3. The Zionist Revolution

Whatever the weight of tradition, the fact remains that Israel, more than almost any other state, is the result of an idea imposed on reality. Most nations represent an evolution of geographic and ethnic circumstances. But—like the United States in certain respects—Israel would not have come into existence without the strength of beliefs that moved their adherents to create new political realities.

Just as the ideas of the American Revolution must be understood in the context of the republicanism and rationalism of the late eighteenthcentury Enlightenment, so political Zionism—the drive to normalize the status of the Jewish people by achieving political sovereignty—reflected late nineteenth-century European ideologies of nationalism, socialism, and liberal democracy. Of course the aim of returning to Zion had always been central to Jewish thought and ritual, affirmed in daily prayer and by the continuing presence in Palestine of a small Jewish community. But it was the ideological ferment of nineteenth-century Europe that transformed what had been a vague religious aspiration into a largely secularized political movement with an active program for Jewish settlement and sovereignty in Palestine. The Zionist revolution was to affirm a secular self-identity as a nation along with, or even in place of, traditional religious and communal self-identity.

The center of the Jewish world at the time was tsarist Russia, which then included the Baltic states and Poland. In the early 1880s some four million Jews—well over half of world Jewry—lived under tsarist rule.[1] From the time of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, this population was subjected to a wave of officially inspired persecution that was part of the regime’s response to the impact of revolutionary and nationalistic ideas within Russia.

The historic Jewish response to such repression was flight to more hospitable locales, and there was little difference this time. Between 1881 and 1914 about two and a half million Jews left Russia, most of them for the United States and other Western countries. But a small number, roughly 3 percent, chose to return to the ancient homeland instead.

Why did this tiny proportion choose such a novel response to such an age-old problem? Antisemitism was a major thread of Jewish history, but it had never sparked a significant movement for a return to Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel, as geographic Palestine was known in Hebrew). Zion had always appeared more bleak and inhospitable than the alternatives, and this was no less true in the declining years of Turkish rule there. Furthermore, the previous century had been the century of Emancipation: ghetto walls were torn down across Europe as secularization removed ancient barriers to Jewish participation in public life. Why, in such an improving climate, should a part of the Jewish community suddenly reject patterns of minority existence that had persisted for two millennia?

One reason was that Emancipation posed new dilemmas to which traditional solutions were irrelevant.[2] In a society sharply divided along religious lines, Jews suffered many disabilities, but the very sharpness of the division left them with a clear sense of their own identity. When nationality replaced religion as the main point of reference, Jews were in a more problematic position. The relationship of Judaism to Christianity was clear, but the identity of Jews as Frenchmen, Germans, or Russians was ambiguous. Presumably the path to integration was open, but could it ever be totally successful? And would such success mean the complete loss of any meaningful identity as Jews? The problem was particularly acute in Eastern Europe; while there was some room in the Western European conception for a citizenship defined simply by membership in a common state, the exclusive identification of a state with a single nationality was much stronger in Eastern Europe.

One possible response was, nevertheless, total assimilation, and a large part of the Jewish community chose this path. Another answer was to embrace an ideology that denied ethnicity itself. Thus the appeal, to large numbers of Jews, of revolutionary socialist doctrines that put class interests above national and ethnic divisions or of Western liberal democratic ideals that put all individuals on a setting of civic equality.

Others responded, however, by embracing the idea of nationality and extending it to include the Jewish people. In an age when Greeks, Italians, Serbs, Romanians, and Albanians were rediscovering their own national identities, it should be no surprise that Jews reacted with a reaffirmation of their identity. By virtue of their 3,500-year history as a people, with distinctive cultural patterns, languages, religion, and a strong self-identity enforced by external hostility—by any test, in fact, but that of geographic concentration—most Jews felt their claim to recognition as a nation was as valid as that of other emerging nationalities of the period.

Jews thus sought answers to new external realities in new ideologies, which were also of external origin. What were these ideologies, and why were Jews so susceptible to their influence at this point in their history?

| • | • | • |

The Impact of Ideology: Nationalism, Socialism, Liberalism

Nationalism is the main thrust of political Zionism; however Zionists differed in other respects, the common core was application of the principle of the nation-state to the Jewish people. Where it clashed with other ideologies “the fact is undeniable that both emotionally and practically nationalism prevailed.” [3] Nationalism was of course one of the great forces of the time, and by the end of the nineteenth century it was generally accepted in the Western world that political sovereignty should correspond to ethnic (“national”) divisions; that is, that the nation-state, rather than the dynastic state or the multinational empire, should be the basic unit of world politics. This principle was to achieve its climactic vindication, at least in theory, in the results of World War I. That Jews should also choose the nation-state as the best vehicle of national survival should not be surprising, therefore. David Biale remarks that Jews “have always demonstrated a shrewd understanding of the political forms of each age,” and that adopting modern nationalism was therefore not essentially different from the “tradition of political imitation and accommodation” that was a legacy of Jewish history.[4]

In choosing nationalism as a framework, Jews were moving from a more particularistic, if not unique, place in the world to a more universal and common model. With their own nation-state, Jews would join a world community of kindred peoples, each exercising its right of self-determination in its own sovereign space. Even in this liberal and moderate version of nationalism, of course, there is some ambiguity, since one is universalizing a principle of particularism: the right of each people to its particular identity, its particular character, and its particular political choices. If this is taken to imply the goal of homogeneity within a nation, then the position of minorities (such as the Jews) does become problematic. But as long as each nation respects the reciprocal claims of other nations to their own self-determination, then in theory the nation-state could be universalized as the basis of a stable world order. We tend to forget that in the midnineteenth century—the period of the unification of Italy and Germany—nationalism was a liberal principle allied to the struggle for democracy and self-determination for all peoples.

By the time Zionism emerged, however, nationalism was slipping from this liberal and universalizable form to more particularistic expressions. Far from accommodating the rights of other peoples on an equal basis, this more assertive nationalism focused on the presumed virtues or rights of a particular people. Taken to the extreme (with Italy and Germany again as illustrations), in its twentieth-century manifestations it preached not only racial or ethnic homogeneity but also denial of self-determination to others.

Historically, Zionism was an emulation of the first nationalism and a defense against the excesses of the second. In its earlier guise, liberal nationalism in league with democratization had indeed improved the situation of Jews throughout Europe. But in its later manifestation as “exclusive” nationalism, the position of Jews in new nation-states became increasingly precarious. The drive for a Jewish state therefore had behind it both a powerful positive pull, in the desire for Jewish self-determination and selfexpression, and a strong negative push, in the simple need for escape from this second strain of nationalism.

Exclusive nationalism gave rise to a new and more vicious ethnic antisemitism, which for many nullified assimilation as a solution to the problematic position of Jews. When religion was the criterion, Jews at least had the option of conversion. But one could not convert to a new ancestry; consequently even the most thoroughly assimilated Jews were not totally accepted in the new hypernationalist European societies. This was driven home by events like the Dreyfus trial—in liberal France yet—where a Jewish army officer, totally French in culture and loyalty, was falsely convicted of treason in a conspiracy involving the high military command. The final proof, some decades later, was the fate of German Jews, perhaps the most assimilated community in Europe. Many early Zionists, including Theodor Herzl himself, began as assimilationists but became convinced by events that integration would not end the persecution of Jews as a minority. Thus the achievement of political sovereignty was seen not only as an inherent right but also as a necessary response to the position of Jews as an exposed minority in Europe and elsewhere.

Eventually some within the Zionist movement also moved from the first form of nationalism to a more assertive and particularistic version. Like their counterparts in Europe, the “nationalist right” among Zionists asserted the exclusive right of the Jewish people to all of Eretz Yisrael, condemned any “compromise” of this right, and stressed the values of order, discipline, and authority above individual rights and democracy.[5] Organized as the Revisionist movement in the 1920s, under the leadership of Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, this viewpoint was taken to extremes by others (some even copied elements of European fascism at its peak in the 1930s). Revisionists sought to realize their goals through a political-military strategy, rather than by the slow buildup of a Jewish presence through grassroots settlement activity—Zionism from the top rather than from the bottom.

If nationalism was an ideology with both universalist and particularist potential, the role of socialism should be less ambiguous. Based on a materialist and “objective” view of history, socialism presumes to transcend national differences and provide a class-based analysis of universal applicability. It must be noted at the outset, however, that socialism appealed to Jews in part because of clear points of convergence with Jewish traditions. Among the compatible elements were emphasis on collective identity and interest, concern with social justice, a conception of ultimate deliverance (messianism), perception of a basically hostile environment, and justification of revolt against established authority. The case should not be overstated; clearly other elements in socialism were foreign to Jewish thinking: the primacy of economic factors, historical determinism, the cosmopolitan focus on class rather than nation, the denigration of religion, the argument for centralizing power, and belief in impersonal forces (rather than personal connections). But still many Jews saw secular socialism as “old wine in new bottles,” and some non-Zionist Jewish socialists saw the revival of traditional Jewish autonomy (the kahal) as a logical means of achieving their ends.[6]

The Haskala had also prepared the ground for socialism by exposing many Eastern European Jews to major currents of Western thought and secularizing their outlook. Changes in Russia also had a major impact: education had advanced sufficiently to create an intellectual class (of both Russians and Jews), but opportunities for integration into the system were blocked. This creation of an alienated group of “rootless intellectuals” is the classic recipe for producing professional revolutionaries, and nineteen-century Russia is a classic example. And since Jewish intellectuals were even more marginal than their Russian counterparts, they were also heavily overrepresented in this “school of dissent.” [7]

The structure of Jewish life also enhanced the appeal of Marxist socialism, in particular. By the late nineteenth century, the Jewish population of Eastern Europe had to a great extent been urbanized, pauperized, and proletarianized (with perhaps 40 percent of Jewish workers, by one estimate, employed as cheap industrial labor). This came on top of a strong resentment of the rich by the poor in the traditional kahal, which had earlier been an ingredient in the appearance of Hasidism as a movement. The convergence of all these circumstances created a state of ferment “that stamped the tradition of radicalism irrefragably upon the souls of untold thousands of Russian-Jewish young people.” [8]

The first wave of Jewish socialists were indeed universalistic in outlook; they rejected specifically Jewish concerns and outlooks in the belief that all problems would be solved by eliminating class-based oppression. As one orator proclaimed in 1892: “We Jews repudiate all our national holidays and fantasies which are useless for human society. We link ourselves up with armies of Socialism and adopt their holidays.” [9] The Jewish participants in the Vai Narod (Movement to the People) tried to take the case for socialism to the Russian peasantry, with even less success than their Russian comrades. Jewish socialists turned to their fellow Jews, in the end, largely for tactical rather than ideological reasons: it was only among Jews that they had any success. But their program still had no Jewish content; when it was decided to establish Jewish agricultural colonies, there was no inclination to favor Palestine over other locations, and colonists were sent to South Dakota, Louisiana, and Oregon.[10] With the establishment of the Bund a brand of Jewish socialism was devised, but along non-Zionist lines. The Bund sought to achieve Jewish autonomy in existing places of residence, largely through the revival and democratization of the classic kahal.

The next step beyond the program of the Bund, combining socialism with full-blown Jewish nationalism, had actually been taken earlier by one of the founding figures of socialism. Moses Hess, a German Jew and collaborator with Karl Marx, in 1862 published Rome and Jerusalem, calling for the establishment of a Jewish socialist commonwealth in Palestine. The idea attracted no support at the time but was picked up and elaborated fifteen years later by Aaron Liberman, a Russian Jew, who adapted it to Russian circumstances. Then in 1898, only two years after Herzl published Der Judenstaat, Nachman Syrkin published an influential pamphlet that approached Zionism systematically from a socialist context. The final synthesis of Marxism and Zionism was carried out by Ber Borochov, whose first important writing appeared in 1905.[11]

Even then, Zionistically inclined socialists did not rush to embrace Jewish nationalism wholeheartedly. The strongest group in early Labor Zionism, the Zionist Socialists, were actually supporters of “territorialism,” the idea that a Jewish state could and should be built in any suitable location. Fixation on the historical attachment to Palestine was, in their eyes, romantic nationalism. The important justification for building a new state was to correct what was considered to be the abnormal, distorted structure of Jewish society, and this could be done in any territory in which Jews were free to build their own “normal” society.

Whether attached to Palestine or not, Labor Zionists all shared this preoccupation with the total restructuring of Jewish life. Labor Zionism targeted the “unnatural” economic role that had been forced on Jews in the Diaspora. It urged Jews to move out of such accustomed trades as commerce, finance, and the professions, and to create a Jewish proletariat based on manual labor, a return to the soil, and self-reliance in all spheres of production. In contrast to most other nationalisms, Labor Zionism strongly stressed self-transformation as well as the achievement of external political aims. In the words of the Zionist slogan, Jewish pioneers came to Eretz Yisrael “in order to build and to be built in it.” The establishment of the kibbutz, or rural communal settlement, was a perfect expression of these ideals.[12]

Labor Zionism represented a clear break with the Jewish past and a clear call for a program that would make the Jewish people “a nation like other nations.” And while its success may have rested in part on its compatibility with some Jewish traditions, it also contributed important novel elements to the Zionist enterprise. The socialist method of building “from the bottom up,” by the slow and patient construction of settlements designed to restructure Jewish life, became the dominant model in the Zionist self-image (even though most settlers came to cities, hardly a novel departure). Socialist ideology provided the rationale—and the manpower—for the mobilization of human resources under prevailing conditions, without waiting for deliverance by the powers-that-be.[13] But perhaps most importantly, socialism (like nationalism to a lesser degree) put Jewish politics into a conceptual framework and vocabulary of general relevance. It helped to provide the link to secular, Western ideas and influences by which its own progress could be guided and judged.

The direct influence of Western liberalism, as opposed to Eastern European socialism, was more attenuated but still a factor. Even in tsarist Russia, Lockean ideals of limited government and individual rights were not unknown (if socialism could penetrate the walls of absolutism, so could other ideas). The concepts of democracy, if not its practice, had by this time acquired general currency. The early Zionist leaders from Central Europe lived in an intellectual milieu where liberalism was prevalent. A number of “Western” Jews (including, by virtue of his long residence in England, Chaim Weizmann) occupied important posts over the years in the Zionist movement. The British and U.S. branches of that movement were important and vocal in supporting their own political ideals. Finally, the British government presided for thirty years over the development of the Jewish national home, as the Mandatory power.[14]

While some Western conceptions of unfettered individualism and uncompromising secularism ran against the grain of nationalist, socialist, or religious influences, democratic ideas were also reinforced—it should be recalled—by both traditions and circumstances. Even when democracy was not practiced as a matter of intellectual conviction, some sharing of power had often been necessary because of the voluntary basis of Jewish selfgovernance.

Western liberalism has been especially visible in two areas. First is the legal and judicial system with its strong borrowings from British and other Western sources.[15] Second is the economic sphere, where the opponents of socialism (organized historically as the General Zionists) adopted liberal economic doctrines as a platform. The General Zionists originally were simply those Zionists who were not socialist, religious, or revisionist; they occupied a centrist position by virtue of their opposition to both left and right. When they were organized as a party, in the 1930s, a large influx of immigrants from Central Europe reinforced the party’s liberal image. General Zionists became the movement most clearly identified with Western liberalism, especially in economic policy but also to some extent in political matters.

The fourth strand of the Zionist movement, after Labor, Revisionist, and General Zionists, was religious Zionism. Religious Zionists accepted the aim of rebuilding a Jewish state in Palestine but sought to do so in strict accordance with traditional Jewish law. Clearly this was the least revolutionary and least universalistic version of Zionism; it remained a small minority within the Zionist movement and, for a considerable period, within the Jewish Orthodox community as well. Perhaps nothing else indicates as well how Zionism was seen as a revolutionary threat to traditional values and hierarchies in the Jewish world. In the eyes of rabbinical authorities, the Zionist movement was regarded as a secular nationalist movement that threatened traditional Judaism. They correctly associated it with the secularizing Haskala movement, which had posed the same threat, and which they had also opposed. The vast majority of them “knew danger when they saw it” and took a hard anti-Zionist line.[16] This left only a small number in the religious Zionist camp—the forerunners of today’s National Religious Party—who were able, in the early days of Zionism, to reconcile its basically secular and revolutionary ideological thrust with religious Orthodoxy.

| • | • | • |

Zionism: Change and Continuity

The conflict between change and continuity was basic to Zionism, which might be described as a set of ideologies laid over a substratum of habits and traditions. These ideologies conflicted, in varying degrees, with the traditions. But whether subscribing to nationalist, socialist, or liberal ideologies—or, like Labor Zionists, to some combination of these—Jews of Central and Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century were indeed, in large numbers, seeking a break with the past. They filled the ranks of non-Jewish revolutionary movements in disproportionate numbers, and those who rallied to the Zionist call also saw themselves as being in “revolt” against past patterns of Jewish history. Zionists sought to escape from the particularism of the Jewish past and to rejoin history by recasting Jewish life into new universal molds provided by modern ideology. In David Vital’s apt phrase, they wished “to extricate the Jews from a rhythm of national history such that the quality of their life at all levels was determined in the first instance by the treatment meted out to them by others.…to cease to be object and become subject.” They felt that “the course of Jewish history must be reversed”; the significance of Zionism was nothing less than “the re-entry of the Jewish people into the world political arena.” [17]

Traditional Jewish life was seen (with some exaggeration) as politically impotent, as a manifestation of weakness inseparable from the condition of exile. In some cases, the dissociation with the Jewish past reached extreme proportions. Herzl himself largely accepted the antisemitic portrait of Jews as avaricious, unprincipled, parasitic, and vulgar, while arguing that it was Christian oppression that had so deformed the Jewish character.[18] In one of the well-known stories of Yosef Haim Brenner, a leading literary figure of early Labor Zionism, the protagonist attacks the particularities of Jewish life in harsh language: “With a burning and passionate pleasure I would blot out from the prayer book of the Jews of our day ‘Thou has chosen us’ in every shape and form.” [19] The basic logic of this orientation is best demonstrated, perhaps, by those who took it to the very limit. The Canaanite movement, active in the yishuv during the 1940s, rejected any connection with Jews or Judaism and sought to assimilate with the indigenous Arabs as a new Hebrew nation. On the other hand, one of the most common themes of Israeli literature has been an attack on Zionism for having detached Jews from their roots; a well-known example is Yudkeh’s long and anguished sermon against Zionism’s failings in the famous short story by Haim Hazaz.[20]

Yet despite the endeavors of its disciples and the allegations of its enemies, Zionism was never wholly at odds with tradition. For one thing, Zionism was itself a reaction against the claim that the spread of modern Western ideologies would solve the Jewish problem. Zionism could even be seen as a repudiation of the civic liberal ideal; it “appeared as a criticism of the Jewish problem based on civic emancipation alone; and it was an effort to reestablish continuity with those traditional conceptions of the nature and goal of Jewish history that had been discarded by Jewish disciples of the Enlightenment.” [21] One traditional conception of Jewish history with which Zionism was closely associated was messianism. Zionism was in a sense a transformed messianism, drawing its strength from age-old aspirations deep in the Jewish spirit; even a socialist such as Nachman Syrkin could proclaim that “the messianic hope, which was always the greatest dream of exiled Jewry, will be transformed by political action.…Israel will once again become the chosen people of the peoples.” [22]

Furthermore, while Herzl and some of the more Westernized Zionists may have had little feel or regard for Jewish tradition, their followers in Eastern Europe were closer to it. They did not reject the past outright but combed it for what might be useful in building the future; “continuity was crucial: the Jewish society at which they aimed…had to contain within it the major elements of the Jewish heritage.” [23] The past was invoked and reinterpreted in order to restore Jewish dignity (as in the cults of the Maccabees, Masada, or Bar-Kochba); precedents for “new” Zionist departures were sought in the historical sources. The relationship to history might be selective, and there was a marked tendency to revere antiquity while reviling Diaspora life, but on the whole few Zionists rejected all connection with Jewish history. As the leading study of the subject concludes, “between the two poles of continuity and rejection, Zionism established itself on a broad common base best described as dialectical continuity with the past.” [24]

It was unrealistic to believe that a Jewish state could be established without reference to four millennia of Jewish history. Tradition supplied Zion itself as the focus of Zionism; even for the most secular of Jews, only Palestine had the power to mobilize the imagination of would-be settlers. Holidays and national symbols were inevitably drawn from the past, even if attempts were made to alter their content and significance. The very legitimacy of the entire enterprise rested, in the end, on Jewish history and religion, a factor that grew in importance as conflict with the Arab population developed. And if this was the case for the secular Eastern European Zionists who settled in Palestine during the early days, it was that much more the case for religious and non-European Jews who were already settled there, or who came later; among these populations, the primordial tie to Judaism was strong and the impact of revolutionary ideologies, including the model of the civic state, was very faint.

The “dialectical continuity” with the past was often obscured by the rhetoric of revolution and universalism. But even Herzl himself was capable of relapsing “into the set and mode of thought in which particularity and specificity are celebrated as a matter of course” (with the dialectical process also reflected in Herzl’s depiction of his utopian state of the future as an “old-new” land).[25] Cultural Zionists, following Ahad Ha’am, also sought to revolutionize Jewish life, but by drawing explicitly on Jewish sources of spiritual renewal and thus founding “not merely a state of Jews but truly a Jewish state.” [26] Even the most radical Zionist revolutionaries demonstrated links to tradition in subtle ways: in focusing on a redemptive process (albeit a secular one), in showing little interest in political programs not centered on Jewish interests, and in their “mildness” as revolutionaries in the Jewish context (where the emphasis was on building rather than destroying).[27]

The revolutionary content of Zionism was further attenuated in the new settlements of Eretz Yisrael, where ideology struggled not only with the habits and traditions that new immigrants brought with them but also with new realities about which doctrine was ambivalent or even irrelevant. Indeed, the very fact of Jewish settlement in Palestine was more a product of circumstance than of ideological appeal. As Jacob Katz notes, the aim of uprooting a people and replanting them elsewhere “was beyond the strength of the National idea in itself.” [28] It took place only when persecutions and pogroms in Eastern Europe accomplished the uprooting. Even then, very little of the “replanting” was shaped by the national idea; of the two and a half million Jews forced out of Russia between 1880 and 1914, only about 70,000 arrived in Palestine, and many of these did not remain.

This process of self-selection had crucial implications. So long as other destinations were available to the vast majority of uprooted Jews who were not devout Zionists, then the new yishuv would represent a high concentration of the most ideologically committed. Thus the more revolutionary elements of the Jewish intelligentsia were able to establish the conceptual and institutional framework that prevailed for decades and absorbed later mass immigrations of nonideologized Jews who arrived simply because they had nowhere else to go.

| • | • | • |

Early Zionist Institutions

Settlers of the first aliya, or wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine,[29] in the period from 1881 to 1905, were imperfect rebels against Jewish tradition. Untouched as yet by the secularism of the second and third aliyot, these members of Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) build synagogues in their settlements and consulted the rabbinate on matters of Jewish law. In designing their governing institutions, they also drew on political legacies they knew, devising written charters (“covenants”) whose style and terminology were distinctly reminiscent of the traditional kahal. In fact, Vital characterizes these arrangements as “far too smooth a carry-over into the new Hibbat Zion societies of the mental and organizational habits of the properly philanthropic institutions of the community—which often represented everything Hibbat Zion was in rebellion against.” [30]

Apart from any conscious copying of past models, however, the conditions of the yishuv replicated in important respects conditions with which Jews had contended in the past, and not surprisingly they responded along familiar lines. There was no enforceable central authority in Zionism, even after the movement was formally launched (as the World Zionist Organization) in 1897. Early settlers were few in number, in a hostile setting, and relied on each other for mutual support. Being self-selected, they also had a high level of political consciousness and commitment and a strong sense of initiative. Voluntarism and partnership were, of necessity, the only means to establish and maintain a coherent political Jewish entity under these conditions. This meant, of necessity, the toleration of differences, since only by compromise would a common framework among the different settlements work. The framework was even looser, of course, than the kahal: it was built from the bottom up, pulling democratically established settlements together in a loose federation at the national level and laying the first groundwork for the “state within a state.” [31]

The combination of revolt and continuity that this represented is portrayed by Shlomo Avineri:

When a few members of a pioneering group decided to establish what eventually became the first kibbutz, the only way known to them to do this was to have a meeting, vote on the structure proposed, elect a secretary and a committee. Those people were revolutionaries and socialists, rebelling against the ossified rabbinical and kehilla structure of the European shtetl; but the modes of their behavior were deeply grounded in the societal behavior patterns of the shtetl, the force of dialectics.…It was out of these traditions that the Zionist Organization knew how to hold Congresses and elections. . . .[32]

It was this reality, more than Theodor Herzl’s exposure to Western liberalism, that shaped the democracy of the Zionist movement. In fact, had it been up to Herzl, Zionism would have been far less democratic. Herzl was an “old-fashioned conservative” who, a few months before publishing Der Judenstaat, had recorded in his diary that “democracy is political nonsense.” [33] After entering the Zionist scene, he was repelled by the infighting among various factions: “We haven’t a country yet, and already they are tearing it apart.” [34] Herzl’s plan was to settle the problem from above by dealing with monarchs, statesmen, and powerbrokers; only when rejected by the aristocrats did he threaten (and eventually act) to lead a mass movement. Even then, he remained “strongly committed to authoritarian leadership from above…even though circumstances forced him to modify it in practice.” [35]

When Herzl convened the First Zionist Congress in 1897, the model of parliamentary democracy was taken as a matter of course. The Zionist movement lacked even that small measure of coercive authority that Jewish community officials had possessed and had to proceed entirely on the basis of voluntary participation. Given the fact that Herzl dominated the proceedings and wrote the standing orders that governed this and subsequent congresses (based in part on his four years spent observing the French Parliament), he is often credited with laying the basis for the Israeli Knesset. This may be true regarding much of the parliamentary procedure; some of the rules written in 1897 are still operative in the Knesset.[36] But in a larger sense Herzl was not the founder of Israeli democracy; he was only coming to terms with a reality that he could not have changed anyway.

One important element of this reality was the appearance of political parties, which within a few years became the main actors on the Zionist stage. The role of parties was an important element in building a Jewish state from the bottom, Israel being one of the instances where parties came before the state rather than the reverse. It was also important in the development of the electoral system. The First Zionist Congress adopted, as a matter of course, a system of proportional representation in which local Zionist organizations were represented on the basis of one delegate for every hundred members. With the growth of parties within the movement, proportional representation of ideological groupings was added at the Fifth Zionist Congress (in 1901). It should be noted that the principle of proportionality was followed by the Zionist movement well before proportional representation was established in national electoral systems.[37]

The capacity of the Zionist movement to encompass diversity, by virtue of its voluntaristic and power-sharing structure, was astounding. The movement included antithetical worldviews that would have split most movements many times: socialist and nonsocialist; traditional and revolutionary; religious and secular; political Zionists determined on statehood and culturalists who abjured political goals. Nothing better demonstrates how the logic of inclusion worked than the case of religious Zionists. This logic was expressed by Max Nordau at the Third Zionist Congress, in 1899, when he appealed to religious Jews to join the movement: “Within Zionism everyone is guaranteed full freedom to live according to his religious convictions.…For we do not have the possibility of imposing our will on you if it happens to be different from yours!” [38] One of the most vigorous debates in early years was over the push of cultural Zionists, led by Ahad Ha’am, to institute a program of Jewish national education, which was seen by religious Zionists as a threat to their traditional role in education. This led to the recognition, in the Fifth Congress, of “two streams with equal rights—the traditional and the progressive,” and to setting up two committees to correspond to the two views.[39]

In a pattern that was to continue, religious Zionists formed coalitions with other groups to protect their own interests. Herzl obtained their support—most notably in the emotional 1903 “Uganda” debate over the idea of Jewish colonization in British East Africa—in return for holding the line on the educational demands of the Ahad Ha’amists.[40] Power-sharing, decentralization, mutual veto, coalition-building, multidimensional politics—features of consociational democracy that had their counterparts in traditional Jewish politics—flourished in this setting.

| • | • | • |

The Arab Issue

Relations between Jews and Arabs in Palestine “are totally different from those of the Jewish people with any other throughout its lengthy history.” [41] Jewish political traditions were of little use in dealing with non-Jewish nationalities within its own sphere. Jewish politics dealt with the non-Jewish world as a separate and hostile external environment, to be kept at bay as far as possible. Early Zionists thus had no precedents upon which to rely regarding the place of an Arab population in a Jewish state, as the very confusion of their responses would indicate.

The Zionist response to the Arab presence represents the usual spectrum of human adjustment to uncongenial realities: avoidance, denial, wishful thinking, hostility (and sometimes some or all of these responses simultaneously). And while the very profusion and confusion of the responses are testimony to lack of clear guidelines in tradition, most were consonant with one aspect or another of this tradition.

Avoidance is a normal response to a problem that did not exist in the past. For the Zionist pioneers, Palestine was effectively empty because “they did not expect to model the society they intended to build upon anything provided by the indigenous population.” [42] Theodor Herzl, when he passed through a large number of Arab villages during his visit to Palestine, made no references to Arabs in his diary or his written reports afterward: “the natives seemed to have vanished before his eyes. . . .” [43] Apart from the inconvenience of their presence, the invisibility of the inhabitants was probably reinforced by the assumption in European nationalism—also basic to Zionism—that a people without a state did not, in fact, have a national identity. In any event, such myopia was common among Zionist leaders, especially those outside Palestine (inside Palestine it was harder to ignore the issue), in the period before the Young Turkish Revolution of 1908 pushed national questions to the fore. Furthermore, it has persisted as a recurring phenomenon throughout the history of the conflict, often in the form of a tendency to minimize the importance or reality of Israeli Arab issues (as in David Ben-Gurion writing, in 1952, that Israel “was virtually emptied of its former owners” even though Arabs still constituted 12.5 percent of its population).[44]

One form that avoidance took among early Zionists was to place an undue weight on the achievement of a Jewish majority. Once Jews could simply outvote the Arab population in Palestine, it was felt, all would be settled in congruence with democratic procedures and the “minority problem” would fall into place. Even Ahad Ha’am, whose famous 1891 article on the Arab issue was the first to challenge the prevailing avoidance of the issue, came eventually to the conclusion that a Jewish majority would make it possible to respect Arab rights as individuals while achieving Jewish national rights in Palestine.[45] But as Jewish history demonstrates, establishing the right of a majority to rule does not, in itself, resolve the issue of minority rights.

Most Zionists, however, found it impossible simply to ignore the Arab problem. As time went on, especially among those settled in Palestine, better answers were required. The publication of Yitzhak Epstein’s article “The Hidden Question” in Hashiloah, in 1907, inaugurated a vigorous debate over attitudes toward the Arabs, which Epstein defined as a question “which outweighs all others.” [46] This debate did not, however, provide any resolution but reflected the confusion on the issue. The very proliferation of ways of viewing Arabs—as Semitic cousins, as natives, as Gentiles, as Canaanites, as an oppressed class, as a second national movement alongside the Jewish one—indicated the lack of a clear dominant view.

Naive assimilationism was a response favored by some early settlers, who recognized that the Arab presence could not be ignored but who sought to deny the reality of any underlying conflict. The established population could be viewed as kinsmen, as direct descendants of the ancient Hebrews who would willingly cooperate in the reestablishment of the ancient homeland. Even if they did not convert to Judaism, an appeal on the grounds of common ancestry and ethnic kinship might serve to reconcile Arabs to the Zionist enterprise.[47] Such ideas did not strike a chord among either Jews or Arabs, however, and withered over time. Nevertheless, they did not die out completely; in the 1930s, Rabbi Benjamin (Yehoshua Radler-Feldmann, founder of Brit Shalom, a movement that advocated a binational ArabJewish state) was still promoting his own version of pan-Semitism.[48]

Paternalism was another variant of the approaches that sought to transcend Arab-Jewish conflict by stressing common interests. The Westernized Jews who led the Zionist movement saw the native population of Palestine as a backward people who could only benefit from the blessings of modern civilization that Jewish settlers would bring. When Herzl finally dealt with the Arab problem, in Altneuland, he portrayed an Arab notable deeply grateful for the economic prosperity and modernization brought by Jewish skills; Max Nordau, in defending Herzl from Ahad Ha’am’s accusations of insensitivity on the issue, argued that Jews would bring progress and civilization to Palestine just as the English had to India. Chaim Weizmann later explained to Lord Balfour that the Arab problem was economic rather than political and that Zionism would coexist peacefully with the Arabs of Palestine by insuring economic development.[49] Of course all of this was being argued at a time when the superiority of European culture and the advantages of its diffusion were articles of faith and “colonialism” was still considered a progressive concept in the West.

Class solidarity was a more sophisticated path for denying the reality of a national conflict. Labor Zionists argued that the common class interests of Jewish workers and the masses of impoverished Arab peasants created the basis for joint action against the (Arab) effendi, or landowning class. Despite the lack of response from the Arab “proletariat,” this conception had at least two practical advantages that guaranteed it a long lease on life. First, Arab hostility to Zionism could in this view be attributed to the reactionary interests of the effendi rather than to the bulk of the Arab population, with which Zionism was said to have no quarrel. Second, analysis on a class basis made it possible to skirt the issue of whether the Arabs of Palestine constituted a nation or a people, equal in status (and rights) with the Jewish people.

In reality, both paternalistic and class solidarity perspectives, like the naive kinship theories, saw assimilation as the answer to the Arab problem. The basis and form of assimilation had simply become more sophisticated. All three assimilationist approaches had in common the denial of an objective conflict between the Arab and Jewish populations in Palestine, or at least a stress on common interests that would override conflicts. They stressed the material benefits that would accrue to the Arab population, whose interests are defined as economic or social rather than political or national. As Herzl wrote in an oft-quoted letter to Ziah El-Khaldi in 1899, “[Arab] well-being and individual wealth will increase through the importation of ours. Do you believe that an Arab who owns land in Palestine…will be sorry to see [its] value rise five- and ten-fold? But this would most certainly happen with the coming of the Jews.” [50]

Behind the stress on material benefits lay the even more important tendency to recognize Arab rights on the individual level, and not as a national group. This was of course entirely consonant with the traditional Jewish view of non-Jews, who were accorded humane treatment as individuals but were not recognized as a collectivity. Needless to say, it also fit perfectly into the political arguments being made by the Zionist movement. The demographic realities of Palestine at the time lent some credence to this view; Arab nationalism was in its infancy, a strong Palestinian Arab identity had yet to take shape, and both Jewish and non-Jewish observers tended to describe the population in segmented terms as “Muslims,” “Christians,” or according to tribal or clan affiliations.[51]

This distinction between individual and national rights made it possible for Zionist leaders to affirm full support for the civil rights of the non-Jewish “residents” or “inhabitants” of Palestine, while pressing the Jewish national claim to Palestine as a whole. David Ben-Gurion, for example, could argue that “we have no right whatsoever to deprive a single Arab child…” while also making the claim that in a “historical and moral sense” Palestine was a country “without inhabitants.” [52] Even those who did recognize the Arabs as a nationality or as a parallel national movement—a number that grew over time—still tended to deny that they possessed the same kind of national rights in Palestine that Jews did. At best, they might be accorded the status of a recognized and protected but subordinated minority.

Separatism was the natural response of those who found the various assimilationist models untenable or undesirable. While the label covers a spectrum of responses, what they had in common was belief that Zionist goals, even in the minimalist version, were bound to be unacceptable to the Arab population of Palestine and that a clash of interests was inevitable. While some thought that this clash might be worked out in nonviolent ways, all saw a strongly competitive element in the relationship and felt that the integrity and security of the Zionist undertaking dictated a course of selfreliance rather than pursuing the chimera of Jewish-Arab collaboration.

In some ways, those skeptical about assimilation found it easier to recognize and deal with Arabs as a collectivity. Since they did not expect Arabs to forego their national identity in pursuit of individual or material gain, Arab nationhood could be viewed as a simple fact of life. This did not necessarily mean recognition of equal national rights, but at least as recognized rivals Arabs were visible as a group.

In later years, separatism was increasingly a defense against Arab hostility. Among the followers of Ze’ev Jabotinsky it took the form of preparation for the armed conflict that was regarded as inevitable. But streaks of separatism appeared among nearly all Zionist groups, as a natural (and Jewish) response to an environment perceived as basically hostile. Jews had been unremittedly conditioned over long historical periods to regard the external environment as hostile; in traditional terms, the Arabs were simply the latest group of Gentiles to whose hatred Jews were exposed. This seemed to be readily confirmed in the Palestinian context: Arabs refused to recognize Jews as a people or nation with rights in Palestine; they engaged in frequent acts of anti-Jewish violence that were seen as a continuation of traditional anti-Semitic persecution; and they displayed no interest in the various visions of integration or cooperation that more idealistic Zionists put forward.

Zionist approaches to the Arab question thus moved between integrative and separatist strategies.[53] While particular leaders and parties could and did mix elements from different strategies, there were often conflicts and inconsistencies as a result: Arabs could not benefit fully from the Jewish enterprise without being a part of it nor could security considerations take precedence without impinging on Jewish-Arab interaction. Both tradition and the immediate environment gave mixed signals on how to resolve these dilemmas, and many were left unresolved then as well as after the founding of the state. But at the same time, it must be said that both tradition and the immediate environment gave an advantage to separatist tendencies over the integrative visions.

For example, Labor Zionists, who might have been in the forefront in developing institutions of class solidarity with Arab workers, opted instead for “socialist separatism.” This was extended to the principle of avoda ivrit, the employment of Jewish labor in all Jewish enterprises in the yishuv. It was simply assumed, with little explicit thought of exclusion, that the institutions of Zionism were established by and for Jews. Arab participation in them was not a major issue, even if it did cause ideological difficulty for a few. While such practices appear as illiberal discrimination to later generations, at the time they had the progressive connotations of self-reliance, the rebuilding of a normal Jewish occupational structure, and the avoidance of colonial practices based on exploitation of cheap native labor.

| • | • | • |

Under the Mandate

Under the millet system of government in the Ottoman Empire, each ethnoreligious community enjoyed a wide degree of autonomy in its own internal affairs. The Jewish community in Palestine, including the new Zionist settlements, had exploited this to establish its own institutions covering a broad range of religious, educational, cultural, economic, legal, and even political matters. The customary British style of indirect rule, as practiced in the new Palestine Mandate after World War I, gave even more latitude to the growing yishuv (which increased from 60,000 to 650,000 during the Mandatory period). But in contrast to most colonial situations, institutions were not copied from the colonial power. There is some debate about the influence of the British model on the development of the Jewish (later Israeli) political system, but in summary it appears that the major British contribution—apart from the idea of a cabinet with collective responsibility and some parliamentary trappings—lay in the realm of legal and judicial practices. The British established English (along with Arabic and Hebrew) as an official language in the courts, appointed British judges to the senior positions, and established the legal education system used throughout the Mandatory period. Ottoman law remained in effect where not supplanted, but most of it was replaced by Mandate legislation (on the British model) by 1948, while English common law was used to cover gaps in existing law. Thus legal and judicial institutions and practice were the main legacy directly inherited by the Jewish state from the Mandatory power (or from any Western source).[54]

For the rest, the Jewish community drew on its own experience in communal politics and on already existing Zionist institutions, including those established in the yishuv before the British came on the scene. There is striking institutional continuity from the earliest Zionist bodies, through the period of the British presence, to the State of Israel. The Jewish community succeeded during the Mandate in establishing its own state-within-a-state, complete with institutions that in some cases—political parties, educational and cultural groups, charitable and welfare bodies, burial societies, religious organizations, economic guilds, workers’ groups, and even private companies—were hardly more than a transplant from the Diaspora. Whatever the importance of previous experience in this community-building enterprise, by the end of the Mandatory period the Jewish community had far outstripped Palestinian Arabs in establishing communal self-government, providing a solid foundation for Jewish statehood.

The central Mandate structures established by the British lacked legitimacy in the eyes of both Jews and Arabs, and had little impact on either. Palestine consisted of two communities with little in common: each had its own political system, educational and cultural bodies, and military forces. The two communities lived apart; there was almost no social interaction, and even economic relations were limited. Efforts to establish overarching common bodies almost always failed, and relations between Arabs and Jews were closer to the model of an international system than to coexistence within a shared political framework.[55]

Within the Jewish community matters were quite different. The terms of the Mandate called for the creation of a Jewish body to advise the British on matters related to the Jewish national home, and the Jewish Agency (effectively an extension of the World Zionist Organization) was set up for that purpose. At the same time the British authorities also officially recognized the Jewish community in Palestine as a legal entity (Knesset Yisrael, the Assembly of Israel), and allowed it to select governing bodies. These bodies were set up as a three-tiered structure—Assembly of Delegates, National Council, Executive Council—modeled on the structure of the World Zionist Organization.[56] Membership in Knesset Yisrael was still voluntary, as individuals could withdraw if they chose (and many of the anti-Zionist Orthodox did so). Otherwise voting was universal (including women) and secret, with seats awarded to party lists on a proportional basis (the same system used before and since). The existence of two parallel structures—the Jewish Agency and Knesset Yisrael—also perpetuated the tradition of competing centers of authority.

The leadership of the yishuv still faced the problem of the kahal: how to make decisions binding on all groups within the Jewish community. Since the cost of being outside the communal arrangements was relatively low, minorities possessed almost a veto power. The leadership focused on the building of coalitions that were as inclusive as possible and on a political system described as an “open-ended, informal set of federative arrangements.” [57]

Even during the period of greatest crisis, the yishuv remained largely united and politically stable, in part because of the “autonomism” of the constituent bodies.[58] The acid test came in relations with the Revisionists, who eventually split with the Labor-dominated center and attempted to form their own rival bodies. But the strategy of separation proved to be self-defeating, helping Labor Zionists (primarily Mapai at the time) to delegitimize their opponents as the subverters of Jewish unity during a time of troubles.[59]

The yishuv organized itself as a “quasi-state” within the Mandate framework and established the institutions that were to dominate Israeli life. The Histadrut, or Labor Federation, grew to play a role in the economy far beyond that of an ordinary labor union. The Jewish Agency, as an organ of the World Zionist Organization, handled relations with Jewish communities abroad, represented the interests of the yishuv diplomatically, and coordinated immigration and settlement within Palestine. The bodies elected by Knesset Yisrael levied taxes and supported religious and other institutions. At the center were the political parties, which were actually ideological movements. Together with the Histadrut, the parties provided a set of institutions and services substituting for the governmental and societal infrastructure that did not exist: schools, newspapers, banks and loan funds, health-care plans, youth movements, sport clubs, housing companies, and various welfare services. Most of the new settlements were established by particular movements. The centrality of the parties in Israeli politics is not just a result of the electoral system; rather, it was the dominance of parties that shaped the electoral system.

Observers have noted the similarity of pre-state Jewish politics to consociationalism, or to similar concepts of “compound polity” or “segmented pluralism.” [60] Society is organized into separate camps, each with its own institutions, that share power and distribute benefits proportionately by a process of bargaining and coalition-building. In the yishuv, Labor Zionists were forced to share power despite their central position; grand coalitions (or more than minimal winning coalitions) rather than simple majority rule was the practice; the political system was multidimensional, being split along several axes; there was separation of power between competing authorities; and representation was proportional.

Again, the classic expression was in relations with the religious Zionists. The patterns of power-sharing initiated in the World Zionist Organization carried over into the yishuv. Beginning in the 1930s, the secular leadership of the yishuv made explicit arrangements with the religious Zionist parties (Hapo’el Hamizrahi and Mizrahi ) on the proportionate division of jobs and other benefits, beginning a forty-year period of partnership between Labor Zionists and religious Zionists. Efforts were also made to bring Agudat Yisrael, representing the haredi (ultra-Orthodox) non-Zionists or anti-Zionists (the “old yishuv ”)within the purview of the new communal institutions. Chaim Weizmann sought throughout the 1920s to bring Agudat Yisrael into the National Council, which had the advantage of controlling most of the funds available. In the first stage, this led to Zionist funding of Agudat Yisrael educational institutions, and later, in 1934, to formal cooperation between Agudat Yisrael and the World Zionist Organization. Finally, following World War II, the Agudat Yisrael leadership supported the establishment of a Jewish state, and in return David Ben-Gurion, the chairman of the Jewish Agency, pledged public adherence to certain basic religious laws.

The system of proportional representation adopted was (and remains) the purest form possible. Parties submitted rank-ordered lists of candidates, but voters chose a party rather than individual candidates. Each party then received a proportion of seats matching its proportion of the vote (if there were one hundred seats, a party with 10 percent of the vote would be awarded ten seats, which would go to the first ten candidates on its list). Proportional representation was maintained as the only method of drawing in all parties on a voluntary basis, and the principle of proportionality was extended to all appointive positions, to the allocation of funds, and even to the distribution of immigration certificates.[61] This method of allotting benefits according to “party key”—that is, in strict proportion to electoral success—was also, obviously, one of the incentives for voluntary cooperation and one of the coercive tools available to those at the center, who could (and did) withhold funds or immigration certificates from those who broke ranks.

This reality was quite different from what socialist ideologues originally had in mind. In the early 1920s, with the Soviet experiment just underway, they had envisioned building a society along entirely new lines; when the Histadrut was founded in 1921, Ben-Gurion advocated organizing it as a country-wide commune with military discipline.[62] Despite the dominance of agrarian socialist ideology as the governing paradigm of the new society, the gap between it and reality became enormous. The dominance of Labor Zionism, for about half a century beginning in the late 1920s, is in many respects a puzzle. Neither the pre-Zionist Palestinian Jewish community (the “old yishuv ”) nor the pioneers of the first aliya were disposed to secular socialism. The second aliya (1905–1914) is generally regarded as the generation that established Labor’s hegemony, but the prevailing image of this group has been challenged. Daniel Elazar concludes that among the 35,000 to 40,000 who immigrated during these years “relatively few of those thousands fit what was to become the mythic mold of the young Eastern European Zionist socialist revolutionaries who come to the land to fulfill the ideals of Russian-style Marxism, Zionist version.” [63] At the end of World War I the number of “pioneers”—rural and urban laborers with Zionist commitments—was in the low thousands, and of these only an estimated 44 percent identified with the socialist parties.[64]

The third aliya, in the years immediately following World War I, presents a somewhat different picture. This group, mostly from revolutionary Russia, was significantly more radical than its predecessors.[65] Yet, given the still modest numbers involved, this did not radically alter the demography of the yishuv. Furthermore, beginning in 1924, immigration was no longer limited to self-selected volunteers imbued with strong Zionist motives. As the gates of entry closed in the United States and other traditional places of refuge, Palestine became the destination of entire communities of persecuted Jews who simply had nowhere else to turn. The fourth aliya, in the mid-1920s, brought in a number of middle-class Polish Jews fleeing antisemitic economic measures. The fifth aliya, in the 1930s, was triggered by persecution in Germany, Austria, Poland, and Romania, which forced many urbanized, professional Jews to seek refuge in Palestine. Another 100,000 refugees from the Holocaust arrived, legally or illegally, during the 1940–1947 period. Later came the “displaced persons” from World War II. After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, there was a mass influx of entire Jewish communities from the Arab world. Altogether, about two million Jewish refugees reached Palestine or Israel during these years. These refugees and their descendants constitute a vast majority of the present population of Israel. Any explanation of Israeli political attitudes that does not begin with this reality—that Israel is a nation of refugees—is inadequate.

The agrarian image of a return to the soil, as fostered by kibbutz ideology, was always exaggerated. A majority of new immigrants settled in cities; at its peak, in the 1930s, the agricultural sector accounted for less than a third of the Jewish population. The gap between ideology and reality was reflected in a 1945 survey of Jewish schoolchildren in which 75 percent declared that agriculture was the most important career for building the country—but only 12 percent planned to become farmers.[66]

The puzzle, then, is not the eventual decline of Labor Zionism but rather its long hold on power. During this period, the bulk of the population came holding no strong prior commitment to socialism, the dignity of manual labor, a return to the soil, a change in the traditional Jewish occupational structure, the secularization of Jewish life, a pragmatic approach to territorial issues, or other features of an ideology rooted in the ferment of late nineteenth-century Eastern European revolutionary movements. They did not come to Eretz Yisrael in order to wage a “revolution against Jewish history.”

How did Labor Zionists achieve their hegemony? First, while beginning as a minority even in the earlier aliyot, the socialists were intensely committed and tireless organizers. By the time that massive immigration began, they had built an infrastructure (the Histadrut, for example) to absorb and socialize (in both senses) the newcomers. Second, at least some of the new immigrants, having passed through the wrenching experience of persecution and flight, were more open to radical Zionist perspectives than they had been previously (and the Holocaust demonstrated what their probable fate would have been had the Zionists not provided, exactly in line with Herzl’s original vision, a haven from the tempest). Third, the fact that they were building a “new society” made it easier for the Zionist pioneers to apply their ideological precepts. They began with a clean slate, freed of the need to deal with established institutions. The “old rulemakers,” those who might have resisted the new doctrines, were underrepresented and outgunned.[67] Fourth, the decision of Labor Zionists to focus on “practical” Zionism, on the patient construction of a base in Palestine itself, translated over time into an enormous advantage over those (such as the Revisionists) who continued to focus on the world stage or on Zionist politics outside Palestine. Finally, once Labor Zionists actually did control the center in Palestine, they were able to use their leverage effectively to legitimize and propagate their version of Zionism as the standard brand.[68]

Moving into leadership of the yishuv meant, of course, further compromise with realities, and a wider gap between ideological premises and practical policies. This is pointed out most acutely by Mitchell Cohen, who argues that Labor Zionists achieved dominance by shifting to a policy of “revolutionary constructivism” that separated the concepts of class and nation, stressing the development of the yishuv as a whole rather than classical socialist goals. This strategy isolated and overwhelmed the Revisionist opposition of the time, but at the cost—in Cohen’s view—of subverting Labor Zionism’s own future. This move from “class” to “nation” can indeed be seen as an abandonment of socialist ideology, at least in its purest form, but it can also be seen as a move toward a more “civic” conception of the political order, even in the context of communitarian Jewish political practices. The culmination of this came after statehood with Ben-Gurion’s efforts to instill a “civic culture” (mamlachtiut) into Israeli political life (see chapter 4).

Another reinforcement of the move to greater pragmatism was the fact that by the late 1930s security had become a major obsession. At the outset Labor Zionists had believed that their goals could be achieved without displacing the Arab population in Palestine or injuring its basic interests. This was perhaps somewhat utopian, since the minimal Zionist aim—a Jewish state in at least part of Palestine—was never likely to be acceptable, in an age of rising Arab nationalism, to an Arab population that regarded its claims to Palestine as exclusive.

In any event, each new wave of Jewish immigration evoked a new round of violence; there were widespread Arab assaults on Jews in 1920 to 1921 and in 1929, while in 1936 to 1939 there was a general uprising that approached the dimensions of a civil war. In addition, leadership of Palestine Arabs passed into the hands of more fanatical elements, and in particular those of Haj Amin Al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem. The mufti, whose forces liquidated many of the more moderate Arab leaders during the 1936–1939 period, preached the destruction of the Jewish community in Palestine and later fled to Nazi Germany where he gained notoriety by endorsing the Nazi solution to the Jewish problem.

The impact of this on the yishuv was to discredit efforts to achieve a negotiated settlement of Arab-Jewish issues. Those who promoted such an effort—in particular, Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization during much of this time—were gradually pushed aside by those within the Labor Zionist movement who stressed the need for self-defense and for creating facts on the ground. Foremost among the latter was Ben-Gurion, who by the early 1930s had become the most prominent leader in the yishuv.

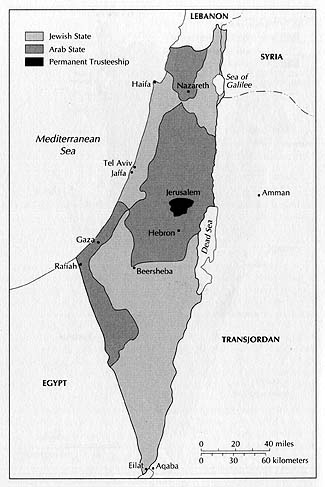

But while Ben-Gurion represented a “realist” perspective on the question of diplomacy versus practical measures, he also represented a pragmatic approach to territorial issues, in contrast to the Revisionists. The leadership of the yishuv had reluctantly come to terms with the British partition of the Palestine Mandate, in 1922, by which 77 percent of the original Mandate—everything east of the Jordan River—was established as the Emirate of Transjordan under the rule of Abdallah, Faisal’s brother, and closed to Jewish settlement. Under Ben-Gurion’s leadership, they also accepted in principle British proposals, in the late 1930s, to partition what remained into Jewish and Arab states, though there was considerable criticism of the specific borders proposed.[69] Finally, a majority under Ben-Gurion also accepted the UN partition plan of 1947, which from a Jewish perspective was an improvement on the 1930s proposals but which still left Jerusalem outside the proposed Jewish state (see Map 1).

Map 1. UN Partition Plan, 1947

The Revisionists opposed all of these measures, beginning with the creation of Transjordan, and split with the existing leadership over its acceptance of the principle of partition. As noted, they continued to insist on the priority of Jewish national rights in all of historic Palestine (including Transjordan).

There was still a tendency to avoid hard thinking about the future position of Arabs in a Jewish state by focusing on the simple push for a Jewish majority. Except for the few supporters of binationalism clustered around Brit Shalom, majority rule was the spoken or unspoken aim that unified all Zionists from left to right. The shared assumption seemed to be that the very act of achieving majority status would reduce the Arab issue to a “mere” question of minority rights, which could be resolved with a modicum of good will. Ben-Gurion referred to Canada and Finland as examples of states where a dominant majority determined the character of the state but ethnic minorities lived peacefully; he indicated, however, no understanding of the guarantees and compromises, including dilution of the state’s dominant ethnic image, often required to make such systems work.[70] There seemed to be an unquestioned confidence—one that could find little support in the contemporary history of majority-minority relations elsewhere—that the simple act of outvoting a national minority would resolve the problematic relationship. Even Jabotinsky, whose followers later minimized the importance of numbers, paid homage to the principle of a Jewish majority as the solution to existing contradictions.[71]

Only Brit Shalom, following the assimilationist logic to its conclusion, pursued a solution that was not dependent on relative numbers but gave explicit and equal recognition to the two nations in Palestine. Binationalism, however, was not what the Zionist movement was about, and such ideas remained the province of a small number of intellectuals outside the mainstream. Even the advocates of binationalism, however, assumed that Arab national aspirations, which they were ready to recognize, could be limited and accommodated within a partly non-Arab framework, and in this they also seem to have misread Arab thinking. The lack of Arab interest and response, no less than the lack of Jewish support, led to the demise of Brit Shalom.

The advocates of paternalistic cooperation and class solidarity were also weakened by lack of response and the unfavorable turn of events. Those who put their trust in the blessings of Western civilization turned naturally to Great Britain, the Mandatory power, as intermediary in the civilizing mission. Chaim Weizmann, among others, saw the British presence as obviating the need to negotiate directly with the Arabs; in time this clearly became a weak reed. Labor Zionists acted intermittently on the basis of presumed common interests with Arab workers, as when they urged restraint in response to the Arab riots of 1929 on the grounds that there was no “real” conflict between the two peoples.[72] At least as late as 1936, mainstream leaders in Labor Zionism still professed to believe in collaboration on a class basis; in a book published that year, Ben-Gurion states, in a typical passage: “The majority of the Arab population know that the Jewish immigration and colonization are bringing prosperity to the land. Only the narrow circles of the Arab ruling strata have egotistical reasons to fear the Jewish immigration, and the social and economic changes caused by it. The selfinterest of the majority of the Arab inhabitants is not in conflict with Jewish immigration and colonization, but on the contrary is in perfect harmony with it.” [73]

How far Ben-Gurion actually believed this, by 1936, is open to question, but the dogma of class solidarity remained in the public rhetoric of Labor Zionist leaders even after the 1936–1939 Arab uprising. After World War II, when leftist Labor Zionist groups merged into the United Workers Party (Mapam), they continued to advocate “cooperation and equality between the Jewish people returning to their land, and the masses of the Arab people residing in the country.” [74]

But the stance of Labor Zionist groups was contradictory, since they continued to promote avoda ivrit and to maintain the Histadrut and other labor organizations as purely Jewish institutions. A consistent policy of class solidarity would have necessitated the development of frameworks for joint action, but even Hashomer Hatsa’ir (the most doctrinaire party) chose to postpone discussion of a joint Jewish-Arab workers’ association (the other parties rejected it outright).[75] Furthermore, Labor Zionists, as other Zionists, continued to differentiate between the national rights of the Jews in Palestine and the rights of Arabs to continue living there as inhabitants or residents, that is, as individuals. Ben-Gurion tended to refer to a Jewish “people” and an Arab “community.” Even when the existence of an Arab people or nation was conceded, it was usually described as part of a larger Arab nation rather than as a group with distinct national ties or claims to Palestine.[76]

The Arab uprising of 1936 to 1939 had a double impact on Zionist attitudes. In its wake, it became harder to deny the existence of an Arab national movement in Palestine, encompassing not simply an unrepresentative landowning class but a broad spectrum of the Arab population. Still, recognition of Arab nationality did not necessarily imply recognition of equal national rights in Palestine. A second result was to make many advocates of cooperation into advocates of separatism. These two developments were related: those who had advocated assimilation in various forms, and were now forced to recognize the strength of Arab particularism, came to separation as the next logical course. The practical expression of this was support for the idea of partition, which drew its strength largely from those in the middle of the spectrum who had supported cooperation.

The partition plans floated in the late 1930s created, not for the first time, some strange alignments and bedfellows within the yishuv. Groups on the left opposed partition and clung to visions of Jewish-Arab cooperation in an undivided Palestine. Other opponents were the Mizrahi (religious Zionists), who opposed partition on biblical grounds, and of course Jabotinsky’s Revisionists on the right. Even some of Ben-Gurion’s own party members deserted him on the issue, but on the other hand he gained many partition supporters from among the liberal and centrist, nonsocialist parties.

One of the ironies of the partition debate was that some of the new supporters of partition were now more committed to separatism in principle than were the Revisionists. While the Revisionists had no plans to assimilate with Arab society, they preferred living with a large Arab minority to dividing Palestine. As noted, Jabotinsky had less trouble recognizing the Arab national movement than did his more liberal opponents. In fact, taking Arab nationalism seriously was a cornerstone of his thought. He simply recognized it as a rival nationalism and planned to defeat it by massive Jewish immigration and (if necessary) military force.

For some advocates of partition, however, the idea of a “transfer” appeared as a logical and just corollary of the division of Palestine: if Jews were to accept a state in only part of the homeland, then at least they should be relieved of a hostile population that would best be relocated to the Arab state to be created. The concept of “population transfer” did not then carry the negative connotation that it acquired later; following World War I, a large number of transfers had been carried out more or less peacefully. As it happened, the idea was never taken seriously.[77] But the fact that it was mentioned does suggest that at least some yishuv leaders no longer believed that the achievement of majority status would automatically resolve minority issues.

The debate on the “Arab problem” during the Mandatory period is very instructive. The strange and fluid configurations that developed when practical decisions on Arab relations had to be made clearly illustrate the inadequacy, confusion, and arbitrariness of the guidelines furnished by historical experience and prevailing ideologies. The debate over partition was but one case; similar kaleidoscopic variations could be observed regarding debates over British proposals for legislative councils and important debates within the Zionist movement (for example, over such issues as publishing an Arabic-language newspaper or admitting Arab members to yishuv institutions). Nor were the positions of individual leaders much more predictable than those of the shifting party and organizational alignments. Ben-Gurion went through five or six different stages in his approach to Arab issues, according to close observers.[78] Clearly this was one area in which consensus did not exist.

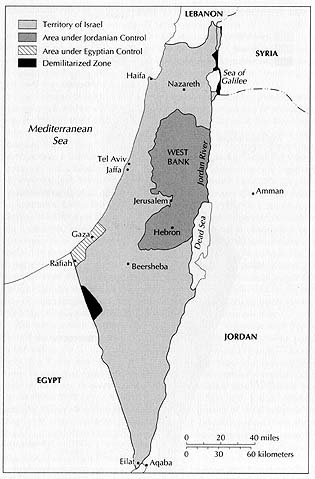

Nevertheless, by the end of World War II the Jewish community of Palestine had achieved tremendous cohesion, unity, and determination in the face of adversity. Despite internal divisions that sometimes led even to bloodshed, the yishuv was able to maintain a level of organization and self-defense extraordinary for a community without formal governmental powers: it levied and collected taxes, established an army, represented its own interests internationally, administered welfare and educational services, and set its own economic and social policies—all on a voluntary basis. The strength of this social cohesion was apparent in the 1948 war, in which Jewish fighting forces managed not only to retain control of the territory allotted to a Jewish state but also to capture additional territory, including most of Jewish Jerusalem and a corridor linking it with the rest of Israel (see Map 2).

Map 2. Armistice Agreements, 1949

Notes

1. Shmuel Ettinger, “The Modern Period,” in A History of the Jewish People, ed. Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson (Harvard University Press, 1976), 790–93.