3. Early Sufis of the Delta

In the country of Bengal, not to speak of the cities, there is no town and no village where holy saints did not come and settle down.

| • | • | • |

The Question of Sufis and Frontier Warfare

Bengal’s earliest sustained contact with Islamic civilization occurred in the context of the geopolitical convulsions that had driven large numbers of Turkish-speaking groups from Central Asia into the Iranian plateau and India. Whether as military slaves, as adventurers, or as refugees fleeing before the Mongol advance, Turks gravitated not only to the older centers of the Islamic world—Baghdad, Cairo, Samarkand—but also to its fringes, including Bengal. Immigrant groups were often led by a man called alp or alp-eren, identified as “the heroic figure of old Turkic saga, the warrior-adventurer whose exploits alone justified his way of life.”[1] Migrating Turks also grouped themselves into Islamic mystical fraternities typically organized around Sufi leaders who combined the characteristics of the “heroic figure of old Turkic saga,” the alp, and the pre-Islamic Turkish shaman—that is, a charismatic holy man believed to possess magical powers and to have intimate contact with the unseen world. It happened, moreover, that the strict authority structure that had evolved for transmitting Islamic mystical knowledge from master (murshid) to disciple (murīd) proved remarkably well suited for binding retainers to charismatic leaders. This, too, lent force to the Turkish drive to the Bengal frontier.

The earliest-known Muslim inscription in Bengal concerns a group of such immigrant Sufis. Written on a stone tablet found in Birbhum District and dated July 29, 1221, just seventeen years after Muhammad Bakhtiyar’s conquest, the inscription records the construction of a Sufi lodge (khānaqāh) by a man described as a faqīr—that is, a Sufi—and the son of a native of Maragha in northwestern Iran. The building was not meant for this faqīr alone, but for a group of Sufis (ahl-i ṣuffa) “who all the while abide in the presence of the Exalted Allah and occupy themselves in the remembrance of the Exalted Allah.”[2] The tablet appears to have been part of a pre-Islamic edifice before it was put to use for the khānaqāh, for on its reverse side is a Sanskrit inscription mentioning the victorious conquests made in this part of the delta by a subordinate of Nayapala, Pala king from ca. A.D. 1035 to 1050. The inscription refers to a large number of Hindu temples in this region, and, despite the Buddhist orientation of the Pala kings, it identifies this subordinate ruler as a devotee of Brahmanic gods.[3] Thus the two sides of the same tablet speak suggestively of the complex cultural history of this part of the delta: Brahmanism had flourished and was even patronized by a state whose official cult was Buddhism; on the other hand, the earliest-known representatives of Islam in this area appear to us in the context of the demolished ruins of Bengal’s pre-Muslim past.

But were these men themselves temple-destroying iconoclasts? Can we think of them as ghāzīs—that is, men who waged religious war against non-Muslims? Such, indeed, is the perspective of much Orientalist scholarship. In the 1930s the German Orientalist Paul Wittek propounded the thesis that the Turkish drive westward across Anatolia at the expense of Byzantine Greek civilization had been propelled by an ethos of Islamic holy war, or jihād, against infidels. Although this thesis subsequently became established in Middle Eastern historiography, recent scholarship has shown that it suffers from lack of contemporary evidence.[4] Instead, as Rudi Lindner has argued, the association of a holy war ethic with the early rise of Ottoman power was the work of ideologues writing several centuries after the events they described. What they wrote, according to Lindner, amounted to an “ex post facto purification of early Ottoman deeds, [speaking] more of later propaganda than of early history.”[5]

A similar historiographical pattern is found in Bengal. While it is true that Persian biographies often depict early Sufi holy men of Bengal as pious warriors waging war against the infidel, such biographies were not contemporary with those Sufis. Take, for example, the case of Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi (d. 1244–45), one of the earliest-known Sufis of Bengal. The earliest notice of him appears in the Siyar al-‘ārifīn, a compendium of Sufi biographies compiled around 1530–36, three centuries after the shaikh’s lifetime. According to this account, after initially studying Sufism in his native Tabriz (in northwestern Iran), Jalal al-Din Tabrizi left around 1228 for Baghdad, where he studied for seven years with the renowned mystic Shaikh Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi. When the latter died in 1235, Jalal al-Din Tabrizi traveled to India and, not finding a warm welcome in the court of Delhi, eventually moved on to Lakhnauti, then the remote provincial capital of Bengal. There he remained until his death ten years later.[6] “When he went to Bengal,” the account records,

Since no contemporary evidence shows that he or any other Sufi in Bengal actually indulged in the destruction of temples, it is probable that as with Turkish Sufis in contemporary Anatolia, later biographers reworked Jalal al-Din Tabrizi’s career for the purpose of expressing their own vision of how the past ought to have happened. For such biographers, the shaikh’s alleged destruction of a Hindu temple, his conversion of the local population, and his raising a Sufi hospice on the temple site all defined for later generations his imagined role as one who had made a decisive break between Bengal’s Hindu past and its Muslim future.all the population there came to him and became his disciples. There he built a hospice and a public kitchen, and bought several gardens and lands as an endowment for the kitchen. These increased. There was also there a (river) port called Deva Mahal, where an infidel had built a temple at great cost. The shaikh destroyed that temple and in its place constructed a (Sufi) rest-house [takya]. There, he made many infidels into Muslims. Today [i.e., 1530–36], his holy tomb is located at the very site of that temple, and half the income of that port is dedicated to the upkeep of the public kitchen there.[7]

Much the same hagiographical reconstruction was given the career of Shah Jalal Mujarrad (d. 1346), Bengal’s best-known Muslim saint. His biography was first recorded in the mid sixteenth century by a certain Shaikh ‘Ali (d. ca. 1562), a descendant of one of Shah Jalal’s companions. Once again we note a gap of several centuries between the life of the saint and that of his earliest biographer. According to this account, Shah Jalal had been born in Turkestan, where he became a spiritual disciple of Saiyid Ahmad Yasawi, one of the founders of the Central Asian Sufi tradition.[8] The account then casts the shaikh’s expedition to India in the framework of holy war, mentioning both his (lesser) war against the infidel and his (greater) war against the lower self. “One day,” the biographer recorded, Shah Jalal

It is true that the notion of two “strivings” (jihād)—one against the unbeliever and the other against one’s lower soul—had been current in the Perso-Islamic world for several centuries before Shah Jalal’s lifetime.[10] But a fuller reading of the text suggests other motives for the shaikh’s journey to Bengal. After reaching the Indian subcontinent, he and his band of followers are said to have drifted to Sylhet, on the easternmost edge of the Bengal delta. “In these far-flung campaigns,” the narrative continued, “they had no means of subsistence, except the booty, but they lived in splendour. Whenever any valley or cattle were acquired, they were charged with the responsibility of propagation and teaching of Islam. In short, [Shah Jalal] reached Sirhat (Sylhet), one of the areas of the province of Bengal, with 313 persons. [After defeating the ruler of the area] all the region fell into the hands of the conquerors of the spiritual and the material worlds. Shaikh [Jalal] Mujarrad, making a portion for everybody, made it their allowance and permitted them to get married.”[11]represented to his bright-souled pīr [i.e., Ahmad Yasawi] that his ambition was that just as with the guidance of the master he had achieved a certain amount of success in the Higher (spiritual) jihād, similarly with the help of his object-fulfilling courage he should achieve the desire of his heart in the Lesser (material) jihād, and wherever there may be a Dār-ul-ḥarb [i.e., Land of non-Islam], in attempting its conquest he may attain the rank of a ghāzī or a shahīd [martyr]. The revered pīr accepted his request and sent 700 of his senior fortunate disciples…along with him. Wherever they had a fight with the enemies, they unfurled the banner of victory.[9]

Written so long after the events it describes, this account has a certain paradigmatic quality. Like Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi, Shah Jalal is presented as having brought about a break between Bengal’s Hindu past and its Muslim future, and to this end a parallel is drawn between the career of the saint and that of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad. The number of companions said to have accompanied Shah Jalal to Bengal, 313, corresponds precisely to the number of companions who are thought to have accompanied the Prophet Muhammad at the Battle of Badr in A.D. 624, the first major battle in Muhammad’s career and a crucial event in launching Islam as a world religion. The story thus has an obvious ideological drive to it.

But other aspects of the narrative are more suggestive of Bengal’s social atmosphere at the time of the conquest. References to “far-flung campaigns” where Shah Jalal’s warrior-disciples “had no means of subsistence, except the booty” suggest the truly nomadic base of these Turkish freebooters, and, incidentally, refute the claim (made in the same narrative) that Shah Jalal’s principal motive for coming to Bengal was religious in nature. In fact, reference to his having made “a portion for everybody” suggests the sort of behavior befitting a tribal chieftain vis-à-vis his pastoral retainers, while the reference to his permitting them to marry suggests a process by which mobile bands of unmarried nomads—Shah Jalal’s own title mujarrad means “bachelor”—settled down as propertied groups rooted in local society. Moreover, the Persian text records that Shah Jalal had ordered his followers to become kadkhudā, a word that can mean either “householder” or “landlord.”[12] Not having brought wives and families with them, his companions evidently married local women and, settling on the land, gradually became integrated with local society. All of this paralleled the early Ottoman experience. At the same time that Shah Jalal’s nomadic followers were settling down in eastern Bengal, companions of Osman (d. 1326), the founder of the Ottoman dynasty, were also passing from a pastoral to a sedentary life in northwestern Anatolia.[13]

Fortunately, we are in a position to compare the later, hagiographic account of Shah Jalal’s career with two independent non-hagiographic sources. The first is an inscription from Sylhet town, dated 1512–13, from which we learn that it was a certain Sikandar Khan Ghazi, and not the shaikh, who had actually conquered the town, and that this occurred in the year 1303–4.[14] The second is a contemporary account from the pen of the famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta (d. 1377), who personally met Shah Jalal in 1345. The shaikh was quite an old man by then and sufficiently renowned throughout the Muslim world that the great world traveler made a considerable detour—he had been sailing from South India to China—in order to visit him. Traveling by boat up the Meghna and Surma rivers, Ibn Battuta spent three days as Shah Jalal’s guest in his mountain cave near Sylhet town. As the Moroccan later recalled,

One would like to know more about the religious culture of these people prior to their conversion to Islam. The fragmentary evidence of Ibn Battuta’s account suggests that they were indigenous peoples who had had little formal contact with literate representatives of Brahmanism or Buddhism, for the Moroccan visitor elsewhere describes the inhabitants of the East Bengal hills as “noted for their devotion to and practice of magic and witchcraft.”[16] The remark seems to distinguish these people from the agrarian society of the Surma plains below the hills of Sylhet, a society Ibn Battuta unambiguously identifies as Hindu.[17] It is thus possible that in Shah Jalal these hill people had their first intense exposure to a formal, literate religious tradition.This shaikh was one of the great saints and one of the unique personalities. He had to his credit miracles (karāmat) well known to the public as well as great deeds, and he was a man of hoary age.…The inhabitants of these mountains had embraced Islam at his hands, and for this reason he stayed amidst them.[15]

In sum, the more contemporary evidence of Sufis on Bengal’s political frontier portrays men who had entered the delta not as holy warriors but as pious mystics or freebooting settlers operating under the authority of charismatic leaders. No contemporary source endows them with the ideology of holy war; nor is there contemporary evidence that they slew non-Muslims or destroyed non-Muslim monuments. No Sufi of Bengal—and for that matter no Bengali sultan, whether in inscriptions or on coins—is known to have styled himself ghāzī. Such ideas only appear in hagiographical accounts written several centuries after the conquest. In particular, it seems that biographers and hagiographers of the sixteenth century consciously (or perhaps unconsciously) projected backward in time an ideology of conquest and conversion that had become prevalent in their own day. As part of that process, they refashioned the careers of holy men of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries so as to fit within the framework of that ideology.

| • | • | • |

Bengali Sufis and Hindu Thought

From the beginning of the Indo-Turkish encounter with Bengal, one section of Muslims sought to integrate into their religious lives elements of the esoteric practices of local yogis, together with the cosmologies that underpinned those practices. Contemporary Muslims perceived northern Bengal generally, and especially Kamrup, lying between the Brahmaputra River and the hills of Bhutan, as a fabulous and mysterious place inhabited by expert practitioners of the occult, of yoga, and of magic. During his visit to Sylhet, Ibn Battuta noted that “the inhabitants of these mountains . are noted for their devotion to and practice of magic and witchcraft.”[18] Around 1595 the great Mughal administrative manual ā’īn-i Akbarī described the inhabitants of Kamrup as “addicted to the practice of magic [jādūgarī].”[19] Some twenty-five years later a Mughal officer serving in northern Bengal described the Khuntaghat region, in western Kamrup, as “notorious for magic and sorcery.”[20] And in 1662–63 another Mughal chronicler, referring to the entire Assam region, of which Kamrup is the western part, remarked that “the people of India have come to look upon the Assamese as sorcerers, and use the word ‘Assam’ in such formulas as dispel witchcraft.”[21]

Since Sufis were especially concerned with apprehending transcendent reality unmediated by priests or other worldly institutions, it is not surprising that they, among Muslims, were most attracted to the yogi traditions of Kamrup. Within the very first decade of the Turkish conquest, there began to circulate in the delta Persian and Arabic translations of a Sanskrit manual on tantric yoga entitled Amṛtakuṇḍa (“The Pool of Nectar”). According to the translated versions, the Sanskrit text had been composed by a Brahman yogi of Kamrup who had converted to Islam and presented the work to the chief qāẓī, or judge, of Lakhnauti, Rukn al-Din Samarqandi (d. 1218). The latter, in turn, is said to have made the first translations of the work into Arabic and Persian.[22] While this last point is uncertain, there is no doubt that for the following five hundred years the Amṛtakuṇḍa, through its repeated translations into Arabic and Persian, circulated widely among Sufis of Bengal, and even throughout India.[23] The North Indian Sufi Shaikh ‘Abd al-Quddus Gangohi (d. 1537) is known to have absorbed the yogic ideas of the Amṛtakuṇḍa and to have taught them to his own disciples.[24] In the mid seventeenth century, the Kashmiri author Muhsin Fani recorded that he had seen a Persian translation of the Amṛtakuṇḍa,[25] and in the same century the Anatolian Sufi scholar Muhammad al-Misri (d. 1694) cited the Amṛtakuṇḍa as an important book for the study of yogic practices, noting that in India such practices had become partly integrated with Sufism.[26]

In both its Persian and Arabic translations, the Amṛtakuṇḍa survives as a manual of tantric yoga, with the first of its ten chapters affirming the characteristically tantric correspondence between parts of the human body and parts of the macrocosm, “where all that is large in the world discovers itself in the small.” In the mid sixteenth century, there appeared in Gujarat a Persian recension of the Amṛtakuṇḍa under the title Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ, attributed to the great Shattari shaikh Muhammad Ghauth of Gwalior (d. 1563).[27] A prologue to this version, written by a disciple of the shaikh, records how these yogic ideas were thought to have entered the Bengali Sufi tradition:

The exchange between the yogi and the qāẓī cited here appears to have been modeled on a passage in the Qur’an (17:85), in which God tells the Prophet Muhammad: “They [the Jews] will ask thee concerning the Spirit. Say: the Spirit is by command of my Lord.” By putting into the mouth of a yogi words that in the Qur’an were those of the Jews of Muhammad’s day, the author of this recension apparently intended to make the yogi’s exchange comprehensible to a Muslim audience.This wonderful and strange book is named Amṛtakuṇḍa in the Indian language [i.e., Sanskrit]. This means “Water of Life,” and the reason for the appearance of this book among the Muslims is as follows. When Sultan ‘Ala al-Din [i.e., ‘Ali Mardan] conquered Bengal and Islam became manifest there, news of these events reached the ears of a certain gentleman of the esteemed learned class in Kamrup. His name was Kama, and he was a master of the science of yoga.

In order to debate with the Muslim ‘ulamā [scholars] he arrived in the city of Lakhnauti, and on a Friday he entered the Congregational Mosque. A number of Muslims showed him to a group of ‘ulamā, and they in turn pointed him to the assembly of Qazi Rukn al-Din Samarqandi. So he went to this group and asked: “Whom do you worship?” They replied, “We worship the Faultless God.” To his question “Who is your leader?” they replied, “Muhammad, the Messenger of Allah.” He said, “What has your leader said about the Spirit [rūḥ]?” They replied, “God the All-nourishing has commanded (that there be) the Spirit.” He said, “In truth, I too have found this same thing in books that are subtle and committed to memory.”

Then that man converted to Islam and busied himself in acquiring religious knowledge, and he soon thereafter became a scholar (muftī). After that he wrote and presented this book to Qazi Rukn al-Din Tamami [Samarqandi]. The latter translated it from the Indian language into Arabic in a book of thirty chapters, and somebody else translated it into Persian in a book of ten chapters.…And when Hazrat Ghauth al-Din himself went to Kamrup he necessarily spent several years in studying this science.…The name of this book is Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ.[28]

A second prologue to the Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ established a framework within which a text on yoga could be accommodated within the rich body of classical Sufi lore. In it, the translator tells of once being in a country whose king summoned him and ordered that he undertake a great journey to a distant but fabulous realm. The king reminded the traveler that they were joined together by a covenant and that they would meet again at the end of the traveler’s voyage. Then the translator/traveler describes the hardships he endured while on his journey: the two seas (the soul and nature), the seven mountains, the four passes, the three stations filled with dangers, and the path narrower than the eye of an ant. Ultimately, he reached the promised land, where he found a shaikh who mirrored or echoed each of his own moves and words. Realizing that the man was but his own reflection, the traveler remembered his covenant with his master, to whom he was now led. The story’s climax is reached in the traveler’s epiphanic self-discovery: “I found the king and minister in myself.”[29] The dominant motifs of this second prologue—the traveler, the arduous path with its temptations and dangers, and the ultimate realization that the goal is identified with the seeker—all show the influence of Sufi notions current in the thirteenth-century Perso-Islamic world.[30] The placement of the yogic text immediately after this prologue suggests that the esoteric practices described therein constitute, in effect, the means to achieving the mystical goals stated in the second prologue.

Although some scholars have regarded the Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ as a work of religious syncretism, this judgment is difficult to sustain if by syncretism one means the production of a new synthesis out of two or more antithetical elements.[31] Rather, the work consists of two independent and self-contained worldviews placed alongside one another—a technical manual of yoga preceded by a Sufi allegory—with later editors or translators going to some lengths to stress their points of coincidence. Although Islamic terms and superhuman agencies are generously sprinkled through the main text, allusions to Islamic lore serve ultimately to buttress or illustrate thoroughly Indian concepts.[32] Here, at least, yoga and Sufi ideas resisted true fusion.

Nonetheless the book’s popularity illustrates the Sufis’ considerable fascination with the esoteric practices of Bengal’s indigenous culture. The renowned Shattari saint Shaikh Muhammad Ghauth even traveled from Gwalior in Upper India to Kamrup in order to study the esoteric knowledge that Muslims had identified with that region. In doing so he was following a tradition of Sufis of the Shattari order, whose founder, Shah ‘Abd Allah Shattari (d. 1485), included Bengal on his journey from Central Asia through India.[33] Although one cannot establish a continuous intellectual tradition between Bengali Muslims of the thirteenth century and the Shattari Sufis of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the association of the Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ both with Rukn al-Din Samarqandi in the former century and with Shaikh Muhammad Ghauth in the latter century suggests the likelihood of its continued use in Bengal during the intervening period.

| • | • | • |

Sufis of the Capital

The principal carriers of the Islamic literary and intellectual tradition in the Bengal sultanate were groups of distinguished and influential Sufis who resided in the successive capital cities of Lakhnauti (from 1204), Pandua (from ca. 1342), and Gaur (from ca. 1432). Most of these men belonged to organized Sufi brotherhoods—especially the Suhrawardi, the Firdausi, and the Chishti orders—and what we know of them can be ascertained mainly from their extant letters and biographical accounts. The urban Sufis about whom we have the most information are clustered in the early sultanate period, from the founding of the independent Ilyas Shahi dynasty at Pandua in 1342 to the end of the Raja Ganesh revolution in 1415.[34]

The political roles played by Sufis in Bengal’s capital were shaped by ideas of Sufi authority that had already evolved in the contemporary Persian-speaking world. We have already referred to the central place that Sufi traditions assigned to powerful saints, a sentiment captured in ‘Ali Hujwiri’s statement that God had “made the Saints the governors of the universe.” Being in theory closer to God than warring princes could ever hope to be, Muslim saints staked a moral claim as God’s representatives on earth. In this view, princely rulers possessed no natural right to earthly power, but had only been entrusted with a temporary lease on such power through the grace of some Muslim saint. This perspective perhaps explains why in Indo-Muslim history we so often find Sufis predicting who would attain political office, and for how long they would hold it. For behind the explicit act of “prediction” lay the implicit act of appointment—that is, of a Sufi’s entrusting his wilāyat, or earthly domain, to a prince. For example, the fourteenth-century historian Shams-i Siraj ‘Afif recorded that before his rise to royal stature, the future Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq, founder of the Tughluq dynasty of Delhi (1321–1398), had been one of many local notables attracted to the spiritual power of the grandson of the famous Chishti Sufi Shaikh Farid al-Din Ganj-i Shakar (d. 1265). The governor made frequent visits to the holy man’s lodge in the Punjab, and on one occasion brought along his son and nephew, the future sultans Muhammad bin Tughluq and Firuz Tughluq. All three were given turbans by the saint and told that each was destined to rule India. The length of each turban, moreover, exactly corresponded to the number of years each would reign.[35] In this anecdote one may discern the seeds of the complex pattern of mutual patronage between shaikhs of the Chishti order and one of the mightiest empires in India’s history.

Similar traditions circulated in Bengal concerning the foundation of independent Muslim rule there. In 1243–44 the historian Minhaj al-Siraj visited Lakhnauti, where he recorded the following anecdote.[36] Before embarking for India, the future sultan of Bengal Ghiyath al-Din ‘Iwaz (1213–27) was once traveling with his laden donkey along a dusty road in Afghanistan. There he came upon two dervishes clothed in ragged cloaks. When the two asked the future ruler whether he had any food, the latter replied that he did and took the load down from the donkey’s back. Spreading his garments on the ground, he offered the dervishes whatever victuals he had. After they had eaten, the grateful dervishes remarked to each other that such kindness should not go unrewarded. Turning to their benefactor, they said, “Go thou to Hindustan, for that place, which is the extreme (point) of Muhammadanism, we have given unto thee.” At once the future sultan gathered together his family and set out for India “in accord with the intimation of those two Darweshes.”[37] In the Perso-Islamic cultural universe of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Bengal really did in some sense “belong” to those two dervishes, that they might “entrust” it to a kind stranger.

In Bengal as in North India, the connection between political fortune and spiritual blessing is most evident in the early history of the Chishti order, the order to which the most ascendant shaikhs of early-fourteenth-century Delhi belonged. “Anybody who was anyone,” as Simon Digby puts it, visited the lodge of Delhi’s most eminent shaikh of the time, Nizam al-Din Auliya (d. 1325). Indeed, the two principal Persian poets of the early fourteenth century, Amir Khusrau and Amir Hasan, together with the sultanate’s leading contemporary historian, Zia al-Din Barani, were all spiritual disciples of this shaikh. Since Delhi at this time happened to be the capital of a vital and expanding empire, it is not surprising that the literary, cultural, and institutional traditions of that city—together with the shaikhs and institutions of its dominant Sufi order—expanded along with Khalaji and Tughluq arms to the far corners of India, including Bengal.[38]

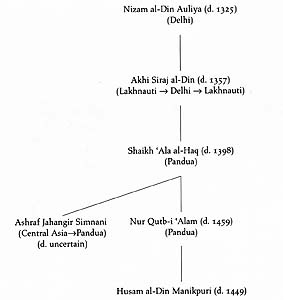

But there was a deeper reason why Indo-Muslim courts patronized Chishti shaikhs. By the fourteenth century, when other Sufi orders in India still looked to Central Asia or the Middle East as their spiritual home, the Chishtis, with their major shrines located within the Indian subcontinent, had become thoroughly indigenized. Seeking to establish their legitimacy both as Muslims and as Indians, Indo-Muslim rulers therefore turned to prominent shaikhs of this order for blessings and support. For the same reason, leading Chishti shaikhs dispersed from Shaikh Nizam al-Din’s lodge to all parts of the empire and often enjoyed the patronage of provincial rulers. Conversely, many young Indian-born Muslims journeyed from all over India to live in or near that shaikh’s lodge, later to return to their native lands, where they would establish daughter Chishti lodges and enjoy the patronage of local rulers (see table 2).

Table 2. Leading Chishti Sufis of Bengal

The first Bengal-born Muslim known to have studied with Shaikh Nizam al-Din was Akhi Siraj al-Din (d. 1357), who journeyed to Delhi as a young man. Having distinguished himself at the Sufi lodge of the renowned shaikh, Siraj al-Din received a certificate of succession and so thoroughly associated himself with the North Indian Chishti tradition that he was given the epithet “āyina-yi Hindūstān,” or “Mirror of Hindustan.” Returning to Bengal some time before 1325, when his master died, he inducted others into the Chishti discipline, his foremost pupil being another Bengal-born Muslim, Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq (d. 1398).[39] But unlike his own teacher, who had no known dealings with royalty,[40] Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq was destined to play a special role in the political history of Muslim Bengal. In fact, the earliest-known monument built by the founder of Bengal’s longest-lived dynasty, the Ilyas Shahi line of kings (1342–1486), was dedicated to this shaikh. On a mosque built in 1342 in what is now part of Calcutta, Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah praised the Sufi as “the benevolent and revered saint (Shaikh) whose acts of virtue are attractive and sublime, inspired by Allah, may He illuminate his heart with the light of divine perception and faith, and he is the guide to the religion of the Glorious, ‘Alaul-Haqqmay…his piety last long.”[41]

The importance of this inscription derives from its political context. Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah, an ambitious and politically astute newcomer to the delta, was just then launching a bid for independence from Delhi, evidently using southwestern Bengal as his power base. The imperial governor of nearby Satgaon having recently died, Shams al-Din, aware that Delhi was convulsed by the various crises provoked by the eccentric Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, seized the moment to attain provincewide power.[42] As his earliest-known coin was minted at Pandua in A.D. 1342–43 (A.H. 743),[43] Shams al-Din’s ascendancy exactly synchronizes with the dedication of this mosque and his patronage of Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq. Moreover, the patronage of the two men was mutual, since Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq, attaching himself to this rising political star, adopted Shams al-Din as a recipient of his teachings and blessings. This early connection cemented an alliance between government and prominent Chishti shaikhs that would last for the duration of Muslim rule in Bengal.

Not all alliances between Sufis and sultans were initiated by would-be rulers seeking to broaden their political bases. Some Sufis were drawn to the court out of a fervent desire to advance the cause of Islam as they understood it, and to augment the welfare of Muslims in the realm. We see this in the correspondence between Muzaffar Shams Balkhi (d. 1400) and Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah (r. 1389–1410). An immigrant from Central Asia, Muzaffar had left his native Balkh for Delhi, where he taught at the college of Firuz Shah Tughluq. But the man’s restless spirit led him to Bihar city, where, after meeting and becoming the disciple of the great Firdausi shaikh Sharaf al-Din Maneri (d. 1381), he experienced a major change in life-orientation. Abandoning his pride in scholarship, Muzaffar subjected himself to various austerities and distributed all his worldly possessions in charity. He also made several pilgrimages to Mecca, where he once stayed for four years, teaching lessons in ḥadīth scholarship.[44] His extant letters reveal him not as an ecstatic, quiescent, or contemplative sort, but as committed to imposing his understanding of the Prophet’s religious vision on the here-and-now world, a man inclined to scrutinize human society by scriptural standards and, finding it wanting, to transform it so as to meet those standards. In the sultan of Bengal, the Sufi found an outlet for these impulses.

Muzaffar Shams first seems to have become concerned about tutoring Sultan Ghiyath al-Din while waiting in Pandua for official permission to embark on a trip from Chittagong to Mecca. “The four months of the ship season are ahead of us,” he wrote; “there are eight months still left; during all this while I have spent my life as a guest in the auspicious threshold of your majesty, may not your exaltation lessen.”[45] Although the Sufi politely described himself as a mere “guest” of the sultan, it is evident that he felt himself entrusted with a higher calling. “In my opinion,” he wrote the king,

Who, here, is patronizing whom? The Sufi’s reference to the sultan as his “son” signals a clear inversion of the usual relationship between a patrimonial king and his subjects. Nor would the Sufi give the king privileged access to his personal correspondence; to see it the monarch had first to secure permission from a third party. Muzaffar Balkhi also reminded the king that although Sultan Firuz Tughluq of Delhi had repeatedly requested letters and spiritual guidance from Muzaffar’s own master, Shaikh Sharaf al-Din Maneri, the latter had refused to oblige him, choosing instead to correspond with Sultan Sikandar of Bengal, Ghiyath al-Din’s father. “You,” he noted pointedly, “have had the effects and legacy of those blessings on yourself.”[47] In short, Muzaffar felt that he and his own master had been doing the Bengal sultans a favor by bestowing their blessings and advice on them instead of on the sultans of Delhi.[48]by the gifts of God, the cherisher of mankind, you have developed a capacity of looking at the inside of things of the pure faith and the understanding of things of manifold signification. It appears that my heart would be opened out to you. A pious inspired man, Abdul Malik, has been a recipient of my letters[,] which might form a volume. It may be at Pandua or at Muazzamabad, but I don’t remember where it exactly is. Oh, my son, get the permission and go through its contents. Something of my inward part may be opened out to you. You are the second person on whom I have poured out my secret (mystic) thoughts. It behooves you not to disclose these to anyone else.[46]

In addition to his recommendations concerning Islamic piety—for example, on the need to suppress innovation not prescribed by the Shari‘a, or to enforce the payment of alms by Muslims[49]—Muzaffar cautioned the king against placing non-Muslims in positions of authority. “The substance of what has come in the tradition and commentaries,” wrote the shaikh, “is this”:

The Sufi thus saw in Islamic Law a clear course of action the sultan should take in order to avert certain disaster. For in Bengal’s affairs Muzaffar Shams discerned more than just a political crisis. Referring to Timur’s recent sacking of Delhi (A.D. 1398, or A.H. 801), which marked the eclipse of the once-mighty Tughluq empire, he wrote: “The eighth century has passed out, and the signs of the coming Resurrection are increasingly visible. An Empire like that of Delhi with all its expanse and abundance, spiritual and physical comfort, peace and tranquility, has turned upside down (is in a topsy-turvy condition). Infidelity has now come to hold the field; the condition of other countries is no better. Now is the time, and this is the opportunity.”[51] His gaze riveted on scripture, Muzaffar saw a palpable link between worldly decay and the Day of Judgment, heralded by that decay. Only by removing infidelity could Muslims forestall an otherwise inevitable cosmic process. And since the sultan had the power to stamp out infidelity by suppressing non-Muslims in a kingdom originally established by Muslims, the Sufi saw the sultan as capable of playing a pivotal role in implementing what he understood as God’s will in that process.“Oh believers, don’t make strangers, that is infidels, your confidential favourites and ministers of state.” They say that they don’t allow any to approach or come near to them and become favourite courtiers; but it was done evidently and for expedience and worldly exigency of the Sultanate that they are entrusted with some affairs. To this the reply is that according to God it is neither expediency nor exigency but the reverse of it, that is an evil and pernicious thing.…Don’t entrust a work into the hands of infidels by reason of which they would become a walī (Governor-ruler or superior) over the Musalmans, exercise their authority in their affairs, and impose their command over them. As God says in the Quran, “It is not proper for a believer to trust an infidel as his friend and walī, and those who do so have no place in the estimation of God.” Hear God and be devout and pious; very severe warnings have come in the Kitab (holy book) and traditions against the appointment of infidels as a ruler over the believers.[50]

It was shaikhs of the Chishti order, however, who by the early fifteenth century had emerged as the principal spokesmen for a Muslim communal perspective in Bengal. If Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq had risen to prominence with the ascending fortunes of the founder of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty, his son and successor, Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam (d. 1459), presided over Bengal’s Chishti tradition when Ilyas Shahi fortunes had sunk to their lowest point—the period of Raja Ganesh’s domination over the Ilyas Shahi throne.[52] According to Sufi sources, Raja Ganesh even persecuted Chishti shaikhs, banishing Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam’s own son, Shaikh Anwar, to Sonargaon, and plotting the death of the son of another Chishti shaikh, Husain Dhukkarposh.[53] In these circumstances, as noted in Chapter 2, the shaikh implored Sultan Ibrahim Sharqi of Jaunpur to invade Bengal and remove the “menace” of Raja Ganesh. The following passage shows the extent to which the Chishtis of Bengal had come to identify the fortunes of Islam with the political fortunes of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty. “After a period of three hundred years,” wrote the Sufi, “the Islamic land of Bengal—the place of mortals, the kingdom of the end of the seven heavens—has been overwhelmed and put to the run by the darkness of infidels and the power of unbelievers.” The shaikh elaborated this point using the Sufi and Qur’anic metaphor of light:

The lamp of the Islamic religion and of true guidance Which had [formerly] brightened every corner with its light, Has been extinguished by the wind of unbelief blown by Raja Ganesh. Splendor from envy of the victorious news, The lamp of [the celebrated preacher, Abu’l-Husain] Nuri, and the candle of [the Shi‘a martyr] Husain Have all been extinguished by the might of swords and the power of this thing in view. What does one call the lamp and candle of men Whose nature is devoid of virility [lit., has eaten camphor]? When the abode of faith and Islam has fallen into such a fate, Why are you sitting happily on your throne? Arise, come and defend the religion, For it is incumbent upon you, O king, possessed of power and capacity.[54]

While publicly clamoring for military intervention, privately, in a letter to his exiled son, Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam brooded over the theological implications of Raja Ganesh’s appearance in Bengali history. To the anguished Sufi, it seemed that God had not been heeding the supplication of the very people to whom the Qur’an had promised divine favor and protection. “Infidelity,” he wrote,

But the fortunes of Bengali Muslims did not ebb as the shaikh had feared. Once the stormy period of Raja Ganesh had subsided, his converted son resumed the patronage of the Chishti establishment, reconfirming the Chishti-court alliance that had been established between Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam’s father and the dynasty’s founder. Both Sultan Jalal al-Din and his son and successor Ahmad (r. 1432–33) became disciples of Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam himself, and twelve succeeding sultans down to the year 1532 enlisted themselves as disciples of the descendants of Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq.[56] By the end of the fifteenth century, the tomb of Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam in Pandua had become in effect a state shrine to which Sultan ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah (r. 1493–1519) made annual pilgrimages.[57]has gained predominance and the kingdom of Islam has been spoiled.…Neither the devotion and the worship of the votaries of God proved helpful to them nor the unbelief of the infidels fettered their steps. Neither worship and devotion does any good to His Holy Divine Majesty, nor does infidelity do any harm to Him. Alas! Alas! O, how painful! With one gesture and freak of independence he caused the consumption of so many souls, the destruction of so many lives, and shedding of so much of bitter tears. Alas, woe to me, the sun of Islam has become obscured and the moon of religion has become eclipsed.[55]

Despite the mutual patronage and even dependency between Bengal’s Sufis and its rulers, one also detects an undercurrent of friction between the two. Occasionally erupting into open hostility, this friction derived from the radical distinction made in Islam between dīn and dunyā, “religion” and “the world.” Withdrawn from worldly affairs and living in a state of poverty, self-denial, and remembrance of God, the Sufi recluse was in theory dramatically opposed by the ruler-administrator, glittering in his wealth and utterly immersed in worldly affairs. Sufis who rejected the world made much of their refusal to consort with “worldly” people—including above all royalty. Conversely, rulers sometimes suspected their Sufi allies, or even feared having around them such popular, charismatic leaders who might conceivably stir up the mob to riot or rebellion.[58]

Here we may consider an inscription of Sultan Sikandar Ilyas Shah, dated 1363, in which the king dedicated a dome he had built for the shrine of a saint named Maulana ‘Ata. Although the shaikh may have been the king’s contemporary, Maulana ‘Ata was more likely an earlier holy man whose shrine had become the focus of an important cult by the time the inscription was recorded.[59] “In this dome,” the inscription reads,

While outwardly acclaiming the greatness of Maulana ‘Ata, Sultan Sikandar was also asserting his own claims to closeness to God, styling himself the one in whose name “the pearls of prayer have been strung,” and “the Shadow of God on Earth.” And by referring to this shrine as a copy (nuskha) of the heavens, the sultan drew attention to parallels between God’s creative activity and his own. For if it had been God’s creative act to adorn the seven heavens with lamps (maṣābīḥ), that is, stars, it was Sultan Sikandar’s creative act to adorn the earth with a tomb for the lamp (sirāj) of Truth, Law, and Faith, that is, Maulana ‘Ata. Implicitly, then, had it not been for the munificence of Sultan Sikandar, Maulana ‘Ata would have remained shrouded in obscurity.which has been founded by ‘Ata, may the sanctuary of both worlds remain. May the angels recite for its durability, till the day of resurrection: “We have built over you seven solid heavens” [Qur’an 78:12].

By the grace of (the builder of) the seven wonderful porticos “who hath created seven heavens, one above another” [Qur’an 67:3], may His names be glorified; the building of this lofty dome was completed. (Verily it) is the copy of a vault (lit., shell) of the roof of Glory, (referred in this verse) “And we have adorned the heaven of the world” (lit., lamps) [Qur’an 67:5]. (This lofty dome) in the sacred shrine of the chief of the saints, the unequaled among enquirers, the lamp of Truth, Law and Faith, Maulana ‘Ata, may the High Allah bless him with His favours in both worlds; (was built) by order of the lord of the age and the time, the causer of justice and benevolence, the defender of towns, the pastor of people, the just, learned and great monarch, the shadow of Allah on the world, distinguished by the grace of the Merciful, Abu’l Mujahid Sikandar Shah, son of Ilyas Shah, the Sultan, may Allah perpetuate his kingdom.

The king of the world Sikandar Shah, in whose name the pearls of prayer have been strung; regarding him they have said, “May Allah illuminate his rank,” and regarding him they have prayed “May Allah perpetuate his kingdom.”[60]

Royal distrust of or aversion to Sufis, even those of the Chishti order, is seen in other ways. Although Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah had patronized a prominent Chishti shaikh while establishing a new dynasty, the king’s son and successor, Sultan Sikandar, was suspicious of the disciples of his father’s saintly patron. He was especially suspicious of the most eminent of these, Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq, whose shrine complex had become in Sikandar’s day a major nexus for economic transactions, redistributing amongst the city’s poor large sums of money received in the form of pious donations.[61] Alarmed at the Sufi’s substantial expenditure on the urban populace, Sikandar declared: “My treasure is in the hands of your father [the kingdom’s Treasurer]; [yet] you are giving away as much as he spends.” Evidently jealous of the shaikh’s wealth and influence, the king banished the Sufi to Sonargaon.[62]

Bengal’s Sufis and sultans, then, were fatefully connected by ties of mutual attraction and repulsion. Generally, when they were first establishing themselves politically, and especially when launching new dynasties, rulers actively sought the legitimacy powerful saints might lend them. Sultan Ghiyath al-Din ‘Iwaz’s earliest chronicler situated the launching of Bengal’s first independent dynasty (1213) in the context of the grace, or baraka, of two simple dervishes in Afghanistan. And in 1342, when Sultan Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah launched the longest-lived dynasty in Muslim Bengal, he did so with the blessings of a renowned scion of the prestigious Chishti line. Struck by the awesome spiritual powers people attributed to charismatic shaikhs, or believing that their own lease on power was somehow extended by such forceful men, new Muslim kings sought their favor, built lodges or mausolea for them, or made public pilgrimages to their tombs. Conversely, some Sufis sought royal patronage out of their own reformist impulses to bring “the world” (dunyā) into proper alignment with their understanding of the dictates of normative “religion” (dīn).

On the other hand, once dynasties were securely entrenched in power, some kings no longer considered it necessary to call upon the charismatic authority of holy men to legitimate their rule. In fact, the wealth and influence of charismatic shaikhs were sometimes seen as potential threats to royal authority. Sikandar Ilyas Shah only begrudgingly patronized a saint on whose mausoleum he heaped more praise on himself than on the saint. And he actually banished the most eminent shaikh of the day from his capital when he felt his authority rivaled. Only after the death of Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam in the mid fifteenth century, when Sufism’s intellectually vibrant tradition was replaced by a politically innocuous tomb-cult, did the state once again wholeheartedly ally itself with the Chishti tradition.

Notes

1. Rudi Paul Lindner, Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1983), 24. See also Gerald Clauson, Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth Century Turkish (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 128.

2. Z. A. Desai, “An Early Thirteenth-Century Inscription from West Bengal,” Epigraphia Indica, Arabic and Persian Supplement (1975): 6–12. The inscription was found in the village of Siwan, in Bolpur Thana of Birbhum District.

3. D. C. Sircar, “New Light on the Reign of Nayapala,” Bangladesh Itihas Parishad: Third History Congress, Proceedings (Dacca: Bangladesh Itihas Parishad , 1973): 36–43.

4. Lindner, Nomads and Ottomans, 1–38; R. C. Jennings, “Some Thoughts on the Gazi Thesis,” Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 76 (1986): 151–61.

5. Lindner, Nomads and Ottomans, 7. See also Rudi Paul Lindner, “Stimulus and Justification in Early Ottoman History,” in Greek Orthodox Theological Review 27, nos. 2–3 (Summer-Fall 1982): 207–24.

6. Maulana Jamali, Siyar al-‘ārifīn (Delhi: Matba‘ Rizvi, 1893), 164–69.

7. Ibid., 171.

8. The account of Shaikh ‘Ali was later reproduced in the well-known hagiography Gulzār-i abrār, compiled ca. 1613, the relevant extracts of which were published by S. M. Ikram, “An Unnoticed Account of Shaikh Jalal of Sylhet,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan 2 (1957): 63–68. Since Ahmad Yasawi died in 1166, Shah Jalal’s own spiritual master must have been an unidentified intermediary between Yasawi and Shah Jalal.

9. Ibid., 66. Ikram’s translation.

10. The oldest Persian treatise on Sufism, the Kashf al-maḥjūb by ‘Ali Hujwiri (d. ca. 1072), composed in Lahore, had already elaborated Sufi ideas on the two kinds of jihād. See The Kashf al-mahjub, trans. Reynold A. Nicholson, 2d ed. (reprint, London: Luzac, 1970), 201.

11. Ikram, “Unnoticed Account,” 66.

12. The Persian original, compiled in 1613 by Muhammad Ghauthi b. Hasan b. Musa Shattari, reads: “Shaikh Mujarrad hama-rā hiṣṣa sākhtawa har yak-rā dastūrī-yi kadkhudā shudan nīz bar dād .” Gulzār-i abrār (Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, Persian MS. 259), fol. 41a. The Persian version published by Ikram mistakenly reads: “…wa har yak-rā dastūrī ki khudā shudan nīz bar dād, ” which would mean, “…and he gave an order that each of them also become God”(!) Ikram, “Unnoticed Account,” 65.

13. Lindner argues that “the pastoral Ottomans followed their own economic self-interest, that is, they settled because they made a much better and more secure living as landlords or cultivators in Bithynia.” Moreover, “a given area used for cultivation, if it is as fertile as Bithynia, can support a much larger population than it can if used as pasture alone. The yield, in calories, of a plot of good land used for crops is much higher than the ultimate yield if that land is merely grazed.” Lindner, Nomads and Ottomans, 30. The same arguments would apply to the Bengal delta, where the economic value of a plot of land in rice paddy is considerably greater than if it were used for pasture.

14. Shamsud-Din Ahmed, ed. and trans., Inscriptions, 4: 25. Shah Jalal’s fame at the time of this inscription is evident from its opening lines, which honor “the exalted Shaikh of Shaikhs, the revered Shaikh Jalal, the ascetic, son of Muhammad.” It is not clear to what building in Sylhet the inscription, currently preserved in the Dhaka Museum, was originally affixed.

15. Ibn Battuta, The Rehla of Ibn Battuta, trans. Mahdi Husain (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1953), 238–39.

16. Ibid., 237–38.

17. “The inhabitants of Habanq [near Habiganj] are infidels under protection (dhimma) from whom half of the crops which they produce is taken.” Ibid., 241.

18. Ibid., 237–38.

19. Abu’l-fazl ‘Allami, ā’īn-i Akbarī (Lucknow: Nawal Kishor, 1869), 2: 74. Vol. 1 trans. H. Blochmann, ed. D. C. Phillott; vols. 2 and 3 trans. H. S. Jarrett, ed. Jadunath Sarkar, 3d ed. (New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corp., 1978), 2: 130.

20. Mirza Nathan, Bahāristān-i ghaibī, Persian MS., Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, Sup. Pers. 252, fol. 146b; trans. M. I. Borah as Bahāristān-i-ghaybī: A History of the Mughal Wars in Assam, Cooch Behar, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa during the reigns of Jahāngīr and Shāhjahān, by Mīrza Nathan (Gauhati: Government of Assam, 1936), 1: 273.

21. Shihab al-Din Talish, Fatḥiyah-i ‘ibriyah, in H. Blochmann, “Koch Bihar, Koch Hajo, and Assam in the 16th and 17th Centuries, According to the Akbarnamah, the Padshahnamah, and the Fathiyah i ‘Ibriyah,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 41, no. 1 (1872): 79.

22. For notices on Rukn al-Din Samarqandi, see Encyclopaedia of Islam, new ed. (Leiden: Brill, 1960), 1: 434–35. For a discussion of the problems of identifying the translators of the Amṛtakuṇḍa, see Yusuf Husain, “Haud al-hayat : La Versionarabe de l’Amratkund,” Journal asiatique 113 (October-December 1928): 292–95.

23. Although there are no known copies of the original Sanskrit work, there are many translations in Islamic languages, indicating the enormous influence this work had in and beyond Bengal. Islamic Culture 21 (1947): 191–92 refers to a Persian manuscript version of the text, entitled Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ, preserved in the library of Pir Muhammad Shah in Ahmedabad, Gujarat (No. 223). Another Persian copy of this work is in the India Office Library, London (Persian MS. No. 2002). A third manuscript copy is in the Ganj Bakhsh Library, Rawalpindi (MS. No. 6298). A fourth, dating to the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, and containing twenty-one illustrations of yogic postures, is in the library of A. Chester Beatty in Dublin; see Thomas A. Arnold, The Library of A. Chester Beatty: A Catalogue of the Indian Miniatures, revised and ed. J. V.S. Wilkinson (London: Oxford University Press, 1936), 1: 80–81, 3: 98. According to the Islamic Culture article cited above (p. 192), an edition of the Persian Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ was published in Madras in 1892–93. Arabic translations of the Amṛtakuṇḍa are entitled ḥauẓ al-ḥayāṭ, and five of those preserved in European libraries were compared and analyzed by Yusuf Husain in his article “Haud al-hayat : La Version arabe,” to which the author appended an Arabic version of the text. Carl Ernst, who is now preparing for publication a critical edition of the Arabic text, together with an annotated translation and monographic introduction, has identified forty manuscript copies of Arabic translations, seventeen of which are in Istanbul. Turkish translations began appearing in the mid eighteenth century, and one was published in 1910–11. A nineteenth-century Urdu translation survives in a manuscript in Hyderabad, India. See Carl W. Ernst, trans., The Arabic Version of “The Pool of the Water of Life” (Amṛtakuṇḍa), forthcoming.

24. S. A.A. Rizvi, A History of Sufism in India (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1978), 1: 335.

25. Muhsin Fani, Dabistān-i maẓāhib, ed. Nazir Ashraf and W. B. Bayley (Calcutta, 1809), 224.

26. Husain, “Haud al-hayat : La Version arabe,” 294.

27. The Gulzār al-abrār, compiled around 1613, or just fifty years after the death of Shaikh Muhammad Ghauth, mentions a translation (from the Arabic to Persian) of the Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ as among the written works of the great saint of Gwalior. See Muhammad Ghauthi Shattari Mandawi, Gulzār-i abrār, Urdu trans. by Fazl Ahmad Jiwari (Lahore: Islamic Book Foundation, 1975), 300.

28. Islamic Culture 21 (1947), 191–92. The Persian extract published in Islamic Culture was taken from a manuscript copy of the Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ in the library of Pir Muhammad Shah of Ahmadabad (No. 223). See also the copy in the India Office Library, Persian MS. 2002, fols. 2a-3a, in which the yogi’s name is given as Kanama.

29. Baḥr al-ḥayāṭ (India Office Library, London, Persian MS. 2002), fols. 3a-6b.

30. In particular, they recall the classic statement of the Sufi path, The Conference of the Birds, or Manṭiq al-ṭayr, composed by Farid al-Din ‘Attar (d. 1220). In fact, since both ‘Attar and Shaikh Rukn al-Din Samarqandi, perhaps the first translator of the Amṛtakuṇḍa, were contemporaries in Khurasan toward the end of the twelfth century, it is possible that the latter was familiar with ‘Attar’s mystical philosophy. Certainly, both were steeped in the same Perso-Islamic literary and religious culture. On the other hand, it is possible that this second prologue was written not by Samarqandi but by Muhammad Ghauth three centuries later, since we know that the latter retranslated the work into Persian. Carl Ernst, following the views of Henry Corbin, has argued that the frame story was ultimately derived from the “Hymn of the Pearl,” found in the gnostic Acts of Thomas. See Ernst, Arabic Version (forthcoming), and Henry Corbin, “Pour une morphologie de la spiritualité Shī‘ite,” Eranos-Jahrbuch 1960 (Zurich: Rhein-Verlag, 1961), 29: 102–7.

31. Yusuf Husain, among others, has argued for the work’s syncretic nature. See Husain, “Haud al-hayat : La Version arabe,” 292.

32. For example, in a passage in which proper breathing technique is compared with the way a foetus breathes in its mother’s womb, the foetus is identified with al-Khiẓr, a popular saint in Islamic lore, associated with water and eternal life. Again, where such techniques are compared with the way a fish breathes in water without swallowing it, the fish is identified with the one that swallowed the Prophet Jonah. And the seven Sanskrit mantras associated with the seven spinal nerve centers are all identified with Arabic names of God, so that, for example, hūm is translated as Yā rabb (“O Lord”), and aum is translated Yā qadīm (“O Ancient One”). These were not so much “translations” as they were attempts at finding functional equivalents between yogic words of spiritual power and the names of God as used by the Sufis. See Yusuf Husain, “Haud al-hayat : La Version arabe,” 300, and Ernst, Arabic Version (forthcoming).

33. While in Bengal, Shah ‘Abd Allah made a spiritual disciple of Shaikh Muhammad ‘Ala, who enthusiastically propagated the Shattari order in the delta, and whose own spiritual successor, Shaikh Zuhur Baba Haji Hamid (d. 1524), was the spiritual master of Shaikh Muhammad Ghauth. Rizvi, History of Sufism in India, 2: 153–55. Muhammad Ghauth’s elder brother, Shaikh Bahlul, also resided in Bengal after having arrived with the first Mughal invasion in 1538. Jahangir, Tūzuk-i Jahāngīrī 2: 63.

34. Around 1414 the Chishti shaikh Ashraf Jahangir Simnani stated that seventy disciples of Shaikh Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi (d. 1144) had been buried in Devgaon (site not identified), and that other Sufis of the Suhrawardi order, together with followers of Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi (see above), were buried in Mahisantosh and Deotala, both near Pandua. “In short,” he noted, “in the country of Bengal, not to speak of the cities, there is no town and no village where holy saints did not come and settle down.” Shaikh Ashraf Jahangir Simnani, Maktūbāt-i ashrafī, Aligarh Muslim University History Department, Aligarh, Persian MS. no. 27, letter 45, fols. 139b–140a. See also S. H. Askari, “New Light on Rajah Ganesh and Sultan Ibrahim Sharqi of Jaunpur from Contemporary Correspondence of Two Muslim Saints,” Bengal Past and Present 57 (1948): 35.

35. Shams-i Siraj ‘Afif, Tārīkh-i Fīrūz Shāhī, ed. Maulavi Vilayat Husain. (Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1891), 27–28.

36. Since Sultan Ghiyath al-Din ‘Iwaz had died only seventeen years before Minhaj’s visit, it is probable that this story had been in circulation in the Bengali capital soon after, and perhaps during, the king’s reign.

37. Minhaj-ud-Din ‘Usman, ṭabakāt-i-Nāṣirī, 1: 581.

38. Simon Digby, “The Sufi Shaikh as a Source of Authority in Mediaeval India,” in Puruṣārtha, vol. 9: Islam et société en Asie du sud, ed. Marc Gaborieau (Paris: Ecole des Hautes études en sciences sociales, 1986), 68–69. Even when Bengal was independent of Delhi, prominent shaikhs of this order maintained close institutional links with North India—a circumstance that led A. B.M. Habibullah to describe the Chishtis of Bengal as a sort of “fifth column” for the Delhi sultanate. A. B.M. Habibullah, review of Abdul Karim, Social History of the Muslims in Bengal, in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan 5 (1960): 216–17.

39. ‘Abd al-Rahman Chishti, Mirāt al-asrār, fol. 514a.

40. Indeed, Akhi Siraj endeavored to break his more highborn disciples of their aristocratic ways. In the case of ‘Ala al-Haq, whose father was a prominent migrant from Lahore and the treasurer of Bengal’s provincial government, Siraj taught his disciple to humble himself by walking with a hot cauldron on his head through the quarter of Lakhnauti where his family lived. Akhbār al-akhyār, comp. ‘Abd al-Haq Muhaddis Dihlavi (Deoband, U. P.: Kitab Khana-yi Rahimia, 1915–16), 149. In 1357 Akhi Siraj died and was buried in a suburb of Lakhnauti. Alexander Cunningham identified his tomb and shrine with a high mound in “Sadullahpur,” near the northeast corner of the Sagar Dighi tank. Cunningham, “Report of a Tour in Bihar and Bengal in 1879–80 from Patna to Sunargaon,” in Archaeological Survey of India, Report 15 (Calcutta, 1882): 70.

41. Shamsud-Din Ahmed, ed. and trans., Inscriptions, 4: 31–33. The editor himself found the stone with this inscription “while strolling through the eastern suburb of Calcutta, early in 1939.” He was told that around 1900 the stone had been picked up from a ruined mosque in the neighborhood.

42. Ibid., 32.

43. Karim, Corpus, 47.

44. S. H. Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature as a Source of Socio-PoliticalHistory (Patna: Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library, 1981), 22.

45. Muzaffar Shams Balkhi, Maktūbāt-i Muz̄affar Shams Balkhī (Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library, Patna, Persian MS., Acc. no. 1859), letter 148, p. 448. Partially translated by S. H. Askari in Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 16. Askari’s translation.

46. The Sufi then advised the sultan that whenever he was confronted with an important concern, he should notify the Sufi of it by sending either a letter or a messenger to Mecca. Balkhi, Maktūbāt, letter 163, p. 493. See also Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 19. Askari’s translation.

47. Balkhi, Maktūbāt, letter 163, p. 503. See also Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 21. Askari’s translation.

48. Also at work here was a keen rivalry between two major Sufi orders for royal patronage—the Chishtis, who were dominant in Delhi, and the Firdausis, who under Shaikh Sharaf al-Din Maneri’s leadership were dominant in Bihar. In this correspondence, the Firdausis were clearly making a bid for patronage from the kings of Bengal. For the Firdausi-Chishti rivalry, see Digby, “Sufi Shaikh as a Source,” 65–67.

49. Balkhi, Maktūbāt, letter 165, p. 495. See also Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 20.

50. Balkhi, Maktūbāt, letter 165, pp. 508–9. See also Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 22. Askari’s translation.

51. Balkhi, Maktūbāt, letter 165, p. 502. See also Askari, Maktub and Malfuz Literature, 21. Askari’s translation.

52. The traditional date of Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam’s death is 818 A.H. (1415–16 A.D.), as recorded in the Mirāt al-asrār (fol. 603b). But this date conflicts with the same work’s statement that the shaikh was the spiritual teacher of Sultan Ahmad, who ruled in 1432–33 (ibid., fol. 517b). Moreover, an inscription at the kitchen of Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam’s shrine in Pandua honors “Our revered master, the Teacher of Imams, the Proof of the congregation, the Sun of the Faith, the Testimony of Islam and of the Muslims, who bestowed advantages upon the poor and the indigent, the Guide of saints and of such as wish to be guided.” The inscription gives the death of this unnamed saint, who is evidently Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam, as 28 Zi’l-Hajj, 863, or 1459 A.D. (see Dani, “House of Raja Ganesh,” 139–40). The shaikh’s surviving writings attest to the vitality of Chishti thought and traditions in the capital city at this time. A surviving mystical work of his is the Mu’nis al-fuqarā’ (Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, Persian MS. No. 466). We also have his letters, the Maktūbāt-i Shaikh Nūr Qutb-i ‘ālam (Indian National Archives, New Delhi, Persian MS., Or. MS. No. 332, and Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Subhan Allah No. 297671/18).

53. ‘Abd al-Rahman Chishti, Mirāt-i asrār, fol. 517a. See also Askari, “New Light,” 37; Abdul Karim, “Nur Qutb Alam’s Letter on the Ascendancy of Ganesa,” in Abdul Karim Sahitya-Visarad Commemoration Volume, ed. Muhammad Enamul Haq (Dacca: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, 1972), 336–37.

54. Quoted by Shaikh Ashraf Jahangir Simnani in his Maktūbāt-i ashrafī, letter no. 45, fol. 139a.

55. Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam, Maktūbāt-i Shaikh Nūr Quṭb-i ‘ālam (Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Persian MS., Subhan Allah No. 297671/18), letter no. 9, p. 60. See also Abdul Karim, “Nur Qutb Alam’s Letter,” 342–43. Karim’s translation. These sentiments, like those found in the correspondence of Muzaffar Shams Balkhi, suggest that the words and actions of Pandua’s shaikhs were motivated by a genuine concern with advancing the cause of Islamic piety in Bengal, and not, as Jadunath Sarkar has suggested, by a narrow desire to safeguard their own economic and political interests. In referring to a “vast horde of unruly and ambitious disciples of the Shaikhs and Muslim monks, whose wealth and power had lately begun to overshadow the civil power,” Sarkar depicts these men as little more than parasites who preyed upon ageing or weak rulers, and compares their position “to that of the Buddhist monks to whom the Emperor Asoka gave away all his State treasure in his dotage.” Sarkar, ed., History of Bengal, 2: 126, 127.

56. ‘Abd al-Rahman Chishti, Mirāt al-asrār, fols. 517a-b.

57. Nizamuddin Ahmad, Tabaqāt-i Akbarī, text, 3: 270; trans. B. De, 3, pt. 1, 443.

58. For a discussion of these issues, see Digby, “Sufi Shaikh as a Source of Authority,” esp. 63–69.

59. The shrine is in the ancient Muslim garrison city of Devikot, located in modern West Dinajpur District some 33 miles northeast of Sikandar’s capital at Pandua. From the language of the inscription, it would appear that Sikandar was patronizing the construction only of the dome and not of the shrine itself, which in turn suggests the existence of a cult focused on a long-deceased saint. Three other inscriptions were fixed to the wall of this shrine, one of which, dated 1297, referred to the construction in that year of a mosque by Sultan Rukn al-Din Kaikaus. Another, dated 1493, stated that “the construction of this mosque was made during the time of the renowned saint, the chief of the holy men, Makhdum Maulana ‘Ata, may Allah make his ashes fragrant and may He make Paradise his resting place.” If the latter inscription refers to the same mosque referred to in the 1297 inscription—and this is not absolutely certain—then Maulana ‘Ata would have been alive about sixty years before Sultan Sikandar ascended the throne. Shamsud-Din Ahmed, ed. and trans., Inscriptions, 4: 15–18, 143–44.

60. Ibid., 34–35. Italicized words are from the Qur’an.

61. Moreover, disciples from throughout the region and beyond came to study at the lodge of Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq, the most prominent being Ashraf Jahangir Simnani, an immigrant from Central Asia whose letters form a major hagiographical source for this period. Although his Maktūbāt-i ashrāfī has never been published, manuscript copies are available in the Aligarh Muslim University History Department (MS. No. 27) and the British Library (Or. MS. No. 267).

62. ‘Abd al-Rahman Chishti, Mirāt al-asrār, fols. 515b-516a. ‘Ala al-Haq’s exile lasted for only several years, after which he was allowed to return to the capital, where he outlived the sultan by nine years. His experience compares with that of Maulana Ashraf al-Din Tawwama, a scholar and Sufi who had migrated from Bukhara to Delhi in the early fourteenth century, and who was exiled to Sonargaon by the Delhi court after having acquired an immense following among the city’s masses. See Shaikh Shu‘aib Firdausi, comp., Manāqib al-asfiyā (Calcutta: Nur al-Afaq, 1895), 131.