8. Islam and the Agrarian Order in the East

Niraṇjan [God] has commanded that agriculture will be your destiny.

| • | • | • |

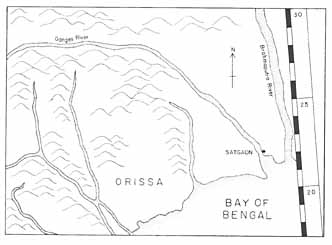

Riverine Changes and Economic Growth

A distinguishing feature of East Bengal during the Mughal period—that is, in “Bhati”—was its far greater agricultural productivity and population growth relative to contemporary West Bengal. Ultimately, this arose from the long-term eastward movement of Bengal’s major river systems, which deposited the rich silt that made the cultivation of wet rice possible. Geographers have generally explained the movement of Bengal’s rivers in terms of the natural process of riverine sedimentation. In this view, in prehistoric times the entire delta was once under the ocean, and the Ganges met the sea in what is now the region’s northwestern corner (modern Murshidabad District), while the Brahmaputra did the same in the extreme north (modern Rangpur District). As sediment and debris accumulated at the rivers’ confluence with the ocean, a small delta began to form, through which the present-day Bhagirathi River carried the bulk of the Ganges to the Bay. The continued buildup of sediment from both the Ganges and the Brahmaputra steadily pushed the delta further southward into the Bay.

But the great rivers, flowing over the flat floodplain, could not move fast enough to flush out to sea the sediment they carried, and instead deposited much of it in their own beds. When such sedimentation caused riverbeds to attain levels higher than the surrounding countryside, waters spilled out of their former beds and moved into adjoining channels.[1] In this way the main course of the Ganges, which had formerly flowed down what is now the Bhagirathi-Hooghly channel in West Bengal, was replaced in turn by the Bhairab, the Mathabhanga, the Garai-Madhumati, the Arialkhan, and finally the present-day Padma-Meghna system. “When the distributaries in the west were active,” writes Kanangopal Bagchi, “those in the east were perhaps in their infancy, and as the rivers to the east were adolescing, those in the west became senile. The active stage of delta formation thus migrated southeastwards in time and space, leaving the rivers in the old delta, now represented by Murshidabad, Nadia and Jessore with the Goalundo Sub-Division of Faridpur, to languish or decay.”[2] As the delta’s active portion gravitated eastward, the regions in the west, which received diminishing levels of fresh water and silt, gradually become moribund. Cities and habitations along the banks of abandoned channels declined as diseases associated with stagnant waters took hold of local communities. Thus the delta as a whole experienced a gradual eastward movement of civilization as pioneers in the more ecologically active regions cut virgin forests, thereby throwing open a widening zone for field agriculture. From the fifteenth century on, writes the geographer R. K. Mukerjee, “man has carried on the work of reclamation here, fighting with the jungle, the tiger, the wild buffalo, the pig, and the crocodile, until at the present day nearly half of what was formerly an impenetrable forest has been converted into gardens of graceful palm and fields of waving rice.”[3]

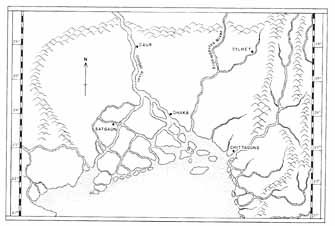

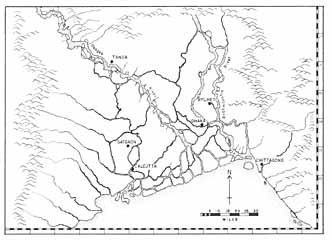

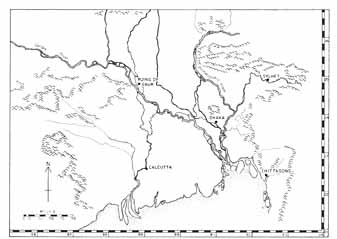

Map 5. Changing courses of Bengal rivers, 1548–1779

Map 5a. 1548 (Gastaldi)

Map 5b. 1615 (de Barros)

Map 5c. 1660 (van den Broeke)

Map 5d. 1779 (Rennell)

Although the process described by Mukerjee had actually begun long before the fifteenth century, it dramatically intensified after the late sixteenth century. As contemporary European maps show, this was when the great Ganges river system, abandoning its former channels in western and southern Bengal, linked up with the Padma, enabling its main course to flow directly into the heart of the east (see maps 5b and c). Already in 1567 the Venetian traveler Cesare Federici observed that ships were unable to sail north of Satgaon on the old Ganges—that is, today’s Bhagirathi-Hooghly in West Bengal.[4] About the same time the Ganges silted up and abandoned its channels above Gaur, as a result of which that venerable capital of the sultanate, only recently occupied by Akbar’s forces, suffered a devastating epidemic and had to be abandoned. In 1574 Abu’l-fazl remarked that the Ganges River had divided into two branches at the Afghan capital of Tanda: one branch flowing south to Satgaon and the other flowing east toward Sonargaon and Chittagong.[5] In the seventeenth century the former branch continued to decay as progressively more of its water was captured by the channels flowing to the east, to the point where by 1666 this branch had become altogether unnavigable.[6]

To the east, however, these changes had the opposite effect. With the main waters of the Ganges now pouring through the channel of the Padma River, the combined Ganges-Padma system linked eastern Bengal with North India at the very moment of Bengal’s political integration with the Mughal Empire. Geographic and political integration was swiftly followed by economic integration, for direct river communication between East Bengal and North India would have dramatically reduced costs for the transport of East Bengali products, especially textiles and foodstuffs, from the frontier to the imperial metropolis. At the same time, the main body of Ganges silt, now carried directly into the east, was deposited over an ever greater area of the eastern delta during annual flooding. This permitted an intensification of cultivation along the larger rivers where rice culture had already been established, and an extension of cultivation into those parts of the interior not yet brought under the plow. As a result, East Bengal attained agricultural and demographic growth at levels no longer possible in the western delta. These changes are reflected above all in the statistics of the Mughal government’s share (khāliṣa) of the land revenue demand (jama‘). Since the revenue demand represents the government’s estimate of the land’s income-generating capacity, and since Bengal’s major income-producing activity was the cultivation of wet rice, a labor-intensive crop, these statistics also suggest changes in the relative population density of different sectors within the delta.

| Revenue Demand (in rupees) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrant | 1595 | 1659 | Percentage Change |

| Sources: For 1595: Abu’l-fazl ‘Allami, ā’īn-i Akbarī, as given in Shireen Moosvi, The Economy of the Mughal Empire, c. 1595: A Statistical Study (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1987), 26–27. For 1659: Dastūr al-‘amal-i ‘ālamgīrī (British Library MS., Add. 6599), fols. 120a–121a. | |||

| Note: Totals stated for sarkārs are given in dāms, which must be divided by 40 to give the rupee equivalent. Areas included in the northwest quadrant are the Mughal sarkārs of Purnea, Tajpur, Gaur (Lakhnauti), Panjra, and Barbakabad; for the southwest quadrant, sarkārs Tanda (Udambar), Sharifabad, Satgaon, Sulaimanabad, and Mandaran; for the northeast quadrant, sarkārs Ghoraghat, Bazuha, and Sylhet; for the southeast quadrant, sarkārs Mahmudabad, Khilafatabad, Fatehabad, Bakla, Sonargaon, and Chatgaon. As most of the eastern sarkārs lay beyond Mughal administration in 1595, imperial revenue officials evidently based their figures for those districts on records, known to them but lost today, of the independent sultans of Bengal. By 1659 all of Bengal had come under Mughal administration with the exception of Chittagong (Chatgaon), then still under Arakanese overlordship and not annexed until 1666. Provincial revenue officers nonetheless obtained current revenue figures for Chittagong and included them in the revenue demand for the entire province. | |||

| Northwest | 1,374,859 | 1,190,064 | –13% |

| Southwest | 2,258,138 | 3,482,127 | +l54% |

| Northeast | 1,379,529 | 2,720,115 | +l97% |

| Southeast | 1,346,730 | 2,921,314 | +l117% |

| Total | 6,359,256 | 10,313,620 | +l62% |

Table 4 divides the delta into four quadrants and shows changes in revenue demand for each quadrant during the first century of Mughal rule. It can be seen that between 1595 and 1659 the revenue demand for the northeastern portion of the delta increased by 97 percent, while that of the southeastern quadrant, the most ecologically active part of Bengal, increased by 117 percent. On the other hand, the revenue demand for southwestern Bengal, an ecologically older sector, increased by only 54 percent in this period, while that for northwestern Bengal, the most moribund part of the delta, actually declined by 13 percent. These earlier trends in Bengal’s changing regional fertility compare with demographic data drawn from the modern period. During the century between 1872 and 1981, as is shown in table 5, population density increased much more in the eastern half of Bengal, averaging 323 percent, than it did in the western half, where it averaged 196 percent.[7] Thus both seventeenth-century revenue data and nineteenth- and twentieth-century demographic data point to a moving demographic frontier, the product of a long-term process whereby land fertility, rice cultivation, and population density all grew at a faster rate in the east than in the west.

| Population per sq. mi. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrant | 1872 | 1981 | Percentage Increase |

| Sources: H. Beverley, Report on the Census of Bengal, 1872 (Calcutta: Secretariat Press, 1872), 6–9; Census of India, 1981 (New Delhi, 1985), pt. II-A [i], “General Population Tables,” section 2, 182–85; The Preliminary Report on Bangladesh Population Census, 1981 (Dacca: Bangladesh Secretariat, 1981), 2–3. The districts included in the northwest quadrant are the 1872 districts of Rangpur, Bogra, Pabna, Dinajpur, Malda, Rajshahi, and Murshidabad. Those included in the southwest quadrant are Burdwan, Bankura, Birbhum, Midnapur, Hooghly and Howrah, Twenty-four Parganas, and Nadia. Those included in the northeast quadrant are Mymensingh, Sylhet, and Dhaka. And those included in the southeast quadrant are Jessore (including Khulna), Tippera (Comilla), Faridpur, Bakarganj, Noakhali, and Chittagong. | |||

| Northwest | 503 | 1,544 | 207% |

| Southwest | 598 | 1,701 | 184% |

| Northeast | 406 | 1,933 | 376% |

| Southeast | 526 | 1,941 | 269% |

As a result, already by the late sixteenth century, southern and eastern Bengal were producing so much surplus grain that for the first time rice emerged as an important export crop. From two principal seaports, Chittagong in the east and Satgaon in the west, rice was exported throughout the Indian Ocean to points as far west as Goa and as far east as the Moluccas in Southeast Asia.[8] In this respect rice now joined cotton textiles, Bengal’s principal export commodity since at least the late fifteenth century, and a major one since at least the tenth. In 1567 Cesare Federici judged Sondwip to be “the fertilest Iland in all the world,” and recorded that one could obtain there “a sacke of fine Rice for a thing of nothing.”[9] Twenty years later, when ‘Isa Khan still held sway over Sonargaon, Ralph Fitch wrote: “Great store of Cotton doth goeth from hence, and much Rice, wherewith they serve all India, Ceilon, Pegu, Malacca, Sumatra, and many other places.”[10] The most impressive evidence in this regard comes from François Pyrard. After spending the spring of 1607 in Chittagong, still under independent rulers beyond the Mughals’ grasp, the Frenchman wrote:

Under the Mughals the export of surplus rice continued unabated, and indeed grew.[12] In 1629 Fray Manrique noted that every year over a hundred vessels laden with rice and other foodstuffs left Bengali ports for overseas export.[13] And in common with earlier observers, Manrique was impressed by the low prices of local foodstuffs.[14] Although the eastward export of rice declined from about 1670 on,[15] in lower Bengal it remained cheap and abundant throughout the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth, for in 1763 an English observer wrote that rice, “which makes the greater part of their food, is produced in such plenty in the lower parts of the province, that it is often sold on the spot at the rate of two pounds for a farthing.”[16]There is such a quantity of rice, that, besides supplying the whole country, it is exported to all parts of India, as well to Goa and Malabar, as to Sumatra, the Moluccas, and all the islands of Sunda, to all of which lands Bengal is a very nursing mother, who supplies them and their entire subsistence and food. Thus, one sees arrive there [i.e., Chittagong] every day an infinite number of vessels from all parts of India for these provisions.[11]

If the most productive area of rice production gradually shifted eastward together with the locus of the active delta, the production of cash crops, especially cotton and silk, flourished throughout the delta in the Mughal period. The most important centers of cotton production were located around Dhaka and along a corridor in western Bengal extending from Malda in the north through Cossimbazar to Hooghly and Midnapur in the south.[17] In 1586 Ralph Fitch remarked that in Sonargaon, just fifteen miles east of Dhaka, “there is the best and finest cloth made of Cotton that is in all India.”[18] Even in distant Central Asia fine muslin cloth was called Dāka,[19] a consequence of Bengal’s political integration with North India, and of its access to markets both there and beyond.[20] The Mughal connection also made Bengal a major producer for the imperial court’s voracious appetite for luxury goods. This was especially so in the case of raw silk, whose major center of production was located in and around Cossimbazar in modern Murshidabad District.[21]

Bengal’s agricultural and manufacturing boom coincided not only with the consolidation of Mughal power in the province but also with the growth in overland and maritime trade that linked Bengal ever more tightly to the world economy. We have already noted that the thirteenth-century Muslim conquest of the delta had been followed by increased exports of Bengali textiles to Indian Ocean markets.[22] Later, during the twilight years of the sultanate, Portuguese merchants intruded themselves into the Bay of Bengal, establishing trading stations in both Chittagong and Satgaon in the mid 1530s. In the last two decades of the sixteenth century, during the Mughal push into the heart of the delta, the Portuguese established the major port of Hooghly (downstream from Satgaon), built up their community in Chittagong, and established mercantile colonies in and around Dhaka. Although the Portuguese never replaced Asian merchants in Bengal’s maritime trade, as is often supposed,[23] the appearance of European merchants in the sixteenth century certainly stimulated demand for Bengali manufactures, which served to accelerate local production of those goods.

In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch and English trading companies gradually replaced the overextended Portuguese as the dominant European merchants in Bengal’s port cities. Granted permission by Shah Jahan in 1635 to trade in Bengal, the Dutch East India Company opened a trading station at Hooghly the following year. In 1650 it ordered 50,000 lbs. of raw silk from Bengali suppliers, and four years later this figure grew to 200,000 lbs.[24] By the end of the seventeenth century, the export of raw silk and cotton textiles had grown so rapidly that Bengal emerged as Europe’s single most important supplier of goods in all of Asia.[25] But this manufacturing boom did not result from European stimulus alone. Clear down to the 1760s Asian merchants—especially Gujaratis, Armenians, and Punjabis—bought even more Bengali textiles than did Europeans, and exported them throughout South Asia and the Indian Ocean region.[26]

One consequence of this manufacturing boom was that substantial quantities of silver were attracted from outside the province, whether carried by European or Asian merchants. In 1516 Bengali ships carrying local textiles to Burma brought mainly silver back to the delta.[27] And in the 1550s the Portuguese found themselves shipping so much treasure to Bengal that the value of silver currency in Goa actually fluctuated with their sailing seasons to Bengal and Malacca.[28] From the second half of the seventeenth century on, we have precise figures in this matter. The Dutch alone imported an annual average of 1.28 million florins in treasure during the 1660s, and 2.87 million florins in the 1710s.[29] To this must be added the imports of the English East India Company, which in 1651 had also established a trading factory in Hooghly. Between 1709 and 1717 the two companies together shipped cargoes averaging Rs. 4.15 million in value into Bengal annually, 85 percent of which was silver.[30] Advanced to Bengali agents, merchants, or weavers, this treasure was absorbed into the regional economy, adding considerably to the existing stocks of rupee coinage already in circulation.[31] All the while, the overland import of silver by Asian merchants continued until the very end of Mughal rule in the delta.[32]

Economists have long understood the inflationary effects that any increase in money supply can have on regional economies. In the sixteenth century, for example, the massive import of treasure from Mexico to Spain is thought to have contributed to price inflation in the latter country.[33] In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Mughal India experienced a similar expansion in money supply, but ten or twenty years after Spain, suggesting that much of the silver mined in America and hauled to Europe was then re-exported to India.[34] Moreover, there is evidence that in Mughal India, as in Spain, the influx of silver caused consumer price inflation, at least in the western and northern domains of the empire.[35]

But in Bengal during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the well-documented influx of silver had no such inflationary effect on consumer prices, which remained stable throughout this period.[36] Such an outcome might be explained if, during these centuries, the influx of outside coinage or bullion had been offset by a proportionate outflow of precious metal from Bengal to North India in the form of enhanced revenues. It is true that provincial authorities gradually increased land revenue demand between 1659 and 1722.[37] But the amount of revenue actually sent to Delhi remained about the same throughout this period, while the additional taxes imposed on the peasantry and collected seem to have stayed in Bengal.[38] Some silver doubtless left the delta when high-ranking officers or governors like Shaista Khan (1664–78), Khan Jahan Bahadur Khan (1688–89), or ‘Azim al-Din (1697–1712) embezzled large sums of provincial revenue, some of which they took with them when they were transferred out of the province.[39] But such practices by self-serving officers were probably commonplace throughout the Mughal period, and they cannot alone explain the absence of price inflation from the mid seventeenth century on.

One can, on the other hand, relate Bengal’s known price stability between ca. 1650 and 1725 to the economic boom then taking place in the province. Put simply, consumer prices remained stable because the production of agricultural and manufactured goods, together with the population base, grew at levels high enough to absorb the expanding money supply caused by the influx of outside silver. Moreover, since additional increments to the money supply did not flow out of the province, newly minted silver percolated freely throughout Bengali society, penetrating ever lower levels and facilitating the kinds of land transfers and cash advances that necessarily accompanied an expanding agrarian frontier. The importance of ready cash in this process is suggested in Mukundaram’s Caṇḍī-Maṅgala, composed around 1590. In it, the goddess Chandi gives the poem’s hero, Kalaketu, a valuable ring and tells him to exchange it for cash. With the money thus obtained—seventy million tankas—Kalaketu is to clear the forest and establish a city and temple in honor of the goddess. Once the land is ready for agricultural operations, Kalaketu promises to advance Kayastha landlords as much cash as they need for their own thousands of laborers (prajā, lit., “subjects”) to come and settle on the newly claimed lands.[40] Such contemporary literary evidence points, not only to the high level of monetization in the late sixteenth century, but to the role that cash played in transforming virgin jungle into settled agrarian communities.

In sum, a number of factors—natural, political, and economic—combined to create the seventeenth century’s booming rice frontier in theeast: the eastward movement of Bengal’s rivers and hence of the active delta, the region’s political and commercial integration with Mughal India, and the growth in the money supply with the influx of outside silver in payment for locally manufactured textiles. We shall see that the high volume of cash circulating in Bengal during the Mughal period not only contributed to the movement of men and resources to and within the frontier. It also depersonalized economic transactions by permitting land to change hands across communal or cultural lines. Finally, Bengal’s rice boom coincided both in time and place—the eastern delta between the late sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries—with the emergence of a Muslim peasantry. Such a correlation between economic change and religious change invites inquiry into their possible connections.

| • | • | • |

Charismatic Pioneers on the Agrarian Frontier

The advance of wet rice agriculture into formerly forested regions is one of the oldest themes of Bengali history. Wang Ta-yüan, the Chinese merchant who visited the delta in 1349–50, observed that the Bengalis “owe all their tranquility and prosperity to themselves, for its source lies in their devotion to agriculture, whereby a land originally covered with jungle has been reclaimed by their unremitting toil in tilling and planting.…The riches and integrity of its people surpass, perhaps, those of Ch’iu-chiang (Palembang) and equal those of Chao-wa (Java).”[41]

Although peoples of the delta had been transforming forested lands to rice fields long before the coming of Muslims, what was new from at least the sixteenth century on was the association of Muslim holy men (pīr), or charismatic persons popularly identified as such, with forest clearing and land reclamation. In popular memory, some of these men swelled into vivid mythico-historical figures, saints whose lives served as metaphors for the expansion of both religion and agriculture. They have endured precisely because, in the collective folk memory, their careers captured and telescoped a complex historical socioreligious process whereby a land originally forested and non-Muslim became arable and predominantly Muslim. Let us begin by examining twentieth-century narratives and work our way back through the nineteenth, eighteenth, and seventeenth centuries to the sixteenth century, the earliest period to which traditions of pioneering holy men in Bengal can confidently be dated.

According to oral narratives collected in the 1980s, a certain Mehr ‘Ali is said to have come to the jungles of Jessore from the Deccan in the early Mughal period, accompanied by his sister and another companion. Having arrived in a settlement now named after him, Mehrpur, this holy man assisted the local population in clearing the jungle and in making possible the cultivation of wet rice.[42] In Murarbond, in the Habiganj region of Sylhet District, Shah Saiyid Nasir al-Din is said to have come from the Middle East in the Mughal period and instructed the local population in clearing the land and planting rice; before him, the land had been jungle. He also taught them the rudiments of Islam. In Pail, several miles from Habiganj, stands the shrine of another pioneer holy man who is said to have come from the Middle East and taught the local people the techniques of rice farming and the fundamentals of Islam. Later, his sons settled in what are now the Comilla and Sylhet districts, where they did the same.[43] In Pingla, Midnapur District, a Muslim holy man named Khondkar Shah ‘Ala is said to have founded a settlement on land donated by Sultan Taj Khan Karrani (r. 1564–65), who instructed the pīr to let a horse roam from dawn to noon, with the understanding that the enclosed area would be his spiritual and terrestrial domain for life. Arriving and settling in the area with his family, Khondkar Shah cleared the area of its forests with the help of the local people, whom he converted to Islam. Both during and after his lifetime the community honored him as their pīr.[44]

The gazetteer for Khulna District, compiled in 1908, reports that in the early twentieth century parts of the Sundarban forests were still identified with the charismatic authority of Muslim holy men.[45] In 1898 James Wise wrote of Zindah Ghazi, a legendary protector of woodcutters and boatmen all over the eastern delta, who was “believed to reside deep in the jungle, to ride about on tigers, and to keep them so subservient to his will that they dare not touch a human being without his express commands.”[46] In 1833 another British officer, Francis Buchanan, noted that pīrs and tigers of Dinajpur District usually inhabited the same tracts of the woods:

The earliest European notice of the symbiotic relationship between the delta’s tigers and its Muslim holy men, or their tombs, dates to 1670.[48]As these animals seldom attack man in this district, the Pir is generally allowed by persons of both religions to have restrained the natural ferocity of the beast, or, as it is more usually said, has given the tiger no order to kill man. The tiger and Faquirs [holy men] are therefore on a very good footing, and the latter…assures the people that he [the tiger] is perfectly harmless toward all such as respect the saint, and make him offerings.[47]

Based on traditions collected in 1857, Wise also wrote of Mubarra Ghazi, a legendary pīr identified with clearing the Sundarban forests of Twenty-four Parganas. This saint, he wrote, “is said to have been a faqir, who reclaimed the jungle tracts along the left bank of the river Hooghly, and each villager has an altar dedicated to him. No one will enter the forest, and no crew will sail through the district, without first of all making offerings to one of the shrines. The faqirs residing in these pestilential forests, claiming to be lineally descended from the Ghazi, indicate with pieces of wood, called Sang, the exact limits within which the forest is to be cut.”[49] By appealing to the saint’s authority for delimiting the areas in the forest to be cut, men claiming descent from Mubarra Ghazi continued to acknowledge the saint’s religious sovereignty in this part of the delta.

Another nineteenth-century narrative concerns the career of Khan Jahan (d. 1459), the patron saint of Bagerhat in Khulna, near the edge of the Sundarban forests. The inscription on his tomb identifies this man as “Ulugh Khan-i ‘Azam Khan Jahan,” suggesting he was an ethnic Turk (“Ulugh”) and a high-ranking officer (“Khan-i ‘Azam”) in the Bengal sultanate.[50] His remembered accomplishments include clearing the local jungle preparatory to rice cultivation, converting the local population to Islam, and constructing many roads and mosques in the area.[51] According to local traditions collected in 1870, he had come to the region

Khan Jahan was clearly an effective leader, since superior organizational skills and abundant manpower were necessary for transforming the region’s formerly thick jungle into rice fields: the land had to be embanked along streams in order to keep the salt water out, the forest had to be cleared, tanks had to be dug for water supply and storage, and huts had to be built for the workers. When these tasks were accomplished, rice had to be planted immediately, lest a reed jungle soon return. These were all arduous operations, made more difficult by the ever-present dangers of tigers and fevers.[53] Khan Jahan also turned his men to stupendous works of architecture. Surveys have credited him with having built over fifty monuments around Bagerhat, while oral traditions claim for him 360 mosques and as many large tanks.[54] Some 126 tanks in Bara Bazar, ten miles north of Jessore town, are also attributed to him, as is the construction of numerous roads in the Bagerhat region.[55] The unparalleled masterpiece of the Bagerhat complex is the Saithgumbad mosque, which, with its sixty-seven domes and measurements of 157 by 106 feet, is even today the largest mosque in Bangladesh.[56] In short, Khan Jahan is remembered, not just as a forest pioneer, but as a civilization builder in the widest sense.to reclaim and cultivate the lands in the Sundarbans, which were at that time waste and covered with forest. He obtained from the emperor, or from the king of Gaur, a jaghir [revenue assignment] of these lands, and in accordance with it established himself on them. The tradition of his cutcherry site [court] in both places corresponds with this view of his position, and the fact of his undertaking such large works—works which involve the necessity of supporting quite an army of laborers—also points to his position as receiver of the rents, or chief of the cultivation of the soil.…After he had lived a long time as a great zamindar, he withdrew himself from worldly affairs and dwelt as a faqir.[52]

From eighteenth-century British revenue accounts, we learn of Pir ‘Umar Shah, the patron saint of Ambarabad in Noakhali District. This man, after whom the region was named, is said to have come to the jungles of Noakhali from Iran in the early 1700s and to have “lived there in his boat working miracles and making multitudes of converts by whom the wastes were gradually reclaimed.”[57] The area cleared by Pir ‘Umar Shah and his local followers covered about 175 square miles of land, which Mughal authorities in 1734 declared a separate pargana, their basic territorial unit of administration. Some thirty years later, control over revenue collection in Bengal passed to the British, who described the area as virgin forest recently cleared and brought into cultivation for the first time by a number of small landholders called jangal-burī ta‘alluqdārs, or “jungle-cutting landholders.” These landholders claimed that they had originally been independent of any governmental authority, and only later had “requested” Mughal authorities to appoint collectors, or zamīndārs, to manage the collection of their revenue due to the state. The first two collectors were the sons of Pir ‘Umar Shah, the man who had converted the local people to Islam and organized them for the purpose of clearing the jungle. The ta‘alluqdārs allowed both sons a share of the revenue of several of their villages, and in 1734 one of them, Aman Allah, built a mosque in the town of Bazra, five miles north of Begamgunj.[58] Mughal authority and Islamic institutions thus reached the Noakhali interior at roughly the same time.

Pir ‘Umar Shah must have established contact with the people of Noakhali before 1734, for that was when Mughal authorities organized the region he settled into a pargana, by definition a district capable of producing revenue. Although the men who cleared the forests claimed to have “requested” government-appointed revenue collectors, it is more likely that by 1734 they were forced to come to terms with Mughal power in that part of Noakhali, and that the provincial government, recognizing the sons of Pir ‘Umar Shah as persons of local influence on their southeastern frontier, found it expedient to rely on them for purposes of revenue collection. Thus, as the state incorporated these forest-dwelling peoples within its political orbit, the charismatic authority of the pīr became routinized into the bureaucratic authority of the pīr’s two sons, now transformed into government collectors.

Legends of pioneering pīrs can be found in Bengali literature of the seventeenth century. The epic poem Rāy-Maṅgala, composed by Krishnaram Das in 1686, concerns a conflict between a tiger god named Daksin Ray and a Muslim named Badi‘ Ghazi Khan. As the former name means “King of the South,” or Lower Bengal, the tiger god was evidently understood as a sovereign deity of the Sundarban forest generally, whereas Badi‘ Ghazi Khan likely represents a personified memory of the penetration of these same forests by Muslim pioneers. Although the encounter between these two was initially hostile, the conflict was ultimately resolved in compromise: the tiger god would continue to exercise authority over the whole of Lower Bengal, yet people would show respect to Badi‘ Ghazi Khan by worshiping his burial spot, marked by a symbol of the tiger god’s head.[59] In this, way Badi‘ Ghazi Khan, probably the legendary residue of some sanctified pioneer like Khan Jahan or Pir ‘Umar Shah, was remembered as having established the cult of Islam in the Sundarban forests.

It was also in the seventeenth century that traditions concerning Bengal’s most famous Muslim saint, Shah Jalal Mujarrad (d. 1346) of Sylhet, became transformed in ways approximating present-day oral accounts. We have seen in Chapter 3 that the earliest written record of Shah Jalal’s life, composed in the mid 1500s, identified the saint as a Turk sent to India by a Central Asian pīr for the purpose of waging war against the infidel. Later hagiographical traditions, however, substantially reinterpreted his career. The Suhail-i Yaman, a biography compiled in the mid nineteenth century, but based on manuscripts dating to the seventeenth century,[60] identifies the saint not as a Turk from Turkestan sent to India by a Central Asian Sufi but as an Arab from Yemen sent to India by a Sufi master in Mecca.[61] Giving him a clump of soil, the master instructed Shah Jalal to wander through the world until he found a place whose soil exactly corresponded to it. Only after he had reached Bengal and assisted in the defeat of the raja of Sylhet did he discover that the soil there exactly matched his clump. He therefore selected the mound of earth he had tested as the site of his khānaqāh, or Sufi hospice.[62] An almost identical version of this story is found in oral traditions recounted in the 1970s by villagers of Pabna District, nearly two hundred miles west of Sylhet in the central delta. When asked about the Islamization of Bengal, they responded with the story of Shah Jalal and his clump of soil, maintaining that one of the reasons Islam had flourished in the delta was that the soil had been right for Shah Jalal’s message.[63] Thus, if sixteenth-century biographers depicted Shah Jalal as a holy warrior, and used his career as a vehicle for explaining the political transition from Hindu Bengal to Muslim Bengal, traditions dating from the seventeenth century saw Shah Jalal through the prism of agrarian piety, and viewed the saint as representing Bengal’s transition not only from pre-Islam to Islam, but from a pre-agrarian to an agrarian economy.

The sixteenth century is the earliest firm horizon for the appearance of pioneering shaikhs in either Persian or Bengali sources. Composed in the Burdwan region around 1590, at the dawn of Mughal rule in Bengal, Mukundaram’s Caṇḍī-Maṅgala celebrates the goddess Chandi and her human agent, the hunter Kalaketu.[64] As noted above, the goddess entrusted Kalaketu with temporal sovereignty over her forest kingdom on the condition that he, as king, renounce the violent career of hunting and bring peace on earth by promoting her cult. To this end Kalaketu was enjoined to oversee the clearing of the jungle and to establish there an ideal city whose population would cultivate the land and worship the king’s divine benefactor, Chandi. Just as the goddess extended her protection to the king, so also Kalaketu extended his protection to the peasants, to whose chiefs he gave golden earrings, symbolizing his intermediary role between them and the goddess. To assist the beginnings of agriculture, Kalaketu promised not to collect any revenue for six years. Moreover, he gave each cultivator a document (pāṭṭā) recognizing his tenure, and specified that payment of taxes, when collected, would be based on the number of plows. Attracted by such favorable terms and promises, peasants and other rural castes representing the full complement of Bengali society as Mukundaram saw it, emerged in the new forest kingdom and took an oath of loyalty to the king by accepting a piece of betel from his mouth.

Mukundaram’s poem can thus be read as a grand epic dramatizing the process of civilization-building in the Bengal delta, and specifically, the push of agrarian civilization into formerly forested lands. It is true that the model of royal authority that informed Mukundaram’s work is unambiguously Hindu. The king, Kalaketu, was both a devotee of the forest goddess Chandi and a Hindu raja in the medieval (i.e., post-eighth-century) sense, while the peasant cultivators in the poem showed their allegiance to the king by accepting betel nut from his mouth, an act drawing directly on the common Hindu ritual expressing devotion to a deity, the pūjā ceremony. Yet it was Muslims who were the principal pioneers responsible for clearing the forest, making it possible for both the city and its rice fields to flourish. “The Great Hero [Kalaketu] is clearing the forest,” wrote the poet,

Muslim pioneers are here unambiguously associated with important processes taking place in the poet’s time—the clearing of forests and the establishment of local markets. Moreover, the Muslims involved in forest-clearing operations are said to have come from the west, suggesting origins in Upper India or beyond, in contrast to the aboriginals (“the Das people”) who came from the north and the harvesters who came from the south—that is, from within the delta. Far surpassing the other pioneers in point of numbers, the twenty-two thousand Muslims were led by one “Zafar Mian,” evidently the chieftain or the organizer of the Muslim work force. It is also significant that members of that force of laborers chanted the name of a pīr, quite possibly that of Zafar Mian himself.[66] In sum, while the poem cannot be read as an eyewitness historical narrative, we know that its author drew the themes of his poem from the culture of his own day. Even if there had been no historical “Zafar Mian,” the poet was clearly familiar with the theme of thousands of Muslims attacking the forest under the leadership of charismatic pīrs.

Hearing the news, outsiders came from various lands. The Hero then bought and distributed among them Heavy knives [kāṭh-dā], axes [kuṭhār], battle-axes [ṭāngī], and pikes [bān]. From the north came the Das (people), One hundred of them advanced. They were struck with wonder on seeing the Hero, Who distributed betel nut to each of them. From the south came the harvesters Five hundred of them under one organizer. From the west came Zafar Mian, Together with twenty-two thousand men. Sulaimani beads in their hands, They chanted the names of their pīr and the Prophet [pegambar]. Having cleared the forest They established markets. Hundreds and hundreds of foreigners Ate and entered the forest. Hearing the sound of the ax, Tigers became apprehensive and ran away, roaring.[65]

As a final literary illustration of Islamization and agrarian expansion, we may examine the legendary career of Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi, the patron saint of Pandua in the northwestern delta. In Chapter 3, we saw that early Persian hagiographies identify this saint as a holy warrior and a destroyer of temples. But a quite different view of Shaikh Tabrizi is found in an extraordinary Sanskrit text, Sekaśubhodayā. Although the events described in this work are set in the period immediately prior to the Turkish conquest, and although its author purports to have been the minister of Lakshmana Sena, the Hindu king defeated by the Turks in 1204, the composition of the text as we have it dates from the sixteenth century.[67] This means that the composition of the Sekaśubhodayā, like that of Mukundaram’s Caṇḍī-Maṅgala, was contemporary with the early consolidation of Mughal power in the delta. Like Mukundaram’s and Krishnaram Das’s poems, this too belongs to the maṅgala-kāvya genre of premodern Bengali literature, a genre that typically glorified a particular deity and promised the deity’s followers bountiful auspiciousness in return for their devotion. The hero of the Sekaśubhodayā is not a traditional Bengali deity, however, but Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi himself.[68]

The account makes Shaikh Tabrizi a native not of Tabriz in Iran but of the kingdom of “Aṭṭāva”[69]—perhaps identifiable with ancient āṭavya, in present-day Mandia District, Madhya Pradesh—and relates that the holy man had been ordered by the “Great Person” (pradhānpuruṣa, i.e., God) to go to “the eastern country,” where he would meet Raja Lakshmana Sena, known for his hostility to Muslims.[70] The account thus fixes Shaikh Tabrizi’s career in Bengal at a time before the Turkish conquest.[71] Giving him an amulet, a pot of water, a staff (Ar., ‘aṣā), a pair of shoes with which to walk on fire or water, and the necklaces of two celestial nymphs, the “Great Person” charged Shaikh Tabrizi with the task of building a “house of God” (devasadana), or mosque, in Lakshmana Sena’s kingdom.[72] After traveling to “the eastern country” the shaikh, wearing his magical shoes, reached the banks of the Ganges in the Sena capital city.

The two having met, the shaikh questioned the validity of the king’s title “ruler of the earth” and challenged the Hindu monarch to cause a nearby heron to release a fish caught in its bill. When the king declined, the shaikh merely glanced at the bird, which at once dropped the fish. Seeing this, the astonished Lakshmana Sena asked for the shaikh’s grace (prasād),[74] and from then on remained a steadfast devotee of Shaikh Tabrizi, who assured him, “As long as I am (here) you have nothing to fear.”[75] Meanwhile the shaikh proceeded to win over the city’s populace by performing a variety of miracles, such as subduing three tigers that had threatened the son of a washerman, reviving a dead man, and rescuing a ship caught in a gale.[76]Bowing low his head to the (river) goddess after muttering “Ganga, Ganga,” the king saw him in the west, (walking) over water. He, wearing black clothes, stalwart, engaged in putting on a turban and looking about, was approaching the king quicker and quicker.…The king said: “I have indeed seen a wondrous act: (a man) rising up from the stream and walking on water. His person appears shining with the glow of penance.”[73]

It is when Shaikh Tabrizi sets out to build a mosque, to be located in the ancient Hindu political center of Pandua, that the story takes on special interest. Having first cleared the selected mosque site of demons, the shaikh consecrates the area by offering handfuls of holy water in turn to the “Great Person,” to Sunrise Mount in the east, to the Himalayas to the north, to his parents, to the people of the world, to any king who will honor him, to anyone in the village who will honor him, and to those who desire money and children.[77] For his part, Lakshmana Sena donates forest land for the site of the mosque and orders masons to contribute their labor toward building it. This done, Shaikh Tabrizi “invited people from the country and had them settled in that land.”[78] Thus we see a division of labor between the Muslim holy man and the Hindu monarch: the former performs magical and ritual feats appropriate for establishing the mosque, while the latter discharges the kingly functions of donating forest land and mobilizing a labor force. It is significant that the shaikh is made to play the central role in the land’s transition from forest to paddy; it is he, and not the monarch, who invites people to settle the formerly forested land.

The text also tells us how the mosque, once built, was managed. The shaikh informed Lakshmana Sena that the institution should be endowed so that it could make a charitable donation of fifty coins a day to all persons, whether kings or beggars. When asked for money for this purpose, the king replied that he did not have the cash, but would donate villages and lands instead. This done, Shaikh Tabrizi acquired a list of settled villages, ordered them surveyed, and had documents prepared fixing their combined revenue at 22,000 (coins).[79] “Then,” continued the text, “the sheikh brought (all men) together and issued documents of settlement.” When this was done, he arranged for the daily distribution of the revenues in charity to indebted persons, travelers, the lowborn, and the poor.[80]

We are not concerned here with recovering the “historical” Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi. We should rather see the Sekaśubhodayā as revealing the folk process at work: the shaikh’s career is made a metaphor for historical changes experienced by people all over the delta. Above all, the story seeks to make sense of the gradual cultural shift, well under way by the sixteenth century, when the text achieved its present form, from a Bengali Hindu world to a Bengali Muslim world. This was accomplished in part by presenting the new in the guise of the familiar. Even as Shaikh Tabrizi established what was initially an alien cult, he did so within a Hindu conceptual framework: his person shone with “the glow of penance,” or tapah-prabhāb, which in classical Indian thought refers to the power acquired through the practice of ascetic austerities; the “grace” he gave to the king was prasād, the food that a Hindu deity gives a devotee; the shaikh’s consecration of the mosque followed a ritual program consistent with the consecration of a Hindu temple; and the shaikh’s patron deity, “Allah,” although not identified with a Hindu deity, was given the generic and hence portable name pradhānpuruṣa, “Great Person.”

Shorn of the fabulous qualities characteristic of all maṅgala-kāvya literature, the Sekaśubhodayā suggests something of how the Islamic frontier and the agrarian frontier converged in the premodern period. Instead of presenting the shaikh as a holy warrior—at no point in the narrative does he engage the Hindus of Pandua in armed combat—the text seeks to connect the diffusion of Islam with the diffusion of agrarian society. In this respect, several elements in the story are crucial: (1) the shaikh’s charismatic authority and organizational ability, (2) the construction of the mosque, (3) state support of the institution, (4) the shaikh’s initiative in settling forested lands transferred to the institution, and (5) the transformation of formerly forested lands into wealth-producing agrarian communities that would continue to support the mosque. In this way, the poem sketches a model of patronage—a mosque linked economically with the hinterland and politically with the state—that was fundamental to the expansion of Muslim agrarian civilization throughout the delta.

In sum, from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries, Bengalis have kept alive memories of charismatic pīrs whose authority rested on three overlapping bases: their connection with the forest, a wild and dangerous domain that they were believed to have subdued; their connection with the supernatural world, a marvelous, powerful realm, with which they were believed to wield continuing influence; and their connection with mosques, which they were believed to have built, thereby institutionalizing the cult of Islam. Whereas the first two bases may or may not have been present in any one pīr, the third was present in nearly all cases, with Shaikh Tabrizi’s mosque at Pandua having established the paradigmatic model.

Moreover, as happened in the case of the sons of Pir ‘Umar Shah of Naokhali, some of these men or their descendants became petty landholders. In cases where religious charisma became transformed into landholding rights, or supplemented such rights, a new class of men emerged—Bengal’s “religious gentry.” Combining piety with land tenure, this class played a decisive role in establishing Islamic institutions in Bengal’s countryside during the Mughal period. Two sorts of data at our disposal reveal the evolution of this class: contemporary Persian records pertaining to land transfers and village surveys of the early twentieth century. The remainder of this chapter will be devoted to examining the latter type of data so far as concerns two districts in the heart of Bengal’s active delta: Bakarganj and Dhaka.

| • | • | • |

The Religious Gentry in Bakarganj and Dhaka, 1650–1760

Known in Mughal times as sarkār Bakla, and in British times as Bakarganj District, the lower Bengali coastal region consisting of the present-day Barisal and Patuakhali districts had long been an economic frontier zone. Lying in the heart of the active portion of the delta, Bakarganj is one of Bengal’s geologically youngest districts. The entire area is composed of an amalgamation of marshlands formed by the merging of islands brought into existence and built up by alluvial soils washed down the great channels of the combined Brahmaputra-Ganges-Meghna river systems. In the early thirteenth century, this forested region became a refuge area for Hindu chieftains dislodged from power in northwestern Bengal. Here they reestablished themselves along the banks of the great rivers and forest islands, far from the reach of Turkish cavalry. But, as J. C. Jack observed in his Settlement Report for the district, “the great rivers which put a limit upon the pursuit of their persecutors put a limit equally upon the size of their kingdoms, which clustered round the banks of the fresh water rivers and were surrounded by impenetrable forests.”[81] At the time of the Mughal conquest, the centers of Hindu civilization were confined to northern and western Bakarganj, while the district’s southern portions remained covered by forests and laced with lagoons, which in time consolidated into marsh. The northwest was also the only part of Bakarganj where the Hindu population exceeded Muslims in early British census records, for as Hindu immigrants pushed into this area, those native groups already inhabiting the region—mainly Chandal fishing tribes—were absorbed into Hindu society as peasant cultivators.[82] Today they constitute the Namasudras, the largest Hindu peasant community in eastern Bengal.

A second great period of economic and social expansion in the Bakarganj forests and marshes occurred in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Now it was Muslim pioneers who assumed the leading role. The emergence of Dhaka as the provincial Mughal capital in the early seventeenth century made the Bakarganj region more accessible to entrepreneurs and developers than at any previous time. But rampant piracy along the coasts and rivers of southeastern Bengal by Arakanese and renegade Portuguese seamen inhibited any sustained attempts by Mughal governors to push into the Bakarganj forests.[83] After 1666, when Mughal naval forces cleared the Meghna estuary of such external threats, the Bakarganj interior lay ripe for colonization. Land developers acquired grants of plots of land, ta‘alluq, from provincial authorities in Dhaka or, after 1704, in Murshidabad.[84] Abundant and easily obtainable by purchase from the late seventeenth century on, these grants tended to be regarded by their possessors, ta‘alluqdārs, as deeds conferring permanent land tenure rights on them.[85] Having brought their ta‘alluqs into agricultural production, these men passed up the land revenue through a class of non-cultivating intermediaries, or zamīndārs. These latter, or their agents, typically resided in the provincial capital, where they had ready access to the chief provincial revenue officer (dīwān) or his staff.

The process of forest clearing and land reclamation in Bakarganj produced complex tenure chains extending from the zamīndār at the upper end down to the actual cultivator at the lower end, with numerous ta‘alluqdārs and sub-ta‘alluqdārs in between. “These talukdars,” wrote Jack, “had usually no intention of undertaking personally the reclamation of their taluks, and pursued in their turn the same system of subletting, but they generally selected as their sub-lesses men who were prepared to take colonies of cultivators to the land.” In other words, the agricultural development boom in Bakarganj afforded wide scope for countless intermediaries who were, in effect, capitalist speculators, or classical revenue farmers. Together, they created a complex subinfeudation structure described by Jack as “the most amazing caricature of an ordered system of land tenure in the world.”[86] In fact, an expandable tenure chain proved an appropriate form of land tenure for an economic frontier that was itself expanding. As Jack himself observed:

This passage hints at the origins of the distinctive land tenure system that emerged in Mughal East Bengal. In order to maintain their claims to social dominance in a region chronically short of resident Brahmans, high-caste Hindus already established in the southern delta encouraged and probably financed the settlement of other high-caste zamīndārs in the region.[88] But such Hindus predominated only at the upper reaches of the tenure chain, for, as Jack noted, social taboos prevented them from undertaking cultivation themselves. On the other hand, those same classes—typically Brahman or Baidya traders and moneylenders—had accumulated sufficient capital to advance loans to sublessees; and these, in turn, hired sublessees below them, and so on, until one reached the mass of cultivators at the bottom of the tenure chain. Whether recruited from amongst indigenous peoples or brought in from the outside, these latter worked as ordinary cultivators on lands newly reclaimed from the jungle.Reclamation of forest was no easy task. It took three or four years to clear the land for regular cultivation during which cultivators and labourers had to be maintained in a country where communications were difficult, rivers dangerous and markets few. Such work was in any case easier when responsibility was divided and it happened that reclamation was taken up when Dacca teemed with men whose occupations were gone. Such men were eager to get rich and unable by caste scruples to cultivate; but their attraction was drawn to colonisation and to Bakarganj by the example of Raja Raj Ballabh and many lesser men who lived in their neighborhood. The owners of the estates who had neither the energy nor the resources to reclaim their forests unaided turned naturally to such men, often their friends or relatives, for assistance.[87]

Crucial in this tenure chain were the Muslim religious gentry who typically occupied its middle ranks as ta‘alluqdārs, situated between the zamīndārs and the cultivators. Described in early British sources as qāẓīs, pīrs, or simply as “Shaikhs,” these men comprised a good part of that class of “Muhammadan adventurers” who, in addition to high-caste Hindu “capitalists,” spearheaded the colonization movement, according to Jack.[89] Men of this class were often credited with the original founding of agricultural settlements in Mughal times. For example, rural surveys made between 1902 and 1913 record that in Barahanuddin Thana of Bakarganj, “This mouza [settlement] has got its name [Kazi Abad] from one Kazi [qāẓī, “judge”] who settled here first.…The population is chiefly Mussalmans.”[90] In Gaurnadi Thana, “the Mahomedans owe their origin directly or indirectly to one Kazi who was one of the original settlers of this village.”[91] Or again: “There are a few families of Mohamedan Kazis who are the original settlers of this village. They were once prosperous. The population is 715, mostly Muslim.”[92] Similarly, in Narayanganj Thana of Dhaka District, the all-Muslim village of Kutubpur derived its name from a saint named Pir Qutb, who, we are told, settled in this area “when there was no basti,” or crude homesteads, in the area.[93]

There were two patterns by which such men became established as members of the rural landscape’s religious gentry. Most often, they acquired ta‘alluqs from some higher authority, either a local chieftain or a revenue contractor in the provincial capital, and then went out into the forest or marshlands to organize the clearing and settling of the land. Speculators who agreed to pay the Mughal revenue demand hoped to make a profit by subcontracting the work of reclamation to sublessees. These latter established themselves as de facto landlords over whole regions, which eventually coalesced into settled communities. We see this happening in the following record concerning the establishment of a Muslim settlement named Mithapur in Patuakhali, deep in the Sundarbans forest. In the eighteenth century a certain Shaikh Ghazi

Here was the classic pattern of subinfeudation in the forests of eighteenth-century Bakarganj: an absentee Hindu acquired zamīndārī rights from the Mughal governor, permitting him to extract as much wealth as he could from a given ta‘alluq so long as he remitted a stipulated amount to the government as land revenue. The zamīndār then contracted with some enterprising middleman, typically a member of the Muslim petty religious establishment, to undertake the arduous tasks of organizing the clearing of the jungles and preparing the land for rice cultivation. In such cases the reclamation process often bridged communal lines. In the instance cited above, it was the Hindu Janaki Ballav Roy who had the contacts with the governor and who settled with the latter’s revenue officials on a tax payment. At that point Roy withdrew from the work of reclamation, getting “material assistance” from a Muslim whose name, Shaikh Ghazi, suggests religious charisma and who actually settled in Mithapur to organize forest-clearing operations.befriended himself with Janaki Ballav Roy immediately after he [Roy] got the Zamindari of Arangapur from the Nawab [i.e., governor]. Janaki Ballav also got material assistance from this man in the work of reclamation of lands from Sundarbans [i.e., forest]. Shekh Gazi subsequently settled in Mithapur.[94]

Thus, contrary to J. C. Jack’s picture of two distinct classes of developers—Hindu “capitalists” and Muslim “adventurers”—moving separately into the forests of Bakarganj, it appears that the two types moved in tandem with each other, although at different ends of the land tenure chain. Influential urban Hindus supplied the cash, or at least the commitment to pay the revenue to the government; and enterprising Muslims supplied the organizational ability and charisma to mobilize labor forces on the ground. This pattern of collaboration contributed to the characteristic configuration of land tenure in much of pre–1947 East Bengal, where high-caste Hindus, typically absentee zamīndārs, emerged at the upper end of the tenure chain, and Muslim cultivators at the lower end.

In a second pattern of land development, Muslim pīrs or qāẓīs went directly into uncultivated regions, organized the local population for clearing the jungles, and only later, after having established themselves as local men of influence, entered into relations with the Mughal authorities. In such instances the government endeavored to appropriate men of local influence by designating them petty collectors. In southern Dhaka District, the settlement of Panam Dulalpur emerged in the early eighteenth century around a pīr named Hazrat Daner Mau. Early in the history of this settlement, the inhabitants had given this pīr regular donations of nażr, or charitable gifts of money, “out of reverence for the good and popular religious man.” Later, this charitable gift crystallized into fixed amounts from each tenant in the village. Some inhabitants—we do not know who—refused payment and took the matter to the authorities in Murshidabad, but the latter declined to consider the case.

Hazrat Daner Mau’s transition from holy man to landholder was thus linked to the intervention of state power. With its hearty appetite for land revenue, the government sought to capture and transform into revenue-paying officials whatever local notables appeared on the horizon. In the above-cited case, the government exploited the refusal by some villagers to pay a charitable fee by establishing a fixed villagewide figure to be owed the pīr; it then redefined that fee as land tax, and the pīr as the revenue-paying landholder.The people of Panam were thus obliged to come to an agreement with the Pir who agreed to receive a fixed amount annually from the inhabitants of the entire mauza. This amount was 118 siccas [rupees].…This became the fixed rent of the entire mauza of Panam Dulalpur, and the Pir whose name was Hazrat Daner Mau, became the landowner of the Mouzah and thus obtained the sanction of the Nawab of Murshidabad.[95]

Where pīrs themselves did not become defined as zamīndārs, their sons and descendants often did, as was the case with the sons of Pir ‘Umar Shah of Noakhali, discussed above.[96] But the relationship between the religious gentry and Mughal authorities was not always happy, since a pīr’s natural ties of authority and patronage generally lay with the masses of peasants beneath him and not with the governors and bureaucrats in distant Dhaka or, after 1704, Murshidabad. For example, in remote Jhalakati Thana in the Bakarganj Sundarbans, an eighteenth-century pīr named Saiyid Faqir wielded enormous influence with the cultivators of the all-Muslim village of Saiyidpur, named after the pīr. But a difficulty arose, noted a 1906 village survey, because “the people of this part looked upon the Fakir as their guide and did not pay rent to the Nawab.” In this situation, one Lala Chet Singh, a captain in the employ of the governor, “succeeded in persuading the Fakir to leave the country.” Though we do not know how the officer managed to dislodge the pīr from the village, he was evidently successful, since the authorities in Murshidabad rewarded him for his efforts by giving him the right to collect the pargana’s revenue.[97] This suggests that on the politically fluid Bengal frontier, the peasants’ loyalty did not necessarily extend beyond their local holy man. From the government’s perspective, while it was always preferable when possible to coopt influential holy men, the Mughals did not hesitate, when necessary, to impose their own revenue machinery on rural settlements.

In the early twentieth century, the Muslim cultivators of eastern Bengal were described as an industrious, unruly, and socially unstratified population, with few loyalties beyond those given their pīrs. The population of one settlement in Bakarganj’s Swarupkati Thana, we read, consisted entirely of Muslims, who were “rather fierce. They played a conspicuous role in the history of the pargana. They were the first men who rallied around…[illegible]…when he created the taluk after the transfer of his zamindari.”[98] Concerning a settlement in Bakarganj’s Jhalakati Thana, we find the following account, recorded in 1906:

Refractory or unruly as they may have appeared to law-and-order-minded British officials, these men—or, more correctly, their ancestors—were in fact the primary agents of the extension of agriculture in much of eastern Bengal. As one officer remarked in 1902 concerning another Bakarganj village, “The population are almost all Mohammedans, who have been trying their best to bring the waste lands into cultivation. In fact, the jungles have now been mainly cleared.”[100] Or again: “There are a good many petty tenures in this mauza [settlement], all of which have been created for bringing the lands under cultivation. The population are Muhammadan.”[101]The village is now inhabited by Mohammedans. Formerly there were several families of Nama Sudras in the village, but for the oppression of the Mahommedans they were compelled to leave the village. Their lands and homesteads are now in possession of the Mahommedans. The people of the village are all very refractory and riotous. On slight provocation they can easily take the life of another. Criminal breach of peace is a daily occurrence here. The people are so irreligious that to take revenge from a man they never hesitate to bring false criminal case against a man. The river dacoits [bandits] of Bish Khali river are none others than the inhabitants of this village and of neighboring other villages, too.[99]

| • | • | • |

Summary

Bengali literary and folk traditions dating from the sixteenth century are replete with heroes associated with taming the forest, extending the cultivable area, and instituting new religious cults. Typically, these heroes combined holy man piety with the organizational skills necessary for forest clearing and land reclamation; hence they were remembered not only for establishing mosques and shrines but also for mobilizing communities to cut the forests and settle the land. As this happened, people gradually came to venerate these men, who were usually Muslims. In the active delta, then, Islam was introduced as a civilization-building ideology associated both with settling and populating the land and with constructing a transcendent reality consonant with that process.

Enormously important environmental changes lay behind these developments. The main factors contributing to the emergence of new peasant communities in eastern Bengal—colonization, incorporation, and natural population growth—were all related to the shift of the active portion of the delta from the west to the east. First, this shift stimulated colonization of the active delta by migrants coming from the relatively less fertile upper delta or West Bengal, or even from North India and beyond. Second, as this happened, indigenous communities of fishermen and shifting cultivators became incorporated into sedentary communities that focused on the charisma and the organizational abilities of Muslim pioneers. And third, the shift of the delta’s active portion to the south and east contributed to natural population growth, since the initiation or intensification of wet rice cultivation in this region dramatically increased local food supplies. Although East Bengal’s growing fertility was too gradual to be noticed by contemporary observers, it is nonetheless witnessed in revenue demand statistics for the late sixteenth and mid seventeenth centuries, as well as in popular traditions that celebrated the leadership and labors of forest pioneers. The growth of a Muslim peasant society, such a striking development in the post-sixteenth-century eastern delta, thus appears to have been related to larger ecological and demographic forces.

Finally, the cultural and ecological-demographic changes of the post-sixteenth-century period must be seen in the context of the new political environment that accompanied these changes—namely, the advent of Mughal authority in the delta. By a coincidence of some note, the Ganges River completed its eastward shift into the Padma system at the very time—the late sixteenth century—when Mughal power was becoming consolidated in the region. In a sense, then, Mughal authority rode the back of the eastward-moving ecological movement, symbolized by the establishment of the Mughals’ provincial capital in the heart of the active delta. To explore the impact of this new political atmosphere on cultural changes taking place in the region, we may examine contemporary Mughal documents concerning agrarian expansion and religious patronage. Fortunately, extensive Persian documentation of this kind has survived for critical sectors of the delta; it is to these that we turn our attention.

Notes

1. See R. K. Mukerjee, The Changing Face of Bengal: A Study of Riverine Economy (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1938), 3–10; S. C. Majumdar, Rivers of the Bengal Delta (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1942), 65–72; W. H. Arden Wood, “Rivers and Man in the Indus-Ganges Alluvial Plain,” Scottish Geographical Magazine 40, no. 1 (1924): 9–10; C. Strickland, Deltaic Formation, with Special Reference to the Hydrographic Processes of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra (Calcutta: Longmans, Green, 1940), 104; Kanangopal Bagchi, The Ganges Delta (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1944), 33. Geographers and geologists have not agreed on the fundamental cause of Bengal’s riverine dynamics. Whereas geographers generally see sedimentation as the driving force behind riverine movement, geologists have pointed to tectonic activity that has produced a torsion in the crust of East Bengal. According to this view, torsion caused the uplift of the Barind in northern Bengal and the subsidence of the Sylhet Basin, which in turn produced a major fault line passing south by southeast from eastern Rangpur to eastern Barisal, into which Bengal’s major rivers have tended to gravitate. See J. Fergusson, “Delta of the Ganges,” Journal of the Geological Society of London 19 (1863): 321–54; F. C. Hirst, Report on the Nadia Rivers, 1915 (Calcutta, 1916); and James P. Morgan and William G. McIntire, “Quaternary Geology of the Bengal Basin, East Pakistan and India,” Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 70 (March 1959): 319–42.

2. Bagchi, Ganges Delta, 58. See also N. D. Bhattacharya, “Changing Course of the Padma and Human Settlements,” National Geographic Journal of India 24, nos. 1 and 2 (March-June 1978): 63–65.

3. Mukerjee, Changing Face, 137.

4. Federici, “Extracts,” 113. As he wrote, “the River is very shallow, and little water.”

5. Abu’l-fazl ‘Allami, Akbar-nāma, trans., 3: 153; text, 3: 109.

6. Jean Baptice Tavernier, Travels in India, ed. V. Ball (London: Macmillan, 1889; reprint, Lahore: Al-Biruni, 1976), 1: 125.

7. In the British period the movement of prosperity and population from northwest to southeast was observed to occur even within districts. Thus between 1881 and 1911 the population of northern Faridpur increased by 7 percent while that of southeastern Faridpur increased by 50 percent. “The stagnation of the north,” it was noted in the Faridpur settlement report, “is clearly due to the drying up of the rivers and streams which has made the soil less fertile, the transport of produce more difficult and the climate more unhealthy. During the cold weather the rivers become a chain of dirty pools; there are few tanks and no good drinking water. Epidemics of cholera are very frequent and other diseases take toll of the population; malaria is constant everywhere and the people generally have a very low degree of vitality.” J. C. Jack, Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operations in the Faridpur District, 1904 to 1914 (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, 1916), 7.

8. Subrahmanyam, “Notes,” 268.

9. Federici, “Extracts,” 137.

10. Ibid., 185.

11. François Pyrard, The Voyage of François Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil, ed. and trans. Albert Gray (Hakluyt Society, 1st ser., nos. 76, 77, 80, 1887–90; reprint, New York: Burt Franklin, n.d.), 2: 327.

12. S. Arasaratnam, “The Rice Trade in Eastern India, 1650–1740,” Modern Asian Studies 22, no. 3 (1988): 531–49.

13. Manrique, Travels, 1: 56. In 1665 François Bernier noted that Bengal “produces rice in such abundance that it supplies not only the neighboring but remote states. It is carried up the Ganges as far as Patna, and exported by sea to Maslipatam and many other ports on the coast of Koromandel. It is also sent to foreign kingdoms, principally to the island of Ceylon and the Maldives.” Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656–68, trans. Archibald Constable, 2d ed. (New Delhi: S. Chand & Co., 1968), 437.

14. Manrique, Travels, 1: 54.

15. Om Prakash, The Dutch East India Company and the Economy of Bengal, 1630–1720 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 224–29.

16. Orme, Military Transactions, 2: 4.

17. For the geographical distribution of Bengal’s textile indutry, see the maps in K. N. Chaudhuri, The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660–1760 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 248; and Irfan Habib, An Atlas of the Mughal Empire (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1982), map 11B.

18. Ralph Fitch, “The Voyage of Master Ralph Fitch Merchant of London to Ormus, and so to Goa in the East India, to Cambaia, Ganges, Bengala,” in Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes (1625; Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons, 1905), 10: 184.

19. Henry Yule and A. C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, 2d ed., ed. William Crooke (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1968), 290.

20. As Manrique noted in 1640, “Most of the cloth is made of cotton and manufactured with a delicacy and propriety not met with elsewhere. The finest and richest muslins are produced in this country, from 50 to 60 yards long and 7 to 8 handbreadths wide, with borders of gold and silver or coloured silks. So fine, indeed, are these muslins that merchants place them in hollow bamboos, about two spans long, and thus secured, carry them throughout Carazane [Khurasan], Persia, Turkey, and many other countries.” Manrique, Travels, 1: 56–57.

21. In 1655, for example, Indian merchants from Agra bought up six thousand bales at Cossimbazar for export to the imperial court, a quantity twice the size of the Dutch purchase two years later. Generale missiven, 2: 795; 3:101.

22. See pp. 96–97.

23. See Subrahmanyam, “Notes,” 265–89.

24. Sushil Chaudhury, Trade and Commercial Organization in Bengal, 1650–1720 (Calcutta: Firma K. L.M., 1975), 178–79. In 1652 Dutch East India Company officials wrote that raw silk was so abundant in Bengal that in Cossimbazar alone they could invest ten tons of gold in that commodity, noting that local merchants would accept only silver or gold for such purchases. Generale missiven, 2: 622.

25. Prakash, Dutch East India Company, 75. Raw silk and cotton textiles, followed by saltpetre and opium, were the principal commodities exported from Bengal by the Dutch. Silk comprised nearly 40 percent of Dutch exports in 1675–76, and 29 percent between 1701 and 1703. In the same periods Bengali textiles comprised 22 and 54 percent respectively. Ibid., 72.

26. Sushil Chaudhury, “The Asian Merchants and Companies in Bengal’s Export Trade, circa mid-Eighteenth Century” (paper presented at the International Conference on “Merchants, Companies, and Trade” held at the Maison des Sciences de l’homme, Paris, May 30-June 2, 1990). See also Sushil Chaudhury, Pre-Modern Industries and Maritime Trade in South Asia: Bengal in the First Half of theEighteenth Century, chs. 7 and 8 (forthcoming).

27. Subrahmanyam, “Notes,” 269.

28. Ibid., 279. Between 1626 and 1635 imperial mints in Bengal (including Patna) turned out an estimated annual average of 85.76 metric tons of silver coinage, a figure surpassing the output of the imperial mints of Gujarat, of the Northwest (Lahore, Multan, Thatta, Kabul, Qandahar), and of the central provinces. Shireen Moosvi, The Economy of the Mughal Empire, c. 1595: A Statistical Study (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1987), 357–61. As this was a period after the decline of Portuguese commerce in Bengal, and before the advent of the Dutch or English there, a good part of this silver probably accompanied the influx of Mughal men and arms into the new frontier province.

29. Prakash, Dutch East India Company, 249.

30. Om Prakash, “Bullion for Goods: International Trade and the Economy of Early Eighteenth Century Bengal,” Indian Economic and Social History Review 13, no. 2 (April-June 1976): 162–63.

31. Chaudhury, Trade and Commercial Organization, 100–125.

32. “Till of late years,” wrote the Englishman Luke Scrafton in 1760, “inconceivable numbers of merchants from all parts of Asia in general, as well as from the rest of Hindostan in particular, sometimes in bodies of many thousands at a time, were used annually to resort to Bengal with little else than ready money or bills to purchase the produce of these provinces.” Scrafton, Reflections on the Government of Indostan (London, 1760), 20. Cited in Sushil Chaudhury, “The Asian Merchants and Companies in Bengal’s Export Trade,” 18.

33. See Earl J. Hamilton, American Treasure and Price Revolution in Spain, 1501–1652 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1934; reprint, New York: Octagon Books, 1965), 283–306.

34. Aziza Hasan, “The Silver Currency Output of the Mughal Empire and Prices in India during the 16th and 17th Centuries,” Indian Economic and Social History Review 6, no. 1 (March 1969): 85–116.

35. In Gujarat during the first third of the seventeenth century, the price of both indigo and sugar rose with the money supply, as did that of grain in North India between 1595 and 1669. Ibid., 104–10.

36. According to Dutch records, between 1657 and 1713, a period that saw a dramatic influx of silver in Bengal, the prices of basic commodities such as rice, wheat, clarified butter, and sugar did show fluctuations, but no consistent pattern of inflation. For example, in 1658, the earliest date for which there are data, a hundred maunds of rice cost Rs. 49, whereas in 1717 the same amount cost Rs. 48. Prakash, Dutch East India Company, 251–53.

37. In 1659, provincial land revenue demand (jama‘) in round figures stood at Rs. 10.3 million, but from 1700 on this figure was gradually increased each year, reaching Rs. 14.2 million in 1722. Of this, Rs. 10.9 million was intended for the central treasury in Delhi (khāliṣa), and Rs. 3.3 million for maintenance of local officials in the province (jāgīr). See Dastūr-i ‘amal-i ‘ālamgīrī (British Library MS., Add. 6599), fols. 120a–121a; Fifth Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Affairs of the East India Company, dated 28 July, 1812, ed. Walter K. Firminger (Calcutta: R. Cambray & Co., 1917), 2: 189–91. The annual enhancements made between 1700 and 1721 were the work of the provincial governor Murshid Quli Khan and are found in Appendix No. 6 to John Shore’s “Minute on the Rights and Privileges of Zamindars” (West Bengal Government Archives, Calcutta, Board of Revenue Proceedings for April 2, 1788, vol. 127), 539–40. Cited in Philip B. Calkins, “Revenue Administration and the Formation of a Regionally Oriented Ruling Group in Bengal, 1700–1740” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1972), 146.