5. Afterword

The caution with which I began, reminding myself and my readers, was that writing serves a society in many complex ways. That writing signs was a practice of ruling persons and groups in societies for a long time. That the Fatimid phenomenon needed to be seen in the full context of the uses of writing signs among Christian, Jewish, and other Muslim groups in the eastern Mediterranean. That the Fatimid writing of signs, of making a public text, was unique. Stated either way, my intention was to confront two notions: that only Muslim rulers used officially sponsored writing, and that all Muslim rulers used it in the same way. That is why so much of this study has focused on explicating the conditions that supported, the people who sponsored, and the audiences who saw the written signs in the years of Fatimid rule.

Beyond this in-depth discussion and analysis of the signs the Fatimids wrote—those public texts that were raised—we can weigh the Fatimid achievement by a brief record of how long it endured, especially in the Cairene area its signs dominated. In very real ways Fatimid practice became part of the Cairene tradition of writing signs. For at least the next two centuries, Ayyubid (1171–1250/567–648) and Baḥrī Mamluk (1250–1389/648–791) military rulers used public texts in specific locations in ways similar to those of the Fatimid wazīrs before them. If we consider the social uses that the military leaders, the wazīrs, made of officially sponsored writing signs during the last decades of Fatimid rule, the continuation of such practices is almost predictable. The termination of support for the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Caliph did not alter many of the social conditions in which the practices of writing signs were embedded. The first of the Ayyubid dynasty to rule in Egypt, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb (d. 1193/589) was also the last Fatimid wazīr. He became wazīr in 1168/564, Sultan in 1171/567. By this act he accomplished the task of terminating Fatimid rule that several wazīrs before him had considered.[1] He signalled this change as Muslim rulers traditionally did, by having the khutba delivered in Cairo in a new ruler’s name—the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustaḍī’ (r. 1170–80/566–75).

His coins maintained the Fatimid format of concentric circles with lines of writing in the center circle (fig. 43). They also maintained Qur’ān 9:33, which was present on Fatimid coins. But he and the Ayyubid Sultans that followed him maintained this format for only a few decades, as part of the transition to their new rule in Egypt which required economic stability. The Fatimid dinar, format and material, was a known and valued part of international exchange. Once Ayyubid rule was stabilized, the Fatimid concentric circle format was abandoned, and the Umayyad-Abbasid traditional format was again adopted.

Fig. 43a. Dinar, Ṣalāh al-Dīn (1002.1.1027 Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum in the Cabinet of the American Numismatic Society)

Fig. 43b. Dinar, Ṣalāh al-Dīn (1002.1.1027 Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum in the Cabinet of the American Numismatic Society)

Ṣalāh al-Dīn’s use of writing signs is known also from the plaque he placed on the Burg al-Imām at the citadel, a use of public texts on thresholds known for centuries in the eastern Mediterranean.[2] This writing sign displays Ṣalāh al-Dīn’s titles and the year 576 (1180–81), and like the plaque Badr al-Jamālī had displayed on the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn, the writing refers directly to the political circumstances. Ṣalāh al-Dīn is “he who has unified the language of belief and crushed the servants of the Cross [referring to the Crusaders]…who has revived the empire of the [Abbasid] Caliph.” While the referential dimensions of the writing here are equivalent to those found in the later Fatimid period, an aesthetic link with the past is broken. The script style is naskh, a cursive script that breaks the visual link with the writing signs from the Fatimid period. A pedestrian can readily link this writing style with the other inscriptions of the new ruler and rule—for example, the foundation inscription at the citadel, recording its construction, under the order of Ṣalāh al-Dīn and his wazīr Qarāqaush in 579 (1183–84).[3]

Later Ayyubid and then Baḥrī Mamluk rulers changed the script style of their writing signs, but they maintained a reference base equivalent to those of the Fatimid wazīrs before them. The placement of Ayyubid and then Mamluk public texts, both on the facades of Muslim communal structures, and the location of these structures in the Cairo urban area, play visually and semantically with those of existing Fatimid texts.

Four sites formed the topography of rule in the Fatimid period: the Bayn al-Qasrayn—the palaces flanking it and the al-Aqmar mosque; the Anwar or al-Ḥākim mosque at the Bāb al-Futūḥ; the muṣalla at the Bāb al-Naṣr; and the al-Azhar mosque (map 3).[4] The Ayyubid and then the Baḥrī Mamluk rulers maintained three of these sites as part of their own topography of rule—the Bayn al-Qasrayn, and the al-Azhar and al-Ḥākim mosques—but effectively inscribed them within different aesthetic, social, and structural networks. In this manner the sites became historically layered in their associations with rule. One of these sites, the Bayn al-Qasrayn and the two palaces along with the al-Aqmar mosque, is especially relevant here.[5]

The area of the Fatimid palaces and the al-Aqmar mosque remained important in the new hierarchies within both Ayyubid and Mamluk Cairo. The Fatimid palaces may have continued to be inhabited in the early Ayyubid period, but on both sides of the street, complexes were built over and with materials from these demolished palaces. On the east side, the Fatimid Imām’s residence and the mausoleum of the Ismā‘īlī Imāms were replaced by the madrasa and mausoleum complex of Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb,[6] and in the Mamluk period, by the madrasa built by al-Ẓāhir Baybars in 1262.[7] On the west side, the overlay of the Western Palace was completed in the Baḥrī Mamluk period with the construction of the complexes and mausolea of Sultan Qalā’ūn and Sultan al-Nāṣr Muḥammad (map 5).[8] Thus the area remained residential in character, as it had been, but in the Ayyubid and Mamluk times the residents were students, professors, and other functionaries at the great academic, medical, and commemorative structures that shaped the space. The area also remained the burial site of the rulers; Ayyubid and then Mamluk rulers were interred there.

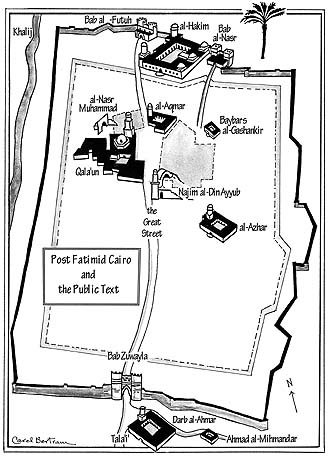

Map 5. Post-Fatimid Cairo (drawn by Carel Bertram)

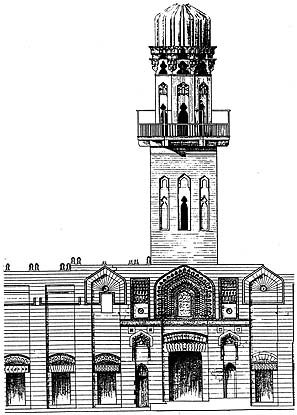

Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb (r. 1240–49/637–47), the last of Ṣalāh al-Dīn’s dynasty to rule, and then Mamluk Sultans Qalā’ūn (r. 1280–90/678–89) and al-Naṣr Muḥammad[9] used public texts on the outside of the complexes they built in this area. In the mid-thirteenth century, Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb built a madrasa on the site of the Eastern Palace, an act that replaced the Fatimid Imāms’ residence and mausolea with a teaching institution for the four Sunni schools of law. After the Sultan’s death, his widow inserted a tomb for her husband into the madrasa by building into the main teaching hall of the Mālikī law school.[10] The facade of the madrasa resonates strongly with that of the mosque of Ṭalā’i‘ located to the south, along the Great Street (map 5), and its entrance portal relates directly to that of the al-Aqmar mosque, almost immediately to the north, on the same side of the Great Street (fig. 44).[11] The band of inscription on the portal displays the names and titles of the Sultan. In the arched hood over the portal, where in the al-Aqmar mosque a large concentric circle medallion is displayed, a plaque with lines of writing displays in a different format the names and titles of the Sultan. Although these public texts on the madrasa share an equivalent evocational base with those on the al-Aqmar mosque and that of Ṭalā’i‘, the naskh script distinguishes them visually from those on the Fatimid structures. At the same time, the naskh script links them with the other Ayyubid public texts in the city.

Within the next five decades, three more major complexes were constructed in this area, two across the street on the site of the Western Palace. On the order of Mamluk Sultans Qalā’ūn and al-Naṣr Muḥammad major madrasa-mausoleum complexes were built on this site.[12] On the facades of both of these complexes the Sultans displayed writing signs in visually prominent bands running the length of the facade (fig. 45).[13] The semantic content of each of the bands is the names and titles of the Sultan. Sultan Qalā’ūn’s titles are especially elaborated twice on the facade of his complex, following the practice on the al-Aqmar mosque. In addition to the usual range of titles, Sultan Qalā’ūn is: “the King of Kings of Arabs and Persians, the Possessor of Two Qiblas, the Killer of Infidels and Polytheists.”

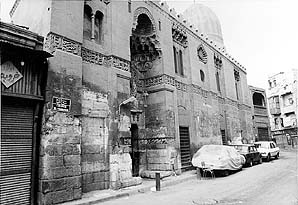

The other complex in this location, the khanqah (dervish lodge) and mausoleum of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir built in 1309, displays public texts similar in form, in placement, and in content to the two Mamluk complexes mentioned above. This khanqah and mausoleum were built over the palace used by the very last Fatimid wazīrs located on the northern side of the Eastern Palace, on the road from the Bāb al-Naṣr (map 5, fig. 46).[14]

Fig. 44. Facade, madrasa of Sultan Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb, after Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, vol. 2

Fig. 45. Facade, madrasa-mausoleum of Sultan Qalā’ūn

Fig. 46. Facade, khanqah-mausoleum of Sultan Baybars al-Gashankir

These Mamluk public texts, in placement on structures, location within the city, and referential base, continue the Fatimid Cairene tradition of using writing signs on Muslim communal structures. However, they were made readily distinguishable from those of both the Fatimid wazīrs and the Ayyubid Sultans by the style of the script, naskh. While naskh script was used by the Ayyubids, the proportions of Mamluk naskh are recognizably different from the Ayyubid writing signs. The upright letters are much taller in relation to the horizontal lines. In addition, the Mamluk writing signs themselves are much larger than those of the Ayyubids.

This practice of displaying public texts created a dense network of texts in the area where the Fatimid palaces were built and where the al-Aqmar mosque was preserved. The addition to the Fatimid base, the Ayyubid, and Mamluk public texts created (and create) a richly textured network of signs. When all these structures were completed, audiences could easily perceive the differences in writing styles. But seeing a hierarchy among those visual differences was a social function, and belongs to the ways each of these structures was inscribed in the social use of the day.[15] How the structure itself was used in the social order, its privilege of place, formed part of the judgment the audiences made when perceiving these writing signs. To the beholder of all these writing signs, medium was a less relevant aesthetic dimension for conveying meaning than it was, for example, in the Dome of the Rock, because all of these inscriptions were in either marble or finely finished stone.

Relevant to this study also is the area of the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque just outside the Bāb Zuwayla. While not important within the topography of Fatimid rule, the Darb al-Aḥmar, the new street running southeast from the Bāb Zuwayla, became the main thoroughfare in the Mamluk period (map 5). It supplanted the extension of the Great Street in importance and along it members of the Mamluk ruling group built communal structures. The importance of this street in the Mamluk period focused attention on the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque.

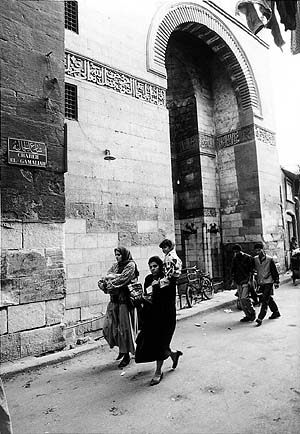

This site lacks the dense association with rule of the Fatimid palace and mosque of al-Aqmar area, but the visual impact of the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque, and the public texts on it, undoubtedly accounts for the Mamluk response in the form of writing signs. The orientation of the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque toward the qibla assures that the main facade of the structure is fully in the view of a pedestrian exiting the Bāb Zuwayla. In addition, the structure gives definition to the street patterns outside this gate. It creates the corner where the Great Street and the Darb al-Aḥmar meet, so that anyone proceeding down either street must pass the full length of one of its facades. The long north side of this mosque creates the beginning of the Darb al-Aḥmar, just as the west facade does for the Great Street. The bands of public texts on the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque were a highly visible feature of the facades (fig. 38).[16] It is not at all surprising, then, that the first mosque built by a Mamluk nearby on the Darb al-Aḥmar responded with the display of public texts in bands (fig. 47). Amīr Aḥmad al-Mihmandar, Sultan al-Naṣr Muḥammad’s chief of protocol, built the first Muslim communal structure on that street in 1325. It was a mosque located on the same side of the Darb al-Aḥmar as the mosque of Ṭalā’i‘, and just shortly beyond it (map 5).[17] As expected, the bands of public text display his name and titles and also provide some indication as to why he was chosen chief of protocol. The text of the inscription is an astute presentation of the Amīr as a good Muslim who works gratefully within the social order under Sultan al-Naṣr Muḥammad. The naskh style of the writing links it visually with those writing signs within the walled city sponsored by the Mamluk Sultans.

Fig. 47. Facade, mosque of Amīr Aḥmad al-Mihmandar

The post-Fatimid Cairo map (map 5) is especially designed to highlight the juxtaposition of the extant structures that display prominent public texts along their facades, and their locations are easy to apprehend. In no other locations within the urban area of Cairo-Miṣr did military leaders use public texts to the same degree of density. This assessment of the practice of writing signs is based, of course, on an examination of extant buildings. Fortunately, numerous buildings of the Mamluk period survive, and provide ample evidence to support this contention, as do the few remaining from the Ayyubid period. Sultan al-Naṣr Muḥammad’s practices of using writing signs are indicative of the more general practice. He displayed public texts along the facade only on the complex he built over the Fatimid palace. No bands of inscriptions articulate the exterior walls of the large mosque he built on the citadel. In other parts of the city, the Mamluks developed a different practice for the display of writing on the exterior.

One element of Fatimid practice, that of displaying writing signs on the interior of Muslim communal structures, was maintained by the succeeding rulers. These writing signs were maintained as the prominent visual sign in the articulation of the interior. This practice was applied to interiors of communal structures throughout the entire urban area, and is readily apparent from any brief survey. In mausolea, like those of Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb, Sultan Qalā’ūn at the Bayn al-Qasrayn, Sultan Hasan at the foot of the citadel, or Imām al-Shāfi‘i in the Qarafa cemetery, writing signs were prominently displayed on the interior. As in the Fatimid period, this practice was applied in mosques and in madrasas in the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods as well. Although in mosques, whether courtyard or iwan (three-sided chamber) style, writing signs were placed most consistently only in the qibla area, and not, as in Fatimid practice, throughout the interior. The reference base of the inscriptions remained primarily the Qur’ān, although, as before, patron information did appear. The style of script used for these writing signs was varied, even within structures, especially in Mamluk practice, again a contrast with Fatimid practice in which writing signs were always presented in a variant of Kufic script.

The intent here is to point to the most salient aspects of the continuation of the Fatimid public text and practices of writing signs. The social uses of officially sponsored writing addressed to a group audience in the Ayyubid, and especially in the Mamluk period where much evidence remains, require their own serious analysis.

In drawing this study to a close, it is useful to bring the continuation of the Fatimid public text into the twentieth century, and to do so requires returning to an issue taken up in the previous chapter. There the issue of the dissolution of form and content was discussed in relation to practices in the later Fatimid period in which the round form of the sign of Isma‘ilism was maintained, but its Ismā‘īlī content dissolved. The dissolution of form and content of the sign of Isma‘ilism was part of the process by which a publicly visible architectural element was appropriated and assigned a new meaning or connotation. Such appropriation is a continuous process in a city, and is linked to a related, but distinct, process in which old forms are a conscious model for new forms. Newly created old forms are used to fabricate a past and make linkages with it.[18] Naturally, here, too, new meanings and new uses are assigned to the old forms. The facade of the al-Aqmar mosque, with its striking format for public texts, is an old form that in the twentieth century has been newly made and appropriated.

Earlier this century, the Coptic community fabricated a new version of the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque, using it as the facade for the new Coptic Museum (fig. 48). The formal aspects of the new facade closely resonate with those of the al-Aqmar mosque (fig. 35): its tripartite division, salient portal, roundel within the portal, and three bands cutting the facade. But the alterations present in the new old form are part of a twentieth-century connotative system that is Cairene, and serve to highlight for us how architectural forms can become modern emblems of the historical past of an urban area.

Fig. 48. Facade, Coptic Museum

The writing on the facade of the museum is in two languages, and is more limited in its display than on the earlier form. In the center of the facade, under the cornice of the salient portal of the museum, the band of writing is in Coptic, alphabet and language. It names the place. On the two side wings, the top band displays writing in Arabic, language and alphabet. It also names and dates the place. The alphabets and languages, as well as their placement on the facade, relate directly to the community, society, and local audience of this museum.

The two other bands, the intermediate one running the full length of the facade, and the third and lowest one running only on the portal, which on the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque were spaces for writing signs, on the facade of the Coptic Museum are filled with geometric designs. The other format for writing on the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque, the concentric circle medallions above the entrance portal and in the niches on the side, is maintained, but not as a space for writing. Instead, on the facade of the Coptic Museum, the center of each circle displays the form of the Coptic cross. For those beholders who visit the museum and cannot read, and perhaps even identify either writing sign, the form of the Coptic cross marks the building as belonging to the Coptic community. There are, of course, many beholders for whom the writing signs are not public texts because they do not recognize the presence of writing. The Coptic Museum is visited by many foreign tours yearly.

The relationship of the new old form of the facade of this museum to its surrounding area provides a confirmation in the twentieth century of the contention of this study, namely, that Fatimid practice of the public text was different in its day from the traditional practice of writing signs. The Coptic Museum is located in what today is known as Miṣr al-Qāḍīmah (old Miṣr), or Fusṭāṭ, to use the other medieval term, just south of the mosque of ‘Amr. The imposition of this new version of the al-Aqmar facade in the oldest part of the Cairo urban area juxtaposes the form for the display of Fatimid public texts to the facades of medieval Coptic churches, the mosque of ‘Amr, and the synagogue which neighbor it.[19] No writing signs appear on the exterior of those Muslim, Jewish, or Christian sectarian structures. The only building belonging to the Coptic community in this area that displays public texts is the facade of the museum, which displays those texts in the framework of the old Fatimid form. In this juxtaposition, this new old form is the thread connecting the modern beholder to other parts of the city and to Fatimid practices of writing signs.

I end with a line perhaps familiar to all who see writing signs everywhere: “The waterskater, that is an insect and dumb, traces the name of God on the surface of ponds—or so the Arabians say” (J. M. Coetzee, Foe). Taking a cue from a passage from the same author cited in my Preface, I could add that this tracery is endless.

Notes

1. Al-Maqrīzī states that Riḍwān, the Sunni wazīr of Imām-Caliph al-Ḥāfiẓ, considered overthrowing him. Itti‘āẓ 3:142.

2. CIA, Egypte, vol. 1, appendix, 726–27; MAE, vol. 2, plate 7c.

3. CIA, Egypte 1:80–85. MAE, vol. 2, fig. 15 shows the location of the inscriptions.

4. Bierman, “Urban Memory,” 1–12.

5. The al-Ḥākim mosque retains the exterior from the period of Badr al-Jamālī. Its current interior is a modified version of that period. The exterior of the al-Azhar mosque is greatly layered and modified. See ibid., 3.

6. Ibid., 4; German Institute of Archaeology Cairo, Mausoleum des Sultans as-Saleh Nagm ad-Din Ayyūb (Cairo, 1993), and Minaret of Madrasa of as-Saleh Nagm ad-Din Ayyūb, report on the restoration projects of the German Institute of Archaeology in the District of Gamaliya (n.p., n.d.).

7. The madrasa of al-Ẓunddot;āhir Baybars is no longer extant.

8. The Ayyubids built on the west side too, but the structures are not extant today.

9. He became Sultan twice: 1294–95 and 1299–1309/693–94 and 698–708.

10. See Nairy Hampikian, “Restoration of the Mausoleum of al-Ṣāliḥ Najim al-Dīn Ayyūb,” in Bacharach, Islamic Monuments, 46–58; MAE 2: 94–103.

11. RCEA, vol. 2, nos. 4219, 4220; CIA, Egypte 1:576.

12. Sultan Qalā’ūn’s complex also included a hospital—but it was behind, not flanking the street. His family and retainers were avid builders. See Caroline Williams, “The Mosque of Sitt Hadaq,” Muqarnas 11 (1994): 55–56.

13. RCEA, vol. 13, Qalā’ūn nos. 4850; 4852, 4853; CIA, Egypt, vol. 1, nos. 83, 84, plate 25; al-Nāṣir Muḥammad, RCEA, vol. 13, no. 5006; CIA, Egypte, vol. 1, nos. 1, 133, 762.

14. MAE, vol. 2, plate 96.

15. For an easy reference to the function and social role of the structures discussed here, see Carl F. Petry, The Civilian Elite of Cairo in the Later Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), appendix 1.

16. See chap. 4.

17. MAE, vol. 2, plates 104b, 104c. This structure is discussed also in Richard Parker, Robin Sabin, and Caroline Williams, Islamic Monuments in Cairo, A Practical Guide, 3rd edition (Cairo, 1985) where there is handy reference to the inscription.

18. Bierman, “Urban Memory,” 8.

19. We need to consider the facades of both the mosque and synagogue before their recent expansions and restorations.