1. Initial Considerations

“Public text” names the Fatimid practice of writing signs in Arabic.[1] It was, I shall argue, a socially and politically intensified use of writing in contrast to the practices of other societies in the eastern Mediterranean. In fact, the Fatimids made writing a significant public art. This study of the art of the public text explores how the Fatimid ruling group extended the use of writing in their capital of Cairo (969–1171 C.E. / A.H. 386–567) to support their political and hegemonic interests. It demonstrates how that extended range of writing signs became a visual legacy continually reiterated by ruling groups within a restricted area of Cairo.

For the Fatimids, every written sign in the public space was a public text: an officially sponsored writing addressed to a public audience which continuously reminded the viewers of the official Fatimid position. The phrase “Fatimid practice” also encompasses the new ways in which Fatimid patrons used writing as a visually significant sign on the interiors of the sectarian buildings they sponsored. For a period of almost two hundred years in Cairo, writing signs was a Fatimid gesture: Fatimid power, Fatimid community, Fatimid territory.

Because the time in which the public text flourished and the places where it was displayed were relatively limited, and because the buildings on which the writings were displayed and the cloths into which the messages were woven have not survived as well as one could wish, the idea of the public text may seem too well argued from too narrow a base. I think not. But the limitations make desirable some initial considerations of terms and ideas that create a conceptual framework enabling one to see and appreciate the power and uniqueness of the Fatimid public text.

First among these is the idea of space, public and sectarian spaces, and of what was included and what was rejected from the writings extant or known to have existed in each space. This study looks closely at the messages displayed in each to see if and how they changed over time. Next, after considering the corpus of these writings and understanding the nature of the spaces in which they were displayed, we need to consider the objects and materials on which the writing was presented. Third, we come to the central idea of this interpretation—how these writings made their meanings. These writings consisted primarily of Qur’nic quotations, secular salutations, names and titles of sponsors, and similar simple and familiar short passages. What is important is the paradigm used to explore the possible meanings these group-addressed writings conveyed to the observers.

Finally, as part of the discussion of meaning, I explore briefly the idea of “contextual literacy,” important to understanding how the Fatimids were able to address the diverse populations of Cairo with their systematic displays of writing in Arabic. These initial considerations make possible the close analysis of writing in Arabic and other languages in the eastern Mediterranean of which the Fatimid public text is the special focus.

In the eastern Mediterranean for millennia before the Fatimids came to Cairo in 969, writing was used for a variety of purposes.[2] Embedded in specific social institutions, writing was sponsored by various groups. Lists, tables, and business records helped commerce thrive. Notation systems stored mathematical and scientific knowledge. Essay-texts were developed to record philosophy, history, and myth. And Roman authorities put writing on the entablatures of the central buildings of the fora, and displayed letters on banners and standards in military processions.[3] That the Fatimids used writing in the extensive networks of their social organization was clearly not of itself a new practice in the eastern Mediterranean.

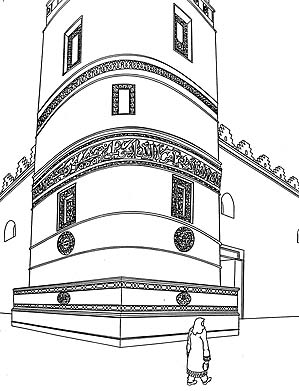

But to the eyes of Cairene beholders, the writing on the exterior of the minarets of the mosque of al-Ḥākim in the year 1002/393 (fig. 1) presented a significant departure in the conventional uses of writing because it was used to address a group audience in public space. Writing in Arabic was displayed on this structure in a highly visible format and on stone and marble, permanent and expensive materials, in contrast to the limited uses of writing in public space by previous and contemporary Muslim and Christian rulers in the eastern Mediterranean for some four hundred years and, in fact, even with the earlier Fatimid practice itself.[4] Generally speaking, before the change signaled by the writing signs on the mosque of al-Ḥākim, those in authority displayed writing in public spaces only in limited fashion, placing them at urban thresholds and on lintels over the entrances of some major buildings. Those who passed the exterior of the mosque of al-Ḥākim in 1002/393 witnessed some of the significant first steps taken by the Fatimid ruling group to use written signs actively to define urban spaces and to convey meaning to public audiences in the Fatimid capital area of Egypt.

Fig. 1. Northern minaret, mosque of al-Ḥākim

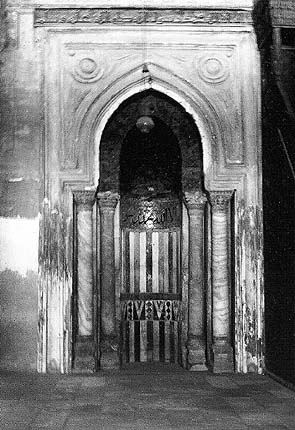

In addition to this display of writing in the public space, Muslim beholders, especially those who were part of the Fatimid ruling group, witnessed another change in the use of writing—one that occurred inside the same mosque, an Ismā‘īlī Muslim sectarian structure. Those who entered the mosque of al-Ḥākim saw displayed on its interior writing larger in scale than that in other mosques in the capital area (fig. 2). But size was not the sole factor that signaled the change in the use of writing. The format, or the manner of display, set it apart from writing on the interior of earlier structures. In the interior of the mosque of al-Ḥākim, writing relatively large in scale for the practices of the time and place framed the architectural features almost unencumbered by other design elements, whereas in the interior of the earlier Fatimid mosque in Cairo, al-Azhar, writing small in scale framed depictions of plants and trees (fig. 3). In addition, the writing in the interior of the mosque of al-Ḥākim differed from the display of writing in the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn, the large congregational mosque built in the ninth/third century in al-Qaṭā’i‘,, south of the Fatimid royal city. There, writing had been used in a limited way in the mihrab area of the sanctuary, but not to fill the ornamental border running around the architectural features of the mosque (fig. 4).

Sanctuary, mosque of al-Ḥākim

Interior, sanctuary, al-Azhar mosque

Original mihrab, mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn

The choice of the mosque of al-Ḥākim as the site for a manifestation of this shift in the uses of writing related in very direct ways to the structure itself and to the political and hegemonic features of Fatimid society of the time. These specific relationships are taken up in chapter 3. But what is relevant here is an understanding that writing outside and writing inside the mosque addressed different, and overlapping, audiences. The kind of group that could be addressed in a public space by the writing on the exterior of the mosque of al-Ḥākim, or in the public processions the Fatimids sponsored, was critically different from the group addressed inside the sectarian space, the Ismā‘īlī mosque. In this study, the two adjectives “public” and “sectarian” are used to denote spaces of contrasting accessibility.

Public space, as distinct from sectarian space, is where anyone—or everyone—could pass. That is, public space is accessible to the whole membership of the society, ruling and ruled, traders, servants, foreigners, Muslims, Jews, Christians, men, and women. Thus the act of putting writing in Arabic, in several places at pedestrian level, and in large scale letters on the minarets of the mosque of al-Ḥākim, itself located outside the royal city of Cairo, made that writing viewable by all who passed that public space. That writing was (and is) in that sense a public text.

Likewise, the writing in Arabic displayed on the clothing of the Fatimid ruling group, and on the trappings of their horses during official processions, was intended to impress those who watched the ceremonies from the public space, that is, mainly those from the urban complex of Cairo-Miṣr who watched along the route of the parade. One such spectator, Nāṣir-i Khusraw, visiting Cairo in 1047/439, during the reign of the Imām-Caliph al-Mustanṣir, has left us a clear account of one of those processions. He found the use of writing on textiles and clothing remarkable, describing with care the cortege of ten thousand horses whose saddlecloths had the name of the ruler woven into their borders.[5] Such systematic display of writing in public space seems not to have been paralleled in other Muslim or Christian practice.[6]

Sectarian space, by contrast, is group-specific space. It is a space where people of similar beliefs gathered in an official communal manner. In the societies covered by this study, sectarian space was mainly space for the gathering of members of religious groups: mosques, churches of various denominations, synagogues, and shrines.[7] These are the spaces where the main ritual ceremonies cementing communal life were enacted for the members of the group. Sectarian space was frequented only by members of that group, and, characteristically, one did not enter another’s sectarian space, whether or not written rules governing such access existed. We know, for example, that the mosque of al-Azhar, within the royal city of Cairo, was a space intended for Ismā‘īlī prayer, sermons, and observances. Non-Ismā‘īlī Muslims would not usually have frequented this space for prayer because many practices, beginning with the specific manner of washing before prayer, varied from their own observances. Clearly, that mosque was not only a Muslim sectarian space, but in the time of the Fatimids, a specifically Ismā‘īlī Muslim sectarian space.

Before the changes initiated by the Fatimids most officially sponsored writing addressed to a group audience was placed inside sectarian spaces. Moreover, even within that space, writing was subordinate in visual importance to other signs of power displayed there. In Christian churches of all rites (e.g., Greek Orthodox, Armenian, etc.) and in mosques and shrines (e.g., the Great Mosque of Damascus, al-Azhar, and the Dome of the Rock), writing framed depictions of landscapes, biblical figures or foliage, and, in general, was subordinate in visual importance within the interior setting. Fatimid practice, beginning with the mosque of al-Ḥākim, shifted the role of writing on the interior of Muslim communal structures. By a dramatic use of writing, that is, by making writing on the interior walls of that mosque larger in scale than any previous writing similarly positioned, and by reducing the number of competing signs of power, the Fatimids began to make the Muslim sectarian spaces they patronized visually dissimilar from other sectarian spaces, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim. These changes in the role of writing were apparent primarily to the Muslim members of the society who frequented that sectarian space. In the sectarian spaces of the Christians and Jews in Fatimid society, writing practices seem to have remained traditional.

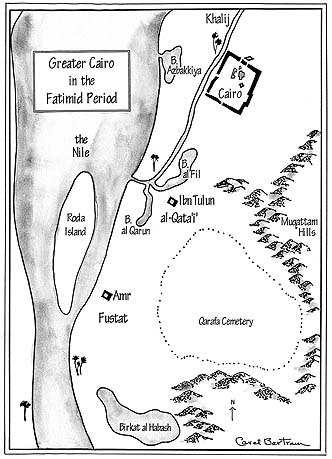

The Fatimid public text was a significant change from the traditional uses of officially sponsored writing, remarkable in its own time. I need, however, to clarify—even to circumscribe—the extent of the visual impact of those practices that constituted the public text within the built environment as a whole. The phenomenon of the Fatimid public text was geographically specific. It was a praxis observable only in the Fatimid Egyptian capital, a designation which in this study encompasses the area of the royal enclosure of Cairo (al-Qāhira) and the surrounding urban areas of Miṣr, a term used in the medieval texts to denote the urban areas south of Cairo (map 1). Yet even within this capital area, the public text did not function equally in all of the urban areas or at all times for all of the inhabitants. Rather, as the analysis of Fatimid practice will show, the public text was a dynamic phenomenon within the city.

Map 1. Greater Cairo in the Fatimid period (drawn by Carel Bertram)

Spatially, it involved changing relationships between various urban areas, distinguishing, for example, practices in Cairo from those in Miṣr. While all of the structures displaying this new use of writing were linked by the patronage of members of the Fatimid ruling group, their location and function varied, as did the presence of writing in specific areas on them. Similarly, the display or wearing of inscribed fabric in official ceremonial occasions was also limited to specific routes and structures, namely, those routes over which the Fatimid processions traveled. Thus only these areas were involved in displaying the public text on textiles.

Socio-politically, the public text was also a dynamic phenomenon in terms of group relationships and persons patronizing structures with writing on them and wearing inscribed garments. Wearing clothing with writing on it in public processions, displaying inscribed textiles, and patronizing Muslim communal structures with significant displays of writing defined, and was limited to, the members of the ruling group. The ruling group included the Caliph, his family, the wazīr, various dignitaries and heads of bureaus, poets and writers of the court, and the army.

Importantly, however, the composition of the ruling group changed substantially over time, as did the position of the individuals exercising power within it. Even the religious affiliations of members of the ruling group over the period of Fatimid rule changed, and toward the end of their rule in the twelfth century came to parallel more closely that of the population as a whole. Yet, the ruler-versus-ruled distinction remained stable and primary despite the fluid and variable inner dynamics of the ruling group.

Socially, the audiences for the various aspects of the public text also changed over time. While it was always true within the large urban setting of Cairo-Miṣr that the audience was mixed—different economic levels, different religious affiliations—the discussions in chapters 3 and 4 will make clear that in the initial periods of Fatimid rule some parts of the public text were aimed at Muslim audiences, excluding Christians. In contrast, in the later part of Fatimid rule, some equivalently placed texts in the public space addressed all members of the population, while others, namely, those in Fatimid sponsored sectarian spaces, addressed all Muslims.

How such writing related to the official sponsor obviously was equally dynamic. The astute beholder then, as today, could recognize that writing as a sign of power related to power in variously inflected ways. It explicated and dissimulated. The official sponsorship of writing at times indicated power where power existed. Equally clearly, the display of official writing could give the illusion of power to its sponsor where effective power no longer existed, or no longer existed in the same way. These aspects of writing will become clearer with the discussion of the later Fatimid practice which, although displaying the Caliph’s name, indexed not his power, but that of his wazīr.

To turn then to its media, the Fatimid public text was displayed mainly on buildings and on cloth. We face strikingly different problems in trying to reconstruct and study the public text on each of these. The problems imposed by the textile fragments are somewhat less familiar, and so the situation in which we find them warrants a more extensive explanation, and will be treated second.

Only a limited number of buildings built before 969/358 in Miṣr are extant, and only a limited number of the buildings subsequently sponsored by the Fatimids themselves are extant. In addition, the medieval written sources are not detailed enough to add significantly to our knowledge of the corpus of extant structures. Problems exist, for instance, in trying to reconstruct them in detail, especially sufficient detail for this study.[8] These are not new problems and my reliance on later medieval, fifteenth century, sources, like al-Maqrīzī, to reconstruct aspects of the Fatimid-built environment follows familiar traditions. Al-Maqrīzī was one of the few medieval writers who talked a lot about buildings. But even he did not comment in sufficient detail to help us greatly. Given these limitations, my reference to the Fatimid-built environment is based on the extant buildings of the Fatimid period within the area of Cairo-Miṣr: those in Cairo, those outside it in the vicinity of the mosque of Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn, and those in the surroundings of the Muqaṭṭam hills, plus the textual references where appropriate.

These buildings are important to us not simply because they are extant but because several of them figure in the official acts of the government which were aimed at a group audience. Others of the extant structures were passed (or nearly passed) in the procession. Many of the “missing” buildings were not focal points for official acts but, rather, were connecting links in the spatio-temporally extended rituals and ceremonies. What is a significant omission from the visible archaeological building record, and one not fully satisfied by mentions in the medieval chronicles, are the Fatimid Western and Eastern Palaces inside Cairo.[9] How or whether their facades differed visually from the neighboring mosques is something we simply do not know and cannot presently reconstruct.

On the other hand, cloth with writing on it remains from the Fatimid period in great quantities. The textile fragments with writing on them surviving from the Fatimid period number in the thousands. Most major museums throughout the world have some Fatimid cloth, usually labeled tirāz.[10] In spite of these extensive material remains, how what has survived functioned in Fatimid society is almost impossible to reconstruct.[11] We are hampered by a clear lack of correspondence between what we read in the medieval sources and what we see of the archaeological fragments. We are also hampered by the historical conditions of textile archaeology and the demands of the modern market place. These are factors seriously limiting the reconstruction of the many ways in which textiles with writing on them were made meaningful in Fatimid society, and the problem is serious enough to merit a more extended discussion here.

Except for one instance of a correspondence between an archaeological fragment and a textile use description in a medieval text,[12] inscribed cloth described as costumes for official processions, or hangings associated with them, cannot be identified among current archaeological textiles. For instance, among the hundreds of fragments I have examined in many collections, in many countries, not one displays a continuous quotation from the Qur’ān like that described by Ibn al-Ṭuwayr as flanking the mihrab in the mosque of al-Ḥākim during the Ramadan procession.[13] The luxurious silks mentioned in describing the attire of the Imām-Caliph have yet to appear—or if they have been dug up, they have not been identified. Not a fragment of the famous textile world map recorded by al-Maqrīzī in his account of the dispersal of Imām-Caliph al-Mustanṣir’s treasuries (1061–69/453–62) has been revealed. According to him, this textile-map displayed all locations and was fabricated in gold, silver, and colored silks, displaying at the lower end the name of the Imām-Caliph al-Mu‘izz and the date 354 (964 C.E.).[14]

Of course, some luxurious textiles have been found. They exist in the church treasuries and reliquaries in some museum holdings in Europe.[15] But except for certain individual textiles like the “veil of St. Anne,” [16] which is a complete loom length and which has been used in at least one manner we can identify, as a reliquary wrapping, the use of most of the other textiles represented now by their fragments is unclear. Even their final use is unclear, and that is in part the fault of the low esteem in which archaeology has held textiles until recently. Archaeological excavations have provided textiles primarily from burials and from refuse heaps. But the documentation of such textile findings in general has been poorly recorded.[17] Even in volumes like Kendrick’s Catalogue of the Textiles from the Burying-Grounds in Egypt, where the title suggests a final use for the textiles, we are not told whether the textiles were found on skeletons (whose age at burial or sex also go unmentioned) or in the grave with, not on, the body. We are not told whether the graves were Christian, Muslim, or Jewish.[18] Perhaps the fragments came from a refuse heap in the graveyard: we are not told. And sadly, many fragments come to us without the benefit of an archaeological context no matter how vague. In short, the researcher of Fatimid cloth is dealing generally with evidence of unknown provenance, and for which the provenance is now forever unknowable.

The demands of the marketplace and of collectors have further complicated reconstructing textiles and their use. Most textiles which come on the market were cut to preserve only their embellished parts (the parts with the silk, gold, and writing), and with that cutting much technical evidence that usually provides data about textiles was destroyed. In proportion to the total number of extant fragments, few have selvages and finishes. Without them it is not possible to know the width of the finished fabric, or even where the embellished section that is preserved was displayed on the total fabric. At least one of the full length pieces that remain, the “veil of St. Anne,” provides a base for understanding the design layout of relatively large fragments of similar design that are identified in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Textile Museum.[19]

All these caveats aside, much has been learned from the fragments of cloth with writing in Arabic on them. The range of messages and script styles has been described. Likewise, some studies have investigated the technology of gold thread, and others the range of colors and the source of fibres (linen, hemp, cotton, silk, and wool). But the factors described above do put serious limits on what can be learned from the textiles for this exploration.

The term “public text” also includes writing on coins because such writing was officially sponsored and it had a group audience by virtue of the sheer number of people who would have seen the writing. Obviously writing on coins is usually viewed in a more individualized manner than is either writing displayed on communal buildings, where many gather, or writing worn in official processions, where many watch. This difference accounts for the manner in which such writing is analyzed in this study. However, the fact that the writing on coins, officially sponsored writing, was a visual experience for a great number of people within and outside the territory of the issuing ruler brings that writing well within the focus of this study.[20] The Geniza records, for instance, provide ample evidence that writing on coins was meaningful for those engaged in money changing and transactions in the marketplace. Writing on coins was read for its semantic content, and the format of the writing (concentric circles or lines) was used for identification.[21]

“Official writing” and “public text” exclude from consideration non-officially sponsored writing with a group address, however much the writing practice might have been tolerated by officialdom. For example, these categories serve to exclude graffiti in Greek, Syriac, Latin, and Armenian left by pilgrims in the Sinai, which many reported seeing,[22] or in Arabic found on columns and other parts of structures at Jabal Says, Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Sharqi, and elsewhere.[23] In addition, they also exclude writing sponsored by the group leadership with a group address but not used officially in communal gathering spaces for the group, even though it played an elaborate role within the ruling class culture. Such writing on textiles and garments, as well as on a variety of luxury objects, was customary in the private practices among the ruling groups of most of the medieval societies of the eastern Mediterranean.

Greek-, then Latin-, and finally Arabic-speaking societies in the eastern Mediterranean, for example, all had finely blown glass vessels with writing on them. In each of these societies, and thus in each language and alphabet, some vessels displayed good wishes to the drinker, or beholder, or owner.[24] In addition, we know in detail that in Abbasid courtly society, handkerchiefs or headbands inscribed with verses of Arabic poetry were for a time the passion.[25] Even individuals not within the court seemed to participate in personalizing their clothing with writing.[26] All these uses of writing fueled fashionable taste and served individual interests, and it could be argued they served a limited group, but not in a manner to engender cohesion of the society as a whole by the reinforcement of beliefs and social relationships. In contrast to these uses, the writing on textiles and clothing that was part of the Fatimid public text was an officially orchestrated, systematic, group-addressed display of writing serving the interests of officialdom in the support of effective governance and, within its own terms, cohesion and stable social order.

In a more obvious way, several other kinds of writing also do not qualify as part of the public text. There is no public text in writing that constituted official government record keeping in which the audience addressed by the writing was not a group. Writing, of course, was an important part of official chancery practices of all ruling groups in the period. We know in detail that handwriting and the ability to compose in Arabic was an important factor in the choice of officials to staff Islamic government dīwāns (or bureaus). From al-Qalqashandī, we know in specific detail just how intensified these chancery practices became in the Fatimid period.[27] Nevertheless, official scribal practice, or its intensification, as in the Fatimid period, did not affect its audience. Chancery records were seen primarily by state functionaries or individual recipients of official missives, not a general audience.

This study of the functions of Fatimid public texts promotes a specific understanding of how officially sponsored writing (or any artifact or object or structure) makes its meaning. Meaning as understood here is not completely contained in the writing itself but, rather, grows in the web of contextual relationships woven between the official writing, the patrons, the range of beholders, and the established contexts in which that writing was placed. Take as a simple example what al-Ṭabarī tells us about one use of non-official writing in the early Muslim community. He says that ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb had the phrase “reserved for [or devoted to] the way of God,” [28] branded on the thighs of his horses. What we are told about the writing is its semantic content and its placement. But how it communicated meaning to the beholder, who those beholders were, we are not told.

To answer the question, “What did this writing mean?” and to specify what meaning to whom, we need to know about a variety of relationships: for example, were all horses (those belonging to Muslims and those not; those belonging to leaders and those not) branded? Were all brands phrases, and if so, what was their content? Were some brands idiosyncratic marks, and this the only phrase? Were other objects or animals marked with this phrase? What did the brand look like in itself and in relation to others? And finally, what was the significance of the locus of this branding? Without elaborating this example any further, what becomes clear is that to understand the specific meaning of that writing as a brand, we must explore, at least, the network of relations between ‘Umar, his brand and branding practices, the beholders, and the operant social usages that encompassed them.

Of course, officially sponsored writings and the public text are quite different from al-Ṭabarī’s story and ‘Umar’s brand. But the story is a useful tool here for exploring the various networks of relationships that made that use of writing meaningful to the beholders of ‘Umar’s horse. As such, it highlights for this study of officially sponsored writing, its content, its form, the reality of conditions of its being seen, and its beholders. This study suggests that these networks through which official writing communicated meaning to beholders had three primary dimensions: territorial, referential, and aesthetic. Each of these three dimensions, which could also be called functions, organizes many levels of relationships between official writing and the beholder, and social uses and practices.

Certainly, these three functions existed simultaneously. That is, the beholder of official writing derived meaning from each of these three sets of relationships at the same time, although each did not communicate meaning equally or in the same manner. At certain times, in certain historical circumstances, one of those functions of writing predominated. This text is not an attempt to say in words what the viewer saw. Rather, it builds from a fundamentally Gombrichian notion that writing relates to other writing and the reality of conditions in which these writings could be seen.[29] The major issues taken up in this text are understanding how the functions of the officially sponsored writing balanced one another, which one predominated to which group audience, and how those meanings changed within groups and between groups over time. Some preliminary discussion of these dimensions will clarify these networks of relationships.

The territorial function refers to the many ways in which officially sponsored writing reinforced and perpetuated to beholders both the solidarity of their group, binding it, and its exclusivity from other groups, bounding it from another or others.[30] By marking, and thus distinguishing for the beholder, one social territory from another, official writing signaled a boundary separating systems of different informational content. Officially sponsored writing as used by various societies or groups in the eastern Mediterranean communicated especially effectively through this dimension because the writing systems (of primary concern here, and to a lesser extent the languages) of many groups within this study were specific to that group. What is clear from the actions of various leaders of groups within the early medieval Mediterranean is that they recognized the effectiveness of writing as a sign of boundedness of a group, and consciously chose a writing system (what we might call simply an alphabet) because of its differences from, or similarities to, the alphabets of neighboring groups. This boundedness is not a startling revelation for us in the late twentieth century who have witnessed the break up of the Soviet Union, and the subsequent search for appropriate alphabets and languages to signal ethnic identities.

More to the point for this study, in the fifth century when the Armenian King Vramsapuh officially sanctioned the (current) Armenian alphabet created by Mestrop Mastoc’, he consciously supported the adoption of a writing system that resembled no neighboring one. The previous writing systems used by Armenians had been based on Greek and Syriac forms; the new alphabet was fashioned of glyphs that looked significantly different.[31] Thus from the fifth century on, the Armenian alphabet was a sign by which Armenians as a group were distinguishable from all other Christians in the area, especially the dominant group, the Greek Orthodox Christians, whose language, like the Armenian language, is Indo-European.[32]

Contrast this choice on the part of the Armenian community to adopt an alphabet emblematic of complete difference from other Christians with the actions of the Coptic community in adopting a modified Greek alphabet. They chose to represent their Hamitic language, Coptic, in alphabetic characters that were visually close (although not totally identical) to those of the Greek alphabet, the alphabet of the dominant religion, practiced by the rulers of the territory and by the majority of the people within their empire. The Coptic alphabetic glyphs emphasized similarity or identification by blurring alphabetic boundaries between the Coptic Christians and the Greek Orthodox, although some boundaries were maintained through the discernible differences in the letter forms.

Of course, the issue here is not simply the adoption of alphabets, but their social use. Patrons, understood here also as beholders, marked Armenian sectarian spaces with the Armenian alphabet; Coptic was displayed in Coptic churches. Samaritan and Hebrew appeared only in synagogues. The fact that writing during the period of this study was used to mark space as exclusive to a group was a praxis we recognize today by the very fact that we use the presence of a specific alphabet (and language) in the identification of those sectarian buildings which otherwise are archaeologically indistinguishable.[33] Thus, it is the presence of Armenian on a mosaic floor in Jerusalem[34] that enabled contemporary scholars to identify its specific group audience as Armenian Christian, when the rest of the depictions in the mosaic floor were relatively common in the geographic area.

Some languages—mainly Greek and to a much lesser extent Arabic and Aramaic—did not function in this territorial or bounding manner, or not in this manner during all periods of this study. The mere presence of these scripts and languages did not immediately mark the space as sectarian specific to the beholder. Greek, for instance, was displayed in synagogues as well as in Greek Orthodox churches.[35] But the beholder could understand “territorial dimensions” from its placement or, more exactly, the pattern of its placement in social practice. For example, mosques directly sponsored by Umayyad rulers from al-Walīd on displayed only writing in Arabic on the qibla wall, whereas other languages were sometimes displayed elsewhere.

The second dimension or function of officially sponsored writing we call the referential. This term refers to those networks of meanings derived from the evocational field of the writing; its “content” or informational base. This base included the oral and written traditions of the society, as well as traditions of social relationships, like the names and titles of honored people (past and present) within the group, and dates and events of group significance. Writing on the interiors of sectarian spaces, whether they were Muslim, Christian, or Jewish, was taken from group-specific evocational fields. As will be argued in chapter 2, the semantic content of the most visually dominant writing in all sectarian spaces came from socially equivalent texts: the Qur’ān, New Testament, and Hebrew Bible. Officially sponsored writing within these spaces also gave donor and patron information that helped to organize and stratify the group within itself.

Similarly, the Fatimid public texts placed inside Muslim sectarian spaces were directed to Muslim audiences in ways that are detailed in chapters 3 and 4. In contrast, however, those public texts, displayed on the outsides of structures and in processions, addressed a public audience. These texts came from more than one evocational field and spoke to more than one audience. Importantly, the semantic content was accessible to beholders who were not familiar with the Qur’ān, who were not Muslim. Thus the public aspects of the public text conveyed information germane to subserving the Fatimid social order on a larger scale than a sectarian or group-specific one in a mixed society.

Among the groups considered in this study, written texts that supplied beliefs essential to group action, affirmation, and cohesion were script and language specific. For Muslim believers, God’s revelation was and is in Arabic; for Jews, God revealed the Torah, oral and written, in Hebrew; to Christians, the New Testament came largely in translations. Thus for Muslims and Jews, regardless of specific intra-group differences, Arabic and Hebrew, respectively, were the languages of the essential communal evocational field (or information base) that bound the group together.[36] Among Christian groups, in contrast, the language and, importantly here, the script chosen for the translation of the New Testament (Greek, Armenian, Syriac, Coptic, etc.) became the script and language of the group’s belief-conveying evocational field. For Copts the New Testament of use was written in Coptic; for Armenians, in Armenian; for Latin rite Christians, in Latin.[37]

When the semantic content of the writing did not contain essential beliefs of the group, the writing did not (necessarily) function territorially to identify a sectarian group. Rather, the writing defined a group on a different scale, one bound by cultural traditions (written and oral) of a broader nature. Greek writing and language was for a time the primary example of this phenomenon because every time Greek was present in a sectarian space it did not necessarily convey content from the New Testament.

What enabled Greek script and language to be so widely appropriated by various sectarian groups were the social uses of the language in the eastern Mediterranean after Alexander. From the time of Alexander’s conquest of this area in the late fourth century B.C., a varied constituency of Greek-speaking people developed. Even under Roman occupation, when the official language was Latin, so many people spoke Greek that official inscriptions in many places were written in Greek.[38] Thus, in the fourth century C.E., when Greek became the official language of the Byzantine empire, not only were the new written messages transmitted in it, but Greek also bound together the already existing classical cultural traditions with those of the Christianity that had diverged from it.[39] It should not surprise us, there is no evidence of comment at the time, to find writing in Greek in synagogues as well as in Greek Orthodox churches. In fact, as recent research confirms, Greek was the language used in public texts in the eastern Mediterranean well into the late eighth century.[40] Of course, the referential and territorial dimensions the writing conveyed to the beholder in each of these sectarian spaces was different.

In the Greek Orthodox churches, the evocational fields of the writing displayed to the beholder were from both the written traditions conveying essential beliefs and from those social relationships that supply the names and titles of historic and contemporary people important to the group. In the synagogues, however, Greek was never used to communicate the essential beliefs.[41] These were expressed in Hebrew. But the writing that did appear in Greek, such as the names and titles of donors, and similar information, evoked a variety of group-based social relationships. The different evocational fields of the two scripts (and languages) stemmed directly from the fact that the congregation was Greek speaking, and knowledge of Greek language played a cultural role in the society on a broad scale.[42]

The third dimension of meaning of officially sponsored writing, the aesthetic, organizes all those networks of relationships that beholders brought to bear when they saw the form, material, rhythm, color (what might be called style)[43] of the officially sponsored writing. I am concerned here, for example, not only with the gold and glass mosaic medium in which the writing in the Dome of the Rock appeared, but wherever else writing appeared in that medium, and where it did not. The linkages or relationships of where writing appeared in this style, or did not appear in this style, communicated meaning to the beholder as did the shape and form of the writing of the letters. In fact, as I will argue in chapter 2, the meanings derived from the aesthetic dimensions of officially sponsored writing in the Dome of the Rock were the predominant ones for the beholders. What will become clear over the next three chapters is just how important the aesthetic function was in communicating meaning to the beholder. When writing could not be read—and even when it could—its color, materiality, and form were prominent aspects of communication. One brief example from the Fatimid period illustrates this.

Ibn al-Ṭuwayr tells us that when the Imām went to the mosque of al-Ḥākim (known as al-Anwar) during Ramadan, textiles near the mihrab were embellished with writing from the Qur’ān. He even lists the sūras.[44] Thus, since he indicated the semantic content of the writing, presumably he saw, read, and understood it. But in telling this story, he gave equally many—if not more—details about the color, materiality, and form of the writing. These factors thus must have been important in conveying meaning to him, and presumably to those to whom he recounted the information in his own time, and to us today.

Ibn al-Ṭuwayr noted that the writing of the sūras had diacritical marks. This undoubtedly was a clue to his audience and to us, that the script was not Kufic. In all probability it was one of the cursive scripts—the scripts with diacritical marks. Why would he have made that comment? What does it tell a reader? It tells us that the writing on the curtains paralleled the scripts which we know were used in many of the Qur’āns of the period. Conversely, it tells us equally clearly that the writing on the curtains contrasted sharply with the writing on the interior of the building in which it was displayed, (the Anwar mosque completed in the early eleventh century), and with the writing on and in the building sponsored by the Fatimids at about the same time that these curtains were displayed.[45] The writing in and on all of these structures was in Kufic, sometimes very elaborate Kufic.

But Ibn al-Ṭuwayr does not stop at that detail. He mentioned that the hangings were in silk. We know then that they were neither cotton, linen, nor wool. They were thus very costly, for the fabric was probably imported.[46] And, finally, he related their color—white. We know, and certainly his audience knew, that white was the official Fatimid color, as emblematic of their rule as the black (wool) was of their contemporaries, the Abbasids in Baghdad. Thus, from his comments (by placing what he described within the network of visual relationships and social practices for which we have evidence), we can begin to reconstruct the range of meanings that the official writing with diacritical marks displayed on white silk curtains had for Ibn al-Ṭuwayr and other contemporary beholders.

It seems appropriate at this point to inquire how this study of the Fatimid public text relates to scholarly inquiry in general and, in specific, to the study of writing in the disciplines that constitute Islamic Studies, for it is a part of both. The rubrics of analysis here are derived in part from elements of models of communication now almost three decades old.[47] Over the past years these categories have generated much scholarly debate, and scholars outside linguistic and literary studies in almost all social science and humanistic disciplines have attempted to digest, refine, rethink, and integrate this analytic paradigm.[48] This study of the Fatimid public text shares with such works an agreement that meaning involves the staging of specific relationships. But this study has a significant divergence from such a paradigm because it includes in its paradigm the sites or locations of meaning, a point of view that is absent from the narrower, linguistically oriented analysis.[49]Writing Signs includes the beholder, a group audience, as an essential element in its paradigm.

As such it takes inspiration directly from the pages of Ibn al-Ḥaytham’s (Alhazen’s) theory of perception written while he was in Cairo at the court of Imām-Caliph al-Ḥākim (r. 996–1021/386–411) and beyond, teaching at al-Azhar mosque until his death in c. 1039. He claimed that perception of a form required discernment, inference, recognition, comparison with other signs (amārāt), and judgment by users to relate them properly.[50] His insistence that for all practical purposes forms were perceived and not seen, pointed the way to understanding the active role of the beholder in placing a given form in a network of memorized forms and associations.

Including the audience in the analysis in Writing Signs gives historical dimension to the meaning of official writing. Without an anchor in viewer (user) and place, the reconstruction of the meaning of the writing (or any artifact) takes on an ahistorical timelessness. When I said above that meaning was not completely contained in the writing itself but was also a function of the relationship of the beholder, the writing and social usage and practices, I asserted that the meaning of a particular example of writing was situated in a beholder in a specific historical moment: it therefore changes over time and with groups of beholders. Thus, the “same” writing on the minarets of the mosque of al-Ḥākim will carry different meanings to a Muslim than to a Christian audience in the same year, for example, in 1002/393 when the writing first appeared. So, too, the “same” writing on costumes and textiles in Fatimid processions would have conveyed different meanings to spectators along the route in 1060 than in 1123. These divergent meanings for the beholders were the result of shifting political, economic, geographical, and religious attitudes or circumstances, as well as changes in the composition of the audience and beholder.[51]

In addition to concern about the beholder’s role in the construction of the meaning of written signs, this study understands writing practices in any society as subserving the hegemonic interests of officialdom, as defined by the given society. All societies with writing, then as well as now, have some mix of written and oral modes of communication. The uses of writing, whether extensive or limited, the modes and institutions through which writing is taught, and, in particular for the Fatimid emphasis here, the changes or shifts in the uses of writing within a society are all understood as socially constructed practices subserving the interests of those who institute the changes. That a society used writing to keep ledgers does not in itself supply sufficient reason for that same society eventually to put writing in or on buildings. Seeing writing practices as socially constructed, and fully understandable only in terms of the practices of a given society is supported increasingly by the research of psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and historians.[52]

These premises indicate that writing is approached in this study in ways unlike those used in most other works addressed to the understanding of writing in the Islamic world. Rather, Writing Signs is in the spirit of change called for by Michael Rogers,[53] and in the interests of contextual understanding of the role of writing advocated by Priscilla Soucek.[54] It has profited greatly from earlier studies, like those of Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, and Janine Sourdel-Thomine that have approached some of the issues included here.[55] But it is fundamentally different from (and presents historical evidence to question) approaches based explicitly or implicitly on an organic, evolutionary model by which inevitably, at least quasi-mechanically, the public text would emerge by natural processes.

There are many kinds of compendiums and articles based on this evolutionary assumption. These include almost all scholarly works based on style analysis that postulates simple styles as “early” and elaborate styles as “late” or “developed.” These compendiums have useful functions; such records form a base for this study. They do record difference, yet they understand difference as merely sequential and developmental, excluding the possibility that difference may simply mark contemporary variants caused by other production factors such as maker or use. In fact, beyond this explanation of change, most writers make no attempt to account for difference or change in any way. In other writings on writing, the organic metaphor is applied explicitly to the use of writing and the inevitability of its becoming more and more prominent not because of style but because it was launched on its trajectory by religion.[56] Yet, as a counter to this view it is useful to remember that the Qur’ānic revelation is not the only one given directly by God to men. The Torah is understood to be uncreated and revealed by God in oral and in written form. Nonetheless, the trajectories of the uses of writing both within and between each group of sectarian believers varies over time and place. These evolutionary models usually conflate book hands with writing on all other artifacts and buildings, thus implying that when handwriting attained a high degree of elaboration in Muslim societies, it finally had to appear somewhere beyond manuscripts and chancery documents and was therefore placed on buildings.

As this inquiry will elaborate later, neither of these evolutionary models can be historically substantiated. The general argument made conventionally is that change occurred in the use of officially sponsored writing from the time of the Umayyad Caliph ‘Abd al-Mālik (r. 685–705/65–86). In fact, in the Umayyad period, the uses of officially sponsored writing in Arabic in Muslim sectarian spaces appear more limited than those in Greek in Christian sectarian buildings during Byzantine rule. Moreover, the formats for the use of writing in Arabic had been established by early Muslim rulers; decade then followed decade with few changes. No exceptional or new use of officially sponsored writing addressed to a group appeared in the eastern Mediterranean. Fatimid Egyptian practice, the public text, then, was both distinct in its own time, and distinctly different from previous practice, even from Fatimid practice in North Africa and from that of their initial years in Egypt. The public text must not be seen as commonplace but, as my field observations suggest, as a unique, historically based occurrence not totally replicated elsewhere. We need only a cursory visual familiarity with the historical and geographical expanse of the practice of Muslim groups to know quite clearly that the official uses of writing were (and are) different, for example, in Safavid practice from those in Ottoman; in Ghana from those in the Philippines; in Detroit, Michigan from those in Pakistan.

One “evolution” or “development” that occurred in the eastern Mediterranean during the time of this study is supported by recent scholarly studies, namely, conversion to Islam. In the eastern Mediterranean, more people were Muslim at the end of the period of the study than at the beginning. More people were Muslim when the Fatimids ruled than when the Umayyads ruled. Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, by the time of the Fatimids, had a population that was dominantly Muslim, even if we adopt the late conversion date of 1010 C.E. argued for by Bulliet.[57] Even though significant Christian and Jewish minorities existed in Egypt, the population the Fatimids ruled was Muslim, and this study offers an understanding of how the public text was indeed related to the Muslim-ness of the society in the Fatimid capital. It seeks to highlight, in fact, that the specific composition of the Fatimid ruling group within the society, and that of the ruled population, and not simply its Muslim-ness, in part accounts for the presence and the meaning of the public text.

A language “development” is linked to conversion and Muslim rule: during the Fatimid period more people knew Arabic in Egypt than in the Umayyad period. “Knowing” Arabic involved several social considerations. On the one hand, knowing Arabic, in the sense of speaking the popular language, or al-‘āmmiya, was important, but to participate in the hierarchy of the society, command of reading, writing, and speaking proper or pure Arabic, fāṣīḥa, was mandatory. The hegemonic structures of the society, especially those representing the sciences of grammar and law, supported and fostered both what constituted fāṣīḥa and, its corollary, rendered judgments as to those who had sufficient skills to rise to positions of importance. No charge was more damning against a reputation for those in or seeking prominent positions than not knowing Arabic (fāṣīḥa). In the tenth/fourth century, and especially in the eleventh/fifth, the centuries of Fatimid rule, Cairo-Miṣr became a center for grammar and law, and Muslim students, especially from the western lands came there to study these sciences.[58] The size of the Fatimid government and record keeping in Arabic suggests the importance of knowing fāṣīḥa and the number of people who qualified at least for bureaucratic positions.

Evidence for Christians and Jews speaking and writing at least al-‘āmmiya is found in part in the nature of the anecdotes Abū Ṣāliḥ reports which indicate a significant level of spoken Arabic within the Christian communities.[59] The writing of the Geniza documents shows a familiarity with al-‘āmmiya among some Jews in Fatimid society, even though many of the documents were written in Hebrew characters. This practice of writing Arabic language in Hebrew characters is yet another example of alphabet and not language bounding and binding a group. And finally we have the presence of Coptic texts and vestments that display writing in Arabic in addition to that in Coptic, which suggests the commonalty of Arabic as a spoken language in Fatimid society, as well as some reading knowledge of it.[60]

Clearly, issues relevant to the Fatimid public text are not simply the speaking of Arabic, but both the recognition of Arabic writing as writing in Arabic letters, and the ability to read Arabic. Doubtless, Jews, Armenians, Copts, and other non-Muslims in Fatimid society, all of whom had a different group-specific alphabet and language, recognized or could identify Arabic writing when they saw it. Thus all beholders could understand many aspects of the territorial and aesthetic functions of official writing in Arabic by recognizing the presence of writing in Arabic. But for beholders to derive meaning from the referential functions of official writing, they needed to know its semantic content. Clearly, for beholders to understand the referential aspects of officially sponsored writing, they needed to be literate.

This study assumes that the minimal literacy sufficient to enable at least the relevant urban people to fulfill their duties to act appropriately is one which enables many beholders to read names and titles, dates, and other similar data.[61] My argument is closely related to Brian Stock’s hypothesis of a “textual community” where “texts emerged as a reference both for every day activities and for giving shape to the larger vehicles of explanation,” [62] for it includes both literate and illiterate beholders. But what I call “contextual” reading highlights the issues involved in beholders seeing the writing itself rather than simply knowing the text (either in oral or written fashion) and reacting to it.[63]

A contemporary ethnographic study by Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole[64] testing literacy in Arabic offers substantial evidence supporting my assumption that a significant number of people in Fatimid society would have had “contextual” literacy, and therefore could have understood the referential meanings from viewing the Fatimid public text. This assumption follows from the evidence gathered by Scribner and Cole that Muslim males, in receiving even a minimal mosque school education, learned enough Arabic for “contextual” literacy. In the Fatimid capital in Egypt, the urban population was predominantly Muslim. Thus, among the males at least, we assume contextual literacy through minimal participation in mosque schools. In addition to this male group within Fatimid society, we are told that Muslim women, probably only upper class Ismā‘īlī, were educated. And, as mentioned above, some members of the various Christian communities and of the Jewish community read Arabic.

A few more words need to be said about contextual literacy and the findings of the Scribner and Cole study to clarify their relevance here. Scribner and Cole tested contemporary literacy in Arabic in a Liberian society where three languages and scripts (Vai, the main language and script; Arabic, known only to Muslim members of the society; and English, currently being taught in the government schools) were learned in different institutions, and used for different purposes within the society by differing although overlapping audiences. In Liberian society, Muslims, except those who excelled in Muslim studies, received only the usual minimal mosque school training. (Those who excelled were sent to the main cities and the universities.) What these psychologists discovered, and what is important for this study, is that Muslims with only minimal training in Arabic, that is minimal introduction into the writing system and evocational base of that writing system, could read the “official” writing in Arabic in their society. Because of the way they learned Arabic, they also had a greater memory-store of learned texts, mainly from the Qur’ān. Although these Muslims’ knowledge of Arabic was not sufficient to read literature, or any range of “unexpected” material, nevertheless they could read all those materials in their society that were in Arabic, precisely because the material that appeared in Arabic writing in their society was expected. It came from a limited evocational base.

The critical element here is the range of expectation. In Vai society only very circumscribed material appears in Arabic. And Muslims within the society can read the range of Arabic that appears because the range of Arabic (the semantic content: the words) is expected. Literacy in Arabic does not extend beyond that ability. Chapters 3 and 4 of Writing Signs assume a “contextual” literacy and then detail the limited range, thus the “expectedness,” of the evocational base of the Fatimid public text. It is not that the semantic content of the public text never changed over the period of Fatimid rule, but, rather, within elements of the public text (parts of the processions, inside and outside mosques and shrines) the evocational base was relatively constant. It could be read(ily) read(ily).

One final aspect related to the reading of writing in Arabic needs to be mentioned. Most, although not all, of the writing in Arabic that made up the Fatimid public text was displayed in Kufic. Kufic is a script which is instantly recognizable by its geometrical lines. But it is highly incomplete phonetically: in this script diacritical marks are usually not added to letters, and thus twenty-eight differing consonantal sounds are represented by only seventeen different graphic shapes. The possible ambiguities of reading that can result from an alphabetically incomplete script have led many contemporary scholars to regard Kufic as inherently difficult to decipher. But as Geoffrey Sampson demonstrates, incomplete scripts can convey fully clear meanings to readers knowledgeable of the contents.[65] Beholders accustomed to seeing incomplete scripts conveying specific semantic content in familiar contexts can read the writing. It follows, then, that the writing in Arabic in Kufic script on Fatimid buildings could have been read by the contextually literate of Fatimid society for precisely the reason those same beholders could read the semantic content. The context made the content expected. Thus, only some words and phrases—a limited vocabulary—appeared in the Kufic of the public text.[66]

What was special about the Fatimid practice of publishing its public text was the systematic display: how the Fatimids used the texts they chose in the public space, how they were guided in their choice by their socio-political needs, and their acute sensitivity to the diversity of their constituency. The public text, the Fatimid’s special achievement, is best highlighted by observing the use of officially sponsored writing by others in the eastern Mediterranean.

Notes

1. I have used this phrase “public text” before, defined in a less circumscribed manner. See Irene A. Bierman, “The Art of the Public Text: Medieval Rule,” in World Art Themes of Unity in Diversity, Acts of the 26th International Congress of the History of Art, ed. Irving Lavin, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Penn State University Press, 1989), 2:283–91. I also used the term as part of a title for a session “Public Text and Style: Writing and Identity in the Islamic World” at the 1988 Annual College Art Association Meetings in Houston.

2. Writing, its uses and effects on society, is discussed by a number of scholars in a variety of disciplines. Some of the more general works that have informed this study are: M. T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record, 1066–1307 (London: Arnold, 1979); Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference, translated and with an introduction by Alan Bass (London: Routledge, Kegan Paul, 1978); Jack Goody, The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); Jack Goody, The Interface Between the Written and the Oral (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); Geoffrey Sampson, Writing Systems (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985); Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole, The Psychology of Literacy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1981); Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983); and Brian V. Street, Literacy in Theory and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

3. A recent article on aspects of the symbolic in Roman use of writing is, Calle Williamson, “Monuments of Bronze: Roman Legal Documents on Bronze Tablets,” Classical Antiquity 6, no. 1 (April 1987): 160–83. Susan Downey drew my attention to this article.

4. See chap. 2 for an elaboration of pre-public text practice.

5. Nāṣir-i Khusraw, Safar-nāma, edited and annotated by Muḥammad Dabir Siyaqi (Tehran: Zuvvar, 1956), 82.

6. See chap. 2.

7. Omitted here is consideration of muṣallas because they appear to have been minimally delineated spaces. Early ones have been found that are simply rows of stones like that adjoining the mosque at Jabal Says in southern Syria (Klaus Brish, “Das Omayyadische Schloss in Usais,” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo 19 (1963): 147–49) and two undated ones found next to camp sites in the Negev (G. Avni and S. Rosen, “Negev Emergency Survey—1983/1985,” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 4 (1985): 86–87). Judging from al-Maqrīzī’s lack of substantive descriptive comments about the muṣalla outside the Bāb al-Naṣr of Cairo, it, too, was simply a large delineated space.

8. At least one Fatimid structure is known through J. J. Marcel, Description de l’Egypte, état moderne, II, IIe part (Paris: n.p., 1822). See chap. 4.

9. Some of the interior walls from the Eastern Palace have recently been discovered. They were found under the direction of Nairi Hampikian who heads the restoration of the mausoleum and part of the madrasa of al-Ṣāliḥ Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb by the German Institute of Archaeology. Under a part of the madrasa demolished in late 1992 to make way for an entreprenurial complex, the Fatimid walls emerged. They are angled to the street in ways quite different from the walls of the overlaying Ayyūbid structure, suggesting a somewhat different street alignment than presently assumed. But the month long salvage archaeology permitted on the site will not add to our knowledge about the facade of the palace.

10. Most major museums have some Fatimid tirāz. The largest collections in North America are in The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Cleveland Art Museum, Cleveland; and the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. In Western Europe, the major collections are held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Benaki Museum, Athens. In the Middle East, the Islamic Museum in Cairo has the most extensive holdings.

The major catalogues or publications of the museum holdings are the following: Nancy Pence Britton, A Study of Some Early Islamic Textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1938); E(tienne) Combe, “Tissus Fatimides du Musée Benaki,” in Mélanges Maspero, 3 vols. (Cairo: L’Institut français d’archaéologie orientale, 1934), 1:259–72; Florence E. Day, “Dated Tiraz in the Collection of the University of Michigan,” Ars Islamica 4 (1937): 420–26; M. S. Dimand, in various of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin numbers, notes additions of tirāz to the MMA’s collections; Lisa Golombek and Veronica Gervers, “ Tiraz Fabrics in the Royal Ontario Museum,” in Studies of Textile History in Memory of Harold B. Burnham, ed. Veronica Gervers (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 1977), 82–126; A. F. Kendrick, Catalogue of the Textiles from the Burying-Grounds in Egypt, 3 vols. (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1924); A. F. Kendrick, Catalogue of Muḥammadan Textiles of the Medieval Period (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1924); Ernst Kuhnel, Islamische Stoffe (Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth, 1927); Ernst Kuhnel, with textile analysis by Louise Bellinger, Catalogue of Dated Tiraz Fabrics (Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum, 1952); and Carl Johan Lamm, “Dated or Datable Tiraz in Sweden,” Le Monde Oriental 32 (1938): 103.

11. Some of the implications of the state of the textile remains for the study of textiles have been discussed by Golombek and Gervers, “ Tiraz Fabrics,” 82–86, and their burial context has been shown in Jochen A. Sokoly, “Between Life and Death: The Funerary Context of Ṭirāz Textiles,” in Islamisch Textilkunst des Mittelalters: Aktuelle Problem (Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 1996): 71–76.

12. Bierman, “Art of the Public Text,” 283–90.

13. Al-Maqrīzī, Al-Khitat, 2 vols. (Cairo: Būlāq, 1853), 2:281.

14. Ibid. 1:147–48. The text mentions the fabric as Tustar, a fabric identified with the province of Khuzistan.

15. The “veil of St. Anne” is one such textile. Some fragments in museum holdings indicate by their lavishness that the original textile when it was whole must have been sumptuous.

16. This textile was first published in G. Marçais and G. Wiet, “Le voile de Sainte Anne d’Apt,” Académie des Inscriptions des Belles-Lettres, Fondation Eugène Piot, Monuments et Mémoires 34 (1934): 65–72. Most recently it was exhibited in London, 1976, and published by the Arts Council of Great Britain in the catalogue, The Arts of Islam (London: Westerham Press, Ltd. Council of Great Britain, 1976), 76.

17. Few excavations in the area of Egypt and the Sudan have been careful to record their textile findings in detail. A notable recent exception: Ingrid Bergman, Late Nubian Textiles, vol. 8 of The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (Stockholm: Esselte Studium, 1975). More usual is the publication of fragments, like that of the pile fragment with the writing on it specifically discussed by Alī Ibrahim Pasha in the Bulletin de l’Institut d’Egypte (1935), published with a photograph but no information about where in Fusṭāṭ (or even if in Fusṭāṭ) it was found.

18. We are tempted to make guesses of course about the sectarian identity of the persons buried in the graveyards, but we need to take care. By regulation, of course, Muslims and Jews should not be buried in clothing, and we are tempted thus to assume that the graves were Christian. But we know that the practice did not always follow regulation. For example, the Jewish man from the lower middle class, who provides for an “austere” funeral for himself. He directs his survivors to bury his body clothed in “two cloaks, three robes, a turban, new underpants and a new waist band.” S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, vol. 4, Daily Life (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1983), 160.

19. Several fragments of similar cloth exist in the collections of these museums. Interestingly, the layout remains roughly constant on all of the pieces, but the quality of the execution of the design varies as does the weight of the cloth and quality of the weaving. The Metropolitan Museum pieces are nos. 1974.113.14a, 1974.113.14b, 29.136.4, published in the Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 25 (1930): 129. Those in the Textile Museum are nos. 73.367, 73.228, 73.229, 73.79, 73.164. All of the fragments are either blue or green linen. I thank Marilyn Jenkins for introducing me to these textiles.

20. What is not considered here is official writing on weights. The inclusion of the writing on coins and exclusion of that on weights is basically a decision based on audience. What is assumed here is that many buyers in the markets experienced the effects of the use of weights, but only a limited group handled them, saw them and the writing on them. Other weights, like those used to set the weights of coins, had even more limited circulation.

21. Goitein, Mediterranean Society 1:236.

22. For Armenian, Georgian, and Latin inscriptions, see Michael E. Stone, ed., The Armenian Inscriptions from the Sinai (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982); for Greek and Nabatean, Avrahm Negev, The Inscriptions of the Wadi Haqqaq, Sinai (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, 1977); and C. W. Wilson and H. S. Palmer, Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai (Southampton: Ordnance Survey Office, 1869). Numerous other articles and books mention these inscriptions, many simply in passing; others like I. Svecenko, “The Early Period of the Sinai Monastery in the Light of Its Inscriptions,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 2 (1966), use inscriptions to recreate history.

23. For examples of these and graffiti at other locations see: Abū al-Faraj al-‘Ush, “Kitābāt ‘arabiyya ghayr mansūra fī Jabal Says,” Al-Abḥāth 17 (1964): 227–316; D. Baramki, “Al-nuqush al-‘arabiyya fī al-bādiya al-sūriyya,” Al-Abḥāth 17 (1964): 317–46; Janine Sourdel-Thomine, “Inscriptions et graffiti Arabes d’époque Umayyade à propos de quelques publications récentes,” Revue des Études Islamiques 32 (1964): 115–20; and the section on inscriptions in Arabic, in Oleg Grabar, R. Holod, J. Knustad, and W. Trousdale, City in the Desert, Qaṣr al-Ḥayr East, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978), 1:191–93.

24. Many examples of glass vessels with writing on them exist in most glass collections throughout the world. The range of quality of the glass is from very fine to rather coarse. Most of the writing on glass vessels, whether in Latin, Greek, or Arabic, is mold blown. Some is engraved. The types of messages range from good wishes to the names of artists (perhaps workshops) to the labeling of images. A few examples from the eastern Mediterranean will serve to indicate the range of the whole. Specific examples, rather than generic types, when given, refer to the collection at the Corning Museum, in Corning, New York.

Drinking vessels displaying good wishes in Greek, dated to the first centuries C.E., commonly display such sentiments as, “Be happy so long as you are here,” “Success to you,” “Rejoice and be Merry,” and “Cheers.” Similar messages appear in Arabic on glass vessels, although sometimes the format is more formal, as in the case of a small cup with Arabic dated to the eighth or ninth century (69.1.1), where the message is: “In the Name of God the Merciful, the Compassionate, Blessings on him who drinks from this cup which was made in Damascus under the supervision of Sunbat in the year 1.…”

Other vessels displayed scenes or figures which were identified by writing, such as the “gladiator bowls.” On others, writing identified biblical figures, or geographical sites represented on the vessel. Sometimes writing was used simply to label contents, like the glass vials made to contain Jerusalem earth and labeled as such.

25. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbihi and al-Washshā are two well known and frequently quoted authors who described the Baghdad and Samarra court passion for wearing and giving textiles with verses of poetry embroidered on them. Both sources quote several examples of the verses found on textiles, belts, hair decorations, and sashes of the people at court. This was a lyrical fashion for the literate to enjoy privately. Ibn ‘Abd Rabbihi, Al-‘Iqd al-Farīd, 7 vols. (Cairo: Būlāq, 1332H), 4:223–26; and al-Washsha, Kitāb al-Muwashshā, ed. R. E. Brunnow (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1886), 167–73. Chaps. 37–56 are especially full of short verses that appeared on the dress of court.

26. Muḥammad Abdel Azīz Marzouk, “The Turban of Samuel ibn Musa, The Earliest Dated Islamic Textile,” Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts, Cairo University 16 (December, 1954): 143–51.

27. Al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-a‘sha fī sinā‘at al-inshā’, 14 vols. (Cairo: al-Mu’assasah al-Miṣriyya, al-‘Āmma, 1964), 3:485–88.

28. Al-Tabari, Ta’rīkh, vol. 5 (Cairo: Matba‘at al-Istiqama, 1939), 2752–53. The Arabic phrase transliterated is “ḥabisūn fī sabīl Allah.” Michael Morony drew my attention to this mention of the use of writing.

29. I am paraphrasing here because Gombrich in his attack on essentialism was talking about markings or lines or form in painting. E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1956, Bollingen Series 35 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), 28–32; “On Physiognomic Perception,” in Meditations on a Hobby Horse and Other Essays on the Theory of Art (London: Phaidon Publishers, 1963), 45–56; and “Raphael’s Madonna della Sedia,” in Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance I (London: Phaidon Publishers, 1966), 64–80.

30. Boundary formation has been studied by a wide range of disciplines. See Fredrik Barth, ed., Ethnic Groups and Boundaries, The Social Organization of Difference (London: George Allen Unwin, 1969); Gregory Bateson, “The Logical Categories of Learning and Communication,” in Steps to an Ecology of the Mind (New York: Ballantine Books, 1972), 279–308; Heather Lechtman, “Style in Technology—Some Early Thoughts,” in Material Culture, Style, Organization, and Dynamics of Technology, ed. Heather Lechtman and Robert S. Merrill (Cambridge, Mass.: West Publishing, 1976), 3–20; and Margaret Conkey, “Boundedness in Art and Society,” in Symbolic and Structural Archaeology, ed. Ian Hodder (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 115–28.

31. A detailed history of the creation of the Armenian alphabet is A. G. Perizanyan, “Concerning the Origin of Armenian Writing” (in Russian), Peredneaziatskij sbornik II (Moscow: Izd-vo vostochnoi literatury, 1966), 103–33. A more abbreviated account of the history, but one which focuses on the morphology, is the two part series of articles by Serge N. Mouraviev, “Les caractères danieliens (identification et reconstruction)” and “Les caractères mesropiens (leur gènes reconstituée),” both in Revue des Études Arméniennes 14 (1980): 55–85, 87–111.

One can see in the historical circumstances and in the rationales for this alphabetic change direct parallels to those that led to the change by Ataturk from the Arabic alphabet and Ottoman language to the modified Latin alphabet and Turkish language. More contemporary examples abound. In the former Soviet Union Rumanian and Maldavian were distinguished by different alphabets although they were the “same” language. And, now, with the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Turkic-speaking republics are engaged in deciding the serious issue of which alphabet is the appropriate emblem of their new nations.

32. Of course, the new alphabet also distinguished Armenian from other neighboring Indo-European languages and writing systems: e.g., Pahlavi and Avestian, used primarily by non-Christians.

33. What is specifically referred to here is that the difference in beliefs, dogma, or ritual among the various Christian groups usually did not leave traces in the communal buildings of these groups. Churches usually can be distinguished from synagogues and mosques, but, for example, Armenian, Byzantine, and Syriac churches of this period are currently archaeologically indistinguishable, unless, of course, writing appears. See chap. 2.

34. See chap. 2.

35. While this issue will be taken up in chap. 2 in detail, Greek inscriptions in synagogues appear in areas where the community spoke Greek. In the coastal city of Caesarea, for example, the synagogue displayed three inscriptions in Greek: see Moses Schwabe, “The Synagogue of Caesarea and Its Inscriptions,” in Alexander Marx: Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1950), 433–49; E. L. Sukenik, “More about the Ancient Synagogue of Caesarea,” Bulletin Rabinowitz 2 (June 1951): 28–30. The synagogue in the coastal city of Apollonia has two inscriptions in Greek (and one in Samaritan): see Marilyn Joyce Segal Chiat, Handbook of Synagogue Architecture, Brown University Judaic Studies, no. 29 (Chico: Scholars Press, 1982), 166–67. In Ascalon there are two Greek inscriptions and one in Hebrew: see E. L. Sukenik, The Ancient Synagogue of el-Hammeh, 62–67. In Tiberias, one inscription in Greek: see E. L. Sukenik, Ancient Synagogues in Palestine and Greece (London: Oxford University Press, 1934), 7–21 and 52; and Chiat, Handbook of Synagogue Architecture, 95. For certain of these issues, the discussions in chaps. 2 and 4 of Walter J. Ong, S.J., The Presence of the Word (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1967) are especially relevant.

36. See Joseph Dan, “Midrash and the Dawn of Kabbalah,” in Midrash and Literature, ed. Geoffrey H. Hartman and Sanford Budick (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 127–39, for a provocative discussion of the trajectory of the role of writing among the Jews and reasons for the difference in contrast with medieval Christian practice.

37. Clearly, this reality conjoined elements of the referential and territorial functions of officially sponsored writing. Referential dimensions thus did, at times, have territorial functions.

38. C. B. Welles, “Inscriptions,” in Gerasa City of the Decapolis, ed. Carl H. Kraeling (New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1938), 355–493. This study is especially effective in demonstrating the longevity of Greek as the language of official use.