3. What Is “Hellenistic” about Hellenistic Art?

Martin Robertson

A very long time ago I published an article which I called “The Place of Vase-painting in Greek Art,” [1] and when I sent a copy to Sir John Beazley I inscribed it “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” I fear that a lecture with the title I've given this one needs some similar cover. When Peter Green invited me to take part in this symposium and discuss some aspect of Hellenistic art, I was delighted but in a difficulty. It is a field which I find of the very greatest interest, but one in which I have never done detailed research of my own, and I could think of no special theme to offer. So I went for the wide general question, which is indeed a very interesting one, and looks fine as a title with its question mark at the end; but in a lecture with such a title the audience may reasonably expect to be offered something in the way of an answer or answers, and this is where the trouble starts. In her account of life in a labor camp Irina Ratushinskaya writes: “Tanya is reading the journal Literary Questions and I poke fun by asking whether there is, anywhere in the world, a journal called Literary Answers? And, if there are no answers, what is the use of questions?” However, I don't think I quite accept that (nor, perhaps does Irina Ratushinskaya; after all, she was joking). A question can be interesting even when no answer comes up; even when, in the nature of the case, it is unlikely that any answer tentatively put forward would be likely to meet with general acceptance. Certainly today I have no answers, but perhaps talking round the question, in the lecture and in discussion, will not be a total waste of time.

To begin with, what have people said on this question before? Indeed, what have I said on it myself? I might as well start from that; and since in my History[2] I was not primarily aiming to break new ground, what I said there will contain a good deal of communis opinio. Looking at that again, I see that I seem to put a great deal of emphasis on the idea that the change from classical to Hellenistic art was not, like the change from archaic to classical, something which came about within the art, something inaugurated by the artists themselves because of discontent with established idioms and conventions, but almost entirely a reflection of changes external to art itself: change in the structure of the known world and the way it ran, Greek cities now being ruled in the main by kings who also ruled countries and cities inhabited by non-Greeks (and even those cities which maintained independence were inevitably changed by this changed ambience). Of course I make no claim to originality in this view. It is widely held; but I am now not quite so sure of its overriding truth, and I find myself more than a little worried by the way I applied, or rather, if the truth be told, failed to apply this premise to the actual art as we have it. Do the qualities, whatever we may perceive them to be, which distinguish Hellenistic from classical art really reflect in any definable way the enormous change from the classical to the Hellenistic world?

To take first one obvious problem. One would expect the inclusion of oriental peoples, with their own long and sophisticated traditions of art, in kingdoms ruled and partly populated by Greeks (for the purposes of this lecture I count Macedonians as Greek) to lead to some interaction of Greek and oriental in the art of the time. But where does one find this? Well, there is one obvious and obviously significant monument which does show something of the fusion one expects, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus; but that is, awkwardly, a pre-Hellenistic building. Attempts to show that any part of this extraordinary architectural-sculptural complex are of Hellenistic date[3] seem to me, beyond a doubt, altogether mistaken. In any case the non-Greek features are the basic design of the building, with its stepped pyramids and high podium, and the way the sculptures are disposed in relation to the architecture; and these elements are unquestionably original. I regret to observe that in my book I skate round this awkwardness in two ways. First, I put my sketch of the historical background to Hellenistic art at the beginning, not of the chapter called “Hellenistic Art,” but of the one before, slyly entitled “The Second Change: Classical to Hellenistic,” in which I include the Mausoleum; and secondly, I write in that chapter: “The Hellenistic situation was in certain circumstances partly anticipated before the transitional phase in the age of Philip and Alexander.” [4] This sentence is in itself, I think, a fairly obvious truth. What I failed to stress is the fact—I think it is a fact, and surely a rather odd one—that when one gets to the Hellenistic Age proper one finds very little indeed in the way of original creations like the Mausoleum in a mixed Greek-Oriental idiom.

Pollitt, in his great book Art in the Hellenistic Age,[5] is not concerned with the Mausoleum, since it lies outside his period. He does, however, cite a related monument, which to my shame I did not mention: the Hellenistic (perhaps third-century) tomb at Belevi. He refers to its fusion of Greek and oriental elements, which he sees as carrying on a tradition initiated in the funeral car of Alexander, of which we have an elaborate description and which is another and still more deplorable omission from my book. Even these, however, seem to me to bring us back to the same problem. The oriental elements in the tomb at Belevi are all already present in the Mausoleum (the stepped pyramid) or in still earlier Lycian tombs (the rock-cut chamber), so that it could be seen as part of a local tradition in western Asia Minor rather than as reflecting the innovations of Hellenistic rulers; while Alexander's catafalque stands, like the Mausoleum, on the verge of the Hellenistic Age and seems to promise new departures—which it is oddly difficult to find realized in actual fact.

There is one monument, which both Pollitt and I discuss rather marginally (and indeed it is marginal to the Hellenistic world, geographically, historically, and stylistically): the extraordinary tomb on the mountain-top of Nemrud Dagh[6] in eastern Anatolia, overlooking the upper Euphrates, set up for himself by Antiochus I of Commagene, who reigned through the middle decades of the first century B.C. and claimed descent from both Greek and Persian rulers. Pollitt very perceptively writes of this (p. 275): “The Hellenistic ruler cult involved a fusion of Greek thought with oriental religious beliefs, and the hybrid colossi of Nemrud Dagh may be the truest, if not the most sophisticated, embodiment of it.” One might add that it is not only the seated colossi which illustrate this fusion of Greek and oriental idiom in the style, but also the very odd reliefs, which show Antiochus shaking hands with his gods, Herakles (figure 8) and others; and indeed the whole layout of the huge mountain-top tumulus, with its sculptures and inscriptions. Here in any case we really do have a Hellenistic mixture of Greek and oriental in art; but it remains strange that we've had to fare so far and so long to find it.

Fig. 8.Antiochus and Heracles. Relief at Nemrud Dagh, mid–first century B.C. Photograph from a cast in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Pollitt wonders if the Belevi tomb might be taken as suggesting that Seleucid buildings sometimes showed such a mixture. For reasons given earlier I feel doubt in this case, but the idea receives support from the remains of a Greek city uncovered on the extreme eastern verge of the Hellenistic world: Ai Khanum, on the Oxus in Afghanistan. Ancient Bactria, in which Ai Khanum lay, was a province of the originally huge kingdom of Seleucid Syria, but through much of the third and second centuries B.C. it was ruled by a series of independent Macedonian kings. A determination to keep its character essentially Hellenic is evidenced by the inscriptions, one of them a touching document: the sayings of the Greek sages, set up by a citizen who records that he copied them at Delphi. The theater too and the gymnasium, visible signs of the strictly Hellenic cultural institutions of drama and athletics, are purely Greek in design. A big palace, on the other hand, and a quarter of smaller houses seem rather of Persian derivation in plan, yet here too the detail is often Greek: Corinthian columns and pebble mosaics.[7] It is interesting that the wonderful coin-portraits of the Bactrian dynasts are purely Greek in style[8] (see figure 9).

Fig. 9.Antimachus of Bactria. Silver tetradrachm, first quarter of second century B.C. British Museum, London. Photo: Hirmer Verlag.

The most striking failure of Eastern and Greek traditions to mingle in the art of the Hellenistic world is found in Egypt, where the Ptolemies, in Pollitt's words, “were Hellenistic kings in Alexandria and the most recent dynasty of Pharaohs elsewhere in Egypt.” [9] The two cultures remained virtually independent, and the arts followed their own traditions with only the most trivial and superficial borrowings on either side. There is a possible exception in the matter of personal portraiture. It is certainly in the Hellenistic Age that this branch of Greek art reaches its apogee, though no less certainly its beginnings are much earlier (there will be more to say about this). It is also true that a striking realism is found in some Egyptian carved portraits which date from a time long before Greek art came into existence. Further, there are highly “veristic” portrait-heads in hard stones carved by Egyptian sculptors in Ptolemaic times, and some have held that these influenced Roman portraiture of the late Republic.[10] If continuity could be traced between these early and late Egyptian likenesses, one might think that the tradition had had an influence, through Alexandria, on Hellenistic developments. Alternatively, the late Egyptian artists might have been influenced by their Greek neighbors. In any case, some interaction seems possible, but of a strictly limited kind.

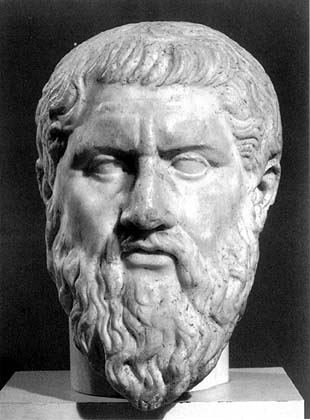

I have in the past argued for the importance of an Eastern connection of a different nature in the case of some early (pre-Hellenistic) examples of realistic portraiture in Greek art: the so-called Mausolus from the mid–fourth century, and certain satrap portraits from the same area in the first half of the century, going back to the coin-heads of Pharnabazus and Tissaphernes from the beginning of the fourth and the later fifth century respectively.[11] In these, I suggested, the realism might reflect the sense of relative freedom which a Greek artist might feel when working for a foreign patron in a milieu outside his own. Pollitt has argued against this,[12] on the grounds of evidence for such realism in Athens in the fourth century: for example, Silanion's Plato, and the notorious particularity recorded of the portrait-statues by Demetrios of Alopeke. The Plato I view a little differently, seeing in it less an interest in the rendering of the sitter's individual features than a skillful adaptation of the traditional satyr-model used for portraits of Socrates, Plato's master, whose persona he used in his writings throughout most of his life.[13] It's true, though, that the copy I chose to illustrate suits this interpretation better than the one Pollitt has! As to Demetrios, I have never questioned his importance, or sought to make the oriental connection the sole source of the idea of realistic portraiture in Greek art. I think our difference here is more one of emphasis than absolute. Happily Pollitt is the respondent to this paper, and will be able to tell us if I am misrepresenting him on this question or elsewhere. He ought of course to be the person giving the lecture. He has worked the Hellenistic field far more deeply and widely than I; but at least he is here to correct my errors, and, I hope, perhaps to offer some better answers to the question in my title than I can provide.

Before leaving this question of Greek portraiture and the East, however, I should say that the suggestion I once made, that the realism of the Ostia Themistocles might perhaps be due in part to its original having possibly been made while the sitter was the Great King's satrap in Magnesia,[14] now seems to me a quite irresponsible extension of the original idea. I do, however, still tend to believe that the Ostia head is a true copy of a contemporary portrait; and the likelihood that such realism was possible then has been strongly reinforced by the discovery of the marvellous bronze head in the wreck off Porticello.[15] Only the most desperate special pleading can make this other than a fifth-century Greek original, and its formidable realism is equally undeniable, though it is possible that it is not a portrait. I find myself much tempted by Professor Ridgway's theory that it does not, as commonly thought, represent a philosopher but rather the good centaur, Chiron.[16] We have diverged some way here from the Hellenistic Age, but not, I hope, unjustifiably. Realistic portraiture is a central Hellenistic interest, and its evolution cannot but be of interest to our inquiry.

Absorption of or modification by oriental influence, then, is a trivial and marginal element in Hellenistic art; and, at least in Egypt, this seems to reflect the general situation, Alexandria being a political and cultural enclave in a virtually unchanged country. How far the social and political isolation of non-Greek from Greek, so marked there, applied also in Seleucid Syria is something which I find I simply do not know.

In religion the position, even in Egypt, seems not so clear-cut; but though Sarapis is apparently of Egyptian origin there is no trace of anything unhellenic in his images. Isis was both more deeply central to Egyptian religion and destined to become more influential in the classical world; but if her cult did affect the tradition of art in the West it was really only under the Roman empire. Greek religion, of course, had taken a great deal from oriental cults long before the Hellenistic Age: Adonis, for instance, and, right at the start, Hesiod's Theogony, at a time when Greek art too was overwhelmingly indebted to the East. That remote, formative period, however, does not offer much of an analogy with the Hellenistic situation.

Religion, however, is one area where perhaps we really can see a change of attitude in the Hellenistic Age that does directly affect art. When, in the early second century, Eumenes II built a library at Pergamon, and placed in it a reduced and modified marble version (figure 10) of Pheidias' chryselephantine Athena in the Parthenon, he surely did not put the statue there simply as an adornment.[17] Athena was the goddess of wisdom as well as arms, the library was attached to her sanctuary, and the image in the library was the goddess its patron, not simply a work of art to embellish a public building. Nevertheless, it does seem to illustrate an approach, to art no less than to religion, very different from that of Pericles and Pheidias and the other citizens of fifth-century Athens for whom the original statue was made. On the religious side, the placing of a major image of a deity in a building designed for a strictly secular purpose is hardly conceivable in archaic or classical Greece. One might even say that there were no purely secular buildings of monumental character before the Hellenistic Age. There were bouleuteria and such, connected with the city government; but the interweaving of religion with civic life was so inextricable that these buildings must be seen as having a strong religious side. This is no less certainly true of theater and stadium. The stoa may perhaps be counted an exception, though very many individual stoas were either placed in sanctuaries or had some direct religious or civic association. A Hellenistic library might be attached to a sanctuary and placed under a deity's protection, but the purpose for which it existed had no religious element. It was, in a new sense, a truly secular building.

Fig. 10.Athena. Marble statue from Pergamon, second century B.C., freely copied from fifth-century original. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. By permission.

On the artistic side, the thing that most sharply distinguishes the Athena in the Pergamene library from her model in the Parthenon is the very fact that she is a copy. This is not, as Pollitt has stressed, a true copy, designed to reproduce the details of the original as closely as possible, as copies made under the Roman empire surely for the most part were. She is an adaptation, a re-creation in the spirit of her own time; but still, this statue is deliberately and carefully modeled on another statue created nearly three hundred years before, a practice which surely can be called truly Hellenistic.

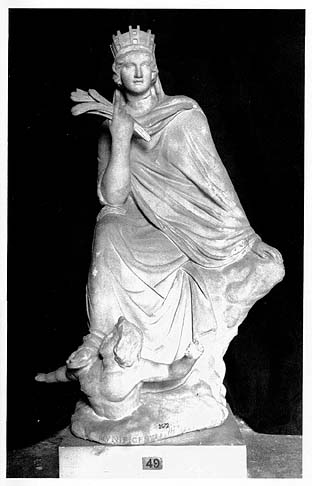

Eumenes' Athena is an example of one kind of statue with a religious affiliation which could hardly have been made before the Hellenistic period: the adaptation of a classical cult-figure (originally designed to be approached down the long darkness of a temple-cella) to a totally different setting and purpose. Another example typifies a quite new type of deity, whose image owes nothing to the tradition of the temple-cella: the Tyche (Fortune) made for the city of Antioch at the beginning of the Hellenistic Age (in the first few years of the third century) and constantly imitated in other cities over the following centuries.[18] This colossal bronze group, of which we can form some idea from descriptions and small versions (see figure 11), was set in the open air and was cunningly designed to present changing and effective views from many angles. Statues of course had been placed in the open air in Greek sanctuaries from the beginning of Greek sculpture, among them colossi, and among those some of bronze—Pheidias' Athena Promachos, for instance, on the Acropolis, and long before that the archaic Apollo at Amyclae. Certainly, however, none of these departed from the traditional principle of design which expected a statue to be looked at mainly from an area in front. In the fourth century Lysippos made several bronze colossi, especially a Herakles and a still larger Zeus at Tarentum; and these, from what we know of other works of the master, are likely to have shown some concern with breaking frontality, with insisting on the third dimension. Lysippos, more than any other sculptor, seems to look forward to the Hellenistic spirit. Eutychides, creator of the Tyche of Antioch, was his pupil, as was Chares of Lindos who, in the Colossus of Rhodes, created a bronze figure even larger than Lysippos' Tarentine Zeus, and representing Helios, one of the old gods. Eutychides, on the other hand, used the new three-dimensionality to invent a new type of image for a new goddess.

Fig. 11.Tyche of Antioch. Small marble statue of Roman imperial date, copied from original of very early third century B.C. Vatican Museum, Rome.

“New goddess” is not quite true. Tyche (Fortune) had been occasionally personified earlier (like almost every other abstraction in Greek thought), and even given at least one statue;[19] but, as Pollitt has emphasized, she takes on an entirely new importance in this period. An obsession with Fortune is the first of five attitudes or states of mind which he sees as particularly characteristic of the Hellenistic Age[20]—a most valuable line of approach. Besides, Eutychides' goddess is not just Fortune in the abstract. With her mural crown and the river-god swimming out from under her feet, she is firmly characterized as the fortune of a city, of a particular city: Antioch on the Orontes. Any city founded in archaic or classical times was put under the protection of one of the old deities. It is surely very interesting that so early as this the experience of the wars between Alexander's successors led Seleucus and his son Antiochus to put their new capital city under the protection of her own Chance; and Seleucus was to learn how fickle a personal Fortune can be.

Since so much in the Hellenistic world depended directly or indirectly on the favor or caprice of kings and on their changing fortunes, and since royal portraits are in the vanguard of developing realism, one might expect that another change in religious practice—the according of divine status to monarchs, after their death or in their lifetime—would have had some visible effect on art; and in one point I think it does. I do not count as an effect on art the giving of divine symbols, like Poseidon's bull horns for Demetrius Poliorcetes, or even the transference to his portrait of a pose associated with Poseidon.[21] These are not changes of artistic character, and in any case they go back to Amon's ram horns for Alexander and the thunderbolt Apelles gave him. Quite different is the enormous eye given to some rulers on their coins, early and most strikingly to Ptolemaic royal couples (see figure 12), later to some Seleucids, and which perhaps appears first in some posthumous portraits of Alexander, notably on the Alexander mosaic.[22] This, surely intended to stress the sitter's superhuman, divine character, runs directly counter to the prevailing trend towards realism. It is not a natural development within the art, but something imposed on the artist—if not by direct command then by the changed atmosphere in the world. Parenthetically, arising from the observation made just now about the inextricability from religion of civic life and government in the city-states, I have sometimes wondered if this may not help to account for the readiness with which Greek citizens acknowledged divinity in Macedonian kings. To those who had always been accustomed to think of city government as bound up with the gods, it was perhaps a comfort, when government was wrested away by an unnaturally powerful mortal, to consider him a god himself. Certainly Hellenistic monarchs shared with the Olympians not only total and irresponsible power, but with it utter unreliability in the handing out of favors or destruction.

Fig. 12.Ptolemy II and Arsinoë II. Gold octadrachm of Ptolemy II (285–246 B.C.). British Museum, London. Hirmer Fotoarchiv.

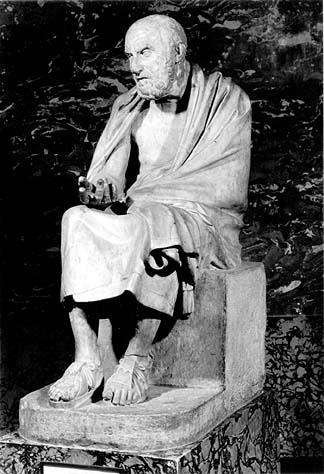

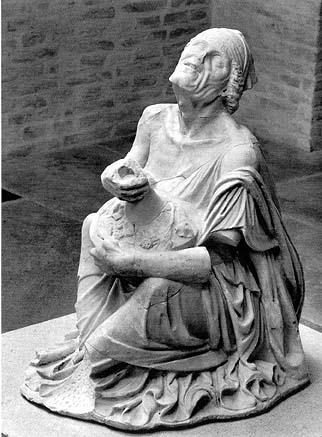

Realistic portraiture is, of course, one of the most important manifestations of art in Hellenistic times and can be taken as one of the things which distinguish Hellenistic art from classical: individualism is another of Pollitt's typically Hellenistic states of mind. The trend, as we've noticed, existed before, but now it is far more widespread, and the aim of making a portrait look like a particular individual is far more general and more marked. Sometimes this aim is extended, in quite a new departure, from the face to the body; early in the period, for instance, the Demosthenes, and later the Chrysippos counting on his fingers[23] (see figure 13). It is true that there are still limitations on its application which do not apply in Roman portraiture. Portraits in Hellenistic as in classical Greece are still always and only of people who have made themselves a name, public figures; or rather, there are exceptions to this rule, but all late and under direct Roman influence, as in Italianized Delos.[24] I myself feel (but this is not I think universally accepted) that even the most personal of Hellenistic portraits keep something of the public as well as the individual character: the ruler, the poet, the philosopher. This is not to say that I suppose we can tell from any Greek portrait the field in which the sitter made his public name. The cautionary tale of the early classical Pindar which so many of us for so long accepted as a possible Pausanias[25] has, I do not doubt, unrecognized parallels in the Hellenistic Age. I do think, though, that every Hellenistic portrait has, together with its individuality, a public character of the kind that, in Roman art, distinguishes imperial and court portraits from the wonderful series of common men and women which has no parallel in Greece.

Fig. 13.Portrait of Chrysippos. Composite cast from marbles of Roman imperial date, copied from original of later third century B.C. Louvre, Paris (marble head, British Museum, London). Photographie Giraudon.

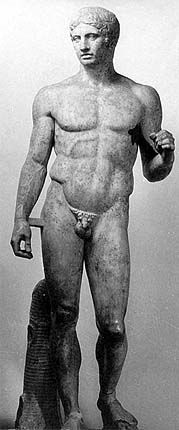

Nevertheless, with all these caveats, it remains evident that portraiture in the Hellenistic Age is something distinctively of its time; but I am not sure how far this really helps to answer the question we set out by asking. It is easy to point to many things in Hellenistic art which were not there in classical: the new approach to the third dimension which we've thought about already; the liking for the grotesque and unideal in the minor arts and even in the major (the Barberini Faun is the supreme example, but there are plenty more); the use of a dramatic setting for a big statue like the Victory of Samothrace (a theatrical mentality is another of Pollitt's Hellenistic states of mind); the exploration of the possibilities in reclining or fallen figures (the sleeping Ariadne, the sleeping Hermaphrodite, the Dying Gaul, the dying and the dead from the smaller Pergamene dedication); and so on.[26] Even in the straightforward single standing figure it is easy to make the same point. The “Hellenistic Ruler” in the Terme (figure 14) may not be a ruler and his date may slide up and down the centuries, but he is surely quintessentially Hellenistic.[27] Compare him to another man with a spear, the classical doryphoros (figure 15). Everything is different: the brutal realism of the features, the exaggerated heaviness of the muscular body, the wonderful spiral of the composition. But all this, like everything else I have been listing, is only to say—what of course we knew already—that Hellenistic art is a clearly distinct phase of Greek art. It is of course itself divisible into phases, wisely defined by Pollitt according to the historical circumstances: the age of the Diadochoi, the age of the Hellenistic kingdoms, the Greco-Roman phase;[28] only it is very difficult to fit the works of art into these phases at all tidily because different styles overlap, run parallel, recur—a variety in itself typically Hellenistic.

Fig. 14.Bronze portrait-statue, variously dated from earlier third to earlier first cen tury B.C. National Museum of the Terme, Rome.

Fig. 15.Youth with a lance. Marble statue of Roman imperial date, copied from fifth-century bronze doryphoros by Polykleitos. Museo Nazionale, Naples. Photo: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Rome. Reprinted by permission.

However, that is by the way. What I am now trying to say is that when we ask “What is ‘Hellenistic’ about Hellenistic art?” we do not simply mean “What distinguishes Hellenistic art from classical?” There is much in the art of the fourth century which is not found in that of the fifth: the exploration of the female nude in sculpture, for instance, or the advances in chiaroscuro in painting. It is a distinct phase; but one would hardly frame the question “What is “fourth-century’ about fourth-century art?” When we ask what is Hellenistic about Hellenistic art we surely mean, What is there about this phase of Greek art that would not have been there if the tremendous change which came over the Greek world in the last third or so of the fourth century had not taken place? If someone had knifed Philip sooner and Macedon had not got imperialist ambitions but had gone on it its old way and allowed the Greek cities to go on in theirs, Greek art would certainly have developed in many ways just as it actually did. In what way could it not have done so? The Hellenistic Ruler, exemplary Hellenistic figure though he be, can be traced back in a smooth sequence to classical sources. Portraiture we have already considered in this sense; the exaggerated musculature is exaggerated on the basic pattern laid down by Polykleitos; and the spiral composition, whatever the actual date of the statue, derives directly from the innovations of the pupils of Lysippos at the beginning of the third century—innovations already hinted at in the work of Lysippos himself, whose own style developed out of the Polykleitan tradition. I see nothing in this statue which needed a change in the world to bring it about.

In what we have already looked at there was one noticeable feature which seemed to stem directly from that change: the exaggerated eye in some royal portraits. Perhaps if we look harder at some of the other things we shall find that they too have something of the same character; for it can hardly be, I think, that the position is the exact opposite of that which I put forward in my History and quoted at the beginning of this paper: that the change from classical to Hellenistic in art was hardly at all a change taking place within the art but almost wholly a reflection of outside changes. Let us try again.

Hoping for light from a different direction I opened the new Hellenistic anthology by Neil Hopkinson,[29] and as epigraph to the introduction I found a verse in which a poet lamented the passing of the good old days when the Muses' meadow was unpolluted and it was possible for a poet to find something to write about; now everything's been said, he complained, the arts have reached their limit, and there's nowhere a man can drive his newly yoked chariot. Oh yes, I thought, that speaks very well for the visual arts too in Hellenistic times. Then I read the first sentence in the introduction, and learned (what you will be shocked that I didn't know, but I am too old for shame) that “these are the gloomy words of Choerilus of Samos, an epic poet writing in the late fifth century B.C. ” I remembered something I once wrote to the effect that up to the classical moment of the Parthenon, of Pheidias, of Polykleitos, the development of Greek art is essentially unified, a single stream; but that after that it begins to break up, different groups of artists developing different styles, so that the columnar Procne from the Acropolis can be contemporary with, and as much a child of her own time as, a wind-blown figure like the Nike of Paeonius[30] or the new goddess in the Getty. Are we really making a mistake, I wondered again, in trying to draw a sharp line in art at the beginning of the Hellenistic Age? The fifty years after Chaeronea saw a total change in the character of the Greek world, but are we really right to look for a corresponding change in Greek art? Art has its own tempo, and should we perhaps do better to make the change from classical to the next phase in Greek art come not at the end of the fourth but at the end of the fifth century? Well, surely, in a word, No; but I still think it is worth asking such questions every now and then, if only to remind ourselves how artificial and distorting our division of art into periods is. We can only study art through the imposition of such a framework, but art when it's happening isn't really like that. Conquest or revolution has a violent and immediate effect on everyday living (though often a lot even of that probably goes on with surprisingly little change), but its effect on art is much less calculable.

Of course particular manifestations of art may be directly and drastically affected. For a classical Athenian, art could include a carved tombstone; for a Hellenistic Athenian, after Demetrius of Phaleron, it couldn't; but that is not what we're talking about. Art develops continuously and changes in complex and subtle ways, sometimes gradual, sometimes sudden. Even the assertion I made just now, that up to the classical moment of Pheidias and Polykleitos Greek art developed in a unified way, is itself a gross simplification. For the archaic period it is more nearly true, and the change from archaic to classical can be made to look like a sharp break by fixing it at the moment of the abandonment of the frontal posture for statues early in the fifth century. But the seeds of change had been there all along, and in certain aspects the change was largely achieved during the second half of the sixth century; while the two sculptors of the Siphnian treasury friezes—one serenely archaic, the other struggling towards the classical—give the lie to the notion of a single development. In the early classical phase all kinds of casting around after possible styles can be seen. We have noticed experiments with realistic facial types, perhaps actual portraiture; and the wonderful new marble charioteer from Motya[31] shows that a severe-style head can be combined with a clinging drapery style derived from that of late archaic korai as well as with the columnar drapery more typical of the time, giving us, before the classical moment, exactly the contrast we noted after it in the Procne and Paeonius' Nike.

Even at the heart of the classical, on the Parthenon itself, the centaur heads of the south metopes are not what one thinks of as classical types; and consider the knotty anatomy of the Poseidon from the west pediment. Suppose that an Attalos or a Eumenes had anticipated Morosini with more success, taking this figure out of the gable and removing it to Pergamon. If the torso had been dug up there, how should we date it? Based on a classical model, no doubt, but perhaps carved around the time of the Great Altar? And yet of course the altar frieze, for all its Parthenonian echoes, is as profoundly Hellenistic as the Parthenon pediments are classical. There is real continuity, but there are also real breaks: between the high classical and its aftermath in the late fifth and fourth centuries, and between fourth-century classical and Hellenistic. What we should like to be able to see is a relation between this second break and the catastrophic historical background.

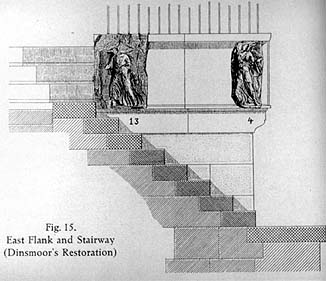

Much of what happened in art in the Hellenistic period is development inherent in the art itself: the overwrought muscles of the Parthenon Poseidon exaggerated in torsos of the altar frieze; the drama of the Scopasian heads from Tegea exaggerated in some giants' heads.[32] One cannot of course say that these developments would inevitably have happened whatever the historical circumstances, but I think one can say that for them simply to take place did not need the special conditions of the Hellenistic world. There is, however, one development on the altar frieze which strikes me as being of a different kind, the thing which does most to justify the transference from another historical epoch of the word baroque. This is the way in which, where the returns of the frieze meet the steps, there is no framing molding, and the huge giants move out of their art-world into ours, pressing hand or knee on the same steps up which the worshipper climbs[33] (see figure 16). In post-Parthenon Athens the balustrade of the little temple of Athena Nike has in the same way a return which runs beside the steps (see figure 17). The last of the under-life-size Victories moves parallel to a visitor reaching the top step, and she too takes a step up; but the tread on which her foot rests is carved in relief within the frame and is on a smaller scale than the steps in the world outside.[34] To thus relate a figure within the representation so directly to the world without was surely a bold innovation in its time; but the frame is kept, the two worlds remain distinct. What the designer of the altar podium has done represents a far profounder break with tradition.

Fig. 16.Slabs of colossal marble relief from podium of Altar of Zeus at Pergamon. Earlier second century B.C. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. By permission.

Fig. 17.Reconstruction of steps and return of carved marble parapet of Temple of Nike on Athenian Acropolis. Late fifth century B.C. From Rhys Carpenter, The Sculpture of the Nike Temple Parapet (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1929), p. 84, fig. 15. Reprinted by permission.

Does this get us any further, though? Can we relate it to anything in the thought or conditions of its special time? Or can this too be classed as a purely artistic phenomenon, the desire of an artist to break the old mold, open new ways? That of course it is, but is it that alone? Let us look back for a moment at the change from archaic to classical. The seeds of the classical were surely there in Greek art throughout its archaic phase, and the changes that mark the difference between the two periods are strictly artistic ones, developing within the arts quite naturally; but one cannot assume that the seeds would have ripened, the drastic changes actually have been made, if historical circumstances had developed differently. Certainly one could not assert that the classical revolution was a result of the liberation of spirit released by the repulse of the Persian invasion, but I believe that there is nevertheless a real relation between the two things. The art of Achaemenid Persia, technically admirable, decorative, formally beautiful, and to my mind dreadfully dull, seems to me to offer an idea of what Greek art might have become if some late archaic artists had not found their way to the decisive break; and I find it easy to think that that is exactly what would have happened if Greece had become a province of the Persian empire. I see the act of those artists in freeing themselves from the age-old conventions as an expression of the same spirit which brought about the realization of Athenian democracy, flowered in literature and philosophy, and willed a successful resistance to Persia.

The problem is so elusive and difficult just because there is no break with the past, in the actual art, at all comparable to the abandonment of archaic conventions; and of course the liberation from the Persian threat was the exact opposite of what befell the Greek cities at the beginning of the Hellenistic Age. Nevertheless, I think one may be able to see that imaginative leap, by which an artist in the second century broke the frame between art and the world, as linked to another kind of liberation of thought which could hardly have come about if the Greek world had not been so violently changed in the way it was. The Olympians in earlier Greek thought inhabit their own world and visit ours unpredictably and for the most part dangerously. Their images dwell in their temples and are approached with due formality and caution. This pattern continues unbroken in formal religion, but from the late fifth century on through the fourth another strand of religious thought becomes more and more important beside it. There is the cult of Asklepios and the healing heroes, in whose shrines you can sleep, and hope that the god or daimon will visit you in person and heal you. The literary tradition about this is reinforced by the number and character of the marble votive reliefs dedicated in gratitude or hope. An equally great wealth of very similar reliefs attests the equal importance of the cults of Pan, the nymphs, and the rivers: gods and daimones who inhabit the countryside with you. These, then, at the popular level; and parallel with these, among intellectuals, widespread skepticism about the gods. Such developments belong to the later fifth and fourth centuries, and were a natural process in the world of the city-states, with popular religion naturally echoed in the art of the votive reliefs. In the changed world of the Hellenistic kingdoms, and directly influenced by the change, philosophic skepticism becomes much more cogent and much more popular. Gods are present for all to see in the mortal kings, while the traditional gods become much more dubious entities, and, even if they exist, of much less significance than the universally recognized and overriding power of Fortune, who can and does topple those divine kings, and might even at the same time, after all, shift lucky you, if not from log cabin to White House, at least from rags to riches. All this takes away much of the awe, and with the awe the fear, attaching to traditional gods and traditional stories. Such a shifting approach to religion would not in itself lead an artist to break down the barriers between the living world he inhabits and the divine one he is representing; but when his exploration of new ways in art led him in that direction it allowed him to do so, where an earlier artist might have felt (indeed the designer of the Nike balustrade perhaps did feel) a taboo: representations of the gods, like the gods themselves, were better kept in their own place.

Can we extrapolate from the specific case, and perhaps suggest that this new attitude, which really is a consequence of the world change, does color artists' approach to their art over a wider range than I have been allowing? Lysippos' pupils would surely have devised the all-round, spiraling composition for statues whatever the circumstances, and whoever the patrons for whom they worked; but the Tyche of Antioch, sitting in the open above the river, is not only a programmatic creation of her time at an artistic level but profoundly a figure of the new age in a much wider sense, and a profoundly influential one. So, too, it is perhaps unlikely that a city-state would ever have provided occasion for the adaptation, like Eumenes' Athena, of an earlier statue, conceived in a religious context, to a secular one. Similarly, the portraits of the first Hellenistic kings, on their coins and in other forms, are certainly part of a development of realistic portraiture in Greek art which reaches back into the classical age and would surely under any circumstances have gone on; but it is also important that they came into being as a direct result of new needs in the new Hellenistic situation, and became themselves a determining element in the growing popularity of the genre.

This is a ridiculous mouse of a conclusion; but perhaps during the labor things may have been touched on which may lead others to contribute more valuable insights; or perhaps, more probably, things I have failed to notice may lead to that desirable result. At any rate, this seems to be as far as I can get.

| • | • | • |

Response: J. J. Pollitt

It would be appropriate to the taste and style of the Hellenistic Age if Martin Robertson and I were to confront and challenge one another with radically different views of Hellenistic art. Unfortunately, I find myself in substantial agreement with almost everything he has said, and even our minor differences of opinion—such as our differing view of the role of oriental art in the development of naturalistic portraiture—are really only matters of emphasis.

I think, however, that I can stage a confrontation of another sort that may turn out to be equally interesting. In correspondence and conversation with Professor Robertson it has become clear that this symposium has provoked both of us to take a fresh look at Hellenistic art and to reassess our earlier evaluations of its basic character. In a sense, this meeting seems to have forced us to have a confrontation not with one another but with ourselves. In his great history of the whole of Greek art[1] and in my recent book on Hellenistic art[2] both of us tended to dwell on how the innovative features of Hellenistic art could be explained as responses to new social and political conditions of the period—the wider geographical horizon in which Greek art flourished, the advent of Hellenistic kingship, the growth of large urban centers with mixed populations, and so on. It is quite natural, when you are writing books of that sort, to look for what seems new and distinctive in the period with which you are dealing. Now that we have stepped back from that task, however, both of us seem to have found that in trying to define what was new we tended to deemphasize the continuity between Hellenistic art and earlier Greek art, a continuity that we would now agree was, in fact, very strong.

In my own book on Hellenistic art I emphasize five new attitudes in the Hellenistic Age that played a role in shaping its art. A new instability in systems of government, in the settlement of populations, and in the expectations of individuals for a settled life, led, I argue, to an obsession with fortune that is reflected in such things as the popularity of images of Tyche, in the appeal of images of Alexander for their seemingly talismanic power, and in the fascination with dramatic reversals of fortune (as, for example, in the painting that was the source of the Alexander mosaic). I also point to a theatrical mentality that grew out of the conviction that life in the Hellenistic period had somehow become a play written by fortune in which one must play one's part. The popularity of images from the theater in the decorative arts; the fondness for dramatic portraits that conveyed trials of the spirit (e.g., the Lysippan portraits of Alexander); the love of dramatic narrative crises (the Granikos monument, the Alexander sarcophagus); dramatic settings both for buildings (the Pergamene acropolis, the temple of Athena at Lindos) and for sculptural groups (the “lesser Attalid group” in Athens, the Nike of Samothrace); and, on a purely stylistic level, the prevalence of the “Hellenistic baroque” style, can all be seen as emanations of this new mentality.

As others have long argued, the social instability of the Hellenistic Age and the decline of small, tightly knit communities contributed to the development of still another distinctive mind-set of the Hellenistic period, individualism. The interest in distinct personalities in portraiture; the concern for individual states of consciousness such as fear, pain, drunkenness (see figure 18), or erotic excitement; and the exploration of personal religious emotion in the images of Sarapis and in mysterious architectural spaces like the Arsinoeion and Hieron at Samothrace, all reflect this new concern for personal, rather than communal, experiences and values. The corollary, as Tarn put it,[3] of individualism was a cosmopolitan outlook, a sympathetic curiosity about the entire inhabited world that lay beyond one's own social and ethnic traditions. Thus foreigners, derelicts, and exotic fauna and flora are all treated with interest, and usually with sympathy, in Hellenistic art (see figure 19).

Fig. 18.Drunken old woman. Roman marble copy of third- or second-century-B.C. original. Glyptothek, Munich. Photo Chr. Koppermann.

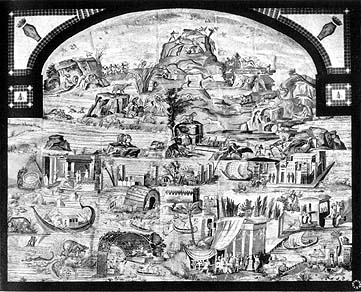

Fig. 19.Nilotic mosaic from Palestrina, circa 80 B.C. Museo Prenestino-Barberiniano, Palestrina.

Finally, there was the scholarly mentality that grew out of royally subsidized intellectual centers like the Library and Museum of Alexandria, which brought a didactic, learned quality to Hellenistic art that is expressed in such things as complicated allegories—for example, the stele of Archelaos (figure 20)—and in the learned, evocative pleasure that was derived from reviving and playing with earlier artistic styles, archaism and neoclassicism (see figures 21 and 22).

Fig. 20.Marble votic relief by Archelaos of Priene, circa 150 B.C. British Museum, London. Photo British Museum, courtesy of Trustees.

Fig. 21.Neo-Attic Maenad relief. Marble, circa 100 B.C. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Photo Alinari.

Fig. 22. Terme Boxer. Bronze, second or early first century B.C. National Museum of the Terme, Rome. Photo Alinari.

It is not my intention, like some beleaguered bureaucrat in a Marxist state whose policies have failed, to recant the line of thought that I have just sketched—I still think that it has basic validity—but I would like for a moment to look at Hellenistic art from another point of view. As Martin Robertson has emphasized in his paper, after one does one's best to identify what is really original about Hellenistic art, one keeps coming back to the unavoidable observation that most of the major developments of Hellenistic art grew quite explicably, if not entirely predictably, out of earlier Greek art. Until quite late in the period, when Hellenistic artists faced the challenge of satisfying the needs and taste of Roman patrons, there are no changes that one would be inclined to call revolutionary. Precedents for most of the major developments of Hellenistic art can be found in the art of the fourth century B.C. or even earlier. For example, a realistic trend in portraiture is anticipated in a number of portraits that belong to the fourth century. I would cite, in particular, those of Xenophon and Plato (figure 23)—although on the latter, let it be noted, Martin Robertson disagrees.

Fig. 23.Portrait of Plato. Roman marble copy of fourth-century-B.C. original. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. By permission.

Dramatic confrontations, and their accompanying pathos, can be found in the pedimental sculptures from Epidauros and Tegea, as well as in other sculptures, and literary sources suggest that they were explored in the paintings of Euphranor, Nikias, and Aristeides. The increasingly widespread use of personifications, including related groupings of personifications (e.g., Demokratia and Demos in the presence of Theseus in Euphranor's paintings in the Stoa Basileios in Athens) anticipate the didactic allegories of Hellenistic art. Personal religious emotions are anticipated in fourth-century images of Asklepios and perhaps in the unorthodox, mysterious interior of the temple of Apollo at Bassae. A retrospective view of style seems already to be present, on a limited scale, in the fifth century B.C. in the mannerism of the Pan Painter and the archaism of the sculptor Alkamenes. The “boy strangling a goose” type and other well-known Hellenistic images of children, while admittedly treated more playfully and lovingly than images of children had been in the classical period, represent the continuation of an earlier tradition of votive images of children. Even those images that are often thought to constitute social realism in Hellenistic art—old fishermen (figure 24), peasant women (figure 25), dwarfs, and the like—were anticipated in brief flashes in Greek vase painting (I think of the foreign-looking gentleman and his dog on the cup that is the name-vase of the Hegesiboulos Painter in New York [figure 26]) and apparently, judging by the literary evidence, in the art of the sculptor Demetrios of Alopeke.

Fig. 24.Old fisherman. Roman marble and alabaster copy of original of ? 200–150 B.C. Louvre, Paris. Photographie Giraudon.

Fig. 25.Old market woman. Marble, late second or early first century B.C. Metropolitan Museum, New York. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1909.

Fig. 26.Red-figured kylix attributed to the Hegesiboulos Painter. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1907.

In short, there are good reasons for concluding that what is “Hellenistic” about Hellenistic art is a matter of new emphasis rather than radical departure. There is a new look to many things, but continuity with the past is equally striking.

The one period in which this general observation seems not to be entirely true occurred, as I said earlier, in the late Hellenistic period when the resources of Hellenistic art were being put at the disposal of Roman patrons. In the Greco-Roman phase of Hellenistic art there were a few developments that seem to have had no clear Greek precedent and must be viewed as altogether new. A change that was clearly unprecedented, as Martin Robertson has observed, was the extension of the portrait sculptor's art to represent ordinary people who could claim no public distinction. We are, of course, familiar with such portraits in Roman art, where not only prominent public officials but also people of relatively low status—freedmen, for example—commissioned portraits. In the Greek world, on the other hand, portraits had always been reserved for people who were credited with some great achievement, such as military heroes, leaders in government, victorious athletes, or renowned philosophers, poets, and orators. In Greek portraiture, the “average person” was simply not of much interest. When viewed against this background, that remarkable series of realistic portraits found on Delos, dating from the late second and early first centuries B.C. and representing what seem to be Italian, Greek, and eastern Mediterranean businessmen (see figure 27a, figure 27b, appears quite remarkable and clearly constitutes something new. Such evidence as there is indicates that the artists who made them were Hellenistic Greeks; but they flourished in an international culture which was something other than traditionally Greek, and this culture challenged them to create an unprecedented genre.

Portrait from Delos, second or early first century B.C. Delos Museum. Exploration Archéologie de Délos, vol. xiii, pls. xxi, xxiii.

Portrait from Delos, second or early first century B.C. Delos Museum.

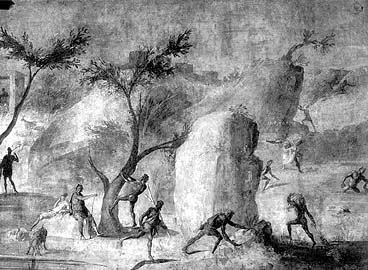

The atmospheric style of landscape painting that we find in the Odyssey landscapes (see figure 28) may be another example of an unprecedented development in Hellenistic art, although in this case, given the paucity of surviving Greek paintings, it could be argued that the Greek antecedents simply have not survived.

Fig. 28.Odyssey landscape: attack of the Laestrygonians. Vatican Museum, Rome. Photo Alinari.

A final thought. This symposium has provoked a number of interesting reflections on the role of frontiers in the Hellenistic world. The chief fountain of inspiration for the artists of the Hellenistic period was undeniably old Greece, but to the extent that they were affected by frontiers, I think it can be asserted that the most influential one was not the Sudan or the Hindu Kush; it was the Tiber.

| • | • | • |

Discussion

A. E. Samuel:Why are we looking at the same things we looked at fifty years ago and coming up with completely different conclusions? For example, the strictly Egyptian portraits of the Hellenistic period, which Egyptologists used to admit were influenced by Greek trends, are now being seen by Egyptologists as emerging directly from Egyptian traditions and precedents. Another example is the Anubis stele, which used to be considered a demonstration of the fusion of Greek and Egyptian art, having the Anubis head on the relief coupled with Greek architectural elements, but is now used as a demonstration of the separation of the two traditions. Why is this?

J. J. Pollitt:It's a deep philosophical question. (Laughter.) Why do literary classicists now undertake structuralist analyses of Virgil, and so on, whereas it didn't occur to previous generations to do such things? We continually reexamine the past in the light of ideas, theories, and problems that currently happen to interest us. I suppose that new attitudes toward works of art and literature have something to do with changing social and cultural conditions, as they did in the Hellenistic period. There seem to be inevitable changes in the things that succeeding generations find interesting and in the biases that they bring to historical studies. I doubt that this question is really answerable in a rigorous way. In some cases, as new data become available, we are virtually forced to reframe old questions and to look at monuments in a new way. This is the case with Macedonian art, for example, now that we know so much more about Macedonian painted tombs.

S. M. Burstein:One thing I have always found strikingly original about Hellenistic art is the sudden fascination with what one can only call the ugly. I am thinking of the wonderful series of statues such as the drunken old peasant woman or the crippled man going to the market. Is this in fact truly original, and in what conceivable context could these objects have functioned, aside from being experiments by the artist?

J. J. Pollitt:I myself believe that most of these old peasant women, fishermen, and so on, were votive sculptures dedicated in sanctuaries. We do have one literary reference, in Herodas, to votive sculptures of this sort in the Asklepieion at Cos. I think that the drunken old woman, the one in Munich (figure 18)—who is not really a peasant, incidentally; she wears fairly elaborate, expensive clothing—may have something to do with the Alexandrian festival called the lagynophoria in which aristocrats dressed up like peasants, sat on beds of straw with their bottles, and pretended to have a rustic picnic. But that's only a guess. In any case, I do think that these statues had a serious context of some sort, probably a religious one. There are a number of difficult questions about these sculptures. For example, were they unique to the Hellenistic period?

M. Robertson:There are no precedents in monumental art, but there are some ugly people on fifth-century vases, certainly, as well as among terracottas.

J. J. Pollitt:It does seem as if a tradition that we can identify earlier in vase painting and in statuettes has suddenly been applied to monumental sculpture.

N. Yalouris (former Director, Greek Archaeological Service):I liked Dr. Pollitt's point about the lack of revolutionary changes in Hellenistic art, that what we find here is, rather, a special emphasis on what happened in the past. This is confirmed by another fact. If we look at the literary activity of this period, all the intellectuals, poets, and philosophers devote most of their time and interest to the past, and to previous creations; what they want is to document, explain, and preserve them. Original activity in new forms of poetry is very unusual.

J. J. Pollitt:It does seem to have been a very self-conscious period, a period in which artists had a sophisticated awareness of what had gone on before. Hellenistic artists were surrounded by a wide array of earlier monuments, and these reverberated in their minds, I think, when they did their own work. The temptation to imitate or recreate earlier styles must always have been there, and when their patrons developed a nostalgic taste for the art of the past, the artists were ready and willing to gratify it.

E. S. Gruen:What I find particularly interesting about Professor Pollitt's formulation is that he identifies originality with the involvement of the Romans! Could he elaborate a little on what characteristics exactly he sees as original in this late, Greco-Roman phase of the Hellenistic period (150–50 B.C.)? Is it simply the fact of portraiture of private individuals rather than public figures, and if it is more, to what degree is Roman patronage directly responsible for it?

J. J. Pollitt:When I spoke about new developments under the influence of Roman patronage, I didn't mean, of course, that there was no originality in Hellenistic art prior to the Greco-Roman phase. I think that the development of realistic and dramatic representations of personalities in Hellenistic portrait sculpture, for example, is one of the most original developments in the entire period. What I meant in reference to the Greco-Roman phase was that there were new genres that were completely unprecedented and were not, like most developments in the Hellenistic period, predictable extensions of preceding traditions in Greek art. Portraits of average people, as opposed to prominent public figures, were not the greatest creations of Hellenistic art, but they were something that simply had not existed before.

I also think that the full-blown stylistic historicism of neo-Attic art is another example of innovation stimulated by Roman patronage. Traces of archaistic and classicistic mannerisms do, of course, turn up earlier in Greek art, but neo-Attic statues and reliefs have a special atmosphere about them. Romans in the first century B.C., like Cicero when he had his “college year abroad” in Athens, saw classical Greek culture as something comfortably remote, essentially finished, and all the more impressive precisely because it could be viewed from a distance. They were impressed by it in the same way that we, in our impressionable student days, were impressed by college surveys in the humanities. Getting some Greek culture meant a lot to people like Cicero before they went to law school, so to speak, and entered into the rough and tumble of Roman political life. There was a Romantic nostalgia about the whole experience. This feeling pervades neo-Attic reliefs. Old forms were reinterpreted in a poetic, learned, and somewhat distant way. This effect seems to have appealed to Roman patrons more than it did to Greeks. At first, neo-Attic reliefs and similar sculptures were made in workshops in Athens and shipped to Italy to be used in villas like Cicero's. Later on, many of the sculptors migrated to Rome to be nearer to their patrons.

N. G. L. Hammond:Could I raise the question of an early example of portraiture? The gold Alexander dedicated by Alexander I from spoils won against the Persians, was, presumably, a recognizable portrait of Alexander himself, made in his lifetime. A second example is the Alexander on the tetradrachm of Alexander I riding a horse with a dog underneath, which looks to me very much like a portrait of the king.

J. J. Pollitt:Yes, I think that there were portraits, at least from the time of the Persian Wars, that represented the actual appearance of people, at least to an extent. A representation of an individual doesn't have to be intensely realistic to qualify as a portrait. The question of what constitutes realism in a portrait is a highly subjective one. We tend to judge a portrait's realism by the number of naturalistic, idiosyncratic details that a portraitist is prepared to, or permitted to, incorporate into an image. But the fact that a particular work contains relatively few details of this sort does not mean that it is not a portrait. Classical Greek portraits seem more realistic when compared to Egyptian pharaonic portraits, and Hellenistic portraits seem more realistic when compared to those of classical Greece. The effects of each type were different, but they all functioned as portraits.

K. D. White:Where if anywhere does the great series of sacroidyllic paintings fit in, and where does the temple of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina fit into this later landscape, as it were, which you have been describing so eloquently?

J. J. Pollitt:As far as I can remember, all the sacroidyllic landscapes belong to the later first century B.C. or later; so, while they may have had Hellenistic precedents, what survives belongs to the early Roman Empire. Decoration on the Fortuna temple complex went on for a long time, and the date of the Nilotic mosaic has been debated, but it probably belongs to the time of Sulla, as the literary evidence suggests. A Greek painter called Demetrios the topographos is said to have migrated from Egypt to Italy, where he served as host to Ptolemy VI while the latter was in exile in Rome. Presumably he brought some sort of topographical painting with him, and this genre may be reflected in the Praeneste mosaic. The interchange of ideas between the Hellenistic world and Rome seems to be explicitly documented in this case, and once again we seem to be dealing with a form of art that was Hellenistic in origin but had an appeal for Roman patrons. Nilotic paintings, as you know, were popular in the Roman world and extend well beyond the Hellenistic period.

J. H. Kroll (University of Texas at Austin):The growth of museums and collections is very well documented in the Republican period, as the letters of Cicero show. And the major “museums” in Roman Imperial times were the great collections of Greek art in Rome, sometimes taken as spoils, and sometimes just the collections of connoisseurs. But is this an exclusively Roman phenomenon? Isn't Pergamon the best documented early location for the collection of sculpture and even copies of sculpture as museum pieces—as opposed to one of the traditional functions of art? I believe there are inscriptions from Pergamon which actually mention earlier statuary. Is that correct?

J. J. Pollitt:Yes, there are several inscriptions on bases at Pergamon that give the names of classical sculptors, most notably Myron, Praxiteles, and Kresilas. These seem to be labels rather than signatures. We can assume, I think, that one of the Attalid kings either collected some works by these sculptors, or had copies made, and exhibited his collection at Pergamon. We also know from literary evidence that Attalos II collected paintings. According to Pliny, he bought a painting of Dionysos by Aristeides from the spoils of Corinth, only to have it confiscated by Mummius.

M. Robertson:And Ptolemy III collected classical art, especially Sicyonian paintings.

J. H. Kroll:So this makes the Hellenistic kings the predecessors of the Romans, at least in the sense that the Romans were picking up on something that was well under way—at least this concern for the function of art, sculpture as something for a garden or a museum, rather than as a dedication or to honor someone. Couldn't you say, when trying to determine something specifically Hellenistic in the cultural sense about art, that there was a gradual shift from a world in which art was basically utilitarian (the archaic tradition) to a world which allowed more art for art's sake—or at least the addition of such a role for major works of art?

J. J. Pollitt:There were undoubtedly some things that were made for collectors and for the Roman art market. Much of neo-Attic art may fall into this category. I still think, however, that traditional functions—votive offerings, public commemorations, architectural decoration—can be ascribed to most works of Hellenistic art.

M. Robertson:The Pergamene and Ptolemaic collectors seem to have gone for old masters and not for contemporary work.

J. J. Pollitt:And the things that formed these collections by and large were not made for the collections; they were simply expropriated.

J. H. Kroll:Well, what about the seated boxer (figure 22), which you may see as a victory statue, but certainly isn't a victory statue in the traditional sense? Couldn't that be a museum piece?

J. J. Pollitt:We just don't have a context for it. I suppose it could have been made expressly for the art market, but I rather doubt it. I have no problem with seeing the boxer as a votive statue, originally set up in a sanctuary in some Greek city and later brought to Rome as booty.

J. H. Kroll:When do you have the first museums for sculpture built?

J. J. Pollitt:Well, clearly they existed in the first century B. C., when Pasiteles and Arkesilaos and the sons of Polykles were working for Roman patrons and selling works to collectors. We even hear, incidentally, of collectors paying extra money to get the original clay or plaster model of a particular work, so that no other copies could be made. They were intent on having the original masterpiece, not just one version among many. This mentality seems to arise at the very end of the Hellenistic period, in the last stages of the Greco-Roman phase.

At first, when most Greek art was coming to Rome in the form of booty, sculptures were exhibited in temples and in porticoes within the precincts of temples, like the Porticus Metelli. Later, when private collections were formed through the Roman art market, they were still sometimes placed in public buildings. The collection of Asinius Pollio, for example, one of the most avid Roman collectors, seems to have been housed in the library that he built into the Atrium Libertatis when he reconstructed it. Statues were also set up in baths and basilicas, although it's difficult to say whether or not such sculptures constituted “collections.” It's also reasonable to assume that some private collections were exhibited in the atria and porticoes of houses and villas. As far as I know, the ancient world didn't have any “pure” museums, that is, buildings that were used exclusively for the display of works of art. Ancient art galleries seem always to have had other functions as well, either public or domestic.

Unfortunately, we don't have a very clear idea of how ancient sculptures were exhibited in these ancient equivalents of museums; so it's difficult to say whether they were adequate by our standards or not.

Notes to Text

1. ABSA 46 (1951): 151–59.

2. M. Robertson, A History of Greek Art (Cambridge, 1975).

3. R. Carpenter, Greek Sculpture (Chicago, 1960), 214–16; C. M. Havelock, “Round Sculpture from the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos,” in Studies Presented to George M. A. Hanfmann (1971), 56–64, rebutted by B. Ashmole, “Solvitur Disputando,” in Festschrift für Frank Brommer (Mainz/Rhein, 1977), 1–20; see also G. B. Waywell, The Free-standing Sculptures of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus in the British Museum (London, 1978), 252 n. 215. After studying Waywell's catalogue I find it impossible not to suppose that the whole complex and its adornment were completed in a single operation over a relatively short period.

4. Robertson, History, 447.

5. J. J. Pollitt, Art in the Hellenistic Age (Cambridge, 1986). Belevi tomb: appendix 5, 289–90. Alexander's catafalque: 19–20.

6. Nemrud Dagh: H. Bossert, Altanatolien (Berlin, 1942), figs. 1017–19; E. Akurgal, Ancient Civilisations and Ruins of Turkey (Istanbul, 1969), pls. 109–12; Pollitt, Art, 274–75, fig. 294; Robertson, History, 565.

7. P. Bernard, Fouilles d'Ai Khanoum, Vol. 1 1973; (Paris, CRAI (1975): 175ff.; CRAI (1976): 291–92; Bulletin de l'école française d'extrème-Orient 63 (1976): 16ff.

8. See, e.g., Charles Seltman, Greek Coins (London, 1933), 55.

9. Pollitt, Art, 250.

10. See G. M. A. Richter, “The Origin of Verism in Roman Portraits,” JRS 45 (1955) 39–46 (against the idea but citing its proponents).

11. M. Robertson, A Shorter History of Greek Art (Cambridge, 1981), 183ff., figs. 249, 250.

12. Pollitt, Art, 64.

13. Ibid., 64, fig. 59; Robertson, History, 508–10, pl. 157d.

14. Robertson, History, 188, pl. 62d.

15. National Museum, Reggio di Calabria; G. M. A. Richter, The Portraits of the Greeks, abridged and revised by R. R. R. Smith (Oxford, 1984), 65, fig. 29.

16. B. S. Ridgway, “The Bronzes from the Porticello Wreck,” in Archaische und klassische griechische Plastik, ed. H. Kyrieleis (Mainz, 1986) 2:59–69, pls. 100–101.

17. See M. Robertson, “Greek Art and Religion,” in Greek Religion and Society, ed. P. E. Easterling and J. V. Muir (Cambridge, 1985), 155–90, fig. 33.

18. Pollitt, Art, 2–3, fig. 1; Robertson, History, 471–72 pl. 150a, b; Robertson, “Greek Art,” 189–90, fig. 44.

19. See Robertson, History, 383–85 (where the assertion that the head of the Apollo from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia is carved from a separate and finer piece of marble is false).

20. Pollitt, Art, 1–4 (the other four: 4–16).

21. See ibid., 31–33, figs. 20–22; Robertson, History, 516.

22. Detail of Alexander's head from the mosaic: J. Boardman, J. Dörig, W. Fuchs, and M. Hirmer, Die griechische Kunst (Munich, 1966), pl. xliv. Ptolemaic pair: Pollitt, Art, 272 fig. 293a. Seleucid pair; ibid., fig. 293d.

23. Robertson, History, pl. 161b (Demosthenes), d (Chrysippos); Pollitt, Art, 61, fig. 55 (Demosthenes), 69 fig. 66 (Chrysippos).

24. Pollitt, Art, 73–75, figs. 73, 75–77; Robertson, History, 598, pl. 190d.

25. Smith in Richter, Portraits, 176–80, figs. 139, 140, and frontispiece.

26. Barberini Faun: Pollitt, Art, 134, 137, fig. 146; Robertson, History, 534–35, pl. 169d. Victory of Samothrace: Pollitt, 113–16, fig. 117; Robertson, 535, pl. 137a. Ariadne: Robertson, 535, pl. 169c. Sleeping Hermaphrodite: Pollitt, 149, fig. 160; Robertson, 551–52, pl. 176b. Dying Gaul: Pollitt, 85–92, figs. 85, 87; Robertson, 531, 533, pls. 167c, 168b. Dying and dead from small dedication: Pollitt, 90–94, figs. 89, 91–94; Robertson 530, pls. 168a, 170c.

27. Pollitt, Art, 72–74; Robertson, History, 519–20, pls. 163c, 164a.

28. Pollitt, Art, 17.

29. Neil Hopkinson, ed., A Hellenistic Anthology (Cambridge, 1988).

30. Robertson, History, 286–87, 345–46, pl. 940 (Procne); 287–88, 350, pl. 94d (Nike of Paeonius).

31. Motya, Museo Whitaker; V. Tusa, “Il giovane di Mozia,” in Archaische und klassische griechische Plastik 2:1–11, pls. 82–85. Both date and identification are disputed; but it seems to me likely that the garb marks the figure as a charioteer, and certain that it cannot have been carved much after the decade 470–60.

32. Parthenon Poseidon: F. Brommer, Die Skulpturen der Parthenon-Giebel (Mainz, 1963), pls. 103–6. Scopasian head from Tegea: e.g., Robertson, History, pl. 145. Pergamene altar slabs with comparable torsos and faces: e.g., ibid., pl. 170d; Pollitt, Art, 98 figs. 99–100.

33. Meeting of carved frieze with steps just visible: Pollitt, Art, 95 fig. 97; with steps well seen: E. Simon, Hesiod und Pergamon (Mainz, 1975), pl. 1.

34. B. Carpenter, The Sculpture of the Nike Temple Parapet (Harvard, 1929), pl. 1 (photo of slab), fig. 15 (drawing showing relation to steps).

Notes to Response

1. Martin Robertson, A History of Greek Art (Cambridge, 1975), 445–590.

2. J. J. Pollitt, Art in the Hellenistic Age (Cambridge, 1986).

3. W. W. Tarn, Hellenistic Civilization, 3d ed. (London, 1952), 2.