2. Redemptive Suffering and the Patron Saint of Tuberculosis

Mais j’ai compris. Je suis expiatoire.

…renonçant, priant, demandant à souffrir,

S’allonge pour se tendre, et mincit pour s’offrir!

…l’aiglon se résigne

A la mort innocente et ployante d’un cygne.

[ I understand. I am the atonement.

…renouncing, praying, begging to suffer,

I lay myself out, emaciated, as an offering!

…the eaglet is resigned

To the innocent and docile death of a swan.]

God has deigned to make me pass through many types of trials.…I am truly happy to suffer.

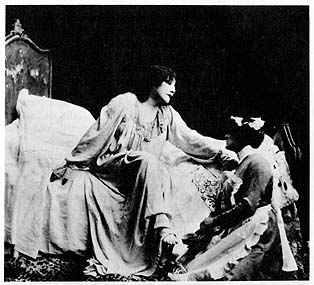

In the late 1890s, the legendary French actress Sarah Bernhardt captivated theatergoers in France and abroad as few performers have before or since. At the zenith of her popularity, the woman known as “the divine Sarah” enjoyed unprecedented adoration, and her decisions regarding which works to perform and with whom made or broke the reputations of playwrights and fellow actors. In the autumn of 1897, after touring Belgium, Sarah returned to Paris and began a financially successful and critically acclaimed run of La Dame aux camélias, the work with which she is more closely identified than any other in her long career. Her portrayal of Marguerite Gautier, the kind-hearted courtesan doomed to an untimely death from tuberculosis, epitomized to many of her admirers her brilliance on the stage.[1]

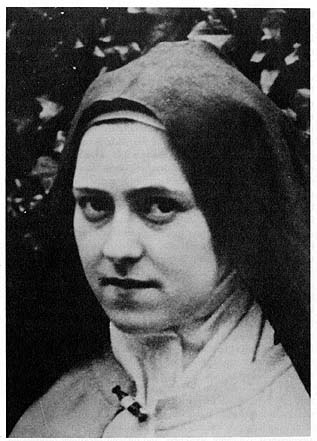

Meanwhile, also in the autumn of 1897, a young nun in the Carmelite convent of Lisieux was enacting her own death scene from tuberculosis—this one all too real, but no less staged. Twenty-four-year-old Thérèse Martin had led an uneventful and sheltered life, taking the veil at age fifteen. Her precarious health had deteriorated under the assault of tuberculosis, and she spent much of her last few years in the convent’s infirmary. During her illness, Sister Thérèse began to keep a diary at the insistence of the mother superior. She continued to record her emotions right up until her death, after which the convent authorities decided to publish her writings as an autobiography, entitled Story of a Soul. With its simple, accessible spirituality and its exaltation of all things humble, the book quickly sold out of several printings and was translated into nine languages within five years; Thérèse soon became a cult figure among Catholics both in France and abroad. In 1925, she became Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face, and during World War II, Pope Pius XII proclaimed her co-patron saint of France, along with Joan of Arc.[2] (In English-speaking countries, she is better known as “the Little Flower of Jesus,” or simply as “Little Flower.”)

What could possibly connect these two very different celebrities, Sarah Bernhardt and Saint Thérèse of Lisieux? After all, they seem to represent opposite poles of womanhood: one, perhaps the quintessential society figure of her time, was born into prostitution and saw her adult romantic liaisons become the object of public scrutiny; the other lived at a distant remove from society and died a virgin. However, there are intriguing ties of sorority that bind this unlikely pair, the worldly and the cloistered, the actress and the nun. Both played important roles in the elaboration of a versatile and long-lasting cultural vision that associated tuberculosis with a heightened state of creativity, emotion, and spirituality and that lent a tragic and redemptive quality to the disease.

Briefly stated, tuberculosis served as a key vehicle in the nineteenth century through which womanhood was associated with a kind of suffering that was morally and spiritually redeeming. Moreover, around the turn of the century, even as the French state and the medical and philanthropic communities were elaborating and actively promoting a new vision of tuberculosis as a social problem of the first magnitude, the older reading of the disease as a sign of redemptive suffering persisted and even thrived, in a sense complementing but also implicitly contesting the new sociomedical orthodoxy. The association of womanhood with tuberculosis—and, through tuberculosis, with suffering and redemption—survived in part because it addressed a cultural need that medical discourse and organized social reform movements could not fulfill. And although it may have done so initially and most memorably through artistic media such as literature, theater, and opera, the ideal of the suffering female consumptive operated in other realms as well. Evidence of its power can be found in the real-life infirmary at the convent in Lisieux and on the pages of Thérèse’s autobiography as well as on stage in Sarah’s unforgettable deathbed scenes. To understand the allure of the suffering saint and the captivating actress around the turn of the century, one must look back to the years before germ theory, when medicine looked to passion, temperament, and individual essence to explain illness. One must also take seriously the act of storytelling as a means of understanding disease.

For much of the nineteenth century, making sense of the familiar but little-understood scourge of tuberculosis—and making sense of life through tuberculosis—involved, above all, telling stories. The stories of tuberculosis that have survived from this era and are retold most often are fictional ones, literary and artistic productions that stand as enduring portraits of suffering, love, and redemption. The sweet, agonizing deaths of Fantine, Mimi, and Camille (in Les Misérables,La Bohème, and Camille/La Traviata) are especially familiar today on page, stage, and screen, and all originated in mid-nineteenth-century French novels. Yet the use of narrative in representing tuberculosis is hardly exhausted by novels, plays, and operas. Nonfictional narratives of the disease—in texts ranging from diaries and memoirs to medical publications and political debates—were equally central in efforts to make sense of life, illness, and death in the nineteenth century. Certain ingredients in both the content and the style of the various tuberculosis stories seem to have made narrative a particularly compelling strategy in all of these contexts.[3] Medical and political texts will provide the material for subsequent chapters; here stories (both fictional and otherwise) from the worlds of literature, the performing arts, and religion will be examined for their treatment of one particularly enduring theme: the association of womanhood with suffering and redemption.

The image of the frail, consumptive heroine sanctified through illness and death resonates throughout nineteenth-century French literature. From Marguerite Gautier to the bohemian Francine/Mimi to Hugo’s desperate Fantine, tuberculosis seems to have been the preferred cause of death for a certain type of female character. For the purposes of this discussion, five novels (including two that became famous operas) and one play manifest the most significant aspects of the consumptive ideal: Dumas’s La Dame aux camélias (later Verdi’s La Traviata), Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème (later Puccini’s La Bohème), Hugo’s Les Misérables, the Goncourt brothers’ Madame Gervaisais and Germinie Lacerteux, and Rostand’s L’Aiglon. Each of these works deals in some important way with tuberculosis, as does the nonfictional story of Thérèse Martin, who appropriated the consumptive ideal in coming to terms with her own disease. No choice of just six literary works covering more than a half-century of French culture can be truly representative, and there are many others that involve tuberculosis in some way.[4] These six, however, exemplify several different ways of using tuberculosis to tell stories, all the while pointing to the predominance, versatility, and enduring power of the redemptive-spiritual perspective on consumption and womanhood. While this persistent literary theme is commonly referred to as “romantic,” the term is—like its counterpart “romantic medicine”[5]—evocative but technically misleading: only Dumas fils, Murger, and Hugo can plausibly be associated with the literary movement of romanticism, and they were on the cusp of realism. However, all the works under discussion here, in addition to dealing with tuberculosis, share the preoccupation with sentimentality, passion, and spirituality that characterized romanticism.

Most historians of tuberculosis have tended to treat the romantic literary vision either as a quaint, entertaining sidelight to the medical history of the disease or as support for the contention that the disease sets in motion biochemical processes that actually heighten patients’ passion, sex drive, and emotional experience. A few have taken the consumptive ideal more seriously as a historical phenomenon of the early and mid-nineteenth century; they argue that by the end of the century, it was replaced or supplanted by the sociomedical view of tuberculosis, and the tragic romantic heroine gave way to the specter of the contagious, working-class semeur de bacilles (“sower” or “disseminator” of bacilli).[6] This chapter attempts to show, on the contrary, that the redemptive-spiritual view persisted long after the sociomedical understanding arose and that (far from being mutually exclusive) the two sets of meanings coexisted, at once complementing and contesting each other, throughout the Belle Epoque.

| • | • | • |

Sanctifying the Fallen Woman: Dumas, Murger, Hugo

La Dame aux camélias, best known to later audiences as Verdi’s opera La Traviata, stands as perhaps the consummate expression of the nineteenth-century consumptive ideal.[7] In the novel, first published in 1848, Alexandre Dumas fils brings together all the elements through which tuberculosis conveyed an idealized image of femininity in the nineteenth century: the disease’s wasting effect on the body is portrayed as enhancing feminine beauty; the fallen woman is paradoxically depicted as more virtuous than the “respectable” citizens around her; the impossibility of pure love in an imperfect world propels the tragic inevitability of the plot; and the heroine is finally redeemed through suffering and death. The consumptive courtesan Marguerite Gautier comes to represent Everywoman, required to be both virtuous and alluring, and compelled to find identity in worldly suffering and the promise of otherworldly redemption.

6. Sarah Bernhardt in La Dame aux camélias, 1913. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

When Marguerite meets the young bachelor Armand Duval and finds true love for the first time, she faces a dilemma: to maintain her extravagant and leisurely life in Paris, where her wealthy patron, the Count of Varville, provides for her every material need, or to abandon that life for her lover of more modest means. She chooses to follow her heart and leaves for the provinces with Armand. This choice, however, immediately confronts Marguerite with her second dilemma, the problem at the heart of the novel’s tragic development. Even true love cannot change her fundamental status as sinner against—and outcast from—bourgeois morality. Armand’s family cannot tolerate the couple’s continued liaison, and his father pleads with Marguerite to end it. The relationship has sullied the family name and endangered the impending marriage of Armand’s sister. Marguerite feels the strong pull of emotional attachment, a feeling foreign to her previous life as a fashionable prostitute, but realizes that her love for Armand is an impossible one under the prevailing cultural circumstances. Forced to renounce her love (and forbidden by his father to tell Armand of the real reason), Marguerite returns to Paris and to prostitution. Before long, however, emotional anguish and tuberculosis take their toll. In an emotional deathbed scene, she is reconciled with Armand and with her fate; she dies ennobled and at peace.

As much as any literary heroine, Marguerite embodies the classic saint-and-sinner dichotomy imputed to woman’s nature in nineteenth-century bourgeois society. She was “the virgin that a trifle [un rien] had made a courtesan, and the courtesan that a trifle would have made the most loving and pure virgin.”[8] But this trifle made all the difference and sealed her fate. In the case of Marguerite, tuberculosis is more than an illness. It is her condition, her destiny, something to be resigned to, not to be cured. “Ah! There’s no point in you getting alarmed,” she reassures Armand after a coughing spell, “there’s nothing anyone can do about this sickness.” Like other tuberculous heroines, and like all martyrs, she accepts her destiny bravely and stoically: “Girls like me, one more or one less, what does it matter?” “Doomed to live a shorter life than others, I’ve promised myself to live a faster one.”[9]

Like death from tuberculosis, Marguerite’s fate is inevitable: she tries twice, once before and once after meeting Armand, to reenter polite society, but each time she is not accepted. On the novel’s final page, Dumas wonders whether “all girls like Marguerite” (that is, all prostitutes) would be able to do what she did: “I only know that one of them felt in her life a serious love, that she suffered from it, and that she died of it.”[10] Tuberculosis plays a crucial role as vehicle of both suffering and death. Yet the couple’s love is impossible—and demands such harsh retribution—only because of social convention. As various critics have pointed out, society will not allow Marguerite to live; it cannot incorporate her type of woman, when social conformity is a higher imperative than love. “Happiness can only be realized,” one critic has written, “in conformity with regular conditions of social life.…[I]n the name of society, [Dumas] condemns the courtesan.”[11] Marguerite’s redemption is real but is not based only on love.

Only renunciation and death could ultimately bring out the virgin in the courtesan.Marguerite is redeemed, not just because of the depth and sincerity of her love for Armand…but rather because of her heroic renunciation of this love for the sake of Armand and of society, and her acceptance of her punishment, because of her realization that she is wrong and the community right; so that, as she lies dying, all but excised from the social body, Armand may without fear of contamination return to her.[12]

With all of the sentimentality of La Dame aux camélias but somewhat less of the tragedy, Henry Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème[13] presents the death of a consumptive heroine in a minor key. The novel, a pastiche of episodes and portraits serialized in Le Corsaire between 1845 and 1849 and published as a novel in 1851, depicts the unstable and often comical existence of Bohemian writers, artists, and grisettes in Paris. The bulk of Murger’s novel is concerned with the stormy relationship of Rodolphe and Mimi; the latter displays the pallid beauty and joie de vivre of the typical consumptive heroine but is not portrayed as ill. One chapter or “scene” concerns the ill-fated romance of Jacques and Francine, two friends of Rodolphe and Mimi; Francine is this novel’s embodiment of fateful and beautiful suffering from tuberculosis.[14]

In both Mimi and Francine, Murger uses the physical type of the consumptive woman to signify beauty, youth, and carefree passion. Mimi is described as frail and delicate, “as pale as the angel of consumption.” “The blood of youth [runs] hot and fast in her veins, and add[s] a rosy tint to her skin, [otherwise] transparent with the whiteness of a camelia.”[15] It is unclear whether this description was written before or after the publication of La Dame aux camélias, although the camelia’s echo is hardly coincidental. As a personal fetish, Marie Duplessis, the real-life inspiration for Marguerite in Dumas’s novel, surrounded herself with camelias. Consumptive heroines up to and including Thérèse of Lisieux are often associated with flowers, a symbol of ephemeral beauty and the transitory nature of life itself.

The character of Francine develops even more clearly the mutual association of tuberculosis, womanhood, and ephemeral beauty. In her, as in most of her fictional counterparts, the essentialist perspective on disease assumes a literary, nonmedical form. The view of tuberculosis as part of one’s essence and underlying identity, which led Laënnec and other medical authorities to seek the disease’s causes in heredity, lymphatic temperament, and “sad passions,”[16] led Murger and other novelists to depict it as the tragic, inevitable destiny of their heroines—a trait as fundamental to their identities as their femininity or their beauty. For Francine, it is “a vague premonition of her imminent passing” (un vague pressentiment de sa fin prochaine) that leads her at age twenty to abandon herself completely to her love for Jacques. It soon becomes apparent to both young lovers that Francine is a poitrinaire, or consumptive, and shortly after their romance begins in the spring, a doctor friend tells Jacques that Francine will not live past the “yellow leaves” of autumn.[17] Francine’s beauty is both timeless (in its purity) and ephemeral, and like the elemental, seasonal cycles of nature—like the falling leaves and the camelias—tuberculosis did not leave beauty much time to blossom before dying.

On her deathbed, knowing that she will soon die but wishing to shield Jacques from this fact, Francine asks him to buy her a fancy fur muff to keep her hands warm. The last yellow leaf from the tree outside her room then blows through her open window and onto her bed; the two lovers spend one last night together, and in the morning, on All Saints’ Day, Francine dies, clinging to her muff for warmth. She knew that she was dying, “because God does not want me to live any longer,” and her last words were “my God!” Through her illness, Francine is clearly sanctified in death, and when Jacques arranges her body for the casting of a death mask, the light “cast all of its clarity on the consumptive’s face,” giving her a saintly glow, “as if she had died of beauty.” At the funeral, Jacques cries out, “O my youth! It is you that we are burying!”[18] Youth, pure beauty, and passion are not permanently of this earth in the romantic worldview; they express their purity and achieve transcendence only through death, thereby becoming celestial ideals that live on forever. Like Marguerite, though without the full weight of her social stigma, Francine was too pure and beautiful for her earthly existence; tuberculosis both proved these women’s purity and purified them.

Ten years after Dumas and Murger, Victor Hugo used tuberculosis to tell quite a different story, but in so doing he reinforced the basic tenets of the redemptive-spiritual perspective and the consumptive ideal of womanhood. In his epic Les Misérables (1862), Hugo unremittingly attacks greed, callousness, and injustice in society. The story of Fantine—a case of “society buying a slave” and finally killing her—serves as a particularly effective vehicle for his social message. Yet it is significant that the means by which Fantine becomes a martyr to the cause of social justice all but replicates the treatment of such apparently nonpolitical heroines as Marguerite and Francine. It is above all the “grace, frailty, [and] beauty” of women in general and Fantine in particular that contain the feminine destiny: for Fantine, these qualities doom her to prostitution when she is unfairly fired from her factory job and must somehow find money to pay for her daughter Cosette’s room and board.[19] Hugo echoes and amplifies Dumas in insisting on the thinness of the line between virtuous and fallen and in suggesting that women are imprisoned in this dichotomy that allows no middle ground.

7. Jean Valjean at Fantine’s deathbed. Illustration by Bayard, from the Hughes edition of Les Misérables (1879-1882).

Hugo also allows no uncertainty on the matter of the immediate origins of Fantine’s illness; for example, “excessive work fatigued Fantine, and her slight dry cough got worse.” Labor and poverty cause her tuberculosis, which worsens with her deteriorating material condition and improves only when she is given hope that she would soon be reunited with Cosette. In the end, Fantine’s illness is both sign and vehicle of her martyrdom; on her deathbed, Jean Valjean even tells her, “I was praying to the martyr on high,” then adds under his breath, “—for the martyr here below.” As he makes his fateful promise to look after Cosette in Fantine’s absence, Valjean reassures the dying mother that her suffering and death are necessary: “It is in this way that mortals become angels.…This hell you have just left is the first step toward Heaven. You had to begin there.” When Fantine dies, Hugo does not skimp on the traces of her martyrdom and saintliness. Her body trembles as if “an unseen fluttering of wings” is preparing to take her away; “she looked more likely to soar away than to die”; “at this instant Fantine’s face seemed strangely luminous.”[20] The tuberculosis that originated in her poverty and fatigue serves to lift her above her earthly condition, and her martyrdom redeems not her own sins but the sins of an unjust society.

Fantine’s demise recalls that of American literature’s most saintly tuberculosis victim, Little Eva of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Critic Jane Tompkins has argued that the sentimentality of such nineteenth-century women’s novels—rather than providing escape from or even justifying “an oppressive social order”—served in its own way as an effective form of protest. In Tompkins’s view, the common critical assessment of Little Eva’s death as “nothing more than a sob story” ignores the ways in which extreme sentimentality can express “a theory of power.”

The same can be said of Hugo’s Fantine. The angelic aura surrounding her death and the circumstances of her life and illness certainly increase through sentimentality her image as socially redemptive martyr. But the same cannot be said of her fellow French literary victims of tuberculosis, whose suffering seems to redeem mainly themselves and women as a class. In this context, Fantine is exceptional in her political message but typical in her femininity, in the paradox of her purity and prostitution, and in her physical suffering. The most salient characteristic that binds all of these figures together, in short, is what it means to be a woman.Stories like the death of little Eva are compelling for the same reason that the story of Christ’s death is compelling: they enact a philosophy, as much political as religious, in which the pure and powerless die to save the powerful and corrupt, and thereby show themselves more powerful than those they save.[21]

| • | • | • |

Later Variations on a Romantic Theme

When romantic sentimentalism fell out of favor in French literature, the theme of women suffering from tuberculosis endured. Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, in two of their best-known novels, Germinie Lacerteux and Madame Gervaisais, managed to adopt the traditional literary usage of tuberculosis without endorsing it. Their occasionally cynical attitude toward their heroines implies that their handling of tuberculosis is meant to critique or even denounce the romantic tradition. However, in the final analysis, their treatment conforms so closely to that of their predecessors that the authors’ intentions become irrelevant. They use tuberculosis to evoke a certain constellation of emotions and values; this evocation ultimately takes center stage, whether the Goncourts ultimately wish to project or reject these values.

Although the novel appeared only two years after Les Misérables, the title character of Germinie Lacerteux (1864) will never be confused with Fantine.[22] The unhappy domestic is continually beaten down by poverty and love, her attachment to an undeserving paramour leading her into a morass of self-destruction and despair. Germinie inherits the worst of both Marguerite and Fantine, devoted beyond reason to an impossible relationship, driven to drink and even a kind of prostitution. That tuberculosis finally claims Germinie testifies—on the surface—only to the depths of her self-abasement. “She sought to imagine the degree of humiliation to which her love would refuse to sink, but she could not find it.…[S]he would remain under the heel of his boots!” None of her acquaintances sinks so low in love; none invests the “bitterness, torment, [and] happiness in suffering” that Germinie puts into her liaison with Jupillon. It “killed her and she could not do without [it].” In stark contrast to Marguerite Gautier, Germinie goes to extraordinary lengths to maintain her impossible relationship, showering her lover with gifts that she cannot afford.[23]

Nevertheless, no matter how much the Goncourts depict Germinie’s suffering as debased rather than exalted, she retains the fundamental qualities of woman’s nature that qualify her for elevation to the status of consumptive heroine. When Jupillon is avoiding her and she stakes out his apartment in the rain, Germinie is wet and miserable yet strangely oblivious to her circumstances. She no longer feels anything “except the suffering of the soul.” After Germinie eventually dies in the hospital, having sunk to the lowest depths imaginable, having lost money, love, sanity, and dignity, her employer (Mlle. de Varandeuil) is haunted by visions of her face in death. The horror is gone from the face in the apparition; “only suffering remained there, but [it was] a suffering of expiation, almost of prayer.”[24] Finally, after plumbing the depths of humiliation, stripped of all but her last shred of humanity, Germinie is redeemed and purified. Of course, this redemption and purification takes place only in the imagination of the pious and moralistic Mlle. de Varandeuil. The authors appear to distance themselves from this exaltation of Germinie, if not ridicule it outright; yet they give her suffering and death no other meaning, no alternative interpretation. Like Marguerite, she dies as both sinner and victim, for whom tuberculosis provides deliverance and atonement.

If Germinie Lacerteux comes from the gray area where woman’s nature meets the accident of social circumstance, the Goncourt brothers’ other consumptive protagonist represents a hothouse variety of the spirituality contained in the French literary-religious reading of tuberculosis. Madame Gervaisais has scarcely any bodily existence at all; because of her tuberculosis, every physical description of her downplays her corporeality and highlights her asceticism. “Barely terrestrial,” with the “austere figure of a psychic creature,” she lives a life that becomes with each passing day more ethereal and less connected to her earthly surroundings. Starting a new life and convalescence with her young son in Rome, the Frenchwoman falls under the influence of zealous clerics who lead her into renunciation and fanaticism. Tuberculosis, which “softly snuffed out the life of Mme. Gervaisais,…singularly helped steer the mysticism…of this body that was becoming a spirit toward the supernatural achievement of spirituality.”[25]

Once again, self-abasement and love of suffering are essential elements of the female identity. As Madame Gervaisais’s religious practices become more and more severe, her illness intensifies. First she “cloisters” herself in her apartment, limiting as much as possible her contact with the outside world. Then she begins to revel in humility and privation.

Madame Gervaisais’s “ambition” is to achieve a state of “holy everyday torture.” Her health deteriorates, but she accepts it with “that pious fatalism that the exaltation of devotion often brings to women”; she sees her illness as a matter “in God’s hands,” and “suffering bec[omes] in her eyes a kind of spiritual advancement.”[26]The more she absorbed the humility prescribed by her ascetic readings,…the more she heard herself repeating…that she deserved disdain and abjection…that she was worthy of horror, damnation, anathema, execration—the closer she approached to the lowest depths of abasement and loss of personality.

The correspondence of themes between Madame Gervaisais and Thérèse of Lisieux’s autobiography (discussed more fully below) is striking, as are their similar responses to suffering. The Goncourts’ novel can be read as a critique of religious attitudes that they considered prevalent or at least a culturally significant phenomenon—attitudes that Thérèse shared and developed even further in her life and writings. The Goncourts obviously regarded such attitudes with a certain amount of disdain. For example, they perceive in their novel a causal relation between Madame Gervaisais’s tuberculosis and her spiritual excesses.

This ascription of mental and emotional symptoms to tuberculosis is part of the traditional romantic view, although the Goncourts clearly scorn these “hallucinatory” religious manifestations. More significant, perhaps, than their judgment of such “pious fatalism” and “exaltation of devotion” is their association of it—along with many other romantic and later authors—with womanhood and with the female condition. In other words, the Goncourts seem to share the romantic/Christian view of woman’s essence, and they too use tuberculosis to express it, even though they ridicule rather than celebrate woman and her religious spirituality.The disease, the slow disease that extinguished almost softly the life of Mme. Gervaisais, phtisis singularly helped along [her] mysticism [and] ecstasy.…[T]he gradual…death of the flesh under the cavernous ravages of the disease [and] the growing dematerialization of the physical being took her ever closer to the holy folly and hallucinated delights of religious love [vers les folies saintes et les délices hallucinées de l’amour religieux].[27]

On the surface, a male tuberculous protagonist who captured the public imagination would seem to belie the contention that the redemptive-spiritual understanding of tuberculosis in the nineteenth century rested on a certain perception of womanhood. However, the Duke of Reichstadt in Rostand’s play L’Aiglon actually reinforces the consumptive ideal by deviating from it. His character is feminized to such an extent—and his fate so closely linked to this feminization—that he becomes an appropriate exemplar of a traditionally female cultural role. In fact, Rostand wrote the part of “the Eaglet” expressly for his friend Sarah Bernhardt, and she inaugurated the role at the play’s premiere on March 15, 1900.[28]L’Aiglon covers the last two years of the duke’s life in the Austrian palace of Schönbrunn before his death from tuberculosis in 1832, at age twenty-one. The play focuses on the tragedy of his thwarted destiny as the frail and sickly son of the vigorous and heroic emperor; it follows his strained relationship with his mother and with the wily Prince Metternich, who is haunted by the first Napoleon, and it builds up to the climax of a nearly successful conspiracy to return the duke to France.

In one especially revealing scene, Flambeau, the loyal, incognito veteran of the Napoleonic wars, torments Metternich with convincing evocations of the empire. The terrified, delusional Metternich is taken in by Flambeau’s ruse and half expects Napoleon himself to appear from the bedroom. Instead, it is a coughing young duke who emerges to find the cause of the ruckus distracting him: Rostand’s stage directions describe his appearance.

Throughout the play, the duke is portrayed as feminine both in appearance and in personality: he is highly sensitive, emotional, and indecisive à la Hamlet, another of Sarah’s famous roles.Instead of the terrible, short and thickset silhouette that [Flambeau] had almost made one expect to see, on the threshold is the unsteady apparition of a mere child, too slim…white as his gown…rendered even more feminine by his unfastened collar, under which the fabric of an undergarment was visible, and by his blond hair in the lamplight.[29]

As is the case with his female literary counterparts, the duke’s tuberculosis is part of his tragic essence, and he realizes it. When he is asked by a young Bonapartist conspirator, “Pale prince, so pale in your black tie, / What makes you pale?” the duke replies, “Being his son!” Later, he reflects on the meaning of his own death. “It is not from the crude poisoning of melodramas / That the Duke of Reichstadt is dying: it is from his soul! /…From my soul and my name!”[30] This essentialist explanation fits the romantic pattern: his illness expresses his sensitivity and his thwarted destiny, which in turn comes from his innate inability to live up to his father. (Rostand traces this failing to the Hapsburg bloodline of the duke’s mother, Napoleon’s second wife, Marie-Louise.[31]) In the end, as also befits the consumptive ideal, the essential affliction is redemptive. Coughing up blood as he surveys the plain of Wagram, site of the emperor’s glorious victory in 1809, the cries of the battle’s victims ringing in his ears, the frail duke envisions his suffering and death as atonement for the blood spilled by his father’s armies.

| I understand. I am the atonement. | |

| . . . renouncing, praying, begging to suffer, | |

| I lay myself out, emaciated, as an offering! | |

| . . . the eaglet is resigned | |

| To the innocent and docile death of a swan.[32] |

Thus, even with its male protagonist and referents, L’Aiglon evokes the essentialist ideal of tuberculosis, feminine suffering, and redemption. To be sure, the real Duke of Reichstadt did in fact die of tuberculosis, so Rostand did not simply choose the disease as a vehicle for a certain set of values. No account of the “Eaglet’s” life could plausibly have ignored the cause of his untimely death. Nonetheless, Rostand did emphasize the disease—and the many cultural associations that went along with it—as both sign of his tragic essence and (in part) cause of his failure to measure up to his father. Like the Goncourts’ satire, Rostand’s deviation from the conventional redemptive-spiritual depiction of tuberculosis only preserved and strengthened its fundamental tenets.

| • | • | • |

The Consumptive Heroine as Saint: Thérèse of Lisieux

The consumptive career of Thérèse Martin is both simpler and harder to grasp than those of her fictional counterparts. The spoiled youngest of five daughters in a devout family, Thérèse entered the convent at fifteen, permission for which required special dispensation from the Catholic hierarchy. She lived there for nine years, before dying in the convent infirmary in 1897. As a result of her sheltered and cloistered existence, in contrast to most saints, Thérèse experienced and accomplished next to nothing in her entire life. Just before taking the habit, she prayed for the soul of a convicted murderer on the eve of his execution; it was later reported that the condemned man repented and kissed a crucifix after mounting the guillotine. This was the only instance of intercession or worldly works in her short life. (After her death, many miracles were attributed to her intervention, often involving wounds healed or illnesses cured after prayers addressed to her.) Although she never left Normandy except for a childhood visit to the Vatican, she was made patron saint of missions in 1927, two years after her canonization.[34]

8. Thérèse in June 1897, three months before her death. Photo courtesy of the Office central de Lisieux.

Thérèse is a puzzle. The only thing she did that can explain her popularity and sainthood was write her memoirs—itself a strange undertaking for an adolescent girl who had little life experience. It is testimony to her unique brand of spirituality, to what she called her “little way,” that when published after her death, her autobiography achieved such lasting popularity and inspired a cult that lasts to this day. Lisieux is perennially the second most popular pilgrimage destination in France, after Lourdes. Statues of Thérèse stand in thousands of Catholic churches around the world, objects of veneration especially for women and children. Her popularity sparked a kind of religious revival in early-twentieth-century France and forced the church to begin canonization proceedings despite the opposition of some ecclesiastical authorities.[35]

Simply put, Thérèse did little else in life but fall ill, suffer, write, and die. The hallmarks of her life were her suffering and her writing, and therein must lie the key to her extraordinary popularity. The inescapable conclusion suggested by Story of a Soul, Thérèse’s autobiography, is that she wrote about suffering in a manner that closely parallels the fictional ideal of consumptive woman. Her “little way” touted self-effacement bordering on self-abasement and humility that verged on humiliation as the path to saintliness. In the convent, Thérèse shunned material comforts such as warmth and food and suffered everyday injustices and jealousies in silence. (Just one of the paradoxes of her autobiography is that she cannot communicate the importance of suffering in silence without breaking that silence in a detailed and sustained fashion; she dwells at length on petty episodes so as to urge that such matters not be dwelled on or complained about.) Thérèse deliberately sat next to the most annoying gossip in the convent at refectory and endured her torment silently; she even prevented herself from leaning back in her chair. In the early stages of her illness, she refused special treatment and insisted on going about her chores as usual.[36]

Tuberculosis was indeed the chief vehicle of suffering in Thérèse’s life. No incident better illustrates the importance of the disease in her spiritual world than the Good Friday hemoptysis. After observing a rigorous Lenten fast in 1896, Thérèse went to bed on the eve of Good Friday and felt a joyous sensation.

The morning of the sacred day brought confirmation of her fate, as she indeed found blood on her handkerchief.Oh! how sweet this memory really is!.…I had scarcely laid my head upon the pillow when I felt something like a bubbling stream mounting to my lips. I didn’t know what it was, but I thought that perhaps I was going to die and my soul was flooded with joy.

This hemoptysis, or coughing up of blood, meant tuberculosis, and tuberculosis meant death. It was Thérèse’s first externally verifiable sign that she would soon be with her “Bridegroom,” as “Jesus wished to give [her] the hope of going to see Him soon in heaven.” Again, as with Rostand’s Duke of Reichstadt, the truth of real life intrudes on interpretation: just as Rostand did not invent the fact that the duke had tuberculosis, it would take the most extreme cynicism to doubt that Thérèse’s first hemoptysis took place on Good Friday, whereas, for example, Francine’s death on All Saints’ Day, which carries a similar symbolic significance, is Murger’s artful contrivance. However, the sense that she made of her experience was clearly culturally determined, and she called attention in Story of a Soul to this episode as a turning point in her life and faith.Upon awakening, I thought immediately of the joyful thing that I had to learn, and so I went over to the window. I was able to see that I was not mistaken. Ah! my soul was filled with a great consolation; I was interiorly persuaded that Jesus, on the anniversary of His own death, wanted to have me hear His first call.[37]

The importance of the Good Friday episode cannot be overstated. The calendrical coincidence of receiving a sign of her impending death on the day commemorating the death of Christ does not exhaust its significance. Throughout her hagiography as well as within the structure of the autobiography, this 1896 incident stands out as a landmark in the progression of both her physical illness and her spiritual calling. This was the first crucial sign that death was relatively near, that Thérèse was materially different from her peers, and that her emotional idiosyncrasies (including her extreme sensitivity, her spoiled child’s tendency to cry easily, and her penchant for self-abnegation) had a spiritual basis and needed to be taken seriously. The fact that it was tuberculosis and the fact that it happened on Good Friday called forth a strong link between the physical and the spiritual and suggested that Thérèse was destined to be out of the ordinary.

The young nun understood her fate immediately as the fulfillment of a long-standing wish. “I never did ask God for the favor of dying young, but I have always hoped this be His will for me.” From that point on, the love of suffering that had been only one among her many distinguishing features became the focal point of her existence. “God has deigned to make me pass through many types of trials. I have suffered very much since I was on earth, but, if in my childhood I suffered with sadness, it is no longer in this way that I suffer. It is with joy and peace. I am truly happy to suffer.” And she continued to suffer, through the sleeplessness, coughing, weakness, and difficult breathing brought on by her illness. Shortly before her death, when someone asked her what had become of her “little life,” Thérèse answered, “My ‘little life’ is to suffer; that’s it!”[38] With the fulfillment of death so close, the only meaning left in her life came through the experience of suffering—and in properly depicting the joy of suffering through her writings.

When her strength finally gave out and she could no longer bring herself to write, Thérèse continued her teachings through her conversations with those around her in the convent. The Martin sisters apparently felt that Thérèse’s thoughts and writings would someday reach a wider audience (although nobody could have predicted at the time how wide the audience would become).[39] As a result, her last conversations were zealously recorded; some of them were published as part of her autobiography immediately after her death, and others were collected in separate publications. They carry her exaltation of suffering via tuberculosis through to the moment of her death. For example, on two separate occasions, Thérèse commented to her sister Pauline (then prioress of the convent) on the progressive emaciation of her hands, saying, “I’m becoming a skeleton already, and that pleases me,” and “Oh, what joy I experience when seeing myself consumed!” As with the literary heroines, it is the wasting away of the body that allows the spirit to flourish. Near the end, when Pauline spoke of her wish that death would come soon so as to spare her sister further suffering, Thérèse replied, “Yes, but you mustn’t say that, little Mother, because suffering is exactly what attracts me in life.”[40]

Thérèse’s conversations during her illness with her other sister and best friend, Céline, go even further toward explaining the relationship between physical suffering and religious fulfillment. Thérèse occasionally showed Céline her makeshift crachoir, a saucer in which she deposited her sputum. “Often she pointed to its rim with a sad little look that meant ‘I would have liked it to be up to there!’ ” Céline answered jealously, “Oh! it makes no difference whether it was little or much, the incident itself is a sign of your death.” Later, in the throes of late-stage tuberculosis, Thérèse experienced her pain as a trial sent by the devil and bore it accordingly. For a long time, her illness affected her right side in particular, she told Céline, until “God asked me if I wanted to suffer for you, and I immediately answered that I did.” “At the same instant, my left side was seized with an incredible pain. I’m suffering for you, and the devil doesn’t want it!”[41] A direct, one-to-one correspondence was established between spiritual desire and bodily symptom.

When the agony of tuberculosis made it difficult for Thérèse to breathe, she could not avoid expressing her pain. However, wanting to avoid at all costs giving the impression of complaining, she enlisted Céline in a poignant exchange to help her through the pain. Thérèse found herself repeating out loud, “I’m suffering,” and told her sister to answer her every repetition with “All the better”:

Thérèse:“Je souffre.” [I’m suffering.]

Céline:“Tant mieux.” [All the better.]

Thérèse:“Je souffre.”

Céline:“Tant mieux.”

Thérèse:“Je souffre.”

Céline:“Tant mieux.”

And so on, over and over.[42] There was not a trace of irony in Céline’s reply, or in Thérèse’s instruction to reply in this manner. She had come to desire suffering for its own sake, not just as a spiritual trial or as a sign of beatitude, although it was these things as well.

On her deathbed, her last words as recounted by her sisters maintained the exaltation of suffering until the end. Céline reported that Thérèse, in extreme pain, placed her arms in the form of a cross, and “our poor little martyr [looked like] a living image of Him.” She then spoke through the pain.

Pauline’s version differs slightly, adding an extra theological lesson to the passion of Saint Thérèse. After the phrase, “Never would I have believed it was possible to suffer so much! never, never!” Pauline reported that Thérèse added, “I cannot explain this except by the ardent desires I have had to save souls.” All accounts agree on her last words: “Oh! I wouldn’t want to suffer less!.…Oh! I love Him.…My God…I…love You!”[44] (The ellipses here indicate pauses rather than omissions.) The last phrase appears on many of her statues. This deathbed coda serves to reiterate the basic theme of Thérèse’s story: spiritual exaltation expresses itself through bodily suffering.I am…I am reduced.…No, I would have never believed one could suffer so much…never, never! O Mother, I no longer believe in death for me.…I believe only in suffering! Tomorrow, it will be still worse! Well, so much the better![43]

It is impossible to know whether Thérèse had read romantic novels or any of the literature that drew on the consumptive ideal of female suffering. She had certainly read the lives of the saints, in which suffering is similarly exalted. Whether her reproduction and reenactment of the ideal was conscious mimicry, subconscious role-playing, or merely coincidental resemblance makes little difference. Ultimately, what matters is that Thérèse learned how to be consumptive, whatever the sources of her inspiration. What she and the novelists had in common was the use of tuberculosis to express an age-old Christian attitude that exalted women’s suffering as sublime, spiritual, and potentially redemptive. On the most basic level, of course, the Christian theology of redemptive suffering dates back to the Passion of Christ and the special need of women for redemption to Eve and Original Sin. Although the suffering of Christ redeemed all of humanity, the uniquely fallen state of womanhood caused many in the church to view the periodic reenactment of the Passion on a worldly scale as the lot of all women. Consciously or not, Thérèse drew on this attitude and acted out in her real life (as interpreted and retold by her and by those around her) the redemptive suffering of her predecessors, saintly and fallen alike. The theme was, if not timeless, centuries old. The nineteenth-century innovation was the expression of redemption through the suffering of tuberculosis.

In her pathbreaking history of anorexia nervosa, Joan Jacobs Brumberg has established the young woman’s body as a nexus through which social, psychological, and religious forces have found expression throughout history. She has resisted the temptation to find in the “legendary asceticism” of medieval women such as Saint Catherine of Siena, or in the controversial “fasting girls” of the Victorian age, evidence of a transhistorical anorexic phenomenon that somehow explains present-day eating disorders. However, Brumberg has highlighted two particular historical patterns whose intersection may help to explain the appeal of Thérèse’s story. The Catholic ideology of suffering and bodily renunciation has for centuries associated the wasting away of young female bodies with a heightened state of spirituality.[45] Furthermore, in the late nineteenth century, the new hegemony of medical authority in determining the truth of the body did not prevent many believers from invoking the religious tradition of saintly or pious abstinence to explain the behavior of young women who refused food.[46] “Deprived of many worldly sources of empowerment,” Brumberg writes, “some Victorian girls chose to draw instead on the lingering tradition of anorexia mirabilis.”[47]

This cultural legacy deserves attention not for any insight into etiology (whether of anorexia or of tuberculosis) but rather for the effect of persistent attitudes on the popular reception of a phenomenon such as Thérèse. Although Brumberg’s nineteenth-century examples were drawn from Protestant cultures, France was also undergoing widespread secularization and wrestling with the question of women’s proper role in society. Thérèse’s wasting away from tuberculosis—or, more precisely, her portrayal and narration of her wasting away—paralleled the fasting girls’ wasting away from self-starvation and appealed to similar cultural attitudes. In both instances, the decay of the body signaled the blossoming of the spirit and renewed in the traditionally feminine realm of religion and spirituality a traditional feminine ideal.

In the end, all of the nineteenth-century consumptive heroines succumb to the same fatal and fateful malady. Thérèse is Marguerite Gauthier, in a sense: though superficially opposites and though one redeems all of humanity while the other redeems only her own fallen self, both are fundamentally redeeming womankind through death from tuberculosis. As Marguerite on stage, Sarah Bernhardt (herself the daughter of a courtesan) portrayed the dying woman as worthy of Mary Magdalene’s legacy, and theater critics praised her “ineffable sweetness,” professing almost to “see the halo of a saint upon her forehead.”[48]

Historians and other observers have made sense of these literary consumptives in various ways. Susan Sontag has denounced the tendency to romanticize and mystify disease, from tuberculosis to cancer and AIDS, as harmful and demoralizing to actual sick people. After carefully picking apart what she calls “the TB myth” and “the Romantic cult of the disease,” Sontag concludes, “It is…difficult to imagine how the reality of such a dreadful disease could be transformed so preposterously.”[49] This reaction raises several questions. Was, for example, Thérèse’s account of her own illness a preposterous transformation of a dreadful reality? Perhaps so. But understanding the historical and cultural setting within which Thérèse produced the true story of her life and death hardly makes it “difficult to imagine” how she could perceive tuberculosis in the way she did. In Sontag’s commendable effort to restore dignity to those who must contend with society’s hostile or perverse metaphors for their illnesses, she imagines a “reality” of disease (dreadful or otherwise) outside of history and culture. Indeed, what is difficult to imagine is how a culture could understand or conceive of illness without metaphor. In a less polemical vein, Claudine Herzlich and Janine Pierret have perceptively analyzed the extent to which tuberculosis allowed the “sick person” to emerge as a cultural category for the first time. Because it did not kill its victims instantly but instead allowed them to languish, visibly afflicted but able to live lives whose quality and significance were transformed, tuberculosis can be credited with “creating” this modern figure on a large scale.[50] This circumstance, along with the gradual bodily decay that is symptomatic of the disease, helps to explain why it was tuberculosis in particular (rather than any other disease) that came to be freighted with these meanings.

Several historians, however, have contended that the last half of the nineteenth century saw the eventual rejection of the consumptive literary ideal and its relegation to the marginal status of a quaint antique, to be replaced by the social vision of the fearsome and contagious cracheur de bacilles, or “spitter of bacilli.” Guillaume, for example, sees the romantic appropriation of tuberculosis under attack and losing its relevance from the 1860s on. Among other things, he calls Germinie Lacerteux and Madame Gervaisais (as well as Octave Mirbeau’s Journal d’une femme de chambre, which features tuberculosis only peripherally) protests against the “hypocrisy” that associated death with exaltation. While the Goncourts may have quarreled with certain aspects of the romantic/Christian ethos, in both novels, tuberculosis is still intimately linked to the characters’ spiritual condition. The progress of her disease measures Madame Gervaisais’s spiritual temperature, in a sense, and Germinie’s moral decline as well. Although it is true that Germinie’s life is depicted in more “social” terms (complete with alcoholism, poverty, and other forms of material degradation) than any of the other heroines except Fantine, her decline is still the “fatal” result of her tragic and impossible love, recalling in this respect La Dame aux camélias. In her employer’s view, moreover, Germinie redeems an entire class of “fallen” people with her death, in a socially didactic manner reminiscent of Fantine’s demise.

At the close of the century, when Thérèse composed her memoirs in Lisieux and Sarah Bernhardt played Marguerite and the Duke of Reichstadt to the cheers of theatergoers, an explosion of sociomedical literature had begun to represent tuberculosis as a social and national scourge, a political threat that demanded political action. Yet the consumptive ideal of suffering womanhood was alive and well. Inasmuch as it concerned the individual experience of illness and focused obsessively and nearly exclusively on women as victims of disease, this spiritual mode of understanding tuberculosis could hardly serve as a comprehensive explanation of such a widespread social phenomenon. However, the converse is also true. The proliferation of medical, social, and political meanings that came to be attached to tuberculosis in the Belle Epoque could not achieve totality or exclusivity as an explanation of this common, everyday killer.

The so-called War on Tuberculosis that arose from the new sociomedical discourse at the close of the century all but erased women from public discussion of the disease, offering them only marginal roles as facilitators of transmission to the male workers and soldiers on whose health the nation depended. It could not fully satisfy society’s need to make sense of the mysterious, dangerous, and threatening. Nor did it speak to the dominant cultural perception of woman’s nature as not only pathological but also dichotomous—irreconcilably torn between the poles of virtue and vice. Historians and literary critics have long stressed the myriad ways in which “women haunt[ed] the imagination of nineteenth-century authors.” As one critic has put it, the “woman as statue…muse and madonna…[was] raised up on a pedestal and sublimated.…[Authors] celebrate[d] this mysterious being, half-angel and half-devil, the oracle of Romanticism—woman.”[51] The elevation of the consumptive woman to the status of archetype and ideal expressed this same obsession. Like the strategists of the War on Tuberculosis, authors from Dumas to Rostand to Thérèse saw the disease as an affliction with both moral and physical dimensions. Unlike the sociomedical authorities, however, these authors looked to the experience of illness itself for answers. They found the fundamental truth of tuberculosis not in the expert knowledge of medicine or public health but in the emotional and spiritual essence of women and in the redemptive possibilities of suffering. Ultimately, the dominant etiology of tuberculosis could explain the meaning of disease but could not find meaning in disease. It could not fully supplant or displace the forms of meaning so powerfully evoked by the likes of Sarah Bernhardt and Thérèse of Lisieux.

Because of its frequency in society and its physically consuming quality, tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France came to stand in for all illnesses and occupied a cultural space in which it redeemed humanity in a diffuse, spiritual sense. In the essentialist cultural reading of tuberculosis, the disease expiated and explained, giving otherwise senseless or random suffering a meaning and a purpose (just as, in general, narrative imposes moral sense and causality on otherwise random sequences of events).[52] This reading arose when essentialism still predominated in medical circles, but it persisted long after the rise of contagionism. When Thérèse wrote in her diary and when Sarah played Marguerite or the Eaglet, fiction and nonfiction converged, and the literal truth of the particular stories became irrelevant. The underlying tale of redemption through slow, wasting—and feminine—suffering and death resonated in churches and theaters alike. Individual sins and human frailty demanded expiation, and frailty’s name was woman. Throughout the century, tuberculosis gave that spiritual redemption a material shape.

Around 1900, the suffering of Thérèse Martin in the convent or of Sarah Bernhardt on stage could be read as an alternative way of understanding tuberculosis. A few decades earlier, before the final victories of contagionism, essentialism, both literary and medical, was the only established means of explaining the disease. Hygienists had begun to consider tuberculosis a social phenomenon in its incidence, but etiologically and in other respects, it remained largely a matter of personal experience and circumstance. By century’s end, the disease would become not just a social problem but a national crisis as well. The following chapters discuss these developments in the realms of medicine and politics during the Belle Epoque.

Notes

1. Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, The Divine Sarah: A Life of Sarah Bernhardt (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 3–4, 33, 276.

2. Guy Gaucher, Histoire d’une vie: Thérèse Martin (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1988), 227–228.

3. The most cogent discussion of narrative as a representational strategy is Hayden White’s The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), esp. 1–25. See also chap. 3, below.

4. This choice is somewhat narrow, and certainly open to criticism. These and other literary works are discussed in relation to tuberculosis in Guillaume, Du désespoir au salut, 81–105 (“Phtisie et sensibilité romantique”); in René and Jean Dubos, The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society, 2d ed. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987), 44–66 (“Consumption and the Romantic Age”); and in Grellet and Kruse, Histoires de la tuberculose. This selection is not meant to convey a judgment of canonical status or of literary quality. Rather, I have tried to cover (chronologically) most of the nineteenth century and to call on familiar literary and artistic works that exemplify certain broad trends and themes in French culture and also address social issues (such as prostitution, class and gender relations, labor, and poverty). In addition, all of these works refer specifically to tuberculosis (rather than vaguely to some unspecified chronic illness, as do some of the works discussed by Grellet and Kruse), and two of them provided Sarah Bernhardt with some of her most famous stage moments; for reasons discussed below, I see Bernhardt as personifying in certain ways the nineteenth-century consumptive ideal.

5. See chap. 1, above.

6. See, for example, Guillaume, Du désespoir au salut, 81–105, and Grellet and Kruse, Histoires de la tuberculose, 133–142.

7. Alexandre Dumas fils, La Dame aux camélias [1848] (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1967).

8. Ibid., 86.

9. Ibid., 93, 101.

10. Ibid., 244.

11. Carlos M. Noël, Les Idées sociales dans le théâtre de A. Dumas fils (Paris: Albert Messein, 1912), 42–43, 47.

12. Roger J. B. Clark, introduction to Dumas fils, La Dame aux camélias (London: Oxford University Press, 1972), 44–45.

13. Henry Murger, Scènes de la vie de bohème [1851] (Paris: Gallimard, 1988).

14. In the opera version, La Bohème (1896), the character of Francine is folded into that of Mimi, and Mimi’s death from tuberculosis is dramatized to such an extent that it plays a much more prominent part in the opera than does Francine’s in the novel; as a result, later opera audiences perceive the death originally intended for Francine as more central to the drama than it is in Murger’s text.

15. Murger, Scènes de la vie de bohème, 216–217.

16. See chap. 1, above.

17. Murger, Scènes de la vie de bohème, 281–282.

18. Ibid., 283–284, 287–289, 291.

19. Victor Hugo, Les Misérables [1862], trans. Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee (New York: New American Library, 1987), 187.

20. Ibid., 182, 200–201, 257, 283–284, 294.

21. Jane P. Tompkins, “Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Politics of Literary History,” in Elaine Showalter, ed., The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature, and Theory (New York: Pantheon, 1985), 81–104; quotation at 85.

22. Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, Germinie Lacerteux [1864] (Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1982).

23. Ibid., 101–102.

24. Ibid., 142, 164.

25. Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, Madame Gervaisais [1869] (Paris: Gallimard, 1982), 93, 241.

26. Ibid., 209–210, 228.

27. Ibid., 241.

28. Elaine Aston, Sarah Bernhardt: A French Actress on the English Stage (Oxford: Berg, 1989), 122.

29. Edmond Rostand, L’Aiglon [1900] (Paris: Gallimard, 1986), 226.

30. Ibid., 90, 139.

31. Ibid., 231–236.

32. Ibid., 360–361.

33. Ibid., 360–361, 429 n. 109.

34. Among the best biographies of Thérèse are Gaucher, Histoire d’une vie: Thérèse Martin; Monica Furlong, Thérèse of Lisieux (New York: Pantheon, 1987); Jean-François Six, Thérèse de Lisieux au Carmel (Paris: Seuil, 1973); and René Laurentin, Thérèse de Lisieux: Mythes et réalité (Paris: Beauchesne, 1972).

35. Gérard Cholvy and Yves-Marie Hilaire, Histoire religieuse de la France contemporaine, 1880–1930 (Toulouse: Privat, 1986), 142, 325–329; Furlong, Thérèse of Lisieux, 124–128; Gaucher, Histoire d’une vie, 231–234.

36. See, for example, Story of a Soul, 157–159, 211; Furlong, Thérèse of Lisieux, 85–86.

37. Story of a Soul, 210–211.

38. Ibid., 210, 215, 265.

39. Furlong, Thérèse of Lisieux, 114–115.

40. John Clarke, ed., St. Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Last Conversations(Washington, D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1977), 80, 98, 108.

41. Ibid., 217, 224. (Emphasis in original.)

42. Ibid., 224. This scene is rendered brilliantly in the film Thérèse, directed by Alain Cavalier (UGC Films, 1986).

43. Clarke, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, 229–230. (Ellipses in original.)

44. Ibid., 205, 230. (Ellipses in original.)

45. Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 41–47.

46. Ibid., 61–100.

47. Ibid., 100.

48. Aston, Sarah Bernhardt, 48.

49. Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978), 34–35; see also her AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989).

50. Claudine Herzlich and Janine Pierret, Malades d’hier, malades d’aujourd’hui (Paris: Payot, 1984), chap. 2, “De la phtisie à la tuberculose,” 48–64.

51. Nicole Priollaud, “Avertissement,” in Priollaud, ed., La Femme au 19e siècle (Paris: Levi/Messinger, 1983), 9. To a great extent, this was an international cultural phenomenon; in Anglo-Saxon cultures, as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar have noted, society told women “that if they d[id] not behave like angels they must be monsters.” In fact, they argue, the understanding of womanhood as inherently pathological so thoroughly penetrated society that, in addition to training girls in “docility, submissiveness, self-lessness…[and] renunciation…nineteenth-century culture seems to have actually admonished women to be ill.” Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 53–54. (Emphasis in original.)

52. White, The Content of the Form, 1–25.