3. Conflicting Generations

Unreciprocated Houseflows in a Modern Society

At the same time that the people in West Bengal spoke to me of family moral systems that bound persons together across generations, they also worried that the ties connecting persons within families were becoming increasingly loose. I asked one old man, Rabilal, a Mangaldihi beggar of the Muci (leatherworking) caste, what happens when someone gets old, and he replied pessimistically, “When you get old, your sons don’t feed you rice.” The young girl who cleaned my home, Beli Bagdi, responded when I asked her what would happen to her when she became old: “Either my sons will feed me rice or they won’t; there’s no certainty.” In Bengal’s villages and cities, wandering beggars, mostly aged, drift from house to house in search of rice, a cup of hot tea, or a few coins. Old widows dressed in white crowd around the temples in pilgrimage spots waiting for a handful of rice doled out once a day. The opening scenes of the popular Bengali novel and film Pather Panchali feature a stooped, toothless old woman who, with no close living relatives, must wander from house to house in her village, constantly moving on after the initial welcome fades (Bandyopadhyay 1968). The powerful 1993 documentary Moksha (Salvation), directed by Pankaj Butalia, portrays destitute Bengali widows at a Brindaban ashram; they recall poignantly the fights and rejections they experienced in the homes of their sons and daughters-in-law, and their utter loneliness in their separation from kin.

In this chapter, I explore family moral systems from the perspective of the problems and conflicts built into family relations, and in the process I also look at constructions of modernity. For Bengali narratives of modernity center on images of loose, unconnected, uncared-for old persons, who become paradigmatic signs of a wider problem of a disintegrating “modern” (ādhunik) society.

| • | • | • |

Contrary Pulls

According to the Bengalis I knew, family conflicts were the most common source of affliction facing people in old age. Four kinds of intergenerational relations seemed to generate the most problems: relations between mothers-in-law (śāśuṛī) and daughters-in-law (bou), between mothers and married sons, between fathers and sons, and between mothers and married daughters. Mangaldihians viewed these four dyadic bonds as particularly prone to attenuation, partly because of their tendency to conflict with other family bonds. As Margaret Trawick (1990b:157) writes about Tamil families: “At certain times in his or her life, [the] different kinds of bonds [between generations, between siblings, and between spouses] are likely to pull an individual in different directions. As one bond grows closer, another may stretch and break, and someone may be left out in the cold.” I was told that bonds between generations were especially vulnerable, as members of each generation moved on to new phases of life and the “pulls” (ṭān) of the relationships that these life phases entail. When a son turns toward his wife, he may turn away from his mother. When a daughter-in-law turns toward her own children, she may neglect her parents-in-law. When a daughter moves to her husband’s home, she becomes largely “other” to her parents. If a father turns toward God and death, he abandons his mourning sons.

In addition, there are fundamental problems in how relations of intergenerational reciprocity, and family (re)production and exchange systems, are structured in West Bengal. The whole system—as I began to explore in the previous chapter, and as will become more clear below—pivots on a kind of contradiction, as families send their “own” (nijer) daughters away to become “other” (par) and bring “other” women into their houses to become “own.” The women on whom families depend to produce sons and provide much of the labor of caring for elders are thus perceived—by both themselves and others—to be partly “own” and yet at the same time still “other.” This ambiguity in the position of women within households, we will see, was the source of many of the conflicts and ruptures within Bengali families.

Mothers-in-Law and Daughters-in-Law

(The problem of bringing in women from “other” houses)

The family relationship perhaps most fraught with tension and contrary pulls, and the one most often blamed by Mangaldihians for the neglect of elders, was that between mother-in-law (śāśuṛī) and daughter-in-law (bou or boumā).[1] Mothers realize when they bring a new wife into the household that they will be largely dependent on her for their well-being in old age. Daughters-in-law cook, serve food, clean clothing, lay out beds for sleeping, massage cramped legs, and comb hair. It is they who will eventually control most of the household affairs, and decide either to provide or not to provide the day-to-day service (sevā) to fulfill their mothers-in-law’s needs and desires. A daughter-in-law may also have the power to take a son’s loyalties away from his parents and even to persuade the son to begin a separate household of his own. Mothers are thus nervous when they arrange their sons’ marriages. They search carefully for a bou who will be deferential, who will be loyal to her elders, and who knows how to work and to serve well. But they never know for sure. “After all,” one woman explained, “my son’s wife is not my own belly’s daughter (āmār nijer peṭer meye nae); she is the daughter of another house (anya gharer meye).”

During the first years after a woman’s marriage, however, it is the daughter-in-law (bou) who lives under the authority of her mother-in-law (śāśuṛī). A mother-in-law generally maintains control over domestic affairs for several years after a son’s marriage, and she therefore determines which household chores the bou performs, whether and where the bou can come and go from the household, and when and if she may spend time alone with her husband. During this time, the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationship can be very loving and tender. Many women told me stories of how good their śāśuṛīs had been to them when they were young and first married, and several compared their śāśuṛīs to their own mothers. Some, who had been married before adolescence, spoke of sleeping at night with their śāśuṛīs for several years, until they were grown enough to sleep with their husbands; and one, as I noted earlier, told me that she had even nursed at her śāśuṛī’s breasts when she had been married years ago at only five.

But the śāśuṛī-bou relationship can also be a very difficult and bitter one for a young daughter-in-law. Many complained that their mothers-in-law ordered them around unfairly, treated them like servants (dāsīs), and prevented them from getting close to their new husbands. Indeed, a young husband and wife generally will not spend much time at all together during the day, and when they are in the presence of others they may not exchange more than a word or two. Such reticence demonstrates the young couple’s modesty, as well as ensuring that the new bou will form strong relationships with other household members and not an exclusive one with her husband. Usually the new husband and wife will have a separate room to share at night, but a śāśuṛī will often keep her new bou up later than anyone else in the household and have her rise the earliest, thereby minimizing the time she can spend alone with her husband. Older women told me stories about how their śāśuṛīs used to guard their activities outside of the house as well, following them to the bathing ghāṭ (bank of a river or pond) and back with a stick to make sure that they did not loiter or talk to any men along the way.

Several local tales illustrate this vision of the śāśuṛī as a dominant near-tyrant ruling over her submissive and fearful bous. A group of married and unmarried women of my neighborhood told me one such story one afternoon as we sat casually talking over tea. It was ostensibly about how musurḍā>l, a favorite Bengali pulse, came to be red-orange in color and a “nonvegetarian” (ā̃aṣ) food, but it also conveys a great deal about śāśuṛī-bou relations. The story went like this:

One day a śāśuṛī told her boumā to husk some musurḍā>l. She told her to bring at least one kilogram to her when she was done. So the bou went off to do her task. She soon realized with dismay, though, that the husked ḍā>l would not come out to be a full kilogram. What would her śāśuṛī do? Out of fear of her śāśuṛī the boumā took her little son and cut him up into bits to mix with the ḍā>l. The blood from her son mixed with the ḍā>l, and this is how it became ā̃ṣ [or āmiṣ, “nonvegetarian”] and how it got its reddish color.

“You see,” one woman interrupted, “how fearful boumās used to be of their śāśuṛīs? That she would even kill her son out of fear of not complying with her śāśuṛī’s request?”

The teller went on:

The next morning a bird called out, as it still does today, “ Pāye paṛa uṭh putu! Pāye paṛa uṭh putu! ” which means, “Get up, little boy! Get up, little boy!” [2] But how could he get up? He was dead. The śāśuṛī then found out what had happened, and she was even more enraged with her bou.

“So, you see,” she ended, “It’s bad if you don’t obey your śāśuṛī and it’s even worse if you do.” Gloria Raheja and Ann Gold (1994) have also compiled many vivid stories of this sort, depicting young daughters-in-law’s ambivalent attitudes toward their senior marital kin.

But gradually the tides change. Eventually it is the bou who has control over household affairs, who makes decisions about who will do what when and who will eat what when. The years of transition, while the mother-in-law slowly gives up control and the eldest daughter- or daughters-in-law take over, can be full of tumultuous struggle and competition. During this phase, the daughters-in-law are no longer so new and meek that they cannot fight back, and the mothers-in-law are not yet so feeble that their words and wills have no power. The result was some of the fiercest arguments in Mangaldihi households. I would often hear from nearby houses and courtyards the attendant screaming, pan throwing, and wailing. Women and children from neighboring households would crowd around to watch; but others would shrug their shoulders and say, “Mother-in-law and daughter-in-law are quarreling again” (śāśuṛī-bou jhagra karche), as if to imply, “What else is new?”

When a mother-in-law finally ceases to control household affairs, she becomes dependent on her bou or bous for her well-being, just as her bous were once dependent on her. Some mothers-in-law tenderly praise the loving, selfless care their bous provide for them. But, more than anyone else, it is the bou whom mothers-in-law blame for their unhappy, neglected old age. Two old women of Mangaldihi used to get together almost daily at the bathing ghat to commiserate about their bous and argue over whose bou was worse. People would tell me to go listen to them to learn about how bous mistreat their śāśuṛīs, and how śāśuṛīs never cease to criticize their bous.

Houses thus give each other women from whom they demand the most selfless devotion and exact the most onerous household labor, thereby extracting value from those who are in many ways “other” than their own. It is a little like taking a servant and, as we saw in chapter 2, the process of bringing a wife into the home is ritually referred to as just that: a groom tells his mother three times, “I’m going to bring you a servant” (tomār dāsī ānte jābo). Just as Mangaldihi villagers were never quite sure whether they could trust their servants to be honest, hardworking, loyal, and devoted, many felt that they could not really trust their daughters-in-law. (As one woman explained, “Daughters don’t even look after their own parents; how can we expect a daughter-in-law to look after her parents-in-law?”) And just as servants themselves often feel exploited, young wives frequently complain of being forced to labor too hard. It is not until a woman has lived through the period as a young daughter-in-law, has produced and raised sons of her own, and has finally brought her own daughters-in-law into the home that she fully becomes one of the “own people” (nijer lok) of a household. It is then that she herself must contend with bringing “other” wives into her house for her sons.

Mothers and Married Sons

(The problem of unreciprocated houseflows)

According to the family moral systems just described, women are expected first to serve others in their households as young wives and daughters-in-law, and then to be served as older mothers and mothers-in-law. This shift from serving to being served takes place after the wife produces a son, the hoped-for outcome of the movement of women from house to house. The bond between mother and son, according to many of the village men and women I spoke with, is stronger than all other human bonds. Sons come from deepest within their mother’s body, from her womb or nāṛī, and thus experience a tremendous “pull of the womb” (nāṛīr ṭān) for her. A mother’s milk is also a special substance, mixed with the mother’s love (bhālobāsā) and distilled from her body’s blood (rakta), which creates a great pull (ṭān) of affection and attachment (māyā) between her and her children. Moreover, a son often does not move away from his mother at marriage as a daughter does, but lives in the same home with her for the rest of her life.

Nonetheless, older women in Bengal told me many personal and folkloric narratives that pointed not to the durability of the mother-son bond but to its potential to be loosened or broken. This breaking was framed most commonly as a failure of reciprocity: the houseflows—gifts of goods, services, and love that sustain homes and relationships—are blocked before they can flow back up to the mother. Mothers told of how they poured out their breast milk, love, material wealth, and service to their sons and to others for their entire lives, but in the end they received nothing in return. Even village men often spoke to me of the service (sevā) women give throughout their lives, a service unequaled by what they receive.

Older women in Mangaldihi usually blamed such failures of reciprocation on their sons’ wives. At the center of the complicated relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law is the man who is the mother’s son and the wife’s husband. A wife is brought into the house in order to serve her mother-in-law and bear children to continue the family line; but she also often replaces her mother-in-law as the primary nurturer and most intimate partner of the son. The mother and wife may compete for years for the son’s and husband’s attention and loyalty. Sometimes the mother wins: I knew one son who was so devoted to his widowed mother that his wife ended up leaving them, returning to her father’s house with their young daughter. Many told me that the bond between husband and wife is much more fragile than that between mother and son.

From a mother’s perspective, however, it is more often the daughter-in-law who triumphs in the struggle to gain her son’s affections. Thakurma was a Kayastha (high-caste) widow, nearly one hundred years old, who lived in Batikar, a large village near Mangaldihi. She enjoyed talking about the problems of old mothers, their sons, and their daughters-in-law. She herself was proud to live in a large ancestral home with four generations of descendants still eating rice together from the same pot; but she said with sadness that she had seen during her long life the way so many other sons and bous forgot their mothers when they grew old: “Mothers raise their children with such effort and pain. But the children don’t even recognize their parents when they grow up. Children are created from their father’s blood, and they come from their mother’s deepest insides within the womb. The mother feeds them her breast milk and cleans up their urine and excrement. But does the son now remember those days? No. The mother uses all of her wealth to raise and educate her son, but at the end he gives nothing back to her.”She then began telling a story to illustrate these ways of mothers and sons, and the role bous play in tearing sons away from their mothers:[3]

“So, you see,” the old widow closed with a sigh, “mothers raise their sons with such tremendous effort and pain, but the sons forget (mārā cheleder bahut kaṣṭa kare mānuṣ kare, kintu chelerā mane rākhe nā).”There was once a mother who raised her only son with much effort and suffering. She used all of her wealth to feed him when he was young and to give him a good education; but in the end he gave nothing back to her. When he grew up and she gave his marriage, he and his wife left her alone and went to spend all of their time traveling around here and there. So what could the mother do? She ended up as a beggar. After a while she made her way to Bakresbar [a local Saivite pilgrimage spot] and there she lined up every day with all of the other old beggars with her begging bowl in front of her.

One day it happened that her son and his wife went on a trip to Bakresbar. There the son’s mother was sitting as usual in a line with all of the other beggars along the path to the bathing area. Can a mother ever forget her son? Never. But the son did not recognize his mother. He dropped a coin into her begging dish, and at this moment, his mother called him by his name, the name she had called him when he was a child. He was startled; he knew that no one knew this name but his mother. He was about to stop and say something to her, but his wife would not let him stand there. She pulled on his arm and said, “You don’t have to talk with that old woman,” and she led him away.

Another woman—Billo’s Ma, a Bagdi widow with four married sons—spoke to me bitterly of how her sons had turned from her now that they had families of their own. She lived in a compound with three of her sons and their wives, but she had a small hut of her own where she slept and cooked separately, supporting herself meagerly by making cow dung patties for fuel for wealthier Brahman households. She told me first, with great emotion and at times breaking into tears, of raising her four sons and two daughters all alone after her husband had died. In order to get food and clothing for her children, she had labored every day in wealthy people’s homes and fields, and sold the few ornaments she had brought with her from her parents’ house as a bride. But then, she said with chagrin,

I asked, “You mean your sons give everything to their wives?” Billo’s Ma answered, “Yes. They have their own families and their own work. How will I take anything from them?”My sons all grew up, and I gave all their weddings. All of them have their own families, and now to whose do I belong? Now whose am I (ei bār āmi kothākār ke)? I am no longer anyone (ār to āmi keu nay). Now one son is saying, “I came from a hole in the ground.” Another is saying, “I fell from the sky.” Another is saying, “I came from God.” And yet another is saying, “My hands and feet came on their own; I grew up on my own.” Who am I now? I’m speaking the truth. What kind of thing is a mother?…

Listen. I have four sons. If they had all lived in one place, that would have been good, wouldn’t it? If they would all come to eat [together]. If they would take the money they earned, put it into my hand and say, “Ma, will you handle this for me?” Then my heart would have been happy. But now, whatever your brothers [i.e., her sons] bring home—who do they give it to? their mother? or their wives? Huh?

In these two stories, a mother yearns for intimacy with her son or sons, but her sons abandon and forget her. They present a sequence of events familiar in others I heard told by and about old mothers: A mother sacrifices everything for her son, but ultimately there is a failure of reciprocity. When the son grows up, he gives nothing back to her. The son turns from his mother to his wife, and in the end he forgets her altogether. Being abandoned and forgotten by her son in this way, the mother is stripped not only of material support but also of her identity as a mother. She is left with no option other than to become one in an indistinguishable line of old beggars, literally or metaphorically. Moreover, the blame in such stories usually falls more on the son’s wife than on the son. For although the son abandons and forgets his mother, it is often the son’s wife who plays the active role in leading him away.

The theme of the immense self-sacrifice of women as mothers, coupled with the failure of reciprocity and betrayal by sons, surfaces powerfully as well in a modern Bengali short story called “Stanadayini” (“Breast-Giver”) by Mahasweta Devi (1988). It centers on Jashoda, a poor rural Brahman woman, mother of twenty and nursemaid of thirty more, who spends her life pouring out her body’s milk to nourish her own and her master’s children. But in the end she is abandoned by them all. When she becomes old and can no longer reproduce or nurse, her almost fifty sons all forget her, and her breasts—the distinguishing organ of the woman as mother—become the site of ugly, festering, cancerous sores. Jashoda cries, “Must I finally sit by the roadside with a tin cup?” (p. 234), and then moans spiritlessly, “If you suckle you’re a mother, all lies! Nepal and Gopal [two of her sons] don’t look at me, and the Master’s boys don’t spare a peek to ask how I’m doing.” We are told, “The sores on her breast kept mocking her with a hundred mouths, a hundred eyes” (p. 236). In the end, Jashoda dies alone and without identity, save a tag marking her as “Hindu female,” and she is cremated by an untouchable.

The author views the narrative as a parable of India—seen as mother-by-hire—after decolonization. If nothing is given back to India as mother, then she like Jashoda will die of a consuming cancer (Spivak 1988:244). But I also hear in this story of the breast-giver the voices of older mothers in Bengal, who lament in their own oral tales: how fickle and short-lived are the joys of motherhood! how women as mothers give of themselves their whole lives and receive nothing in return!

We must remember, however, that most older women in Mangaldihi, even those who told stories of beggared and forgotten mothers, were not forgotten or neglected (at least in any blatant way) by their sons and sons’ wives. The image of the mother as beggar works more here as a metaphor conveying a loss of love. Mothers will always love and give to their children more than they are loved and given to in return. Women as wives and mothers give all of their lives, never receiving as much as they have given.

Fathers and Sons

(The problem of a son who is more loyal to his wife than to his father)

The Bengali people I knew did not generally perceive fathers to be widely threatened by neglect in old age. Only a few older men complained to me of inadequate treatment by their children, compared to the countless mothers and mothers-in-law I heard. Furthermore, the two homes for the aged in Calcutta called Navanir (New Nest)—in 1990, the only such homes in Calcutta for non-Christians—were filled with women. Of their 120 residents in 1990, only 7 were men. The residents of the institutions as well as the directors told me that there is no great need for old age homes for men in West Bengal, for most old men are taken care of by their families within their own households.

One of the reasons for this disparity is that most men retain at least nominal control over a household’s property and money until they die. By contrast, women in Bengal rarely own or control property in their own right, although some do inherit property from their fathers, especially if their fathers had no sons. Some, too, have influence over their husbands’ property while their husbands are alive. But even though Bengal has laws requiring that widows inherit a portion of their husbands’ property, virtually no one, in Mangaldihi at least, follows them. Older widows almost uniformly turn over any property (either by verbal agreement or legal transfer) to their sons when their husbands die, if their husbands have not already done so directly. In 1990, out of a total of 335 households in Mangaldihi, only 17 were considered to be headed by women (that is, with women in control of the household property). These included eleven Bagdi, two Santal, two Muslim, one Kulu, and one Muci household (note the total absence of high-caste Hindu households), all of which were headed by widows, most of whom either had no sons or whose sons were not yet grown and married.[4]

Many villagers told me, with some regret and cynicism, that only those who have their own financial resources can expect good treatment in old age;[5] by this logic, more men can be expected to be treated well than women. Possession of property, like the capacity to bless, can be used as a form of leverage; the holder can promise a future inheritance to those who serve him well in old age. Older people with property may also contribute economic resources to the household funds to help defray the cost of caring for them.

Furthermore, men much less often than women are left without a spouse or descendants to perform the actual labor of providing care in old age. Because men are usually several years older than their wives, the majority of Bengali women outlive their husbands to become widows; most men live through their old age still married. Additionally, if a man’s first wife dies at a young age or is barren he may easily remarry in the hopes of producing sons, but the majority of Bengali women (especially if upper caste), once married, never again remarry, even if their husbands die or abandon them childless (see chapter 7).

And the village men with whom I spoke seemed to view the father-son bond as uniquely enduring and almost sacred. According to dominant patrilineal discourse in Mangaldihi, father and son are both central, structural parts of the same continuing lineage or baṃśa (literally, “bamboo”). Like bamboo, which is a series of continuously linked and growing nodes, the baṃśa was regarded as a continuing succession of linked fathers, sons, and wives. A baṃśa includes the male line of descendants from a common “seed” ancestor (bīj-puruṣ), together with their inmarrying wives and unmarried daughters.[6] Women thus come and go to and from this line, but fathers and sons extend it.

The bond between fathers and sons also lasts after death, as fathers (and then later their sons) are transformed into ancestors and nourished by sons and sons’ sons. Women, in contrast, become enduring ancestors not in their own right, but only as parts of their husbands (see chapter 5). Thus by supporting and remembering particularly fathers, as old men and then as ancestors (pitṛ, literally “father”), sons sustain their own selves, for both fathers and sons make up the same baṃśa. All of these factors—a man’s greater chances of having control over property, a living wife, sons, and a lasting place in the family line—contributed to local perceptions that older men tend to be served and remembered by their sons, both in old age and after death.

To be sure, there are exceptions: fathers and sons may quarrel and break their ties; sons may cease to feed their fathers rice. Sometimes these ruptures and omitted transactions are caused by poverty. In several households in Mangaldihi, sons may have wished to feed their aged fathers but simply lacked the resources to do so. Rabilal, a beggar of the Muci (leatherworking) caste, was one such neglected father. He himself had become too old and blind to work; his wife struggled in the fields as a day laborer to earn a meager bit of money for both of them, but it was usually not enough. Rabilal would moan, “Even now that I am old, my sons don’t feed me rice,” and he wandered through the village every day begging for rice and leftovers from cooked meals.

I also witnessed a few serious fights in Mangaldihi households between fathers and sons, though unlike frays between mothers-in-law and bous, these were not regarded as everyday occurrences. Discord most commonly arose over money and sons’ wives. The most serious father-son altercation that took place while I was in Mangaldihi turned into a major village event because of its unusual severity. People dropped their work, crowded around to watch, and talked about it for days afterward.

The fight took place in a Brahman household in a neighborhood bordering the one I lived in. One morning the household’s only bou, a woman I will call Purnima, was cooking in a room with a tin roof. Her father-in-law, Satyabrata Chatterjee, came into the room and complained that the smoke from the cooking fire was ruining the roof. Purnima and her father-in-law began to argue angrily, and Purnima became so enraged that she jumped up and struck her father-in-law on the head with the blunt end of a large iron kitchen knife. Her father-in-law began to beat her. At this point, Purnima’s husband, Benu, stepped in to defend his wife; he repeatedly hit his father with a wooden pole, and the old man’s head was soon bleeding heavily.

From where I was standing, on a neighbor’s roof, I could hear what sounded like the thudding sounds of flesh being beaten, along with terrible shouting. Several other women were watching with me on the roof, but most of the neighborhood’s young men and children had rushed up to the household where the fight was taking place. My young work girl, Beli, ran back to report excitedly to us that the son, Benu, had cracked his father’s head open, and that the father would most certainly die; but we found out shortly afterward that the man had suffered only a few, relatively minor, cuts on his head. Finally, after the father’s youngest son, Bapi, had jumped in to defend his father and beat his older brother’s wife, neighbors pulled the family apart, and the eldest son Benu fled with his wife to a neighboring relative’s house.

Almost immediately, representative men from all of the neighborhood households (most of whom were from the same bhāiyat, or male lineage group) gathered together on the veranda of another house to discuss what should be done with Purnima and her husband. This sort of gathering periodically occurred in Mangaldihi when family or neighborhood problems arose. I listened from the sidelines with several other women, including Purnima herself, who was still distraught and sweating profusely from her exertions. I soon learned that Purnima had never gotten along with her parents-in-law, and particularly her father-in-law, during the ten years of her marriage. Recently things had grown even worse. Her father-in-law had taken out a loan of three thousand rupees (about one hundred dollars) from the bank and he had asked his son Benu to co-sign the loan with him. But the father had not been able to make the loan payments, so recently the bank had been after Benu for the money. Benu himself was without a job and had no income of his own, save the pittance he earned from folding pieces of newspaper into small paper sacks to be used as grocery bags at local stores. This arrangement between Benu and his father thus in itself constituted an inappropriate reversal of father-son relations: even though the father was still the recognized head of the household (kartā), he was seeking to secure money from his still unemployed and unpropertied son.

So the burden had fallen on Benu’s wife Purnima to get money from her own father to help support them, and to pay back the loan. In this way, daughters-in-law in the region often continued to act as conduits between families, as they drew on wealth from their fathers’ homes to bring to their fathers-in-law. But her position angered and embarrassed Purnima, who suffered an unending stream of insults about her in-laws from her father’s family. Tensions between the daughter-in-law and the rest of her in-laws (aside from her husband, who was very devoted to her) had therefore heightened considerably.

The men who gathered primarily blamed the “troublemaking” (badmāiś) bou, Purnima, for the conflict, and several (including her father-in-law) suggested that she no longer be allowed to live in the village. Others proposed a more moderate course of action, which finally prevailed: the young couple, with their one son, would separate completely from the father-in-law’s household. Several of the neighborhood men went over to the family’s house and removed all of Benu and Purnima’s things. They put the couple’s possessions in a small, one-room hut adjoining the main house and rummaged up a lock for the new place. They then told the members of the separate households to stay away from each other.

And so the conflict was settled, but not without causing a household to break up and providing days of discussion. Although the village people did insist that the father, Satyabrata, shared in the blame or fault (doṣ) for the fight, they mostly condemned Purnima, calling her a “troublemaker” by nature. They would say, “Isn’t it horrible that a bou could hit her own śvaśur (father-in-law)? that she could cause her husband to hit his own father on the head? Chi! Chi! This is a great sin (mahāpāp)!” Purnima’s husband Benu generally was found to be largely innocent, a naive and simple (saral) type caught up in a mess between his wife and father; villagers felt compassion and tenderness (māyā) for him. It is very sad to see a father and son become separate (pṛthak), they said, over a wife.

Rabindranath Tagore’s “Sampatti-Samarpaṇ” (“The Surrendering of Wealth”; 1926:48–54) also deals with the theme of tensions that rupture the ties between fathers and sons. The story, set in late-nineteenth-century rural Bengal, portrays a son who abandons his father over a disagreement about his wife. The father lives with his son, boumā, and grandson. The father is old, but he maintains a firm position as head of the household and manages all of the household funds with a miserly strictness. One day his boumā becomes very ill, and the son tries to persuade his father to spend the money to take her to an allopathic doctor. But the father insists that such expenses are not necessary, and he instead brings a traditional Ayurvedic doctor, or kabirāj, with inexpensive herbal medicines to heal her. After this treatment, the wife dies. The son, deeply pained at the loss, blames his father: he leaves, taking his only son with him.

The villagers who watch these events unfold provide a running commentary. As with similar dramatic family events in Mangaldihi, all the entertaining commotion gives the villagers some pleasure; but after the younger man leaves, they sympathize with the abandoned father about the “sorrow of separating from a son” (putrabicched dukha). They cluck their tongues with amazement and disapproval that the son could have valued his relationship with his wife more than that with his father. The villagers exclaim: “A son taking leave of his father over such a trivial thing like a wife! This could only happen in these [i.e., modern] times.” They add: “If one wife dies, another wife can be collected before long. But if a father goes, no matter how much one tears out one’s hair, another father can never be obtained” (Tagore 1926:49). The story’s plot is quite complicated, but in essence things go from bad to worse. The grandfather, who spends a lonely old age worrying about the destruction of his baṃśa (family line), becomes quite deranged, and his only grandson is killed. At the end, only the single son is left alive; the baṃśa is threatened with extinction.

By his tone, Tagore implies that the grandfather is largely to blame for the disintegration of his family: he is stingy and insists on tightly controlling his money, even when his son is grown and has desires and a family of his own. The story touches also on the effects of global change, here represented by the spread of allopathic medicine, on local intergenerational relations. The son wishes to “modernize” in order to save his wife, while his father clings, perhaps unwisely, to more traditional and less costly ways. But from the villagers’ perspective, the son, not the father, is responsible for the rupture. How could a son value his wife more than the bond with his father? A rupture in the father-son bond leads not only to the disintegration of the immediate household but to the end of the whole lineage—and thus denies the enduring meaning of, and reason for, the father-son bond.

Mothers and Married Daughters

(The problem of sending one’s own away to become “other”)

A daughter has a more fragile relationship with her aging parents than does a son, for a daughter’s bonds with her parents are in effect broken when she is given away in marriage. I often heard mothers say of their daughters: “You just keep them with you for a few days and then give them away to an other’s house.” The bond is precious, but fleeting and ephemeral.

Precisely because married daughters become “other” in this way, most Bengalis state that parents cannot be cared for by daughters when they grow old, even if they have no sons. Several sonless older women I encountered insisted that they would rather live alone, or even in an old age home in Calcutta, than with a married daughter. One woman, Pratima-masi (Auntie Pratima), a resident of a Calcutta old age home, explained her reasoning:

Masi:So a boumā, who is not one’s belly’s issue but comes into one’s own house and becomes part of one’s own baṃśa, becomes closer in many ways than a daughter, who is a mother’s own belly’s issue but marries away to become part of an unrelated person’s household and lineage.I have no sons, only three daughters. If I did have a son, I would have certainly lived with him. But we Bengalis hate very much to live with daughters.

SL:Why?

Masi:Because when we give our daughter’s marriage she becomes other (par). I have given my daughter into an other’s hand (meye to parer hāte diechi). My son-in-law is not my belly’s issue (peṭer santān nae).

SL:But a daughter-in-law? She is not your belly’s issue either, is she? [I was seeking to understand why elders felt so much more comfortable living with their sons’ wives than with their married daughters.]

Masi:No, that’s different. Even if my boumā (daughter-in-law) hit me with a cane, that would be all right. I could still live with her. Because she is my son’s wife. But living with a jāmāi (daughter’s husband), that’s impossible. We Bengalis hate it. If there’s a son, then the baṃśa (family line) remains, and the boumā becomes part of the baṃśa. But a daughter’s baṃśa is different than ours. We don’t hold a daughter’s baṃśa (meyer baṃśa āmrā to dhari na).

Parents also incur a considerable loss of respect (asammān) if they live with or are cared for by a married daughter. Many I spoke with stressed that Bengalis believe that married daughters and sons-in-law should be given to and not taken from. Another woman in an old age home explained: “It’s not right to live with daughters. Bengalis feel a disrespect (asammān) if they live with their daughters. They live with their sons. But I have no son.…I visit my daughter’s house sometimes, but I never stay longer than two or three days. Even if they tell me to stay I don’t. Because it’s my daughter’s and jāmāi’s house. And among Bengalis we must give to daughters and jāmāis, but we can’t take from them. In taking from them a disrespect happens.”

The proper direction of the flow of gifts is from a woman’s natal to her marital household (Fruzzetti 1982:60). The major gift that instigates this pattern is the father’s offering of his daughter—kanyādān, or “gift of a virgin”—to his son-in-law (jāmā̃i) at marriage. Throughout the daughter’s married lifetime, dowry and other gifts are expected to flow predominantly from her natal to her marital home. Thus in Mangaldihi, Purnima, a daughter-in-law, received money from her father’s home to give to her father-in-law (though not, as we saw, without considerable resistance on her own and on her natal family’s part because the demand was seen as excessive). Husbands and wife-takers are regarded as superior to wives and wife-givers; the proper flow of gifts upward reflects this hierarchical ordering. A married daughter’s parents, then, incur a significant loss of respect if they cannot continue to make occasional gifts to their married daughter’s household, or if they are required to ask their daughter’s husband for monetary assistance or other goods. Presumably, this concern with “respect” (sammān) was even more important to some than having a family to live with, for many of the women in the Navanir old age home had daughters but no sons.

Finally, many sonless older women explained that if they went to live in their married daughters’ homes, there would be a considerable amount of trouble, discomfort, and uneasiness, especially if the daughter’s own parents-in-law were living there. Arguing and overcrowding would result. And the daughter’s mother would have no power (śakti) or real place in the household. She would be simply “dependent” (parādhīn): that is, someone who is supported without giving anything in return. I rarely heard this term applied to a mother in her son’s home, for a mother’s earlier years of giving to the household and its junior members were taken into account, ensuring her rightful place when she no longer worked in the household.

Nonetheless, some sonless mothers who had no other options did end up seeking to live with their married daughters. Two elderly sonless women came to Mangaldihi while I was there. One was a Brahman woman whom most of the village’s young women called Bukun’s Didima (Bukun’s maternal grandmother), after her daughter’s daughter, Bukun. One winter day I noticed a thin and stooped woman dressed in a plain white widow’s sari descend from the noon bus: this was Bukun’s Didima. She made it to their home and announced that her health and eyesight had deteriorated so much that she could no longer live alone. She came with a few meager possessions and the considerable sum of six thousand rupees, all of her savings, which she bequeathed to her daughter’s household to offset the expense of feeding and caring for her until she died.

Several months later, though, after she had returned from a visit to her other married daughter’s home, Bukun’s Didima requested that her first daughter return the six thousand rupees. She had decided that she could no longer tolerate living in her daughters’ homes and wanted to try again to live alone in her own house. But by that point, her daughter’s household was decidedly not eager to return the money. For the rest of the afternoon, Bukun’s Didima argued and pleaded with them, especially with her three granddaughters. The granddaughters shouted at her, “How dare you come now to take away your money?! You came when you were sick, and we served you, fed you, rubbed oil on your body, and made you well. We said you could stay here with us for the rest of your life. But now that you’re well, you want to take your money back and go. What kind of gratitude is that? That’s not right! You’re a small, low person (choṭolok)!” They called her all sorts of derogatory names (most of which I could not understand) and spitefully mimicked her when she cried, “I’m going to die, I’m going to die right here!” They said they would not feed her any rice until she changed her mind, and finally she left, wailing, to eat at a neighbor’s house. Many people crowded around to watch. They said that this is what happens when an old woman goes to live in her daughter’s home.

Several months later, Bukun’s grandmother was still with her married daughter in Mangaldihi. One sultry summer afternoon, she spoke to me of her predicament in low tones: “This [my daughter’s house] is an other’s house (parer ghar). When I gave my daughter’s marriage she became other (par). That’s why I don’t like it here.…But first I’m going to take my six thousand rupees and then only will I go. They’ve eaten up my six thousand rupees and they aren’t giving it back. But I’m going to take it back.” When I left Mangaldihi, Bukun’s Didima was still there with her daughter. They argued continually, and the older woman preferred to spend most of her time in neighboring households.

Another woman, called by most villagers “Khudi Thakrun’s daughter” (after her mother, whom she continued to visit frequently), was also compelled to live with her married daughter in her old age. She had been widowed much earlier in her life when she was nineteen and her only daughter was a toddler. Like Bukun’s grandmother, Khudi Thakrun’s daughter had felt obligated to give her married daughter and son-in-law her wealth in exchange for being cared for in old age. But she lamented that ever since she had transferred her property to them, they no longer cared for her as they once did. She came to my home one afternoon to tell me the tale of her suffering:

Old women feel that they are expected to “pay” their daughters and jāmāis, who are “other” (par) rather than “own” (nijer) people, for care and service provided in old age. Such a property-based relationship is not one of ease, and it is apt to wither once the elder’s property is gone.I have given everything that I had to my daughter. Now I have nothing at all. I am now sitting dressed as a beggar (bhikhāri). I have nothing at all. I’ve given everything to my daughter and jāmāi. I had a house in my name, and even that I gave to them. Everything.…And now I live there [with my daughter] and eat there. I have no more power (śakti), no more strength (kshamatā), no more material wealth (artha), no more money. I have become old (buṛo); I can’t do anything. So now I have to sit and be fed. But now they no longer look after me like they used to.…Three days later [after I gave them my property] and they no longer love me like they did. I gave everything to them and now they don’t really care about what’s left. I’ve become old, without strength; I can’t do anything any longer, and can’t give anything more. And they no longer look after me. This is my life of sadness.

Installing a ghar jāmāi, or “house son-in-law,” is one final way that some parents of daughters plan to be cared for in their old age: they acquire an inmarrying son-in-law to settle with their daughter in their own home. The son-in-law and daughter both receive a kind of “payment” for doing this, for they stand to inherit the parents’ home and most or all of their property when they die (and they are also able to live on the property until then). A ghar jāmāi is generally from a poor family, or a younger son in a family of several sons—someone who would have had difficulty supporting a wife and family on his own. He agrees to move into his wife’s household in exchange for the property he will live on and inherit.

This arrangement was generally considered to be difficult for all concerned, and particularly embarrassing for the jāmāi (and, to a lesser extent, for the married daughter). Here the jāmāi becomes in some ways like a wife: he shifts from house to house and is contained in the house of another, rather than practicing the more prestigious male pattern of developing and refining himself in a continuous, straight line, in the home and on the land of his fathers’ fathers (see also Sax 1991:82–83). Daughters were sometimes embarrassed to marry such a feminine-seeming man. They also expressed reluctance to miss the opportunity of being honored as a new bride in a new home, intimating that the new bou status, however difficult to endure, was valued as well. Many parents of only daughters therefore did not choose this arrangement. One mother of three daughters and no sons, Subra-di, told me firmly: “We don’t want to place a ghar jāmāi in our house. Our daughters wouldn’t like it, and neither would we. It would make us all feel uneasy (aśānti). We will just live alone.”

Thus as daughters become “other” (par) to their parents when they are married, parents cannot count on them for care in old age. Yet a mother’s bonds with sons and their wives are not as inescapable and enduring as those without sons might imagine. I heard many old mothers of sons say the same things about the “otherness” of their bous, their sons’ wives, that mothers of daughters say of their married daughters. One woman explained why she did not wish to live with her son and his wife: “My son’s wife is actually not my own child. She’s a daughter of another house (parer gharer meye).” And another woman, a Calcutta old age home resident, told me regretfully that she had come to the home because she had only sons and no daughters: “I have no daughter who could look after me. Daughters are more ‘loving’ [she used the English word] than sons.”

All old people, both those with sons and those with daughters, must grapple with depending on juniors—women—who are in many ways “other” to them. It is necessary to the family cycle and continuity that parents bring daughters-in-law into their homes for their sons and send their own daughters out to the homes of others. But in so doing they cause their sons and daughters to become enmeshed in bonds that will, to some degree, inevitably distance them from their peripheralized parents. Those I knew often blamed this distancing for the neglect and unreciprocated houseflows afflicting older people.

| • | • | • |

The Degenerate Ways of Modern Society

The kinds of conflicts and problems Bengalis perceived to be built into family relations cannot be understood without considering as well Bengali constructions of modernity. Dominant discourses in the 1980s and 1990s—in Mangaldihi and Calcutta, and in Indian newspapers, magazines, and gerontological texts—assert that social problems have burgeoned in modern times. In these discussions, images of a bad old age are often invoked as paradigmatic signs of a disintegrating “modern” (ādhunik) society. Lawrence Cohen (1998) offers a penetrating, detailed analysis of discourses of old age, senility, and modernity in Indian gerontological literature and among the urban middle class in Varanasi and other north Indian cities. After looking briefly at some of the same cosmopolitan discourses (encountered mainly during my many visits to Calcutta), I will relate these to Mangaldihi perspectives on modernity and the modern afflictions of old age.

Since the early 1980s, a profusion of literature on aging has appeared in Indian gerontological and sociological texts, journal articles, and popular magazines.[7] Most of it is organized around the strikingly uniform theme of a looming “problem of aging,” framed as an increasing number of old people and a decreasing social desire to take care of them. The cover story of the 30 September 1991 issue of India Today exemplifies this trend. It is titled “The Greying of India,” and its cover blurb reads: “With life expectancy going up, the number of people above 60 has risen past 50 million. Coupled with this, rapid urbanization is disrupting traditional relationships, leaving Indian society struggling to cope with a new dimension of alienation and despair” (M. Jain and Menon 1991).

Sarita Ravindranath’s story “ Sans Everything…But Not Sans Rights” (Statesmen, 1 February 1997) covers the recent passing of the Himachal Pradesh Maintenance of Parents and Dependents Bill, which requires children in the state of Himachal Pradesh to provide for their aged parents. This bill was necessary, Ravindranath and local public officials contend, because of the sharp decline in family bonds in today’s India. “[A]ged and infirm parents are now left beggared and destitute on the scrap heap of society. It has become necessary to provide compassionate and speedy remedy to alleviate their sufferings,” the Himachal Pradesh minister, Vidya Dhar, states in the bill’s preface (qtd. in Ravindranath 1997). But Chittatosh Mukherjee (retired chief justice and chairman of the state Human Rights Commission) comments that legislation can only do so much to remedy a family’s and society’s ills. “A man might get enough money to sustain himself, but where will he go for love and affection?” he asks. “As long as there were strong family bonds, there was no need for written law to dictate that you have to care for your parents.” The article concludes:

Whatever its merits or defects, it is unlikely that the joint family system, with its insistence on caring for the elderly, will make a comeback to Indian society. As more and more people leave home in search of a better life, the neglected ones are parents, who most often invest their life savings in their child’s education and growth. And while it is impractical to tie children to their parents’ strings for life, it is as important to ensure the rights of the elderly to lead a dignified life.…Only the law…can reach out and help bent, sad people stand up straight with pride.

One of the primary forces of change and modern affliction in these narratives is Westernization. The “joint family,” a multigenerational household in which elders make up an intrinsic part, is often described as something “uniquely Indian” or “characteristic of Indian culture.” For example, in his preface (1975:ii) to J. D. Pathak’s Inquiry into Disorders of the Old, S. P. Jain professes: “The old were well looked after in the joint family system, so characteristic of the Indian Culture.” Madhu Jain and Ramesh Menon (1991:26) declare that “Age was synonymous with wisdom, values and a host of things that made Indian society so unique.” In contrast, the “West” is associated with old age homes, negative images of aging, independence (that is, small or nonexistent families), and individualism. In fact, the first old age homes in India were products of colonial penetration, constructed by Christian groups such as the Little Sisters of the Poor from the late nineteenth century onward and inhabited (until very recently) almost exclusively by Anglo-Indians. The cover story of the 7 January 1983 issue of Femina—“Old Age: Are We Heading the Way of the West?”—focuses on the rapid growth of India’s old age homes, negative media images of the elderly, and modern youth’s reluctance to care for the aged. British colonial rule, comments Ashis Nandy (1988:16–17), also played a decisive role in “delegitimizing” old age in India by importing Europe’s “modern” ideology, which casts the adult male as the perfect, socially productive, physically fit human being and the elderly (as well as the effeminate) as relatively socially inconsequential.[8]

Urbanization also figures in urban middle-class narratives of the problems of aging in contemporary society. Indian gerontological literature blames what it calls the breakup of the joint family at least as much on the growth of India’s cities, bolstered by an increasing stream of new inhabitants from the countryside, as on the forces of colonialism and Westernization. The argument goes that urban houses (and thus families) tend to be smaller than those in villages, and their walls more divisive and isolating; they are less likely to include old people, who are commonly left behind on village lands. The chaos and separations brought about with the emergence of the postcolonial order in South Asia, and the partition of India from Pakistan and Bangladesh, are featured in these modernity narratives as well. People I knew—especially those in the newer neighborhoods of southern Calcutta, which are replete with middle-class refugees from what was formerly East Pakistan, now Bangladesh—often spoke poignantly of postindependence and postpartition as overly independent (svādhīn) and maya-reduced times. People torn away from their ancestral lands and homes live now in compact urban apartments, making multigenerational family relationships ever harder to sustain.

People in Mangaldihi also talked continually about how things had gone awry in current times: families were breaking up, old people were being left alone, and (partly as a consequence, partly as a cause) the society (samāj) as a whole was deteriorating. Cohen finds that (unlike his urban middle-class informants) those living in the low-caste Nagwa slum of Varanasi where he did comparative fieldwork did not invoke the modern or the West to ground a rhetoric of the weaknesses of old age or the collapse of families. Rather, the afflictions of old age were blamed on poverty, the caste order, oldness itself, and frictions between brothers (which broke families into small units). Bad families were not spoken of as a recent or unusual phenomenon (1988:223–48). In Mangaldihi, however, there was a pervasive sense that the “modern” (ādhunik) was at the root of many social ills. This sentiment, though expressed across caste and class lines, was most pronounced in upper-caste neighborhoods.

The three main villains of modern affliction in Mangaldihi were Westernization, urbanization, and women. Many of the less literate in Mangaldihi were not quite certain where the “West” (or bilāt—England, America, foreign places) was located or just what it entailed. People asked, Was bilāt—or my country, America—near Darjeeling? Delhi? Was Hindi spoken there? Others were acutely interested in and informed about India’s longtime engagement with the West via British colonialism, the increasing globalization of the media and the national economy, and the out-migration of Indians to places such as the United States. A good proportion of Mangaldihi’s Brahman men commuted to nearby cities for work, read English language newspapers daily, and watched international television programs in their or their neighbors’ homes. It was in these Brahman neighborhoods that people most often invoked the West, bilāt, or “foreign winds” as a key source of the travails of modernity. Gurusaday Mukherjee commented that popular American television programs and British-style education systems were in part responsible for the failure of young people to respect and fear their elders as they once had. Subal, an older Bagdi man, concurred. He said that the school education of his sons and grandsons had led to a new lack of respect and loss of authority for old people: “The old people’s words are not mixing with the young people’s any more. Now the young people’s intelligence has become very [or ‘too,’ beśi] great.” Some people in Mangaldihi had heard of old age homes in Europe and America, and compared them disparagingly to their ashrams or shelters for dying cows. And they noted with dismay that this system was penetrating their own society. Many Mangaldihi women were fascinated by the tape-recorded interviews I brought back from the two Navanir old age homes in Calcutta; they crowded around my tape recorder to listen to the residents’ stories, then would often analyze these women’s predicaments in terms of the Westernized modern era in which they all were finding themselves.

Some in Mangaldihi also linked the general decline in the quality of village life, and the increasing precariousness of the condition of old people within their families, to urban migration. Large numbers of residents have left the Mangaldihi region over the past several decades—especially the better educated and the higher castes, who can find salaried jobs in the cities. In 1990, about 14 percent (or 243 out of a total population of 1,700) of those whom Mangaldihians themselves considered to be Mangaldihi residents actually lived most of the time away from “home,” returning from the city only periodically to attend major festivals, at harvest times to sell crops that had been cultivated by their sharecroppers, or to visit relatives remaining in the village. Although I knew of no families that abandoned their older members completely, in several cases sons left their parents alone for some years, usually until one spouse died.[9] When that happened, the sons and their families would return to Mangaldihi for the elaborate funeral rituals and, after the funeral was over, take away the surviving parent, often arranging to have him or her shift from house to house among the various sons living in different cities. Such urban migration not only left some old people alone for long intervals but also left houses disturbingly empty. Friends and I would walk down village lanes and see homes boarded up, to be vitalized only once or twice a year by voices and the warmth of cooking fires. People would say, “How great our village used to be! Crowded with people at all times…” They did not like passing by those lonely homes.

Although women do not play much of a role in the largely de-gendered gerontological texts focused on the urban middle class, they figure prominently as agents of change in the rural men’s and women’s narratives I heard. Modern-day daughters-in-law, I was told, are better educated; they go out and get jobs, they are interested in makeup and movies, they desire their independence, and they are not willing to serve their husbands’ parents as daughters-in-law once did. The tellers of such stories are mainly old women (young women, of course, might applaud such changes), who are also portrayed as suffering the most from neglect by young women—and thus women become both the agents and victims of modernity. One middle-aged Mangaldihi woman, Bani, told me: “Our ‘joint families’ are becoming ruined (naṣṭa) and separate (pṛthak), because women have learned how to go out. They are irritated by all the household hassles.” An elderly widowed Kayastha woman similarly spoke of the role young women play in the decline of traditional values: “Back then, saṃsār (family life) was very pure (pabitra). Daughters-in-law kept their saris pulled up over their heads [a sign of modesty and deference to elders], and the young were devoted to and served the old.…In this age,” she went on, “daughters-in-law want their independence. They want to live separately (pṛthak).”

Susan Wadley finds that residents of the village of Karimpur, north India, express similar concerns about new household authority patterns and family separations in modern times, also blaming these in part on the daughter-in-law’s new demands (1994:236). This song was sung by a group of Brahman girls at a wedding, presumably with a degree of irony (p. 238):

Patricia and Roger Jeffery (1996:161–62) hear similar voices: “Daughters-in-law used to be afraid of their mothers-in-law. We used to tremble with fear…These days, it’s the mother-in-law who fears the daughter-in-law.”

Mother-in-law, gone, gone is your rule, The age of the daughter-in-law has come. The mother-in-law spreads a bed, The daughter-in-law lies down. “Mother-in-law, please massage my feet.” The age of the daughter-in-law has come.

These contemporary rural critiques of modernity both recall and provide a revealing contrast with late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Bengali anticolonial nationalist discourses, which were gendered in parallel ways.[10] In those earlier debates, Partha Chatterjee shows, women (and the home, family, religion) were represented as upholding a “traditional,” Indian spiritual inner domain, distinct from an increasingly “Western” material outer world. Nationalists asserted that although European power had relied on superior material culture in subjugating non-European peoples, it could not colonize the inner, essential identity of the East, which must be preserved in the home. He observes: “In the world, imitation of and adaptation to Western norms was a necessity; at home, they were tantamount to annihilation of one’s very identity” (1993:121). But a striking proportion of the literature on Bengali women in the nineteenth century concerned their threatened Westernization. Contemporary writers suggested that the “Westernized woman was fond of useless luxury and cared little for the well-being of the home” (p. 122). Even more damning, “A woman identified as Westernized…would invite the ascription of all that the ‘normal’ woman (mother/sister/wife/daughter) is not—brazen, avaricious, irreligious, sexually promiscuous” (p. 131). In Mangaldihi, remarkably similar discourses, though not as explicitly wrapped up with nationalist and countercolonial sentiments, still formed part of an overall narrative deploring recent changes and yearning for a more “traditional” Bengali past. In this past, women (young women)—as submissive and caring daughters-in-law, mothers, and wives—guaranteed close multigenerational families, the social-moral order, a good old age.

To be sure, we have little or no evidence that the past really was more perfect, harmonious, and filled with joint families, submissive young women, and venerated elders than the present is. In the abundant gerontological and sociological literature on the contemporary “problem” of aging in India, no baseline or longitudinal data have been presented to support the assertions of rampant joint-family decline (see Cohen 1992:132–35; L. Martin 1990:104–10; S. Vatuk 1991:263). In fact, one of the few longitudinal studies of family structure in India that we do have (Kolenda 1987b) shows that contrary to popular belief, the proportion of joint families in the village of Lonikand near Poona, at least, did not dwindle over the years but has increased from 29 percent in 1819 to 45.6 percent in 1967 (Reddy 1988:63). Data from another study of thirteen villages in Bihar (Biswas 1985:246) show that the proportion of men and women aged sixty and over living with sons remained relatively constant between 1960 and 1982, at about 80 percent (L. Martin 1990:107). As suggestive as they may be, neither of these small studies provides conclusive evidence about how the family in India either has or has not changed over time. It is therefore impossible to tell precisely if or how quickly the joint family is declining, or to what extent it ever did exist in the past as the “self-sufficient unit,…centre of universe for the whole family” (Gangrade 1988:27).

In addition, alarmist statements in the media about the increasing numbers of old people in India (and the subsequent inability of families and society to care for them) fail to take into account that most census studies show no dramatic change in the proportion of persons sixty and over in the Indian population, because fertility remains high (Cohen 1992:133; S. Vatuk 1991:264). Based on numbers alone, we cannot easily predict that there will be ever more old people in India with ever fewer young people available to care for them.

Yet despite their apparent lack of grounding in fact, such narratives of aging and modernity are pervasive and widely felt as persuasive. Arguably one must consider discourse about the degenerate ways of a modern society in the context of a general devolutionary outlook that permeates the thinking of many in West Bengal, and in India more widely. According to the well-known theory of the four yugas or ages, things get progressively worse rather than better as time passes. When this world first came into being many thousands of years ago, people lived in the Satya Yuga, the age of truth and goodness in which dharma or moral-religious order flourished. But ever since then, the social and material world has gradually deteriorated until, according to my informants, about five thousand years ago we entered the fourth and most degenerate of all ages, the Kali Yuga. In addition to stories about the worsening of family ties and the mistreatment of old people, I constantly heard tales of regret about other deteriorations: mangoes are not as large and sweet, cow’s milk does not flow as abundantly, trees do not provide as much shade, villagers do not share the same fellow feeling, people are no longer trustworthy and honest.

Such narratives of modern decline must also be placed in the historical context of colonialism, nationalism, and postcolonialism in Bengal. Partha Chatterjee scrutinizes Bengali narratives of modern decline and likewise asks: “Why is it the case that for more than a hundred years the foremost proponents of our modernity have been so vocal about the signs of social decline rather than progress?” (1997:203). To answer, he suggests, we must look at the interpenetration of modernity with the history of colonialism. He points out (p. 194) that the word ādhunik, in its modern Bengali sense of “modern,” was not in use in the nineteenth century. The term then employed was nabya (new)—the new that was explicitly linked to Western education and thought, the civilization inaugurated under English rule. Because of the way that the history of Bengali modernity has been intertwined with the history of colonialism, Chatterjee argues, Bengali attitudes toward modernity “cannot but be deeply ambiguous” (p. 204). He proposes that “At the opposite end from ‘these days’ marked by incompleteness and lack of fulfillment, we construct a picture of ‘those days’ when there was beauty, prosperity and a healthy sociability, and which was, above all, our own creation” (p. 210). These narratives of modernity impart a sense of a more true and beautiful, a morally superior, an “own” Indian or Bengali past, at the same time that they frame current social problems (some of which may also have existed long before today) as part of historically specific processes of change in a postcolonial and global era.

I will close this section with two narratives portraying visions of the deterioration of modern society, the changing constitution of persons and social relations, and the concomitant afflictions plaguing old people. The first is the story of a resident of one of the Navanir homes for the aged in Calcutta. This māsimā (or “maternal aunt,” as the home’s residents are called) was a woman who had never married, and whose numerous nephews and nieces born of her ten brothers and sisters refused to care for her. She said that people used to consider pisis, paternal aunts, close relatives but that they now treat pisis as par, “other,” and send them to old age homes. She blamed much of the change in her society on the introduction of Western-style “family planning” or birth control policies, which have reduced the size of families and contributed to a general decline in “family love” (saṃsārik bhālobāsā):

You in your country have “family planning” so there are only one or two children per family. But not us. Now, which system is better? I think our system is better. Because I heard that in your country old people become asahāy (helpless, solitary). But not so in our country, at least not before. The old people lived on their land in the villages. They would do pūjās (religious rituals), read the Gita, Mahabharata, and Ramayana. Their sons would serve them. But now with “family planning,” disaster has come. There’s no binding (bandhan) any more in the family. The sons become educated, get jobs, and take their wives with them to live. Who will look after the old people? That’s why I came here. No one thinks of anyone else any more. I’m still embarrassed to say that I live in a “home.” But what can I do? Who will look after me?…I’m saying that family planning is not good. Our hearts have become small. We used to feel a sense of duty toward our kākās, jeṭhās, ṭhākurdās (uncles and grandfathers). But we don’t even know the names of our relatives any more. One person is building a big house and another is going to an home. Affection and compassion (māyā-dayā) no longer exist like they did.

This woman failed to note the irony in her account: though she had ten brothers and sisters, reflecting a family before “family planning,” she still had no one to care for her in her old age. The culprits in her tale are not her family, however, but modernity and Westernization—penetrating into the inner sanctum of families through government-sponsored birth control programs.

My second example is a song that richly portrays a view of the manifold deteriorations of society in modern times, with particular attention to the disregard of elders and a general disintegration of family life. The song, titled “Modern Society” (“Ādhunik Samāj”), was composed in the 1980s by Ranjit Chitrakar, a paṭuyā singer and scroll painter of Medinipur District, West Bengal. Patuas were previously very popular in Bengal; they traveled from village to village singing narrative songs illustrated by their scrolls, called paṭs, and they sold these scrolls in the markets around Calcutta’s famous Kali temple at Kalighat.[11] Their stories were traditionally drawn from Hindu mythology, but in the late nineteenth century they began also to provide critical and satirical commentary on features of contemporary society, like the newfangled English-educated bābu, or Bengali gentleman—or, as in this tale, the maltreatment of old people, the brazenness of women, and the misguided laws of the government in modern times. I heard and recorded this song in Calcutta in 1989; two of the paṭ illustrations that go with it appear below, on pages 98–99 (figures 5 and 6).

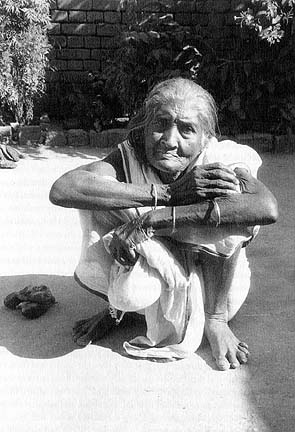

Figure 5. “Father and son's fight”. Paṭat illustration by Ranjit Chitrakar. A son and wife beat up his parents. Note how the senior couple is dressed in white. The daughter-in-law's eyeglasses are a sign of her “modernity”.

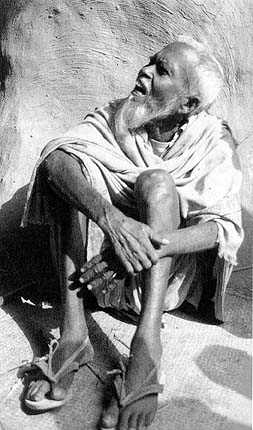

figure 6. “Get out of the road, sir! I'm going to the cinema!”. Paṭat illustration by Ranjit Chitrakar. A “modern” daughter-in-law, wearing slacks, eyeglasses, and a watch, embakrks brazenly on a motor scooter.

This song captures the sense that prevails among rural and urban middle-class Bengalis of the incoherence and degeneration of modern society and the postcolonial state. This degeneration is manifest most starkly in the separations and reversals in intergenerational family relationships: new brides go boldly to their husbands and in-laws with their heads immodestly uncovered; old married women leave their husbands to find new, younger grooms; daughters-in-law treat themselves to luxuries while abandoning their mothers-in-law to torn sheets and unkempt hair; sons steal from their fathers without feeding them rice; and old widows leave their own sons to remarry, while throwing their new mothers-in-law into the road. Here again, women are painted as the primary agents, as well as the primary victims, of the present evils. The government is also held to account for fashioning laws that ostensibly aim to remedy social ills (abolishing caste, permitting widow remarriage) but that in fact result in increased poverty, chaos, and distress.

modern society

Listen, listen everyone carefully. Listen carefully to a song about Kali Yuga. When Kali is spoken of, the head is filled with embarrassment. It is only about people going to the cinema day and night.

When a groom goes to get married he looks for the best-looking bride. If her color is dirty or if she has squinty eyes, Snow-white powder is spread all over her dark body And kājal (eyeliner) is painted on her eyes to make them long and wide.

In the Satya Yuga people got married when they were over thirty. But in the dark Kali Yuga people are marrying before age sixteen. And when brides go to their husbands, they go with their heads uncovered and smiling.[12] They tell their husbands, “I want to go to the cinema with you.”

A twelve-year-old girl runs away with a little boy and has two children, And all the while the government is making laws about taking medicine [i.e., birth control pills]. And then there are old women of sixty years still wearing conch shell bracelets and vermilion,[13] Who leave their old husbands to find themselves a young groom.

Seeing the events of Kali Yuga, everyone’s head spins. The people of Kali Yuga don’t tell the truth, but only lies. The age is afflicted with the sins of going to cinemas. All of the practices of our land have become depraved. .….….….…. . .

The daughter-in-law rubs so many kinds of oil on her hair. But the old mother-in-law is left only to use the kerosene oil from the lamp. The daughter-in-law’s combed hair shines with oil in the mirror, While the old lady’s hair is tangled and bedraggled. The daughter-in-law sleeps on a high bed with three pillows, While the old lady lies on a board with a torn bedsheet. .….….….…. . .

In the Satya Yuga there used to be wealth in the fields, But in the dark Kali age the crops are ruined by sins. Seeing all these events, Laksmi is leaving people’s houses.[14] In the Kali Yuga everyone is eating rice separately out of separate cooking pots. And they steal from their fathers without feeding them rice.

There is a law from the government about abolishing low castes, And there is nothing to eat except wheat and flour.[15] As much as people sell and buy, that much prices are rising. And taxes are increasing steadily in each house.

There came a law from the government that widows can remarry. So now a mother of three or four sons says she must get married. She says, “I won’t live with my sons—what happiness do I have from them?” She dresses up again, with snow-white powder, soap, and shoes, and says, “I will go to my father’s house to look for a new groom.” And if the new husband has a sister or mother, they are just thorns in the road. .…. .

This song is over, but there is a lot more to say. I will write more, older brother, if I live. My name is Ranjit Chitrakar. My address is Medinipur.

| • | • | • |

Three Lives

Though I have discussed consensus and contest in separate chapters, in the real exchanges of everyday life they do not exist in neat isolation. The very people who strove to sustain long-term relations across generations, and who stressed to me the “Bengali-ness” of their family ties (see chapter 2), also experienced distressing intergenerational conflicts and saw the modern postcolonial age as rife with such conflict. The following description of the ambiguities and nuances of the family lives of three elderly people in Mangaldihi provides a fitting conclusion for both aspects of my examination.

Khudi Thakrun

Khudi Thakrun.

Khudi Thakrun was proud to be the oldest or most “increased” (bṛiddha) person in Mangaldihi. Nearing one hundred years old, her face was made of an intricate design of wrinkles, her white hair was cropped short in the style of old widows, and she roamed the village covered sparsely with a man’s white dhoti, with her loose breasts hanging low.[16] She had one of the strongest, most willful characters in the village, which was perhaps intensified by her advanced age. She lived alternately in the separate homes of her three sons and bous, who cared for her attentively. She continued (unusually for someone of her age and sex) to maintain substantial control over her own money and land, and she still lent money and collected interest to increase her wealth, and to buy extra mangoes and sweets to satisfy her palate.