2. Revolt and Religious Reformation in the World of Charles V

First of all, the gospel does not cause rebellions and uproars, because it tells of Christ, the promised Messiah, whose words and life teach nothing but love, peace, patience, and unity. And all who believe in this Christ become loving, peaceful, patient, and one in spirit. This is the basis of all the articles of the peasants.…to hear the gospel and to live accordingly.…

Second, it surely follows that the peasants, whose articles demand this gospel as their doctrine and rule of life, cannot be called “disobedient” or “rebellious.” For if God deigns to hear the peasants’ earnest plea that they may be permitted to live according to his word, who will dare deny his will?

You are robbing the government of its power and even of its authority—yea everything it has, for what sustains the government once it has lost its power?

In the midst of what was surely one of the most dramatic popular political challenges of the sixteenth century, the representatives of three large peasant armies assembled at the town of Memmingen and drew up “The Twelve Articles of the Peasantry of Swabia” in late February or early March 1525. The articles not only listed specific grievances and demands that reflected a profound crisis of agrarian society and religious authority but also expressed a set of principles that were at once revolutionary and capable of encompassing the hopes and aspirations of a broad coalition of political subjects throughout southern Germany. Thus, the third article joined an attack on serfdom with an alternative vision of the political and social future: “It has until now been the custom for the lords to own us as their property. This is deplorable, for Christ redeemed and bought us all with his precious blood, the lowliest shepherd as well as the greatest lord, with no exceptions. Thus the Bible proves that we are free and want to be free” (Blickle 1981: 197). In this sense, Martin Luther, whose theological challenge to the established Church had inspired and emboldened the peasant leaders, was surely right in arguing that the peasants’ demands threatened the established political order. The peasants’ protestations to the contrary notwithstanding—“Not that we want to be utterly free and subject to no authority at all,” the third article continued—this most famous of the manifestos associated with the Revolution of 1525 promised to transform Swabian society according to the lofty principles of “godly law.”

At the time the peasant leaders were assembled in Memmingen, they can be said to have enjoyed a brief military advantage over their opponents; for the armies of the imperial Swabian League were temporarily distracted by other, more traditional military challenges. Once they turned their attention to the massive insurrections, not only in Swabia but in Franconia and Thuringia as well, the established rulers and their more practiced and professional armies easily defeated the popular challengers, sometimes even without a fight. By the end of the year, virtually all of the peasant insurrections had been subdued and a massive repression had begun throughout the area. Indeed, never again would this region be rocked by popular insurrection on such a massive scale.

Because of the well-deserved fame of the Revolution of 1525, not to mention the explosion of revolutionary religious enthusiasm at the city of Münster ten years later, it is tempting to identify popular religion with popular rebellion in the early years of the sixteenth century. As it happened, however, popular movements for the reformation of religious belief and practice took a variety of forms short of open rebellion—from the submission of humble petitions to the formation of secret “conventicles.” Moreover, “successful” reformations were as often magisterial as popular in origin. Thus the political dynamics of the English and Scandinavian reformations, where rulers actively aligned themselves with religious reform movements, were strikingly different in the 1530s and beyond. In England, for example, in the absence of massive popular demands for religious change, the king took the initiative to separate the Church from Rome and to introduce modest changes in the ritual life and dogma of the Church of which he now claimed to be the head. The most obvious popular response in 1536 was an abortive rebellion in Lincolnshire and what has come to be known as the Pilgrimage of Grace.

The leaders of these English movements, like the leaders of the German revolution, put together broad but immensely fragile coalitions that could not withstand the counterchallenges of the king and his allies. Also like their German predecessors, they articulated an eclectic set of grievances and published specific demands regarding the regulation of public affairs and social relations in an agrarian society. But in the English case, instead of demanding reform or liturgical innovation, the leaders of a broadly based popular mobilization were emphatically demanding the restoration of the established Roman church and the religious practices associated with it. Meeting at Pontefract in December 1536, for example, they demanded vigorous actions against “the heresies of Luther,” among others, and insisted that “the privlages and rights of the church…be confirmed by acte of parliament, and prestes not suffre by sourde onless he be disgrecid” (Fletcher 1983: 111–112). In response, a publicist for the king asked rhetorically,

Despite their obviously different demands with regard to the reformation of religious practice and belief, then, the rebels in both Germany and England were seen by contemporaries to threaten the foundations of established authority and to promise a fundamental reorientation of the essential relationships between rulers and their subjects.When every man wyll rule, who shall obeye?…No, no, take welthe by the hande, and say farewell welth, where lust is lyked, and lawe refused, where uppe is sette downe, and downe sette uppe: An order, and order muste be hadde, and a waye founde that they rule that beste can, they be ruled, that mooste it becommeth so to be. (Ibid., 112)

Such was the nature of the Reformation era in Europe: though dissenting theologians like Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and Jean Calvin may not have intended it, their direct challenges to the authority of the established Church intersected with and had profound implications for the interactions of subjects and rulers more generally. As Euan Cameron sums up the process in his recent survey,

Consequently, the sixteenth-century Reformation was a unique transition in the history of Western Christendom in the sense that it laid the foundations for divergent paths of closely linked religious and political development that endured throughout the early modern period.Politically active laymen, not (at first) political rulers with axes to grind, but rather ordinary, moderately prosperous householders, took up the reformers’ protests, identified them (perhaps mistakenly) as their own, and pressed them upon their governors. This blending and coalition—of reformers’ protests and laymen’s political ambitions—is the essence of the Reformation. It turned the reformers’ movement into a new form of religious dissent.…[I]t promoted a new pattern of worship and belief, publicly preached and acknowledged, which also formed the basis of new religious institutions for all of society, within the whole community, region, or nation concerned. (1991: 2; emphasis in original)

This chapter focuses on popular political action during the first act of the European Reformation, especially within the composite domain of Charles V of Habsburg. The consummate late medieval dynastic prince, Charles combined a collection of patrimonial lordships in the prosperous commercial centers of the Low Countries with a composite kingship in Iberia, created just half a century earlier by the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon with Isabella of Castile, and the emperorship of the vast German-Roman Empire in central Europe. It was within or on the fringes of Charles’s imperial domain, to which he was elected in 1519, that popular enthusiasm for religious reform was first concentrated in the 1520s; and as I will argue, popular engagement in the essentially political process of religious reformation took a variety of forms in Germany—including, of course, the Revolution of 1525—which precipitated, by midcentury, a political and religious settlement that extinguished Charles’s unambiguous claim to cultural or religious sovereignty over the whole of his empire. To underscore the significance of these political and religious conflicts for the subsequent history of central Europe, this chapter also sets the German Reformation in the larger comparative context of the Scandinavian and English reformations where, by contrast, popular engagement in the reformation process helped to consolidate princely claims to cultural sovereignty. I begin, however, with a brief examination of the first major challenge to Charles’s sovereignty—the Comunero Revolt of 1520–1521 in Castile, at the heart of his Iberian domain—for two principal reasons: on the one hand, the Comunero Revolt did not directly invoke the question of religious authority and thus reminds us that not all sixteenth-century conflict was associated with or inspired by the challenges of Protestant theology; on the other hand, the Comunero Revolt involved all the important political actors within a composite state—local rulers and ordinary political subjects as well as national claimants to power—and thus illustrates clearly the long-term significance of the alternative alignments among them.

| • | • | • |

Communes and Comuneros in Castile

On May 30, 1520, just ten days after Charles I of Castile had left Spain to assume his new role as Charles V in the German-Roman Empire, an unruly collection of artisans, mainly textile workers in the woolen industry, invaded the city hall of Segovia and seized Rodrigo de Tordesillas, one of the city’s official delegates to the recent meeting of the Cortes that had been summoned by the king at Santiago. Incensed by the apparently boundless fiscal demands of their young monarch—demands that seemed to support little more than Charles’s dynastic ambitions in Germany—the crowd brought their defenseless victim, who was condemned for having betrayed local interests, first to the city jail and eventually to the place of public executions where they hanged him. Stephen Haliczer describes the aftermath:

In the next four months, delegates of the city of Segovia joined delegates from no less than eighteen other revolutionary cities in Castile to constitute the Sacred League (Sancta Junta), which claimed power as the sole legitimate government of Castile in place of Charles’s regency government, which had quickly collapsed in the face of this powerful wave of urban insurrection.Tordesilla’s murder was the signal for a wholesale attack on the representatives of royal government in the city of Segovia. The corregidor (royal official of the town), his lieutenants, and police officials were stripped of their offices and forced to flee. New officials were appointed by a revolutionary committee composed of members of the city council, delegates from the cathedral chapter, and parish representatives. The Comunero revolution had begun. (1981: 3)

In many respects, the revolution of the Sacred League, also known as the Comunero Revolt, represented a classic form of local resistance to an aggressive dynast (see Blockmans 1988). The Sacred League was a coalition of many, though not all, of the leading cities of the Kingdom of Castile, whose sovereignty Charles had seized from his own apparently insane mother in 1516. Collectively, the members of the league, whose efforts were welcomed by the deposed and psychologically unstable Queen Juana, sought to abolish the alcabala (a general tax on commerce), to reduce the power of the king, and to transform the Cortes, in which they were represented, into the primary institution of the state (cf. Bonney 1991; Lynch 1991). The political demands of the Comuneros may thus be considered fundamentally revolutionary in the sense that they were exclusive of the claims to political sovereignty that Charles was making as king; to accept the rebels’ claims, indeed, would be to transform fundamentally the structure of political authority in Castile.

As the events in Segovia suggest, however, the Comuneros’ opposition to the royal government involved as well a political realignment within the local community as officials appointed by and oriented to the royal administration were replaced by others who were more responsive to local demands and who were selected by, among others, the representatives of popular parish assemblies. And once they joined the Sacred League, the leaders of the rebellious communes of Castile deepened their political orientation toward ordinary political actors within the urban community by building the league’s defenses on the basis of urban militias mobilized and recruited locally. There is certainly more than a little historical irony in the fact that the Comunero Revolution adopted the defensive form of a sacred league because less than fifty years earlier, in 1476, Queen Isabella had encouraged the chartered cities in her Castilian domain to act as a sacred league—the Sancta Hermandad—and to raise urban militias to maintain public order and support her in her efforts to tame the powerful Castilian nobility. Though the league of cities had been disbanded in 1498, when the Crown once again shifted its dynastic policy toward dependence on the rural nobility, the lessons of this earlier political process had clearly not been lost on the municipalities involved. To deploy the civic militia in opposition to the new king, however, was to create a new kind of internal political dynamic that also entailed the creation of independent municipal councils, or “communes” (hence the name “Comunero”). For the duration of the revolt, at least, the local rulers of the rebellious cities were to be fundamentally dependent on the approval and support of their subjects (see fig. 2a).

In the late summer of 1520, the political situation in Castile became even more volatile and threatening to the established political order when political disturbances in the countryside began to threaten noble landlords as well as the king. In the village of Dueñas, not far from the capital of Valladolid, for example, rebellious peasants, spurred on by a group of radical monks, rejected the lordship of the local count of Buendía and replaced the count’s officials with others chosen by a popular assembly. The rebels then proceeded to encourage rebellion in other parts of the count’s local domain, and they seized nearby fortresses belonging to the count (Haliczer 1981: 185). In October, there were also a number of antiseigneurial revolts in Tierra de Campos, where eventually some twenty-seven localities sent representatives to a rebel league that met at Palencia. In principle, the peasant revolts might have offered the urban Comuneros potentially important allies in their fight against the king and the powerful nobility with which he was allied, but in the end the Comuneros’ failure to take advantage or ally themselves with the rising tide of rural discontent exposed the limits of this sort of urban resistance to aggressive dynasts. The fact is that the political bargains by which dynastic princes typically constructed their composite states created local privileges that distinguished one piece of the composite from another. Indeed, the extent to which municipal charters privileged urban communes over their rural hinterlands militated against urban-rural alliances vis-à-vis a common enemy like an aggressive dynast or his noble allies; and in this case, the extent to which the Comuneros’ militias indiscriminately exploited defenseless country folk in the course of their military campaigns made such alliances extremely unlikely.

Thus the rebellious cities’ political isolation in an essentially rural environment underscored the fragility of their revolutionary coalition. At first, the urban militias were able to hold their own against the royal government’s feeble counteroffensive, but inasmuch as the rural rebellions served as a serious warning to the nobility of the obvious dangers of a general disintegration of royal authority to preserve peace and guarantee their privileges in the countryside, the king’s regent was soon to be bailed out by the combined forces of the nobility’s private armies. The first serious blow to the Comuneros came in December 1520 when a royalist army sacked their lightly defended capital at the town of Tordesillas and captured thirteen league delegates. The league was quickly reconstituted at Valladolid, though it was pared down to eleven cities, and briefly rallied by capturing all of Tierra de Campos. But in the spring of 1521, the military struggle finally turned in favor of the king’s forces, and in a decisive battle at Villalar, the viceroy’s infantry defeated the Comuneros’ exhausted soldiers. On April 24, 1521, the three principal Comunero military leaders were condemned to death, and although the city of Toledo held out until February 1522, the revolution of the Sacred League had come to an end.

Though the Comuneros were thus defeated militarily, their resistance to the aggressive dynasticism of Charles of Habsburg was not without result. Indeed, Haliczer describes the postrevolutionary political situation in Castile as follows: “Charles did not return to a cowed and subdued Castile ready for unquestioning obedience; instead, it was a subdued king who came back [from Germany] to a restive and hostile kingdom in 1522 to face the task of rebuilding support for the monarchy” (1981: 207). From this perspective it is not surprising that the cities of Castile gained some important concessions from the king following their defeat: a system of tax collection more favorable to the cities; a reorganization of the central government along lines favored by the cities; and a Cortes decidedly more receptive to the special grievances of the cities. Even the government’s repression may be considered light because many of those who had been excluded from a general pardon in 1522 were eventually pardoned; in the end, only twenty-three persons were executed for their resistance to the monarchy.

Still, in the long run, the most important political development from the point of view of the ordinary citizens of the Castilian towns is that the Crown began channeling its considerable patronage to municipal representatives in the Cortes. In short, a political alignment of ordinary people with their local rulers—which underwrote a local consolidation of power vis-à-vis the king for the duration of the revolt (see fig. 2a)—was replaced by an alignment, lubricated by royal patronage, between local magistrates and the king—which consolidated the power of the elites vis-à-vis their local subjects (see fig. 2b). For the king, the not inconsiderable result was that the municipal representatives to the Cortes would henceforth be more likely to grant him his fiscal demands, but this kind of favorable treatment also helped to create a privileged set of urban oligarchs who were clearly more alienated from their political subjects than their predecessors had been during their defense of the local community in the face of monarchical consolidation. Indeed, effective municipal resistance to monarchical consolidation inevitably depended on coalitions of a variety of sorts: between municipal rulers and their subject populations; among cities with often disparate economic and political interests; or between rebels on opposite sides of the legal, social, cultural, and sometimes even physical barriers that differentiated cities from their rural hinterlands. In the aftermath of the Comunero Revolt, then, it can be said that to the extent that royal policies privileged cities over their hinterlands and oligarchs over their urban subjects, they helped to ensure that an urban revolt of this magnitude would not be repeated in Castile.

| • | • | • |

Revolution and Religious Reform in Germany and Switzerland

In the early years of his political career, then, Charles V was challenged in quick succession by revolts in both Iberia and Germany. At the other pole of his far-flung accumulation of political territory—in the Austrian Habsburg patrimonial domain and more generally in the diverse territories of the empire—the patterns of political contestation that Charles V faced were, at first blush, far more complex and confusing, and not only because German politics were infused by religious controversy and enthusiasm. The extreme segmentation of political authority in the German-Roman Empire—both geographically in hundreds of more or less self-regulating political units and constitutionally in the welter of overlapping and often competing hierarchies that characterized the governing institutions of the empire—preserved an immense variety of political spaces in which ordinary people could, and in fact did, initiate their own challenges to those who claimed authority over them.[1] Not surprisingly, then, by comparison with the Comunero Revolt, the Revolution of 1525 in Germany was both more diffuse and, at bottom, less of a direct threat to Charles’s political sovereignty because it was most often directed at his political subordinates.[2]

This “revolution of the common man,” as Peter Blickle has described it, was predicated on the creation of relatively loose and informal coalitions among locally mobilized peasant groups as well as artisans and common laborers on the fringes of southern Germany’s many cities and in the adjoining cantons of the Swiss Confederation. What brought them together in a common cause was the ideal of a community-based church demanding faithful preaching of the “pure gospel” and a “godly law” that applied to rulers and subjects alike (Blickle 1981, 1992). Though it is tempting, in retrospect, to emphasize the breadth of the coalitions, to highlight the enormous geographic spread of the insurrection, and even to speak of the whole complex of events in the singular form of the term “revolution,” it is important for our purposes to disaggregate this historical composite and to locate the political actions of ordinary people within their respective political spaces.

The basic, constituent unit of popular insurrection in sixteenth-century Europe, as many scholars have suggested, was the local community—whether that of the rural village or that of the chartered town—and the Revolution of 1525 was no exception (cf. Sabean 1976). As it happened, the German peasant mobilization began at Stühlingen in the Hegau in June 1524 when several hundred tenants of Count Siegmund von Lupfen rebelled against the exactions imposed by their lord. They chose as their leader a former mercenary, Hans Müller, and quickly worked out an alliance with the nearby town of Waldshut, where a popular preacher named Balthasar Hubmaier had galvanized opposition to the town’s more distant Austrian overlord. When these in turn allied with the city of Zürich, the authorities were forced to play for time while the peasants of Stühlingen, where it had all started, submitted their grievances formally to the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court) for adjudication within the legal framework of the empire. Meanwhile, the rebel forces led by Müller forced the capitulation of Freiburg-im-Breisgau.[3] Finally in 1525, following inconclusive talks between the rebels and the Austrian officials, the revolt burned itself out.

Similar scenarios—albeit often with more violent endings—were played out in Swabia, Franconia, Thuringia, and the Tyrol, as local resistance to lordly, princely, or imperial exactions aggregated under the leadership of skilled soldiers, urban artisans and lawyers, or popular preachers. The soldiers and their military skills were important to such movements because as local resistance fused into regional insurrection, the most likely response from established rulers was a military campaign.[4] The artisans and lawyers were important because they helped to bridge the political and social gap between city and countryside. The preachers were important because their radical religious populism served powerfully to unite otherwise very diverse people in a common cause: the cause of “godly justice.” [5] Still, the most basic political interaction was between a variety of local rulers and their immediate subjects—rulers and subjects as various as the many fragments of sovereignty that dotted central and southern Germany, including many parts of modern-day Switzerland and Austria. The individual stories of the many popular actors in this complex drama converged on the theme of opposition to what were considered the illegitimate or excessive exactions of rulers. Undoubtedly the most common, but by the same token the least visible, form of this opposition was simple evasion, often by individuals but sometimes collectively in the form of rent strikes or refusals to pay the tithe. But in the previous hundred years, this basic dynamic had spilled over with increasing frequency into larger collective actions in the form of violent rebellions. In the first half of the fifteenth century there were seven such regional revolts; in the second half of the fifteenth century, fourteen. In the first twenty-five years of the sixteenth century, there were no less than eighteen (Blickle 1979).

In this sense, the scenario of 1524–1525 was well rehearsed; the claims, the claim makers, and the basic forms of claim making must at least have been familiar to those involved. What was truly unprecedented was the magnitude of the historical convergence: in all, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people served at one time or another in the “peasant” armies; as many as 130,000 may have died in the fighting or in the subsequent repression; virtually all areas of central and southern Germany, with the notable exception of Bavaria, were touched by the conflicts.[6] We must be careful, however, neither to overestimate nor to underestimate the achievement of the rebels. The convergence of so many discrete rebel movements was far from complete. Though they clustered in a very concentrated period and shared many essential characteristics, the regional uprisings were not directly connected with one another; nor were they well integrated on a regional scale (in both Swabia and Franconia, for example, there were multiple armies under discrete leadership). Nevertheless, these popular mobilizations outstripped, for a time at least, the ability of established rulers to repress them—not only individual lords and princes, but even imperial aggregations like the Swabian League.

In this regard, we cannot but be impressed by the leaders of the movements, often of relatively humble origin themselves, who organized massive armies within the narrow limitations of an agrarian society. Because so many were active in agriculture, the soldiers in the rebel armies often were allowed to serve for only short periods, so that each would in turn be able to tend to his own crops at regular intervals.[7] Besides fielding massive armies, the movements’ leaders frequently brought together deliberative “peasant” assemblies, negotiated informal alliances with other rebels across existing territorial boundaries, and produced manifestos like that of the peasants of Swabia. From some three hundred grievance lists, the authors of the Twelve Articles not only distilled a common list of grievances regarding the disposition of common resources, the collection of tithes, and the imposition of unpaid labor services, they also articulated a vision of the future that could inspire and unite very diverse people across a broad terrain. In a “godly” society, indeed, ordinary people would be both personally “free” (see article 3, quoted above) and collectively in charge of their religious welfare (see article 1 by which the local community asserts the right to choose its own pastor); rulers, meanwhile, would be clearly limited by the precepts of divine justice.[8] The “Revolution” of 1525 may in this regard be considered the most dramatic example of the way in which the sixteenth-century Reformation provided ordinary Europeans with, to borrow Euan Cameron’s expression, “their first lessons in political commitment to a universal ideology” (1991: 422).

Still, on the face of it, this broad challenge to the political and religious establishment was, like the Comunero Revolt, a failure: in the immediate sense that the many armies of the various movements either gave up without a fight or were soundly defeated in lopsided battles; and in the larger sense that the leaders of the movement were, on the whole, unable to institutionalize their radical religious reforms and to realize their populist visions of a more egalitarian “godly” society. In the absence of major defections from the ranks of the political elites or significant outside support, this massive popular mobilization gave way to the firm consolidation of elite control in the German countryside (see fig. 2b). This is not to say, however, that the peasant uprisings in southern and central Germany were completely unsuccessful. As recent research has shown, in some areas the movements achieved both specific concessions with regard to some of their immediate demands and long-term reforms of the political and judicial systems. In the long run, the judicial changes in particular had far-reaching implications for the interactions of rulers and subjects within the fragmented jurisdictions of the German Empire because they legitimated the formal appeal of popular grievances to imperial authorities (Schulze 1984; Trossbach 1987).

The failure of the Revolution of 1525 to dislodge the established political order within the empire was also, of course, relative to the boundaries of the empire itself. Just beyond the effective reach of imperial authorities—in the complex jurisdictions of the Swiss Confederation—the process of religious reformation intersected with the process of revolutionary conflict in a rather different sense that opened greater opportunities for the success of religious reformations in the countryside (Peyer 1978; Blickle 1992; Gordon 1992; Greyerz 1994). There the Oath Confederation (Eidgenossenschaft) of just three forested mountain districts or cantons had first been formed as a common defense against feudal domination already in the late thirteenth century, and it went through several phases of crisis and expansion before its armed citizens, in one of their most heroic moments, defeated the formidable armies of Emperor Maximilian I in 1499 and thereby seemed to secure their de facto independence and the principle of communal self-governance for the foreseeable future. Within the diverse territories of the confederation, then, the more or less accomplished fact of revolution ensured that rural communities stood in a rather different relationship to the political process of religious reformation (Bonjour, Offler, and Potter 1952; Luck 1985).

In the large city-state cantons of Zürich and Bern, for example, municipal authorities formally adopted Protestant worship in the 1520s and began actively promoting the reformation of religion in their rural hinterlands as well. In the smaller core cantons of Luzern, Uri, Schwytz, and Unterwalden, by contrast, Protestantism made few inroads, and local authorities stalwartly defended the established religious order (cf. Blickle 1992: 167). In several remarkable situations, however, the question of religious orientation—the choice for or against the new evangelical preaching and experimentation in worship—was left to individual rural communities within a canton. In 1528, the city-state of Bern, as part of the process of introducing Protestant worship, conducted a systematic consultation (Ämterbefragung) of the rural population which, as expected by its organizers, produced a handsome majority—though by no means unanimous consent—for the Reformation. Meanwhile, in the rural cantons of Appenzell and Glarus, Landesgemeinden (general meetings of all full citizens) decided that each individual community should have the right to choose for or against the religious reforms; in both cases, the subsequent decision-making process left the cantons religiously divided (Fischer, Schläpfer, and Stark 1964; Wick 1982). A similar pattern of religious division as a consequence of local decision making emerged to the southeast of the confederation in Graubünen (Blickle 1992; Head 1997). But what is particularly instructive about these Swiss examples is that when an essentially completed process of political revolution gave them the truly extraordinary opportunity to choose either for or against the Reformation, they did both: The various rural communities of Switzerland chose both for and against the project of religious reform and not necessarily one or the other.

| • | • | • |

Patterns of Urban Reformation

As it unfolded in southern Germany and Switzerland, the process of religious reformation intersected only partially and imperfectly with the process of revolutionary political conflict. Only rarely did successful challenges to the cultural dominance of the Roman Catholic church entail simultaneous and direct challenges to the sovereignty of established political regimes, but when they did, they were most likely to take place within the relatively concentrated political spaces of self-governing cities. These self-governing cities were scattered throughout Europe’s urban core from northern Italy[9] to the Low Countries and the Baltic coast, but within the empire alone there were some 80 imperial “free” cities, subordinate only to the emperor, and more than 2,000 territorial cities, chartered by territorial lords and princes. Only a few of these were large population centers, and many had fewer than a thousand inhabitants. Regardless of size, however, the chartered municipalities were free to conduct their own affairs unless and until their “sovereigns” chose to intervene. It is thus within cities that we can see with special clarity the political processes of the sixteenth-century religious reformation.

The political process of religious reformation, including the active participation of ordinary people, was well under way within many German communities before the events of 1525. This process, in the broadest sense, began with the rapid diffusion of Martin Luther’s new, evangelical theology by means of cheaply published pamphlets and broadsides, written for the most part by and for a well-educated reforming clergy. Vigorous popular engagement was usually predicated not so much on the spread of printed material as on the success of evangelical preaching. The preachers might be established religious leaders within their communities or newly trained converts, insiders or outsiders, but where they became effective leaders, they went beyond mere criticism of the established Church to suggest a variety of concrete means by which their audiences might identify themselves with the movement and become actively involved in the process of spiritual renewal (cf. Wuthnow 1989). The popular response, in turn, took a variety of forms that ranged from presumably private decisions to withdraw from active participation in the established ritual life of the Church—especially to stay away from the confessional and the Mass—to much more public and demonstrative acts like the mocking of priests and the desecration of sacred images (see, e.g., Wandel 1992, 1995). In many places, popular movements for reform were led by guildsmen—artisans as well as petty merchants—who organized formal petitions urging municipal authorities to intervene: to mandate “biblical” preaching, to reform or abolish the Mass, to call evangelical preachers, to establish a “common chest” for poor relief, or to expel priests.

At almost any point, this interaction between preachers and people might become a problem for civil authorities. Urban magistrates were officially charged with the maintenance of public order within their circumscribed domains, yet having limited coercive resources at their disposal, they depended to a considerable degree on popular assent, without which daily governance would not be possible. Given Charles V’s zealous defense of papal orthodoxy and the imperial condemnation of Luther’s teachings at the Diet of Worms in 1521, then, even the passive toleration of radical preaching might be considered an act of insubordination, but any attempt to discipline, expel, or otherwise limit popular preachers risked opposition from within the community. Caught between their nominal, often distant sovereigns and their immediate subjects, most civic leaders simply tried to buy time—to stay neutral—but the informal coalition between reforming preachers and an active laity often proved irresistible. In many cases the city councils started out as the reluctant arbiters of growing conflicts over religious practice and belief, but in the end it was they who enacted the essential reforms, not only by mandating changes in religious practice and changing ecclesiastical personnel but also by appropriating Church property for the use of the community.

In Augsburg in the early 1520s, for example, civic authorities obstructed the local bishop’s efforts to discipline Lutheran preachers and published, but did not enforce, imperial mandates concerning religion; by the same token, however, they took no steps to appoint evangelical preachers, to establish religious reforms, or to attack the Catholic church. This middle course proved untenable in the summer of 1524, when a radical Franciscan monk gained a popular following in the city; in the words of one unsympathetic chronicler,

When the preacher Hans Schilling was surreptitiously removed from the city, a large crowd of perhaps two thousand of his supporters besieged the town hall, and the municipal council was forced to promise to recall Schilling. After the crowd had gone home, however, the council sent for six hundred mercenaries, imposed martial law, and punished the leaders of the crowd. The council was nevertheless forced to call a preacher to the post at the Franciscan church who was acceptable to the parishioners—as it happened, a Zwinglian (rather than a Lutheran) who was a zealous advocate of religious reform. In the end, then, the civic authorities were forced, for the sake of domestic peace, to appoint an evangelical preacher against their original wishes and in defiance of both the bishop and the emperor (Broadhead 1979, 1980).He preached critically of the spiritual and temporal authorities and against the customs of the Church. He also preached frivolously about the Sacraments and went around flippantly with the Holy Sacrament.…[H]e spoke in his sermons as if all things should be held in common. With these and similar sermons the monk attracted many people, indeed the majority of the populace. (Quoted in Broadhead 1979: 82)

Such interactions involving preachers, priests, magistrates, bishops, “princes,” and ordinary people were common in the cities of the empire both before and after the Revolution of 1525. Typically, they involved only short-term confrontations and only incremental changes; in fact, in Augsburg there would be two more rounds of confrontation and compromise, in 1530 and 1533, before the council would commit itself and the city openly to the Protestant faith. Yet the aggregate effect of thousands of such incidents is what historians often call the urban reformation—the most dramatic example of popular pressure leading directly to institutional change in the Latin Church. There was no standard scenario for this urban reformation, however; much depended on specific interactions within variable contexts. Some groups proved to be more receptive of the reforming preachers, better organized, more resourceful, or more determined to act than others, while some urban authorities were more open to the new evangelical message, more critical of the established Church, or enjoyed greater latitude for independent action than others.[10] In short, the structures of urban political opportunity varied considerably, not only within the empire but also across the European terrain.[11] What was, in any case, essential to the process of urban reformation was a political space within which civil magistrates, religious authorities, and ordinary people might interact without the immediate intervention of outsiders.

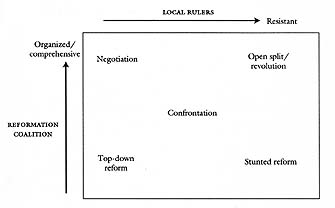

Without pretending to catalog or narrate exhaustively the many complex stories that constitute the urban reformation, it is important at least to describe and account for the patterns of variation and to indicate the duration of the larger process.[12] Given the generally agreed upon importance of the urban reforms, there have already been several attempts to construct paradigms of urban reformation—usually divided into the “imperial city,” the “Hansa city,” and the “late city”—or to distinguish between its “popular” and “magisterial” phases (see Scribner 1990). What I should like to highlight here, however, is not the significance of one or the other type but the more generally observable patterns of interaction between different sorts of reformation coalitions (subjects) and variously receptive municipal authorities (rulers). Figure 4 suggests how we might imagine the array of possibilities.

Fig. 4. Political dynamics of the reformation process in Germany

In one dimension, figure 4 notes variations in the size and coherence or organization of the reformation coalition—that is, in the collaboration between evangelical preachers and laity. In some cases the urban reform movements were remarkably well organized, drawing on preexisting institutions such as guilds or creating new worshiping communities. At the other extreme, popular support for religious reform remained scattered and the cooperation between reforming preachers and responsive laity was too fleeting to be expressed in enduring networks or institutions. In the other dimension, the figure highlights clear differences in the posture of the urban authorities—most often the municipal councils—who, whether they might wish it or not, typically ended up mediating between popular demands for religious innovation and official edicts to the contrary.[13] Their relative resistance or receptivity to popular demands for reform might be predicated on a variety of personal interests as well as structural constraints, but in the end the political conflicts that the Reformation unleashed rarely afforded the rulers of cities the luxury of unmixed motives—whether motives of political expediency or of religious conviction.[14] Putting these variables together, figure 4 suggests how we might understand the differences between communal revolutions and top-down reforms, between the failure of reform and the achievement of negotiation and compromise, as a function of the interaction of rulers and subjects.

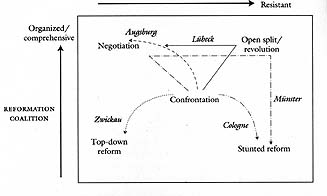

Where a broadly based or well-organized popular coalition interacted with a relatively open or nonresistant regime, the political process, as we have already seen in the case of Augsburg, often resulted in a negotiated settlement and a more gradual or piecemeal transition toward a reformed Church order. This occurred especially in many of the imperial free cities of southern Germany (indeed, it is often identified as the imperial-city reformation), but the same dynamic appeared in a variety of episcopal and territorial cities and in the urban-dominated cantons of northern Switzerland as well.[15] In several Swabian cities, such as Ulm, where those most likely to mobilize in favor of religious reform were more closely associated with the structures of municipal power, the guilds alone, or a faction of the oligarchy allied with them, might successfully push for official action in favor of reform. After attempting to forestall a decision for nearly a decade, the municipal council at Ulm finally submitted the question of religious reform to a vote of the guilds, fraternities, and master craftsmen in 1530, and by an overwhelming majority those who were polled rejected the largely anti-Lutheran imperial edict issued at the close of the Augsburg Reichstag that year. In this way, councils like those at Ulm or at Augsburg, which were torn between imperial decrees and popular sentiments, often chose to compromise with popular demands to survive. In other cases, such as at Strasbourg, where the established regime was more thoroughly divided, popular agitation might easily link with a reforming faction within the oligarchy to produce action in favor of the Reformed church order (Abray 1985; Brady 1985). A similar process of gradual displacement of old patricians occurred at Zürich between 1524 and 1528, which helps to explain the relative delay in the abolition of the Mass in the very seat of the Zwinglian reformation (cf. Cameron 1991: 245–246). In the terms of figure 4, this experience may be represented as a fairly straightforward movement from confrontation toward negotiated reform (and sometimes back again).

Where a coalition of ardent agitators faced off against more resistant authorities, however, the movement for religious reform might succeed only by overwhelming or partially displacing the existing regime. This occurred especially in the northern port cities of the Hanseatic League and some smaller inland territorial cities, where guildsmen were typically excluded from the town councils and local patricians identified themselves with the old Church hierarchy. In these situations, popular mobilization often led to the creation of a burgher committee (Bürgerausschuss) that demanded both a more open constitution and religious reform (Mörke 1983; Schilling 1983). In Lübeck, for example, after five years of unsuccessful negotiation, the burgher coalition seized control of the town council in 1533 and elected their leader as Bürgermeister. Following an unsuccessful involvement in the Counts’ War in Denmark, however, the old oligarchs regained power in Lübeck in 1535. Even so, retaining the religious reforms proved to be a useful way for the returning oligarchs to quiet popular discontent. Thus, although successful antipatrician political agitation was often short-lived and the burgher committees eventually disappeared, the mostly Lutheran religious reforms remained as the most obvious token of the political interaction. Tracing this experience in terms of the framework provided by figure 4, the political process of religious reformation, having begun with confrontation at the center of the diagram, moved first toward revolution in the upper right but eventually veered toward a negotiated compromise following the political restoration of 1535.

Undoubtedly the most spectacular example of an open split or revolution came at the episcopal city of Münster in 1534–1535 (Hsia 1988b). There popular pressure led by the local guilds yielded initially to negotiated Lutheran reforms in the early 1530s while an increasingly radical millenarian movement encountered considerable resistance from the local elite. In early 1534, however, this radical movement, strengthened by an influx of Anabaptists from the Netherlands, seized power, expelled those opposed to it, and instituted a radical religious regime that awakened the fears of Lutherans and Catholics alike. Eventually outside military intervention defeated the millenarian rebels and resulted in the restoration of Catholicism. In the terms of figure 4, then, the complex political process of religious reformation in Münster moved successively from confrontation to negotiation to revolution and finally to a Catholic restoration.

Rather different political dynamics were evident in cities where there was relatively little popular support or largely ineffective popular agitation for religious reform (Mörke 1991). This might be the case where popular evangelical preaching was effectively suppressed; where the preachers gained a following too weak to cause problems serious enough to force official action; or where unprovoked official action might make religious reform seem genuinely “unpopular.” The fact is, of course, that the urban reformation was not a universal experience, even in southern Germany. In the small imperial city of Schwäbish Gmün, for example, evangelical preachers were driven out in the aftermath of the revolts of 1525, and in the 1530s the magistrates responded to guild-based pressure for religious reform by supervising the clergy more closely and by curtailing some of their privileges, but they did so in terms of the old faith, leaving no scope for the institution of a reformed Church order. In the archepiscopal city of Cologne, too, the fear of losing significant privileges and exemptions granted by the prince-bishop appears to have prompted very quick and remarkably effective action to nip Lutheranism in the bud, with the municipal authorities burning Luther’s books, supporting the very conservative theology faculty at the university, censoring the press, and closely controlling the city’s pulpits.[16] At Leipzig, by contrast, it was Duke Georg of Saxony’s ardent Catholicism that not only disallowed Protestant preaching but also led to the expulsion of a number of “closet Lutherans” who had taken to avoiding the confessional and to crossing the border into electoral Saxony to hear Protestant sermons. In the latter two cases especially, the obvious limit to urban reformation was (the fear of) intervention from an external authority, but several cantons of Switzerland—Luzern, Zug, Fribourg, and Solothurn—rejected the reform without such immediate external constraints. In short, confrontation between a weak reformation coalition and a resistant magistracy might lead simply to stunted reform.

Finally, there were a number of cases in which religious reform was clearly initiated and controlled by the political elite. Most often this occurred within principalities or monarchies, but this authoritarian sort of reformation occurred within the more compact political spaces of cities as well. In Zwickau, for example, the local elite very early on established a sort of gospel of civic obedience, preached by Nikolaus Hausmann but favored by few of the local population (Karant-Nunn 1987). When some of their subjects more enthusiastically followed disciples of the radical theologian Thomas Müntzer and the so-called prophets of Zwickau, the council clamped down with its stricter Lutheranism to preserve order and to prevent both radical reform and Catholic reaction. And as late as 1575 the changing opinions of the political elite led to an official reformation in the Alsatian town of Colmar (Greyerz 1980).

It is safe to say, however, that in the vast majority of cases urban reformations were precipitated by popular agitation in the wake of evangelical preaching in the early years of the Protestant revolt and that in each case there were ebbs and flows in the political process in which confrontation might yield to a variety of transient outcomes. Figure 5 illustrates these complex and variant experiences and accounts for them in terms of the interactions between variously resistant local rulers and variously constituted reformation coalitions. Although many German and Swiss cities followed a fairly simple trajectory from confrontation to compromise, this was by no means a simple or universal experience. But in the final analysis, what is striking about all of these urban reformations is that they involved a political process—that is, an interaction between subjects and rulers—in which the local officials of the established Church often played relatively minor roles.

Fig. 5. Variant experiences in the local reformation process

Of course, the Roman Catholic church itself was weakened and divided by the defection of prelates and priests, especially in the early years of the Reformation, but more generally it is true that the terrain of cultural/religious authority was quite effectively contested by evangelical preachers.[17] Not surprisingly, the Catholic church was most successful in fending off the reformation process in those urban political spaces where it claimed both temporal and ecclesiastical authority. But even in ecclesiastical states, the Church was vulnerable because the prince-bishops were so frequently absentees who ruled only indirectly. Thus in the episcopal city of Geneva, on the southwestern frontier of the empire, for example, the prelude to religious reform was political revolution against the bishop’s temporal authority in the 1520s (Monter 1967; Kingdon 1974). Supported by the city-state of Bern, a local coalition of “patriots” declared the city’s independence from both its absentee bishop and the Duchy of Savoy on which the bishopric was dependent. After fending off a dramatic military siege in 1530, the city’s new rulers only gradually began to adopt religious reforms and then by fits and starts that included, in 1538, the expulsion of the most prominent evangelical preachers in the city, Guillaume Farel and Jean Calvin. Eventually, however, a growing reformation coalition did prevail over the hesitancy of Geneva’s magistrates, with the external support of Protestant Bern on whose protection the city depended. Calvin returned in the fall of 1541 to lead the Genevan Reformation but continued to face profound political difficulties until 1555. Only then did Geneva emerge as the international center of the second phase of the European Reformation (Naphy 1994).

| • | • | • |

Dynasties, Princes, and Cycles of Protest

The political dynamics of the reformation process that were especially visible in the compact urban spaces of the German-Roman Empire were not fundamentally different from the interactions of subjects and rulers more generally in the Reformation era. Variations in both the character of the reformation coalition and the receptivity of established rulers can also be said to account for a variety of political interactions in the German countryside prior to, during, and after the Peasants’ War (see esp. Blickle 1992). In literally hundreds of rural jurisdictions, locally formidable coalitions were mobilized to press for redress of a range of social, economic, and religious grievances. In the short term at least, many locally vulnerable rulers were either temporarily displaced or forced into negotiations to buy time. But in the long run, the radical visions of social and political revolution that were articulated by leaders like Thomas Müntzer in the course of 1525 were not likely to find a receptive audience among the established lords and princes who claimed political sovereignty in the south German countryside. Moreover, as the initially local conflicts aggregated into a general war, the likelihood of a well-organized and durable popular political challenge on that scale may be said to have diminished considerably while the collective strength and determination of the “princes” increased inversely. In any case, the decisive defeat of the peasant armies and the rural repression that followed can be said henceforth to have shaped the choices and interactions of all rulers and subjects in the German countryside.

If, prior to and during the crisis of 1525, the political engagement of ordinary German rustics implicated them in a variety of revolutionary situations and tense negotiations regarding the political and religious future (see top half of figure 4), in the years after the Peasants’ War, the reformation process in the German countryside yielded to a variety of more authoritarian outcomes (lower half of fig. 4): either religious reform was decisively stunted by elite resistance or it was imposed from above by authoritarian reformers. In the end, then, a large swath of territories in northern and central Germany would gradually be “Protestantized” as a consequence of the conversions of their immediate overlords while (among others) Bavaria, the lands under direct Habsburg control, and the territories controlled by the major prince-bishops and most other ecclesiastical states would remain officially Catholic and eventually subjected to a “counterreform” designed to promote a new sense of popular piety.[18] Some territories, such as the small principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, might even be reformed, counterreformed, and re-reformed as a consequence of military interventions or dynastic successions. Surely ordinary people were not the principal architects of these essentially authoritarian reformations in the German countryside, but it is important nevertheless to recognize their instrumental roles in initiating the reformation process and moving it forward.

To reconstruct the many pieces of the German reformation process into a larger story, it may be useful to conceive of the scattered events of the urban reformation as well as the widespread explosion of peasant revolts in 1524 and 1525 as constituting a massive cycle of protest within and on the fringes of the German-Roman Empire—a cycle that began in the early 1520s and faded away in the early 1540s.[19] At the beginning of the cycle, news of the experimental reforms of religious practice that began in Wittenberg under Luther’s guidance in the aftermath of the Diet of Worms in 1521 quickly spilled over a variety of political boundaries, and the “Luther question” perforce implicated a variety of rulers and subjects in an accumulating and intensifying struggle over the definition of religious and political authority. In such a cycle of protest, the generally operative limits of knowledge, communication, and solidarity are often broken; patterns of success or failure in one place and time lead to imitation or rejection in the next; and in general, a variety of political actors are emboldened to seize political opportunities that they hardly could have imagined to exist before the cycle began (cf. Giugni 1992). In this case, the military defeat of the peasant armies contrasts sharply, to be sure, with the relative success of the urban reform movements. Still, it is important to take seriously their coincidence in time and place, if for no other reason than that the defeat of the peasant armies and the rural repression that followed undoubtedly had a chastening effect on rulers and subjects alike—not only within the empire but throughout Europe as well.

The powerful confluence of so many extraordinary events across such a broad terrain cries out, then, for more than a calculation of the relative strengths and weaknesses of political actors within particular cities, territories, and regions of the empire. Indeed, it is clear that the German cycle of protest coincided with a general crisis of imperial power. Despite the emperor’s intrepid support of Catholic orthodoxy and a succession of imperial edicts, it became brutally obvious in the wake of the Diet of Worms that neither Charles V nor his brother and regent, Ferdinand, was in a position to stem the tide of popular protest and unsanctioned religious innovation.[20] Not only were the imperial authorities powerless to punish, quickly and efficiently, those officials who violated imperial policy—for example, neither the municipal council of Augsburg nor the Elector of Saxony who protected Luther—but they were equally unable to protect or reward those nominal subordinates who might valiantly try to defend the established Church order—for example, the council at Lübeck—against popular demands for reform. Even the repression of the peasant revolts, which was predicated on an unusual consensus among the diverse rulers of southern Germany, was more clearly the work of the Swabian League of local and regional authorities than of the emperor.

It was, thus, in the context of a general crisis of imperial authority that there emerged an unprecedented array of coalitions in favor of religious reform—coalitions formed locally by the alliance of evangelical preachers and a newly emboldened laity in both the cities and the countryside. Especially in the heady months leading up to the conflagration of 1525, the general cycle of protest was fueled by the quite reasonable perception of extraordinary opportunities to act decisively and in some cases by apocalyptic visions of a better future. The defeat of the peasant armies severely limited or even closed down entirely the opportunities for many thousands of actors in the countryside of southern and central Germany, but the cities and more generally the cantons of the Swiss Confederation remained basically unviolated spaces within which ordinary people could continue, under the varying conditions we have already observed, to engage in the political process of religious reformation.

How long could these conditions last and the cycle of protest continue? Not long, for at least two reasons. First, the progressive division of the constituent parts of the empire and the Swiss Confederation into armed and openly hostile “Protestant” [21] and Catholic alliances clearly limited the room to maneuver for all political actors, including popular reform coalitions. Still, within the empire the defenders of the new reforms managed to forestall an armed confrontation and to bargain for time by demanding a general council of the Church to resolve the outstanding religious issues. Second, the reformation coalitions that were the driving force of protest and reform were transient entities. As the early destructive phase of the Reformation gave way to the immensely more difficult task of constructing a new religious order, the initially powerful coalitions between clerical reformers and ordinary people gave way to a more general estrangement of the newly professionalized Protestant clergy from what they often perceived as a “superstitious” and sometimes hostile laity (Cameron 1991: 389–416). At the same time that magistrates and princes claimed increasingly to speak for and to control the new Protestantism, the initial popular enthusiasm of the reforming coalition diminished. With the gradual demise of the reformation coalitions, then, the cycle of protest began to fade away.

Thus the summoning of the Council of Trent in 1545 and the defeat of the Protestants in the Schmalkaldic War (1545–1547) may be said to have ushered in a new phase of reformation politics. After another round of warfare in the early 1550s, the Reichstag at Augsburg in 1555 finally adopted a thoroughly authoritarian settlement encapsulated in the principle cuius regio eius religio (roughly, “whose rule, his religion”). By the terms of the Peace of Augsburg, the rulers of what were the culturally “sovereign” principalities of the empire would be empowered to choose either the Lutheran Augsburg Confession or Catholicism and in doing so determine the religion of their subjects, who were “free” to emigrate if they disagreed; imperial cities could adopt Lutheranism only with the proviso that they accept some form of Catholic worship as well; and territorial cities were expected to follow the decisions of their immediate overlords.

In the end, it is critical to recognize that the political variables that may be said to have governed the interactions of subjects and rulers in the beginning of the cycle of religious protest and reform in Germany are not the same as those that determined the long-term outcome of the reformation process. The point is, of course, that the local and relatively compact or dense political spaces within which the interactions originated were not inviolable, and eventually the networks of alliance or lines of competition that evolved among the various rulers of Charles V’s vast domain could be as important to the outcome of the process as the relative strength or resolve of the locally mobilized popular political actors. In some cases, popular reformation coalitions might be allied with local authorities, as a result of local negotiations or compromises, but opposed by an array of territorial and imperial authorities (see fig. 2a); in others, where revolutionary splits divided rulers from subjects, reform coalitions might find themselves facing a formidable threat of outside intervention from transient alliances of local, territorial, and imperial rulers (see fig. 2b). But even if those interlocal networks of political power can be said to account generally for the religious geography of Germany at the end of Charles V’s tempestuous reign as emperor, this does not obliterate the critical roles that ordinary people played in initiating the reformation process in the towns and villages in which they lived and worshiped. Nor does it diminish the long-term importance of these interactions—as embedded in new structures of power and in inevitably partial and locally partisan historical memories—for domestic political interactions once the immediate cycle of protest and reform had passed.

In the final analysis, a simple tabulation of winners and losers in this complex historical process is impossible for at least two reasons. First, it would involve an infinitely complex comparison of the intentions and transient achievements of an enormous range of political actors. But even if we could, despite the obvious documentary and epistemological uncertainties involved, execute such a comparison, we would certainly find that no one could have willed or intended the bundle of political and religious compromises that were legitimated by the Peace of Augsburg. Though the peace was formally promulgated in Charles V’s name, it was an outcome of the political process that he personally could not accept; indeed, prior to the meeting of the imperial diet he had abdicated the imperial throne and turned over his authority in the complex negotiations to his brother, Ferdinand, who would later be crowned the new emperor. Apparently the ever-pious Charles could not bring himself to recognize the legitimacy of Protestant churches within the empire; in any case, it is clear that the ever-political Charles could not have lived with the permanent limitations on his sovereign authority as emperor. Though, as we shall see in chapter 4, another round of conflict culminating in the Thirty Years’ War redrew the religious map of Germany and the imperial constitution continued to preserve an important degree of imperial “sovereignty,” the Peace of Augsburg laid down the parameters of Germany’s subsequent political and cultural development. The official cultural monopoly of the Roman Catholic church had been broken, and both the cultural and political “sovereignty” of the empire had been fundamentally segmented.

| • | • | • |

Patterns of Princely Reformation

To understand the political significance of the reformation process in Germany in a broader comparative context, it will be useful to examine briefly the “princely” reformations that took place simultaneously in Scandinavia and England. In terms of sheer numbers of ordinary people whose religious experience was transformed by the reformation process, the princely reformations in northern Germany and beyond were obviously more important than the popular urban reformations since in most of Europe only a small minority of the population lived in cities.[22] It would be as misleading, however, to imagine a singular “princely” type of reformation as it is to posit a uniform and unchanging experience of urban reformation. Here we will take as our point of departure the assumption that a princely reformation is one in which the reform of religious ritual and belief occurred with at least the tacit support of the territorial lord or prince. Given this obviously broad and inclusive baseline, it will be possible not only to describe a range of variation in princely reformations but also to underscore once again the importance of popular engagement in the political process of reformation. In Scandinavia alone, Ole Peter Grell (1992, 1995) distinguishes three different patterns of princely reformation: in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein and in the composite monarchies of Denmark/ Norway and Sweden/Finland. But before we look at each in turn, we need to recognize their common historical background in the Union of Scandinavian Kingdoms.

Originally the dynastic achievement in 1397 of the Danish queen, Margrethe I, the Union of Scandinavian Kingdoms (including Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, along with Finland and the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein) was at the beginning of the sixteenth century on the verge of collapse (Kirby 1990; Metcalf 1995). Christian II’s aggressive attempts to consolidate his control over this vast dynastic composite served only to antagonize both the lay and the ecclesiastical elites whose authority at the local and regional levels he threatened (Grell 1995). Following the massacre of some eighty lay and ecclesiastical lords in Stockholm in 1520, a noble revolt led by Gustav Vasa reestablished the independence of the Swedish kingdom in 1521, with Vasa as regent.[23] Meanwhile, the growing opposition of the Danish aristocracy led in 1523 to the overthrow and exile of Christian II, followed by the election of Duke Frederik of Schleswig and Holstein, Christian’s uncle, as king. Gustav Vasa and Frederik I, as usurpers, had a common interest in preventing the return of Christian II, and despite Gustav’s suspicion that Frederik sought to reunite the composite under the Danish Crown, they cooperated to fend off Christian’s intermittent attacks until his final defeat in 1532. It was against this backdrop of political instability and uncertainty—what we might regard as a classic political crisis within a composite state—that the Protestant Reformation first took root in Scandinavia.

The duchies of Schleswig and Holstein illustrate the enormous political complexities of late medieval dynasticism. The duke of Holstein was a vassal of the German-Roman Empire while the duke of Schleswig was a vassal of Denmark, but in 1460 the two units had been declared to be administratively “inseparable and indivisible” (Lausten 1995). Under Christian II, the duchies had been ruled separately by Duke Frederik, but with his election as king they were once again brought closer to the Danish kingdom. In 1525, Frederik’s son, Christian, who eventually succeeded to the Danish throne as Christian III, took over administration of Haderslev and Tönning, which were part of the duchy of Schleswig, and it was under his sponsorship that Lutheranism was first institutionalized in the region (Grell 1992; Lausten 1995). Although there had been evangelical preachers in the area since 1521, where possible Christian intervened directly to dismiss prelates opposed to reform, to appoint evangelical preachers, to provide training for evangelical pastors, and to design new ecclesiastical regulations—first in Haderslev alone, but after 1526 (when he became regent of the two duchies) more generally in Schleswig and Holstein. By 1528, according to Grell (1992: 97), the “Reformation was a fait accompli ” when the Synod at Haderslev, called by Christian, enacted the Haderslev Church Ordinance. One of the first of what would be many Lutheran church ordinances in Europe, the Haderslev Church Ordinance was intended to guide the parish clergy in their pastoral activities; besides advising the ministers to preach the Gospel as spelled out by Luther, it obliged them to swear an oath of allegiance to the duke.

Within the small domain of Haderslev (and more generally in Schleswig and Holstein), a modest popular base aligned with the active support of the local lord was sufficient to prevail over the modest opposition of the episcopal establishment. The result was an essentially peaceful and official reform with a strong dose of civil regulation of formerly ecclesiastical affairs such as education and poor relief. Within the larger kingdom of Denmark, by contrast, the political dynamics of the reformation process were significantly different. In the first place, King Frederik owed his position to the combined lay and ecclesiastical elite who had deposed his nephew; indeed, according to the coronation charter that he was required to sign in 1523, Frederik promised, “[We will] not allow any heretics, disciples of Luther or others to preach and teach, either openly or secretly, against God, the faith of the Holy Church, the holiest father, the Pope, or the Catholic Church, but where they are found in this Kingdom, We promise to punish them on life and property” (quoted in Grell 1992: 104). Though Frederik clearly violated this oath in several instances, he was nevertheless forced in some measure to honor it at least publicly as long as the return of Christian II, who had converted to Lutheranism in exile, was a real threat. Consequently, the process of reformation in Denmark proceeded more clearly from the bottom up, building on the base of popular reformation coalitions in the cities (see Grell 1992; Lausten 1995). The earliest successes of popular evangelical preaching were in the small city of Viborg in Jutland where Hans Tausen, a former member of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, was able to build up a popular following and a colleague, Jorgen Jensen Sadolin, established a school for evangelical preachers in 1526; both men were supported by royal letters of protection, granted at the request of local magistrates.[24]

In the same year, a Danish Herredag (Parliament) meeting in Odense transformed the Catholic church in Denmark into a national church as a means of dealing with clerical abuse without transforming religious practice; in practice this meant that locally appointed bishops were not to seek confirmation from Rome and that revenues that had earlier been sent to Rome should now flow to the Crown. In the following year, however, Frederik publicly proclaimed a neutral stance with regard to matters of ritual and belief, declaring that “‘the Holy Christian Faith is free’ and that he governed ‘life and property, not the soul’” (Grell 1992: 106). With this kind of tacit support, the evangelicals gathered strength in Viborg, appropriating the Franciscan and Dominican monasteries for their own use, closing down many parish churches, and restricting Catholic worship to the Cathedral; by the end of 1529, public disturbances had ended public Catholic worship altogether. Meanwhile, the reform-minded magistracy of Malmö in Scania (today part of Sweden) began actively recruiting evangelical preachers. At first evangelical preaching was only allowed outside the walls of the town, but as the services became more popular they were moved into a chapel and finally a larger church. The reform movement suffered a temporary setback in Malmö in 1528 when the archbishop of Lund threatened the magistrates with a heresy trial, but by 1529, again with the tacit approval of the king, the evangelical preachers and magistrates of Malmö were emboldened sufficiently to seize church properties, including the mendicant houses, and to rid the city of a restive Catholic minority (Grell 1988, 1990). By 1530 the evangelical reform movement had gained a significant following in all the towns and cities of Denmark (Lausten 1995), but in Copenhagen it had been denied comparable political success, in part because of the strong defense of the Catholic establishment by the local bishop. At the same time, however, the effectiveness of popular support for religious reform was deflected by factionalism that paralyzed the municipal council. Although there were at least four evangelical preachers in the city and the city council had managed to take over most of the monasteries, Copenhagen remained divided between Protestants and Catholics prior to Christian II’s last attempt to regain his throne in 1531—this time with the support of his brother-in-law, Charles V of Habsburg, at whose insistence Christian had reconverted to Catholicism.

The final defeat and arrest of Christian II in 1532 might have signaled the beginning of a more comprehensive princely reformation had it not been for the untimely death of Frederik I. When a conservative minority of aristocrats on the royal council prevented the immediate election of Frederick’s Lutheran son, Duke Christian of Schleswig and Holstein, the stage was set for civil war: the Grevens Fejde, which was precipitated by the revolt of Malmö against the royal council, ostensibly in defense of its municipal reformation (cf. Grell 1988). Although the aristocrats quickly backed down and elected Christian a month later, the alliance of Malmö and (more reluctantly) Copenhagen with the Hanseatic cities of northern Germany defined the essentially political struggle between the king and key elements of his composite domain (with both sides supporting Lutheranism) until Copenhagen finally surrendered in 1536. Once Christian III had won the war, he immediately imprisoned the Catholic bishops and summoned a parliament, composed of an unusually large number of gentry, burghers, and peasants, to create a Lutheran territorial Church (Metcalf 1995). In light of its broad base of popular support after a full decade of evangelical preaching, especially in the cities, the Church Ordinance of 1537 proved to be an excellent tool for Christian III, in the wake of nearly two decades of political instability, to consolidate his “sovereignty” in a remarkably uniform and direct fashion throughout his domain.

In the kingdom of Sweden, the reformation process followed yet another course (Grell 1992; Kouri 1995; see also Roberts 1968). Though Gustav Vasa is often said to have been less keenly interested in evangelical religion than his Danish counterparts, that he charted a far more hesitant course toward the creation of a Lutheran national church reflects real political constraints as well. For our purposes, what is most telling is the general consensus that evangelical preaching failed to build a broad base of popular support for the cause of religious reformation in either Sweden or Finland. Thus popular support for the Protestant cause was strongest in Stockholm, particularly among the large German population, which was always in some sense suspect because of its extensive ties with the (Lutheran) Hanseatic cities of the Baltic coast. By the same token, prior to 1540 Vasa was faced repeatedly with rural uprisings that not only protested the heavy taxation that Vasa demanded to repay the significant debts he incurred in fighting for Swedish independence but also defended traditional Catholic religious practice. The latter reflected, in all likelihood, not so much a generalized peasant conservatism as the considerable success of Catholic priests in gaining popular support by identifying with peasant grievances against the fiscal exactions of the new monarch (Kouri 1995).[25]