5. Excursus

Popular Culture and American Hegemony

For Weimar cinema the era of Neue Sachlichkeit has conventionally been related to thematic and stylistic adjustments which anchored film in real-life problems. It is symbolized by the abandonment of the mythical/historical or fantastic world of Caligari, Der müde Tod, Die Nibelungen or Faust for the asphalt and moral jungle of Dirnentragödie, Die freudlose Gasse and Die Büchse der Pandora. More fundamental to the new sobriety, however, than partly nominal shifts in production priorities was the process of coming to terms with Hollywood’s international dominance and presence in Germany. One practical form of this process, discussed in chapter two, was collaboration in production and distribution. The other was clinical assessment of the reasons for American hegemony, of Hollywood’s meaning for German culture and of the possibilities for resisting Americanization. In search of means by which to restore the fortunes of domestic filmmaking, experts retraced the origins of national defeat and reappraised the relationship between popular expectations and the American formula.

Hollywood’s domination of the global film market appears so much a natural right that its origins have received surprisingly little historical attention. Only recently, with research into the consolidation of the star system, studio production and Hollywood’s narrative tradition has the American achievement been historicized sufficiently to be seen as contingent rather than predestined. As this filmic achievement is anchored in changing American values and life-styles, the second and third decades of this century have become increasingly pivotal for readings of modern mass culture.[1] This era witnessed the first large-scale influx of American culture into Europe and the triumph of Hollywood’s products on European movie screens. In retrospect it holds the key to the enduring ascendancy of American popular culture. Broadly speaking, two mutually reinforcing explanations for American hegemony may be identified. The first emphasizes correspondence between the nature of the American product and popular demand, seeing the source of public interest in the combination of American narrative structures, cutting rhythms and cinematographic polish, on the one hand, and possibilities for audience identification provided by the relative openness of American society and the accessibility of American screen personalities, on the other hand. The second cites the substantial edge offered Hollywood by a large domestic market, wartime difficulties in European production and American exploitation of favorable circumstances through everything from rationalization of production to advertising.[2]

In essentials these explanations were first formulated in the 1920s. In a decade when for the first time Europe met three-quarters or more of its film demand from American supply, contemporaries could scarcely evade trying to rationalize Hollywood’s inroads. German film experts devised an explanation which combined American financial clout, havoc wreaked by inflation and overextension of resources in Germany with characteristic features of American motion pictures. In a nutshell: America was a prosperous, populous nation very fond of movies (this movie-mania was often attributed to the absence of alternate forms of entertainment, such as theater, and to the constraints imposed by prohibition). Producers could therefore afford the best talent and the most refined technical apparatus, sparing no expense to please moviegoers. Motion pictures enjoyed such public esteem that they received benevolent treatment by governmental authority through tariff protection and lenient taxation policies. Since production costs were covered by the return from the large and well-to-do domestic market, American corporations could underbid any competitor abroad.[3]

Immediately striking about this rationale was its point-by-point and often explicit contrast with circumstances prevailing in Germany. In a smaller, financially troubled country, with many fewer theaters, the investment required for major pictures could not be recovered on the domestic market. Cinema had to compete against long-established cultural traditions and overcome the suspicion of the cultural elite. In addition it faced hostility and exploitative taxation policies from the various levels of government.[4]

Although this explanation of Hollywood’s supremacy in no way denied the appeal of the American product, it tended to subordinate popularity to a set of commercial preconditions. As a result, though powerful and persuasive, it proved extremely problematic. Its very attractiveness as an interpretive paradigm made it almost useless for prescribing solutions, for on the basis of circumstantial factors it conceded dominance to the American cinema. By treating the motion picture as an industrial commodity whose distribution depended on considerations of investment capital, market size, and tariff protection, it minimized the relevance of national mentalities otherwise so eagerly cited and reduced the issue of competition to one of cost-effectiveness and government regulation. It also proceeded unhistorically in assuming Hollywood’s wealth was the cause rather than result of success. If, as it implied, the respective fortunes of German and American cinemas were determined by factors beyond their immediate control, there was scant possibility of creating a cinematic alternative to Hollywood which would simultaneously be remunerative.[5]

All this fit awkwardly with what experts interpreted as audience rebellion against Hollywood. Alone among major European states, Germany managed to retain close to half of its own feature film market. That accomplishment was backed by substantial indication that German audiences did not, as a rule, prefer the American product. Germany therefore had less reason than other states to accept American invincibility. By that token, the apparently persuasive case for Hollywood’s dominance could not stand unchallenged. Without disregarding Hollywood’s undeniable advantages, German experts clearly believed that improvements at home were in order and would enhance Germany’s competitive position. If that meant taking lessons from Hollywood, most of all in coordinating production strategies with the market, the prospect of Americanization could not be dismissed as altogether objectionable.

Identifying the areas in which Hollywood had a positive contribution to make to German cinema was a controversial enterprise in all phases of the Weimar period, but especially so at middecade. If, as trade circles generally argued, American motion pictures had exhausted their welcome, there seemed little point adopting Hollywood as a model. Remarkably, however, not all experts denied Hollywood’s ongoing relevance. Moreover, a number significantly qualified the reigning orthodoxy that German moviegoers had lost interest in American film. Situated mainly outside trade circles, thus lacking the commercial interests which had encouraged exhibitors to defend Hollywood’s reputation in 1924, they still found in American cinema qualities which German filmmakers needed to emulate.

Probably the most outspoken defender of Hollywood at a moment when prevailing opinion turned against it was Hans Pander. As a regular columnist and reviewer for Der Bildwart, a journal devoted to educational motion pictures, Pander would normally have been an unlikely candidate to champion American movie entertainment against the domestic industry. However, his interests reached well beyond educational film to include the relationship between motion picture production and public consumption. Writing for an independent journal, Pander established an independent line. In the aftermath of the Parufamet agreement he wrote a lengthy polemic against current wisdom on the significance of national differences and Hollywood’s economic advantages. He denied the national origins of a film more than a peripheral role in audience response. Moviegoers sought captivation and entertainment and would accept these from whichever nation best obliged them. He also indicated that America remained the leading source of such pictures for Germany as for all other countries. But he did not believe that Hollywood had a birthright to hegemony. It admittedly enjoyed an edge over Berlin because of the sums it could invest and the benevolent treatment it received from government. But these two givens could not be taken as decisive without abjectly surrendering to Hollywood.[6]

Pander’s rationalization of American superiority, to be pursued at greater length below, presupposed a level of popularity for American film which flew in the face of prevailing opinion. By late 1925 popular reaction against Hollywood appeared so ubiquitous that most experts simply took for granted that American films alienated German viewers. Reichsfilmblatt’s assault on American imports in 1925 initially appeared peculiar to that journal, but closer examination shows that trade opinion proved divided more about tactics than fundamentals. While Reichsfilmblatt heaped abuse directly on American producers, other journals, without exonerating Hollywood, tended to shift the responsibility to German importers and distributors. Film-Kurier, for example, urged more serious attention to the editing of American works since the form in which some were released raised suspicions that those responsible were covertly trying to discredit Hollywood. But it even more vehemently repudiated the suggestion that American movies had become victims of German chauvinism or deliberate smear tactics: public displeasure was genuine and rooted in the lesser quality or unsuitability of many American imports.[7]Lichtbildbühne offered similar double-talk. It judged theater owners’ complaints about American features exaggerated and misguided inasmuch as most American imports were potential popular successes if wisely edited. Yet Karl Wolffsohn, publisher of the journal, still insisted that even lesser native works filled theaters which better American pictures could not. Indirectly, he advised exhibitors to make the best of their unfortunate dependence upon Hollywood.[8]

It is striking, given the signs of anti-American sentiment, that Pander developed an argument for the supremacy of American motion pictures without questioning whether that supremacy actually obtained at the German box office. He simply deduced from Hollywood’s worldwide hegemony and his own impression of audience reactions the existence of a typical moviegoer whose demands were best met by American film. This disregard for empirical evidence makes his conclusion suspect, but not altogether unlike that of Hollywood’s detractors. For they too, in the absence of hard, comprehensive statistics, often resorted to educated guesswork.[9] Since the fairly impressive compendia of film facts and figures in the Weimar era did not include sure guides to the market results of motion pictures, contemporaries, like historians, had to try to piece this information together. German distributors and exhibitors had the raw material from which to derive box-office earnings, but unlike the Americans did not compile and publish them. Irmalotte Guttmann, a doctoral student whose thesis of 1927 represents one of the few attempts to ascertain box office results at middecade, found that many theater owners kept no accounts or only fragmentary records of ticket sales and receipts. Alexander Jason, another contemporary scholar who labored prodigiously to construct a comprehensive statistical picture of the German cinema, lamented that the trade tended to treat the relation between supply and demand more emotionally than scientifically. It had yet to grasp the supreme importance of complete, accurate data on theater attendance.[10]

Although it is safe to assume that trade generalizations about Hollywood’s unpopularity partially drew on inside information about the success or failure of specific pictures, hard published data to support trade opinion was in short supply. Much testimony to moviegoers’ disenchantment came from film critics and cannot be considered disinterested. The tendency to conflate signs of waning enthusiasm for American movies and analyses of its causes makes it extremely difficult to disentangle fact and interpretation. What follows presents tentative conclusions from the limited and somewhat conflicting evidence available.

It was Hollywood which in a twofold sense encouraged the first systematic attempts to determine audience preferences. American models of business operation suggested the importance of such information and Hollywood’s presence in Germany provided the principal ax to grind in determination of German tastes. The only broad survey of moviegoing trends in this period was pioneered at middecade and was largely preoccupied with the issue of domestic versus foreign successes on the German feature film market. Beginning in late 1925 Film-Kurier invited theater owners to submit a list of their five best and three worst pictures at the box office. The results of this annual poll, for 1925 and each subsequent year, overwhelmingly endorsed prevailing opinion—German viewers preferred the native product.[11] How much this result can be trusted is quite another matter. Here, as in other statistical endeavors, the aversion to rigor apparent in neglect of accurate bookkeeping is still very much in evidence. Among numerous distorting factors were the unrepresentative number of replies in the first two years of the survey, the failure to correlate votes for a film and seating capacity of the theater (which ranged broadly from 300 to 2000) and the seasonal nature of the voting, which severely disadvantaged pictures whose exploitation began late or was spread across more than one season.[12] More serious inconsistencies followed from failure to ask exhibitors to rank their replies. Every mention of a title therefore received equal weight, obscuring a potentially enormous gap between the top five pictures. Finally, the very basis of the replies remains unclear: in some cases they presumably reflected box-office records; in others simply impressions and general recollections. In sum, as a rough guide to audience preferences, the Film-Kurier poll is valuable, especially since it was one of a kind in Weimar Germany, but it should not be confused with box-office precision.[13]

A primary agenda of the Film-Kurier poll—to determine Hollywood’s place in German cinemas—dominated every other attempt from this period to determine the popularity of feature films. That agenda surfaces most blatantly in statistical evidence presented by Ludwig Scheer, president of the National Association of German Exhibitors, to the Association’s annual conference in Düsseldorf in 1926. In defense of the independent exhibitors’ crusade against Hollywood, Scheer cited attendance figures from his own operations in six provincial cities to argue that American films were ruining German cinemas. Comparing total attendance for “average” motion pictures, six German and six American, he claimed the former attracted 33,645 patrons in one week while the latter drew only 19,196. If one grants that the films and thus the week in question can be taken as representative, the relative weakness of American film in Germany seems difficult to deny. But Scheer was not content with this conclusion. Rather than qualifying his evidence he tried to construct from it an airtight case against Hollywood. Estimating that in the previous year 3,000 German cinemas had given half their playing time to American features, he extrapolated from his own figures to conclude that in 1925 Hollywood had cost German theaters a grand total of 187,837,000 patrons—more than half again of the actual number.[14]

Jackie Coogan in A Boy of Flanders, set here amidst Berlin’s daily press, 1925. (Photo courtesy Landesbildstelle Berlin)

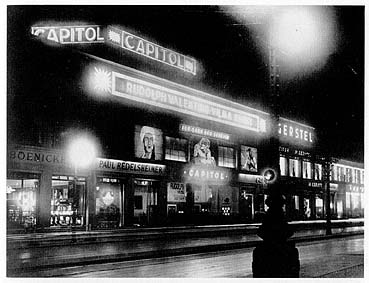

The Son of the Sheik, with Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky, at the Capitol Theater, 1926. (Photo courtesy Ullstein Bilderdienst)

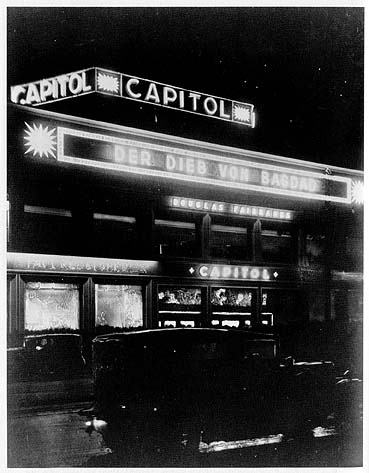

The Thief of Bagdad, with Douglas Fairbanks, at the Capitol Theater, 1925. (Photo courtesy Ullstein Bilderdienst)

Charley’s Aunt, with Sydney Chaplin, at the Albert Schumann Theater, 1925. (Photo courtesy Landesbildstelle Berlin)

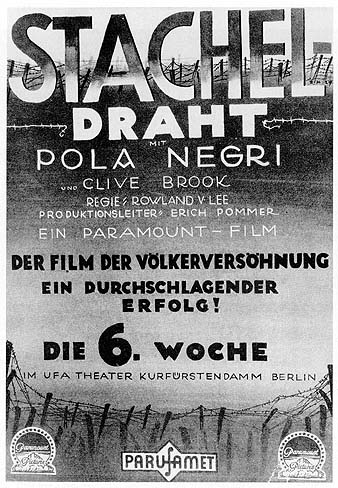

Barbed Wire, Erich Pommer’s second Paramount production, starring Pola Negri, in its sixth week at UFA’s Kurfürstendamm Theater, 1927. (Kinematograph, 16 October 1927, p. 22.)

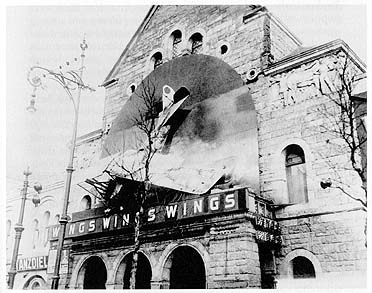

Facade of UFA-Palast am Zoo for Wings, 1929. (Photo courtesy Ullstein Bilderdienst)

Such cavalier treatment of statistics from a leading business figure testifies to the emotion generated by Hollywood’s inroads. In the absence of any more trustworthy and comprehensive data Scheer created his own patently self-serving calculations. As Alfred Rosenthal retorted, too many variables came into play to permit such sweeping conclusions from a handful of cases. A different set of figures could prove precisely the opposite argument.[15] Nonetheless, there is corroborative evidence—albeit still limited in scope—to suggest that the case Scheer tried to establish had some foundation in fact. In its middecade crisis UFA carried out a confidential audit in the distribution sector to compare the company’s fortunes with domestic and American feature films. The report paints a picture of crushing financial loss through pre-Parufamet commitments to handle American film. In the crucial season 1925–1926 ten of eleven pictures from Paramount, twelve of fifteen from Goldwyn, ten of fifteen from First National, and seven of twelve from Warner Bros. each entailed losses of 10,000 marks or more for UFA. Fully three-quarters of UFA’s American releases fell into this category, for losses totalling 1,283,796 marks! Only three American pictures (Rin Tin Tin in Lighthouse by the Sea, Buster Keaton’s The Navigator and Victor Sjöström’s He Who Gets Slapped) showed significant profits. By contrast a mere four to six percent of the remaining, mostly domestic, movies distributed by UFA caused losses greater than 10,000 marks.[16]

The UFA audit confirms the findings of Film-Kurier and the very limited evidence offered by Ludwig Scheer. However, it stands in considerable contrast to the most sophisticated analysis of moviegoers’ preferences from this period, the dissertation by Irmalotte Guttmann to which reference has already been made. It too was preoccupied with German-American rivalry, seeking to explain and erect barriers against American inroads. It drew, moreover, on a combination of the sources used by UFA, Film-Kurier and Scheer. Guttmann questioned theater owners in Cologne and Danzig for specific case studies and gained access to the distribution records of Parufamet (1926–1927) as the basis for national conclusions. In the first instance she distinguished three grades of movie theaters—premiere, middle class and working class—to relate the types and origins of feature films to the social background of the audience. Replies to the poll indicated that the best American films were popular at both extremes—in the movie palaces and among workers—while middling native productions best suited the petty bourgeoisie. Guttmann concluded that German producers were being displaced in two of three market categories, though she conceded that these results did not necessarily apply nation-wide.[17]

In the second section of her research she then checked these results over a larger area. On the basis of Parufamet’s books she selected theaters from twenty-five cities with more than 200,000 inhabitants as test cases. Receipts from eighty theaters of all types showed that the least profitable German features drew much better than their American counterparts, but that the four most successful American movies outdrew German box office hits by more than 2 : 1.[18] These figures spoke for themselves, but Guttmann, like Scheer, had greater ambitions—to prove that Hollywood provided more of these successful pictures than did native producers. Abandoning empirical investigation she appealed to the opinions of experts to argue that in the previous season four times as many American as native features were hits on the German market. Her conclusion therefore had two aspects. American movies attracted a broader public—though less so the petty bourgeoisie—and Hollywood provided a much higher proportion of successful films.[19]

Since portions of Parufamet’s books have been preserved in extant UFA files it is possible to exercise some historical control over Guttmann’s conclusions. UFA, stung already by the audit of the season 1925–1926, had reason to monitor Parufamet’s performance very carefully. After the new management under Alfred Hugenberg took charge in the spring of 1927, Parufamet’s first season came under thorough review. The result was a picture of profit and loss from American pictures which corresponds closely to the perceptions of experts about the discrepancy between run-of-the-mill and outstanding Hollywood pictures. In terms of gross revenue, the fact that the combined income of Parufamet and UFA’s own distribution agency equaled projections for the latter had Parufamet not been created intimated that UFA’s own productions largely carried the company in 1926–1927.[20] A comparison of revenue from the feature films contributed by each company initially overturns that conclusion. In total rental receipts Metro-Goldwyn pictures easily topped those of UFA and Paramount. However, the source of this discrepancy was one motion picture, Ben Hur, which grossed over one-third of Parufamet’s total revenue; alone more than all UFA pictures released by Parufamet and almost twice as much as all those from Paramount! Without Ben Hur, the income from eighteen UFA pictures roughly equaled that from thirty-one features of Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn, substantiating UFA’s estimate that an average UFA release was worth twice as much as an average American film. Moreover, apart from Ben Hur, Metro-Goldwyn’s performance on the German market was almost entirely disappointing.[21]

The rental records Parufamet forwarded weekly to UFA did not, unfortunately, include breakdowns by city. It is therefore impossible to comment directly on Guttmann’s assertions about the superior performance of the best American pictures in the largest urban areas. Cumulative totals indicate that UFA produced at least as many winners at the box office as the American companies combined. There is also some evidence that UFA’s exhibition division had to cope with the backlash caused by American motion pictures which alienated German moviegoers.[22]

What can one conclude from this rather fragmentary, uneven and at times contradictory evidence about the popularity of American feature films in Germany? Although no formula can reconcile Guttmann’s research, the Film-Kurier poll, Ludwig Scheer’s findings and UFA’s records, with proper qualifiers several generalizations can be made. Given the shifting terms of reference of these sources, extrapolation from any one of them without controlling dependent variables through the others is perilous. Guttmann’s dissertation is both unique and invaluable, not least for its attention to the moviegoing habits of different social groups. By focusing on box-office hits it directly challenges the broader findings of the Film-Kurier poll. However, by the same token it sidestepped a crucial issue, namely, whether run-of-the-mill American pictures were hurting theater business.[23] Since no one, including Ludwig Scheer, denied the appeal of select American films, this constituted a serious evasion. Moreover, Guttmann’s research did not cast much light on trends outside the purview of Parufamet, the largest but by no means a monopolistic distributor. What her results do indicate is that a single season, 1926–1927, does not make a trend. UFA’s experience with American features in 1925–1926 proved singularly unhappy. By contrast, interim results for Parufamet’s second year, 1927–1928, indicate that although Metro-Goldwyn pictures continued to perform miserably, Paramount films outdrew those from UFA by a substantial margin.[24]

What stands out on the basis of distribution records is the enormous range of responses to Hollywood. At one extreme, Ben Hur represented a phenomenon probably without equal in the 1920s. At the other extreme, numerous American features failed to do more than cover their rental costs. Here then appears confirmation of trade opinion that German viewers had grown tired of American Durchschnitt but still enjoyed the outstanding imports. However, to argue that Hollywood’s average movies flopped begs further definition. In terms of production cost Ben Hur, for instance, certainly ranked as an outstanding motion picture, yet to disgruntled critics it typified much of what was wrong with Hollywood. Conversely, what was standard fare for the American market, such as a Rin Tin Tin picture or a feature slapstick, could qualify as a special attraction for German moviegoers. Insofar as the receipts for Parufamet pictures are a guide, the least attractive of Hollywood’s products were society dramas. Nonetheless, no fixed set of criteria distinguished American pictures which won popular approval. In some instances star value appears determinative: La Bohème with Lillian Gish and Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman were hits of 1926–1927. In other cases, such as the war picture Hotel Imperial and a film about the foreign legion, Beau Geste, subject matter and dramatic treatment probably weighed more heavily. Ben Hur’s phenomenal success presumably was rooted in its sensational mass scenes. Although in each of these cases budgets exceeded all but the most extravagant in Germany, and production values were correspondingly of the first rank, this is no demonstration that the most popular American pictures were uniformly the most expensive to produce.

By the same token, despite some hard data to support impressionistic evidence of sagging public interest in American movies, it is misleading to assume a uniform public. As Guttmann’s study indicates, popular appeal varied according to the social background of the audience as well as film type and nationality. The relatively homogenous public which experts tended to assume did not exist. Distinctions between the working class and the petty bourgeoisie, although insignificant economically, continued to shape status perceptions and motion picture preferences.[25]

With all these qualifications to accepted wisdom it is clear that Hollywood was anything but synonymous with motion picture entertainment in Germany by the mid-1920s. American motion pictures encountered a somewhat jaundiced public and did not command respect on the basis of their origins alone. Some types enjoyed more appreciation than others, depending in part on the social composition of the audience. Otherwise it is difficult to generalize. UFA’s pre-Parufamet audit probably came closest to summarizing the very uneven popular appreciation for Hollywood when it concluded laconically that further unpleasant consequences would ensue if in the future Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn pictures were not chosen with greater caution. This warning, ironic given that it came after signature of the Parufamet agreement, and doubly ironic in light of the box-office success of Ben Hur, indicates that American motion pictures could be both bane and blessing in the German context.[26]

| • | • | • |

Against this backdrop, Hans Pander’s defense of Hollywood must be read with a critical eye, but nonetheless taken seriously. For although Pander’s case was predicated on American popularity, it ultimately aimed to challenge the economic argument for Hollywood’s international hegemony at its weakest point, namely, its fatalism. As indicated above, no one serious about German film culture counseled selling out to America on the grounds that competition had become hopeless. But many compartmentalized their thinking to locate the source of German problems in exogenous factors by treating the motion picture as an article of trade.[27] Pander adopted this treatment, but turned conventional wisdom against itself by asking why Germans refused to be consistent in their approach. If the Americans succeeded essentially because they respected the industrial nature of the medium and followed sound marketing practices, why did German producers not copy them? Hollywood was an industry whose primary task was “to produce such a commodity as the market either demands or as it can at least absorb.” Consequently, it subordinated technical possibilities or the personal preferences of the director or performers to the tastes and desires of moviegoers. Since sound business practices counted more than national tastes or artistic innovation, Pander concluded Hollywood earned its hegemony.

Without denying America’s enviable financial preconditions or its seemingly inborn cinematic sense, Pander indicated that American producers prospered by virtue of organizational and marketing techniques which were well within the grasp of German filmmakers.Whoever sees German and American films regularly simply cannot fail to notice that on the average the Americans are better, i.e. not better made, but better calculated from the start, with a more confident psychology of the consumer.[28]

Although one does not have to search very far to discover other commentators critical of unremunerative aestheticism, Pander’s outspoken admiration for Hollywood’s orientation was not typical, especially at middecade. The previous chapter noted critical and public rebellion against the very practice Pander seemed to applaud, that is, mathematically precise calculation by American producers of the relative proportions of good, evil, romance, sensationalism and emotion blended in every movie. Apart from the fact that the specific American blend offended German sensibilities, its very calculatedness and predictability created distaste. Pander claimed not to believe this, rejecting orthodox opinion on national taste differences and Hollywood’s unpopularity. Nonetheless, he was not alone in suggesting that even now Hollywood had lessons to teach. Whether schoolmaster or outcast it encouraged perception of German problems through American lenses. Even critics disgruntled with its films interpreted its hegemony in terms which implicitly endorsed partial Americanization of German culture.

Roland Schacht, whose account of Hollywood’s waning popularity has already been examined, offers a prime illustration of the critic’s dilemma. As early as 1923 Schacht had insisted that the crisis in the German film industry which opened the door to Hollywood could not be written off to economic difficulties: it flowed from failures in management, imagination and dedication. At middecade he took up this theme with a vengeance, stressing the importance of efficient business methods and need for a consistent production rationale.[29] Anticipating Pander, Schacht argued that Germany had no lack of talent, the best of which surpassed America’s frontrunners, but failed to organize and exploit its strength with the dedication characteristic of Hollywood. The domestic film industry did not adhere to the “simple business rule that customers must be offered real value for their money if one wants to make a profit.”[30] Schacht denigrated the schematicism of Hollywood, yet he believed the German cinema could profit from its example. Like Pander he approved American commitment to popular impact or entertainment and compared it favorably with the German aspiration to create film art.

Against what he called artistic “contempt for the masses” in Germany, Schacht set the “democratic worldview” of America which understood culture as a consensual phenomenon rather than the preserve of an educated elite. He concluded that “in the final analysis film production is thus a social problem. It demands connectedness, community with the people.”[32]The German who makes art is unconcerned about whether the company financing him is thereby economically ruined. The American says to himself: how can it be art and what use is it if no one wants it, if people don’t even want to lay out the price of admission voluntarily to see it? And who will give me money any longer so that I can make art if I ruin one company after another?

The German either makes art for himself in a vacuum, at best for his class, to which he occasionally condescends to be willing to elevate even the “lower” people, without giving a thought to the economic basis of his production, or unscrupulously and bent on nothing more than quick profit he makes trash for the mob.[31]

Schacht’s dissection of American film culture isolates characteristics which in one respect had already become platitudes. It was a commonplace that Hollywood reflected the New World’s democratic traditions and social leveling. Its ability to appeal to the lowest common denominator, recognized from the beginning of the decade, was initially related primarily to filmic ingredients such as shot rhythms, acting styles, or narrative tempos. By middecade, terms of reference had shifted to approximate those familiar to subsequent scholarship, namely, rationalization of production, star value, advertising strategies and audience identification with screen characters. This shift in emphasis from technical-artistic impulses to the organizational and public dimensions of the medium brought experts face to face with tensions in their own visions for motion picture development.[33]

Since 1918 German interest in foreign markets had dictated respect for America’s motion picture mentality. Postinflationary reaction against Hollywood challenged that respect. Viable competitive strategies against American cinema remained elusive. Roland Schacht, while making Hollywood’s agenda inescapable for domestic development even as he resisted mass American import, groped towards a third way between national solipsism and international (i.e., American) homogeneity which would supply a radical cure for domestic production and exhibition woes. By explicitly anchoring the cinema in sociocultural context Schacht made domestic problems the symptoms of broader developments. His focus fell not on economic or legal questions, but on the dualism between art and popular culture, particularly on filmmakers whose artistic consciences caused disdain for commercial considerations. Even when they sought to create popular, commercially successful motion pictures, their awareness of condescending to mass sensibilities robbed their work of conviction and impact. To create in bad faith inevitably resulted in inconsistent pictures which failed to grip broad audiences.[34]

The remedy Schacht suggested was obvious enough: re-education or replacement of filmmakers who believed art and popular culture to be incompatible. But by the inexorable logic of his own argument it could only be implemented in conjunction with a cultural revolution. The source and nature of that revolution could hardly be in doubt. Americanization of German assumptions about the relationship between culture and society, if not of society itself, was necessary to permit native filmmakers to rival their American counterparts. Schacht declined, given his aversion to aspects of the American model, to state the case so plainly, but his arguments pointed unmistakably in this direction.[35]

The unspoken conclusion yielded by Schacht’s analysis of domestic cinema problems emerges from the arguments of others dedicated to preservation of a distinct German cinema. Herbert Ihering, even more strongly opposed to Hollywood’s breed of cultural imperialism, came independently to equally ambivalent conclusions. Like Pander and Schacht, he too rejected one-track economic explanations for the misfortunes of native production. He also cited a fundamental distinction between American and German approaches to film production which was rooted in different understandings of the relationship between art and popular culture and between culture and technology. Whereas the German cinema, uncertain of its public role, oscillated between artistic experiments and popularizing, Hollywood knew no such bifurcation. The link between cinema and society emerges once again as the critical issue.

Since the problem lay as much with the consumer as the producer, its solution clearly lay beyond tinkering with German cinematic technique or borrowing from Hollywood. American dramatic devices derived authenticity and impact from the indivisibility of filmmaker and public. What for the German producer would be deliberate falsification—in Schacht’s terminology, conscious condescension to popular taste—and thus unconvincing, succeeded in Hollywood because there was no concession or compromise born of the gulf separating producer and consumer. Ihering therefore expressly warned against the superficial, futile exercise of copying dramatic devices indigenous to Hollywood. Instead, like Schacht, he covertly advised the need for cultural Americanization. This he understood as a process of reconciliation between technology and preindustrial cultural norms. What in Germany remained a proverbial gap between culture and technology had been bridged in the United States.[37] Until Germany paralleled this achievement Ihering believed native film production would be poorly synchronized with its audience.In America the cinema is immediate because the producers are themselves the public. In Germany they either consider themselves better: literati and intellectuals; or they are worse: speculators and dealers.…Perhaps the cinema requires an impersonal, a nonisolated public—America—and not an individualized one—Germany. In America the film public is there from the beginning. In Germany it has to be created by each film.[36]

Thus although Ihering welcomed Americanization of German culture even less than Schacht, his prescription for establishing the cinema’s popular relevance included it.When a generation has grown up in Germany which has risen with the inventions [of modern society], which does not know a world without the telephone, radio, cinema and the automobile; when therefore technology has also become a matter of course for us,…when there is experience and intellect again beyond technology, then there will also be a public in Germany again, then the German cinema and even the German theater will exist.[38]

Schacht and Ihering followed a logical sequence in arriving at reluctant approval of the American model. The first step was rejection of a purely economic rationale for American film supremacy. Its corollary was refusal to accept German misfortune as predetermined. This brought solutions into the realm of the possible but also forced a search for mistakes and misconceptions. This search identified characteristics within German culture which militated against competitive film production. Without absolving native filmmakers, Schacht and Ihering decided that cultural preconditions required modification to place domestic production on a sound footing. The United States provided the obvious source of inspiration for this task not only because of Hollywood’s current hegemony but because American culture as a whole exhibited many features thought to be signposts of the future for industrial societies. Neither critic advocated blind or wholesale adoption of Hollywood’s methods, yet both intimated the need for Americanization.[39]

The reflections of Pander, Schacht and Ihering contextualize a better known and direct debate on German misfortune conducted by another prominent critical trio. In early 1928 Kurt Pinthus, Willy Haas and Béla Balázs locked horns over the origins of the domestic film malaise. Pinthus opened the debate with a wide-ranging lament about current circumstances. From the opaque assertion that the German predicament followed less from economic factors than from the “miserable quality” of German film, he developed an indictment not only of shoddy workmanship in German production but of the import legislation and American capital which encouraged cheap, third-rate “quota films.” A stinging rebuke, worthy of Schacht at his most vehement, of the complacency, carelessness and incapability of German producers, Pinthus’s argument simultaneously supported trade opinion that the German cinema was fulfilling the role to which American supremacy relegated it.[40]

The replies to Pinthus from Haas and Balázs approached the German problem quite differently, but in each case the American cinema formed the essential reference point. Pinthus had openly admitted the superiority of American motion pictures. Haas made Hollywood’s industrial and financial hegemony, more precisely its dependence on Wall Street, the overriding factor in contemporary motion picture development. Balázs focused directly on the theme elaborated by Schacht, the fusion in American culture of art and popularity. Significantly, neither Haas nor Pinthus could avoid reference to this theme even though they emphasized other issues. Haas continued to entertain visions of a third cinematic way fusing American technology and German creativity. He refused to concede that the American model was the only one possible for overcoming the antithesis between art and popular culture. The “decisive battle” over whether film would serve or command the human race remained to be fought.[41] While Haas clearly aspired to command, Pinthus decided the motion picture could only serve: he advised domestic filmmakers to surrender considerations of quality in order to achieve popular appeal. Balázs challenged this last opinion directly, without endorsing Haas. In language reminiscent of Pander he rephrased the dualism as that between “good” art and “popular” art. Against Pinthus he argued that Hollywood made allies of these categories while German filmmakers treated them as antagonists. Like Schacht, Balázs thought the problem not unique to the cinema, but a symptom of cultural standards inbred in the educated middle class. What Pinthus dubbed the film crisis therefore represented one aspect of a general crisis in German culture which had to be overcome to establish domestic production on a sound footing.[42]

To Haas, Balázs and Pinthus America represented financial power, a cultural model and a cinematic model respectively. The latter two implied the need for Americanization, though neither welcomed the prospect any more than Schacht or Ihering. In another context (see chapter seven below) Haas came to very similar conclusions, though no more willingly than his critical colleagues. Ultimately none of these very acute observers of German cultural trends was prepared to recommend Americanization. Too discriminating and realistic to accept as satisfactory standard explanations for Hollywood’s global preponderance, they remained too disturbed by features of American culture to advocate its general adoption for German purposes. Unlike the dramatists in Hollywood, they could not introduce some deus ex machina to rescue them from the impasse. What they required was a formula which while giving due recognition to Hollywood also gave domestic filmmakers clear direction. Blanket anti-Americanism could not stand close scrutiny, yet the German cinema still needed to distinguish itself from Hollywood.

The dilemma faced by German cinema was that of any culture threatened by displacement or extinction, namely, whether borrowing presents a viable method of preserving independence. To enter into competition with Hollywood implied accepting American terms of reference. It simultaneously stiffened resistance to American methods and mentalities. As noted in chapter two, debate revolved around whether native filmmakers could best compete internationally by cultivating a national or cosmopolitan style. Preference for the former coexisted with vagueness about what constituted “German” cinema. By middecade sentiment hardened that native talent should not try to imitate American models, not least because these had become so pervasive in Germany. But against sentiment had to be set the uncomfortable reality of American hegemony and the size of its market, the vital context for UFA’s decision to collaborate with Hollywood and orient production to American consumers. Not surprisingly then, the search continued for a third way.

In terms of critical discourse, a vague filmic application of Neue Sachlichkeit became the formula by which some experts hoped to discover new terrain. The quest for a comprehensive solution to German problems necessitated demolition of the barrier between commercial and aesthetic categories. So long as Hollywood dominated cinema screens, laments about its character and alleged unpopularity confused the search for a national alternative. Reluctance to advocate the outright Americanization of German culture pushed some experts to seek the foundation for a national cinema in another sphere. Neue Sachlichkeit, a cultural mode lifted partly from the American socioeconomic example, became a device for distinguishing German motion pictures from Hollywood, reaffirming the possibility of a popular national cinema and avoiding Americanization.[43] Since realism stood at the pole opposite American untruthfulness in respect of characterization, emotional content and causality, it formed the obvious antidote to Hollywood. Pundits counseled filmmakers to borrow business and stylistic matter-of-factness from Hollywood but treat subjects of current national interest. This counsel also conformed to what was perceived as the drift of public tastes away from pomp and cheap emotionalism.

Sentiment is no longer in order. The world of traffic lights, of radio transmission of dance music and of technological autocracy doesn’t like lovers who walk hand in hand into the setting sun. It smiles at mystical gentlemen from the criminal underworld. There are no more Casanovas, no Cagliostros, no robbers. The big adventurer is anonymous. [The world] hails the more palpable heroism of the Tunneys, the oceanic intoxication of the Chamberlains and the Kohls, the six-day racers and fashion queens.[44]

Yet if German experts employed realism as the acid test of a motion picture’s excellence, Hollywood’s hegemony could not be broken with a trendy formula, particularly one as ambiguous as realism. Its attraction is understandable enough: it appeared to promise both intellectual respectability and popularity. Contemporary, down-to-earth themes could broaden the appeal of the native cinema without requiring it to bow openly to Hollywood.[45] Yet as the case of Greed illustrates, it was not a cure-all. Béla Balázs responded sharply to the “fashionable slogan of the realist dogmatists” because he saw in it the same intellectual tendencies—abstractness and doctrinairism—which traditionally hampered German film creativity. A new slogan would not bring salvation to German cinema. Adducing the recent works of Charlie Chaplin, the most highly respected of American film personalities, Balázs maintained that success could not be ascribed to realism. In reaction against kitschy romanticism, critics missed the point:

By this definition realism had nothing to do with Erich Stroheim’s naturalism. It referred rather to that ability to capture common human sentiments which Schacht and Pander credited to Hollywood. Balázs’s enlistment of Chaplin, rather than domestic achievements, to substantiate his argument, pointed back to Hollywood even as it sought to refocus the German cinema agenda. The next chapter documents how Chaplin and the entire slapstick tradition were enlisted to address discontinuities perceived in German film culture.The opposite of false is not real but genuine, the opposite of mendacious is not real but truthful, the opposite of lifeless and empty is not real but alive, striking, graphic. Even a fairy tale can be genuine, truthfully striking, graphic. Just as a Chaplin fairy tale is.…For there is no reality without the human being, without his feelings, moods and dreams.[46]

Notes

1. Cf. Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema; Janet Staiger and Douglas Gomery, “The History of World Cinema: Models for Economic Analysis,” Film Reader, 4 (1979), 35–44; and the pioneering study by Lary May, Screening out the Past.

2. Cf. the formulations by Buscombe, “Film History and the Idea of National Cinema,” pp. 141–143; Thompson, Exporting Entertainment, pp. x, 1, 100; de Grazia, “Mass Culture and Sovereignty,” pp. 57-61; Salt, “From Caligari to Who?” p. 123; Miles and Smith, Cinema, Literature and Society, pp. 166–177; Staiger and Gomery, “The History of World Cinema,” pp. 36–38.

3. See the summary by Roland Schacht in Das blaue Heft, 5 (1 February 1924), 14. Cf. UFA’s annual report for 1924–1925 and 1925–1926 in BA-UFA R109I/1046. Variations on the theme are S-r. (Albert Schneider), “Immer die Anderen!” Film-Journal, 11 March 1927; Kurt Mühsam, “Der Film für junge Mädchen,” B.Z. am Mittag, 16 September 1927; “Der Weltmarkt des Films,” Film-Kurier, 28 April 1928.

4. The American danger thus became a weapon in the struggle against the entertainment tax and censorship. See the pamphlet by Walther Plugge, Film und Gesetzgebung, commissioned by Spio (Spitzenorganisation der deutschen Filmindustrie) and his article, “Weltwirkung des Films,” in BA-Reichskanzlei R43I/2498, pp. 222–236; 237–243. Cf. the report from the ministry of finance of 8 June 1926 on regulation of the entertainment tax, ibid., pp. 263–268. A useful summary of the German predicament is Alfred Ruhemann, “Der Film / Sache der Nation,” Süddeutsche Filmzeitung, 12 March 1926, pp. 1–2.

5. “Und dennoch 1:1,” Film-Kurier, 26 November 1926: “Film is not merchandise!…Indeed, precisely because film is not merchandise we can compete with America.…In the cinema Geist can balance the monetary supremacy of the competition.” Cf. Walther Rilla, “Gedanken über eine Produktion,” Film-Kurier, 7 April 1928.

6. Hans Pander, “Die ‘amerikanische Filmgefahr’,” Der Bildwart, 4 (1926), 227.

7. “Die Fehler der Amerikaner,” Film-Kurier, 28 May 1926.

8. K.W., (Karl Wolffsohn), “Ist die deutsche Filmindustrie amerikanisiert?” Lichtbildbühne, 24 April 1926, pp. 7–8.

9. Salt, “From Caligari to Who?” p. 123, duplicates this pattern when he takes for granted German preference for American films in the 1920s.

10. Irmalotte Guttmann, Über die Nachfrage auf dem Filmmarkt in Deutschland (Berlin: Gebr. Wolffsohn, 1928), p. 12. Jason, Handbuch der Filmwirtschaft, vol. I, pp. 9–10. Cf. the plea for “Mehr System,” Lichtbildbühne, 14 February 1925, p. 15.

11. Averaged over the years 1925–1930, the results showed 67.6 percent of the votes for native pictures, 19.3 percent for America and 13.1 percent for European imports; Jason, Handbuch der Filmwirtschaft, vol. I, p. 60.

12. There was, to be sure, a steady increase in participation, from 350 theaters (8 percent of the total) in 1925–1926 to 1138 cinemas (21.9 percent of the total) in 1929–1930. Ibid., p. 60. UFA did not permit its cinemas to participate.

13. Guttmann, Über die Nachfrage, p. 11; Georg Mendel, “Was sind Umfragen wert?” Lichtbildbühne, 9 February 1926.

14. “Die Düsseldorfer Tagung,” Reichsfilmblatt, 31 July 1926, pp. 3–4.

15. See Aros, “Tagung mit Zwischenfällen,” Kinematograph, 1 August 1926, p. 10. Cf. “Zahlen allein beweisen nichts,” ibid., 8 August 1926, pp. 11–12. Double features, frequently one German and the other American, bedeviled attempts to compare audience preferences.

16. BA-UFA R109I/2440, pp. 26–27. This report, which runs to sixty pages, with tables giving precise distribution returns, is one of the most revealing documents of UFA’s troubles and troublesome relations with Hollywood in this period.

17. Guttmann, Über die Nachfrage, pp. 17–18, 25, 36.

18. Ibid., pp. 51–52, 59.

19. Ibid., pp. 65–67.

20. “Betrifft Lage der Parufamet Ende April 1927” (29 April 1927) in BA-FB/UFA 258, pp. 3–6.

21. Ibid. pp. 1–2. For a detailed breakdown of receipts at season’s end see “Parufamet Erträge, 7. April 1927,” in BA-FB/UFA 258.

22. See the correspondence of November and December 1926, especially Gabriel to Bausback, 20 November 1926, and Bausback to Parufamet, 8 December 1926, in BA-FB/UFA 435.

23. Guttmann, Über die Nachfrage, p. 8, fn. 2, justified the emphasis on successful films with the argument that they circulated more thoroughly than the failures and thus reflected market trends more accurately.

24. See Anlage 2 of Parufamet to UFA, 23 February 1928, in BA-FB/UFA 258.

25. Kracauer’s conclusion for Berlin in his “Cult of Distraction: On Berlin’s Picture Palaces,” New German Critique, No. 40 (Winter 1987), 91–96, should not be taken as representative of the country. Cf. Sandra Coyner, “Class Consciousness and Consumption: The New Middle Class During the Weimar Republic,” Journal of Social History, 10 (1977), 310–331.

26. Experts tagged UFA with colossal lack of discrimination in its selection of American motion pictures, particularly those from Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn. Cf. Roland Schacht’s remarks in Das blaue Heft, 8 (1926), 305–306; “Zahlen allein beweisen nichts,” Kinematograph, 8 August 1926, p. 12. For the high initial costs incurred by UFA in cornering the import trade see BA-UFA R109I/2440, pp. 31–32.

27. For exceptions see Alfred Rosenthal, “Europäische Flimmerwahrheit,” Kinematograph, 11 April 1926, pp. 3–6: “For once it must be openly stated: we have devoted too much money, too much energy and too much intelligence to useless artistic experiments.” Cf. “Reine Bahn,” Film-Kurier, 24 April 1926, which insisted that the German film dilemma was not a financial problem but one of “idealism, intellect, spirit and ideas.”

28. Pander, “Die ‘amerikanische Filmgefahr’,” pp. 228–231. Cf. Ejott, “Taylorisierung der Filmindustrie?” Film-Kurier, 19 January 1924.

29. Cf. his comments in “Deutsche und Amerikaner,” Das blaue Heft, 5 (1 December 1923), 26; “Prestige und Produktion,” ibid., 6 (1925), 245.

30. Cf. his “Drei Frauenfilme,” ibid., 9 (1927), 135; “Stagnation,” ibid., 8 (1926), 197.

31. “Deutsche und amerikanische Filme,” Der Kunstwart, 39 (1926), 267–269, here p. 268.

32. Schacht, “Das Problem der deutschen Filmproduktion,” ibid., 40 (1927), 416–419, here p. 417. This article draws together the major threads in Schacht’s critical writing.

33. Cf. for instance, P.V., “Mut zur Kolportage,” Film-Kurier, 9 May 1924; W. H. (Haas), “Der Kitsch ist kein Geschäft mehr!” ibid., 22 December 1924.

34. See Schacht, “Abstieg zum Kitsch!” Das blaue Heft, 6 (1924), 133–138, for an early formulation of this point in conjunction with discussion of popular movies. Cf. his “Filme,” Der Kunstwart, 40 (1927), 263–265. Better known comparisons are Carlo Mierendorff, “Hätte ich das Kino,” Die Weissen Blätter, 7 (1920), 86–92 (reprinted in Kaes, Kino-Debatte, pp. 139–146.); Franz Schulz, “Definitionen zum Film,” in Zehder, Der Film von Morgen, pp. 44–51; Adolf Behne, “Die Stellung des Publikums zur modernen deutschen Literatur,” Die Weltbühne, 22 (1926), vol. I, pp. 774–777.

35. Peukert, Die Weimarer Republik, pp. 181–188, argues that some intellectuals who decried Americanization favored progress but sought to salvage human freedom and dignity in the process. On these progressive defenders of cultural values cf. Heller, Literarische Intelligenz und Film, p. 124.

36. Ihering, Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. I, p. 492; vol. II, p. 513.

37. Cf. “Filmschau,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 341, 24 July 1921, p. 9; “Jannings- und Jackie-Coogan-Filme,” in Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. I, pp. 462–464; “Filmrückschritt,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 92, 24 February 1925. “Das alte Nest,” Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 143, 25 March 1923, p. 7; Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. II, pp. 479–481, which explores this theme in response to The Ten Commandments.

38. Ihering, Von Reinhardt bis Brecht, vol. II, pp. 506–507.

39. On the context for this ambivalence see Fulks, “The Kulturfilm,” pp. 138–141.

40. Pinthus, “Die Film-Krisis,” Das Tagebuch, 9 (1928), 574–580. Pinthus encouraged the study by Guttmann and made reference to her findings before they were published. His generalization from her conclusions brought a lengthy rejoinder, complete with the statistics produced two years previously, by Ludwig Scheer: “Film-Krisis?” Lichtbildbühne, 14 April 1928.

41. Das Tagebuch, 9 (1928), 716.

42. Ibid., p. 760. For analyses of the film crisis which follow Balázs closely see Hermand and Trommler, Die Kultur der Weimarer Republik, pp. 278–281; Zsuffa, Béla Balázs, pp. 172–175. Cf. the general criticism of Balázs’s thesis in Peukert, Die Weimarer Republik, p. 187.

43. Political polarization in the cinema became problematic precisely because the competition in America and Russia could afford to be “unpolitical.” Their “realism” catered to a specific market, whereas Berlin’s encountered division. See Rainer Berg, “Zur Geschichte der realistischen Stummfilmkunst,” pp. 12–13, 268.

44. (Hans-Walther) Betz, “Filmkrise? Krise des Geschmacks,” Der Film, 23 May 1928, pp. 1–2. Cf. Kurt Pinthus’s reference to American and Russian work as proof of popular interest in contemporary themes in Das Tagebuch, 9 (1928), 578–579; Willy Haas, “Die Krise der deutschen Filmindustrie,” Die Literarische Welt, 12 February 1926, pp. 3–4.

45. Rainer Berg’s “Zur Geschichte der realistischen Stummfilmkunst,” focuses on trade opinion, but fails to emphasize the extent to which the industry adopted the slogan to counter American intrusions.

46. Das Tagebuch, 9 (1928), 761.