4. The Political Crisis of the Seventeenth Century

Firstly, the aforesaid Lord King [Philip IV of Spain] declares and recognizes that the aforesaid Lords States General of the United Netherlands and the respective provinces thereof, with all their associated districts, cities, and dependent lands, are free and sovereign states, provinces, and lands, upon which, together with their associated districts, cities, and lands aforesaid, he, the Lord King, does not now make any claim, and he himself and his successors descendants will in the future never make any claim; and therefore is satisfied to negotiate with these Lords States, as he does by these presents, a perpetual peace, on the conditions hereinafter described and confirmed.

It is obviously difficult for a population as large as that of our city suddenly to unite and arm itself. Good opportunities are rare: therefore when they occur, it is an act of prudence and great magnanimity to accept them. If you only are clear-sighted enough to recognize it, you will see that God has already delivered you into the hands of good fortune.…

And have no fear, fellow Neapolitans, of [the Spaniards’] power, for they allowed themselves to be expelled from the seven provinces of Flanders [sic] by Dutch fisherman, and from Portugal on their frontiers; and though on each occasion they were supported by your forces, they were powerless to resist. What, then, can they do without you, against you?

The most common idea that is spreading among the people [of Paris] is that the Neapolitans have acted intelligently, and that in order to shake off oppression, their example should be followed. It is understood, however, that allowing the people in the streets to shout aloud their enthusiasm for the revolt of Naples has caused great inconvenience. Therefore measures have been taken to prevent gazettes from reporting further on it.

The 1640s were especially trying for the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty. Aside from the ongoing challenge of ending the long and costly war with his rebellious provinces in the northern Netherlands, Philip IV was faced in 1640 with two new revolutions: in May, the principality of Catalonia, which on the commercial strength of Barcelona was the most important part of his Aragonese possessions, rose up in revolt; in December, the kingdom of Portugal, which had been cobbled into the composite Habsburg state in Iberia and Italy some sixty years earlier, declared its independence, taking with it a vast array of colonial interests. After an unsuccessful military campaign to subdue Barcelona as well as a diplomatic failure to prevent a Catalonian alliance with France, the Habsburg regime in Madrid appeared to be incapable of mounting even a token resistance to the Portuguese secession. Meanwhile, although the effective loss of Portugal had simplified some of the sticking points in negotiating peace with the Dutch, it was not until 1647 that a preliminary treaty, formally recognizing the independence of the Dutch Republic, was completed in the Westphalian city of Münster. Thus even before the Peace of Münster could be ratified and officially promulgated (1648), a spectacular popular revolt in Naples in the summer of 1647, paired with several others in Sicily, threatened even more serious damage to Philip’s dynastic house of cards. Surely all of this opposition merely confirmed the English ambassador’s belief, expressed as early as 1641, that “the greatness of this monarchy is near to an end.” [1]

Yet the tribulations of Philip IV were hardly unique. At the same time that Philip was being confronted with the obvious limits of his autonomy as the sovereign of a composite monarchy in the Mediterranean, the Austrian Habsburgs were coming to grips with the limits of their imperial ambitions in Germany. Though imperial forces had enjoyed considerable success and Ferdinand III had entered the initial negotiations to end the Thirty Years’ War boldly by claiming to speak for the empire as a whole, he had to negotiate alongside and with many of his nominal subordinates and was eventually forced to acknowledge the sovereignty of the constituent units of his empire in the Peace of Westphalia (1648). Meanwhile, the same English ambassador who observed the decline of the Spanish monarchy saw his homeland engulfed in civil war (1642–1649) and his own sovereign executed before the decade was out. And the same French monarchy that had sought to take advantage of Spanish troubles in Barcelona, Lisbon, and Naples found itself under direct attack at home during the so-called Fronde, which began in earnest in 1648 and forced the young king, Louis XIV, to flee Paris. In an imaginary political commodities market around 1650, then, the value of princely futures in general would surely have been depressed; in fact, given the evidence most readily at hand, only the most adventurous of investors were willing to risk a great deal on new investments in the future of monarchical or imperial consolidation.

The simultaneity of so many serious challenges to the sovereign claims of existing regimes has spawned a sizable literature regarding what is usually called the Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. R. B. Merriman ([1938] 1963) first explored the similarities and connections among “six contemporaneous revolutions” at midcentury, but in the 1950s and beyond the “crisis” debate, spawned by Eric Hobsbawm and H. R. Trevor-Roper, paid relatively little attention to these political conflicts, focusing instead on questions relating to the characteristics of a more general social and economic crisis of which Merriman’s “revolutions” were said to be symptomatic (Ashton 1965; Parker and Smith 1978). Before long the crisis metaphor itself became the focus of attention as a new generation of scholars found ever more crises to explore, either in other dimensions of the mid-seventeenth-century European experience or in other decades, reaching all the way back to the early sixteenth century. Eventually, T. K. Rabb (1975) suggested that the original crisis of the mid-seventeenth century might most usefully be seen as merely the climax of a much grander social, political, and cultural “struggle for stability” that began in the early sixteenth century and finally gave way to the relative stability of Europe’s ancien régime by the 1680s.[2]

For our purposes, it is essential to refocus on the political dimensions of the mid-seventeenth-century crisis and to situate these multiple challenges to Europe’s dynastic princes within both the changing spaces of European politics and the larger history of popular political practice. Looking prospectively from the end of the sixteenth century, this chapter examines the constellation of political conflicts that finally yielded to a relatively durable pattern of religious and political settlement in the second half of the seventeenth century. I argue that the political action of ordinary people was instrumental in transforming the composite states created by aggressive princes nearly everywhere in Europe, not just in those areas where a broad-based Reformation coalition had succeeded in implanting Protestant churches in the sixteenth century. This is not to say, of course, that popular political actors were everywhere (or even anywhere unambiguously) triumphant; rather, surveying the revolutionary conflicts that constituted the midcentury crisis, I highlight the variable, transient, and often ambiguous outcomes of the religious and political struggles. My goal, in proceeding from one region to the next, is to describe and account for the complex interactions of rulers and subjects in a number of revolutionary situations and to suggest how the outcomes of these struggles structured, in turn, the political opportunities of ordinary people under Europe’s new regime.

| • | • | • |

The End of the Religious Wars?

At the beginning of the seventeenth century there was credible evidence to suggest that the dangerous and destructive cycle of “religious” wars that had attended the reformations of the sixteenth century might actually be coming to an end. The most promising signs of hope first appeared in 1598 with the Edict of Nantes in France and the death of Philip II in Spain. On the face of it, the Edict of Nantes might have been just another in the dismal series of merely temporary truces that had marked the intervals between no less than nine wars in France, but two developments signaled that the depoliticization of the question of religious difference might actually be possible. In the first place, a special system of courts proved to be remarkably effective in limiting the scope of conflicts between Protestants and Catholics regarding the practical implications of the edict’s formal recognition of religious difference.[3] But equally important, Henry IV apparently convinced enough of the elite leaders on both sides of the Protestant/Catholic divide, with the help of liberal subsidies and pensions, to accept him as the guarantor of their political interests; consequently, the risk of personal losses in a revived war appeared to be greater than the political costs of continuing an initially unsatisfying peace. By 1610 the peace in France was secure enough to survive even the assassination of Henry IV. Similarly, after so many years of Philip II’s stubborn refusal to accept any kind of compromise with Protestantism, the ascension of Philip III to the Castilian throne brought with it the possibility of compromise in the Spanish Habsburgs’ very costly war with their rebellious Dutch provinces. Though a permanent peace that resolved the especially thorny issues of colonial competition still proved to be elusive, an armistice in 1607 yielded to the Twelve-Year Truce (1609–1621) by which, for all practical purposes, Spain recognized the sovereignty of the United Provinces.

Subtler, though no less important, signs of hope for an enduring religious peace were also visible within the German-Roman Empire, the heartland of the first phase of the European Reformation (see Munck 1990; Hughes 1992). The significant question there was whether the apparently inflexible and unambiguously authoritarian principle of cuius regio eius religio, as articulated in the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, could accommodate either renewed contestation between particular subjects and rulers over matters of religious choice and identity or ongoing changes in the larger confessional map of central and eastern Europe. With regard to the latter, by the turn of the century a series of princely conversions had demonstrated the resilience of the agreement, even when princes like the elector of the Palatinate embraced Calvinism instead of Lutheranism, which was the only officially recognized Protestant sect under the Augsburg settlement.[4] As for ongoing conflicts between subjects and rulers, a combined municipal and ecclesiastical revolution in the East Frisian town of Emden in 1595 preserved the local Calvinist church and liberated the municipal council from an aggressively Lutheran count (Schilling 1991); it demonstrated that broadly popular challenges to the territorial prince’s exclusive claim to the ius reformandi would not necessarily lead to a new cycle of war. Similarly, the successful resistance of the Lutheran city of Lemgo to the count of Lippe’s attempt to impose Calvinism in the 1610s highlighted the extent to which the authoritarian claims of Germany’s rulers could be openly challenged by determined subjects within the framework of the empire (Schilling 1988). Meanwhile, Protestantism seemed to flourish informally even in the patrimonial lands of the Austrian Habsburgs under both Maximilian II (1564–1576) and Rudolf II (1576–1612). Although the latter successfully expelled Protestant pastors from Vienna, his authority nearly collapsed altogether when he tried unsuccessfully to promote the Counter-Reformation in Hungary; in 1609 he was even forced to grant the Letter of Majesty in Bohemia, which entailed not only important political concessions to the Estates of Bohemia but also religious guarantees to the many Protestant groups that were thriving there (Polisensky 1971; Evans 1979; Eberhard 1995).

If, taken together, these were signs of hope for a general religious peace in Europe, they were equally signs of the fragility of peace. Religion and politics remained thoroughly intertwined, and religious difference retained its potential as a marker of political enmity as long as rulers entertained exclusive claims to cultural sovereignty or significant numbers of their subjects actively sought the exclusive reformation or counterreformation of whole polities. Thus the temporary absence of religious war on a large scale merely suggests the temporary absence of comprehensive Reformation and Counter-Reformation coalitions willing and able to press mutually exclusive claims to religious hegemony (see fig. 6); and, for the time being at least, religious dissent and political conflict on the local or regional scale did not automatically lead to a new round of religious war on a broader scale. More precisely, the relative peace of the early years of the seventeenth century appears to have been predicated on the momentary willingness of Europe’s princely rulers—rooted as often as not in political and military necessity—to moderate their attempts to consolidate their power over matters of religious conscience. Indeed, it is telling that when the elector of Brandenburg officially embraced Calvinism in 1613, he restricted the scope of this Second Reformation to the court for the sake of peace with his overwhelmingly Lutheran subjects. But on the other side of the same coin, when the Austrian Habsburgs in alliance with the papacy sought to overturn the political and religious compromises they had been forced to accept in Bohemia in 1609, it was enough to precipitate after 1618 yet another round of religious war. This cluster of extremely destructive conflicts, known retrospectively as the Thirty Years’ War, eventually involved all of the great powers of Europe before it was resolved by the relatively durable treaties signed at Münster and Osnabrück in 1648 (see Parker 1984).

What made the Thirty Years’ War a “religious” war was hardly the purity of religious motives among the many combatants. Rather, like the religious wars that preceded it—from the Peasants’ War and the Schmalkaldic War in Germany through the civil wars in France and the Dutch War of Independence—the Thirty Years’ War was specifically religious in at least three ways: (1) it was precipitated by significant challenges to an established ruler’s claim to a comprehensive political and religious sovereignty over his subjects; (2) it invoked and mobilized large-scale, armed coalitions within the empire that were identified in large measure with the Reformation and Counter-Reformation causes; and (3) an unambiguous military victory for one side or the other potentially promised an equally unambiguous victory for the Protestant or Roman Catholic church in the polities of central and eastern Europe where the battles were principally fought. In this sense, although it is well known that the Thirty Years’ War was fought by military alliances in which religious conviction took a back seat to political and strategic calculation, it is equally safe to say that it revived and expanded the truly “confessional” era in European history during which an uncompromising princely claim to cultural and religious sovereignty became the hallmark of what is often called absolutism (cf. Hsia 1989). By the same token, the compromise settlements that finally brought an end to the carnage in 1648 did not bring an end to the era of religious politics or even to the age of religious war on a more limited scale within specific polities.[5] Indeed, as long as Europe’s rulers were tempted to use religious beliefs and institutions to extend or consolidate their authority over their subjects, religion and politics would continue to be thoroughly entwined.

For our purposes, however, it is important to realize that, even in the territories most directly affected by the Thirty Years’ War, religion remained only one of a very mixed bag of issues that animated popular political action. In the Austrian Erblände,[6] for example, locally mobilized peasant resistance to economic and social subjection at the hands of noble landlords in what is often called the “second serfdom” coalesced into a major peasant uprising (the largest within the empire since 1525) across Upper and Lower Austria between 1594 and 1597 (Evans 1979: 85–100; Rebel 1983). Since the areas of the revolt were also areas where a variety of forms of Protestant worship had largely overshadowed a weakened Catholic church, however, the military defeat of the peasants provided a pretext for the vigorous assertion of the Counter-Reformation in the Austrian countryside in the course of the seventeenth century. Even though there was intermittent popular resistance to wartime exactions, the Thirty Years’ War, like its sixteenth-century predecessors, quickly and effectively closed down most of the opportunities for independent popular political action in those areas most directly affected by it. Thus the Catholic armies in alliance with an aggressive Counter-Reformation clergy succeeded in enforcing the political sovereignty and cultural politics of Ferdinand II—which boiled down to the equation of Protestantism with all manner of disloyalty and the stern insistence on a single-confession state—in Bohemia and the Austrian Erblände in the 1620s; this, in turn, produced massive flows of Protestant refugees comparable to the flight of Protestants from the southern Netherlands after 1585.[7]

The intermixture of religion and politics remained volatile in France and the Low Countries, too, especially with the coming of the Thirty Years’ War, but in both places it failed to reignite the fires of civil or religious war on the scale of the sixteenth century. In France the relative tranquillity of the first two decades of the seventeenth century—retrospectively seen as a “golden age” in French historiography—gave way to more serious political dissension in the 1620s, and once again it invoked elements of the Huguenot alliance. Though the Protestant magnates who led the wars of the sixteenth century had been pacified in 1598, they had certainly not disappeared altogether. Thus when the royal government began seriously to reconstruct the king’s authority by undermining the political concessions of the Edict of Nantes, they encountered serious resistance from some of the political elites whose power was most directly threatened in the Protestant strongholds of the south and southwest. Following the king’s successful attack in 1620 on the county of Béarn, a defiant Protestant stronghold in the Pyrenees, there were a series of piecemeal confrontations in which local Protestant resistance might occasionally hold off the royal offensive, as at Montauban. But the monarchy’s determination was amply rewarded by the Treaty of Montpellier (1622), which prescribed the dismantling of virtually all of the Protestants’ fortified towns (places de sureté). What is remarkable about these encounters is that they failed to invoke or re-create the fully articulated Huguenot alliance of the sixteenth-century civil wars; most Protestant leaders, indeed, seem to have concluded that open rebellion was useless or counterproductive (Briggs 1977: 92–94), while those who did revolt enjoyed very little popular support. An ill-conceived commitment of English support to La Rochelle in 1627 finally provided the royal government with a pretext for a direct attack on this last bastion of Huguenot independence. Yet when La Rochelle finally fell after a fourteen-month siege, the Peace of Alais (1629), which forced the Huguenots to give up the last of their fortresses and troops, nevertheless guaranteed their liberty of conscience. Though severely tested, then, the central compromise of the Edict of Nantes granting Protestants a limited freedom of worship held firm; and for the time being the volatile identification of religious difference with political revolt was once again broken along with the independent military strength of the Protestant magnates. But the Protestants were more dependent than ever on the king’s “protection.”

This is not to say, of course, that the relations between subjects and rulers in France remained tranquil. On the contrary, in 1635 France began a direct and exceedingly costly engagement in the Thirty Years’ War that precipitated a widespread series of both urban and rural revolts including two very significant regional rebellions—those of the Croquants in 1636–1637 and the Nu-Pieds in 1639—and culminated in the Fronde at midcentury (Tilly 1986; Briggs 1989; Bercé 1990). Just as the religious peace had brought ordinary people a measure of tax relief after 1598, the king’s increasingly aggressive domestic and foreign policies in the 1620s and 1630s brought with them a steep rise in royal taxation—both in the taille, the tax on peasant land, and in the aides, the urban excises on foodstuffs and other essential commodities (Tilly 1981, 1986). Widespread evasion combined with corruption to produce only an incrementally small yield on these new taxes at the same time that the determination of the state’s fiscal agents provided the king’s subjects with ready targets for their resentment and opposition. Again the building block of popular political opposition was local mobilization against specific officials and over concrete issues. For their part in confronting these local oppositions, royal officials generally followed a two-pronged strategy of compromise when necessary and violent repression when possible, both of which were intended to limit the scope of popular opposition.

As tax evasion gave way to open resistance, however, and local resistance aggregated into broadly based regional revolts, as it did in 1636 and 1639, the French monarchy was faced with fully articulated opposition coalitions of the sort that had briefly disappeared in the first third of the seventeenth century. What made these opposition coalitions especially frightening and dangerous is that they combined a broad base of popular mobilization with locally significant elite leadership, but what these coalitions generally lacked was the ideological glue, the more experienced mercenaries, and the international networks of support that had sustained both the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation coalitions during the wars of religion. Professing allegiance to the king while attacking “corrupt” officials and “tyrannical” policies, then, the popular armies of regional revolt were in the long run no match for the far more professional and resourceful armies of the king. At this level, too, repression was combined with concession to produce inequalities in taxation that would in turn fuel more and different kinds of opposition another day. Yet in the impressively diverse catalog of “contentious gatherings” that Charles Tilly gives us for five selected regions of France in the 1630s and 1640s, the common denominator remains “the royal effort to raise money for war” (1981: 139; see also tables, 140–143).

In the Dutch Republic religious difference also threatened to return as a salient marker of political enmity and opposition, but in a rather different way. To the extent that the Union of Utrecht represented a religious settlement for this new polity, it privileged the Reformed church as the exclusive public church, but it forbade the persecution of individuals in matters of religious conscience. What emerged in the northern Netherlands, then, was a pluralistic society that afforded religious “dissenters” locally variable opportunities, not only to survive, but in some places even to flourish.[8] Though the relations among the public church, the dissenting communities, and the local officials (who functioned as reluctant referees as much as cultural sovereigns) were often contentious and unstable, it was conflict within the Reformed church—not between confessional groups—that most seriously disrupted Dutch politics on a national scale during the truce with Spain.[9] Two antagonistic factions within the Reformed church, the Gomarists and the Arminians, differed from one another not only in the fine points of Calvinist theology—Gomarus and Arminius were theology professors at Leiden—but also on issues relating to church and state or, as they typically stated it, religion and regime. The Gomarists laid a strong claim to Calvinist “orthodoxy” and favored a “pure” Reformed church with significant disciplinary authority over its members but separate from direct political influence; by contrast, the Arminians espoused a less stringent Calvinism as well as a more open, capacious public church closely allied with and supportive of the republican regime. These issues echoed broadly in the voluminous pamphlet literature of the early republic, and although neither side was connected with a political “party” in any direct way, it was evident already in the negotiations leading up to the truce in 1609 that the orthodox Calvinists—many of them refugees from the southern provinces—favored continuation of the war with Spain with an eye to the “liberation” of all the Low Countries. They accused their more latitudinarian enemies—that is, those who advocated the truce and were a good deal less zealous in the promotion of the “true” reformation of the Church—of both political and religious lassitude (Harline 1987).

During the truce these latent differences over religion and regime became more dangerous and more manifest as the two sides—now called Remonstrants and Counter-Remonstrants—clashed over both the constitutionality and the political wisdom of a proposed “national” synod of the Reformed church to settle the whole range of theological and ecclesiastical issues.[10] This struggle culminated in 1618 with the calling of the Synod of Dordrecht, in which the orthodox Calvinists established unambiguous control of the principal institutions of the Reformed church; its tragic denouement was the trial and execution in 1619 of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt for treason. Oldenbarnevelt had been one of the principal political architects of the Dutch Republic since the late 1580s and the chief advocate of the truce; the authorities who tried and condemned him were closely allied with Maurits of Nassau, son of William of Orange and the heroic military leader of the fledgling republic. The complexity of this difficult and dangerous struggle not only reflects the ambiguous position of the public Reformed church in a pluralist Dutch society, it underscores the peculiarities of the Dutch republican regime. For our purposes it is important to note that ordinary people were very much involved in religious politics at the local level in the sense that their religious affiliations established important limits on the political options available to local rulers, and when they were organized in conventicles, underground churches, and civic militias, they could be an especially dynamic element in determining both the policy and the personnel of local governments. Local rulers, for their part, were often caught in an untenable position between the insistent demands of well-organized groups at home and the pressures of national claimants to power. Meanwhile, the two principal claimants to national leadership, Oldenbarnevelt and Maurits, were, as political appointees, by no means surrogates for the princely sovereignty that by the 1580s had been abjured and defeated; rather, they were the brokers and national symbols of two different and volatile factions of the “regent” oligarchy who claimed the “sovereignty” of the republic by virtue of their membership in a layered system of corporate ruling bodies—the city councils, variously constituted provincial estates, and the national Estates General, which was composed of “instructed” delegates from the provincial estates (see Price 1994).

In this context issues involving religion and regime could become especially volatile when they linked small but zealous groups of orthodox Calvinists through the factional networks of the ruling oligarchy with the military resources commanded by Maurits, the captain-general of the republic’s armies. In many of Holland’s very independent cities popular Counter-Remonstrant (i.e., orthodox Calvinist) demonstrations, often reinforced by official visits by Maurits as stadhouder (formerly the royal governor, now appointed by the provincial Estates), forced the purge of Arminians from the ruling councils. But in the critical case of Utrecht, Maurits deployed troops under his command to purge its municipal council and to disarm a local military contingent outside his control (Israel 1995; Kaplan 1995). In the face of this formidable coalition, Oldenbarnevelt and his allies proved to be no match even where they had solid support at the community level because direct military intervention by the prince tipped the balance in favor of Oldenbarnevelt’s religious and political enemies who eventually dominated the synod of the Reformed church as well as the corporate bodies of the republican regime. In the short term the triumph of the orthodox Calvinists at the Synod of Dordrecht resulted in a purge of the clerical leadership of the Reformed church as well as sporadic persecution of a broad range of religious groups who stubbornly asserted their “dissenting” religious identities through conventicles and underground churches. But as long as the Union of Utrecht remained the touchstone of Dutch politics, the newly purified public church would never be in a position, either ideologically or politically, to enforce an exclusive reformation in the northern Netherlands (cf. Kaplan 1995; Hakkenburg 1996). By the same token, the triumph of Maurits’s military leadership virtually ensured both the republic’s deep involvement in the Thirty Years’ War and the resumption of the war against Spain, but it did not alter the constitutional structure of the Dutch Republic in which Maurits and his successors as captain-general of the union and stadhouders of the various provinces remained public appointees (with extensive patronage and indirect “influence” over factions of the regent elite) rather than “sovereigns” in their own right. Before long, then, the issues of religion and regime ceased to be as volatile when the transient coalition of orthodox Calvinists with the republic’s military leadership began to dissolve under Frederik Hendrik, Maurits’s half-brother and his successor as captain-general of the republic (1625–47).

| • | • | • |

The Spanish Crisis in Iberia: Catalonia and Portugal

Against the backdrop of the Thirty Years’ War in central and eastern Europe and the changing patterns of political contention in France and the Dutch Republic, we are now in a better position to consider the character and significance of the six contemporaneous revolutions that are said to have constituted the original crisis of the midseventeenth century. R. B. Merriman began his survey with the “Revolt in Catalonia” (1640–1652), the “Revolution in Portugal” (1640–1668), and the “Uprising in Naples” (1647–1648), all three within the composite monarchy of the Spanish Habsburgs. To these he added the “Puritan Revolution” in England (1642–1660), the “Fronde” in France (1648–53), and the “Revolution in the Netherlands” (1650). According to Merriman, writing in the 1930s and openly troubled by predictions of “world” revolution, “The causes, courses and results of these six revolutions afford an admirable example of the infinite variety of history. Though contemporaneous, they were curiously little alike; their differences were far more remarkable than their similarities” ([1938] 1963: 89). It will be useful for us to be more precise about the variety; indeed, I should like to treat the first three, along with the urban uprisings in Sicily in 1646 and 1647, as constituting a cycle of protest and revolution within a single composite state and the last three, though not unrelated to one another and to the conflicts within the Spanish domain, as relatively discrete political contests within very different states. This distinction is especially evident and useful, I think, when we approach the seventeenth-century crisis from the point of view of popular political practice.

The Catalan Revolt illustrates the essential dynamics of the challenges to Spanish-Habsburg power in the Mediterranean in that it grew out of resistance to the forceful assertion of royal authority within a constitutionally and fiscally peripheral component of the composite Habsburg monarchy (Elliott 1963, 1970). Though Catalonia was both economically and strategically invaluable to the Castilian core of the Habsburg state, it was constitutionally peripheral in the sense that the Habsburg dynastic succession was predicated on the king’s solemn pledge to guarantee its historic liberties and exemptions (fueros); it was fiscally peripheral in the sense that it contributed nothing directly to the defense budget of the Castilian-dominated composite. Such an arrangement produced obvious frustration at the center of this extensive and very diverse composite; from Madrid it was possible, if not always realistic, to dream of a unified kingdom of Spain to replace the diverse sovereignties that had been accumulated by the dynastic union of Aragon and Castile. In an attempt to move in that direction and to consolidate his extractive authority, Philip IV (or perhaps more accurately his chief minister, the count-duke of Olivares) developed the so-called Union of Arms according to which the royal government in Madrid imposed new obligations on its peripheral provinces in the name of a common defense. Specifically, this entailed the imposition on the Catalans of both new taxes and new obligations to billet the king’s infantry regiments (tercios) in 1639 and 1640. Amid formal and largely unavailing protests by the principality’s indigenous elites, however, a broad-based popular mobilization in the spring of 1640 proved to be the most dynamic element in an otherwise familiar standoff between the central government and its nominal agents of indirect rule on the periphery.

The roots of the popular mobilizations in Catalonia in 1640 were, like popular mobilizations everywhere, locally variable. In the more mountainous and remote parts of the principality where the movement drew its original strength, it was rooted in traditions of peasant mobilization reaching back to the so-called syndicates of the fifteenth-century civil wars and to the networks of rural bandits more recently active in Catalonia (Elliott 1963: 421–422). In the first week of May, well-armed and well-organized bands of such rustics, summoned quickly to action by the ringing of church bells, challenged the government’s attempts to billet troops in several towns and villages in the provincial interior, forcing the tercios to retreat to the coast. But when the viceroy attempted to punish the rebels by sacking the town of Santa Coloma de Farnes, he not only failed to intimidate them but also effectively transformed a localized resistance into a more generalized uprising. One official captured the seriousness of the political situation in early May just before the sack of Santa Coloma:

When the bishop of Girona excommunicated the entire tercio responsible for the official retribution in Santa Coloma (which included the gratuitous destruction of a church in the village of Riudinarnes), it was relatively easy for the rebels to proclaim that they were fighting for God and their churches; their enemies could quite simply be identified as the hated soldiers, the king’s viceroy, and “all the traitors,” presumably including the officials and superior classes who had showed themselves to be “devoted to His Majesty’s service” as well as those who “gave shelter to the soldiers” (Elliott 1963: 431).All this land, by which I mean the peasantry, is so disaffected that I doubt that there are any who do not feel the same way as those of Santa Coloma. And the common people of this town [Girona] are by no means well-disposed. It is true that the town councillors and the superior classes are showing themselves to be devoted to His Majesty’s service, but few of the clergy and members of the religious orders are similarly inclined, and most of them follow the voice of the people. (Quoted in Elliott 1963: 422)

The popular initiative is once again evident when the resistance movement spread from the countryside to the cities, where riots in the poorer districts typically combined with incursions of armed rebels from the countryside (ibid., 464–465). Amid rumors that the tercios were about to attack Barcelona, for example, a band of rural rebels entered the city on May 22 and quickly emptied the prison of both its political and its criminal inmates before they were convinced to leave again by the local bishop. On May 26, university students, aided by the armed rustics who once again entered the city, attacked the houses of several officials and wealthy residents, announcing “Death to traitors and bad Christians.” Meanwhile, the tercios besieged by armed rebels at Blanes, were forced to retreat to the fortified garrison town of Roses in the neighboring Rosselló (Roussillon). Finally, on June 7 yet another group of rural rebels entered Barcelona and, aided by many of the inhabitants and abetted by the refusal of the guild companies to oppose them, precipitated five days of riots, attacked the so-called traitors, and even killed the viceroy as he attempted to flee the city. With all the king’s ministers in flight or in hiding and the central government’s authority in collapse, it fell to Barcelona’s civic elite to organize civic militias to restore order. By the May 11 it appeared to the syndic of Manresa “that we are in paradise in contrast to the state we were formerly in.…It is now considered certain that the soldiers of the king are no longer in Catalonia. There is not much fear that they will come back for the time being, and it is hoped that they will also leave Rosselló, where they are at present.” Before long, the king’s troops were also under attack at Perpinyà (Perpignon), the capital of Rosselló, but in this case, after an all-night bombardment that left half of the city in ruins, the army prevailed.

In short order, then, the popular rebellion first attacked the troops, then the king’s ministers, and finally local officials they saw as traitors. The aggregate of these essentially uncoordinated events spread over some six weeks is what J. H. Elliott has called a “social revolution, beginning in the countryside and spreading to the more discontented elements of the towns” (1963: 462). Yet this was only the beginning of the Catalan Revolt. The popular unrest clearly presented the indigenous governing classes with a very difficult choice: they could either seek to negotiate with Philip and Olivares, at the risk of popular attack, or they could try to harness the popular mobilization to a political revolution against Castilian domination. The second phase of the Catalan Revolt began when the Diputats, a council of six Catalan notables that had long symbolized the historic freedoms of the Catalans, chose the latter course and allied themselves with the popular rebellion. Led by Pau Claris, canon of Urgell, the Diputats were able to tap their extensive networks of family and political clientage to sustain an elite resistance to Madrid in the summer and fall. Those more loyal elites who did not quietly leave were forced finally to choose when, in response to a popular revolt in July in Tortosa (the populace seized gunpowder being sent to the local garrison, attacked local “traitors,” and subsequently expelled the troops altogether), the central government decided to send an army to pacify Catalonia. While the Catalan towns tried to obtain weapons and ammunition for local defense, the Diputats began, with only mixed results, to levy new taxes and to raise a sizable Catalan army while at the same time solidifying an alliance with France. In October, Olivares summed up the gravity of the situation: “In the midst of all our troubles, the Catalan is the worst we have ever had, and my heart admits of no consolation.…Without reason or occasion they have thrown themselves into as complete a rebellion as Holland, for news has today arrived that they have signed an agreement with the French and placed themselves under the protection of that king” (quoted in Elliott 1963: 510).

Despite widespread popular opposition to the exactions of the Castilian-dominated state, raising a Catalan army, indeed organizing the military defense of the rebellious principality in general, proved to be far more difficult than the Diputats had anticipated. Thus when the king’s troops first moved into Catalonia in late November, proclaiming a peaceful mission, they met with little resistance, moving quickly northward from Tortosa along the coast toward Barcelona. At Cambrils in mid-December, however, some six hundred Catalan defenders, who had surrendered to the invading force, were massacred, and when this news along with news of the peaceful surrender of Tarragona reached Barcelona, there was once again a violent popular reaction against the threat of Castilian domination. On Christmas eve a crowd of insurgents, again including forces from outside the city, attacked and murdered officials accused of being traitors, forced open the prisons, and set fire to a number of houses, both in Barcelona and in surrounding villages. The English ambassador offered the following commentary: “In Barcelona there hath happened a great dissension between the magistrates and officers of justice, who would have come to an agreement with the king, and the people that would not.…I do now begin to think that this madness of the common people (who are many, and the nobility and gentry few, not exceeding 600) will throw the Principality into the hands of the French” (quoted in Elliott 1963: 521). In fact, the Catalan ruling elite was deeply divided, and once again the demonstrative action of ordinary people tipped the balance in favor of resistance. The Diputats quickly worked out an agreement with the emissary of France by which the Catalans would declare a republic and put themselves under French protection.

The declaration of the Catalan Republic on January 16, 1641, may be said to have been the climax of the second phase of the Catalan Revolt—the political revolution against the Spanish monarchy—but it was hardly the end of the story. Within a week, in the face of French dissatisfaction with the proposed form of the new republican government, Pau Claris proposed that instead of creating an independent republic, the principality should submit itself to the French monarchy “as in the time of Charlemagne, with a contract to observe our constitutions.” Thus on January 23 the elite leaders of “revolutionary” Catalonia replaced one aggressive “prince” (Philip IV) with another (Louis XIII) in the fervent hope that this would preserve their historic privileges. On January 26 the French alliance did pay an immediate dividend when a combined Catalan-French force defeated Spanish forces under the marquis of los Vélez, but before long the French armies became an occupying force, both provoking and repressing anti-French riots. The French king also appointed his own viceroy, and the governance of the principality was carefully concentrated in the hands of a small group of French supporters.

In retrospect it is certainly tempting to declare the Catalan Revolt a bitter disappointment, if not a complete failure, especially by the definitional standards of modern social and political revolution. But we will do well to recognize how effectively the Catalans protected their fueros by playing one dynastic state maker off against another. Indeed, even after a very destructive decade at the crossroads of the Spanish-French military rivalry, the Catalans were “reunited” with Spain on October 12, 1652, under the very terms they had demanded at the beginning: Philip IV agreed to a general pardon and promised, as count of Catalonia rather than as king of Spain, to preserve the principality’s constitutions. We will also do well to remember that the rebels of Holland, with whom Olivares aptly compared the Catalans, also actively sought a replacement sovereign and toyed with English “protection” under the earl of Leicester before they finally backed into the formation of an independent republic. In fact, from the perspective of early modern popular politics, it is important to recognize how thoroughly familiar the political dynamics and the eventual settlement of the Catalan Revolt actually are even though they do not involve religious allegiance as a critical marker of political enmity.[11]

At bottom, the Catalan Revolt is familiar because it involves so clearly the triangulated set of political actors that was the characteristic legacy of dynastic or composite state formation (see fig. 2): national or princely claimants to power (plus their agents), indigenous or local ruling elites, and ordinary political subjects. Although political alignments between aggressive princes—with often urgent fiscal and military needs—and local rulers—the jealous guardians of historic privileges that were the basis of their position locally—were nearly always uneasy and contentious, they nevertheless consolidated the power of local elites vis-à-vis their local populations (fig. 2b). This pattern of elite consolidation was clearly ruptured in Catalonia as a result of popular political action that forced the local elites to choose between royal political favors and local solidarities. When an important faction of the Catalan elite openly chose the side of the popular resistance, it opened up a revolutionary situation that entailed the possibility of a local consolidation of power under an independent Catalan republic (fig. 2a). But the urgent need for military protection against the king’s armies quickly resulted instead in what might well be called a coup d’état in the sense that one very powerful prince replaced another and quickly consolidated his power in conjunction with a faction of the local elites with whom he had struck an alternative dynastic bargain. As the power of both of the contending princes ebbed in the course of the next decade, however, the “restoration” of 1562 returned Catalonia to a version of the status quo ante.

Clearly the Catalans did not challenge the aggressive claims of their dynastic prince in a vacuum. In fact, neither the vigor of the central government’s political provocations nor the relative success of the Catalans’ reactions is comprehensible without reference to Spanish-French competition and war making on a European scale. Meanwhile, the Catalan Revolt dovetailed with other challenges to Spanish-Habsburg rule in Portugal, Italy, and even the New World.[12] What made these conflicts similar and bound them together as part of a single crisis was the fact that they were all provoked by the king’s attempt to enforce the Union of Arms, which greatly increased the fiscal and military demands of the Castilian core on the composite’s peripheral provinces. Yet the differences in their outcomes will help us to understand both the dynamics and the consequences of early modern revolutions.

On the face of it, the revolution in Portugal seems very different from the Catalan Revolt because it resulted in the permanent separation of the kingdom of Portugal from the Habsburg composite state (Elliott 1991). But it is important to acknowledge their structural similarities at the outset. Though Portugal had not been part of the Habsburg composite as long as Catalonia, both were, from the perspective of the Castilian core, constitutionally and fiscally peripheral provinces whose advantages were clearly threatened by the proposed Union of Arms. In addition, because of the pattern of elite consolidation that characterized the Habsburg composite in Portugal as well as Catalonia, it should not be surprising that the initial impetus for open resistance to the king’s policies came from below. Indeed, as early as 1637 the government’s attempts to raise a substantial fixed revenue from Portugal for the defense of the country and the recovery of its overseas possessions awakened serious popular discontent, with riots reported in Évora and other cities. As in Catalonia, too, the popular movement was reportedly abetted by the clergy, and the French government even hoped to take advantage of the unrest by establishing contact with the leaders.

The interaction between the Catalan and Portuguese challenges to Castilian domination became evident in the fall of 1640 when the government in Madrid sought to mobilize for a military offensive against Catalonia. Though the Portuguese elite had appeared to remain loyal to Philip in the face of popular protests, they began to defect when the sizable nobility was called to military service in the campaign to subdue Barcelona. Suddenly the carefully cultivated alignment between the Spanish Crown and the Portuguese elite began to unravel, and with the defection of the duke of Braganza, who was willing to come forward as pretender to the Portuguese throne, it was possible to put together a formidable, if informal, local coalition against Philip IV (Elliott 1963: 512–519). On December 1, 1640, Portuguese conspirators broke into the palace of the duchess of Mantua (the official representative of the Spanish monarchy), killed Miguel de Vasconcellos (the hated symbol of Spanish authority), and expelled all Castilians (the principal agents of Spanish control) from Lisbon. Having thus declared their independence from Madrid, the populace of Lisbon jubilantly acclaimed the duke of Braganza as King John IV the next day—this at the same time that the marquis de los Vélez was slowly advancing on Barcelona. Only later, in January 1641, did the Portuguese Cortes formally ratify this popular acclamation and remove the Spanish garrisons from the rest of the kingdom. Distracted by events elsewhere, especially in Catalonia, Philip IV’s government did not even undertake a serious effort to regain Portugal until 1643, and the Portuguese, despite a relatively undisciplined and poorly equipped army, easily defeated the Spanish troops at Montijo in May 1644. The war flared up again briefly in the 1650s and 1660s, but it was not until 1668 that Spain recognized Portuguese independence (Merriman [1938] 1963).

Though the relatively bloodless establishment and successful military defense of a new monarchy in Lisbon may seem less than revolutionary today, the revolution of 1640 in Portugal may be considered an especially clear example of “successful” revolution within a late medieval composite monarchy. In the midst of a more general crisis of authority within the Spanish-Habsburg state, popular unrest that implicitly challenged the authority of local elites as well as a distant monarch created an unanticipated opportunity to form a broad-based revolutionary coalition united by its resentment of increased exactions by easily identifiable outsiders. To be sure, the new “revolutionary” government was deliberately modeled on historical precedents, but neither the dynasty nor the popular-based revolutionary coalition that established and sustained it can be considered a simple re-creation of a medieval past. What is more, both the popular and the elite elements of this coalition may be said to have achieved significant and satisfying results—for example, the elimination of the new fiscal demands and the removal of rival Castilian elites—without the long-term sacrifices and setbacks of the Dutch or Catalan wars for independence. Yet in the final analysis, the Portuguese revolution clearly lacks the excitement and narrative drama of the Catalan and southern-Italian revolutions between which it was sandwiched in time.

| • | • | • |

The Spanish Crisis in Italy: Sicily and Naples

The high drama and political danger of the southern Italian revolutions are due especially to the power and dynamism of popular mobilization that threatened the relatively stable political alignment of local rulers with their distant prince. Though the kingdoms of Sicily and Naples were geographically less proximate to the Castilian core of the Spanish-Habsburg state, they contributed more, fiscally and militarily, to the welfare of the composite than either Catalonia or Portugal. Indeed, by the seventeenth century southern Italy, Naples in particular, had become an especially critical element within the complex system that sustained the Spanish military machine, not only in the Mediterranean but also, via the fabled Spanish Road across the Alps, in Germany and the Low Countries.[13] To be sure, both kingdoms had been cobbled into the Spanish composite in 1504 with constitutional limitations on their distant sovereign, but the consolidation of local elite power that was typical of such bargains had worked especially to the advantage of the landed nobility; not only did the nobility dominate local institutions of government, they were among the principal investors in local government debt that supported Spain’s military operations abroad while they were exempt from the excises on basic necessities that were dedicated to the repayment of these government obligations. This meant that the sizable urban populations—Naples at 300,000 and Palermo at 150,000 were among Europe’s largest cities—were both vulnerable to fiscal exploitation and politically isolated.

In both Sicily and Naples the revolutions of 1647 grew out of one of the most basic interactions between early modern rulers and their urban subjects: the so-called food riots occasioned by apparently arbitrary or unjust governmental decisions regarding the price of staples like bread. Since the price of basic foodstuffs was directly related to the burdensome excises by which these governments taxed their urban populations, protests over the price and availability of food easily dovetailed with more general attacks on tax collectors or demands for the repeal of burdensome exactions and unjust regulations. Inasmuch as most local rulers had insufficient means to quell such episodic events as food riots and local tax protests, they were often obliged to make temporary concessions such as subsidizing the price of bread in times of dearth or even repealing taxes that were identified as particularly irksome. Repression and exemplary punishment, if it occurred, usually attended the arrival of troops from outside the community (cf. Beik 1997). In both Palermo and Naples, however, these almost routine interactions issued into obviously revolutionary situations that threatened to displace both the local rulers and the larger pattern of elite consolidation of which they were an essential part.

In Sicily the first food riots took place in Messina in the fall of 1646; these were suppressed by Spanish troops and the leaders executed, though the government also supplied more food (Koenigsberger 1971b). In May 1647, however, similar protests over the price of bread in Palermo quickly developed into a massive demonstration at the Spanish viceroy’s palace: “Long live the king and down with taxes and bad Government.” The demonstrators also broke open the prisons, freeing some six hundred inmates, burned the gates of the palace, and warned the archbishop not to oppose their movement. Soon this popular mobilization, apparently under the leadership of a miller, focused its attacks on the treasury and tax offices, demanding in particular the abolition of the five gabelles, the excises on grain, wine, oil, meat, and cheese. Apparently lacking the means of immediate repression, the viceroy made impressive concessions: he restored the price and quality of bread, abolished the excises, issued an amnesty for the attack on the prison, deposed the local senate, and granted the artisan guilds the right to elect two senators. Soon the guilds were taking over the city’s fortifications and restoring order; the leaders of the original food riots were, however, tortured and executed. On May 25 the viceroy tried belatedly and unsuccessfully to introduce Spanish troops into the city, but as H. G. Koenigsberger suggests, “the guilds remained in control of the city, and for the moment the government was too weak to take decisive counteraction. The nobles, solidly behind the government, retired to their country estates” (1971b: 260–261).

In the summer of 1647, parallel revolts enjoying varying degrees of support from local clergy and advancing similar demands against Spanish taxation occurred in other smaller cities such as Girgenti, Syracuse, and Cefalù, though Messina, which had earlier seen the repression of popular protest, remained squarely in government hands. Meanwhile, in Palermo, the leaders of the guilds began to press for further constitutional reform; as one contemporary observer reports, “with truly unspeakable audacity they began to treat of the reform of the city, not knowing how to govern their own house,” and to formulate new capitoli (laws) for the city (ibid., 1971: 262). In August, amid reports of the sensational revolt in Naples in July, a new wave of popular mobilization, rooted especially in the large tanners’ and fishers’ guilds and led by an artisan who had witnessed the revolt in Naples, attempted to establish a revolutionary government in cooperation with the Spanish government. The movement’s self-proclaimed and charismatic leader demanded the government’s acceptance of forty-nine capitoli, formulated by the guilds, which would abolish the gabelles in the entire kingdom, grant the guilds far greater participation in local government, dismiss most treasury officials, reform legal procedures and codes, and introduce three popularly elected representatives to watch over the work of the local senate. Though the viceroy tried to break the movement by murdering their leader and arresting several guild consuls, he was forced on August 23 to publish the capitoli and release the guild leaders he had arrested. The viceroy was allowed to retain the trappings of his office even though he had obviously lost control of the capital city.

The contemporaneous revolution in Naples was in many ways similar, though more violent and, by extension, more famous. In Naples the popular collective action began with what Peter Burke (1983) has described as a ritualized confrontation, full of religious symbolism, between a more or less spontaneous crowd of protesters and the tax authorities on July 7, 1647. Very quickly, however, the protesters, under the charismatic leadership of a fisherman named Masaniello,[14] confronted the viceroy, reportedly crying “Long live the king” and “Down with taxes.” Immediate concessions were followed by an unsuccessful attempt by the viceroy and the archbishop to restore order, and in angry response, Masaniello called out the civic guard, who numbered in the thousands, were well organized in the city’s wards and were readily called into action by the ringing of bells. At this point the popular mobilization, a great deal more organized, was directed especially at the wealthy officials who, by profiting from the fiscal exploitation of the city, were seen as traitors of the people. The level of violence—the ritualized degradation of victims as well as the systematic destruction of their homes—clearly separated the revolution in Naples from that in Palermo, yet it did not differ a great deal politically in that the militia-led rebels at first sought to establish a revolutionary government with royal sanction.

Even after Masaniello was assassinated on July 16 the rebels made several overtures to the royal government, although they were repeatedly betrayed by the viceroy. At long last, on October 1, a flotilla of ships carrying some five thousand Spanish troops arrived in support of the viceroy, but when they attacked the city, the rebels, now under the leadership of an illiterate blacksmith, claimed a decisive victory. Thus on October 24, 1647, the Neapolitan rebels formally renounced Spanish rule and declared an independent republic. At this point the Neapolitan revolution came to resemble the Catalan revolution, of which its leaders were very well aware, in that they actively sought French protection against a likely Spanish invasion. When timely French support was not forthcoming, the rebellious city finally fell to the Spanish in February 1648. Meanwhile, the revolution in Palermo faded away more gradually as popular enthusiasm for guild leadership and the requirements of constant political vigilance waned; in July 1648 the guilds finally surrendered the fortifications to Spanish troops and the population was disarmed.

These immediately famous conflicts undoubtedly reflected, in some measure, the extremes of conjunctural social dislocation—bad harvests, artificial scarcity due to corruption, famine, migration of dislocated peasants from the countryside—to which many scholars ascribe their occurrence (see esp. Villari 1993). But from the perspective of popular political practice, they can also usefully be seen as a reflection of both exceptional political opportunities and the formidable capacity of popular political actors in a dense urban setting. The opportunities were clearly afforded by the more general crisis of the Spanish-Habsburg state: (1) the state’s fiscal demands combined with its dependence on a privileged rural nobility fractured the critical relations between urban subjects and local rulers; (2) insurrections and war making elsewhere undermined the government’s ability to repress popular dissent; and (3) France was willing to profit from Spain’s temporary weakness by positioning itself as an ally or protector of revolutionary coalitions. Yet clearly the dynamism, the initiative, and the critical decisions in these remarkable sequences came from the popular political actors. In both Palermo and Naples these popular coalitions were not only numerous but also well organized and armed.

That the revolutionary governments failed to last may be said to reflect two fundamental weaknesses of the revolutionary coalitions. On the one hand, both revolutionary movements failed to work out an alignment, though they appear to have tried, with at least a segment of the local political elite; such an alignment might have resulted more readily in a consolidation of local power of the sort that occurred in the Dutch Revolt. On the other hand, they also failed to make horizontal coalitions with other locally mobilized movements and thereby failed to transcend the jurisdictional boundaries of their familiar urban political spaces. To be sure, the revolutionaries in Palermo benefited from the simultaneous and complementary popular political movements in other Sicilian cities, and the Neapolitans surely drew some of their strength and boldness from the massive insurrections that shook the countryside of the kingdom of Naples in the summer of 1647 (Villari 1993). Yet in the absence of political brokers or preexisting networks of organization and communication, these popular movements failed to find a basis for “national” solidarity within the much larger political spaces that they shared as subjects of a common monarch.[15] That they actually aspired to a political alignment with their distant prince against local political elites, whom they accused of treason, may seem naive and fanciful in retrospect, but had they been able to realize such an alignment, they certainly would have moved their political histories in a dramatically different direction (see fig. 2c).

Leaving such eventualities aside, however, it is possible to combine the revolutions in Palermo and Naples with their counterparts in Portugal and Catalonia in a more focused discussion of the political results or outcomes of revolutionary situations within composite states. It is probably safe to say that given the obvious level of popular discontent in Catalonia in 1640 and Sicily and Naples in 1648, the likelihood of revolution was extremely high, but it is equally safe to say that the likelihood that these revolutions would produce a durable republican form of government to replace the monarchy—something that even by modern definitional standards would qualify as a revolutionary outcome—was always remote. In theory, the simple reason is that the conditions that are conducive to the appearance of revolutionary situations are significantly different from those that are conducive to revolutionary outcomes that entail radical transformations of political power. As we have already seen—from the Comunero Revolt in Castile to the War of Independence in the Low Countries; from the Peasants’ War in Germany to the Croquant revolts in France—even transient alignments between popular political actors and a segment of the indigenous ruling elite were enough to produce revolutionary situations within late medieval composite states (cf. Tilly 1993); in exceptional cases, such as we have seen in the large provincial capitals of southern Italy, ordinary political subjects might even be able to precipitate a revolutionary situation on their own. But the closely related cases of Catalonia, Portugal, Sicily, and Naples allow us to discern, more clearly than the sixteenth-century conflicts, the conditions for different kinds of revolutionary outcomes.

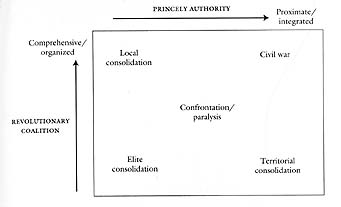

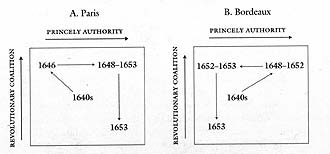

As we have seen in the previous chapters, when local revolutions were repeatedly swallowed up by large-scale religious wars on a national and international scale, the relative proximity and capacity of national claimants (and their armies) are certainly salient factors in determining the outcomes of local revolutionary situations.[16] But the strength of local political alignments was equally important in shaping the historically specific political results. Figure 8 suggests how we might imagine the interaction between the two in accounting for revolutionary outcomes or transfers of power within composite states. In one dimension, with reference to the capacity of princely or central authorities, this figure captures both the structural/geographic variations between different parts of the same composite state—the core as opposed to the periphery—and the more transient variations that occur within them, as when a princely army or flotilla draws near to a regional capital like Barcelona or Naples. In the other dimension, this figure encompasses variations in the social basis of the revolutionary coalition between narrow and disjointed coalitions at either end of the social scale or more comprehensive and organized coalitions within or among communities.

Fig. 8. Dynamics of revolutionary conflict in composite states

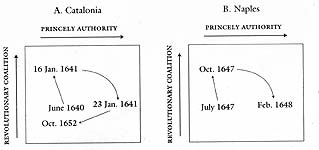

Fig. 9. Dynamics of revolutionary conflict in the Spanish Mediterranean

Within this framework, then, one would account for the fairly straightforward “success” of the Portuguese separation from Castile in terms of both the relative distance or incapacity of the Madrid government and the durability of the broad cross-class coalition against Castilian domination. By contrast, the Neapolitan and Catalan revolutions are more complicated (and for that reason illuminating) in that they both cycled through a series of transient outcomes.

In the beginning of the story in Catalonia (fig. 9a), a socially limited and essentially uncoordinated popular mobilization in May and June 1640—what J. H. Elliott called the “social revolution”—quickly produced ad hoc concessions to popular demands (plus the hasty retreat of the tercios), which in essence confirmed Catalonia’s fiscal and military exemptions. Yet the persistence and spread of popular mobilization forced the defection of an important segment of the Catalan elite and helped to create a truly revolutionary republican government on January 16, 1641. With the rapid approach of two powerful princely armies, however, the Catalan Republic gave way to what might be considered a French coup d’état just a week later. With the gradual disaffection, co-optation, repression, and demobilization of the bulk of the popular political actors under the French regime, Catalonia was finally “reunited” with Spain in 1652 under the specific guarantee of its historic privileges. Against the backdrop of this sequence of transient settlements, even a return to a semblance of the status quo ante may be considered a “revolutionary” outcome in the very real sense that it did not result in the consolidation of absolute princely power in the territorial state that Olivares had in mind; indeed, the defeat of Philip’s “Spanish” pretensions was so complete that, as J. H. Elliott observes from the perspective of Catalonia, “the second half of the seventeenth century was…for the Spanish monarchy the golden age of provincial autonomy—an age of almost superstitious respect for regional rights and privileges by a Court too weak and too timid to protest” (1963: 547; cf. Kamen 1980).

The revolution in Naples (fig. 9b) not only took a different course, but it set the kingdom of Naples on a different historical trajectory after the restoration of the Spanish viceroy. The popular movement, initially an informal coalition based on a common opposition to the hated excises, gained some immediate concessions in July 1647. But over time it tapped the neighborhood networks and organizational strength of the civic militia, it received an assist from simultaneous and widespread peasant attacks on noble landlords in the countryside, and it gained a certain degree of political and military experience. Thus the revolutionary coalition confidently declared its independence from Spain and the creation of a revolutionary republic in October 1647. Still, lacking both elite allies and political connections in the countryside, the municipal revolution disintegrated in the face of superior Spanish force in February 1648. In the process, however, the power of the Madrid government had become a good deal more proximate and directly coercive even though it still depended in practice on some of the traditional forms of indirect rule through a dependent but privileged local elite. Unlike the Catalan experience, then, the kingdom of Naples can hardly be said to have enjoyed a golden age of provincial autonomy in the second half of the seventeenth century.

| • | • | • |

Multiple Revolutions in the British Isles

When we move from the first cluster of Merriman’s “contemporaneous revolutions” in Spain to the “Puritan Revolution” in England, it is clear that we have moved into another historical world. If nothing else, the voluminous historical literature and the lively debates concerning the causes, character, and consequences of the English Revolution are an unmistakable warning against broad generalizations and facile comparisons. Still, the essential political facts with which we are concerned are not in dispute: at the end of 1648 and the beginning of 1649 a faction of the broad parliamentary coalition that had been at war with the English king intermittently for more than six years expelled its enemies from the House of Commons, tried and executed the king, Charles I, abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, and established a Puritan commonwealth (Underdown 1971; Manning 1992). To be sure, these events are so dramatic that they have invited comparison with revolutionary challenges in France in 1789 and in Russia in 1917, and in this company, the English Revolution is often considered the first of the “modern” or “great” revolutions that have become the normative baseline for a succession of academic models of revolution in the twentieth century.

For our purposes, however, it is important to locate the political engagement of ordinary people more precisely within early modern composite states and to recognize the role that religious differences played in shaping the multiple conflicts of which the events of 1648–1649 may be considered the climax. It may thus be useful to take as our starting point John Morrill’s (1984: 178) boldly contentious suggestion that “the English civil war was not the first European revolution: it was the last of the Wars of Religion.” [17] Here I should like to argue, more specifically, that although the English civil war, which began in 1642, may usefully be considered a “religious war,” it can also usefully be considered a revolutionary situation (cf. Tilly 1993: 104–141); its climax in the events of 1648–1649 can, by extension, be considered a singularly “revolutionary” outcome—albeit, like so many others in the seventeenth century, a transient one.[18]

Let us begin with the civil war. Instead of highlighting the nature of social dislocation and the particulars of constitutional crisis within England, Conrad Russell (1987, 1990, 1991) begins his revisionist account of the “causes of the English Civil Wars” by emphasizing the compositeness of the British state.[19] The kings of England had striven for centuries to become masters of all the British Isles—not to mention some major sections of the Continent—but the composite that the Stuart dynasty ruled in the middle of the seventeenth century was in its specifics of relatively recent date (see chap. 2). Following the loss of England’s continental possessions during the fifteenth century and the successful incorporation of Wales within the English monarchy at the beginning of the sixteenth, the Tudor monarchy had once again become a composite with the formal acquisition of the Irish throne in 1543 and the dynastic union, after Elizabeth I, of the thrones of Scotland and England under James Stuart in 1603. Like all early modern composite state makers, James was continually facing fiscal constraints, but having steered clear of direct involvement in the Thirty Years’ War, the financial burdens that Charles I inherited from his father in 1625 were not the worst of his problems.[20]

Whereas the top-down reformation of the Church of England had asserted the king’s ecclesiastical supremacy from the 1530s onward, the steady growth of “Puritan” dissent within England as well as the addition of Catholic Ireland and Presbyterian Scotland presented the new Stuart dynasty with a minefield of ecclesiastical politics. Under James, the Church of England proved to be a remarkably capacious institution, accommodating a variety of religious sensibilities and theological tendencies (Collinson 1982, 1991). But in the 1630s Charles—not unlike his continental counterparts prior to the outbreak of “religious wars” in France, the Low Countries, and Bohemia—began ever more insistently to demand religious conformity from all of his subjects. In England Charles’s particular brand of high church Arminianism brought him face-to-face with a parliamentary opposition that eventually included a broad spectrum of Presbyterians and Independents. Though the often-debated motives and social interests of the leaders on all sides in this escalating conflict were undoubtedly mixed, the factions in this thoroughly divided political elite were increasingly identified, in word as well as parliamentary deed, in terms of their ecclesiastical politics (Morrill 1984). Yet rather than two clearly defined parties, the Long Parliament, which began its fateful sitting in 1640, was composed of a cacophony of political and religious voices. And the political dynamics that transformed a sufficient number of the parliamentary elite of England into “Puritan” revolutionaries—albeit by most accounts reluctant ones—were neither exclusively ecclesiastical, nor narrowly aristocratic, nor parochially English.

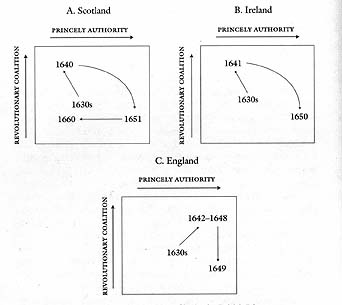

From the broader point of view of the composite monarchy, the British crisis of the mid-seventeenth century clearly began in earnest in Scotland (Stevenson 1973, 1977). There had been periodic friction between Charles and the local aristocratic rulers of Scotland throughout the 1630s, but as Keith Brown (1992: 107) argues, “it was his religious policy which caused most controversy and which provided the popular support for aristocratic action against the king.” Specifically, the forceful introduction in 1637 of a new liturgy (in the form of an Anglican prayer book) as the exclusive basis for Protestant worship was greeted with both a howl of official Presbyterian protest and popular demonstrations in Edinburgh and Glasgow. The adamant refusal of the royal government to compromise in the face of local opposition led in February 1638 to the signing of a national “covenant,” which took the apparently conservative form of a traditional bond expressing loyalty to the king but nevertheless implied a “radical agenda aimed at the destruction of Charles’s authoritarian, imperial monarchy and the episcopal church” (Brown 1992: 112). Though it started in aristocratic circles, the national covenant was popularized by evangelical preaching and found a popular organizational base in conventicles and private churches (Morrill 1990). This growing popular movement eventually forced the uncompromising king to call a general assembly of the Scottish church in November 1638, and dominated by “covenanters,” the general assembly directly challenged the king’s claim to ecclesiastical authority, abolishing the episcopal structure and undoing his liturgical reforms.

As military confrontation loomed in 1639, the covenanters consolidated their control within local parishes and presbyteries—creating rival institutions when they could not control the existing structures—and established a national military apparatus rooted in organizations and mobilization at the local level; a national army, 18,000 strong, was led by soldiers with mercenary experience on the Continent. Eventually, the Scottish parliament also met, without royal permission, in June 1640 and within a matter of days fashioned a new constitutional structure to sustain itself as an independent political force. “The covenanters refashioned government entirely,” Keith Brown writes, “replacing the old model with one based on committees in parliament and the general assembly, and locally in the shire committees of war and the presbyteries” (1992: 119; see also Macinnes 1990). Anticipating attack by royal armies, the Scottish army boldly crossed the English border at the end of August 1640, emphatically defeating the king’s hastily assembled and poorly equipped army.