decision to partition Mount Lebanon along religious lines. In 1845, the Ottoman foreign minister, Şekib Efendi, further reorganized Mount Lebanon’s administration along communal lines. This chapter explores how the elites began to politically reconstitute themselves in allegedly traditional sectarian terms while the very basis of tradition—absolute Ottoman sovereignty which existed “for all time”—was being undermined at every turn. I contend that an informal subjecthood to European powers developed alongside formal subjecthood to a changing Ottoman state. Although the Sultan remained sovereign over Mount Lebanon, the presence of Jesuit and American Protestant missionaries and of agents such as Richard Wood tacitly widened the domain of obedience to include France and Great Britain. Unlike their relationship with their Sultan, which was marked by an allegiance supposedly impervious to the passage of historical time, local elites nurtured an informal alliance with foreign powers very much defined by historical evolutionary time. Not only was the interaction between the Maronite elites and France, to give an example, validated by specific historical documents or treaties, such as Louis XIV’s letter of protection to the Maronites in 1649 and the Treaty of Paris of 1856, but it was increasingly articulated through a discourse of progress and civilization. Neither Maronite nor Druze leaders sought to break with the Ottoman Empire, but each recognized individual European powers as the protectors of their community and as arbitrators of their political destiny, as players who could influence the course of politics as much as and, in some cases, more than the Sultan himself.

Mount Lebanon was communally reinvented in the sense that a public and political sectarian identity replaced a nonsectarian politics of notability that had been the hallmark of prereform society. This shift was not nearly as simple or as complete as many observers have assumed. Historians have elucidated many factors that aggravated the situation, including the Egyptian invasion, the Eastern Question politics, and the rise of the Maronite Church, but they have all assumed that these historical causes cleared the way for the reemergence of a coherent, primordial religious identity. They have not examined the anxiety inherent in this new elite sectarian project; nor have they sufficiently noted its obvious contradictions, its tentativeness, and its underlying fragility.

In large part, historians have missed these factors because the sources they have relied on have taken communal identity for granted. The voluminous European consular correspondence on the sectarian strife, which forms the backbone of most modern historical narratives of this period, is a plethora of invaluable reports, dispatches, letters, and memoranda. Historians have sifted through these and have disinterred the complex politics behind the correspondence, and they have elucidated why and how the powers acted in the way they did; they have cross-checked sources to produce consistent and balanced narratives, stripping away the conceit of each European power to represent all local history. But they have left undisturbed, indeed they have reproduced, the single greatest fallacy of such historiography: the notion of the pure communal actor.

| • | • | • |

Narrating Violence

The most preponderant treatises on sectarian violence were those produced by the European powers. In 1842, Lord Howden of the House of Lords, demanded to know what the British government planned to do about the situation of “anarchy” that had rendered movement in Syria as difficult as traveling “in the interior of Africa.”[2] The only answer Lord Aberdeen could provide with any assuredness was that Britain would redouble its urgent remonstrations about the pace of Ottoman reform.[3] From the outset, British observers resorted to an Orientalist knowledge to comprehend the events that unfolded in Mount Lebanon. “Disputes about the possession of land and trivial matters,” wrote consul Hugh Rose, “were the causes of quarrel between the two sects, whose mutual animosity is proverbial.”[4] Lord Aberdeen elaborated on these sentiments in a dispatch to Stratford Canning, the British ambassador in Istanbul:

Although they cast the fanatical antimodern “Turk” as a figure who in his shadowy manifestations cunningly and secretly desired to upset the path of reform and to harm Christians, British diplomats conceived of the sectarian “tribes” of Mount Lebanon as unmodern. In their eyes, Druzes and Maronites did not fight a rational war; they reenacted an ancestral conflict.The enmity between the Druses and the Maronites of Mount Lebanon is of ancient date. A difference of religious belief, added to a struggle for political supremacy between two parties, the numerical superiority of one being more than counterbalanced by the warlike qualities of the other, has continually produced contests between them. Of late years the oppressive rule of Mehemet [Mehmed] Ali, acting nearly equally upon both, maintained peace between the rival parties; but their jealousies and animosities revived on the departure of the Egyptians, and have brought about the warfare which has desolated the Lebanon.[5]

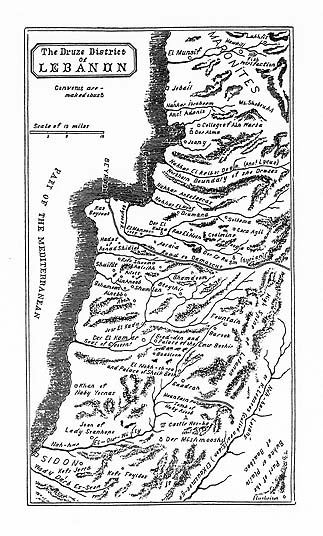

Map 4. The Druze District of Lebanon. (Reproduced with permission from The Missionary Herald: Reports from Ottoman Syria, 1819-1870, ed. Kamal Salibi and Yusuf K. Khoury: Amman, Jordan: Royal Institute of Interfaith Studies, 1995; originally appeared in The Annual Reports of the ABCFM, vol. 35, 1844).

By underscoring the “proverbial” mutual animosity of Muslim and Christian, consul Rose, who had arrived in Syria as part of the Allied forces in 1840 and whose knowledge of local history was sketchy to say the least, instinctively drew on another of the basic European assumptions concerning the Ottoman Empire: the inherent Islamic hostility toward Christianity. Rose insisted that the Druzes were pawns of a lurking Ottoman Muslim fanaticism that desired to destroy Christianity in the East. As Canning told Aberdeen, “Mr. Moore and Mr. Wood agree with Colonel Rose and the other Consuls at Beyrout in describing the revived fanaticism of the Turks, their mistrust and increasing hatred of everything Christian and their secret preparations for defence against Foreign aggression.”[6] British and French attitudes toward the local violence marginalized the spontaneity of the violence and minimized the agency of its perpetrators. European consuls invariably blamed the violence on alleged Ottoman negligence, or, more frequently, they referred to an insidious Ottoman plot to provoke Druzes and Maronites into a war in a bid to reassert direct rule in Mount Lebanon.[7] Their emphasis on supposed Turkish machinations gave structure to the chaotic events that transpired on the ground.[8]

France had a far less ambivalent attitude than Britain, which was torn between sympathy for the Druzes as a counterweight to French influence on the Maronites and concern for the rights of Christians. The French government was busy trying to mend bridges with the Maronites following the debacle of French support for Mehmed Ali in 1840.[9] For their part, the Jesuits, who had enjoyed amicable relations with the Egyptian authorities, shuddered at the prospect of restored Ottoman rule. Following Druze attacks on Jesuit outposts in the Bekaa in 1841, Benoît Planchet, the Jesuit missionary who had arrived in the early 1830s, wrote that the true “goal” of the Druzes was to drive the Christians out of Mount Lebanon entirely.[10] For Planchet, the dimensions of the catastrophe were all too clear: the Ottomans secretly supported the Druzes in their efforts to reduce Mount Lebanon’s freedom and to reinstate the “despotism of past times.” The Ottoman appointment in early 1842 of Ömer Pasha to directly rule Mount Lebanon in place of Bashir Qasim confirmed Planchet’s worst fear: “Little by little the habits, manners and law of the Muslims will be introduced into the Mountain. It will no longer be what it was: a place of liberty for the Catholic religion, a refuge for persecuted Christians and converts from Islam.”[11]

To Planchet and the rest of the Jesuits, to Rose, to Canning, to the French consul Prosper Bourée and to France’s ambassador in Istanbul, the Baron de Bourqueney, the intervention of Europe was imperative. What was at stake in Mount Lebanon was not simply the resolution of an age-old tribal conflict but the course of modernity, which now stood at a cross-roads. The Ottoman decision to appoint Ömer Pasha forced the European powers to temper their own rivalries and to underscore their commitment to the “just claims of the Christian Powers.”[12] In a series of “joint notes,” the European powers demanded a non-Ottoman government in Mount Lebanon despite the fact that several European observers recognized that direct Ottoman rule might indeed have been best for security and order.[13] Canning again invoked the native state of mind. He claimed that such Ottoman rule not only was in “direct contradiction with the spirit and principles of the later intervention” but “could only be acceptable to the inhabitants while their natural feelings are perverted by local and temporary passions.”[14]

Yet since these local “passions” threatened to lead to further violence, some solution had to be found immediately. With this in mind, the European ambassadors converged in the spring and summer of 1842 in Istanbul to finally settle the problem of sectarian violence. Despite their own quarrels, the ambassadors agreed that they had nothing but “benevolent views” to offer the Sultan on his tentative course toward “modern civilization.”[15] Not for a moment did they pause to reflect on their understanding of the task at hand. They insisted that the origin of the recent violence lay in the murky primordial past—a past, they hastened to add, which the tribes of Mount Lebanon in some senses still inhabited and one for which many fanatical “Turks” still yearned.

Joining them in Istanbul were numerous Ottoman representatives led by the foreign minister, Sarim Efendi. Ottoman officials reacted to the sectarian violence by referring to the Lebanese communities as if they were on a progressive spectrum. At one end was the Sultan, enshrined in Ottoman discourse as the all-powerful patriarch of the Ottoman nation, who had benevolently reached out to all his subjects through the Tanzimat. At the other end were the Druzes and Maronites, “two sects [that] are full of sedition and abominable wickedness,” stressed one Ottoman report, “deserving all reproach.”[16]

Such excoriations of the Lebanese communities masked the unease and frustration evident in the dispatches sent from the restored province by its governors and military commanders. The acute awareness of Ottoman officials that European powers intervened through sectarian lines [mezhebdaşlık vesile] reinforced their belief in the crucial importance of centralization.[17] To them, the violence in Mount Lebanon served as a poignant example of the backwardness of the periphery of their empire. Instead of the fanatical “Turk” being the antimodern, as in European concepts of modernity, now it was the Lebanese sects who served as a foil for a modernizing Ottoman identity. “Because blood feuds are so important to the inhabitants of rural Syria, as they are for the Albanians,” read one dispatch concerning the activities of a Druze notable, “[he] acted in accordance with the proclivity of his race.”[18] Like the Europeans, Ottoman functionaries classified the Lebanese struggles as age-old; like the Europeans, the Ottomans insisted that they sought only to restore order and tranquillity.[19] But unlike the Europeans they had neither a clear sense of mission nor an overwhelming confidence in their ability to have their commands obeyed.

To be sure, the Ottoman authorities differentiated metropole from periphery and indiscriminately lumped together Yezidis, Druzes, and Albanians; they nevertheless framed their discussion of Mount Lebanon as a tale of imperial survival. It was not simply that the Druzes and Maronites were involved in an ancient conflict that would continue “until the Day of Judgement” but that their disputes threatened the foundations of empire by inviting European interference.[20] On one level, therefore, the Ottoman reaction to the violence may be read as evidence of a state in transition and an empire caught between two worlds and two times. As the imperial honorifics that gilded the Sultan’s name suggested, one world evoked a former grandeur embedded in the idea of absolute Ottoman sovereignty that endured across, and hence defied, the passage of historical time. The other world was one in which time had passed the empire by or at least threatened to pass it by; it was a world of European domination and intervention, of Mehmed Ali’s modernization schemes, and of a growing sense of the backwardness of the empire—the sum of which produced the Gülhane decree. This sense of transition was inscribed in the dispatches themselves.

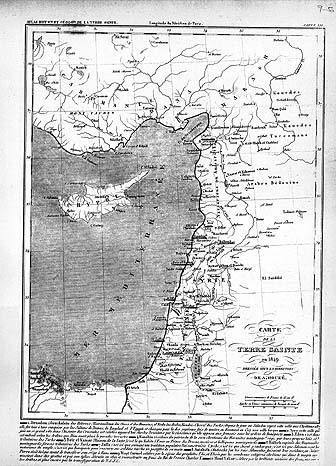

Map 5. Carte de La Terre Sainte en 1849. (From Antoine Philippe Houzé, Atlas universel historique et géographique. Paris: Librairie Universelle, 1850)

Men like Mustafa Pasha, commander of the Ottoman army, who was sent in late 1841 to settle the affairs of Mount Lebanon following the sectarian clashes, epitomized the Ottoman predicament. He began his mission with a reassertion of social order.[21] He summoned the söz sahibleri to Beirut and relieved Bashir Qasim of his powers; he informed the notables that the return of the Shihabs was out of the question and announced the appointment of Ömer Pasha—a high-ranking Ottoman officer of Croatian origin and a member of Mustafa Pasha’s staff—as governor of Mount Lebanon.[22] Beyond reasserting Ottoman authority in the name of the reforming Sultan, Mustafa Pasha symbolically and physically broke with the old regime by finally abolishing the Shihab dynasty, which had ruled since 1697. Yet this rupture was not complete, for although the Tanzimat was concerned with building a modern nation, little in the dispatches indicated how this modernization was to be accomplished.[23] Precisely because the Tanzimat lent itself to a variety of interpretations, including a European one that mandated interference, the Ottomans considered the reorganization of local administration imperative for stifling European involvement.[24] The Tanzimat placed the Ottomans in a quandary, for while they repeatedly pledged to obey the Sultan’s will to reform, they viewed the natives as essentially unreformable subjects. Ottoman officials were certain, however, that reform and state violence went hand in hand; public order and security could be guaranteed only by bringing local notables to heel and by removing their “stupid, silly and fickle” followers from the realm of politics.[25]

| • | • | • |

Using the Past

Far from being passive objects of the search for a political solution, the local elites deftly took advantage of imperial concern to cling to what they considered their birthright: property, prestige, and a monopoly on politics. As they outmaneuvered one another, they gave credence to the narratives reverberating in London, Paris, and Istanbul. Both Druze and Maronite elites found that their desire for power, and their equally tenacious conviction that only one of them deserved to wield it, could best be served by representing themselves as the guardians of tradition and social order and their rivals as the instigators of perennial perfidy. Druze notables declared themselves at once to be ardent Muslims loyal to the Sultan and faithful allies of Great Britain.[26] Maronite leaders proclaimed that they were, in fact, the dutiful supporters of the House of Osman at the same time as they appealed to France in the name of Christian solidarity.[27] Both laid claim to the mantle of loyalty, and both deployed any number of languages of legitimacy, particularly those of faith and loyalty, to bolster their respective causes.

Following the fighting at Dayr al-Qamar in 1841, the Maronite Patriarch “reminded” the Sublime Porte that Bashir Shihab and the Christians of Mount Lebanon had always been loyal to the Ottoman state and that it was the Druzes who had betrayed the Sultan and sided with the Egyptians; it was only when the Druzes realized that Ibrahim Pasha’s army was doomed that they switched sides, but in Dayr al-Qamar their true colors were revealed.[28] For his part, the Druze shaykh Khattar al-‘Imad submitted a petition to the Ottoman government in which he outlined his understanding of the same events. The Druze leader framed his discussion as an epic battle between “the sword of Islam,” which he claimed the Druzes wielded with great pride on behalf of the Sublime Sultanate, and the enemies of Islam, represented by the European-supported Maronites. He stated that “abandoning the law of Islam, the heretics intended to weaken Islam and [replace it] with the ways of the infidels, and to hand over the country to the brigands.” The prospect of such corruption, of heresy replacing faith, “depressed our souls and filled our hearts with disgust,” and so the battle commenced between the Druzes and the ahali of Dayr al-Qamar.[29]

What matters here is not the truth of these claims but their underlying similarity and their mutual commitment to and dependence on a hierarchical social order to explain events. ‘Imad’s citing of categorical religious difference should not obscure his awareness of an essentially social struggle. He freely admitted that the conflict began when the Druze muqata‘jis attempted to collect the miri tax from the recalcitrant villagers, whom he contemptuously described as “all along being our lowly and abject [Christian] subjects.” And he wondered, given this history, “in what conceivable manner could such behaviour from wretched villagers be endured.”[30] It was not the Christianity of the villagers that worried him; it was their inversion of social order at the behest of the Shihab emirs and foreign agents.

‘Imad’s concern and his repeated references to foreign agents indicated that the rituals of old-regime politics were now being played on a new stage—“a theatre of intrigue,” as an American missionary put it—erected after 1840.[31] The flurry of appeals to different powers marked the attempt by the local elites to appreciate and adjust to its contours. The tempo of politics had changed; so too had its stakes. In an era of progressive time, the elites were terrified of being outmaneuvered and left behind in an avowedly modern world. Hospitality was extended to foreigners—to consuls, to merchants, and to missionaries—not simply as a courtesy to strangers from distant lands but as an imperative for survival. Both Druze and Maronite leaders realized that European power could be profitably and decisively turned to their own advantage. They had seen Ibrahim Pasha’s modern army destroy several Ottoman armies, only to be crushed by still greater and more modern European forces.[32] They were well aware that European ships had liberated Syria; European agents had supplied an estimated forty thousand muskets to the region; and European (and American) missionaries provided much-sought-after modern medicine.[33] Trade opportunities also increased, and notables provided land and labor for newly established silk factories. In return, Europeans and Americans showered both groups with such attention that it deluded them into “thinking that they were something important in this world,” in the words of the French consul Bourée.[34] They were given vistas into a much wider world and the illusion that they were major players in it.

Above all, however, the local elites knew that in the post-Tanzimat world this power was to be had only along sectarian lines. The objective of Druze and Maronite elites was not to confirm European or Ottoman attitudes toward them but to manipulate the concern for a reestablishment of order by presenting themselves as the only genuine interlocutors of the so-called primordial sectarian communities that inhabited Mount Lebanon. They sought to transform their religious communities into political communities and to harness invented traditions to their respective causes. The construction of a political sectarian identity did not come naturally; it entailed petitions, meetings, and the incessant application of moral as well as physical pressure by the leaders in each community to overcome local rivalries, regional differences, and family loyalties.[35] Maronite and Druze elites each strove to present a unified front to the Ottoman state and the European powers, effectively ignoring a long history of nonsectarian leadership.[36] The Maronite Patriarch was well aware of the difficulty of marshaling the Maronites into an organized political community, especially when an Ottoman commissioner, Selim Bey, was sent to Mount Lebanon in 1842 to determine whether the local population was in favor of direct Ottoman administration. The Patriarch made it clear that “we will not accept, do not desire and will not be content” with any ruler except a Christian Shihab. Although he insisted that such rule over Lebanon followed “our custom and ancient regulations,” the Patriarch also requested a delay in the fact-finding mission. He admitted that he needed time to gather the respectable faces (awjuh) of the people before the opinions of the ahali were ascertained. The Patriarch conceded that several Christian notables had already submitted or were about to submit petitions that opposed the return of a Shihab ruler. These, he told Selim Bey, must be ignored; only a Shihab emir must be in overall command. The other shaykhs should be confirmed in their traditional prerogatives but not as rulers over Mount Lebanon.[37]

The process of sectarianizing identity was immensely complex. New sectarian fears and possibilities still had to contend with old-regime solidarities and geographies. Knowledge in prereform society had always been deployed in the service of power, but it had been hegemonic knowledge. The secular division between the söz sahibleri and the ahali, the rule of a Shihab emir, the respect for social rank, and the total obedience to the Sultan were the accepted bases of nonsectarian politics. They accommodated religious and regional differences and gave expression to, as well as found expression in, a genealogical geography of Mount Lebanon. For a sectarian politics to cohere, for it to become hegemonic in a Gramscian sense, it would have to become an expression of everyday life; it would have to stamp itself indelibly on geography and history. In this task, as with so much else in this era of reform, the interplay between local and foreign played an immeasurable role.

| • | • | • |

Sectarianizing the Landscape

The European and Ottoman characterization of “age-old” religious turmoil not only absolved the European powers and the Ottoman Empire of any responsibility for the violence but reflected their ardent conviction that they alone knew this region and that they alone could properly reform it. The repeated Ottoman references to the zabt ü rabt, discipline which orders and restrains, necessary for the good government of unruly Mount Lebanon, were echoed in Lord Palmerston’s declaration before the House of Commons in 1845 that “when such men are intermixed, as they are in Lebanon, occupying the same village, dwelling on the same land, constantly meeting in the same town, it evidently requires a vigorous hand, a powerful head, a strong, determined will, together with sound judgement, to repress the tendency to disorder which must exist in such a state of society.”[38] European and Ottoman concern for an allegedly native disorder mandated a decisive effort to rebuild a sectarian orthodoxy where none had previously existed.

Throughout 1842 the European ambassadors and Ottoman foreign ministry officials and military commanders met and debated the issue of communal violence. Throughout that year the fate of Mount Lebanon hung in the balance. The Lebanese notables waited for word of the decisions of the Great Powers and the Sublime Porte. In May and June, conferences convened and adjourned, with the European powers and the Ottoman government unable to agree on the exact formulation of the new sectarian order. The Europeans, led by Canning, urged the partition of Mount Lebanon along religious lines. The Ottomans were opposed; they insisted that the population was far too mixed for an effective partition.[39] Canning, who had never visited Mount Lebanon, dismissed Ottoman concerns for the “extraneous population”—that is to say the population who marred the logic of partition by living in religiously mixed villages. When the Ottomans again tabled proposals for direct Ottoman rule and rejected partition on the basis that it would “prove to be a fresh element of disorder,” the exasperated European ambassadors implored them “to take a more statesmanlike view of the question.”[40] Meanwhile, Lord Aberdeen urged Canning not to relent. “I have been informed that difficulties would attend the execution of this plan, in consequence of the great intermixture of the Druses and Maronites which might under their separate government [be] scarcely practicable. This may certainly be the case in particular districts, and some means must be devised to remedy the inconvenience.”[41]

Faced with an intransigent European position, Sarim Efendi, in a September meeting at his summer house which lasted more than six hours, asked the assembled ambassadors if the “Powers have the intention of imposing their will on the Porte.” The French ambassador said no. Speaking for all the ambassadors, he stated that they were only offering “advice” and, in turn, wanted to know whether the Porte wanted to establish regular relations with “Europe.”[42] Finally, on December 7, a beleaguered Sarim Efendi conceded the point. The Sublime Porte accepted the idea that Mount Lebanon would be formally divided; however, it added ominously that it thought the plan was a recipe for disaster.[43] So the ambassadors and a reluctant Ottoman government together made a fateful decision that created a sectarian geography in Mount Lebanon. Like Salman Rushdie’s “midnight’s children,” Cebel-i Lübnan—a term that came into Ottoman usage at precisely this time—was born to signify a new beginning for the region, but also a tragic inheritance.

Ömer Pasha’s short tenure as governor came to an abrupt end. Mount Lebanon was cut in half. The Northern district (nasara kaymakamlığı) was meant to be a homogenous “Christian” area ruled by a Christian district governor (kaymakam), and the southern district (dürzi kaymakamlığı) was to be a distinctly “Druze” region ruled by a Druze district governor. Ottoman officials estimated that the population of Mount Lebanon was roughly two hundred thousand, of which the Druzes constituted forty thousand. With the exception of the Matn district, where many Druzes resided, the vast majority of the inhabitants of the northern Christian district were Christian. The problem lay in the southern Druze district, where the Christians also formed a majority, with the exception of the Shuf, in which Dayr al-Qamar was located.[44] The Maronite Church continued to press for Maronite Christian rule over all of Mount Lebanon, whereas Druze elites staunchly opposed handing over any power to Christian villagers. While they acknowledged that the Christian population had increased over the years, Druze notables insisted that the villages were built by their own ancestors and, hence, belonged to them. Two myths, each distilled from a grain of truth, confronted each other: the first was the Maronite Patriarch’s claim that tradition sanctioned “Christian” rule over all of Mount Lebanon; the second was the Druze kaymakam’s claim that tradition consisted of a benevolent patriarchy “because the notable considers the inhabitants of his district as if they were his children, and [they, in turn] consider the notable a father.”[45]

Such are the irrefutable facts that boldly present themselves: partition was not a local decision, and the natives were not consulted but were depicted as savage mountaineers incapable of solving their own problems. To this extent at least, what followed in Mount Lebanon over the next two decades should be interpreted in light of the arrogance of imperial powers who dismissed as an “inconvenience” centuries of native coexistence.[46] It is also clear that with partition the very notion of coexistence became a vexing issue in a society increasingly defined along religious lines. The logic of partition demanded the unambiguous classification of the local inhabitants into one or another camp, either Christian or non-Christian. The European-designed partition plan assumed that there were in fact two distinct and separate primordial tribes of Druzes and Maronites to which all Druzes and all Maronites instinctively adhered. Leaving aside the fact that Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic communities resented being under Maronite tutelage, the partition legitimated sectarian politics by organizing the administration and geography of Mount Lebanon along religious lines.[47]

Although both Maronite and Druze elites were unhappy with the partition decision (for it satisfied neither the Maronite demand for a return of the Christian Shihab emirate nor the Druze claim that they were the original proprietors of Mount Lebanon), the rival elites quickly adapted to the fait accompli of partition. They still maintained their old-regime rank and titles, and yet they were fully aware of the high stakes involved in acting as leaders of separate nations. Whichever side could convince the European powers and the Sublime Porte of the justice of its cause as a coherent community would win the bounty of land and control of the mixed villages. Partition provided a new setting for a familiar story of elite rivalries, but it changed the nature of the rivalry, the representation of the rivals, and the definition of local communities. New categories of “Christian” or “Druze” rule were created alongside the idea of “mixed” villages and “minorities.” European consuls and missionaries involved themselves more than ever before in the minutest details of everyday politics; at the same time, they were actively sought out by local elites to mediate among them.

| • | • | • |

Sectarian Paths of Development

Violence and partition cleared the way for sectarian paths of development. Now that Mount Lebanon was geographically reformed, the fractious elites, the Ottoman government, and the foreign missionaries began to think of how to construct a modern society. The discourse of restoration flowed into a discourse of progress. The question was no longer simply how best to return to tradition but how to use knowledge of the past to build a stable future. A number of quite different schemes were proposed, all guided by the assumption of an untraversable difference that separated Druze from Maronite and all consumed with the idea that religion was the single most important political identification of each villager. Some schemes, such as the Maronite Bishop Nicolas Murad’s 1844 tour of Europe as well as his polemical writing, represented a vision of a Christian-dominated Mount Lebanon in which Druzes were included in a subordinated position. Other schemes involved diplomatic efforts to build a sectarian administration in an attempt to reconcile allegedly ancient differences by creating a religiously balanced public sphere. Still others, such as the Jesuit efforts to reform local Christianity, worked in precisely the opposite direction, for they promoted segregated Christian spaces. The upshot was that history, politics, and education—which in the old regime had reinforced a nonsectarian hierarchical social order—were all put to work to create a sectarian hierarchical social order. I want to draw attention here to the ambivalence of this process—to the novelty of these projects of reform, which tried to reorganize physical and cultural space in accordance with a sectarian vision of the past, and to the underlying tension between the legacy of imperial sovereign time and the arrival of progressive time. This ambivalence becomes particularly clear if the disparate sectarian projects are analyzed side by side, that is to say, in and as moments of production rather than as coherent reflections of objective conditions.[48]

Nowhere was this tension more manifest than in new local histories. Unlike the old-regime chronicles, historical writings in the postreform era displayed a variety of narrative forms and addressed foreign and domestic audiences. They reflected both formal and informal subjecthood. Perhaps not surprisingly, the period between 1840 and 1860 produced one of the first teleological histories, Nicholas Murad’s Notice historique sur l’origine de la nation Maronite et sur ses rapports avec la France, sur la nation Druze et sur les diverses populations du Mont Liban, and the last of the sweeping historical chronicles, Tannus al-Shidyaq’s Kitab akhbar al-a‘yan fi Jabal Lubnan.[49]

While Shidyaq’s history, which was first published in 1859, presented a definitive history of the old regime—it was almost exclusively preoccupied with the genealogy and history of the notable families of Mount Lebanon—the work of Maronite Bishop Murad represented a vision of a new Christian regime.[50] Murad himself in many ways embodied the transition from the old-regime politics of notability, in which he began his career teaching the children of local notables, to an emerging sectarian order, in which he became the most eloquent spokesman for a communal vision of Mount Lebanon. Murad was a man comfortable both in an Ottoman and in a European context. In a meeting with the Ottoman foreign minister, he stressed Maronite obedience and loyalty to the Sublime Porte. To “Europe,” however, he appealed in the name of Christendom in his 1844 Notice historique. Murad’s Notice also heralded a significant rupture in both its narrative form and its content. The Notice was a polemic that presented a coherent sectarian vision of the history and future of Mount Lebanon; written in French and addressed to Louis-Philippe, it interpreted the sectarian violence as a Christian struggle for survival—a saga of the Maronite ta’ifa as a nation that was attempting to take its rightful place alongside the European Christian states. The Notice fused a European nationalist idea with a tradition of Maronite ecclesiastical autonomy to present the case for a Maronite-dominated Christian Lebanon.

Murad’s Lebanon, like that of the European travelers before him, was a mountain refuge that had long held out against the Saracens and other infidels as an “independent” Christian principality. After making the claim of Maronite orthodoxy and unwavering devotion to Catholicism and emphasizing the Maronites’ anti-Jacobin counterrevolutionary credentials, Murad recorded a history of Lebanon in which the Shihabs ranked first, followed by other Christian notable families. The Druzes were left on the margins of the narrative: Murad argued they were outsiders who had been attracted to Christian Mount Lebanon and were given the title of shaykhs because of services they had rendered to the Shihabs. Moreover, the Druzes professed “idolatry,” and, even more, they signified the unmodern, the “fanatical,” and the lazy: “The Druze is generally lazy and idle; the only work that he engages in is plowing; all crafts [métiers] are unknown to him. With the exception of very few individuals who have frequent or intimate relations with Christians, the Druzes know neither reading nor writing; they could not live without Christians, who to the contrary, are familiar with all the professions exercised in Europe.”[51]

By creating this absolute distinction between Maronite and Druze and by conveniently presenting the Maronites as the original possessors of the land to which the Druzes were latecomers, Murad was not only legitimating the Maronite Church’s position on restoration but was also reworking Maronite identity, casting it in imaginary national sectarian terms that totally excluded the Druzes. Loyal to France and to the Crusaders, loyal to the idea and existence of Christianity in the Orient, and on the front line between Christendom and barbarism, Murad’s Maronites urgently needed French assistance in the troubled postrestoration times. “Lebanon,” he wrote, is “like another French land,” and France was the “seconde patrie des Maronites.”[52] To add scientific evidence to his various arguments, Murad concluded his narrative with appendices that explain the “genealogy of the [Christian] Princes of Lebanon” and that enumerated the different populations of Mount Lebanon in which the Maronites, of course, constituted the overwhelming majority.

Murad’s fabrications per se are not important; the implications surrounding them are. The text was modern in that it framed Murad’s appeal as part of a wider struggle of a modern, progressive, and united Christianity against a barbarous Islam. But more than that, the narrative form of the document, with its appendices and genealogies, ruled out any margin of error. The truths Murad presented were as stark and evident to his mind as the existence of a pure and Catholic Maronite tradition. Moreover, he interpreted the sectarian violence of the 1840s as part of a wider Muslim plot to destroy Christianity in the Holy Land, and he perceived the Druzes as the agents of this diabolical scheme. While he stressed the unbridgeable temporal and sacred distance between the Maronites as modern Catholics and the Druze as uncivilized “infidels,” Murad was at pains to portray the Maronites as not just pro-French but actually French people living in a specific territory known as the Mountain Refuge.[53]

Murad’s use of the term ahali signified the ambiguity in the partitioned landscape. On the one hand, the term ahali retained its old-regime connotation of belonging to the nonelite, and with its continued use in this sense—for example, in Ottoman reports—the old-regime social order was constantly reaffirmed. On the other hand, another, more equivocal connotation of the term arose in which the ahali became synonymous with the “people” of a nation. Thus, when Murad referred to himself as the “general representative of the Christian people” or when the Maronite Patriarch referred to the ahali, they were marking a political boundary between Maronites and non-Maronites in addition to a social boundary between notables and commoners. Yet for all its evocation of a Maronite nation, Murad’s vision was not a populist one. It was an elitist narration that claimed to speak for all Maronites. The idea of community was no longer an elite one that crossed religious boundaries but one that was entirely subsumed within the religious community. Yet like the söz sahibleri of the old regime, the representatives of the new sectarian vision were still elites. Murad’s goal was not to reform the social order of Mount Lebanon but to stamp a Christian identity on that order. Herein lies the central problem of his vision: how to reconcile a communal vision of Mount Lebanon and maintain the old-regime social order.

This was precisely the task that the new Ottoman foreign minister, Şekib Efendi, gave himself when he was ordered to Mount Lebanon in 1845 to pacify the province following another bout of intercommunal violence. To a large extent, Şekib Efendi personified the contradictions of the Tanzimat, for he tried to reimpose absolute Ottoman sovereignty while recognizing the limits of Ottoman power. He promoted an official Ottoman nationalism in an effort to contain sectarian mobilizations, but he was unwilling to countenance any interpretation of the Tanzimat that gave the local subjects an autonomous voice. In short, he was aware of the pressure from Europe that motivated Ottoman reform, but he categorically refused to accept that this pressure forced the Ottoman authorities to alter their relationship to imperial subjects. Ottoman officials were willing to concede that they should treat Maronites and Druzes equally (which, effectively, had been the case during the old regime), but they did not take this to mean that they should relate to them differently: as center to periphery and as Ottoman to rural.

Şekib Efendi’s vision of a new sectarian order, known as the Règlement of Şekib Efendi, was based on the notion of an “ancient” rivalry between two distinct sides.[54] Because he was convinced that the Druzes had been oppressive “for a long time [kadimdenberu],” Şekib Efendi felt that the Christians of the mixed districts would never willingly accept the reimposition of Druze rule. In his judgment, the only solution short of a population transfer, which he rejected, lay in the creation of an intricate system of sectarian checks and balances. He reconfirmed the kaymakams in their respective positions, but he created for each district an administrative council which included a judge and an advisor for each of the Maronite, Druze, Sunni, Greek Orthodox, and Greek Catholic sects.[55] Although these councils encroached on the traditional autonomy of the muqata‘jis, Şekib Efendi nevertheless reconfirmed the notables in their responsibility to maintain law and order.[56] The Ottoman foreign minister stipulated that wherever the notables and the population were of different “race” and “sect,” a wakil, or representative of the same “race” of the population, would be appointed to oversee the administration of the notable.[57] When two people of the same “race” and “sect” (hemcins ve hemmezheb) were involved in a petty dispute and they were of the same sect as the notable, then that notable would adjudicate; if they were of the wakil’s sect, then the wakil would settle the dispute; however, if it was a mixed dispute, then the wakil and the notable would work together, and if they couldn’t agree, then they would submit it to their respective kaymakams of the same sect (hemmillet). If they still couldn’t agree, then the Ottoman governor of the Sayda would have the final word.[58]

Among Şekib’s first acts was to summon both Druze and Maronite notables to underscore the importance of the immediate restoration of tranquillity. Despite admonishing them for following the “path of vagabondage,” Şekib reminded the local notables that they were “men of intelligence [eshab-ı ukul]” and hence obligated to join together to restore peace and security.[59] Şekib Efendi deployed the language of the Tanzimat—compatriotism and equality—to evoke the idea of belonging to a single nation, but he also reminded the local notables that they had little choice but to obey his commands. They must submit or be subjected “to all kinds of affliction and harm and all kinds of punishment and retribution.”[60]

Such threats notwithstanding, a basic tension plagued Şekib Efendi’s proposal. Although he described the notables as compatriots in a common land (vatandaşlar), his regulations reinforced the idea of sectarian division by creating parallel governments. The French consul Bourée noted this contradiction when he confessed that the solutions proffered by the Sublime Porte amounted to the “organization of civil war.”[61] Şekib Efendi urged the notables to display their zeal for the nation, but he clipped their wings by creating a massively complicated sectarian wakil system. He gave the ahali hope of representation, but he insisted that wakils come “from respectable households” and work toward preserving a social order in which commoners again submitted to their traditional notables.[62] Şekib Efendi hinted at the possibility of a free, equal, and modern Ottoman subject who was meant to have faith in, and owe loyalty to, an abstract Ottoman nation. Yet his belief in the primordial religious passions of the local inhabitants and his own commitment to social hierarchy, in which all members of the nation knew their proper place, ensured that they could express their belonging to the Ottoman nation only as members of segregated sectarian and social communities. As sincerely as he desired to “see that Druzes and Maronites are treated equally,” he succeeded only in legitimating two separate sectarian political communities.[63] Because Şekib Efendi conflated hemcins, hemmillet, and hemmezheb, he bolstered the idea that religion and ethnicity were one and the same in Mount Lebanon—unchangeable, irreducible, and therefore inevitably at the heart of any project of reform. And although Şekib Efendi recognized the newness of his own legislation, he developed it in accordance with his perception of a primitive sectarian landscape.

Emblematic of the tension between old and new that gnawed at the coherence of Şekib Efendi’s vision was his decision to force the notables to sign and accept a peace treaty based on the principle of mada ma mada, “to let bygones be bygones.”[64] This familiar rhetorical device discursively abolished the memory of transgression and underscored the Ottoman desire to restore an allegedly traditional status quo ante of political sectarian harmony under benevolent Ottoman rule. It recalled the infallible imperial domain of obedience outside the strictures of historical time, and yet it was linked to a project steeped in the new language of the Tanzimat, of equality, progress, and reform. The elites were rehabilitated in the eyes of the state, and the ahali were urged to tend to their traditional affairs of providing taxes and working the land under the uneasy control of their notables. With his work done, an exhausted but contented Şekib Efendi returned to Istanbul, leaving Mount Lebanon to sort out the contradictions of his new sectarian order.

The truth of the matter was that the simple explanations offered by Ottoman statesmen for the communal troubles—their references to European plotting that encouraged a primitive conflict—masked complex realities that undercut even their most sincere efforts at reform. Even as Şekib Efendi worked to enmesh sectarian identity within a series of overlapping and mutually reinforcing administrative arrangements, the theoretical framework of absolute Ottoman sovereignty and the concomitant notion of total Ottoman power on which his entire system depended were being steadily eroded. Not only were Ottoman officials plagued by a chronic financial crisis that left soldiers’ payments in arrears for months on end, but they were frustrated by the ability of the local inhabitants to circumvent their authority.

An incident in October 1845 indicated the gray area of an emerging sectarian politics that tested the boundaries of legitimacy and sovereignty in Mount Lebanon. Ottoman soldiers arrived in the coastal town of Juniya in the district of Kisrawan to disarm what they considered to be its violence-prone ahali. At daybreak a few days later, they entered and cordoned off the nearby towns of Zuq Mikayil and Zuq Musbah. The commanding officer, mirliva (major-general) Ibrahim, ordered all the villagers to assemble and had the disarmament orders read out to the population. The troops began to search the village and to round up those who had not heard the reading of the orders. By chance a major by the name of Haşim Ağa came across “a zimmi (dhimmi, non-Muslim) on horseback dressed in civilian clothes.” When Haşim Ağa ordered the Christian—who remains without name in the document—to appear before mirliva Ibrahim, the Christian “with violence and rudeness” refused and promptly escaped.[65] Immediately thereafter, on another street an officer named Salih Ağa happened on the same Christian and tried once more to “politely” summon the Christian to mirliva Ibrahim by calling out to him, “You there! Go listen to the decree.” This time the Christian allegedly began to incite the people with gestures of his hand, at which Salih Ağa ordered the Christian forcibly dismounted and escorted him to the mirliva.[66]

When the Christian was brought before mirliva Ibrahim, he was asked why he had not come to listen to the decree. “I am from Beirut,” he answered with “rudeness and harshness [şiddet ve huşunet],” and again he had the “fanciful” idea of escaping and began pushing his guards; the report states that “to make an example of him for the others, a few lashes of the whip were administered to him and he was thrown in prison.”[67] Until this point, the story recounts an encounter between representatives of the Ottoman state and a local inhabitant who had violated the limits of old-regime subjecthood. Not only did the term zimmi belong to a classification of Ottoman subjects supposedly superseded by the Tanzimat, but the forcible removal of the recalcitrant zimmi from his horse restored a sense of Ottoman propriety and order.

However, much to the chagrin of the officer writing the report, this wretched zimmi resisted the authority of the Ottoman state. When the Christian was imprisoned by the Ottoman soldiers, he informed his sentries that “I am the brother of the dragoman of the French consul” and claimed to be a subject of the French state. The sentries reported this to the mirliva, who summoned the prisoner and, with slightly more trepidation than before, asked him why he was traveling in these parts. The Christian “made it seem as if” he had come to buy some silk. The mirliva then asked him “if it were not more appropriate for you to buy silk in Beirut, especially since everybody else knows that it was not permitted to come here at this time, and thus your being here is very inappropriate.” The Christian responded by saying only that “I am the brother of the French [consul’s] dragoman and I can come and go here as I please and nobody can stand in my way.”[68]

When the French consul was informed of this incident, he demanded that the Christian be released at once; the Ottomans hesitated to comply, and so the consul wasted little time in ordering one of the French frigates off Beirut to proceed immediately to Juniya.[69] The prisoner was duly released to the “rude and shameless [edepsizlik eylemekleri]” French.[70] The tables were turned; the humiliated Ottoman officers were forced to acknowledge that in sectarian Mount Lebanon, the old forms of coercion and obedience could no longer be deployed without resistance—that they now coexisted with new forms of authority and identity that emerged from the interstices of local identity and international diplomacy. In an era dominated by the European powers on cultural, economic, and military levels, the channels of power flowed not just unilaterally from Istanbul but to and from European capitals.

| • | • | • |

Embracing “Progress”

Perhaps the greatest symbol of the new sectarian climate was the consolidation of the missionary movement in its “mountain refuge.” By their own admission, foreign missionaries were well positioned to take advantage of the political and military upheavals of the Egyptian occupation and the subsequent era of reform.[71] They presented their own sectarian vision of Mount Lebanon, which entirely bypassed the political exigencies and compromises that consumed Şekib Efendi. Unarmed Jesuit and Protestant missionaries possessed an enormous advantage over Ottoman officials, for they were at the vanguard of a cultural movement that allowed for a two-way exchange. They provided the elites with seemingly viable and modern sectarian paths of development. They cultivated them as modern leaders of their sectarian communities and offered them the support and protection of Europe.[72] In return, the local elites protected and gave land to the missionaries. The söz sahibleri encouraged the secular aspects of missionary work, which in turn prompted the missionaries to persist in their ultimate goal of reconstituting a Christian hierarchy amenable to spiritual reform.

Despite the fact that the missionaries incessantly complained of the degradation and corruption of local Christianity and despite their constant references to the imminent peril posed by Islam, Jesuit and American missionaries found themselves completely free to begin their task of “civilization.” The Jesuits, for example, astutely took advantage of their friendly relations with several Egyptian generals, and after the generals were expelled in 1840, the Jesuits capitalized on the prevailing Ottoman disinterest in rural Syria. As long as they did not proselytize among the Muslims of Syria, they found their work unhampered.[73] In Zahla, for example, Planchet confessed from the outset of the mission that “for us, Europeans, we live here in total independence of local government, and have complete liberty to carry on with our sacred ministry, particularly in Mount Lebanon, whose population is, in large part, Catholic.”[74]

The ability of the Jesuits and, indeed, all other missionaries to function with such freedom was facilitated by their self-cultivated image as shepherds of secular modernity. As much as the Jesuits and the Protestants denounced and competed with each other, they understood full well that they shared common technologies over which they both claimed to be masters. A Jesuit missionary, Edouard Billotet, complained in 1857 that the Jesuits were losing ground to the Protestants in Sayda because “their science, their polite manners and above all their charitable use of medicine are popular with the Christians of this town.…We can force them out entirely if we could present to the people a devoted and charitable doctor.”[75] From the outset of their mission, the Jesuits confessed that “we find in [medicine] an easy, perhaps even unique, method to introduce ourselves to the Muslims and the Druze.” Accordingly they spent several hours each day studying basic medicine.[76] The physician Henze was particularly valuable, and many of the important Druze and Christian notables in the land called on his services.[77] Even the Maronite Patriarch asked the Jesuit missionary Paul Riccadonna to intercede with Rome to send more men like Henze, whose knowledge and power of healing were well appreciated.[78]

Certainly, the missionaries’ deployment of modern medicine was intended to aid in the overall spiritual salvation of the local population. But it was also undeniably an integral part of what James Axtell has likened to an “invasion within.”[79] The focus of the Jesuits, for example, was no longer educating a few Lebanese in the Maronite College in Rome. The purpose of the College had been largely achieved: it had successfully “reformed” the Maronite Church and had Latinized it to a large degree. In the nineteenth century, the Jesuits’ goal was far more ambitious and far more complex, for they aimed to “regenerate” an entire population primarily through the medium of local education. At the same time as they fended off Protestant encroachment on their terre sainte, the Jesuits did not want to “denature” the native, to make him desire Europe so much that it would alienate him linguistically and culturally. Instead they sought to reform him sufficiently so that he would be content with life in the Orient. To that end, schools and colleges had to be formed and maintained in the Orient.[80] To both Protestant and Catholic missionaries, spiritual and temporal modernization were one and the same thing. In the eyes of priests like Riccadonna and pastors like Henry Harris Jessup, the native lack of moral and religious constitution was reflected in the status of local women and in the absence of modern (Western) furniture, education, medicine, and knowledge.[81] To remedy this deficiency, the missionaries unleashed, in their own words, a cultural assault on the corrupt traditions of Mount Lebanon.

Although it is difficult to gauge the immediate results of the Jesuits and the American missionaries in this regard, for the work was perforce generational, over the thirty-year period between 1830 and 1860, substantial changes were effected. Forks and knives were introduced, print technology increased, and the use of European and American furniture became more widespread. William Benton, an American stationed in Bhamdun, reported that “civilization enters [Lebanese] habitations in the form of chairs, tables, etc.”[82] The most obvious sign of change, however, was the spread of mission schools across Syria.[83] As early as 1834, the Americans opened a girls’ school; the Lazarists reopened ‘Ayntura in the same year and took over several monasteries across Mount Lebanon, including one in Rayfun. The Americans then set up a secondary school in ‘Abay in 1843, and three years later the Jesuits established their famous seminary in Ghazir, on land purchased from a Shihab emir.

Missionary schools were the most active sites of reform. Initially, the education the Jesuit missionaries provided was ecclesiastical in nature or at least heavily ecclesiastical in form, with religious services and sermons, retreats, and catechisms taking up large parts of the school day. The Americans, too, at first directed an ecclesiastical assault on the local Christian communities. They distributed tracts and polemics in a vain attempt to convince the “nominal” Christians of Syria of their intellectual and spiritual degradation. But the emirs and the elites sought a secular rather than an ecclesiastical education, and neither Jesuits nor Protestants could ignore this demand if they indeed desired to maintain a credible presence on the land. The missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, therefore, abandoned their futile effort at open assault and instead concentrated on opening schools that catered to native demand.[84] Not to be outdone, the Jesuits reacted by admitting into their seminary in Ghazir students whose parents wanted only an “education for the world.” One Jesuit priest lamented that “we are faced with a fait accompli.”[85]

There is great irony, of course, in the fact that local desire for secular modern knowledge (as opposed to ecclesiastical or evangelical knowledge) was controlled largely by missionaries, and hence that knowledge was disseminated along sectarian lines. In this respect, missionaries played as crucial a part in sectarianizing the landscape of Mount Lebanon as did European and Ottoman diplomats and local elites. The bitter rivalry between Protestant and Catholic missionaries played itself out across a shadow partition of Mount Lebanon that presaged and then blossomed alongside the formal partition of 1842. Early American polemics against the “papism” and “ignorance” of the Maronite clergy heightened the clergy’s ecclesiastical consciousness, and the celebrated conversion of the Maronite As‘ad al-Shidyaq (Tannus al-Shidyaq’s brother) to Protestantism in the late 1820s prompted the Maronite Church to prohibit all contact with the Protestants.[86] Moreover, Jesuits aggressively staked their claims to the Catholic inhabitants of the region, especially in and around Kisrawan, while Protestant missionaries focused on the more heterogeneous Druze-dominated Shuf.

Neither side explicitly acknowledged the hegemony of the other, and yet a modus vivendi was established. The American missionaries came to rely on the local protection of the Druze notables and the formal protection of the British consul, while Druze notables understood that the American missionaries were a conduit to British power. Indeed, the missionaries of the American Board made little effort to dispel the notion among the Druze notables that they were connected to imperial power. “[The Druzes] appear to have the most entire confidence in our missionaries,” confided Benton while stationed in the village of Bhamdun, “and say if they were not Druzes they would be English Protestants. We are often confounded with the English, and known as Americans, often do not attempt to disabuse the minds of these mountaineers of this mistake. Many of them have no conception of geography.”[87] The Jesuits, however, looked to the Maronite authorities and French consulate for backing, and the Maronite Patriarch readily grasped the importance of the Jesuits as a connection to Catholic Europe. Finally, in the absence of any Ottoman interest in the general education of its rural subjects, Druze and Maronite elites turned to the missionaries to provide a modern education for their children. Druzes, by and large, sent their children to Protestant schools and accepted an implicit orientation toward Britain, whereas Maronites embraced the Jesuit schools and thereby committed themselves to an explicit orientation toward France. Modern education did not stem from, and hence reinforce, a religiously integrative social order but reflected, and gave credence to, a religiously segregated landscape.

Nowhere was the attempt to disengage from traditional society more evident than in the Jesuit schools. Because missionaries like Riccadonna and Louis Abougit believed that native Christians were corrupted by their neighborliness with Muslim and Druze villagers, they envisioned pure Christian spaces to be indispensable for reform. Riccadonna expressed his revulsion at the intermingling of Muslim and Christian, at the Christians’ practice of adopting Muslim names, and at their habitual invocation of the prophet Muhammad, while Abougit was scandalized by what passed for normal behavior in Sayda:

We are sorry to say that there was a sort of coexistence [fusion] between the Christians and Muslims of Sayda. They visited each other frequently, which resulted in intimate relations between them and which introduced, bit by bit, a community of ideas and habits all of which was at the expense of the Christians. These latter joined in the important Muslim feasts, and the Muslims [in turn] joined in the Christian feasts; this kind of activity passed for good manners, sociability, while in truth it resulted in nothing more than the weakening of religious sentiments.[88]

In seminaries like Ghazir the most invidious work of a new sectarian outlook took its slow course. There native students became deeply involved with the passions and experiences of Occidental Christianity and European history. Jesuit priests sheltered them from their indigenous surroundings and inculcated in them the order of counterrevolutionary modernity. The students were taught to respect Catholic France and, implicitly, to disdain their immediate surroundings. They were made to submit to a new hierarchy that began not in the rural village but in the Jesuit school and that ended not with the Sultan in Istanbul but with the Pope in Rome.

From their enclaves of “pure” Occidental Christianity, the Jesuits penetrated the home and the family. In 1859, a Jesuit priest who accompanied several French noblemen to Ghazir reported, much to his satisfaction, that the students were well advanced in the gentle crusade. At the entrance to the village, the students of the college received him and his traveling companions with cries “a thousand times repeated” of “Long live the French pilgrims!” Astonished by this reception, the visitors were moved by the melange of students, of Greeks, Maronites, Arabs, and Armenians, united “in a single thought of love for those whom they hailed as the representatives of France.”[89]

Later at dinner, the students several times toasted the honor of France, and afterward the visitors were regaled by the sounds of civilized native tongues that expounded on a “new order of things.” Several of the brightest students took turns explaining to the visitors the history of the school, the curriculum, and the goals of a “modern” education. They began by explaining the importance of situating a school in the Orient and not in Europe, for, as one of the students explained with pride, “With God’s help, you will give us the science and the piety of the clergy of Europe. You will initiate us into civilization, enough to enhance the influence of our ministry before our compatriots, but not enough to make us abandon the simple patriarchal life of our country. Salut, Ghazir, haven of our youth! . . . Salut, brilliant aurora, precursor of more beautiful days. Salut!” Then another student rose and described how the notion of progress had been inculcated into the student body, how Europe had been represented, and how “debased” the stagnant Orient would remain without European aid and civilization. Even the Muslims would have to bow before the imperatives of time and modernity, as “their contact with the civilized peoples inspires amongst many of them a desire for progress which raises them to the level of European nations.” New linear notions of time had not only been taught to the students but had been imbibed by them. After a break for refreshments, served by the “Arab” students, the visitors were once more entertained. With the “terror” of 1848 behind them, explained a third student, the Jesuits courted the elites of the country, whose sons would one day be called to rule, and provided them with what they desired, an education for a changing world. Finally, a student from the notable Maronite Hubaysh family summed up the moral of the story, extolling the virtues of France: “Thanks to your influence, thanks to the noble zeal of French hearts, the seminary at Ghazir will live. The tree of faith, that of civilization, will grow in our land scorched by the sun of Asia; the Greek, Armenian, Maronite and Syrian nations will rest in the shade of its branches, and the leaders and old men of the country, the object of your solicitude, will recount to the new generations the kindness of France.”[90]

These products of a Jesuit education reflected with pride on their sense of accomplishment. While they had once been merely the sons of powerful families, they were now “civilized” sons of powerful families. From now on, the reality of the “new order of things” was stamped on their young minds. Without France, there was aridity. Without some level of (but not too much) “civilization,” there was sterility. Without the Jesuit fathers, there was an emptiness, a void that could no longer be filled by the suddenly small, suddenly uncivilized traditions and customs of their culture. Best of all, the students informed their illustrious visitors that although Ghazir had once boasted a mosque, now it had vanished—“stones and Muslims, have altogether disappeared.”[91] Jesuit Ghazir exemplified how a notion of historical progress embedded itself within a reworked sense of a sectarian community. In Ghazir an understanding of an organic past that nurtured the present was abandoned wholesale; the barrenness of local traditions was accepted as fact by the students. By severing themselves completely from their indigenous past, by making it foreign, and by embracing the Jesuits as community, Riccadonna’s Maronite disciples willingly subordinated themselves to a sectarian modernity. They adopted Jesuit manners and language, most often French but also Italian; they believed that their tie to Catholic Europe was umbilical; and they exhibited a newly instilled fear of and a willingness to be segregated from their Islamic surroundings.

| • | • | • |

Segregated Communities

No single elite group sectarianized Mount Lebanon, but each contributed to the dismantling of the moral and material foundations of the old regime. Under the historical, geographical, and cultural recasting of Mount Lebanon as a quintessentially sectarian land lay an unresolved crisis. The traditional elite community of knowledge that had bound chroniclers, clergy, and notables of different faiths together in a nonsectarian politics during the old regime had disintegrated under the pressures of reform and was in the process of being reconstituted as separate sectarian communities of knowledge. The entrance of Europeans as players in elite politics; rival Druze and Maronite interpretations of the meaning of legitimacy, tradition, and reform; and missionary encroachment dramatically altered the relationship among religion, knowledge, and power. Whereas religion had once been an integral part of an elaborate nonsectarian social order dependent on a notion of absolute and everlasting Ottoman sovereignty, it now constituted the basis and raison d’être for communal segregation in an era of profound change. Paralleling the two geographical districts that divided Mount Lebanon were opposing Druze and Maronite reflections of a putative past—and what morals and lessons should be drawn from it—and mutually exclusive visions of a sectarian future. Reform had come to Mount Lebanon Janus-faced. One side looked backward to survey the allegedly primordial scene, while the other side looked forward to shape a diverse land into a tragic place of atavistic hatreds and primordial religious solidarities.

There were some notable victories for sectarian modernity. By 1860, for example, Riccadonna believed he had made local Christians worthy again of that name, for he had stopped (some) Christians from singing “Muslim” songs.[92] By 1860, missionaries had done much to transform previously “unrecognizable” Christian women into discernibly “modest” Christians.[93] Father François Badour had even noted in 1855 that new Catholics were being born in the Levant, at once loyal to France and able to withstand the “pernicious influences of the community of infidels with whom they are mixed.”[94] But from other vantage points anxieties snapped at the heels of these victories. The breakdown of the old regime had opened a Pandora’s box of possibilities regarding the political and social makeup of each community. Rival elites—the Maronite Church, secular Christian and Druze notables, Jesuits, European and Ottoman officials—struggled to impose their respective visions of a sectarian Mount Lebanon. They tried to preserve the social hierarchy of the old regime while they undermined its material and metaphorical foundations. They insisted that their religious communities were autonomous political and cultural nations and not simply communities of faith integrated into a complex intrareligious polity.

Never for a moment did the disparate elites contemplate the full ramifications of reconfiguring each ta’ifa as a nation. Their grim determination not to relinquish any power and their successful efforts to block cadastral reform in the late 1840s notwithstanding, at times it seemed that notables like Khattar al-‘Imad, whom we came across earlier in this chapter, were beginning to make out a terrible apparition largely of their own making.[95] As we shall see in the next chapter, one unintended result of the elite debate over reform was the theoretical possibility of a subaltern ahali who would forcibly stake out a role in politics and claim a place in a sectarian landscape. Fear and rejection of this possibility increasingly burdened and complicated elite narratives and rivalries up to and including 1860. The rupture in the cohesiveness of the traditional politics of notability and the introduction of communally articulated reform muddled the status of the ahali. ‘Imad’s supplication to the Ottoman government summed up the conundrum. He claimed the Christian villagers in his district “were once our miserable and wretched subjects.” Left hanging, however, was a palpable concern. What were they to become now? In other words, what was the place of the ahali in an emerging sectarian world? How was the Ottoman government to reconcile its secular intent with the renewed emphasis in Mount Lebanon on sectarian affiliations? And did the Tanzimat imply social as well as religious equality? Precisely because no single party had a monopoly on interpretation in the era of reform, there was no way of answering these questions categorically or uniformly.

In a period of dominance without hegemony, to borrow Ranajit Guha’s formulation, the door was unwittingly left open for the uncontrolled entrance of the ahali onto the sectarian political stage.[96] And as we shall presently see, there was a commoner daring enough to walk through it. The rise of Tanyus Shahin embodied a popular sectarian invasion of what had once been the strictly elite realm of politics. This muleteer from Rayfun represented the most radical attempt to redefine the relationship between power and knowledge in the history of Mount Lebanon. In so doing, he unleashed a sustained terror among the elites.

Notes

1. E. J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). Invention does not signify outright falsification.

2. HPD/Third Series/vol. LXIII/14 June 1842, p. 1515.

3. HPD/Third Series/vol. LXIII/16 June 1842, p. 1608. Lord Aberdeen’s reply to Lord Howden was that Britain would not neglect its duty toward the whole population of Syria, “but particularly [toward] the Christian population.”

4. Quoted in Urquhart, The Lebanon, 2, p. 397 (emphasis my own).

5. Aberdeen to Canning, 22 December 1841, United Kingdom, House of Commons, “Affairs: Correspondence Relating to the Affairs of Syria,” Parliamentary Papers, 1843, LX, 1.

6. FO 78/476, Canning to Aberdeen, 29 March 1842.

7. AE CPC/B, vol. 3, Bourée to Guizot, 7 February 1842.

8. The omniscient style of the British and French consular and ambassadorial reports reinforced the sense that this was in fact a “proverbial” conflict. In effect, it constituted a disengagement and a refusal of the consuls to accept any responsibility for what was taking place. Thus, the distribution of inordinate amounts of weapons, the various and often conflicting promises made by Wood to the rival elites, the politics of a restoration sponsored to a large extent by Britain, and the European insistence that the Ottomans remain in only indirect control were reduced to “trivial” causes of an otherwise smoldering primordial struggle. The fact that the Ottomans had reacted to the sectarian violence by deposing Bashir Qasim and appointing a Croat Ottoman officer, Ömer Pasha, in 1842 incensed the European powers even more.

9. Salibi, The Modern History of Lebanon, pp. 55–56. See also Marsot, Egypt in the Reign of Muhammad ‘Ali, p. 245, and HLAJ/1, p. 573.

10. HLAJ/1, Planchet to Roothaan, 7 December 1841, p. 321.

11. HLAJ/1, Planchet to Roothaan, 15 January 1842, p. 326.

12. Canning to Aberdeen, 15 February 1843, United Kingdom, Foreign Office, “Correspondence between Great Britain and Turkey Respecting the Affairs of Syria 1843–1845,” British and Foreign State Papers, 1847–1848, vol. 36 (London, 1861), p. 7. See also Bourqueney’s note to the Sublime Porte, BBA IMM 1135, Leff. 3, 11 January 1843.

13. Canning to Rose, 29 August 1843, British and Foreign State Papers, 1847–1848, vol. 36, p. 18. See also FO 78/473, Foreign Office dispatch to Canning, 16 March 1842, which stated in regard to temporary direct administration, “Her Majesty’s Government are not prepared to say that the Porte was not justified in assuming direct rule over the whole of Mount Lebanon.” The French ambassador to the Porte, Bourqueney, admitted that “le rétablissement de la tranquilité est incontestable: les vraisemblances sont de notre coté”; AE CP/T, vol. 286, Bourqueney to Guizot, 6 June 1842.

14. Canning to Rose, 29 August, 1843, British and Foreign State Papers, 1847–1848, vol. 36, p. 18.

15. FO 78/476, Canning to Aberdeen, 27 March 1842.

16. “Taifeteyn-i mezkureteyn kemal-i mefsedet ve habasetle mecbul bir kavm-ı müstehak-ül-levm oldukları–an.” BBA IMM 1129, Leff. 14, 7 B 1258 [14 August 1842].

17. BBA IMM 1115, Leff. 8, 27 B 1258 [3 September 1842].

18. “Berriyetüşşam ahalisi beyninde Arnaudlar gibi kan davası pek büyük olduğundan mumaileyh muktazi-i cinsiyet böylece hareket eylemiş.” BBA IMM 2154, Leff. 17, 2 L 1257 [16 November 1841].

19. The Ottomans sided with neither Druzes nor Maronites but dismissed them equally as troublesome barbarians. Contrary to a widely believed myth of Lebanese nationalist historiography, the Ottomans were not concerned with stripping Mount Lebanon of its “independence.” However, as indicated in numerous reports, when confronted with a crisis, the authorities used whatever means were necessary to reestablish order. See BBA IMM 1129, Leff. 12, 7 B 1258 [14 August 1842].

20. BBA IMM 1135, Leff. 18, 9 L 1258 [12 November 1842], and BBA IMM 1129, Leff. 14, 7 B 1258 [14 August 1842].

21. Takvim-i Vekayi, no.267, 26 Za 1257 [8 January 1842] (Istanbul Universitesi Kütüphanesi/407).

22. AE CPC/B, vol. 3, Bourée to Guizot, 18 January 1842.

23. In the era of the Tanzimat, the central authorities were still hampered by their ignorance of the local populations. With the possible exception of the mission of Selim Bey, a commissioner sent by the Sublime Porte to inquire into the feelings of the ahali toward Ömer Pasha’s administration (which the European ambassadors rejected out of hand for being an entirely coercive undertaking), there was no comprehensive knowledge, no ethnography of any kind, no travelers’ reports they could rely on to inform them of the “customs and manners” of the rural population. For more information on Selim Bey’s mission, see BBA IMM 1124, Leff. 3, 9 B 1258 [16 August 1842]. Even in his introduction to Tarih-i Lütfi, Abdurrahman Şeref confuses the etymology of the word khuri (priest) with huri (virgins of paradise). Lütfi, Tarih-i Lütfi, 8, p. 33.