3. Judah Moscato: A Late Renaissance Jewish Preacher

Moshe Idel

| • | • | • |

One of the great challenges of Jewish cultural history is to properly understand the transmission and transformation of the medieval Jewish heritage in the Renaissance period. Renaissance thought was a highly eclectic and artificial configuration of disparate religious and philosophic traditions of the ancient and medieval past, brought together under a single intellectual roof conceived to be a universal and ancient theology called prisca theologia. The latter did not constitute a single overarching theory of knowledge like the great medieval summae, but rather a simultaneous disclosure of a vast variety of systems juxtaposed each against the other in order to determine a hidden affinity among them all. Within this new synthesis, the kabbalah was assigned an honorific place by both Christian and Jewish intellectuals.

Important treatises on the kabbalah were brought to Italy in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by Spanish Jewish intellectuals who were heirs to a tradition of collecting and elaborating upon a body of ancient mystical lore that can be traced back to at least the thirteenth century. Despite the great attraction this material held for both Christians and Jews, few could understand its content accurately. This was so not only because of the highly symbolic language of much of this literature, but because it was composed in an entirely different spiritual ambiance, as part of the activity of small groups who employed idiosyncratic terminology in order to convey traditions they had received, innovations they had innovated, or experiences they had experienced. The well-known episode of the sixteenth-century Safed kabbalist, Isaac Luria, who spent entire days trying to fathom the meaning of certain passages of the classic book of the Zohar, well illustrates this fact, one still not fully appreciated even by modern scholarship.[1]

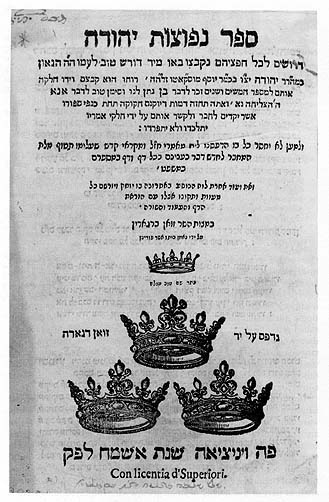

Title page from Judah Moscato’s Sefer Nefuẓot Yehudah (Venice, 1589). Courtesy of the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

The problem of understanding the Spanish kabbalistic corpus was even greater in Italy. The new students of the kabbalah in Italy in the early 1480s had to overcome the reticence, sometimes even the hostility, of an earlier generation of Italian Jews who had focused primarily on medieval forms of Jewish philosophy.[2] This younger generation of men like Yohanan Alemanno, David Messer Leon, or Abraham de Balmes, also had to study the complex kabbalistic writings without any authoritative guidance or any institutionalized curriculum, as had been the case in Spain.[3] In addition, they faced an even greater “handicap.” These new kabbalists had been exposed, to a certain degree, to both medieval philosophy and humanistic culture prior to their encounter with kabbalistic literature. This training could, and, in fact, did affect their reading of religious sources that derived from so different a manner of thinking.[4] Understandably, they experienced considerable difficulties in reading Zoharic passages, and they felt more comfortable with philosophical expositions of the kabbalah.[5]

When Judah Ḥayyat, a conservative Spanish kabbalist, arrived in Mantua about 1495, he was appalled by the kind of books students of the kabbalah were studying. He compiled the first index of texts he thought should be prohibited, and in its place, proposed his own preferred list.[6] He was particularly incensed by the novel speculative interpretations of the kabbalah that had taken root on Italian soil where individuals studied on their own, without the support and anchor of kabbalistic conventicles, as had been the case previously in Spain and later in Safed. Ḥayyat’s negative reaction was the result of this complex encounter between two different cultures: that of the more open environment of Italian Jews with that of the more particularistic and conservative tendencies of Spanish kabbalists.

Assuming Ḥayyat’s testimony to be reliable in characterizing the state of kabbalistic studies in Mantua in the 1490s, and I see no reason to doubt it, does it suggest a pattern or tradition of study found particularly in Mantua well into the next century, including the period in which Judah Moscato [c. 1530–c. 1593], the subject of our study, lived? A rapid survey of several Mantuan authors and their sixteenth-century writings illustrates the formidable problem of arriving at any simple conclusions.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, the Mantuan kabbalist, Berakhiel Kafmann (b. 1485), attempted to harmonize kabbalah and philosophy as did some of his older contemporaries, by labeling kabbalah an “inner philosophy.”[7] Despite this general approach in his only extant book, the Lev Adam, however, he suprisingly neglected to mention any precursors in Mantua, including the most illustrious Mantuan student of the kabbalah, Yohanan Alemanno.

But neither is there any mention of Kafmann’s work in Nefuẓot Yehudah, the collection of sermons of Judah Moscato. Moscato nevertheless copied lengthy quotations from him and even praised him extensively in his later commentary on Yehudah Halevi’s Kuzari.[8] At about the same time, the Sefer Mekor Ḥayyim, the super-commentary of the fourteenth-century Castilian Jewish thinker, Samuel ibn Zarza, on Abraham ibn Ezra’s biblical commentary, was printed in Mantua in 1559. Despite its strong speculative concerns, and despite Moscato’s keen interest in ibn Ezra, I could find no trace of this work in Moscato’s writing.

Other examples are forthcoming to illustrate the problem of facilely characterizing the intellectual ambiance of sixteenth-century Mantua. In 1558, the Ma’arekhet ha-Elohut, a systematic and speculative exposition of some trends in thirteenth-century Kabbalah, was published in Mantua. In the fourteenth century, it had been interpreted in a relatively Aristotelian manner by the Italian kabbalist, Reuven Ẓarfati.[9] At the end of the fifteenth century in Mantua, Judah Ḥayyat criticized this commentary and composed his own, entitled Minḥat Yehudah, based almost exclusively on pure kabbalistic sources, the Zohar and the Tikkunei Zohar. We might assume that Ḥayyat’s act was an expression of his allegiance to the antiphilosophical trend of Spanish kabbalah, but such an assumption is too simplistic. Despite his sharp denunciation of Ẓarfati’s commentary, Ḥayyat was actually influenced by it and even quoted it extensively.[10] When the 1558 edition of the Ma’arekhet ha-Elohut appeared, the publishers decided to include larger sections of Ẓarfati’s commentary, notwithstanding the explicit statement of one of them, Emanuel Benvienito, that he opposed Ẓarfati’s philosophical orientation in interpreting kabbalah.[11] In the end, however, only the most “pernicious” passages of Ẓarfati’s text were purged and the rest was printed with Benvienito’s apparent approval. And precisely in the same period, Judah Moscato saw fit to quote Ḥayyat’s antiphilosophical commentary in his own work on the Kuzari,[12] although the thrust of the commentary with its heavy emphasis on Zoharic theosophy and theurgy is not reflected at all in Moscato’s thinking.

These examples amply illustate the danger of extrapolating from the intellectual ambiance of a specific locale a particular and consistent intellectual direction of an individual writing there. In our specific case, it would be hazardous to characterize the nature of Moscato’s thinking solely on the basis of several contemporaneous works printed in his city, including the much disputed printing of the Zohar.[13] Indeed, as we shall soon see below, restricting Moscato’s intellectual horizons to these Jewish writings alone might even distort a proper account of his intellectual posture.

In lieu of reducing Moscato’s thought to the sum total of ideas and books in a certain place and time, let us widen our investigation to consider the larger social background of two public controversies that took place in Mantua in the decade preceding his death and in the decade following it. The first controversy, in which Moscato was moderately involved,[14] arose from the publication of Azariah de’ Rossi’s historiographical work, the Me’or Einayim. The author’s employment of critical methods in determining matters of Jewish chronology, a rather skeptical approach regarding the veracity of rabbinic legends, and an exhaustive use of non-Jewish sources provoked a critical reaction from several conservative rabbis in northern Italy.[15] The second controversy took place around 1597 regarding the sermons of the young rabbi David Del Bene.[16] He was accused of introducing mythological motifs (in fact, the only specific example adduced by his accusators was a reference to Santa Diana), and of interpreting the Jewish tradition in an allegorical manner. Though Moscato had died five years earlier, David Del Bene’s son, Yehudah Assael Del Bene, mentioned Moscato’s name as the source of inspiration for David’s fine rhetoric, insinuating that David’s indiscretions were somehow attributable to Moscato.[17]

In both cases, the authors were criticized but not excommunicated. Azariah continued to hold his views; Del Bene implicitly recanted, restrained himself from interpreting the Jewish tradition in the manner of his earlier years, and was eventually nominated to become a communal rabbi. Second, both controversies took place in the same place and roughly in the same time period, indicating a wider issue than the mere idiosyncratic opinions of two Mantuan Jewish authors. The few extant documents of the Del Bene affair indicate that the preacher attracted large audiences,[18] and his more conservative critics were obliged to listen indignantly, but silently, to his preaching.[19] Further, as Robert Bonfil has suggested, the rabbinic manifesto which attempted to restrict the circulation of de’ Rossi’s provocative book met with limited support; the most important rabbinic authorities preferred a more moderate and quiet response.[20] Consequently, although both controversies were provoked by relatively extreme opinions, they seem to have been tolerated by the majority of the community, since only a minority openly opposed them.

In light of these two events, it is easier to understand the penetration of Renaissance motifs into Moscato’s sermons. In comparison to his two contemporaries, he appears to have responded more moderately to Renaissance influences, retaining a strong sense of Jewish identity without becoming “out of fashion.” At the same time, the stimulus of Renaissance culture surely helped to shape his “selective will”[21] in passing over recently published Hebrew books printed in Mantua in favor of motifs and ideas taken directly from his Christian environment. Common to the two controversies and to Moscato’s enterprise in particular is an effort to make sense of the Jewish past, as Robert Bonfil has formulated it,[22] either through a new historical interpretation, in the case of de’ Rossi, or by a “modern” figurative recasting of rabbinic aggadah, as in the case of Moscato and Del Bene. Accordingly, we should conclude that the appropriate context of Judah Moscato’s thinking should be located not merely in the library of available Hebrew books in Mantua in his time but also, and, in my opinion, more importantly, in the dynamic interaction between ideas and their social settings, something which is less easily reconstructed and even less definitively demonstrated.

| • | • | • |

Judah Moscato’s two books have not attracted the attention of most scholars who deal with the history of the kabbalah. His book of sermons, the Nefuẓot Yehudah,[23] has been treated mostly in the context of homiletical literature[24] with little interest in the work’s actual ideas. Moscato’s commentary on the Kuzari, called the Kol Yehudah,[25] has been virtually ignored. We shall be concerned here mostly with Moscato’s sermons, not for their literary achievement (an area outside my specific scholarly competence), but as a testimony to the author’s ideas and as reflections of the Jewish intellectual ambiance in Mantua during the second half of the sixteenth century. My neglect of the literary aspect of his writing does not indicate a lack of appreciation for its literary significance; Joseph Dan has convincingly shown that Moscato’s sermons were indeed masterpieces of Jewish homiletical creativity.[26]

I am, however, skeptical about the possibility that these difficult texts were ever delivered as sermons in any synagogue, at least in the Hebrew form we possess. There is presently a scholarly dispute regarding the language that served Italian Jewish preachers in the sixteenth century.[27] Robert Bonfil assumes that it was exclusively Italian,[28] while Joseph Dan asserts that it was both Hebrew and Italian.[29] Dan insists, however, in the particular case of Moscato, that his printed sermons were “undoubtedly” delivered in Hebrew.[30] This assumption implies that in their present form, Moscato’s sermons closely approximate what he presented in the synagogue. According to Dan, the sermons themselves supply both direct and indirect indications of the fact that he spoke Hebrew.

It seems to me, however, that Dan neglected an important aspect of the sermons in reaching such a conclusion: the complex nature of their content. Should we assume that so many difficult and sometimes highly obscure passages (even difficult for Israeli graduate students in Jewish thought!) could possibly have been presented by a preacher orally to a largely unlearned audience? Could his congregation have understood what he was talking about? This may represent no great obstacle for one who assumes that the Lurianic kabbalah, a highly complex theosophy in its own right, became the accepted theology of Judaism shortly after Moscato’s death.[31] But it appears more reasonable to assume that only a very few Jewish intellectuals were capable of grasping the presentation of so many diverse sources adduced and manipulated by Moscato in so sophisticated a manner, and even fewer could have followed an oral exposition of the same material as it has reached us in print.

Moscato’s sermons should accordingly be treated as part of the literary legacy of Italian Jewish culture, providing reliable evidence of intellectual developments not always fully documented in other sources. And being written documents prepared by the author for publication, they have a different objective, at least from the perspective of the social group to whom they were addressed, than sermons delivered in the synagogue.

Thus, for example, when Moscato quotes Pico della Mirandola’s commentary on Benivieni’s Songs of Love, regarding the son of God, we might properly assume that by the middle of the sixteenth century, some Jewish writers were more willing to cite medieval and Renaissance Christian authors than were their counterparts a century earlier, and even more so than were their counterparts of the Middle Ages.[32] This is different, however, from concluding that it was plausible for a preacher to deliver such material from the pulpit of his synagogue! When David Del Bene introduced allegorical or figurative interpretations of Greek mythologies into his sermons some years later, a controversy immediately erupted, providing us a precious indication of the limits of Jewish tolerance during the sixteenth century. The more natural locus for close interaction between the two religions was in written and learned documents rather than in public forums. The fact that Moscato’s implicit comparison of an ontological interpretation of the divine son with the view of the ancient Jewish sages passed with little notice, while Del Bene’s innocent remarks exploded into a public debate, suggests the correctness of my assumption.

| • | • | • |

How can we describe Moscato’s general cultural attitude? There are at least three possible responses: (1) he was still deeply influenced by medieval thought, though traces of Renaissance influence are also detectable in his writing, the view of Herbert Davidson;[33] (2) he was fully aware of Renaissance culture, but, at the same time, remained a proud Jew deeply contemptuous of Christological interpretations, and was essentially unaffected by external influences in the shaping of his own views, the position of Joseph Dan;[34] or (3) he was deeply affected by Renaissance culture and it left a noticeable imprint on the essential character of his thought.[35] The first two responses were formulated primarily on the basis of an examination of the eighth sermon in Moscato’s collection.[36] In what follows, I shall attempt to argue in favor of the third response, based on my own analysis of the same sermon as well as material found in sermon thirty-one. My main argument is that two different Hermetic views stemming from Renaissance sources informed the exegesis of the Jewish material in each of the two sermons. I would like to emphasize that these views are not only quoted, a fact that is undeniable in any case, but, I believe, they also constitute the hermeneutic grille for the speculative interpretations of these sermons.

The eighth sermon is the shortest and one of the most accessible of the entire collection. It is also the most frequently quoted in modern research.[37] It deals with the origin of the garment of light, which, according to the Midrash, was used by God to wrap the world when he created it. Taking as his starting point the Midrashic text in Bereshit Rabbah,[38] Moscato describes the nature of the first creature, then mentions the general affinity between the view of Plato and the ancient Jewish sages.[39] He asks rhetorically if such an affinity can be found in this specific case. In response to his own question, he quotes an unnamed Platonic source that states that the first creature was designated as “His son, blessed be He.” How are we to understand this citation? For Joseph Dan, it represents “a clear and unequivocal” reference to Jesus Christ and indicates Moscato’s negative attitude toward Christological interpretations.[40] Such a reading is questionable, however. Let us examine the source more closely. Moscato describes the first emanation as follows:

By the emanation of the aforementioned cause,[41] God, blessed be He, not only created everything, but He also created them in the most perfect way possible. And it [the cause, this first emanation] is called, in the words of the Platonists and other ancient sages [by the name of]: “His son, blessed be He,” as the wise Yoan[42] Pico Mirandolana[43] testified in his small tract on celestial and divine love. And I was aroused by this to reflect that perhaps the sage among all men [Solomon] had intended this when he said: “Who has ascended heaven and come down…Who has established all the extremities of the earth? What is his name or his son’s name if you know it?” (Proverbs 30:4)[44]

Moscato, following Pico,[45] attributes the appellation of the first emanation as son to the ancient, implicitly pagan, philosophers. Since “Jesus” or “Christ” is not mentioned explicitly, nor is it implied, there is no reason to regard this appellation as Christological. This discussion is rather part of the well-known enterprise of Pico to discover correspondences between Christian and pagan theological views, without assuming the ancient pagans were Christians, even hidden ones. Who were these ancient pagans? Pico, in his Commento, mentions the names: “Mercurio Trimegisto e Zoroastre,” surely not Christians for either Pico or Moscato.

The Hebrew phrase “Beno Itbarakh” should be translated, as we do above, as “His son, Blessed be He,” where “He” stands for God, not the son. Pico translates this phrase simply as “figliuolo di Dio,” namely, the son of God. Interestingly enough, Pico is careful not to introduce a Christological understanding of this Hermetic or Zoroastrian “son.” In fact, he explicitly cautions that people should not confuse this son with the one designated by “our theologians” as the son of God. The Christian “son” shares the same essence as the father and is equal to him, but this “son” of the ancient philosophers, in contrast, is created and not equal to God.[46] If Pico himself refrained from Christianizing the pagan notion, and had even cautioned against such an identification,[47] Moscato would have had no religious inhibitions about using the term “son.” The intellectual context for this usage was aptly described by Harry A. Wolfson: “In the history of philosophy an immediate creation of God has been sometimes called a son of God. Thus Philo describes the intelligible world, which was an immediate creation of God and created by Him from eternity.”[48]

In addition to this ancient usage, Wolfson also mentions that Leone Ebreo and Azariah de’ Rossi, contemporaries or near-contemporaries of Moscato, and even Spinoza, also used it in a similar fashion. Unfortunately, Wolfson missed the quotations of Pico and Moscato above, as well as an additional manuscript source worth citing in this context. Its importance is threefold: it supplies a medieval addition to Wolfson’s list, which could otherwise be interpreted as merely the influence of Philo on two Jewish thinkers who lived in the Renaissance period; it illustrates that this philosophical definition of “son” is not as unusual as we might imagine; and it helps clarify the passage from Moscato’s sermon, the subject of our inquiry. Rabbi Levi ben Abraham, a well-known and controversial figure of late thirteenth-century Provence, wrote the following in his Liviyat Ḥen:

“Tell me what is His name” [Proverbs 30:4] because granted that His essence is incomprehensible but to Him, [His] name is written in lieu of Himself. “What is the name of His son?” [30:4] hints at the separate intellect that acts in accordance to His command, who is Metatron, whose name is the name of his Master,[49] and he [Metatron] also has difficulty in understanding His true essence [Amitato] and in conceptualizing it [Leẓayer mahuto]…the [separate] intelligences are called His son, because of their proximity to Him, and because He created them without any intermediary.[50]

This medieval text clearly demonstrates how the separate intellect can be described as the son of God, as Pico and Moscato describe it, without any Christological connotation. Moreover, Moscato, unlike Pico, uses the same quotation from Proverbs found in Levi ben Abraham’s discussion. This may be a sheer coincidence since Liviyat Ḥen was not a well-known text. Whatever the case, Moscato might have learned of this usage from this or from another still unidentified source.

Before concluding our discussion of the “son” passage, let us consider Azariah de’ Rossi’s usage in his Me’or Einayim, a text, we will recall, written in Mantua several years before Moscato had reached his prime. The two certainly knew of each other; Moscato even quoted de’ Rossi, in his Kol Yehudah. De’ Rossi writes: “It is merely a manner of terminology whether it is called son or emanation or light or sefirah or idea as Plato cleverly puts it.”[51]

Again in this instance, “son” has no Christological association but is merely one of those terms which describe the first entity. I am not sure that Philo was the origin of de’ Rossi’s view here, as Wolfson seems to imply. Despite de’ Rossi’s acquaintance with Philo,[52] his reference to Plato and the term “idea” suggests that Pico might have been his direct source. Be that as it may, Moscato’s sermon, like de’ Rossi’s comment, far from being in conflict with Christianity, was in concert with a Neoplatonic Hermeticism currently in fashion during the Renaissance period. In demonstrating how the rabbinic usage of the term correlated with Hermetic and Neoplatonic concepts, Moscato was engaged in a positive rather than a negative polemical enterprise.

What then is the significance of Pico’s and subsequently Moscato’s special usage of the concept of son? Both authors contributed to the philosophical discussion of the idea of “son” not so much under the influence of Philo but under the influence of Renaissance Hermeticism,[53] and both thinkers subscribed to the “extradeical” version of the Platonic ideas in their interpretations.[54] While Pico consciously avoided identifying the philosophical notion of “son” with a theological one, Moscato was less reticent: he proposed the identification of “son” with the Torah itself.[55] In this instance at least, Moscato, and not Pico, facilitated a rapprochement between ancient theology and his own religion.

In this context let me raise Davidson’s assumption that Moscato is merely a medieval thinker, despite his occasional Renaissance blandishments. Admittedly, quoting Pico does not certify Moscato as a Renaissance thinker. Pico himself quoted ancient and medieval opinions. To capture what is new in Pico, and consequently in Moscato, we need to consider more than their ideas; we must observe the peculiar manner or the structure in which these ideas were presented, or in the words of Cassirer, their dynamical interaction.[56]

Pico was called the dux concordiae by Marsilio Ficino, an epithet that epitomizes his special approach. In the Commento passage, the search for concordance is obvious: Plato, Hermes Trismegistus, and Zoroaster were all unanimous in designating the first creature by the term “son.” This open or sometimes hidden affinity between the ancients underlies Pico’s philosophical enterprise as part of the general direction of the more comprehensive prisca theologia.[57] The same search for correspondence informs Moscato’s approach. Neither Pico nor Moscato claimed historical filiation between the ancients and the truths of their own traditions. When Moscato indicated in his sermon that “the views of Plato are approaching the view of our sages,” he was not arguing, as he had done elsewhere, that Plato was actually influenced by priests or prophets. He was, instead, interested in discovering a phenomenological affinity between historically disparate religious and philosophical ideas. As such, Moscato’s approach here is different from the common assumption of medieval and Renaissance Jewish thought that Plato had actually adopted Jewish concepts.[58] Moscato implicitly recognized an independent source of truth belonging to Plato and the ancient philosophers, and consequently chose to compare it with the Jewish one. If Plato was a mere “offspring” of rabbinic sapience, what would be the sense of such a comparison? From this perspective, Moscato comes closer to Pico than to any of his Jewish medieval and Renaissance predecessors.[59] As he had done in another case where he rejected Aristotle’s alleged Jewish roots,[60] he also did not insist here on the view that what is good must be Jewish.

Interestingly enough, Moscato refrains from adducing kabbalistic sources in this context, texts which were certainly available to him.[61] In his Theses, Pico had mentioned that ḥokhmah, the second sefirah of the kabbalists, was identical with the Christian son.[62] Either Moscato was unaware of this text or was reluctant to mention so blatant a Christological reading of a Jewish text.

I reiterate my original point. Given its complexity and the confusion it engenders even among modern scholars, I wonder whether such an exposition of the correspondence between the Jewish view of primordial light, the Torah’s light, and the Platonic and pagan views of the created son could actually have been presented within a synagogue sermon! On the contrary, Moscato would surely have avoided such an oral discussion. As he himself acknowledged elsewhere in a partially apologetic and revealing passage:

Let it not vex you because I draw upon extraneous sources. For to me, these foreign streams flow from our own Jewish wells. The nations of the earth derived their wisdom from the sages. If I often make use of information gathered from secular books, it is only because I know the true origin of that information. Besides, I know what to reject as well as what to accept.[63]

In his discussion of the son, writing for a discerning audience of readers who could appreciate his perspective, he accordingly found no reason to exercise any censorship in quoting Pico’s provocative statement.

| • | • | • |

Moscato’s sermons reveal his general knowledge of and attitude toward the kabbalah. He occasionally quoted kabbalistic passages, especially from the Zohar, which, as we have mentioned, was already in print. Yet these citations in themselves do not indicate that he was very interested in, or able to decode accurately the intricacies of, Zoharic mythical and symbolic thought. Rather he seems only superficially to have absorbed this mythological material in a manner reflecting more the spirit of Italian Jewish culture in the sixteenth century than that of its original authors. The parallel emergence of Greek mythology and Spanish kabbalistic mytho-theosophy constitutes a very significant development in the consciousness of Italian Jewry of Moscato’s era. Both literatures were subjected to the same strategy by Jewish readers: figurative interpretation. It started, mainly insofar as Greek astral mythology is concerned, with Leone Ebreo’s Dialoghi d’Amore, and it continued in more moderate forms throughout the next century, including instances in Moscato’s own writing. The figurative, allegorical interpretation of the kabbalah is found in the writing of Yohanan Alemanno at the end of the fifteenth century, and continues well into the seventeenth century. Moscato was one of the few Italian Jewish thinkers interested in both bodies of literature and he used both their mythologies in his own writing.

As an example, I would like to present Moscato’s treatment of the nature of God found in a lengthy sermon called The Divine Circle. There is no doubt that this is one of the most important sermons in the collection, not only because of its length and richness, but because its major theme reappears in another sermon[64] and in his later work, the commentary on Judah Ha-Levi’s Kuzari.[65] Because of the diversity of citations and the sermon’s length, we shall confine our analysis to a partial presentation of the main simile: the image of the center and the circle. We begin with Moscato’s presentation of the kabbalists’ view of the first sefirah:

See how the sages of truth [Ḥakhmei ha-Emet, namely the kabbalists] revealed to us the meaning of this circle. Sometimes they draw the sefirah of keter as an entity, surrounding and encompassing the other sefirot from without, but sometimes they [draw it] in the center as a point within a circle. And I found the following statement in the book Sha’arei Ẓedek [of Joseph Gikatilla, 1248–c. 1325]: “Keter encompasses all the sefirot and that is why it is called soḥeret, derived from the word seḥor seḥor [roundabout]. Malkhut is called dar [resides],[66] since it serves as the residence of the Lord.”[67]

According to Moscato, there are two different descriptions of the sefirah keter: it is sometimes symbolically referred to as a circle, while, at other times, as the point that is the circle’s center. Moscato was certainly accurate regarding the first description. The ten sefirot are often pictured as ten concentric circles, the first and most comprehensive being keter, the last and the center being malkhut. In rare instances does one find the inverse description: keter is at the center and malkhut is at the extremity. However, I am not acquainted with any kabbalist who describes the first sefirah as both the circle and the center. Later in the same sermon, Moscato interprets the relationship between the last sefirah, malkhut (also referred to as atarah, diadem), and “God,” apparently alluding to the sefirah tiferet, as that of the circle to its center.[68] The author understood Israel’s encircling God by means of a diadem as hinting at the simile of the center and the circle.

The juxtaposition of two divergent views found in different sources is not unusual in kabbalistic literature, certainly not in the harmonizing atmosphere of the sixteenth century. Prima facie, here was merely another exercise in kabbalistic associative creativity. The primary incentive for such associations, however, was to establish a more systematic structure of kabbalistic theology by integrating two disparate positions, to reconstruct an alleged lost unity. Thus, for example, Moses Cordovero, Moscato’s earlier contemporary, proposed a synthesis of two earlier theories of the nature of the sefirot, one that maintained that they were part of the divine essence, and one that maintained that they were instruments or vessels of divine activity. Cordovero argued that two different types of sefirot existed, each closely related to the other.

In contrast, Moscato juxtaposed two different kabbalistic views in order to advocate a third, namely, that the same entity can be defined as being both the circle and the center. What is surprising is that Moscato overlooked a rather common kabbalistic representation of the relationship between one of the lower seven sefirot and the other six as that between the center of the circle and six extremities of the circle’s circumference. This view was widespread from the end of the thirteenth century,[69] and it was reiterated by several older contemporaries of Moscato in Safed. Even a diagram of this representation can be found in print in one of the kabbalistic texts Moscato might have known: Elijah de Vidas’s Reshit Ḥokhmah.[70] Moscato nevertheless apparently ignored what is, perhaps, the closest kabbalistic parallel to his definition of God.

Instead, Moscato found an illustration of his idea of the center and the circle in a different source:

And the letters of the Tetragrammaton hint at it: the yod represents a point as its shape is like a point, whereas the he and vav allude to a circle since they are circular numbers, as Abraham Ibn Ezra stated in his commentary on Exodus [32:1]. I shall also invoke the verse: “They shall praise Your name in a dance [maḥol]” [Psalm 149:3], this term being derived literally and semantically from the term ḥozer ḥalilah [literally, “turns around”].

The strongest and most authoritative name of God, the Tetragrammaton, is exploited to extrapolate the idea of center and point, again in a rather artificial way. The letter yod, because of its form, stands for the center, whereas the two other letters represent the circle, since their numerical equivalents, five and six, are circular numbers, namely, their square value ends with the same figure: twenty-five and thirty-six. Moscato puts together the shape of one letter with a certain numerical property of two others in order to confirm his view. However, the tendentious nature of this interpretation becomes obvious when we observe that the letter yod also stands for a circular number, ten, as Abraham ibn Ezra had pointed out. Moscato conveniently ignored this simple fact to illustrate his image of the center and the circle.

What was his reason for so artificial a reading? The answer lies in the definition of God mentioned in a source he immediately cites: “In Mercurio Trimegisto it is written that the Creator, blessed be He, is a perfect [or complete][71] circle,[72] whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.”[73]

After adducing this view of Hermes Trismegistus, Moscato exclaims: “See how wonderful is this matter that something that is neither a center nor a circumference is, at the same time, both a center and a circle.” Only at this point, and not earlier, following the quotations of ibn Ezra and the kabbalists, does Moscato express his strong emotion. Moscato was citing a well-known definition of God that recurs in Christian pseudo-Hermetic sources from the twelfth century on.[74] To judge from his Italianate spelling of Hermes Trismegistus, it appears that Moscato quoted an Italian source. Whatever the source, we should point out that the same definition was adumbrated earlier in the same sermon:

The term makom[75] is proper to Him, blessed be He, either under the aspect of point or under that of circle. Under the aspect of circle it is proper [to use the term makom] because of the resemblance to the supernal circumferent [sphere] which is the locus of everything that is placed within it. Under the aspect of point it is proper because of the resemblance to the center that is like the locus of the supernal sphere, which is not surrounded by anything outside it.[76]

A preliminary observation is necessary regarding the terminology of this citation, as well as that of the pseudo-Hermetic passage. Moscato does not use the Hebrew equivalent for the Latin sphera that occurs in all Christian citations of the above definition. This is especially evident in the last quote, where the supernal sphere is mentioned explicitly, but only as part of a simile, while the author really had a circle in mind. This was done apparently in order to facilitate the interpretation of the aforementioned Hebrew texts that use the metaphors of circle and center, but not sphere. We might then assume that Moscato adapted the non-Jewish source to the Hebrew texts and created a new version of the pseudo-Hermetic definition of God. He resorted to the image of the circle rather than the sphere because the sefirot were depicted as circles and points.

Moscato similarly does not mention the idea of infinity as it relates to the sphere mentioned in the Christian texts, but substitutes the idea of perfection. This change might be explained by the fact that he related his analysis to the sefirot (that is, the finite aspect of the Divine known to human beings) and not to the ein-sof (the infinite aspect of the Divinity unknown to human beings). Why he ignores the concept of ein sof when referring to the concept of God’s infinity in the pseudo-Hermetic source is not clear.

We can approach Moscato’s passages simply as an interesting discussion, albeit ignored until now, of a well-known pseudo-Hermetic definition of God. Moscato’s integrative effort of combining these two kinds of sources was facilitated by their common origin in Neoplatonism, a medium whereby spiritual entities were interpreted through imagery derived from geometry.[77] Such Plotinian images, ultimately stemming from Empedocles and Plato, underwent several transformations in the Middle Ages and influenced both the kabbalah and this pseudo-Hermetic source. Yet Moscato’s integration of the two definitions in two disparate theological corpora is unique. It provides a striking illustration of the significant contribution of Hebrew sources to the study of Western ideas, sources usually unexploited in most contemporary scholarship.

What is more pertinent for our discussion, however, is the fact that the concept Moscato chose to employ in his description of the first sefirah came directly from the pseudo-Hermetic source. Moscato’s reading of the kabbalistic source was not organic, based on the internal development of the text, nor originating from the privileged position of the Jewish tradition. Rather it was guided by the adoption of a view external to Judaism, a view considered important enough by Moscato to impose its meaning on certain rabbinic, philosophic, and kabbalistic passages. Was this done consciously? Did Moscato actually believe that the Jewish sources reflected the same view as that in the Hermetic definition? This is a crucial question, which is, at the same time, a very difficult one to answer. What seems to be strange in this case is Moscato’s utter failure to mention the idea frequently expressed elsewhere in his sermons that the Jewish sources inform the external ones. Perhaps he intentionally modified the Jewish texts to fit the non-Jewish one. But such a conclusion would appear unwarranted for an author who probably believed that all the Hebrew sources he marshalled for making his parallels surely fit his interpretation. Indeed, in the same sermon Moscato declares: “We shall be called the priests of the Lord by our attribution of the simile of the point and circle to the glory of the splendor of God,[78] blessed be He.”[79]

This identification of the believers in the pseudo-Hermetic definition of God with His priests surely illuminates the author’s sense of the Jewishness of the position he had presented. Why he believed as he did, however, is a question that transcends a strictly philological analysis of the text; it requires a wider examination of the larger context of Moscato’s cultural milieu.

| • | • | • |

A tentative response to the above question might be that the general culture in which Moscato lived was so powerful, and the intricacies of his Hebrew sources were so great, that we may suppose he inadvertently misinterpreted a Hebrew text in order to fit a pattern familiar to him from the study of non-Jewish thought. This answer, which, prima facie, seems to be rather implausible, is based on the assumption that there were few experts in the kabbalah in sixteenth-century Italy, and that they generally avoided the most formidable kabbalistic text, the book of the Zohar. This appears to be the reality from the end of the previous century well into the next century, even after the Zohar was published in 1558 both in Cremona and Mantua, since no Italian kabbalist in the sixteenth century ever wrote a commentary on the Zohar. In Safed, in contrast, such commentaries in the second half of the sixteenth century were most common. Even at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the mythological and symbolic aspects of the Zohar still remained elusive to most Italian students of kabbalah. Like the medievals who had struggled to understand the anthropomorphic expressions of the Bible and Midrash through the exegetical technique of figurative interpretation, they similarly labored to make sense of the kabbalah, which they viewed as an extension of Midrash.

Despite the impact of newly arrived Spanish kabbalists in Italy after 1492, both Jewish and Christian kabbalists continued to engage themselves in a certain type of mystical philosophy and hermeneutics rather than in a theurgical lore emphasizing the centrality of Jewish ritual activity. This dichotomy between the kabbalah in Italy and that of Safed seems to be generally reflected even in the writing of Mordecai Dato, Moscato’s friend who studied for several years in Safed with Moses Cordovero. And even after Moscato’s death, the dichotomy seems to have remained more or less evident. When Lurianic kabbalah reached Italy from Safed, it was absorbed and reinterpreted in accordance with the more speculative frame of mind of the Italian kabbalists.

This phenomenon, of course, is not entirely new. In thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Spain, several students of the kabbalah interpreted it philosophically. Their guiding principles, however, were mediated through Jewish philosophy, which had derived them, for the most part, from Arabic Aristotelian or Neoplatonic philosophies. It is only very rarely that we find a Spanish kabbalist who directly used Scholastic terminology to interpret Jewish mystical lore.

Not so in Italy, where the use of Scholastic concepts was not generally mediated by an already established Jewish form of Scholastic philosophy. Italian Jews, from the thirteenth century on, freely borrowed concepts and motifs from Christian theology and medieval Latin literature. By the sixteenth century, Italian kabbalists similarly borrowed from Christian theological sources. They, and those inclined to kabbalistic study like Moscato, functioned as did the medievals in freely appropriating non-Jewish thought into the study of Jewish texts. Moreover, in the Renaissance and post-Renaissance periods, the kabbalah, because of its theological and hermeneutical pliability, became the main avenue of intellectual acculturation into the outside world. Its affinities with Neoplatonism and Pythagoreanism facilitated a reciprocal interaction between Jewish and Christian ideas. Thus kabbalah in Italy simultaneously developed in two ways: it absorbed Neoplatonic and Hermetic elements related to its own concepts, and it either ignored, suppressed, or reinterpreted its more theurgical and theosophic elements by means of speculations recently imported from non-Jewish sources.

Our brief analysis of Moscato’s treatment of kabbalistic sources illustrates how Italian culture often shaped the way Jewish thinkers interpreted the kabbalah on its arrival from Spain or the Ottoman empire. Moscato’s appropriation of the pseudo-Hermetic definition of God and his adaptation of Jewish sources to it reflect a much wider phenomenon of assimilation reflected in this period in a wide variety of fields: science, historiography, literature, art, and music. Eschewing the theurgical views so characteristic of Spanish kabbalistic treatises, he concerned himself with speculative and ethical issues. Thus, when Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen referred to Moscato’s achievement in a sermon of his own, he mentioned, in a veiled critique of Moscato himself, that people “spurn the substantial food that nourishes and strengthens,[80] and hanker after the delicacies, the sweet tidbits that titilate the palate but leave the body unfed.”[81] This more conservative rabbi of Padua and Venice clearly understood that his distinguished colleague had entangled himself in aesthetic and theological concerns at the expense of halakhic ones.

The main processes shaping Moscato’s attitude toward the Jewish tradition, as discussed here on a very small scale, parallel those involved in any kind of strong cultural hermeneutics.[82] In his case, they include: (1) suppression of the theurgical approach of the Zoharic kabbalah; (2) emphasis upon speculative elements in Jewish literature more in consonance with Renaissance views; and (3) absorption of non-Jewish ideas which inform an already distorted presentation of Jewish texts. In principle, these were important contributions of the Christian Renaissance hermeneutic grille (to use Couliano’s phrase once again) in interpreting Hebrew texts and ideas.

The approach I am advocating does not fit the portrayal of the proud and contemptuous Moscato who looked down on the achievements of the Renaissance; nor does it confirm the marginality of Renaissance thought for Italian Jews. If there are instances where a superiority complex is expressed by Jews in this period, this “assertion of superiority can be a sign of weakness and decline,” as Robert Bonfil has felicitously formulated it.[83]

Indeed, my examination of the reception of the kabbalah by Italian Jewish authors of the late sixteenth century confirms for me another of Bonfil’s conclusions regarding the shift of moods within Italian Jewish culture. A century earlier, during the Renaissance, Jews were more creative and culturally assertive; by Moscato’s day, their culture had become more derivative and dependent on the larger milieu than before.[84] By the late sixteenth century, the Christian Renaissance had left its strong and pervasive imprint on its Jewish minority. The Jews participated in this cultural experience more by imitation than by creative assertion. With the arrival of Cordoverian and later Lurianic forms of kabbalah in Italy by the 1580s, new ideas circulated among some Jewish intellectual circles, infusing some vitality into a weakened and declining Jewish intelligentsia. Only then was kabbalah more widely recognized as a major religious force by a significant elite group among Italian Jews.[85]

The intense study of kabbalah by both Jews and Christians in Italy, and the philosophical, mainly Neoplatonic, interpretation of this lore, a feature of the Renaissance period, provoked a reaction—a Jewish counter-Renaissance in the seventeenth century—whose major expression was a sharp critique of the kabbalah. A silent negative response to the mythological-kabbalistic-Hermetic amalgam of Moscato’s sermons, and perhaps to the Renaissance cultural tastes of Mantuan Jews in general, can be found in the sermons of Leon Modena, who, even in his youth, had retreated from the enthusiastic reception that kabbalah and Renaissance culture had been given in previous generations.[86]

Notes

Many thanks to the editor, Prof. David Ruderman, whose careful reading of this study and suggestions for improvement contributed substantially to its final form.

1. See Meir Benayahu, ed., Toledot Ha-Ari (Jerusalem, 1967), pp. 319–320.

2. See Moshe Idel, “The Magical and Neoplatonic Interpretations of Kabbalah in the Renaissance,” in Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, ed. Bernard D. Cooperman (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), pp. 218–219.

3. Cf. Solomon Schechter, “Notes sur Messer David Léon,” Revue des études juives 23 (1892): 126. It should be mentioned that in contemporary Spain the study of Kabbalah was part of the curriculum of some yeshivot; see Joseph Hacker, “On the Intellectual Character and Self-Perception of Spanish Jewry in the Late Fifteenth Century” [Hebrew], Sefunot 2, no. 17 (1983): 52–56.

4. See Moshe Idel, “Between the Concept of Sefirot as Essence or Instrument in the Renaissance Period,” [Hebrew] Italia 3 (1982): 91 and note 16.

5. Ibid., pp. 89–90.

6. See Moshe Idel, “The Study Program of R. Yohanan Alemanno” [Hebrew], Tarbiẓ 48 (1979): 330–331.

7. See Moshe Idel, “Major Currents in Italian Kabbalah between 1560–1660,” Italia Judaica (Rome, 1986), vol. 2, pp. 248–249.

8. See e.g. Kol Yehudah (Warsaw, 1880), book 4, section 86, fol. 63a. The profound influence of the “Divine Chapters,” as Moscato calls Kafmann’s book, is an issue that should preoccupy any serious study of Moscato’s thought.

9. See Ephraim Gottlieb, Studies in the Kabbala Literature, ed. Joseph Hacker [Hebrew] (Tel Aviv, 1976), pp. 357–369.

10. See e.g. Sefer Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut (Mantua, 1558), fol. 61b.

11. Ibid., fol. 3b–4a.

12. See e.g. Kol Yehudah, book 3, fol. 71b; book 4, fols. 24ab, 64a.

13. See Isaiah Tishby, Studies in Kabbalah and Its Branches [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1982), vol. 1, pp. 79–130.

14. See David Kaufmann, “Contributions à l’histoire des luttes d‘Azariah de’Rossi,” Revue des études juives 33 (1896): 81–83.

15. See Robert Bonfil, “Some Reflections on the Place of Azariah de’ Rossi’s Meor Einayim in the Cultural Milieu of the Italian Jewish Renaissance,” Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, pp. 23–48.

16. See David Kaufmann, “The Dispute about the Sermons of David del Bene of Mantua,” Jewish Quarterly Review o.s. 8 (1896): 513–524; and see Robert Bonfil’s essay in this volume.

17. Ibid., p. 516, n. 3.

18. Ibid., pp. 518–519.

19. Ibid., p. 518.

20. Bonfil, “Some Reflections,” pp. 28–29.

21. See Ioan P. Couliano, Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, trans. M. Cook (Chicago, London, 1987), p. 21.

22. Bonfil, “Some Reflections,” p. 36.

23. In the following, I use the edition of Warsaw, 1871.

24. See below, note 29.

25. I use the Warsaw 1880 edition.

26. See note 29 below.

27. See the detailed presentation of the two views and the pertinent bibliography in Marc Saperstein, Jewish Preaching, 1200–1800: An Anthology (New Haven, London, 1989), pp. 39–43.

28. Robert Bonfil, Rabbis and the Jewish Communities in Renaissance Italy (Oxford, 1990), pp. 301–302: “Throughout this period Jewish sermons were delivered in Italian as was the practice in the Christian milieu.”

See also the evidence related to a sermon of Shlomo Molkho delivered in Mantua, which was attended not only by Jewish adults but by Christians and children as well, a definitive proof that Spanish or Italian was the language of the sermon; cf. Saperstein, ibid., p. 51, n. 19, and Moshe Idel, “An Unknown Sermon of Shlomo Molkho” [Hebrew], in Exile and Diaspora, Studies in the History of the Jewish People Presented to Prof. Haim Beinart, ed. Aaron Mirsky, Abraham Grossman, Yosef Kaplan (Jerusalem, 1988), p. 431; there is still further evidence that each time Molkho preached in Rome princes and priests and a multitude of people attended, again a convincing indication of the language of his sermons. See also the text printed in A. Z. Aescoli, Jewish Messianic Movements [Hebrew], 2d ed. (Jerusalem, 1987), p. 409. Another bit of evidence, found in a neglected manuscript of Rabbi Jacob Mantino, regarding the use of Italian as the language of preaching at the middle of the sixteenth century, will be discussed elsewhere. From the evidence related to the sermons of David del Bene in Mantua, it seems reasonable to assume that they were also delivered in Italian; see Kaufmann, “The Dispute,” p. 518.

29. See Joseph Dan, “The Sermon Tefillah ve-Dim‘ah of R. Judah Moscato” [Hebrew], Sinai 76 (1975): 209–232; idem, “The Homiletic Literature and Its Literary Values” [Hebrew], Ha-Sifrut 3 (1972): 558–567.

30. Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1971), vol. 12, col. 358: “It is possible that Moscato preached both in Hebrew and in Italian.…However, the sermons collected in Nefuẓot Yehudah were undoubtedly delivered in Hebrew.”

31. See Joseph Dan, “No Evil Descends from Heaven,” in Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, p. 103. Dan asserts that Cordovero’s and Moscato’s thought had created a gap between theology and the communal and personal experience of Jews, and this gap was overcome by the Lurianic myth at the beginning of the seventeenth century. However, I assume that, in any case, Moscato’s views were understood only by the very few, and those of Luria by even fewer persons. Whether mythical Lurianism prevailed at the beginning of the seventeenth century in Italy or not is an issue still to be proven. See also below note 85.

32. See Shlomo Pines, “Medieval Doctrines in Renaissance Garb? Some Jewish and Arabic Sources of Leone Ebreo’s Doctrines,” in Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, p. 390.

33. See his “Medieval Jewish Philosophy in the Sixteenth Century,” in Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, pp. 106–145, especially pp. 130–132.

34. Hebrew Ethical and Homiletical Literature [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1975), pp. 191–193. The same ideas were repeated again in his “An Inquiry into the Jewish Homiletic Literature of the Renaissance Period in Italy” [Hebrew], Proceedings of the Sixth World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem, 1977), division 3, pp. 105–110.

35. See e.g. Israel Bettan, Studies in Jewish Preaching (Cincinnati, 1939), p. 192, where he describes Moscato as “a child of the Renaissance.” More recently this view was also embraced by R. Bonfil. I take this view as well. On the general influence of Renaissance culture on the Jews see David B. Ruderman, “The Italian Renaissance and Jewish Thought,” in Renaissance Humanism: Foundations and Forms, 3 vols., ed. A. Rabil, Jr. (Philadelphia, 1988), vol. 1, pp. 382–433. As against these emphases regarding the influence of the Renaissance see the view of Dan, Hebrew Ethical and Homiletical Literature, p. 183, where he expresses the opinion that the Renaissance influence on Jewish literature was peripheral.

36. Fols. 21c–22b.

37. In addition to Dan’s opinions related to this sermon, note 34 above, see also Isaac E. Barzilay, Between Reason and Faith, Anti-Rationalism in Italian Jewish Thought 1250–1650 (The Hague, Paris, 1967), p. 173; Alexander Altmann, “Ars Rhetorica as Reflected in Some Jewish Figures of the Italian Renaissance,” Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, pp. 19–20. Although all of these scholars are aware of Moscato’s quotation from Pico, none of them undertake a comparison of Moscato’s sermon with Pico’s Commento.

38. Bereshit Rabbah, vol. 3, p. 4, ed. J. Theodor and H. Albeck (Jerusalem, 1965), p. 19. For a detailed analysis of the meaning of this Midrashic text as hinting at emanation and its reverberation in kabbalah see Alexander Altmann, “A Note on the Rabbinic Doctrine of Creation,” Journal of Jewish Studies, 6/7 (1955/1956): 195–206.

39. On this issue in medieval Jewish texts see Moshe Idel, “The Journey to Paradise” [Hebrew], Jerusalem Studies in Folklore 2 (1982): 7–16.

40. Dan, Hebrew Ethical and Homiletical Literature, p. 193. Dan’s assumption that Moscato’s reference to a Christological concept should automatically be construed as negative is unfounded. See e.g. the moderate attitude toward Christology of Moscato’s contemporary, Solomon Modena, in David B. Ruderman, “A Jewish Apologetic Treatise from Sixteenth-Century Bologna,” Hebrew Union College Annual 50 (1979): 265.

41. Alul. The very use of this term shows that it is a created, non-divine being to which Moscato refers. It should be mentioned that the question of the origin of Pico’s view of the “first creature” is rather complex. The concept that the first created entity is an intelligible creature that includes in itself all the forms of existence is reminiscent of Rabbi Isaac ibn Latif’s view of nivra rishon. As I have proposed elsewhere, Pico was acquainted with the major work of ibn Latif, Sefer Sha‘ar ha-Shamayim, where the above phrase recurs. See Moshe Idel, “The Throne and the Seven-Branched Candlestick: Pico della Mirandola’s Hebrew Source,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 40 (1977): 290–292. Moscato does use the term alul rishon, which though conceptually identical to nivra rishon, differs from it terminologically. In his later work, Kol Yehudah, however, he quotes ibn Latif extensively, including texts wherein the term nivra rishon is mentioned; see e.g. book 4, 25, p. 49a, which does not refer to the topic of our sermon. On the history of ibn Latif’s concept see Sarah O. Heller Willensky, “The ‘First Created Being’ in Early Kabbalah and Its Philosophical Sources” [Hebrew], in Studies in Jewish Thought, ed. S. O. Heller Willensky and Moshe Idel (Jerusalem, 1989), pp. 261–275. See also below note 46; Pico’s prima creatura is a perfect translation of ibn Latif’s term.

The fact that Moscato uses the term alul and not nivra suggests that initially he was better acquainted with Pico’s views than with ibn Latif, and only later did the writings of the thirteenth-century kabbalist come to his attention.

42. Dan, in his analysis of this text, used a late and unreliable edition, Lemberg, 1859, where there is what I assume to be a printing error, and in lieu of “Yoan,” “Yoel” is printed, a shift easily understandable to readers of Hebrew. On the basis of this change Dan (Hebrew Ethical and Homiletical Literature, p. 192) decided that Moscato wanted to Judaise Pico. Though this may have been the intention of the unknown late Polish proofreader, it was not Moscato’s. As we shall see immediately below, at least in this context Moscato refrains from Judaizing pagan authors.

43. This spelling is found also in Moscato’s Kol Yehudah, book 4, 3, p. 11b. Here we find another reference to Pico’s Commento, which is worthy of a detailed discussion in its own right.

44. Fols. 21c–21d.

45. Commento sopra una canzona d’amore di Girolamo Benivieni, chap. 4, in Opera Omnia (Basle, 1557), vol. 1, p. 899.

46. See ibid.:

Questa prima mente creata, da Platone e così dalli antichi philosophi Mercurio Trimegista e Zoroastre è chiamato hora figluolo de Dio, hora mente, hora Sapientia, hora ragione Divina.…Et habbi ciascuno diligente advertentia di non credere che questo sia quello che de nostri Theologie è ditto figluolo di Dio, imperochè noi intendiamo per il figluolo di Dio una medesima essentia col padre, à lui in ogni cosa equale, creatore finalmente e non creatura, me debbesi comparare quello che Platonici chiamano figluolo di Dio, al primo e più nobile angelo da Dio prodotto.

There are some significant variae lectionum between this edition and that printed by Eugenio Garin, De Hominis Dignitate,…(Florence, 1942), pp. 466–467. In many respects Garin’s version seems to be closer to Moscato’s; the most important of them is that in lieu of the phrase “prima mente creata” Garin’s version has “prima creatura.” See above note 41.

On this text see Chaim Wirszubski, Pico della Mirandola’s Encounter with Jewish Mysticism (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1989), pp. 198–200. Wirszubski adduced a very interesting parallel to the passage in the Commento from one of Pico’s Theses where the filius Dei of Mercurio, namely Hermes Trismegistus, is mentioned together with Zoroaster’s paterna mens, Parmenides’ sphera intelligibilis, Pythagoras’ sapientia and, according to Wirszubski’s very plausible reconstruction, with the Kabbalistic Metatron, without even mentioning the Christian theological view. On Kabbalistic speculations concerning the “divine son” see Yehuda Liebes, “Christian Influences in the Zohar,” Immanuel 17 (1983/1984): 51–59.

47. See Wirszubski, pp. 198–199.

48. The Philosophy of Spinoza: Unfolding the Latent Processes of His Reasoning (New York, 1969), vol. 1, p. 243.

49. B. Sanhedrin, 38b.

50. Ms. Vatican 192, fol. 76a; Ms. Munich 58, fol. 153a. On this treatise see Colette Sirat, “Les differentes versions du Liwyat Hen de Levi ben Abraham,” Revue des études juives 122 (1963): 167–177. On Abraham Abulafia’s understanding of Son, Metatron and separate intellect and that of one of his followers, the anonymous author of Sefer ha-Ẓeruf, see Wirszubski, Pico della Mirandola’s Encounter, pp. 213–234. See the early Hebrew version of this discussion in Chaim Wirszubski, Three Studies in Christian Kabbala (Jerusalem, 1975), pp. 53–55.

51. Me’or Einayim, Imrei Binah, chap. 3, p. 101.

52. On this issue see Joanna Weinberg, “The Quest for Philo in Sixteenth-Century Jewish Historiography,” Jewish History, Essays in Honor of Chimen Abramsky (London, 1988), pp. 171–172.

53. See Poimandres 1, 12–13ff. I have already pointed out that Hermetic influences on Jewish literature are found in a long series of texts in the Middle Ages, most of them, or perhaps all of them, through the intermediary of Arabic sources. See Moshe Idel, “Hermeticism and Judaism” in Hermeticism and the Renaissance, Intellectual History and the Occult in Early Modern Europe, ed. Ingrid Merkel and Allen G. Debus (London, Toronto, 1988), pp. 59–76. Jewish authors living in the Renaissance, however, like Isaac Abravanel, Moscato, de’ Rossi, and Abraham Yagel, were influenced by Hermetic literature translated by Marsilio Ficino. Characteristically enough, de’ Rossi intended to translate some portions of the Hermetic corpus into Hebrew. I assume that the Jewish interest in Hermetic writings has something to do not only with the Renaissance passion regarding this literature but also with the feeling corroborated by some modern studies that there is a certain similarity between Jewish and Hermetic ideas. See the pertinent bibliography in my aforementioned article.

54. For the history of this concept see Harry A. Wolfson, “Extradeical and Intradeical Interpretations of Platonic Ideas,” in Religious Philosophy (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), pp. 27–68; and see also Idel, “The Magical and Platonic Interpretations,” pp. 223–227.

55. On Torah as the intellectual universe see Moshe Idel, Language, Torah and Hermeneutics in Abraham Abulafia (Albany, 1989), pp. 29–38.

56. Ernst Cassirer, “Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance,” Journal of the History of Ideas 4 (1943): 49–56; Couliano, Eros and Magic, p. 12.

57. I propose to see in Pico and Ficino the Renaissance founders of a multilinear conception of religious and philosophical truth, an issue to be elaborated in my forthcoming treatment of the topic. For the time being see the bibliography mentioned by Wirszubski, Pico della Mirandola’s Encounter, p. 198, n. 41.

58. The great majority of Renaissance Jews adhered to the medieval, unilinear conception of prisca theologia. See Moshe Idel, “Kabbalah and Philosophy in Isaac and Yehudah Abravanel” [Hebrew], in The Philosophy of Leone Ebreo, ed. M. Dorman and Z. Levi (Tel Aviv, 1985), pp. 73–112, especially pp. 84–86.

59. This conclusion holds also in the case of Abraham Yagel, Moscato’s younger contemporary; see David B. Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science: The Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth-Century Jewish Physician (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1988), pp. 139–160; idem, A Valley of Vision: The Heavenly Journey of Abraham ben Hananiah Yagel (Philadelphia, 1990), pp. 23–68.

60. See his Kol Yehudah, book 2, fol. 76a. I shall discuss this passage in an appendix to my aforementioned study of the concept of prisca theologia.

61. See note 50 above.

62. See Wirszubski, Pico della Mirandola’s Encounter, p. 199; idem, Three Studies in Christian Kabbala, p. 56.

63. Sermon 5. Cf. the translation of Bettan, Studies in Jewish Preaching, pp. 201–202. This statement should be compared with de’ Rossi’s plan to write an introduction to a proposed translation of two of the most important portions of the Hermetic corpus, there distinguishing between the holy and the profane. If the term profane stands for the “magical” part of Hermeticism, as Weinberg proposes, then de’ Rossi concurs with Moscato’s reticence in elaborating upon magic and theurgy. See Weinberg, “The Quest for Philo,” n. 56. This awareness of the need for selectivity insofar as the pagan material is concerned shows that we are dealing with a moderate reception of Renaissance culture in both cases. On moderate adoption of the Renaissance among Jews see Moses A. Shulvass, “The Knowledge of Antiquity among the Italian Jews of the Renaissance,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 18 (1948/49): 299.

64. Sermon 3, fol. 9c.

65. Kol Yehudah, book 4, 25, pp. 50a, 53ab.

66. Dar stems from the root dur, which is related to both the idea of dwelling and to the idea of circularity. Since God is defined as a circle, the last Sefirah was described, using the terminology of Joseph Gikatilla, the author of Sha‘arei Ẓedek, as the circle where the sefirah of tiferet, the Lord, dwells in residence. See also below note 78.

67. Nefuẓot Yehudah, p. 80a.

68. Ibid., p. 81a; see also below note 78.

69. See Joseph Gikatilla’s Commentary on Ezekiel’s Chapter on the Chariot, Ms. Cambridge, Dd, 3, 1, fol. 22a.

70. Reshit Ḥokhmah, Sha‘ar ha-Kedushah, chap. 2 (Jerusalem, 1984), vol. 2, p. 30, where the text of Gikatilla is quoted. This book was printed in Venice in 1579.

71. Shalem. In the Latin definitions, when the sphera is qualified, the terms infinita or intelligibile are used, but not the term perfect; however there are instances where the term sphera is not qualified.

72. In Hebrew iggul, literally circle, though in most of the Christian sources the parallel term is sphera, a sphere. The occurrence of the circle in lieu of the sphere may be related to the Neoplatonic definition of the circle as the figure which has all the points of the circumference at an equal distance from the center. This definition is explicitly transferred by Moscato to God; see Nefuẓot Yehudah, p. 79d.

73. Ibid., p. 80a.

74. See C. Baumkehr, ed., Das pseudo-hermetische Buch der XXIV Philosophorum (Muenster, 1937), p. 208; D. Mahnke, Unendliche Sphaere und Allmittelpunkt (Halle, 1937); Chaim Wirszubski, “Francesco Giorgio’s Commentary on Giovanni Pico’s Kabbalistic Theses,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 27 (1974): 154; Georges Poulet, Les Metamorphoses du cercle (Flammarion, 1981), pp. 25–69; Frances A. Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (London, 1964), p. 247 and n. 2; Alexander Koyre, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (New York, 1958), pp. 18, 279 n. 19, and Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance (New York, 1967), pp. 227–228; Karsten Harries, “The Infinite Sphere: Comments on the History of a Metaphor,” Journal of the History of Philosophy 13 (1975): 5–15.

75. The designation of God as place is a topos in ancient Jewish texts; see Ephraim E. Urbach, The Sages, Their Concepts and Beliefs, trans. I. Abrahams (Jerusalem, 1979), vol. 1, pp. 66–89; Brian P. Copenhaven, “Jewish Theologies of Space in the Scientific Revolution: Henry More, Joseph Raphson, Isaac Newton and Their Predecessors,” Annals of Science 37 (1980): 489–548; Moshe Idel, “Universalization and Integration: Two Conceptions of Mystical Union in Jewish Mysticism,” in Mystical Union and Monotheistic Faith: An Ecumenical Dialogue, ed. M. Idel and B. McGinn (New York, London, 1989), pp. 33–50.

76. Nefuẓot Yehudah, p. 79b. See also p. 79c where God is referred to as the absolute space which is, at the same time, the center and the circle.

77. On the images of the circle in Renaissance writings see Pines, “Medieval Doctrines,” pp. 338–390; Barzilay, Between Faith and Reason, p. 175; and Moshe Idel, “The Sources of the Circle Images in Dialoghi d’Amore” [Hebrew], Iyyun 28 (1978): 156–166.

78. The Hebrew form kevod tiferet is unusual; Perhaps it stands for two sefirot: malkhut as kavod or glory, and tiferet, as a designation of the homonymous sefirah. Such an explanation may reflect the relationship between the two sefirot as circle and center respectively, as we have already seen above, note 66.

79. Nefuẓot Yehudah, p. 81b.

80. Namely halakhah. The feeling that there is an overemphasis on the aggadah at the expense of halakhah is interesting because it confirms the preoccupation with making sense out of the ancient legends on the part of Moscato’s other contemporaries, de’ Rossi and David del Bene. It should be mentioned that many of the sixteenth-century Italian kabbalists and intellectuals were interested in kabbalah more as a speculative, spiritual enterprise and as a way to understand the aggadic corpus, than as an interpretation of the halakhic dromenon. This distancing between the two major topics, which were presented as a unity in the Zohar, and the preference for the aggadic part of Judaism, betrays an influence of the Renaissance. On the general context of this disentanglement of theurgy, closely related to halakhah, from theosophy, see Moshe Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives (New Haven, London, 1988), pp. 262–264.

On halakhah and aggadah as codes of Jewish culture and the need to integrate them, see Ẓipora Kagan, Halacha and Aggada as a Code of Literature [Hebrew], (Jerusalem, 1988).

81. Cf. Bettan, Studies in Jewish Preaching, p. 226.

82. Cf. Couliano, Eros and Magic, p. 12.

83. “Some Reflections,” p. 34 (where he also mentions Moscato), and p. 38.

84. “Major Currents in Italian Kabbalah,” pp. 261–262. See also Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science, pp. 159–160. This conclusion corroborates Isaiah Sonne’s general thesis as to the paramount importance of a strong cultural environment for the development of Jewish Italian culture; see his ha-Yahadut ha-Italkit, Demutah u-Mekomah be-Toledot Am Israel (Jerusalem, 1961); Isadore Twersky, “The Contribution of Italian Sages to Rabbinic Literature,” Italia Judaica (Rome, 1983), pp. 398–399.

85. The question of the dissemination of kabbalah in Italy since the late sixteenth century and especially at the beginning of the seventeenth century is still unresolved. See Robert Bonfil, “Halakhah, Kabbalah and Society, Some Insights into Rabbi Menahem Azariah da Fano’s Inner World,” in Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century, ed. Isadore Twersky and Bernard Septimus (Cambridge, Mass., 1987), pp. 39–61, especially p. 61, and his “Change in the Cultural Patterns of a Jewish Society in Crisis: Italian Jewry at the Close of the Sixteenth Century,” Jewish History 3 (1988): 18–19, where he speaks of the isolation of the Kabbalists—in my opinion mainly the Lurianic Kabbalists—from the general public. However, the deep impact of the Cordoverian kabbalah in Italy was not overpowered by the later arrival of the Lurianic, especially Sarugian, kabbalistic systems; see Isaiah Tishby, Studies in Kabbalah and Its Branches [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1982), pp. 177–203; see also note 31 above.

86. See Moshe Idel, “Differing Conceptions of Kabbalah in the Early 17th Century,” Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century, pp. 137–200, especially pp. 168, 173–174.