4. Wills: Palma, Perpignan, and Puigcerdá

The wills explored below come from the short-lived Kingdom of Majorca. This double entity comprised the Balearic islands, especially Majorca itself, and on the mainland the Pyrenean and Occitan holdings in the realms of Arago-Catalonia. The mainland holdings included particularly Roussillon with its capital Perpignan, Cerdanya (modern French Cerdagne and Spanish Cerdaña combined) with its capital Puigcerdá, and the great maritime power Montpellier. To these entities were added claims to Sardinia and later even to the Canaries. King Jaume the Conqueror cut away this politically and geographically artificial assemblage to make an appanage kingdom for his second son, also named Jaume. Though the Conqueror arranged this in his testament of 1262, it took effect only at his death in 1276. Before that transition date, these entities evolved and flourished under the Conqueror, their institutions and languages and commerce forming part of the complex pattern of his realms. Culturally and socially the new kingdom remained in the Catalan-Occitan sphere from 1276 until its loss of sovereignty after 1343. Its political status wavered between de facto independence and a semidependence as a vassal kingdom demanded by the crown of Arago-Catalonia, a situation aptly characterized by David Abulafia as “notional independence.”[1]

A succession of three kings held the new throne: Jaume II (1276–1311), not to be confused with the contemporary Jaume II of Arago-Catalonia (1291–1327), then Sanç I (1311–1324), and finally Jaume III (1324–1343). Each presided from his double capital, in palaces at Palma de Mallorca (then “Majorca City”) and especially Perpignan. Within three years of the new kingdom’s creation, the Conqueror’s son and successor Pere the Great had forced his Majorcan brother to declare his new kingdom a fief of Arago-Catalonia and to abide by various limitations on his sovereignty (1279). Before the Conqueror was a decade in his grave, the same Pere had taken back by force both the Pyrenean and the Balearic centers (1285). International diplomatic maneuvers returned the new fief-kingdom to Jaume II of Majorca (1298), bringing some twenty years of cooperation until the Conqueror’s grandson Jaume II of Arago-Catalonia began his determined effort to unite both kingdoms under his own rule. The final stage of that project came in 1343 when Pere the Ceremonious of Arago-Catalonia declared Jaume III of Majorca a formal rebel and then conquered and reintegrated both the island elements and the mainland.

This complicated political history masked a remarkable commercial success, the strange kingdom prospering astride trade routes between North Africa, France, and Spain, with Atlantic and Italian connections. Besides its role as distribution center, the kingdom developed a strong textile industry. Exporting to all corners of the surrounding map, from Flanders and Castile to Sicily and North Africa, it became a world commercial power. From 1330 decadence and decline set in, hurried along by the Black Death and ruinous wars.

The kingdom held a considerable Jewish population, both on Majorca and on the mainland. Jewish policies of the several rulers varied greatly, from the benign Jaume the Conqueror to the persecuting King Sanç. Circumstances defining the kingdom’s Jewish communities varied more widely, from the immigrant Jewish society mingled with preconquest holdovers at the island’s capital Palma, to the transient Jewish community at Perpignan, top-heavy with working capital, to the more settled community at Puigcerdá. Thus the context of any one testament from the kingdom can differ from other testaments there. The ten wills gathered here derive mostly from the era when Jewish society flourished—four from the 1270s, one from the 1280s, four from 1306, and only one from the less advantaged year 1322. All but one were drawn under Jaume the Conqueror or under Jaume II of Majorca.[2]

| • | • | • |

Palma de Mallorca

Conquered from the Muslims in 1229 and resettled wholesale by Jaume’s subjects, Palma and its island of Majorca afforded its Jews a reasonably pleasant existence for nearly a half-century. From about 1285, however, the rulers encouraged “a steady process of dissociation of the Jews from the Christian community in Majorca City,” both by restrictions and paradoxically by privileges.[3] By the turn of the century, residence within a newly walled Jewish quarter was being enforced—a situation of housing preference thus changing to a policy of compulsion. The general expulsion from nearby France in 1306 naturally caused fear and consternation among the city’s Jews. Then for a decade from 1315 the new king Sanç harassed them, revoking all their privileges, confiscating property including their synagogue, and imposing a massive fine of 95,000 pounds.

These troubles accompanied and may be related to the influx of displaced persons from the 1306 general expulsion from France, which set Jew against Jew. King Sanç reported in 1319 that “roaming alien Jews are flocking here indiscriminately [and] rouse dissension and enmities among Our Jews of the said community.”[4] After the king’s death in 1324 equilibrium was restored, a calm before the late fourteenth-century storm. At the time of the Majorca City (or Palma) testament about to be analyzed, the Jewish community was still appreciated and prosperous, a mixture of Arabic-familiar natives and immigrant families from the mainland now long rooted: “For the larger part the Jews of the said community live by commerce [mercantiliter],” and they were key players in the North Africa to France circle trade.[5]

The long and detailed testament of July 1288 by Zalema, “son of Aaron b. Aarde the Jew” of Palma, had lodged in the archives of the Palma Dominicans.[6] A parchment eleven inches in length, with an elaborated initial, its script is dim and in places illegible or nearly so. In full control of his senses and of “sound memory,” though “seized by illness,” Zalema appoints his wife Maymona as executor to “receive, distribute, divide, and arrange” all his worldly goods. He chooses “burial in the cemetery of the Jews.” Five sous go in alms, presumably on the occasion of the funeral. He leaves his daughter Maazuga, wife of En Horsa the Jew, a legacy of only 10 sous, counting his past financing of her wedding as part of her legacy. An identical bequest and explanation goes to his daughter Axera, widow of Jacob b. Salmó.

Zalema “recognizes” that his son Maymon owns half of “a certain Saracen Negress named Maymona” from Minorca, “whom I bought from Ramon Alber”; the purchase was in Zalema’s own name, but half the price had come from Maymon. (The neighboring small island of Minorca had been conquered a year earlier in 1287 and most of its Muslim inhabitants reduced to slavery.) For Maymon’s legacy Zalema gives one-half of the half of those buildings which “I and my brother Marçoch b. Aaron” share equally “inside the city of Majorca [Palma] fairly close to the buildings of the synagogue.” (Ramon de Trilea, who held these buildings as an allod, had sold them to the brothers.) Zalema also gives his son half of his own half “of some other buildings” which he and his brother Marçoch hold within Palma adjoining the previous set of buildings. For these two complexes an annual rent of 2 morabatins would be owing to Ramon, who continues to hold allodial rights or ownership.

Zalema’s “infant children,” the boy Abrafim and the girl Carima, are each to get 15,000 pounds of Valencian sous from Maymon’s share within three years of Zalema’s death. If Maymon “won’t or can’t” release that sum, his own income from the buildings will be cut to a third of the half until that sum accrues, “to help in the marrying and sustenance” of the two children. Presumably that 30,000 pounds was to give the two their start in life as adults. At 20 sous to the pound (lliura) this came to half a million sous. Since a knight’s fee could be under 400 sous per annum, the legacy amounted to a substantial fortune. By explicit stipulation Zalema’s wife Maymona recovers her sponsalicium “just as is contained in her dowry charter.” In Roman law terms and local custom this wording should mean her dower, the marital gift promised by a Christian groom at the time of marriage but payable to her only at his death. In fact, however, the Christian phrasing here masks the analogous situation of the Jewish ketubah deed given by a groom to his bride, in which he promises a customary sum plus an agreed increment, or tosefet, to go to her at his death. The deed would also describe her own dowry and its increment, which the bride could likewise reclaim when widowed.

Everything not covered by the legacies recited above goes to the two children but under the custody and administration of his wife Maymona, who is also to live from this sum. The arrangement is to continue “until Carima has reached the age of fifteen years, and then her mother is bound to arrange a marriage,” meeting its expenses from the 15,000 pounds. The boy may have been younger than Carima, but in any case the mother was to continue in control of his inheritance (presumably except for his 15,000 pounds) as long as she lived. After Carima’s marriage, and when Abrafim will reach twenty years, he will have the option of taking half of all the goods remaining in Maymona’s control, leaving her the other half until her death.

Zalema then notes that his grown son Maymon “holds in commission [commanda] by charter from me 21 pounds of Valencian reials, give or take a bit [parum plus vel minus].” Maymon must give this to his mother Maymona, who will incorporate it into Zalema’s other goods. The testator also declares that he had already surrendered to Maymon “the aforesaid half of my said half of the said two building-complexes” being awarded above but by a “charter not yet fully accomplished and not come into effect.” He concludes by confirming his intentions, so that if the will “is not valid by right of testament, it may be valid at least by right of codicil or some other right of last will.”

The parchment is dated 6 July 1288 and is signed “Zalema son of the deceased Aaron ben Aarde.” Witnesses are the Christians Pere de Algaire (the Majorcan town Algaida), Arnau Sureda, Pere Martí, Berenguer Amenller (a form of Ametller), Fèlix Màger (?), Pere Oller, and Pere de Vallbona. A line of Hebrew intervenes, followed by the names of the Jews Maymon “Abennono” (with added abbreviating overstroke) and Omar b. Annum. Both these latter surnames recall the Hebrew Hanun that appears in a Judeo-Arabic family in such variants as Ibn Ohnona, Ouahnon, and Wahnun). Salimah or Salāmah was a popular “secular” name used by Jews in the Arabic world, as somewhat echoing Solomon. The notary Gerald Marí or de Marina and the notary Bernat Sant, both of Majorca, put their signa to the whole. For some reason a formal copy was drawn “from the original testament” again four years later, by the hand and corroboration of the Majorcan notary Arnau Sanmartí on 13 June 1292.

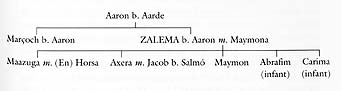

The family structure, without knowing the sequence in which the children appeared, may be represented as:

The names have a Judeo-Arabic flavor as a whole and suggest a family from the massive migration northward under the Almohad rule or a family assimilated after the large Christian conquests over Spanish Islamic lands in this century. The protagonist Zalema was Arabic Salimah, with his brother Marçoch as Marzūq and his father Aaron perhaps with the secular Arabic form Hārūn. His wife Maymona and son Maymon represent Maimūn; two daughters and a slave bear the same name. Maazuga would be a feminine of Marzūq and Axera a feminine of Hebrew Asher; both Arabic Maimūn/feminine Maimuna and Hebrew Asher mean “fortunate.” Abrafim is still close to Ibrāhīm and is a usual Judeo-Arabic form. Carima is the popular Arabic name Karīma; Shlomo Goitein notes that it meant “noble” or “distinguished,” not “sister” as in modern times.[7] The witnesses are Omar (‘Umar) and Maymon (Maimūn). The use of ben or aben in Latinate documents, instead of the genitive or the explicit “son of,” usually signals an Arabic background with an ibn proudly retained; it appears here for Zalema’s father, brother, son-in-law, and both Jewish witnesses, supporting the thesis of a self-consciously “Arabic” circle of family and friends.

Could the Ben Aarde surname be the “Benadi” or Ibn al-Addi Sephardic family? Biblical Hebrew names for Aarde could be Ard and the variants Arda and Ardi, “wild ox.” The Catalan honorific En (akin to Castilian Don), though frequent enough, suggests that Maazuga had married someone well established in the Jewish community. His surname Horsa might be Catalan too, as in the prename Ursí (variant Ors), but Hebrew Hoshaya is preferable. The other son-in-law’s name, Salmó, is simply Catalan Salamó. All these names would have been pronounced orally to the Catalan notary, some of them falling familiarly on his ear, others perhaps to be approximated as exotic. He then tacked on such Latin suffixes as seemed appropriate. The results, as with Zalema and Abrafim, offer clues to contemporary Catalan pronunciations.

| • | • | • |

Perpignan

Richard Emery has intensively studied the Jews of Perpignan, exploring seventeen of the earliest notarial registers still surviving there from over a thousand originally in the thirteenth century. He has culled and transcribed 140 documents pertaining to Jews, among which are five testaments from the years 1273 (two testaments), 1277, 1286, and 1322, respectively. Emery’s focus was on moneylending and the place of Jews in the local economy, so he had no occasion to analyze the five wills or give them prominence. They repay a close look, however, and help round out my own archival findings at Palma and Puigcerdá in the Majorcan kingdom. Perpignan’s Jewish community was unusual in that it was “a new one founded by immigrants who came as moneylenders.” Numerous by 1200, it became by 1300 “one of the largest Jewish communities north of the Pyrenees,” numbering some hundred families or three to four hundred souls. (In its decline, the town itself could still list 2,675 households in 1355, and 3,346 in 1365.)[8] The Jewish community was prosperous, its affluence widely shared by all its families.

The immigration that created and sustained the Perpignan Jewish community stemmed mostly from Occitania, the part of southern France contested ever more in the thirteenth century by Catalonia and the encroaching Franks. Analyzing surnames, Emery finds that barely a third of this population were Languedocians with northern French origins; thus flight from the Frankish expulsions was not the main factor in its evolution. Instead, opportunity drew native Languedocian Jews with both capital and a moneylending background. The rapid growth of Perpignan, especially in the later thirteenth century with its successful textile industries and world marketing, led to “a relative shortage of capital” with consequent rise of interest on loans, creating a magnet for men with capital and ambition in a “migratory generation.” Emery suggests that Perpignan’s Jewish immigration “was in large part a movement of capital seeking a higher rate of return.”[9] If so (and our evidence is partial and tentative), the immigrants seem to have been mostly petty lenders, dedicated to consumer loans to their immediate Christian neighbors, rather than the Jewish investors and long-distance merchants who formed the crown creditors and aristocratic families of ports like Barcelona (though Emery does not take up this line of inquiry).

As the fourteenth century wore on, Perpignan declined from “one of the major Jewish centers of Western Europe”[10] to a harassed and ever poorer settlement, its moneylenders presumably having shifted south once again, out of troubled Majorca and the now inhospitable Frankish Languedoc. During the prosperous period of most of the wills studied here, the Jewish quarter (newly moved in 1250 as the premier call for Roussillon and Cerdanya) was bounded by the modern Rue de l’Anguille, the convent of Saint Dominique behind and below the cathedral, and the Place du Puig.

Of Emery’s five wills, the first comes in 1273 and is the briefest and least revealing. It is minimalist in format and substance. Some of the missing formulaic matter, such as a declaration of terminal illness, lies implicit in six “et cetera” conclusions. The will does not formally name executors, however, and except for witnesses it involves only the immediate family. The testator is Bonisac Fagim, about whom we know nothing; the affluence of his will and the Perpignan context suggest a successful career in moneylending. Bonisac’s wife Bonafília, also Bonafilla, recovers her dowry “as explained in the Jewish nuptial documents” (the ketubah agreements drawn up by the sōfer); she receives nothing else. A married daughter Regina, also Reina, receives a token 12½ Barcelona sous, the equivalent perhaps of a laborer’s weekly wages. Her inheritance rights had been satisfied by “all that I gave her at the time of her nuptials with her husband.”

The unmarried and presumably younger daughter, Bonadona, receives the only other sum explicitly stated, 1,875 Barcelona sous, a workingman’s annual wages for nearly twenty years and therefore a considerable sum. Doubtless much of this sum was meant as dowry, since her brothers are told to support her “from my goods” until she has “taken a husband.” That Bonadona was also a minor is indicated by the appointment of Jucef de Crassa as her “guardian and administrator.” De Crassa or Sagrassa was one of the most active moneylenders in Perpignan, obviously a wealthy man by local standards. This connection, probably familial, underscores the affluent status of Bonisac Fagim’s own family. Sagrassa lived just long enough to complete his guardianship, dying a decade later and leaving his wife Regina as guardian of his own sons, Mossé, Vidal, and Vives. His name is an Occitan toponym, either Grasse or Lagrasse.

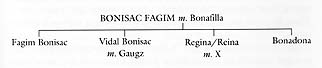

The bulk of Bonisac’s property goes to his two grown sons, Fagim Bonisac and Vidal Bonisac. They are to pay out the legacies and make recompense for any “injuries” (claims or debts) outstanding. The brothers share jointly the status of universal heir. Some Christians but no Jews served as witnesses to Bonisac’s testament: Bernat Bellshom the tailor, Guillem Lenger also a tailor, Guillem Joan a silversmith, Bernat Jaume a tilemaker, Pere Saroca, Pere Jaume a farmer (Catalan hortolà), and Pere Amorós. Do these artisan categories supply a clue to Bonisac’s own social status, or was Bonisac simply their customer or occupational neighbor?[11] The name Fagim, shared by father and son, attracts attention. Obviously it is not a variant of the modern German-Yiddish Fagan or Feigin and probably not a form of Faquim, the Arabo-Catalan title for a savant-physician. (Ḥakīm was both a function or title and occasionally a name in Islam, and many Jews bore it proudly in Christian government service—Catalan alfaquim, Castilian alhaquín.) Irene Garbell argues persuasively that the Sephardic name Fagim involves a Catalan tendency transforming Hayyim, though later she also sees a Provençal pronunciation here on the Catalan-Occitan frontier.

The will as a whole is traditional but minimalist. It does not distribute the testator’s goods or leave legacies; presumably Bonisac had taken care of philanthropies and souvenirs or gifts to relatives by earlier arrangements. The will itself simply restores his wife’s dowry (as Jewish law required), sets aside a suitable dowry for his minor daughter (again as required), formalizes the arrangement by which his married daughter had already recieved her share of his goods as dowry (sealed by a legalistic token gift here), formalizes the arrangement already made with Jucef Sagrassa as his daughter’s guardian, and establishes his two sons as owners of all his property with the duty of supporting their young sister and meeting any unsettled obligations. Since none of this required an accounting of his moneys and properties, we are left with only a general impression of affluence—from the size of the dowry, the status of the guardian, the unusual number of witnesses to lend solemnity, and the marriage of the younger son to a physician’s daughter.

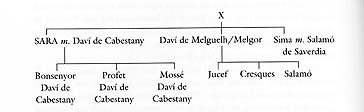

This final bit of information derives from a loan document of October 1283 concerning Gaugs or Goigs (“Gaugz,” or joys), the widow of Bonisac’s son Vidal, herself the daughter of Master Salamó a physician of Narbonne and his wife Regina/Reina.[12] Resolute search through the unpublished sections of Emery’s registers might flesh out the family skeleton or turn up new bones, but the present data allow a basic reconstruction:

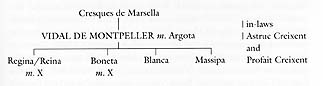

The second of Perpignan’s wills seems more conventional in its verbose length and formulas, but it is not very different in its main concerns. It does afford more details, names and instructs executors, offers options in case of legatees’ deaths, and incorporates both philanthropic and cultural activities. The testator was Vidal de Montpeller, son of the deceased Cresques de Marsella. Though Vidal’s descriptive “surname” reveals his personal origin as from Catalan Montpellier, as his father’s indicates a previous identification with Marseilles, the family was now rooted in Perpignan. Vidal was rather wealthy, as Emery remarks, “worth at least” 6,000 sous or 300 pounds by the evidence in his will. He turns up in the surviving registers only twice before the will itself, however, a “relatively obscure” member of the Jewish community.

Vidal drafted his will in 1273, in the same year as Bonisac, being “of sound mind” and invoking “God’s name.” He establishes as executors his “in-laws” Astruc Creixent and Perfet (“Profait”) Creixent, dispensing them from onerous details of that duty. “They are not obliged to make an inventory of my goods, nor even bound to render an account” to his heirs. They are to incur “no cost or expense” to themselves. Their undertakings will be in solidum, so that either man holds full brief in the other’s absence. As Vidal’s agents they can summon “all my debtors before any tribunal, to recover the said debts,” or they can simply arrange payments or even effect compromises through outside arbitrators. In particular, they are to “sell a certain vineyard that I have in the district of Vernet,” an extension of the city of Perpignan, across the Tet River. The executors also have special obligations toward two of his daughters, in the guise of custodians or guardians. The executor’s surname is the Catalan adjective creixent, for growing or growth, from the same verb créixer (“to grow”) that yields Cresques the testator’s father (“may he grow”). The biblical cognate would be the Hebrew Tzemach.

Vidal had four daughters: Regina or Reina, Boneta, Blanca, and Massipa. Blanca becomes the main or universal heir, a circumstance indicating the lack of surviving sons. Boneta is already married, as is Regina; consequently their share of Vidal’s goods has already been paid out—“all that I gave her at the time of her nuptials” in each case. Regina also gets “my book” containing “the five books of the law of Moses, which she has and possesses in her control.” Boneta receives the rest of Vidal’s library: “all my books which I possess and have by me.” These bequests may suggest some literacy for women in these communities.

The daughter Massipa gets 75 Barcelonan “crowned” pounds. That amount equaled, in a nonexistent money of account but actually in pennies (diners de tern), 1,500 sous of Barcelona, called “coronats” because of the crowned king on their face. The executors, now as guardians, are to invest the sum: “to have and keep and loan it to Christians at interest [ad usuras] until my said daughter takes a husband.” This outcome is not left to chance; the executors “are obliged to provide a husband for my said daughter,” with the advice of Bondia Cohen. Massipa’s odd name is not some Hebrew feminine name such as Mizpa (“tower”) but simply a common Catalan Christian surname, Macip and Massip (Latin mancipium, here as youngster, servant, learner). Massipa is to receive her fortune when she finally marries. Meanwhile the universal heir Blanca “is obliged to provide the said Massipa my daughter with food and drink and clothing and shoes, from my goods, until my said daughter takes a husband.” Blanca can use income from the invested legacy to this end.

Vidal’s wife Argota recovers “her whole dowry just as contained in the Hebrew [ebraicum] nuptial document between me and her,” expressed in morabatins, “so that for each gold piece or morabatin of her said dowry, my said wife is to claim back in payment 8 Barcelona sous and 9 pence, and so on until fulfillment of her said dowry.” As universal heir, Blanca “is to support my said wife in all her necessities, until she will have been entirely recompensed as to her whole dowry.” Argota also receives “all her garments and all my own cloth, and my whole weighing machine that is in my house, except my wine containers and my dying vat that belong to my [universal] heir” Blanca. The “cloth” here seems to be textiles instead of household or personal goods, suggesting in context a mercantile venture. Blanca and Massipa are to have the scales and cloth “until each of them gets a husband.” Though both daughters are under the custody of the executors as minors, Blanca as universal heir must “pay all my debts and the aforesaid legacies.”

Vidal has a final set of conditions. If Blanca dies before Massipa marries, Massipa is to keep 385 Barcelona sous from Blanca’s inheritance, while the rest reverts “to Regina and Boneta in equal shares.” If Massipa will have a husband at the time of Blanca’s death, Blanca’s legacy will revert in equal shares to Massipa, Regina, and Boneta. If Regina should die without a legitimate heir, her share is to go to Boneta and Massipa, “and thus from one to the other survivor in the same way.”

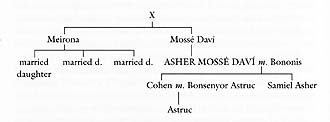

The one public philanthropy is a gift of 6¼ sous to the fund of half-penny alms “for sick Jews.”[13] Seven Christians witness the will, some of them the same as in Bonisac’s: Bernat Bellshom a tailor, Guillem Lenger, Jaume de Brullà (near Elne), Pere Bernadin, Bernat Just a miller (moler for Catalan moliner), Pere Amorós, and Guillem Roer as “invited witnesses” (testes rogati). This obscure but affluent family yields a small family tree:

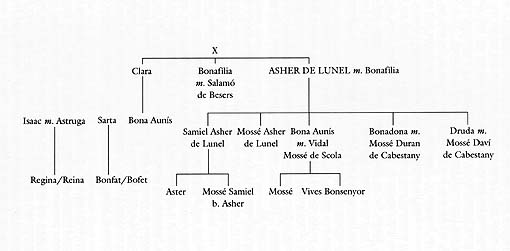

The third Perpignan will comes from the hand of Asher de Lunel, a resident (habitator) of Perpignan. His given name is Hebrew for fortunate or blessed (here in the Hebrew variant Asser), his surname an Occitan town southwest of Nîmes. He appears “regularly” in Emery’s economic documents from 1266 up to his death and last testament in 1277. Ranked by the amount of money he loaned during that time, he is second highest. Asher’s will has a number of unusual features. He leaves 12½ sous, out of love for God, “for the construction of the Tet bridge of Perpignan,” a secular enterprise not near or connected with the Jewish quarter. Christian wills often had legacies for bridges and that cultural climate may have influenced Asher. But such general philanthropy may well have been a practice within the affluent strata of the Jewish community, its oddity here being its inclusion in a will. “For love of God, in remission of my sins,” Asher also leaves the large sum of 625 sous, spread over ten years at 62½ sous per year, to be distributed (presumably to poor Jews) “on the feast that is called, in the Jewish style [iudayce] ‘the huts’ [cabanes]”—that is, Sukkot, feast of the Booths or Tabernacles.

Asher’s will also has a large cast of characters. Before beginning his division of property, he made a “pre-legacy” to each of his two adult sons. Samiel got 625 Barcelona sous under this rubric, while Mossé kept “whatever he had and acquired from my goods by his own industry or by any other manner or means, and whatever loans are owed him in his own name, with documentation or without.” Asher then establishes Samiel and Mossé as “my universal heirs in common, with equal shares in all my goods and in every claim, etc.” The brothers cannot divide their common inheritance for ten years, counting “from my death day.” Samiel receives a special gift, for as long as the inheritance is held in common: 250 sous plus “suitable” board (alimenta) yearly, which would become 625 per annum if he were to marry during that period.

Asher’s three daughters each receive as formal legacy 12½ sous “and whatever I gave her at the time of the marriage she entered.” Each daughter and spouse is named: Bona Aunís or Bonaunís and her deceased husband Vidal Mossé de Scola (or “of the synagogue”), Bonadona and her husband Mossé Duran de Cabestany (Capestang just southeast of Perpignan), and Druda with her spouse Mossé Davin or Daví de Cabestany. Women’s names are more fanciful than men’s in the wills; Bona Aunís is a form of Catalan aunir/unir, “to unite”; Unís is a Catalan Christian surname. Bona Aunís is also equivalent to the Catalan name Bonajun(c)ta, also used by Christians. Druda, a rare but recognized Jewish name, seems to be the Catalan name Trud (“strong”) in the feminine. Bona Aunís’s spouse Vidal Mossé had been alive as late as June 1275, according to financial documents in these registers; he had a brother Belan (a variant of the Catalan masculine name Bel?) and three sons named Mossé, Vives, and Bonsenyor. The Cabestany family, which Bonadona and Druda married into, was already prominent in Perpignan. Other documents show that Mossé was a son of Duran de Cabestany and had three sons named Asher, Bondia, and Jacob. Daví’s name was taken as a variant for David, though it also has classical antecedents. Duran is a Catalan adjective for “steadfast,” used as both a Christian and a Jewish name.

Asher gives his wife Bonafília lifetime possession of “my whole homestead in which I live.” His term mansus instead of domus may carry some pretension to grandeur, an impression strengthened by his description of its site: “on the hill of the town of Perpignan in the quarter of the Jews [callus for call], and fronting along three sides on streets, and along the fourth side on the residence of the deceased Salves de Bellcaire and on the house of the deceased Vidal Bonet.” These last two Jewish neighbors seem to confirm Asher’s affluent status. The Catalan name Salves for one of them, used by both Jews and (as a surname) Christians, relates to the concept “saved” or “safe.” A Jewish moneylender, Salves may have been from the prominent Occitan town Bellcaire, modern Beaucaire (as his Latinized surname suggests), rather than from Catalan Bellcaire d’Urgell or Bellcaire d’Empordà or Belcaire southeast of Foix, though the latter are distinct possibilities. The deceased neighbor Vidal Bonet may have been related to the moneylender of that name who flourished until around 1280, married to “Mayrona” or Meirona and with two sons Mossé and Bonfill. (Catalan Mairona is a feminine diminutive of Meir, as Perona is of Pere.) Asher’s will provides that this corner establishment revert, after Bonafília’s death, to the universal heirs Samiel and Mossé and to their progeny.

The brothers must also provide their mother with daily support at any “appropriately elevated” level (alimenta sua honorifice). Bonafília also keeps “a certain chest she is accustomed to have,” with all its contents, including the 625 sous there. She also gets all his “cloth” (pannos), all the household chests as well as “the documents and other things in the said chests,” the wine containers or wine cellar, “and the other utensils of my house, so that she may use and enjoy [them] during her life,” until they revert at her death to Mossé and Samiel. In a major textile center the panni might well have been cloth held for resale, but contemporary documents commonly used the term also for such household items as bedclothes (pannos lectorum in a 1300 document by the Majorcan king). Of the two brothers, Samiel seems the more distinguished and probably the elder. Emery characterizes him as “among the most active and probably one of the wealthiest moneylenders in Perpignan, judging from the surviving registers.” He had a daughter Aster and a son Mossé Samiel b. Asher; the latter, visible in the registers from 1283 to 1317, became a student of Menahem Meir, the greatest scholar among Perpignan’s Jews. The daughter has the Catalan name Aster, technically different from the feminine Hebrew name Ester (English Esther) but etymologically the same.

Asher remembers his two sisters Bonafília and Clara with a lifetime annuity of 25 sous yearly for each, payable on September 1 of every year. If Bonafília survives her husband Salamó de Besers or Besés (modern Béziers, southwest of Montpellier), “and will wish to move to Perpignan to live together with my heirs and to keep residence with them,” then these heirs Samiel and Mossé must supply her subsistence. In that last situation, however, the brothers may suspend payment of the cash annuity for as long as the residential arrangement continues. To Bona Aunís or Bonaunís, daughter of his sister Clara, Asher leaves 72½ sous, and to his grandniece Bonfat or Bofet (“Boffata”) the daughter “of my nephew [niece?] Sarta a Jew” he leaves 62½ sous. Both of these sums are payable during one year counting from the upcoming Passover or Easter. Neither Christian nor Jewish years began at that time, and the term pascha may reflect either the scribe’s designation, familiar enough to Asher from his business contacts in Perpignan, or the Jewish feast under that common name.

Sarta as nepos would not have been the classical “grandson” (with nephew a possibility) but medieval Latin “nephew” (with grandson a possibility), despite the influence of Catalan nét (grandson) versus nebot (nephew), as is suggested both by usage and the conjunction with the niece Bona Aunís. When the testator Benvenist Samuel Benvenist wished to use nepos as meaning grandson, for example, he added the corresponding Catalan to clarify the Latin word: “nepotum et neptum meorum sive nets e netes.” Medieval nepos could apply to either gender, and the odd name Sarta could be either Catalan male Sarça or more plausibly a form of Sareta/Sarita as diminutive for Hebrew Sara. “Boffata” is the Catalan name Bonfat (good fate or luck) used by both sexes, though here further feminized by the ending.

A final legacy is for Regina or Reina daughter of the deceased Astruga and deceased Isaac, waiving “whatever she owes me by reason of board [alimenta] or in any other way, but without documentation.” Was this an orphaned relative or a nonrelative as object of Asher’s philanthropy? At this point the testator introduces an unusual condition on the whole will: “I wish and decree and order that neither any of my said daughters nor any other person, except only my said wife, can have or be given a transcript or copy of this present testament of mine, nor are my said [universal] heirs bound to give it to them.” Thus Mossé, Samiel, and his wife Bonafília have legal access to the will; but Bona Aunís (or Bonajuncta), Bonadona, and Druda can receive only indirect information from the primary heirs. As befits so solemn a charter, seven “sworn witnesses” sign besides the Jew Vidal Bonfill de Scal: the Christians Guillem Parador the jurist, Guillem Barrau, Joan Martí the shoemaker, Bernat Barrés, Pere Dalmau, Ferran (de) Bonpàs, and Arnau Isarn. The Jewish witness had been a partner with Asher and Samiel in some loan business and with Samiel had been one of the “secretaries” or cogovernors of the local Jewish community.

Taken as a whole, the testament depicts an aristocratic family of means, public-spirited and openhanded, the pious testator firmly in control of business and family. The several bits of information available elsewhere in these registers about the individuals involved confirm this impression.[14] The family emerges from the will as shown in the genealogy on page 88.

A very different kind of will came in 1286 from Sara, widow of Daví or Davin of Cabestany (Capestang), resident of Perpignan. Almost her entire estate goes to the education of Jewish poor children, arranged in detail. Her husband had been a major moneylender together with his sons Mossé and Bonsenyor, unless two men of that same name were prominent then in Perpignan. Since Sara leaves nothing to her immediate family, it is probable that her husband had already funded them, leaving Sara with her dowry and a modest competence. The two sons she chooses to oversee a distribution of dowries to Jewish poor girls seem to add a third brother, Profet Daví de Cabestany, described as brother to Mossé Daví de Cabestany. Her executors are the same Profet plus Duran de Melguelh/Melgor (modern Melgueil), a resident of Béziers.

A peculiarity of Sara’s will is that she reckons her legacies in the money of Melgueil, native here until largely displaced by the Barcelona sous under pressure from the king of Aragon. This may reflect her advanced years and attachment to past ways as well as a lack of business adjustments such as her husband might have made. Sara leaves 200 of these sous to her sister Sima, wife of Salamó de Saverdia, and 20 more to Blanca, the daughter of Abraham de Magalas, toward her marriage (maritamentum). Sima may be the Judeo-Aramaic name Sima or “treasure” or else the Greco-Latin name Sima/Cyma, “to sprout” or flourish. Sara also leaves 500 sous to the sons of her brother Daví de Melguelh/Melgor, that is, her nephews Jucef, Cresques, and Salamó, divided into equal shares. Her condition for this canny gift is “that my aforesaid executors keep and loan the [sous] at interest during the life of my said brother, and that all interest made with them be given and handed over every year in the life of my brother to my said brother to do with as he will.” This stipulation argues that the three nephews were minors and likely to remain so for a while. At the brother’s death, the funds were to go to the nephews directly.

No universal heir has so far appeared, but Sara now names him: “I establish as my universal heir my God.” Sara spells out the practical terms of this unusual choice. “The remainder of my goods are to be given and distributed, for love of God, to poor Jewish girls for marrying them off [ad maritandum].” The administrators of this legacy are to be her two sons, Profet Daví de Cabestany and Mossé Daví de Cabestany. Only Profet is an executor of the will as such, Mossé here supplanting the executor Duran, perhaps because Duran must exercise his general oversight from his residence at Béziers while this specific task requires local contacts and action. The proper executors, however, receive “full agency to ask, demand, and receive all my goods, according to their understanding.” They are to pay out all the legacies “within a half year after my death.” Seven Christians sign as sworn witnesses: Pere de Òpol a butcher, Guillem Costa a butcher, Pere de Braya a farmhand, Sanç de Vilallonga, Domènec de València (or de Valença, modern Valence on the Rhône), Bernat de Cornellà a glover, and Pere Quer-Rubí (or if the name form is genitive, Querub). The oppidum, or fortified area, as toponym of the first butcher, may simply be the new Castell Reial, which included among its many services a butchery.[15]

Sara’s testament belongs in the category of those going beyond the domestic sphere to proclaim a public philanthropy on a considerable scale. Concern for dowries or dowry increments was general with both Christians and Jews, but its placement so prominently within a Jewish will does seem unusual. Sara’s designation of God himself as universal heir may be unique in Jewish testamentary expression. Does this reflect a scribal scruple to have the element of universal heirhood incorporated, or is this a piety of Sara herself? The formula seems to echo a similar oddity found by my doctoral student Rebecca Winer in some contemporary Christian wills here at Perpignan, with statements such as: “In all my other movable or immovable goods, wherever and however they may be, I establish as my universal heir my lord Jesus Christ, for love of whom let all my goods be given and distributed [to the poor].” The variant in a Jewish will, with God for Christ, may indicate an acculturative influence or perhaps the notary’s formula adapted to his Jewish client’s sensibilities. The extended family here is seen from Sara’s distaff vantage:

The last of the Perpignan wills is by far the longest and it contains its own surprises. The testator is Asher Mossé Daví, husband of the deceased Bononis and father both of a widowed daughter named Cohen and a minor son Samiel Asher. Lesser players include Astruc, son of Cohen and her deceased husband Bonsenyor Astruc; Asher’s aunt (his father’s sister) Meirona, with her three daughters; and an unusual panel of Jewish and Christian executor-auditors. There seems to have been a long-standing dispute between Asher and his daughter Cohen in connection with a previous legacy from his wife Bononis.

“Cohen” seems a decidedly odd given name for a woman, with its echo of the priestly function. It cannot be that the Latin notary misheard the Hebrew unisex name Chonen (“gracious”) or that Emery’s transcription is faulty. The original in the communal archives, kindly supplied for me in photocopy by my student Rebecca Winer, clearly and fully spells out her name no less than eight times. Though Seror lists nearly twenty male uses of the name in Occitania and France in the Middle Ages, always as surname or title, he has found only one other feminine use, as “Choentz.” Perhaps “Cohen” is merely the ultimate eccentricity in the individualistic catalog of medieval feminine Jewish names. Feminine Bononis here may be the common name Bona (“good”) in diminutive as Bonona, put in the third declension, or perhaps a variant of the Catalan male given name, Bononi.

When Asher had this “settlement of my goods written out and arranged” in November 1322, he was “of sound mind and healthy body, in good sense and full memory.” He stipulates that Barcelona money is to be used for all his legacies, thus excluding the older Roussillonaise or Melgorian money as well as the smorgasbord of currencies enjoyed by a frontier town like Perpignan. Asher first sets aside 2,000 sous to be paid to his daughter Cohen “just as soon” as she makes definite plans to remarry. Meanwhile her brother “must provide her with food, clothing, and her other necessities, generously and appropriately, within his house and from his goods.” The sum incorporates also a legacy of 25 pounds (500 sous) “which the said Bononis my wife left to her in her last will.” Cohen also gets “all her own clothing [vestes]” and that of her mother (a considerable gift in a medieval household) as well as all “furnishings, equipment, jewels, and bundles of goods.” In case of Cohen’s death, all her legacies from father or mother revert to her brother Samiel.

Here the testator introduces a bugaboo: the Falcidian fourth and Trebellianic fourth (falcidia ac trabelliamea). The Falcidian proviso was a relic of Roman law guaranteeing any heir at least a fourth of an inheritance, lest the word “heir” have no meaning. The proviso gave an heir the right to diminish the legacies of other heirs in order to secure his minimum fourth of the estate. The Trebellianic fourth allowed an heir to deduct part of the estate before the executors received it. Asher’s insistence indicates that such a maneuver was a present danger: “I veto and forbid that Falcidian fourths have any place” in the will. Specifically, neither Cohen nor her son Astruc can “acquire, have or gain anything by reason of the Falcidian waiver of a legal fourth share or in any other way.”

The universal heir, of course, is the only son Samiel: “all my books, movable assets [rauba], debts owed me, possessions, and all my other goods real and movable, and whatsoever claims and legal actions.” Samiel’s inheritance must provide restitution for any outstanding debts of the father. If Samiel dies “within the time of his minority [infra pupillarem etatem] or at any later time, without legitimate children born of legal marriage, I substitute for him my daughter Cohen if she shall be alive.” If Cohen herself dies, then “I substitute for my same daughter and my aforesaid son and heir” any children of Cohen’s.

If both Samiel and Cohen die without surviving children, “I wish and order all my aforesaid estate and its goods, wholly and without any diminution, to devolve and revert to the illustrious lord king of Majorca and to his own.” This startling proviso calls for explanation. After all, the current king was Sanç, whose behavior toward his Jews was persecutory (a decade of vexations about to end with the king’s death). Did Asher have some close connection to the royal court, an intimacy that might have led to such a gift? Or was the testator so alienated from his extended family (if any), and even from his community, that he cut them off so decisively? Other motives might be conjectured, from simple patriotism to a conciliatory gesture toward the crown. A matching proviso (discussed below) near the end of this long will may supply clues toward clarifying the matter.

Asher instructs his executors “to buy, within the year I am buried, up to a price and value of 20 Barcelona sous, one plot of land.” Along with 5 sous in cash, he leaves this “to Astruc, son of the said Cohen my daughter, as the share and inheritance and legacy, and for the whole claim belonging to him in all my goods and those of my deceased wife, as well as in the legacies made by me above and by my said wife to the said Cohen in her last testament,” without any possibility of further profit for Astruc. In a similar voiding of potential claims, Asher leaves 10 Barcelona pounds, or 200 sous, to his paternal aunt Meirona (Mayrona) and to her three daughters “in satisfaction and recompense for all the legacies and profits and emoluments made by my deceased father in will-form or without a will.” This payment is made only on condition that “Meirona herself and her aforesaid daughters, with the agreement and approval of their husbands, must and ought to pay and dismiss all the aforesaid legacies made to them by my father”; and they are to waive any claims on Asher’s heir Samiel arising from such legacies. If Meirona and her daughters refuse this condition, Asher’s offer to them becomes “worthless and null and void.” And if they claim that Asher or Samiel owe them more because of the legacies from Asher’s father, then the following conclusion, “for eternal remembrance of the affair,” is inserted: “Both the illustrious lord king of Majorca and the illustrious lord king of France shall have and receive” all the legacies and profits made to Meirona and her daughters by that said father; the kings would receive these “in the general indemnities that they want to have from the Jews dwelling in their sovereignties.”

This provision sounds less like a charitable shouldering of the community’s tax burden than a threat and obstacle to Asher’s aunt’s insistence on her claims. This expression of ill will about a single legacy would seem to clarify the previous wholesale delivery of Asher’s wealth to the king of Majorca in case his nuclear family and their progeny were to cease. Even as a threat, the incorporation of the king of France as a chief beneficiary of a Jewish will in 1322 sounds very odd. The French king had recently contrived to make himself the feudal lord over the Majorcan king for Montpellier, just as Arago-Catalonia was now feudal lord for the generality of the Majorcan king’s holdings. And tension was obvious among the three powers, as each maneuvered for advantage. Was such a legacy designed to placate the French crown? Or to balance the effect of the many French Jews who were making their way back again into France? As for the Majorcan king, he continued to oppress his Balearic Jews with a fine of 95,000 pounds; the will does not direct its legacy here toward helping this communal payment, though oppressive crown demands also affected Perpignan.

Asher seems to view these royal acquisitions as unlikely, since he goes on to set up an elaborate pattern of oversights. As executors and guardians for his widowed daughter Cohen, “as long as she remains without a husband,” and separately as executors and guardians for his minor son Samiel, Asher chooses two Christians and two Jews, all residents of Perpignan. The Christians are Guillem Castelló an apothecary and Joan Bonhom a merchant. The Jews are Duran Samiel and Bonjueu Profet (“Bonjuses Profayt”). They all exercise joint “agency and authority” to “rule, direct, and administer” the persons and properties of Cohen and Samiel “as will seem right and just to them.” The two Jews, however, “each by himself, can and should legally notarize and loan at interest and for the good of my heir, and should recover the payments from these,” reporting on such loans “immediately” within eight days to the two Christian members for approval. All other business, negotiations, payment, and financial administration must be “by the agreement, assent, and approval of all the aforesaid executors together.”

A super-executorship monitors the four: “they must render once every year an audit and financial report to Vidal Grimalt, a [Christian] investment financier, and to Vidal Meir [“Mayr”], a Jew of Vilafranca.” Emery notes that Grimalt’s description as burgensis is a technical term in these registers for men who lived on investments in trade, finance, or agriculture, without personal involvement in directing those enterprises either at home or abroad. The Christian must therefore have been a particularly experienced and particularly affluent financier. The Jew was a son of Bonafós de Vilafranca and a resident of Pézénes near Béziers. (The name may refer to Villefranche-de-Conflent or Villefranche-de-Rouergue in Occitania.) Though Vidal Meir appears only fleetingly in the registers, his one purchase is impressive, a house at Perpignan worth 4,000 sous.

Asher makes one final demand: “My son and heir is not able, nor ought he, to sell, pledge, or alienate my residence [hospicium] in which I live, in the Jewish quarter [callus] of the town of Perpignan, fronting along one part on the holding of Mossé Bonsenyor and on the other on the holding of Mossé Bonafós, Jews, except by the express assent and approval of my said daughter and the aforesaid executors, guardians and administrators.” The first neighbor here was Mossé Bonsenyor de Montpeller (modern Montpellier), son of Bonsenyor Jacob de Montpeller, grandson of Jacob de Montpeller, and brother of Astruc, Cresques, and Samiel—three generations who together stood among the largest moneylending operations in Perpignan. The second neighbor was Mossé Bonafós de Narbona (modern Narbonne), son of Bonafós Mossé de Narbona, husband of Meirona the daughter of Bonsenyor Jacob de Montpeller (just met above), an active moneylender who received from his father in 1284 a block of contiguous houses in Narbonne, valued in 1306 as worth 3,600 sous of Tours. Thus Asher had wealthy neighbors at each side and could call on the service of distinguished Jews and Christians alike.

Besides the notary Ramon Imbert, the text gives as sworn witnesses the Christians Bartolomé Soler, Bernat Gres, Pere Ferran, Guillem Barau [Barravi], Jaume Capdevila, and Jaume Bosc—“all weavers of Perpignan”—another reminder of the city’s eminence in textile manufacturing and redistribution.[16] Asher’s family emerges from the will as:

Only these five wills survive for the quarter century covered by Emery’s seventeen notarial registers. Since wills elsewhere appear in random patterns in such registers, there is no schema by which the percentage in hand for Perpignan can be projected into the missing codices of the city’s early registers. Thus we cannot yet see demographic patterns or know how many or what percentage of Jews here actually made Latin wills. That style of inquiry must await systematic search of richer notarial depositaries, with the subsequent patterns applied to incomplete sets of registers, such as that at Perpignan. A small number of allied documents in these registers points to yet other wills, Hebrew or possibly Latinate. Several are standard exit approvals by minors now grown of age, waiving any legal recourse later against executors.

In 1277, for example, Reina the daughter of Isaac Samiel and Astruga, now over eighteen years old, validates the work of the executors established by her mother’s will—Belan Mossé de Scola, Asher de Lunel (mentioned above in Perpignan’s third will), and Vidal Bonfill de Scal. Reina has now received all her mother’s goods, including loan documents of her debtors and “some other loans that you contracted in my name as contained in the documents of the said debts.” This waiver, on the model of similar waivers such as those of the crown to bailiffs at the end of an audit, is one of only a handful surviving at Perpignan from a whole genre. After listing the three Christian witnesses, Reina closes with the promise of yet another document: “Whenever I shall take a husband, I am to make for you a charter of payment and closure with the agreement and approval of that spouse whom I shall take.” Thus even a routine will could generate further notarial action, both from the loan procedures of the executors and from multiple waivers such as Reina’s. Details about individuals and families from the wills and their contexts can be carefully woven into a wider tapestry.[17]

| • | • | • |

Puigcerdá

High in the Pyrenees, the Cerdanya region straddled what is now French Cerdagne and Spanish Cerdaña, as part of the mainland holdings of the Kingdom of Majorca. The region had formed part of that kingdom informally even in the lifetime of Jaume I but did so with full effect from 1276 when the Conqueror died. The capital city of the then-unified Catalan Cerdanya was Puigcerdá, a communication and distribution hub connecting Mediterranean Roussillon at Perpignan to Urgell and the markets of Aragon and western Catalonia. Securely walled on its hilltop amid the looming Pyrenean ranges, Puigcerdá in 1300 was well advanced in the ascending curve of commercial development from 1250 to 1350, lively with international merchants and the court of a royal vicar.[18]

The Jewish community, from our surviving evidences, was well established and reasonably prosperous. The even larger community down at coastal Perpignan, capital of the Jewish tax collectory for the Roussillon and Cerdanya regions, held some three to four hundred souls in a hundred families by 1290, nearly half having names suggesting antecedents in southern France. A cursory look through the records for Puigcerdá suggests that at least fifty male adult Jews lived at Puigcerdá, a community therefore half the size of Perpignan’s. The growing Jewish community, which constituted 10 percent of Puigcerdá’s population by the end of thirteenth century, lived mixed among the Christians here, though a privileged Jewish district was also spreading outside the walls of the original town, north and northwest of the church of Santa Maria. This district, with its synagogue, hospital, and other amenities, centered around the site of the later Franciscan church of Sant Francesc. A Jewish home at Puigcerdá normally held only a nuclear family, the average number of children in a home numbering three to five. Besides the permanent residents, a large number of Jewish businessmen came and went irregularly. Population pressures occasioned a considerable enlargement of the town’s walls, encouraging the Jews from the mid-fourteenth century to move their community center farther north within the new walls.

The Liber Iudeorum for June 1286 to November 1287 at Puigcerdá, its earliest codex for contracts involving Jews, includes loans by the Puigcerdá Jewish community to Christians in at least 170 towns and villages of Cerdanya. Though focusing on loans, the codex also includes other arrangements, such as dowry notices, marriage agreements, gifts, procuratorships, or receipts. The strong community, explicable in terms of Puigcerdá’s international importance, doubtless owed much to the recruitment of Jews by Jaume the Conqueror, with special privileges to those in the Roussillon-Cerdanya district. It must also have benefited from the drift of Jewish population out of Languedoc, away from the increasing French presence, into the Roussillon-Pyrenean refuge.[19]

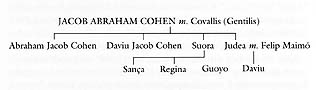

The Liber Iudeorum has some documentation relative to last dispositions, such as a notice about the universal heir of David or Daviu Cohen and an action by which the widow Regina as tutrix named her son Vives to be procurator in receiving buildings at Montpellier. For early wills, however, we must turn to the trove of notarial manuals recording the daily business of the town’s Christians. I recently conducted a systematic search through some sixty such codices for the period 1260 to 1335, later extended to random further search. Amid the innumerable wills and codicils, the occasional Jewish will offered a welcome bonus. As a component of the codices they were rare enough, but cumulatively they amounted to more than I had encountered elsewhere for so early a period. I have not attempted to find them all. The next chapter will analyze a representative four, closely clustered in 1306 and 1307, while chapter 6 will provide three more. By way of introduction the present segment will discuss two Puigcerdá testaments: one by Jacob b. Abraham Cohen in 1321 and one by Mossé Eli Bedós in 1348. These wills suffer the usual infirmities of notarial codices, including water damage and wear at top and bottom (obscuring testator and witnesses) and dimming of the paper, which does not survive as sturdily as parchment charters. The spastic hands and careless abbreviations of these hurried notes further deter the researcher, who must often coax the letters or the meaning from bad handwriting.

The first testament in this selection is early enough; it comes from the notary Mateu d’Oliana (active at Puigcerdá from 1277 to 1325) and his colleague Guillem Hualart (active from 1314 to 1329) whose joint Liber testamentorum runs from 29 June 1321 to 10 July 1322, roughly a year. The codex contains a single Jewish will, that of Jacob b. Abra(h)am Cohen (“Choen”) on 20 November 1321.[20] His Latinized name is clarified from “Jacob Abrae” by a supralinear insert, not “Aven” but “Coen.” A resident (habitator) of Puigcerdá, having fallen ill, he appoints as executors his sons Abraham Jacob Cohen and Daui (Catalan Daviu) Jacob Cohen. His wife Covallis—Convallis(?)—is deceased, as is his daughter Suora (probably Catalan Sor, for sister.)

One of Suora’s daughters, Sança (his neptis or granddaughter), comes first among the legatees, with 100 sous. Suora’s second daughter Regina gets only 5 sous; a supralinear insert qualifies this as “toward her dowry [maritagium].” The third daughter Guoyo also receives 5 sous. The three sisters seem already to enjoy the dowry Jacob had given their deceased mother, and he is not disposed to add to their resources: “and they can request or have nothing else from my goods.” A final daughter Judea, married to Felip Maimó, gets 5 sous and the dowry “which I gave.” Her son Daviu receives 20 sous. Jacob then recognizes his dead wife’s dowry, 1,000 sous. In that sum she had established as universal heirs the sons Daviu and Abraham; he now orders the executors to pay out the thousand. Jacob acknowledges a debt of 100 Barcelonan pounds to his son Abraham, by legal contract (cum carta), which he orders paid. After all these items have been taken care of, the two sons inherit “my other remaining goods.”

The seven “invited witnesses” are Pere Perats the cobbler, Jaume Brahl, Jaume Borser, Felip Celarer the younger, Guillem of Eina (now in French Cerdagne), Vicent of Eina, Pere Ermengau, and Boniacip [Bo(n)macip?] Leví a Jew. The ambiguous Latin Iacobus may be Jacob rather than Jaume, since only one of the other names is designated as a Jew and two witnesses would be usual. Selar/Celar may be this Felip’s name, but a flourish indicates yet another er component (Cellerer?). The document would have been dictated in Catalan to the Latin-wielding notary, a common practice; the son’s Catalan name Daviu appears at first as Daui, then as Daviu canceled with Davidi substituted, and finally in its correct form Daviu twice. Similarly the last witness is given as Leví, then canceled and the fuller name substituted.

The daughter’s name Guoyo or possibly Guoyx has a preceding false start deleted. If Guoyo, it is a variant of the feminine name Goyo seen in the previous will; if Guoyx, it is a version of the better-known Goig. Both versions of Catalan Goig mean “joy.” The wife “Covallis” (genitive) has an abbreviatory overstroke promising extra letter(s), and her name remains something of a mystery.[21] Various Cohen and Leví members of the Puigcerdá community appear in the earlier Liber Iudeorum. The family members here correspond in part to those of 1306 in Gentil’s will in the next chapter. Is the wife here that Gentil, and Philippus Fabib? The immediate family may be schematized:

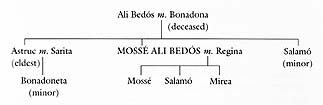

Mossé Ali Bedós (“Bedoz”) drew up his will on 22 July 1348. Bedós and Bádos are general Catalan surnames. Ali will be examined below. Mossé chooses two men of the Cohen family as his executors and arranges for burial “in the cemetery of the Jews of Puigcerdá,” to which he leaves 3 sous. Ten sous apiece go to his brothers Astruc and Salamó, but 7 pounds and 10 sous to his children Salamó, Mossé, and Mirea. The manuscript seems at first to posit two sons, Salamó Mossé and “Mrea.” Close reading of texts and tenses shows that Salamó and Mossé are the sons. Mrea is the daughter; the initial letter is blotted (but must be m: cf. the preceding Mossé) and no abbreviation is signaled. Her name may be the Catalan feminine Mira, “notable,” popular among Jews, or even Hebrew Miryam in the variant Marea.[22]

If any of the three children dies, the freed share reverts to the others. If all die without legitimate issue, the full legacy returns to their mother Regina. The executors are to distribute 5 sous to charity as a pro anima legacy as well as “all my clothing.” Two sous are for “lamps of the synagogue [scola].” Everything else goes to his wife Regina as universal heir. The seven witnesses are all Christians. The family structure is sketchy but can be supplemented from the property inventories drawn on the occasion of the deaths of Ali and of Astruc.

Carme Batlle has published and analyzed the postmortem property inventories both of Mossé Ali in 1348 and of his father Ali in 1344, on deposit at the neighboring cathedral archives of Seo de Urgel. The father’s inventory gives him as both Helie (or perhaps nominative Helia) and several times as Ali and En Ali (“N’Ali Badoz”). The son’s inventory prefers the form Helie. As with many such inventories, the lists take us into the family’s capacious home at Seo de Urgel, reveal the “considerable fortune” involved, and detail the clothing, jewels, and furniture on hand. They also describe at length the Hebrew and other books in a large family library.[23] A Puigcerdá testament from the same family (as first names and surnames strongly argue) will be presented in the next chapter, from 1306. Instead of Ali/Helie, the name Elias appears there. The many appearances of Ali in the 1344 and 1348 inventories and in the 1348 testament tempt one to see here the merger of Arabic ‘Alī with the biblical high priest Eli. The biblical name was not used before the rise of Islam, Goitein informs us, since Eli was considered “ill-fated.” Because the name then made a perfect cognate with the secular ‘Alī, however, Eli became “the most common name in the Geniza” community. If Ali/Eli/Helie in the Bedós family has that origin, it may signal antecedents and influence from the Islamic world. Yet the 1306 will describes that (this?) family as from Mazères in southern France. In that migratory age and with general intermarriage, both origins might be accommodated. In his study of French names, Simon Seror subsumes Ali, rare in those parts, under generic Elie for biblical Eliyahu (Greek form Elias).

The next set of Puigcerdá wills deserve a chapter apart. Not only do they form a tight, interrelated group chronologically but they invite extended comment as particularly involving women.

Notes

1. See the comprehensive A Mediterranean Emporium: The Catalan Kingdom of Majorca (Cambridge, 1994) by David Abulafia as well as his “The Problem of the Kingdom of Majorca,” Mediterranean Historical Review 5 (1990): 150–168 and 6 (1991): 35–61, and his “A Settled Frontier: The Catalan Kingdom of Majorca,” Journal of Medieval History 18 (1992): 319–333. See too J. N. Hillgarth, “Majorca 1229–1550: The Economic and Social Background,” in his Readers and Books in Majorca 1229–1550 (Paris, 1991), vol. 1, chap. 1. See also Larry Simon, “Society and Religion in the Kingdom of Majorca, 1229–c. 1300,” based on his doctoral dissertation (UCLA, 1989), currently being prepared for publication, esp. chap. 2, “Wills as Documents, and the Testator Population,” with an appendix of transcribed wills. The standard multiauthor history is Historia de Mallorca, ed. Josep Mascaró Pasarius, 10 vols. (Palma de Mallorca, 1978), esp. articles there by Alvaro Santamaría Aránez in vol. 3. Santamaría Aránez also has an extensive bibliographical-thematic monograph, “Mallorca en el siglo XIV,” Anuario de estudios medievales 7 (1970–1971): 164–238, as well as a volume of some 650 pages exploring all the problematics, themes, and bibliography of this odd kingdom: Ejecutoria del reino de Mallorca, 1230–1343 (Palma de Mallorca, 1990). See also Pablo Cateura Bennasser, Sociedad, jerarquía, y poder en la Mallorca medieval (Palma de Mallorca, 1984), and the wide-ranging fiscal-commercial study by Antoni Riera Melis, La Corona de Aragón y el reino de Mallorca en el primer cuarto del siglo XIV, 1 vol. to date (Madrid, 1986), including background chapters.

2. On the kingdom’s Jews, see David Abulafia, A Mediterranean Emporium, chap. 5; his “A Settled Frontier: The Catalan Kingdom of Majorca”; and his “From Privilege to Persecution: Crown, Church, and Synagogue in the City of Majorca, 1229–1343,” in Church and City 1000–1500: Essays in Honor of Christopher Brooke, ed. David Abulafia et al. (Cambridge, 1992), 111–126. Simon, “Society and Religion,” chap. 6, has a comparative study of Majorca’s Muslims and Jews. Richard W. Emery, The Jews of Perpignan in the Thirteenth Century: An Economic Study Based on Notarial Records (New York, 1959), includes some 150 documents transcribed. Josep Mascaró Pasarius has a book-length general study “Judíos i descendientes de judíos conversos de Mallorca” in his Historia de Mallorca, 10:44–180. The celebrated codex of Jewish privileges for Majorca is transcribed by Fidel Fita and Gabriel Llabrés, “Privilegios de los hebreos mallorquines en el códice Pueyo,” Boletín de la Real academia de la historia 36 (1900): 13–35, 121–148, 185–209, 273–306, 369–402, 458–494. Valuable for its documents also is Antonio Pons, Los judíos del reino de Mallorca durante los siglos XIII y XIV, 2 vols. (Palma de Mallorca, [1958–1960] 1984). For the Jews of Cerdanya and Puigcerdá, see below, this chap., n. 18. My doctoral student Rebecca Lynn Winer is finishing her dissertation at UCLA “Women, Commerce, and Family in Perpignan 1250–1325” from extensive archival researches, including a chapter on the experience of Jewish women and their roles and autonomy in Perpignan society; new Jewish Latinate testaments will be recovered and analyzed there. Philip Daileader, Jr., has in hand an archival dissertation under Thomas Bisson at Harvard University, “Community, Government, and Power in Medieval Perpignan 1162–1397,” with a chapter “The Jews of Perpignan.”

3. Abulafia, “From Privilege to Persecution,” 118.

4. Fita and Llabrés, “Privilegios,” pp. 133–134, doc. 25 (21 July 1319): “ad civitatem et regnum Majoricarum concurrunt passim judei et judee alienigeni vagabundi…[et] ponunt discordias et inimicitias inter judeos nostros dicte aljame.”

5. Ibid., pp. 199–200, doc. 46 (11 February 1328): “et cum judei dicte aljame mercantiliter vivant pro parte majore,” the king allows that any Christian or Jew in debt “to any Jew or Jewess” there “by any mercantile contract or by partnership [comanda] or otherwise than by an interest loan [contractus usurarius]” may be arrested at the request of the Jewish creditor.

6. Arch. Hist. Nac., Clero Secular y Regular, Dominicanos: Palma, carp. 89 (6 July 1288, in 13 June 1292), transcribed below in appendix, doc. 31. This parchment version was doubtless generated from a notarial original, its paper codex now lost.

7. Shlomo D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 6 vols. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1967–1993), 3:317. Omar for ‘Umar is not Omer, a new Hebrew name today in Israel.

8. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, 11, 102 (quotes). There were Jews here from at least 1160. Emery’s notarial documents are from Perpignan’s Archives Départementales des Pyrénées-Orientales, séries E, fonds des notaires, regs. 1–17.

9. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, 99, 106–107 (quotes); see also p. 14.

10. Ibid., 106–107.

11. Ibid., pp. 134–135, doc. 4 (27 February 1273): “Bonisachus Fagim judeus etc…dimitto jure institutionis et nomine hereditatis sue de dictis bonis meis Bonedomine filie mee M.DCCC.LXX. V. sol. Bar. de qua etc. et dono dicte filee mee in curatorem et gubernatorem Juceffum de Crassa…item dimitto Regine filie mee jure institutionis…et totum quod sibi dedi tempore nuptiarum suarum cum viro suo…item volo et mando quod Bonafilia uxor mea habeat et reciperet suam dotem sicut continetur in instrumentis nuptialibus judaycis…instituo mihi heredes universales Vitalem Bonissac et Fagim Bonissac filios meos.” On (Sa) Grassa see also pp. 18, 27n., 30, 147, 155, and 163–164. The name Bonisac as Bon Isaac, as well as Vidal and Mossé, have been noted in my introduction. On Bonadona see chap. 3, n. 22. Irene Garbell, “The Pronunciation of Hebrew in Medieval Spain,” Homenaje a Millás-Vallicrosa, 2 vols. (Barcelona, 1954–1956), 1:662, 682. Simon Seror, Les noms des juifsde France au moyen âge (Paris, 1989), 235, 274.

12. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, p. 167, doc. 98 (10 October 1283). Gaugs is a Provençalism in Catalan.

13. Ibid., pp. 138–139, doc. 19 (9 August 1273): “quendam librum meum in quo sunt scripti [V libri] legis Moysi quem penes se habet”; “omnes libros meos quod penes me habeo”; “teneatur providere dicte Massipe filee mee in comestione et potu et indumentis et calciamentis usque quod dicta filia mea virum accipiat”; “solvatur Argote uxori mee tota dos sua prout in instrumento ebraico nuptiali facto inter me et ipsam”; “uxori mee Argote omnia indumenta sua et pannos meos omnes et totam bascolam meam que est in domo mea exceptis vasis vinariis et tina mea”; “dimitto helemosine obalorum judeorum infirma[n]cium VI sol. III den. Bar.” I have made “generos meos” simply “in-laws”; the classical usage as son-in-law had by now become brother-in-law, father-in-law, or sometimes relative. Argota’s name may relate to Catalan agut, feminine aguda, “animated” or “lively.” The name Profait is a puzzle. Seror lumps it with Perfet (see above, chap. 3, n. 45) as meaning “(moral) profit,” not a plausible joining. If Perfet is Catalan for “complete” and translates Hebrew shalom, and profiat/porfiat means “tenacious,” there is still also room for conjecturing Catalan profit (for “profit”) for Profait as in note 45, chap. 3, above. On the “coronat” diner de tern in this document, see my introduction, above, under “Moneys.”

14. Ibid., pp. 149–151, doc. 49 (10 February 1277): “[si] voluerit venire apud Perpinianum morari una cum dictis heredibus meis et cum eis habitare”; “in tota vita sua tantum totum mansum meum in quo inhabito qui est in podio ville Perpiniani in callo judeorum”; “uxori mee omnes pannos meos et archas et vasa vinaria et alia utencilia domus mee…[et] instrumenta et alia que sint in dictis archis”; “dimitto amore Dei in remissione pecc[at]orum meorum DCXXV sol. Bar. coronatos…quolibet anno in festo quod judayce vocatur cabanes”; “amore Dei operi pontis Thetis Perpiniani”; “et ordino quod nec aliqua dictarum filiarum mearum nec etiam alia persona nisi tamen dicta uxor mea transcriptum sive translatum huius presentis testamenti mei possit habere nec sibi detur nec dicti heredes mei teneantur sibi dare.” A number of persons involved here can also be traced in nontestamentary business in Emery’s text and documents; his quote on Samiel is on pp.103–104. Perpignan got its first stone bridge, the Pont de Nostra Dona, in 1195; the legacy here may be for its maintenance (operi) or for a new construction. The Scal toponym for one witness may be any of four Occitan places or L’Escala on the Ampurian coast (cf. Seror, Noms des juifs, 249–250). The transcription Scal, as Seror found for another of this name in Emery, may be Soal, for which I suggest the biblical names Shual (“fox”) and Shoval (“way”) or a Catalan toponym like Escala. Kolatch’s tracing of Meirona to Aramaic (“sheep”) or Hebrew (“troops”) is unnecessary in the Catalan context as above. On the equivalence of Asher and Asser in medieval Spain, see Garbell,“ Pronunciation of Hebrew,” 666. The will of Benvenist is above in chap. 1, n. 26.

15. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, pp. 187–188, doc. 137 (24 September 1286): “manumissores meos scilicet Profaytum Davini de Capitestagno et Durandum de Malgorio habitatorem de Biterris”; “quasdam domos meos contiguas que sunt in civitate Narbone in fusteyria…et de eis semper quolibet anno in perpetuum doceri faciant infantes judeos pauperes de schientia ebraica quoscumque voluerint tam de Biterris quam de villa Perpiniani quam aliunde et specialiter de genero meo et dicti mariti mei…[et] emantur libri judaici”; “duos libros meos judaicos in quibus continentur V libri legis Moysi” (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy); “Blanche filie Abrae de Magalas ad opus sui maritamenti XX sol. Melg.”; “in omnibus vero aliis bonis meis quecumque sint et unacumque [= ubicumque] instituo mihi heredem universalem dominum Deum amore cuius solvetis…amore Dei ad pauperes judeas maritandas.” The manuscript’s spelling of the names involved is Sara, Davinus de Capitestagno, Profaytus Davini, Durandus de Malgorio de Biterris, Mayrius, Juceffus, Cresques, Salamonus, Sima, Saverdia, Magalas, Mosse, Opidus (Latin for Opol in Roussillon). Sancho’s toponym must be Vilallonga de la Salanca on the Tet river near Castellrosselló. The witnesses’ occupations include ganterius (Catalan guanter) and bracerius (Catalan bracer). The toponym Cabestany is Capestang, west of Béziers in Occitania. For the names Cresques, Jucef, Mossé, and Salamó see above, my introduction; Profet is discussed above in this chap., n. 13, Bonsenyor in chap. 3, n. 21, and Daví in chap. 3, n. 19.

16. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, pp. 189–191, doc. 139 (8 November 1322): “duo milia sol. Bar. ad opus eius maritamenti…et quod interim heres meus subscriptus provideat et sibi providere teneatur intus domum suam de bonis suis in victu vestitu et aliis suis necessariis bene et decenter”; “filie mee omnes vestes sui corporis et omnes vestes que fuerunt dicte uxoris mee cum earum ornamentis, preparamentis, et jocalia sua et ligamenta ubicumque sint”; “falcidia ac trabelliamea locum non habeat in premissis”; “volo et mando totam predictam hereditatem et bona eiusdem integraliter et sine diminutione aliqua devenire ac reverti illustrissimo domino regi Majorice et suis”; “ymo ipsum legatum in eo casu volo fore cassum et nullum ac irritum…volo rationem et veritatem eis reddi et dici et in hoc testamento inseri ad eternam rey memoriam, videlicet quod omnia legata, lucra, et emolumenta per dictum patrem meum eis facta habuerint et receperint tam illustrissimus dominus rex Majorice quam illustris dominus rex Franchie in indempnationibus quas habere voluerunt a judeis in eorum dominationibus comorantibus”; “hospitium meum quo inhabito situm in callo.” The manuscript name-forms in sequence are Asser Mosse Davi, Cohen, Bononis (both nominative and genitive, feminine), Astruchus, Bonusdominus, Samielis, Mayrona, Duran, Bonjuses Profayt, Vitalis Mayr, Mosse Bonafos, and the Christian witnesses. On willing money to the king in Jewish wills, see pp. 57, 61, and 92; Norman Roth cites a legacy at Arévalo near Avila of 2,000 dinars “for the needs of the kingdom or the bishop,” together with the gift of her houses to become a synogogue (“Bishops and Jews in the Middle Ages,” Catholic Historical Review 70 [1994]: 14). Emery’s text and documents add nontestamentary information on a few of the Perpignan principals (see the index); on burgensis see his p. 53. On the tension and background involving the kings of Majorca and France at this time, see Alvaro Santamaría Aránez, “Tensión corona de Aragón-corona de Mallorca (1318–1326),” En la España medieval 3 (1982): 423–495. The names Astruc, Jacob, Mossé, Samiel, and Vidal are touched on above in the introduction; Maymona, Meirona, Belan, and Asher were treated earlier in this chapter. For Bonafós see chap. 3, n. 33; for Bonjueu and variants see n. 31 there; for Daví n. 19; and for Profet as perhaps “profit” n. 45 (cf. above, this chap., n. 13).

17. Emery, Jews of Perpignan, p. 149, doc. 48 (10 January 1277). See also p. 156, doc. 66 (8 January 1279): testamentary guardians had invested in loans; pp. 162–163, doc. 88 (1 September 1283): one testamentary guardian “non laudat” an arrangement; pp. 163–164, doc. 90 (5 September 1283): guardian approves a sale; pp. 169–170, doc. 107 (19 November 1283); p. 175, doc. 118 (17–26 March 1284); and pp. 175–176, doc. 119 (28 March 1284); among others here on executors or guardians.