4. The Fatimid Public Text in a Changing Political Climate

From the Rule of Wazīr Badr al-Jamālī to the End of Fatimid Rule (1073–1171/466–567)

It is not difficult to recognize that new and different messages dominated the public text during the last one hundred years of the Fatimid regime and, perhaps more important, that new formats became visually prominent both in public and in Muslim sectarian spaces. These changes appear directly related to a growing militarization within the ruling group as wazīrs and the troops that supported them gained power and authority. As these groups gained in power, they eroded the authority of the Fatimid ruler as Caliph.

This shift was recognized by all members of the population. The pages of Ibn al-Muqaffa‘’s History of the Patriarchs provides ample evidence of this awareness.[1] For the first one hundred years of Fatimid rule, events relating to the Christian community are told in relation to the actions of the Imām-Caliphs, as suggested by the anecdote related in chapter 3 concerning the actions of Imām-Caliph al-Mu‘izz and the population of Miṣr. Over the course of the last one hundred years, almost without exception, the pages tell about the manner in which wazīrs and those troops who backed them shaped the lives of the population. Their rise and fall, and the troops who supported them, are intimately bound up with life in the Cairo urban area.

Concomitantly, the authority of the Fatimid ruler as Imām was reduced in scope. Two major succession disputes during this period reduced the number of Ismā‘īlīs in the Cairo urban area who recognized the Fatimid ruler as Imām. This reduced number of Ismā‘īlī Believers was not translated directly and consistently into a reduced display of signs of Isma‘ilism, or of processions in which cloth displayed Ismā‘īlī phrases. In some decades, what appears to be a bold use of these signs served, as the visual often does, to mask the weakness of the position of the Imām-Caliph in favor of supporting the social order as a whole, which in turn sustained the newly strengthened position of the wazīr. Those public texts which displayed the rank and title of the wazīr indicated strength where the real strength existed.

| • | • | • |

Cairo-Miṣr and Wazīr Badr al-Jamālī

New writing signs began to be displayed in Cairo-Miṣr in a physical and social environment which had changed significantly from the time, a mere two decades before, when Nāṣir-i Khusraw described the Imām-Caliph al-Mustanṣir’s procession. This change in the former urban structure was accelerated in the mid-eleventh century by major socio-economic crises:[2] riots; administrative chaos between Turkish and Black army regiments; attacks by Berbers in the Delta; relentless famine caused by successive years of low Nile; epidemics and inflation; and Seljuk invasions in Syria and Palestine. These crises led Imām-Caliph al-Mustanṣir to summon Badr al-Jamālī, his commander of the army (Amīr al-Jūyush), from Syria in 1073/465 to be wazīr and to restore social order.[3]

Badr al-Jamālī’s measures to restore order in the capital area altered the composition and distribution of the urban population, particularly in Cairo. In the new urban social order his measures shaped, Badr al-Jamālī used officially sponsored writing actively to address new audiences with new messages.

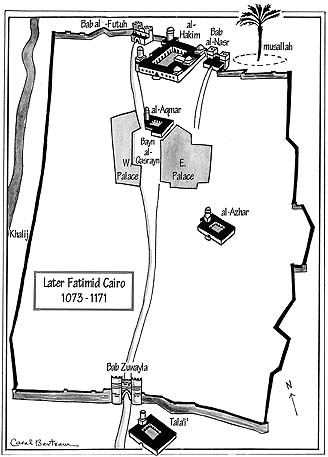

The clashes between contingents of the Fatimid army and the actions Badr al-Jamālī undertook to curb the effects of the famine and plague all effectively blurred the distinctions between the northern and southern zones in Cairo-Miṣr.[4] Badr al-Jamālī allowed the Armenian Christian troops who came with him from Syria to establish themselves in a quarter within Cairo.[5] Because the plague had substantially reduced the entire population, Fusṭāṭ and al-Qaṭā’i‘, being particularly devastated, Badr al-Jamālī permitted those living in these areas to take building materials from those southern zones to build in Cairo proper.[6] By these acts he opened Cairo to the whole society, even as he expanded and fortified its walls and gates to keep the common enemy out (map 3).[7] In time, notables from the Christian and Jewish populations also moved into Cairo. Other wazīrs followed and augmented this course, especially his son al-Afḍal, and the wazīr al-Ma’mūn. When conditions permitted, wazīrs also moved south to Miṣr, further blending the populations in the whole urban area.[8] As a result of these actions, Cairo no longer was simply an Ismā‘īlī royal enclosure.

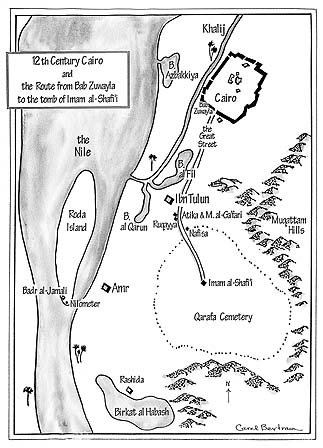

While most areas of Cairo became mixed in population, and ordinary traffic on the Great Street increased, two areas were vested with special character. The northern half of Cairo retained its Fatimid Ismā‘īlī functions. The ruler still appeared in the bayn al-qaṣrayn, the area between the two palaces, before processions.[9] The mosque of al-Ḥākim was still visited on occasions that were part of the Ismā‘īlī and Muslim calendars, and the muṣalla outside the Bāb al-Naṣr still remained a destination for the Imām-Caliph, even to the last days of the dynasty. The Great Street, the common central north-south axis, was extended and given prominence, opening the urban zones into each other (map 4). In this changed urban context, it became the main thoroughfare along which merchants, as well as civilians, dignitaries, members of the ruling group, and official processions travelled.[10]

Map 3. Cairo, later Fatimid period 1073–1171 (drawn by Carel Bertram)

Map 4. Later Cairo and the route from Bāb Zuwayla to the tomb of Imām al-Shāfi‘i (drawn by Carel Bertram)

Later constructions on this street emphasized further its growing prominence as a thoroughfare linking both the northern and southern sections of the urban area, Cairo and Miṣr. It served as the spine along which important Muslim communal structures were built or restored (map 4).[11] In Cairo, facing the Great Street, just north of the Eastern Palace, the mosque known as al-Aqmar (moonlit), was built in 1125/519 by the wazīr al-Ma’mūn.[12] Outside the southern gate, the Bāb Zuwayla, a mosque was built in 1160/555 that was known after its patron al-Mālik al-Ṣāliḥ Ṭalā’i‘.[13] Further south, still, on this road, in the area of the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn, tombs such as those of Sayyida Ruqayya and Sayyida Nafīsa were restored and enlarged by Badr al-Jamālī[14] and subsequent members of the ruling group (map 4).

These physical and social changes begun by Badr al-Jamālī were not the only changes effected by him. Within the ruling group itself, he drastically altered the site of power, appropriating it to himself, while maintaining the formal order of the ruling system and thus al-Mustanṣir as Imām-Caliph.[15] He acted, especially outside of Cairo, to maintain the officially sponsored writing signs that would signal a strong Fatimid ruler. For example, two years after becoming wazīr (1075/467), he exerted strong pressure, in the form of written messages and lavish presents, on the sherīf of Mecca to persuade him to display writing signs with the name of al-Mustanṣir on the Holy Sites in Mecca. The sherīf complied, erasing the titles of the Abbasid Caliph al-Qā’im and the Seljuk Sultan at the Zemzem, and removing the covering for the Ka‘ba sent by the Abbasid Caliph, replacing it with the white dābiqī (linen) kiswa (covering) which displayed the names and titles of Imām-Caliph al-Mustanṣir.[16]

In Egypt, in the greater urban area of Cairo, however, Badr al-Jamālī used officially sponsored writing to proclaim the new power structure, with himself, the wazīr, as the possessor of power and authority within the social order. He did this by displaying his name and titles to the newly integrated urban audiences on the buildings he commissioned and reconstructed, a course of action paralleled by the change in formula in official petitions emphasizing his role.[17] Since he undertook a large program to restore the urban-infrastructure as a whole, as well as Muslim sectarian life, in specific, his name and titles appeared in many places; twenty-one have been identified to date.[18]

Those who passed saw his name and titles displayed on a plaque on the ziyāda (surrounding wall) of the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn which he restored in 1077/470.[19] In addition to displaying his own name, he used this public text to comment on preceding events at the site, and, in only a lightly veiled manner, on the turbulence within the ruling group which caused his own rise to power. After his name and titles is the phrase, “He caused the restoration of this portal and what surrounds it [to take place] after the fire which destroyed it that the heretics let happen.” [20] Wiet has plausibly suggested that the heretics (māriq) referred to were the Sunni Turkish troops who attacked the Black troops in 1062/454 and pillaged the treasures and the library, with the result that the area around the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn fell into ruin until Badr began to revive it with his restoration of the mosque.[21]

A decade later, those passing into Cairo saw his name and titles displayed prominently in the writings on the new gateways he constructed as part of his effort to fortify the city of Cairo against its enemies (1087/440).[22] At the Bāb al-Futūḥ, if Creswell is correct, he used the marble slabs from the northern bastion of the mosque of al-Ḥākim to complete his inscription, thereby replacing what is presumed to have been a Qur’ānic inscription with one displaying names and titles and ranks of the wazīr. Shortly after, in 1089/482, he restored the mausoleum of Sayyida Nafīsa on the Great Street on which he also displayed his name and titles.[23]

With the completion of the fortification of Cairo, Badr al-Jamālī turned his attention to Roda Island. There he constructed a new mosque, on the exterior of which he prominently displayed his name. On this mosque, a large plaque on the western facade which faced directly onto the main boat channel of the Nile displayed Badr’s name and titles in letters over two feet tall.[24] Aimed at the commercial boat traffic, it reminded viewers of his attention to the economic life of the area, and to his concern for the inundation of the Nile that supported it. An inscription with a similar message was placed over the entrance doorway, so that those on foot visiting the island and the mosque also viewed his name.[25] He also restored the adjacent Nilometer (miqyās al-nīl) and placed his name and titles inside it.

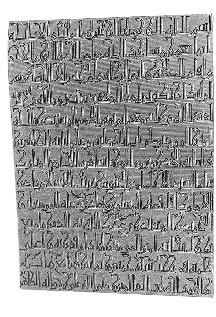

What predominates in all these inscriptions is the rank and titles of Badr al-Jamālī, although the Imām-Caliph’s name is mentioned also. It is useful to explore these inscriptions in detail because they functioned as an Ur, or originary, text for subsequent powerful military leaders in Cairo—even those ruling after the Fatimid period. J. J. Marcel, in recording these structures on Roda Island for inclusion in the Description de l’Egypte, has left the only visual record of them.[26] He was primarily interested in the semantic content of the inscriptions for their value in dating the buildings. Consequently he simply recorded the content of the large inscription on the west wall of the mosque, and that over its portal, merely as variants of the inscription on the interior of the Nilometer (miqyās al-nīl).[27] Choosing to draw only the smallest and most compact of the inscriptions, that on the interior of the Nilometer (fig. 34), he merely gave a few details about the aesthetic aspects of the other inscriptions, especially that on the exterior of the mosque.

Fig. 34. Inscription from Nilometer of Badr al-Jamālī, after Marcel, Decription de l’Egypte

He noted that all these inscriptions were carved in white marble, a medium that seems to bind together all Badr al-Jamālī’s extant public texts. He noted also that the form of the letters in the writing on the outside, western wall of the mosque were especially remarkable for their elegance, far greater than that of the other two inscriptions, especially that on the Nilometer, the only inscription he drew.[28] Marcel’s comments leave us with some evidence to conclude that Badr al-Jamālī paid particular attention to public texts. Most attention was paid to the aesthetic qualities of the writing facing the traffic on the Nile, while less attention was paid to inscriptions on the interior of the Nilometer, or over the doorway into the mosque. But while Badr apparently made audience considerations the basis for aesthetic choices in the display of writing, the referential content remained basically the same.

It is well worth examining the inscription on the Nilometer in detail for its referential dimensions. The amount of space allocated to the component sections of the inscription remained stable in all his officially sponsored writing, even though they were not displayed in this manner—a plaque of thirteen lines. The inscription begins in standard fashion with the formula, “In the Name of God, The Merciful, The Compassionate ”(basmala),[29] followed by verses from the Qur’ān which fill the first four of the thirteen lines.[30] The nine remaining lines give first the name of the Imām al-Mustanṣir, and then list in detail the names and titles of the Badr al-Jamālī, the person with the real power, along with the date of construction. Badr al-Jamālī is “the Prince Most Illustrious, the Commander of the Armies, Sword of Islam, Surety of the Judges of the Muslims, Guide of the Missionaries of the Believers.” Further along, the inscription mentions his successes in the cause of religion, and wishes him a long life in the service of the Commander of the Faithful (Amīr al-Mu’minīn), that is, the Imām-al-Mustanṣir, whose power, according to the writing, Badr al-Jamālī affirms.

This visual display, and the others like it, of Badr al-Jamālī’s name and titles in Cairo-Miṣr needs to be evaluated against the backdrop of the reduced visibility of the name of the Imām-Caliph and also of his person. While mentioned in all of Badr al-Jamālī’s inscriptions, the names and titles of the Imām-Caliph are so abbreviated that they became almost a secondary dating device in addition to that given in the hegira calendar. Unlike in Mecca, where Badr al-Jamālī worked behind the scenes to support the display of the names and titles of only the Imām-Caliph, in Cairo not only did Badr minimize the display of the Imām’s name but he stopped the processions. He stopped those like Nāṣir-i Khusraw described during which the ruler made himself visible to the whole population.[31] He also ended those in which the Imām led the Ismā‘īlī community in prayer at the muṣalla.[32] The succeeding wazīr, al-Afḍal, Badr’s son, continued these policies. With the reduced visibility of the person and the names of the Imām, the public text became an especially effective visual instrument for the wazīr, and by extension the troops that maintained him in office, to display his power.

| • | • | • |

The Public Text and Wazīr al-Ma’mūn

Al-Ma’mūn[33] was wazīr for some four years, 1121–1125/515–519,[34] during the reign of Imām-Caliph al-Āmīr (r. 1101–30/495–524).[35] An Ismā‘īlī,[36] he, like Badr al-Jamālī, had been a mamluk, and was an important Amīr in the army when he was appointed wazīr. Like Badr al-Jamālī before him, he built and restored many structures on which he displayed his name. In 1122/516 he ordered the construction of the mosque of Kāfūrī in the Kāfūr Park west of the mosque of al-Aqmar.[37] In that same year, he repaired seven mausolea along the Great Street, and ordered marble plaques put on the outside of each, displaying his name, titles, and the date.[38] None of these examples of his officially sponsored writings survives. However, the mosque he built on the Great Street, just north of the Imām-Caliph’s palace, known as al-Aqmar, displayed public texts in a layout that was brilliant for its subtle references to its contemporary visual contexts, and to al-Ma’mūn’s own manner of functioning as a powerful wazīr in a governmental structure headed by an Imām whose position was highly contested (fig. 35).[39] These public texts combined wazīr al-Ma’mūn’s rank and title information, in the tradition of Badr al-Jamālī, with a visually prominent display of the sign of Isma‘ilism, and with Qur’ānic quotations.

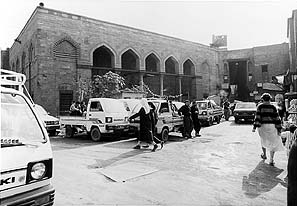

Fig. 35. Facade, al-Aqmar mosque

The facade of the al-Aqmar mosque is divided into three parts, a salient entrance portal with a large arch, and two recessed side sections with smaller arches.[40] This general layout is so remarkably like al-Mustanṣir’s kiswa for the Ka‘ba described by Nāṣir-i Khusraw that it is almost as if that covering were placed over the facade as a base. Nāṣir-i Khusraw described the covering in the following manner:

The covering with which the house [Ka‘ba] was cloaked was a white covering which displayed two bands of embroidered ornaments, each a gaz wide. The distance between the two bands was about ten gaz.…On the four sides of the covering, colored mihrab were woven and embroidered and embellished with gold filigree. On each wall there were three mihrab, a big one in the middle and two small ones on either side.[41]

Nāṣir-i Khusraw is describing a kiswa he saw in 1050, some seventy years before al-Ma’mūn built the al-Aqmar mosque, but the three arch (or mihrab) elements of its design were even at that time present in stone and stucco on the Great Street.[42] The basic display of a central large arch and two smaller side arches was already present on the monumental entrance of the mosque of al-Ḥākim (fig. 29),[43] and in what is extant today of the Fatimid sections of al-Azhar, at the entrance to the prayer hall. It might also have been present in the “ muṣalla with three mihrabs” that wazīr al-Afḍal built for the funeral service for those in Fusṭāṭ.[44] Obviously on each the spacing and placement differs. How they compared to the arches on the kiswa Nāṣir-i Khusraw saw is, of course, left to our imaginations. What the facade of al-Aqmar and the design on the kiswa share that the other arches apparently do not, is the bands that cut across them. On the kiswa we assume they displayed the names and titles of the Imām-Caliph. On the al-Aqmar mosque they display the names and titles of the wazīr, al-Ma’mūn.

Prominently—not once, but twice—across the entire facade, the two bands of writing display the name and all the titles of wazīr al-Ma’mūn, the date, and the name of the Imām-Caliph al-Āmir.[45] This is the referential base of the wide band of writing running along the entire facade under the cornice. The same information, in virtually the same words, but in smaller letters, runs the width of the facade at mid-point. This referential base is equivalent to that of the public texts of Badr al-Jamālī, even to the use of the Imām’s name as a dating device. No viewer could have escaped knowing that Abū ‘Abd Allah, “Commander of the Armies, Sword of Islam, Helper of the Imām, Surety of the Judges of the Muslims, and Guide of the Missionaries of the Believers,” sponsored this structure in 519 (1125) in the reign of Caliph al-Āmir.

This is the writing sign most visually accessible to the viewer in the Great Street. The band format heightens its legibility against its background. The letter size in the top band (c. 18 in. high) ensured readability.[46] In the second band the letters are smaller, but they are half the distance from the ground.[47] Additional aesthetic properties aid the legibility of the rank and title information of these bands. The clearest and most elegant lettering, the one that is easiest to read, is in the top band. While the elaboration of the basic Kufic style lettering of each band on this facade differs from the other, the top band is further distinguished by a base line for the horizontal letters significantly above the bottom of the moulding of the band. In practical terms, letters like rā and dāl are thus differentiated by allowing the former to descend slightly below the line of the latter. In short, more basic letter forms are distinguishable from each other in this style of Kufic writing than in the other versions of that script on the facade. As mentioned above, in the Kufic style script, differentiation of letters aided in legibility.[48]

While these bands displaying the rank and title information of the wazīr are highly legible writing signs on this facade, the concentric circle medallion over the entrance portal is also immediately recognizable by Ismā‘īlīs as the sign of Isma‘ilism (fig. 36). Its size, around 4 ½ feet (1.43 m.) in diameter, ensures its visual prominence to all beholders. A smaller concentric circle medallion is displayed over the flat arch on the left wing (fig. 37).[49] In form, the concentric circle medallion over the entrance portal replicates the sign of Isma‘ilism as we have come to expect it in terms of the placement of writing in its concentric circles. The outer circle displays a quotation from the Qur’ān, part of verse 33:33: “God only desires to take away uncleanness from you, Oh people of the house (ahl al-bayt).” In the center are the names “Muḥammad” and “‘Alī.” Some important differences exist, however, in the evocational base of the writing, which will be discussed below.

Fig. 36. Central concentric circle medallion, al-Aqmar mosque

Fig. 37. Small concentric circle medallion, al-Aqmar mosque

Under this concentric circle medallion is the only other substantial Qur’ānic quotation on the building facade. Over the salient doorway is a band stretching only the length of the doorway itself displaying two verses from the Qur’ān, 24:36–37. These two verses are appropriate to a mosque and to the obligations of Muslims:

It is in the houses which God has permitted to be exalted in His name to be remembered therein. Therein do glorify Him, in the mornings and in the evenings.

Men whom neither merchandise nor selling diverts from the remembrance of God and maintaining the ṣalāt and paying the zakāt, they fear a day in which the hearts and the eyes will turn around.

The writing signs on this facade at first glance might appear to be a highly ambiguous juxtaposition of referential dimensions aimed at unclearly defined audiences. Yet these public texts and their layout were astutely chosen for the intricately woven contexts in which they were embedded. Consider first the location of this mosque. Located on the Great Street, the facade was aligned to the street, which made it particularly highly visible to the multi-ethnic, multi-religious pedestrian traffic that passed. The highly legible bands displaying the names and titles of the wazīr were addressed to this broadly based public audience.[50] The titles awarded to wazīrs were both known, discussed, and evaluated by members of the Christian population of Cairo-Miṣr, and they concerned the Muslim population and members of the ruling group.

These writing signs were addressed to a Muslim audience, especially a Fatimid Ismā‘īlī one, when the space in front of the al-Aqmar mosque was used as a stopping place for processions and for viewing the Imām-Caliph on ceremonial occasions. These occasions were many at this time, more than a dozen throughout the year.[51] The al-Aqmar mosque, wazīr al-Ma’mūn’s new construction, supplanted the structures of “forage merchants and the manzara,” [52] or belvedere, where in earlier times the Imām-Caliph had shown himself to those assembled. In wazīr al-Ma’mūn’s time, the space in front of the mosque, as a continuation from the Eastern Palace, became highly charged in these formal moments when the Imām al-Āmir appeared, and in which wazīr al-Ma’mūn was also highly visible. Here the processions stopped, so that al-Ma’mūn could escort the Imām-Caliph into his palace at the end of the procession. It was a stopping place where the wazīr saluted the Imām, and was in turn acknowledged. On the anniversary festivals for the Prophet, ‘Alī, and the Imām, Qur’ān reciters lined up in front of the neighboring palace and listened to the preacher of the al-Aqmar mosque deliver a sermon and prayers for the Imām. The preachers of the al-Ḥākim and al-Azhar mosques followed after.[53] On these occasions within the Ismā‘īlī calendar, it is hard to doubt that the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī audience perceived the sign of Isma‘ilism in the concentric circle medallion and all would notice the names and title of the wazīr who supported the construction.

In restoring and reinventing such ceremonies, wazīr al-Ma’mūn adopted a mode for operating within the ruling structure different from that of Badr al-Jamālī.[54] The times demanded such a change, and the specific selection of Qur’ānic verses on the facade suggests al-Ma’mūn’s sensitivity in dealing with a doctrinal issue that came to be important in expressing the difference between the Fatimid and Nizārī Ismā‘īlīs.

We can probe further into the revolt that threatened the legitimacy, and thus the authority and stability of Fatimid rule at this time, by looking briefly at the dispute over the succession to the Imāmate after the death of Imām al-Mustanṣir in 1094/487. The wazīr then ruling, al-Afḍal, Badr al-Jamālī’s son, arranged to have Nizar, the son of Imām al-Mustanṣir, excluded from succession to the Imāmate. Nizar had been designated by his father as having Divine Light, and thus the heir to succeed him. In his stead, wazīr al-Afḍal was able to have a younger son, Aḥmad, succeed to the Imāmate with the ruling title al-Musta‘li (r. 1094–1101/487–95). Such a switch in the succession caused a major split in the Ismā‘īlī group, because succession and the passing on of the nūr (light) of the Imām were fundamental in establishing the authority of the Imām in the eyes of the Believers. In Fatimid Egypt, the al-Musta‘li line (or what this study calls the Fatimid Ismā‘īlīs) continued, but elsewhere, especially in Seljuk territories (Syria and Iraq), Ismā‘īlīs recognized Nizar as the Imām.[55]

In 1101, al-Āmir, at age five, succeeded his father al-Musta‘li as Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imām. He was helped in this succession by wazīr al-Afḍal, who, under the circumstances of the Imām’s young age, ruled the Fatimid empire. When al-Ma’mūn became wazīr, after al-Afḍal was assassinated in 1121, Nizārī activity increased in Egypt. Wazīr al-Ma’mūn’s actions of supporting public appearances of Imām al-Āmir made strategic sense both within the context of the Nizārī-Fatimid Ismā‘īlī dispute, and in terms of rallying the general population and the ruling group behind the Imām-Caliph, even as the number of Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Believers in Egypt was diminishing.

The subtlety of al-Ma’mūn’s choice of Qur’ānic verses across the doorway of the al-Aqmar mosque indicates his sensitivity to excluding a verse that in fact at that time might have addressed doctrinal disputes among Ismā‘īlīs. The verses on the doorway—Qur’ān 24:36–37 quoted above—are certainly appropriate for a mosque, but they are not the only verses in the Qur’ān that mention such obligations, nor were they the only ones quoted on Fatimid buildings. But on the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque, these verses are taken from the sūrat al-Nūr (chap. 24, sūra of Light) which when displayed on Fatimid buildings usually included the immediately preceding verse (35) where God’s light is likened to a lamp in a glass placed in a niche. This verse is on the al-Ḥākim mosque (see chapter 3), where God’s light relates in the dimension of ta’wīl to the Imām himself. As Ismā‘īlīs, both the Nizārīs and the Fatimid Ismā‘īlīs shared a similar ta’wīl of verse 35, recognizing the Imām as an emanation of the Divine Light which passed from one Imām to another, linking them together. But an expanded Nizārī exegesis of this verse underscored a fundamental doctrinal difference. The nūr gave the Imām even greater spiritual power, manifesting the highest reality, a concept central to the doctrinal differences between these two groups of Ismā‘īlīs.[56]

Given such doctrinal differences, and their immediacy for the Ismā‘īlīs of the capital, it seems to me highly possible that verse 35, appropriate for public display on the outside of the mosque of al-Ḥākim in 1002/393 when Cairo and the northern zone was an Ismā‘īlī area, and the group of Believers was both larger and united behind the recognition of one Imām, was no longer appropriate in 1125/519.[57] At this later date, the population of Cairo and the ruling group were so diverse in composition, and the recent schism had exacerbated this diversity, that the presence of this verse might have led some Ismā‘īlī viewers to inopportune understandings and associations non-supportive of the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imām. The concerns for stability were real, for within five years after this mosque was completed, the Imām himself was assassinated, probably by Nizārī emissaries.[58] Given the context, I would argue that wazīr al-Ma’mūn would not choose to put a verse so religiously and politically charged on display.

Of course, that the verses that were displayed were chosen from the Qur’ānic chapter on Light (surat al-nur) indicates a well-chosen allusion on al-Ma’mūn’s part to the schism and the doctrinal dispute. It may even be that his allusion to light and the Imām was more clever than simply the act of excluding a verse. The large sign of Isma‘ilism over the entrance portal was aesthetically different from any other extant sign of Isma‘ilism in one significant structural respect. The names in the center, as well as the ring separating the center circle from the circle displaying the Qur’ānic verse, are pierced. Sunlight passes over them into the vestibule of the mosque. The results are that the sunlight daily “writes” the names “‘Alī” and “Muḥammad” in shadow within a circle in the mosque’s vestibule. That this sign of Isma‘ilism was consciously designed so that light passed over the names and caused them to appear in shadow as allusion to the Imām, emanation of Divine Light, is supported by the fact that a light screen is unnecessary in so small a mosque where the vestibule is well-lighted from the courtyard.

While this concentric circle medallion may have looked in all its formal aspects like a sign of Isma‘ilism, it is critical to understand that an important change had occurred in one of the functions of the writing it displayed (fig. 36). From the time Imām al-Mu‘izz put the sign of Isma‘ilism on coins, to its appearance on the facade of al-Ma’mūn’s mosque, the evocational field of the Qur’ānic quotation in the outer circle had been bi-valent. The two evocational fields were the Qur’ān and Ismā‘īlī ta’wīl. While, of course, the whole Qur’ān is important to all Muslims, only some verses are directly related to Ismā‘īlī interpretation. The verse displayed in the outer ring of this sign of Isma‘ilism, Qur’ān 33:33, is not a text in ta’wīl. Its specific verse and the words ahl al-bayt (people of the household of the Prophet Muḥammad) are understood and honored by all Muslims. As I have argued elsewhere,[59] to Sunnis the ahl al-bayt are all of the progeny of the Prophet Muḥammad by all of his wives, thus all four of his daughters. In contrast, to all Shī‘ī groups, the concept is more focused, referring only to the descendants of the Prophet’s daughter Fāṭima, her husband ‘Alī, and their two sons, Ḥassan and Ḥusayn.

This change in the evocational base of the text in the outer ring of the concentric circle medallion was made difficult for any literate viewer to discover. Fixed in place over the portal, what the pedestrian can readily read in the outer ring is basmala, which begins at the 3 o’clock position and runs counterclockwise. The Qur’ānic verse, starting in the 11 o’clock position, is mostly upside down to the pedestrian. The gestalt of this sign of Isma‘ilism, its formal or aesthetic qualities, and not the evocational base of its writing is what conveys meaning to those who recognize it. To all others, as argued above, the concentric circle medallion is one format for writing signs used by the Fatimid ruling group.

| • | • | • |

The Text and Wazīrs Bahrām al-Armanī and Riḍwān ibn al-Walakshī

It is worth recounting in brief the strategy that defeated wazīr Bahrām al-Armanī (Bahrām, the Armenian) because it not only tells of the nature of the power struggles in the ruling establishment, it also reinforces one of the recurring themes of this study.[60] That is, it shows that the Qur’ān was the only emblem that could predictably bring all Muslims together, in this case opposing the power of non-Muslims, mainly Armenian Christians. Moreover, it shows that Muslims were consciously using the Qur’ān in the public spaces as such a sectarian emblem. The incident in question reportedly occurred in 1137–38/532. But understanding the issues at stake requires a return to a brief discussion of the serious level the political instability in Cairo had reached.

Another succession crisis that further split the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī group occurred in 1130/524 after the murder of Imām-Caliph al-Āmir. From this schism, the Ṭayyibī Ismā‘īlīs split from those Fatimid Ismā‘īlīs who recognized al-Ḥāfiẓ as the new Imām.[61] This matter is somewhat more complex than the earlier crises. This new crisis illustrates how the diversity of players and groups in the power relations of the ruling elite led to a fragility in the ruling system—and ultimately to the overthrow of Fatimid Ismā‘īlī rule. Coming little more than three decades after the Nizārī schism, this Ṭayyibī crisis involved the murder of an infant heir (al-Tayyib), and reached a climax when the wazīr Abū ‘Alī Kutayfāt (related to both Badr al-Jamālī and Imām al-Mustanṣir) abolished the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imāmate. He took the power in the name of the authority of the Expected Imām of the Imāmī Shī‘ī (or Twelver Shi‘ism).

Ultimately, within a year, wazīr Kutayfāt was himself killed by Fatimid Ismā‘īlī adherents, and Abū al-Majīd was proclaimed Imām with the ruling title al-Ḥāfiẓ, even though he was not a son of the previous Imām. The Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imāmate and Caliphate, more specifically the Ḥāfiẓ-Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imāmate, was thus restored, although, of course, the Ḥāfiẓ-Fatimid Ismā‘īlī group was quite small. The Ṭayyibī schism reduced the Ismā‘īlīs in Egypt almost solely to adherents based in the palace in Cairo. Even after this schism, the Fatimid Imām-Caliph was, of course, still head of the Fatimid ruling system. But he retained that position in even more palpable ways than before solely because the interests of all the groups were best served by maintaining the form of Imām-Caliphal rule, rather than because the Fatimid Ismā‘īlīs had the power to enforce the ruler’s position.[62]

Now, to return to the incident where this section began—the struggle between wazīr Bahrām al-Armanī and the contender for that position, Riḍwān ibn al-Walakshi. In the ensuing disturbances after Imām al-Ḥāfiẓ assumed the throne, the army brought Bahrām al-Armanī to be confirmed as the wazīr.[63] As Ibn al-Muqaffa‘ notes, as a direct result of wazīr Bahrām’s policies the Christians gained influence and positions in the important dīwāns of the kingdom.[64] When “the word of the Muslims weakened,” as he describes it, the Muslims sought to remove Bahrām from office of wazīr. Muslim groups within the army turned to one of their own, an amīr and a Sunni Muslim, Riḍwān ibn al-Walakshi, who declared a jihād against the Christian wazīr Bahrām and his troops.[65] The issues in this struggle involving various Muslim and Christian groups were ones of economic and political power in the Fatimid government. Riḍwān, however, visually emblematized them in a Muslim sectarian reference that brought the Muslim groups together. In the thick of the battle, his troops raised the Qur’ān on their lances as a battle standard.[66]

It was a genuinely brilliant choice. The Muslims understood the message conveyed by using the Qur’ān as emblem, and left the army of Bahrām, who fled with only his Christian troops.[67] Riḍwān’s raising of the Qur’ān as a battle standard recalled the Battle of Ṣiffīn (657 C.E.) where Mu‘āwiya in fighting ‘Alī originally employed the same tactic. Of course, for Sunni Muslims it recalled an action that led ultimately to Mu‘awiya’s gaining the title Caliph, but the initial arbitration at the end of the fighting did not take the title away from ‘Alī. Thus all Muslim army contingents, Sunni (Mālikī, Shafī‘ī and Hanbalī) and Shī‘ī (Ismā‘īlī and Imāmī), could rally around that emblem—the Qur’ān hoisted on a lance. Christians, of course, if we are to believe this widely reported story, did not. At the approach of the fourth decade of the twelfth century, the Qur’ān was being actively used to rally all Muslims in the military elements of the ruling group, and to exclude Christians.

| • | • | • |

Wazīr al-Mālik al-Ṣāliḥ Ṭalā’i‘ and the Public Text

Ṭalā’i‘ ibn Ruzzīk, an Imāmī,[68] was invested as wazīr with the title al-malik al-ṣāliḥ in 1154/549 during yet another time of trouble, when the Imām-Caliph al-Ẓāfir had been murdered and al-Fā’iz became the new Imām-Caliph. Ṭalā’i‘ held the position of wazīr through the six years of Imām al-Fā’iz’s reign into the early days of the reign of the last Fatimid Imām, al-‘Āḍid (r. 1160–71/555–67).[69] Known as avaricious, wazīr Ṭalā’i‘ nevertheless, as the wazīrs before him, was generous in supporting Muslim communal life, and used public texts to display his name and messages.

He built his mosque on the Great Street, like wazīr al-Ma’mūn before him, only he constructed it outside the Bāb Zuwayla (map 3).[70] He is said to have regretted choosing this location because in the unrest in the capital area his mosque was used by insurgents attacking the southern gates of Cairo proper.[71] This mosque, finished in 1159/555 a few months before Ṭalā’i‘ died, has three articulated facades, on the north, south, and west. The west facade facing the Great Street is the main facade and main entrance. The basic layout of these facades share with that of the al-Aqmar mosque important elements: bands of writing that divide a ground of arches in three places (fig. 38). On the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque multiple arches of the same height articulate the facades vertically, rather than as on the al-Aqmar mosque, where the arches were of differing heights. The three bands of writing run the full lengths of the three sides. Like on the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque, the widest one is under the cornice. One is placed about midway, and one at door height. The second band from the top is best preserved, and like the one on the facade of al-Aqmar, displays the name of the Imām, here al-Fā’iz, and the date. The major portion of the inscription displays the names and titles of the wazīr Ṭalā’i‘.[72]

Fig. 38. Exterior, mosque of Ṭalā’i‘

What is important to note is that the public text on these three facades consists of rank and title information, with quotations from the Qur’ān over the doors and windows, and in the upper band. This balance underscores and focuses attention on the very real power of this wazīr who ruled Fatimid lands. He served two Imāms. Imām-al-Fā’iz was a child, and Ṭalā’i‘ kept Imām al-‘Āḍid as virtual prisoner in the palace.[73] The sign of Isma‘ilism is not present on any of the facades of the Ṭalā’i‘ mosque.

Rather, the sign of Isma‘ilism, so closely related to communal memory devices from Ismā‘īlī discourses, is transformed on the facades of the mosque of Ṭalā’i‘ into roundels elaborately filled with geometric forms based on sixty degree angles. These roundels are placed in the spandrels between the arches on the three facades. On the west facade, the blind arches with the articulated hoods so reminiscent of those on the al-Aqmar mosque, also display roundels in their center. At this late date, the only sign of Isma‘ilism continually reissued and displayed is that on coins (fig. 39) where the concentric circle format and writing in circles is maintained. Even the Qur’ānic quotation in the outer ring, 9:33, with its bi-valent evocational field, was maintained. This continuance has much to do with the conservative nature of coinage, and its gold fineness, rather than a recognition of the ideological referents of its concentric circle format.[74] The coin with its recognizable format had come to be recognized and valued for its purity.

Fig. 39a. Dinar, Imām al-Fā’iz (1002.1.890 Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum in the Cabinet of the American Numismatic Society)

Fig. 39b. Dinar, Imām al-Fā’iz (1002.1.890 Collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum in the Cabinet of the American Numismatic Society)

It is understandable that the sign of Isma‘ilism disappeared as a component format for the public text on Muslim sectarian buildings at this time. For approximately four decades, since al-Ma’mūn, no wazīr had been an Ismā‘īlī,[75] while at the same time the number of Fatimid Ismā‘īlīs in the capital area was drastically reduced by schisms. Support for Sunni Islam was on the increase. There was neither patronage to know and to support, nor audience to perceive such a writing sign, especially one placed a distance from the immediate Eastern Palace area. That the concentric circle form, the sign of Isma‘ilism, should be transformed into a roundel displaying geometric designs is in keeping with the history of forms that develop, as the sign of Isma‘ilism did, with specific referents in a social context. Art Deco forms, for instance, in the early twentieth century related to issues of streamlining and speed. In their transformed appearance today, they have lost those specific connotations for most of their audience, and with those connotations aspects of the original form are altered.

| • | • | • |

Processions and the Public Text

On the urban stage of Cairo-Miṣr, the other use of officially sponsored writing was on cloth displayed in the public ceremonies and processions. Our knowledge stems mainly from Ibn al-Ṭuwayr (d. 1220/617), the late-Fatimid- and early-Ayyūbid-period historian whose writings are lost, but whose accounts were cited by al-Maqrīzī.[76] Although I suspect that more writing was displayed on cloth than we can reconstruct with the limited citations al-Maqrīzī uses from Ibn al-Ṭuwayr’s work, these are, nonetheless, sufficient to give some sense of the various functions of writing on cloth displayed in the public space.

In recording the Imām-Caliph’s entrance into the Anwar mosque (al-Ḥākim’s mosque) during Ramadan, Ibn al-Ṭuwayr described the white silk curtains displaying sūras from the Qur’ān rendered in red silk pointed writing (i.e., with diacritical marks) that hung on either side of the mihrab. This description, mentioned in chapter 1, was part of a longer record of the Imām’s entrance into the mosque, a ceremony celebrated by elaborate display in which mihrab curtains were part of the outfitting of the mihrab area where he sat. Three white silk farash (mattresses or spread out cloths) with writing on them were spread on the floor in this area, completing its appropriate dressing in Fatimid official colors.[77] These lavish displays are in the main hard to date, but are part of the restoration of the processions of the Imām-Caliph in the northern part of Cairo begun under wazīr al-Ma’mūn.

Ibn al-Ṭuwayr is also responsible for details about writing in official processions. Describing the New Year’s ceremonial,[78] he records that the banners twenty-one of the Troops of the Stirrup (sibyān al-rikāb) carried in the official procession displayed the phrase nasr min allah fath qarīb (Help from God and Victory Near at Hand), part of Qur’ān 61:13.[79] This writing was variegated in color, and fashioned in silk. Each banner had three tirāz bands placed on the lances of the horsemen.[80] They helped provide a colorful procession, predominantly red and yellow in color.

In a different context, al-Qalqashandī, in a lengthy description of the arms of the infantry, mentioned that they carried a (one) narrow banner of variegated (malawna) colored silk upon which was written nasr min allah wa fath qarib (Help from God and Victory Near at Hand).[81] This single banner was part of the trooping of colors and followed behind two riders from the Special Troops (sibyān al-khāṣṣ), who carried lances each with eight banners of red and yellow dībāj.[82] These two descriptions seem to be of different instances, different troops and somewhat different banner, although displaying the same semantic content. In fact, a Treasury of Banners (khizānat al-bunūd) existed in Cairo, employing 3,000 artisans in Imām al-Ẓāhir’s reign which would have been responsible for fashioning all these banners.[83] Although it is not specifically recorded, presumably the amīrs who headed this treasury (and a similar one for armor and parade adornment) were responsible for the maintenance, provision, and collection of the banners which were taken out and used as the occasion demanded. Fabrication of all of the banners may not have actually occurred in the treasury, yet the officials must have been responsible to procure them. If they were not embellished by these 3,000 artisans, then these various banners must have been procured on special order from weaving establishments, many probably in the Delta.[84]

These banners or, more likely, some related cloth, might possibly be represented in the archaeological textile fragments from this period. Fragments of textiles, mainly decorated bands, displaying nasr min allah (Help from God) in red silk with yellow lattice design on a linen ground are relatively common in museum collections throughout the world. In fact, the embellished area on these textiles is usually woven in what could be described as a tripartite composition. While these textile fragments display part of the semantic content described in the history texts, and also the red and yellow colors mentioned as dominating almost all ceremonies and processions, to our contemporary eyes, they do not fully coincide with the descriptions of the banners bearing this message. Certainly none of the fragments I am aware of displays gold threads.

These instances are to my knowledge the only ones that describe cloth used in public official ceremonies as displaying writing.[85] Hundreds of robes and turbans with elaborate borders are described as being handed out to various members of the ruling group during official distribution of the kiswa.[86] These distributions were extraordinarily lavish in the reign of Imām-Caliph al-Āmir, as one might imagine in such a period of socio-political instability, although they existed in the earlier Fatimid period, too.[87] These same reports even record that the cloth for this distribution was stored in Cairo in the Treasury of the Wardrobe (khizānat al-kiswa) which housed both the clothing for the troops as well as the costly robes for the Imām and other dignitaries.[88]

But no description I am aware of, no matter how lengthy and detailed the record, or how often borders of turbans and robes are mentioned, or even how frequently linen is noted as the ground fabric states specifically that any of this cloth displayed writing. The word most frequently used to describe borders of cloth and clothing is manqūsh. Many scholars have translated this word as “inscribed.” But its medieval meaning, substantiated by medieval dictionaries and the Geniza records, is “embellished,” and I have now come to favor this as the proper translation of the word.[89]Manqūsh, or “embellished,” should probably be seen as an umbrella term that could include written borders, but is not limited to them. Thousands of fragments displaying writing remain today from this period, some from very beautiful and fine cloth, yet we need more evidence than exists currently before they can be attached to these official clothing distributions. Historical accounts thus help us only to a limited extent in understanding the official use of textiles with writing on them and the extant archaeological fragments. Evidence absent is not proof of absent practice, of course. We are simply reminded that written documents and remains of visual culture do not explain each other but function in interrelated ways, in separate tracks, in society.

What is clear is that quotations taken from the Qur’ān were displayed on cloth and elsewhere in ever-increasing numbers in the last two or three decades of Fatimid rule. Such quotations were addressed even more urgently to all Muslims, for their cohesion was the underpinning of the ruling system headed by the Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imām-Caliph. The curtains on the sides of the mihrab in the Anwar mosque (al-Ḥākim’s mosque) are a good example of this practice. Both curtains displayed the basmala and then the sūrat al-fātiḥa (the opening sūra of the Qur’ān). Then on the right one the surat al-jum‘a (62, The Gathering or Congregation) was written, and, on the left, the sūrat al-munāfiqūn (63, The Hypocrites). The former sūra was also displayed in the writing on the western salient outside this very mosque. This sūra is most appropriate for the location of its display because it refers to Friday prayers. Its placement in the mihrab of this Friday mosque then would have been comfortable for all Muslims. Likewise, sūra 63 discusses the role of the Messenger of God and those who do not believe in his mission. This chapter, too, had relevance for all Muslims especially in the social circumstances of the late Fatimid period, when those who did not recognize the message or the Messenger (namely, the Christians), so dominated the ruling group.

These same kinds of associations and audiences were evoked by the semantic content of the writing on the banners, naṣr min allāh wa fatḥ qarīb (Help from God and Victory Near at Hand). On one level it was a battle cry for all Muslims against their enemies. Yet, on another level, this phrase and the words from it were important in Fatimid Ismā‘īlī practice. Qāḍī al-Nu‘mān, for example, understand them to refer to the Qā’im and to the resurrection.[90] Also, these were (and are) the names of the two main gates of Cairo. Outside the Bāb al-Naṣr the muṣalla was located where the Imām and ruling group and Believers processes on ‘Id celebrations. In the later Fatimid period, processions for the New Year exited from the Bāb al-Naṣr and re-entered Cairo through the Bāb al-Futūḥ, the site of the Anwar mosque (al-Ḥākim’s mosque). These two words, as mentioned above, were also part of the quotations from the Qur’ān placed under the dome before the mihrab where these curtains hung in the mosque of al-Ḥākim.

The accounts described above also give details about the aesthetic and territorial functions or meanings of these same writings. As in the earlier period, the lavishness of the display in which the writing on textiles was embedded was intended to convey to the participants, as well as to the beholders, the power and thus the stability of the ruling group; they were increased in number over time as the government grew more unstable and, predictably, wazīrs turned over rapidly. The more the personnel in powerful positions changed, the greater was the need for processions which continually re-hierarchized (to themselves and to the urban audience) the members of the ruling group by their order in the processional ranks.[91] If the number of processions and ceremonies was in reverse proportion to the stability of the government, so, too, was the amount of display in terms of the drain on available governmental resources to support it.[92]

While Ibn al-Ṭuwayr’s description of the lavish display of gold and jeweled fabrics and trappings rivals that of Nāṣir-i Khusraw, the changing taxation and troop payment systems meant that the Imām-Caliph and the palace establishment had less monetary resources than earlier to support such lavishness. In addition, the wazīrs had their own processions and sections of the processions. Thus the display of gold and jewels and colors represented a greater distance between the display of power and its actuality in the later Fatimid period than it did in the former.

In each of these descriptions of writing, we are told that the writing was in silk—usually on silk or brocade cloth. These comments on the aesthetics of the writing conveyed to the reader information both about the quality of the writing and the cost of production. Silk, of course, was probably imported and thus expensive. Mentioning silk as a medium distinguished the fibre in which the writing was rendered from the dominant fibre in the processions, namely linen, which was locally produced. By noting inscriptions and other elements, especially when they were red or yellow, Ibn al-Ṭuwayr was probably also signalling a quality distinction to his readers. To mention red and yellow was to note two very expensive colors produced from dye substances obtainable only on the international market.[93] By contrast, for example, to have commented on blue as a textile color would not have evoked such connotations of luxury, because blue was produced from indigo, a common local dye.

In short, what might appear from the descriptions of the aesthetic and territorial functions of writing on cloth to be the “same” display of power in terms of the consumption of expensive commodities by the ruling group in both the early and late Fatimid period was in fact something quite different. Neither the meaning of the medium nor the message of the writing in these processions was the same.

We could ask when the writings we do know about were included in these ceremonies and what we might infer from this timing. The ceremonies in which writing on cloth was reported were those broadly based in the Muslim calendar. The historical accounts that record them, however, are all undated. But considering that Ibn al-Ṭuwayr was the source, and noting where these stories were placed in the sequence of al-Maqrīzī’s recounting of Fatimid practice, the earliest moment that this writing on cloth could have appeared was probably late in the reign of Imām-Caliph al-Ḥāfiẓ (r. 1131–49/525–44). Al-Ḥāfiẓ might well have been the Imām that Ibn al-Ṭuwayr described as entering the Anwar mosque during Ramadan; and his troops might well have been the ones displaying the phrase naṣr min allāh wa fatḥ qarīb< (Help from God and Victory Near at Hand). Whether the moment was then, or later, knowledge about the shifts in the composition of the army and within the ruling group as a whole, as well as about the audience addressed, helps us understand more clearly the full import of the writing.

The reports of cloth with writing on it described above specifically refer to the semantic content of the writing. These displayed words from the Qur’ān, and thus obviously were taken from a Muslim referential field—a clearly different evocational base from that of the writing displayed in the procession described by Nāṣir-i Khusraw in chapter 3. Those who were in the Anwar mosque at the time the Imām entered during Ramadan, and those who displayed the banners in the processions, were, by late in the reign of al-Ḥāfiẓ, mainly Muslims who had just engaged in a struggle to reduce the Christian influence in the ruling establishment. They had succeeded in defeating wazīr Bahrām al-Armanī and his troops.[94] The semantic message of all of this writing publicized triumph and victory in Muslim sectarian terms.

| • | • | • |

Exterior, Interior, and Writing Signs

Thus far in this chapter the considerations of the Fatimid use of writing signs have focused on writing in the public space, public texts, beginning with the writing signs of Badr al-Jamālī. The referential dimensions of writing in the public space were used by him and by succeeding wazīrs to disseminate specific kinds of information about the changing social order, namely the growth of the power of the wazīrate and the military as indicated by the elaborate titularity of the wazīr. The aesthetic and territorial dimensions of those writing signs functioned both to distinguish Muslim sectarian practices of displaying writing signs from those of other sectarian groups, and within Muslim sectarian practices, to blur the distinction between the practices of displaying writing on the inside and outside of structures.

While it is difficult to reconstruct the visual practices of the medieval Coptic community in relation to writing signs with any certainty, most historians agree that Coptic churches and monasteries remained unarticulated by the display of writing on the exterior.[95] The display of officially sponsored writing was reserved for the interior, and there it was used in a traditional manner: a secondary sign framing images, with references to the Book and community, in the script style of the Book. Thus, beginning with Imām-Caliph al-Ḥākim’s golden curses and the writing placed on the exterior of the mosque outside the Bāb al-Futūḥ and continuing to the mosque Ṭalā’i‘ built outside the Bāb Zuwayla, the display of writing on the outside of Muslim sectarian structures built by the Fatimid ruling group distinguished them from other sectarian structures. They displayed public texts.

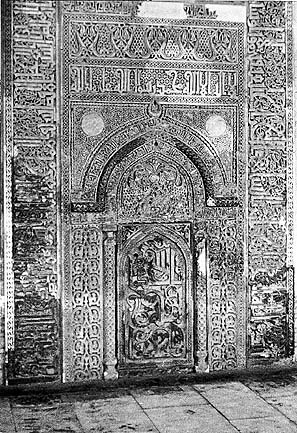

The aesthetic dimensions of displaying writing signs on the interior of Muslim communal structures also underwent a change at the same time. In the al-Ḥākim mosque, as noted above, writing became a primary sign for elaborating the interior. It no longer framed depictions as in traditional practice, or as in the contemporary practice of using writing signs inside Christian space. This new display of writing on the interior was maintained in the later Fatimid period in both extant mosques, the al-Aqmar (fig. 35) and that built by Ṭalā’i‘ (fig. 38). It also characterized the gifts or additions that wazīrs of this period made to the interior of existing structures: for example, the mihrab al-Afḍal added to the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn around 1094/487 (fig. 41),[96] and the restorations to the mausoleum of Sayyida Ruqayya, 1130–60 (fig. 42). Of course, it was not simply the display of writing but writing in Kufic script in a variety of ornamented styles that became a primary visual sign on the interior of Muslim communal spaces. Medium also served as a visual link. Carved and incised stucco was the primary medium for the display of writing on the interior surfaces of both mosques and mausolea. Writing signs in Kufic script incised in stucco bound together and identified those structures supported by the Fatimid ruling group. Displaying writing, and seeing the display of writing, became a visual convention in Muslim communal spaces, mosque and mausolea, and for Muslim audiences throughout the capital area.

Fig. 41. Mihrab donated by wazīr al-Afḍal in mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn

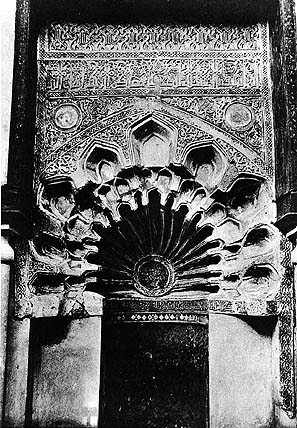

Fig. 42. Interior, mausoleum of Sayyida Ruqayya, after Creswell. Muslim Architecture of Egypt, vol. 1

One aesthetic practice of displaying writing on Muslim communal buildings in this later period blurred what centuries of tradition had maintained, namely, a distinction between the uses of writing signs on the exterior and the interior of communal structures. The layout of a central large arch flanked by two smaller arches with bands of writing first described by Nāṣir-i Khusraw on the kiswa of the Ka‘ba in Mecca in 1050/441 was used for both the exterior and interior of Muslim sectarian spaces, primarily those sponsored by wazīrs. It is found in structures throughout the Cairo-Miṣr urban area and in the Qarafa cemetery[97]—for example, on the outside of the al-Aqmar mosque in Cairo, on the qibla wall inside the mausoleum of Ikhwat Yūsuf in the Qarafa,[98] and on both the qibla wall and on the portico of the mausoleum of Sayyida Ruqayya on the Great Street near Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn.[99] This basic layout is rendered in different media: carved stucco in the mausoleums, and stone on the outside of the mosque. In this difference in medium it is possible to read a hierarchy of materials, as well as, perhaps, in the social status of the structures within the society. While differences exist in the details of the specific variations of the layout of the arches and bands in every structure, most of these arched layouts also include roundels.

The basic aesthetic similarities of these arched layouts providing the framework for officially sponsored writing mask the referential differences in the writing displayed on the interior and exterior of these Muslim communal structures. The components of the evocational fields of the writing, and in tandem with that, the allocation of space to each component, on the interior and exterior of structures are seemingly mirror opposites of each other. On the outside, rank and title information is detailed and lengthy, while quotations from the Qur’ān are limited relative to these social references.[100] On the interior, the Qur’ān is the main evocational field, although the donor’s name and minimal titles may appear.

Roundels were a part of this arched layout, and the appearance of this form on buildings brings us to the important consideration of what happened to the sign of Isma‘ilism as a component of officially sponsored writing in this later period. As part of the public text, its appearance remains constant on coinage in this period. Even the Qur’ānic quotation (9:33) chosen at the time of Imām-Caliph al-Mu‘izz is maintained in the outer ring of the coin (fig. 39). Obviously, as the number of Ismā‘īlīs in the Cairo urban area decreased substantially, the specific meaning of this concentric circle format was perceived by only a very small audience trained to recognize its referents. Yet maintaining the sign of Isma‘ilism on coinage is explicable by the conservative nature of coinage itself, the strong linkage between its aesthetic form and its material value, particularly with the gold dinar, and the fact that many are struck. The situation in regard to coinage then is not unlike that now what with the Masonic signs on the back of the U.S. one-dollar bill. These signs were imbued with a particular meaning in relation to the Masonic ceremonies important to the founding fathers of the U.S. Today these Masonic signs are maintained on the dollar to validate the “realness” of the dollar, even though the audience who understands their original referent is limited.

In contrast, however, the form and content (or semantic referent) of the sign of Isma‘ilism dissolves both as part of the public text on the exterior of buildings, and as part of an Islamic sectarian one on the interior. This dissolution results in a semi-autonomy of form and content enabling the form and its content (or referents) to have separate trajectories. Naturally, the form or format lasts longest in the visual culture. It is like an empty shell left by a creature on the beach. The referent, like the creature who inhabits the shell, is most fragile, depending on complex social relations and the configuration of a certain kind of discourse, here Ismā‘īlī discourse.

This dissolution of form and content did not happen sequentially or evenly in Fatimid society. Look at the round form in the central arch on the facade of the al-Aqmar mosque (fig. 36) and that in the central arch in the mausoleum of Sayyida Ruqayya (fig. 42). Both these displays of writing in a round form are products of the last fifty years of Fatimid patronage. Seeing the play and slippage between the form and content of these two round forms helps us understand the complex ways form and content are layered.

On the portal of the al-Aqmar mosque, the roundel preserved the form of the sign of Isma‘ilism: the al-Ḥākim period variant, lines of writing displayed in a central core surrounded by outer, concentric circles which included writing. The center displays the names “Muḥammad” and “‘Alī,” both appropriate to both Ismā‘īlī and general Muslim discourses. The outer ring displays Qur’ān 33:33, “God only desires to take away uncleanness from you, Oh people of the household.” While meaningful to all Muslims, this verse is not cited in Ismā‘īlī ta’wīl. Until this time, the reference base of the writing in signs of Isma‘ilism, whether on buildings or on coins, has been bi-valent and included reference within Ismā‘īlī ta’wīl. Contemporary coins maintain this bi-valent reference. Here, on the al-Aqmar mosque, the form of the sign of Isma‘ilism is preserved, but not the full range of the content.

In the mausoleum of Sayyida Ruqayya, restored within thirty years of the construction of the al-Aqmar mosque, the form and content (referent) of the roundel have dissolved even more. The writing displays the same semantic content as that in the roundel of the al-Aqmar mosque, yet not in the same round form. Rather, it is displayed within the arch and roundel format together. The round form is preserved, but the center is expanded so as to be almost coterminus with its perimeter. In this center, the names “Muḥammad” and “‘Alī” appear, but the writing is displayed in an interlocked geometric pattern. This interlocked pattern is not at all related to the conventions for the presentation of writing in either the sign of Isma‘ilism or in the diagrams in Ismā‘īlī discourse. While the content, or evocational field, of the writing in the center is the same as that on the facade of al-Aqmar, the form in which the writing is displayed dissolves the visual relationship between this writing and that on al-Aqmar and the diagrams in Ismā‘īlī discourse.

No concentric circle of writing surrounds these names in the center. The band of writing above the roundel, on the mihrab itself, displays the same part of Qur’ān 33:33 as displayed in the outer ring on the al-Aqmar roundel. The round form in this mausoleum is the shell left behind by a creature on the beach. It becomes a vehicle for other uses. Those uses include the display of writing, as well as the display of geometric forms and other devices, like on the facade of the mosque of Ṭalā’i‘. The Ismā‘īlī content has left this shell—perhaps to another form.

In the last one hundred years of Fatimid rule, knowledge of Ismā‘īlī discourses reached fewer and fewer people as avenues of Sunni learning increased. The audience who knew and could perceive signs of Isma‘ilism became very circumscribed, a condition affecting both patrons and viewers. In this later period of Fatimid rule, Muslim communal structures, especially mausolea, were rebuilt and restored by non-Ismā‘īlī wazīrs as a means of fostering a type of religious piety and devotion among all Muslims, separating them from the substantial Christian minority within the population and ruling group.[101] This was essentially a conservative action supporting the status quo in the government—a ruling system that was headed by a Fatimid Ismā‘īlī Imām but which was otherwise composed predominantly of non-Ismā‘īlī Muslims.[102] The support of such buildings was facilitated during this period by the presence of the Crusaders in Palestine. Muslim pilgrims preferred to skirt some of the shrines in that area and visit the Egyptian capital instead.[103] The appearance of pilgrimage guidebooks gives evidence to the relevance of these structures to Muslims of all madhhabs (law traditions). It is not surprising, then, that in these structures, the writing, officially sponsored by non-Ismā‘īlī wazīrs and addressed to a primarily non-Ismā‘īlī audience referred to the Qur’ān and individuals important in the collective general Islamic memory, and not to referents in Ismā‘īlī sectarian discourse.

Indeed, the use of writing by various members of the Fatimid ruling group, especially in the public space, turned the capital area into a more obvious text. The issue of using a city as “text” when applied to social practice of this period, involved the population attending to different but co-existent meanings implicit in a single text. Messages could be read, as we have above, in the semantic content of the words. They could be read in the long expanses of writing in expensive materials, and in the multiplicity of styles of script and formats of writing placed on buildings. Such readings also entailed attending to subtle nuances given to existing texts as new texts were added to the visual environment, when successive mosques were added southward along the Great Street, or dropped, as when writing was no longer displayed in concentric circle formats. To the beholder who walked this road, the writing on the mosque (as well as the buildings themselves) presented an extraordinarily diverse display: differences in scale, nuances in style, and plurality of messages.

Notes

1. While the basic periodization in this text is by the dates of the patriarchs, events effecting the Coptic community, and indeed the entire population of Miṣr are recorded. Ibn al-Muqaffa‘, History of the Patriarchs, vol. 3, pt. 1, is relevant to this second half of Fatimid rule.

2. These problems have been well documented in the medieval sources—Muslim, Christian and Jewish. A basic list includes: al-Maqrīzī, Itti‘āẓ 2:325–34, 273–76, 280–97; Ibn al-Muqaffa‘, History of the Patriarchs, vol. 2, pt. 3, 290–315. Twentieth-century analysis of these times includes: De Lacy O’Leary, A Short History of the Fatimid Khaliphate (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Polk Ltd., 1923), 210–216; Bernard Lewis, “An Interpretation of Fatimid History,” Colloque International sur l’histoire du Caire, 27 mars–5 avril 1969 (Cairo: General Egyptian Book Organisation, 1972), 287–95.

3. Abū Najm Badr al-Jamālī al-Mustanṣiri al-Ismā‘īlī was wazīr from 1073–1094/466–87. Armenian in origin, he was a mamluk who was manumitted and joined the Fatimid army. He headed an Armenian contingent of troops loyal to him. Before coming to Cairo, he had been governor of Damascus. A convert to Islam, his madhhab, or rite, is agreed upon by many writers as Ismā‘īlī. Still others insist he remained Armenian at heart.

4. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 1:335.

5. William Hamblin, “The Fatimid Army during the Early Crusades” (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1984), 19–27.

6. See al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 1:305, 337, 364. Some details about this period are found in MAE 1:119. For an interpretation of some of the effects of these problems, see Paula Sanders, “From Court Ceremony to Urban Language: Ceremonial in Fatimid Cairo and Fusṭāṭ,” in The Islamic World from Classical to Modern Times, ed. C. E. Bosworth, Charles Issawi, Roger Savory, and A. L. Udovitch (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 316–18.

7. In this fortification and expansion of the walls of Cairo he included the mosque of al-Ḥākim within the city. This was the moment that the great defensive gateways were built: Bāb al-Naṣr, Bab-al-Futūḥ, and the Bāb Zuwayla as we know them today. Details on the archaeology and architecture of these gates and their enlargement are provided by MAE, vol. 1, chaps. 10, 11.

8. Al-Afḍal, Badr al-Jamālī’s son, who succeeded his father as wazīr, moved his residence to Fusṭāṭ. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 1:451–52; Ibn al-Muqaffa‘, History of the Patriarchs 3:35–36.

9. Sanders, Fatimid Cairo, 73–82, 94–98, 127–34.

10. The distance to the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn from the Bāb al-Futūḥ along the Great Street is about three kilometers (1.9 miles). Walking that distance today can be accomplished in about forty-five minutes. Processions, of course, must have covered the distance at a more stately pace.

11. See especially the map by Louis Massignon, plate 2, in his article “La cité des morts au Caire,” Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archaeologie Orientale 57 (1958): 25–79.

12. This mosque is published in MAE 1:241–46; its exterior inscriptions are recorded in MCIA, Egypte 2:171; RCEA 8:146–47; for an interpretation different from the one offered below, see Caroline Williams, “The Cult of ‘Alīd Saints in the Fatimid Monuments of Cairo, Part I: The Mosque of al-Aqmar,” Muqarnas 1 (1983): 37–53. Another mosque, known as the Fruitsellers Mosque (al-Fakahani) was built by Imām-Caliph al-Ẓāhir in 1149/544 in the southern part of Cairo. Today only the doors are Fatimid. For the reign of this Imām-Caliph, see O’Leary, A Short History; and “Fatimids,” Encyclopaedia of Islam.

13. This mosque as been published, albeit somewhat schematically, by Creswell, MAE 1:275–388. Its modern restoration was undertaken in difficult social circumstances and times, both local and international. World War II, for instance, halted the reconstruction before the Comité de Conservation des monuments de l’art Arabe solved the problem of the minaret. The original Fatimid minaret was destroyed in the earthquake of 1303/702. For all of the issues, see Comité de Conservation des monuments de l’art Arabe, compte rendus des exercises, 1911: 22; 1912: 81; 1913: 52; 1915–19: 550–51, 728–29; 1930–32: 96–98, 103–19; 1936–40: 249, 273–76; 1941–45: 56. See also Bierman, “Urban Memory,” 1–12. The inscription on the exterior of this mosque was published in RCEA, no. 3231; MCIA, no. 46. This inscription is incomplete in these texts and has been published complete in Journal Asiatique (1891), plate 1; and in Comité de Conservation 1915–19: 41–42. These inscriptions were read by Youssouf Effendi Ahmed, Inspecteur du Services. The upper band of the inscription was totally effaced at the time the comité undertook the restorations. The state of this cornice inscription was conveyed to me by Dr. ‘Abd al-Azīz Sadiq from the last living survivor from the comité who worked on this reconstruction. Thus, while it is known that two bands of writing originally existed, the semantic content (even the aesthetic dimensions) of the upper band remain unknown to us today.

14. In 1089, Badr al-Jamālī replaced the original mausoleum built by a ninth century Abbasid governor, with a larger structure. Yūsuf Ragib, “Al-Sayyida Nafīsa, sa légende, son culte, et son cemetère,” Studia Islamica 44 (1976): 68–69.

15. The extent of his power is most tellingly revealed in a collection of letters from Imām al-Mustanṣir, his mother, and others to the Sulayhids of the Yemen: ‘Abd al-Mun‘im Majīd, ed., Al-Sijillat al-mustansirīyya (Correspondence de l’Imām al-mostancir) (Cairo, 1954). See also Husain F. al-Ḥamdani, “Letters of al-Mustanṣir bi’allah,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 7 (1933–35): 307–24.

16. Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-a‘sha 4:270; MCIA, vol. 1, pt. 4, Arabia, 95. The Fatimid color was white; see chap. 1.

17. Geoffrey Khan, “The Historical Development of the Structure of Medieval Arabic Petitions,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 53 (1990), pt. 1, 8–30, esp. 29, where he comments about the role of Badr al-Jamālī in setting the titulature and format.

18. Gaston Wiet, “Une nouvelle inscription Fatimide au Caire,” Journal Asiatique (1961): 13–30. Some evidence suggests that this practice was also followed by others in the ruling group. For example, ‘Alī Pasha recorded a mosque (no longer extant, known only by this account) off the Great Street with a large plaque over the entry port bearing the name of ‘Amīr Za‘im al-Dawla Juwamard, a retainer of wazīr al-Afḍal, dated 1102/496. ‘Alī Pāshā Mubārak, Al-Khitat al-tawfiqīyya al-jadīda, 10 vols. (Cairo: Būlāq, 1306H), 2:85–86. He quotes al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 2:85–86, the latter suggesting that people felt that this structure was a mashhad for Ja‘far al-Sadīq.

19. EMA 2:336 and plate 97b. Creswell notes that the restoration could “not have amounted to much.” But for the purposes here we know that he put a plaque on the outside of the structure on the southern entrance of the northeast side of the ziyāda.

20. CIA, Egypte, vol. 1, no. 11, plate 2; no. 1, plate 17. The marble plaque is 260 cm x 45 cm and displays four lines of Arabic. It was located on the northeast corner, by a main door which today is walled up.

21. Wiet, CIA, Egypte 1:31–32 discusses this inscription. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 2:268 comments about the condition of the districts of al-Qaṭā’i‘, and al-‘Askar. See also Yaacov Lev, State and Society in Fatimid Egypt (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1991), 99.

22. See MAE, vol. 1, chap. 10; ‘Alī Pāshā Mubārak, Al-Khitat al-tawfiqīyya 2:83, for the inscription on the Bāb al-Barqiyya near al-Azhar in the name of Badr al-Jamālī.

23. A marble plaque is recorded in MCIA, Egypt 1:63–64; RCEA 7:248–49. This action is mentioned in al-Maqrīzī, Itti‘āẓ 3:449.

24. This inscription and the similar ones over the doorway into the mosque and on the interior of the Nilometer are known only through the description, translation and drawings of Marcel in Description de l’Egypte, 128–29, 151–84. MAE 1:217–18 published an abbreviated synopsis of Marcel’s work. The mosque was destroyed by French inattention barely a decade after Marcel recorded its existence.

The plaque, according to Marcel, was 70 cm. x 569 cm. (27 ½ in. x c.18 ½ ft.). Marcel notes that the only way to see this inscription was by boat.

25. This list of what is extant is but a small portion of what Badr al-Jamālī constructed. He, for instance, built a new palace for himself in Cairo so he did not have to live in the palace where preceding wazīrs had lived. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 1:438, 461, 464.

26. Marcel, Description de l’Egypte, 128–29, 151–84.

27. Ibid., 196–98.

28. Ibid., 194.

29. This phrase, which while used in the Qur’ān to begin chapters, was nonetheless very commonly used in social practice. It is interesting to note that the first two words of this phrase, bismi ‘lahi, in the Name of God, were, of course, used by all Christian groups who spoke and wrote Arabic to begin their salutations, “In the name of God,…” which continued differently from the Muslim one, and often differently among Christian rites.

30. Q 9:18 (beginning only): “Only he can maintain the mosques of God who believes in God and the Last Day, and maintains the salāt and pays the zakāt and fears God”; and part of 61:13: “Help from God and Proximate Victory.”

31. See chap. 3.

32. For the abandonment of the processions, see Sanders, Fatimid Cairo, 67–69.

33. He was known by his title—al-Ma’mūn. His name was Abū ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Ajall.

34. He was the son of a Fatimid dā‘ī in Iraq and entered the service of the previous wazīr, al-Afḍal. He was arrested in 1125/519, accused of plotting against Imām al-Āmir, and executed (along with his brothers) in 1128.

35. Imām al-Āmir was put on the throne when he was five years old by wazīr al-Afḍal.

36. Ibn al-Ṣayrafī, Al-Ishara ila man nala al-wizarah, ed. ‘Abd Allah Mukhlis (Cairo, 1924), 11, editor’s comment.

37. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat 2:169.

38. Ibn Muyassar, Akhbar Miṣr, 62.

39. See note 12 above.

40. The reconstruction of this mosque was completed in the 1990s. At that time the south third of the facade was built anew by replicating the extant third.

41. Nāṣir-i Khusraw, Safar-nāma, 133–34. Nāṣir-i Khusraw’s description says that “below and above these bands the distance was the same, so that the height was divided into three parts.” This tripartite equal division was not replicated on the facade. Safar-nāma, 133.

42. It might even be suggested that the gray-white stone medium of the facade which gave the name “al-Aqmar”—the moonlit—to the structure was equivalent to the white, Fatimid royal color of the covering.