13. The Golden Age bxefore the Golden Age

Commercial Egyptian Cinema Before the 1960s

Walter Armbrust

[In the 1940s] a type of film began which one could call a “collage”—a collage of songs and dances. But it wasn’t cinema, or at least not what we know as cinema.

One often encounters the opinion that “serious” Egyptian cinema dates from the 1960s, when the state partially nationalized the cinema, thereby allowing some directors to produce films according to criteria other than marketability. Although support for the public-sector cinema of the 1960s is not universal,[1] on one related issue intellectuals in both the pro– and anti–public-sector camps are substantially in agreement: there is little value in most of the films made in the three decades before the 1960s.

A small number of the nine hundred fifty Egyptian films made from 1927 to the early 1960s are excepted from axiomatic disparagement. These tend to be films interpreted as leading up to the 1960s, that is, works by directors who became prominent in the 1960s, and films that in retrospect are thematically similar to certain genres of the 1960s fare better than the rest. General audiences and fan magazines are more forgiving of the commercialism dominant in films made before the appearance of public-sector cinema. Critics attribute this enthusiasm to the misguided tastes of uneducated people suddenly thrust into the unfamiliar role of culture consumers. But is there really nothing more to be said of the hundreds of pre-1960s commercial genre films than that they are too vulgar to be worthy of attention?

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, I assume that early Egyptian films are important; that their ambiguous status as art should be a point of analysis rather than a reason to ignore them. Pierre Bourdieu suggests that the transcendence of art is “based on the power of the dominant to impose, by their very existence, a definition of excellence which…is bound to appear simultaneously as distinctive and different, and therefore both arbitrary…and perfectly necessary, absolute and natural” (1984, 255). Stuart Levine states the matter more directly: art forms, he says, are “not necessarily the product of ‘cosmic truths, but are rather the result of certain peculiarities in the way in which our culture operates’” (quoted in Levine 1988, 2). Art is rooted ultimately in socially constructed systems of taste, and the converse is also true: lack of “good taste” is constructed through artistic expression, although it may not be recognized as such by arbiters of high culture. The social basis of artistic hierarchies—lowbrow to highbrow—seems obvious to anthropologists, but the idea has never taken root in the analysis of Egyptian (or more generally Arab) cinema.[2]

Early films are particularly important in the construction of Egyptian nationalism, as well as of Egypt’s relationship with other Arabic-speaking societies. This is not to say that there is any simple congruence between nationalist ideology and the cinema. Many critics would simply dismiss commercial Egyptian films as a celebration of undesirable elements of Egyptian culture. Furthermore, even the degree to which the Egyptian cinema is truly Egyptian can be questioned from many different perspectives. Long before the tensions between globalism and localism became salient in academia, the Egyptian cinema was affected by both. The history of the uncomfortable position of commercial Egyptian cinema within local and nonlocal frames of reference was particularly relevant at an event recently held in New York—a large Arab film festival called the Centennial of Arab Cinema.[3]

Twenty-one of the forty films shown at the festival were Egyptian. Most of the twenty-one Egyptian films were either recent works or works in some way linked to the public sector.[4] Only two of the films shown had no link whatsoever—historically or thematically—to the public-sector cinema of the 1960s. Both were musicals, and it is one of these, Ghazal al-banat (The Flirtation of Girls; Wajdi 1949),[5] that interests me. In particular, the juxtaposition of The Flirtation of Girls with the film that followed it, a Tunisian production titled Un été à la Goulette (Summer in La Goulette; Boughedir 1995), shows how problematic the wholesale dismissal of commercial “genre films” can be, particularly in a cross-cultural context in which audiences may be ill-equipped to appreciate even the more rudimentary social and historical features of a film, let alone anything that could be described as a subtlety.

Film festivals are forced to juggle two not necessarily compatible objectives: “The desire to solve the problem of foreignness by overcoming difference or to communicate foreignness by revealing difference” (Schwartzman 1995, 90).[6] Reconciling the limitations of a metropolitan audience’s perspectives with the imperative to present and interpret “difference”—a category that encompasses an obviously dizzying range of possibilities—is inevitably a part of any film festival. As a recent Cineaste editorial put it, “On the one hand, it seems foolish to discuss films Americans can’t see, but if we don’t promote at least the best of them, how will an audience for them ever be created?” (“Editorial” 1996, 1 [my emphasis]). The process of selecting “the best of them” often leads to a wholesale rejection of commercial films, which, in the context of “Arab cinema,” means the bulk of Egyptian production.[7] The problem is that many commercial Egyptian films are excellent candidates for “revealing difference.” Such films may exhibit a “density of local reference” (Crofts 1993, 59) lacking in films designed from the ground up to interpret one culture to another.

This is not to say that festival organizers have a great deal of leeway in their choices. They know that an audience can tolerate only so much “difference,” and they are certainly not unaware that the fit between the films they exhibit and the audiences’ ability to understand unfamiliar traditions is less than perfect. Festival curators are often intensely (even uncomfortably) aware of the difficulties inherent in selecting “a comprehensive group of films meant to introduce some…contemporary national cinema production to another country where there has been virtually no previous encounter with that cinema or culture in general” (Schwartzman 1995, 70).[8] I am not suggesting that the Centennial festival failed to achieve this objective but that the inclusion of The Flirtation of Girls was a factor in its success. Furthermore, this is not because the festival organizers were making a concession to commercial mass culture. The Flirtation of Girls belonged in the festival on its own merits as a film, which one would not expect given conventional opinions about the merits of Egyptian commercial films. Furthermore, as a means of “communicating foreignness by revealing difference,” as Schwartzman put it, the film was probably without peer in the Centennial festival. It is ironic that expert specialist opinion generally encourages us to think just the opposite of such films—that they are simple, obvious, and culturally homogenizing.

| • | • | • |

The Flirtation of Girls played in New York to a rather small crowd of perhaps fifty people in the Walter Reade Theater, which can accommodate several hundred spectators. The film starred Layla Murad, a singer; Najib al-Rihani, a comedian; and Anwar Wajdi, an actor who played both comic and dramatic roles. The film also featured cameo appearances by two other prominent personalities, the actor and director Yusuf Wahbi and Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, a singer and composer, considered to have been one of the greatest musicians of his day.

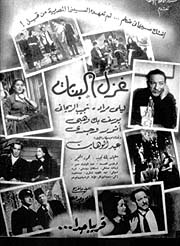

Fig. 17. A collage of publicity stills in an advertisement for The Flirtation of Girls. (al-Ithnayn, no. 761, January 10, 1949, p. 2). Courtesy of Dar al-Hilal.

The Flirtation of Girls is nothing more or less than a showcase for stars—very much the “collage” mentioned so disparagingly by Tawfiq Salih in the epigraph to this chapter. It is primarily about media-constructed personalities, and even critics who are not favorably inclined to commercial films have conceded that it has a certain charm (e.g., Salih 1986, 200). Taken individually, each of the film’s principals can be counted a national icon; the overall construction of the film, however, puts it in a category that gets very little critical respect. Scantily clad dancing girls were featured in quantity, alternating with slapstick comedy routines. Both were scattered through an implausible and barely coherent plot that showed complete indifference to the lives of “real” people. There was little effort to integrate the film’s songs with the plot—they simply occurred at fairly regular, and no doubt commercially marketable, intervals.

But the dialogue, full of double entendres and in some places written in rhyming prose, is hilarious, even for a non-native speaker of Arabic like myself. Badi‘ Khayri, a colloquial playwright and the man who wrote the film’s dialogue, might have been a minor figure compared to canonical authors who, by definition, wrote mainly in proper literary Arabic. But he knew how to connect with an audience, and he was one of the cleverest and most popular writers in Egypt.[9] The film ends with the cameos by Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab and Yusuf Wahbi, who play themselves. By the time they appear the principal members of the cast—Murad, Wajdi, and al-Rihani—are in Wahbi’s mansion and ‘Abd al-Wahhab is in another room rehearsing with his orchestra. Wahbi, known for melodrama, is hilarious in this scene—full of self-mockery, madly throwing out intertextual references to other works he and some of the other actors had appeared in. Then ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s orchestra starts to play and they all go to listen. ‘Abd al-Wahhab, famous not only for his singing and composing but also for having expanded the traditional Arabic ensemble, appears directing an orchestra that includes balalaika and piccolo sections. The music brings everyone to an emotional crescendo; the plot is resolved through Wahbi’s sage advice to the younger members of the cast; the various characters in the film see the folly of their ways; the right man marries the right woman; almost everybody lives happily ever after (more about that “almost” below).

When the film ended I went out to the lobby of the Walter Reade Theater and overheard an American man saying wearily and with heavy condescension, “Well, we have to see something that the unwashed masses watched.” I was taken aback. He had just seen a film that tied together everything from low-down vernacular jokes to classical poetry; a film thoroughly embedded in what, in a context other than the much-maligned Egyptian cinema, might have been called a complex and sophisticated semiotic system. He had just seen an incredibly rich slice of Egyptian history—something that everybody in Egypt knows and many have practically memorized. Did he not come to the festival to get some insight into Egyptian society? What more could he want?

The experts brought to New York to comment on the phenomenon of Arab cinema had only encouraged him to think that he had just seen a bad film. All of them, including Tawfiq Salih, Egypt’s sole official representative at the festival, sought to distance themselves from commercial Egyptian cinema.[10] Some did so politely on nationalist grounds (“It’s not our nationalism being represented, but no doubt it’s fine for Egypt”), and others were more vociferous in pointing out what they saw as the aesthetic shortcomings of Egyptian films. Salih, for his part, contended that the Egyptian cinema began with high ideals but degenerated due to the necessity of marketing to unsophisticated Arab audiences, followed by other economic and political upheavals.[11]

What the American man in the lobby wanted became clear from the next film, the Tunisian production that followed The Flirtation of Girls. This was Summer in La Goulette, and the crowd that turned up for it was many times larger than that for the previous film—probably a sold-out theater.[12] It was a nostalgic piece set just before the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, in a Tunisian beach town, La Goulette. La Goulette is portrayed as a place in which Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived in distinct communities that fit together in a blissful syncretism of polite equality. The only threats to this harmony come from the Arab East. The looming Arab-Israeli conflict poisons attitudes toward Jews among the weaker members of the community, but others in the Muslim community vigorously defend the honor and national commitment of their non-Muslim countrymen. Another incipient threat to local harmony comes in the form of a pious and greedy landlord who has spent too much time in the East, which has caused him to adopt a narrow and hypocritical interpretation of Islam. On a local level only benign traditional prohibitions against interfaith marriage cast a cloud on the perfection that was La Goulette, and even this does not prevent the younger generation from flirting with the idea of crossing that boundary.

It would not be stretching a point to say that the film was about no less a Western concern than multicultural pluralism, but of course set in Tunisia rather than in a Western country. At the same time there is no question that Summer in La Goulette contested prevailing American stereotypes about the “timelessness” of hostility between Muslims and Jews (although what proportion of the audience in the Lincoln Center held such stereotypes is an open question). The film revealed that the Italian actress Claudia Cardinale was born in Tunisia in this very town. In the course of the film she comes back to La Goulette, and no doubt many in the audience were inclined to see her cameo appearance as a sophisticated transnational representation that breaks down stereotypes and shows how borders are continually being crossed and blurred. In the end it was a pleasant film. A number of scenes featured bare-breasted women and nudity (not quite of the “full-frontal” variety), which will keep it from being shown in too many Arab countries.[13] The film also revealed Arab women as having a healthy libido, which may confound the expectations of metropolitan spectators inclined to see Middle Eastern women as repressed. It also suggested that pious religious prudery is not the “real Islam,” and although academics have long cautioned against such essentialisms as “real Islam,” an Arab film casting religious zealotry in a negative light will be enlightening for many a metropolitan spectator.[14]

Outside of a general awareness of the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (the film’s historical backdrop), very little specialist knowledge about Tunisia or North Africa was necessary to appreciate Summer in La Goulette. This was virtually mandated by the economics of the film; Summer in La Goulette began with a long list of corporate and governmental agencies that sponsored the film, all of them European. The film was made from the ground up as a production that had to be marketed to metropolitan audiences who knew little or nothing about Tunisia.

| • | • | • |

David Morley describes the postmodern world as subject to “simultaneous processes of homogenization and fragmentation, globalization and localization in contemporary culture” (1995, 15). His formulation is close kin to Schwartzman’s curatorial dilemma of “solving the problem of foreignness by overcoming difference” or “communicating foreignness by revealing difference” (1995, 90).

Which film was the more “homogenizing,” the unabashedly commercial Flirtation of Girls or the multiculturalist Summer in La Goulette? Considered purely as texts one could unhesitatingly say it was The Flirtation of Girls. In the context of a New York film festival audience more familiar with debates over multiculturalsm than with the conventions of Egyptian cinema, it is a much more difficult question.

One criticism constantly leveled at Egyptian cinema is that it did little more than plagiarize Hollywood. This was an accusation repeated often at the academic panels of the Centennial festival. But I would suggest that the reason Summer in La Goulette connects with an international audience so much more easily than The Flirtation of Girls is not so much because of its inherent sophistication or its refusal of Hollywood genres but because it understood film festival genres so well. It demands very little of its audience. One needs to bring very little to the theater to see this film. By contrast, The Flirtation of Girls was embedded in a thick web of local references; the jokes were far funnier for an audience that could appreciate shifts in linguistic register and the music much more interesting to people familiar—even just a little bit as non-native speakers like myself inevitably are—with the previous work of the actors.

An American-based festival of foreign films is about cultural diversity. But which film strikes audiences in unfamiliar ways? The one a Western audience can watch with no prior knowledge of the country represented in the film? Or the film that is actually quite inaccessible if one is not somewhat versed in the history and culture of the audience for whom the film was intended? Of course, The Flirtation of Girls could have been made more accessible with some program notes, and perhaps a brief lecture, but the people who organized the festival, and the critics and directors brought in to comment on the films, all subscribed to the stereotype that there is nothing worth saying about Egyptian cinema before the 1960s except for the rare flashes of interesting filmmaking that could be interpreted as leading to the golden age of the public sector.

But all this is only a prelude to the real irony in the juxtaposition of these two films. The Tunisian film was about history, and the actors in the film represented characters who were Muslim, Christian, and Jewish. But what nobody said was that the suave, sophisticated, and eminently multicultural Summer in La Goulette had been preceded by a 1949 Egyptian film that starred a Muslim (Anwar Wajdi), a Christian (Najib al-Rihani), and a former Jew (Layla Murad, who converted to Islam in the mid-1940s).

There was also an analogue to Summer in La Goulette’s having used a cameo appearance by Claudia Cardinale. Cardinale was certainly a nice touch, but the American audience of The Flirtation of Girls was never informed of the transregional character of its actors: both Layla Murad and Najib al-Rihani, like Cardinale, were born in one country to families that had emigrated from another. Murad’s father was from the Levant, and al-Rihani’s was from Iraq (Hasanayn 1993, 20, 158; Abou Saif 1969, 23). Many others of the film’s personnel were marginal to Egyptian nationalism in various ways.[15]

Furthermore, it is likely that everyone in the Egyptian audience of 1949 knew that they were seeing a film starring a Muslim, a converted Jew, and a Christian. Religious affiliation was certainly not a prominent part of their public images,[16] but in 1948, shortly after the war in Palestine/Israel, the popular magazine al-Ithnayn (no. 737, July 26, 1948) did run a cover illustration showing Layla Murad wearing a Muslim prayer shawl and reading the Qur’an. The caption said “Layla the Muslim” and referred the reader to a two-page article showing Murad praying and receiving religious instruction from a sheikh. “Here is Layla’s new film, in her private life, not on the screen. We know it by the name of ‘Layla the Muslim’” (“Layla al-Muslima” 1948, 8). The article went on to explain that although Murad had been born “Israeli” (the word “Jewish” does not appear in the article), she had converted three years earlier but only recently declared her conversion publicly. The press, according to this article, was taken by surprise, with some papers believing the conversion to be sincere, while others speculated that it was done for publicity.

In terms of a metropolitan film festival this is obviously more along the lines of “the dialectics of presence/absence” (Shohat and Stam 1994, 223–30) than of the self-conscious celebration of identity featured in Summer in La Goulette. But the resonance of such a dialectic was surely very different in 1949 Egypt than it was in New York in 1996. Is an Egyptian film, in which the religious identities of the actors were subsumed by Egyptian national identity, less historically revealing than a Tunisian film in which the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian identities of the characters are foregrounded and made to look distinct? More important, more or less revealing to what sort of audience? Summer in La Goulette is a contemporary take on history tailored to the sensibilities of the Western audiences and agencies that fund it; The Flirtation of Girls, by contrast, was history. Where does The Flirtation of Girls fit in Schwartzman’s balance between the need to solve the problem of foreignness by overcoming difference or to communicate foreignness by revealing difference? The conventional wisdom is that films like The Flirtation of Girls are not different enough to bother with because they are nothing more than commercial Hollywood clones.

I am suggesting that by emphasizing the explicitly multicultural Tunisian film and systematically downgrading the value of the Egyptian film we risk taking the path of least resistance. For an American audience the harder film to appreciate is The Flirtation of Girls. If we are really committed to the idea of interpreting cultural difference, this is a film that might repay greater efforts to understand it.

| • | • | • |

The Cinema and Its Critics

Americans can certainly be forgiven their unfamiliarity with the Egyptian cinema. Many are scarcely aware that there is such a thing, for over most of its history the Egyptian film industry has been systematically ignored in our literature on the Middle East. This is not the result of an oversight. Egyptian intellectuals themselves, who are the most influential interpreters of Egyptian culture in the West, do not for the most part patronize or praise their national film industry. It should be noted that the jaundiced eye cast by intellectuals toward the Egyptian cinema was not unlike the low regard American intellectuals had for their own national cinema, at least until relatively recently. James B. Twitchell (1992, 131–38) suggests that the transformation of “movies” into the more intellectually legitimate “cinema” dates, in America, only from the 1960s. He identifies Andrew Sarris’s ([1962] 1994) adoption of “auteur theory” as a watershed in this transformation. Twitchell considers efforts to analyze films as art to be largely a waste of time and any artistic achievement in films to be incidental to the main objective of making money. For example, he quotes Charlie Chaplin as saying “I went into the business for money and the art grew out of it” (Twitchell 1992, 132) as evidence of the essential irrelevance of art in the film business. However, Chaplin’s confession of commercial interest still leaves him some space for the artistic value many have seen in his work. By the same token the obviously commercial Flirtation of Girls should not blind us to the fact that the people who made it did take themselves very seriously as artists. And on an individual level, if not on the level of Flirtation’s generic conventions, so too do many Egyptian critics and nonspecialist spectators take the stars of the film seriously as artists.

But aside from a critical distaste for commercialism, which Egyptian intellectuals shared with critics everywhere, one of the problems with Egyptian cinema in the eyes of its fiercest critics was the way it constructed Egyptian identity. In a nutshell, it was deemed too derivative to be truly Egyptian. Samir Farid, a prominent Egyptian film critic, summed up the feelings of many intellectuals in the following passage:

Farid wrote those lines in 1986. Possibly the only thing he would change if he were to rewrite his article today is that now there are close to three thousand Egyptian films that have failed to deliver the goods.Over the course of more than two thousand films produced in half a century, and then shown again on television and destined to continue being aired on the video, the image of the Egyptian prevalent in Egyptian films is Egyptian in his clothes, his accent and manner of speaking, his movements. But he is not Egyptian in his traditions and customs, behavior, thoughts, actions and reactions. The reason for this is the prevalence of the Western model in Egyptian filmmaking. The filmmakers are Egyptian, and the films are made in Egypt, but their content is Western. (1986, 209)

But while intellectuals turned their backs on the Egyptian cinema early on, there was still a broad audience for the product. Egyptian films were salable, and Egyptian industrialists began investing in a film-production infrastructure by the mid-1930s.[17] Production began to rise: twelve films in 1935, twenty-two annually by 1942. What really put the film industry on solid ground, though, was World War II, which brought together several factors favorable to the Egyptian cinema. One was a sudden decrease in the availability of foreign films to compete with the local product. The other was an influx of capital into Egyptian hands. Egypt became a staging ground for the British war effort, and much money was made, not all of it legitimately. The cinema seems to have been regarded by Egyptian capitalists as an excellent investment, particularly, it is suspected, when the money was earned on the black market. The period from 1945 to 1952 is therefore known as the “cinema of war profiteers.” In 1945 forty-two films were produced—almost double the total of any previous year in the history of Egyptian cinema. Shortly thereafter production leveled off at around fifty films per year, which is where it has been ever since. The latter date, 1952, marks the accession to power of the Free Officers led ultimately by Gamal Abdel Nasser, after which, one assumes, the laundering of ill-gotten gains in the cinema subsided. At any rate, Egyptian film historians do not extend the “cinema of war profiteers” label beyond 1952, when Egypt became independent. But then a new problem arose, which was that the financiers were, for the most part, not Egyptian at all (mainly they were Lebanese) from the mid-1940s until nationalization in the 1960s (Salih 1986, 195–96).

In particular, intellectuals censure the late 1940s—the period in which The Flirtation of Girls was produced—as a period in which vulgarity was assumed to have predominated. In the 1940s, as Salih describes it,

there were many people who had worked with the English army…who made a lot of money.…Because of this the cinema flourished, particularly since it was cheaper to see a dancer or a dance routine in a film than it was to go to a cabaret. The film gave you more details of the dancer than you could see in a cabaret. These economic and historical developments changed the character of the cinema. At the level of craft [al-mustawa al-hirafi] the effect was serious. (1986, 196)

Nasser did not take much interest in the cinema during the 1950s. A few directors were inspired by socialist ideals or by class consciousness, and some see their work as the foreshadowing of better things to come in the 1960s, once the state attempted to cut the association of cinema and commerce (Sharaf al-Din 1992, 16–21).[18] But aside from gradual concessions to overt nationalism and progressive social ideals in the few directors whose lineage led to the public sector, most Egyptian films remained derivations of genres developed in earlier films, and before that, the theater. Musicals, farces, belly-dance films, and melodramas predominated. At all periods of Egyptian cinema critics and intellectuals have denounced such films as grossly out of touch with the realities of Egyptian society, but at the same time locally made film narratives were rapidly becoming part of social reality whether intellectuals liked it or not. These generic conventions have created a horizon of expectations in the audience that later directors could copy but that they could also use creatively through unorthodox casting or unexpected twists in familiar stories.

| • | • | • |

Cinema As Vernacular Culture

Aside from the work of those directors who ended up becoming prominent in the public sector, the pre-1960s cinema was important in another way: it contributed to a de facto standardization of a national vernacular.[19] The modernity forced on Egypt partly by colonialism and partly by internal social dynamics would have made no sense in the absence of a means to authenticize it. In this respect nationalism is organically linked to modernity—a way to associate the presumed continuity of the past with the cultural ruptures that are inevitably part of modernity.

Joshua Fishman (1972) writes that language is a potent, if not necessarily inevitable, imagined link to a national past. Not surprisingly, one of the symbols of the continuity so important to Egyptian modernity is the Arabic language. But which Arabic? Nationalist ideology in an Arabic-speaking context formally recognizes only written Arabic, which must be conceptually (if not practically) linked with classical Arab society. Actual similarities between modern and medieval written Arabic are another matter, and linguists recognize that modern written Arabic is not identical to the medieval Arabic sometimes described as “classical.” But at the same time, the scope of change permitted modern written Arabic has been sufficiently limited that the gap between it and the vernacular is described as “diglossic.”[20]

Arab nationalism makes a link between territory and language, but the territory associated with Arabic encompasses all presumed speakers of classical Arabic (or its modern standard counterpart)—everyone and no one at the same time. No person speaks classical Arabic in daily life, and relatively few people read it easily (Parkinson 1991). And yet everywhere in the Arabic-speaking world, states have created an institutional apparatus to defend linguistic purity.

In doing so they construct a different relationship between nationalism and vernacular language than one often finds in Europe. The “official language,” as Bourdieu calls it, “is the one which, within the territorial limits of that unit, imposes itself on the whole population as the only legitimate language, especially in situations that are characterized as more officielle (a very exact translation of the word ‘formal’ used by English-speaking linguists)” (1991, 45). Through a combination of official regulation and “normalization,” the standard language is eventually “capable of functioning outside the constraints and without the assistance of the situation, and is suitable for transmitting and decoding by any sender and receiver, who may know nothing of one another” (Bourdieu 1991, 48).

In Arabic-speaking societies the official language was not abstracted from the vernacular of an elite but from a language that was not used in everyday life. Arabic-speaking societies saw a devaluation of nonstandard language similar to that of Europe (Bourdieu 1991, 47), and this devaluation was no doubt reinforced by the development of modern cultural hierarchies along the same lines as those in Europe and America (Levine 1988; Twitchell 1992). In relation to official language the vernacular had to be kept at arm’s length, and was, by definition, not the proper medium for art or print media. But cinema and other nontraditional oral media (the gramophone, theater, and radio) were another matter. In these media the vernacular was never completely banished in constructions of Egyptian nationalism. To the extent that the nation was “imagined” (Anderson 1991) or “narrated” (Bhabha 1990), the medium of expression was both the official language and the vernacular. However, the importance of nontraditional media in constructing Egyptian and Arab nationalism has been substantially unacknowledged by the cultural establishment.

Despite its reputation as a Hollywood clone, Egyptian cinema from the 1920s through the 1950s tried to link itself to an imagery of social synthesis that defined bourgeois culture. This was a synthesis that used the vernacular but often made indirect references to constructs of heritage. In the end pre-1960s Egyptian cinema may have been extremely important in constructing the cultural synthesis of the bourgeoisie. And of course there was a linguistic analogue to bourgeois culture: modern language was also, to some degree, supposed to combine both the vernacular and traditional written Arabic. It is this modern “mixture” that is often identified as “modern standard Arabic.” But written Arabic, the medium of literature, was “mixed” with the vernacular conservatively. The modern variant of written Arabic differs considerably from medieval written Arabic, but most of what counts as writing differs markedly from what people speak. By contrast, the medium of film, spoken Arabic, was the spoken Arabic of Cairene elites rather than written Arabic. And of course a national vernacular based on the dialect of the dominant city is typical of such European nations as England and France. In both cases, and also elsewhere in Europe, Latin was displaced as the language of writing by a synthetic vernacular. But in Egypt both vernacular and classical Arabic had to construct a sense of cultural synthesis without budging too far from the cultural hierarchies that kept each of them distinct.

Just as “modern standard Arabic” used by literate Egyptians differs significantly from the medieval Arabic on which it is based, the vernacular language used in audiovisual media is perhaps not identical to any specific vernacular. However, the vernacular identity constructed in films was frequently linked to both high tradition and to imported technique by visual means. It is not true, contrary to Samir Farid’s claim, that bourgeois men and women depicted in Egyptian films were “Egyptian in their clothes, their accent and manner of speaking,” but not in “traditions and customs, behavior, thoughts, actions and reactions.” Rather, they were often pointedly Western in their appearance, and whatever they were doing in the hundreds of film narratives denounced as mindless or melodramatic, they possessed one immeasurably important avenue into the hearts and minds of mass audiences: they were easily understood by everyone from the illiterate to the most erudite.

At this point I want to return to The Flirtation of Girls, which I want to suggest was an excellent example of the power of commercial cinema to construct a national community. In a nutshell, The Flirtation of Girls connected with its audience by creating a common fund of images tied to a middle-class bourgeois nationalist identity—an image tied to vernacular authenticity, high tradition, and modern technique. Furthermore, the film uses that common fund of images as the preconditions for its production. Let me unpack the film a bit more.

| • | • | • |

The Flirtation of Girls was made in the late 1940s, just after the heady wartime rush to expand film production. As previously mentioned, critics refer derisively to the filmmaking of this period as “the cinema of war profiteers.” Allegedly vast fortunes were made by hoarding scarce commodities and selling them on the black market, and then this illicit money was laundered during and just after the war through financing films. Allegations of money laundering went together with withering criticism of the aesthetic qualities of the films: they were made by people with no experience in cinema, people interested only in quick profit, people who had absolutely no regard for quality. With one or two exceptions films of the period are considered an affront to polite society—an outrageous triumph of the greedy nouveaux riches.

The ultimate source of finance for The Flirtation of Girls is unknown. This is, in many films (and not just Egyptian ones), a rather difficult question. But regardless of the film’s source of finance, The Flirtation of Girls was anything but amateurish. Quick it was, industrial even. The film uses only four or five simple sets, a very brief outdoor scene shot in the garden of a mansion and some back-projected fake outdoor scenes. But everyone associated with the film was a seasoned professional. Indeed, despite its low-budget sets, the film was probably a rather expensive production. The quick postwar expansion of the cinema might have brought inexperienced directors and producers into the industry, but for a film to be marketable it had to have stars. There were a finite number of marketable names who were in demand for a suddenly much larger pool of pictures. Consquently stars could charge higher fees, and The Flirtation of Girls featured not just one but several stars.

The plot turns on education. A rich man hires a seedy and ineffective old schoolteacher (Najib al-Rihani) to tutor his daughter (Layla Murad), who is failing every subject, but most gallingly, she has flunked Arabic. Fortunately the Egyptian educational system allows a second chance for failing students to retake at least some exams during the summer, hence the need for a tutor.

The girl is a flirt, and the old teacher, despite the disparity in age between himself and the girl, falls in love with his student. Once he is hired the rich man buys new clothes for his new employee. Resplendent in a new suit, the formerly shabby Arabic teacher stands with his student and a bevy of “companions” (really Layla Murad’s chorus). One of the companions tap-dances, the others sway suggestively, as Murad sings a saucy “alphabet song” that recapitulates the film’s theme:

The music, credited to Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, is a delightful jazz adaptation with saxophones dominating the accompaniment. The girl’s servant bangs gleefully on a grand piano. Her small white dog sits on the piano barking. Arabic grammar, the putative subject of the song, was never more enjoyable.

Fig. 18. Layla Murad in an elegant publicity still from The Flirtation of Girls (al-Kawakib, September 9, 1958, p. 4). Courtesy of Dar al-Hilal.

Abgad, hawaz, hutti, kalamun

Shakl-il-ustaz ba’a munsagimun

Ustaz Hamam, nahnu zaghalin

Min ghayr ginah binmil wi-ntir

Wil-makri fina tab‘i gamil

in ’ulna “la’i, la’i,” ya‘ni “na‘amun”

In “ga’a Zaydun,” aw “hadar ‘Amrun,”

W-ihna malna, inshallah ma hadarun!

Lil-mubtada ha-ngiblak khabarun,

Bi-nazrah wahda ha-yisbah ‘adam.

ABCDEFG,[21]

Now the professor looks good to me!

Professor Pigeon,[22] we’re tricksters,

We flip and fly without wings,

And in us, deceitfulness is a good thing,

If we say “no, no,” it means “sure thing.”

Even if “Zayd came,” or “‘Amr was present,”

What do we care? maybe he wasn’t!

We’ll get you the “predicate” to your “subject,”

With one glance the whole thing will mean nothing.[23]

It transpires that the girl is distracted by a lover. She lures the old Arabic teacher out of the house by telling him she wants to run away with him. They drive off, or rather she drives (he sits in the passenger seat) in, of all things, an army jeep. Unfortunately it turns out she is only using him to escort her to a shady nightclub where her lover waits. The old Arabic teacher is crestfallen, but when he overhears other denizens of the nightclub talking about how the girl’s lover is only after her money—that she is merely the next in a long line of unfortunate victims of this nightclub Romeo—he tries to intervene. For his trouble he gets thrown out on the street. There he appeals desperately for help from a dashing young pilot who happens to be passing by. The pilot enters the nightclub claiming to be the girl’s paternal cousin, and therefore her logical suitor according to Egyptian custom. Of course, she denies it, but he precipitates a fight anyway in order to “rescue” her. Then they jump into the jeep to deliver the recalcitrant girl back to her father. The pilot starts flirting with her. The old Arabic teacher is dismayed and tries to throw him off the track by stopping at someone else’s house, which he chooses at random. He and the girl knock on the door, leaving the pilot outside.

Fig. 19. The dashing pilot played by Anwar Wajdi (second from left) comes to rescue Layla Murad from her lounge-lizard lover. The lover, played by Mahmud al-Miliji (well on his way to becoming the most prolific screen villain in Egyptian cinema history), stands on the far left. The bumbling old teacher played by Najib al-Rihani appears on the far right (al Kawakib, no. 9, October 1949, p. 60). Courtesy of Dar al-Hilal.

The house turns out to be the residence of a famous actor (Yusuf Wahbi), who is entertaining a rehearsal by a famous singer (Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab). Solemnly the actor imparts words of wisdom to the youngster and to the old teacher who still accompanies her. “Just suppose,” he says, “that a man falls in love with a girl who is too young for him and who is from a different social milieu.” They start to fidget, recognizing immediately that the “just suppose” scenario spun out by the great man refers directly to themselves. By the time the actor is through with his “suppositions,” the old Arabic teacher realizes his folly, and the young girl begins to understand that she has unintentionally hurt him. The crafty actor then ushers the two into an absurdly large auditorium, where his friend the musician is rehearsing a massive orchestra, which includes strings, trumpets, male and female choruses, and even a balalaika section. It is a supremely surreal scene.[24]

Finally the singer, holding a banjo, directs his balalaikas and piccolos, while singing a sad song about pure spiritual love:

Oh eye, why is my night so long Oh eye, why did my tears pour forth Oh my eyes, why did the lovers leave me Why do all eyes sleep except you? . . . I sacrificed my joy for the lover (Choir) (“Oh night witness him.”) I will live on his memory (Choir) (“Oh night witness him.”)[25]

The music makes the old man accept what his heart had known all along—that a match between himself and his student makes no sense—and he gives his blessing to the romance that blossoms between the young girl and the pilot. In the final scene the three of them—the girl, the pilot, and the old man—drive off in the jeep, the camera lingering one final moment on Najib al-Rihani, who is grinning slyly. This was Najib al-Rihani’s last instant on the screen, and the bittersweet look on his face is almost enough to make one think that he knew he wasn’t going to be back. He died in May 1949 of typhoid (Abou Saif 1969, 273). In October the film was released.[26]

The Flirtation of Girls was hugely successful, but of course that hardly invalidates the criticisms made about films of the period: they were supposed to make money, at least enough to launder the ill-gotten gains of the shadowy investors. And the film is, in fact, still popular—a powerful engine of nostalgia that everyone has seen, one that brings smiles whenever it is mentioned. However, what is interesting about The Flirtation of Girls is not just that it sustains nostalgia but that it invoked nostalgia from the very first day it was exhibited to the public. The film is essentially an all-star revue. All of the principals were extremely well known, and many of the small roles were cameos by performers who were also known, or who, intriguingly, were about to become well known in the next decade. And almost all of them played themselves in the film, either in the sense that their characters bore the names by which they were known in public or in the sense that their roles in the film as actors or singers were identical to their roles in real life.

The film was a musical featuring Layla Murad, who played the young girl. She was in fact a bit long in the tooth for this role. Layla was the daughter of a well-known singer named Zaki Murad, and she began singing as a child in the early 1930s. One of her first public appearances was in the nightclub of Badi‘a Masabni, an impresaria of Syrian origin who had been married at one point in her career to the comedian Najib al-Rihani. Al-Rihani was the actor who played the seedy old tutor in The Flirtation of Girls. Earlier in his career he was famous for a stage persona, which he performed live, on the radio, and in films, named Kishkish Bey. Al-Rihani’s Kishkish character dressed in the rustic clothes of a provincial village headman (‘umda) and was an old man with an eye for young, particularly foreign, women. The plays in which the character of Kishkish appeared were comedies known as “Franco-Arab revue,” a genre inspired by French farce that was popular around the time of World War I (Abou Saif 1969, 33–60). Another of the ironies evoked by The Flirtation of Girls lay in al-Rihani not getting the girl at the end; in most of al-Rihani’s Franco-Arab comedies the ending “celebrates his triumphant sexual union with a young beauty” (Abou Saif 1969, 56).

Fig. 20. Najib al-Rihani in The Flirtation of Girls. His countrified Kishkish Bey persona is obviously not part of this film, but his famous penchant for pretty (and Westernized) girls is on display. (al-Kawakib, no. 6, July 1949, p. 6). Courtesy of Dar al-Hilal.

For a time the Franco-Arab comedy pioneered by al-Rihani played an important role in satirizing the social and political issues of the day, particularly during the heady days of the 1919 revolt against British rule. Abou Saif describes Franco-Arab comedy in largely sympathetic terms, but he also notes (1969, 76–77) that the genre was artistically limited by its tendency to string together unconnected “situations” with a series of song-and-dance spectacles.

Clearly the structure, if not the content, of The Flirtation of Girls owed a great deal to the earlier genre. The film, produced almost thirty years after the heyday of Franco-Arab comedy, is also a series of song-and-dance spectacles punctuated by the barest of plots. But the film contains few if any obvious references to politics, whereas Franco-Arab revue thrived on commentary about current events. Abou Saif quotes Badi‘ Khayri, author of The Flirtation of Girls and of many of al-Rihani’s most successful Franco-Arab comedies, as saying that Franco-Arab revues were “cinema newsreels because, whenever possible, they were connected with an important crisis” (1969, 73). There was, then, no obvious satire of the sort that could get through to an American audience. But the significance of the actors and the structure of the film may well have been quite different for an Egyptian audience in 1949. The film is, in many ways, too “different” to communicate difference cross-culturally. To an American audience it looks like little more than a cross between 1930s screwball comedy and Parisian boulevard theater. But half of the film’s fun comes from its implicit links to earlier works that were indelibly associated with specifically Egyptian meanings.

Layla Murad had appeared in a number of films—approximately twenty up to that point. Her first appearance was in Long Live Love (Karim 1938), and she was paired with none other than Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, who was the foremost male vocalist from the 1920s through the mid-1940s. And ‘Abd al-Wahhab, of course, was the singer in The Flirtation of Girls who was rehearsing in the actor’s mansion that Najib al-Rihani used to try to escape from the young pilot. ‘Abd al-Wahhab sang one song in The Flirtation of Girls, and it was his second-to-last significant appearance in a fiction film, although he lived another forty years.[27]

The owner of the mansion in The Flirtation of Girls was, in the story, a highly successful actor named Yusuf Wahbi. And he was playing himself: the real Yusuf Wahbi was, in fact, a highly successful actor, director, and playwright. Wahbi was the childhood friend of the man who directed all of the singer Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s films. Wahbi’s role in the film was to play matchmaker. He makes Najib al-Rihani see that an affair between him and this vivacious young girl is inappropriate and that she should really be encouraged to marry the dashing young pilot. At one point Wahbi scolds al-Rihani, telling him that if he really loved the girl he would step aside and let the pilot have her. But there are certain reverberations to Wahbi’s admonition: when he says, “If you really loved her you’d step aside,” he isn’t just referring to Najib al-Rihani in The Flirtation of Girls. Wahbi is also referring slyly to himself. He had already “married” Layla Murad twice before in two of their films: Layla bint al-rif (Layla, Daughter of the Countryside; Mizrahi 1941) and Layla bint madaris (Layla, Daughter of Schools; Mizrahi 1941). This kind of intertextuality was very deliberate and calculated to play on the audience’s knowledge of all of their previous work.

In the film Wahbi not only tied himself to Layla Murad, he also tied The Flirtation of Girls in to the history of Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, the singer rehearsing his orchestra in Wahbi’s mansion. This happens as Wahbi is playing matchmaker between Layla, his former celluloid lover, and the dashing young pilot. In the middle of the conversation between himself, Najib al-Rihani, and Layla Murad, he suddenly stops and says, “‘Abd al-Wahhab is about to begin his new piece.” They go to the auditorium in Wahbi’s house and peek through the door. Layla asks him what the piece is about, and Wahbi replies, “It’s a sad tale about a man who loves a woman more than anything, but he’s forced to withdraw from her life for the sake of her happiness, and then watch them from afar, with his heart breaking.” Of course, this is what The Flirtation of Girls is leading up to: the schoolteacher is going to have to give up his dream of marrying the girl so that she can be happy living with the dashing young pilot. Then ‘Abd al-Wahhab sings his song, which once again reiterates the theme of a lover sacrificing his dreams for the sake of a woman’s happiness.

What is not so evident on the surface here in America, but was not lost on an Egyptian audience of 1949, is that Wahbi is also describing the plot of Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s first film, al-Warda al-bayda’ (The White Rose), which was made in 1933 and directed by Wahbi’s childhood friend Muhammad Karim. The man who plays Layla’s father in The Flirtation of Girls was Sulayman Najib, who was the same actor who played the father of ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s lover in The White Rose.

At this point one should remember that one of the most common excuses given by scholars and critics for ignoring the Egyptian cinema is that the commercial Egyptian cinema is nothing but a Hollywood clone. It is true that The Flirtation of Girls looks very much like an American screwball comedy starring Cary Grant or Katherine Hepburn. But beneath the surface there is an intricate architecture of references designed to evoke not an alien film tradition but Egypt’s own tradition. This was a carefully calculated effect.

No doubt it was also calculated to make money, but it is hard to see why this should exclude it and other films from consideration as a powerful force for constructing nationalism and, by extension, modernity. After all, Benedict Anderson’s focus on print capitalism made “imagined communities” practically a household word, at least in academic households, and the books and articles his insight generated are practically a cottage industry. What we are seeing in the commercial Egyptian cinema is a kind of screen capitalism that is not greatly preceded by either the printing press or mass literacy.

Anderson suggests that the introduction of a new medium in a capitalist context results in new markets, which are inevitably exhausted. When Europeans began using the printing press, the market for writing was still primarily in Latin, a wide but thin market that was tapped out within a century and a half. However, “the logic of capitalism thus meant that once the elite Latin market was saturated, the potentially huge markets represented by the monoglot masses would beckon” (Anderson 1991, 38). In the case of Arabic-speaking societies, there are no precise estimates even for the size of the market for standard language. Ami Ayalon (1995, 142) notes that a 1937 Egyptian census reports a literacy rate of 18 percent. But he cautions against generalizing from such figures on a number of grounds. For one thing, literacy was localized: educated people were concentrated in cities. Furthermore, there is no qualitative measure of literacy: “The classification ‘literate’ did not necessarily imply the ability to read a newspaper; often it was merely a designation for someone who had memorized certain sections of the Qur’an” (Ayalon 1995, 142). However, there was also an unquantifiable “multiplier effect”—literates reading to others who were not able. Estimates of the circulation of printed materials are also imprecise, but in the case of newspapers (a critical medium both for Anderson and for Arab linguistic reformers), Ayalon writes that “it is safe to assume that at no time prior to the second half of the twentieth century were newspapers bought by more than …3 to 4 percent of the population in Egypt” (1995, 153).

The standard language of mass print and the vernacular used in other media were introduced to the Egyptian public at very nearly the same time. In Europe the potential complications caused by the advent of new types of media not predicated on the written word come much later; print and the cinema are separated by centuries. In Egypt it might be stretching a point to say that print and the cinema are separated even by decades.

| • | • | • |

Let us return to Yusuf Wahbi and The Flirtation of Girls. As mentioned above, Wahbi’s relationship to the other actors in the film was predicated on a rich intertextuality—but an intertextuality of film and theater texts. Wahbi’s work was not exclusively in either literary Arabic or colloquial Arabic, although by the late 1920s he is alleged to have “descended to the level of the masses by doing plays in colloquial” (al-Yusuf [1953] 1976, 88). His characters were frequently at least aristocratic, and in this film he ties the aristocracy firmly to official language. In his cameo appearance he speaks a sonorous semiclassical Arabic that invokes—really almost caricatures—high culture, and in so doing he reiterates a point that had already been raised in the film’s plot. Layla, we remember, was thrown together with Najib al-Rihani because she had flunked Arabic—proper written Arabic. Now we have Wahbi showing her just how sexy Arabic can be. She practically swoons in front of him. And in the larger scheme of things, Wahbi’s classicism makes a nice contrast to al-Rihani’s clever colloquialisms. At one point Wahbi explicitly juxtaposes the two. First he quotes classical Arabic, saying, “Wa-kullu muradi an takuna hani’atan wa-law annani dahaytu nura hayati” (All I want is that you be happy, even if I have to sacrifice the light of my life). Then Wahbi repeats the sentiment in colloquial Arabic, “Wilad al-balad biy’ulu, Iza kan habibak bi-khayr, tifrahluh” (Common people say, “If your loved one is well then you should be happy”). Furthermore, the juxtaposition of classical and vernacular elements in Wahbi’s speech was rounded off by the presence of the dashing young pilot, who adds technological know-how to the other elements of national identity. The film is, in other words, an archetypal expression of nationalist and modernist ideology: one part authenticizing vernacular tradition; one part classical high culture; and one part technological innovation.

The history of Yusuf Wahbi leads to more intertextual connections between the film’s actors and characters, not that the two can really be kept separate. In the 1920s Wahbi had founded a theatrical company called the Ramsis Troupe. The names of the actors who got their introduction to show business through the Ramsis Troupe would practically make a “who’s who” list for the Egyptian theater and cinema. One of the most successful alumni of the Ramsis Troupe was an actor and film director named Anwar Wajdi. Wajdi, like his mentor Yusuf Wahbi, had also played the romantic lead in a couple of Layla Murad films, including Layla bint al-aghniya’ (Layla, Daughter of the Rich; Wajdi 1946), which was an adaptation of It Happened One Night, and Layla bint al-fuqara’ (Layla, Daughter of the Poor; Wajdi 1945). In real life Wajdi was Layla Murad’s husband. And finally, Wajdi also played the dashing young pilot in The Flirtation of Girls. Not only that, he was the director. And the producer.

Fig. 21. A publicity still from an advertisement for The Flirtation of Girls. the five stars are seated before the door of the theater in which Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab is shown rehearsing in the film. From left to right: Najib al-Rihani, Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, Anwar Wadji (standing), Yusuf Wahbi, Layla Murad. Courtesy of Dar al-Hilal.

All these names and connections are important. If one added up all the songs, plays, films, and radio programs that featured Layla Murad, Najib al-Rihani, Anwar Wajdi, Yusuf Wahbi, and Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab, the total would number at least in the hundreds. Virtually all of this work was in the vernacular, and although films, songs, and radio programs are never extensively analyzed in discussions of Egyptian nationalism, they did constitute a common fund of images with which the audience was intimately familiar. The experience of this imagery was analogous to the mass rituals of reading novels and newspapers that Benedict Anderson (1991) identifies as an important means for knitting together “communities” of anonymous strangers. But more than the newspaper or novel, this film and others like it were intensely reflexive. The Flirtation of Girls was not really about anything other than itself. It was “about” primarily the popularity of the actors, and of course their popularity was built on the audience’s informal experience with them. A very large proportion of the combined body of work of the actors and filmmakers who made The Flirtation of Girls was like the film itself in that their work had no direct connection to the imagery of vernacular culture normally emphasized in the implicit opposition between high literate culture and the “authentic” vernacular culture. This was Egyptian nationalism in the making. It was a completely synthetic system of communication that was instrumental in defining what Egypt was, and furthermore, a system of communication that lay partially outside the formal apparatus for teaching legitimate culture.

| • | • | • |

Down With Vulgarity

What happened to the Egyptian cinema after the 1940s? In terms of the political economy of filmmaking, the story of the decade following The Flirtation of Girls is the subject of the preceding chapter by Robert Vitalis in this volume. The state took over the industry by the 1960s, or more accurately, took over most of it. Proponents of the public sector see this as an inevitable result of film economics in Egypt and the Arabic-speaking world (Salih 1986, 205). Several years before the Free Officers revolution of 1952, the very success of the Egyptian film industry began to seriously affect production costs. As the product became more popular and the number of films increased, stars began to understand their market value. Even those less enamored of state intervention agree that profitability became a problem shortly after the first rush of expansion during and just after the war. For example, Samir Farid (1996, 8) writes that by the postwar period Layla Murad’s fee jumped to £E12,000, almost half of an average film budget of £E25,000. A few other stars, including ‘Abd al-Wahhab, could charge even more. Yusuf Wahbi accepted £E1,000 for his very brief appearance as himself in The Flirtation of Girls, but only on the condition that his part be filmed in one day (Hasanayn 1993, 72).

As production costs went up, the potential for making a profit on films went down. At the Centennial festival Tawfiq Salih claimed that before the 1940s a film covered its cost from the domestic market and made profits from foreign distribution. By the 1950s the foreign market had to cover part of the production costs as well. American and European films returned to the market. And to make things worse, as the Nasser regime consolidated power and began to broadcast revolutionary rhetoric (in a few films), some of the Arab states closed their markets to Egyptian product (Salih 1986, 205; Farid 1996, 9). In the view of Salih and other advocates of nationalization, these economic woes were largely responsible for what they saw as the poor aesthetic quality of Egyptian films. And it was particularly the hold of non-Egyptians (but as Vitalis reminds us, not necessarily Hollywood) over the vital profit margin that spoiled the cinema. In the 1940s foreigners dictated that most films would be musicals. Another source of indirect foreign meddling, according to Salih, was the effect of British money during the war. Abu Sayf described the problem bluntly:

Tasteless producers catered to a low-class audience, which had also been enriched by the British war effort (Salih 1986, 196).[28] Lebanese producers, who Salih and others say were interested only in quick profits, put another nail in the coffin of “quality” Egyptian cinema. Lazy directors, who adapted foreign films rather than pay writers to produce scripts, then combined with the marketability of dancers, slapstick comedy, and melodrama, in what some see as a powerful alchemy of tastelessness. This provided an aesthetic argument for nationalization that paralleled the economic argument.[29]Nobody who has written about the “crisis of the Egyptian cinema” has investigated the causes of the crisis. The first reason is that the number of cinema production companies increased in Egypt during World War II because of the entry of war profiteers into the field of cinema production. They were eager to exploit the money they made without any of them knowing the slightest thing about filmmaking. This led to chaos that helped destroy the Egyptian film, causing an increase in competition for artists, thereby raising their fees to unimaginable levels. It also increased the cost of studios, developing labs, and raw film, and led to a doubling in production costs. (1949, 17)

Nationalization was already on the minds of many by the time The Flirtation of Girls was produced. Salah Abu Sayf, one of the most respected directors of the 1950s, was calling publicly by 1949 for extensive government intervention to alleviate the “crisis” in the film industry. He suggested a ten-point program, which is paraphrased below.

- Stipulate a minimum capitalization of production companies at £E50,000. Companies will merge, and having fewer companies will reduce unfair competition.

- Form a government committee that would include representatives of the artistic unions to limit the prices of the studios, labs, raw film, and actors’ fees.

- Create a cinema institute to prepare new talent for the screen.

- Send film students on artistic study missions to Europe or America to study the cinema as a craft and an art so that when they return they can teach in the cinema institute.

- The government should set aside a large sum of prize money for the best screenplay.

- Lessen censorship. Many of the conditions of the current censorship were mandated during the period of colonial protectorship.

- Allow the formation of unions organized by workers in the cinema industry.

- Open new markets for Egyptian films, and lessen the hold of hard currency.

- Exempt films from taxes.

- Negotiate with the countries that show films in Egypt and demand that they open their markets to Egyptian films. (Abu Sayf 1949, 17)[30]

But Abu Sayf perhaps got more than he bargained for (a point reiterated by Vitalis, chap. 12, this volume). In 1963 the Nasser regime ordered a large-scale nationalization of the film industry. Most crucially, the studios, development labs, theaters, and distribution facilities ended up in government hands, and Abu Sayf himself was appointed the first director of production in the new public sector. If the economics of filmmaking in Egypt had been in crisis in the late 1940s when Abu Sayf proposed government intervention, the intervention itself in the 1960s threw the industry into complete chaos.

The sudden decree to nationalize seems to have taken everyone by surprise. Sharaf al-Din (1992, 39) notes that the broad aim of nationalization in the early 1960s was to target industries in which a large portion of the necessary capital was in foreign hands but that the cinema did not fit in this category. Minister of Culture Tharwat ‘Ukasha (1959–62)[31] said essentially the same:

The result of what ‘Ukasha characterizes as runaway nationalization was that prices for everything shot through the roof. Salih relates a story told to him by Salah Abu Sayf during the 1940s, when The Flirtation of Girls was made: “Abu Sayf went to a producer and asked for £E40 for a scenarist. The producer said, ‘What do you mean “scenarist”? We produced such and such a film without paying anything for the scenario.’ Abu Sayf said, ‘For the story,’ and the producer replied, ‘I’ve never paid for a story’” (Salih 1986, 201). By the 1960s the pendulum had swung the other way:Up to September 1962 when I left the Ministry of Culture there was no thought of nationalizing the cinema, or of the state taking over film production because it would have slid into endless troubles [if it had been done] without prior preparation. Perhaps the subsequent unstudied haste to dominate the cinema is what led to the state’s imprudent intrusion into the field of film production. Many factors contributed to this tendency and swept the Egyptian cinema into a new phase. (Quoted in Sharaf al-Din 1992, 40)

Any person working in the press as a critic could sell a story the following day. The public sector bought close to 500 stories that never saw production, and they were paid for, or at least partially paid for. We have an Egyptian proverb that says “Loose money teaches people sin.”…Expenses for the cinema increased because the people making films were saying, “That’s government money.” (Salih 1986, 207–8)

But in terms of the content of films, nationalization opened the doors to directors who wanted to make films that were autonomous works of art. Many of these films deliberately cut their links to the traditions of commercial Egyptian cinema, and many of these films have been well received in foreign film festivals. Unfortunately, by 1970 the public sector collapsed, leaving a bankrupt industry.[32] The state withdrew from direct financing of film projects, although it has always maintained a grip on the facilities for producing films.

| • | • | • |

Back to the Future

Eventually Egyptian filmmakers reestablished their links with the earlier traditions of commercial cinema. The much-maligned star system returned, and so too did the potential for clever directors to exploit the intertextuality of actors and previous films.

Shortly after the Centennial festival I became involved in planning another film festival, this time for Egyptian films exclusively. I was fascinated to see that one of the films we chose for our festival was full of references to earlier films. The film is Ya dunya ya gharami (O Life, My Passion; Ahmad 1996), the debut film of Majdi ‘Ali Ahmad.

The title comes from a song in Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s third film, Yahya al-hubb (Long Live Love; Karim 1938). Long Live Love, as mentioned above, was also Layla Murad’s first film. It is a cheery story in which ‘Abd al-Wahhab plays an aristocrat who works as a bank clerk, hiding his true identity so that people will judge him on personal merit rather than by his social station. In the course of the film he marries an aristocratic woman (Murad), and of course when his true identity is revealed everybody lives happily ever after.[33]

O Life, My Passion, by contrast, is about three single women with no male guardians. In the film the three struggle to find mates in a social system that has allotted them few assets. Their potential husbands range from an exuberant con man to a prudish hypocrite. As in Long Live Love, hidden identities play a role in several characters, but in O Life, My Passion, secrets revealed always lead to a reality that is less than the appearance rather than more. The ending is neither happy nor sad; rather it is filled with ambiguity, as two of the three women are forced to marry men who are less than perfect.

O Life, My Passion has enough visual presence to do very well on the film festival circuit.[34] Furthermore, it sensitively and humanely portrays the lives of women in a Middle Eastern society, a topic that preoccupies Americans both in and outside of academia. The film is well acted and intelligently directed and was also extremely popular in Egypt. But what fascinated me most was the final scene. The story ends with one of the three women getting knifed by an angry fundamentalist. Fortunately she survives. We see her waking up in the hospital with her two friends by her side. Of course, they ask her, “How do you feel?” The stricken woman replies, “I feel like I’m headed for a disaster” (Hasis bi-musiba gayya-li). Then she says, “Oh God, oh God” (Ya latif, ya latif). The women in the scene express their concern for each other and their relief that the worst had not happened in “commercial filmese.” The exchange is from a film, and the film happens to be none other than The Flirtation of Girls. In the original Layla Murad and Najib al-Rihani are in her jeep. Al-Rihani does not yet know it, but they are going to Layla’s tryst with her nightclub lover. On the way they sing a delightful duet in which Layla asks al-Rihani, “How do you feel?” His reply: “I feel like I’m headed for a disaster.” And Layla replies, “Ya latif, ya latif.” From the title almost to the last line—these are just two of many examples, and there are doubtless many that I, as an outsider, missed—O Life, My Passion lives through other works, just as The Flirtation of Girls had in 1949. It portrays a social world that is also defined partly through works of popular culture.

Bourdieu describes the “autonomy of artistic production” as one of the conventional diacritica of pure taste. But the autonomy of art, he says, obscures its social embeddedness: “An art which ever increasingly contains reference to its own history demands to be perceived historically; it asks to be referred not to an external referent, the represented or designated ‘reality’, but to the universe of past and present works of art” (1984, 3). The Flirtation of Girls was born within just such a universe, but of course it was driven very much by the historically developed canons not of elite sensibilities but of popular taste. One of the hallmarks of a modern sensibility is that producers of art concede Bourdieu’s point: they produce works that foreground the universe of past and present works of art rather than attempt to obscure it beneath the “pure intention of the artist…who aims to be autonomous” (Bourdieu 1984, 3). We tend to call this “postmodern,” but perhaps the same dynamics are at work in other places and at other times.

What the director of O Life, My Passion has done is to find a way to make creative use of his own filmmaking tradition, and at the same time to make the film appealing to a foreign audience. It is an acknowledgment that there is, after all, some value in those three thousand films that came before. One hopes this is a sign that the Egyptian cinema will both survive and retain its unique character. Like all Third World film industries, Egypt will have to market its films in metropolitan markets in order to survive, because the economics of the local market will not sustain the industry. The omnipresence of the dreaded Hollywood global juggernaut is only one of the threats faced by the beleaguered Egyptian national film industry. The inability of the Egyptian government to exert any effective pressure on Arab governments to pay a fair price for Egyptian entertainment product is another. Furthermore, no Arab government, Egyptian or otherwise, has shown the slightest interest in policing video piracy. The American government too has turned a blind eye to piracy of Egyptian films on American soil, thereby rendering a potentially lucrative expatriate Arab market null and void as far as the film producers are concerned.[35]

Making films for exhibition in the United States, even if only in the limited circuit of universities and art houses, forces nonmetropolitan filmmakers to choose between making films with general appeal in their countries of origin and making films oriented primarily toward interpreting their culture to foreign audiences. Sometimes filmmakers can have their cake and eat it too. At the Centennial festival Ferid Boughedir emphasized that his films are shown in Tunisia and do quite well there. Summer in La Goulette will not, however, be shown widely in the Arabic-speaking world outside of Tunisia because it features a number of scenes with nudity. Ultimately the multicultural world elaborated in the film works better in New York than anywhere else.

More often the choice between specialist metropolitan and general national audiences is cast in terms favorable to the metropole—as between art and commerce. Films from other national film traditions shown here are shown because we think they are art. As the Cineaste editorial put it, they are “at least the best of them.” By default the Egyptian cinema, as the only significant commercial film industry of the Arabic-speaking world, is given the role of the villain in this artistic economy. Egyptian and Arab intellectuals are full partners in casting this drama. Boughedir, Salih, and all the other filmmakers and critics at the festival were eager to proclaim their distance from the conventions of Egyptian cinema, but in doing so they perhaps inadvertently withheld the tools a metropolitan audience needed to appreciate one of the most strikingly different films shown in the festival.

Metropolitan film festivals sell themselves as glimpses into worlds of difference. And yet films like The Flirtation of Girls were dismissed as nothing more than Hollywood clones, leaving the audience to question, like the man in the lobby between The Flirtation of Girls and Summer in La Goulette, why it was subjected to what was essentially, by the standards of the festival’s expert opinion, a bad film. The answer is that the organizers of the festival were wiser than their experts. The Flirtation of Girls is a great film, if not a film that a metropolitan audience can easily view without mediation.

Notes

This chapter was initially conceived and written at Princeton University in the 1996–97 academic year, when I was a visiting fellow at the Institute for the Transregional Study of the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. My initial impressions of the films were formed in the company of Ted Swedenburg, with whom I attended the Centennial festival in New York City. Versions of the chapter were presented at the Columbia Society of Fellows and at the Middle East Center of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA); the manuscript benefited from comments by Anne Waters (at Columbia) and James Gelvin (at UCLA) and by the students and faculty who attended the lectures at both institutions. Thanks are also due to Robert Vitalis and Roberta Dougherty, both of whom read the manuscript and gave valuable suggestions for changes. And finally I wish to thank Susan Ossman and Gregory Starrett (the reviewers from the University of California Press, both of whom waived anonymity on their reports) for their comments.

1. For example, the film critic Samir Farid is less sanguine about the success of public-sector film production than many. He views many films of the period as “propaganda” (Farid 1996, 12). Farid is particularly harsh on films produced before 1968, although he dispenses relatively grudging praise even to the best public-sector films made between 1968 and 1970. It is the later public-sector films that are most often identified by proponents of the period as masterpieces. Even supporters of the public sector concede that the early years were at best chaotic (e.g., Salih 1986, 206–8). Farid’s negative opinions on the public sector are likely to be seen by many as particularly controversial. In the editorial notes to Farid’s article Alia Arasoughly (1996, 18) cites a number of articles that argue, contrary to Farid, in favor of the public sector. Informally one encounters such polarized feelings about the public sector very often. The issue serves very easily as a lightning rod on political stances toward the Nasser regime.

2. Nor is the social basis of artistic hierarchies universally accepted in the West. Richard Jenkins (1992, 137) describes Bourdieu’s agenda in Distinction as “dissolving culture into culture”—in other words, refusing the absolute separation of high culture from society. Jenkins suggests that while the sociological basis of the judgment of taste may not be in question to social scientists, “some art historians and critics—and many more of their readers (not to mention those who do not read, but know what is art and what isn’t)—certainly do [believe in an ahistorical and nonsociological aesthetic sense]” (1992, 137; italics in original). Levine (1988), for his part, approaches the problem of artistic canons through an examination of how Shakespeare was transformed in Victorian-era America from popular theater into an icon of “elevated” art that required the mediation of specialists. Their questioning of the “naturalness” of highbrow/lowbrow distinctions is certainly relevant to the analysis of Middle Eastern mediated popular culture, where even social scientists (let alone literary specialists and art historians) have barely begun to analyze contemporary Middle Eastern popular culture in a wider sociological context.

3. The festival took place from November 1 to December 5, 1996, at the Lincoln Center and was co-curated by Alia Arasoughly and Richard Peña.

4. It can be argued that all of the post–public-sector directors were, to some degree, products of the 1960s. Whether their work reacts favorably or unfavorably to what each director sees as the legacy of the period, none of them can afford not to have a position on the ideals of the period.