2. The Articulation of Political Authority

The world is a garden, whose gardener is the state.

We arrived before the Sultan. He was seated on a large gilt sofa covered with different-sized cushions, all of which were embedded with a smattering of precious stones and small pearls. We greeted him according to the custom of the country—hands crossed on our chests and heads as low as possible.

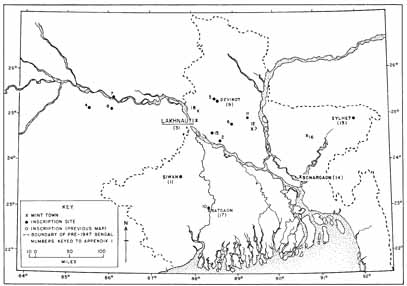

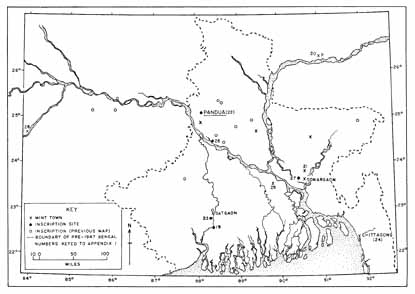

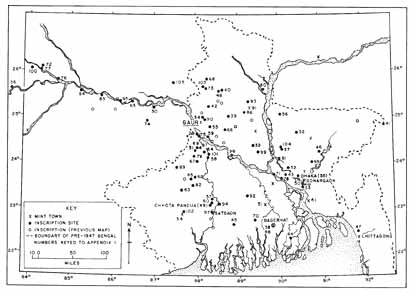

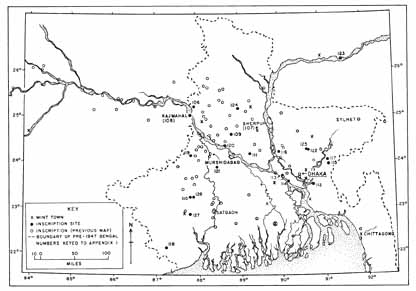

The geographic expansion of Muslim power in premodern Bengal is easy enough to reconstruct. In any given area of the delta, as in the premodern Muslim world generally, the erection of mosques, shrines, colleges, or other buildings, civil or military, usually presupposed control by a Muslim state. Epigraphic data testifying to the construction of such buildings thus form one kind of evidence for political expansion. The same is true of coinage. Since reigning kings jealously claimed the right to strike coins as a token of their sovereignty, the growth of mint towns also reflects the expanding territorial reach of Muslim states. These two kinds of sources, epigraphic and numismatic, thus permit a visual reconstruction of the growth of Muslim political authority in Bengal through time and space, as depicted in map 2.

It is more challenging, however, to reconstruct the changing meaning of that authority, both to the rulers and to the subject population. All political behavior derives its meaning through the prism of culture. Equally, invocations of political symbols most effectively confer authority on rulers when they and their subjects share a common political culture.[1] But what happened in the cases of “conquest dynasties,” as in Bengal, where the conquering class was of a culture fundamentally different from that of the subject population? How did rulers in such circumstances remain in effective control without resorting to the indefinite and prohibitively costly use of coercive force? To raise these questions is to suggest that the political frontier in Bengal may be understood not only as a moving line of garrisons, mint towns, and architectural monuments. Also involved was the more subtle matter of accommodation, or the lack of it, between a ruling class and a subject population that, as of 1204, adhered to fundamentally different notions of legitimate political authority. The transformation of these concepts of legitimacy over time—their divergence from or convergence with one another—constitutes a political frontier far less tangible than a military picket line, but one ultimately more vital to understanding the dynamics of Bengal’s premodern history.

| • | • | • |

Perso-Islamic Conceptions of Political Authority, Eleventh-Thirteenth Centuries

By the time Muhammad Bakhtiyar conquered northwestern Bengal in 1204, Islamic political thought had already evolved a good deal from its earlier vision of a centralized, universal Arab caliphate. In that vision the caliph was the “successor” (Ar., khalīfa) to the Prophet Muhammad as the combined spiritual and administrative leader of the worldwide community of Muslims. In principle, too, the caliphal state, ruled from Baghdad since A.D. 750, was merely the political expression of the worldwide Islamic community. But by the tenth century that state had begun shrinking, not only in its territorial reach, but, more significantly, in its capacity to provide unified political-spiritual leadership. This was accompanied, between the ninth and eleventh centuries, by the movement of clans, tribes, and whole confederations of Turkish-speaking peoples from Inner Asia to the caliphate’s eastern provinces. Coming as military slave-soldiers recruited to shore up the flagging caliphal state, as migrating pastoral nomads, or as armed invaders, these Turks settled in Khurasan, the great area embracing today’s northeastern Iran, western Afghanistan, and Central Asia south of the Oxus River. As Baghdad’s central authority slackened, Turkish military might provided the military basis for new dynasties—some Iranian, some Turkish—that established themselves as de facto rulers in Khurasan.

Map 2a. 1204–1342: governors, Balbani rulers, Shams al-Din Firuz, and sucessors (1204–81; 1281–1300;1301–22; 1322–42)

Map 2b. 1342–1433: Ilyas Shahi and Reaja Ganesh dynasties (1342–1414; 1415–33)

Map 2c. 1433–1538: restored Ilyas Shahis, Abyssynian kings, and Hussain Shahis (1433–86; 1486–93; 1493–1538)

Map 2d. 1539–1760: Afghans and Mughals (1538–75; 1575–1760)

Important cultural changes coincided with these demographic and political developments. Khurasan was not only Inner Asia’s gateway to the Iranian Plateau and the Indian subcontinent. It was also the principal region where Iran’s rich civilization, largely submerged in the early centuries of Arab-Islamic rule, was being revitalized in ways that creatively synthesized Persian and Arab Islamic cultures. The product, Perso-Islamic civilization, was in turn lavishly patronized by the several dynasties that arose in this area—notably the Tahirids, the Saffarids, the Samanids, and the Ghaznavids—at a time when Baghdad’s authority in its eastern domains was progressively weakening. Although themselves ethnic Turks, the Ghaznavids (962–1186) promoted the revival of Persian language and culture by attracting to their regional courts the brightest “stars” on the Persian literary scene, such as Iran’s great epic poet Firdausi (d. 1020). Ghaznavid rulers used the Persian language for public purposes, adopted Persian court etiquette, and enthusiastically promoted the Persian aesthetic vision as projected in art, calligraphy, architecture, and handicrafts. They also accepted the fiction of having been “appointed” by the reigning Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. Indeed, as recent Muslim converts themselves, Turkish soldiers in Ghaznavid service became avid partisans, defenders, and promoters of Sunni Islam.[2]

It was the Ghaznavids, too, who first carried Perso-Islamic civilization to India. Pressed from behind by the Seljuqs, a more powerful Turkish confederation, to whom in 1040 they lost any claim to Khurasan, Ghaznavid armies pushed ever eastward toward the subcontinent—first to eastern Afghanistan, and finally to Lahore in the Punjab. Toward the end of the twelfth century, however, the Ghaznavids were themselves overrun by another Turkish confederation, the chiefs of Ghur, located in the hills of central Afghanistan. In 1186 Muhammad Ghuri seized Lahore, extinguished Ghaznavid power there, and seven years later established Muslim rule in Delhi. A decade after that, Muhammad Bakhtiyar, operating in Ghurid service, swept down the lower Gangetic Plain and into Bengal.

The political ideas inherited by Muhammad Bakhtiyar and his Turkish followers had already crystallized in Khurasan during the several centuries preceding their entry into Bengal in 1204. This was a period when Iranian jurists struggled to reconcile the classical theory of the unitary caliphal state with the reality of upstart Turkish groups that had seized control over the eastern domains of the declining Abbasid empire. What emerged was a revised theory of kingship that, although preserving the principle that caliphal authority encompassed both spiritual and political affairs, justified a de facto separation of church and state. Whereas religious authority continued to reside with the caliph in Baghdad, political and administrative authority was invested in those who wielded the sword. Endeavoring to make the best of a bad situation, the greatest theologian of the time, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1111), concluded that any government was lawful so long as its ruler, or sulṭān, made formal acknowledgement of the caliph’s theoretical authority in his domain. A sultan could do this, Ghazali maintained, by including the reigning caliph’s name in public prayers (khuṭba) and on his minted coins (sikka).[3] In short, a sultan’s authority rested, not on any sort of divine appointment or ethnic inheritance, but on his ability to maintain state security and public order.[4]

In this way pre-Islamic Persian ideals of kingship—especially those focusing on society’s inherent need for a strong monarch and, reciprocally, on the monarch’s duty to rule with justice—were assimilated by the sultanates that sprang up within the caliphate’s eastern domains.[5] One of the clearest statements of this political vision was given by Fakhr al-Din Razi (d. 1209) of Herat, a celebrated Iranian scholar and jurist who served several Khurasani princes, in particular those of the Ghurid dynasty of Turks. Inasmuch as Razi was at the height of his public career when his own patrons conquered North India (1193) and Bengal (1204) and had even been sent once on a mission to northwestern India himself (ca. 1184), it is probable that his political thought was familiar to the Ghurid conquerors of Bengal. Certainly, Razi and Muhammad Bakhtiyar inherited a shared tradition of political beliefs and symbols current in thirteenth-century Khurasan and the Perso-Islamic world generally. In his Jāmi‘ al-‘ulūm Razi formulated the following propositions:

Far from mere platitudes about how kings ought to behave, these propositions present a unified theory of a society’s moral, political, and economic basis—a worldview at once integrated, symmetrical, and closed. One notes in particular the omission of any reference to God; it is royal justice, not the Deity, that binds together the entire structure. Islamic Law, though included in the system, appears as little more than a prop to the sultanate. And the caliph, though implicit in the scheme, is not mentioned at all.

The world is a garden, whose gardener is the state [dawlat]; The state is the sultan whose guardian is the Law [sharī‘a]; The Law is a policy, which is protected by the kingdom [mulk]; The kingdom is a city, brought into being by the army [lashkar]; The army is made secure by wealth [māl]; Wealth is gathered from the subjects [ra‘īyat]; The subjects are made servants by justice [‘adl]; Justice is the axis of the prosperity of the world [‘ālam].[6]

This ideology of monarchal absolutism was not, however, the only vision of worldly authority inherited by Muhammad Bakhtiyar and his Muslim contemporaries. By the thirteenth century there had also appeared in Perso-Islamic culture an enormous lore, written and oral, that focused on the spiritual and worldly authority of Sufis, or Muslim holy men. Their authority sometimes paralleled, and sometimes opposed, that of the courts of kings. For Turks, moreover, Sufi models of authority were especially vivid, since Central Asian Sufis had been instrumental in converting Turkish tribes to Islam shortly before their migrations from Central Asia into Khurasan, Afghanistan, and India.[7] This model of authority is seen in the oldest Persian treatise on Sufism, the Kashf al-maḥjūb of ‘Ali Hujwiri (d. ca. 1072). Written in Lahore in Ghaznavid times and subsequently read widely in India, this treatise summarized Sufi doctrines and practices as understood in the eastern Muslim world in the eleventh century. It also served to shape the contours of Sufism as a complete system of Islamic piety, especially in the Indo-Muslim world. Writing on the place of Sufi saints in the Muslim universe, Hujwiri asserted that God “has made the Saints the governors of the universe; they have become entirely devoted to His business, and have ceased to follow their sensual affections. Through the blessing of their advent the rain falls from heaven, and through the purity of their lives the plants spring up from the earth, and through their spiritual influence the Moslems gain victories over the unbelievers.”[8]

Such a vision, in which all things in God’s creation are dependent on a hierarchy of saints, would appear irreconcilable with the courtly vision of the independent sultan and his dependent “herd,” the people. And indeed there is a long history of conflict between these two visions of authority. Yet it is also true that the discourse of authority found in Sufi traditions often overlapped and even converged with that found in courtly traditions. For example, both Sufi and courtly literatures stressed the need to establish authority over a wilāyat, or a territorially defined region. The Arabic term walī, meaning “one who establishes a wilāyat,” meant in one tradition “governor” or “ruler” and in the other “saint” or “friend of God.” Again, in courtly discourse the Persian term shāh meant “king”; yet Sufis used it as the title of a powerful saint. In the same way, in royal discourse the dargāh referred to the court of a king, while for Sufis it referred to the shrine of a powerful saint. And as a symbol of legitimate authoritythe royal crown (tāj) used in the coronation ceremonies of kings closely paralleled the Sufi’s turban (dastār), used in rituals of succession to Sufi leadership.

These considerations would suggest that in the Perso-Islamic world of this period sultans did not exercise sole authority, or even ultimate authority. They certainly possessed effective power, reinforced by all the pomp and glitter inherited from their pre-Islamic Persian imperial legacy. Courtly sentiments like that expressed by Razi—“The world is a garden, whose gardener is the state”—indeed saw the world as a mere plaything of the state—that is, the sultan. Yet in a view running counter to this, both historical and Sufi works repeatedly hinted that temporal rulers had only been entrusted with a temporary lease of power through the grace (baraka) of this or that Muslim saint. For, it was suggested, since such saints possessed a special nearness to God, in reality it was they, and not princes or kings, who had the better claim as God’s representatives on earth. In the opinion of their followers, such powerful saints could even make or unmake kings and kingdoms.[9] So, while sultans formally acknowledged the caliph as the font of their authority, many people, and sometimes sultans too, looked to spiritually powerful Sufis for the ultimate source of that authority. From a village perspective, after all, kings or caliphs were as politically abstract as they were geographically distant; and after the Mongol destruction of Baghdad in 1258, caliphs all but ceased to exist even in name. Sufi saints, by contrast, were by definition luminous, vivid, and very much near at hand.

Thus, by the thirteenth century, when Bengal was conquered by Muslim Turks, sultans and Sufis had both inherited models of authority that, though embedded in a shared pool of symbols, made quite different assumptions about the world and the place that God, kings, and saints occupied in it. Moreover, both models differed radically from the ideas of political legitimacy current among the Hindu population formerly ruled by kings of the conquered Sena dynasty. For in Islamic cosmology, as communicated, for example, in Muslim Bengali coinage, the human and superhuman domains were sharply distinct, with both the sultanate and the caliphate occupying a political space beneath the ultimate authority of God, who alone occupied the superhuman world. Consequently the sultan’s proper role, in theory at least, was limited to merely implementing the shari‘a, Sacred Law. On the other hand, Sena ideology posited no such rigid barrier between human and superhuman domains; movement between the two was not only possible but achievable through a king’s ritual behavior. And far from being under an abstract Sacred Law, the Senas understood religion itself, or dharma, as dependent on the king’s ritual performances. Hence the Senas had not seen themselves as implementing divine order; they sought rather to replicate that order on earth, and even to summon down the gods to reside in royally sponsored temples.

How, then, did people subscribing to these contrasting political ideologies come to terms with one another once it was understood that Muhammad Bakhtiyar and his successors intended to remain in Bengal?

| • | • | • |

A Province of the Delhi Sultanate, 1204–1342

The only near-contemporary account of Muhammad Bakhtiyar’s 1204 capture of the Sena capital is that of the chronicler Minhaj al-Siraj, who visited Bengal forty years after the event and personally collected oral traditions concerning it.[10] “After Muhammad Bakhtiyar possessed himself of that territory,” wrote Minhaj,

The passage clearly reveals the conquerors’ notion of the proper instruments of political legitimacy: reciting the Friday sermon, striking coins, and raising monuments for the informal intelligentsia of Sufis and the formal intelligentsia of scholars, or ‘ulamā.he left the city of Nudiah in desolation, and the place which is (now) Lakhnauti he made the seat of government. He brought the different parts of the territory under his sway, and instituted therein, in every part, the reading of the khutbah, and the coining of money; and, through his praiseworthy endeavours, and those of his Amirs, masjids [mosques], colleges, and monasteries (for Dervishes), were founded in those parts.[11]

Both their coins and their monuments reveal how the rulers viewed themselves and wished to be viewed by others. Both, moreover, were directed at several different audiences simultaneously. One of these consisted of the conquered Hindus of Bengal, who, having never heard a khuṭba, seen a Muslim coin, or set foot in a mosque, were initially in no position to accord legitimate authority either to these symbols or to their sponsors. But for a second audience—the Muslim world generally, and more immediately, the rulers of the Delhi sultanate, the parent kingdom from which Bengal’s new ruling class sprang—the khuṭba, the coins, and the building projects possessed great meaning. It is important to bear in mind these different audiences when “reading” the political propaganda of Bengal’s Muslim rulers.

Fig. 1. Gold coin of Muhammad Bakhtiar, struck in A.H. 601 (A.D. 1204–5) in Bengal in the name of Sultan Muhammad Ghuri. Obverse and reverse. Photo by Charles Rand, Smithsonian Institution.

Militarily, Muhammad Bakhtiyar’s conquest was a blitzkrieg; his cavalry of some ten thousand horsemen had utterly overwhelmed a local population unaccustomed to mounted warfare.[12] After the conquest, Bakhtiyar and his successors continued to hold a constant and vivid symbol of their power—their heavy cavalry—before the defeated Bengalis. In the year 1204–5 (601 A.H.), Bakhtiyar himself struck a gold coin in the name of his overlord in Delhi, Sultan Muhammad Ghuri, with one side depicting a Turkish cavalryman charging at full gallop and holding a mace in hand (fig. 1). Beneath this bold emblem appeared the phrase Gauḍa vijaye, “On the conquest of Gaur” (i.e., Bengal), inscribed not in Arabic but in Sanskrit.[13] On the death of the Delhi sultan six years later, the governor of Bengal, ‘Ali Mardan, declared his independence from North India and began issuing silver coins that also bore a horseman image (fig. 2).[14] And when Delhi reestablished its sway over Bengal, coins minted there in the name of Sultan Iltutmish (1210–35) continued to bear the image of the horseman (fig. 3).[15] For neither Muhammad Bakhtiyar, ‘Ali Mardan, nor Sultan Iltutmish was there any question of seeking legitimacy within the framework of Bengali Hindu culture or of establishing any sense of continuity with the defeated Sena kingdom. Instead, the new rulers aimed at communicating a message of brute force. As Peter Hardy aptly puts it, referring to the imposition of early Indo-Turkish rule generally, “Muslim rulers were there in northern India as rulers because they were there—and they were there because they had won.”[16]

Fig. 2. Silver coin of ‘Ali Mardan (ca. 1208–13), commemorating the conquest of Bengal in A.H. Ramazan 600 (A.D. May 1204). Obverse only.

Fig. 3. Silver coin of Sultan Iltumish (1210–35), struck in Bengal. Obverse only.

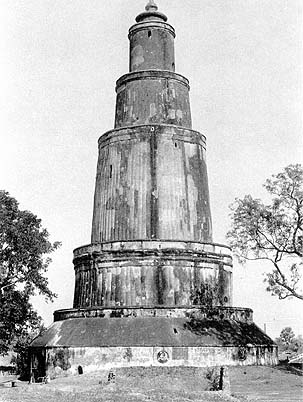

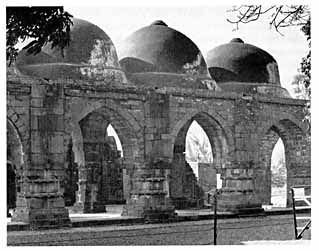

Such reliance on naked power, or at least on its image, is also seen in the earliest surviving Muslim Bengali monuments. Notable in this respect is the tower (mīnār) of Chhota Pandua, in southwestern Bengal near Calcutta (fig. 4). Built toward the end of the thirteenth century, when Turkish power was still being consolidated in that part of the delta, the tower of Chhota Pandua doubtless served the usual ritual purpose of calling the faithful to prayer, inasmuch as it is situated near a mosque. But its height and form suggest that it also served the political purpose of announcing victory over a conquered people. Precedents for such a monument, moreover, already existed in the Turkish architectural tradition.[17] Bengal’s earliest surviving mosques also convey the spirit of an alien ruling class simply transplanted to the delta from elsewhere. Constructed (or restored) in 1298 in Tribeni, a formerly important center of Hindu civilization in southwest Bengal, the mosque of Zafar Khan (fig. 5) appears to replicate the aesthetic vision of early Indo-Turkish architecture as represented, for example, in the Begumpur mosque in Delhi (ca. 1343). Clues to the circumstances surrounding the construction (or restoration) of the mosque are found in its dedicatory inscription:

Zafar Khan’s claims to have destroyed “the obdurate among infidels” gains some credence from the mosque’s inscription tablet, itself carved from materials of old ruined Hindu temples, while the mutilated figures of Hindu deities are found in the stone used in the monument proper.[19] Near Zafar Khan’s mosque stands another structure, built in 1313, which is said to be his tomb; its doorways were similarly reused from an earlier pre-Islamic monument, and embedded randomly on its exterior base are sculpted panels bearing Vaishnava subject matter.[20]

Zafar Khan, the lion of lions, has appeared By conquering the towns of India in every expedition, and by restoring the decayed charitable institutions. And he has destroyed the obdurate among infidels with his sword and spear, and lavished the treasures of his wealth in (helping) the miserable.[18]

Fig. 4. Minar of Chhota Pandua (late thirteenth century).

Fig. 5. Mosque of Zafar Khan Ghazi, Tribeni (1298).

How was the articulation of these political symbols received by the several “audiences” to whom they were directed? As late as thirty years after the conquest, pockets of Sena authority continued to survive in the forests beyond the reach of Turkish garrisons. Whenever Turkish forces were out of sight, petty chieftains with miniature, mobile courts would appear before the people in their full sovereign garb—riding elephants in ivory-adorned canopies, wearing bejeweled turbans of white silk, and surrounded by armed retainers—in an apparent effort to continue receiving tribute and administering justice as they had done before.[21] In 1236 a Tibetan Buddhist pilgrim recorded being accosted by two Turkish soldiers on a ferryboat while crossing the Ganges in Bihar. When the soldiers demanded gold of him, the pilgrim audaciously replied that he would report them to the local raja, a threat that so provoked the Turks’ wrath as nearly to cost him his life.[22] Clearly, after three decades of alien rule, people continued to view the Hindu raja as the legitimate dispenser of justice.

If Muslim coins and the architecture of this period projected to the subject Bengali population an image of unbridled power, they projected very different messages to the parent Delhi sultanate, and beyond that, the larger Muslim world. Throughout the thirteenth century, governors of Bengal tried whenever possible to assert their independence from the parent dynasty in Delhi, and each such attempt was accompanied by bold attempts to situate themselves within the larger political cosmology of Islam. For example, when the self-declared sultan Ghiyath al-Din ‘Iwaz asserted his independence from Delhi in 1213, he attempted to legitimize his position by going over the head of the Delhi sultan and proclaiming himself the right-hand defender (nāṣir) of the supreme Islamic authority on earth, the caliph in Baghdad.[23] This marked the first time any ruler in India had asserted a direct claim to association with the wellspring of Islamic legitimacy, and it prompted Iltutmish, the Delhi sultan, not only to invade and reannex Bengal but to upstage the Bengal ruler in the matter of caliphal support. After his armies defeated Ghiyath al-Din in 1227, Iltutmish arranged to receive robes of honor from Caliph al-Nasir in Baghdad, one of which he sent to Bengal with a red canopy of state. There it was formally bestowed upon Iltutmish’s own son, who was still in Lakhnauti, having just had the erstwhile independent king of Bengal beheaded.[24] By having the investiture ceremony enacted in the capital city of the defeated sultan of Bengal, Iltutmish vividly dramatized his own prior claims to caliphal legitimacy. For the time being, the delta was politically reunitedwith North India, and for the next thirty years Delhi appointed to Bengal governors who styled themselves merely “king of the kings of the East” (mālik-i mulūk al-sharq).[25]

But Delhi was distant, and throughout the thirteenth century the temptation to throw off this allegiance proved irresistible, especially as the imperial rulers were chronically preoccupied with repelling Mongol threats from the Iranian Plateau. So governors rebelled, and each brief assertion of independence was followed by their adoption of ever more exalted titles on their coins and public monuments. In 1281 Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Balban, the powerful sovereign of Delhi, ruthlessly stamped out one revolt by hunting down his rebel governor and publicly executing him. Yet within a week of Balban’s death in 1287, his own son, Bughra Khan, whom the father had left behind as his new governor, declared his independence. Bughra’s son, who ascended the Bengal throne as Rukn al-Din Kaikaus (1291–1300), then boldly styled himself on one mosque “the great Sultan, master of the necks of nations, the king of the kings of Turks and Persians, the lord of the crown, and the seal,” as well as “the right hand of the viceregent of God”—that is, “helper of the caliph.” On another mosque he even styled himself the “shadow of God” (z̄ill Allah), an exalted title derived from ancient Persian imperial usage.[26]

Exasperated with the wayward province, Delhi for several decades ceased mounting the massive military offensives necessary to keep it within its grip. In fact, the actions of Sultan Jalal al-Din Khalaji (r. 1290–96) betray something more than mere indifference toward the delta. A contemporary historian recorded that on one occasion the sultan rounded up about a thousand criminals (“thugs”) and “gave orders for them to be put into boats and to be conveyed into the Lower country to the neighbourhood of Lakhnauti, where they were to be set free. The thags would thus have to dwell about Lakhnauti, and would not trouble the neighbourhood (of Dehli) any more.”[27] Within a century of its conquest, then, Bengal had passed from being the crown jewel of the empire, whose conquest had occasioned the minting of gold commemorative coins, to a dumping ground for Delhi’s social undesirables. Already we discern here the seeds of a North Indian chauvinism toward the delta that would become more manifest in the aftermath of the Mughal conquest in the late sixteenth century.

| • | • | • |

The Early Bengal Sultanate, 1342–ca. 1400

In 1258 Mongol armies under the command of Hülegü Khan sacked Baghdad and executed the reigning caliph, al-Musta‘sim, thereby formally extinguishing the ultimate font of Islamic political legitimacy. Nonetheless, for a half century after this disaster, coins struck in India continued to invoke the phrase “in the time of the caliph, al-Musta‘sim,” suggesting the inability of Indo-Muslim rulers to conceive of any legitimizing authority other than that stemming from the titular Abbasid caliph. But finally, in 1320, Qutb al-Din Mubarak, the Delhi sultan, broke from tradition and boldly declared himself to be the caliph of Islam. Although the title did not stick, and was in fact harshly received, the principle was now established that Islam could have multiple caliphs, and that they could reside even outside the Arab world. This revolution in Islamic political thinking occurred just about the time when Bengal again asserted its independence from the Delhi sultanate. In 1342 a powerful noble, Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah (1342–57), wrested Bengal free from Delhi’s grip and established the first of several dynasties that remained independent from North India for the next two and a half centuries. The break with Delhi was marked by a shift of the Ilyas Shahi capital from Lakhnauti, the provincial capital throughout the age of Delhi’s hegemony, to the new site of Pandua, located some twenty miles to the north.

Initially, Delhi did not allow Bengal’s assertions of independence to go unchallenged. In 1353 Sultan Firuz Tughluq took an enormous army down the Ganges to punish the breakaway kingdom. Although Firuz slew up to 180,000 Bengalis and even temporarily dislodged Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah from his capital at Pandua, he failed to reannex the delta. Six years later, Firuz made another attempt to restore the delta to Delhi’s authority, but he was again rebuffed, this time by Shams al-Din’s son and successor, Sikandar Shah (r. 1357–89).[28] These inconclusive invasions of Bengal, and the successful tactics of the two Bengali kings to elude the North Indian imperialists by fading into the interior, finally persuaded Firuz and his successors of the futility of trying to hold onto the distant province. After 1359 Bengal was left undisturbed by North Indian armies for nearly two centuries.

In reality, the emergence of the independent Ilyas Shahi dynasty represented the political expression of a long-present cultural autonomy. In the late thirteenth century, Marco Polo made mention of “Bangala,” a place he had apparently heard of from his Muslim informants, and which he understood as being a region distinct from India, for he described it as “tolerably close to India” and its people as “wretched Idolaters” who spoke “a peculiar language.”[29] Our first indigenous reference to “Bengal” appears in the mid fourteenth century, when the historian Shams-i Siraj ‘Afif referred to Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah (1342–57) as the “sultan of the Bengalis” and the “king of Bengal.”[30] The coins of this ruler, and the architecture of his son and successor, clearly reflect the new mood of independence. Shams al-Din’s coins are inscribed:

Here the sultan not only proclaims an association with the caliphate but lays claim to imperial glory, calling himself “the second Alexander.” Though perhaps not measuring up to the accomplishments of Alexander the Great, Shams al-Din certainly did a creditable job of “world-conquering” in the politically dense theater of fourteenth-century India: in addition to resisting repeated invasions from Delhi, he defeated a host of neighboring Hindu rajas, namely those of Champaran, Tirhut, Kathmandu, Jajnagar, and Kamrup (corresponding to modern Bihar, Nepal,Orissa, and Assam).

[Obverse]:The just sultan, Shams al-dunya va al-din, Abu’l Muzaffar, Ilyas Shah, the Sultan. [Reverse:] The second Alexander, the right hand of the caliphate, the defender (or helper) of the Commander of the Faithful.[31]

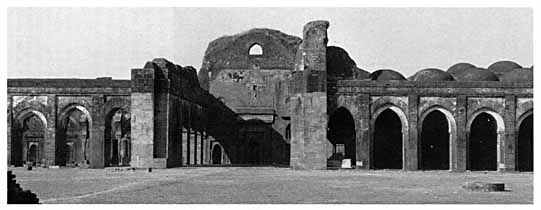

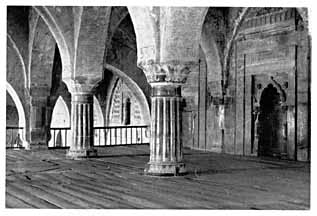

The most spectacular evidence of the dynasty’s imperial pretensions is seen in a single monument built by the founder’s son and successor, Sultan Sikandar (r. 1357–89). This is the famous Adina mosque, completed in 1375 in the Ilyas Shahi capital of Pandua (figs. 6 and 7). Although its builders reused a good deal of carved stone from pre-conquest monuments, the mosque does not appear to have been intended to convey a message of political subjugation to the region’s non-Muslims, who in any event would not have used the structure. In fact, stylistic motifs in the mosque’s prayer niches reveal the builders’ successful adaptation, and even appreciation, of late Pala-Sena art.[32] The imposing monument is also likely to have been a statement directed at Sikandar’s more distant Muslim audience, his former overlords in Delhi, now bitter rivals. Having successfully defended his kingdom from Sultan Firuz’s armies, Sikandar projected his claims of power and independence by erecting a monument greater in size than any edifice built by his North Indian rivals. Measuring 565 by 317 feet externally, and with an immense courtyard (445 by 168 feet) surrounded by a screen of arches and 370 domed bays, the Adina mosque easily surpassed Delhi’s Begumpur mosque, the principal mosque of Firuz Tughluq (1351–88), in size.[33] In fact, the Adina remains the largest mosque ever built in the Indian subcontinent.

Fig. 6. Interior of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Interior facing western wall, showing collapsed barrel vault. Photo by Catherine Asher.

Fig. 7. Exterior of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Exterior of western wall, showing fac^lade of barrel vault.

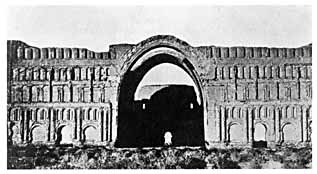

Fig. 8. Taq-i Kisra, Ctesiphon (near Baghdad, third century A.D.). Façade in the late nineteenth century. From Arthur Upham Pope, A Survey of Persian Art (Ashiya, Japan: Jay Glück, 1964), vol. 7, pl. 149. Reprinted by permission of Jay Glück.

Its style, moreover, signals a sharp break from the Delhi-based architectural tradition. The western, or Mecca-facing, side of the mosque projects a distinctly imperial mood, reminiscent of the grand style of pre-Islamic Iran.[34] This wall is a huge multistoried screen, whose exterior surfaces utilize alternating recesses and projections, both horizontally and vertically, to produce a shadowing effect. Whereas such a wall has no clear antecedent in Indo-Islamic architecture, it does recall the external façade of the famous Taq-i Kisra palace of Ctesiphon (third century A.D.), the most imposing architectural expression of Persian imperialism in Sasanian times (A.D. 225–641) (fig. 8). Even more revealing in this respect is the design of the mosque’s central nave. Whereas the sanctuary of the Tughluqs’ Begumpur mosque in Delhi was covered with a dome—a feature carried over, together with the four-iwan scheme, from Seljuq Iran (1037–1157) to India in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries[35]—that of the Adina mosque is covered with a barrel vault. Never before used on a monumental scale anywhere in India, this architectural device divided the whole structure into two halves, as did the great barrel vault of the Taq-i Kisra. The mosque thus departed decisively from Delhi’s architectural tradition, while drawing on the much earlier tradition of Sasanian Iran. We know that generations of Iranian architects and rulers had considered the Sasanian Taq-i Kisra palace to be the acme of visual grandiosity and splendor, and a model to be consciously imitated.[36] Thus Sikandar was at least an heir, if not a conscious imitator, of this tradition.

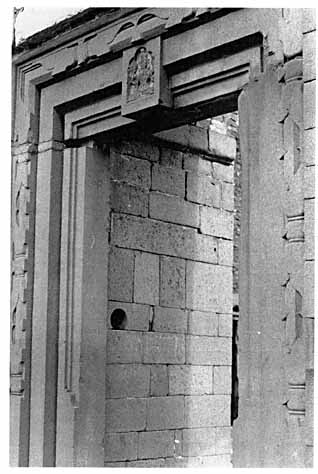

Fig. 9. Royal balcony of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Royal balcony, interior.

The interior of the Adina mosque also projects an aura of imperial majesty. To the immediate north of the central sanctuary is a raised platform, the so-called “king’s throne” (bādshāh kā takht), which enabled the sultan and his entourage to pray at a height elevated above the common people (fig. 9).[37] And, while the latter entered the mosque from a gate in the mosque’s southeast corner, the “king’s throne” could be reached only through a private entranceway that passed through the western wall. This entire doorway was evidently stripped from some pre-Muslim structure, as can be seen by the defaced Buddhist or Hindu image in its lintel (fig. 10). As if the mosque’s imperial architecture did not speak for itself, Sultan Sikandar ordered the following words inscribed on its western facade:

One word of praise for God, mentioned in passing, and the rest for the sultan!In the reign of the exalted Sultan, the wisest, the most just, the most liberal and most perfect of the Sultans of Arabia and Persia, who trust in the assistance of the Merciful Allah, Abul Mujahid Sikandar Shah the Sultan, son of Ilyas Shah, the Sultan. May his reign be perpetuated till the Day of Promise (Resurrection).[38]

Both the coinage and the architecture of the early Ilyas Shahi kings, then, indicate a strategy of political legitimization fundamentally different from that of their predecessors. Whereas the governors of thirteenth-century Bengal had merely transplanted Delhi’s architectural tradition to the delta, the sultans, having wrested their autonomy from Delhi, asserted their claims of legitimacy by placing state ideology alternately on pan-Islamic and imperial bases. If Sultan Sikandar’s architecture and Sultan Shams al-Din’s coinage reflect an imperial strategy of legitimation, we see the pan-Islamic approach in the latter’s claimed association with the caliph, and in the lavish patronage of the holiest shrines of Islam by Sikandar’s son and successor, Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah (r. 1389–1410), who sponsored the construction of Islamic colleges (madrasas) in both Mecca and Medina.[39]

Fig. 10. Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375). Lintel over royal doorway of Adina Mosque, Pandua (1375)

Moreover, although the Bengal sultans continued to inscribe most of their monuments and coins in Arabic, from the mid fourteenth century on, they began articulating their claims to political authority in Perso-Islamic terms. They employed Persianized royal paraphernalia, adopted an elaborate court ceremony modeled on the Sasanian imperial tradition, employed a hierarchical bureaucracy, and promoted Islam as a state-sponsored religion, a point vividly and continuously revealed on state coinage. Foreign dignitaries who visited Pandua at its height in the early fifteenth century remarked on a court ceremony that we can recognize as distinctly Persian. “The dwelling of the King,” wrote a Ming Chinese ambassador in 1415,

Clearly dazzled by the ceremony of Pandua’s royal court, the ambassador continued: “Two men bearing silver staffs and with turbaned heads came to usher (us) in. When (we) had taken five steps forward (we) made salutation. On reaching the middle (of the hall) they halted and two other men with gold staffs led us forward with some ceremony as previously. The King having returned our salutations, kotowed before the Imperial Mandate, raised it to his head, then opened and read it. The imperial gifts were all spread out on carpets in the audience hall.” The ambassador was then treated to a sumptuous banquet, after which the sultan “bestowed on the envoys gold basins, gold girdles, gold flagons, and gold bowls.”[41] The peacock feathers, the umbrellas, the files of foot soldiers, the throne inlaid with precious stones, the lavish use of gold—all of these point unmistakably to the kind of paraphernalia typically associated with Perso-Islamic and even Sasanian royalty. Only the presence of elephants recalls the ceremony of traditional Indian courts.is all of bricks set in mortar, the flight of steps leading up to it is high and broad. The halls are flat-roofed and white-washed inside. The inner doors are of triple thickness and of nine panels. In the audience hall all the pillars are plated with brass ornamented with figures of flowers and animals, carved and polished. To the right and left are long verandahs on which were drawn up (on the occasion of our audience) over a thousand men in shining armour, and on horseback outside, filling the courtyard, were long ranks of (our) Chinese (soldiers) in shining helmets and coats of mail, with spears, swords, bows and arrows, looking martial and lusty. To the right and the left of the King were hundreds of peacock feather umbrellas and before the hall were some hundreds of soldiers mounted on elephants. The king sat cross-legged in the principal hall on a high throne inlaid with precious stones and a two-edged sword lay across his lap.[40]

Whether appealing to mainly Islamic symbols of authority, as was typically the case from 1213 to 1342, or to imperial Persian symbols of authority, as was typically the case from 1342 on, the Muslim ruling class sought the basis of its political legitimacy in symbols originating outside the area over which they ruled. No more were Bengal’s rulers, like the early governors, content with declaring themselves merely first among “kings of the East.” On the Adina mosque, Sultan Sikandar proclaimed that he was the most perfect among kings of Arabia and Persia, not even mentioning those of the Indian subcontinent, where he was actually ruling. In the same spirit his son and successor, Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah, tried without success to persuade Hafiz, the great poet of Shiraz, to come and adorn his court at Pandua.[42] The political and cultural referents of these kings lay, not in Delhi or Central Asia, but much further to the west—in Mecca, Medina, Shiraz, and ancient Ctesiphon.

| • | • | • |

The Rise of Raja Ganesh (ca. 1400–1421)

Protracted over many decades, this campaign of self-legitimization by references external to Bengal was bound to have its effect on that other audience to which the Muslim regime addressed itself—the Bengali population, and especially the Hindu landholding elites whose cooperation was essential for the kingdom’s administration. Tensions between the Indo-Turkish ruling class and Hindu Bengali society surfaced toward the end of the fourteenth century when Sufis of the Chishti and Firdausi orders, who vehemently championed a reformed and purified Islam, insisted that the state’s foreign and Islamic identity not be diluted by admitting Bengalis into the ruling class. In 1397 Maulana Muzaffar Shams Balkhi (d. 1400), a Sufi of the Firdausi order, complained in a letter to Sultan Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah:

But such things did happen; indeed, they had to. Bengali nobles constituted a proud and experienced class of administrators who knew the land, the people, and the way local government had traditionally been managed. Even if the Indo-Turkish ruling class had wanted to recruit foreign administrators from Upper India or the Middle East, Bengal’s physical isolation from those areas, together with its political isolation from North India, dictated that powerful Hindu Bengali nobles be maintained in positions of local authority. Muzaffar Shams’s protest is itself evidence that such had been the policy.The vanquished unbelievers with heads hanging down, exercise their power and authority to administer the lands which belong to them. But they have also been appointed (executive) officers over the Muslims in the lands of Islam, and they impose their orders on them. Such things should not happen.[43]

In short, though the sultanate aligned itself ideologically with the Middle East, it was rooted politically in Bengal. This fundamental contradiction shaped the most severe domestic crisis the sultanate faced, an upheaval focusing on the rise of a remarkable noble named Raja Ganesh. Described in a contemporary letter as “a landholder of four hundred years’ standing”chahār ṣad sāla zamīndār),[44] this noble was evidently descended from a ruling family prominent since Pala and Sena times. By the opening of the fifteenth century, Raja Ganesh seems to have wielded effective control over the rich lands running along the Ganges between modern Rajshahi and Pabna.[45] He definitely belonged to that class of men to whom Muzaffar Shams referred when he wrote in 1397 of “vanquished unbelievers” exercising political authority over the Muslims of Bengal.

After Ghiyath al-Din’s death in 1410, tensions between Turks and Bengalis considerably intensified, and during the second decade of the fifteenth century, the crisis passed quite beyond the government’s control. According to the historian Muhammad Qasim Firishta (d. 1623), Raja Ganesh “attained to great power and predominance” during the reign of Sultan Shihab al-Din (1411–14), at which time the Bengali noble became the “master of the treasury and the kingdom.” When the sultan died, he wrote, Ganesh, “raising aloft the banner of kingship, seized the throne and ruled for three years and several months.”[46] But the historian Nizam al-Din Ahmad (d. 1594) makes no mention of Raja Ganesh having actually usurped the throne, recording only that when Sultan Shihab al-Din Bayazid Shah died, “a zamīndār [landholder] of the name of Kans [Ganesh] acquired power and dominion over the country of Bangala,” and that his “period of power [muddat-i istīlā’] lasted seven years.”[47] The only contemporary references to this episode are by Arab chroniclers, who evidently derived their information from pilgrims or other travelers who had journeyed from Bengal to Arabia. Affirming that the throne had passed from Ghiyath al-Din A‘zam Shah to his son Saif al-Din (1410–11), the chroniclers relate that the latter’s slave rebelled against Raja Ganesh, captured him, and seized control of the kingdom. But then, the chroniclers stated, the son of Raja Ganesh revolted against the usurper, converted to Islam under the adopted name Muhammad Jalal al-Din, and then himself mounted the throne as sultan of Bengal.[48]

A continuous run of coins minted by Muslim rulers in Bengal indicates that during the height of the turmoil, from 1410 to 1417, Muslim kings continued to hold de jure authority in the delta.[49] This being the case, Nizam al-Din’s statement that Raja Ganesh had acquired dominion in the kingdom suggests that the Bengali noble at this time ruled but did not reign, preferring to govern Bengal through a succession of Muslim puppets. Yet Ganesh evidently exerted overwhelming influence over these puppet sultans, for the contemporary Arab chroniclers, and later Firishta too, mistook his de facto rule for de jure sovereignty. In 1415, he took the even bolder step of getting his own son—according to a later source, a lad only twelve years old, named Jadu[50]—installed on the throne of Bengal. Now Raja Ganesh, backed by other Bengali nobles, ruled as regent for his own son.

Despite Raja Ganesh’s audacious maneuverings, however, the old guard of Turkish nobles prevented him and his supporters from upsetting the symbolic structure upon which the kingdom’s political ideology had rested for over two centuries. For Ganesh’s son Jadu did not reign as a Hindu raja; nor was he installed with any of the appropriate symbols of Hindu kingship. Rather, in what appears to have been a compromise formula worked out between political brokers for the Bengali and Turkish factions, he converted to Islam, was renamed Sultan Jalal al-Din Muhammad, and was then allowed to reign as a Muslim king.[51] Immediately upon his accession to power in 1415, the new sultan minted coins in his Islamic name. That these coins were issued simultaneously from Pandua and the provincial cities of Chittagong, Sonargaon, and Satgaon suggests a calculated attempt by Raja Ganesh to ensure the acceptance of his son’s accession to power as legitimate over all of Bengal.

If the Muslim nobility, succumbing to political reality, acquiesced and even participated in these new arrangements, the capital’s defenders of Islamic piety, the Sufis, reacted with shock and outrage. “How exalted is God!” exclaimed the most eminent of these, Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam:

Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam even wrote a letter to Ibrahim Sharqi, the sultan of neighboring Jaunpur, imploring him to invade the delta and rid Bengal of the usurping Raja Ganesh. “Why are you sitting calm and happy on your throne,” demanded the Sufi, “when the abode of faith of Islam has been reduced to such a condition! Arise and come to the aid of religion, for it is obligatory for you who are possessed of resources.”[53] Chronicling the years 1415–20, a Chinese source mentions that a kingdom to the west of Bengal had indeed invaded the delta, but desisted when placated with gold and money.[54] Although Central Asian and Arakanese traditions record somewhat different outcomes of Sultan Ibrahim’s invasion,[55] it is nonetheless clear that the sultan of Jaunpur failed to “liberate” the delta for “Islam” as Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam had hoped.How exalted is God! He has bestowed, without apparent reasons, the robe of faith on the lad of an infidel and installed him on the throne of the kingdom over his friends. Infidelity has gained predominance and the kingdom of Islam has been spoiled.

Who knows what Divine wisdom ordains

And what is fated for what individual existence?...

Alas, woe to me, the sun of Islam has become obscured and the moon of religion has become eclipsed.[52]

With the capital preoccupied with both internal turmoil and foreign invasion, remnants of various pre-Muslim ruling houses seized the moment to assert their independence from Turkish rule and to reconquer a vast stretch of the eastern and southern delta. For the single year A.H. 820, corresponding to A.D. February 1417-February 1418, no sultanate coins are known to have been issued anywhere in Bengal. On the other hand two successive Hindu kings, Danuja Marddana Deva and his son Mahendra Deva, minted coins during precisely that period from Chittagong, Sonargaon, and “Pāndunagara,” an apparent reference to Chhota Pandua in southwestern Bengal.[56] These kings appear to have been descendants of the Deva dynasty of kings of Chandradwip, a kingdom centered in what is now the Barisal area of southeastern Bengal, which had controlled a large area between Sonargaon and Chittagong in the thirteenth century.[57] But Danuja Marddana’s and Mahendra’s bid to restore the kingdom met with only brief success. In 1418 Sultan Jalal al-Din began issuing coins from what is now Faridpur, indicating that the forces of Raja Ganesh had managed to establish the sultanate’s authority in the heart of the southeastern delta.[58] Similar coins issued from Sonargaon and Satgaon in that same year, and from Chittagong in 1420, point to the dramatic reassertion of the sultanate’s authority throughout the delta.[59]

Although the revolt was snuffed out within a year or so, the coinage issued by its leaders tells us much of its ideological basis and of the religious sentiments then prevailing in the Bengal hinterland. On the obverse side of their coins, the Deva kings inscribed the Sanskrit phrase “Śrī Caṇḍī Caraṇa Parāyaṇa,” or “devoted to the feet of Goddess Chandi.”[60] The phrase corroborates the evidence of writings produced somewhat later that celebrate Chandi as a prominent folk deity and depict her as the protectress of Bengali kingship.[61] Yet, while reflecting a distinct memory of Hindu kingship, these same coins indicate the extent to which Islamic conceptions of political authority had by this time diffused throughout the delta. The inscriptions of the Deva coins are enclosed within various designs—single squares, double squares, plain circles, scalloped circles, triangular rayed circles, squares within circles, or hexagons—all of which had been firmly established in the numismatic tradition of Bengal’s Indo-Turkish rulers.[62] This suggests that, even while proclaiming the restoration of Hindu Bengali rule, leaders of the independence movement had to employ Indo-Turkish numismatic formulae to appear legitimate to the general population.

The Raja Ganesh period was a turning point in Bengali history. First, it proved that despite the objections of influential members of the Muslim elite, Bengali Hindus would henceforth be formally integrated into the sultanate’s ruling structure. In fact, the political integration of non-Muslims had begun long before the rise of Raja Ganesh, whose own behavior suggests their loyalty to the idea of the sultanate. Immediately upon dealing with the invasion by Sultan Ibrahim of Jaunpur, Ganesh turned his attention to quashing the Deva movements in southern and eastern Bengal, demonstrating his refusal to support explicitly Hindu restorations anywhere in the delta. Only by merging his interests with those of the kingdom as a whole, and by tempering his own power with a policy of conciliation with the powerful Indo-Turkish classes of the capital, did Raja Ganesh retain political influence.[63] Second, the Ganesh episode made telling points respecting the waning power of Hindu political symbolism in the delta. In the capital city, Raja Ganesh did not and could not raise his son to the throne as a Hindu; the future Sultan Jalal al-Din could reign only as a Muslim. As a Sufi source later put it, “In order to be sultan, he became Muslim” (“Az ḥasb-i sulṭān Musalmān gasht”).[64] In the country’s interior, on the other hand, a rebellion raised in the name of Chandi had demonstrated the continued popular association of that goddess with royalty. Yet even here the trappings of Islamic political legitimacy, though not yet its substance, had sunk deep roots, as the coins proclaiming the protection of the goddess were modeled after those of the Bengal sultans. At both royal and popular levels, Bengalis were gradually accommodating themselves to Muslim rule.

| • | • | • |

Sultan Jalal al-Din Muhammad (1415–32) and His Political Ideology

Surrounded by rebellious Hindus in the interior and by alarmed members of the Muslim elite in the capital, how did the boy-king and Muslim convert Sultan Jalal al-Din assert his own claims to the throne? First, he reversed the policy of his Hindu father respecting the highly influential circle of Chishti Sufis in the capital. Sufi sources, naturally partial to the cause of the shaikhs, depict Raja Ganesh as having systematically persecuted the Sufis of Pandua, even arranging for the murder of one of their next of kin.[65] But Sultan Jalal al-Din broke with this policy by submitting himself to the personal guidance of Pandua’s leading Chishti, Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam. Given the young king’s tender age at the time of his accession, it is likely that he had been entrusted to the religious care of the venerable Chishti saint as part of a compromise that Raja Ganesh and influential Indo-Turkish nobles worked out as their price for accepting Ganesh’s son as king. In any event, prominent members of the Chishti order clearly emerged as the principal legitimizers of Islamic authority in Bengal, a role they would continue to play for the remainder of the independent sultanate period, and through the Mughal period as well.[66]

Second, the new monarch sought to legitimize his rule by publicly displaying his credentials as a devout and correct Muslim.[67] Contemporary Arab sources hold that upon his conversion to Islam, Jalal al-Din adopted the Hanafi legal tradition and rebuilt the mosques demolished by his father. Between 1428 and 1431 he also supported the construction of a religious college in Mecca and established close ties with Sultan Ashraf Barsbay, the Mamluk ruler of Egypt. Having plied the latter with gifts, Jalal al-Din requested in return a letter of recognition from the Egyptian sultan, he being the most prestigious Muslim ruler in the Islamic heartlands and the custodian of a remnant line of the Abbasid caliphs. The Mamluk sultan complied with the request, sending the Bengal sultan a robe of honor as well as the letter of recognition.[68] Jalal al-Din also reintroduced on his coins the Muslim confession of faith, which had disappeared from Bengal’s coins for several centuries, since the time of Ghiyath al-Din ‘Iwaz (r. 1213–27).[69] In fact, he went a good deal further. Perhaps because he could not inscribe on his monuments and coins the usual self-legitimizing formula, “sultan, son of the sultan,” in 1427 the king, now a mature man with twelve years’ ruling experience, had himself described in one inscription as “the most exalted of the great sultans, the caliph of Allah in the universe.”[70] Having tested the reception of his bold statement on a single mosque, he took the bolder step three years later of including “the caliph of Allah” as one of his titles on his coins.[71] For a convert to the religion to claim for himself the loftiest title in the Sunni Muslim world—second only to the Prophet himself—was indeed a monumental leap.[72]

Even while strenuously asserting his credentials as a correct Muslim, Jalal al-Din inaugurated a two-century age when the ruling house sought to ground itself in local culture. Reflected in coinage, in patterns of court patronage, in language, in literature, and in architecture, this was by far the most important legacy of Sultan Jalal al-Din’s seventeen-year reign. Several undated issues of his silver coins[73] and a huge commemorative silver coin struck in Pandua in 1421 not only lack the Muslim confession of faith but bear the stylized figure of a lion (fig. 11). The numismatist G. S. Farid has explained this unusual motif by arguing that the latter coin—which at 105 grams in weight and 6.7 centimeters in width is perhaps the largest and heaviest coin ever struck in India—was minted for presentation to the emperor of China by Chinese ambassadors and soldiers residing at the Bengal court during the early fifteenth century.[74] Chinese chronicles do indeed record that the Bengal sultans presented silver coins to members of their Bengal mission.[75] But this hypothesis would not explain why the same lion motif is found on the ordinary silver coinage minted by the same sultan. An alternative explanation has been offered by A. H. Dani, who draws attention to Tripura, a small Hindu hill kingdom that managed to maintain a precarious independence on the extreme eastern edge of the delta throughout the sultanate and Mughal periods.[76] Noting that this kingdom depicted lions on its coins, Dani suggests that in addition to reconquering southern Bengal, Jalal al-Din may also have conquered Tripura, or parts of it, and issued this style of coinage in order to gain the support of its people.[77] However, since the earliest known lion-stamped coin minted by the independent rajas of Tripura did not appear until 1464, or thirty-two years after the death of Sultan Jalal al-Din, the sultan could not have been following the established custom of that kingdom.

Fig. 11. Large commemorative silver coin of Sultan Jalal al-Din Muhammad, struck in 1421. Actual size (6.7 cm in diameter).

On the other hand, one may see the motif of a lion—some species of which are indigenous to India—as a more generalized symbol of political authority in eastern Bengal, not limited to the rajas of Tripura. When the kings of Tripura began striking their own lion-motif coins from 1464 on, they did so as patrons of the Goddess manifested as Durga, whose vehicle (vāhana) is a lion.[78] Since the lion is also the vehicle of the Goddess as Chandi, in whose name a reconstituted Deva dynasty had unsuccessfully rebelled in 1416–18, the sultan possibly intended his lion-motif coins to appeal to deeply rooted sentiments that focused on Goddess-worship generally. Nor did he attempt to disguise his identity as the son of a Hindu chieftain, but instead proclaimed his paternity in Arabic letters, affirming himself to be bin Kans Rāo, “son of Raja Ganesh.”[79]

Sultan Jalal al-Din, then, was sending different messages to different constituencies in his kingdom. To Muslims, he portrayed himself as the model of a pious sultan, reviving inscription of the Muslim creed on his coinage and even making a claim, unprecedented in Bengal, to be the caliph of Allah. To Hindus, meanwhile, his coins proclaimed a sovereign who was the son of a Hindu king; moreover, they bore an image that, without actually naming Chandi or Durga, would have struck responsive chords among devotees of the Goddess. He also patronized Sanskritic culture by publicly demonstrating his appreciation for scholars steeped in classical Brahmanic scholarship.[80] What is more significant, a contemporary Chinese traveler reported that although Persian was understood by some in the court, the language in universal use there was Bengali.[81] This points to the waning, although certainly not yet the disappearance, of the sort of foreign mentality that the Muslim ruling class in Bengal had exhibited since its arrival over two centuries earlier. It also points to the survival, and now the triumph, of local Bengali culture at the highest level of official society.

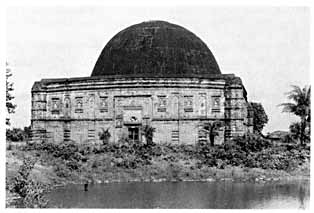

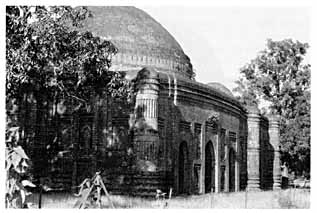

Fig. 12. Eklakhi Mausoleum, Pandua (ca. 1432).

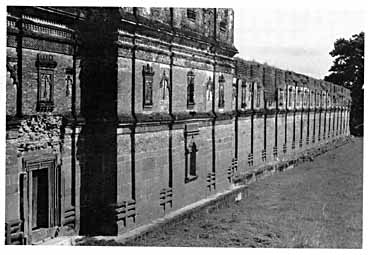

The new mood is seen most vividly in the architecture that appeared in the kingdom immediately after the Raja Ganesh episode. Abandoning Middle Eastern or North Indian traditions of religious architecture, Bengali mosques from the reign of Sultan Jalal al-Din on adopted purely indigenous motifs and structural traits.[82] Although not itself a mosque, the Eklakhi mausoleum in Pandua (fig. 12), believed to be the sultan’s own mausoleum, became the prototype for the subsequent Bengali-style mosque. Here we find all the hallmarks of the new style: square shape, single dome, exclusive use of brick construction in both exterior and interior, massive walls, engaged octagonal corner towers, curved cornice, and extensive terra-cotta ornamentation.[83] The last-mentioned feature, a Bengali tradition dating from at least the eighth century A.D., as in the Buddhist shrine at Paharpur, was now fully reestablished, as witnessed in the façade above the Eklakhi’s lintel. A mature example of the new style is seen in the Lattan mosque at Gaur, built ca. 1493–1519 (fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Lattan Mosque, Gaur (ca. 1493–1519).

Whence came the inspiration for this style of mosque? One source was the familiar thatched bamboo hut found everywhere in the villages of Bengal. Their curved roofs, formed by the natural bend of the bamboo structure under the weight of the thatching, were translated into brick for the first time in the Eklakhi mausoleum, with its gently curved cornice. Thereafter until the end of the sultanate, the thatched hut motif became an essential ingredient of Bengali architecture, whether public or private, Hindu or Muslim.[84] The art historian Perween Hasan has suggested still another indigenous source for the Bengali mosque. By comparing sultanate mosques with Buddhist monuments in Burma dating from the eighth to eleventh centuries, together with surviving evidence of Buddhist architecture in pre-twelfth-century Bengal, Hasan has come to the conclusion that Bengal’s Buddhist temple tradition directly contributed to the revival of the square, brick Bengali mosque in the fifteenth century.[85] Drawing on elements derived both from the rural Bengali thatched hut and from the pre-Islamic Buddhist temple, then, these structures reflect an essentially nativist movement, an effort to express an Islamic institution in locally familiar terms. This style of royal culture became so fixed that it persisted despite the restoration of the old Ilyas Shahi dynasty in 1433, and despite the drastic changes in the social composition of the ruling class that took place during the century following Jalal al-Din’s death in 1432.[86]

| • | • | • |

The Indigenization of Royal Authority, 1433–1538

The fifty years after Jalal al-Din’s death saw the restoration of the old Ilyas Shahi house and, in a curious throwback to the earliest days of Turkish rule in North India, the appearance of the institution of military slavery. In the 1460s and 1470s, however, instead of Central Asian Turks, black slaves (ḥabashī) from Abyssinia in East Africa were recruited for military and civil service.[87] But the influence of these men grew with their numbers, and in time they subverted the very purpose for which they had been imported.[88] In 1486 a coup d’état ended the Ilyas Shahi dynasty for good, plunging the sultanate into seven stormy years of palace intrigues and assassinations as slave after slave attempted to seize the reins of power. Ultimately, ‘Ala al-Din Husain, a Meccan Arab who had risen to the office of chief minister under an Abyssinian royal patron, emerged triumphant in another palace coup, which launched the last important ruling house of independent Bengal, the Husain Shahi dynasty.[89]

The reigns of Sultan ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah (1493–1519) and his son Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah (1519–32) are generally regarded as the “golden age” of the Bengal sultanate.[90] In Husain Shah’s reign, for example, Bengali Hindus participated in government to a considerable degree: his chief minister (vazīr), his chief of bodyguards, his master of the mint, his governor of Chittagong, his private physician, and his private secretary (dabīr-i khāṣ) were all Bengali Hindus.[91] In terms of its physical power and territorial extent, too, this was the sultanate’s high tide. In the second year of his reign, 1494, Sultan Husain Shah extended the kingdom’s northern frontiers, invading and annexing both Kuch Bihar (“Kamata”) and western Assam (“Kamrup”).[92] Writing around 1515, Tome Pires estimated this monarch’s armed forces at a hundred thousand cavalrymen. “He fights with heathen kings, great lords and greater than he,” wrote the Portuguese official, “but because the king of Bengal is nearer to the sea, he is more practised in war, and he prevails over them.”[93] The king thus managed to make a circle of vassals of his neighbors: Orissa to the southwest, Arakan to the southeast, and Tripura to the east.[94]

But the palmy days of independent Bengal were numbered. Even as the Husain Shahi dynasty was taking root, Babur, a brilliant Timurid prince, was rising to prominence in Central Asia and Afghanistan. In 1526, resolving to make a bid for empire in North India, Babur led his cavalry and cannon through the Khyber Pass and overthrew the Lodi dynasty of Afghans, the last rulers of a vastly shrunken and decayed Delhi sultanate. As a result of this triumph, defeated Afghans moved down the Gangetic plain and into the Bengal delta, where they were hospitably received by Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah.[95] Thus the span of a century from the death of Jalal al-Din Muhammad (d. 1432) to that of Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah (d. 1532) witnessed a wholesale transformation of Bengal’s political fabric. In the reign of the former sultan, descendants of old Turkish families had still formed the kingdom’s dominant ruling group. But in the following century the scope of Bengali participation at all levels of government continually widened, while the throne itself passed from Indo-Turks, to East Africans, to an Arab house, and, finally, to Afghans.

How did these changes affect the articulation of state authority? Within the precincts of the court, to be sure, a self-consciously Persian model of political authority was maintained to the end of the sultanate. A member of a Portuguese mission sent to Nasir al-Din’s court in 1521—the earliest-known European mission to Bengal—vividly describes the projection of royal power during his trip to the capital. Ushered into the sultan’s court, the writer passed by three hundred bare-chested soldiers bearing swords and round shields, and the same number of archers, on whose shields were painted golden lions with black claws. “We arrived before the place’s second gate and were searched as we had been at the first,” continues the mission’s anonymous interpreter.

The polo field at the heart of the court, the royal dais raised on sandalwood columns, the roof adorned with gilded carvings of birds and heavenly bodies, and the ceremonial etiquette before the sultan—all clearly indicate the survival of Persian political symbols at the sultanate’s ritual center. Indeed, this description of the court at Gaur closely compares with that of the court of Pandua given by a Chinese ambassador (see pp. 47—49) a century earlier.We passed through nine such gates and were searched each time. Beyond the last gate we saw an esplanade as vast as one and a half arena[s] and which seemed to be wider than it was long. Twelve horsemen were playing polo there. At one end there was a large platform mounted on thick sandal-wood supports. The roof supports were thinner and were covered in carvings of foliage and small gilded birds. The gilt ceiling was also carved and depicted the moon, the sun and a host of stars, all gilded.

We arrived before the Sultan. He was seated on a large gilt sofa covered with different-sized cushions, all of which were embedded with a smattering of precious stones and small pearls. We greeted him according to the custom of the country—hands crossed on our chests and heads as low as possible.[96]

But this political symbolism seems to have been intended for internal use only, as if the court were only reminding itself of its Persian political inheritance.[97] Publicly, the later sultans placed a much greater emphasis on merging their interests with local society and culture, as in their public displays of lavish generosity. Wrote the Portuguese diplomat just cited:

While a foreign dignitary was permitted to see a Persianized court with gilded ceilings and sandalwood posts, the common people saw cartloads of cooked rice “and other fruits of the earth.”I saw one hundred and fifty cartloads of cooked rice, large quantities of bread, rape, onions, bananas and other fruits of the earth. There were fifty other carts filled with boiled and roasted cows and sheep as well as plenty of cooked fish. All this was to be given to the poor. After the food had been distributed, money was given out, the whole to the value of six hundred thousand of our tangas.…I was totally amazed; it had to be seen to be believed. The money was thrown from the top of a platform into a crowd of about four or five thousand people.[98]

It was in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, too, that state-sponsored mosques built in native styles proliferated throughout the delta (see table 1). The court also lent vigorous support to Bengali language and literature. Already in the early fifteenth century, the Chinese traveler Ma Huan observed that Bengali was “the language in universal use.”[99] By the second half of the same century, the court was patronizing Bengali literary works as well as Persian romance literature. Sultan Rukn al-Din Barbak (r. 1459–74) patronized the writing of the śrī Kṛṣṇa-Vijaya by Maladhara Basu, and under ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah (1493–1519) and Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah (1519–32), the court patronized the writing of the Manasā-Vijaya by Vipra Das, the Padma-Purāṇa by Vijaya Gupta, the Kṛṣṇa-Maṅgala by Yasoraj Khan, and translations (from Sanskrit) of portions of the great epic Mahābhārata by Vijaya Pandita and Kavindra Parameśvara.[100] Sultan Mahmud Shah (1532–38) even dedicated a bridge using a Sanskrit inscription written in Bengali characters, and dated according to the Hindu calendar.[101]

| Ordinary | Congregational | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: Shamsud-Din Ahmed, ed. and trans., Inscriptions of Bengal (Rajshahi: Varendra Research Museum, 1960), 4: 317–38; Qeyamuddin Ahmad, Corpus of Arabic and Persian Inscriptions of Bihar (Patna: K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute, 1973); A. H. Dani, Muslim Architecture in Bengal (Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1961), 194–95; Epigraphia Indica, Arabic and Persian Supplement, 1965: 24; id., 1975: 34–36; Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan 2 (1957); id., 11, no. 2 (1966): 143–51; id., 12, no. 2 (1967): 296–303; Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 28, no. 2 (1983): 83–95; Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 6, nos. 1–2 (1964): 15–16; Journal of the Varendra Research Museum 2 (1973): 67–70; id., 4 (1975–76): 63–69, 71–80; id., 6 (1980–81): 101–8; id., 7 (1981–82): 184; Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 30, no. 3 (1973): 589; Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq, Arabic and Persian Texts of the Islamic Inscriptions of Bengal (Watertown, Mass.: South Asia Press, 1991), 4–123. | |||

| 1200–1250 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1250–1300 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 1300–1350 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1350–1400 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 1400–1450 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 1450–1500 | 52 | 9 | 61 |

| 1500–1550 | 28 | 28 | 56 |

| 1550–1600 | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| 1600–1650 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| 1650–1700 | 17 | 0 | 17 |

| 1700–1750 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| 1750–1800 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 147 | 41 | 188 |

In short, apart from the Persianized political ritual that survived within the court itself, from the early fifteenth century on, the sultanate articulated its authority through Bengali media. This resulted partly from reassessments made in the wake of the upheavals of the Raja Ganesh period and partly from sustained isolation from North India, which compelled rulers to base their claims of political legitimacy in terms that would attract local support. But royal patronage of Bengali culture was selective in nature. With the apparent aim of broadening the roots of its authority, the court patronized folk architecture as opposed to classical Indian styles, popular literature written in Bengali rather than Sanskrit texts, and Vaishnava Bengali officials instead of śākta Brahmans. At the same time, Islamic symbolism assumed a measurably lower posture in the projection of state authority. Political pragmatism seems to have dictated the most public of all royal deeds, the minting of coins. Sultan Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah described himself as “the sultan, son of the sultan, Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah, the sultan, son of Husain Shah, the sultan.”[102] Gone was the bombast of earlier periods, and gone too were references to Greek conquerors or Arab caliphs. Nasir al-Din Nusrat Shah was sultan simply because his father had been; no further justification was deemed necessary. Secure in power, these kings now presented themselves to all Bengalis as indigenous rulers.

It seems, moreover, that this was how contemporary Hindu poets perceived them. In a 1494 work glorifying the goddess Manasa, the poet Vijaya Gupta wove into his opening stanzas praises of the sultan of Bengal that would have flattered any classical Indian raja:

Similarly, in his śrī Caitanya Bhāgavat composed in the 1540s, Vrindavan Das refers to the Bengal king as rāja, never using the Arabo-Persian terms shāh or sulṭān. And in the early 1550s another Vaishnava poet, Jayananda, refers in his Caitanya-Maṅgala to the Muslim ruler not only as rāja but as iśvara (“god”), and even as Indra, the Vedic king of the gods.[104] The use of such titles signals a distinctly Bengali validation of the sultan’s authority.

Sultan Husain Raja, nurturer of the world: In war he is invincible; for his opponents he is Yama [god of death]. In his charity he is like Kalpataru [a fabled wish-yielding tree]. In his beauty he is like Kama [god of love]. His subjects enjoy happiness under his rule.[103]

In 1629, shortly after the Mughal conquest of Bengal, and still within living memory of the sultanate, the Augustinian friar Sebastião Manrique visited Bengal and remarked that some of its Muslim kings had been in the habit of sending for water from Ganga Sagar, the ancient holy site where the old Ganges (the modern Hooghly) emptied into the Bay of Bengal. Like Hindu sovereigns of the region, he wrote, these kings would wash themselves in that holy water during ceremonies connected with their installation.[105] This isolated reference, if narrated accurately to the European friar, would suggest that balancing the Persian symbols that pervaded their private audiences, the later sultans observed explicitly Indian rites during their coronations, events that were very public and symbolically charged. Contemporary poetic references to these kings as rāja or iśvara should not, then, be dismissed as mere hyperbole. They had become Bengali kings.

| • | • | • |

Summary

Having dislodged a Hindu dynasty in Bengal, the earliest Muslim rulers made no attempt on their coins to assert legitimate authority over their conquered subjects, displaying instead a show of coercive power. Their earliest architecture reveals an immigrant people still looking over their shoulders to distant Delhi. In the course of the thirteenth century, however, political rivalry with Delhi compelled Bengal’s rulers to adopt a posture of strenuous religious orthodoxy vis-à-vis their former overlords. This they did by associating themselves with the font of all Islamic legitimacy, the office of the caliph in Baghdad. After gaining independence from Delhi in the mid fourteenth century, the sultans of Bengal added to this posture a projection of Persian imperial ideology, reflected in the “Second Alexander” numismatic formula and in Sikandar’s grandiose and majestic Adina mosque.

By the early fifteenth century, however, too much emphasis upon either foreign basis of legitimacy—Islamic or imperial Persian—provoked a crisis of confidence among those powerful Bengali nobles upon whose continued political support the minority Muslim ruling class ultimately depended. That crisis, manifested in Raja Ganesh’s rise to all but legal sovereignty, in turn provoked a crisis of confidence among the chief Muslim literati, the Sufi elite of the time. These tensions were partially resolved by the conversion of Raja Ganesh’s son, Sultan Jalal al-Din, and the latter’s attempt to patronize each of the kingdom’s principal constituencies—pious Muslims, Sufis of the Chishti order, and devotees of the Goddess—on a separate, piecemeal basis.

But a comprehensive political ideology appealing to all Bengalis only appeared with the restored Ilyas Shahi dynasty and its successors. By evolving a stable, mainly secular modus vivendi with Bengali society and culture, in which mutually satisfactory patron-client relations became politically institutionalized, and in which the state systematically patronized the culture of the subject population, the later Bengal sultanate approximated what Marshall Hodgson has called a “military patronage state.”[106] Dropping all references to external sources of authority, the coins of the later sultans relied instead on a secular dynastic formula of legitimate succession: so-and-so was sultan because his father had been one. And in their public architecture, these kings yielded so much to Bengali conceptions of form and medium that, as the art historian Percy Brown observes, “the country, originally possessed by the invaders, now possessed them.”[107]

Notes

1. Here it is useful to distinguish between the terms authority and power. Max Weber defined the latter as “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests.” By analyzing the articulation of culturally contextualized political symbols, the present chapter focuses on what Weber understood as the basis “on which this probability rests”—that is, political authority. Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, ed. and trans. A. M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons (New York: Oxford University Press, 1947), 152.

2. Marilyn Robinson Waldman, Toward a Theory of Historical Narrative: A Case Study in Perso-Islamicate Historiography (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1988), 30.

3. Ann K. S. Lambton, State and Government in Medieval Islam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 106–29. See also Erwin I. J. Rosenthal, Political Thought in Medieval Islam: An Introductory Outline (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962), 42–43.