9. Mosque and Shrine in the Rural Landscape

Once the land is brought under cultivation, the produce of the land must be used for the expenses of the mosque as well as the needs of himself, his descendants, and his dependents. And he must assiduously pray for the survival of the powerful state.

| • | • | • |

The Mughal State and the Agrarian Order

From the reign of Akbar onward, the Mughals sought to integrate Indians into their political system at two levels. At the elite level they endeavored to absorb both Muslim and non-Muslim chieftains into the imperial service, thereby transforming potential state enemies into loyal servants. They also sought to expand the empire’s agrarian base, and hence its wealth, by transforming forest lands into arable fields and the semi-nomadic forest-dwelling peoples inhabiting those lands into settled farmers. “From the time of Shah Jahan [1627–58],” records an eighteenth-century revenue document,

An undated order by Shah Jahan’s successor, Aurangzeb (1658–1707), reveals a similar concern with increasing arable acreage, adding that should any peasant flee the land, the local revenue officers (‘āmil) “should ascertain the cause and work very hard to induce him to return to his former place.”[2] Such an appeal hardly suggests a state bargaining from a position of strength. In fact, it points to the chronic surplus of land over labor that obtained in premodern India generally, and in Bengal until as late as the mid nineteenth century.[3]it was customary that wood-cutters and plough-men used to accompany his troops, so that forests may be cleared and land cultivated.…Ploughs used to be donated by the government. Short-term pattas [documents stating revenue demand] were given, [and these] fixed government demand at the rate of 1 anna per bigha during the first year. Chaudhuris [intermediaries] were appointed to keep the ri‘aya [peasants] happy with their considerate behaviour and to populate the country. They were to ensure that the pattas were issued in accordance with Imperial orders and the pledged word was kept. There was a general order that whosoever cleared a forest and brought land under cultivation, such land would be his zamindari. Ploughs should also be given on behalf of the State. The price of these ploughs should be realised from the zamindars in two to three years. Each hal mir (i.e., one who has four or five ploughs) should be found out and given a dastar [sash or turban; i.e., mark of honor] so that he may clear the forests and bring land into cultivation. In the manner, the people and the ri‘aya would be attracted by good treatment to come from other regions and subas [provinces] to bring under cultivation wasteland and land under forests.[1]

If such extracts reflect policy, how was it implemented in Bengal? In the older, more settled parts of the province, meaning the western and northwestern sectors, Mughal officials collected the land tax from a predominantly Hindu peasantry at the usual, full rates, through the existing class of Kayasthas and other zamīndārs. In the relatively uncultivated forest and marshlands of the east and south, however, the government promoted the founding of new agrarian colonies focusing on individuals considered to possess local influence. The basis of this influence was most often religious, since the government sought to patronize persons attached to stable, and hence reliable, institutions. At local levels, the most typical building blocks of Mughal authority were mosques or shrines.

| • | • | • |

The Rural Mosque in Bengali History

As the focus of public prayer, the mosque has always been the principal public institution in Islamic civilization. Whether a grand edifice or a humble thatched hut, the mosque conceptually conflates Islam’s macrocommunity of the umma—the worldwide body of believers—into a microcommunity of fellow villagers or fellow city-dwellers, affording them the physical space to articulate their collective response to the word of God. As such the mosque is the physical embodiment of the social reality of Islam, and hence the paramount institution by which community identity and solidarity are expressed. This is especially true of the “Friday” or “congregational” mosque (jāmi‘ masjid), in which Muslims gather once a week for a sermon read by one of its functionaries. Such mosques—unlike personal, or private, mosques—were generally intended for the male Muslim population of settled communities and were constructed as soon as any local society had achieved a sufficient number of Muslims to warrant one.

As is seen in table 1 (see p. 67), a total of 188 dated mosques built in the course of six hundred years of Muslim rule in Bengal have survived into the present. Of these fully 117, or 62 percent of the total, were built in the relatively short span of a hundred years, from 1450 to 1550. Most are located in the western portion of the delta, especially near the old Muslim capitals of Gaur and Pandua; almost a third of the total are in the present-day Malda and Murshidabad districts. Conversely, eastern districts like Comilla, Rangpur, Khulna, Jessore, and Bakarganj have only a few mosques each, and Faridpur and Noakhali have none at all. There is thus a negative correlation between the location of dated mosques and the distribution of Muslims in the delta: surviving mosques predominate in western Bengal, whereas Muslim society came to predominate in the east. And whereas the vast majority of dated mosques appeared between 1450 and 1550, the first recorded evidence of substantial rural Muslim communities appears only from the very end of the sixteenth century. How, then, can we reconcile the contradiction between the appearance of these mosques, both in time and in space, and the appearance of a predominantly Muslim population?

The answer is that the mosques recorded in table 1 include only those bearing inscriptions. Endowed by men in command of considerable resources—rulers or other wealthy patrons—these were typically monumental structures built of durable materials like brick or stone, which explains why they have survived into the present. On the other hand,there were many more smaller and humbler mosques that have not physically survived into the present, and that were not endowed with dated inscription tablets. Built of ordinary bamboo and thatching, and patronized not by the court but by local gentry, hundreds of such mosques appeared in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially in eastern Bengal.[4] Since the appearance of these institutions correlates positively with that of majority Muslim communities, both in time and place, one may hypothesize that such humble mosques, and not the monumental works of art endowed by the wealthy, played the more decisive role in the Islamization of the countryside (see figs. 22, 23, 24).

Why and how were such institutions built? We have seen that in the empire generally, Mughal policy aimed at expanding the agrarian basis upon which the state’s wealth rested, and at creating loyal constituencies among local elites and their dependents. Although these aims were manifestly economic and political in nature, a characteristic means of achieving them, especially in frontier regions where new lands were being brought into cultivation, was by promoting the establishment of durable agrarian communities focused on religious institutions. Thus, in eastern Bengal, the state oversaw the establishment of both Hindu and Muslim institutions as new lands were opened up for cultivation. Of these, the Muslim institutions proved by far the more numerous and influential, and from them Islamic values, attitudes, terminology, and rituals gradually diffused over the countryside in the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Contemporary state documents mention, in passing, that at such institutions new Friday assemblies or circles of believers had been established (iqāmat-i ḥalqa-yi jum‘a).[5]

Such remarks take on special significance when it is recalled that throughout the delta the fundamental unit of social organization is not and never has been the mauẓa‘, or “village.” Nucleated settlement patterns such as are typical in North India never existed in the delta proper, even though the Mughals, and later the British, continued to use the term mauẓa‘ as though they did.[6] Rather, homesteads are strung out in lines along the banks of past or existing creeks. Or, more often, they are stippled throughout the rural countryside, dispersed in amorphous clusters. A pair of rural sociologists have described the East Bengali countryside as “one vast, seamless village. People build on high ground to avoid floods, and since high ground usually lies along slight ridges or hillocks, their houses are dispersed, with no clear demarcation between one village and the next.”[7] The geographers O. H. K. Spate and A. T. A. Learnmonth remark: “Over large areas there is no real ‘pattern’ at all, so homogeneous is the environment.”[8]

As the Bengali physical landscape was for the most part flat and homogeneous in all directions, so also the social order lacked natural nodes of authority. To be sure, kin groups (baṃśa, goṣṭhī) sharing common patrilineal descent are found in Bengali society. But these do not have the same cohesiveness or social significance as the endogamous barādarīs among Muslims of Upper India, much less the endogamous jātis of fully developed Hindu caste society.[9] In such a circumstance, especially where centralized political authority was weak, as in the hinterland of Mughal Bengal, maintaining social order could be a serious problem. “In lawless communities,” writes Eric Hobsbawm, “power is rarely scattered among an anarchy of competing units, but clusters round local strong-points. Its typical form is patronage, its typical holder the private magnate or boss with his body of retainers and dependents and the network of ‘influence’ which surrounds him and causes men to put themselves under his protection.”[10]

In Mughal Bengal, lacking tightly organized units such as nucleated villages or dominant clans through which authority might be exercised and social control maintained, local networks of patronage coalesced around locally defined centers of authority. The religious basis of these networks is noted by Ralph Nicholas:

The Muslim equivalent of the maṇḍalī, Nicholas continues, is called a millat (Arabic for “sect,” “party,” or “religious group”) or simply samāj, “society,” and is organized around a particular mullā, who may also be called a pīr by his followers.[11] In the southeastern delta the typical millat is composed of from eighty to four hundred members, who dine together during festivals, celebrate rites of passage together (circumcision, marriage, death), and pray together in times of community stress. The mullā who provides the group with religious leadership is maintained by a monthly payment from each family in the millat.[12]Social order is a serious problem in frontier society everywhere. The people of the lower delta are known to be tough and independent. They are famous for their skill with the lathi [“staff,” “cudgel”], which is often the only means of establishing a claim to a plot after a flood has changed the location of agricultural land. For centuries, in the lower delta, authority was poorly organized, centers of officialism were few and widely scattered. It seems likely that Islam and Vaisnavism functioned to provide authority in anarchic frontier society, and that they did so through loosely constituted religious organizations. The Vaisnava form of this organization is called a mandali (circle, congregation), it is organized around a particular guru, who may be called a gosvai by his followers, and is frequently constituted of persons of more than one village.

Similar structures of authority are found among rural Muslim communities in central and northern Bengal. In the central deltaic district of Pabna, the anthropologist John Thorp notes, a group whose members share mutual “feasting obligations” and who celebrate life-cycle rituals together is locally called a samāj, whereas a group that prays together in a single mosque is known as a jamā‘at. In practice, the jamā‘at may be coterminous with the samāj; alternatively, it may be composed of several samājes.[13] In any event, here as in the southeastern delta, it is the mosque and its socioreligious constituency, and not the “village” or the clan, that serves as the focus of identity and the effective vehicle for social mobilization. In neighboring Rajshahi District, two rural sociologists identified the jamā‘at, a community of some fifty to sixty scattered households drawn to the same rural mosque, as the closest analog of the North Indian nuclear village.[14] The same is true further north. “In many villages,” wrote Karunaketan Sen in a 1937 study of rural Dinajpur District, “there were huts which were places of worship and were called the ‘Jumma-ghars.’ Where there were more than one in a village, the local Muhammedan population was very often divided into factions, each attached to one of the Jumma-ghars.”[15] Whatever Sen may have meant here by a “village,” his remarks confirm that in rural Dinajpur, as in rural Rajshahi, Pabna, and Comilla, the mosque (masjid,jum‘a-ghar) was the effective unit of social organization among Muslims.

The continuing social significance of the mosque in today’s rural Bengali society is a legacy of a time when a religious gentry of ‘ulamā and pīrs—and in their institutionalized form, mosques and shrines—first emerged as nodes of authority around which new peasant communities originally coalesced, and in relation to which such communities were understood as “dependents” (vā bastagān). Such people were attracted to the religious gentry not only as devotees of a religious leader but as groups of client peasants who had formerly been local fishermen and shifting cultivators beyond the pale of Hindu society. Islamization in Bengal, then, was but one aspect of a general set of transformations associated with an expanding economic frontier, which took place most dramatically in the Mughal period. We may scrutinize these processes more closely by examining the exceptional Persian documentation that has survived in two districts on the eastern edge of the delta, Chittagong and Sylhet.[16]

| • | • | • |

The Growth of Mosques and Shrines in Rural Chittagong, 1666–1760

The estuary of the Karnafuli River, where the city of Chittagong is located, was settled at least as early as the thirteenth century.[17] Although briefly part of the independent sultanate of Bengal in the early fifteenth century, and sporadically in the sixteenth,[18] for most of the two centuries after 1459 the city and its hinterland were dominated by the kings of Arakan, a predominantly Buddhist coastal kingdom, whose capital was Myohaung, some 150 miles down the coast.[19] For long the city has been a window on the Indian Ocean; when under the control of the sultans, it served as a principal port for Muslim pilgrims and for the export of manufactured goods. From the mid sixteenth century on, Chittagong was inhabited by many Portuguese renegades, who, finding in it a haven beyond the reach of the Portuguese viceroy at Goa for their private commercial and military enterprises, effectively merged with Bengali society.[20]

Prior to the Mughal conquest in 1666, Chittagong’s hinterland remained agriculturally undeveloped—a dense, impenetrable jungle. In 1595 Abu’l-fazl described the city of Chittagong as “belted by woods.”[21] In 1621, wrote Mirza Nathan, Mughal troops proceeded through the present Chittagong District below the Karnafuli River along “a jungle route which was impassable even for an ant.”[22] And a contemporary chronicler of the 1665–66 Mughal expedition to Chittagong, Shihab al-Din Talish, recorded that before embarking on the expedition, Mughal commanders in Dhaka supplied their troops with thousands of axes, for the army had literally to hack its way through the dense jungle down the Chittagong coast from the Feni to the Karnafuli rivers, an area described by Shihab al-Din as an “utterly desolate wilderness.”[23]

The Chittagong interior was at that time inhabited by indigenous peoples described as having dark skin and little or no beard.[24] In other words, from the Mughal—that is, Turko-Iranian—racial perspective, they were distinctly alien. And their religion, wrote Abu’l-fazl, “is said to be different to that of the Hindus and Muhammadans. Sisters may marry their own twin brothers, and they refrain only from marriage between a son and his mother. The ascetics, who are their repositories of learning, they style Wali whose teaching they implicitly follow.”[25] Thus the Islamization of Chittagong did not occur among peoples who had already been integrated into a Hindu social order, but among indigenous peoples practicing cults that, from a Mughal perspective, were recognizably neither Hindu nor Muslim. Their marriage customs would constitute incest from either a Muslim or a Hindu perspective, suggesting little contact with either civilization. Their predisposition to follow holy men (walī) is significant, for, as we shall see, the earliest representatives of Islamic civilization in the Chittagong forests were pioneers locally understood as holy men.

The material culture of these people was based on jhūm, or shifting cultivation, as described by Francis Buchanan, a servant of the English East India Company who toured the region in 1798. The “Joom,” wrote Buchanan,

As lands under jhūm cultivation were not permanently cleared, this kind of cultivation did not require intensive labor. Nor could it produce quantities of grain sufficient to support dense populations. Here as elsewhere, the shift from jhūm to field agriculture, involving the adoption of the plow, draft animals, and rice-transplanting techniques, led to dramatic increases in population. All of these swiftly followed the Mughal conquest of 1666.is a species of cultivation peculiar, I believe, to the rude tribes inhabiting the hills east from Bengal. During the dry season, the natives of these places cut down to the root all the bushes growing on a hilly tract. After drying for some time the bush wood is set on fire, and by its means as much of the large timber as possible is destroyed. But if the trees are large, this part of the operation is seldom very successful. The whole surface of the ground is now covered with ashes, which soak in with the first rain, and serve as a manure. No sooner has the ground been softened by the first showers of the season than the cultivator begins to plant. To his girdle he fixes a small basket containing a promiscuous mixture of the seeds of all the different plants raised in Jooms. These plants are chiefly rice, cotton, Capricum, indigo, and different kinds of cucurbitaceous fruits. In one hand the cultivator then takes an iron pointed dibble with which he strikes the ground, making small holes at irregular distances, but in general about a foot from each other. Into each of these holes he with his other hand drops a few seeds taken from the Basket as chance directs, and leaves the further rearing of the crop to nature.…Next year the cultivator for his Joom selects another spot covered with wood, for in such a rude kind of cultivation the ashes are a manure necessary to render the soil productive. When the wood on the former tract has grown to a proper size, the cultivator again returns to it, and then there being no large trees standing, the operation of cutting down is easier, and the ground is more perfectly cleared.[26]

In 1665 the Mughal court ordered the governor of Bengal, Shaista Khan, to outfit an expeditionary force to seize Chittagong, from whose harbor Arakanese and Portuguese freebooters had been raiding and plundering the waterways of lower Bengal. Departing Dhaka in December 1665, a force of 6,500 under the command of Buzurg Umid Khan hacked its way though the jungly coastal corridor in January 1666, moving in tandem with a naval force of 288 war vessels. Reaching the port of Chittagong a month later, the Mughals subjected the Arakanese to a three-day siege, taking the citadel on January 26, 1666.[27] The city was at once made the headquarters of a new Mughal sarkār, or district, headed by a military commander (faujdār) in charge of administrative affairs and a chief revenue officer (‘āmil). A large number of Hindu immigrants also settled in the district at this time, some as traders, who came in the train of the invading army, and some as clerks, for the Mughals here as elsewhere relied heavily on Hindu bureaucratic expertise.[28] Most of the 6,500 troops in the expeditionary force remained garrisoned in the area to protect the frontier from land or sea invasion by the Arakanese. In return for their military service, these men were given small, rent-free patches of land, which they were at liberty to bring under cultivation. Later, when considerations of military security were no longer paramount, these lands were repossessed by the Chittagong government, and the troopers, or their descendants, became petty landholders, zamīndārs, charged with collection of the lands’ revenues.[29] These men did not themselves undertake clearing operations, however. Instead, they remained hereditary chieftains over territorially defined parcels of forest, authorizing more energetic souls to undertake the arduous task of organizing the clearing and cultivation of the land.

Soon after the Mughal conquest, mosques and shrines began proliferating throughout the Chittagong hinterland. In 1770 a British report found that fully two-thirds of the district’s best lands were “held by charity sunnuds” issued since 1666.[30] These documents, or sanads, had been issued in the name of the Mughal emperor by Chittagong’s chief revenue officer and were addressed to the petty clerks (mutasaddī) posted in the smallest units of revenue collection, the parganas. The documents attest to the systematic transfer of jungle territory from the royal domain to members of an emerging religious gentry who had built and/or managed hundreds of mosques or shrines (dargāh) dedicated to Muslim holy men. The documents were not called waqf grants—that is, lands denied to personal use and reserved for the support of religious Muslim institutions such as mosques, schools, hospitals, shrines, and so on. Rather, they granted tax-free lands directly to the trustees (mutawallī) of mosques or shrines and guaranteed that the grantee’s heirs would continue to enjoy such grants. Hence the grantees became the de facto and de jure landholders of territories alienated for the support of institutions under their administrative control.[31] The grants thus set in motion important social processes in this part of the delta: forest lands became rice fields, and indigenous inhabitants became rice-cultivating peasants, at once both the economic and the religious clients of a new gentry.

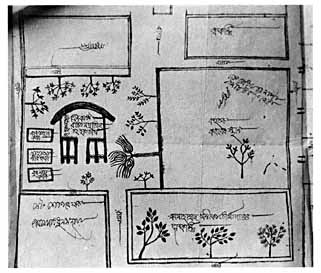

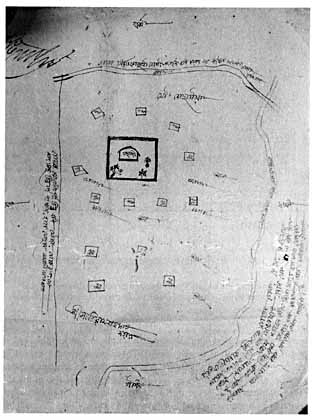

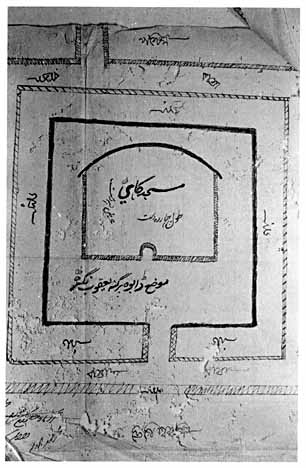

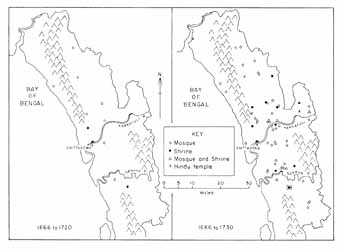

Between 1666 and 1760, a total of 288 known tax-free grants in jungle land were given to pioneers by Mughal authorities in Chittagong for the purpose of clearing forests and establishing permanent agricultural settlements.[32] These included grants to trustees of mosques, to trustees of the shrines (dargāhs) of Muslim holy men, to pious Muslims not attached to any such institution, to trustees of Hindu temples, and to Brahman communities (see table 6). Of the total, 262, or 91 percent, were given to Muslims, and of the total forested area transferred from royal to private domain, Muslims received 11,195.4 acres, or 87 percent. The single most important type of grant was that endowing a rural mosque, typically a humble structure of bamboo, straw thatch, and earth, of the types illustrated in figures 22–24.[33] The period in which the appearance of these village mosques became statistically significant was the 1720s, when fifty such structures appeared, scattered throughout the Chittagong hinterland.

| Mosques | Muslim Shrines | Muslim Charity | Hindu Temples or Brahman Communities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Acres | Number | Acres | Number | Acres | Number | Acres | |

| Note: The original sources give these figures in a land area unit called the dūn, of which there were two kinds. A mogī dūn was equal in area to 6.4 acres, whereas a shāhī dūn was four times as large as the former, equal in area to 25.6 acres. In either system, a dūn is made up of sixteen subunits called kānī. See J. B. Kindersley, Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operations in the District of Chittagong (Alipore: Bengal Government Press, 1938), 17. | ||||||||

| 1666–1699 | 1 | 166 | — | — | 2 | 262.6 | — | — |

| 1700–1709 | 2 | 38.4 | 1 | 89.6 | 1 | 16.6 | — | — |

| 1710–1719 | 4 | 288.3 | 1 | 256 | 9 | 517 | 1 | 209.6 |

| 1720–1729 | 50 | 1,583 | 11 | 391.8 | 11 | 111.6 | 3 | 392 |

| 1730–1739 | 30 | 1,118 | 14 | 281.6 | 5 | 82 | 3 | 78.4 |

| 1740–1749 | 31 | 1,606.4 | 16 | 386 | 11 | 237.2 | 5 | 139.6 |

| 1750–1760 | 32 | 3,120.5 | 20 | 428 | 10 | 214.8 | 14 | 817.6 |

| Total | 150 | 7,920.6 | 63 | 1,833 | 49 | 1,441.8 | 26 | 1,637.2 |

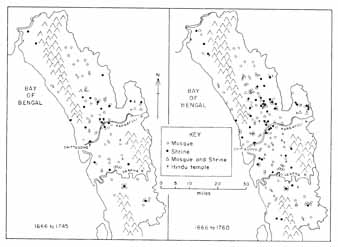

Map 6, which indicates the geographical distribution of these grants as of 1720, 1730, 1745, and 1760, shows how mosques and shrines, and to a lesser extent Hindu institutions, spread out from the Chittagong metropolis and onto the low-lying plains cradled by the ranges of hills north and south of the Karnafuli valley. They show the growth pattern not only of Islamic institutions but also of agrarian society, since the establishment of each institution involved the cutting and clearing of forest. Even the terms used in the sanads to identify the lands show how religious institutions spearheaded the eastward march of the economic frontier: whereas grants located near settled areas were often identified in terms of human geography,[34] those in the hinterland were identified in terms of natural geography.[35] Some sanads located grant areas with reference to other grants. Thus, a Sufi shrine of Hathazari Thana built in 1723 was supported with a grant of 25.6 acres of jungle located “east of the endowment [khairat] of Manik Daulat, north of the endowment of Muhammad Reza, and south of the endowment of ‘Abd al-Ghufur.”[36] The identification of grant areas in terms of other grants points to their relative density, and also to the absence of prior settlements in the Chittagong hinterland. Finally, it can be seen that by mapping the land in this way, the ‘āmil of Chittagong and his staff imposed a distinctively Mughal sense of space and social order on Bengal’s formerly forested landscape.[37]

Fig. 22. Lohagara, Satkania Thana, thatched mosque established in 1720, diagram dated 1843. “Kanun Daimer Nathi,” Chittagong District Collectorate Record Room, bundle 29, case no. 1808.

Fig. 23. Sundarpur, Fatikchhari Thana, thatched mosque established in 1759. “Kanun Daimer Nathi,” Chittagong District Collectorate Record Room, bundle 62, case no. 4005.

Fig. 24. Dabna, Hathazari Thana, thatched mosque established in 1766. “Kanun Daimer Nathi,” Chittagong District Collectorate Record Room, bundle 51, case no. 3329.

Map 6. Growth of the Muslim institutions in sarkār Chittagong, 1666–1760.

Map 6. (continued)

The social processes set in motion by these grants are seen in a sanad dated October 2, 1666, the earliest such document issued in Chittagong:

The economic aim of these grants, to expand the empire’s agrarian base, is evident from a phrase contained in nearly every sanad: “It is agreed that having brought the land into cultivation,” followed by a statement of the particular ways the recipient was expected to use the fruits of the land’s harvests.[39] The religious aim of grants for mosques and shrines was to promote Islamic piety in the countryside. In most cases this meant supporting simple, rural mosques and the petty functionaries and clerics who served them. For example, a 1721 sanad concerning the establishment of a mosque in Kadhurkhil, Boalkhali Thana, specified that in addition to expenses for carpets and lamps, the mosque’s tax-free lands were to be used to pay the reader of the sermon (khaṭīb), the prayer-leader (imām), the caller to prayer (mu’ażżin), pious men and preachers (muṣallīān), leaders in special prayers (fātiḥa ‘abdīn), and a sweeper (jārūb-kesh).[40] Other sanads made provisions for repairs (tarmīm) to the mosque, or mentioned special religious festivals earmarked for support, such as the major Muslim ‘Id holidays.[41] Still others supported Islamic ideals even when no institutional base was involved, as in the case of a grant of eight acres of jungle given in 1715 to Muhammad Munawwar and Shaikh Muhammad Ja‘far on condition that they read the Qur’an in Bakkhain, Patiya Thana.[42] Similarly, in 1748 Shaikh Imam Allah was granted 14.4 acres in Hulain, in the same thāna, for reading the Qur’an and performing prayers (fātiḥa).[43]Clerks [mutaṣaddī], assessors [mu‘āmil] past and present, headmen [chaudhurī], accountants [qānūngō], and peasants [ra‘āyā, muzāri‘] of the revenue circles [pargana] of Sarkar Islamabad [i.e., Chittagong], know that:

Shah Zain al-‘Abidin has made it known that he has many dependents and has built a mosque, where a great many faqīrs and inhabitants come and go. But, as he has no means of maintaining the mosque, he is hopeful that the Government will bestow some land on him.

Having investigated the matter, the revenue department has fixed the sum of six shāhī dūn and eight kānī [i.e., 166.4 acres] of jungle land, lying outside the revenue rolls, and located in villages Nayapara and others of pargana Havili Chittagong, as a charity for the expenses of the mosque as well as a charity for the person mentioned above. Once the land is brought under cultivation, the produce of the land must be used for the expenses of the mosque as well as the needs of himself, his descendants, and his dependents. And he must assiduously pray for the survival of the powerful state. He and his descendants are not required to pay any land revenue or non-land revenue, highway taxes, bridge taxes, special cesses, or any other assessments issuing from either the administrative or the revenue branches of government. Nor is he bound to seek a fresh sanad each year. Take great care to execute this order. Dated 2 Rabi I 1077.[38]

Politically, the grants aimed at deepening the roots of Mughal authority on the frontier. The condition that the grantee “must assiduously pray for the survival of the powerful state,” as in the 1666 sanad cited above, established a direct link between the government and the grantee, inaddition to an indirect link between the government and God. Not one document failed to mention this condition of government patronage. Less apparent, though no less important, was the state’s interest in securing the loyalty of those persons described as the grantee’s dependents (vā bastigān). These were people who, having assisted the grantee in clearing the forests and building the institution, continued to serve it by cultivating the lands attached to it, and were therefore its clients. Some documents explicitly stated that the purpose of the grant was to support the followers of this or that holy man, as in a 1725 grant to Taj al-Din and Zia al-Din, who received a patch of jungle in Hathazari Thana in order that its produce might support their children and “dependents.”[44] In 1745 three men—Mir Sa‘id Allah, Ghulam Husain, and Afzal Khalifa—declared that they had many dependents whom they could not support. For the maintenance of these persons, the state granted them 30.4 acres in the same thāna.[45] Other grants stated that after the expenses of maintaining the mosques or shrines had been met, the balance of the land’s produce should go to support the grantee’s dependents.[46] In sum, the government recognized mosques and shrines as the foci of sociopolitical activity on the frontier and sought to form them into a dependent clientele, just as those institutions had already formed dependent clienteles of their own.

| • | • | • |

The Rise of Chittagong’s Religious Gentry

By supporting frontier mosques and shrines, Mughal authorities in Chittagong established ties with political systems that functioned at a very local level. This was logical, for it was on the frontier itself, and not in district offices in Chittagong city, far less at the provincial or imperial levels, that the manpower and organization requisite for the arduous task of clearing the thickly wooded interior were to be found. The government did no more than legitimate and support an enterprise whose initiative was located at the grass roots. A 1798 survey, undertaken several decades after the English East India Company had occupied Bengal, is suggestive of how the Chittagong hinterland was reduced to the plow in Mughal times. “The following process for clearing new land is that here adopted by the Bengalese,” wrote Francis Buchanan:

It is clear, first, that the initiative for clearing the land lay with local men of enterprise, and not with the government. Second, we see the role played by cash money advanced to laborers by the zamīndār, or primary landholder. And third, we find the equally important role played by “some local man of some consequence,” who, having acquired a grant of uncleared land, apportioned it among laborers, who in turn became shareholders beneath him.A man of some consequence, a diwan, a phausdar [faujdār], or the like, gets a grant of some uncleared district. Different persons, who have a little stock, apply to him for pottahs [pāṭṭā] or leases, of certain portions, and in clearing their portions these men are often assisted by the Zemeendar, or possessor of the original grant, with a little money, as a temporary support. But this money becomes a debt which they are obliged to repay when they are able.

In the cold season the operation commences by cutting down the bushes and smaller trees. After drying a few days these are burned and at the commencement of the rains the ground is ploughed, as well as the strength of the cattle and the resistance of the roots will admit. Rice is then sown, and a small crop is produced. The sirdar [sardār] or overseer, and three labourers, are supposed to be able to perform this operation with eight kanays [i.e., 3.2 acres] of ground. The second year’s operation consists in cutting down the greater part of the large trees, in burning them, and digging out the roots of the bushes and underwood, from the remains of which, after the first year’s ploughing, many shoots have then formed. The ground is again sown at the beginning of the rains, and yields a better crop. One sirdar and two labourers are reckoned equal to the performance of this work, on eight kanays [kānī].

In the third year the operation is concluded by again cutting down such brushwood as may have shot up, and by digging out and burning all the roots of the large trees that have been felled. The same number of persons are employed as in the second year. The ground in the fourth year is reckoned perfectly clear, and pays the usual rent. For the first three years nothing is exacted. Two men and two bullocks are reckoned equal to the cultivation of eight kanays, which here are the usual extent of one grist’s possession. All over Chittagong the cow is employed with the plough as well as the bullock.[47]

If we apply to data from the early eighteenth century the same mechanisms that Buchanan described at the end of that century, the categories used in Mughal sanads become readily intelligible. The “local man of some consequence” mentioned by Buchanan in 1798 corresponds to the man named in the Mughal sanads who organized local labor into work gangs to clear the forest and commence cultivation. The documents do not identify where these “men of consequence” came from, though the titles that occasionally accompany their proper names provide clues to their social origins. These included, in order of frequency, shaikh (23), chaudhurī (11), khwāndkār (9), ḥājī (8), ta‘alluqdār (7), shāh (4), faqīr (4), saiyid (3), darvīsh (3), and khān (3). The twenty-one men identified as chaudhurī, ta‘alluqdār, and khān were evidently members of the rural landholding aristocracy before they acquired these grants, and in all likelihood they built or supported mosques or shrines as a means of obtaining tax-free rights to their lands. The rest were associated with either formal or informal Islam. The largest category, “shaikh,” could have referred either to informal holy men or to members of the ‘ulamā. Those styled khwāndkār, a Persian term meaning generally “one who reads,” were originally associated with public Qur’an reading. ḥājīs were men who had performed the pilgrimage to Mecca, and saiyids were those claiming genealogical descent from the Prophet Muhammad. The remainder of the titles—shāh, faqīr, and darvīsh—all refer to pīrs, or holy men.

Whatever their origins, these men played central roles in transforming the jungle to paddy, in introducing Mughal and Islamic culture into the forests, and in integrating forest communities into that culture. They were also entrepreneurs, arranging on the one hand to get necessary authorization from a local zamīndār to clear the forest, while on the other hand arranging with local laborers to work the land as shareholders. These latter persons, who in Buchanan’s account were lease-holding cultivators, correspond to the “dependents” (vā bastigān) named in the Mughal sanads. And finally, at the top of the local structure, both Buchanan’s account and the Persian documents mention the zamīndār, or the primary landholder from whom the organizer of field operations acquired the right to commence clearing.

From Buchanan’s account it appears that by 1798 the Islamization and peasantization of the native peoples of Chittagong’s uplands had made little progress, for he describes the tribal peoples of the Sitakund mountains in northern Chittagong as still practicing shifting, or jhūm, cultivation, growing cotton, dry rice, ginger, “and several other plants which they sell to the Bengalese in return for salt, fish, earthen ware, and iron.”[48] He also noted among these peoples some worship of śiva.[49] Nor had Mughal or European notions of property rights yet extended to these still-forested lands. “The woods,” Buchanan wrote, “are not considered as property; for every ryot [cultivator] may go into them and cut whatever timber he wants.”[50] We may contrast this attitude with the keen sense of proprietorship among Mughal grantees. In 1734, for example, the servants of the shrine of a certain Shah Pir received over sixty acres of jungle in Satkania Thana in order to maintain the shrine and meet the expenses of travelers. Some time later, the shrine’s trustee [mutawallī] filed a complaint in the court of the local qāẓī alleging that a certain Tej Singh had unlawfully established a market on the lands belonging to the shrine and insisting that the market be removed.[51] To the Mughals, settling the frontier entailed the establishment of legally defined notions of property backed by state power.

If the agrarian frontier had not yet reached the Chittagong highlands by the end of the eighteenth century, in the low country Buchanan noted that natural forest lands had recently been replaced by cultivated fields. “The stumps of trees still remaining on several of those [valleys] which I today passed,” he wrote referring to southern Satkania Thana, “show how lately they have been cleared.” Or again, referring to northern Chakaria Thana: “It is only 13 or 14 years since the upper part of this valley began to be cultivated. New land is still taking in, and the stumps of trees remain everywhere in the fields.”[52] The domain of field agriculture ended only in the extreme south, for he remarked that “the whole country to the south [of the Ramu River] is an immense forest, utterly impenetrable without the assistance of a hatchet.”[53]

Buchanan also observed “that most of the new cultivated lands belong to Hindoos, who by acting as officers about the Courts of the Judges and collectors, and by possessing greater…economy than the Mohammedans, are very fast rooting these out. The great body of the people, however, in the province of Chittagong, is still composed of the Mohammedan persuasion.”[54] The latter observation was later confirmed in the earliest (1872) census, which showed Muslims comprising 78.2 percent of Satkania Thana and 78 percent of Cox’s Bazar Subdivision, in which both Chakaria and Ramu Thanas are located.[55] As to Buchanan’s remarks about Hindus, in Chittagong as in Dhaka and Bakarganj, the apex of the social hierarchy was dominated by absentee Hindu zamīndārs. Although these played a key role in the task of land reclamation, their lines of patronage did not lie with the cultivators below, but with the ruling class above—those in “the Courts of the Judges and collectors.”[56] Once having acquired their zamīndārī rights, these men adopted the ritual style of kings vis-à-vis their agricultural tenants, for Buchanan went on to add, referring to Bengal generally, that “every Hindoo Zemeendar of the least note is called a Rajah, and every such person by his ryots and servants is commonly called Maha-raj, or the Great Prince.…As a zemeendar the Rajah is amenable to our courts, but within his own country he is absolute, and possesses the uncontrolled power of life and death.”[57]

In sum, the structure of land tenure as described in 1798 consisted of three tiers beneath Chittagong’s chief revenue officer. At the apex was the zamīndār, aloof from the actual process of forest clearing or field agriculture, typically Hindu, and given to the ceremonial style of a petty raja. Next was Buchanan’s “local man of some consequence,” the pivotal figure who secured from the zamīndār a grant to clear jungle land and hired laborers to accomplish the task. This would be either a member of the religious gentry itself or a petty landholder who supported a religious institution to obtain tax-free status. Typically enterprising entrepreneurs, and usually Muslim, these were the men who mobilized local manpower and oversaw clearing operations. Finally, there was the mass of laborers, who after four years of clearing forest lands were ready to begin regular field agriculture. It is significant that Buchanan describes the inhabitants of the uncleared jungle as non-Muslim tribal peoples who practiced some form of śiva worship, whereas the cultivators of lands already cleared he describes as Muslims. This suggests that peasantization and Islamization proceeded hand in hand among the peoples of Chittagong’s arable low country.

There were three discernible means by which the religious gentry acquired their land rights: donation, purchase, and pioneering. The first method corresponds to what Buchanan found at the end of the eighteenth century, when men produced documents showing that some legitimate local authority had donated land to them. Described in Mughal documents as sardār (chieftain), chaudhurī (headman), or most frequently zamīndār (landholder), the Muslims among these authorities were most likely descendants of the Mughal troopers who had accompanied Buzurg Umid Khan’s expedition to Chittagong in 1666. The Hindus among them were probably descendants of the clerks or revenue agents who had also accompanied that expedition and, in a manner described by Buchanan for the late eighteenth century, used their proximity to the governing authorities to get new lands made over to them in their own names. By authorizing a petitioner to clear the jungle and build a mosque or shrine, these local authorities became patrons of the petitioners named in the sanads. It is also evident that by the mid eighteenth century the patronage system had not hardened along communal lines: some Hindu chaudhurīs patronized mosques and some Muslim chaudhurīs patronized temples. As early as 1705, at the close of Aurangzeb’s long and turbulent reign, Thakur Chand, a Hindu chaudhurī in Fatikchari Thana, donated 17.5 acres of jungle land for the construction and support of a village mosque built by a local qāẓī.[58] In 1740 Manohar and Jagdish, two Hindu chaudhurīs in Rauzan Thana, donated 76.8 acres to Shikur Muhammad Pahlawan to cover the expenses of a mosque the latter had built in the forest.[59] Conversely, in 1740 Mir Ibrahim, a Muslim chaudhurī in Rangunia Thana, donated 3.2 acres to a certain Mukundaram in the way of a devottar, a tax-free land grant for the support of a temple or image.

Acquisition by donation generally involved a Muslim pioneer with a religious title like “shaikh” going into the jungle and, having secured a document of authorization from a local chieftain, building a mosque or shrine with local labor. The document attested that the chieftain had donated a certain portion of undeveloped jungle land to the shaikh. The latter would then produce this document to local Mughal authorities in a formal request for legal recognition of tenurial rights over jungle lands that he either proposed to bring under cultivation in order to support those institutions, or that he had already brought under cultivation. After investigating to verify the petitioner’s claim, the Chittagong revenue authorities would issue a sanad in the name of the chief revenue officer of Chittagong sarkār and bearing the seal of the reigning Mughal emperor, thereby extending government recognition of the petitioner’s trusteeship (tauliyat) of the institution and the lands supporting it. In this process the petitioner moved from de facto to de jure landholdership, enjoying the rights to the produce of the land subject to his support of the institution specified in the sanad.[60] Actually, chieftains who in this way donated portions of their jungle territory to such shaikhs were adhering to an ancient model of Indian patronage. In Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu contexts laymen had gained religious merit by donating lands to monastic or Brahmanic establishments, a practice that served to reinforce the cultural bonds between donating clients and receiving patrons.[61]

Some members of the religious gentry acquired their tenure by purchasing undeveloped forest from the chieftains or headmen who were its legally recognized holders. In such instances, the transfer of land did not reinforce cultural ties between donors and receivers according to classical models of Indian patronage. On the contrary, the use of cash enabled people to bypass traditional modes of patronage and deal with groups of people of different cultures. For example, in 1725 Shaikh ‘Abd al-Wahhab of pargana Panchkhain in Rauzan Thana purchased 16.4 acres of untaxed and undeveloped jungle land from the pargana headman, Jagdish Chaudhuri, a Hindu. The new owner then donated the land to Muhammad Khan, whose father had built a mosque on it.[62] Here both donation and purchase were operating, as a Hindu landholder had sold jungle land to a Muslim intermediary patron, who in turn donated it to the builder of the mosque. There are also numerous instances of chaudhurīs selling jungle land directly to the trustees of mosques or shrines. In 1748 Shaikh Muhammad Akbar and Muhammad ‘Abbas notified Mughal authorities that they had purchased 38.4 acres from the headmen (chaudhurīs and ta‘alluqdārs) of their locality and had built a mosque there. As more land was necessary to meet the expenses of maintaining the mosque, however, they requested additional jungle land for clearing, preparatory to cultivation, and they were given 19.2 acres for this purpose.[63] Ten years later, Muhammad Sardar of Fotika, Hathazari Thana, notified the Mughal authorities that he had purchased 16 acres of land from the headmen (chaudhurīs) and landholders (zamīndārs) of his pargana in order to support a preacher and prayer-leader, and to meet the expense of celebrating the ‘Id festivals of a mosque and the commemorative festivals (‘urs) for a saint buried in a shrine there. He now wanted government recognition of the tax-free status of these lands.[64]

Such cases suggest how a cash-based economy facilitated the movement of men and resources in the forest, the clearing of land, and the expansion of mosque-centered settlements in formerly forested areas. Silver had, of course, been in widespread circulation as currency in Bengal ever since the Turks had established their rule in the thirteenth century. Already in the late sixteenth century, the poet Mukundaram had linked mobile cash with the process of forest clearing and agricultural operations.[65] In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, both European and Asian merchant-investors greatly expanded the volume of money circulating in Bengal, making possible transactions such as the case cited above in which a Hindu chaudhurī sold forest land to Muslims for development. Moreover, the monetization of Bengali society allowed people to attach new meanings to land. What had formerly been a ritual item, appropriate for acquiring religious merit in the context of Buddhist or Brahmanical gifting (dāna), had now become a freely transferable commodity.

The third and most common mode of land acquisition among the grantees was that of men and their dependents clearing the jungle in territories apparently unclaimed by superior zamīndārs. In these cases, land was acquired neither by donation nor by purchase, but by primary settlement by pioneers who claimed, and whose descendants would also claim, a tax-free tenure called jangal-burī maurūthī, or “jungle-cutting inheritance.” Thus we read of a certain Muhammad Sadiq, son of Shaikh Mumin, who informed the Mughal authorities in 1722 that he and his dependents had cleared 57.6 acres of jungle in what is now Rauzan Thana, where they had built a mosque. Noting that the land he held was “occupied by established custom,” Sadiq claimed tenurial rights of jangal-burī maurūthī. Now he requested Mughal confirmation of his claim so that he would be able to support his dependents.[66] In the absence of any superior landholder, Sadiq himself became the de facto zamīndār of this territory.

If the political identity of these pioneers was based on their integration with the Mughal state through ties specified in the grants, their religious identities rested on different footings. Some were local holy men popularly redefined as Muslim holy men, some were Muslim holy men further redefined as Sufis, and still others were popularly accorded a Middle Eastern origin. Some seem to have been the very sort of indigenous Bengali walīs that the native population of the Chittagong hinterland had revered from pre-Muslim times, as noted by Abu’l-fazl.[67] For example, in 1723 and 1733, 25.6 acres of jungle were given to the dependents and local shrine of a “dervish” named Kali Shah, whose name associates him with the goddess Kali.[68] The same is true of a certain Shaikh Kali, who built a mosque in Rauzan Thana in 1760.[69] In 1725 a shrine appeared in Charandip, Boalkhali Thana, in honor of a certain Jangal Pir, whose name identifies him as a holy man of the forest.[70] In such cases, local walīs or saints of the Chittagong forest became integrated into the Mughal religio-political system as petty clients at the bottom of a vast patronage network extending clear to the emperor’s palace in Delhi. Yet their affiliation with mosques and shrines also cast them in the role of representatives of Islamic civilization.

In short, the tendency of Chittagong’s forest-dwelling peoples to follow the teachings of charismatic holy men allowed an outsider to be situated in this category and to find acceptance among the populace as one of their own. Later, the charismatic authority of such foreign holy men became routinized when they or their descendants merged with the revenue bureaucracy as petty landholders, as had happened to the sons of Pir ‘Umar Shah, who became the zamīndārs of the area in Noakhali cleared by their holy man father. The very first grant in the Chittagong collection of sanads illustrates the process. In 1666 Shah Muhammad Barbak Maghribi, whose name associates the saint with northwest Africa, settled in the forests of Chittagong, where he and his followers built a mosque and cleared the 166.4 acres of jungle given by the Mughals for its support. A century later, the descendants of his followers claimed revenue-free rights to the lands on the grounds that they were descended from the original jungle-clearers and thus held a legally recognized form of inheritance (jangal-burī maurūthī).[71] In another instance, in 1717 a Sufi named Shah Lutf Allah Khondkar had been given 108.8 acres in Satkania Thana as personal charity (madad-i ma‘āsh). By 1740 the village founded by him had acquired the name “Mun‘imabad,” or “the benefactor’s cultivated area,” and the descendants of the Sufi’s followers claimed rights to the land on the grounds that their ancestors had originally cleared the jungle.[72] Thus, too, in 1726 a local preacher (khaṭīb) named ‘Abd al-Wahhab Khondkar built a brick mosque in Patiya Thana, and just over a decade later his grandson, ‘Inayat Muhammad, emerged not only as the heir to the lands attached to the mosque but also as the region’s chaudhurī.[73] Such developments illustrate Max Weber’s notion of the “routinization of charismatic authority”: the descendants of persons credited with charismatic religious authority came to assume proprietary rights over the land.[74]

If holy men or their descendants could become landlords, the reverse was also true; such was the malleability of social status on the Bengal frontier. Reversing Weber’s “routinization of charismatic authority,” one also finds a “sanctification of bureaucratic authority,” as enterprising developers or even government officials came to be locally regarded as saints capable of interceding with divine power.[75] We have noted the case of Khan Jahan ‘Ali, the fifteenth-century Turkish officer remembered for clearing the jungles of Khulna and Jessore, later popularly elevated to the positionof one of the great saints of southern Bengal. In Chittagong there is thecase of a certain Shaikh Manik. Described in contemporary sources as the zamīndār of pargana Fathapur, Shaikh Manik in 1715 notified government authorities that he had built a mosque in Paschimpati, Hathazari Thana. Complaining that he had insufficient means to maintain the institution, he appealed for some forest land to cultivate. The state gave him 54.5 acres and recognized him as the mosque’s legitimate trustee. By 1755, forty years after the construction of the mosque, a shrine had been built over the grave of the late Shaikh Manik, and his son, Ja‘far Muhammad, had emerged as the shrine’s manager. By 1755 the shrine had become so institutionalized that—in ways mimicking any bureaucratic government—it had begun issuing documents stamped with its own stylized seal: “Shrine [dargāh] of Shaikh Manik.”[76]

In such cases the vocabulary of popular Sufism stabilized in popular memory those persons who had been instrumental in building new communities. There is no evidence that either Khan Jahan or Shaikh Manik, both of them pioneers and developers, had any acquaintance with, far less mastery of, the intricacies of Islamic mysticism. Nor will their names be found in any of the great pan-Indian hagiographies. Yet from the culture of institutional Sufism came the asymmetric categories of pīr and murīd, or shaikh and disciple, which rendered Sufism a suitable model for channeling authority, distributing patronage, and maintaining discipline—the very requirements appropriate to the business of organizing and mobilizing labor in regions along the cutting edge of state power. It is little wonder that Sufis appeared along East Bengal’s forested frontier.

| • | • | • |

The Religious Gentry of Sylhet

Located in Bengal’s northeastern corner, Sylhet, like Chittagong, was densely forested at the time of its conquest by Muslims. A royal grant of the mid seventh century had described parts of this region as “outside the pale of human habitation, where there is no distinction between natural and artificial; infested by wild animals and poisonous reptiles, and covered with forest out-growths.”[77] Many of the southern tracts of what are now Sylhet and Mymensingh districts were inundated with water and inhabited by communities of non-Aryan fishermen, prominently the Kaivartas.[78] In fact, the central and southwestern part of present-day Sylhet District once formed part of a huge lake. But from the late tenth century to the early twelfth, a dynasty of semi-independent Hindu kings emerged to rule over the principality of śrihatta in the northern part of the district.[79] Its most powerful king, Govinda-Kesava (fl. ca. 1050), built a lofty Krishna temple of stone in his capital city—probably identifiable with the north and northeastern part of Sylhet town—where he amassed a force of “innumerable” war boats, infantry, cavalry, and elephants.[80] Yet the process of Brahmanization had by this time made little headway among the native communities (Kaivarta, Das, Nomo) in the region’s forested and marshy hinterland.

By the time Ibn Battuta visited Sylhet in 1345, some forty years after the Turkish conquest of the region, the large river valleys had become settled by a stable and flourishing Hindu population. “Along the banks of the (Meghna) river,” recalled the Moroccan traveler,

For the next several centuries little is known of Muslim rule in Sylhet, a distant frontier town, which throughout the sultanate period did not even possess a mint. When Akbar conquered western Bengal in the late sixteenth century, the hilly and forested tracts of southern Sylhet District became a refuge area for Afghan chieftains fleeing advancing Mughal armies. Even after the Mughals annexed Sylhet in 1612, the region seems to have remained Bengal’s “Wild East,” as we hear only sporadic reports of a Mughal presence there.[82]to the right as well as to the left, there are water wheels, gardens and villages such as those along the banks of the Nile in Egypt. The inhabitants of Habanq [ten miles south of Habiganj] are infidels under protection (dhimma) from whom half of the crops which they produce is taken; besides, they have to perform certain duties. For fifteen days we sailed down the river passing through villages and orchards as though we were going through a mart.[81]

From 1660 on, however, there is clear evidence of the agrarian growth that was quietly taking place in the region. Tables 7 and 8, which summarize the grants approved by the Sylhet faujdār’s office between 1660 and 1760, indicate the amount of jungle area transferred from state to private hands in this period. Although only one of the twenty-six faujdārs in this period was a Hindu,[83] a significant share of government patronage was extended to Hindu institutions. Indeed, the brahmottar, a tax-free land grant to a Brahman as a reward for his sanctity or learning, constituted the largest category of transfer, each one averaging 22.9 acres in size. As in Chittagong, it was not the Mughal authorities in the Sylhet headquarters who initiated these grants; Mughal faujdārs in Sylhet only confirmed agreements already concluded between local zamīndārs and Sylhet’s religious gentry. For example, a 1721 sanad confirmed a document previously drawn up by local zamīndārs who had donated 39 acres (10 qulbas) of jungle lands to a certain Mahadev Bhatacharjee, a Brahman (zunnārdār) “possessing consummate skills in the Hindu sciences.”[84] Most brahmottar grants were justified in terms of the Brahman’s poverty and his reputed mastery of Hindu knowledge.[85]

| Madad-i Ma‘āsh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmottar | Devottar | Vishnottar | śivottar | Hindu | Muslim | Chirāghī | |

| Aurangzeb (1658–1707) | 4 | 1 | — | — | 23 | 8 | 1 |

| Shah ‘Alam (1707–1712) | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Farrukh Siyar (1713–1719) | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — |

| Muhammad Shah (1719–1748) | 337 | 54 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 55 | 39 |

| Ahmad Shah (1748–1754) | 91 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 35 | 13 |

| ‘Alamgir II (1754–1759) | 95 | 25 | 1 | — | 3 | 38 | 20 |

| Total | 528 | 107 | 4 | 4 | 56 | 136 | 73 |

| Madad-i Ma‘āsh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reign | Brahmottar | Devottar | Vishnottar | śivottar | Hindu | Muslim | Chirāghī |

| Note: The original sources give these figures in units of qulba, Arabic for “plow,” equal in area to the Bengali hāl, also “plow.” In Mughal Sylhet, a qulba was equal to 12 kedār, one kedār to 4 poyā, one poyā to 3 jaṣṭi, one jaṣṭi to one square kāhaṇ, one kāhaṇ to 2 nal, and one nal to 6.25 dasta. With one dasta equal to 21.625 inches, and with 43,560 square feet equal to one acre, one qulba works out to 3.9 acres. See Kamalakanta Gupta, śrīhaṭer Bhūmi o Rājasva Babasthā (Sylhet: śrīhaṭ Sāhitya Pariṣad, 1966), 26. | |||||||

| Aurangzeb (1658–1707) | 39 | 3.9 | — | — | 760.5 | 1,248 | 195 |

| Shah ‘Alam (1707–1712) | 39 | — | — | — | 75 | — | — |

| Farrukh Siyar (1713–1719) | — | — | — | — | 42.9 | — | — |

| Muhammad Shah (1719–1748) | 6,146.4 | 2,593.5 | 7.8 | 35.1 | 429 | 9,429.3 | 1,053 |

| Ahmad Shah (1748–1754) | 2,741.7 | 889.2 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 140.4 | 12,987 | 608.4 |

| ‘Alamgir II (1754–1759) | 3,143.4 | 1,205.1 | 15.6 | — | 132.6 | 8,455.2 | 1,579.5 |

| Total | 12,109.5 | 4,691.7 | 27.3 | 39 | 1,580.4 | 32,119.5 | 3,435.9 |

| Average size | 22.9 | 43.8 | 6.8 | 9.7 | 28.2 | 236.1 | 47.1 |

The second most common type of grant to Hindus or Hindu institutions was the devottar, a tax-free transfer made over to the caretakers of a Hindu temple or image. One such grant, dated December 8, 1720, reads:

The Mughals of Sylhet also patronized Vaishnavas through grants called vishnottar, and śaivas through grants called śivottar. In 1725, for example, the government granted four qulbas (15.6 acres) of jungle and a house to Govind Das, a Vaishnava holy man (bairāgī) described as “worthy of honor,” mustaḥaqq-i wājibu’r-ri‘āyat, an Arabo-Persian phrase that would have befitted any accomplished Muslim scholar or Sufi.[87]In the home of Madhu Das Sen, a resident of Chakla Sylhet, there is an adorned image (thākur). But because of a lack of means to perform the worship of the deity, in order to provide for the Brahman priests [pūjārī] there, and for the welfare of this illustrious place, it is requested that 70 qulbas [273 acres] of jungle lands lying outside the revenue register be given to Ram Das Sen as a devottar. The area having been brought under cultivation, its produce will support the aforesaid place and its Brahman priests.[86]

Grants called chirāghī were intended to support the shrines of Muslim saints. In some cases, local revenue officials merely confirmed land transfers originally made by local zamīndārs.[88] In others, pioneers requested government sanction to clear jungle with a view to using the land’s harvests to support a shrine.[89] Still another category, madad-i ma‘āsh, were personal, tax-free grants typically awarded to men who had already founded mosques, as was the case with the sanads of Chittagong. In one such grant, a certain Shaikh Muhammad built a mosque in the forest but declared his inability to support its prayer-leader (churgar), preacher, and caller to prayer, or to pay its other expenses. On July 25, 1749, the Sylhet government responded by bestowing 390 acres (100 qulbas) of jungle “for the expenses of Shaikh Muhammad’s mosque and house, together with his children.”[90] The earliest-known grant made to the servants of the shrine of the famous Shah Jalal in Sylhet city was also a madad-i ma‘āsh. Dated August 11, 1663, this document granted 78.2 acres (20 qulbas) of jungle to the devotees at the shrine.[91] Henceforth, from the reign of Aurangzeb (1658–1707) through that of ‘Alamgir II (1754–59), devotees of the shrine continued to receive Mughal patronage.[92]

It is known that in 1672–73 the conservative emperor Aurangzeb ordered that all madad-i ma‘āsh granted to Hindus be repossessed, with future such grants reserved for Muslims only.[93] But Delhi, as the old Persian proverb went, “was still far away.” During the emperor’s reign, Mughal officers in Sylhet issued more madad-i ma‘āsh to Hindus after the 1672–73 order than before that date.[94] Still, as is seen in table 7, the Hindu share of these grants steadily decreased in proportion to the Muslim share clear down to the reign of ‘Alamgir II, when 38 of 41 madad-i ma‘āsh grants were issued to Muslims. Moreover, for all reigns combined, such grants given to Muslims averaged nine times the size of those given to Hindus—170.1 acres and 26.2 acres respectively.

As in Chittagong, the Sylhet grants combined political with economic objectives. A 1753 sanad stated that the considerable area of 4,387.5 acres (1,125 qulbas) of forest were to be “a madad-i ma‘āsh for the prayer-leader and for the expenses of the students and those who come and go, and to the laborers and the good deeds of the organization of Maulavi Muhammad Rabi‘, together with his children.”[95] Three years later another sanad ordered that an area of 975 acres (250 qulbas) of forest lying outside the revenue roll, but capable of being cultivated (jangala-yi khārij-i jam‘, lā’iq al-zirā‘at) was to be issued to the same “organization” (dastgāh), but with important differences. It was to be used

In these documents, Maulavi Muhammad Rabi‘ emerges as a figure of considerable charismatic authority and organizational ability. We do not know the identity of the laborers belonging to his “organization,” but he must have commanded considerable manpower in order to clear and cultivate stretches of forest the size of these two grants—a combined 5,363 acres. That Muhammad Rabi‘’s labor force, his mosque, and the Qur’an school were all to be supported by the harvested crops of the lands suggests that the field laborers were themselves affiliates of these Islamic institutions.for the purpose of the expenses of a mosque, a house, a Qur’an school, the dependents, those who come and go, and the faqīrs. It is also a madad-i ma‘āsh for the laborers and the good deeds of the organization of Maulavi Muhammad Rabi‘ and his children and dependents.…It is agreed that once the aforesaid land is brought into cultivation, its produce shall be used to support the expenses of the mosque, the Qur’an school, those who come and go, the faqīrs, and his own needs, together with those of his children and dependents, and that he shall busy himself in prayers for the long life of the State.[96]

The founders of new villages in Sylhet, as in East Bengal generally, had an enormous impact in shaping the subsequent religious orientation of local communities. In 1898, a time when the colonization of some of the Sylhet forest was still within living memory, a Muslim gentleman of northern Sylhet recalled that whenever a new village was founded, a temple to the goddess Kali was built if the founding landlord were a śākta Hindu, and a temple to Vishnu if he were a Vaishnava. If the majority of the villages were Vaishnava, they would build a shrine (ākhṛā) to Radha and Krishna. If the area were infested with snakes, the patron deity was the snake goddess Manasa, and if the village were founded by Muslims, a shrine to some Muslim pīr would be established.[97] In other words, grants made out to Hindus or Hindu institutions (brahmottar, devottar, vishnottar, śivottar) tended to integrate local communities into a Hindu-ordered cultural universe, while grants authorizing Muslims to establish schools, mosques, or shrines tended to integrate them into an Islamic-ordered cultural universe. Subsequent demographic patterns evolved from these earlier processes.

In Sylhet, although seventeenth- and eighteenth-century forest grants to Hindus outnumbered those to Muslims, two points offset this difference. First, the state alienated a considerably larger total of forest land to Muslims than to Hindus, as a result of which more indigenous peoples living in areas included in the grants would have been exposed to Muslim than to Hindu institutions. Second, grants made to Muslims often mentioned not only “dependents” of the grantee but also those institutional structures that cleared the forest and maintained the workers’ fixed and continued focus. The grants made out for the dastgāh, or “organization,” of laborers working for Maulavi Muhammad Rabi‘ supported not only the laborers themselves but also the mosque and the Qur’an school that would regularize the links between the laborers and formal Islam. Grants made over to śākta Brahmans or Vaishnava bairāgīs, on the other hand, mentioned neither dependents nor the sort of community-building mechanisms found in the Muslim grants.

Thus Muslim grants explicitly connected state-sponsored public works projects with the establishment of Islamic institutions. In this way, the documented cases cited above confirm the process of religious and agrarian expansion alluded to in premodern Bengali poetry, in traditions collected by the British in eastern Bengal in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and in traditions still found in the countryside today. Earlier traditions had celebrated men like Pir ‘Umar Shah, who, having come to Noakhali sometime in the eighteenth century, organized local Bengalis into labor teams and converted them to Islam (see pp. 211–12 above). Stories still circulate of how in Mughal times men came from the Middle East to the Habiganj region, where they organized the local population into groups to cut the jungle and cultivate rice. As such communities acquired an Islamic identity, they conferred on their leaders a sanctified identity appropriate to Islamic civilization, and especially to the culture of institutional Sufism, as witnessed by the growth of shrines over the graves of holy men throughout the Bengal frontier.

| • | • | • |

Summary

In the eastern delta, where settled agrarian life was far less advanced than in the west in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Islam more than other culture systems became identified with a developing agrarian social order. As state-supported pioneers established Islamic institutions in formerly forested areas, three different kinds of frontier—the economic frontier separating field and forest, the political frontier separating Mughal from non-Mughal administration, and the religious frontier separating Islam and non-Islam—fused into one.

Yet Islamic institutions were by no means the only ones that grew with Bengal’s advancing frontiers. In the forests of both Chittagong and Sylhet, new communities formed around pioneers and institutions associated with Hindu deities. In fact, the active delta was so ripe for cultural and economic development that even Christian pioneers made an impact, and this without the benefit of Mughal patronage. In 1713 the French Jesuit Père Barbier journeyed through Chittagong and into the interior of what is now Noakhali District, where he encountered a community of Christian peasants organized around the authority of a local patriarch. “At five days’ distance from Chatigan [Chittagong],” he wrote,

The old man (vieillard) Barbier encountered and identified as “le chef de ces Chrétiens” was apparently not a European but a Bengali Christian, for the Frenchman had to employ an interpreter to communicate with him.[99] Evidently the man had managed to forge for himself a clientele from amongst the local population, in effect functioning as a petty zamīndār of a local community to which he gave both religious and economic leadership.[100] In this instance, it was neither a Muslim nor a Hindu institution but a fledgling Christian one that grew with agricultural development on the Bengal frontier.we made a detour of one day to visit a Christianity [i.e., a Christian community] to be found in a place named Bouloüa [Bhallua, northwest of Noakhali town]. God maintains and directs it Himself immediately: for it is rare that any missionary goes to visit it.…

The chief of these Christians is an old man who has five sons, all married. Their family, and the labouring folk who are gathered around them (for they have taken arable lands) form a village of three to four hundred persons. The laborious life which they lead, added to the vigilance and attention of the chief, keep them in the greatest innocence.[98]

Nonetheless, while Bengal’s agrarian frontier accommodated Hindu and even Christian institutional growth, it was a Muslim gentry that received the lion’s share of patronage from Mughal district revenue officers. It was they who acquired the greatest amount of state-recognized control over patches of virgin jungle, who attracted the most local labor for reducing the land to rice paddy, and who built the mosques or shrines that in turn served as nuclei for the economic and religious transformation of micro-regions. Greater patronage ultimately favored the growth of rural Muslim communities over the growth of communities professing other religious identities.

It would be wrong, however, to explain religious change here or elsewhere as simply a cultural dimension of political or economic change, or to understand Islam itself as a timeless and fixed system of beliefs and rituals that the people of the delta passively accepted. For in the midst of the dramatic socioeconomic changes taking place in premodern Bengal, Islam creatively evolved into an ideology of “world-construction”—an ideology of forest-clearing and agrarian expansion, serving not only to legitimize but to structure the very socioeconomic changes taking place on the frontier. On the one hand, Islamic institutions proved sufficiently flexible to accommodate the non-Brahmanized religious culture of premodern Bengal. On the other, the religious traditions already present in eastern Bengal made accommodations with the amalgam of rites, rituals, and beliefs that were associated with the village mosques and shrines then proliferating in their midst. In the process, Islamic and Bengali worldviews and cosmologies became fused in dynamic and creative ways, a topic to which we now turn.[101]

Notes

1. ḥaqīqat-i ṣūba Bihār (Persian MS.). Soon after 1765, when the English East India Company acquired revenue-collecting rights in Bengal, Company officials launched inquiries into the origin of land tenure rights in Bengal and Bihar. One of several documents that emerged from those inquiries, this manuscript was cataloged under the title Kaifīyat-i ṣūba Bihār in Wilhelm Pertsch, Handschriften-Verzeichniss der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin: A. Asher, 1888), Persische Handschriften, No. 500, 4: 484. From the old Royal Library in Berlin, it was subsequently shifted to the University of Marburg Library. It is summarized, and extracts from it translated, by S. Nurul Hasan in his “Three Studies of Zamindari System,” in Medieval India—A Miscellany, vol. 1 (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1969), 237–38.

2. Jadunath Sarkar, “The Revenue Regulations of Aurangzeb,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, n.s., 2, no. 6 (June 1906): 234–35. Sarkar’s translation.

3. A study of rural Comilla District, in the southeastern delta, found that until the mid nineteenth century, the people in that district were still nomadic in nature and, “land being available, [they] could exercise free choice in selecting and reselecting habitation.” S. A. Qadir, Village Dhanishwar: Three Generations of Man-Land Adjustment in an East Pakistan Village (Comilla: Pakistan Academy for Rural Development, 1960), 46.

4. The same is true of madrasas, or schools. Although remnants of a few stone or brick schools of the sultanate period survive today, schools made of humbler materials have perished altogether. For example, in 1609 a traveler passing through Bagha, in modern Rajshahi District, recorded seeing a madrasa with grass-thatched roofs and mud-plastered walls. Inside, a host of pupils studied under a certain Hawadha Mian, a teacher of that locale. The government had granted the revenues of the countryside surrounding Bagha for the maintenance of the shaikh and his college. Today the structure no longer stands, however, and it was evidently not endowed with a foundation tablet and dedicatory inscription that would testify to its former existence. See Jadunath Sarkar, “A Description of North Bengal in 1609 A.D.,” Bengal Past and Present 35 (1928): 144.

5. “Kanun Daimer Nathi,” Chittagong District Collectorate Record Room, No. 64: bundle 78, case no. 5027; No. 7: bundle 62, case no. 4005.

6. Peter J. Bertocci, “Elusive Villages: Social Structure and Community Organization in Rural East Pakistan” (Ph.D. diss., Michigan State University, 1970), 11–14.

7. Betsy Hartmann and James Boyce, A Quiet Violence: A View from a Bangladesh Village (London: Zed Press, 1983), 17.

8. O. H.K. Spate and A. T.A. Learnmonth, India and Pakistan: A General and Regional Geography, 3d ed. (London: Methuen, 1967), 590. See the map of typical Bengali settlement patterns on p. 580.

9. E. A. Gait, “The Muhammadans of Bengal,” in Census of India, 1901, vol. 6, The Lower Provinces of Bengal and Their Feudatories, pt. 1, “Report” (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1902), 441.

10. Eric Hobsbawm, Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries (New York: Norton, 1959), 32. Similarly, in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, lineages of charismatic saints have developed networks of patronage and influence among local pastoral tribes. See Ernest Gellner, Saints of the Atlas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), chs. 3–5.

11. Ralph W. Nicholas, “Vaisnavism and Islam in Rural Bengal,” in Bengal: Regional Identity, ed. David Kopf (East Lansing: Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University, 1969), 44.

12. Ibid. For observations on this point so far as concerns western Comilla District in modern Bangladesh, see Robert Glasse, “La Société musulmane dans le Pakistan rural de l’est,” Etudes rurales 22–24 (1968): 202–4. Here, religious and non-religious authority appear to be divided between the mullā and a leader known as a mātabbar. The latter, who owes his position to his force of character and social prestige, resolves disputes, levies fines for petty infractions, and represents the group vis-à-vis the outside world.